ABSTRACT

Field placement has traditionally been an important component of professional and vocational education programmes, and there is a growing interest in workplace experience in higher education programmes in general. In this article, we examine the direct and the indirect links between classroom preparation for placement, placement quality and programme coherence, and the development of student learning outcomes (general competence, knowledge and skills). Using a longitudinal survey of social work students, combined with data from national registers, we find that programme coherence has a direct positive impact on all three types of learning outcomes, classroom preparation for placement has a positive direct impact on knowledge and general competence, while placement quality only indirectly relates to student learning outcomes and is mediated by programme coherence. Placement quality is therefore important, but its positive impact on learning outcomes depends on whether it has a spillover effect on students’ experience of programme coherence.

Introduction

In higher education policy and research, there is growing interest in placement training and workplace experience as means to improve outcomes of education. To prepare students for a smooth transition into occupational life, university-based activities alone tend to be considered insufficient, and practical training and work experience are regarded as key elements in the development of graduates’ employability (European Commission Citation2014). Various types of placements, clinical placements, internships, workplace learning, and work-integrated learning have been implemented in a variety of educational fields. Moreover, in some countries, there has been a shift towards more on-the-job training and employment-based routes to teaching (Townsend Citation2011) and social work (Bellinger Citation2010), for example. However, there might be a tendency to overestimate the importance of practice in education, consequently ignoring the significance of abstract knowledge and formal learning (Young Citation2008; Kotzee Citation2012).

In this article, we aim to examine the relative importance of placement quality and an integrated curriculum for the development of student learning outcomes in terms of general competence, knowledge and skills. The three dimensions are similar to those in the European Qualifications Framework for Lifelong Learning (EQF) (European Commission Citation2018). Analytically, we link the one-sided focus on work experience and placement quality to an apprenticeship mode of learning and connect the emphasis on integration of learning during field placement and the university setting to a coherence perspective on student learning (Smeby and Heggen Citation2014). The apprenticeship mode and the coherence perspective are not mutually exclusive but represent different views on what is central to placement training. To examine the two perspectives on placement, we have conducted path-regression analyses based on data from a longitudinal student survey in Norway. In addition to information on students’ self-reported learning outcomes, our data also include information on individual factors that have been singled out as important for student outcomes, such as the students’ generalised self-efficacy, age, gender and grades in upper-secondary school (Caspersen and Smeby Citation2018).

Several studies have focused on the outcomes of placement during higher education. It is reported that placement increases graduates’ job readiness and employability in terms of improved generic skills (Wilton Citation2012), work readiness, self-efficacy and team skills (Smith and Worsfold Citation2015), graduate employment (Silva et al. Citation2018) and a higher starting salary (Brooks and Youngson Citation2014). Placement also seems to have a positive impact on student satisfaction (Smith and Worsfold Citation2014), student retention (Trede and McEwen Citation2015), pre-professional identity (Jackson Citation2017) and academic performance (Brooks and Youngson Citation2014; Jones, Green, and Higson Citation2017). It is emphasised that placement is a supplement, not an alternative to traditional on-campus training (Jackson Citation2015).

Although placement training is related to positive outcomes, it is not evident whether workplace experience itself is sufficient, and different understandings have been advocated. On one hand, the term work-integrated learning is used to emphasise a coherence perspective, that is, learning in placements and university settings should be integrated (Smith and Worsfold Citation2014; Billett Citation2015). On the other hand, paid employment during the final year of undergraduate studies seems to increase graduate employment to a higher extent than placements characterised as work-integrated learning (Jackson and Collings Citation2018). Moreover, it should be recognised that most outcome studies compare students with and without placements (Brooks and Youngson Citation2014; Jones, Green, and Higson Citation2017), not their work experience per se. There is a self-selection problem since academic performance tends to be positively correlated with choosing placement (Jones, Green, and Higson Citation2017).

We have chosen to focus on a specific programme – social work education. In social work, field placement is mandatory and well established. Field placement is considered to play a key role in developing students’ professional competence and understanding of the interaction between theory and practice (Wayne, Bogo, and Raskin Citation2010; Cornell-Swanson Citation2012; Boitel and Fromm Citation2014; Smith, Cleak, and Vreugdenhil Citation2015). It is also reported that students describe their placement as their most important learning experience (Cleak et al. Citation2015). Moreover, it is stated that no other component of the social work curriculum has been subject to as much research (Bogo Citation2015). Many researchers have emphasised the significance of the field supervisor and of the field placement pedagogy, and various factors identifying best practices are suggested (Cleak and Smith Citation2012; Bogo Citation2014, Citation2015; Nordstrand Citation2017; McSweeney and Williams Citation2018). Other scholars stress a curriculum perspective; in-class preparation for placement is proposed to aid students’ personal and professional learning (O'Connor, Cecil, and Boudioni Citation2009). Moreover, coordination, collaboration and partnerships between schools and workplaces have been developed (Foote Citation2015; Irvine, Molyneux, and Gillman Citation2015). It is also argued that curriculum and classroom teaching, not just field placement, are essential in enabling students to think and perform as social workers (Larrison and Korr Citation2013; Lynch, Bengtsson, and Hollertz Citation2018).

Although placement is established as a part of education, and a lot of research sheds light on the importance of practice in social work, it is not evident whether high-quality placement is at the core of professional development or whether a coherent curriculum is also significant (Lynch, Bengtsson, and Hollertz Citation2018). We would therefore argue that social work, with its well-established tradition for placement, as well as unsettled questions concerning placement quality and coherence, is an interesting case for tackling questions regarding field placement that are important for several higher education studies. In the social work literature, as well as the general higher education literature on placement reviewed above, it is not evident whether focusing on an apprenticeship mode of learning and placement quality is sufficient or whether a coherent curriculum is also needed. It is also argued that more research is needed regarding the relationships and mechanisms that enable placement to produce different kinds of outcomes in higher education and that focusing on simply describing the outcomes is clearly insufficient (Smith and Worsfold Citation2014).

Apprenticeship and coherence

The traditional apprenticeship model has its roots in the medieval guilds where the apprentice worked with a highly skilled specialist. This model of learning has been regarded as a journey through a series of stages of increasing complexity, supported by a master. The journey has provided the apprentice with the opportunity to mature not only in occupational expertise but also personally and morally (Fuller and Unwin Citation2009). Apprenticeship as a way of occupational preparation has been institutionalised in various ways in the course of history. As a specific mode of learning, it is generally characterised by observation, imitation and practice in an authentic workplace setting. Apprentices are not taught; they learn as part of everyday life and comprehend the knowledge they need to carry out their tasks, and their individual engagement is essential (Billett Citation2016).

It has been argued that the idea of apprenticeship may provide a basis for an inclusive social theory of learning (Guile and Young Citation1998). The renewed interest in the apprenticeship mode of learning is related to the practice turn in the learning theory, emphasising learning as participation in socially situated practice (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). The focus is not on individual cognitive abilities and learning as acquisition. According to this perspective, learning occurs as a socialisation process that involves the learners’ steadily increased participation in social practice. Moreover, a crucial point is that learning cannot be understood without reference to the context in which people act. Along with the practice turn in the learning theory, there has been a growing interest in workplace learning. The focal point for strengthening professional development has shifted from courses and programmes to professional learning as an aspect of work (Webster-Wright Citation2009; Timperley Citation2011). We claim that the socially situated theory of learning and the focus on workplace learning tend to underpin the increased interest in field placement in higher education and an apprenticeship mode of learning.

The institutionalisation of learning in schools and higher education implies a separation of the central aspects of professional competence, indicating a gap between theory and practice (Burrage Citation1993; Sullivan Citation2005; Joram Citation2007; Laursen Citation2015). The focus on graduate employability and job readiness implies that graduates of university disciplines are expected to have acquired not just a specified body of knowledge but also the ability to apply such knowledge in practical problem solving in a reflective and responsible way.

The coherence perspective has been introduced to address the importance of designing a curriculum that encourages students’ understanding of the relationships among different aspects of the knowledge that they are expected to learn, particularly between theoretical and practical types of knowledge and between learning experiences in university and practical settings. To highlight such curriculum structures, the term programme coherence has been applied (Grossman et al. Citation2008). To underscore individual agency, it has been argued that contradictions and differences also facilitate learning and that students’ understandings and the extent to which they develop meaningful relationships among the various aspects of knowledge and experiences should be at the core of integrated education (Heggen, Smeby, and Vågan Citation2015; Hatlevik and Havnes Citation2017). The coherence perspective largely corresponds to the idea behind the term work-integrated learning. Work-integrated learning includes the notion of integrative learning outcomes and should not be confused with work-based learning or simply work experience (Smith and Worsfold Citation2015).

As emphasised, the two perspectives (apprenticeship mode of learning and coherence) are not mutually exclusive. The key question here is whether placement in higher education should also be coherent with learning activities in university settings or whether focusing on placement quality is sufficient.

Methods and data

The empirical basis for this article is a three-year/six-semester Bachelor of Arts programme in social work offered by Norwegian universities. The bachelor's-degree level comprises different social work education programmes. In this article, social work education refers to social work and child welfare programmes. The programmes are governed by the same national framework regulations, and both qualify for graduates’ membership in the Norwegian Association of Social Workers. The students in both programmes undergo placement training for nine weeks in their second semester and 12 weeks in their fifth semester. The programme is characterised by its substantial efforts to prepare students for placement training and to facilitate the integration of learning in university and placement settings. Before the placement training period, compulsory teaching relevant to field studies is provided, such as presentations of the most relevant services and the reiteration of professional principles and communication skills. Students also have to write a placement report. We have conducted tests, which confirm that there are no important differences between the social work and the child welfare programmes. Based on a previous qualitative study of placement in social work education, we have in-depth knowledge about the programme’s structure and content and the students’ experiences in this programme (Vindegg and Smeby Citation2020).

Respondents and response rates

To examine the two perspectives on placement and their relations to learning outcomes, we use a longitudinal dataset on students from five universities and university colleges in Norway, taken from a longitudinal database for Studies of Recruitment and Qualifications in the Professions (StudData) at OsloMet. StudData is a collaborative project that contains responses to questions covering a wide range of issues. One of the authors was involved in the development of the questionnaires, and both authors have participated in the data collection and analyses for several years. The present article is based on students who were enrolled in 2012 and graduated in 2015. The response rates at the start of their education were 71.5% of 305 invitations to the students enrolled in the child welfare programme and 64.7% of 408 invitations to the students enrolled in the social work programme. The response rates at the end of their education were 66.7% of 249 invitations to the first group of students and 72.5% of 327 invitations to the second group of students. Despite the high response rates in each phase, the overall percentage of the survey respondents (panel retention) in both phases was 42%, which to some extent introduced a bias. However, attrition analyses of the database show no clear indications of non-random attrition (Caspersen Citation2013), except that male students dropped out more often than their female peers. This might affect the results of gender in the analyses, although the direction of potential bias is unclear. The analyses of the responses on other variables in the dataset show no significant differences between panels and phases.

Measures

The measures used are from three different points in time to take advantage of the longitudinal characteristic of the data.

From the period before the entry to the programmes, we have included all the respondents’ average grades in upper-secondary education, taken from national registers.

From the start of the students’ education in 2012, we have included gender, age and the generalised self-efficacy scale (taken from Schwartzer and Jerusalem Citation1995). Such individual variables are important to include as control because student learning outcomes are not just matters of contextual factors within educational programmes. Self-efficacy is a concept of long-standing influence on student learning and engagement (Zimmerman Citation2000). As most notably coined by Bandura (Citation1977), self-efficacy highlights how motivational aspects relate to different types of outcomes. Self-efficacy denotes the outcomes that students expect from their actions and has been linked to their performance in higher education (van Dinther, Dochy, and Segers Citation2011). Substantial evidence indicates that students’ self-efficacy beliefs in higher education affect their motivation, learning strategies and academic achievement (Diseth Citation2011; Yusuf Citation2011), and the relationship between self-efficacy and outcomes is continuously under scrutiny (Gebauer et al. Citation2019).

At the end of the students’ education, we have included three measures highlighting their experiences before, during and after their placement periods: their assessment of the preparation before placement, the placement quality during placement and their experience in programme coherence after placement. The decomposition of students’ experiences with placement provides a basis for examining the apprenticeship and the coherence perspectives on placement. While placement quality as a general concept relates to the apprenticeship model, preparation before placement and programme coherence relate to a coherence perspective.

Self-reported learning outcomes are measured using the same three dimensions highlighted in the EQF: knowledge, general competence and skills (European Commission Citation2018). The three dimensions come from a larger group of items examining higher education outcomes and have also been used in previous research on learning outcomes in higher education (Caspersen et al. Citation2014; Caspersen and Smeby Citation2018).

The variables used and the items constituting each variable, as well as scales and reliability coefficients (Cronbach's alpha), means and standard deviations, are presented in and Supplementary Table 1. We have also performed joint confirmatory factor analyses (structural equation modelling [SEM]) of the independent variables. The goodness-of-fit indexes are for the most part satisfactory (RMSEA = 0.05; p > chi2 0.000; CFI = 0.857; TLI = 0.846). The TLI and the CFI are slightly lower than most recommended cut-offs (normally, 0.90 or higher is suggested). However, these are mostly due to cross-loadings; one item (‘The guidance in practice has helped me to integrate theory and practice’) loads on both programme coherence and placement quality. Similarly, the item ‘The university college had prepared the students for the practical placement in a good way’ loads on both preparation and programme coherence. By removing these two items, the CFI and the TFI increase to 0.9, and the RMSEA drops to 0.047, indicating a good fit. However, in our analyses, we have included these items in our main measures because it makes more theoretical sense. The joint confirmatory factor analyses of the three dependent variables have similar fit measures (RMSEA = 0.079; p > chi2 0.000; CFI = 0.888; TLI = 0.862).

Table 1. Measure, number of items, alpha, scale, mean and standard deviation (SD), all measures. (Items for indexes, with mean and SD presented in Supplementary .)

Analyses

The analyses were performed as three separate path-regression models (calculated with maximum likelihood with missing values). The only difference is the alteration among the three types of learning outcomes. This approach makes it possible to calculate direct and indirect relationships between the confounding and the dependent variables, as well as compare relationships when different types of learning outcomes are used as dependent variables. All analyses were done using the SEM module in STATA 14.2.

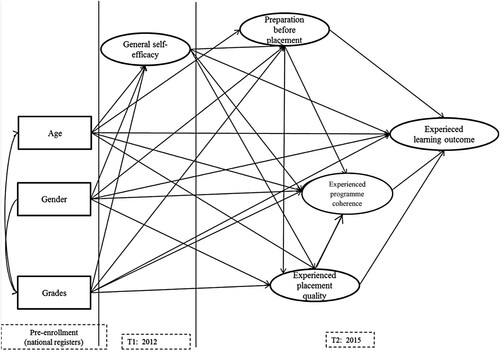

The basic model is presented in and based on the assumed relationships discussed in the introduction. The paths indicate the direction of possible relationships, as well as the temporal relation (age, gender and grades come before generalised self-efficacy, generalised self-efficacy before the study variables, preparation before experience in placement, experience in placment before experience in programme coherence, and experienced programme coherence before self-reported learning outcomes). The double arrows (between gender and grades) indicate a correlation between the variables.

Results

In –, we have included the path-regression models for the three learning outcome variables, with all non-significant paths removed. The arrows indicate a statistically significant relation (p < .05), and the double arrows represent a correlation.

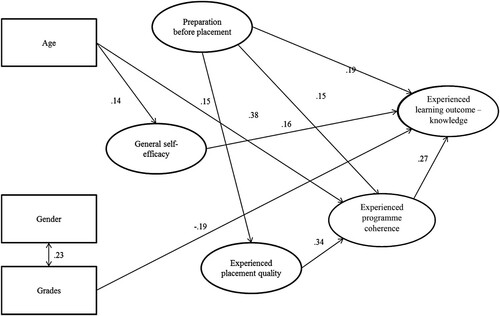

Figure 2. Final model of relationships – self-reported learning outcome on knowledge. Standardised regression coefficients.

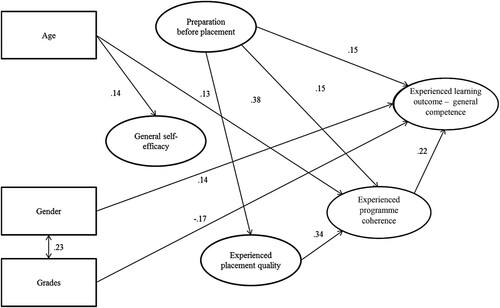

Figure 3. Final model of relationships – self-reported outcome on general competence dimension. Standardised regression coefficients.

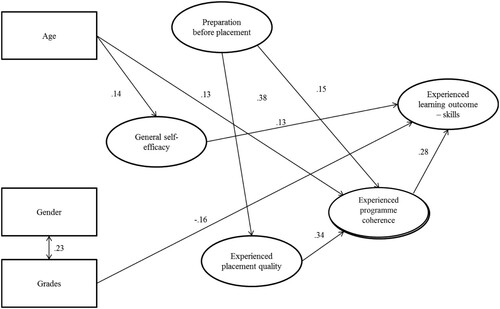

Figure 4. Final model of relationships – self-reported outcome on skills. Standardised regression coefficients.

Learning outcome – knowledge

In , the relationship between the confounding variables and the self-reported learning outcome on knowledge is presented, as well as the relationships between the other variables (only significant paths are presented).

Preparation before placement periods has a positive direct effect on knowledge (0.19), as well as positive indirect effects through experienced placement quality and experienced programme coherence (0.38 * 0.34 * 0.27 = 0.034; 0.16 * 0.27 = 0.0432). The total effect of preparation (indirect effects + direct effect) is 0.19 + 0.034 + 0.0432 = 0.27. Experienced placement quality has no significant direct effect on knowledge but a positive indirect effect through the experienced programme coherence (0.34 * 0.27 = 0.092). Finally, programme coherence has a positive direct effect on knowledge (0.27).

When the confounding variables are considered, the results show that gender and grades are correlated, women tend to have higher grades than men, and that grades have a significantly negative direct effect on knowledge. Age has a small but significant positive relation to both generalised self-efficacy and experienced programme coherence. Age has no relation to preparation before placement, experienced placement quality and knowledge. However, as generalised self-efficacy has a positive significant path towards knowledge, age has a small indirect positive effect through self-efficacy, and it is a direct positive relationship (0.16) between generalised self-efficacy and learning outcome (0.14 * 016 = 0.0224). The same holds for the indirect positive effect of age through experienced programme coherence (0.15 * 0.27 = 0.0405). Generalised self-efficacy has a direct positive effect on knowledge (0.16).

Learning outcome – general competence

presents the path model for the learning outcome on general competence. Except for small differences in the standardised coefficients, the only large difference between the models on knowledge and general competence is the lack of a significant path between generalised self-efficacy and general competence in the latter model. Preparation before placement (0.15) and experienced programme coherence (0.32) have direct positive effects on general competence. There is an indirect positive path from preparation before placement through experienced programme coherence (0.15) and experienced placement quality (0.38) to general competence. The correlation between gender and grades is similar to that in the model on knowledge. Grades have a significantly negative direct effect on general competence; gender is also significantly positively related to general competence. The relationship between age and generalised self-efficacy is also similar to that in the model on knowledge.

Learning outcome – skills

illustrates the path model for the self-reported learning outcome on skills. In , we find many of the same relations shown in and . The difference from the general competence and the knowledge models is the missing direct relation between preparation before placement and skills. The path between generalised self-efficacy and skills exists. The relationships between the other variables are also more or less similar to those presented in and , again indicating an indirect positive relationship between preparation before placement, as well as experienced placement quality, and the learning outcome but a direct positive relationship between experienced programme coherence and skills.

Considered together, the only difference in the set-up among the three models is the dependent variable (i.e. comprising the three dimensions of learning outcomes). Thus, the relationships between the different confounding variables are similar, as shown in –. The significant (p < .05) direct and indirect effects of the variables on the three dimensions of learning outcomes are summarised in Supplementary Table 2. The indirect effects are the products of the paths leading to the outcome variable. Since the calculation also includes insignificant paths, the numbers somewhat deviate from those shown in –.

Discussion

The key question in this article is whether field placement in higher education should also be coherent with learning activities in university settings or whether focusing on placement quality is sufficient for student learning outcomes. We have distinguished between an apprenticeship and a coherence perspective on placement. Our findings show that programme coherence has a direct positive impact on all three types of learning outcomes (knowledge, general competence and skills). Preparation before placement has a direct positive impact on knowledge and general competence and indirect impacts on all three types of learning outcomes, mediated by placement quality and programme coherence. Placement quality only indirectly affects learning outcomes positively and is mediated by programme coherence. The reason why we find no direct effect of classroom preparation on skills may be that some of the preparation is considered inadequate. A qualitative study of one of the social work programmes included in our study showed that particularly training in communication skills and methods was considered important preparation for placement. Training in writing administrative decisions was considered a waste of time (Vindegg and Smeby Citation2020). Placement quality is important, but its positive impact on learning outcomes depends on whether it has a spillover effect on the experience of programme coherence. In other words, the connections between placements and university-based aspects of education through preparation and experienced programme coherence are significant. Focusing on placement quality alone is insufficient. However, it is important to note the relatively strong positive direct relationship between placement quality and programme coherence and between preparation for placement and placement quality.

As discussed in the introduction, self-efficacy and individual characteristics, such as gender, age and grades in upper-secondary school, have proven important for learning outcomes in previous research (Caspersen and Smeby Citation2018). However, the variables also highlight the individual aspects of educational outcomes, in addition to the structural characteristics of study programmes. Furthermore, the relationships are not always straightforward, as shown in school grades’ negative direct impact on all three learning outcomes, in line with previous research findings (Caspersen and Smeby Citation2018). The reasonable explanation is that a self-reported learning outcome measures the subjective experience of knowledge gain. Students with higher academic qualifications upon enrolment may tend to experience lower subjective knowledge gain than students with lower grades. Self-efficacy has a positive direct impact on knowledge and skills, which corresponds to the previous research finding about the relation between self-efficacy and motivation in academic settings (Pajares Citation1996). A possible reason why self-efficacy is not related to general competence is that this outcome is more associated with values and attitudes. Age is indirectly positively related to the three learning outcomes, while being female has a direct relation to general competence in social work. Tolerance, ethical assessment ability and ability to understand other peoples’ situation are examples of general competence.

In this article, we have focused on the effects of placement quality, programme coherence and classroom preparation for placement on learning outcomes. The individual background factors’ indirect impacts on these variables are therefore particularly interesting. The literature emphasises that students’ experienced programme coherence is related to their efforts, not just the curriculum (Hatlevik and Havnes Citation2017), and individual agency is also highlighted as important for workplace learning outcomes (Billett Citation2016). Moreover, Smith and Worsfold (Citation2015) argue that the experience of quality in work-integrated learning in higher education not only depends on the actual organisation but also on how the students are primed to understand the links between education and work, as well as the alignment of learning activities. Both gender and age are therefore important variables, although in our analyses, age is the only individual variable with an indirect effect on learning outcomes. Age is positively related to programme coherence in all three models. Since age is related to various kinds of experiences, this finding seems reasonable. Based on the emphasis on student effort (presented above), we expected that some of the other individual variables would have a positive impact on student assessment of placement quality and coherence; particularly, we expected that self-efficacy would have such an effect. The reason for the lack of relationship may be that these variables are based on students’ individual assessments rather than on more objective measures.

The social work literature emphasises that field placement contributes to the integration of the various aspects of social workers’ competence, especially theoretical knowledge and practical skills (Wayne, Bogo, and Raskin Citation2010). A key element of learning is the construction of meaning. Students’ experienced programme coherence implies that they have developed meaningful relationships among the various aspects of professional competence, as well as their experiences in classroom teaching and field placement. The development of such meaningful relationships underpins student learning (Illeris Citation2011; Hatlevik and Havnes Citation2017). In short, the coherence perspective contributes to the understanding of why integration of learning in the two settings is required for placement quality to have a significant (indirect) impact and why it has a positive impact on all three learning outcomes.

The distinction among general competence, knowledge and skills has been benchmarked as a standardised way of understanding the complexity of outcomes in all types of education through the EQF. There are important differences between professional and disciplinary programmes, however. While disciplinary curricula are characterised by conceptual coherence, professional programmes have contextual coherence (Muller Citation2009). Conceptual coherence refers to the epistemic relationships among the various elements of the curricula, whereas contextual coherence pertains to the relationships based on the relevance for professional practice. In this article, we have focused on contextual coherence and have not addressed conceptual coherence. Since workplace experiences constitute a way to strengthen contextual coherence, it is reasonable to assume its positive relation to students’ acquired knowledge in social work education, but it may not have the same impact in disciplinary fields. Nonetheless, the distinction between conceptual and contextual coherence is analytical, and they are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, strengthening contextual coherence by including placement in disciplinary curricula may have positive impacts on student learning outcomes in terms of knowledge in such fields as well.

Conclusions

In our review of the literature on field placement in social work, we have argued that some researchers tend to emphasise the quality of field placement, while others stress all parts of the social work curriculum. However, it should be recognised that although their areas of focus differ, the majority of social work scholars agree on the importance of placement quality, as well as preparation for placement and programme coherence. Moreover, faculty members, administrators and field supervisors, at least in the Norwegian educational programmes, have systematically worked to develop these aspects (Vindegg and Smeby Citation2020). Our results indicate that programme coherence and placement quality are important and that the impact of placement quality depends on coherence. We believe that these findings are essential, also for higher education research in general. Placement quality as a general concept is insufficient, and the same holds for general approaches to work experiences. While field placement is often voluntary and rather decoupled from other parts of the curricula in other programmes, it is an established and a mandatory component of social work programmes. The former kind of field placements may increase student satisfaction and employability (Jackson and Collings Citation2018), but our study indicates that student learning outcomes also depend on coherence: how students are prepared for placement, how placement experiences are linked to what is learned in classroom settings and how workplace experiences are incorporated into classroom teaching after placement periods. Through the coherence perspective, the importance of developing meaningful relationships among the various aspects of knowledge, as well as learning in different arenas, is highlighted.

Limitations and further research

In our study, preparation for placement, placement quality, programme coherence, as well as learning outcomes, are students’ self-reported variables. Self-reported variables have both advantages and weaknesses (Caspersen, Smeby, and Aamodt Citation2017). In future research, it would be interesting if more objective context variables, as well as test-based learning outcome variables, would be available. Our study is also based on a somewhat limited sample size, with a significant panel attrition in the data. This weakens the potential strengths of the longitudinal design. Although we argue that it is useful to focus on a specific field, there is a need for studies on placement in other professional and disciplinary programmes to unpack the importance and the role of field placement in learning outcomes. Moreover, the operationalisation of the three types of learning outcomes in our study is not profession specific but formulated in a general way to fit in with more groups and enable comparisons across groups. More discipline-specific and field-specific operationalisations may be useful to delve even deeper into how placement contributes to student learning outcomes in different fields and disciplines.

Supplementary Material

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)Supplementary Material

Download MS Word (20.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The study is part of the project ‘Contradictory institutional logics in interaction’. We are grateful to Anton Havnes and our colleagues in the project group for their comments and criticisms of earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

- Bellinger, Avril. 2010. “Studying the Landscape: Practice Learning for Social Work Reconsidered.” Social Work Education 29 (6): 599–615. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470903508743.

- Billett, Stephen. 2015. Professional and Practice-Based Learning. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Billett, Stephen. 2016. “Apprenticeship as a Mode of Learning and Model of Education.” Education & Training 58 (6): 613–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-01-2016-0001.

- Bogo, Marion. 2014. Achieving Competence in Social Work through Field Education. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Bogo, Marion. 2015. “Field Education for Clinical Social Work Practice: Best Practices and Contemporary Challenges.” Clinical Social Work Journal 43 (3): 317–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0526-5.

- Boitel, Craig R., and Laurentine R. Fromm. 2014. “Defining Signature Pedagogy in Social Work Education: Learning Theory and the Learning Contract.” Journal of Social Work Education 50 (4): 608–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2014.947161.

- Brooks, Ruth, and Paul L. Youngson. 2014. “Undergraduate Work Placements: An Analysis of the Effects on Career Progression.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (9): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.988702.

- Burrage, Michael. 1993. “From Practice to School-Based Professional Education: Patterns of Conflict Accommodation in England, France, and the United States.” In The European and American University Since 1800, edited by S. Rothblatt, and B. Wittrock, 142–87. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Caspersen, Joakim. 2013. “Professionalism among Novice Teachers. How They Think, Act, Cope and Perceive Knowledge. “ PhD diss., Oslo and Akershus University College.

- Caspersen, Joakim, Nicoline Frølich, Hilde Karlsen, and Per Olaf Aamodt. 2014. “Learning Outcomes Across Disciplines and Professions: Measurement and Interpretation.” Quality in Higher Education 20 (2): 195–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2014.904587.

- Caspersen, Joakim, and Jens-Christian Smeby. 2018. “The Relationship among Learning Outcome Measures Used in Higher Education.” Quality in Higher Education 24 (2): 117–135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2018.1484411.

- Caspersen, Joakim, Jens-Christian Smeby, and Per Olaf Aamodt. 2017. “Measuring Learning Outcomes.” European Journal of Education 52 (1): 20–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12205.

- Cleak, Helen, Linette Hawkins, Jody Laughton, and Judy Williams. 2015. “Creating a Standardised Teaching and Learning Framework for Social Work Field Placements.” Australian Social Work 68 (1): 49–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2014.932401.

- Cleak, Helen, and Debra Smith. 2012. “Student Satisfaction with Models of Field Placement Supervision.” Australian Social Work 65 (2): 243–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2011.572981.

- Cornell-Swanson, La Vonne J. 2012. “Toward a Comprehensive Pedagogy in Social Work Education.” In Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind, edited by Nancy L. Chick, Aeron Haynie, and Regan A. R. Gurung, 203–16. Sterling: Stylus Publishing.

- Diseth, Åge. 2011. “Self-Efficacy, Goal Orientations and Learning Strategies as Mediators between Preceding and Subsequent Academic Achievement.” Learning and Individual Differences 21 (2): 191–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.01.003.

- European Commission. 2014. Modernisation of Higher Education in Europe: Access, Retention and Employability, Eurydice Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Commission. 2018. The European Qualifications Framework: Supporting Learning, Work and Cross-Border Mobility. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Foote, Wendy L. 2015. “Social Work Field Educators’ Views on Student Specific Learning Needs.” Social Work Education 34 (3): 286–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1005069.

- Fuller, Alison, and Lorna Unwin. 2009. “Change and Continuity in Apprenticeship: The Resilience of a Model of Learning.” Journal of Education and Work 22 (5): 405–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080903454043.

- Gebauer, Miriam M., Nele McElvany, Wilfried Bos, Olaf Köller, and Christian Schöber. 2019. “Determinants of Academic Self-Efficacy in Different Socialization Contexts: Investigating the Relationship between Students’ Academic Self-Efficacy and its Sources in Different Contexts.” Social Psychology of Education, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-019-09535-0.

- Grossman, Pam, Karen Hammerness, Morva McDonald, and Matt Ronfeldt. 2008. “Constructing Coherence. Structural and Perceptions of Coherence in NYC Teacher Education Programs.” Journal of Teacher Education 59 (4): 273–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108322127.

- Guile, David, and Michael Young. 1998. “Apprenticeship as a Conceptual Basis for a Social Theory of Learning.” Journal of Vocational Education and Training 50 (2): 173–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13636829800200044.

- Hatlevik, Ida Katrine Riksaasen, and Anton Havnes. 2017. “Perspektiver på læring i profesjonsutdanninger - fruktbare spenninger og meningsfulle sammenhenger.” In Kvalifisering til profesjonell yrkesutøvelse, edited by Sølvi Mausethagen and Jens-Christian Smeby, 191–203. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Heggen, Kåre, Jens-Christian Smeby, and André Vågan. 2015. “Coherence - A Longitudinal Approach.” In From Vocational to Professional Education. Educating for Social Welfare, edited by Jens-Christian Smeby, and Molly Sutphen, 70–88. London: Routledge.

- Illeris, Knud. 2011. “Workplace and Learning.” In The Sage Handbook of Workplace Learning, edited by Margaret Malloch, Len Cairns, Karen Evans, and Bridget N. O'Connor, 32–45. London: Sage.

- Irvine, Julie, Jeanie Molyneux, and Maureen Gillman. 2015. “'Providing a Link with the Real World': Learning from the Student Experience of Service User and Carer Involvement in Social Work Education.” Social Work Education 34 (2): 138–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2014.957178.

- Jackson, Denise. 2015. “Employability Skill Development in Work-Integrated Learning: Barriers and Best Practice.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (2): 350–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.842221.

- Jackson, Denise. 2017. “Developing Pre-Professional Identity in Undergraduates through Work-Integrated Learning.” Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education Research 74 (5): 833–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0080-2.

- Jackson, Denise, and David Collings. 2018. “The Influence of Work-Integrated Learning and Paid Work During Studies on Graduate Employment and Underemployment.” The International Journal of Higher Education Research 76 (3): 403–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0216-z.

- Jones, Chris M., Joseph P. Green, and Helen E. Higson. 2017. “Do Work Placements Improve Final Year Academic Performance or Do High-Calibre Students Choose to Do Work Placements?” Studies in Higher Education 42 (6): 976–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1073249.

- Joram, Elana. 2007. “Clashing Epistemologies: Aspiring Teachers’, Practicing Teachers’, and Professors’ Beliefs about Knowledge and Research in Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 23 (2): 123–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.032.

- Kotzee, Ben. 2012. “Expertise, Fluency and Social Realism about Professional Knowledge.” Journal of Education and Work 27 (2): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2012.738291.

- Larrison, Tara Earls, and Wynne S. Korr. 2013. “Does Social Work Have a Signature Pedagogy?” Journal of Social Work Education 49 (2): 194–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2013.768102.

- Laursen, Per Fibæk. 2015. “Multiple Bridges between Theory and Practice.” In From Vocational to Professional Education: Educating for Social Welfare, edited by Jens-Christian Smeby, and Molly Sutphen, 89–104. London: Routledge.

- Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lynch, Michael Wallengren, Anna Ryan Bengtsson, and Katarina Hollertz. 2018. “Applying a ‘Signature Pedagogy’ in the Teaching of Critical Social Work Theory and Practice.” Social Work Education 38 (3): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1498474.

- McSweeney, Fiona, and Dave Williams. 2018. “Social Care Students’ Learning in the Practice Placement in Ireland.” Social Work Education 37 (5): 581–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1450374.

- Muller, Johan. 2009. “Forms of Knowledge and Curriculum Coherence.” Journal of Education and Work 22 (3): 205–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080902957905.

- Nordstrand, Mari. 2017. “Practice Supervisors’ Perceptions of Social Work Students and Their Placements – an Exploratory Study in the Norwegian Context.” Social Work Education 36 (5): 481–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1279137.

- O'Connor, Louise, Bob Cecil, and Markella Boudioni. 2009. “Preparing for Practice: An Evaluation of an Undergraduate Social Work ‘Preparation for Practice’ Module.” Social Work Education 28 (4): 436–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470701634311.

- Pajares, Frank. 1996. “Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Academic Settings.” Review of Educational Research 66 (4): 543–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066004543.

- Schwartzer, R., and M. Jerusalem. 1995. “Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale.” In Measures in Health Psychology: A User's Portfolio, edited by M. Johnston, S. Wright, and I. Weinman, 35–37. Windsor: NFER Nelson.

- Silva, Patrícia, Betina Lopes, Marco Costa, Ana I. Melo, Gonçalo Paiva Dias, Elisabeth Brito, and Dina Seabra. 2018. “The Million-Dollar Question: Can Internships Boost Employment?” Studies in Higher Education 43 (1): 2–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1144181.

- Smeby, Jens-Christian, and Kåre Heggen. 2014. “Coherence and the Development of Professional Knowledge and Skills.” Journal of Education and Work 27 (1): 71–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2012.718749.

- Smith, Debra, Helen Cleak, and Anthea Vreugdenhil. 2015. “'What Are They Really Doing?’ An Exploration of Student Learning Activities in Field Placement.” Australian Social Work 68 (4): 515–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2014.960433.

- Smith, Calvin, and Kate Worsfold. 2014. “WIL Curriculum Design and Student Learning: A Structural Model of their Effects on Student Satisfaction.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (6): 1070–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.777407.

- Smith, Calvin, and Kate Worsfold. 2015. “Unpacking the Learning–Work Nexus: ‘Priming’ as Lever for High-Quality Learning Outcomes in Work-Integrated Learning Curricula.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (1): 22–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.806456.

- Sullivan, William M. 2005. Work and Integrity. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Timperley, Helen S. 2011. Realizing the Power of Professional Learning, Expanding Educational Horizons. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Townsend, Tony. 2011. “Searching High and Searching Low, Searching East and Searching West: Looking for Trust in Teacher Education.” Journal of Education for Teaching 37 (4): 483–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2011.611017.

- Trede, Franziska, and Celina McEwen. 2015. “Early Workplace Learning Experiences: What Are the Pedagogical Possibilities Beyond Retention and Employability?” Higher Education 69 (1): 19–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9759-4.

- van Dinther, Mart, Filip Dochy, and Mien Segers. 2011. “Factors Affecting Students’ Self-Efficacy in Higher Education.” Educational Research Review 6 (2): 95–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.10.003.

- Vindegg, Jorunn, and Jens-Christian Smeby. 2020. “Narrative Reasoning and Coherent Alignment in Field Placement.” Social Work Education 39 (3): 302–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1641192.

- Wayne, Julianne, Marion Bogo, and Miriam Raskin. 2010. “Field Education as the Signature Pedagogy in Social Work Education.” Journal of Social Work Education 46 (3): 327–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2010.200900043.

- Webster-Wright, Ann. 2009. “Reframing Professional Development through Understanding Authentic Professional Learning.” Review of Educational Research 79 (2): 702–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308330970.

- Wilton, Nick. 2012. “The Impact of Work Placements on Skills Development and Career Outcomes for Business and Management Graduates.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (5): 603–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.532548.

- Young, Michael F. D. 2008. Bringing Knowledge Back in: From Social Constructivism to Social Realism in the Sociology of Education. London: Routledge.

- Yusuf, Muhammed. 2011. “The Impact of Self-Efficacy, Achievement Motivation, and Self-Regulated Learning Strategies on Students’ Academic Achievement.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 15: 2623–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.158.

- Zimmerman, Barry J. 2000. “Self-Efficacy: An Essential Motive to Learn.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 (1): 82–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1016.