ABSTRACT

For many adult learners transitioning into higher education is an intense experience that challenges their sense of themselves. This article reports on a study that examined the discourse of thirty-four undergraduate adult learners at the start and end of their first year in two Irish higher education institutions. The study focused on participants’ evolving sense of who they were in the new educational context and how they incorporated this new adult learner identity into their existing identity portfolio, their overall sense of who they are. The key finding in this discursive psychology analysis of interview data was that participants engaged in two interrelated forms of identity work across their first year: constructing an identity formation narrative, about becoming adult learners; and ongoing, day-to-day identity management. The study illustrates how these adult learners experienced varying degrees of identity struggle, which had to be minimised if they were to maintain a consistent and coherent sense of themselves.

Introduction

Educational research on the transition of learners into higher education and the first year experience is predominantly focused on traditional-age school-leavers, with less focus on the transition experiences of adult learners (Mehmet et al. Citation2019), who differ from traditional-age learners in terms of psychological, academic, and life characteristics (Richardson and Kind Citation1998). This is despite the fact that the extension of opportunities for adult learners to enter higher education is a growing international goal, policy, and reality (European Commission Citation2014; OECD Citation2015). In Ireland, government strategy seeks to increase adult learner numbers in higher education, defined as learners over 23 years (HEA Citation2015). However, the process of transitioning, defined as ‘a capability to navigate change’ (Gale and Parker Citation2014, 737), is challenging for adult learners (Allen-Collinson and Brown Citation2012; Kahu and Nelson Citation2018). The transition into higher education is an intense experience, testing an individual’s sense of the coherence or stability of their existing sense of who they are (Baxter and Britton Citation2001; Willans and Seary Citation2011). Understanding how adult learners psychologically form and manage their identities is vital to understanding their motivations, barriers to learning, and support needs (Askham Citation2008; Ecclestone, Biesta, and Hughes Citation2010).

This study examined the discourse of thirty-four adult learners as they formed new adult learner identities in their first year at university. With a focus on these learners’ own discourses on forming a new identity a psychological approach was adopted in order to examine ‘what they do’ within a discourse to enact particular identity positions (McLean and Price Citation2019). The study examined both the process of forming and maintaining a new identity and the day-to-day identity management processes involved in knowing who to be in the different parts of one’s life, as both are ongoing during a transition period (Bell, Wieling, and Watson Citation2007; McAlpine and Amundsen Citation2011; McLean, Pasupathi, and Pais Citation2007). However, the study draws on more than psychological literature as the study of identity, student success, and transition are informed by wider scholarship from fields such as identity studies, sociology, socio-cultural studies, and educational research.

Theoretical framework

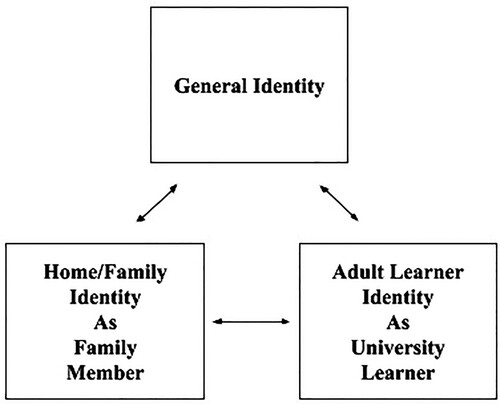

This study is bounded by a theoretical framework that draws on literature focused on identity formation. Identity is viewed through a psychological lens as ‘co-constructed, negotiated in everyday interactions, and related to the interaction between forms of structure and agency’ (McLean Citation2012, 99). This study also views individual identity as a multidimensional, biopsychosocial process where individuals have a coherent sense of themselves over time (Askham Citation2008; McAlpine and Amundsen Citation2011; Stapleton and Wilson Citation2003). In this context coherence is the relative ability to tell an overall story of ‘who we are’ to ourselves and others without experiencing psychological dissonance or conflict. Individuals maintain this sense of themselves over time through engaging in identity work, defined as an engagement in processes of forming, repairing, maintaining, strengthening, or revising those constructions that produce a sense of personal distinctiveness and coherence (Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003). Identity struggle is a related concept that refers to the way in which individuals constantly strive to shape their identities in the face of discursive forces within complex and fragmented contexts, to strive for comfort, meaning and integration, and a sense of coherence and continuity (Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003). The multidimensional identity structure, or identity portfolio, is made up of a general identity that one portrays across different parts of one’s life, and the context-specific-identities one forms for the different roles and contexts in one’s life (Leonard, Beauvais, and Scholl Citation1999) (see ).

An important aspect of a context-specific-identity is the individual’s relative sense of identification with, or belonging to that context and its other members (Ashforth Citation2001). The degree to which an individual perceives that they are psychologically intertwined with other context members influences their behaviour in that context (Leonard, Beauvais, and Scholl Citation1999). Moments of change or turning points experienced by an individual, for example, changes in relationship or work status or attending/returning to higher education, are challenging (Anderson, Goodman, and Schlossberg Citation2012) and cause them to engage in concentrated identity work.

In the next section, this article will examine literature relating to forms of identity work that are ongoing during a transition into higher education, i.e. identity formation processes and day-to-day identity management, as well as typical outcomes depending on the degree to which identity struggle has been minimised.

Identity work in the transition to higher education

Transitioning into higher education, and forming an adult learner identity, involves engagement in two distinct types of identity work: an identity formation process (Bell, Wieling, and Watson Citation2007), and engagement in active, day-to-day identity management work when changing between different context-specific-identities (Campbell-Clark Citation2000), for example, home/family, work, and higher education. These forms of identity work are required to maintain an overall sense of coherence and distinctiveness and avoid too great a degree of identity struggle during the transition (Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003). For example, the new identity must be worked into the individual’s overall story to themselves and others of ‘who they are’, and day-to-day changes between identities must become relatively straightforward, if identity struggle is to be minimised. These two forms of identity work will now be examined in turn.

Identity formation

Adult learners, no matter how well adjusted, face significant individual change during entry into education (Mercer Citation2007; Willans and Seary Citation2011). The changing sense of who they are during transition causes a degree of identity struggle (Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003) as they navigate the interaction between their emergent identity and their existing sense of who they are (Baxter and Britton Citation2001; O’Boyle Citation2015). Identity formation is a longer-term, more macro-level process than identity work that happens day-to-day when changing between different contexts (Bell, Wieling, and Watson Citation2007). An unexpected disconnect between student expectations and their actual experience can cause identity formation to be more intense (McPhail, Fisher, and McConachie Citation2009). Also, where an individual is forming a new context-specific-identity and also engaged in the identity work of discontinuing the use of another context-specific-identity, for example, a work identity, this process may be more psychologically challenging (Ashforth Citation2001). Some adult learners may seek to utilise an existing identity as a resource in this identity formation process, for instance, O’Boyle (Citation2015) describes adult learners seeking to treat university as if it were a work context. Utilising an identity in this way can cause conflict as learners find themselves trying to use identities relating to other roles that may be misplaced in an educational setting (Askham Citation2008). Turning points, or special events can have a particular impact on identity formation, for example by positively or negatively influencing a learner’s sense of belonging in or identification with the institution, and may compel engagement in concentrated identity work in order to maintain a sense of personal coherence and distinctiveness (Bell, Wieling, and Watson Citation2007; McLean, Pasupathi, and Pais Citation2007; Palmer, O’Kane, and Owens Citation2009; Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003).

The ability of an adult learner to form an identity can be hampered by the way in which higher education institutions often appear as alien cultures, perceived as negative or obstructive (Askham Citation2008; Mallman and Lee Citation2016). Institutional requirements are often perceived as invisible, unclear, and are frequently experienced as not well articulated, taken-for-granted practices that appear to be inconsistent (McAlpine and Amundsen Citation2011). Students from minority, marginalised, or disadvantaged socio-cultural backgrounds face acute challenges, particularly in relation to intersectionality, the complex interplay between gender, class, race, disability, and other identity categories relating to social inequality in higher education (Webb et al. Citation2017).

Socialisation practices impact on how newcomers to any organisation form their new context-specific-identities (Saks and Ashforth Citation1997; van der Werff and Buckley Citation2017). Many educational institutions employ activities to facilitate transition (e.g. Brunton et al. Citation2018, Citation2019; Cook and Rushton Citation2009), as support during this period can develop skills needed for longer-term success (Jones Citation2008; Nash Citation2005; Thomas et al. Citation2017). Certain activities may exclude as much as create inclusion, such as when events designed for traditional-age learners alienate older learners (Palmer, O’Kane, and Owens Citation2009). This is one example of the barriers that exist for adult learners where the institution primarily serves traditional-age learners. Such barriers will impact on identity formation and a sense of belonging as adult learners negotiate an institutional understanding of learners that runs contrary to their needs, experiences, and ways of being (Fairchild Citation2003).

Identity formation is facilitated by building relationships with peers as well as with more senior context-members, for instance with tutors or mentors in an education context (Bennet Citation2009). Socialising aids in building social networks (McAlpine and Amundsen Citation2011) and assists with a sense of belonging, which should be at the heart of efforts to improve student success (Thomas et al. Citation2017). The more that a sense of group identity is widely shared and densely articulated, the stronger the identity associated with others will be (Cole and Bruch Citation2006; Kreiner and Ashforth Citation2004). Wider social support networks, family, friends, colleagues etc., are also critical in overcoming crises and providing encouragement (Askham Citation2008; Corridan Citation2002; Fairchild Citation2003). Conversely, a lack of social integration is identifiable as a reason for withdrawal (Jones Citation2008).

Day-to-day identity management

Adult learners entering a higher education institution are not only engaged in identity formation, but also in the practical work of fitting-it-all-in, managing day-to-day changes between different context-specific-identities, for example, changing from home/family to higher education (Askham Citation2008; Bell, Wieling, and Watson Citation2007). These day-to-day identity changes can involve a physical, temporal and/or psychological component (Campbell-Clark Citation2000). The greater the contrast between identities the greater the difficulty in ‘switching cognitive gears’, disengaging from one identity and (re)engaging with another (Louis and Sutton Citation1991, 55). Adult learners typically make regular changes between valued, time-consuming contexts with tensions between identities being worked through in the day-to-day (Darab Citation2004; Fairchild Citation2003; O’Donnell and Tobbell Citation2007; Ross-Gordon, Rose, and Kasworm Citation2017). To avoid a detrimental degree of identity struggle they must actively manage their day-to-day identity work, for example, through managing relationships with family, friends, or fellow learners (Baxter and Britton Citation2001).

Stay or go?

For new adult learners, the process of forming an identity and the success with which they manage their day-to-day identity work will result in differing levels of identity struggle. These new learners need to minimise this identity struggle in order to render ‘the new, the unexpected, the strange, and the frightening more or less ordinary’ (Ashforth, Kreiner, and Fugate Citation2000; Ashforth Citation2001, 18). Learners may attempt to form their identity to fit the new context or modify the new context, physically or perceptually, to better fit their sense of themselves (Bell, Wieling, and Watson Citation2007). Mallman and Lee (Citation2016) found that adult learners may alter some practices in order to fit in, but may also resist and reinterpret other normative institutional practices, which may hinder smooth integration. Louis (Citation1980) found that dissonance caused by entering an organisation may cause newcomers to choose to leave, to renegotiate the terms of being there, or choose to accept the new context, even if it is different from their expectations.

Method

This article reports a data-led, qualitative study grounded in the constructivist paradigm, the goal of which was to examine discourse relating to the forms of identity work in which adult learners engage in their first year of higher education. The research question for this study is: How is a new adult learner’s discourse on their identity portfolio, and their engagement in identity work, affected by their entry into a higher education institution and the associated process of identity formation?

Participants and context

Participants were thirty-four, full-time, first year adult learners within two Irish higher education institutions, 16 men and 18 women. Adult learner or mature student status in the Irish higher education system means that participants were over 23 and entered their institution through specific mature student entry mechanisms. Participants were enrolled in a wide variety of programmes and varied in age from 23 to 74, with an average age of 34.6. 15 had children, 11 with children living at home, and six with children aged ten or younger. Participants had a range of occupational backgrounds and all but three had completed second-level education or higher. Participants were studying in two prestigious, (429 and 310 in the QS 2020 rankings) urban, research-driven universities that typically service traditional-age learners with a minority of adult learners.

Data collection

An idiographic approach was adopted, focusing on participants’ subjective experiences at two points in their first year of study. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews of approximately 60 min in order to achieve depth and richness in participant data. The interviews were conducted at two points, within the first four weeks of the academic year (data collection round one) and then nine months later (data collection round two) near the end of that academic year. During round one interviews participants discussed the different parts of their lives, associated identities, satisfaction with, and prioritisation of, each identity, how identities interacted, how they thought of themselves overall, and specifically about becoming a learner and early institutional experiences. During round two interviews these topics were revisited so as to explore participants’ first year experiences and their discourse on how aspects of their identity portfolio had changed.

Data analysis

Transcribed and prepared audio-recorded data was inputted into the NVivo software package and analysed using a discursive psychology analytic approach (Edwards Citation2012; Kent and Potter Citation2014; Potter and Edwards Citation2001). In this study, language was utilised as a resource in examining participant’s constructions of their identity and social world.

Data analysis was a data-driven, iterative process and was not structured by prior theory. Having read the data multiple times, the analytic process involved a first step of broadly coding by breaking data down into manageable chunks, with the researchers keeping in mind the question, how is the participant’s identity and social world being constructed in the interview? A second analytic step involved identifying the ‘pattern within language in use, the set or family of terms which are related to a particular topic or activity’ (Taylor Citation2001, 8), in this case identifying patterns within the codes in order to organise them into categories according to commonality and hierarchy of meaning. The resulting categorical system organised codes such that conceptual relationships within or between groups of codes were shown (Taylor Citation2001). Data were assigned to the parts of the categorical system to which they related. A fourth step involved review and refinement of the categorical system and data assigned to each part of the system, before finally examining the data sets assigned to each code, developing analytic points to explain that data, and producing a set of findings.

It is acknowledged that the researchers are rarely neutral parties in the research process and while adhering to tenets of objectivity they still influence the research process and are influenced in turn by that process. Researcher identity is relevant, for example, the topics under examination were chosen, to some extent, on the basis that they accord with an existing ontological and epistemological stance.

Findings

This section presents findings from the analysis of participant data, supported by data extracts. We initially offer an overview of key findings before drawing together the study’s findings under two subsections that relate to participants’ constructions of their identity work during: round one of data collection, which was within the first four weeks of participant’s first academic year; and round two data collection, which was nine months later at the end of that academic year.

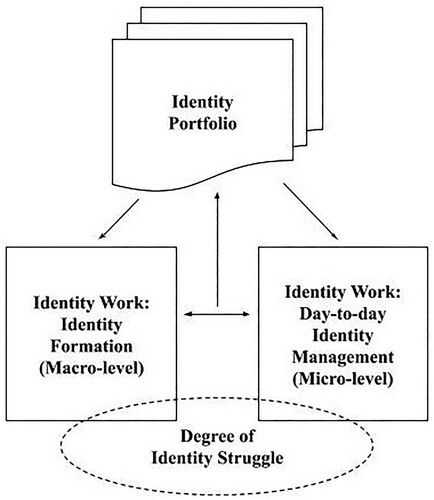

The findings show that participants constructed themselves as engaging in forms of identity work across their first year of study, and as experiencing varying degrees of identity struggle (see ). A key finding is that this identity work can be envisaged as having two interrelated forms. First, participants were identifiably engaged in the macro-level formation, development, maintenance, and augmentation of their new learner identity and changing identity portfolio, developing a story about how they were becoming adult learners and what that meant for their overall sense of themselves. Second, they were continually engaged in ongoing micro-level processes of day-to-day identity management as they changed between different context-specific-identities. These forms of identity work were shown to be interrelated. The findings demonstrate how participants’ identity formation narratives influenced how they engaged in day-to-day identity management, for example, the type of learner they saw themselves as shaped how they choose to interact with other learners. In turn, findings show how participants’ identity formation narratives were influenced by ongoing day-to-day identity management, for example during conflict between context-specific-identities. Day-to-day events in a participant’s life had to be incorporated into their identity formation narrative in order to maintain a consistent and coherent sense of themselves.

Figure 2. Two interrelated forms of identity work, influenced by a degree of identity struggle, and feeding back to the individual’s identity portfolio.

This section will first present findings relating to the identity work participants constructed as occurring before and during the start of their first year before presenting findings from round two of data collection at the end of the first year, which relate to participants’ constructions of their identity work across their whole first academic year.

Identity work at the start of the first year

In their first interviews, participants constructed identity formation narratives that moved them from how their lives used to be, to their entry into higher education, and beyond. These narratives explained how a participant was forming their learner identity and adding it to their existing identity portfolio. These narratives referenced internal and/or external factors that had facilitated or hampered this work, for example, making space for studying in their lives, reflecting on why they wanted to study, feeling a need to prove themselves to their parents, or having a lack of experience with education. Another factor that was described as hampering identity formation was the difficulty involved in making a change to their identity portfolio, to their ‘way of being’. Participant 15 describes the struggle of forming his/her student identity while also going through the process of leaving behind a highly salient work identity. He/she shared, ‘the first morning … I cried … because it’s just so emotional because you’re leaving people who … you’ve grown up with … I was very sad about it … it is very poignant … I’m finding the transition quite challenging to say the least’.

Participants constructed themselves as engaging in identity management on a day-to-day basis as they changed between different parts of their life. This was often described as challenging due to having many life-parts to which they had to attend. Participants had to manage the identity formation process and also immediately incorporate their new identity into day-to-day identity management. In the following example, participant 17 highlights the daily struggle of changing from their home/family identity to their learner identity, explaining that ‘preparation for leaving the house is a nightmare eh I mean all the physical stuff that has to be done’. Participant 17 also demonstrates how the physical separation between his/her learner identity and home/family identity helps with daily identity management, allowing segregation between the two. He/she expresses ‘on an emotional setting … it’s lovely to close the door on something and be refreshed in a new thing … I’m in college now I’ve closed the door on the house and the family … because my cell phone is off’. In the data presented above one can see the inclusion of physical, temporal, affective, and psychological elements in descriptions of day-to-day identity management of the home/family identity, the student identity, and changing between the two.

The identity work involved in forming a new learner identity and in day-to-day identity management were constructed as being interrelated. For example, Participant 20 describes how proactively refusing to take on other commitments in day-to-day interactions facilitated transition into higher education by ‘making space’ for identity formation. Participant 20 explains that he/she ‘had a … major role within a political party … I shed all that in preparation to come back to college … I kept saying no … if I hadn’t done that I would be in chaos at the moment’. Another example of this interrelationship is presented in the next subsection.

Being on the path: meaning making in participant discourse

Participants gave entry into education meaning through metaphors such as being on a path from a point in their past to one in their future. This identity work was constructed as being affected by factors such as age/life-stage development, gender, and class. Two examples involved participant discourse on changing from primarily utilising a work identity to a learner identity and from a homemaker/parent identity to a learner identity, as Participant 17 describes,

I went back to school last year … I found it really stimulating … and having something other than … are my whites as white as you know Daz promises, I’ve done it for twenty years and I’m now bored with it, I consider my family reared you know and now I want something else that’s going to be interesting.

Identity struggle

Identity struggle was described both in terms of the effortful identity work of forming a new identity and in relation to conflicts between their new identity and another salient identity. Participant 25 discussed the struggle between their new identity and his/her home/family identity,

I have to take a step back and said I don’t care if you don’t have any clean clothes or I don’t care if you starve there’s a fridge full of food you know how to cook … but it’s very hard when you’ve always done it it’s very hard to switch off no matter how hard I try I still seem to be there cooking the dinner and cleaning the clothes.

Informal and organised socialisation

Having others to identify and socialise with was constructed as facilitating participants’ transition, for example, Participant 12 shared in relation to her new social group, ‘I get great relief from talking to the other girls’. An adult learner summer school was described as helpful by attendees in that it reduced their anxiety, provided advice on preparing for study, curbed thoughts of exiting before the start of the year, and provided opportunities to socialise with other adult learners. Participant 2 described the school’s impact on her formation of a support network, ‘that’s how we met and then we all … hung out together … it was helpful … really good to find someone doing the same course as me, and he’s literally the same age as me’.

Although some descriptions of organised socialisation activities were present in the data, participants generally perceived that they had the freedom to become the learner they wished to be, within the restrictions of structures like classes, etc. Associated discourse was that of being left to ‘sink or swim’ by the institution. Participants described the university context itself as being organised so as to facilitate traditional-age students’ way of being but not that of adult learners, which contributed to their experience of identity struggle. Participant 20 described the disconnect he/she saw between university structures and family life,

I’ve worked in an equality briefing in gender equality and women’s issues and you can be pushing for family friendly stuff and all that … it ain’t family friendly when you’ve got a nine o’clock lecture or one at six or five and you’re getting out at six I mean they’re not catering for families.

Identity work across the first year

In participants’ second interviews, toward the end of their first year, descriptions of their identities had changed. For example, participants with personal missions to achieve described that goal as being tempered by an increased focus on day-to-day learner issues like achieving good marks. Discourse relating to transitioning from worker to adult learner continued, with these participants generally describing satisfaction with this change. For some, the worker identity was constructed as being more in the past than had previously been the case, as their learner identity became more dominant within their identity portfolio, as described here by Participant 15, ‘I mean my relationship with work now is purely social … because they are paying for my course, it’s purely keeping in touch’.

Discourse relating to transitioning from homemaker/parent to adult learner also continued. This discourse split between a description of satisfaction with this change and having a desire to prioritise the homemaker/parent identity over the learner identity. Participant 29 details his/her ongoing identity struggle in the interplay between these two context-specific-identities,

I’m here and then I’ll go home and I’ll cook and I’ll clean and maybe read the paper and then I have work to do and when I come into college then I’m tired you know and I’ve two children at home at the moment well adult children and my husband and I find at times I’d barely have time to talk to him you know … I’m trying to keep family first but education is kind of taking over.

Turning points

The majority of participants described significant turning points in their first year, such as their experience of completing assignments, sitting examinations, receiving results/feedback, or interpersonal interactions with other learners or academic staff. For some, examination results provided feedback that led to their ultimate decision to remain in or exit the institution. For Participant 26, receiving examination results that met his/her expectations allowed him/her to feel confident about being a learner. He/she shared,

I had always had it in my head that yeah this is good but I wonder if I’ll get my exams so they confirmed that what I’d been feeling was right it was the final confirmation … I know now I can handle this and I can handle it the way I’m going about it.

Overcoming identity struggle

How initial identity struggle was overcome, or not, was an important part of participant discourse in their second interviews. Participant 24 highlighted how he/she overcame initial identity struggle through becoming more accustomed to studying, ‘it was completely different from what I did expect it was really being dropped in at the deep end as soon as you started you were getting assignments but now it doesn’t even seem that big a deal’. Participant 1 described how their anxiety was caused by worrying about, and then overcome through, forming social networks with other learners, ‘I was a bit anxious all right … worried about how I’d get on with people … I quickly figured out who were the people I wanted to hang around with and who weren’t’. With regard to identity struggle at the macro-level of identity formation, participant 3 expressed how a sense of coherence in his/her identity portfolio, now including his/her student identity, was linked to a sense of belonging within the institution, ‘it’s totally settled in and a lot more comfortable with myself as well … being here and realising that I have a right to be here’. In contrast, Participant 21 had decided to cease his/her studies in order to eliminate the identity struggle relating to a disconnect between who they wanted to be and the academic programme as they found it, ‘at the end of four years I didn’t want to be an engineer’.

In the second round of data collection, a minority discourse was that of still feeling anxious or uncomfortable, of ongoing identity struggle. Participant 19 expressed how his/her level of identity struggle within the new identity had lessened over the course of the academic year, but was still ongoing,

I’m more comfortable now … it was really intimidating when I was coming in … to find out what is expected of you … are you going to live up to standards that you’ve set for yourself and the ones that others expect of you … it’s hard to find a middle ground that you’re comfortable with and there’s so much going on … it’s like you’re thrown in the deep end … it’s good I really do enjoy it but at the same time you’re afraid.

there was a moment when I said so that’s it now and it was … after the exams I felt that I had put in a lot of work … and I didn’t do so well … this was supposed to be fun you know … and that’s when I applied to (name of college) because I thought that would be more enjoyable.

Identity management strategies

Participant discourse included descriptions of a number of identity management strategies, for example, proactively preparing in the context of their day-to-day life. Participant 26 described using proactive planning or organising techniques,

the preparations are the key to … running my life in college efficiently being in here on time having my study time and just getting it all done, and arranging it so that I’m travelling off peak, everything else kind of fits in around that then I’ve plenty of space within that to move around then and take care of domestic issues.

after my tutorial now this evening I’ll go home, it’s an hour on the bus so you psych yourself up like who’s working who’s doing what … I … have to change my mind from college mode to home mode and I can’t be waffling on about projects and assignments they don’t seem to get it.

Discussion

This study makes three contributions to the literature on identity formation and transition to higher education. Firstly, underpinning participants’ discourse were two identity work processes constructed as taking place throughout their first year at both a macro and micro level (Bell, Wieling, and Watson Citation2007). Participants engaged in the construction of identity formation narratives and the incorporation of the new identity into their existing identity portfolio, and also in ongoing day-to-day identity management processes. This finding aligns with literature highlighting the ways in which an individual may articulate what McAlpine and Amundsen (Citation2011) refer to as an identity trajectory. Individuals weave a narrative thread connecting possibly disparate experiences into a coherent self-story integrating past, present and future experiences, providing ‘a sense of direction for the student’s perseverance and allows them to gain control over the entry/transition process’ (Palmer, O’Kane, and Owens Citation2009, 51; Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003). Participants here, as in other studies, found the transition into higher education to be an effortful and sometimes intimidating process in which their identity changed (Askham Citation2008; Mallman and Lee Citation2016; Baxter and Britton Citation2001; Kahu and Nelson Citation2018; McAlpine and Amundsen Citation2011; O’Boyle Citation2015). Those who were leaving an identity behind, for example, a salient worker identity, were engaged in that additional identity work as well as forming their new identity (Ashforth Citation2001; Louis Citation1980).

Secondly, maro-level identity formation and micro-level identity management were interrelated. Participants’ identity formation narratives influenced their perceptions of and approaches to day-to-day identity management, for example Participant 29’s wish to continue prioritising home/family life shaped how he/she divided her time between university and home (Bell, Wieling, and Watson Citation2007; McLean, Pasupathi, and Pais Citation2007). In turn, it was day-to-day events, along with how a participant dealt with them, that had to be incorporated into their identity formation narratives in order to retain a consistent and coherent sense of themselves (McLean, Pasupathi, and Pais Citation2007). For example, receiving poor examination results caused Participant 5 to alter his/her narrative to one of choosing to cease their studies.

Thirdly, findings show that participants experienced varying levels of identity struggle, influenced by internal and external factors, which impacted on both their macro and micro-level identity work, and influenced the form of their learner identity. Many participants described identity struggle as being particularly intense at the start of the year as they talked about being dropped in the deep end and their attempts to overcome what was initially perceived as strange and turn it into an ordinary part of daily life (Ashforth, Kreiner, and Fugate Citation2000; Ashforth Citation2001). Identity struggle occurred in relation to more macro-level identity work within the new identity, for example Participant 19’s struggle to form a learner identity that would be less fearful and more comfortable, and participants’ overall sense of themselves, for example Participant 21’s realisation that he/she did not want to become an engineer, that this possible future identity clashed with who he/she wished to be. This is reminiscent of Sveningsson and Alvesson’s (Citation2003) finding that while an identity narrative can be a stabilising force, it can also fuel fragmentation and conflict. Identity struggle also occurred in relation to participants’ day-to-day identity management, for example Participant 25’s feeling of being torn between the new learner identity and the home/family identity in the day-to-day (Campbell-Clark Citation2000).

Practical implications

These findings have implications for those facilitating adult learner transition into higher education, specifically with regard to factors influencing identity formation. Organised socialisation/orientation events were helpful, especially for socialisation with other adult learners, which is in line with existing literature (Brunton et al. Citation2018, Citation2019; Cook and Rushton Citation2009). In interventions, the influence of turning points should be acknowledged (McLean, Pasupathi, and Pais Citation2007; Palmer, O’Kane, and Owens Citation2009; Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003) as these can impact on the new identity, and organisers should provide positive milestones and supports to counteract the impact of negative events. Proactive preparation should be encouraged in any institutional/programme information or pre-entry orientation; as well as highlighting those factors that facilitate a smooth transition, for example, support networks, socialisation with others, realistic expectations, and those factors that can act as barriers, for example conflict between different identities; and the strategies that can be used to overcome typically-faced-difficulties, for example being organised but flexible. Broader, structural barriers for adult learners, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, should be acknowledged in this process (Fairchild Citation2003; Webb et al. Citation2017).

Study limitations

It is important to acknowledge this study’s limitations. This study focused on a relatively small group of full-time, undergraduate, adult learners in two similar Irish universities. This makes generalisation of the study’s findings challenging. However, studies whose analytic approach produces findings with depth rather than breadth add to the sum total of our understanding, and in this way the study adds to our understanding of identity formation and identity management processes in adult learners.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of examining both identity formation and day-to-day identity management processes, and the interplay between the two, in understanding the psychology of adult learner transition into higher education. This study adds to the literature used to inform the design of socialisation/orientation initiatives, for example by leveraging factors that encourage the formation of a stable learner identity and minimise identity struggle in learners’ first year.

Future research should explore the impact of socialisation/orientation initiatives designed to facilitate transition into higher education for different learner types, as well as further examine the impact of elements of the first year experience that contribute to a learner’s formation of a new learner identity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen-Collinson, J., and R. Brown. 2012. “I’m a Reddie and a Christian! Identity Negotiations Amongst First-Year University Students.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (4): 497–511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.527327.

- Anderson, M., J. Goodman, and N. K. Schlossberg. 2012. Counseling Adults in Transition: Linking Schlossberg’s Theory with Practice in a Diverse World. 4th ed. New York: Springer.

- Ashforth, B. E. 2001. Role Transitions in Organizational Life: An Identity-Based Perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ashforth, B. E., G. E. Kreiner, and M. Fugate. 2000. “All in a Day’s Work: Boundaries and Micro Role Transitions.” Academy of Management Review 25 (3): 472. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/259305

- Askham, P. 2008. “Context and Identity: Exploring Adult Learners’ Experiences of Higher Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 32 (1): 85–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770701781481.

- Baxter, A., and C. Britton. 2001. “Risk, Identity and Change: Becoming a Mature Student.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 11 (1): 87–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09620210100200066.

- Bell, N. J., E. Wieling, and W. Watson. 2007. “Narrative Processes of Identity Construction: Micro Indicators of Developmental Patterns Following Transition to University.” Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 7 (1): 1–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15283480701319559.

- Bennet, D. 2009. “Student Mentoring Prior to Entry: Getting Accurate Messages Across.” In How to Recruit and Retain Higher Education Students: A Handbook of Good Practice, edited by A. Cook and B. S. Rushton, 163–82. New York: Routledge.

- Brunton, J., M. Brown, E. Costello, and O. Farrell. 2018. “Head Start Online: Flexibility, Transitions and Student Success.” Educational Media International 55 (4): 347–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2018.1548783.

- Brunton, J., M. Brown, E. Costello, and O. Farrell. 2019. “Pre-induction Supports for Flexible Learners: The Head Start Online MOOC Pilot. A Practice Report.” Student Success 10 (1): 155–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v10i1.434.

- Campbell-Clark, S. 2000. “Work/Family Border Theory: A New Theory of Work/Family Balance.” Human Relations 53 (6): 747–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700536001.

- Cole, M. S., and H. Bruch. 2006. “Organizational Identity Strength, Identification, and Commitment and Their Relationships to Turnover Intention: Does Organizational Hierarchy Matter?” Journal of Organizational Behaviour 27 (5): 585–605. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/job.378.

- Cook, A., and B. S. Rushton, eds. 2009. How to Recruit and Retain Higher Education Students: A Handbook of Good Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Corridan, M. 2002. Moving from the Margins: A Study of Male Participation in Adult Literacy Education. Dublin: Dublin Adult Learning Centre.

- Darab, S. 2004. “Time and Study: Open Foundation Female Students’ Integration of Study with Family, Work and Social Obligations.” Australian Journal of Adult Learning 44 (3): 327–53.

- Ecclestone, K., G. Biesta, and M. Hughes. 2010. “The Role of Identity, Agency and Structure.” In Transitions and Learning Through the Lifecourse, edited by K. Ecclestone, G. Biesta, and M. Hughes, 1–15. New York: Routledge.

- Edwards, D. 2012. “Discursive and Scientific Psychology.” British Journal of Social Psychology 51: 425–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2012.02103.x.

- European Commission. 2014. Report to the European Commission on new Models of Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Fairchild, E. E. 2003. “Multiple Roles of Adult Learners.” New Directions for Student Services 102: 11–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.84.

- Gale, T., and S. Parker. 2014. “Navigating Change: A Typology of Student Transition in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (5): 734–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.721351.

- Higher Education Authority (HEA). 2015. National Plan for Equity of Access to Higher Education 2015–2019. Accessed January 18, 2019, https://hea.ie/assets/uploads/2017/06/National-Plan-for-Equity-of-Access-to-Higher-Education-2015-2019.pdf.

- Jones, R. 2008. Widening Participation: Student Retention and Success. Research Synthesis for the Higher Education Academy. Accessed January 18, 2019, https://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/ssds/projects/student-retention-project/dissemination/resources/wp-retention-synthesis.doc.

- Kahu, E. R., and K. Nelson. 2018. “Student Engagement in the Educational Interface: Understanding the Mechanisms of Student Success.” Higher Education Research & Development 37 (1): 58–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197.

- Kent, A., and J. Potter. 2014. “Discursive Social Psychology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Social Psychology, edited by T. M. Holtgraves, 295–314. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kreiner, G. E., and B. E. Ashforth. 2004. “Evidence Toward an Expanded Model of Organizational Identification.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 25: 1–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/job.234.

- Leonard, N. H., L. L. Beauvais, and R. W. Scholl. 1999. “Work Motivation: The Incorporation of Self-Concept-Based Processes.” Human Relations 52 (8): 969–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016927507008.

- Louis, M. R. 1980. “Surprise and Sensemaking: What Newcomers Experience Entering Unfamiliar Organizational Settings.” Administrative Science Quarterly 25: 226–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2392453.

- Louis, M. R., and R. I. Sutton. 1991. “Switching Cognitive Gears: From Habits of Mind to Active Thinking.” Human Relations 44: 55–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679104400104.

- Mallman, M., and H. Lee. 2016. “Stigmatised Learners: Mature-Age Students Negotiating University Culture.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 37 (5): 684–701. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2014.973017.

- McAlpine, L., and C. Amundsen. 2011. “Making Meaning of Diverse Experiences: Constructing an Identity Through Time.” In Doctoral Education: Research-Based Strategies for Doctoral Students, Supervisors and Administrators, edited by Lynn McAlpine and Cheryl Amundsen, 173–84. Amsterdam: Springer.

- McLean, N. 2012. “Researching Academic Identity: Using Discursive Psychology as an Approach.” International Journal for Academic Development 17 (2): 97–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2011.599596.

- McLean, K. C., M. Pasupathi, and J. L. Pais. 2007. “Selves Creating Stories Creating Selves: A Process Model of Self-Development.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 11 (3): 262–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868307301034.

- McLean, N., and L. Price. 2019. “Identity Formation among Novice Academic Teachers – a Longitudinal Study.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (6): 990–1003. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1405254.

- McPhail, R., R. Fisher, and J. McConachie. 2009. Becoming a Successful First Year Undergraduate: When Expectations and Reality Collide. Accessed January 18, 2019, https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au/bitstream/handle/10072/31840/55759_1.pdf?sequence=1.

- Mehmet, K., F. Erdogdu, M. Kokoç, and K. Cagiltay. 2019. “Challenges Faced by Adult Learners in Online Distance Education: A Literature Review.” Open Praxis 11 (1): 5–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.11.1.929

- Mercer, J. 2007. “Re-Negotiating the Self Through Educational Development: Mature Students’ Experiences.” Research in Post-Compulsory Education 12 (1): 19–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13596740601155314.

- Nash, R. D. 2005. “Course Completion Rates among Distance Learners: Identifying Possible Methods to Improve Retention.” Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration 8 (4). https://www.westga.edu/.

- O’Boyle, N. 2015. “The Risks of ‘University Speak’: Relationship Management and Identity Negotiation by Mature Students off Campus.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 25 (2): 93–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2015.1018921.

- O’Donnell, V. L., and J. Tobbell. 2007. “The Transition of Adult Students to Higher Education: Legitimate Peripheral Participation in a Community of Practice?” Adult Education Quarterly 57 (4): 312–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713607302686.

- OECD. 2015. Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators. Accessed January 18, 2019, https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance-2015.htm.

- Palmer, M., P. O’Kane, and M. Owens. 2009. “Betwixt Spaces: Student Accounts of Turning Point Experiences in the First-Year Transition.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (1): 37–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802601929.

- Potter, J., and D. Edwards. 2001. “Discursive Social Psychology.” In The New Handbook of Language and Social Psychology, edited by W. P. Robinson and H. Giles, 103–18. London: John Wiley.

- Richardson, J. T. E., and E. Kind. 1998. “Adult Students in Higher Education: Burden or Boon?” Journal of Higher Education 69 (1): 65–88.

- Ross-Gordon, J. M., A. D. Rose, and C. E. Kasworm. 2017. Foundations of Adult and Continuing Education. San Francisco: Wiley.

- Saks, A. M., and B. E. Ashforth. 1997. “Organizational Socialization: Making Sense of the Past and Present as a Prologue for the Future.” Journal of Vocational Behaviour 51: 234–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1997.1614.

- Stapleton, K., and J. Wilson. 2003. “Grounding the Discursive Self: A Case Study in ISA and Discursive Psychology.” In Analysing Identity: Cross-Cultural, Societal and Clinical Contexts, edited by P. Weinreich and W. Saunderson, 195–212. London: Routledge.

- Sveningsson, S., and M. Alvesson. 2003. “Managing Managerial Identities: Organizational Fragmentation, Discourse and Identity Struggle.” Human Relations 56 (10): 1163–93. doi https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035610001.

- Taylor, S. 2001. “Locating and Conducting Discourse Analytic Research.” In Discourse as Data: A Guide for Analysis, edited by M. Wetherell, S. Taylor, and S. J. Yates, 5–48. London: Sage.

- Thomas, L., M. Hill, J. O’ Mahony, and M. Yorke. 2017. Supporting Student Success: Strategies for Institutional Change: What Works? Student Retention & Success Program. Accessed January 18, 2019. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/supporting-student-success-strategies-institutional-change.

- van der Werff, L., and F. Buckley. 2017. “Getting to Know You: A Longitudinal Examination of Trust Cues and Trust Development During Socialization.” Journal of Management 43 (3): 742–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314543475.

- Webb, S., P. J. Burke, S. Nichols, S. Roberts, G. Stahl, S. Threadgold, and J. Wilkinson. 2017. “Thinking with and Beyond Bourdieu in Widening Higher Education Participation.” Studies in Continuing Education 39 (2): 138–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2017.1302926.

- Willans, J., and K. Seary. 2011. “I Feel Like I’m Being Hit from All Directions: Enduring the Bombardment as a Mature-Age Learner Returning to Formal Learning.” Australian Journal of Adult Learning 51 (1): 119–42.