ABSTRACT

The concept of student partnership has attracted increased attention during the last decade, often due to an assumption that it can mitigate neo-liberal agendas and practices in teaching and learning. A review of definitions and understandings of student partnership models shows that most of the research conducted on this topic has been based on normative assumptions, with less focus on how partnership practices play out in different contexts. In this article an analytical framework for analysing student partnership is introduced and tested through an empirical analysis of collaborative practices in centres for teaching excellence in Norwegian higher education. The key findings are that the diversity and dynamics of student partnership depend on the context in which they operate, but more importantly how different practices of partnership play out in parallel in those educational contexts. The result is often a mix of hybrid practices related to different conceptualizations of student partnership.

Introduction

In the literature on teaching and learning in higher education, concepts such as student involvement, student engagement, student participation and student partnership have gained considerable interest (Klemencic Citation2011; Bovill and Bulley Citation2011; Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014; Ashwin and McVitty Citation2015). These concepts can be understood in different ways: as indications of attempts to foster more student-centred teaching, as a reaction to neo-liberal reforms in higher education, or even as a renewal and a re-interpretation of more historical university ideas (Bovill Citation2012; Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014; McCulloch Citation2009).

Over the last decade, the concept of student partnership has inspired both theoretical contributions and institutional reform initiatives, especially in the UK, USA, Canada, the Nordic countries and Australia (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2016; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017; Bovill and Woolmer Citation2019). Beyond this, student partnership has found its place in national policy initiatives. For example, in Norway student partnership is a key requirement for those applying for status as national Centres for Excellence in Education. However, many empirical studies on student partnership have been characterized as small scale, based on participants’ self-reports (Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017) and lacking a solid theoretical basis (Matthews et al. Citation2019). It is acknowledged, that more complicated contexts for partnership require additional theoretical contributions (e.g. Mercer-Mapstone and Bovill Citation2019).

Even though there is a wide spectrum of possible partnership and co-creation (with students) forms, areas and implementation possibilities (Bovill Citation2019b), there is still a lack of literature observing institutional pathways towards student partnership and how partnerships develop over time. Many contributions are focused on overcoming challenges (Bovill et al. Citation2016; Cook-Sather, Bovill, and Felten Citation2014; Mercer-Mapstone and Bovill Citation2019) or integrating a value-based partnership concept in today’s neo-liberal universities (Matthews et al. Citation2019; Gravett, Kinchin, and Winstone Citation2019). Historically, the student role in higher education has been strongly affected by the development of universities as institutions (Maassen and Olsen Citation2007). As the universities’ missions and values changed, so has the role of the students. Therefore, there is a need to reflect on different ways practices can be developed at universities, through adding an institutional perspective to the partnership debate. Consequently, the aim of this article is to contribute to the existing student partnership literature offering an institutional perspective towards partnership development and dynamics.

The article is organized as follows. We start by presenting a review of the literature on student partnership, the key conceptualizations found in recent research, mostly used partnership models and implementation issues. Next, a theoretical framework is introduced where different understandings of student partnership are proposed. This framework is tested empirically by an analysis of how student partnership is playing out in three centres of teaching excellence in Norwegian higher education. We conclude the article by suggesting avenues for further research.

The literature on student partnership

The concept of student partnership has its origins in the call for more democratic approaches to education and critical pedagogy (Bovill Citation2012), which ‘has played a significant role in our current understanding of student–staff partnerships’ (Bovill Citation2019b, 6). Critical pedagogy connects student learning with political commitments, such as ‘serve democratic ends, connect with societal issues or to promote social justice’ (Buckley Citation2014, 12). Student partnership has developed as a contra-narrative to a consumeristic approach to education (Matthews et al. Citation2018; Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014; Gravett, Kinchin, and Winstone Citation2019; Williamson Citation2013). Student partnership stresses that ‘students actively participate in shaping and co-producing their education, rather than merely receiving it passively’ (Williamson Citation2013, 8).

One of the most frequently used definitions of student partnership is provided by Cook-Sather, Bovill and Felten:

a collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualization, decision-making, implementation, investigation, or analysis. (Citation2014, 6–7)

Partnership is characterized as a process of engagement, ‘a way of doing things, rather than an outcome in itself’ (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014, 12). There is no doubt that partnership is a value-based concept. Healey, Flint, and Harrington (Citation2014) provide a full list of values, which should be underpinned around partnership practices: authenticity, inclusivity, reciprocity, empowerment, trust, challenge, community and responsibility. Student partnership is referred to in the literature as a threshold concept in academic development, as an idea intended to make a change in mindsets regarding teaching and learning (Cook-Sather Citation2014), as having potential to make a cultural shift (Cook-Sather, Bovill, and Felten Citation2014). Due to its value-based approach, partnership should become a desired ‘way of doing things’, a role model to the universities.

In practice, student partnership has become an umbrella for a broad range of practices differing in their forms, scale and areas of implementation (Bovill Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017; Mercer-Mapstone and Bovill Citation2019; Healey and Healey Citation2018). The variety of partnership practices has been discussed in the literature (see Bovill Citation2019a, Citation2019b), and several frameworks for exploring different aspects of partnership have been developed. The different areas for partnership have been identified by the influentialFootnote1 framework developed by Healey, Flint, and Harrington (Citation2014): learning, teaching and assessment; subject-based research and inquiry; scholarship of teaching and learning; curriculum design and pedagogic consultancy. There are also some examples of literature conceptualizing student partnership at a higher level than curricula. For example, Ashwin and McVitty (Citation2015) explored student partnership in formation of communities, and Klemencic (Citation2011) defined student partnership in governance. The roles students play in cooperation with the staff have been investigated by Bovill et al. (Citation2016) and Dunne and Zandstra (Citation2011) – from students as co-researchers to students as representatives. In addition to these models, the literature provides a number of frameworks focusing on engagement or participation levels, which include student partnership as one of the highest levels or stages in the scale to be achieved (Bovill and Bulley Citation2011; Ashwin and McVitty Citation2015; Klemencic Citation2011; Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014). Some of these frameworks are positioned in the partnership literature (like Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014), others include partnership as one of the possibilities to engage with the students (e.g. Ashwin and McVitty Citation2015; Dunne and Zandstra Citation2011). Altogether, the developed frameworks or typologies provide a useful tool to map existing and develop new student partnership / participation forms.

There is no doubt that ‘students as partners’ has become an attractive concept. A variety of practices related to student partnership has found its way into university strategies (Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017; Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2016; Mercer-Mapstone and Bovill Citation2019) and national programmes or initiatives (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2016). In a systematic literature review, Mercer-Mapstone et al. (Citation2017) found 65 empirical studies performed in the years 2011–2015 investigating various partnership practices. Many contributions in the implementation literature concentrate on challenges to overcome in order to implement partnership practices. For example, Bovill et al. (Citation2016) argued that individual biases, fears and perceptions of risks in redefining the student and staff roles, institutional norms and inclusivity of the students in partnerships are the challenges for co-creation in partnership practices. There are some issues related to the scaling up of partnership practices identified in the literature, such as sustainability of partnership initiatives (Mercer-Mapstone and Bovill Citation2019; Cook-Sather, Bovill, and Felten Citation2014) and providing access to all the students (Mercer-Mapstone and Bovill Citation2019). Finally, there is a discussion in the literature whether a neo-liberal focus in universities is a challenge for partnership implementation or not (see Matthews et al. Citation2018; Gravett, Kinchin, and Winstone Citation2019; Mercer-Mapstone and Bovill Citation2019; Bovill Citation2019b). In essence, many contributions in the literature concentrating on partnership implementation within universities are focused on ways to reconstruct these institutions (as well as the mindsets of their staff) to fit the value-based partnership concept.

Among the main scholars addressing student partnership in their work there is an ongoing debate regarding the theorizing of the concept of ‘partnership’. For example, Bovill (Citation2019b) argues that it has a firm theoretical background coming from critical pedagogy and should be used together with engagement and co-creation theories. Other authors suggest that student partnership is an under-theorized area (Gravett, Kinchin, and Winstone Citation2019; Matthews et al. Citation2019). Matthews et al. claim (Citation2019, 11) that theorizing in this area can be ‘creative and emancipatory’. They apply Trowler’s notion of the use of theory ‘in the imaginarium’, when ‘theory does not just describe the world but seeks to change it’ (Trowler Citation2012, 277). Consequently, Matthews et al. (Citation2019) invite more theories to be built on existing partnership practices.

The current article aims at contributing to the literature by analysing existing partnership practices in relation to their institutional embedding and dynamics. In order to be able to perform such a study in line with the proposed ‘theory being built on existing practices’ approach, it is crucial to expand a scope of a value-based partnership definition described in the literature. As Healey and Healey (Citation2018, 1) suggest ‘the breadth and complexity of practices and policies surrounding SaP [students as partners] mean that it is often difficult to make generalizations’. The authors strongly advice against a one-size-fits-all approach to student partnership and encourage studies to put more emphasis on the context (Healey and Healey Citation2018). Student partnership could be understood as a lens to be used to understand teaching and learning interactions (Ashwin Citation2009). Consequently, the current study keeps the partnership concept more open than the value-based partnership definition proposed in most of the literature. As point of departure, we apply the definition proposed by Cook-Sather, Bovill, and Felten (Citation2014) of partnership as a process where ‘all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally’ (6–7), yet we choose to analyse various participation practices in regard to the different underlying institutional norms and values that determine their dynamics.

Analytical framework

Historically, the role of students has been in a constant change in regard to the development of universities as institutions (Maassen and Olsen Citation2007). For example, in the Humboldtian university, students were seen as contributors to shared inquiry, together with the professors seeking to develop knowledge (Karseth and Solbrekke Citation2016). The bond between students and their university was very tight (Pritchard Citation2004). From the 1960s on the democratization movements made a huge impact on student roles at universities. The students fought together with the non-professorial academic staff for more democratic governance structures inside the university as well as against universities being used as an instrument for national political agendas (Boer and Stensaker Citation2007). More recently, neo-liberalism and the concept of new public management gave students a different place, positioning them in a number of respects as the customers or clients of universities (Meek Citation2003). Hence, the role of the students in the development of higher education changed in line with changes in important institutional features of universities.

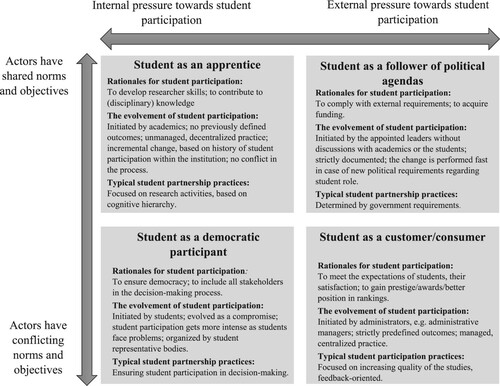

Based on an institutional perspective, Olsen (Citation2007) has developed a framework consisting of four stylized visions (or models) on university governance and organization, which offers an analytical lens for identifying different ways of understanding student partnership and its development. Our analytical framework for student partnership dynamics presented below builds on these visions where ‘ideal’ student partnership types in educational practices are put on two axes: external vs. internal pressure (toward student participation) and consensus vs. conflicting norms and objectives of the actors (see ).

Figure 1. The student partnership framework (Based on Olsen Citation2007, 30).

The ‘Student as an apprentice’ partnership type is based on the Humboldtian university vision. Internal pressure towards student participation and consensus among actors are the characteristics of this partnership type. Students as well as the professors have shared goals: the pursuit of knowledge, or self-development (Bildung). The development of student partnership practices emerges gradually, in mutual agreement. Student participation is mostly linked to common work in research or at least aimed at enhancing student understanding of the scientific endeavour and teaching them to develop inquiry skills. Student participation in co-creation activities is usually initiated by the senior academic staff and students, as younger colleagues would follow in consensus.

The ‘Student as a follower of political agendas’ partnership type is based on Olsen’s (Citation2007, 31) vision of the university as an instrument for shifting national political agendas. In this ‘ideal’ partnership type, the pressure towards student participation is external and partnership practices are developed in consensus. Students and academics have a common goal – to correspond to political decisions in order to gain support and funding from the government. In this partnership type, the need for student participation is deemed from the requirements of the national or transnational government. Students would be invited to committees or meetings; student participation practices would have a formal character. Student participation forms would be developed by the appointed leaders based on political decisions according to the official requirements regarding student participation.

The ‘Student as democratic participant’ partnership type is based on Olsen’s (Citation2007, 32) university as a representative democracy vision. This model is related to the democratization processes starting in the 1960s and can be understood as student voice. Hence, a student’s role as a democratic participant is driven by democratic ideals, by the wish to empower the students. This partnership type imposes the pressure towards student participation to be internal (mostly student-driven) and practices to be originated from the conflicting objectives of the parties. The demands of the students to get more influence over their education would result in them getting more decision power in university [governance] structures. Partnership practices would be developed in the process of bargaining and alliancing between student organizations and university staff. Describing this university vision Olsen claims that ‘focus [of student participation] is upon formal arrangements of organization and governance’ (Citation2007, 32). Examples of these formal arrangements and governance bodies in today’s university could be various quality assurance bodies (e.g. programme committees) and representation in university governance bodies, such as central university boards.

The ‘Student as a customer/consumer’ partnership type is based on Olsen’s university as a service enterprise vision (Olsen Citation2007, 32–33). External pressure towards student participation and conflicting objectives of the actors are the characteristics of this partnership type, in which students are understood as (external) consumers of university services. That implies that the university, managed according to new public management principles, is basically reacting to market needs. If students / prospective students or other parties (employers, business) see student participation as a value, the university reacts to that need in the market and develops new student partnership forms. Developed partnership forms would concentrate on provision of student feedback or other practices aimed at increasing the quality of study programmes and would be actively used in universities’ marketing strategies. In this ‘ideal’ partnership type student participation has predefined outcomes, established following managerial principles.

In practice, the four ‘ideal’ student partnership types are not exclusive, and neither are Olsen’s (Citation2007) university visions; they co-exist and overlap. All of them are addressing specific dynamics in student partnership, yet, all of them are assumed to do that in a different way. Therefore, the aim of this analytical framework is to connect the student partnership with an institutional setting and to observe different drivers shaping the basic institutional student partnership approach in practice.

Empirical context and research design

Norwegian centres for excellence in education

To test our student partnership framework, we conducted an analysis of student participation practices within Centres for Excellence in Education (CEE) in Norwegian higher education. Norway, as a part of the Nordic region, has a strong democratic tradition with an emphasis on equality and trust in society (Christensen, Gornitzka, and Maassen Citation2014). Nordic values in higher education are expressed in a number of ways, including through continuous high levels of public funding and tuition-free education (Christensen, Gornitzka, and Maassen Citation2014). The scarce studies of student roles in Norwegian higher education indicate that democratic values and practices remain important among the students (Stensaker and Michelsen Citation2011; Jungblut, Vukasovic, and Stensaker Citation2015). Yet, the question can be raised how recent policy trends affected these basic values in Norwegian higher education. The national political context for Norwegian higher education is still very different from more countries that are more fundamentally market-oriented in their higher education governance model, such as the UK, USA or Australia, where the student partnership concept has been more influential.

The CEE initiative started in 2010, and the ‘students as partners’ rhetoric was featured prominently when the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research launched it. The partnership rhetoric was also embedded in the specific expectations formulated by the agency responsible for implementing the initiative (Nokut Citation2016), with significant results (see more in Helseth et al. Citation2019). During the period 2011–2017 eight CEEs have been established across the country. In terms of student partnership practices, a high variation can be observed among institutions hosting one or more of the Centres – including some very successful student-led learning initiatives and students acting as change agents (Helseth et al. Citation2019). Consequently, CEEs provide highly relevant cases for examining the different understandings and practices related to student partnership practices.

Data and methods

The underlying study is qualitative and exploratory, with a multiple case study design (Yin Citation2009). The study’s goal was not to compare the different CEEs and their student participation models per se, but rather to explore the dynamics of student participation practices and the ways in which they were developed. The multiple case design has provided adequate possibilities to test the relevance and validity of our framework. For this purpose, three out of the current eight Norwegian CEEs have been selected:

BioCEED (Center for Excellence in Biology Education, University of Bergen), CEE from 2014,

MatRIC (Center for Research, Innovation and Coordination of Mathematics Teaching, University of Agder), CEE from 2014,

ExcITEd (Center for Excellent Information Technology Education, NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology), CEE from 2016/2017.

The selection was made on the basis of the following criteria: (1) the centres had to belong to different universities as the institutional setting was under investigation; (2) the level within the university where a centre is established (at the department level vs institutional level); and (3) the years of establishment – the updated requirements from 2016 indicated that centres should plan how to involve students in educational developments and innovations, while this was not mentioned in the previous requirements (Nokut Citation2013, Citation2016).

Data for this study were collected using document analysis, semi-structured interviews and focus groups at the premises of the selected centres.Footnote2 Firstly, the document analysis has been performed using applications, yearly reports and midterm self-evaluations of the centres. Secondly, semi-structured interviews were conducted with staff members and student representatives – in total 7 individual interviews. Prospective interviewees were selected using snowball sampling, they were proposed by an institutional contact person as being able to contribute to the revelations of student partnership patterns at the centres. Finally, the group interviews were performed with students participating at the centres’ activities, 13 students in total, divided into 3 groups (for each of the centres). The semi-structured interviews and group discussions were audio recorded. The study has been performed according to the requirements of the Norwegian Social Science Data Services.

Findings

Each of the investigated Centres for Excellence in Education has developed its own distinctive student partnership approach consisting of several student participation practices. The practices ranged from the provision of feedback, to students owning the process. In each centre, at least three parallel practices involving students were detected. The practices found at the centres mainly fall into two areas: student representation in decision-making and student participation in the projects developed by the centre. Student participation in decision-making at the centres was performed by the student representatives, in two of them organized as unpaid, voluntary activity. In contrast, student involvement in projects was organized in the form of part time jobs where students were selected through an application process. The centres acted as additional enhancement units having a tight connection, but no responsibility for the implementation of curricula. The student participation practices, their rationales and development processes have been analysed by using the student partnership framework based on Olsen’s (Citation2007) four stylized university visions. The main findings will be presented in the following sections.

Student as an apprentice

Including students in the teaching, learning and research developments was one of the main areas for student involvement at the selected centres. The NOKUT CEE programme requirements from 2016 indicated that CEEs should plan how to involve students in educational developments and innovations, while this was not mentioned in the previous requirements (Nokut Citation2013, Citation2016). Yet all three centres (established in 2013 and 2016) have involved students (to a different degree) in the design and/or implementation of educational developments or innovations, mostly organized as projects. The traditional Humboldtian rationale, such as ‘to develop researcher’s skills’ was mentioned in one of the centres which implemented a research assistant programme. In this programme the professors worked together with the students treating them as less experienced colleagues and providing various research-related assignments (e.g. preparing articles together with professors, assisting in empirical work). In the remaining two centres, students contributed in certain mentoring or student teaching programmes – as ‘older students’ teaching and sharing experiences with ‘younger students’. An example of this practice is additional consultations provided by the mentoring students at a set time for clarification of a subject. Even though the mentoring or student teaching practices could not be assigned to the ‘ideal’ ‘student as an apprentice’ partnership type (due to the emphasis on relevant skills instead of the disciplinary knowledge), this practice is based on cognitive hierarchy, which is one of the features of the apprentice partnership type as well as the Humboldtian university model (Nybom Citation2007).

One of the centres provided an example of student partnership following some of the principles that characterize the ‘student as an apprentice’ type (see ). At this centre a change of the student partnership practices was slow, incremental, unplanned and unmanaged – no one remembered exact dates, there was no formal decision to start something or stop something, just someone who suggested, and others agreed. Both internal parties, students and staff were involved in initiating the change in mutual agreement. Even the dissemination of their student partnership practices was performed in a decentralized nature – another department heard about their practice and tried to implement something similar.

Student as a follower of political agendas

It is interesting that the CEE initiative was developed as a programme aimed at providing selected higher education institutions with earmarked funding. There is no doubt that Nokut, as a coordinator and administrator of this programme for many years, has been an important change driver regarding student participation approaches. Firstly, it was embedded into the requirements for funding. Secondly, Nokut provided support for more intensive student participation (e.g. providing funding for student driven projects; inviting institutions to student partnership workshops). Political influence as a driver for developing new student participation practices has been mentioned by two centres in the interviews. One of the respondents claimed that ‘one thing that came out from the previous round where we didn’t succeed was that some student involvement during the application process is so important’. That was the reason for the centre to increase the students’ role in the application process. The second centre took its biggest step in student partnership development as a result of its participation in the workshop ‘Students as partners’ initiated by Nokut.

In essence, some student partnership practices have been developed as a direct result of political pressure, for example, student participation in the CEE application process. Yet, following the official requirements for student participation, the centres expanded their student partnership practices according to their institutional needs. For example, in the requirements it is indicated that ‘Student participation [in management and organization] at all levels is essential’ (Nokut Citation2016, 9). At the same time, all the centres developed their own unique ways to ensure student representation in governance, at least two of them increased the number of student representatives during their operational time.

Student as a customer/consumer

All three centres had an element of this student partnership type in their rationales. This is also visible in the ways in which most staff indicated in the interviews their interest in feedback for the activities of the centre. As an example, one staff member indicated that students provide ‘very good suggestions how we can be better’. In another centre, the students’ position as the customers of education was mentioned:

… as well it is necessary to work [with them] … because they are our main target and basically our customers, we have to work for them, we have to work well for them.

On the other hand, systematic feedback collection was a relatively insignificant part of the whole student partnership practice. Discussing feedback practices during the interviews, it was mostly indicated that it is crucial to have students participating at the time of decision-making. In this case, students can provide immediate feedback – to help include a students’ perspective before launching a new activity or making changes.

In terms of student partnership practice development, one of the centres provided an example of the process following some of the managerial principles. Despite the fact that students were involved in the development of the concept, further operational issues were mostly decided by staff. The launch of a new teaching assistant programme was sudden and performed at a high scale (started with 30 students, expanded to 80 students in two years). The practice quickly became centralized, it was introduced to the institutional level at the time of the interviews. The developed practice itself was aimed at facilitating student learning, improving quality of studies, reducing drop-out rates. On the other hand, the ‘response to the market needs’ element was not observed in the interviews. The drivers for the change were external political pressure as well as internal needs.

Student as a democratic representative

All of the centres ended up implementing some form of student representation. However, it is important to notice that the student representation in governance was embedded in the requirements for the funding. Typical student participation in governance rationales, such as ‘democracy’, ‘ensuring students’ voice to be heard’ were mentioned only by one interviewee. Yet, it should not be assumed that the student representation function is unimportant to the centres. On the contrary, the information from the interviews suggests that the ability of representing multiple student voices has been set as an important expectation for student representatives at the centres. One respondent pinpointed that ‘we expect to hear not only their voice as representatives but to hear how all the students feel about the world here’. In addition, the variety of established student representation forms indicates that it is high on the agenda in the centres. For example, at one of the centres its student representation structure is holding the main responsibility for student-driven activities. In another centre, the student representative is a full-time paid position.

Finally, the development process of student participation practices had not much in common with the ideal ‘student as a democratic participant’ type. In two of the centres the student organizations were important in the implementation of their student partnership approach, yet, the components not observed in the interviews were conflict and high pressure towards the change coming from the students.

Discussion

Based on the underlying study, we argue that when analysing student partnership practices at a group level, several different pathways towards partnership can be identified. These are often influenced by the specific institutional context of the educational practices and they demonstrate the dynamic nature of partnerships. When analysing student partnership at an individual level, we still find that most students are exposed to more specific practices, with a high variety when it comes to the nature and level of `partnership`. Importantly, students can engage in the same educational practices in ways that are aligned to very different partnership understandings.

In the findings, we observed a range of group level practices reflecting all four cells of our student partnership framework (see ). Students participate in application processes, student input is gathered in the form of feedback, students work with professors as research assistants and, finally, students play a role in institutional governance and decision-making. This variety reflects in many ways the diversity of student partnership practices. Indeed, students play various roles like those proposed by Bovill et al. (Citation2016) and Dunne and Zandstra (Citation2011), and the intensity of their participation differs from being consulted to owning the process (as proposed by Ashwin and McVitty Citation2015; Bovill and Bulley Citation2011).

Primarily, in the Norwegian CEE initiative, the focus in student partnership is on teaching, and learning developments and innovations in this are to a large extent anchored in the political expectations. Strikingly, these kinds of innovations are implemented in all of the selected cases. It corresponds to the observed trend in the partnership literature – many practices investigated are being aimed at teaching and learning improvements and curricular developments (Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017). In addition, our analysis also revealed that the student role in governance and representation has been high on the agenda for the centres. The importance of representation and students participating in institutional governance might be explained by the unique Norwegian higher education context. Norwegian education still relies on strong democratic traditions, trust and equality in the society (Christensen, Gornitzka, and Maassen Citation2014), and democratic values and practices remain important among the students (Stensaker and Michelsen Citation2011; Jungblut, Vukasovic, and Stensaker Citation2015).

The Norwegian context also illustrates how many apparently contradictory practices and rationales do not necessarily interfere with each other. Our findings highlight that neo-liberal influences do not hinder tight collaboration practices in other areas, opposing a number of sceptics of a consumeristic approach to student participation (e.g. Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2014; McCulloch Citation2009). Publicly funded Norwegian universities and tuition-free education provide a very different setting than highly-marketized contexts found in other countries. Indeed, as suggested by Bovill (Citation2019b), ‘a taste of competition’ might drive institutions to an understanding that engagement and partnership could be a strategy to realize positive student experiences.

Our analysis indicates that student partnership has a multi-faceted character, in the sense that student participation practices are underpinned and exist next to each other. This reflects Olsen’s (Citation2007) argument that his four university visions are not exclusive. At the same time, the multi-faceted character of the practices leaves little room for prediction. Political rationales might lead to collaborative practices in decision-making processes or consumeristic rationales – as well as to the partnership practices aimed at teaching and learning improvements. In addition, the findings indicate that many practices as well as their rationales and development processes have some features of more than one of the four ‘ideal’ partnership types and can therefore not be placed exactly in only one of the cells of our analytical framework (see ). Finally, our framework does not provide a normative definition of ‘partnership’. While it might be controversial to think of the ‘student as a customer’ as an ideal-type of partnership, we propose that the field is in need of partnership types that reflect the complexity of how students value and view higher education (cf. Jungblut, Vukasovic, and Stensaker Citation2015). We argue that ‘partnership’ most often is being found as a sum of various student participation practices, which vary depending on the institutional context.

The strength of our framework is that it hints to the dynamics around student collaborative practices. In fact, it helps to visualize the partnership as a dynamic and constantly changing process. For example, external political pressure has been functioning in many ways as a catalyst for launching student participation practices. Yet, most practices have been shaped within institutions as a result of institutional change processes. The emphasis on dynamics of practices is an important contribution to existing partnership frameworks mostly mapping final partnership forms.

Conclusions

The findings show that as student partnership is gaining momentum in more complicated institutional and national contexts, we consequently need to apply multiple models if we are to understand partnership practices. Student partnership is highly dynamic and multi-faceted and is experienced in multiple ways by the involved students. Student partnership has also infused the national policy agenda and because of the increased focus on attracting and retaining students in higher education, both consumer ideas and political legitimacy embed the practices identified. Still, within this context, we clearly see also examples of what can be interpreted as ‘apprentice’ and ‘democratic participant’ partnership types. As such, the Olsen framework is indeed useful as an analytical tool for examining the dynamic complexity surrounding partnership practices.

This latter point, we would argue, is of great interest to pursue for further research as our data suggest that there are hybrid and quite complex partnership practices in the `boundary areas` between the ideal-type forms of student partnership included in our framework. Our finding is that political pressure ends up fostering internal incentives towards partnership. A question to pursue for the future is whether the same also applies to the partnership practices developed as a response to market needs. Alternatively: do partnership models based on democratic ideals run the danger of pushing students into being political followers? These are some of the questions that are relevant to address in future research on how different ideas underlying student partnership play out in practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors are most grateful to the research participants for their support in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 This framework guided a number of empirical studies, has been practically applied by various organisations (Healey, Flint, and Harrington Citation2016).

2 The authors would like to thank Nokut (the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education) for their support in the implementation of the empirical study.

References

- Ashwin, P. 2009. Analysing Teaching-Learning Interactions in Higher Education: Accounting for Structure and Agency. London: Continuum International Pub. Group.

- Ashwin, P., and D. McVitty. 2015. “The Meanings of Student Engagement: Implications for Policies and Practices.” In The European Higher Education Area: Between Critical Reflections and Future Policies, edited by A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Procopie, J. Salmi, and P. Scott, 343–59. Cham: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_23

- Boer, H., and B. Stensaker. 2007. “An Internal Representative System: The Democratic Vision.” In University Dynamics and European Integration, edited by P. Maassen and J. P. Olsen, 99–118. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5971-1_5

- Bovill, C. 2012. “Students and Staff Co-Creating Curricula – A New Trend or an Old Idea We Never Got Around to Implementing?” In Improving Student Learning Through Research and Scholarship: 20 Years of ISL, edited by C. Rust, 96–108. Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development. ISBN: 9781873576922.

- Bovill, C. 2019a. “A Co-Creation of Learning and Teaching Typology: What Kind of Co-Creation are you Planning or Doing?” International Journal for Students As Partners 3 (2): 91–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v3i2.3953.

- Bovill, C. 2019b. “Student–Staff Partnerships in Learning and Teaching: An Overview of Current Practice and Discourse.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 43 (4): 385–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2019.1660628.

- Bovill, C., and C. Bulley. 2011. “A Model of Active Student Participation in Curriculum Design: Exploring Desirability and Possibility.” In Improving Student Learning 18: Global Theories and Local Practices: Institutional, Disciplinary and Cultural Variations, edited by C. Rust, 176–88. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University.

- Bovill, C., A. Cook-Sather, P. Felten, L. Millard, and N. Moore-Cherry. 2016. “Addressing Potential Challenges in Co-Creating Learning and Teaching: Overcoming Resistance, Navigating Institutional Norms and Ensuring Inclusivity in Student–Staff Partnerships.” Higher Education 71 (2): 195–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9896-4.

- Bovill, C., and C. Woolmer. 2019. “How Conceptualisations of Curriculum in Higher Education Influence Student-Staff Co-Creation in and of the Curriculum.” Higher Education 78: 407–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0349-8.

- Buckley, A. 2014. “How Radical is Student Engagement? (And What is It For?).” Student Engagement and Experience Journal 3 (2): 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.7190/seej.v3i2.95.

- Christensen, T., Å Gornitzka, and P. Maassen. 2014. “Global Pressures and National Cultures: A Nordic University Template?” In University Adaptation at Difficult Economic Times, edited by Paola Mattei, 30–52. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cook-Sather, A. 2014. “Student-Faculty Partnership in Explorations of Pedagogical Practice: A Threshold Concept in Academic Development.” International Journal for Academic Development 19 (3): 186–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.805694.

- Cook-Sather, A., C. Bovill, and P. Felten. 2014. Engaging Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching: A Guide for Faculty. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Dunne, E., and R. Zandstra. 2011. Students as Change Agents: New ways of engaging wit learning and teaching in Higher Education. Bristol: ESCalate. Accessed December 11, 2019. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk//14767/7/8242_Redacted.pdf.

- Gravett, K., I. M. Kinchin, and N. E. Winstone. 2019. ““More Than Customers”: Conceptions of Students as Partners Held by Students, Staff, and Institutional Leaders.” Studies in Higher Education. Advance Online Publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1623769.

- Healey, M., A. Flint, and K. Harrington. 2014. Engagement Through Partnership: Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. York: The Higher Education Academy. Accessed December 9, 2019. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/hea/private/resources/engagement_through_partnership_1568036621.pdf.

- Healey, M., A. Flint, and K. Harrington. 2016. “Students as Partners: Reflections on a Conceptual Model.” Teaching & Learning Inquiry 4 (2): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.4.2.3.

- Healey, M., and R. Healey. 2018. “It Depends: Exploring the Context-Dependent Nature of Students as Partners Practices and Policies.” International Journal for Students as Partners 2 (1): 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v2i1.3472.

- Helseth, A., C. Alveberg, P. Ashwin, H. Bråten, C. Duffy, S. Marshall, T. Oftedal, and R. J. Reece. 2019. Developing Educational Excellence in Higher Education: Lessons Learned From the Establishment and Evaluation of the Norwegian Centres for Excellence in Education (SFU) Initiative. Oslo: Nokut.

- Jungblut, J., M. Vukasovic, and B. Stensaker. 2015. “Student Perspectives on Quality in Higher Education.” European Journal of Higher Education 5 (2): 157–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2014.998693.

- Karseth, B., and T. D. Solbrekke. 2016. “Curriculum Trends in European Higher Education: The Pursuit of the Humboldtian University Ideas.” In Higher Education, Stratification, and Workforce Development, edited by S. Slaughter and B. J. Taylor, 215–33. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Klemencic, M. 2011. “Student Representation in European Higher Education Governance: Principles and Practice, Roles and Benefits.” In Handbook on Leadership and Governance in Higher Education. Leadership and Good Governance of HEIs. Structures, Actors and Roles, edited by E. Egron-Polak, J. Kohler, S. Bergan, and L. Purser, 1–26. Berlin: Raabe Publishers.

- Maassen, P., and J. P. Olsen, eds. 2007. University Dynamics and European Integration. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5971-1

- Matthews, K. E., A. Cook-Sather, A. Acai, S. L. Dvorakova, P. Felten, E. Marquis, and L. Mercer-Mapstone. 2019. “Toward Theories of Partnership Praxis: An Analysis of Interpretive Framing in Literature on Students as Partners in Teaching and Learning.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (2): 280–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1530199.

- Matthews, K. E., A. Dwyer, S. Russell, and E. Enright. 2018. “It Is a Complicated Thing: Leaders’ Conceptions of Students as Partners in the Neoliberal University.” Studies in Higher Education, 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1482268.

- McCulloch, A. 2009. “The Student as Co-Producer: Learning From Public Administration About the Student–University Relationship.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (2): 171–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802562857.

- Meek, V. L. 2003. “Introduction.” In The Higher Education Managerial Revolution?, edited by A. Amaral, V. L. Meek, and I. M. Larsen, 1–29. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., and C. Bovill. 2019. “Equity and Diversity in Institutional Approaches to Student–Staff Partnership Schemes in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1620721.

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., S. L. Dvorakova, K. E. Matthews, S. Abbot, B. Cheng, P. Felten, K. Knorr, E. Marquis, R. Shammas, and K. Swaim. 2017. “A Systematic Literature Review of Students as Partners in Higher Education.” International Journal for Students as Partners 1: 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i1.3119.

- Nokut. 2013. Standards and Guidelines for Centres and Criteria for the Assessment of Applications. Accessed December 1 2019. https://www.nokut.no/siteassets/sfu/sfu_standards_guidelines_and_criteria_for_the_assessment_of_applications.pdf.

- Nokut. 2016. Awarding Status as Centre for Excellence in Education (SFU). Accessed December 1 2019. https://www.nokut.no/siteassets/sfu/criteria_sfu_no_en.pdf.

- Nybom, T. 2007. “A Rule-Governed Community of Scholars: The Humboldt Vision in the History of the European University.” In University Dynamics and European Integration, edited by P. Maassen, and J. P. Olsen, 55–80. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5971-1_3

- Olsen, J. P. 2007. “The Institutional Dynamics of the European University.” In University Dynamics and European Integration, edited by P. Maassen, and J. P. Olsen, 25–54. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5971-1_2

- Pritchard, R. 2004. “Humboldtian Values in a Changing World: Staff and Students in German Universities.” Oxford Review of Education 30 (4): 509–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0305498042000303982.

- Stensaker, B., and S. Michelsen. 2011. “Students and the Governance of Higher Education in Norway AU.” Tertiary Education and Management 17 (3): 219–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2011.586047.

- Trowler, P. 2012. “Wicked Issues in Situating Theory in Close-up Research.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (3): 273–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.631515.

- Williamson, M. 2013. Guidance on the Development and Implementation of a Student Partnership Agreement in Universities. Accessed November 8, 2019. https://www.sparqs.ac.uk/upfiles/Student%20Partnership%20Agreement%20Guidance%20-%20final%20version.pdf.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.