ABSTRACT

Despite an increasingly competitive academic market, more and more people are seeking a PhD degree. While significant research focuses on skill attainment during PhD candidature and at PhD exit, we know little about the skills that might be present at PhD entry. We developed a data-driven taxonomy and conducted logistic regressions to analyse selection criteria (listing skills, qualifications, and personal attributes) of 13,562 PhD advertisements posted in 2016–2019 on Euraxess, a European recruitment platform for researchers. We analysed the most prevalent attributes sought for PhD admission, country-based and discipline-specific differences, and changes over time. We find that many of these admission attributes include diverse and transferable skills. Specifically, cognitive, interpersonal skills and personal attributes are trending upwards, and PhD requirements vary significantly by country, discipline and year of posting. We highlight the attributes requested by top 5 countries and top 5 disciplines, and show changes over time. The insights provide guidance for practice, specifically to PhD applicants, early career researchers, and those who support career development. We discuss PhD programmes’ alignment and policy implications for pre-doctoral education, redesign of PhD assessment, and improved training provision for students and supervisors.

Introduction

Globally, a growing number of people undertake a PhD (hereafter PhD), the common purpose of which is to prepare for academic careers (OECD Citation2019). However, we do not sufficiently know what it takes to be admitted into a PhD programme. One group of studies investigates PhD graduateFootnote1 skills for diverse careers as academia is growing increasingly competitive (for examples see Hasgall, Saenen, and Borrell-Damian Citation2019; Mewburn et al. Citation2018; Germain-Alamartine and Moghadam-Saman Citation2020), yet they do not consider what skills might be present at PhD admission. Another body of literature examines PhD students’ characteristics and skill development needs (examples include Sharmini and Spronken-Smith Citation2020; Succi and Canovi Citation2020; Sinche et al. Citation2017), yet they do not discuss the makeup of PhD applicants, specifically what skills are requested at PhD entry and what skills might already be present in PhD candidates.

Our paper identifies what type of skills are requested for PhD admission. Specifically, we investigate what skills, qualities or attributes are requested of PhD applicants. Skill demands essentially reflect what the economy and society need (Burning Glass Technologies Citation2015; Mewburn et al. Citation2018). We present a demand analysis in PhD recruitment which provides a useful baseline for those who are investigating the skills and attributes developed and gained throughout the PhD. This understanding will help pre-doctoral students tailor their applications and skill development, as well as inform supervisors and those supporting PhD applicants or candidates on how to better support the development of early researchers and research professionals.

This study draws on the data source of PhD role advertisements (henceforth referred to as ‘job ads’) to identify what skills and/or other requirements doctoral programmes seek before PhD admission. We analysed the selection criteria of 13,562 PhD ads posted in 2016–2019 on Euraxess, a European recruitment platform listing available opportunities to undertake a PhD. It is common for a university in Europe to advertise open spots in PhD programmes as job postings on a platform such as Euraxess, which lists skill requirements as selection criteria. Therefore, we chose Euraxess as our data collection source. Analysing the ‘skill section’ of each ad revealed that PhD programmes request not only skills but also personal attributes and qualifications, which we collectively label as ‘admission attributes’ henceforth. We developed a taxonomy and extracted attributes present in each advertisement. Analysing big data, we ask what PhD programmes demand of PhD applicants. We address this question by analysing which attributes are requested and the effect of discipline, country and year of posting. We discuss the implications for pre-doctoral and doctoral education, and make several theoretical, methodological and practical contributions. We also discuss how our research contributes and extends the literature on PhD skills and graduate employability.

In the following, we explain how and why we chose a particular skill taxonomy to analyse PhD job selection criteria, outline our methodology, and visualise the findings using various forms of data. We discuss the findings and their implications as well as applicability for practice.

Skill taxonomies

Skills often have multiple synonyms and are interchangeably used with ‘attributes’, ‘competencies’ and ‘qualities’ or categorised differently, e.g. soft vs hard skills. Hence, any study on skill research needs to clarify which skills are referred to and the type of categorisation adopted. To use a common language and increase the practical applicability of our results, we sought a suitable classification of skills in the European context. Three European skill frameworks were considered, namely Vitae’s ‘Researcher Development Framework’ (RDF) (Citation2020), the mindSET framework (Nikol and Lietzmann Citation2019), and the ‘Transferable Skills for Early-Career Researchers’ framework by the European Council of Doctoral Candidates and Junior Researchers (Eurodoc) (Citation2018), hereafter the Eurodoc framework. Our criteria for selecting the most suitable framework were:

(a). a framework needs to be known and widely applied OR comprehensive and incorporating other frameworks that are country- or discipline-specific,

(b). applicable to the European context,

(c). reference broader skills beyond research skills, and preferably

(d). reflect early career researchers’ aspirations

Although developed a decade ago, Vitae’s RDF (Citation2020) provides guidance and reference for researcher development worldwide. It includes categories like professional and career development, professional conduct, and other skills often listed in transferable skill frameworks. The RDF lists four domains (Knowledge and intellectual abilities; Personal effectiveness; Research governance and organisation; and Engagement, influence, and impact), each specifying three skill categories.

However, the skill classification is oriented towards research skills and researcher development across different stages and misses some skills, e.g. digital literacies, that emerge as important in the general labour market. Hence, a framework that spoke to any professional context was required.

The project, ‘Training the mindSET –Improving and Internationalizing Skills Trainings [sic] for Doctoral Candidates’ aims to develop a European Core Curriculum in Transferable Skills for doctoral candidates in Science, Engineering and Technology (SET) Disciplines. The mindSET study (Nikol and Lietzmann Citation2019) developed a skill taxonomy for researchers via a survey with PhD candidates and literature analysis on employer views to understand which transferable skills are needed in the European labour market and which skills need to be developed to enhance PhD graduates’ employability in diverse professional areas. The mindSET taxonomy lists eight areas of transferable skills and, while incorporating multiple frameworks, did not reflect the importance of Communication skills in their own right but rather absorbed them in other categories. Also, generic Work competence and Personal competence clusters did not sufficiently accommodate what has been discussed in previous literature.

The Eurodoc website states: ‘it is an international federation of 28 national organisations of PhD candidates, and more generally of young researchers from 26 countries of the European Union and the Council of Europe’. Like mindSET, the Eurodoc framework also builds on other frameworks, including the RDF, OECD (Citation2019), UniWiND, the European Commission, etc. It lists nine skill categories (see ). In addition, it is a framework informed by several country-specific PhD models, developed as a reference for broad skill development in PhDs across Europe, and advocates for young researchers’ career aspirations. Given that countries approach and structure their PhDs differently, we wanted to account for possible country-specific differences in role requirements (Durette, Fournier, and Lafon Citation2016; Santos, Horta, and Heitor Citation2016). Therefore, the Eurodoc framework provided the most suitable taxonomy ().

Figure 1. Eurodoc framework (adapted from Eurodoc Skill Report Citation2018).

Text mining and job ads

With the advent of text mining and machine learning, research has sought to use these approaches to study job ads and create skill taxonomies. For example, Colombo, Mercorio, and Mezzanzanica (Citation2019) constructed and mapped a skills taxonomy to the ESCO classification taxonomy to identify soft and hard skills listed in job ads. Other examples include work by De Mauro et al. (Citation2018) who used Latent Dirichlet Allocation to determine job families for jobs in Big Data, as core competencies of librarians (Yang et al. Citation2016). More recently Australian researchers used machine learning to analyse job ads in the context of doctoral education (see Pitt and Mewburn Citation2016; Mewburn et al. Citation2018). While the last two studies focus on skills expected at PhD exit, we focus on skill requirements at PhD entry.

While using an existing framework provides a common language and a shared understanding of the study objectives, taking a data-driven approach to skill demand analysis allows insights to emerge that would otherwise be hidden (Sibarani et al. Citation2017). Looking at the data and applying emergent thematic analysis, greater granularity and variety in skills was possible. The application of data-driven taxonomies posits two distinct benefits: the ease of updating and the use of employers’ language, rather than academic (Djumalieva and Sleeman Citation2018). Several existing skill taxonomies rely on expert consultation and can be slow and costly to adapt, whereas a data-driven taxonomy is easily updated, and the same methodology can be used with a new set of job adverts. The text analysis methodology presented in this study is a timely way of capturing information on skill dynamics in different work sectors. Big data, such as job advertisements, can inform quickly; online job adverts, and the skills they list, help us to develop a taxonomy that uses the same ‘skills language’ used by those who employ and supervise PhD candidates, rather than that of external bodies or policymakers.

Methodology

To find out which skills PhD programmes expect at PhD entry we conducted data collection, data analysis, taxonomy creation using a data-derived dictionary, and machine-learning analysis, as follows:

Data collection

Our PhD ads data are gathered from Euraxess, a European platform that lists academic jobs at all levels (from PhD to Professor) from 40 European countries and non-European countries. Jobs ads show different fields: a general job description, benefits, requirements (split in skills/qualifications and specific requirements), university, research field, location, required languages, job status, and starting date. Conceiving the PhD ad as a job and skill requirements as selection criteria, we assume that applicants who already perform at this level are more likely to get the PhD role.

A total of 270,523 ads were downloaded, and three inclusion criteria were applied:

Date published. According to the number of academic job ads available following its launch, Euraxess gained popularity in 2016. Hence, we only included four years, 2016–2019, of data. This criterion reduced our sample to 251,561.

For PhD Students only. Only advertisements that addressed PhD applicants and had the following text in their title were included: PhD, Phd, PhD, doctoral candidate, doctoral student, doctoral fellow, doctoral programme, or doctoral research. This further narrowed our data to 36,787 ads.

Only ads with Skills/Qualifications and Specific Requirements text. In Euraxess, each PhD ad is structured in several sections: we focus on the Skills/Qualification and Specific Requirements sections and merge these to create one unit of analysis per ad. Entries duplicated in both sections were considered as one entry, and ads must list content in at least one of these sections to be considered in our analysis. This resulted in a final data set of 13,562 ads which met all three criteria.

provides a breakdown of 13,562 ads by country, discipline, and year of posting. Sections of the ad used for our analysis are the year of the ad’s posting, research field, location, required languages, and skill requirement text.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

New taxonomy using data-derived dictionary

We took a data-driven approach to taxonomy building. Any existing taxonomy appears flat and void of any ranking or hierarchy if not informed by data. Fitting our data-derived categories into an existing taxonomy meant we could expand and elaborate on the insights that have come before us.

First, random assignment was used to select 200 job ads for closer reading by both authors. The authors tagged each attribute as it emerged in the data. In the same process, we recorded related concepts or ‘synonym-like’ terms for each attribute. We assumed that skills like ‘teamwork’ might likely be referred to as ‘groupwork’ elsewhere but belong to the same category, i.e. collaboration or working with others. Second, our research identified the most suitable skill framework, i.e. Eurodoc framework (as discussed above), following previous studies that have relied on existing skill frameworks to construct a suitable taxonomy (e.g. Colombo, Mercorio, and Mezzanzanica Citation2019; Sibarani et al. Citation2017). Third, we added attributes that were not listed in the Eurodoc categories. This modified the Eurodoc’s nine categories and led to a comprehensive taxonomy of PhD attributes relevant to our sample. Specifically, three new categories were added: Degree and Achievements (degree names, credentials, transcripts, academic records, etc.), Previous Work Experience, and Personal attributes (ambition, enthusiasm, motivation, proactiveness, resilience, etc.). These did not appear in the Eurodoc’s transferable skills categories but were frequently listed in the Skills/Qualifications and Specific Requirements sections of the job ads. As the new categories include qualifications (e. g. Degree and Achievements) and personal attributes, not only skills, we adopted the term ‘admission attributes’ to label our revised categories, inspired by O’Leary’s (Citation2021) work that uses the concept of ‘attributes’ to include skills, personal attributes, and qualifications.

Any taxonomy inevitably presents some overlap in the way they categorise attributes; for example, it can be argued whether creativity fits under Cognitive or Enterprise categories. To avoid as much overlap as possible and keep the categories distinct, the entire taxonomy was verified by three independent and multi-disciplinary peer reviewers and both authors. In several discussions the individual admission attribute categories were sorted until a consensus agreement was reached.

Attributes were excluded from counting if they were used as part of a technical phrase or referred to something unrelated, e.g. ‘Article’ as in ‘Article of Law’, ‘motivation’ as in ‘motivational letter from the candidate’. To do this, we applied the ‘keywords-in-context’ approach, which allowed us to manually check the use of the concept in the ad. As a result, we established 274 individual attributes for our dictionary, 45 of which were instances of attributes (as per examples above) to be disregarded.

Machine-learning analysis

Dictionary-based entity extraction tools extract features in unstructured text into pre-defined categories such as company names, medical codes, or topics (Cai et al. Citation2019; Cook and Jensen Citation2019). Entity extraction tools identify occurrences of pre-defined entities in text (such as job ads). We created a dictionary-based entity extraction tool which searches for occurrences of terms (either as full or partial matches) within ads, returning the categories which are present in the job ad. Such dictionaries have been previously used in job ad research (Anne Kennan et al. Citation2006; Sodhi and Son Citation2010; Deming Citation2015).

The results of our dictionary-based entity extraction tool were then tested for reliability. An independent coder reviewed the initial attributes determined by the authors and tagged a sample of 100 random PhD ads to determine the agreement between our human coder and our entity linker-based results. Krippendorff’s alpha, applicable to nominal data by two or more coders, was used to determine inter-rater reliability (Krippendorff Citation2011). Results of Krippendorff’s alpha ranged from high agreement (alpha ≥ 0.8) to moderate agreement (alpha ≥ 0.67) and poor agreement (alpha < 0.67) (Krippendorff Citation2004). The overall interrater reliability for all categories was high,Footnote2 except for Enterprise and Career Development. Both categories appeared infrequently and hence were removed from our analysis. The final list of ten categories is Research; Digital; Communication; Interpersonal; Cognitive; Teaching and Supervision; Personal attributes; Degrees and Achievements; Previous work experience; and Mobility.

Data analysis

This research aims to identify desirable admission attributes in PhD student recruitment. In other words, what skills, attributes, and qualifications do applicants need to demonstrate when applying for a PhD. To ascertain the likelihood of an attribute category being present in a PhD ad, logistic regressions (LR) were performed for each category as our outcome variable (i.e. category) is either present or not in a PhD ad. The reference category is ‘not present’. The predictor variables are: (1) Year of ad publication, (2) Country of ad and (3) Discipline of ad. A logistic regression analysis was conducted to understand the likelihood of a category being present in an ad, given the year of publication, Discipline and Country. We considered Year as a covariate (continuous variable), while Discipline and Country were considered factors (categorical variables).

Findings

We analyse our data in two parts:

What admission attributes are listed in PhD adverts?

What is the effect of discipline, country, and year of posting?

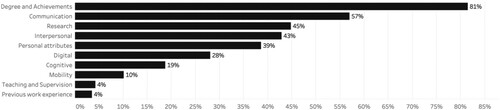

Admission attributes listed in adverts

When examining the data, the Degree and Achievements category was present in 81% of ads. This might be expected, as, e.g. in Europe, a PhD commonly requires a higher education degree, at least at Bachelor but more likely at Master level, although a Bachelor degree in the US and perhaps other countries would suffice. The top three desired categories after Degree and Achievements are Communication, Research, and Interpersonal skills, recorded in close to half of all the PhD postings (). In contrast, prior teaching and work experience are considered least important before doing a PhD. The preponderance of categories varies for disciplines and countries.

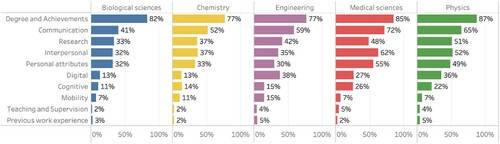

The top five disciplines in our sample are Biological sciences, Physics, Chemistry, Engineering and Medical Sciences (see ). Together, they account for more than half of all PhD postings 2016–2019, reflecting the strong representation of Sciences or STEM disciplines in our data. presents the percentages of ads listing a category per discipline; for instance, the Interpersonal skill category is mentioned in 62% of Medical Science ads; twice as often as in Biological Science ads. Digital skills appear in 38% of all Engineering ads; almost three times as frequently as in Biological Sciences and Chemistry.

Most of the countries represented are in Europe. The top five countries are the Netherlands, Germany, France, Spain, and the UK (see ); together, they supplied more than half of all the PhD posts between 2016 and 2019. presents a breakdown of categories per country. For instance, Mobility – a category that includes intercultural awareness and foreign language skills – is almost eight times more frequent as a requirement in France than in the UK and features highest in Engineering (). The Netherlands places greater focus on Communication, Interpersonal, Personal attributes, and Research, showing up to double the counts or more of these categories than other countries. Digital and Cognitive categories also score much higher in the Netherlands than in other countries. Interestingly, across the top five countries Interpersonal and Personal attributes rank lowest for the UK but highest for the Netherlands.

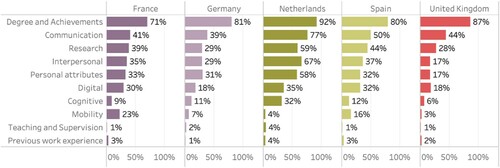

presents a breakdown of categories per year of posting. Further analysis showed an increase in the number of categories listed per ad. On average, in 2016, a PhD ad would mention 2.4 categories, and this steadily increased year on year (3.2 categories in 2017, 3.2 in 2018), leading to 3.6 categories being represented per ad on average in 2019. This suggests that between 2016 and 2019 alone, PhD ads asked for more attributes and more diverse attributes of their applicants. also shows that Communication, Interpersonal, Personal attributes, and Digital categories, along with Cognitive, are trending; hence, gaining importance. The fastest trending categories are Cognitive (doubled in four years), Interpersonal (doubled in four years) and Personal attributes (increase by 90% in four years).

Effect of discipline, country, and year of posting

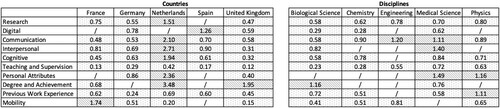

Overall, we find that the occurrence and frequency of attributes differ by country, discipline, and year of ad posting. To determine the likelihood of an attribute appearing in an ad or not, we conducted a logistic regression analysis. Results are presented in . We have selected the top five countries and disciplines that posted the most job ads in 2016–2019 (see ) as a sample to conduct an in-depth analysis. The top five countries are the Netherlands, Germany, France, Spain, and the UK. The top five disciplines are Biological Sciences, Physics, Chemistry, Engineering, and Medical Sciences. Countries and disciplines not in the top five are collectively labelled as Others and form the reference groups for the logistic regression analysis.Footnote3 The odds ratios help show the likelihood of a skill category being present. The higher the odds ratio, the higher the likelihood of the skill category appearing in the ad; conversely, odds ratio between 0 and 1 present lower likelihoods. For example, Netherlands places a strong value on Degree and Achievements (3.48) when compared with other countries, and the UK PhD ads are less likely to request Teaching and Supervision skills (0.12). When comparing disciplines, we find Medical Sciences are 40% more likely to request Interpersonal skills (1.4). On the other hand, Biological Sciences are much less likely to request skills in the same category (0.82).

Table 2. Attribute category by year of posting.

Table 3. Logistic regression results per attribute category.

A visual summary of is presented in , which shows all odds ratios that are significant. Lower likelihood, where the odds ratio is between 0 and 1, is marked as dotted, while higher likelihoods, where odds ratio is above 1, is marked as striped. The symbol ‘/’ is shown for non-significant values. Germany is less likely to mention most skills when compared to ‘Other’ countries. Netherlands, on the other hand, is more likely to request skills such as Degree and Achievements, Interpersonal skills, and Personal attributes in their PhD ads. When comparing Biological Sciences with other disciplines, Biology ads are less likely to request all skills except Degree and Achievement. Comparing Medical Science with other disciplines, the ads are more likely to request Personal Attributes, Interpersonal skills, and Communication.

Discussion

While previous research has examined the various skills and attributes required for post-PhD careers, our PhD data tells us that a number of these attributes are already sought in PhD student recruitment. As Pitt and Mewburn (Citation2016) found that current academic positions expected successful applicants to be nothing short of academic superheroes, we show evidence that expectations are already high at PhD entry. The bar is likely to rise even higher in the researcher career trajectory. We find that during a relatively short period (2016–2019), PhD programmes have increased their expectations for more attributes and more diverse attributes (from 3.2 categories in 2017 to 3.6 in 2019). Indeed, Pitt and Mewburn (Citation2016) also found that academic employers (i.e. universities) look for a wide range of highly developed skills and expertise across academic careers. Further, our data shows that countries and disciplines request different attributes. Understanding these differences informs candidates seeking doctoral training in a particular country or discipline. Based on our findings, Communication, Research, and Interpersonal skills are the top three skills required for PhD admission, following Degree and Achievements. Hence, PhD applicants would benefit from showcasing these skills in their PhD applications before embarking on graduate research training.

Our findings show that many attributes requested in PhD student recruitment are what is commonly referred to as transferable skills (Germain-Alamartine and Moghadam-Saman Citation2020; Sinche et al. Citation2017), skills that are applied across many different professional tasks. The fact that Communication, Interpersonal skills, Personal attributes, and Digital skills, along with Cognitive skills, are trending in our data (), indicates that it takes transferable skills to do a PhD. Our research sides with previous research (OECD Citation2017; Deming Citation2015; Succi and Canovi Citation2020) that projected that two types of skills would be particularly important in the future: soft and digital skills. PhD candidates are expected to network, collaborate, co-publish, pitch, and communicate their research to diverse audiences and have advanced technical and digital competencies. The fastest trending categories of Interpersonal skills (including teamwork, negotiation, networking, conflict resolution, etc.) and Personal attributes (including resilience, enthusiasm, motivation, etc.) in PhD ads suggest that doing a PhD requires such qualities. Interpersonal skills and Personal attributes would be particularly useful in doctoral programmes that are more collaborative and interdisciplinary (Blessinger Citation2016; Borrell-Damian, Morais, and Smith Citation2015). Overall, PhD programmes would do well in communicating how the attributes required for PhD admission will be applied and further developed during the PhD.

Our data also shows that Research experience is required in 45% of our sample and increasing by 13% per year (). This points to heightened demands placed on research training. PhD applicants need to arrive already equipped with skills like Communication and Interpersonal skills, as PhD programmes are tightly regulated and structured to support timely completion and boost research outputs (Humphrey, Marshall, and Leonardo Citation2012; Sharmini and Spronken-Smith Citation2020; Bosanquet, Mantai, and Fredericks Citation2020).

Further, our research insights inform the PhD design literature by adding a better understanding of what is expected pre-PhD. Albeit its primary purpose of preparing for academic careers, the PhD needs to develop students for diverse careers as the academic employment market is increasingly competitive. Taking a curriculum development perspective, Sharmini and Spronken-Smith (Citation2020) argue that the current PhD format is not aligned with the need to adequately prepare PhD students for academic and non-academic careers. Examining the multiple skill frameworks earlier (i.e. Vitae’s RDF, mindSET, Eurodoc), it is undeniable that PhD students are expected to do more than ‘just’ advancing research skills and generating original knowledge. Increasingly, PhD students need to demonstrate superior communication, networking and leadership skills (Borrell-Damian, Morais, and Smith Citation2015). These skills are not commonly reflected in PhD programme descriptions or outcomes but are visible in the PhD selection criteria in our data. Our research supports Sharmini and Spronken-Smith’s argument (Citation2020) that the PhD needs to be revised to reflect and provide evidence for the multifaceted learning and development that occurs in the PhD, which extends beyond the student’s particular discipline, including leadership training, outreach activities, and interdisciplinary projects (Sharmini and Spronken-Smith Citation2020; Blessinger Citation2016). These expectations explain the diversity of skills found in our data. Assessment and diverse evidence, other than the thesis, would better reflect the breadth of knowledge and skills possessed pre-PhD and gained during PhD, and potentially be easier for diverse employers to appreciate. Alternative assessments might include creative literary outputs, multidisciplinary collaborative team projects, implemented initiatives and impact, innovations, collaborations with industry, business plans for start-up companies, strategic plans, policy documents, etc. Assessment could also focus on the skill gains from pre-PhD to post-PhD.

Finally, our research informs PhD graduate employability research as it provides the baseline of the attributes desired at PhD entry. Our data shows that successful PhD applicants may possess a breadth of attributes transferable to other careers already. Hence, we should be able to expect PhD graduates to be able to follow diverse careers (Germain-Alamartine and Moghadam-Saman Citation2020). However, to further one’s employability and become ‘more well-rounded researchers, practitioners and leaders’ (Blessinger Citation2016) is so far left up to the doctoral candidate’s initiative and ability to firstly, locate formal or informal development opportunities and secondly, accommodate these in already busy PhD schedules. We recommend embedding an explicit career development focus in PhD programmes and promote candidates’ work-readiness building on and furthering the attributes that we found might already be present at PhD admission.

Limitations

Developing static definitions for skill categories is an ambitious task, and the skill categories are likely to evolve. Skills are notoriously difficult to distinguish (Djumalieva and Sleeman Citation2018), which is why some countries and disciplines do not have an established skill framework. Others before us have acknowledged there is no single ‘right way’ to group skills (Djumalieva and Sleeman Citation2018). Nevertheless, the dictionary developed and the taxonomy used in this paper provide a shared understanding of the concepts and types of skills examined in this study. We also acknowledge that we cannot assume that all work, let alone PhD roles, are advertised online or if and how the roles are filled (e.g. whether requested skills and attributes are found or whether successful candidates accepted the role). Further, we do not claim that all PhDs require the identified admission attributes to complete or succeed in a PhD, however, as our data shows PhD programmes increasingly request such attributes. We wish to reiterate that our analysis concerns pre-PhD attributes only; we do not measure or compare these against post-PhD employability attributes, nor do we measure whether selected candidates possess all attributes requested. This warrants further research and a systematic comparison of attributes at PhD recruitment, admission, and graduation.

Study implications and applicability

Our research makes several contributions. From a theoretical point of view, we place research training in the context of employability development and use the pre-PhD application stage as the first point in this development journey where we measure the baseline of desirable attributes. Our paper revealed that diverse skills and attributes are requested before PhD entry, many of which are commonly expected at PhD exit.

On a methodological level, we empirically validated the Eurodoc skill framework and expanded it by generating our data-derived dictionary. We developed a dictionary of attributes based on a big data set that can be applied to any academic job ad data in the future and provide useful data comparisons and changes over time. Further empirical research might use our framework to assess and measure the baseline of admission attributes in PhD students to determine individual development needs that the institutions can provide.

This study has significant relevance for practice. Our insights benefit any student on a pathway to the PhD, PhD applicants themselves, early career researchers, and those supporting and educating them. We provide more transparency and understanding of admission attributes expected of PhD applicants in different disciplines and countries to make informed decisions, adopt the appropriate language of employment requirements, plan their career development accordingly, and improve their competitiveness. Our results point to differences and nuances in skill demands across disciplines and countries that need to be considered in pre-doctoral education and its policies.

In relation to policy, we recommend that PhD programme design and descriptions emphasise the need to have diverse and transferable attributes pre-PhD. These are likely to lead to success in doing PhD research as well as navigating common PhD challenges. PhD pathway programmes and pre-PhD education more broadly are well-advised to embed skill training and development of the top attributes we identified. Authentic research experiences (e.g. summer or winter scholarships, internships, research for coursework, witnessing educators being engaged in research) offer ideal opportunities to prepare for a PhD (Brew and Mantai Citation2020; Hajdarpasic, Brew, and Popenici Citation2015). During PhD candidature, we can assume that PhD candidates will build on and further enhance their admission attributes but might need help in developing those that were not present pre-PhD. In this case, career development training for students needs to be embedded in PhD programmes, and appropriate training for supervisors might be required.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of the Senior Consultant in Statistics, Jim Matthews, from the Sydney Informatics Hub, a Core Research Facility of the University of Sydney. We are very grateful to the reviewers for their constructive and helpful feedback on the earlier draft of this paper. We also wish to thank EURAXESS - Researchers in Motion, a pan-European initiative by the European Commission, for the permission to analyse EURAXESS job data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The term ‘graduate’ or ‘PhD graduate’ in this paper refers to those who completed their PhD, while ‘student’ and ‘candidate’ both refer to those who have not yet been awarded the PhD.

2 Admission attribute categories and their Kippendorff's alpha: Research – 0.80, Teaching and Supervision: 0.89, Cognitive: 0.90, Interpersonal: 0.86, Digital: 0.93, Communication: 0.88, Mobility: 0.87, Personal attributes: 0.80, Degree and Achievements: 0.86, Previous work experience: 0.89.

3 Detailed data and data analysis on specific disciplines and countries can be obtained from the authors upon request.

References

- Anne Kennan, M., Cole, F., Willard, P., Wilson, C., and Marion, L. 2006. “Changing Workplace Demands: What Job Ads Tell Us.” Aslib Proceedings 58 (3) 179–196. doi:10.1108/00012530610677228.

- Blessinger, Patrick. 2016. “The Shifting Landscape of Doctoral Education,” October 2. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story = 20161004145514435.

- Borrell-Damian, Lidia, Rita Morais, and John H Smith. 2015. “Collaborative Doctoral Education in Europe: Research Partnerships and Employability for Researchers.” European University Association. https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/collaborative%20doctoral%20education%20in%20europe%20report%20on%20doc-careers%20ii%20project%20.pdf.

- Bosanquet, Agnes, Lilia Mantai, and Vanessa Fredericks. 2020. “Deferred Time in the Neoliberal University: Experiences of Doctoral Candidates and Early Career Academics.” Teaching in Higher Education 25 (6): 736–49.

- Brew, Angela, and Lilia Mantai. 2020. “Turning a Dream Into Reality: Building Undergraduate Research Capacity Across Australasia.” In International Perspectives on Undergraduate Research, edited by Nancy H. Hensel and Patrick Blessinger, 39–56. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-53559-9_3

- Burning Glass Technologies. 2015. “The Human Factor.” https://www.burning-glass.com/wp-content/uploads/Human_Factor_Baseline_Skills_FINAL.pdf.

- Cai, Cynthia W., Martina K. Linnenluecke, Mauricio Marrone, and Abhay K. Singh. 2019. “Machine Learning and Expert Judgement: Analyzing Emerging Topics in Accounting and Finance Research in the Asia–Pacific.” Abacus 55 (4): 709–33.

- Colombo, Emilio, Fabio Mercorio, and Mario Mezzanzanica. 2019. “AI Meets Labor Market: Exploring the Link Between Automation and Skills.” Information Economics and Policy 47: 27–37.

- Cook, Helen V., and Lars Juhl Jensen. 2019. “A Guide to Dictionary-Based Text Mining.” Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, NJ) 1939: 73–89.

- De Mauro, Andrea, Marco Greco, Michele Grimaldi, and Paavo Ritala. 2018. “Human Resources for Big Data Professions: A Systematic Classification of Job Roles and Required Skill Sets.” Information Processing & Management 54 (5): 807–17.

- Deming, David J. 2015. “The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market.” Working Paper 21473. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w21473.

- Djumalieva, Jyldyz, and Cath Sleeman. 2018. “An Open and Data-Driven Taxonomy of Skills Extracted from Online Job Adverts.” In Developing Skills in a Changing World of Work, edited by Christa Larsen, Sigrid Rand, Alfons Schmid, and Andrew Dean, 425–54. Rainer Hampp Verlag. doi:10.5771/9783957103154-425.

- Durette, Barthélémy, Marina Fournier, and Matthieu Lafon. 2016. “The Core Competencies of PhDs.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (8): 1355–70. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.968540.

- Eurodoc Doctoral Training Working Group. 2018. Identifying Transferable Skills and Competences to Enhance Early Career Researchers Employability and Competitiveness. Brussels: The European Council of Doctoral Candidates and Junior Researchers. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.1299178.

- Germain-Alamartine, Eloïse, and Saeed Moghadam-Saman. 2020. “Aligning Doctoral Education with Local Industrial Employers’ Needs: A Comparative Case Study.” European Planning Studies 28 (2): 234–54. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1637401.

- Hajdarpasic, Ademir, Angela Brew, and Stefan Popenici. 2015. “The Contribution of Academics’ Engagement in Research to Undergraduate Education.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (4): 644–57. doi:10.1080/03075079.2013.842215.

- Hasgall, Alexander, Bregt Saenen, and Lidia Borrell-Damian. 2019. “Doctoral Education in Europe Today: Approaches and Institutional Structures.” European University Association. https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/online%20eua%20cde%20survey%2016.01.2019.pdf.

- Humphrey, Robin, Neill Marshall, and Laura Leonardo. 2012. “The Impact of Research Training and Research Codes of Practice on Submission of Doctoral Degrees: An Exploratory Cohort Study.” Higher Education Quarterly 66 (1): 47–64.

- Kennan, Mary Anne, Fletcher Cole, Patricia Willard, Concepción Wilson, and Linda Marion. 2006. “Changing Workplace Demands: What Job Ads Tell Us.” In Aslib Proceedings. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2011. “Computing Krippendorff’s Alpha-Reliability.” https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/43.

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2004. “Reliability in Content Analysis: Some Common Misconceptions and Recommendations.” Human Communication Research 30 (3): 411–33.

- Mewburn, Inger, Will J. Grant, Hanna Suominen, and Stephanie Kizimchuk. 2018. “A Machine Learning Analysis of the Non-Academic Employment Opportunities for Ph. D. Graduates in Australia.” Higher Education Policy 33 (4): 799–813.

- Nikol, Petra, and Anja Lietzmann. 2019. “MindSET European Transferable Skills Training Demands Survey –Analysis Report.” https://www.cesaer.org/content/6-representation/mindset/20190818-mindset-european-transferable-skills-training-demands-survey-analysis-report.pdf.

- OECD. 2017. “Future Of Work And Skills” Paper presented at the 2nd Meeting of the G20 Employment Working Group, Germany. https://www.oecd.org/els/emp/wcms_556984.pdf.

- OECD. 2019. “What Are the Characteristics and Outcomes of Doctoral Graduates? | Education at a Glance 2019 : OECD Indicators | OECD Library.” https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/8389c70e-en/index.html?itemId = /content/component/8389c70e-en.

- O’Leary, Simon. 2021. “Gender and Management Implications from Clearer Signposting of Employability Attributes Developed Across Graduate Disciplines.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (3): 437–56. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1640669.

- Pitt, Rachael, and Inger Mewburn. 2016. “Academic Superheroes? A Critical Analysis of Academic Job Descriptions.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 38 (1): 88–101.

- Santos, João M., Hugo Horta, and Manuel Heitor. 2016. “Too Many PhDs? An Invalid Argument for Countries Developing Their Scientific and Academic Systems: The Case of Portugal.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 113: 352–62.

- Sharmini, Sharon, and Rachel Spronken-Smith. 2020. “The PhD – Is It out of Alignment?” Higher Education Research & Development 39 (4): 821–33. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1693514.

- Sibarani, Elisa Margareth, Simon Scerri, Camilo Morales, Sören Auer, and Diego Collarana. 2017. “Ontology-Guided Job Market Demand Analysis: A Cross-Sectional Study for the Data Science Field.” In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Semantic Systems, 25–32. Semantics2017, Amsterdam: Association for Computing Machinery. doi:10.1145/3132218.3132228.

- Sinche, Melanie, Rebekah L. Layton, Patrick D. Brandt, Anna B. O’Connell, Joshua D. Hall, Ashalla M. Freeman, Jessica R. Harrell, Jeanette Gowen Cook, and Patrick J. Brennwald. 2017. “An Evidence-Based Evaluation of Transferrable Skills and Job Satisfaction for Science PhDs.” PLOS ONE 12 (9): e0185023. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185023.

- Sodhi, ManMohan S., and Byung-Gak Son. 2010. “Content Analysis of OR Job Advertisements to Infer Required Skills.” Journal of the Operational Research Society 61 (9): 1315–27.

- Succi, Chiara, and Magali Canovi. 2020. “Soft Skills to Enhance Graduate Employability: Comparing Students and Employers’ Perceptions.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (9): 1834–1847. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1585420.

- Vitae. 2020. “About the Vitae Researcher Development Framework — Vitae Website.” August 19. https://www.vitae.ac.uk/researchers-professional-development/about-the-vitae-researcher-development-framework.

- Yang, Qinghong, Xingzhi Zhang, Xiaoping Du, Arlene Bielefield, and Yan Quan Liu. 2016. “Current Market Demand for Core Competencies of Librarianship—A Text Mining Study of American Library Association’s Advertisements from 2009 Through 2014.” Applied Sciences 6 (2): 48.