ABSTRACT

In defining successful collaborative international projects within the theory of change or logic model, focus is often on ‘outcome’ and ‘impact’. Less empirical information is available regarding the ‘input’ and ‘activities’ aspects of this model. To address this knowledge gap and to offer insight into pivotal elements for management, this study focused on the lessons learned from the development and management of the international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary collaboration Caring Society (CASO) project. A needs analysis among project members was performed using a cross-sectional questionnaire with 31 multiple-choice and 10 open-ended questions. The combined quantitative and qualitative findings resulted in seven key elements being identified: information/communication, personal capacity building, finance, organization, time, facility, and quality. These elements are related in that the elements information/communication and organization play a central role with the element time mediating this role. Other elements such as finance, facility, and quality are on a secondary level of importance while personal capacity building is a meaningful outcome. The lessons learned from managing CASO as an international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary project are that: (1) managers should focus on how information is structured and disseminated as this increases the quality of organizational processes, (2) open dialogue through hybrid communication methods foster better levels of accountability and ownership of tasks, also leading to personal capacity development, enhancing a sense of belonging, and development of intercultural and interdisciplinary competencies, and (3) the role of finances, time and resources cannot be ignored as these impact quality, management, and organization of international projects.

Introduction

In recent years, health service research and education have attracted more attention, especially when professionals from Higher Education Institutions (HEI), in developed and developing countries, are involved in international collaboration, which fosters intercultural and interdisciplinary activities (i.e. international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary collaborative projects, hereafter abbreviated as 3ICP) (Arakawa and Anderson Citation2020; Bell and Cuypers Citation2010; Van Vught, Van der Wende, and Westerheijden Citation2002). The purpose of these collaborations is to create an impact on several aspects (Bell and Cuypers Citation2010; Khor and Lu Citation2016), regarding an exchange of views and knowledge in the world of work and education. However, within this type of knowledge exchange, differences in culture, academic disciplines, communication, pedagogical methods, and interpersonal relations exist (Evans et al. Citation2020).

To date, research in this area has focussed mainly on ‘outcomes’ and ‘impact’ (Almansour Citation2015; De Wit Citation2009; Rørstad, Aksnes, and Piro Citation2021). These, however, are at the end of a chain of events, for a successful project, according to the Logical Framework approach and Theory of Change (Connell and Kubisch Citation1998; Ringhofer and Kohlweg Citation2019; Rogers Citation2014) as described in the Erasmus+ impact tool (Erasmus+ Citation2021). The Theory of Change involves five steps: input, activities, output, outcomes, and impact. This current study aimed to gain insight into the first two steps of the model being ‘input’, and ‘activities’, instead of the last steps: ‘output’, ‘outcomes’, and ‘impact’. This might lead to bridging the differences between disciplines and countries, as mentioned by Evans et al. (Citation2020), and lead to successful sustainable international, interdisciplinary, and intercultural collaboration.

These international collaborations benefit from international funding programmes, such as the European Erasmus+ programme (e.g. Erasmus+ Citation2017 and Erasmus Student Network Citation2020). These funding programmes provide a context for international research, educational development, sharing of knowledge, mobility, collaboration, and development of international and intercultural competencies, thus increasing capacity building (European Commission Citation2019). In this, adequate management has been observed to play an important role in facilitating successful collaboration, in which participants could excel (Beekhoven, Hoogeveen, and Maarse Citation2018; De Korte, Van den Broek, and Ramakers Citation2018).

Universities forming consortiums with organizations and professional associations, play a key role in the promotion and management of international collaboration. In addition, timely and adequate evaluation of the consortiums, as well as its partners, are required. However, identifying obstacles, such as the importance of preparation and project organization, support from the relevant departments within each home institution, selection of participants, using various available project management tools and guidelines to the management of international projects in the field of higher education, appear to be absent. Therefore, these elements of the first steps of the theory of change, require further scrutiny.

In this paper, we offer insight into the dimensions of successful collaboration, as it relates to the basic elements of project management: Organization, Quality, Information/communication, Time, and Facilities; involving a partnership of six universities, named the Caring Society 3.0 consortium, abbreviated as CASO (Caring Society Citation2016), which was funded by the Erasmus+ capacity building in higher education programme (Erasmus+ Grant number: 573518-EPP-1-2016-1-NL-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP).

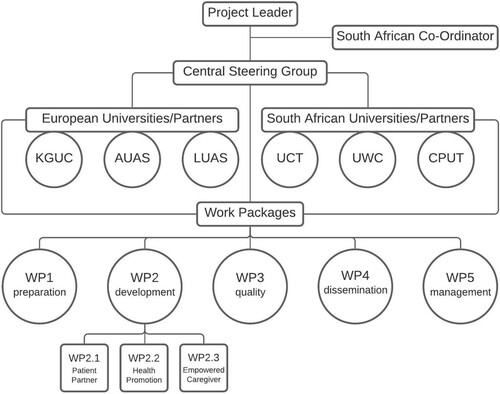

This consortium comprised researchers and lecturers from six universities from the global North and South, namely: Avans University of Applied Sciences (AUAS); Lahti University of Applied Sciences (LUAS); Karel De Grote University College (KGUC); University of the Western Cape (UWC); Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT, including the Western Cape College of Nursing [WCCN]); and University of Cape Town (UCT). The project was managed by a central steering group, with representatives of each university, and led by AUAS. The project leader was assisted by a South African counterpart, representing all South African partners, while university representatives were responsible for their own university teams. As illustrated in , the project comprised five work packages (WP), with WP2-Development divided into three operational sub-projects, each with its own project leader.

Converting a successful grant application into a successful project requires investing in people, managing group dynamics, and a joint understanding of responsibilities and objectives. These were detailed in the application, inherent to the grant programme criteria, moving away from a research mind-set, to a capacity building mind-set. In addition to intercultural and interprofessional communication barriers, the historical hierarchical management style from South Africa, versus the more democratic European University management approach, created communicational barriers for the consortium. It was important to consider these aspects, as well as how they affected the overall project management and leadership. It was important for the steering group to exercise flexibility and foster support, across the different levels of the consortium, as well as ensure participation and joint ownership for the duration of the project. Based on these experiences, it became imperative to reflect on, and monitor the process of working together in a complex international project, in light of jointly learning to collaborate internationally, interdisciplinarily, and interculturally.

Over the past decades, international collaboration has seen an increase due to the importance related to internationalization, research outputs, and other impact dimensions as it relates to success indicators for such projects (Rørstad, Aksnes, and Piro Citation2021). As part of UNESCO’s Global Education 2030 agenda, international collaboration across disciplines has been emphasized since the complex societal challenges require this interdisciplinary collaboration instead of the more conventional approach of working in isolated disciplines (Parr et al., Citation2022). To this end, in addition to effective management of these projects, it is important to assemble project teams that have the requisite soft skills in order for successful collaboration to be achieved (Fittipaldi Citation2020). This renders interpersonal collaboration and teamwork as core competencies required for success. This paper offers insight not only into the management of intercultural and interdisciplinary collaboration in an international health and well-being educational capacity-building project, but also the importance of the aforementioned soft skills in interpersonal communication and collaboration from the onset, development and management of these types of projects.

Aim of the study

As stated above, abundant evidence on ‘outcome’ and ‘impact’ exists, however, there is a lack of empirical information, regarding the management of collaborative international projects. To reduce this knowledge gap, the central question for our study was: ‘What lessons could be learned from the development and management of the international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary collaboration project, CASO, in the field of health and well-being for higher education?’. In this article, we offer insight into pivotal elements for the management of this type of project.

Materials and methods

A needs analysis was conducted, using a quasi-experimental mix-methods design (Mark, (Citation2015), to analyse the processes of the CASO project. A cross-sectional questionnaire was developed, with 31 multiple choice (MC) items, to generate quantitative data, and 10 open-ended questions (OQ) to elaborate on the MC-items and generate qualitative data. The items were divided into one category for Personal Capacity Building (7 MC and 8 OQ); six organizational categories for Finance (3 MC); Organization (3 MC); Time (3 MC); Information/ communication (7 MC); Quality (4 MC); Facilities (2 MC); and a more general category, with 2 MC, and 2 OQ questions. For the MC-items, a 5-point Likert Scale was used, with scores ranging from ‘strongly agree’ (1) to ‘strongly disagree’ (5). The questionnaire was checked by team members of WP1 for comprehensibility and consistency and distributed to all the project members (N = 36) via the Google Forms platform.

The quantitative data were analysed using the SPSS statistical programme v25 (Chicago, Illinois), in which 2 items had to be recoded. Homogeneity was tested on all categories, those with an acceptable homogeneity (>0.6) were subjected to further analysis. A multiple single stepwise regression analysis, as well as an ANOVA procedure were performed on all the categories, to check for (inter)relationships between the categories. In addition, Pearson’s Correlation between the categories and all the items was performed, to provide more detailed insight into possible relationships between the categories. Possible differences between project-specific work packages were analysed, using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test.

The data from the responses to the open-ended questions were qualitatively analysed, using Thematic Analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), with a slight adaptation, as the data did not need to be transcribed, rendering the first 2 steps obsolete. The data were read firstly, and codes were generated, using an open coding paradigm. Subsequently, the codes were clustered, and finally, these clusters were categorized. To reduce researcher bias, these steps were performed by two researchers, independently. Subsequently, both researchers compared codes, clusters, and categories, ultimately achieving consensus on the final clusters and categories.

Results

General results of the questionnaire

The questionnaire achieved a response rate of 78% (28/36), and the data could be interpreted as representative for all staff members of the CASO-project. Concerning the reliability of the items that constituted a category, homogeneity appeared to be good, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.70 to 0.81 (). No differences were observed between staff members, assigned to different WPs. Ultimately, the results represented the CASO-population, thereby conferring good reliability and validity on the questionnaire, with an overall Cronbach’s α of 0.72.

Table 1. Homogeneity of variances.

Quantitative analysis

On average, the project partners were positive on all scores, as the median scores were in the lower range, indicating more ‘agree’ – ‘strongly agree’ on the positive formulated statements (). However, on categories Time, Quality, and to a lesser degree, Information/communication scores were more ambivalent towards ‘agree/disagree’.

Correlations between project aspects

The Pearson correlation () revealed that Organizational aspects were highly correlated to Information/communication aspects (R = .781; p = .000), Quality aspects (R = .707; p = .000), and Facilities aspects (R = .577; p = .002). In addition, a high correlation was observed between Quality aspects and Information/communication aspects (R = .735; p = .000) on the one hand, and Facilities aspects (R = .601; p = .000) on the other. To a lesser extent, but still significant, Quality aspects were correlated to Personal Capacity Building aspects (R = .407, p = .016). Finally, Information/communication aspects were highly correlated to Facilities aspects (R = .576; p = .002). Aspects of Time and Finance displayed no correlations with the other aspects.

Table 2. Pearson correlation between categories.

When analysing correlations in more detail, the items of three aspects were prominent.

Information/communication aspects

The Organizational items of ‘It is clear to me who to turn to in case of problems’ and ‘There were clear managerial procedures and line of command’ were significantly (p < .001) highly positively correlated with the Information/communication items of ‘Able to find all the information needed’ (R = .623 and .603), ‘When not able to attend meeting I was informed sufficiently and adequately by notes of the meeting’ (R = .506 and .603), ‘Clear to me what to do and when to do it’ (R = .596 and .502), ‘Meetings were announced in time to participate’ (R = .562 and .510), and ‘Messages from project leaders were easy to follow’ (R = .490 and .545). The item, ‘It is clear to me who to turn to in case of problems’, was also highly positively correlated to the Information/ communication item, ‘I felt free to say what I wanted to say and when to say it’ (R = .592). Additionally, the item, ‘At ease in the way of approach by management and project leader(s)’, was significantly positively correlated with the Information/communication items of ‘Messages from project leaders were easy to follow’ (R = .543), and ‘Meetings were announced in time to participate’ (R = .422). This indicates that clearer managerial and organizational procedures increase, with improved communication clarity.

| (2) | Quality aspects | ||||

Quality aspects correlated with three other aspects. Firstly, the Quality item, ‘Working procedures and working standards were clear to me’, correlated highly positively with the Personal Capacity Building item, ‘Able to contribute with my knowledge/expertise to CASO’ (R = .605, p < .000). In addition, the Quality item, ‘meetings were organized with a clear agenda’, correlated positively with the Personal Capacity Building item, ‘CASO adds to my capacities, skills and competences’ (R = .485, p = .004).

Secondly, the Quality items of ‘Working procedures and working standards were clear to me’ and ‘meetings were organized with a clear agenda’ both correlated positively (p < .01) with the Organizational items of ‘It is clear to me who to turn to in case of problems’ (R = .450 and R = .605) and ‘There were clear managerial procedures and line of command’ (R = .574 and R = .767).

Thirdly, and most significantly, the Quality items were correlated to Information/communication items, especially the item, meetings were organized with a clear agenda, which correlated significantly highly positively (p < .01) with the Information/communication items of 'When not able to attend meetings I was informed sufficiently and adequately by notes of the meeting' (R = .400), 'Messages from project leaders were easy to follow' (R = .441), 'Clear to me what to do and when to do it' (R = .411), 'Able to find all the information needed' (R = .413), and 'Meetings were announced in time to participate' (R = .466). The Quality item, 'Working procedures and working standards were clear to me', was highly positively correlated (p < .001) to the Information/communication items of 'When not able to attend meetings I was informed sufficiently and adequately by notes of the meeting' (R = .540), 'Messages from project leaders were easy to follow' (R = .581), and 'Able to find all the information needed' (R = .455). The Quality item, 'Gant chart was helpful keeping on track', correlates significantly positively (P < .01) to the Information/communication items of 'Clear to me what to do and when to do it' (R = .580), and 'Able to find all the information needed' (R = .579). Finally, the Quality item, 'Working procedures and standards were sufficiently communicated to me', was significantly positively correlated (p< .01) to the Information/communication item, 'When not able to attend meetings I was informed sufficiently and adequately by notes of the meeting' (R = .437).

| (3) | Facility aspects | ||||

The Facilities item, ‘I had sufficient working space’, correlated significantly positively (P < .01) with the Organizational items of ‘Clear managerial procedures and line of command’ (R = .612), ‘Clear who to turn to in case of problems or questions’ (R = .542), and ‘At ease in way of approach by management and project leader(s)’ (R = .512). Additionally, it correlated significantly positively (P< .001) with Information/communication items of ‘I was able to find all the information needed’ (R = .576), ‘Messages from project leaders were easy to follow’ (R = .509), ‘Clear to me what to do and when to do it’ (R = .446), and ‘Meetings were announced in time to participate’ (R = .469). Regarding the correlation to Information/communication aspects, the Facilities item, ‘Had sufficient access to ICT infrastructure’ correlated significantly (p < .01) with the Information/communication items of ‘Messages from project leaders were easy to follow’ (R = .440), and ‘I was able to find all the information needed’ (R = .480). Finally, it correlated positively (p < .001) with the Quality items of ‘Meetings were organized with a clear agenda’ (R = .603), and ‘Working procedures and working standards were clear to me’ (R = .414). Overall, this would suggest that experienced workspace and facilities, including sufficient ICT, increases with improved managerial procedures, clarity in communication, project quality, and finance.

Regression analysis and modelling relations between project aspects

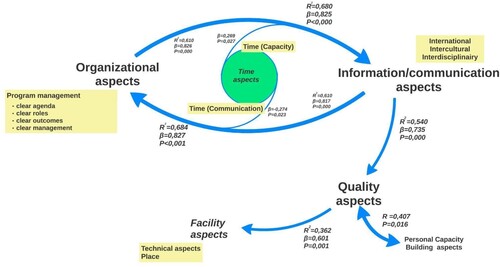

Multiple single stepwise regression analysis was performed to gain more insight into the way the project aspects were correlated. This regression analysis revealed that the aspects were related in a complex, non-linear fashion. Additionally, in contrast to correlation analysis, in regression analysis, the Time aspects appeared to be a significant factor, as the Organization aspects were best explained through the two-step model of the Information/communication aspects and Time aspects (F = 27.03; R2 = .684; β = 0.827; p < .001). In this model, the Information/communication aspects accounted for 61% of variance (R2 = 0.610; β = .817; p = .000), with the Time aspects accounting for an extra 7% of variance. The reported Time aspects were negatively associated with the Organizational aspects (β = −.274; p = .023), as most project members were positive about Organization, but simultaneously, negative about the Time they were able to invest in the project. The Information/communication aspects, in turn, were best explained through the two-step model of the Organizational aspects and Time aspects (F = 26.57; R2 = .680; β = .825; p < .000), in which the Organizational aspects accounted for 61% (R2 = .610; β = .826; p = .000) of variance, with the Time aspects accounting for extra 7% of variance (β = .269; p = .027). Both aspects were positively associated, as the project members reported better Information/communication, by being positive about Organization, as well as the time they were able to invest in the project. In addition, the Information/communication aspects accounted for 54% of variance of the Quality aspects (F = 30.55; R2 = .540; β = .735; p = .000), where the Quality aspects appeared to account for 36% of variance of Facilities aspects (F = 14.74; R2 = .362; β = .601; p = .001). Where the aspects of Quality and Personal Capacity Building were correlated, there were no significant regression coefficients explaining the variance between aspects.

Qualitative analysis

To provide additional meaning to the quantitative data, the responses to the open-ended questions in the questionnaire were qualitatively analysed as described in the methods section and using the method thematic analysis of Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Answers to the OQ’s were analysed separately by two researchers using open coding. These codes were clustered and finally categorized. Researchers compared and discussed their separate analysis to reach consensus. This, resulted in 182 quotes that were coded and grouped into 15 clusters, which subsequently, were assigned to the 5 major aspects, namely: Personal Capacity Building; Organization; Time; Information/ Communication; and Quality ().

Table 3. Distribution of clusters from qualitative analysis over aspects from quantitative analysis.

The aspect of Personal Capacity Building contained quotes that resembled personal growth due to the project, or the members felt enabled to perform at their best during the project. The project members used quotes to illustrate their involvement and the way they felt accountable/responsible for the CASO-project. Other quotes more resembled the way they had learned from other project members, and felt enabled to teach students, or use their traits during the project.

The aspect of Organization was the result of the clusters of Programme management, Finances, and Technical aspects, since all these clusters stemmed from quotes that were associated with the more abstract process of the CASO-project. The cluster, Programme management, resulted from quotes that illustrated core principles, such as Clear agenda, Clear roles, Clear outcomes, and Clear management, as some project members stated that the outcome of the project was attenuated by management. Regarding the tasks of work packages, outcome of staff meetings, and long- and short-term planning, everyone was unclear about their specific contribution to the project. The cluster, Technical aspects, contained quotes referring to ICT-problems during staff meetings, as well as the instability of, and problems during skype sessions, in the time between staff meetings. Finally, quotes about costs of travel, and stay during staff meetings, or availability of equipment, resulted in the cluster, Finances.

The aspect of Time contained quotes that could be translated into two meanings of time. Firstly, there were quotes that referred to the time it took to work on the projects and products, such as MOOC and documents, and hence, more instrumental in a context of capacity. Secondly, other quotes referred, more specifically, to the time for communication and tuning, with other project members, working in the same work package, and rather had an emphasis on space or time of communication.

The aspect of Information/Communication was the most elaborate, since many quotes were related to a form of communication. The analysis resulted in distinguishing between quotes referring to communication between project members, using diverse languages (international), from diverse cultural backgrounds (intercultural), or with diverse professional backgrounds (interdisciplinary). Although some overlap exists between international and intercultural communication, quotes could not be assigned to both, and therefore, a differentiation in these clusters was required. Generally, all three forms of communication should be addressed extensively at the beginning of a project such as CASO. As was stated in some of the quotes, meeting face-to-face was the most optimal form of communication, interaction and engagement.

Overall summary of the needs analysis

All clusters in the qualitative results could be assigned to all aspects of the quantitative results, with some quotes overlapping slightly between the aspects. Quotes related to Quality aspects, especially, overlapped with those of Organizational aspects. Although it could be argued that some clusters could be assigned to multiple aspects, the presented distribution seemed closest to the meaning of both the aspects and clusters.

From the combined results of both the quantitative and qualitative analyses, the interrelatedness of the aspects could be conceptualized in a framework, as illustrated in . When managing a 3ICP, such as CASO, the central and most important aspects are the Organizational aspects, and Information/communication aspects. Regarding the Organizational aspects, the focus should be on a clear agenda for meetings, and the whole project. The roles of responsibility, regarding what and when, and the goals and expected outcomes should be clearly defined from the start of the project with explicit procedure of project management.

Figure 2. Explanatory conceptualization of (inter)relationships between most important aspects in international, interdisciplinary, and intercultural projects.

Equally important when interacting in 3ICP are the Communication aspects. All project members should be involved from the start of the project, to reach consensus on this, their sense of belonging, ownership, and responsibility/accountability. The Time aspects mediate the interaction between the Organization and Information/communication aspects. On the one hand, the lack of time attenuates the positive influence of good communication on the organization. On the other hand, organizing time for project members to participate in the project, increases communication, as well as the project outcomes. When these core principles are well organized, the Quality aspects of the process will be affected positively, and consequently, the Facilities aspects will also be affected positively. However, it should be noted that, while the Facilities aspects were regarded as a separate item in the quantitative analysis, in the qualitative analysis, these emerged as part of the Organization aspects.

Discussion

The aim of this current study was to offer insight into the elements that played an important role in the development and management of a 3ICP, in the field of health and well-being in higher education. The combined quantitative and qualitative findings revealed the seven key elements: Information/communication; Personal capacity building; Finance; Organization; Time; Facilities; and Quality. These elements relate to each other as the Information/Communication and Organization elements play a central role, with the Time element mediating this central role. Other elements, such as Finance, Facilities, and Quality, are on a secondary level of importance, while Capacity building is a meaningful outcome.

The benefits of international collaborations in health services are obvious (Arakawa and Anderson Citation2020). However, the degree of the impact of international collaboration varies, depending on how it is managed, including communication methods. In line with the Theory of Change, or the Logic model (Hendry Citation1996; Ringhofer and Kohlweg Citation2019; Rogers Citation2014) the findings of this study strongly demonstrate that in the ‘input’ phase of the project, Information/communication plays a pivotal role in the management of the consortium, determining Organizational aspects, mediated by Time. In addition, it affects the Quality of the project, which is related to the outcome measure of Personal Capacity Building. Particularly when several disciplines, nationalities, and cultures are involved in all these parts, other interacting forms of communication exist. Although this is obvious, when other languages or cultures are involved, it is less evident for disciplines. Social workers, health care professionals, and professionals in sports and leisure, differ regarding the working theories they employ, including their ways of interacting with clients. Therefore, working successfully on interdisciplinary projects requires a common language and conceptual understanding for all project members, which comprehensively leads to increasing personal capacities. Developing this common language and concept requires regular face-to-face staff meetings with all project members, as it increases the sense of belonging, and consequently, accountability and ownership. While online meetings are satisfactory to keep in touch on practical issues, it is not effective when dealing with greater interpersonal issues, and more complex project elements, such as discussing theories, or diverse opinions on working procedures.

Another explanation is from a more biosocial perspective. Besides the social characteristics of consciously spending time together, discussing other, or more personal matters, than the project, and work (Gallani Citation2016; Katzenstein and Brice Citation2018), a kind of biological synchronizing appears to occur unconsciously, by aligning physiological parameters, such as breathing and heartbeat (Heinrichs et al. Citation2003). In addition, meeting physically reduces stress and anxiety, stimulating social interaction and empathy (Diamond Citation2019; Van Doesum et al. Citation2018). Therefore, face-to-face meetings between team members are important, not only for collaboration, but also for deeper connection and empathy between them, leading to better and mutual understanding, as well as decisions on project management, expected ‘output’, ‘outcomes’, and ‘impact’.

Additionally, clear, and frequent communication among the management team increases the quality of managerial and organizational processes. Communicating a clear agenda, outcomes, roles, and management, at the start, and during the project, adds to the quality of the project, which the consortium steering group also experienced during this project. In addition, the GANTT Chart and amenities such as working space and ICT infrastructure enhanced communication. Concerning online meeting platforms, the digital divide between the North and the South and the ICT infrastructure disparities have to be considered.

Similar observations are made by Jenkins-Deas (Citation2009), who describes the key factors of the internationalization process. Regarding the implementation of the strategic plan for international education at Malaspina, a reference is made to Aigner (Citation1992), who already ‘ … suggests that success (of internationalisation) will depend on organisation, communication and small-scale change, and that internationalisation is a cumulative effort over time’ (Jenkins-Deas Citation2009, 118). Therefore, in Malaspina, workshops on cross-cultural communication, teaching and learning in a multicultural classroom were organized for the participants in international collaboration. Similarly, during the CASO-project workshops, team building activities on communication were organized for all staff members, to improve intercultural communication and collaboration.

Another aspect, in line with the findings of this current study, and concluded by Jenkins-Deas (Citation2009), is that the most important elements were the clear definition and goals for internationalization, as well as continuous evaluation, as an integral component of the project. These findings are supported by other studies that report various critical success factors on internationalization, e.g. favourable attitudes; active senior management support; internationalization experience; staff development; language proficiency; additional funds; good partner institutions (Bell and Cuypers Citation2010).

Additional critical factors for success are reported by Chan (Citation2004), including the need for partners to have a shared identity, and a strong commitment to the same goals, along with their complementary skills.

These critical success factors in internationalization also refer to personal capacities that are present at the start or are developed during the process. In the CASO-project, this was also observed on the intercultural level, and especially on the interdisciplinary level. Aligning with the basic psychological needs of the Self Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Guay, Ratelle, and Chanal Citation2008), all project members indicated that they had learned from each other interdisciplinarily, interculturally, and internationally (increasing competencies). In addition, they felt intrinsically related and committed to the goal(s) of the project, experiencing a personal bond with the project members (relatedness), while simultaneously feeling free to say and do (autonomy). Therefore, when organizing and executing a 3ICP on capacity building, it is essential to create an open atmosphere, in which project members feel free to actively engage, while becoming acquainted with, learning and appreciating each other. Finally, sufficient budgetary resources, as well as time for participating institutes to develop an internationalization strategy, have been reported as important elements that contribute toward successful internalization projects (Bell and Cuypers Citation2010; Jenkins-Deas Citation2009). In this current study, both time and finances were reported. The lack of time for the project manager hampers good communication, which is needed for effective organization. On the other hand, organizing time for project members to participate in the project, increases communication, personal capacity building, and project outcomes. Finances impact on time, as limited financial resources restrict the working hours available for project members and staff. However, the participants in the CASO-project did not feel restricted by financial implications to complete tasks, suggesting that they were committed to the results of the project, and unaware of working on the project in their spare time.

Conclusions and implications for practice

The purpose of this paper was to offer insight into the development and management of a 3ICP, in the field of health and well-being in higher education. We conclude first that managers of collaborative projects must be mindful of how information is structured and disseminated thus increasing the quality of organizational processes. Second, engaging in open dialogue through hybrid communication methods (face-to-face and online) fosters better levels of accountability and ownership of tasks. Additionally, this has led to capacity development, which further enhanced a sense of belonging through intercultural and interdisciplinary competencies, developed throughout the project. Third, finances, time, and resources are important components impacting the quality and organization of a 3ICP. The following lessons, therefore, were learned from the CASO-project:

Communication is the most important aspect, which affects several parameters for the successful management of a 3ICP.

(a) Online meetings are important to ensure that the team remains connected; however, face-to-face meetings are essential, to make meaningful connections between the participants.

(b) Communication ensures good governance in procedural matters, by keeping record of commonly agreed milestones, as this has an overall impact on the quality of the managerial processes.

(c) Clear and efficient transformation of plans into actionable project activities is required followed by monitoring using a GANTT chart, allows for clarity and purpose in the allocated objectives and reaching project goals.

(d) To strengthen interdisciplinary relationship building, socialization exercises should be undertaken to ensure deeper and meaningful communication and understanding. This may contribute to finding common ground and addressing any potential shortcomings in interpersonal and team functioning, or individual capacity, to work across borders.

(2) Address ownership and responsibility in the first project meeting by having all the participants read through the application in groups, to have clear and shared objectives. Defining and agreeing on a joint focus, as well as links between various working groups within a project, shapes constructive discussions between teams, leading to better synergy, when reaching the milestones, inputs, activities, and performance indicators of the project.

(3) Time is a mediating factor within the management of projects. Timing and understanding the team schedules and academic calendars are important, especially across global borders, with different academic years. Therefore, all stakeholders should negotiate time with their institutions, to substitute tasks, or time, to focus on the deliverables of a collaboration. Simultaneously, the consortium should pay close attention to the way time is allocated, from the inception of the project. It is also important to provide ample time for team building, and this should not be taken for granted.

(4) Personal capacity building is dependent on the way a project is managed, and the communication structure is organized. To ensure that personal capacity building is developed and fostered; intercultural, interpersonal, and interdisciplinary competencies should be embedded into various activities of the different teams. For instance, the use of digital meetings (netiquette) must be addressed and identified for team members at the inception of the project, and individually upskilled if necessary. Circumstances may require the use of other technology and online skills, which may not necessarily be familiar to all the stakeholders. Therefore, personal competence and capacity development may be required in an area that facilitates collaboration across borders by online means.

(5) Financial management as part of managing a 3ICP is an essential aspect as this influences time and other resources, to ensure sustainability and continuity of the programme over a prolonged period.

(6) In the planning phase of the project, institutional vision, support, and organizational culture should be considered. Logistical organization, in terms of physical distances, as well as academic calendars, could impact on successful collaborative efforts of online–offline working.

In conclusion, this paper contributes to the strengthening of the management of a 3ICP. While contextual differences are acknowledged, when working across borders, the richness of such collaborations outweighs some of the managerial challenges that may be experienced. This project not only strengthened and expanded the existing study programmes of the universities but also added to personal capacity building in the different communities. In this, external stakeholders’ involvement like NGOs are important as they are key to delivering the projects within communities. Ultimately, the authors recommend that future studies of this nature consider the sustainability of international collaborative projects, differences in communication between countries, hierarchical structures, diversity management, as well as behavioural aspects such as social cohesiveness and experienced team success and performance.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the CASO project participants for their contribution to this study.

Disclosure statement

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication [communication] reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aigner, J. S. 1992. Internationalizing the University: Making it Work. Springfield, VA: CBIS Federal, Inc.

- Almansour, S. 2015. “The Challenges of International Collaboration: Perspectives from Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University.” Cogent Education 2 (1): 1118201. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2015.1118201.

- Arakawa, N., and C. Anderson. 2020. “Challenges and Opportunities in Conducting Health Services Research Through International Collaborations: A Review of Personal Experiences.” Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 16 (11): 1609–13.

- Beekhoven, S., K. Hoogeveen, and J. Maarse. 2018. De impact van Erasmus+. Een kwalitatief onderzoek naar het Erasmus+ subsidieprogramma (2014-2020). KA1 stafmobiliteit en KA2 strategische partnerschappen. Utrecht, Netherlands: Sardes. https://www.erasmusplus.nl/sites/default/files/assets/Downloads/2019/O%26 T/Kwalitatief%20onderzoek%20impact%20E%2B%20organisatie%20niveau%20(2018).pdf.

- Bell, D., and M. M. L. Cuypers. 2010. “Sustainable Collaboration in Higher Education: The Case of the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (South Africa) and Fontys University (Netherlands).” Journal of Business and Management Dynamics (JBMD), 12–27. http://digitalknowledge.cput.ac.za/bitstream/11189/2506/1/bell_sustainable_jbmd_2010.pdf.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Caring Society [CASO]. 2016. “European and South African Universities Team Up for Large International Project.” www.caringsociety.eu.

- Chan, W. Y. 2004. “International Cooperation in Higher Education: Theory and Practice.” Journal of Studies in International Education 8: 32–55. doi:10.1177/1028315303254429.

- Connell, J. P., and A. C. Kubisch. 1998. “Applying a Theory of Change Approach to the Evaluation of Comprehensive Community Initiatives: Progress, Prospects, and Problems.” In New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Theory, Measurement, and Analysis. Vol. 2, edited by K. Fullbright-Anderson, A. C. Kubisch, and J. P. Connell, 15–44. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2008a. “Self-determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health.” Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 49 (3): 182–5.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2008b. “Facilitating Optimal Motivation and Psychological Well-Being Across Life’s Domains.” Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 49 (1): 14–23.

- De Korte, K., A. Van den Broek, and C. Ramakers. 2018. De Impact van Erasmus+. Een kwalitatief onderzoek naar buitenland ervaringen Erasmus+ van studenten en stafleden. Nijmegen: ResearchNed. https://www.erasmusplus.nl/sites/default/files/assets/Downloads/2019/O%26 T/Factsheets_impact_KA1-KA2-mbo-ho.pdf.

- De Wit, H., ed. 2009. EAIE Occasional Paper 22. Measuring Success in the Internationalisation of Higher Education. Amsterdam: European Association for International Education [EAIE].

- Diamond, L. M. 2019[2018]. “Physical Separation in Adult Attachment Relationships.” Current Opinion in Psychology 25: 144–7.

- Erasmus+. 2017. Celebrating 9 Million Participants. Strasbourg: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/anniversary/erasmusplus-9-million_en.

- Erasmus+. 2021. Impact Tool. Strategic Partnerships [KA2]. https://www.erasmusplus.nl/en/impacttool-strategicpartnerships.

- Erasmus Student Network. 2020, February. Erasmus Jobs – Bridging the Skills Gap for the Erasmus Generation. https://esn.org/news/erasmusjobs-bridging-skills-gap-erasmus-generation.

- European Commission. 2019. Erasmus+ Higher Education Impact Study. Luxembourg City: Publication office of the European Union. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/94d97f5c-7ae2-11e9-9f05-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

- Evans, C., C. Kandiko Howson, A. Forsythe, and C. Edwards. 2020. “What Constitutes High Quality Higher Education Pedagogical Research?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (4): 525–46. doi:10.1080/02602938.2020.1790500.

- Fittipaldi, D. 2020. “Managing the Dynamics of Group Projects in Higher Education: Best Practices Suggested by Empirical Research.” Universal Journal of Educational Research 8 (5): 1778–96. DOI: 10.13189/ujer.2020.080515.

- Gallani, M. C. 2016. “International Collaboration in the Nursing Agenda in the Coming Decades.” Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 24: e2739. doi:10.1590/1518-8345.0000.2739.

- Guay, F., C. F. Ratelle, and J. Chanal. 2008. “Optimal Learning in Optimal Contexts: The Role of Self-Determination in Education.” Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 49 (3): 233–40.

- Heinrichs, M., T. Baumgartner, C. Kirschbaum, and U. Ehlert. 2003. “Social Support and Oxytocin Interact to Suppress Cortisol and Subjective Responses to Psychosocial Stress.” Biological Psychiatry 54 (12): 1389–98.

- Hendry, C. 1996. “Understanding and Creating Whole Organizational Change Through Learning Theory.” Human Relations 49 (5): 621–41.

- Jenkins-Deas, B. 2009. “Chapter 10: The Impact of Quality Review on the Internationalisation of Malaspina University-College, Canada: A Case Study.” In Measuring Success in the Internationalisation of Higher Education. EAIE Occasional Paper 22, edited by H. De Witt, 111–24. Amsterdam: European Association for International Education (EAIE). http://proxse16.univalle.edu.co/~secretariageneral/consejo-academico/temasdediscusion/2014/Documentos_de_interes_general/Lecturas_Internacionalizacion/Measuring%20internasionalisation%20EAIE.pdf.

- Katzenstein, J., and W. D. Brice. 2018. “Capacity Building in a Tanzania Nursing School: An International Collaboration Case.” Journal of Business Diversity 18 (3): 26–36.

- Khor, K. A., and L. G. Lu. 2016. “Influence of International Co-authorship on the Research Citation Impact of Young Universities.” Scientometrics 107 (3): 1095–110. doi:10.1007/s11192-016-1905-6.

- Mark, M.M. (2015). “Mixed and multimethods in predominantly quantitative studies, especially experiments and quasi-experiments.” In The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry, edited by Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber and R. Burke Johnson, 21–41. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199933624.001.0001.

- Parr, A., A. Binagwaho, A. Stirling, A. Davies, C. Mbow, D. O. Hessen, H. Bonciani Nader, et al. 2022. Knowledge-driven actions: Transforming higher education for global sustainability. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380519

- Ringhofer, L., and K. Kohlweg. 2019. “Has the Theory of Change Established Itself as the Better Alternative to the Logical Framework Approach in Development Cooperation Programmes?” Progress in Development Studies 19 (2): 112–22.

- Rogers, P. 2014. Theory of Change. Methodological Briefs: Impact Evaluation, No. 2. Florence: United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF] Office of Research – Innocenti. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ucf/metbri/innpub747.html.

- Rørstad, K., D. W. Aksnes, and F. N. Piro. 2021. “Generational Differences in International Research Collaboration: A Bibliometric Study of Norwegian University Staff.” PLoS ONE 16 (11): e0260239. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260239.

- Van Doesum, N. J., J. C. Karremans, R. C. Fikke, M. A. De Lange, and P. A. Van Lange. 2018. “Social Mindfulness in the Real World: The Physical Presence of Others Induces Other-Regarding Motivation.” Social Influence 13 (4): 209–22. doi:10.1080/15534510.2018.1544589.

- Van Vught, F., M. Van der Wende, and D. Westerheijden. 2002. “Globalisation and Internationalisation: Policy Agendas Compared.” In Higher Education in a Globalising World, edited by J. Enders and O. Fulton, 103–20. Part of Higher Education Dynamics Book Series (HEDY, Volume 1). Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-0579-1_7.