ABSTRACT

Higher education (HE) students experience rates of depression and anxiety substantially higher than those found in the general population. Many psychological approaches to improving wellbeing and developing student resilience have been adopted by HE administrators and educators, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic. This article aims to review literature regarding integration of resilience and wellbeing in HE. A subsequent aim is to scope toward developing foundations for an emerging discipline specific concept – designer resilience. A literature scoping review is applied to chart various conceptual, theoretical and operational applications of resilience and wellbeing in HE. Twenty-seven (27) articles are identified and analysed. The scoping review finds that two general approaches to implementing resilience and wellbeing training exist in HE. First, articles reacting to a decline in student mental health and remedying this decline through general extra-curricular resilience or wellbeing programmes. Second, articles opting for a curricula and discipline-specific approach by establishing why resilience will be needed by future graduates before developing and testing new learning experiences. The presence of cognitive flexibility, storytelling, reframing and reflection lie at the core of the practice of resilience and design and therefore offer preliminary opportunities to develop ‘designer resilience’ training. Future research opportunities are identified throughout the article.

Introduction

Higher education (HE) students experience rates of depression substantially higher than those found in the general population (Ibrahim et al. Citation2013). Scholars go as far as to suggest there is a ‘HE mental health crisis’ (Shek et al. 2017). This crisis has deepened during the global pandemic where students have faced a significant array of challenges (Lederer et al. Citation2021).

One avenue for supporting student wellbeing and academic performance in HE is the positive psychology construct of resilience. Broadly defined, resilience is the ability to bounce back from adversity and cope with stress (Southwick and Charney Citation2018). Psychological resilience is formed through life experiences and acquirable through cognitive and behavioural training (Southwick and Charney Citation2018). Importantly, resilience acknowledges that adversities, stressors and setbacks are part of life and thus cannot be totally eradicated (Wong Citation2011). This perspective suits the HE environment as academic stress and setbacks are viewed as part of the transition to becoming a professional (Eisenberg, Lipson, and Posselt 2016).

Beyond the HE environment, the climate crisis and other grand challenges will require resilient leaders who can orchestrate socio-technical transitions. These leaders will benefit from the presence of psychological capital across a career defined by stressors beyond their control (Luthans, Luthans, and Avey Citation2014). While problem-solving approaches exist that provide methodological and technical expertise to guide these transitions (Geels Citation2004), an emphasis on the resilience of the problem solver to thrive in a career addressing wicked problems remains an afterthought. Confronting this afterthought is critical given HE students will grapple with challenges such as 2050 carbon zero goals, United Nations Sustainable Development goals and other global commitments that have thus far presented more rhetoric rather than action.

Why scope to designer resilience?

Design is a field that can positively contribute to addressing ill-defined problems, as designers stimulate integrative action and synthesis of constraints allowing exploration and discovery of new possibilities (Buchanan Citation1992; Rittel and Webber Citation1973). Design problems are diverse, yet involve the convergence of human, technology and organisational considerations. A design problem could be to conceptualise Covid-19 ‘safe’ public transportation or to propose services and strategies that enable circular economies. Design is therefore represented in literature as a science of problem solving (Simon Citation1996) and form of inquiry (Schön Citation1983; Dorst Citation2011).

Design involves negotiating uncertainty and ambiguity. Processual uncertainty in design stems from unique theoretical markers; no one correct solution is deducible (Simon Citation1996), problems and solutions co-evolve (Dorst Citation2011), the value of proposed solutions are always contestable (Liedtka Citation2015) and implementing solutions encounters institutional resistance (Klitsie, Price, and Santema Citation2021). The experiential learning process at the heart of design (Beckman and Barry Citation2007) requires designers to be reflexive to both technical solutions (Crilly Citation2015), and higher-order goals (Simon Citation1996).

As a consequence of these nuances, design education is founded on pedagogical techniques that encourage exploration, creativity and pluralism in the studio setting. In ideal circumstances, design education has transformative potential, producing students who have capabilities, knowledge and skills to bring about important societal changes and positive impact. Design students also learn about their professional design identity – who they are and what values and principles they stand for manifested through their work (Tracey and Hutchinson Citation2018; Baha, Koch, Sturkenboom, Price and Snelders Citation2020). In less than ideal circumstances, design educators instruct students to replicate iconic designs with technical precision rather than unlock inner creativity (Baha et al. Citation2020). These students learn to please superiors and require ongoing instruction. The latter does naught to prepare independent, critical and enlightened new leaders that can drive urgent socio-technical transitions.

Aim and scope

This article aims to review literature concerning the integration of resilience and wellbeing in HE. The article scopes from broad to specific by developing foundations for an emerging concept – designer resilienceFootnote1 – that can eventually respond to design-specific adversities previously described. While this article scopes to the emerging concept of designer resilience, there continually lies possibilities for generalisability to other disciplines. These horizontal connections are explored throughout the article given the transdisciplinary audience of this journal.

Method

Scoping literature review

A scoping review is a form of literature review involving multiple structured searches (Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010). Peters and colleagues (Citation2015, 141) state of scoping reviews, ‘In general, scoping reviews are commonly used for ‘reconnaissance’ – to clarify working definitions and conceptual boundaries of a topic or field.’ In this article, three structured search cycles are performed. The author of this article with expertise in design research, design education and design practice conducted the review. Prior research on the wellbeing of design students during the SARS-Covid-19 pandemic (Price and Bijl-Brouwer Citation2021) and the opportunity to shape post-pandemic HE (Bijl-Brouwer and Price Citation2021) provide additional context for this research.

Research questions and scoping approach

Research questions informing search parameters are:

How are resilience and wellbeing conceptualised in HE literature?

How are resilience programmes operated in HE and what are the benefits and limitations of various approaches?

What are current notions of designer resilience?

Scoping reviews require inclusion criteria in order to regulate data collection and synthesise evidence. Inclusion criteria for selection of articles is as follows:

Articles offer an empirical, theoretical or conceptual lens of resilience within the context of HE;

Where the article does not explicitly present resilience in HE, it does present wellbeing in HE;

Where the article does not present wellbeing or resilience in HE, resilience and or wellbeing are presented in another context that is transferable to HE, for example in learning communities or in primary/secondary education;

The article is published in a peer-reviewed journal;

One version of an article is selected, with obvious duplicates of an article excluded. Where an article is more than approximately 30% different (i.e. conference to journal articulations), the article is selected.

Systematic and scoping literature reviews are often completed in teams of researchers. In research teams, inter-coder reliability can be established to validate the analyses. This scoping review is conducted by a single researcher and so possible bias-related limitations are present. To mitigate bias in this study, progressive research quality checks have been conducted with a critical reviewer who has extensive experience in executing systematic literature reviews. These progressive review sessions check quality at each phase of the scoping review process to ensure the method is reliably executed.

Search 1

Key words applied were:

Resilience + higher education + wellbeing

Key words were separated with the Boolean operator and/or. No year of publish parameters were set. Thirty-four (34) databases including ScienceDirect, IEEE databases and JSTOR databases were searched with 187 results returned. Based on title, keyword an abstract scan, twenty-one (21) articles of significance were retrieved. Eleven (11) articles were excluded after full-text reading because a lack of relevance to resilience or wellbeing in HE. Further, one article was removed during full text reading as it related to resilience of built HE infrastructure. The final number of articles selected from Search 1 is ten (10).

Search 2

Search 2 applies a ‘2017–2021’ year parameter and applies the key words:

Higher education + university + college + student + resilience + enhance + program

Boolean operators and/or separate keywords entered. This search protocol is an intentional extension of the work of Brewer et al. (2019), found in Search 1, who applied the same scoping review process in 2007–2017. The intention of extending upon the work of Brewer et al. (2019) is twofold. First, to advance conceptual and theoretical clarity regarding resilience in HE as this was a key recommendation of Brewer and colleagues. Second, because of the changed circumstances of the global pandemic, to identify the most recent literature (Lederer et al. Citation2021).

Thirty-four (34) databases including ScienceDirect, IEEE databases and JSTOR databases are searched with 181 papers returned. A title and abstract scan of 181 identified papers was conducted. Articles excluded relate to the resilience of technical systems, such as IT platforms in HE. Eighteen (18) articles were retrieved after this scan. Nine (9) articles were excluded after further reading because a lack of relevance to resilience and or wellbeing in HE was established. One paper was excluded during full text reading because it again concerned the resilience of HE built infrastructure, not students. The final number of articles selected from Search 2 is eight (8) articles.

Search 3

Search 3 applies the key search words:

Wellbeing + Resilience + Higher education + Design

Key words are separated by Boolean operators and/or. 34 databases including ScienceDirect, IEEE databases and JSTOR databases were searched. As no articles related to design appeared in either Search 1 or 2, Search 3 kept the recent timeframe constraints of 2017–2021 to maintain a search for most recent articles responding to the mental health crisis acknowledged in HE. The presence of design within the keywords serve to scope the review toward discipline specific literature.

The number of articles returned is 359. 359 articles are title and abstract scanned for relevance to the research questions and inclusion criteria. Articles excluded typically view resilience as part of a technical system under stress. For example, many of the excluded articles examined how specific built infrastructure can remain resilient during disaster. Eleven (11) articles were retrieved after this process, with two articles excluded following further reading due to a focus on the resilience of built infrastructure in HE. The final number of articles selected from Search 3 is nine (9) articles.

Results

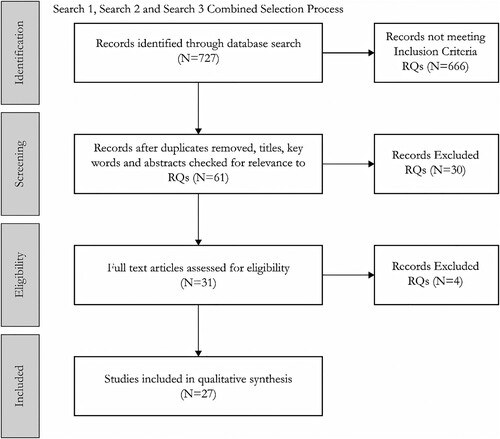

As required by Peters et al. (Citation2015, 144) for scoping reviews, a PRISMA diagram of articles is presented in . This figure shows the review decision process. A list of reviewed articles is located in . A full list of article references is accessible in the Appendix. The number of articles excluded through title and abstract reading is evidence to the huge variety of literature. The results of each search are presented in a thematic format addressing the stated research questions. This format synthesises articles to critically compare and contrast, identify gaps in knowledge and reveal opportunities for educational innovation.

Table 1. List of journals reviewed.

Conceptualising resilience and wellbeing in HE

Many diverse definitions of resilience were encountered across the three searches. A convergence in all definitions involved:

‘Bouncing back’ to perform in spite of adversity;

Undergoing adaption without significant loss of function;

Growing overtime as a tolerance or ‘a thicker skin’ to adversities is developed, and;

Deliberately building peer networks for collective support.

Many approaches for developing resilience and supporting wellbeing are conceptualised across reviewed literature. Articles link resilience to emotional intelligence, with many articles featuring mindfulness training as an approach to build resilience (Akeman et al. 2020; Goodenough et al. 2020; Hurley et al. 2020). Several empirical articles investigate self-efficacy, self-esteem, confidence and motivation in relation to either wellbeing or resilience of HE students (Cassidy 2015; Robbins, Kaye, and Catling 2018; Turner, Scott-Young, and Holdsworth 2017). These studies demonstrate how psychology as a field offers those interested in supporting or studying student wellbeing and resilience a plethora of options, approaches and techniques to operationalise their goals. However, as Brewer and colleagues (2019) identify this has led to a conceptually diffuse literature landscape with many subsequent methodological approaches.

The described studies thus far do share proximity under the umbrella of cognitive psychology where cognition, behaviour and thoughts (CBT) provide building blocks of human experience. The interrelation of CBT is viewed as a developing process that can be adapted to improve how people experience everyday life, for example in treating depression and anxiety. CBT therapy is suited to supporting individuals who have little control over their environment such as HE students who are unable to remedy institutional challenges such as increasing degree fees, a culture that rewards performance, increasing class sizes and teacher shortages. These topical problems are highlighted in a number of articles reviewed in this study such as Duncan, Strevens, and Field (2020), Nicklin, Meachon, and McNall (2019) and Azorin (2020).

Duncan, Strevens, and Field (2020, 88) are most assertive in their critique of these factors describing the neoliberal turn of universities from public to private good, and the departure from egalitarian values of social liberalism. Azorin (2020) proposes that Covid-19 be the ‘supernova’ to which institutional change across Spanish education can be exacted.

Another theoretical viewpoint visible across the three searches was presence of positive psychology as a general movement underlying interest in individual wellbeing and fulfilment. In the ‘second coming’ of positive psychology, termed positive psychology 2.0 the importance of resilience becomes clear. Positive psychology 2.0 posits that negative events can be transformative sources of growth provided the individual has the right ‘tools’ (Hogan 2020). The importance of cognitive flexibility for reframing negative events and the ability to tell stories to peers provide two prominent ‘tools’ described by articles exploring the conceptual appropriateness of resilience in HE (Audley and Stein 2017; Maree, Pienaar, and Fletcher 2018; Nicklin, Meachon, and McNall 2019).

Of interest given the scope of designer resilience is how Turner, Scott-Young, and Holdsworth (2019), and Duncan, Strevens, and Field (2020) develop discipline specific profiles establishing why resilience is required in their respective fields (construction management and law). Construction managers and lawyers will face careers characterised by stressful experiences that erode general wellbeing. Resilience becomes a capability to be drawn upon continually when faced with particularly stressful events, enabling an individual to remain effective as a practitioner.

These two discipline specific articles (Turner, Scott-Young, and Holdsworth 2019; Duncan, Strevens, and Field 2020) demonstrate how general resilience can be conceptually appropriated to meet the specific demands of a field of practice. Their approach relies on providing an account of why their respective disciplines necessitate resilience.

Operationalisation of resilience programmes in HE

Across all searches, it was clear that HE institutions are under pressure to integrate resilience programmes in order to:

Prepare students for practice as the next generation of problem solvers and leaders;

Respond to increasing mental health and wellbeing concerns for students in HE, and;

Protect what is a marginal student-retention-reliant business model.

Table 2. Benefits and limitations of general and curricular-specific HE resilience programmes.

In three papers, (Goralnik and Marcus 2020; Goodenough et al. 2020; Hurley et al. 2020), resilience programmes are connected to specific curricula within HE. Hurley and colleagues (2020) connect the requirement for emotional intelligence (EQ) and resilience to specific experiences that nurses conducting practical placements encounter. EQ and resilience are non-technical work skills (NTWS) of nursing and are thus elevated into the curricula of Nursing education.

Goodenough and colleagues (2020) aim to increase the employability of their Bachelor of Science students by investigating the efficacy of internships. Based on their results, Goodenough and colleagues recommend that students take internships in order to develop flexibility and stress coping strategies that contribute to resilience and career readiness.

Goralnik and Marcus (2020) identify the need for resilience in courses of natural sciences, biology and geography where students converge under the collective challenge of ‘sustainability’. Students in these courses will confront the wicked problem of climate change which encompasses value conflicts, tensions, ethical and moral dilemmas and inequalities requiring emotional intelligence, patience and resilience. Goralnik and Marcus test the efficacy of mindfulness training through contemplative pedagogy, finding that meditation via ‘5 minutes of silence’ to begin class calms students and clarifies immediate intellectual challenges. Whether this practice is sustained by students beyond the study is unknown.

Other papers located in HE (Akeman et al. 2020; Nicklin et al. 2019; Reyes et al. 2018) disconnect resilience interventions from discipline specific curricula, thus offering extra-curricular interventions as part of general student support. Reyes and colleagues follow 20 US military veterans transitioning back to civilian life and undertaking HE. These ‘vets’ require resilience to ‘integrate’ back into society while coping with mild to severe classifications of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) developed as a result of their military service.

Empirical literature encountered across the three searches treads a fine line between investigating a psychological construct to advance science, while investing time to grow students as people. Brewer and colleagues (2019) also highlight methodological problems in the literature and these issues prevail during the updated search parameters of Search 2. For example, asking HE students to spend 1–2 hours completing a survey with little incentive is inconsiderate of their time. A large drop-out of participants mid-survey cannot be surprising to researchers. There is risk that journals that favour statistical reliability achieved from large participant samples may encourage research designs that treat students as numerical entities while not taking significant steps to benefit these same students.

Reyes et al. (2018) provide an exemplary methodology in this respect. They take time to qualitatively interview war ‘vets’ and follow their integration from service in HE. The process of interviewing these vets serves as a moment to build rapport and as the interviews were conducted by psychologists, even provide clinical care.

Another factor not always managed by reviewed studies relates to participant harm. Nicklin, Meachon, and McNall (2019) identify that conflict is required in order to promote resilience. Therefore, programmes that seek to develop resilience in HE students must tread a fine balance between evoking and reflecting upon bad experiences while providing safe learning environments. An important consideration raised by Audley and Stein (2017) is that protectionism of students does not foster resilience. Any programme or intervention for resilience must be mindful of the ethical dimension and involve psychologically trained experts in the planning and execution of such programmes.

Beyond Brewer and colleagues’ (2019) conceptual and methodological critique of literature lies a deeper unaddressed institutional issue. Studies that treat students as recipients of resilience training fail to empower those same students to create and co-create with educators and administrators possible solutions to the problems facing them. While studies like Maree, Pienaar, and Fletcher (2018) encourage students to design the lives they want to live, approaches like these treat current institutional deficiencies such as increasing class sizes, increasing degree fees and an unchecked performance culture as norms that students must adapt to rather than challenge or even solve. Rather, resilience enables students to permit these norms, as described by Duncan, Strevens, and Field (2020) and Nicklin, Meachon, and McNall (2019) in particular. An opportunity to prepare independent, critical and enlightened new leaders who treat these conditions not as norms but as structures to be improved offer opportunities for new forms of HE.

This opportunity is highlighted by Kim and Fuessel (2020) when presenting their Changemakers Campus at Ashoka U. Kim and Fuessel reflect on integrating the Changemakers programme across 500 HE campuses. They present four principles that foster Changemaking graduates and community outcomes. Referring to principle four, ‘systemic leadership’, they state,

Leaders need to embody these values and also action them across the organization as they seek to innovate systems for more equitable outcomes – whether across campus or society. That includes recognizing that leadership can be enacted by anyone and often emerges through interaction and experimentation (2).

Early notions of designer resilience

Maree, Pienaar, and Fletcher (2018) and Andrahennadi (2019) are the only articles that make explicit connection to design across the three searches. Andrahennadi (2019) being the only article that makes design discipline-specific placement of resilience and wellbeing in HE. While the article lacks data collection rigour regarding how this measurably benefits designers it does valuably reflect on how ‘Eastern’ traditions such as mindfulness are appropriated by ‘Western’ society under terms such as contemplative practice. During this appropriation, such practices lose their depth and authenticity as a total approach to life. Aside from developing calmness and clarity during reflection, it is unclear how Andrahennadi's programme connects to and supports other activities within design thinking such as analysis, synthesis and prototyping (Beckman and Barry Citation2007).

Maree, Pienaar, and Fletcher (2018) show how life-design counselling activities, for example ‘drawing my own lifeline’, ‘talking about earliest memories’ and ‘drawing family constellations’ are effective with young women. These activities concern reflection rather than initiating problem solving. The presence of visualisation and storytelling in these activities shares practical affinity to designing. While developed in secondary education and only with female participants, the activities described by Maree and colleagues do offer immediate transfer into the HE setting to shape learning activities.

Many articles reviewed provide an indirect contribution toward the emerging concept of designer resilience. Cassidy (2015) describes how fixed beliefs lower an individual's ability to remain resilient. Goralnik and Marcus, (2020) and Audley and Stein (2017) make important connections between the presence of wicked problems, particularly those of climate change, and the need for resilient problem solvers. Audley and Stein (2017) propose that reframing be ‘the framework’ that allows people to unlock growth from negative events. Reframing, storytelling and exploration are all hallmarks of design practice.

The limited range of articles with a direct connection to design presents a distinct gap in literature. This gap concerns how design students are prepared for the rigours of practice beyond a focus on methods and methodology. Two practice-based opportunities for future research are also identified:

How are professional designers resilient to external stressors that impact their problem solving process such as managing budget and client expectations?

How are professional designers resilient to stressors within the design process such as remedying fixation or navigating uncertainty?

Regarding design education, initial linkages between resilience and design are presented in . These linkages offer opportunities to integrate resilience into design curricula to enrich learning experiences. The linkages are accessible to bachelor and master level studies. Academic counsellors can also benefit from these linkages by better serving design students who approach them for support.

Table 3. Linkages between resilience and design.

Discussion

The sheer range of approaches and techniques adopted to develop resilience in HE has created a diffuse literature landscape confirmed by Brewer et al. (2019) where little conceptual clarity exists. However, two general approaches are identified in this literature review. First, articles that document resilience and wellbeing training to alleviate immediate health concerns of HE students in order to boost retention (Clafferty and Beggs 2021; Eisenberg, Lipson, and Posselt 2016) and enable students to better ‘cope’ with university (Akeman et al. 2019; Cassidy 2015; Robbins, Kaye, and Catling 2018). Second, articles specifying why resilience is required in HE in relation to specific professional challenges in the case of nursing (Hurley et al. 2020), the built environment (Turner, Scott-Young, and Holdsworth 2017), law (Duncan, Strevens, and Field 2020) and sustainability (Goralnik and Marcus 2020). These articles attempt to remedy described weaknesses in HE education through integration of resilience training into curricula.

While all HE-based articles point rhetorically toward general decline in the mental health of students, many articles do not confront institutional deficiencies that will further exacerbate the decline of students’ health. In a small number of articles (Duncan, Strevens, and Field 2020; Nicklin, Meachon, and McNall 2019: Azorin 2020), issues like performance culture, insecure living situations, increasingly high degree fees, increasingly large class sizes and teacher shortages are raised. The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the intensity to which students experience these challenges (Lederer et al. Citation2021). While Duncan, Strevens, and Field (2020); Nicklin, Meachon, and McNall (2019); Azorin (2020) and Lederer et al. (Citation2021) make recommendations for institutional reform to address these concerns, the majority of articles do not.

A lack of author agency to enact systemic reform may be reason for an absence of recommendations that confront institutional shortfalls across articles reviewed. Authors may also be pragmatic, doing what little they can with the limited resources available as they balance educational responsibilities with research commitments. As a result, HE students have been represented as conglomerate in their needs and passive in their role as students rather than empowered and possessing solutions to the problems proximate to them. Kim and Fuessel (2020) go furthest in arguing for empowered ‘systemic leaders’ yet details about the learning experiences that produce these qualities is limited in their article.

Discussion thus far has fuelled two critical questions not addressed in reviewed literature:

What if resilience training allowed students to co-create with peers, educators and administrators the types of learning environments where they could explore their own evolving sense of identity and anticipate likely challenges in their prospective careers?

What if resilience training was a way to reflect and sense make upon experiences of working and living within institutions under stress?

The integration of resilience training to support wellbeing presented across the literature either occurred within curricula or as extra-curricular. What is interesting is how discipline-specific resilience training responds to and advances the praxis-related problems of these fields (law, nursing, built environment and natural sciences). For example, the creative approaches to addressing practice-education gaps facing placement nurses in high stress environments (Hurley et al. 2020), or praxis challenges facing students attempting to reconcile how theoretical climate models are appropriated for political purposes in Goralnik and Marcus’ sustainability classroom (2020). Such learning experiences require more than instruction from a textbook or lecture. These learning experiences push students to view the limitations of their chosen discipline and decide where outside help or research is required. These resilience programmes therefore have the possibility to enrich the quality of education provided while concurrently contributing to the development of fields through research that addresses lingering practice-education and praxis gaps.

Integrating resilience into design education

Through this systematic scoping review, a research gap pertaining to designer resilience is revealed. While there is literature that connects mindfulness to design (Andrahennadi 2019), this work is more a reaction to the need for calmness and clarity in a highly connected world, rather than acknowledgment of the internal cognitive and behavioural adversities faced within the design process. These adversities stem from the theoretical markers of design compounded by the ambition of designers to frame problems in systemic rather than reductive terms in order to create societal impact.

Future research must develop theoretical frameworks and experiment with new learning experiences for developing designer resilience. Initial starting points for prototyping should be:

Developing activities and materials for evoking resilience in the designer by initiating learning through reframing of past setbacks and storytelling to peers;

Developing activities and materials that first confront the designer with a novel setback as a new cognitive demand, then stimulating cognitive flexibility through role playing;

Developing activities and materials that ask the designer to imagine and anticipate setbacks encountered in a career of addressing wicked problems such as climate change to engage foresight;

Developing co-creation activities and working groups between HE students, educators and administrators in order to challenge underlying topics such as the effect of increasing class sizes, increasing degree fees and heightening performance culture.

Conclusion

The sheer range of approaches and techniques adopted to develop resilience in HE has created a diffuse literature landscape. Findings from the scoping review show that two approaches emerge in this landscape. First, articles that react to a decline in student mental health and attempt to remedy this through general resilience or wellbeing programmes. Second, articles that establish how the future demands of graduates will require resilience that is embedded deep within disciplinary practice. Reviewed articles in the fields of nursing, law, built environment and sustainability demonstrate conceptually how resilience can be incorporated into the classroom.

Many practical and conceptual synergies between resilience and design that provide pathways for developing educational innovation. The presence of cognitive flexibility, storytelling, reframing and reflection lie at the core of the practice of resilience and design. Shared synergies provide opportunities to create principles and frame learning experiences that can be implemented in the design studio or classroom to develop designer-specific resilience. Further applied research is required to action this ambition.

In summary, the article makes the following three major contributions to the extant literature:

Identifies that the HE sector is addressing student resilience and wellbeing concerns via general and discipline-based approaches;

Establishes benefits and limitations of existing general and curricula specific resilience and wellbeing programmes to improve wellbeing, and;

Develops the foundations for the emerging concept of designer resilience.

The implications of this article are that resilience as a diffuse construct can be brought into design education using the identified linkages in as a starting point for development. Further, the prototyping activities outlined in the discussion serve as inspiration for developing designer resilience. While this article has scoped to design education, fields connected by design science such as engineering or architecture can benefit from the disciplinary proximity of this article. More general notions of resilience for creative problem solvers remains an avenue for future research with strong generalizable potential to a wide range of disciplines taught in HE.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Professor Dr Erik Jan Hultink for his critical reviewing and Dr Megan Price for her continued support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 When conducting a ‘Hail Mary’ search into a university database for: ‘Designer Resilience’, no results appeared. When changing tact, and searching for ‘design resilience’, 187 results were returned. However, these articles strongly aligned to a technical construct of resilience nested in engineering, ecology and biology.

References

- Baha, E., M. Koch, N. Sturkenboom, R. Price, and D. Snelders. 2020. “Why am I Studying Design?” Paper presented at DRS2020: Synergy. Design Research Society Conference 2020. Brisbane, Griffith University, August 11-14. doi:10.21606/drs.2020.386.

- Beckman, S., and M. Barry. 2007. “Innovation as a Learning Process: Embedding Design Thinking.” California Management Review 50 (1): 25–56. doi:10.2307/41166415.

- Bijl-Brouwer, M., and R. Price. 2021. “An adaptive and strategic human-centred design approach to shaping pandemic design education that promotes wellbeing.” Strategic Design Research Journal 14 (1): 102–113. doi:10.4013/sdrj.2021.141.09.

- Buchanan, R. 1992. “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking.” Design Studies 2 (2): 5–21. doi:10.2307/1511637.

- Crilly, N. 2015. “Fixation and creativity in concept development: The attitudes and practices of expert designers.” Design Studies 38 (1): 54–91. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2015.01.002.

- Dorst, K. 2011. “The Core of ‘Design Thinking’ and its Application.” Design Studies 32 (6): 521–532. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006.

- Geels, F. W. 2004. “From Sectoral Systems of Innovation to Socio-Technical Systems.” Research Policy 33 (6-7): 897–920. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015.

- Hart, C. 1998. Doing a Literature Review. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Ibrahim, A., S. Kelly, C. Adams, and C. Glazebrook. 2013. “A Systematic Review of Studies of Depression Prevalence in University Students.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 47 (3): 391–400. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015.

- Klitsie, B. J., R. A. Price, and S. Santema. 2021. “Not Invented Here: Organizational Misalignment as a Barrier to Innovation Implementation in Service Organisations” Paper presented at ServDes.2020 – Tensions, Paradoxes, Plurality RMIT University, Melbourne Australia, February 2–15. https://servdes2020.org/events/40-not-invented-here-organizational-misalignment-as-a-barrier-to-innovation-implementation-in-service-organisations.

- Lederer, A. M., M. T. Hoban, S. K. Lipson, S. Zhou, and D. Eisenberg. 2021. “More Than Inconvenienced: The Unique Needs of U.S. College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Health Education and Behavior 48 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1177/1090198120969372.

- Levac, D., H. Colquhoun, and K. K. O’Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science: Is 5: 69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Liedtka, J. 2015. “Perspective: Linking Design Thinking with Innovation Outcomes Through Cognitive Bias Reduction.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 32 (6): 925–938. doi:10.1111/jpim.12163.

- Luthans, B. C., K. W. Luthans, and J. B. Avey. 2014. “Building the Leaders of Tomorrow: The Development of Academic Psychological Capital.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 21 (2): 1919–199. doi:10.1177/1548051813517003.

- Meyer, M. W., and D. Norman. 2020. “Changing Design Education for the 21st Century.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 6 (1): 13–49. doi:10.1016/j.sheji.2019.12.002.

- Peters, M. D., C. M. Godfrey, H. Khalil, P. McInerney, D. Parker, and C. B. Soares. 2015. “Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3): 141–146. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

- Price, R., and M. Bijl-Brouwer. 2021. “What Motivates our Design Students during Covid-19 You?.” Journal of Design, Business and Society 7 (2): 235–251. doi:10.1386/dbs_00029_1.

- Rittel, H. W. J., and M. M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4 (2): 155–69. doi:10.1007/BF01405730.

- Schön, D. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Simon, H. 1996. The Sciences of the Artificial. 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Southwick, S. M., and D. S. Charney. 2018. Resilience. The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108349246

- Tracey, M. W., and A. Hutchinson. 2018. “Uncertainty, Agency and Motivation in Graduate Design Students.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 29 (1): 196–202. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2018.07.004.

- Wong, P. T. P. 2011. “Positive Psychology 2.0: Towards a Balanced Interactive Model of the Good Life.” Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 52 (2): 69–81. doi:10.1037/a0022511.

Appendix: Scoping review articles

Search 1:

1. Cassidy, S. 2015. “Resilience Building in Students: The Role of Academic Self-Efficacy.” Frontiers in Psychology, 6 (article 1781): doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01781

2. Clafferty, E., B. J. Beggs. 2021. “Developing the Academic Resilience of our Students.” AdvanceHE. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/blog/developing-academic-resilience-our-students

3. Duncan, N., C. Strevens, and R. Field. 2020. “Resilience and Student Wellbeing in Higher Education: A Theoretical Basis for Establishing Law School Responsibilities for Helping Our Students to Thrive.” European Journal of Legal Education, 1 (1): 83–115. https://ejle.eu/index.php/EJLE/article/view/10

4. Eisenberg, D., S. K. Lipson, and J. Posselt. 2016. “Promoting Resilience, Retention, and Mental Health.” Student Services, 156 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1002/ss.20194

5. Kim, M., A. Fuessel. 2020. Leadership, Resilience, and Higher Education's Promise. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/leadership_resilience_and_higher_educations_promisehttp://ssir.org/articles/entry/leadership_resilience_and_high_educations_promise#

6. Lederer A. M., M. T. Hoban, S. K. Lipson, S. Zhou, and D. Eisenberg. 2021. “More Than Inconvenienced: The Unique Needs of U.S. College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Health Education & Behavior, 48 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1177/1090198120969372.

7. Brewer, M., G. van Kessel, B. Sanderson, F. Naumann, M. Lane, A. Reubenson, and A. Carter. A. 2019. “Resilience in Higher Education Students: A Scoping Review.” Higher Education Research & Development, 38 (6): 1105–1120. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1626810.

8. Hogan, M. J. 2020. “Collaborative Positive Psychology: Solidarity, Meaning, Resilience, Wellbeing, and Virtue in a Time of Crisis.” International Review of Psychiatry, 32 (7–8): 698–712. doi:10.1080/09540261.2020.1778647.

9. Turner, M., C. M. Scott-Young, and S. Holdsworth. 2017. “Promoting Wellbeing at University: The role of Resilience for Students of the Built Environment.” Construction Management and Economics, 35 (11-12): 707–718. doi:10.1080/01446193.2017.1353698.

10. Robbins, A., E. Kaye, and J. C. Catling. 2018. “Predictors of Student Resilience in Higher Education.” Psychology Teaching Review, 24 (1): 44–52. ISSN: 0965-948X

Search 2:

11. Akeman, E., N. Kirlic, A. N. Clausen, K. T. Cosgrove, T. J. McDermott, L. D. Cromer, at al. 2020. “A Pragmatic Clinical Trial Examining the Impact of a Resilience Program on College Student Mental Health.” Depression and Anxiety, 37(3): 202–213. doi:10.1002/da.22969.

12. Feng, S., L. Hossain, and D. Paton. 2018. “Harnessing Informal Education for Community Resilience.” Disaster Prevention and Management, 27 (1): 43–59. doi:10.1108/DPM-07-2017-0157.

13. Goodenough, A. E., H. Roberts, D. M. Biggs, J. G. Derounian, A. G. Hart and A. Lynch. 2020. “A Higher Degree of Resilience: Using Psychometric Testing to Reveal the Benefits of University Internship Placements.” Active Learning in Higher Education, 21 (2): 102–115. doi:10.1177/1469787417747057.

14. Goralnik, L., and S. Marcus. 2020. “Resilient Learners, Learning Resilience: Contemplative Practice in the Sustainability Classroom.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2020 (161), 83–99. doi:10.1002/tl.20375.

15. Hurley, J., M. Hutchinson, D. Kozlowski, M. Gadd, and S. Vorst. 2020. “Emotional Intelligence as a Mechanism to Build Resilience and Non-technical Skills in Undergraduate Nurses Undertaking Clinical Placement.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1111/inm.12607.

16. Nicklin, J. M., E. J. Meachon, and L. A McNall. 2019. “Balancing Work, School, and Personal Life Among Graduate Students: A Positive Psychology Approach.” Applied Research in Quality of Life, 14 (5): 1265–1286. doi:10.1007/s11482-018-9650-z.

17. Audley, R. S., and N. R. Stein. 2017. “Creating an Environmental Resiliency Framework: Changing Children's Personal and Cultural Narratives to Build Environmental Resiliency.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 7 (2): 205–215. doi:10.1007/s13412-016-0385-6.

18. Reyes, A. T., C. A. Kearney, K. Isla, and R. Bryant. 2018. “Student Veterans’ Construction and Enactment of Resilience: A Constructivist Grounded Theory Study.” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 25 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1111/jpm.12437.

Search 3:

19. Andrahennadi, K. C. 2019. “Mindfulness-based Design Practice (MBDP): A Novel Learning Framework in Support of Designers Within Twenty-First-Century Higher Education.” International Journal of Art & Design Education, 38 (4): 887–901. doi:10.1111/jade.12272.

20. Azorín, C. 2020. “Beyond COVID-19 Supernova. Is Another Education coming?” Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5 (3/4): 381–390. doi:10.1108/JPCC-05-2020-0019.

21. Degbey, W. Y., and K. Einola. 2020. “Resilience in Virtual Teams: Developing the Capacity to Bounce Back.” Applied Psychology, 69 (4): 1301–1337. doi:10.1111/apps.12220.

22. Maree, J. G., M. Pienaar, and L. Fletcher. 2018. “Enhancing the Sense of Self of Peer Supporters Using Life Design-related Counselling.” South African Journal of Psychology, 48 (4): 420–433. doi:10.1177/0081246317742246.

23. Shek, D. T. L., Yu. L, Wu. F. K. Y. Zhu. X, and K. H. Y. Chan, K. H. Y. 2017. “A 4-Year Longitudinal Study of Well-Being of Chinese University Students in Hong Kong.” Applied Research in Quality of Life, 12 (4): 867–884. doi:10.1007/s11482-016-9493-4.

24. Takala, A., and K. Korhonen-Yrjänheikki. 2019. “A Decade of Finnish Engineering Education for Sustainable Development.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20 (1): 170–186. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-07-2018-0132.

25. Therrien, M., S. Usher, and D. Matyas. 2020. “Enabling Strategies and Impeding Factors to Urban Resilience Implementation: A scoping review.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 28 (1): 83–102. doi:10.1111/1468-5973.12283.

26. Turner, M., C. Scott-Young, and S. Holdsworth. 2019. “Developing the Resilient Project Professional: Examining the Student Experience.” International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 12 (3): 716–729. doi:10.1108/IJMPB-01-2018-0001.

27. Zandvliet, D. B., A. Stanton, and R. Dhaliwal, R. 2019. “Design and Validation of a Tool to Measure Associations Between the Learning Environment and Student Well-being: The Healthy Environments and Learning Practices Survey (Helps).” Innovative Higher Education, 44 (4): 283–297. doi:10.1007/s10755-019-9462-6.