ABSTRACT

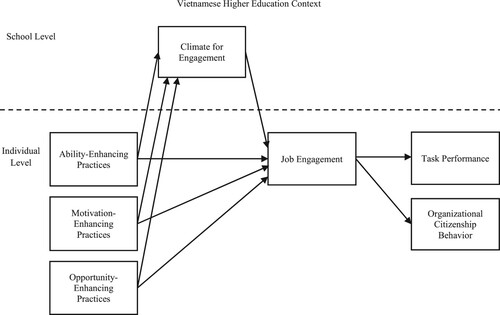

Resting on social exchange theory and the Ability-Motivation-Opportunity framework, this research examined the causal relationships between high-performance work practices, climate for engagement, job engagement, and job performance in the context of Vietnamese higher education. A multiphase, multisource data collection method was applied to 394 pairs of full-time academic staff and their line managers or supervisors working for 14 public and private universities in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Using SEM and MSEM to analyze the data, the research pinpointed that of the three dimensions of high-performance work practices, ability-enhancing and opportunity-enhancing practices had significant and positive influences on Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement. Climate for engagement was a crucial mediator in the influences of ability-enhancing and motivation-enhancing practices on Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement. As their job engagement increased, it led to an improvement in their job performance. These significant findings explain how high-performance work practices promote Vietnamese university academic staff’s job performance.

Introduction

In the current global knowledge society, the place of universities has become preeminent. Through undertaking the core missions of teaching and research, universities contribute to enhancing the national socio-economic development by training a highly skilled workforce and creating a safe and free academic environment for the generation, advancement, and legitimation of knowledge. Academic staff, given their dual duties as teachers and researchers, occupy a major role in operating and accomplishing the universities’ objectives (Mohammadi and Karupiah Citation2020). Their job performance not only helps improve the higher education quality but also contributes to establishing the universities’ research profile (Wiechetek and Pastuszak Citation2022). Hence, improving academic staff’s job performance is significant in promoting the universities’ operation and long-term growth.

One element that influences employees’ job performance is human resource practices (HR practices) yet it is unclear how this relationship occurs. This is identified as a ‘black box’, and there are calls for further investigation into the HR practices and performance relationship (Karadas and Karatepe Citation2019). As Guest (Citation2011, 10) stated, ‘we still do not know which practices or combinations of HR practices have most impact nor when, why or for whom they matter’. Although previous studies generally supported the notion that the utilization of HR practices could have positive outcomes within the Western business context, the picture remains ambiguous for developing Asian countries (Dayarathna, Dowling, and Bartram Citation2019). Given the importance of academic staff’s job performance to university performance and the gaps in the human resource management (HRM) literature, there is a need to study this topic within the higher education context in different countries.

To address this need, the current research examines the causal relationships between high-performance work practices (HPWPs), climate for engagement, job engagement, and job performance in Vietnamese university settings. Accordingly, the article begins with a description of the Vietnamese higher education context, followed by a review of the relevant literature. Next, the research methods and results are sequentially presented. Finally, the discussion and conclusion are drawn.

Vietnamese higher education context

Vietnam is a developing nation, which has the ninth highest population in Asia and the sixteenth highest population in the world (Central Intelligence Agency Citation2022). Since 1986, the Vietnamese Government has implemented a comprehensive reform process, named ‘Doi moi’ that has successfully converted its stagnant, centrally planned, subsidized economy into a socialist-oriented market one. Along with this process, the Vietnamese higher education has witnessed a quick rise in the quantity of universities from 9 universities in 1992–1993 (Hayden and Lam Citation2010) to 237 universities in 2019–2020 (Bộ Giáo dục và Đào tạo Citation2021). The quantity of students has increased considerably from 162,000 students (Hayden and Lam Citation2010) to 1,672,881 students (Bộ Giáo dục và Đào tạo Citation2021) during the same period (See ). In the Vietnamese higher education, universities play a pivotal role in generating, providing, and spreading knowledge. They are permitted to develop all types of higher education programs while other higher education institutions, including colleges and scientific research institutes, are limited to develop two types of collegiate and doctoral programs.

Table 1. Higher education in Vietnam.

Regarding the higher education quality, Vietnam has recently commenced reaching international standards. In 2022, four Vietnamese universities were listed in the 1000 world university league tables of ShanghaiRanking Consultancy (Citation2022), Times Higher Education (Citation2022), and Quacquarelli Symonds (Citation2022), the three leading ranking organizations in the world. However, none of Vietnamese universities were listed in the top 10 universities in Southeast Asia and the top 100 universities in Asia. These results partially show that Vietnamese universities’ performance is still lower than other Asian universities’ performance.

One factor directly affecting Vietnamese universities’ performance is academic staff’s job performance. Nonetheless, few efforts have been made to research how to improve this factor. Most preceding studies, mainly in the Western business context, stated that the application of HR practices could positively affect employees’ job performance yet which combinations of HR practices had most effects and how they affected remained unresolved (Guest Citation2011). According to Alqahtani and Ayentimi (Citation2021), the influences of HR practices on job performance in the higher education context might be different from those in the business context because different actors are involved in managing and administrating HR practices. Within the higher education context, schools are often mandated with the administration of HR practices, embracing training and development, performance appraisals, and promotions even though HR practices reflect organizational actions and are left for HR departments. Thus, HR departments have to coordinate with schools to manage and organize HR practices in order to improve the university competitiveness in areas of teaching, research, and community engagement. For these reasons, the current research investigates the process from which HPWPs promote job performance of Vietnamese university academic staff through their interactions with climate for engagement and job engagement. Accordingly, the subsequent section reviews the HPWPs, job engagement, climate for engagement, and job performance literature.

The influences of HPWPs on job engagement

HPWPs

HR practices are all human resource activities implemented to manage employees and regulate the employment relationship (Armstrong Citation2012). Among those, HPWPs consist of HR practices having more effectiveness in enhancing the performance of employees and organizations (Torrington et al. Citation2009). Drawing on the Ability-Motivation-Opportunity framework proposed by Appelbaum (Citation2000), several scholars such as Jiang et al. (Citation2012) and Messersmith, Kim, and Patel (Citation2018) argued that HPWPs could be categorized into three major dimensions: Ability-enhancing, Motivation-enhancing, and Opportunity-enhancing practices. Ability-enhancing practices (Ability) are utilized to develop appropriate knowledge and skills for employees (e.g. selection, training and development). Motivation-enhancing practices (Motivation) are implemented to motivate employees (e.g. performance-related pay, promotion, and job security). Opportunity-enhancing practices (Opportunity) are executed to give employees opportunities for using their skills and motivation to reach organizational goals (e.g. job autonomy and communication) (Jiang et al. Citation2012). In agreement with these scholars, the current research views HPWPs as an aggregation of three distinct dimensions of Ability, Motivation, and Opportunity.

Job engagement

Job engagement is a relatively long-lasting state of mind showing the concurrent investment of a person’s physical, emotional, and cognitive resources in his or her job (Kahn Citation1990). In the engagement literature, job engagement is often interchangeably used with work engagement and employee engagement. Nevertheless, there are subtle differences between the three concepts. Work engagement is ‘a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption’ (Schaufeli et al. Citation2002, 74). Work engagement focuses on work activity or ‘purposeful human activity involving physical or mental exertion that is not undertaken solely for pleasure and that has economic or symbolic value’ (Budd Citation2011, 2). Employee engagement is an ‘active, work-related positive psychological state operationalized by the intensity and direction of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral energy’ (Shuck, Adelson, and Reio Jr Citation2017, 955). Employee engagement reflects the full experience of an employee’s roles in his or her job, team, and organization. On the contrary, job engagement underlines the extent to which a person is engaged with his or her job. In other words, the center of job engagement is job activities.

Job engagement should not be confused with organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and job involvement. Organizational commitment is a psychological state demonstrating the attachment of a person to his or her organization and impacts his or her decision to remain or leave the organization (Meyer and Allen Citation1991). It pays attention to the organization, whereas job engagement concentrates on the job itself. Job satisfaction is ‘a positive (or negative) evaluative judgment one makes about one’s job or job situation’ (Weiss Citation2002, 175). It depicts the gratification of a person with his or her job condition or characteristic, whereas job engagement emphasizes activation, manifesting a person’s experience of his or her job. Job involvement is ‘a cognitive or belief state of psychological identification’ with a specific job (Kanungo Citation1982, 342). It reflects a dimension of job engagement (i.e. the cognitive dimension), not the entire construct (Christian, Garza, and Slaughter Citation2011). Therefore, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and job involvement are completely separated from job engagement.

HPWPs and job engagement

Resting on social exchange theory (Blau Citation1964), which refers to favors leading to unspecified future obligations between exchange partners, three HPWPs dimensions can affect employees’ job engagement because they symbolize economic and social-emotional resources from organizations, which drive employees to believe that the organizations value the employees’ contributions and show concern about their well-being. As argued by Gong, Chang, and Cheung (Citation2010), Ability (e.g. selective recruitment and extensive training) may manifest the organizations’ interest in employee development. Motivation (e.g. performance-related pay and promotion) may express the organizations’ equal treatment of employees, since the high-performance employees receive higher pay rates and have opportunities to play more important roles in the organizations. Opportunity (e.g. regular communication and job autonomy) may indicate the acknowledgement of employees’ significance and values to the organizations. These perceptions will make employees feel obliged to give positive responses such as enhancing their job engagement.

The influences of HPWPs on engagement was discovered mainly in previous empirical studies within the business context (Alfes et al. Citation2013; Goyal and Patwardhan Citation2020; Yang et al. Citation2019), whereas the higher education context was often overlooked. To address this oversight, the current research applies social exchange theory and previous research results within the business context to assume that:

Hypothesis 1. HPWPs including (a) Ability, (b) Motivation, and (c) Opportunity significantly influence Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement.

The role of climate for engagement in the influences of HPWPs on job engagement

Climate for engagement

Climate for engagement is a specific facet of organizational climate, which is referred to as ‘the shared perceptions of organizational policies, practices, and procedures’ (Reichers and Schneider Citation1990, 22). Climate for engagement represents ‘employees’ shared perceptions about the energy and involvement willingly focused by employees toward the achievement of organizational goals’ (Albrecht Citation2014, 405).

Role of climate for engagement

Social exchange theory (Blau Citation1964) provides a justification for how HPWPs can lead to climate for engagement and job engagement. According to this theory, the utilization of Ability, Motivation, and Opportunity such as offering training, paying for performance, increasing job autonomy, and improving communication between employees and their organization, can create employees’ shared perceptions that the organization supports engagement in attaining its goals. When this supportive climate is formed, it will generate a sense of obligation encouraging employees to positively respond by boosting their job engagement (Bowen and Ostroff Citation2004). In university settings, as academic staff have traditionally enjoyed high levels of autonomy over their jobs, the generation of engagement climate that enhances academic staff’s job engagement is necessary to encourage academic staff to exert their autonomy for teaching and research instead of activities irrelevant to their jobs.

Despite the suggestion of social exchange theory about the potential link between HPWPs, climate for engagement and job engagement, there is a lack of research on the intervening role of climate for engagement, especially within the higher education context. Within the business context, some empirical studies (Chuang and Liao Citation2010; Kloutsiniotis and Mihail Citation2020) found that HPW system significantly affected various facet-specific climates. Other empirical studies identified direct connections between various facet-specific climates and engagement (Einarsen et al. Citation2018; Kang and Busser Citation2018). Based on social exchange theory and findings from earlier empirical research in the business context, this research suggests that:

Hypothesis 2. Climate for engagement mediates the influences of HPWPs, including (a) Ability, (b) Motivation, (c) and Opportunity, on Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement.

The influence of job engagement on job performance

Job performance

Job performance is a set of employee behaviors, which makes direct and indirect contributions to the achievement of organizational goals (Rich, Lepine, and Crawford Citation2010). Two kinds of job performance investigated in the current research are task performance and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Task performance relates to ‘the proficiency with which job incumbents perform activities that are formally recognized as part of their jobs … , activities that contribute to the organization’s technical core either directly by implementing a part of its technological process, or indirectly by providing it with needed materials or services’ (Borman and Motowidlo Citation1993, 73). OCB pertains to ‘performance that supports the social and psychological environment in which task performance takes place’ (Organ Citation1997, 95). According to Organ (Citation1997), OCB could be classified into seven dimensions: altruism (i.e. acting voluntarily to assist colleagues in tackling work-related issues), courtesy (i.e. behaving proactively to assist colleagues in avoiding work-related issues), conscientiousness (i.e. behaving well beyond the organization’s minimum requests), civic virtue (i.e. participating responsibly in the organization’s political life), sportsmanship (i.e. being tolerant of work-related inconveniences without complaining), peacekeeping (i.e. acting constructively to help prevent, resolve or reduce interpersonal conflicts), and cheerleading (i.e. encouraging actively colleagues’ professional development and achievements through words and actions). However, some preceding empirical studies (e.g. Bachrach, Bendoly, and Podsakoff Citation2001; Podsakoff and MacKenzie Citation1994) revealed that many respondents found it difficult to distinguish between altruism, courtesy, peacekeeping, and cheerleading. Therefore, this research agrees with Williams and Anderson (Citation1991) to categorize OCB into OCB for the sake of individuals (OCBI) and OCB for the sake of organization (OCBO).

Job engagement and job performance

The influence of employees’ job engagement on their job performance is not openly acknowledged in engagement theories, but there is theoretical evidence to justify this influence’s existence. According to Kahn (Citation1990), engaged employees are those devoting multiple personal resources to the performance of their jobs. This devotion will enable them to perform their job tasks more effectively and be more genuine at work. They will express their ideas, emotions, and convictions more openly and take part in activities beyond their job tasks that generate OCB such as willingly accepting orders without complaints, actively protecting the organizational property, enthusiastically participating in the life of their organizations, and constructively commenting on their organizations to outsiders. Therefore, engaged employees tend to produce high task performance and OCB.

The influences of engagement on task performance and OCB have been investigated by prior empirical studies within the business context (Alfes et al. Citation2013; Khan and Malik Citation2017; Ozyilmaz Citation2020; Rich, Lepine, and Crawford Citation2010). Meanwhile, research on these relationships within the higher education context is almost absent. To address this gap, the current research applies prior research results within the business context to hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3. Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement significantly influences their (a) task performance and (b) OCB.

Methods

A self-completion questionnaire survey was conducted to gather data within Ho Chi Minh City – the most populous national city and the most important economic hub in Vietnam with 40 public and 15 private universities and academies, accounting for 23% of the number of universities and academies in the country (Bộ Giáo dục và Đào tạo Citation2021). To access to these universities, an official agreement letter was obtained from the Ho Chi Minh City Representative Office of the Ministry of Education and Training. Following initial contact, the researcher arranged meetings with rectors, heads of HR or administration departments, and heads of schools or departments of public and private universities to present the research. Then, with support from the universities, the researcher met and invited full-time academic staff to participate in the survey. Respondents could either complete paper-based questionnaires and place them in the researcher’s lockable collection box or use online survey links, which were emailed to them to increase response rates.

To reduce common method variance (CMV), which is interpreted as ‘variance that is attributable to the measurement method rather than to the construct of interest’ (Bagozzi and Yi Citation1991, 426), the survey followed Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff (Citation2012)’s instructions and collected data from two distinct targets (i.e. Vietnamese university academic staff as followers and their line managers or supervisors as leaders) in two distinct phases. In Phase 1, multi-stage sampling was applied to select 14 public and private universities within Ho Chi Minh City based on their development history and academic programs’ diversity. From each selected university, academic staff from different schools and departments were invited to answer a questionnaire about their demographics, HPWPs, and their job engagement. Two to three weeks later, purposive sampling was used to acquire data from academic staff and their line managers or supervisors. In Phase 2, the academic staff who participated in Phase 1 were invited to answer a questionnaire about their demographics and climate for engagement. Their line managers or supervisors were invited to answer another questionnaire about their demographics, their subordinates’ task performance and OCB.

Among 416 questionnaires delivered in Phase 1, 402 follower questionnaires were obtained. Among 402 pairs of questionnaires distributed in Phase 2, 399 follower and 396 leader questionnaires were acquired. After data cleaning, the research sample encompassed 394 follower-leader dyads.

Sample characteristics

A data file was designed, including the data of demographics, HPWPs, climate for engagement, and job engagement obtained from the followers in two different phases and the data of task performance and OCB obtained from the leaders. In this data file, there were 394 academic staff participating in the survey, with 187 males (47.5%) and 207 females (52.5%). Among those, 301 respondents (76.4%) held master’s degrees or equivalent, whereas those having bachelor and doctoral degrees, or equivalent were 36 (9.1%) and 57 (14.5%) respondents, respectively. All the respondents were full-time lecturers (94.4%), senior lecturers (4.3%), teaching assistants (0.8%), and associate professors (0.5%) working at 125 departments and schools of 14 public and private universities within Ho Chi Minh City. Their average age was 35.19 years, ranging from 24 to 60 years. Their average university tenure (i.e. length of time employed in a university) was 7.39 years, ranging from 0.25 to 31 years. Their average job tenure (i.e. length of time employed in the present job role) was 5.72 years, ranging from 0.17 to 31 years. Their average dyadic tenure (i.e. length of time spent together between the followers and the leaders) was 3.46 years, ranging from 0.08 to 22 years ().

Table 2. Sample characteristics.

Measures

In this research, all the measurement instruments were adopted or adapted from previously validated scales to ensure the consistency of their reliability (See Appendix).

The HPWPs measurement instrument was developed from the Mostafa and Gould-Williams (Citation2014) scale with 27 items measuring three dimensions of Ability (i.e. selection, training and development), Motivation (i.e. performance-related pay, promotion, and job security), and Opportunity (i.e. job autonomy and communication). In this research, Ability, Motivation, and Opportunity were operationalized as three second-order formative constructs.

The job engagement measurement instrument was selected from the Rich, Lepine, and Crawford (Citation2010) scale with 18 items measuring three dimensions of physical engagement, emotional engagement, and cognitive engagement. In this research, job engagement was operationalized as a second-order reflective construct.

The climate for engagement measurement instrument was modified from the Albrecht (Citation2014) scale with six items. In this research, climate for engagement was operationalized as a single-order reflective construct at the school level, since it represents the academic staff’s general perception of policies, practices, and procedures performed in their school.

The task performance measurement instrument was adjusted from the Williams and Anderson (Citation1991) scale with seven items. In this research, task performance was operationalized as a single-order reflective construct.

The OCB measurement instrument was amended from the Williams and Anderson (Citation1991) scale with 13 items measuring two dimensions of OCBI and OCBO. In this research, OCB was operationalized as a second-order formative construct.

Six demographic variables, specifically age, gender, education, job tenure, university tenure, and dyadic tenure were controlled. These demographic variables were chosen because their effects on employees’ job engagement were demonstrated in earlier empirical studies such as Yang et al. (Citation2019).

Data analysis

SPSS version 24 and Mplus version 8 were used to analyze the individual-level and school-level constructs. Firstly, a comprehensive examination of the data was conducted to check missing data, outliers, and statistical assumptions about multivariate analysis and multilevel modeling. Subsequently, Harman’s single factor test was executed to diagnose the existence of CMV. Then, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and multilevel CFA (MCFA) were performed to validate the constructs’ measurement instruments. After validating the measurement instruments, the construct scores were calculated to analyze the associations between the constructs at multiple levels. Lastly, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c, 3a and 3b; multilevel SEM (MSEM) was utilized to examine Hypotheses 2a, 2b, and 2c.

Results

CMV test

Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff (Citation2012) stated that CMV could cause biasing impacts on the covariation between the constructs. Therefore, it is crucial to identify CMV early by using Harman’s single factor test. This test involves putting all variables into an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). If the EFA yields a single factor or a ‘general factor’, which comprises from 50% of the covariance in the independent and dependent variables, it confirms the existence of CMV (Podsakoff and Organ Citation1986). The test result showed that one general factor only elucidated 24.22% and did not constitute most of the covariance in the independent and dependent variables. It demonstrated that CMV did not exist, and thus the connections between the constructs were free from bias.

Measurement instrument validation

After assessing CMV, the validation process was conducted using CFA and MCFA to ensure the factorial validity, convergent validity, discriminant validity and composite reliability of all the measurement instruments. With respect to the factorial validity, the intraclass correlation coefficients of climate for engagement obtained from MCFA were all above the cut-off value of 0.05 (Julian Citation2001), ranging from 0.06–0.16. It signified that climate for engagement varied considerably between schools; hence, multilevel data analysis was necessary. The overall measurement model comprised seven constructs, namely Ability (two dimensions, 7 items), Motivation (three dimensions, 10 items), Opportunity (two dimensions, 7 items), job engagement (three dimensions, 16 items), climate for engagement (4 items), task performance (6 items), and OCB (two dimensions, 5 items). This measurement model exhibited a good fit for the data (Chi-Square χ2 (1359) = 1914.93, p < 0.01; Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.95, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.95, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.05, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.03), and all standardized factor loadings were high and significant, ranging from 0.53–0.91 (p < 0.01).

With respect to the convergent validity and discriminant validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) values of all the constructs were computed. Their square roots were compared with the correlation coefficients between the constructs, and these values are reported in .

Table 3. Intercorrelations, reliability, and validity.

As listed in , the AVE values were all greater than the threshold of 0.5 (Hair et al. Citation2014). The AVE square root values were all higher than the inter-construct correlation coefficients. The composite reliability values were all above the cut-off value of 0.7 (Hair et al. Citation2014). Given these results, it could be confirmed that all the constructs met the validity and reliability standards.

Hypothesis test

After the validation of measurement instruments, the construct scores were computed to facilitate the hypothesis testing process. SEM was conducted to test Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c, 3a, and 3b. The structural model completely fit the data (χ2 (20) = 52.8, p < 0.05; TLI = 0.92, CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.07), and the results are incorporated in .

Table 4. Direct relationships: HPW-practices, job engagement, task performance, and OCB.

As presented in , Ability (B = 0.17, p < 0.01) and Opportunity (B = 0.11, p < 0.01) had significant and positive influences on Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement. Besides, Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement had significant and positive influences on their task performance (B = 0.12, p < 0.1) and OCB (B = 0.28, p < 0.01). These results supported Hypotheses 1a, 1c, 3a, and 3b and rejected Hypothesis 1b. Concerning the control variables, the research found that gender (female dummy variable, B = −0.05, p < 0.1) and job tenure (B = −0.02, p < 0.01) of Vietnamese university academic staff were negatively and significantly associated with their job engagement. Contrarily, their age, education, university tenure, and dyadic tenure did not significantly affect their job engagement. Consequently, gender and job tenure of Vietnamese university academic staff continued to be controlled in the following multilevel mediation models to examine the indirect effects of three HPWPs dimensions on their job engagement through climate for engagement.

To test Hypotheses 2a, 2b, and 2c, MSEM was performed. The three multilevel mediation models achieved a perfect fit for the data, and the results are summarized in .

Table 5. Indirect relationships: HPW-practices, climate for engagement, and job engagement.

As reported in , there were significant and positive indirect effects of Ability (B = 0.13, p < 0.05; 90% confidence interval (CI): 0.02, 0.23) and Motivation (B = 0.09, p < 0.1; 90% CI: 0.01, 0.17) on Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement through climate for engagement. Furthermore, the links between Ability (B = 0.13, p = ns), Motivation (B = 0.09, p = ns), and Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement were no longer significant after including climate for engagement. Based on these results, it could be confirmed that climate for engagement was a full mediator in the influences of Ability and Motivation on job engagement of Vietnamese university academic staff. Conversely, Opportunity did not significantly affect Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement through climate for engagement. As a result, Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported, and Hypothesis 2c was rejected.

Discussion and conclusion

This research directly responds to the research calls of Karadas and Karatepe (Citation2019), Guest (Citation2011) and Dayarathna, Dowling, and Bartram (Citation2019) by examining the process from which HPWPs generate job performance in Vietnamese university settings and emphasizing the role of job engagement and climate for engagement within this process. The conceptual model was developed based on social exchange theory with three hypotheses illustrating the relationships between HPWPs, climate for engagement, job engagement, task performance, and OCB. The research results generally support the conceptual model and bring about significant theoretical, methodological, and practical implications as discussed below.

Theoretical implications

First, the research confirmed that HPWPs were the determinants of Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement. Among three HPWPs dimensions, Ability (i.e. selection, training and development) and Opportunity (i.e. job autonomy and communication) were identified to have significant and positive influences on Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement. These results agree with prior research results within the business context in China (Yang et al. Citation2019), India (Goyal and Patwardhan Citation2020), and the United Kingdom (Alfes et al. Citation2013). They advocate the arguments stemming from social exchange theory (Blau Citation1964) that HPWPs symbolize organizational resources, which lead employees to perceive that the organizations acknowledge the employees’ contributions and express concern about their well-being. These perceptions will oblige employees to positively respond by increasing their job engagement. The findings extend the comprehension of the cause-and-effect associations between HPWPs and job engagement by identifying which HPWPs dimensions better explain the variance in Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement. They help the researchers differentiate the effects of three HPWPs dimensions from those of a unidimensional HR system and individual HR practices. Although the research did not find a direct link between Motivation (i.e. performance-related pay, promotion, and job security) and job engagement, this result is understandable because some practices of Motivation might not be operated effectively in Vietnamese university settings (i.e. low salaries, a rigid and cumbersome academic promotion process). As reported by Harman and Le (Citation2010), the mean salary within the Vietnamese higher education sector is relatively low compared to that within other sectors. Remarkably, the mean salary in public universities is relatively low compared to that in private universities because public university academic staff are employed and managed following the Law on public employees. This low salary has led academic staff to look for additional jobs to supplement their income instead of focusing on improving the quality of their teaching and research (Silvera et al. Citation2014). Besides salary, the academic promotion process to associate professors and professors in Vietnam is complicated, involving the consideration and recognition of the university, interdisciplinary, and state councils. The establishment of eligibility criteria and selection of successful candidates for academic promotion are not determined by universities (Hội đồng Giáo sư Nhà nước Citation2022). As a result, academic staff may not have a sense of obligation to engage in their jobs to qualify for promotion. Thus, Vietnamese universities must address these challenges to strengthen academic staff’s job engagement.

Second, the research revealed that climate for engagement occupied a mediating role in the connections between Ability, Motivation and Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement. These findings advocate the notion resting on social exchange theory (Blau Citation1964) that when employees are provided with appropriate Ability and Motivation to achieve organizational goals, they will perceive a climate for engagement and thus become engaged in their jobs. Although the research did not find an indirect relationship between Opportunity, climate for engagement, and Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement, this result could be attributable to some limitations in Vietnamese university settings such as inadequate teaching and research infrastructure and insufficient foreign language and research skills among academic staff. Consequently, Vietnamese universities should take steps to address these limitations to enhance Opportunity, promote a work climate for engagement, and reinforce academic staff’s job engagement.

Third, the research identified that Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement significantly influenced their task performance and OCB. These findings are consistent with earlier research findings within the business context in Pakistan (Khan and Malik Citation2017), Turkey (Ozyilmaz Citation2020), the United Kingdom (Alfes et al. Citation2013), and the United States (Rich, Lepine, and Crawford Citation2010). As emphasized by Kahn (Citation1990), engaged employees are those who physically, emotionally, and cognitively employ and express themselves in the course of job performance. Their self-employment and self-expression will urge them to complete their job tasks and participate in activities beyond their job boundaries that represent OCB. Therefore, the higher level of job engagement employees have, the higher task performance and OCB they deliver. These findings are important because they enhance the comprehension of the cause-and-effect association between job engagement and job performance, specifically task performance and OCB.

Finally, the research expressed the viewpoint of Vietnamese university academic staff about the process from which three HPWPs dimensions strengthen their job performance. It added to research on the ‘black box’ problem by offering clear and persuasive evidence gathered from the higher education context of an Asian developing country such as Vietnam.

Methodological implications

The research operationalized Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff (Citation2012)’s instructions to measure the constructs from two distinct targets in two distinct phases. These techniques were proven to be effective in minimizing CMV through the Harman’s single factor test result. Their effectiveness will encourage future research to adopt similar techniques to enhance its findings’ quality.

Moreover, the research collected the data nested within schools and employed MCFA to evaluate the climate for engagement measurement model at the school level. In addition, it used MSEM to examine the multilevel mediation effects of HPWPs on Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement through climate for engagement. These advanced quantitative data analysis methods represent an improvement over previous HRM empirical studies. The way in which the MCFA and MSEM results were presented in the research will inspire future HRM research to adopt similar methods.

Practical implications

The research proposes that Vietnamese universities should apply HPWPs to foster academic staff’s job engagement. Among three HPWPs dimensions being used in Vietnamese universities, Ability (i.e. selection, training and development) and Opportunity (i.e. job autonomy and communication) should be continued and improved. In other words, to promote academic staff’s job engagement, Vietnamese universities should prioritize the recruitment and selection of individuals having the most suitable qualifications and competences for academic jobs. Once employed, academic staff should be given considerable autonomy for undertaking academic activities, ongoing training and development opportunities for improving job-related knowledge and skills, regular and accurate information and opportunities for communicating their feedback. Besides, Motivation (i.e. performance-related pay, promotion, and job security) currently applied in Vietnamese universities should be modified to positively influence academic staff’s job engagement, like the other two HPWPs dimensions. Specifically, Vietnamese universities should develop a pay policy that is clear, specific, transparent, open, fair and based on academic staff’s job performance. Since the mean salary within the Vietnamese higher education sector is relatively low (Harman and Le Citation2010), Vietnamese universities, especially the public ones, should seek to offer reasonable pay rates for academic staff to cover their living costs. Regarding promotion, Vietnamese universities should formulate a promotion policy that is clear, transparent, open, equitable and selects the appropriate individuals for the appropriate positions. Furthermore, Vietnamese universities should ensure job security for academic staff to alleviate any concerns they may have about their jobs. In short, the design, implementation, and improvement of HPWPs should meet the expectations of academic staff to maximize their beneficial effects.

In this research, climate for engagement was found to occupy a crucial role in linking HPWPs and Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement. Additionally, Vietnamese university academic staff’s job engagement was uncovered to be significantly and positively connected with their task performance and OCB. Given these findings and the fact that academic staff often have a high degree of autonomy in their jobs, Vietnamese university, school and department managers should focus on creating a work climate for engagement together with the adoption of HPWPs to foster academic staff’s job engagement and improve their job performance. Ultimately, this will aid Vietnamese universities in gaining enduring competitive advantages in the current global knowledge society.

Limitations and future research

Although the research provides theoretical, methodological, and practical contributions, it still has some limitations. Specifically, the research acquired data from Vietnamese university academic staff and their line managers or supervisors in two separate phases with an interval of two to three weeks. However, the brief interval between the two phases might impact the research’s ability to draw fixed conclusions. Hence, future research should apply a longitudinal quantitative method to verify the research model.

In addition, the research was undertaken at universities within Ho Chi Minh City – the most populous national city and the most important economic hub in Vietnam. Consequently, the generalization of the research findings might be restricted to the higher education context within this city and other national cities having similar attributes. For this reason, future research should extend the scope of its investigation to include universities in regional cities throughout Vietnam and other countries to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the research model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Albrecht, S. L. 2014. “A Climate for Engagement: Some Theory, Models, Measures, Research, and Practical Applications.” In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Climate and Culture, edited by B. Schneider, and K. M. Barbera, 400–14. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Alfes, K., C. Truss, E. C. Soane, C. Rees, and M. Gatenby. 2013. “The Relationship Between Line Manager Behavior, Perceived HRM Practices, and Individual Performance: Examining the Mediating Role of Engagement.” Human Resource Management 52 (6): 839–59. doi:10.1002/hrm.21512.

- Alqahtani, M., and D. T. Ayentimi. 2021. “The Devolvement of HR Practices in Saudi Arabian Public Universities: Exploring Tensions and Challenges.” Asia Pacific Management Review 26 (2): 86–94. doi:10.1016/j.apmrv.2020.08.005.

- Appelbaum, E. 2000. Manufacturing Advantage: Why High-Performance Work Systems Pay Off. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Armstrong, M. 2012. Armstrong's Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice. 12th ed. London: Kogan Page.

- Bachrach, D. G., E. Bendoly, and P. M. Podsakoff. 2001. “Attributions of the "Causes" of Group Performance as an Alternative Explanation of the Relationship Between Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Organizational Performance.” Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (6): 1285–93. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1285.

- Bagozzi, R. P., and Y. Yi. 1991. “Multitrait-Multimethod Matrices in Consumer Research.” Journal of Consumer Research 17 (4): 426–39. doi:10.1086/208568.

- Bộ Giáo dục và Đào tạo. 2021. “Thống kê Giáo dục Đại học” (Higher Education Statistics). Bộ Giáo dục và Đào tạo. Accessed Jan. 28, 2022. https://moet.gov.vn/thong-ke/Pages/thong-ko-giao-duc-dai-hoc.aspx.

- Blau, P. M. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Borman, W. C., and S. J. Motowidlo. 1993. “Expanding the Criterion Domain to Include Elements of Contextual Performance.” In Personnel Selection in Organizations, edited by N. Schmitt, and W. C. Borman, 71–98. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Bowen, D. E., and C. Ostroff. 2004. “Understanding HRM-Firm Performance Linkages: The Role of the “Strength” of the HRM System.” Academy of Management Review 29 (2): 203–21.

- Budd, J. W. 2011. The Thought of Work. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Central Intelligence Agency. 2022. “The World Factbook: Explore All Countries - Vietnam”. Central Intelligence Agency. Accessed Feb. 26, 2023. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/vietnam/.

- Christian, M. S., A. S. Garza, and J. E. Slaughter. 2011. “Work Engagement: A Quantitative Review and Test of Its Relations with Task and Contextual Performance.” Personnel Psychology 64 (1): 89–136. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x.

- Chuang, C. H., and H. Liao. 2010. “Strategic Human Resource Management in Service Context: Taking Care of Business by Taking Care of Employees and Customers.” Personnel Psychology 63 (1): 153–96. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2009.01165.x.

- Dayarathna, D. K., P. J. Dowling, and T. Bartram. 2019. “The Effect of High Performance Work System Strength on Organizational Effectiveness.” Review of International Business and Strategy 30 (1): 77–95. doi:10.1108/RIBS-06-2019-0085.

- Einarsen, S., A. Skogstad, E. Rørvik, ÅB Lande, and M. B. Nielsen. 2018. “Climate for Conflict Management, Exposure to Workplace Bullying and Work Engagement: A Moderated Mediation Analysis.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 29 (3): 549–70. doi:10.1080/09585192.2016.1164216.

- Gong, Y., S. Chang, and S. Y. Cheung. 2010. “High Performance Work System and Collective OCB: A Collective Social Exchange Perspective.” Human Resource Management Journal 20 (2): 119–37. doi:10.1111/j.1748-8583.2010.00123.x.

- Goyal, C., and M. Patwardhan. 2020. “Strengthening Work Engagement Through High-Performance Human Resource Practices.” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management.

- Guest, D. E. 2011. “Human Resource Management and Performance: Still Searching for Some Answers.” Human Resource Management Journal 21 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1748-8583.2010.00164.x.

- Hair, J. F., W. C. Black, B. J. Babin, and R. E. Anderson. 2014. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education.

- Harman, G., and T. B. N. Le. 2010. “The Research Role of Vietnam’s Universities.” In Reforming Higher Education in Vietnam: Challenges and Priorities, edited by G. Harman, M. Hayden, and T. N. Pham, 87–102. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hayden, M., and Q. T. Lam. 2010. “Vietnam’s Higher Education System.” In Reforming Higher Education in Vietnam: Challenges and Priorities, edited by G. Harman, M. Hayden, and T. N. Pham, 15–30. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hội đồng Giáo sư Nhà nước. 2022. “Văn bản quy Phạm Pháp Luật” (Regulatory Documents). Hội đồng Giáo sư Nhà nước. Accessed Oct. 28, 2022. http://hdgsnn.gov.vn/tin-van-ban-quy-pham-phap-luat_52.

- Jiang, K., D. P. Lepak, J. Hu, and J. C. Baer. 2012. “How Does Human Resource Management Influence Organizational Outcomes? A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Mediating Mechanisms.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (6): 1264–94. doi:10.5465/amj.2011.0088.

- Julian, M. W. 2001. “The Consequences of Ignoring Multilevel Data Structures in Nonhierarchical Covariance Modeling.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 8 (3): 325–52. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_1.

- Kahn, W. A. 1990. “Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work.” Academy of Management Journal 33 (4): 692–724. doi:10.2307/256287.

- Kang, H. J. A., and J. A. Busser. 2018. “Impact of Service Climate and Psychological Capital on Employee Engagement: The Role of Organizational Hierarchy.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 75: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.03.003.

- Kanungo, R. N. 1982. “Measurement of Job and Work Involvement.” Journal of Applied Psychology 67 (3): 341–9. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.67.3.341.

- Karadas, G., and O. M. Karatepe. 2019. “Unraveling the Black box.” Employee Relations 41 (1): 67–83. doi:10.1108/ER-04-2017-0084.

- Khan, M. N., and M. F. Malik. 2017. ““My Leader’s Group is my Group”. Leader-Member Exchange and Employees’ Behaviours.” European Business Review 29 (5): 551–71. doi:10.1108/EBR-01-2016-0013.

- Kloutsiniotis, P. V., and D. M. Mihail. 2020. “The Effects of High Performance Work Systems in Employees’ Service-Oriented OCB.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 90: 102610–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102610.

- Messersmith, J. G., K. Y. Kim, and P. C. Patel. 2018. “Pulling in Different Directions? Exploring the Relationship Between Vertical pay Dispersion and High-Performance Work Systems.” Human Resource Management 57 (1): 127–43. doi:10.1002/hrm.21846.

- Meyer, J. P., and N. J. Allen. 1991. “A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitment.” Human Resource Management Review 1 (1): 61–89. doi:10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z.

- Mohammadi, S., and P. Karupiah. 2020. “Quality of Work Life and Academic Staff Performance: A Comparative Study in Public and Private Universities in Malaysia.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (6): 1093–107. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1652808.

- Mostafa, A. M. S., and J. S. Gould-Williams. 2014. “Testing the Mediation Effect of Person-Organization Fit on the Relationship Between High Performance HR Practices and Employee Outcomes in the Egyptian Public Sector.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25 (2): 276–92. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.826917.

- Organ, D. W. 1997. “Organizational Citizenship Behavior: It’s Construct Clean-Up Time.” Human Performance 10 (2): 85–97. doi:10.1207/s15327043hup1002_2.

- Ozyilmaz, A. 2020. “Hope and Human Capital Enhance Job Engagement to Improve Workplace Outcomes.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 93 (1): 187–214. doi:10.1111/joop.12289.

- Podsakoff, P. M., and S. B. MacKenzie. 1994. “Organizational Citizenship Behaviors and Sales Unit Effectiveness.” Journal of Marketing Research 31 (3): 351–63. doi:10.1177/002224379403100303.

- Podsakoff, P. M., S. B. MacKenzie, and N. P. Podsakoff. 2012. “Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It.” Annual Review of Psychology 63 (1): 539–69. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452.

- Podsakoff, P. M., and D. W. Organ. 1986. “Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects.” Journal of Management 12 (4): 531–44. doi:10.1177/014920638601200408.

- Quacquarelli Symonds. 2022. “QS World University Rankings 2022”. QS Top Universities. Accessed Jan. 27, 2023. https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/world-university-rankings/2022.

- Reichers, A. E., and B. J. Schneider. 1990. “Climate and Culture: An Evolution of Constructs.” In In Organizational Climate and Culture, edited by B. Schneider, 5–39. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Rich, B. L., J. A. Lepine, and E. R. Crawford. 2010. “Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance.” Academy of Management Journal 53 (3): 617–35. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.51468988.

- Schaufeli, W. B., M. Salanova, V. Gonzalez-Romá, and A. B. Bakker. 2002. “The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Confirmative Analytic Approach.” Journal of Happiness Studies 3: 71–92. doi:10.1023/A:1015630930326.

- ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. 2022. “2022 Academic Ranking of World Universities”. Academic Ranking of World Universities. Accessed Jan. 27, 2023. https://www.shanghairanking.com/rankings/arwu/2022.

- Shuck, B., J. L. Adelson, and T. G. Reio Jr. 2017. “The Employee Engagement Scale: Initial Evidence for Construct Validity and Implications for Theory and Practice.” Human Resource Management 56 (6): 953–77. doi:10.1002/hrm.21811.

- Silvera, I. F., J. S. Angle, B. Hajek, J. E. Hopcroft, G. S. Rutherford, J. D. Semrau, V. Snoeyink, and N. V. Alfen. 2014. Higher Education Update: Observations on the Current Status of Higher Education in Agricultural Sciences, Civil Engineering, Computer Science, Electrical Engineering, Environmental Sciences, Physics, and Transport and Communications at Select Universities in Vietnam. Hanoi: Vietnam Education Foundation.

- Times Higher Education. 2022. “World University Rankings 2022”. Times Higher Education. Accessed Jan. 27, 2023. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2022/world-ranking.

- Torrington, D., L. Hall, S. Taylor, and C. Atkinson. 2009. Fundamentals of Human Resource Management: Managing People at Work. Harlow, England: Pearson Education.

- Weiss, H. M. 2002. “Deconstructing job Satisfaction.” Human Resource Management Review 12 (2): 173–94. doi:10.1016/S1053-4822(02)00045-1.

- Wiechetek, L., and Z. Pastuszak. 2022. “Academic Social Networks Metrics: An Effective Indicator for University Performance?” Scientometrics 127: 1381–1401. doi:10.1007/s11192-021-04258-6.

- Williams, L. J., and S. E. Anderson. 1991. “Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment as Predictors of Organizational Citizenship and In-Role Behaviors.” Journal of Management 17 (3): 601–17. doi:10.1177/014920639101700305.

- Yang, W., K. Nawakitphaitoon, W. Huang, B. Harney, P. J. Gollan, and C. Y. Xu. 2019. “Towards Better Work in China: Mapping the Relationships Between High-Performance Work Systems, Trade Unions, and Employee Well-Being.” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 57 (4): 553–76. doi:10.1111/1744-7941.12205.

Appendix

Measurement items of all constructs

HPWPs

My university’s hiring policy and process is fair.

Considerable importance is placed on the hiring process by my university.

Very extensive efforts are made by my university in the selection of new academic staff.

The university hires only the very best people for academic jobs.

My university offers opportunities for training and development.

In my opinion, the number of training programs provided for academics by my university is sufficient.

When my job involves new tasks, I am properly trained.

My university provides excellent opportunities for personal skills development.

Academic staff can be expected to stay with this university for as long as they wish.

Job security is almost guaranteed to academics in this university.

If the university was facing economic problems, academics would be the last to get downsized.

I am certain of keeping my job.

I have good opportunities of being promoted within this university.

The promotion process used by my university is fair for all academics.

Academics who desire promotion in this university have more than one potential position they could be promoted to.

Qualified academics have the opportunity to be promoted to positions of greater pay and/or responsibility within the university.

In my university, those who perform well in their jobs get better rewards than those who just meet the basic job requirements.

I have the opportunity to earn individual bonuses for my job performance.

My university tries to relate my pay to my job performance.

My pay raise is based on my job performance.

My university allows me to plan how I do my job.

My university allows me to make a lot of job decisions on my own.

My university allows me to decide on my own how to go about doing my job.

My university gives me considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do the job.

Management keeps me well informed of how well the university is doing.

The communication between me and other academics at work is good.

The communication between me and the managers/supervisors at work is good.

Academics in my university regularly receive formal communication regarding university goals and objectives.

Climate for engagement

Overall academics in this school strive to perform to the best of their ability.

Academics in this school are enthusiastic about their work.

Academics here really try to do a good job for the school.

Academics here are fully involved in their work.

Academics here are very positive about meeting school goals.

Academics here are willing to do their best to achieve the best possible outcomes for the school.

Job engagement

I work with intensity on my job.

I exert my full effort to my job.

I devote a lot of energy to my job.

I try my hardest to perform well on my job.

I strive as hard as I can to complete my job.

I exert a lot of energy on my job.

I am enthusiastic in my job.

I feel energetic at my job.

I am interested in my job.

I am proud of my job.

I feel positive about my job.

I am excited about my job.

At work, my mind is focused on my job.

At work, I pay a lot of attention to my job.

At work, I focus a great deal of attention on my job.

At work, I am absorbed by my job.

At work, I concentrate on my job.

At work, I devote a lot of attention to my job.

Task performance

I adequately complete assigned duties.

I fulfil responsibilities specified in job description.

I perform tasks that are expected of me.

I meet formal performance requirements of the job.

I engage in activities that will be directly related to my performance evaluation.

I neglect aspects of the job I am obligated to perform.

I fail to perform essential duties.

Organizational citizenship behavior

I help others who have been absent.

I help others who have heavy work load.

I assist supervisor with his/her work (when not asked).

I take time to listen to coworkers’ problems and worries.

I go out of my responsibilities to help new employees.

I take a personal interest in other employees.

I pass along information to coworkers.

My attendance at work is above the norm.

I give advance notice when unable to come to work.

I take undeserved work breaks.

I spent great deal of time with personal phone conversations.

I complain about insignificant things at work.

I conserve and protect university property.

I adhere to informal rules devised to maintain order.