ABSTRACT

Women have been underrepresented, and even excluded from academic life throughout history. As countries look to address ongoing inequality in academia, state-mandated gender quotas for academic boards and committees have emerged as a recommended practice in Europe. Although an increasing number of countries have adopted this policy model, little is known about its efficacy or consequences. Using country-level panel data from 25 European countries between 2003 and 2018, we explore the consequences of quotas on different measures of gender in/equality in academia. Findings indicate that quotas appear to achieve their intended direct effect of increasing the representation of women on academic boards, and this, in turn contributes to greater equality in academic staff and in senior professorship positions. Despite some concerns, there is little evidence that quotas incite a backlash.

Introduction

Women have been underrepresented, and even excluded from academic life throughout history (Barnard et al. Citation2022; Read and Kehm Citation2016). As countries look for tools to address this ongoing inequality, state-mandated gender quotas in academia have emerged as a recommended policy practice in Europe (European Commission Citation2018; González Ramos et al. Citation2020). Although an increasing number of European countries have adopted this policy model, little is known about the efficacy of academic quotas or their consequences (Voorspoels and Bleijenbergh Citation2019).

Quotas are intended to increase the number of women in public areas: politics, corporate boards and, recently, also in academia (Mansbridge Citation2005; Paxton, Hughes, and Painter Citation2010). In academic institutions they have emerged as a policy tool to maintain the alleged meritocracy of the academic system, while addressing sources of bias (Filandri and Pasqua Citation2021; Voorspoels and Bleijenbergh Citation2019). Academic quota legislation to date has targeted the committees of public universities, including governing boards, hiring committees and research funding committees. They are aimed at increasing the presence of women in decision-making positions, in order to exert an influence over academic life and research agendas, and to provide role models for other women (Bourabain and Verhaeghe Citation2022; European Commission Citation2009a).

Questions about the effectiveness of gender quotas in academia are highly relevant today (Filandri and Pasqua Citation2021; González Ramos et al. Citation2020). In 2018, a European Commission (EC) publication reported that while women constitute about half of PhD students, they make up less than a quarter of the most senior rank of university professors. Only 27% of academic board and committee members are women, and only 21.7% of heads of academic institutions are women (European Commission Citation2018).

While proponents of gender quotas assume that they advance gender equality, others challenge this assumption. Critics of quotas claim that they could incite a backlash, which may compromise the goals of gender equality. Quotas could encourage tokenism and delegitimize women leaders (Bourabain and Verhaeghe Citation2022; Dahlerup and Freidenvall Citation2005), prompt women to shy away from leadership positions for fear of being perceived as less qualified (Van den Brink and Benschop Citation2012), exacerbate existing gender biases (Bagues, Sylos-Labini, and Zinovyeva Citation2014; Clayton Citation2021; Deschamps Citation2018), and increase the burden of extra responsibilities placed on women in an effort to achieve diversity (Rodríguez, Campbell, and Pololi Citation2015).

Given the ongoing gender inequality in academia, as well as questions about the efficacy of gender quotas, it is important to examine the consequences of state-mandated academic quotas in this context. That said, very little is known about the consequences of quotas in academia. In addition, most existing studies are limited to a single country and timeframe (e.g. Bagues, Sylos-Labini, and Zinovyeva Citation2014; Bourabain and Verhaeghe Citation2022; Deschamps Citation2018; González Ramos et al. Citation2020). Thus, it is hard to draw conclusions about the potential and consequences of quota systems.

This study aims to remedy that lacuna by examining the consequences of state-mandated academic quotas on different measures of gender equality. Using constructed panel data from 25 European countries between 2003 and 2018, we investigate three potential types of consequences of quotas: direct intended consequences, indirect intended consequences, and unintended consequences. Specifically, we examine the correlation between state-mandated gender quotas in academic boards (our key independent variable) and gender equality in academia, as measured by (1) the percentage of women on academic boards (a direct intended consequence), (2) the percentage of women on academic staffs and (3) the percentage of women in senior (Grade A) professorship positions (#2 and #3 are indirect intended consequences). Finally, given the criticisms of quotas and their potential to incite a backlash, we test whether the implementation of quotas has unintended consequences. We examine this last possibility by comparing the relationship between women on academic boards and the other two measures of gender equality in contexts with and without state-mandated gender quotas.

Our findings contribute to a better understanding of the usefulness of state-mandated gender quotas in academia as a policy tool for increasing equality in European institutions of higher education and beyond. They show that quotas indeed increase the presence of women on academic boards, which, in turn, increases the presence of women in both the academic staff and in senior professorship positions. Overall, and contrary to some country-level case findings (Bagues, Sylos-Labini, and Zinovyeva Citation2014; Deschamps Citation2018), our findings do not consistently support the proposition that quotas incite a backlash. When intervening factors are controlled for, women’s representation on academic boards – whether or not achieved by means of quotas – appears to help increase the representation of women in the academic staff and in senior positions.

The purposes of quotas

Nations around the world implement different types of quota policies in order to remedy historical inequalities in representation, and overcome conscious and unconscious biases (González Ramos et al. Citation2020). They do so in the belief that women’s representation in leadership positions will have more widespread effects on policy (Wängnerud Citation2009), culture, and norms (Verge, Wiesehomeier, and Espírito-Santo Citation2020). Quota policies to date have been used to address inequality in legislatures, corporate boards, public administrative bodies, and academia. While legislative quotas are ubiquitous (Krook, Lovenduski, and Squires Citation2009), other types of quotas, such as academic quotas, have gained popularity only recently. Given the staggered emergence of these different types of quotas, their efficacy has been tested extensively in the political realm, and to some extent in the corporate sphere. However, very little is known about the usefulness and consequences of quotas in academia.

Quotas have multiple aims. Their intent is to increase the numerical representation of women, as well as ensure their substantive and symbolic representation (Baldez Citation2006). In the political and corporate realms, quotas have indeed proven very successful in increasing the percentage of women’s representation in legislatures and corporate boards (Mansbridge Citation2005; Paxton, Hughes, and Painter Citation2010). The expectation that quotas will promote gender equality beyond an increase in the numerical representation of women is based on the knowledge that having women leaders has both substantive and symbolic meaning (Dodson Citation2006; Storvik and Teigen Citation2010). As the number of women increases, thanks to the influence of quotas, so too does substantive and symbolic representation.

In politics, various studies have found that quotas indeed correlate with an increase in the substantive representation of women as the number of women in parliament increases. Women representatives, elected both with and without quotas, are more likely to promote women’s rights (Franceschet and Piscopo Citation2008) and childcare and family welfare (Schwindt-Bayer Citation2006). They also are more likely to help female constituents (Lowande, Ritche, and Lauterbach Citation2019; Parthasarathy, Rao, and Palaniswamy Citation2019). Symbolically, women politicians encourage higher levels of voting and political activity among women, as women begin to see politics less as a realm reserved for men (Beckwith Citation2007). Even within quota systems, the increased presence of women can reduce biases among voters and male legislators (Clayton Citation2021; Xydias Citation2014).

Studies of corporate quotas have yet to explore the substantive and symbolic outcomes of quotas per se, but evidence in general demonstrates a substantive impact of women’s leadership. In corporate settings, women leaders often build networks to help junior women and implement policies that promote more female-friendly work environments. In corporations, female leadership correlates with a breakdown in gender segregation and changes in gendered organizational culture (Davidson Citation2018; Terjesen, Sealy, and Singh Citation2009).

State-mandated quotas in academia

Within Europe, an increasing number of countries have begun to mandate quotas not only for corporate boards and legislatures, but also for academia and the public sector (EC Helsinki Group Citation2018). Today in the European Union, women make up the majority of students in higher education, and gender balance has largely been reached up to the PhD level. Nevertheless, among the academic staff, data have repeatedly shown a decrease in women’s representation with each career step (Cidlinská and Zilinčíková Citation2022; Ooms, Werker, and Hopp Citation2019; Vaughn, Taasoobshirazi, and Johnson Citation2020). As the number of qualified women increases over time (Monroe and Chiu Citation2010), implicit or explicit discrimination (Kim and Kim Citation2021; Mousa Citation2022) emerges as an explanation for this ‘leaky pipeline’ (Shaw and Stanton Citation2012).

All quota legislation to date targets the committees and boards of public universities. These quotas are applied to decision-making bodies such as scientific and administrative bodies, recruitment and promotion boards, and evaluation panels. The policies differ in regard to the organizational level to which the quotas are applied and in their enforcement mechanisms. While some countries have no means of enforcing quotas, other countries go so far as to mandate that if a university fails to meet the quota, the government can appoint board members (EC Helsinki Group Citation2018).

By making boards the target of quota policies, the policy is designed to advance gender equality in academia, while maintaining the meritocratic systems on which academia is purportedly based (González Ramos et al. Citation2020). Meritocratic principles allege that the unequal distribution of rewards is based on the skills, efforts, talents and achievements of individuals, rather than on social position or demographic characteristics. To ensure that achievements are based solely on talent and effort the system seeks to transparency and fairness, in which advancement is awarded to those most qualified, regardless of background or identity (Śliwa and Johansson Citation2014).

The meritocratic system in academia is managed in large part by academic boards and committees. These boards – including leadership boards, recruitment boards, and promotion boards – define the parameters of success, evaluate individuals’ merits (Widegren, Håkansson, and Jarneving Citation2022), and determine the conditions for recruitment, promotion, the awarding of prizes, and the distribution of resources (Marsh et al. Citation2009). Although academic boards are meant to function through formal procedures and enforce objective measures of meritocracy, in practice, informal networks find space in their activities (Hakiem Citation2023; Lipton Citation2017; Nielsen Citation2016).

Indeed, research has demonstrated that bias, non-transparency, and reliance on patriarchal networks for signals regarding policy recruitment influence these boards (Filandri and Pasqua Citation2021; Howe-Walsh and Turnbull Citation2016; Mijs Citation2016). In some instances, boards recreate and preserve cultural norms regarding gender roles and gendered power relations through their activities and decisions (Hakiem Citation2023; Kim and Kim Citation2021).

Furthermore, measures of merit (Lipton Citation2017) can be biased, especially if a board is demographically homogenous. When only a single group defines measures of success, there is likely a bias towards that group’s strong points (Uhlmann and Cohen Citation2005; Widegren, Håkansson, and Jarneving Citation2022). Therefore, a quota policy is designed to address these biases (European Commission Citation2009a).

There is no lack of scholarly and public debate about the usefulness of quotas in general, and in academia in particular. González Ramos et al. (Citation2020) reported that while quotas increase the number of women on boards, they do not remedy cultural and structural barriers to women’s advancement. Thus, there are fears that quotas will create a sense of tokenism of women, which can delegitimize women researchers and organization leaders (Bourabain and Verhaeghe Citation2022). Vernos (Citation2013) raised the concern that the extra work required to serve on these boards could be especially costly for women, as it would detract from their research time, adding more pressure to their conflict between family and career obligations. This burden of extra responsibilities placed on minorities to achieve diversity, termed the ‘minority tax,’ is a known outcome of diversity efforts (Rodríguez, Campbell, and Pololi Citation2015).

Another backlash might be the more negative treatment of the women who receive these leadership positions, as they might be regarded as less qualified (Dhawan, Belluigi, and Idahosa Citation2022; Weeks and Baldez Citation2015). It is a common concern in quota systems that affirmative action measures may result in the selection of less qualified people than those who would have otherwise filled the role (Allen, Cutts, and Campbell Citation2016; Holzer and Neumark Citation2000). For example, in France (Deschamps Citation2018) and Italy (Bagues, Sylos-Labini, and Zinovyeva Citation2014), when a quota policy was implemented, the presence of women on committees prompted the male evaluators to vote against female candidates. Indeed, Van den Brink and Benschop (Citation2012) found that women in academia sometimes decline positions reserved for them by quotas out of fear of being seen as an affirmative action case.

Moreover, women themselves might oppose the imposition of quotas for other reasons. For example, Willemsen and Sanders (Citation2007) reported that Dutch women professors preferred career development policies to quotas because of a concern about the stigmatization of women professors. This fear of stigmatization can prompt women in leadership roles to overcompensate in proving that they have the masculine characteristics associated with success (Derks, Van Laar, and Ellemers Citation2016). This outcome could potentially lead to the ‘queen bee’ phenomenon in which women who have achieved leadership positions in male-dominated environments seek to prevent the promotion or development of more junior women (Sobczak Citation2018). The queen bee phenomenon in academia (Ellemers et al. Citation2004; Gomes, Grangeiro, and Esnard Citation2022) could be exacerbated by women who feel a greater need to justify their status as leaders within a system of quotas (Bourabain and Verhaeghe Citation2022; Derks, Van Laar, and Ellemers Citation2016).

The potential for a backlash, as well as general questions of efficacy, highlight the need to better understand the impact of academic gender quotas on academic systems. Based on findings on political and corporate quotas, we may expect academic quotas to also have a positive system-wide effect on gender equality. However, the questions of whether and how they affect their target bodies, whether they have substantive and symbolic benefits for gender equality in academia, and whether they provoke a backlash have yet to undergo sufficient empirical examination.

Analytical reasoning, expectations, and research design

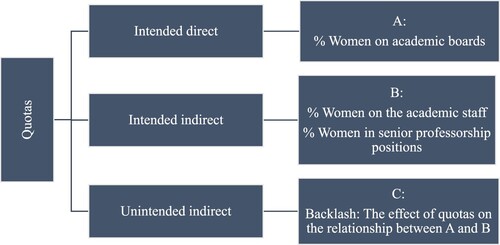

We posit that the potential effects of quotas can be conceptualized and measured in three ways. First are the direct intended consequences of quotas, measured as the expected increase in the percentage of women on academic boards. Second are the indirect intended consequences of quotas. Since an increase in the percentage of women on boards is expected to encourage equality elsewhere, we will assess the indirect intended consequences of quotas as an increase in the percentage of women elsewhere in academia mediated via the increase in the percentage of women on academic boards. Finally, there are the potential unintended consequences of quotas, measured as the unintended ways in which quotas incite a backlash that hurts gender equality. illustrates the three types of consequences that quotas may potentially have, as well as how these consequences will be measured.

The direct intended consequences of quotas are an increase in the percentage of women in the bodies that are specified within the policy, which in the case of academic quotas would be academic boards, including governing boards, hiring committees and research funding committees. Similar to legislative and corporate quotas that have proven effective in raising the number of women in their targeted bodies (Mansbridge Citation2005; Paxton, Hughes, and Painter Citation2010), we expect academic quotas to be successful in increasing the percentage of women in their targeted bodies.

The indirect intended consequences of quotas are an increase in gender equality in parts of the academic organization not directly targeted by the quota policy but result from the increase in women’s leadership. Findings from the field of politics indicate that with the implementation of quotas and the subsequent increase in women representatives, both substantive and symbolic representation improve (Clayton Citation2021; Franceschet and Piscopo Citation2008; Xydias Citation2014). A similar phenomenon has been documented in business, where a larger number of women correlates with substantive and symbolic outcomes (Davidson Citation2018; Terjesen, Sealy, and Singh Citation2009).

In the context of academia, the substantive and symbolic impacts of women leaders on boards should potentially promote an increase in the number of women in other parts of academic institutions. Substantively, the presence of women on boards could facilitate such an increase by eliminating gender biases in the meritocratic system. Women on boards could also change academic institutions substantively to benefit women by creating support and mentoring networks, advancing policies that promote gender equality, and addressing structural barriers to women’s professional advancement.

The indirect effect of quotas on gender equality in academia can also be facilitated through the symbolic impact of female leadership. The role model effect found both in politics and industry may also be relevant for academia. Research has established that women professors serve as role models, encouraging women to enter academia, specifically in academic fields where women’s underrepresentation is most severe (Bettinger and Long Citation2005). A work environment in which women are visibly present might also be more likely to be perceived as female-friendly and a place where women can succeed, further encouraging more women to join it.

Based on the potential substantive and symbolic impacts of female leadership, we expect quotas to have indirect effects on gender equality within academia beyond their targeted bodies, as they do in political and corporate settings. We measure these indirect outcomes using two main variables indicative of ongoing gender inequality: percent women on the academic staff, and within that population, percent women in senior professorship. We expect that with the imposition of quotas, and due to the subsequent increase in the percentage of women on boards, we will find an increased percentage of women on the academic staff and in senior professorship positions.

These variables, for which we have data over time and in various countries, are only two of many possible operationalizations of gender equality. However, they are often used as measures of gender equality and progress toward it in both government and academic studies (European Commission Citation2018; Winchester and Browning Citation2015). In addition, based on studies of political and corporate quotas, we know that women leaders can impact the percentage of women in organizations and in upper-level positions.

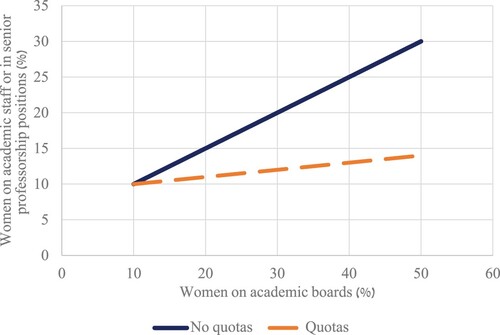

As noted above, quotas may incite a backlash against women and the goals of gender equality throughout organizations. If quotas do indeed provoke a backlash, then while they may raise the number of women on boards, the presence of these women will not correlate with the increase in gender equality elsewhere that we might expect. If indeed quotas contribute to increased bias among men, women, or both, then higher percentages of women on boards achieved without the implementation of quotas should be more effective in increasing the percentage of women on the academic staff and in senior professorship positions than when achieved with quotas. In other words, if quotas do indeed incite a backlash, we would expect the positive effect of women on boards on their representation in other academic positions to be stronger in the absence of quotas. depicts the expected relationship between women on academic boards and our outcome variables (women on the academic staff and in senior professorship positions) in quota and non-quota countries, if quotas do incite a backlash.

That said, studies on legislative quotas imply that the fear of a backlash is unfounded. Women elected through legislative quota policies exhibit similar behavior, agendas, and success in passing legislation as women who are not elected within a quota framework (Clayton and Zetterberg Citation2018; O’Brien and Rickne Citation2016). We therefore leave the expectation regarding the relationship between the percentage of women on academic boards and our two measures of gender equality (percentage of women on the staff and in senior professorship positions) open to empirical examination.

Methodology

Data

We used a cross-country comparison because the key independent variable we are tracking – quotas – is instituted and applied at the national level. Our data are limited to the European region, as the European Commission (EC) regularly collects and publishes data on gender equality in academia, and there are a fair number of European countries that have adopted academic gender quotas. We used panel data of 25 countries collected at regular intervals every three years between 2003 and 2018 by the European Commission. By limiting ourselves to the European region, we mitigate the chances of inconsistencies in data reporting.

Data on our main theoretical variables – women on academic boards, women on the academic staff, and women in senior professorship positions – came from the EC’s She Figures: Gender in Research and Innovation data collection projectn (European Commission, Citation2003, Citation2006, Citation2009b, Citation2012, Citation2015, Citation2018) . Data on quota legislation were collected from the 2018 EC Report Guidance to Facilitate the Implementation of Targets to Promote Gender Equality in Research and Innovation. This report does not always differentiate between state-mandated quotas and government recommended targets. In order to confirm which countries have state-mandated mandatory quotas, we verified our data using a number of other EC publications and sources, including the EC’s European Research Area National Action Plans (NAPs) and the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE)’s Database on Gender Equality in Academia and Research.Footnote1 Data for control variables for the size of the academic population relative to the population of a country came from two sources: the former from the She Figures reports and the latter from the World Bank (World Bank Citation2022). Finally, we also used The United Nations Gender Development Index (GDI) (Citation2019).

Out of the 25 countries in the dataset, 11 have gender quotas. Most of them were adopted in the last 15 years, the most recent quota being mandated in 2014 by Luxembourg. In a few isolated cases, notably in Scandinavia, academic gender quotas are decades old. Countries that mandated quotas after 2016, such as Germany, were coded as non-quota countries. As most of the dependent variables were from 2016-7, we assumed that this quota legislation would not yet have had an impact.

presents a list of all countries with quotas, including the legal framework that mandates quotas, the year mandated, the size of the quotas, and the level of enforcement. The list of countries without quotas, appears under the table. The quotas range from between a 33% to 50% quota, with most countries choosing a 40% quota. Some of the quotas are mandated specifically for academic institutions, while others are required as part of wider quota mandates for the committees and boards of all state institutions. The quota policies differ greatly in terms of enforcement mechanisms. Enforcement policies fall into one of four categories: no enforcement mechanisms, mandatory reporting but with no penalty for non-compliance, a financial penalty for non-compliance, or even the possibility of nullifying a board or a board’s decision in the case of non-compliance.

Table 1. Summary of countries with quotas and quota data.Table Footnotea

Variables

Our main independent variable is the presence of state-mandated gender quotas, a dichotomous variable, coded 1 for a year when a state-mandated quota was in place, and zero when the country had no quota policy legislated.

The dependent variables include two indicators of gender equality in academia, which serve as outcomes for the indirect consequences of quotas and their efficiency in promoting gender equality. These dependent variables are the percentage of women on the academic staff and the percentage of women in senior professorship positions. The former is the percentage of tenure and tenure-track research positions held by women in research institutions with PhD-conferring capabilities. The latter is the percentage of women in the highest rank of the academic staff within PhD-conferring institutions (‘Grade A’ the She Figures report). Women on academic boards serves as a dependent variable in our first analysis and as an intervening independent variable in later analyses. Academic boards include governing boards, hiring committees, and research funding committees.

Three control variables are included in all of the analyses. First, changes in the proportion of women academics in institutions may relate to the growth, plateauing, or consolidation of their presence in the higher education system. We therefore include a variable for the personnel in the higher education system, as a percentage of the total population (multiplied by one million). To control for overall gender equality and cultural norms of gender equality at the national level, we use the UN's GDI as an indicator of the overall gender inequality between countries (Ali and Dash Citation2023). The aim is to confirm that the percentage of women on the academic staff and in senior professorship positions is not just a function of overall levels of national gender equality. The GDI measures gender gaps between men and women using the dimensions of health, education, and standard of living (United Nations Development Programme Citation2019). The third control variable is the year of observation. Given that our data cover a period of time, we control for the year to eliminate the possibility that an increase in women’s representation is a function of increasing gender equality over time, unrelated to the quota policy.Footnote2

Method of analysis

Our unique panel dataset follows changes over time in different countries, allowing us to track variations both across countries and over time (i.e. between countries with and without quotas, as well as within a country before and after the implementation of quotas). Therefore, we used multilevel random intercept models, with each of the 25 surveyed countries nesting an average of 4.9 time points between 2003 and 2018 (a minimum interval of three years between time points).

The first model measured the direct intended consequences of the quotas. The dichotomous quota variable serves as the independent variable, and the percentage of women on academic boards as the dependent variable (A in ). We added controls for the size of the staff, the GDI, and the year, one after the other using fixed effect models.

In order to test the indirect intended consequences of quotas, meaning to identify the mechanisms by which quotas affect gender equality, we tested the effect of quotas on our two measures of gender equality in academia. We checked whether this effect is indeed mediated by the percentage of women on boards. The first series of models uses the percentage of women on the academic staff as the dependent variable, and the second uses the percentage of women in senior professorship positions (B in ). Both series include controls for the size of the staff, the GDI, and the year, which were added one after another.

The unintended consequences of quotas are examined by the interaction between the percentage of women on academic boards and quotas. These models test whether and how quotas affect the relationship between the percentage of women on academic boards (the expected outcome of the quotas) and our two measures of gender equality in academia – the percentage of women on academic staffs and the percentage of women in senior professorship positions (C in ). The interaction terms indicate whether the relationship between the percentage of women on academic boards and our other two measures of gender equality differ in contexts with and without state-mandated gender quotas. We reasoned that if quotas do provoke an unintended backlash, the positive effect of the percentage of women on academic boards on the two dimensions of gender equality in academia will be more pronounced if the goal of a higher percentage of women on academic boards is achieved without quotas. Put differently, in countries with quotas, having a higher percentage of women on academic boards will not improve other dimensions of gender equality as much as in countries without quotas. In both series we included controls for the size of the staff, the GDI, and the year, added one after the other.

Findings

We begin by observing the differences in the descriptive statistics for the percentage of women throughout academia for countries with and without quotas in a single year, the most recent year of observation. As indicates, quota countries lead in women’s presence in every indicator. They have an average of 40.4% of women on their academic boards – around 23% higher than in non-quota countries, with an average of 32.2%. The differences between the two groups are less pronounced with regard to the other outcome variables. Quota countries have 46.6% women on their academic staff, compared to 43.2% in non-quota countries, and 28% women in senior professorship positions, as compared to 25.1% in non-quota countries.

Table 2. Average percentage of women in quota versus non-quota countries (2018).

Our first models test the hypothesis that quotas achieve their intended goal of increasing the percentage of women on academic boards. Indeed, in all four models in , quotas significantly correlate with an increase in the percentage of women on academic boards. The quota coefficient drops only slightly with additional controls, but the decrease is more evident when variation over time is controlled. Thus, after controlling for time, the coefficient of the quotas in our full (fourth) model indicates that, holding all other things equal, in countries with academic quotas, the percentage of women on academic boards is almost 7% higher than in countries without quotas.

Table 3. Effects of quotas on the percentage of women on academic boards.

Our second and third sets of models test the hypothesis that quotas increase other dimensions of gender equality: the percentage of women on the academic staff and in senior professorship positions. displays the results for the former and for the latter. Both tables show very similar results. In both cases the coefficients on the quotas are positive and significant in Models 1-4, but lose their significance with the addition of the year (Model 5). These results imply that the growing gender equality in academia over time (indicated by our two measures) is also affected by other factors that enhance gender equality over time, beyond the implementation of quotas. Indeed, the significant coefficients of ‘year’ indicate that gender equality in academia increases over time above and beyond any possible effect of quotas or of the percentage of women on academic boards.

Table 4. Effect of quotas on the percentage of women on the academic staff.

Table 5. Effect of quotas on percentage of women in senior professorship positions.

That said, in both tables the coefficient of the quota shrinks significantly with the addition of ‘women on academic boards’ (its intended consequences), and the latter remains significant in all models. The differences in the magnitude of the quota’s coefficients in Model 1 and Model 2 in both tables mean that ‘women on academic boards’ mediates the effect of quotas on the two other dimensions of gender equality. The significant effect of ‘women on academic boards’ in Model 5 in both tables means that this outcome has its own distinct effect on the two gender equality outcomes above and beyond the other intervening variables, including ‘years.’ Furthermore, the insignificant effect of quotas in this model means that higher levels of ‘women on academic boards’ contribute to more equal gender representation in academia whether achieved by quotas or not.

Having established the positive effect of quotas on ‘women on academic boards’ and the positive effect of this variable on the other two outcomes, our last two sets of models test the potential unintended consequences of quotas. To recall, the logic on which this analysis is based is that if quotas do provoke an unintended backlash, then the positive effect of ‘women on academic boards’ on the other two dimensions of gender equality in academia should be more pronounced if a higher percentage of ‘women on academic boards’ is achieved without quotas.

In and we introduced an interaction term between ‘women on academic boards’ and quotas to test whether and how the effect of ‘women on academic boards’ on the percentages of women on the academic staff and in senior professorship positions (respectively) change in the presence of quotas. As the results in the tables indicate, the coefficients of ‘women on academic boards’ are positive and significant in all models in both tables, meaning that ‘women on academic boards’ significantly increases the percentage of ‘women on the academic staff’ () and ‘women in senior professorship positions’ () in countries without quotas. The negative and significant interaction terms in Models 1–3 in and in Model 1 in could indicate on a backlash, as they imply that in countries with quotas the positive effect of ‘women on the academic staff’ on our two outcomes is less pronounced relative to countries without quotas. However, these negative effects failed to maintain their significance in either table after we added the controls. In other words, we found no consistent proof of an unintended backlash of quotas on gender equality.

Table 6. Effect of quotas on the relationship between the percentage of women on academic boards and the percentage of women on the academic staff.Table Footnotea

Table 7. Effect of quotas on the relationship between the percentage of women on academic boards and the percentage of women in senior professorship positions.Table Footnotea

Discussion and conclusion

Academic quotas are a relatively new policy tool. Most European quotas policies were instituted only within the last 15 years. Though academic quotas aim to address longstanding inequalities between men and women, they have drawn criticism and aroused concern (Bourabain and Verhaeghe Citation2022; Van den Brink and Benschop Citation2012; Willemsen and Sanders Citation2007). The aim of this study was to explore the intended and unintended effects of quotas on a number of key measures of gender equality.

Based on the substantive and symbolic impacts that political and corporate quotas have had (Clayton Citation2021; Xydias Citation2014), we theorized that quotas could have three types of consequences: direct intended, indirect intended, and unintended. The direct intended consequence is an increase in the percentage of women on academic boards, as these are the bodies that quota policies directly target. Our findings imply that quotas do increase the percentage of women on academic boards. In countries with quotas the average percentage of women on academic boards is around 23% higher than in countries without quotas.

Having established that quotas increase the percentage of women on academic boards, we then examined the potential implications of this increase for two outcomes of gender equality: the expected increase in women on the academic staff and in senior professorship positions. Our theoretical framework asserted that as women’s presence in decision-making positions increases, there would be substantive and symbolic outcomes. Given that quotas increase the percentage of female leadership on boards, they could indirectly improve gender equality elsewhere.

Our findings support the expectations that quotas increase the percentage of women on the academic staff and in senior professorship positions. The differences between Models 1 and 2 of and in the magnitude of the quota coefficients indicate that female representation on academic board mediated the effect of quotas. Nevertheless, when adding controls for ‘year,’ the effect of quotas disappeared entirely. The positive effect of women on academic boards lost its magnitude but remained significant in all of the models. This result supports the assumption that greater representation of women on boards in academia – whether achieved by quotas or not – provides forms of representation that benefit other women (González Ramos et al. Citation2020).

The significant and strong effect of ‘year’ in all of the models implies that increases in gender equality in academia are also a function of time. Indeed, in most European countries the representation of women in institutions of higher education at all levels, from students to professors, has increased (European Commission Citation2018; Fritsch Citation2016). The strong effect of ‘year’ on the coefficients of the other two variables is important because it implies that the effect of quotas is mediated by the percentage of women on academic boards and by changes over time within countries. Thus, women’s presence on academic boards contributes to gender equality, whether this presence is achieved by quotas or other changes over time. It also may suggest that quotas as a policy have their intended effect for some years. However, as a study in politics reported, the effects of quotas may have a time limit after which they become less relevant (Su and Chen Citation2022).

While we might optimistically conclude that gender equality will improve over time with the growing representation of women in academia and senior positions within it even without policy interventions, it is not entirely clear what role quotas can play in speeding up the process. With the limited temporal data of our study, it is hard to provide an answer to this question. Most of the quota legislation is relatively new, whereas the progress of an academic career through promotions is a long process, especially promotion to senior professorship positions. This limitation creates a need for further examination to enhance the validity of our findings in order to better understand the efficacy and impact of quotas, as well as their validity over time.

Finally, the unintended consequences refer to the backlash against quotas. If quota policies exacerbate the bias against women or discourage them from pursuing leadership or senior positions, while such policies might increase the percentage of women on academic boards, they could discourage the advancement of women elsewhere. This backlash would be evident if higher percentages of women on academic boards achieved without quotas lead to more gender equality in academia than when these percentages are achieved by quotas. In other words, if the substantive and symbolic effects of the greater representation of women on academic boards result in a larger percentage of women on the academic staff and in senior professorships in countries without quotas than in countries with quotas, this outcome would indicate a backlash.

Our findings did not provide a consistent indication of a backlash, as the negative interaction terms in the models of both outcome variables lost significance with the addition of controls. Thus, while we were unable to examine specific backlash mechanisms with our data, we found no conclusive evidence of a general backlash. If quotas caused a ‘queen bee’ effect (Ellemers et al. Citation2004; Gomes, Grangeiro, and Esnard Citation2022), the tokenization or delegitimization of women leaders, or encouraged women to avoid supporting other women (Bourabain and Verhaeghe Citation2022; Derks, Van Laar, and Ellemers Citation2016) we would have anticipated the interaction between women on academic boards and our two outcome variables to be consistently and significantly stronger in non-quota countries relative to quotas countries.

Based on the inconsistent significance of the interaction, we conclude that the association between women on academic boards and out two outcomes is possibly no different in quota and non-quota systems. It is likely that women’s presence on academic boards contributes to gender equality, whether this presence is achieved through quotas, through alternative interventions, or naturally. However, based on the gap between quota and non-quota countries in the representation of women on academic boards in favor of the former (40.4% vs. 32.2%, respectively) and the importance of such representation, we conclude that policies aimed at increasing the representation of women on these boards, in this case, quotas, have the potential to increase gender equality.

This conclusion, however, should be taken with caution, as our data are based on a relatively small number of countries within a limited timeframe and a unique geographical and cultural context. These limitations create the need for further examination to enhance the validity of our conclusions. Are the findings regarding the absence of a backlash related to differences between the contexts or to the inability of our data to pick up on hard-to-detect backlash mechanisms? Further research is therefore needed to test specific backlash responses to quota policies more directly. For example, one possible backlash not picked up by our data might be the toll that the extra service on the academic board might have on women’s research time and research output, and thus their potential for advancement (Vernos Citation2013). Other possible backlashes would be an altered perception of women in board positions, in which they are viewed as less qualified (Dhawan, Belluigi, and Idahosa Citation2022) or the emergence of ‘queen bee’ behavior (Ellemers et al. Citation2004; Gomes, Grangeiro, and Esnard Citation2022).

In response to these possible backlashes, it is essential that state-mandated quotas come with clauses that prevent backlashes. For example, policies could be designed to avoid the tokenization of women on these boards by specifying key positions reserved for women that would put them in positions to challenge existing structures. Designing policies in such a way might ensure that women have meaningful and important roles rather than being treated as mere tokens or symbolic representations of diversity. In our study it was not possible to control for the positioning of female academics,Footnote3 but this information is important in order to understand how to implement a quota policy while preventing possible backlash. A better understanding of differences in policy design may also explain why the findings here differed from those found in single-country studies (e.g. Bagues, Sylos-Labini, and Zinovyeva Citation2014; Deschamp Citation2018).

Finally, while this study was limited to Europe, the gender gap in academia is a global phenomenon (Powell Citation2018). Therefore, an important next step might be to consider how these findings might have more global relevance. Assessing the relevancy of these findings might be important for determining the appropriateness of academic gender quotas in non-European contexts. Indeed, while this study was limited to Europe, South Korea has also already adopted a similar policy of academic quotas (Park Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Links to the EC’s European Research Area NAPs and the EIGE database appear in the references.

2 Initial models included a variable for the strictness of the quota policy to control for the effect of the enforcement policy on the quota’s efficacy. The variable was consistently insignificant, so we omitted it from the final models.

3 The EC began collecting data on this variable only in 2015. Therefore, the information was unavailable for most years of our study.

References

- Ali, Wajid, Ambiya, and Devi Prasad Dash. 2023. “Examining the Perspectives of Gender Development and Inequality: A Tale of Selected Asian Economies.” Administrative Sciences 13 (4): 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040115.

- Allen, Peter, David Cutts, and Rosie Campbell. 2016. “Measuring the Quality of Politicians Elected by Gender Quotas – Are They Any Different?” Political Studies 64 (1): 143–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12161.

- Bagues, Manuel, Mauro Sylos-Labini, and Natalia Zinovyeva. 2014. Do Gender Quotas Pass the Test? Evidence from Academic Evaluations in Italy. LEM Working Paper Series 2014/14, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna.

- Baldez, Lisa. 2006. “The Pros and Cons of Gender Quota Laws: What Happens When you Kick Men Out and Let Women in?” Politics & Gender 2 (1): 102–9.

- Barnard, Sarah, John Arnold, Sara Bosley, and Fehmidah Munir. 2022. “The Personal and Institutional Impacts of a Mass Participation Leadership Programme for Women Working in Higher Education: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (7): 1372–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1894117.

- Beckwith, Karen. 2007. “Numbers and Newness: The Descriptive and Substantive Representation of Women.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 40 (1): 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423907070059.

- Bettinger, Eric P., and Bridget Terry Long. 2005. “Do Faculty Serve as Role Models? The Impact of Instructor Gender on Female Students.” American Economic Review 95 (2): 152–7. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282805774670149.

- Bourabain, Dounia, and Pieter-Paul Verhaeghe. 2022. “Shiny on the Outside, Rotten on the Inside? Perceptions of Female Early Career Researchers on Diversity Policies in Higher Education Institutions.” Higher Education Policy 35 (2): 542–60. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-021-00226-0.

- Cidlinská, Kateřina, and Zuzana Zilinčíková. 2022. “Thinking about Leaving an Academic Career: Gender Differences Across Career Stages.” European Journal of Higher Education 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2022.2157854.

- Clayton, Amanda. 2021. “How do Electoral Gender Quotas Affect Policy?” Annual Review of Political Science 24 (1): 235–52. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102019.

- Clayton, Amanda, and Pär Zetterberg. 2018. “Quota Shocks: Electoral Gender Quotas and Government Spending Priorities Worldwide.” The Journal of Politics 80 (3): 916–32. https://doi.org/10.1086/697251.

- Dahlerup, Drude, and Lenita Freidenvall. 2005. “Quotas as a ‘Fast Track’ to Equal Representation for Women.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 7 (1): 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461674042000324673.

- Davidson, Sherwin. 2018. “Beyond Colleagues: Women Leaders and Work Relationships.” Advancing Women in Leadership Journal 38:1–13. https://doi.org/10.21423/awlj-v38.a339.

- Derks, Belle, Colette Van Laar, and Naomi Ellemers. 2016. “The Queen Bee Phenomenon: Why Women Leaders Distance themselves from Junior Women.” The Leadership Quarterly 27 (3): 456–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.12.007.

- Deschamps, Pierre. 2018. "Gender Quotas in Hiring Committees: A Boon or a Bane for Women?" LIEPP Working Paper 82.

- Dhawan, Nandita Banerjee, Dina Zoe Belluigi, and Grace Ese-Osa Idahosa. 2022. ““There is a Hell and Heaven Difference among Faculties who are from Quota and those who are Non-Quota”: Under the Veneer of the “New Middle Class” Production of Indian Public Universities.” Higher Education 1–26.

- Dodson, Debra L. 2006. The Impact of Women in Congress. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- EC Helsinki Group. 2018. Guidance to Facilitate the Implementation of Targets to Promote Gender Equality in Research and Innovation. Brussels: EC.

- Ellemers, Naomi, Henriette Van den Heuvel, Dick De Gilder, Anne Maass, and Alessandra Bonvini. 2004. “The Underrepresentation of Women in Science: Differential Commitment or the Queen bee Syndrome?” British Journal of Social Psychology 43 (3): 315–38. https://doi.org/10.1348/0144666042037999.

- European Commission. 2003. She Figures 2003. Brussels: EC.

- European Commission. 2006. She Figures 2006. Brussels: EC.

- European Commission. 2009a. Gender Challenge in Research Funding: Assessing the European National Scenes. Brussels: EC.

- European Commission. 2009b. She Figures 2009. Brussels: EC.

- European Commission. 2012. She Figures 2012. Brussels: EC.

- European Commission. 2015. She Figures 2015. Brussels: EC.

- European Commission. 2018. She Figures 2018. Brussels: EC.

- Filandri, Marianna, and Silvia Pasqua. 2021. “‘Being Good isn’t Good Enough’: Gender Discrimination in Italian Academia.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (8): 1533–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1693990.

- Franceschet, Susan, and Jennifer M. Piscopo. 2008. “Gender Quotas and Women’s Substantive Representation: Lessons from Argentina.” Politics & Gender 4 (3): 393–425.

- Fritsch, Nina-Sophie. 2016. “Patterns of Career Development and Their Role in the Advancement of Female Faculty at Austrian Universities: New Roads to Success?” Higher Education 72 (5): 619–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9967-6.

- Gomes, Manoel B., Rebeca R. Grangeiro, and Catherine Esnard. 2022. “Academic Women: A Study on the Queen Bee Phenomenon.” RAM Revista de Administração Mackenzie 23 (2): eRAMG220211.

- González Ramos, Ana M., Ester Conesa Carpintero, Olga Pons Peregort, and Marta Tura Solvas. 2020. “The Spanish Equality Law and the Gender Balance in the Evaluation Committees: An Opportunity for Women’s Promotion in Higher Education.” Higher Education Policy 33 (4): 815–833. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-018-0103-y.

- Hakiem, Rafif Abdul Aziz D. 2023. “‘I can’t Feel Like an Academic’: Gender Inequality in Saudi Arabia’s Higher Education System.” Higher Education 86: 541–561.

- Holzer, Harry J., and David Neumark. 2000. “What does Affirmative Action do?” ILR Review 53 (2): 240–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390005300204.

- Howe-Walsh, Liza, and Sarah Turnbull. 2016. “Barriers to Women Leaders in Academia: Tales from Science and Technology.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (3): 415–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.929102.

- Kim, Yangson, and SeungJung Kim. 2021. “Being an Academic: How Junior Female Academics in Korea Survive in the Neoliberal Context of a Patriarchal Society.” Higher Education 81:1311–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00613-3.

- Krook, Mona Lena, Joni Lovenduski, and Judith Squires. 2009. “Gender Quotas and Models of Political Citizenship.” British Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 781–803. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123409990123.

- Lipton, Briony. 2017. “Measures of Success: Cruel Optimism and the Paradox of Academic Women’s Participation in Australian Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 36 (3): 486–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1290053.

- Lowande, Kenneth, Melinda Ritche, and Erinn Lauterbach. 2019. “Descriptive and Substantive Representation in Congress: Evidence from 80,000 Congressional Inquiries.” American Journal of Political Science 63 (3): 644–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12443.

- Mansbridge, Jane. 2005. “Quota Problems: Combating the Dangers of Essentialism.” Politics & Gender 1 (4): 622.

- Marsh, Herbert W., Lutz Bornmann, Rüdiger Mutz, Hans-Dieter Daniel, and Alison O’Mara. 2009. “Gender Effects in the Peer Reviews of Grant Proposals: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Comparing Traditional and Multilevel Approaches.” Review of Educational Research 79 (3): 1290–326. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309334143.

- Mijs, Jonathan J. B. 2016. “The Unfulfillable Promise of Meritocracy: Three Lessons and their Implications for Justice in Education.” Social Justice Research 29 (1): 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-014-0228-0.

- Monroe, Kristen Renwick, and William F. Chiu. 2010. “Gender Equality in the Academy: The Pipeline Problem.” PS: Political Science & Politics 43 (2): 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909651000017X.

- Mousa, Mohamed. 2022. “Academia is Racist: Barriers Women Faculty Face in Academic Public Contexts.” Higher Education Quarterly 76 (4): 741–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12343.

- Nielsen, Mathias Wullum. 2016. “Limits to Meritocracy? Gender in Academic Recruitment and Promotion Processes.” Science and Public Policy 43 (3): 386–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scv052.

- O’Brien, Diana Z., and Johanna Rickne. 2016. “Gender Quotas and Women's Political Leadership.” American Political Science Review 110 (1): 112–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055415000611.

- Ooms, Ward, Claudia Werker, and Christian Hopp. 2019. “Moving up the Ladder: Heterogeneity Influencing Academic Careers through Research Orientation, Gender, and Mentors.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (7): 1268–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1434617.

- Park, Sanghee. 2020. “Seeking Changes in Ivory Towers: The Impact of Gender Quotas on Female Academics in Higher Education.” Women's Studies International Forum 79:102346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2020.102346.

- Parthasarathy, Ramya, Vijayendra Rao, and Nethra Palaniswamy. 2019. “Deliberative Democracy in an Unequal World: A Text-As-Data Study of South India’s Village Assemblies” American Political Science Review 113 (3): 623–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000182.

- Paxton, Pamela, Melanie M. Hughes, and Matthew A. Painter. 2010. “Growth in Women's Political Representation: A Longitudinal Exploration of Democracy, Electoral System and Gender Quotas.” European Journal of Political Research 49 (1): 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01886.x.

- Powell, Stina. 2018. “Gender Equality in Academia: Intentions and Consequences.” The International Journal of Diversity in Organizations, Communities, and Nations: Annual Review 18 (1): 19–35. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9532/CGP/v18i01/19-35.

- Read, Barbara, and Barbara M. Kehm. 2016. “Women as Leaders of Higher Education Institutions: A British–German Comparison.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (5): 815–827. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1147727.

- Rodríguez, José E., Kendall M. Campbell, and Linda H. Pololi. 2015. “Cross-comparison of MRCGP & MRCP(UK) in a Database Linkage Study of 2,284 Candidates Taking Both Examinations: Assessment of Validity and Differential Performance by Ethnicity.” BMC Medical Education 15 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-014-0281-2.

- Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie A. 2006. “Still Supermadres? Gender and the Policy Priorities of Latin American Legislators.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 570–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00202.x.

- Shaw, Allison K., and Daniel E. Stanton. 2012. “Leaks in the Pipeline: Separating Demographic Inertia from Ongoing Gender Differences in Academia.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279 (1743): 3736–41. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0822.

- Śliwa, Martyna, and Marjana Johansson. 2014. “The Discourse of Meritocracy Contested/Reproduced: Foreign Women Academics in UK Business Schools.” Organization 21 (6): 821–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508413486850.

- Sobczak, Anna. 2018. “The Queen Bee Syndrome. The Paradox of Women Discrimination on the Labour Market.” Journal of Gender and Power 9 (1): 51–61. https://doi.org/10.14746/jgp.2018.9.005.

- Storvik, Aagoth, and Mari Teigen. 2010. Women on Board: The Norwegian Experience. Berlin: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Su, Xuhong, and Wenbo Chen. 2022. “Pathways to Women’s Electoral Representation: The Global Effectiveness of Legislative Gender Quotas Over Time.” The Journal of Legislative Studies 1–22.

- Terjesen, Siri, Ruth Sealy, and Val Singh. 2009. “Women Directors on Corporate Boards: A Review and Research Agenda.” Corporate Governance: An International Review 17 (3): 320–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00742.x.

- Uhlmann, Eric Luis, and Geoffrey L. Cohen. 2005. “Constructed Criteria” Psychological Science 16 (6): 474–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01559.x.

- United Nations Development Programme. 2019. “Gender Development Index (GDI).” United Nations Human Development Reports. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/gender-development-index-gdi.

- Van den Brink, Marieke, and Yvonne Benschop. 2012. “Slaying the Seven-Headed Dragon: The Quest for Gender Change in Academia.” Gender, Work & Organization 19 (1): 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2011.00566.x.

- Vaughn, Ashley R., Gita Taasoobshirazi, and Marcus L. Johnson. 2020. “Impostor Phenomenon and Motivation: Women in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (4): 780–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1568976.

- Verge, Tània, Nina Wiesehomeier, and Ana Espírito-Santo. 2020. “Framing Symbolic Representation: Exploring How Women’s Political Presence Shapes Citizens’ Political Attitudes.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 3 (2): 257–76. https://doi.org/10.1332/251510819X15698538164156.

- Vernos, I. 2013. “Quotas are Questionable.” Nature 495 (7439): 39. https://doi.org/10.1038/495039a.

- Voorspoels, Jolien, and Inge Bleijenbergh. 2019. “Implementing Gender Quotas in Academia: A Practice Lens.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 38 (4): 447–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-12-2017-0281.

- Wängnerud, Lena. 2009. “Women in Parliaments: Descriptive and Substantive Representation.” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (1): 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053106.123839.

- Weeks, Ana Catalano, and Lisa Baldez. 2015. “Quotas and Qualifications: The Impact of Gender Quota Laws on the Qualifications of Legislators in the Italian Parliament.” European Political Science Review 7(1): 119–44. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773914000095.

- Widegren, Kajsa, Susanna Young Håkansson, and Bo Jarneving. 2022. “Gender, Cognitive Closeness and Situated Assessments in Academic Recruitment.” European Journal of Higher Education 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2022.2138487.

- Willemsen, Tineke, and Karin Sanders. 2007. “Vrouwelijke hoogleraren in Nederland: loopbaanervaringen en meningen over beleidsmaatregelen.” Tijdschrift voor hoger onderwijs 25 (4): 235–44.

- Winchester, Hilary P. M., and Lynette Browning. 2015. “Gender Equality in Academia: A Critical Reflection.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 37 (3): 269–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2015.1034427.

- World Bank. 2022. “Population, Total.” World Bank Data Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.

- Xydias, Christina. 2014. “Women's Rights in Germany: Generations and Gender Quotas.” Politics & Gender 10 (1): 4–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X13000524.