ABSTRACT

The employee-organisation relationship between academics and universities is a critical issue in higher education (HE) human resource management. Previous studies have mainly investigated the segmentation between full-time and part-time academics, or academics working in different countries. However, few studies have explored academics’ perceptions of their relationship with universities under the recent tenure-track reform in the Chinese HE system. Drawing on psychological contract theory, this qualitative study explores how academics perceive their relationships with their university. Through interviews with 21 tenure-track academics at a Chinese university, this study found four types of psychological relationships: (1) high-risk with high-yield, (2) optimistic trust, (3) mutual benefit, and (4) content and satisfied. Among the four types, tenure-track academics’ expectations of universities are diversified. These findings suggest that universities should pay more attention to understanding academics’ perceived employee-organisation relationship and their corresponding expectations to improve managerial efficiency.

Introduction

Employees are crucial in an organisation given their extraordinary role in preparing and developing the organisation (Davidescu et al. Citation2020). This means organisations need to understand the key factors that influence employee performance and conduct proper management strategies to improve human resource management (HRM) efficiency. Employee-organisation relationship (EOR) is significantly associated with such pivotal factors as employees’ job satisfaction, affective commitment, turnover intention, perception of fairness and perception of work options, and impacts employees’ production (Koh and Yer Citation2000; Rakotoarizaka, Qamari, and Nuryakin Citation2022). Since the 1990s, the study of EOR has become an integral part of the organisational literature to provide both private and public organisations with a theoretical foundation in understanding employees’ perceptions of the reciprocal rights and responsibilities between themselves and their respective organisations (Mir, Mir, and Mosca Citation2002; Ribeiro-Soriano and Urbano Citation2010). As such, effective HRM practices may be pursued.

Notably, under the influence of globalisation, internationalisation, and neoliberalism in the global higher education context, universities also need to improve their HRM practices to fully leverage academics’ teaching and research productivity. Against this background, a thriving body of research has begun to study the academic-university relationship, namely the EOR in the higher education field, to help universities improve their HRM practices (Chan Citation2021; Mousa Citation2020). However, few studies have explored the EOR as perceived by tenure-track academics. Inspired by managerialist ideas of efficiency, monitoring, and control, some countries (e.g. China, Japan, Germany, Finland, and Pakistan) have begun to successively introduce a tenure-track system (S. Dance Citation2016; Herbert and Tienari Citation2013; Khan and Jabeen Citation2019; Kuwamura Citation2009; Wang and Jones Citation2021). Institutions in these countries first offer fixed-term contracts (e.g. five or six years) to academics and step-by-step promotion (usually along the hierarchy of assistant professorship, associate professorship, and full professorship) until the final, conditional stage of academic tenure (Pietilä Citation2017). An increasing number of universities in these countries face the challenge of effectively managing academics employed through such a new recruitment system. Therefore, it is essential to understand the relationship between universities and tenure-track academics. This study focuses on tenure-track academics and explores the EOR between them and their universities. A research question is proposed to guide this exploration: How do tenure-track academics perceive their relationships with the university?

Employment relationship between academics and universities

The employment relationship, also known as EOR, is considered by Barnard (Citation1938) and March and Simon (Citation1958) to be an exchange relationship between employees and organisations. The theoretical premise is based on the exchange of contributions that the organisation expects employees to provide and the investments that the organisation makes in the employees. Existing studies have sought to analyse this relationship through two perspectives: the employer’s perspective on the employment relationship, and the employees’ perceptions of the reciprocal obligations towards their employer (Koh and Yer Citation2000). Concerning EOR in the higher education context, researchers mainly take the latter perspective, namely academics’ perceptions – to explore the types, factors, and influences of EOR between academics and their affiliated universities.

A substantial body of studies have utilised psychological contract theory to identify patterns of EOR perceived by academics in certain universities and further summarised the relationship types alongside their heterogeneity (e.g. Chan Citation2021; Krivokapic-Skoko and O’Neill Citation2008; Ruokolainen et al. Citation2018; Shen Citation2010; Tipples, Krivokapic-Skoko, and O'Neill Citation2007). Among these studies, quantitative methods are often employed through large-scale data collection to provide a systematic examination of potential relationships. For example, based on the data collected in 2008, 2009, and 2010 from a Finnish university, Ruokolainen et al. (Citation2018) investigated 1,197 academics’ perspectives on their employment relationship with the university and proposed six different types of EOR: strong and balanced, average and balanced, employer-focused, employee-focused, balanced transactional, and employee-focused relational. Specifically, the patterns called strong and balanced, employer-focused and employee-focused are characterised by ‘mutual high obligations’, ‘employee under-obligations’ and ‘employee over-obligations’ respectively. The pattern labelled balanced transactional emphasises transformational obligations on the part of both employees and employers. In addition to the aforementioned four types, two patterns specifically existing in knowledge-based organisations (like universities) named employee-focused relational and average and balanced were revealed. In detail, the former pattern is featured as academics feel more responsible for taking care of their well-being and informing the employer about their interests, and the latter indicates a higher score in obligations but not as the strong and balanced pattern. Regarding the heterogeneity of the academic-university relationship, researchers appear to prefer a qualitative approach. For example, through semi-structured interviews with 20 Australian and 30 Malaysian university academics, Chan (Citation2021) found that Australian academics’ contracts were primarily transactional which are based on direct and explicit expectations, focusing on tit-for-tat economic transactions, while Malaysian academics’ contracts were primarily relational that are built on trust and implicit emotional attachment and often long-term and have some degree of flexibility between individuals and the organisation. Furthermore, using the psychological contract theory, Shen’s (Citation2010) survey of 280 academic staff in a middle-rank Australian university identified the heterogeneous perceptions of EOR among academics working in the same country under different contracts.

The factors impacting the academic-university relationship have also been explored. It has been found that academics’ perceived EOR may be influenced by organisational behaviours, such as resource investment and management practices by the university (Harris et al. Citation2023; Herbert and Tienari Citation2013; Mousa Citation2020; Nikunen Citation2012). Drawing on interviews with 26 contract researchers working in the U.S., UK, and Australia, Harris et al. (Citation2023) found that, unlike full-time faculties who often perceive themselves as core members, these part-time researchers feel marginalised because universities are more willing to invest resources in supporting long-term academics rather than short-term academics. In addition, faculties’ individual characteristics, such as age, position, and employment status, have been proven to have a pivotal impact on their psychological contracts (Shen Citation2010).

Such differences in academics’ perceived EOR will further generate various approaches towards the reciprocal rights and responsibilities between themselves and their universities. These individualised psychological approaches may not only impact their work performance (Rakotoarizaka, Qamari, and Nuryakin Citation2022) but also their job satisfaction, and further impact their retention or departure choices (Hammouri et al. Citation2022; Lam and de Campos Citation2015; O'Meara, Bennett, and Neihaus Citation2016). Understanding the various academics’ perceptions of EOR would thus help universities implement different HRM strategies.

In summary, a thriving body of work has studied the academic-university relationship from the academics’ perspective. However, existing studies have failed to explore the relationship perceived by tenure-track academics with their universities. The different types of employment relationships are also under-researched due to a prevalent research preference for quantitative methods. Therefore, this study adopts a qualitative method to explore how Chinese tenure-track academics view their EOR with the university. As mentioned previously, Chinese higher education institutions (HEIs) are currently in the stage of exploring and improving the tenure-track system, and the EOR between academics and universities appears to be relatively complex, which provides a novel context to analyse the diversity of tenure-track academics’ perceived EOR. Correspondingly, a Chinese university has been selected as the research site, and relevant context is briefly introduced below.

Reform of personnel management policy in Chinese HEIs

Under the pressure of global competition, the Chinese government began to assign personnel management authority to HEIs so that they could recruit and manage faculties in accordance with their needs for institutional development (Cai Citation2010; L. Wang and Mok Citation2013). In China, many HEIs chose to introduce the tenure-track system to break the ‘Bian Zhi’ (similar to permanent contract in the public sector; Wang and Jones Citation2021). Since Peking University and Tsinghua University pioneered this system in 2003, about 35% of high-level research universities have completed tenure-track reform, and 50% are in the process of this reform (Zhang Citation2021).

Although the tenure-track is an academic career system originated in the U.S., its adoption and modification are currently at an early stage, as educational systems vary considerably between countries and universities (Pietilä Citation2017). In China, the tenure-track system implemented by HEIs is quite similar to that of the U.S., known as the ‘publish or perish’ (which is also regarded as ‘up-or-out’ in some universities) practice, meaning that if academics cannot fulfil the requirements for promotion during their probationary period, their contracts may not be renewed. Different from American universities’ promotion mechanism focusing more on academic performance than quota, China’s academic promotion features a low promotion rate limited by the old system known as fixed ‘bianzhi’ and ‘dual system’ where the old employment system and the new tenure system co-exist (Yang, Cai, and Li Citation2023).

The reform of personnel management policy has also diversified the traditional employment relationships between academics and universities in China. In contrast to the past personnel management system providing lifetime job security for most academics (Si Citation2022), the current ‘dual system’ determines that only academics who have passed the review during a timed contract (usually five or six years) could sign permanent contracts with universities; otherwise, they will be employed as short-term staff. Against this backdrop, universities have incorporated specific provisions into contracts to delineate the mutual rights and responsibilities of both parties and implemented differentiated management of various types of academics. Nonetheless, contractual provisions prove to be inadequate for universities managing academics’ daily conduct. The reason lies in the fact that tenure is a relatively new concept in China, universities are uncertain about the types and levels of assistance and support required, nor the roles and responsibilities of academics. Consequently, employment contracts feature ambiguous provisions that lack clarity concerning the mutual rights and responsibilities of academics and the universities. The lack of clarity in this matter further stimulates academics to devise specific approaches to their work based on their individualised comprehension of the contract. Such perceptions and interpretations, as academics’ cognitive production, are implicit and difficult for university administrators to capture, thereby creating challenges in implementing timely and effective management responses.

Theoretical lens: psychological contract

This study adopts the psychological contract theory as a framework to analyse the EOR between academics and universities in the Chinese context. Psychological contract mainly focuses on the relationship between employees and their organisations from the perspective of psychology rather than law. It emphasises the implicit, informal, and undisclosed mutual expectations between employees and organisations (Argyris Citation1960, 96; Levinson et al. Citation1962, 33; Schein and Schein Citation1970). These implicit expectations include employees’ expectations for salary, status, and promotion opportunities as well as the organisation’s expectations for loyalty and work engagement from employees. The key to fulfilling psychological expectations between organisations and their members is the social exchange mechanism based on the principle of reciprocity (Robinson, Matthew, and Denise Citation1994). According to the dimensions of economic and social exchange, some studies in relevant literature have proposed two typologies of the employee-organisation dynamic: transactional versus relational (Macneil Citation1985; D.M. Rousseau Citation1990; Shore and Tetrick Citation1994). Based on the above types, D. Rousseau (Citation1995) further argued that the employment time and performance requirements should be taken into consideration in contemporary organisations, and proposed four types of psychological contract between organisations and employees, including transactional (short-term/explicit performance requirements), transitional (short-term/vague performance requirements), balanced (long-term/explicit performance requirements), and relational (long-term/vague performance requirements) (Hui, Lee, and Rousseau Citation2004; D.M. Rousseau and Tijoriwala Citation1998).

As indicated by psychological contract theory, there are also implicit expectations between academics and universities, especially with the gradual infiltration of neoliberalism into the global HE field. While academics hope to obtain long-term employment and other job security such as promotion, work autonomy, and recognition of their talents and skills (Shen Citation2010), universities use assessment and performance management to convey expectations for higher performance and more time investment from academics (Dabos and Rousseau Citation2004). Accordingly, some scholars have adopted the psychological contract theory to analyse the academic-university relationship in the United States, Egypt, and European countries (Heffernan and Heffernan Citation2018; Mousa Citation2020; Tipples, Krivokapic-Skoko, and O'Neill Citation2007). Moreover, within the tenure-track system in China, academics can be differentiated based on their employment duration and performance requirements. For example, pre-tenured academics usually face clear performance requirements in the contract and tenured academics may not have clear performance requirements. This differentiation sheds light on analysing the EOR in the field of HEIs through the theoretical lens of psychological contract.

Research design

This study adopted an exploratory qualitative approach to analyse the perceived psychological contract between academics and universities in the Chinese HE sub-field. Qualitative research focuses on analysing the constructed social reality of actors and is concerned with actors’ subjective perspectives (Hollstein Citation2011). It allows in-depth exploration of the particular, rather than generalisable, knowledge of a teacher’s beliefs within certain contexts (Munby Citation1984), which aligns closely with the focus of this study on academics' perception in understanding EOR relationships. Thus, this study conducted qualitative research to explore the psychological understanding of EOR through academics’ personal stories and the interactions between researchers and participants.

Using a purposive sampling approach, we chose one Chinese university (University A hereafter) as a research case since it implemented the reform of the tenure-track system in recent years. Drawing on the experience of tenure-track reforms of Tsinghua University and Peking University, University A has been implementing the tenure-track system on a large scale since 2016. This means University A has a diverse group of tenure-track academics with varying lengths of employment, which facilitates further exploration of the various characteristics that may exist within the psychological contract relationships of the academic cohort. Similar to most Chinese universities, University A also requires academics to participate in tenure review and be promoted to associate professors within a 6-year short-term employment period to obtain tenure – a prevalent practice in the Chinese context. Furthermore, this university delegated the management of academics to their departments, where the protocols and procedures of tenure reviews lack coherent clarity from one another. For example, some departments listed relatively clear employment review goals and made the tenure review policy publicly available to all faculty members, while others did not have specific quantitative requirements (such as numbers of high-quality publications) for tenure review. Therefore, academics in University A have varying perceptions of the clarity of review and whether they could obtain long-term employment, which provides a vivid scenario for this study.

After obtaining information from the official websites of the universities, including details from the individual profiles of faculties, we sending the invitation emails through the researchers’ email contacts. After that, 21 academics under the tenure-track system voluntarily participated in this study to share their views (see ). The participants’ employment duration at the current department varied from one year to ten years. 15 were pre-tenure academics and 6 were tenured academics. Their names were anonymised to protect privacy.

Table 1. Participants’ demographic information.

This study conducted semi-structured interviews lasting 60 to 70 minutes with academics from 2021 to 2022, aiming to explore their perceptions of the contractual relationship between them and their university. Ethical approval was provided by the first author’s university prior to the data collection. The interview questions mainly included two guide-covered aspects: (1) participants’ perceived EOR and expectations from the perspective of employment time and the clarity of performance, and (2) how they understand the type of psychological contracts to which they belong. For those who have converted to tenured academics, this study further asked about whether their perceived EOR changed over time and, if so, what changes have occurred. The collected data were transcribed and translated from Chinese to English, and then a re-check with the participants was conducted to ensure the accuracy of meanings. Then, research team members conducted cross-checks to further verify the authenticity of the interviews.

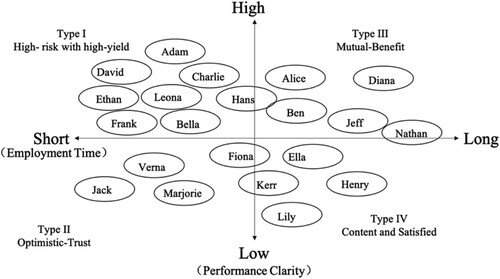

Data were analysed using both inductive and deductive approaches. First, we deductively analysed data from the psychological contract perspective to categorise the potential types of relationships. We divided participants into four categories based on their employment time and perceived clarity of performance evaluation in a 2 × 2 logic: (1) long-term and clarified, (2) long-term and unclear, (3) short-term and clarified, and (4) short-term and unclear. Meanwhile, based on Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) thematic method, we inductively identified key themes related to participants’ views on their relationships with the university and potential expectations, including the characteristics of different types of participants as well as their positive/negative attitudes towards tenure-track management. At this stage, the coding generated eight sub-themes, including the relationships between rights and obligations, resource inputs, performance output requirements, long-term/short-term employment, the degree of equality in both parties’ positions, academic autonomy, positive/negative emotional perceptions, and attitude changes. On this basis, four types of psychological contracts were identified with the considering of time and the level of performance clarity: (1) high-risk with high yield (Type I), (2) optimistic-trust (Type II), (3) mutual-benefit (Type III), and (4) content-satisfied (Type IV). To present the findings, we selected representative quotations to illustrate their views with thick and rich descriptions.

Findings

Based on psychological contract theory, this study identified four typologies of the participants’ perceived EOR (), which sufficiently captured their different perceptions of EOR as well as their different expectations for the university. It should be noted that some participants’ perspectives can simultaneously fall into several typologies based on their changing perceptions of EOR. For example, academics, when newly hired and not yet pass tenure review, may tend to categorise themselves as high-risk with high return type. After obtaining long-term employment, they may adjust this perceived EOR to a mutually beneficial type characterised by a relatively equal balance of rights and obligations. Thus, the analysis did not distinguish the theoretical boundaries between the typologies, which were mainly used to guide the research questions and inform the participants about the types of psychological contract they were more inclined to associate with. The purpose was to better reveal the typical characteristics of psychological contracts within each type, whilst the intersection between types were also considered.

Overall, the participants who had obtained tenure belonged to types III and IV (3/6) or at the intersection of the two types (3/6), while the participants who had not yet obtained tenure were mostly categorised in types I and II (10/15). In this section, the key findings are illustrated in the four key themes identified through the coding and analysis.

Type I high-risk with high-yield

Participants belonging to this type mostly have short-term employment contracts (except Hans), and the HEI has clear performance requirements for their work content during this period. They believed that the relationship between themselves and the university was an exchange relationship in which they faced a greater risk of being eliminated and at the same time had the opportunity to obtain more guarantees (e.g. long-term employment). The high returns from obtaining job security attract academics to form this kind of relatively temporary relationship with the university. Hans used a vivid metaphor for this contract:

In reality, HEIs are more like employers to improve research output and machines for supervising the work progress of faculty members to promote academic production. As short-term contract faculties, the connection between academics and organisations is not very close. What academics have to do is to meet the assessment requirements, and HEIs provide guarantees for academics accordingly.

My university has mainly adopted the logic of rewarding achievements. If young faculty cannot bring corresponding benefits to the university, there would be no support for them, akin to an engineering management approach. Moreover, most universities have now formed the idea of pushing faculty, rather than helping, to increase organizational performance. In this approach, the university rewards those who perform well, while those who do not may receive no rewards.

Type II optimistic-trust

Similar to Type I, participants belonging to this type hold short-term employment contracts, but there is no clear performance requirement of them from HEIs. They believed that the relationship between themselves and the university was a friendly relationship of trust, while no clear agreement or standards were formed on how to obtain tenure and promotion. For example, Verna said that she was unsure how high the bar was for promotion.

When I first joined the university, it did not issue tenure evaluation documents for faculty members. At the beginning of our employment, the contract we signed with the university stated a pre-tenured period of five years, during which we needed to meet a certain bottom line for teaching, research, and service work. However, the contract contained only one sentence at the end, stating that we should be promoted to associate professors during the pre-tenured period to obtain long-term employment. There was no clear explanation at the time on how to be promoted to associate professors.

As Henry said: ‘Although I haven’t got tenure yet, my department regards me as one of them, and the university probably would not indeed eliminate me’. Coupled with the influence of harmony in Confucian culture (Lau et al. Citation2021), some participants (for example Henry, Jack, and Fiona) maintained an optimistic attitude that the university would provide them with the security of long-term employment, even if they did not meet the explicit performance appraisal requirement. Kerr, who has experienced the transformation of the faculty management system, was representative of this type of contract. He shared his experience after entering university in 2014:

The Human Resources Department of my university mentioned some assessment requirements during the conversation. However, the contract I signed did not explicitly state “up-or-out” (i.e. promotion or termination). Thus, I did not pay much attention to this at the beginning of my career. Furthermore, based on my observation of the previous faculty, my college had an unwritten rule that the tenure review of short-term academics’ was just a formality (走过场), most faculty could pass the review.

Type III mutual-benefit

Participants belonging to this type are either tenured faculty members or those who are highly likely to obtain long-term employment (such as Alice and Ben) on condition of clear performance requirements. They normally regard themselves as core members of the university and have mutually beneficial relationships with the university. That is, the university provides them with more rights (e.g. job security, academic freedom, and development opportunities), and they work hard for the university accordingly. As Diana said, she no longer needs to worry about being eliminated after obtaining tenure, which means ‘the recognition and acceptance from the university’. The long-term employment commitment of HIEs has brought academics a high sense of job security and also helped to improve the job satisfaction of organisational members (Dobrow, Ganzach, and Liu Citation2018). Similar to Diana, Jeff and Nathan further mentioned the new expectations after resolving the pressure to survive. Nathan summarized the expectations as follows:

The first one is promotion opportunities. For academics, it seems unacceptable that some universities do not provide promotion indicators for tenure. The second one is developmental opportunities for academics to show their talent and engage in academic activities. The third one is more academic and time freedom, which means that HEIs should release a task burden that is irrelevant to academics.

HEIs are a strong backbone for academics and should provide as much support as possible and reduce interference, which means that management should not be used as a substitute for support. For example, if HEIs want academics to apply for more high-level research funding, they should also provide appropriate training and invest more corresponding resources to help academics improve the quality of their research proposals rather than rigid management.

Type IV content and satisfied

Participants of this type have a relatively satisfactory relationship with the university. They stated that through their efforts, they could establish a long-term employment relationship with universities, although their perceptions of performance requirements were vague. Therefore, participants of this type were mostly satisfied with their relationships with universities. Based on satisfaction with the working conditions provided by the university, participants highlighted the expectations of professional guidance and academic freedom. Fiona declared:

Overall, my university is willing to support the development of young faculty in many ways, from applying for the National Social Science Fund of China to publishing journal articles. Regardless of the results, at least my University has done a lot of coordination work in supporting our development, with multiple departments such as the Personnel Department, the Academic Department of Social Sciences, and the International Exchange and Cooperation Department working together to organise these activities, which make me satisfied with the contractual relationship with the university.

Compared with academics in the pre-tenured stage, I may be more laid back now. I am very satisfied that I can conduct research according to individual research interests without worrying about being kicked out. As such, compared to professional support, I expect my university to let me do what I am interested in, even if there is no academic output in the short term.

Discussion

Drawing upon psychological contract theory, this qualitative study explored tenure-track academics’ perceptions of their employee-organisation relationship with their universities in China. This study found four types of perceived EOR, including two types of short-term employment (type I and type II) and two types of long-term employment (type III and type IV). The expectations of academics of different types in terms of rights and responsibilities are illustrated separately. As the years of employment increase, academics’ perceptions of the psychological contract relationship between them and the universities may also change and adjust.

Based on the findings, this study makes several theoretical and practical contributions. First, it contributes to the existing literature by clarifying the psychological characteristics of diversity within academics and their unwritten expectations. Compared to studies that have focused on part-time academics (Castellacci and Viñas-Bardolet Citation2021) and the differences in organisational expectations between part-time and full-time academics (Harris et al. Citation2023), this study highlighted the differentiation within the full-time faculty group and discussed the expectations of different subgroups separately, as this latter aspect has not been fully explored in previous studies. Second, based on D. Rousseau’s (Citation1995) division of psychological contract types from the dimension of employment time, this study further proposes an analytical approach to classify the types of psychological contracts from academics’ perceived employment length to better fit the sub-field of Chinese HEIs. Specifically, unlike Guillaume and Apodaca (Citation2022), who argued that passing long-term assessments means academic freedom and job security, this study found that Chinese academics’ perceived employment length is not the same as the commitment time of HEIs. For example, although some participants have already passed the tenure review, they still exhibited characteristics similar to those of Type I and Type II participants, which illustrates a high level of job insecurity. One possible reason is that they believe that HEIs may also reform the tenure-track system in the future, requiring tenured academics to participate in the ‘publish or perish’ competition, which is quite different from American universities (Yang, Cai, and Li Citation2023). Third, for policymakers and university administrators, this qualitative study also makes a practical contribution to personnel management by clarifying the unspoken expectations of different academics, which helps the HEIs build a harmonious EOR by meeting the different expectations of academics. The findings in the Chinese context could also be useful for other countries’ HEIs, such as Japan, Germany, Finland, and Pakistan, which hope to improve the vitality of academics through the reform of the personnel management system.

For participants belonging to type I, this study found that some of them exhibited the characteristics of part-time academics, such as unstable employment hours and clear performance tasks, which was also in line with Herbert and Tienari’s (Citation2013) findings that academics hired on a short-term basis may regard themselves as outsiders rather than core members of the organisation. Against the background of an increasing number of academics adopting fixed-term contracts, job security has become an important topic (Kinman and Johnson Citation2019). It should also be noted that the findings supported earlier research by Wang and Jones (Citation2021) which argued that the implementation of a tenure-track system has increased the pressure of research output on academics rather than academic freedom and job security, the high risk of elimination also increases academics’ expectations for the harvest of long-term employment guarantee.

Unlike type I, which emphasises the risk of being fired, participants belonging to type II have a more positive view of the stable relationship with their organisation. As Ortlieb and Weiss (Citation2018) argued, the sense of job insecurity is influenced by subjective evaluations of whether pre-tenured academics can obtain tenure. This further affects academics’ perceptions of the length of employment and psychological contracts. The findings illustrated that this type of academics showed low levels of job insecurity, although some of them had not yet passed the tenure review. Only when positive expectations are not met in the department, academics would be frustrated, lost, and even feel betrayed (Huston, Marie, and Ambrose Citation2007).

As for Type III, tenure-track academics consider the EOR between them and the university from the perspective of equal rights and obligations. Similar to the findings of Ruokolainen et al. (Citation2018) in a Finnish university, this study found that academics’ perspectives about their relationship with the university are complex and revealed the characteristics of balance and relation. Because university administrators are more willing to support full-time faculty development (Harris et al. Citation2023), participants belonging to this category also have high expectations for HEI to provide them with professional training, promotion opportunities, and more leisure time. Correspondingly, they would invest more time and effort in teaching and research activities under the requirements of the university.

Although they regard themselves as long-term academics, like type III academics, type IV academics have significantly lower expectations for the university. Owing to unclear performance appraisal requirements, they carry out scientific research activities in accordance with individual research interests and internal motivation. However, unlike the findings of Tang and Chang (Citation2010) from employees in companies, this study indicated that the ambiguity of performance requirements did not harm the creativity of academics of this type. One possible reason is that faculty often formulate their own development goals based on the standards of disciplines rather than the needs of their institutions (Harley, Muller-Camen, and Collin Citation2004), so academics may not need HEIs to provide a clear division of roles and task requirements.

Conclusion

Under the pressure of global competition, it is important for HEIs to understand the changing employment relationship between them and academics to improve HRM efficiency. Based on psychological contract theory, this study subsequently explores the psychological expectations of academics at the micro level and finds that they have different perceived EOR. Based on their employment time and performance clarity, academics have four different psychological contracts in the context of China: (1) high risk with high yield, (2) optimistic trust, (3) mutual benefit, and (4) contented and satisfied, revealing their unwritten expectations. Considering the fierce competition in the academic labour market, this study highlights the impact of HEI personnel reform on academics’ perceived EOR and corresponding expectations in the context of increasing competition and tenure review pressure in China, which provides Chinese experience for understanding the EOR in HEIs, especially the impact of cancelling long-term employment on academics’ exits (Strunk, Barrett, and Lincove Citation2017).

Admittedly, this study only analysed the perceived EOR of academics in one Chinese university, while universities at different levels differ greatly in terms of governance culture and organisational behaviour in China and other countries (such as the U.S. which has implemented the tenure-track system for a long time). Further research could conduct comparative analysis across organisations or across borders to reveal the organisational or cultural differences in academics’ psychological contracts. Furthermore, this study found that, in general, the more clear the tenure/performance goal that academics perceived, the more likely they were to be Type I and Type III. The tendency exhibited by academics may suggest their perspectives on the equitable relationship between rights and obligations with the organisation have a more profound impact on their perception of EOR and professional activities. Although this study did not conduct a specific confirmatory analysis, it is valuable to explore the in-depth relationship between tenure/performance goal clarity and psychological contracts through quantitative research with a lagre sample size in future study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Argyris, Chris. 1960. Understanding Organizational Behavior. Homewood, Ill.: Dorsey Press.

- Barnard, Chester I. 1938. The Functions of the Executive. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Cai, Yuzhuo. 2010. “Global Isomorphism and Governance Reform in Chinese Higher Education.” Tertiary Education and Management 16 (3): 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2010.497391.

- Castellacci, Fulvio, and Clara Viñas-Bardolet. 2021. “Permanent Contracts and Job Satisfaction in Academia: Evidence from European Countries.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (9): 1866–1880. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1711041.

- Chan, Shirley. 2021. “The Interplay between Relational and Transactional Psychological Contracts and Burnout and Engagement.” Asia Pacific Management Review 26 (1): 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2020.06.004.

- Dabos, Guillermo E, and Denise M Rousseau. 2004. “Mutuality and Reciprocity in the Psychological Contracts of Employees and Employers.” Journal of Applied Psychology 89 (1): 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.52.

- Dance, Amber. 2016. “University Jobs: Germany to Fund Tenure-Track Posts.” Nature 535 (7610): 190–190. https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7610-190a.

- Davidescu, Adriana AnaMaria, Simona-Andreea Apostu, Andreea Paul, and Ionut Casuneanu. 2020. “Work Flexibility, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance among Romanian Employees—Implications for Sustainable Human Resource Management.” Sustainability 12 (15): 6086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156086.

- Dobrow, Shoshana R, Yoav Ganzach, and Yihao Liu. 2018. “Time and Job Satisfaction: A Longitudinal Study of the Differential Roles of Age and Tenure.” Journal of Management 44 (7): 2558–2579. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315624962.

- Garcia, Patrick Raymund James M, Rajiv K Amarnani, Prashant Bordia, and Simon Lloyd D Restubog. 2021. “When Support is Unwanted: The Role of Psychological Contract Type and Perceived Organizational Support in Predicting Bridge Employment Intentions.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 125:103525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103525.

- Guillaume, Rene O, and Elizabeth C Apodaca. 2022. “Early Career Faculty of Color and Promotion and Tenure: The Intersection of Advancement in the Academy and Cultural Taxation.” Race Ethnicity and Education 25 (4): 546–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1718084.

- Hammouri, Qais, Asmahan Majed Altaher, Ahmad Rabaa’i, Heba Khataybeh, and Jassim Ahmad Al-Gasawneh. 2022. “Influence of Psychological Contract Fulfillment on Job Outcomes: A Case of the Academic Sphere in Jordan.” Problems and Perspectives in Management 20 (3): 62–71. https://doi.org/10.21511/ppm.20(3).2022.05.

- Harley, Sandra, Michael Muller-Camen, and Audrey Collin. 2004. “From Academic Communities to Managed Organisations: The Implications for Academic Careers in UK and German Universities.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 64 (2): 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2002.09.003.

- Harris, Jess, Kathleen Smithers, Nerida Spina, and Troy Heffernan. 2023. “Disrupting Dominant Discourses of the Other: Examining Experiences of Contract Researchers in the Academy.” Studies in Higher Education 48 (1): 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2105831.

- Hart, David W., and Jeffery A. Thompson. 2007. “Untangling Employee Loyalty: A Psychological Contract Perspective.” Business Ethics Quarterly 17 (2): 297–323. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq200717233.

- Heffernan, Troy A., and Amanda Heffernan. 2018. “The Academic Exodus: The Role of Institutional Support in Academics Leaving Universities and the Academy.” Professional Development in Education 45 (1): 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2018.1474491.

- Herbert, Anne, and Janne Tienari. 2013. “Transplanting Tenure and the (Re) Construction of Academic Freedoms.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (2): 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.569707.

- Hollstein, Betina. 2011. “Qualitative Approaches.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis, 404–416.

- Hui, Chun, Cynthia Lee, and Denise M. Rousseau. 2004. “Psychological Contract and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in China: Investigating Generalizability and Instrumentality.” Journal of Applied Psychology 89 (2): 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.2.311.

- Huston, Therese A., Norman Marie, and Susan Ambrose. 2007. “Expanding the Discussion of Faculty Vitality to Include Productive But Disengaged Senior Faculty.” The Journal of Higher Education 78 (5): 493–522. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2007.0034.

- Khan, Tayyeb Ali, and Nasira Jabeen. 2019. “Higher Education Reforms and Tenure Track in Pakistan: Perspectives of Leadership of Regulatory Agencies.” Bulletin of Education and Research 41 (2): 181–205.

- Kinman, Gail, and Sheena Johnson. 2019. “Special Section on Well-being in Academic Employees.” International Journal of Stress Management 26 (2): 159–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000131.

- Koh, William L, and Lay Keow Yer. 2000. “The Impact of the Employee-organization Relationship on Temporary Employees’ Performance and Attitude: Testing a Singaporean Sample.” International Journal of Human Resource Management 11 (2): 366–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/095851900339918.

- Krivokapic-Skoko, O'Neill. 2008. “University Academics’ Psychological Contracts in Australia: A Mixed Method Research Approach.” Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6 (1): 61–72.

- Kuwamura, Akira. 2009. “The Challenges of Increasing Capacity and Diversity in Japanese Higher Education Through Proactive Recruitment Strategies.” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (2): 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315308331102.

- Lam, Alice, and André de Campos. 2015. “‘Content to be Sad’or ‘Runaway Apprentice’? The Psychological Contract and Career Agency of Young Scientists in the Entrepreneurial University.” Human Relations 68 (5): 811–841. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726714545483.

- Lau, Wai Kwan, Lam D Nguyen, Loan NT Pham, and Daniel A Cernas-Ortiz. 2021. “The Mediating Role of Harmony in Effective Leadership in China: From a Confucianism Perspective.” Asia Pacific Business Review 29: 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2021.1948216.

- Levinson, Harry, Charlton R. Price, Kenneth J. Munden, Harold J. Mandl, and Charles M. Solley. 1962. Men, Management, and Mental Health. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Macneil, Ian R. 1985. “Relational Contract: What We do and do not Know.” Wisconsin Law Review : 483–525.

- March, James G., and Herbert A. Simon. 1958. Organizations. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Mir, Ali, Raza Mir, and Joseph B. Mosca. 2002. “The New Age Employee: An Exploration of Changing Employee-organization Relations.” Public Personnel Management 31 (2): 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102600203100205.

- Mousa, Mohamed. 2020. “Organizational Inclusion and Academics’ Psychological Contract: Can Responsible Leadership Mediate the Relationship?” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 39 (2): 126–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-01-2019-0014.

- Munby, Hugh. 1984. “A Qualitative Approach to the Study of a Teacher's Beliefs.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 21 (1): 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660210104.

- Nikunen, Minna. 2012. “Changing University Work, Freedom, Flexibility and Family.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (6): 713–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.542453.

- O'Meara, KerryAnn, Jessica Chalk Bennett, and Elizabeth Neihaus. 2016. “Left Unsaid: The Role of Work Expectations and Psychological Contracts in Faculty Careers and Departure.” The Review of Higher Education 39 (2): 269–297. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2016.0007.

- Ortlieb, Renate, and Silvana Weiss. 2018. “What Makes Academic Careers Less Insecure? The Role of Individual-level Antecedents.” Higher Education 76 (4): 571–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0226-x.

- Pietilä, M. 2017. “Incentivising Academics: Experiences and Expectations of the Tenure Track in Finland.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (6): 932–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1405250.

- Rakotoarizaka, Nandrianina Louis Pierre, Ika Nurul Qamari, and Nuryakin Nuryakin. 2022. “Temporary Staff Performance in Universities: How can the Employee-organization Relationship be Enhanced in an Institution?” International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147-4478) 11 (5): 293–303. https://doi.org/10.20525/ijrbs.v11i5.1874

- Ribeiro-Soriano, Domingo, and David Urbano. 2010. “Employee-organization Relationship in Collective Entrepreneurship: An Overview.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 23 (4): 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811011055368.

- Rice, Danielle B, Hana Raffoul, John PA Ioannidis, and David Moher. 2020. “Academic Criteria for Promotion and Tenure in Biomedical Sciences Faculties: Cross Sectional Analysis of International Sample of Universities.” BMJ: 369, m2081. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2081.

- Robinson, Sandra L., S. Kraatz Matthew, and M. Rousseau Denise. 1994. “Changing Obligations and the Psychological Contract: A Longitudinal Study.” Academy of Management Journal 37 (1): 137–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/256773.

- Rousseau, Denise M. 1990. “New Hire Perceptions of Their Own and their Employer's Obligations: A Study of Psychological Contracts.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 11 (5): 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030110506.

- Rousseau, Denise. 1995. Psychological Contracts in Organizations: Understanding Written and Unwritten Agreements. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Rousseau, Denise. 1995. Psychological Contracts in Organizations: Understanding Written and Unwritten Agreements. Sage publications.

- Rousseau, Denise M, and Snehal A. Tijoriwala. 1998. “Assessing Psychological Contracts: Issues, Alternatives and Measures.” Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 19 (S1): 679–695.

- Ruokolainen, Mervi, Saija Mauno, Marjo-Riitta Diehl, Asko Tolvanen, Anne Mäkikangas, and Ulla Kinnunen. 2018. “Patterns of Psychological Contract and their Relationships to Employee Well-being and In-role Performance at Work: Longitudinal Evidence from University Employees.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 29 (19): 2827–2850. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1166387.

- Schein, Edgar H., and Edgar H Schein. 1970. Organizational Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Shen, Jie. 2010. “University Academics’ Psychological Contracts and their Fulfilment.” Journal of Management Development 29 (6): 575–591. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011046549.

- Shore, Lynn, and M. Lois E Tetrick. 1994. “The Psychological Contract as an Explanatory Framework in the Employment Relationship.” Trends in Organizational Behavior 1 (91): 91–109.

- Si, Jinghui. 2022. “No Other Choices But Involution: Understanding Chinese Young Academics in the Tenure Track System.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 45 (1): 53–67.

- Snyman, Annette M, Melinde Coetzee, and Nadia Ferreira. 2022. “The Psychological Contract and Retention Practices in the Higher Education Context: The Mediating Role of Organisational Justice and Trust.” South African Journal of Psychology 53 (2): 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463221129067.

- Strunk, Katharine, Nathan Barrett, and Jane Arnold Lincove. 2017. When Tenure Ends: The Short-run Effects of the Elimination of Louisiana’s Teacher Employment Protections on Teacher Exit and Retirement. Education Research Alliance Technical Report. Retrieved from https://educationresearchalliancenola.org/files/publications/041217-Strunk-Barrett-Lincove-When-Tenure-Ends.pdf.

- Tang, Yung-Tai, and Chen-Hua Chang. 2010. “Impact of Role Ambiguity and Role Conflict on Employee Creativity.” African Journal of Business Management 4 (6): 869.

- Tipples, Rupert, Branka Krivokapic-Skoko, and Grant O'Neill. 2007. “University Academics’ Psychological Contracts in Australia and New Zealand.” New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations 32 (2): 33–52.

- Wang, Siyi, and Glen Jones. 2021. “Competing Institutional Logics of Academic Personnel System Reforms in Leading Chinese Universities.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 43 (1): 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2020.1747958.

- Wang, Li, and Ka Ho Mok. 2013. Neo-liberal Educational Reforms. In A. Turner & H. Yolcu (Eds.), Neo-liberal educational reforms: A critical analysis, pp. 139–163. London: Routledge.

- Yang, Xi, X. L. Cai, and T. S. Li. 2023. “Does the Tenure Track Influence Academic Research? An Empirical Study of Faculty Members in China.” Studies in Higher Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2238767.

- Yesufu, Lawal O. 2020. “The Impact of Employee Type, Professional Experience and Academic Discipline on the Psychological Contract of Academics.” International Journal of Management in Education 14 (3): 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMIE.2020.107057.

- Zhang, Zewei. 2021. “Current Situation and Problems of the Reform of Pre-employmen Long Appointment System in ‘Double First-class’ Universities: Analysis of Teacher Employment System in 42 ‘Double First-class’ Universities.” Journal of Higher Education Research 4:77–82. [In Chinese].