ABSTRACT

Professional identity formation (PIF) is an integral part of educating professionals. A well-formed professional identity helps individuals to develop a meaningful professional self-understanding that facilitates their transition to and sustainability in professional work. Although professional identity and its formation are well theorized, it is largely unclear how the underpinning interpretive process of professional identity work leads to observable changes in thoughts, feelings and behaviours, and how these insights can be used in educational practice. To address this gap, we conducted an integrative review of 77 empirical articles on professional identity formation and inductively developed a four-fold typology of professional identity work, through which individuals reportedly make the shift from individual to professional. The theoretical contribution of this article is a more nuanced understanding of the practical manifestations of professional identity work. As a practical contribution, the typology may be used as a heuristic through which educators of professionals can support their students’ professional identity formation, particularly where this is halted or complicated by obstructions.

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed significant interest in professional identity formation (PIF) in teaching (e.g. Deng et al. Citation2018; Izadinia Citation2016; Kim et al. Citation2021; Pillen, Beijaard, and den Brok Citation2013), healthcare (e.g. Cruess et al. Citation2015; Hatem and Halpin Citation2019; Merlo et al. Citation2021; Noble et al. Citation2015), STEM (e.g. Nadelson et al. Citation2017; Park, Chuang, and Hald Citation2018; Tomer and Mishra Citation2016) and other fields. A well-formed professional identity supports students with the transition to professional work, preparing them for the responsibilities of their role, for moral and ethical decision-making, and for thriving amidst often conflicting discourses, priorities and practices encountered when entering a profession (Pillen, Beijaard, and den Brok Citation2013; Wald Citation2015). Despite different conceptual underpinnings of PIF, there is widespread agreement that it is the process through which individuals construct a professional identity (e.g. Slay and Smith Citation2011; Tan, Van der Molen, and Schmidt Citation2017) that enables students to learn the requisite knowledge, skills, behaviours and norms of professionalism (Wilkins Citation2020), and develop a sense of belonging to their chosen profession (Trede, Macklin, and Bridges Citation2012).

Contemporary research emphasizes the benefits of a well-formed professional identity, for example for employability (Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021) and wellbeing (Toubassi et al. Citation2023), which can be fostered through specific educational interventions (Kratzke and Cox Citation2021). Despite recognizing the potential challenges to integrate PIF into a degree programme (Wilkins Citation2020), recent work tends to emphasize processes (e.g. reflection) and education opportunities (e.g. workplace socialization, entrusted responsibilities) for which student outcomes can be demonstrated (e.g. making sense of workplace challenges, self-understanding of one’s professional values). They are thus proposed to support PIF (Carter Citation2021; Jowsey et al. Citation2020; Sarraf-Yazdi et al. Citation2021). In this article, we advance this work by focusing on professional identity work (PIW), the interpretive process that underpins PIF and through which professional identity is formed. PIW involves interpretation of personal, social and contextual experiences to construct, strengthen, maintain, revise and reconstruct one’s professional self-understanding (drawing on Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003). In this way, as we will show below, PIW transcends professional boundaries as students and graduates from different professional contexts and roles reportedly engage in similar interpretive work when developing, strengthening and adapting their professional self-understanding. PIW thus results in changes in people’s thoughts, feelings and/or behaviours (Feiman-Nemser Citation2008) which individuals entering or working in any profession are likely to experience and which are important for their educators to know so that students’ education and socialization can be appropriately supported.

While it is known that PIF is important and that it is scaffolded using specific educational interventions, there is currently little understanding of how students’ identity work leads to professional identity formation. Although PIF is well theorized in the higher education literature (e.g. Jarvis-Selinger et al. Citation2019; Mackay Citation2017; Nyström Citation2009; Rodrigues and Mogarro Citation2019) – albeit largely within professional silos, the practical manifestations of PIW remain largely unknown (e.g. Nadelson et al. Citation2017). By practical manifestations we mean indications of changes in students’ thoughts, feelings and/or behaviours that enable conclusions about the extent to which they have developed the requisite knowledge, skills, behaviours and norms of professionalism as well as feelings of belonging to their chosen profession. Such insights will enable educators of professionals to understand students’ emerging priorities as a professional and help them find their place in the profession, particularly where recommended educational interventions are ineffective, contextually inappropriate or unfeasible. PIW may further involve dissonance as the expected identity clashes with what is encountered or can be achieved in practice (Wald Citation2015), affecting professionals’ wellbeing and resilience (McCann et al. Citation2013) and contributing to attrition (Cidlinska et al. Citation2022). Without understanding the underpinning interpretive process of PIW, educators cannot effectively adapt and contextualize recommendations from the extant research in curriculum design, pedagogic practice or student support.

Current research also demonstrates newly identified complexities for educators of professionals. The existing models tend to conceptualize a process of development towards an integrated and cohesive professional identity that can be negotiated across contexts when the individual is successfully ‘formed’ (e.g. Nyström Citation2009). However, more critical work has argued that educating for global, multicultural or interprofessional work means that professional identities remain in flux, being re-shaped between multiple versions of an individual’s professional self as they move between contexts (Best and Williams Citation2019; Findyartini Citation2019; Nicholson and Maniates Citation2016). Minority groups and non-white, non-Western populations have argued that the white North American / Euro-centric source of much of the extant PIF literature may present challenges when trying to embed some of the advocated practices, such as socialization (e.g. lack of role models) or personal value reflection (e.g. in regions where social and cultural values take precedence over those of the institution or individual) (Wyatt, Rockich-Winston, et al. Citation2021; Zaneb and Armitage-Chan Citation2022). A better understanding of students’ priorities for their professional identity, the underpinning interpretive process of PIW and the ways in which educational strategies lead to PIF may therefore better support educators as they contextualize, adapt and apply published curriculum recommendations to their students’ unique needs.

To address this gap, this paper seeks to answer the question ‘how is professional identity work manifested in the extant research’. As educators and curriculum developers in professional programmes interested in how proposed interventions lead to PIF, we conducted an integrative review of 77 empirical articles that provide at least one excerpt indicating PIW. Using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), we inductively developed an original typology consisting of four categories called (1) ‘becoming’ (PIW as a process of learning and development), (2) ‘aligning’ (PIW as a process of bringing into alignment people’s assumptions, values, norms, behaviours and professional self-understanding with the external expectations), (3) ‘exploring’ (PIW as exploring the type of professional a person wants to be), and (4) ‘struggling’ (inability to achieve meaningful PIW), which we will introduce below.

The contribution of this paper is the novel typology of the practical manifestations of PIW, which enhances the current understanding of PIF in professional education by showing how students’ identity work leads to professional identity formation. It provides important insights into the often elusive process of professional identity work and enables educators to better understand and support their students’ PIF by using the typology as a heuristic and adapting it to their specific professional context. This is particularly pertinent where established educational practices prove troublesome or require contextualization, or where students are struggling to apply recommended educational strategies to support their PIF.

Methodology

We have chosen PIW, the interpretive process underpinning PIF, as the focus for this integrative review because it transcends professional contexts, enabling researchers to ‘step outside disciplinary boundaries […] and venture beyond knowledge silos’ (Breslin and Gattrell Citation2023, 139). According to Torraco (Citation2005, 356), integrative literature reviews are ‘a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated’. He further posits that these reviews enable researchers to generate new insights into an established or emerging topic. In our case, PIW is an emerging topic that, arguably, ‘would benefit from a holistic conceptualization and synthesis of the literature to date’ (ibid, 357), particularly since it operates in multiple professional contexts. We have used Cronin and George’s (Citation2023) recent framework for conducting integrative reviews to achieve rigour and veracity in our approach.

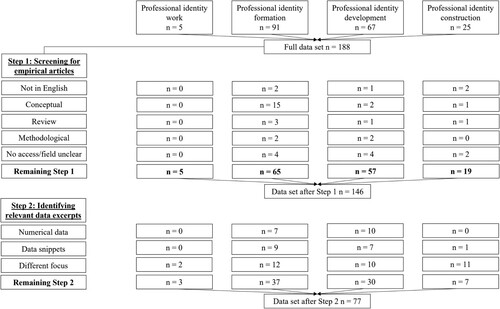

Following Cronin and George’s (Citation2023) first step of identifying the types of studies available for synthesis, we searched the ISI Web of Science database (a comprehensive repository covering a range of professions) for ‘professional identity work’ as an exact term in the title, which identified only five articles. This dearth of existing research led us to extend the search to include the broader yet closely related constructs of ‘professional identity formation’, ‘professional identity development’, and ‘professional identity construction’ as exact terms in the title to identify articles that foreground these constructs, which we expected to be most relevant. The search was limited to a 10-year period (01 January 2012–31 December 2021) to provide a contemporary review and to articles published in English as these were expected to target a global audience. The combined searches yielded 188 results.

In Cronin and George’s (Citation2023) second stage, literature review, we firstly downloaded these articles and screened the abstracts, removing those written in other languages than English (n = 5). Due to our interest in practical examples of PIW, we excluded non-empirical articles (conceptual papers n = 18; review papers n = 5; methodological papers n = 4) and articles that examined the construct without reference to a professional or occupational context (e.g. ‘school children’; n = 7). Articles that could not be sourced despite our best attempts were also excluded (n = 3). Then we read the findings sections of the remaining 146 empirical articles to identify any narrative or reflective data excerpts from which conclusions about changes to people’s thoughts, feelings and/or behaviours (see Feiman-Nemser Citation2008) as evidence for PIW could be drawn. In this process, we excluded articles that evaluated an educational activity (n = 35), articles that only provided numerical data (n = 17) and articles that only included short snippets of data (n = 17), which provided insufficient insights into PIW. In this step, we also mapped the professional field and countries where the underpinning research was conducted to understand the varying ‘representation from each community of practice’ (Cronin and George Citation2023, 170). The final dataset includes 77 empirical articles from 15 professions and involving 23 countries. depicts a schematic representation of this second stage.

Further information about the empirical studies in our dataset is available in the supplementary file.

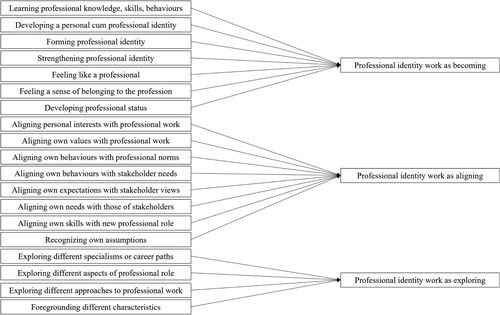

Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) and synthesis (the third step identified by Cronin and George Citation2023) followed. We coded empirical examples (our unit of analysis) reported in our dataset using an inductive thematic approach, in which labels were assigned to passages of text in which research participants reported changes to their thoughts, feelings and/or behaviours (see Feiman-Nemser Citation2008) as part of their professional education and socialization. A strength of this approach is arguably the focus on PIW, the interpretive process underpinning PIF that does not seem to be dependent on a specific professional context as our analysis indicates. A total of 19 codes were generated and clustered into initially three analytical categories as shown in .

The category ‘becoming’ frames PIW as learning and development, with people foregrounding how they learn the requisite knowledge, skills and behaviours, how they integrate their personal and professional identities, and how they construct or maintain their professional self-understanding. These codes foreground individual feelings of becoming (or being) a professional and developing professional status.

The category ‘aligning’ frames PIW as bringing into alignment people’s assumptions, values, norms, behaviours and professional self-understanding with the external expectations of stakeholders, such as professional associations, pupils, patients, clients etc. They foreground the connection between the personal and social dimensions of PIF (e.g. Rodrigues and Mogarro Citation2019) and imply that a professional identity may never be fully formed due to changes to professional contexts, including increasing use of interprofessional teamwork (e.g Best and Williams Citation2019).

The category ‘exploring’ frames PIW as identifying the type of professional a person wants to be. They foreground the potential multiple professional identities in terms of specialisms (e.g. primary / secondary / special needs teacher in education, general practitioner / surgeon / neurologist etc. in the medical sciences), work environments (e.g. state or private practice in healthcare, large corporate / small and medium-sized enterprise), workplace cultures (e.g. extent to which personal / professional agency is encouraged or limited), or professional role (e.g. educational leader, engineering researcher). The emphasis is on finding the right ‘place’ or ‘niche’ for the individual’s longer-term career path.

A fourth and smaller category was identified during the analysis. Called ‘struggling’, these excerpts foreground significant difficulties with forming a professional identity, emphasizing perceived barriers to enacting an envisaged or desired professional self-understanding.

Since PIW has been significantly understudied across professions, the search for its practical manifestations required both a relatively large dataset comprising a range of professional contexts from which relevant empirical examples could be drawn and an inductive analytical approach to identify and categorize these excerpts across professional ‘silos’. The analytical categories of ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’, ‘exploring’ and ‘struggling’ do not correspond to the 77 articles in our dataset but to empirical examples reported in these articles that provide insights into the practical manifestations of PIW. In some instances, an article reported excerpts that fitted in more than one category in our typology because its aims and focus differed from ours.

Importantly, we do not claim that our dataset and the resulting typology are exhaustive and will outline below areas for future research that could address the limitations in our approach. Rather, the value of the typology is two-fold: firstly, it enables a better understanding of how students’ identity work leads to professional identity development and how educators can scaffold and support their students’ PIF through specific educational interventions. Secondly, the typology identifies the underpinning process of PIW that has been reported in empirical studies across professional fields and countries, which makes it relevant for educators across a wide range of professions and geographic contexts.

Results

‘Becoming’

‘Becoming’ frames PIW as a process of learning and development during which individuals start to think, feel and act as professionals in their chosen line of work (see Feiman-Nemser Citation2008) as illustrated by the following excerpts:

“I can see now how I have changed, how I have blossomed { … }, how my insecurities are fading away, how I am good enough for someone.” (second year note) (Boncori and Smith Citation2020, 278–79, emphasis added)

“I have an idea of where I see myself as a designer in the future and how I will approach designing. I am not there yet, as it will take many years for me to master the skill. { … } The way I think about design today is completely different compared to how I thought about it before starting this class.” (Student 5, Prompt 5.5, S13) (Tracey and Hutchinson Citation2018, 276, emphasis added)

It suddenly became normal, when I tell my family at home, ‘“Oh, we have a dissection course. And that’s really fun.” And then I notice that they might think that’s weird. And then I think […] half a year ago I myself might have thought that’s weird. So I notice […] something changed.” (Student 25). (Shiozawa et al. Citation2019, 6, emphasis added)

Despite a generally positive emphasis on growth, some excerpts indicate a disconnect between the stage of learning that individuals perceive to have reached and the learning they feel is required before they have ‘properly’ ‘become’ a professional. This disconnect is evident across professional fields, such as software engineering (‘I need to learn a lot of coding and the real things before becoming [a software engineer]’, Tomer and Mishra Citation2016, 159) or medicine (‘It’s strange when patients call me “Doctor” though. I always correct them and tell them that I’m a medical student’, Hatem and Halpin Citation2019, 3). Other data excerpts suggest that participants do not feel they have ‘become’ a professional based on discipline-specific knowledge alone but identify a need for additional development, such as self-awareness, building relationships and developing personal attributes (e.g. empathy, ethical values) as illustrated in the following excerpt:

I’ve learned that being a physician requires so much more than simply recognizing the diseases and treatments. I must learn to be aware of my biases and assumptions that may impact patient care. I must develop ethical values that will not be swayed by stress or pressure. I must prioritize communication and empathy so that I am able to establish meaningful relationships with my teammates and my patients. I must learn to value my own health, through mindfulness, nutrition, and exercise, before I focus on the health of others. (Merlo et al. Citation2021, 5, emphasis added)

‘Aligning’

‘Aligning’ frames PIW primarily as a process of bringing into alignment one’s assumptions, values, norms, behaviours and emerging professional self-understanding with the external expectations of professional associations and other stakeholders. As such, and in contrast to ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’ emphasizes the contextual nature of PIF. This is illustrated by the following quotes:

Emma had become aware that her interventions actually led to inactive students. This was a boundary experience. She asked herself questions on how to change her behaviour and was able to take the first steps in making a shift in her tutor style from teacher-oriented to learner oriented. (Assen et al. Citation2018, 135, emphasis added)

Residents identified a change in their personal and professional identity, described as a discovery, or rediscovery, of the purpose of medicine and the identity of a physician: “Such an experience inherently redefines for an individual why they entered the medical profession in the first place … to remind myself that the most important job as a physician is to care for patients” (2002/Haiti/internal medicine). (Sawatsky et al. Citation2018, 1386, emphasis added)

Renate […] experienced competition with another student when trying to get access to an experience that was also meaningful […]. The fact that this colleague managed to get access, while Renate failed, made her think about herself and her way of getting things done: “Her way is much more efficient, but I am not sure if that is the person I want to be. I think not. So, I notice I am torn between the person I want to be and the things I want to achieve.” (First rotation). (Adema et al. Citation2019, 1570, emphasis added)

The teachers argued that they would persist in the profession of teaching when school policies are against their expectation, yet they would resign and change their school […]: “I prefer to resign. The profession is part of our life and it should be aligned to our values. If not, I will be challenged and I suffer, so I prefer to quit the school.” (Nazari, Miri, and Golzar Citation2021, 9, emphasis added)

Tess takes responsibility for her students, but at the same time she is close to the students, because of her age. She likes to have some fun with them in the classroom and also meets students when she goes out. She experiences difficulties regarding the role she needs to take inside and outside the school with regard to her students. She wants to have some fun with them, but is aware of her responsibilities as a teacher. (Pillen, Beijaard, and den Brok Citation2013, 248, emphasis added)

The learning was seen as perpetual and part of a natural progression: “It’s a lifelong process … Just like with our identity who we are outside our profession. We may have a solid foundation, have our core values that we believe in, but as we practice, experience more and more problems/situations, we mold and adapt. Our clients’ experiences, and our own experiences shape us. We learn something new every day, and though our identity may not change drastically each day, things add on or get removed and modified over time.” (Gignac and Gazzola Citation2016, 309, emphasis added)

‘Exploring’

‘Exploring’ frames PIW primarily as a process of working out the type of professional a person wants to be in terms of career path, specialism, professional role or approach to their work. Although it also connects individual and contextual aspects of PIF, ‘exploring’ differs from ‘aligning’ by emphasizing the potential multiplicity of professional identities arising from specific specialisms and roles as shown in the following quote:

Someone else described the customization of their identity as a personally crafted undertaking: “I believe the role I play in shaping my identity is in what I choose to focus on … the different organizations I choose to work in … specializing in different areas … and then I think a big part of it is how I take my learning and my practice and piece them together. The piecing together helps me identify who I am as a counsellor.” (Gignac and Gazzola Citation2016, 308, emphasis added)

When I view {the professional identities of} [writer, scholar, and researcher] from a functional perspective, the responses they evoke are much different than when I view them as professions, and THAT leads me to wonder why I automatically interpreted them in that way? My negative feelings are feelings about stereotypical images of the professions as opposed to feelings about the work that a writer, a scholar, or a researcher might do. (Lawrence Citation2017, 198, emphasis added)

‘Struggling’

The smaller category of ‘struggling’ indicates that PIW can break down and may consequently prevent individuals from constructing a meaningful professional self-understanding. Rather than simply working through tensions and experienced disconnects, which were part of ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’ and ‘exploring’, ‘struggling’ represents a more substantial arrest of PIW as individuals struggle to find a sense of belonging, comfort and cohesion with their professional role. This is powerfully illustrated through the following data excerpts from two studies that involved mask-making in medical education:

In this case we again hear a female student wrestling with identity dissonance. We were struck by the change in voice in the narrative’s i-poem. The student used the personal pronoun ‘my’ in association with the mask’s portrayal of life prior to medical school: “my complexion is rosy my eyes are bright my lips turn upward in a smile my mental landscape is represented by a shining sun”.

While describing being in medical school, she no longer represents herself in the descriptions of the mask. In describing her life at {institution}, she uses the definite article “the” instead of personal pronouns to refer to her physical self:

the lips drawn together

the eyes more plain

the cheeks less rosy.

In this linguistic transition, we heard the silenced gap that separates the student’s personal identity (i.e., my) from her professional identity as a military medical trainee (i.e., the). (Joseph et al. Citation2017, 103, emphasis added)

In a moving disclosure, one Mask student (#72) commented, “The mask is a representation of how I feel at this point in my medical training. I feel pressure to speak positively of medicine and my experiences (yellow/sun colors) although I carry a lot of sadness in my head (blue/purple). My eye has been trained to see the best in situations (gold), but I have also been bruised by my experiences (black eye). I have felt anger (red cheek) and embarrassment (pink cheek) but must still speak sparkling words as I go through this journey.” Researchers observed that this mask was divided into thirds, with the expressive part (the mouth) bathed in sun colors, while the mental anguish remains hidden. They speculated that the rosy cheeks were an outward sign of glowing wellbeing, but disguised feelings of anger and shame. (Shapiro et al. Citation2021, 610–11, emphasis added)

I would say the “not Knowing” [sic] leads to an inability to construct a professional identity with confidence. I am training to do *this*. I may only be allowed to do *that*, or I may not be allowed to do anything at all. (Gignac and Gazzola Citation2016, 305, emphasis added)

Nika { … } felt taken aback by the restrictive rules, issues by LI {language institute} authorities, in terms of composing lesson plans, and teaching methods and materials: “I used to be an innovative {English as a foreign language} teacher, but the LI took that away from me. Everything was stipulated in advance. We had no freedom in designing our plans or running our classes.” (Moradkhani and Ebadijalal Citation2021, 10, emphasis added)

Problems inside and outside classroom {sic} prevent you from thinking about the quality of your teaching. My once utopic viewpoint has become a dystopic one. All I try to do is to get my students quiet, and that’s a hard task. { … } What you face in the real classroom is so complex and different from what you have studied in the books that you always feel helpless in doing your duty. (Mahmoudi-Gahrouei, Tavakoli, and Hamman Citation2016, 591, emphasis added)

I guess it’s difficult, … when {as a pharmacist} you make recommendations to the doctors and they don’t choose to take it, that’s when I find it really difficult … I … felt like … my hands are tied, because he is like the main principal care provider so you can’t really undermine what he says but then again you sort of have this in the back of your mind that it is the wrong thing. (Noble et al. Citation2015, 207–8, emphasis added)

Discussion

As educators and curriculum developers in professional programmes, we sought to examine in this paper how the interpretive process of PIW is manifested in the extant PIF research, and thus to deepen the current understanding of how educational interventions such as reflection and socialization, assumed to support PIF, achieve this in practice. The paper derives from an integrative review of 77 empirical articles from a range of professional and geographic contexts that provide at least one data excerpt evidencing the practical manifestations of PIW. Through inductive thematic analysis we developed a four-fold typology consisting of ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’, ‘exploring’, and ‘struggling’ that capture different framings of PIW that seem to apply across professional fields. Each of these foregrounds a particular aspect of PIW that has practical implications for supporting the education and socialization of professionals and for problem-solving when PIF becomes problematic.

The excerpts presented above to illustrate the four categories of our typology relate to well-established models of PIF, such as learning professional knowledge, skills and behaviours (e.g. Bentley et al. Citation2019), professionalism (Wilkins Citation2020), socialization into communities of practice (e.g. Cameron and Grant Citation2017; Lave and Wenger Citation1991), developing a personal-cum-professional identity (Cruess et al. Citation2015; Jarvis-Selinger, Pratt, and Regehr Citation2012; Trede, Macklin, and Bridges Citation2012), gaining confidence (e.g. Izadinia Citation2016; Moss, Gibson, and Dollarhide Citation2014; Sawatsky et al. Citation2020), developing professional status (e.g. Mahmoudi-Gahrouei, Tavakoli, and Hamman Citation2016), and ‘mobilizing’ a particular identity when working across professional fields (Best and Williams Citation2019). Additional information about the articles included in our dataset is provided in the supplementary file.

In practice, the four categories of our typology are likely co-exist as individuals proceed through professional education and socialization. It is possible that in their quest to ‘become’ a professional, students seek to ‘align’ their emerging professional identity to wider expectations. Drawing on Nyström (Citation2009), Armitage-Chan and May (Citation2019), for example, argue that students may strive to simply ‘fit in’ with their professional context early in their career, rather than develop a personal-cum-professional identity (e.g. Jarvis-Selinger, Pratt, and Regehr Citation2012; Trede, Macklin, and Bridges Citation2012). Similarly, students may be able to search for their professional ‘niche’ and/or overcome struggles by engaging with a wider group of stakeholders and learning more about different career paths and roles in the profession (‘exploring’). A well-known example from medical education is the Healer’s Art course (Lawrence et al. Citation2020; Rabow, Wrubel, and Remen Citation2007), which provides a space for students to engage with their own values as well as the values underpinning the medical profession. Nevertheless, for analytical purposes it is beneficial to consider the four categories of our typology as discrete to enhance the current understanding of PIW and develop and apply educational interventions that support students’ PIF.

Viewing these four categories as distinct helps to explain what is happening when individuals undertake PIW, particularly for those students who successfully utilize recommended educational strategies. These strategies have tended towards the following common, consistent themes: authentic workplace experiences, entrusted responsibilities, socialization, and reflection on tensions experienced (e.g. Cruess, Cruess, and Steinert Citation2019; Fitzgerald Citation2020; Sarraf-Yazdi et al. Citation2021; Toubassi et al. Citation2023). However, simply introducing ‘best practice’ interventions without understanding how they support – or hinder – professional identity work is problematic. Importantly, Sarraf-Yazdi et al. (Citation2021) argue that simply introducing opportunities for PIF (such as workplace exposure) may be counterproductive for some students. If there is inadequate support for the mechanisms by which socialization, workplace exposure and reflection lead to PIF, then an inability to manage and respond to the tensions and disconnects encountered may present a barrier to ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’ and ‘exploring’. PIF is then arrested, and due to their ‘struggles’, students may have no option but to revert to a prior, naïve self and reaffirm their pre-professional self-identity beliefs that jar with professional practices and expectations. This ‘arrest’ can be observed in excerpts relating to ‘struggling’: the possibility that a person feels unable – at least temporarily – to construct a meaningful professional identity. In her study of adolescents, Marcia (Citation1980) refers to ‘identity moratorium’ to describe situations in which individuals struggle to align their personal self-understanding and values to a largely predefined identity. More recently, Cidlinska et al. (Citation2022) explore such struggles in the context of increasingly neoliberal structures in higher education. In contrast to the tension experienced in ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’ and ‘exploring’, ‘struggling’ may involve deep-seated hurt (e.g. depiction of a black eye, see Shapiro et al. Citation2021) or feelings of being more permanently stuck (e.g. metaphor of tied hands, see Noble et al. Citation2015).

Recommended educational interventions may also be problematic for underrepresented groups. As Wyatt, Balmer et al. (Citation2021) and Wyatt, Rockich-Winston et al. (Citation2021) have explained, current interventions derive from studies of dominant populations and neglect the experiences and challenges of minority students. For example, in supporting ‘becoming’, cultural variation in motivations for being a professional are often neglected; in practice this means that the PIF interventions associated with ‘becoming’ may ignore cultural norms that devalue the personal transition to physician status and instead prioritize the retaining of family sociocultural values and being able to assist and support one’s community (Wyatt, Rockich-Winston, et al. Citation2021; Zaneb and Armitage-Chan Citation2022). The process of ‘becoming’ is therefore problematic when one’s choice for a profession jars with the dominant voice in education or society.

Similarly, Wyatt, Balmer et al. (Citation2021) have highlighted that low-power groups are not empowered to question the identity of others, particularly those who are held in high esteem. Some students may also benefit from social and cultural capital that facilitates their socialization into the workplace and helps them to negotiate the different identities encountered (Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021). This makes ‘exploring’ problematic when educational interventions rest on the assumption that all students have the necessary social and cultural capital to negotiate themselves into different groups and to reflect on the multiple role models they encounter in the professional and work contexts to which they are exposed to determine their own ‘best fit’. Finally, Zaneb and Armitage-Chan (Citation2022) describe the stigmatization of the veterinary profession in certain global regions, thus problematizing the process of ‘aligning’: students may struggle with the tension arising from aligning their professional identity with a socially stigmatized group.

We propose that our typology can provide a heuristic for educators of professionals to identify learning activities that foster ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’ and ‘exploring’ or that support those students who may be ‘struggling’, in ways that are relevant to specific professional disciplines, local contexts and diverse student groups. ‘Becoming’ may be fostered through formal and informal learning activities that scaffold students to take on the activities and responsibilities that represent the professional they wish to become. Tensions that arise when students do not feel ready to be a professional can be managed through increasing their engagement in professional activities. ‘Aligning’ may be fostered through learning activities that prompt students to analyse their expectations for professional work alongside the needs and expectations of key stakeholders, helping them identify role models and aspired sets of professional values. ‘Exploring’ may be fostered by learning activities that expose students to different aspects of professional practice, such as internships through which they can get a ‘taste’ of different specialisms, roles and work environments. Heightened awareness of where this may be problematic, such as lacking skills or empowerment for reflecting on the multiple ways of being a professional can help educators to target their efforts accordingly within their specific professional context. Recognizing the characteristics of ‘struggling’ enables educators to identify such students and help them find more productive ways to engage in PIW. The arrested PIF that this involves might be alleviated by opportunities to legitimately express negative feelings or struggles, and work through them. Indicative learning activities that support each aspect of PIW are provided in , which educators can contextualize, adapt and apply to their specific situation and student needs. Importantly, we encourage fellow educators of professionals to develop a coherent strategy of interventions that foster the priorities inherent in ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’ and ‘exploring’ and that support students who are ‘struggling’.

Table 1. Indicative learning activities supporting each aspect of professional identity work.

Conclusion

This integrative review has addressed a gap in PIF research – its practical manifestations – to contribute theoretically to the understanding of the interpretive process of PIW and practically to the further development of targeted learning activities fostering PIF. As discussed above, the contemporary literature focuses on the benefits of a well-formed professional identity and associated educational interventions. There is thus benefit in centring higher education around PIF and having a consistent message about generally effective educational methods. However, there is also concern that these practices are often derived from the needs of dominant groups (largely white / Western-centric), leading to a lack of attention as to why established PIF interventions may fail to support underrepresented student groups.

Our inductively derived typology adds to contemporary PIF research by articulating the interpretive processes underpinning the recommended educational interventions. Where specific formal and informal curricular activities are in place, educators of professionals can consider whether these are intended to foster students’ transition to ‘becoming’ a professional, encourage students to ‘align’ their emerging professional identity to a specialism or role, or engage them in identity ‘exploration’. Educators can also reflect on the assumptions they are bringing to supporting students’ PIF and use this understanding to develop their practice to better meet their students’ needs. This awareness is particularly pertinent because ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’ and ‘exploring’ may be problematic if there is a disconnect between the intended PIF outcome and students’ identity expectations, variation in the nature of students’ identity goals for their personal or disciplinary context, or a deficiency in skills or agency in being able to process their experiences. As such, the identity goals, reflective skills, availability of role models etc. may need to be reviewed and refined so that ‘becoming’, ‘aligning’ and ‘exploring’ can more effectively be employed by students in their professional identity work.

Our review identified the following areas for further research. Firstly, there is scope to examine our typology through a more comprehensive review of the PIF literature. Using multiple databases, broadening the search terms to incorporate different combinations (e.g. ‘development of professional identity’), and identifying additional sources from reference lists would enable researchers to ascertain if the four categories in our typology might be more prevalent in certain professional fields and/or conceptualizations of PIF, and also if there might be other interpretive processes at play. There may also be scope to conduct quantitative studies on PIW, developing and validating relevant measurement scales.

Secondly, it was notable that empirical examples of how individuals seek to maintain, revise or reconstruct their professional identity (see Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003) are underrepresented in the extant research. This may be because the majority of studies in our dataset examined PIF in initial professional education when students try to ‘become’ a professional, ‘align’ their emerging identity to wider expectations, or ‘explore’ what kind of professional they could be. Future research should therefore examine the PIW of established professionals, using multiple points of data collection to identify, track and reflect upon any changes to individuals’ thoughts, feelings and behaviours (see Feiman-Nemser Citation2008) over time. Particularly beneficial may be longitudinal research across key transition points, such as from professional studies into practice, or from professional practice into leadership. These studies might fruitfully be conducted within a specific professional setting to provide more contextual insights than our review was able to achieve.

Thirdly, we see significant scope to utilize more innovative research methods to study PIW (see Winkler, Reissner, and Cascón-Pereira Citation2023). Reflective assignments provide rich ground for exploring the changes to an individual’s professional identity as part of their identity work and may be complemented by creative means such as mask-making (Joseph et al. Citation2017; Shapiro et al. Citation2021), art, poetry or music (Armitage-Chan et al. Citation2022) to capture symbolic meanings. Similarly, we encourage greater use of naturally occurring data such as student assignments, class observations, or online methods such as video diaries or vlogs through which students’ PIW can be investigated in more depth in its original professional context.

Supplemental Figures and Tables

Download MS Word (209.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adema, M., D. H. J. M. Dolmans, J.(A. N.) Raat, F. Scheele, A. D. C. Jaarsma, and E. Helmich. 2019. “Social Interactions of Clerks: The Role of Engagement, Imagination, and Alignment as Sources for Professional Identity Formation.” Academic Medicine 94 (10): 1567–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002781.

- Armitage-Chan, E., and S. A. May. 2019. “The Veterinary Identity: A Time and Context Model.” Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 46 (2): 153–62. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0517-067r1.

- Armitage-Chan, E., S. C. Reissner, E. Jackson, A. Kedrowicz, and R. Schoenfeld-Tacher. 2022. “How Do Veterinary Students Engage When Using Creative Methods to Critically Reflect on Experience? A Qualitative Analysis of Assessed Reflective Work.” Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 49 (5): 632–640. http://doi.org/10.3138/jvme-2021-0070.

- Assen, J. H. E., H. Koops, F. Meijers, H. Otting, and R. F. Poell. 2018. “How Can a Dialogue Support Teachers’ Professional Identity Development? Harmonising Multiple Teacher I-Positions.” Teaching and Teacher Education 73 (July): 130–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.019.

- Baxter Magolda, M. B. 2008. “Three Elements of Self-Authorship.” Journal of College Student Development 49 (4): 269–84. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0016.

- Bentley, S. V., K. Peters, S. A. Haslam, and K. H. Greenaway. 2019. “Construction at Work: Multiple Identities Scaffold Professional Identity Development in Academia.” Frontiers in Psychology 10 (March): 628. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00628.

- Best, S., and S. Williams. 2019. “Professional Identity in Interprofessional Teams: Findings from a Scoping Review.” Journal of Interprofessional Care 33 (2): 170–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1536040.

- Boncori, I., and C. Smith. 2020. “Negotiating the Doctorate as an Academic Professional: Identity Work and Sensemaking Through Authoethnographic Methods.” Teaching in Higher Education 25 (3): 271–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1561436.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Breslin, D., and C. Gattrell. 2023. “Theorizing Through Literature Reviews: The Miner-Prospector Continuum.” Organizational Research Methods 26 (1): 139–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120943288.

- Cameron, D., and A. Grant. 2017. “The Role of Mentoring in Early Career Physics Teachers’ Professional Identity Construction.” International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education 6 (2): 128–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-01-2017-0003.

- Carter, S. 2021. “ePortfolios as a Platform for Evidencing Employability and Building Rofessional Identity: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 22 (4): 463–74.

- Cidlinska, K., B. Nyklova, K. Machovcova, J. Mudrak, and K. Zabrodska. 2022. “‘Why I Don’t Want to Be an Academic Anymore?’ When Academic Identity Contributes to Academic Career Attrition.” Higher Education 85 (1): 141–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00826-8.

- Cronin, M. A., and E. George. 2023. “The Why and How of the Integrative Review.” Organizational Research Methods 26 (1): 168–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120935507

- Cruess, R. L., S. R. Cruess, J. D. Boudreau, L. Snell, and Y. Steinert. 2015. “A Schematic Representation of the Professional Identity Formation and Socialization of Medical Students and Residents.” Academic Medicine 90 (6): 718–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700.

- Cruess, S. R., R. L. Cruess, and Y. Steinert. 2019. “Supporting the Development of a Professional Identity: General Principles.” Medical Teacher 41 (6): 641–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260.

- Deng, L., G. Zhu, G. Li, Z. Xu, A. Rutter, and H. Rivera. 2018. “Student Teachers’ Emotions, Dilemmas, and Professional Identity Formation Amid the Teaching Practicums.” The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 27 (6): 441–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0404-3.

- Feiman-Nemser, S. 2008. “Teacher Learning: How Do Teachers Learn to Teach?” In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education: Enduring Questions in Changing Contexts, 3rd ed., edited by M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, and K. E. Demers, 697–705. New York: Routledge and the Association of Teacher Educators.

- Findyartini, A. 2019. “The Impact of Globalization on Medical Students’ Identity Formation.” eJournal Kedokteran Indonesia 6 (3): 215–21. https://doi.org/10.23886/ejki.6.7517

- Fitzgerald, A. 2020. “Professional Identity: A Concept Analysis.” Nursing Forum 55 (3): 447–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12450.

- Gignac, K., and N. Gazzola. 2016. “Negotiating Professional Identity Construction During Regulatory Change: Utilizing a Virtual Focus Group to Understand the Outlook of Canadian Counsellors.” International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 38 (4): 298–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-016-9273-8.

- Hatem, D. S., and T. Halpin. 2019. “Becoming Doctors: Examining Student Narratives to Understand the Process of Professional Identity Formation Within a Learning Community.” Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120519834546.

- Izadinia, M. 2016. “Preservice Teachers’ Professional Identity Development and the Role of Mentor Teachers.” International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education 5 (2): 127–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-01-2016-0004.

- Jarvis-Selinger, S., K. A. MacNeil, G. R. L. Costello, K. Lee, and C. L. Holmes. 2019. “Understanding Professional Identity Formation in Early Clerkship: A Novel Framework.” Academic Medicine 94 (10): 1574–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002835.

- Jarvis-Selinger, S., D. D. Pratt, and G. Regehr. 2012. “Competency is not Enough: Integrating Identity Formation Into the Medical Education Discourse.” Academic Medicine 87 (9): 1185–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968.

- Joseph, K., K. Bader, S. Wilson, M. Walker, M. Stephens, and L. Varpio. 2017. “Unmasking Identity Dissonance: Exploring Medical Students’ Professional Identity Formation Through Mask Making.” Perspectives on Medical Education 6 (2): 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40037-017-0339-Z.

- Jowsey, T., L. Petersen, C. Mysko, P. Cooper-Ioelu, P. Herbst, C. S. Webster, A. Wearn, et al. 2020. “Performativity, Identity Formation and Professionalism: Ethnographic Research to Explore Student Experiences of Clinical Simulation Training.” PLoS One 15 (7): e0236085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236085.

- Kim, D., Y. Long, Y. Zhao, S. Zhou, and J. Alexander. 2021. “Teacher Professional Identity Development Through Digital Stories.” Computers & Education 162 (March): 104040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104040.

- Kratzke, C., and C. Cox. 2021. “Pedagogical Practices Shaping Professional Identity in Public Health Programs.” Pedagogy in Health Promotion 7 (3): 169–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/2373379920977539.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lawrence, A. M. 2017. “(Dis)Identifying as Writers, Scholars, and Researchers: Former Schoolteachers’ Professional Identity Work During Their Teacher-Education Doctoral Studies.” Research in the Teaching of English 52 (2): 181–210. https://doi.org/10.58680/rte201729379

- Lawrence, E. C., M. L. Carvour, C. Camarata, E. Andarsio, and M. W. Rabow. 2020. “Requiring the Healer’s Art Curriculum to Promote Professional Identity Formation Among Medical Students.” Journal of Medical Humanities 41 (4): 531–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-020-09649-z.

- Mackay, M. 2017. “Identity Formation: Professional Development in Practice Strengthens a Sense of Self.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (6): 1056–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1076780.

- Mahmoudi-Gahrouei, V., M. Tavakoli, and D. Hamman. 2016. “Understanding What Is Possible Across a Career: Professional Identity Development Beyond Transition to Teaching.” Asia Pacific Education Review 17 (4): 581–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-016-9457-2.

- Marcia, J. 1980. “Identity in Adolescence.” In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, edited by J. Alderson, 159–87. New York: Wiley.

- McCann, C. M., E. Beddoe, K. McCormick, P. Huggard, S. Kedge, C. Adamson, and J. Huggard. 2013. “Resilience in the Health Professions: A Review of Recent Literature.” International Journal of Wellbeing 3 (1): 60–81. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v3i1.4.

- Merlo, G., H. Ryu, T. B. Harris, and J. Coverdale. 2021. “MPRO: A Professionalism Curriculum to Enhance the Professional Identity Formation of University Premedical Students.” Medical Education Online 26 (1): 1886224. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2021.1886224.

- Moradkhani, S., and M. Ebadijalal. 2021. “Professional Identity Development of Iranian EFL Teachers: Workplace Conflicts and Identity Fluctuations.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021.1988605

- Moss, J. M., D. M. Gibson, and C. T. Dollarhide. 2014. “Professional Identity Development: A Grounded Theory of Transformational Tasks of Counselors.” Journal of Counseling & Development 92 (1): 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00124.x.

- Nadelson, L. S., S. Paterson McGuire, K. A. Davis, A. Farid, K. K. Hardy, Y.-C. Hsu, U. Kaiser, R. Nagarajan, and S. Wang. 2017. “Am I a STEM Professional? Documenting STEM Student Professional Identity Development.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (4): 701–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1070819.

- Nazari, M., M. A. Miri, and J. Golzar. 2021. “Challenges of Second Language Teachers’ Professional Identity Construction: Voices from Afghanistan.” TESOL Journal 12 (3). https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.587.

- Nicholson, J., and H. Maniates. 2016. “Recognizing Postmodern Intersectional Identities in Leadership for Early Childhood.” Early Years 36 (1): 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2015.1080667.

- Noble, C., I. Coombes, L. Nissen, P. N. Shaw, and A. Clavarino. 2015. “Making the Transition from Pharmacy Student to Pharmacist: Australian Interns’ Perceptions of Professional Identity Formation.” International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 23 (4): 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpp.12155.

- Nyström, S. 2009. “The Dynamics of Professional Identity Formation: Graduates’ Transitions from Higher Education to Working Life.” Vocations and Learning 2 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-008-9014-1.

- Park, J. J., Y.-C. Chuang, and E. S. Hald. 2018. “Identifying Key Influencers of Professional Identity Development of Asian International STEM Graduate Students in the United States.” The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 27 (2): 145–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0373-6.

- Pillen, M., D. Beijaard, and P. den Brok. 2013. “Tensions in Beginning Teachers’ Professional Identity Development, Accompanying Feelings and Coping Strategies.” European Journal of Teacher Education 36 (3): 240–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2012.696192.

- Rabow, M. W., J. Wrubel, and R. N. Remen. 2007. “Authentic Community as an Educational Strategy for Advancing Professionalism: A National Evaluation of the Healer’s Art Course.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 22 (10): 1422–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0274-5.

- Rodrigues, F., and M. J. Mogarro. 2019. “Student Teachers’ Professional Identity: A Review of Research Contributions.” Educational Research Review 28 (November): 100286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100286.

- Sarraf-Yazdi, S., Y. N. Teo, A. E. H. How, Y. H. Teo, S. Goh, C. S. Kow, W. Y. Lam, et al. 2021. “A Scoping Review of Professional Identity Formation in Undergraduate Medical Education.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 36 (11): 3511–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07024-9.

- Sawatsky, A. P., H. C. Nordhues, S. P. Merry, M. U. Bashir, and F. W. Hafferty. 2018. “Transformative Learning and Professional Identity Formation During International Health Electives: A Qualitative Study Using Grounded Theory.” Academic Medicine 93 (9): 1381–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002230.

- Sawatsky, A. P., W. L. Santivasi, H. C. Nordhues, B. E. Vaa, J. T. Ratelle, T. J. Beckman, and F. W. Hafferty. 2020. “Autonomy and Professional Identity Formation in Residency Training: A Qualitative Study.” Medical Education 54 (7): 616–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14073.

- Shapiro, J., J. McMullin, G. Miotto, T. Nguyen, A. Hurria, and M. A. Nguyen. 2021. “Medical Students’ Creation of Original Poetry, Comics, and Masks to Explore Professional Identity Formation.” Journal of Medical Humanities 42 (4): 603–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-021-09713-2.

- Shiozawa, T., M. Glauben, M. Banzhaf, J. Griewatz, B. Hirt, S. Zipfel, M. Lammerding-Koeppel, and A. Herrmann-Werner. 2019. “An Insight Into Professional Identity Formation: Qualitative Analyses of Two Reflection Interventions During the Dissection Course.” Anatomical Sciences Education, ase.1917. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1917.

- Slay, H. S., and D. A. Smith. 2011. “Professional Identity Construction: Using Narrative to Understand the Negotiation of Professional and Stigmatized Cultural Identities.” Human Relations 64 (1): 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710384290.

- Sveningsson, S., and M. Alvesson. 2003. “Managing Managerial Identities: Organizational Fragmentation, Discourse and Identity Struggle.” Human Relations 56 (10): 1163–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035610001.

- Tan, C. P., H. T. Van der Molen, and H. G. Schmidt. 2017. “A Measure of Professional Identity Development for Professional Education.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (8): 1504–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1111322.

- Tomer, G., and S. K. Mishra. 2016. “Professional Identity Construction among Software Engineering Students: A Study in India.” Information Technology & People 29 (1): 146–72. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-10-2013-0181.

- Tomlinson, M., and D. Jackson. 2021. “Professional Identity Formation in Contemporary Higher Education Students.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (4): 885–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1659763.

- Torraco, R. J. 2005. “Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples.” Human Resource Development Review 4 (3): 356–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283.

- Toubassi, D., C. Schenker, M. Roberts, and M. Forte. 2023. “Professional Identity Formation: Linking Meaning to Well-Being.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 28 (1): 305–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10146-2.

- Tracey, M. W., and A. Hutchinson. 2018. “Reflection and Professional Identity Development in Design Education.” International Journal of Technology and Design Education 28 (1): 263–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-016-9380-1.

- Trede, F., R. Macklin, and D. Bridges. 2012. “Professional Identity Development: A Review of the Higher Education Literature.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (3): 365–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.521237.

- Wald, H. S. 2015. “Professional Identity (Trans)Formation in Medical Education.” Academic Medicine 90 (6): 701–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000731.

- Wilkins, E. B. 2020. “Facilitating Professional Identity Development in Healthcare Education.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning 2020 (162): 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20391.

- Winkler, I., S. C. Reissner, and R. Cascón-Pereira, eds. 2023. Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Identity In and Around Organizations: Usual Suspects and Beyond. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Wyatt, T. R., D. Balmer, N. Rockich-Winston, C. J. Chow, J. Richards, and Z. Zaidi. 2021. “‘Whispers and Shadows’: A Critical Review of the Professional Identity Literature with Respect to Minority Physicians.” Medical Education 55 (2): 148–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14295.

- Wyatt, T. R., N. Rockich-Winston, D. J. White, and T. R. Taylor. 2021. “‘Changing the Narrative’: A Study on Professional Identity Formation among Black/African American Physicians in the U.S.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 26 (1): 183–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09978-7.

- Zaneb, H., and E. Armitage-Chan. 2022. “Professional Identity of Pakistani Veterinary Students: Conceptualization and Negotiation.” Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 50: e20220064. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme-2022-0064.