ABSTRACT

Artificial intelligence (AI) may be the new-new-norm in a post-pandemic learning environment. There is a growing number of university students using AI like ChatGPT and Bard to support their academic experience. Much of the AI in higher education research to date has focused on academic integrity and matters of authorship; yet, there may be unintended consequences beyond these concerns for students. That is, there may be people who reduce their formal social interactions while using these tools. This study evaluates 387 university students and their relationship to – and with – artificial intelligence large-language model-based tools. Using structural equation modelling, the study finds evidence that while AI chatbots designed for information provision may be associated with student performance, when social support, psychological wellbeing, loneliness, and sense of belonging are considered it has a net negative effect on achievement. This study tests an AI-specific form of social support, and the cost it may pose to student success, wellbeing, and retention. Indeed, while AI chatbot usage may be associated with poorer social outcomes, human-substitution activity that may be occurring when a student chooses to seek support from an AI rather than a human (e.g. a librarian, professor, or student advisor) may pose interesting learning and teaching policy implications. We explore the implications of this from the lens of student success and belonging.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been around for the past 70 years, yet it has only recently begun integrating into everyday life including educational contexts. While AI use has become more common over the last decade or so, it could be argued that there was a significant change in November, 2022 with the introduction of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, a conversational chatbot based on generative AI and a large language model (LLM) (Hu Citation2023). The advancement is notable, marking a substantial shift in the uptake and technological adoption of AI in higher education with significant implications for teaching, learning, and social connections within universities (Cotton, Cotton, and Shipway Citation2023; Ma and Siau Citation2018).

Since the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the introduction of online technologies in higher education has accelerated (Bartolic et al. Citation2022). The preparedness of academics and students to engage with new technologies in learning and teaching grew – out of necessity – and has not abated (Bearman, Ryan, and Ajjawi Citation2023). The technological-enhanced education forces brought about by a need for emergency remote teaching may have supported acceptance and readiness of emergent generative AI technologies. In 2020, a working paper by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD: Vincent-Lancrin and van der Vlies Citation2020) comments on the pervasive nature of artificial intelligence and a need to better prepare students for the disruption it will likely cause. Now, academics and students grapple with technological affordances of generative AI from grading and feedback support to reference simplification, idea generation, and graphic design support (Escotet Citation2023).

Despite its rapid integration into higher education, most research has focused on the academic costs and benefits of the AI in education from a learner and academic achievement perspective (Bond et al., Citation2024; Perkins Citation2023). For example, the extent to which AI is linked with student e-cheating is prominent in the emergent literature (Ivanov Citation2023; Dawson Citation2020). Concerns around increased AI usage extend to psychological effects, including heightened loneliness, a shift in the sense of belonging from human connections to AI, and social withdrawal are nascent in the literature (e.g. de Graaf Citation2016; Sepahpour Citation2020; Xie, Pentina, and Hancock Citation2023), despite some valid arguments emerging. Some evidence indicates AI can reduce loneliness in some contexts (e.g. Brandtzaeg, Skjuve, and Følstad Citation2022; Dosovitsky and Bunge Citation2021; Loveys et al. Citation2019; Sullivan, Nyawa, and Fosso Wamba Citation2023), but there is limited research on the broader implications of AI chatbot interaction particularly in respect to social support and belonging. Some scholars are calling for more research into the AI-human collaboration (Gao et al., Citation2024; Nguyen et al., Citation2024). Herein lies the key research objective for this study. The main aim of this study is to investigate the effect of ChatGPT use on perceived social support, belonging, and loneliness contrasted to human interactions. To begin with, we seek to unpack key background literature on artificial intelligence, sense of belonging and wellbeing, and loneliness and retention.

Background

Artificial intelligence and chatbots

AI chatbots serve a variety of functions. AI has been utilised to assist daily functioning, as a social companion, and in aid of work and study (Rudolph, Tan, and Tan Citation2023). AI chatbots can also assist university students and staff in academic areas and emotional support, with some evidence of higher performance compared to instructor-support (Eager and Brunton, Citation2023; Essel et al. Citation2022). An AI chatbot named Woebot was designed to deliver cognitive behavioural therapy found improvements in student wellbeing in a cost-effective and accessible manner (Fulmer et al. Citation2018). Similarly, in a study by Liu et al. (Citation2022), AI chatbots improved student depression symptoms when designed as a self-help treatment in the real world. Yang and Evans (Citation2019) emphasised despite benefits with AI chatbots in education there are also technical limitations with the existing system that require greater integration.

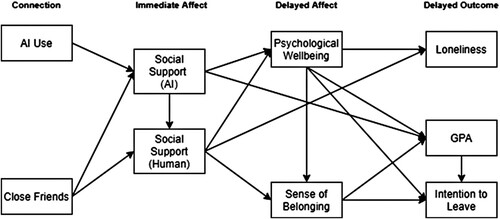

In this study, we distinguish between two types of AI. The first are chatbots designed for academic support with conversational knowledge exchange as the primary output (e.g. ChatGPT). The second are chatbots designed for social support and companionship (e.g. Replika). In the context of higher education learning and teaching, the former is having a significant impact on learning and teaching (Bearman, Ryan, and Ajjawi Citation2023; Lodge, de Barba, & Broadbent, Citation2023) and the latter is less prominent. Despite chatbots used in education being designed for academic support, their impact on the social conditions of students is theoretically noticeable. That is, when students engage in an online tool in place of a human-to-human interaction, the implications of the substitution effect is not yet known. There is limited research on the effects of AI chatbots and students’ feelings of loneliness and belonging, with some studies conflicting. As we explore below, we argue that this may be a limiting factor in examining the complexity of how students use AI and without contextual awareness of the cost of deeper AI use. In this study, we build on previous social psychology research (e.g. Pani, Crawford, and Allen Citation2023) to propose that while AI use may influence performance, that once the human cost is accounted for, it is unlikely to have a long-term benefit on performance (see ). In the next sections, we highlight the concepts and relationships across the immediate and delayed affect and delayed outcome.

AI chatbots as social support (immediate affect)

Artificial intelligence has, so far, suggested some relationships to capacity for social support and companionship, although confidence in using the tools varies among students (Kelly, Sullivan, and Strampel, Citation2023). Social support is the extent to which an individual perceives they are supported by key social actors in their lives: significant other, friends, and family (Zimet et al. Citation1988). In this study, we also develop a subscale for artificial intelligence. This is a key area to explore because the literature is unclear on the prolonged effects of AI chatbot use, given questions of the AI postdigital social contract are being reflected on in AI usage (Hayes et al., Citation2024). One concern is that if emotional connections with AI are accepted, human-to-human relationships may be substituted (de Graaf Citation2016). It is important to distinguish between AI chatbots designed explicitly for social support and wellbeing, such as therapeutic or counselling bots, and unmonitored chatbots like ChatGPT, which lack specific design for emotional support. Increased usage of unmonitored AI chatbots may result in adverse psychological effects such as social withdrawal, isolation, or AI addiction (Sepahpour Citation2020). One study using AI chatbots to reduce loneliness found that over time participants developed a dependency on them (Cresswell, Cunningham-Burley, and Sheikh Citation2018), and likely lowered their capacity and confidence in building new human relationships. Another study pointed out that individuals who were more likely to engage in problematic usage of AI chatbots were those who were socially anxious (Hu, Mao, and Kim Citation2023). This differentiation underlines the potential for specific, designed-for-purpose AI chatbots to offer beneficial social support, contrasting with the broader use of general AI chatbots, which may not foster the same level of emotional wellbeing. For example, in a launch of Quantic’s AI-powered student advisor, there are cases made for the AI to help with definitions, concepts, practice exams, checking a formula, and checking graduation progress, but makes no mention to supporting students as humans.

Individuals who lack human companionship are more vulnerable to developing an AI-relationship in place of their human-human relationships (Laestadius et al. Citation2022; Xie, Pentina, and Hancock Citation2023). Social support is the comfort or help from others to assist in coping (Pearson Citation1986). Social support can be provided in an array of ways. For example, emotional and moral support can be given to a grieving friend, through presence. Perceptions and expectations of social support can change for individuals, in particular their awareness of social cues (Schall, Wallace, and Chhuon Citation2016). The role of AI in providing social support must be critically examined, especially considering the unique characteristics and intended uses of different types of chatbots. It is hypothesised that, in our model, AI use will predict perceived social support from AIs, but not human-related social support, and indeed that AI use through AI-social support will have a negative effect on traditional social support.

Sense of belonging and psychological wellbeing (delayed affect)

University students display higher wellbeing when they have a greater sense of belonging (Gopalan, Linden-Carmichael, and Lanza Citation2021). When transitioning to higher education, students are entering a new chapter of their lives, are challenged to adapt to new academic settings make new friends (Kift, Nelson, and Clarke Citation2010; van Rooij, Jansen, and van de Grift Citation2017), while maintaining old ones (Diehl et al. Citation2018). The pandemic significantly contributed to students’ reduced sense of belonging, as universities were planning and piloting alternative platforms for remote learning, following increased rates of anxiety directly related to loneliness (Tice et al. Citation2021). Given that, on average, only half of students feel like they belong, novel interventions focusing on improving students’ sense of belonging is needed.

Belonging is a dynamic construct that creates change in emotions and behaviours. A sense of belonging is a subjective feeling of connection to others, places, and/or experiences. The experience of belonging not only differs between people, but also fluctuates over time, and in different contexts (Baumeister and Leary Citation1995). A sense of belonging in university students has been adapted and described as a student feeling valued, accepted, and included (Maunder Citation2018). A strong sense of belonging is important in academia because it reinforces motivation, increases achievement, attention, engagement, retention, resilience, self-esteem, and enjoyment of learning (Gomes et al. Citation2021; Meehan and Howells Citation2019; Ulmanen et al. Citation2016). Students who belong tend to experience greater positive feelings toward their education, have higher self-efficacy, increased help-seeking behaviour and procrastinate less (Gillen-O’Neel Citation2021). One study showed that strong predictors of student belonging in an Australian context included overall perceptions of experience, support for settling into the university, and student interaction (Crawford et al. Citation2023).

Starting university, the first-year experience anxiety often results in lower psychological wellbeing, leaving them more vulnerable (Bewick et al. Citation2010). Psychological wellbeing is the presence of positive emotions and feelings, rather than negative feelings like anxiety or symptoms of depression. In attempts to improve wellbeing, some conversational AIs have been designed to provide affective support. One study showed students were quite willing to engage with their AI for psychological support, and psychological need fulfilment (Pesonen Citation2021). While some scholars believe AI is useful to improve wellbeing (Fulmer et al. Citation2018), other perspectives identify AI-therapist limitations (Bell, Wood, and Sarkar Citation2019). There are questions emergent regarding the AI to student relationship regarding how it impacts social connection, support, and belonging.

Loneliness, retention, and student success (outcome)

In the model proposed, there are three primary outcomes related to student success (e.g. self-report Grade Performance Average), persistence (e.g. retention), and a form of psychological success (e.g. student loneliness). These are significant challenges effecting universities, with one in three adults experience loneliness globally (Varrella Citation2021), and 1 in 4 Australian students withdrawing from studies.

To clarify, loneliness is often caused by a lack of emotional social support and can occur at any time (Stickley et al. Citation2015; Park et al. Citation2020). Additionally, individuals more vulnerable to experiencing loneliness are those who live rurally, older individuals who live alone, adolescents and students. AI chatbots may have a reinforcing effect for lonely people to disconnect from human relationships and encourage human-chatbot relationships. In a recent study, Xie and colleagues (Citation2023) found that loneliness predicted increased usage of social AI chatbots. In Dosovitsky and Bunge (Citation2021) when participants were asked if they would recommend the chatbot to friends, some reported having no friends to recommend the chatbot to (Dosovitsky and Bunge Citation2021). Because meaningful connection is a fundamental human and psychological need (Baumeister and Leary Citation1995), lonely people may seek out AI chatbots in hopes of developing a meaningful relationship (Brunet-Gouet, Vidal, and Roux Citation2023). That is, while quality human connections may support individuals to feel connected and.

Despite these concerns, there have been encouraging findings on the role AI plays in student success (e.g. academic performance and passing subjects). Students have reported AI assistant tools in the classrooms can be responsive and adaptable, and improved their engagement (Chen et al. Citation2023). Similarly, Alneyadi and Wardat (Citation2023) provide early evidence that ChatGPT helped students perform better on tests and helped with learning and explanations. Contrary to the positive outcomes of enhanced student success, Wang et al. (Citation2023) contest that AI is useful for assistance, but cannot replace human teachers. Pani, Crawford, and Allen (Citation2023) also argue that while short term benefits may be observed in belonging and social support, longer-term effects may invert as individuals forgo connection building activities for convenience of AI support. That is, there is growing evidence on the immediate effect of AI chatbots on student success and academic achievement, but these are usually evidenced with a direct relationship rather than seeking to understand the social and affective interactions that are also occurring.

Student retention has remained a prominent and key component of educational policy (Kahu and Nelson Citation2018; Tinto Citation1990). A key measure of institutional success is whether it can support its students to begin, continue, and complete their tertiary studies. Student success and retention seem intertwined, with confidence gained from passing subjects and doing well likely contributing to intentions to stay in an academic programme (Fowler and Boylan Citation2010). Similar relationships exist between sense of belonging and retention (O’Keeffe Citation2013; Pedler, Willis, and Nieuwoudt Citation2022), and between psychological wellbeing and retention (Kalkbrenner, Jolley, and Hays Citation2021). That is, when students feel resilient and are performing well, they are likely to persist and continue to study. Yet, the impact of generative AI on these key outcomes beyond academic performance is unclear. This study proposes to further explore these interactions.

Method

Hypothesis development

We, adopting a social psychology lens, theorise that quality close friends and social support, through wellbeing and belonging contribute to meaningful outcomes of lower loneliness, higher student success, and higher retention; a perspective consistent with the literature (e.g. Kahu and Nelson Citation2018; Mishra Citation2020; Stevens Citation2001). The introduction of AI in university life is likely to have mixed effects on student success (Chen et al. Citation2023), but has promise as a supplement to traditional teaching approaches; but not in replacement of human learning environments. We theorise a model where AI may have a replacement effect on the social psychological process that leads to worse outcomes regarding loneliness, success, and retention. In this model, our focus is on artificial intelligence tools used for academic purposes (e.g. ChatGPT or Bard), not social companionship tools (e.g. Replika). The latter, of which, Park et al. (Citation2023) in their Smallville experiment, evidence generative agents capable of providing emergent rather than pre-programmed social support to each other. In this study, the aim is to understand the unseen consequences (or benefits) of engaging with generative AI for academic reasons.

Procedure

University students (18 years and over) were invited to participate by a website link or QR code directing participants to the participant information sheet and survey hosted on Qualtrics XM over three months, approved by Monash University Human Ethics Committee (#38002). The target sample size was 385 (calculated assuming 235 million student population, with a 95 percent confidence interval: UNESCO Citation2023). Students were sampled by convenience and geographic-stratified sampling (Tyrer and Heyman Citation2016); that is, every effort was made to gain diverse student views on the topic to minimise possible bias influenced by diverse global adoption rates.

Measures

The measures reported below are all previously established scales – except for artificial intelligence use – and have been used in contexts similar to this study. The survey included demographic questions (age, gender, field of study, level of study, country of residence, ethnicity, income, perceived socioeconomic status and number of close friends), AI/ChatGPT usage (number of conversations initiated with AI, number of replies in each conversation, the length of each conversation, and the date first used ChatGPT), and their perceived grade point average (GPA) on a 5-point scale from ‘failing’ to ‘excellent’.

Artificial intelligence use. To measure student artificial intelligence usage, we asked students to self-report their number of weekly AI conversations, the number of AI replies each conversation had, and the length of these conversations in minutes. The three items loaded well, and had suitable reliability (α = .60). These items required manual parsing to convert to consistent language, as these questions were asked as short-text boxes to allow for variance in student language across contexts.

Perceived social support. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) was used to measure perceived social support by assessing support on three subscales; friends, family, and significant others (Zimet et al. Citation1988). An adapted version of the MSPSS was also created for this study using the top loading item from each subscale, which were adapted to relate to perceived social support from ChatGPT (items 4, 10, and 12). The adapted scale showed high reliability (α = .88).

Loneliness. Student subjective feelings of loneliness were assessed using the UCLA Loneliness Scale V3, with high reliability (α = .86; Russell Citation1996).

Sense of belonging. The Scale for Sense of Belonging and Support was adapted to align to the university context by measuring feelings of being comfortable, part of, committed, supported, and accepted by a students’ university (α = .90; Anderson-Butcher and Conroy Citation2002).

Psychological wellbeing. The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) was used to assess students perceived psychological wellbeing. This scale showed high reliability .83, high sensitivity (80.5%) and specificity (80.2%) (Kerper et al. Citation2014).

Intention to leave. An adaptation of the Job Turnover Scale was used to measure participant retention in university. This scale has proven high internal consistency (α = .89; Sjöberg and Sverke Citation2000). This adaptation measured student intent to complete their degree and stay enrolled on a 5-point Likert scale (Knox et al. Citation2020).

Data analysis

IBM SPSS version 28.0 was used to run exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on the original MSPSS, the adapted ChatGPT MSPSS, the UCLA-3, the adapted scale for sense of belonging, the adapted retention scale, and the PHQ-4. The EFA ensured validity of each scale was sufficient, and IBM’s AMOS was used to conduct maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which presented similar results with individual loadings exceeding .3. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed across the variables in the study The quantity of ChatGPT usage was measured by the number of conversions initiated with ChatGPT per week. The quality of AI usage was measured by the number of replies ChatGPT would provide and length on each conversation, measured in minutes. Reliability of measures was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha. The final analysis was performed using AMOS 26.0 to conduct structural equation modelling. We ensured the model fit through the following parameters: The root mean square of error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardised root mean squared residual (SRMR), below .08, preferably below .05. The confirmatory fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were targeted to be below .9 and the Chi-Squared/Degree of Freedom (X2/df) below five as per Crawford and Kelder (Citation2019).

Sample

In total, 512 participants began the survey. Five were excluded as they did not consent to the study, 117 were removed as they entered less than 50 percent of the survey and two were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The final sample consisted of 387 participants, with a standard error of 2.55 percent. Participants demographic profiles are displayed in , the medium age of participants was 25 (M = 27.32, SD = 7.78) ranging from 18 to 63.

Table 1. Sample demographics.

Results

Model specification

Structural equation modelling was used to evaluate relationships from AI usage to retention and student success through measures of social support and connection. Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure multicollinearity and normality assumptions were not violated. The primary models (Model 1 and 2, ) were used to test the theorised relationships in .

Table 2. Competing models for the structural equation model.

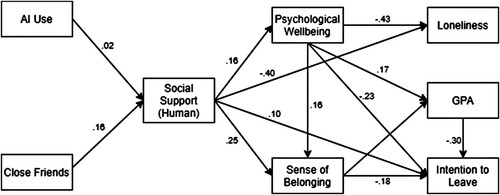

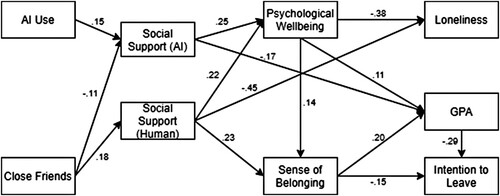

Model 1 demonstrated strong model fit, but the relationship from AI usage and number of friends to overall social support was negligible, and the relationship between AI usage and overall social support was insignificant (see ). This posed two analytical questions: (a) would the model be stronger if AI and human social support were treated as independent, but related constructs, and (b) would the model be stronger if all AI elements were removed.

In Model 2, the AI and human social supports were separated identifying all relationships were significant (noting that AI usage to human social support was insignificant and removed). This model showed reasonably strong model fit, but less so than Model 1; however, AI usage was a significant predictor of AI social support, albeit negligible. In this model, AI and human social support are treated as separate constructs. AI usage is a significant predictor of AI social support, but the overall model fit is slightly weaker compared to Model 1 ().

Figure 3. AI and human mediated effects on loneliness, GPA, and retention when AI-based social support is independent of human support.

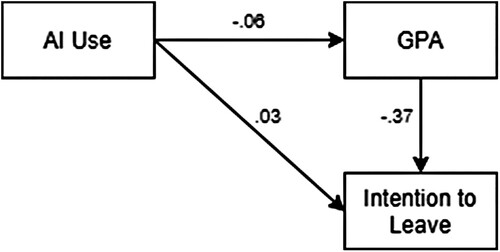

In Model 3, we tested whether AI usage had a material relationship directly to retention and self disclosed grade performance. This model showed strong model fit, but all relationships were insignificant (p > .05, see ). This indicates initially, that for AI usage to have an effect on performance and retention, it is mediated through measures of social support and connection.

In the remaining tests, we evaluated the model performance of three additional models not displayed. In Model 4, we re-evaluated what happened when we removed AI usage from the model. This showed slightly worse performance than the original model, although it did show an effect was evident, with all relationships significant. In Model 5, we continued to remove AI-based social support and AI usage, to make the model AI-blind. This model showed better performance than Model 4, but still worse than the original model. Finally, in Model 6, we re-evaluated Model 2 with the AI usage removed. In this model, the assumption was that AI social support was different to human social support, but that our proximal measure of AI usage was not a contributor. This model, outside of Model 1, was the most performant; and indicates that there is likely an underlying AI effect as a cause of student success and retention; it is possible a more refined scale of AI usage would help elucidate the relationship more clearly.

Discussion

The current study investigated the impact of AI chatbots on loneliness, student success, and retention through sense of belonging, social support, and student wellbeing. The study found that AI chatbot use was positively related to feeling socially supported by AI which was related to self-reported academic performance directly and intention to leave indirectly, yet showed mixed effects on psychosocial factors like loneliness and belonging. Overall, the results found that AI chatbots have both benefits and limitations for university students, particularly when used as a source of social support.

When AI and humans collide

AI chatbot usage was found to increase university student feelings of social support from AI in the short-term. When university students used AI more frequently they reported that they felt a greater sense of social support from the AI. This is contrary to Kim, Merrill, and Collins (Citation2021), who found that participants preferred functional AIs (AI for tasks) over social AIs (AI for companionship) due to social interactions and support potentially being already satisfied elsewhere. Xie, Pentina, and Hancock (Citation2023) raised concerns that prolonged exposure to AI may lead to dependency, especially when lacking human companionship. In the current study, the effect AI use had on feelings of AI-social support were like the effect close friends had on human-social support. This suggests that some individuals may lack social support from human relationships in real life (‘IRL’), and opt to fulfil this need gap with AI.

Interestingly, students with stronger perceptions of AI social support felt less socially supported by AI. This finding suggests that individuals who have fewer friends may seek out more opportunities to feel more connected and supported by AI. This is consistent with Dosovitsky and Bunge (Citation2021) who found some AI users had strong relationships with their AI when they reported not having friends. This could be explained by Brandtzaeg, Skjuve, and Følstad (Citation2022) who suggested that AI chatbots and people can indeed be ‘friends’. These studies provide evidence toward the ethical concerns for AI replacing human-to-human relationships, social withdrawal, and AI dependency (de Graaf Citation2016; Sepahpour Citation2020). Our study suggested that university students with fewer friends tend to feel more socially supported by AI. It is plausible that these individuals seek to ameliorate their social support through alternative means such as AI or that AI-human connections can lead to some people withdrawing socially.

While encouraging students’ social support is generally supported in higher education, it is critical to evaluate the cost of using AI to provide such support. Our research identified that when students’ social support from AI was greater, social support from other people was lower. Despite some scholars arguing that AI replacing other people for social connection for mental health problems could never happen (Brown and Halpern Citation2021), current findings demonstrate a potential trend that as AI usage increases some individuals will use AI as a primary source of social support. Ta et al. (Citation2020) reported that AI chatbots can be a promising source of social support and companionship, but there is disagreement in the literature. For instance, Turkle (Citation2011) advocates that AI only gives the illusion of companionship and is not a genuine friendship. It is evident from presenting findings that AI and other people can have a relationship and that some individuals are already using AI chatbots as a form of social support. However, it is important for leaders, policymakers, higher education staff and researchers to question whether AI should be used for social support, just because it can, especially when it could be at the expense of diminishing social support from friends and family? Our finding showed the relationship between other people and AI chatbots strengthening, while human relationships weaken, possibly without users even realising.

AI indirect effects on loneliness and wellbeing

Our present findings showed that being socially supported by friends and family was associated with reduced loneliness in university students, whereas students who reported having greater social support from AI were lonelier. Social support mediated the relationship between loneliness and AI usage, suggesting that AI usage can increase loneliness but only if the person feels socially supported by AI. These findings are partially consistent with Xie, Pentina, and Hancock (Citation2023), who suggested that greater AI usage could lead to increased loneliness, however they did not consider the impact of the student’s perception regarding being socially supported by AI. It is unclear if this perception motivates students to use AI more for social support, or the other way around.

In addition, our findings suggested that students who felt socially supported by AI reported seemed to experience similar effects for psychological wellbeing as those supported by human social support. This is partially consistent with previous research that showed people with social anxiety were more likely to engage in problematic use of AI chatbots (Hu, Mao, and Kim Citation2023). Indicating that university students may be turning to AI for social support because of mental health problems or to alleviate a lack of social support. It appears that university students can experience both negative and positive outcomes when using AI.

AI, student success, and retention

In our study, no significant direct effect was found between AI usage, perceived grade average, and the intention to leave university. However, an indirect effect was observed through the mediating variables of social support, wellbeing, and sense of belonging. Students who reported feeling socially supported by other people reported higher grade performance and were less willing to leave university than those who reported being socially supported by AI. This may indicate that when university students are well connected to others, as opposed to AI, they may be more likely to have greater academic success. No previous research on student retention and AI usage exists, however, one study showed that retention intention increased when staff used AI assistance (Wang et al. Citation2022), which is contrary to our findings. Also inconsistent with our findings, Ouyang, Zheng, and Jiao (Citation2022), found that AI usage can promote academic performance. Our results align with Seo et al. (Citation2021), warning about the potentially negative impact AI could have on grades, underscoring the need for further insight. The results of the current study indicate that university students using AI tend to experience diminished student success and retention, but only if they feel socially supported by AI. However, this relationship has yet to be further explored in the research. This finding warrants further research to fully understand the implications.

As expected, this study affirms that students who feel more socially supported by other people have a greater sense of belonging, wellbeing, reduced loneliness, and a reduced willingness to leave university compared to those who feel socially supported by AI. This could be explained by past findings that suggest social support improves cognition (Kelly et al. Citation2017), lessens psychosocial effects of depression and stress (Lee and Goldstein Citation2016), and correlates to university retention (Nieuwoudt and Pedler Citation2023). Notably, these psychosocial and academic factors contribute to AI usage only through feeling socially supported by AI. These findings contribute research on the importance of perceived social support by other people in university students to succeed and flourish at their university and in their wellbeing.

Strengths and limitations

This research provides novel evidence about the relationship between ChatGPT use and psychosocial outcomes in university students, a topic with limited empirical literature. The research findings address an obvious gap in the literature regarding psychological outcomes with AI usage and has the potential to serve as foundational work for this emerging field. However, these preliminary contributions should be viewed considering the study's limitations. At the time of data collection, ChatGPT was a relatively new technology, having been available to the public for less than nine months. In addition, there was a limited recruitment timeframe which impacted on sample size. Furthermore, belonging and loneliness fluctuate as a daily experience (Gillen-O’Neel Citation2021), and the current study only measured these factors at one time point.

Implications and future directions

These findings accentuate the importance of social support from friends and family, particularly in university students. As increased social support improves wellbeing and belonging, which improves student grade performance and university retention, higher education institutions should promote face-to-face social support, peer networks, and social opportunities for students to engage with their peers and build social connections to optimise their wellbeing and academic performance. Future research could explore the relationship between types of social support (family, friends, and significant others) and AI usage.

In our study, the longest amount of time a participant used ChatGPT for was a maximum of eight months, it was found that length of time spent using ChatGPT (quantity) was correlated with usage quality. As the study found that extended use of ChatGPT correlated with increased use, it raises questions about the long-term implications of such sustained usage and psychosocial effects, in particular social support. Our finding that extended use of ChatGPT was associated with increased usage also presents an opportunity for future research, particularly to explore the long-term implications of sustained usage with a focus on social support. Given that short-term AI use demonstrated a relationship with feelings of social support from AI, future studies could explore changes with long-term AI use.

Conclusions

Taken together, this study provides new and preliminary insights into the relationship between ChatGPT usage and social support from AI. The study reiterated the importance of social support for university students and its impact on wellbeing, sense of belonging, loneliness, and intention to leave university. When individuals feel more socially supported from AI, they feel less supported from other people. Social support also played a mediating role in AI usage in poorer grade performance and intention to leave university. This study found that social support from peers and other people plays a significant role for university students in their sense of belonging, as well as preliminary insight into student’s’ use of AI and their psychosocial outcomes, potentially paving the way for future studies in this emerging field of research.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Natalie Mizzi, who provided support to the research team through administration and editing from inception to final submission. The authors also disclose no use of ChatGPT or other artificial intelligence tools were used during the development of writing of this article beyond a chatbot exchange to sense-test the items developed for the AI-Social Support model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alneyadi, S., and Y. Wardat. 2023. “ChatGPT: Revolutionizing Student Achievement in the Electronic Magnetism Unit for Eleventh-Grade Students in Emirates Schools.” Contemporary Educational Technology 15 (4): ep448. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/13417.

- Anderson-Butcher, D., and D. E. Conroy. 2002. “Factorial and Criterion Validity of Scores of a Measure of Belonging in Youth Development Programs.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 62 (5): 857–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316402236882.

- Bartolic, S. K., D. Boud, J. Agapito, D. Verpoorten, S. Williams, L. Lutze-Mann, U. Matzat, et al. 2022. “A Multi-Institutional Assessment of Changes in Higher Education Teaching and Learning in the Face of COVID-19.” Educational Review 74 (3): 517–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1955830.

- Baumeister, R. F., and M. R. Leary. 1995. “The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation.” Psychological Bulletin 117 (3): 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

- Bearman, M., J. Ryan, and R. Ajjawi. 2023. “Discourses of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A Critical Literature Review.” Higher Education 86 (2): 369–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00937-2.

- Bell, S., C. Wood, and A. Sarkar. 2019. Perceptions of Chatbots in Therapy.” Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290607.3313072.

- Bewick, B., G. Koutsopoulou, J. Miles, E. Slaa, and M. Barkham. 2010. “Changes in Undergraduate Students’ Psychological Well-Being as they Progress through University.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (6): 633–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903216643.

- Bond, Melissa, Hassan Khosravi, Maarten De Laat, Nina Bergdahl, Violeta Negrea, Emily Oxley, Phuong Pham, Sin Wang Chong, and George Siemens. 2024. “A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: a call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 21 (1): 6286. http://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00436-z.

- Brandtzaeg, P. B., M. Skjuve, and A. Følstad. 2022. “My AI Friend: How Users of a Social Chatbot Understand Their Human–AI Friendship.” Human Communication Research 48 (3): 404–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqac008.

- Brown, J. E. H., and J. Halpern. 2021. “AI Chatbots Cannot Replace Human Interactions in the Pursuit of More Inclusive Mental Healthcare.” SSM - Mental Health 1: 100017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100017.

- Brunet-Gouet, E., N. Vidal, and P. Roux. 2023. Do Conversational Agents have a Theory of Mind? A Single Case Study of ChatGPT with the Hinting, False Beliefs and False Photographs, and Strange Stories Paradigms. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7637476.

- Chen, Y., S. Jensen, L. J. Albert, S. Gupta, and T. Lee. 2023. “Artificial Intelligence (AI) Student Assistants in the Classroom: Designing Chatbots to Support Student Success.” Information Systems Frontiers 25 (1): 161–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-022-10291-4.

- Cotton, D. R. E., P. A. Cotton, and J. R. Shipway. 2023. “Chatting and Cheating: Ensuring Academic Integrity in the era of ChatGPT.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 61 (2): 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2023.2190148.

- Crawford, J., K.-A. Allen, T. Sanders, R. Baumeister, P. D. Parker, C. Saunders, and D. M. Tice. 2023. “Sense of Belonging in Higher Education Students: An Australian Longitudinal Study from 2013 to 2019.” Studies in Higher Education 49 (3): 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2238006.

- Crawford, J. A., and J.-A. Kelder. 2019. “Do We Measure Leadership Effectively? Articulating and Evaluating Scale Development Psychometrics for Best Practice.” The Leadership Quarterly 30 (1): 133–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.001.

- Cresswell, K., S. Cunningham-Burley, and A. Sheikh. 2018. “Health Care Robotics: Qualitative Exploration of Key Challenges and Future Directions.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 20 (7): e10410. https://doi.org/10.2196/10410.

- Dawson, P. 2020. Defending Assessment Security in a Digital World: Preventing e-Cheating and Supporting Academic Integrity in Higher Education. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

- de Graaf, M. M. A. 2016. “An Ethical Evaluation of Human–Robot Relationships.” International Journal of Social Robotics 8 (4): 589–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-016-0368-5.

- Diehl, K., C. Jansen, K. Ishchanova, and J. Hilger-Kolb. 2018. “Loneliness at Universities: Determinants of Emotional and Social Loneliness among Students.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (9): 1865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091865.

- Dosovitsky, G., and E. L. Bunge. 2021. “Bonding With Bot: User Feedback on a Chatbot for Social Isolation.” Frontiers in Digital Health 3 (2021): 735053. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2021.735053.

- Eager, Bronwyn, and Ryan Brunton. 2023. “Prompting Higher Education Towards AI-Augmented Teaching and Learning Practice.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 20 (5). http://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.5.02.

- Escotet, MÁ. 2023. “The Optimistic Future of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education.” Prospects, 1–10.

- Essel, H. B., D. Vlachopoulos, A. Tachie-Menson, E. E. Johnson, and P. K. Baah. 2022. “The Impact of a Virtual Teaching Assistant (Chatbot) on Students’ Learning in Ghanaian Higher Education.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 19 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00362-6.

- Fowler, P. R., and H. R. Boylan. 2010. “Increasing Student Success and Retention: A Multidimensional Approach.” Journal of Developmental Education 34 (2): 2.

- Fulmer, R., A. Joerin, B. Gentile, L. Lakerink, and M. Rauws. 2018. “Using Psychological Artificial Intelligence (Tess) to Relieve Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: Randomized Controlled Trial.” JMIR Mental Health 5 (4): e64. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.9782.

- Gao, Lily (Xuehui), María Eugenia López-Pérez, Iguácel Melero-Polo, and Andreea Trifu. 2024. “Ask ChatGPT first! Transforming learning experiences in the age of artificial intelligence.” Studies in Higher Education: 1–25. http://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2323571.

- Gillen-O’Neel, C. 2021. “Sense of Belonging and Student Engagement: A Daily Study of First- and Continuing-Generation College Students.” Research in Higher Education 62 (1): 45–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09570-y.

- Gomes, C., N. A. Hendry, R. De Souza, L. Hjorth, I. Richardson, D. Harris, and G. Coombs. 2021. “Higher Degree Students (HDR) during COVID-19.” Journal of International Students 11 (S2): 19–37. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v11is2.3552.

- Gopalan, M., A. Linden-Carmichael, and S. Lanza. 2021. “College Students’ Sense of Belonging and Mental Health Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Adolescent Health 70 (2): 228–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.010.

- Hayes, Sarah, Petar Jandrić, and Benjamin J Green. 2024. “Towards a Postdigital Social Contract for Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence.” Postdigital Science and Education. http://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-024-00459-3.

- Hu, K. 2023, February 2. “ChatGPT Sets Record for Fastest-growing User Base - Analyst Note.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/chatgpt-sets-record-fastest-growing-user-base-analyst-note-2023-02-01/.

- Hu, B., Y. Mao, and K. J. Kim. 2023. “How Social Anxiety Leads to Problematic Use of Conversational AI: The Roles of Loneliness, Rumination, and Mind Perception.” Computers in Human Behavior 145: 107760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107760.

- Ivanov, S. 2023. “The Dark Side of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education.” The Service Industries Journal 43 (15-16): 1055–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2023.2258799.

- Kahu, E., and K. Nelson. 2018. “Student Engagement in the Educational Interface: Understanding the Mechanisms of Student Success.” Higher Education Research & Development 37 (1): 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197.

- Kalkbrenner, M. T., A. L. Jolley, and D. G. Hays. 2021. “Faculty Views on College Student Mental Health: Implications for Retention and Student Success.” Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 23 (3): 636–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025119867639.

- Kelly, M. E., H. Duff, S. Kelly, J. E. McHugh Power, S. Brennan, B. A. Lawlor, and D. G. Loughrey. 2017. “The Impact of Social Activities, Social Networks, Social Support and Social Relationships on the Cognitive Functioning of Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review.” Systematic Reviews 6 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2.

- Kelly, Andrew, Miriam Sullivan, and Katrina Strampel. 2023. “Generative artificial intelligence: University student awareness, experience, and confidence in use across disciplines.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 20 (6). http://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.6.12.

- Kerper, L. F. D., C. Spies, J. Tillinger, K. Wegscheider, A.-L. Salz, E. Weiss-Gerlach, T. Neumann, and H. Krampe. 2014. “Screening for Depression, Anxiety and General Psychological Distress in Preoperative Surgical Patients: A Psychometric Analysis of the Patient Health Questionnaire 4 (PHQ-4).” Clinical Health Promotion - Research and Best Practice for Patients, Staff and Community 4 (1): 5–14. https://doi.org/10.29102/clinhp.14002.

- Kift, S., K. Nelson, and J. Clarke. 2010. “Transition Pedagogy: A Third Generation Approach to FYE-A Case Study of Policy and Practice for the Higher Education Sector.” Student Success 1 (1): 1–20.

- Kim, J., K. Merrill Jr, and C. Collins. 2021. “AI as a Friend or Assistant: The Mediating Role of Perceived Usefulness in Social AI vs. Functional AI.” Telematics and Informatics 64: 101694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101694.

- Knox, M. W., J. Crawford, J. A. Kelder, A. R. Carr, and C. J. Hawkins. 2020. “Evaluating Leadership, Wellbeing, Engagement, and Belonging across Units in Higher Education: A Quantitative Pilot Study.” Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching 3 (1): 108–17. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2020.3.s1.12.

- Laestadius, L., A. Bishop, M. Gonzalez, D. Illenčík, and C. Campos-Castillo. 2022. “Too Human and not Human Enough: A Grounded Theory Analysis of Mental Health Harms from Emotional Dependence on the Social Chatbot Replika.” New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221142007.

- Lee, C.-Y. S., and S. E. Goldstein. 2016. “Loneliness, Stress, and Social Support in Young Adulthood: Does the Source of Support Matter?” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 45 (3): 568–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0395-9.

- Liu, H., H. Peng, X. Song, C. Xu, and M. Zhang. 2022. “Using AI Chatbots to Provide Self-Help Depression Interventions for University Students: A Randomized Trial of Effectiveness.” Internet Interventions 27: 100495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2022.100495.

- Lodge, Jason, Paula de Barba, and Jaclyn Broadbent. 2023. “Learning with Generative Artificial Intelligence Within a Network of Co-Regulation.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 20 (7). http://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.7.02.

- Loveys, K., G. Fricchione, K. Kolappa, M. Sagar, and E. Broadbent. 2019. “Reducing Patient Loneliness with Artificial Agents: Design Insights From Evolutionary Neuropsychiatry.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 21 (7): e13664. https://doi.org/10.2196/13664.

- Ma, Y., and K. L. Siau. 2018. “Artificial Intelligence Impacts on Higher Education.” MWAIS 2018 Proceedings, 42. http://aisel.aisnet.org/mwais2018/42.

- Maunder, R. E. 2018. “Students’ Peer Relationships and their Contribution to University Adjustment: The Need to Belong in the University Community.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 42 (6): 756–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1311996.

- Meehan, C., and K. Howells. 2019. “In Search of the Feeling of ‘Belonging’ in Higher Education: Undergraduate Students Transition into Higher Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 43 (10): 1376–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1490702.

- Mishra, S. 2020. “Social Networks, Social Capital, Social Support and Academic Success in Higher Education: A Systematic Review with a Special Focus on ‘Underrepresented’ Students.” Educational Research Review 29: 100307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100307.

- Nguyen, Andy, Yvonne Hong, Belle Dang, and Xiaoshan Huang. 2024. “Human-AI collaboration patterns in AI-assisted academic writing.” Studies in Higher Education: 1–18. http://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2323593.

- Nieuwoudt, J. E., and M. L. Pedler. 2023. “Student Retention in Higher Education: Why Students Choose to Remain at University.” Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 25 (2): 326–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025120985228.

- O’Keeffe, P. 2013. “A Sense of Belonging: Improving Student Retention.” College Student Journal 47 (4): 605–13.

- Ouyang, F., L. Zheng, and P. Jiao. 2022. “Artificial Intelligence in Online Higher Education: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research from 2011 to 2020.” Education and Information Technologies 27 (6): 7893–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10925-9.

- Pani, B., J. Crawford, and K.-A. Allen. 2023. “Can Generative Artificial Intelligence Foster Belongingness, Social Support, and Reduce Loneliness? A Conceptual Analysis.” In Applications of Generative AI, edited by Z. Lv. New York, NY: Springer Nature.

- Park, C., A. Majeed, H. Gill, J. Tamura, R. C. Ho, R. B. Mansur, F. Nasri, et al. 2020. “The Effect of Loneliness on Distinct Health Outcomes: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis.” Psychiatry Research 294: 113514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113514.

- Park, J. S., J. C. O’Brien, C. J. Cai, M. R. Morris, P. Liang, and M. S. Bernstein. 2023. “Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior (arXiv:2304.03442).” arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.03442.

- Pearson, J. E. 1986. “The Definition and Measurement of Social Support.” Journal of Counseling & Development 64 (6): 390–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1986.tb01144.x.

- Pedler, M. L., R. Willis, and J. E. Nieuwoudt. 2022. “A Sense of Belonging at University: Student Retention, Motivation and Enjoyment.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 46 (3): 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1955844.

- Perkins, M. 2023. “Academic Integrity Considerations of AI Large Language Models in the Post-Pandemic era: ChatGPT and Beyond.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 20 (2). https://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.02.07.

- Pesonen, J. A. 2021, July 24-29. “Are You OK?’Students’ Trust in a Chatbot Providing Support Opportunities Learning and Collaboration Technologies: Games and Virtual Environments for Learning. Virtual Event.

- Rudolph, J., S. Tan, and S. Tan. 2023. “ChatGPT: Bullshit Spewer or the End of Traditional Assessments in Higher Education?” Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching 6 (1): 342–363. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2023.6.1.9.

- Russell, D. W. 1996. “UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure.” Journal of Personality Assessment 66 (1): 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2.

- Schall, J., T. L. Wallace, and V. Chhuon. 2016. “‘Fitting in’ in High School: How Adolescent Belonging is Influenced by Locus of Control Beliefs.” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 21 (4): 462–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2013.866148.

- Seo, K., J. Tang, I. Roll, S. Fels, and D. Yoon. 2021. “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Learner–Instructor Interaction in Online Learning.” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 18 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00292-9.

- Sepahpour, T. 2020. “Ethical Considerations of Chatbot Use for Mental Health Support.” RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary 4 (6): 14–7.

- Sjöberg, A., and M. Sverke. 2000. “The Interactive Effect of Job Involvement and Organizational Commitment on Job Turnover Revisited: A Note on the Mediating Role of Turnover Intention.” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 41 (3): 247–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00194.

- Stevens, N. 2001. “Combating Loneliness: A Friendship Enrichment Programme for Older Women.” Ageing and Society 21 (2): 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X01008108.

- Stickley, A., A. Koyanagi, M. Leinsalu, S. Ferlander, W. Sabawoon, and M. McKee. 2015. “Loneliness and Health in Eastern Europe: Findings from Moscow, Russia.” Public Health 129 (4): 403–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2014.12.021.

- Sullivan, Y., S. Nyawa, and S. Fosso Wamba. 2023. “Combating Loneliness with Artificial Intelligence: An AI-Based Emotional Support Model.” scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/103173.

- Ta, V., C. Griffith, C. Boatfield, X. Wang, M. Civitello, H. Bader, E. Decero, and A. Loggarakis. 2020. “User Experiences of Social Support from Companion Chatbots in Everyday Contexts: Thematic Analysis.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (3): e16235. https://doi.org/10.2196/16235.

- Tice, D., R. Baumeister, J. Crawford, K.-A. Allen, and A. Percy. 2021. “Student Belongingness in Higher Education: Lessons for Professors from the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 18 (4). https://doi.org/10.53761/1.18.4.2.

- Tinto, V. 1990. “Principles of Effective Retention.” Journal of The First-Year Experience & Students in Transition 2 (1): 35–48.

- Turkle, S. 2011. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Tyrer, S., and B. Heyman. 2016. “Sampling in Epidemiological Research: Issues, Hazards and Pitfalls.” BJPsych Bulletin 40 (2): 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.114.050203.

- Ulmanen, S., T. Soini, J. Pietarine, and K. Pyhältö. 2016. “Students’ Experiences of the Development of Emotional Engagement.” International Journal of Educational Research 79: 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.06.003.

- UNESCO. 2023 “Higher Education: What You Need to Know.” https://www.unesco.org/en/higher-education/need-know.

- van Rooij, E. C. M., E. P. W. A. Jansen, and W. J. C. M. van de Grift. 2017. “Secondary School Students’ Engagement Profiles and their Relationship with Academic Adjustment and Achievement in University.” Learning and Individual Differences 54: 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.01.004.

- Varrella, S. 2021, November 4. “Loneliness among Adults Worldwide by Country 2021.” Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1222815/loneliness-among-adults-by-country/.

- Vincent-Lancrin, S., and R. van der Vlies. 2020. “Trustworthy Artifcial Intelligence (AI) in Education: Promises and Challenges.” OECD Education Working Papers Series, OECD.

- Wang, T., B. D. Lund, A. Marengo, A. Pagano, N. R. Mannuru, Z. A. Teel, and J. Pange. 2023. “Exploring the Potential Impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on International Students in Higher Education: Generative AI, Chatbots,.” Analytics, and International Student Success 13 (11): 6716. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13116716.

- Wang, Y., C. Xie, C. Liang, P. Zhou, and L. Lu. 2022. “Association of Artificial Intelligence Use and the Retention of Elderly Caregivers: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Empowerment Theory.” Journal of Nursing Management 30 (8): 3827–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13823.

- Xie, T., I. Pentina, and T. Hancock. 2023. “Friend, Mentor, Lover: Does Chatbot Engagement Lead to Psychological Dependence?” Journal of Service Management 34 (4): 806–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-02-2022-0072.

- Yang, S., and C. Evans. 2019. “Opportunities and Challenges in Using AI Chatbots in Higher Education.” Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Education and E-Learning, 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1145/3371647.3371659.

- Zimet, G. D., N. W. Dahlem, S. G. Zimet, and G. K. Farley. 1988. “The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.” Journal of Personality Assessment 52 (1): 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.