ABSTRACT

Compared to the general population, university students experience unique demands and stressors that impact psychosocial distress. High levels of psychosocial distress can affect students academically, socially, and professionally. Strategies students use to cope with stress on their own, particularly problem- and emotion-focused strategies, can decrease distress levels. While individual coping strategies can lower distress, it remains unclear which strategies are most effective among students and whether distinct profiles of strategies and their effectiveness exist. This study aimed to explore how Australian university students use individual coping strategies to manage stress using Latent Profile Analysis. 376 students completed an online survey of coping strategies, psychosocial distress, and general wellbeing, between November and December 2022 (Mean age = 25.76; 68.62% female). Psychosocial distress levels were characterised by anxiety, depression, perceived stress, social isolation, and emotional support. Four coping profiles were extracted: no effective/no coping, problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and emotion-focused religion-dominant coping. Students endorsing problem-focused coping had significantly lower levels of psychosocial distress compared to the no effective/no coping and emotion-focused religion-dominant coping profiles, but showed no difference compared to emotion-focused coping. The no effective/no coping profile was associated with the highest levels of psychosocial distress. This underscores the importance of supporting students to endorse primarily problem-focused coping strategies, as well as emotion-focused coping strategies and educating students on how to effectively employ strategies, especially those not endorsing any effective strategies. These results may inform university support services and training for educators working directly with students on how to educate students about coping with stress.

Introduction

The transition from high school to university is accompanied by a unique set of stressors, such as navigating a new physical and social environment, and facing new learning demands and increased academic pressure, which can negatively impact the mental health and particularly the psychological distress of undergraduate students (Knoesen and Naudé Citation2018; Thompson et al. Citation2019). Psychosocial distress, encompassing both psychological and social aspects of unpleasant emotional experiences, exists along a continuum (Wood Citation2015) and can interfere with an individual's ability to handle life stressors. Throughout a typical 3- to 4-year degree, Australian university students report high levels of psychosocial distress and have comparatively higher levels of psychological distress than age-matched population samples (Larcombe et al. Citation2016; Liu et al. Citation2021; McGillivray and Pidgeon Citation2015; Schofield et al. Citation2016). One-quarter of Australian university students experience severe symptoms of stress, anxiety, or depression (Larcombe et al. Citation2016), and the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) saw a decrease in students’ mental health in 2020 as extended periods of lockdown and social isolation limited availability of social supports and restricted class attendance (Dingle, Han, and Carlyle Citation2022).

The ability to effectively manage stress is key to students’ overall coping, adjustment and success at university (Holdsworth, Turner, and Scott-Young Citation2018). The negative effects of stress on health outcomes are shown to be mediated by coping strategies (Klainin-Yobas et al. Citation2014; Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984). Coping encompasses cognitive processes and behavioural actions that individuals employ to manage stress (Folkman et al. Citation1987). Coping strategies utilised by students vary depending on the context, duration, and type of stressor and individual coping resources that may differ by student age group, for example, first-year vs. mature-entry students.

Research and clinical practice classify coping into two fundamental types: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984). Problem-focused coping involves efforts to manage or overcome stress by dealing directly with the problem causing the stress or taking steps to prevent further stressors. For example, evaluating the situation, making lists, and putting feelings into perspective are problem-focused coping strategies as they actively involve thinking about the cause of stress and taking steps to overcome it. Emotion-focused coping seeks to regulate the emotions caused by the stressor without directly trying to change or prevent the stressor. For example, exercising, listening to music, or participating in religious activity are emotion-focused coping strategies as they do not directly address the cause of stress, but seek to regulate emotions to reduce feelings of stress. In students, problem-focused strategies might include planning and organising study materials, while emotion-focused behaviours could involve exercising or meditating to reduce feelings of stress. Folkman and Lazarus (Citation1980) posited that an individual is more likely to use problem-focused coping in situations that they deem as controllable, while emotion-focused coping is more likely to be used in situations where one feels powerless to change.

Globally, the use of problem-focused strategies, including planning, evaluating, and information seeking, is positively correlated with student psychological well-being, and reduced psychological distress, including symptoms of depression (Gustems-Carnicer and Calderón Citation2013; Sagone and De Caroli Citation2014; Wang, Ng, and Siu Citation2023; Zaman and Ali Citation2019). In contrast, some emotion-focused coping strategies, such as behavioural disengagement and denial, are associated with greater psychological distress (Akbar and Aisyawati Citation2021). Emotion-focused strategies of self-blame and denying the situation were additionally associated with lower academic achievement among university students in Australia (Rice et al. Citation2021). Other emotion-focused coping strategies, such as listening to music, exercising, and resting were associated with reduced stress in Australian students during COVID-19 (Vidas et al. Citation2021). Evidence to-date highlights the varied outcomes of individual coping strategies within the broad classifications of problem-focused and emotion-focused coping. A paucity of research has examined if these coping approaches differ in effectiveness.

Inter-and intra-individual contextual factors such as help-seeking behaviours, social support, and mental health literacy, are important determinants of coping strategies in students (Akbar and Aisyawati Citation2021; Freire et al. Citation2020; Reeve et al. Citation2013; Ye et al. Citation2020). The likelihood of seeking help from social and professional sources is often impacted by low mental health literacy, a desire to handle issues alone, financial concerns and stigma (Andrade et al. Citation2014). Recent research identified that 63% of students would not seek external help when facing emotional distress, rather, they would wait for the problem to go away on its own (Theurel and Witt Citation2022). This preference for dealing with stress alone underscores the need for specific investigation of the use and effectiveness of coping strategies that are not dependent on seeking help from others. Many university students have limited access to social support or trusted health professionals as they often move out of home or from their home country to study abroad (Alsubaie et al. Citation2019), and COVID-19 restrictions further limit the ability of students to seek social support or see health professionals in person. Understanding non-help-seeking coping strategies that are associated with lower levels of psychosocial distress is crucial to supporting students’ self-management of mental health.

A limitation of previous investigations is the frequent use of variable-centred approaches, measuring singular coping strategies, to explain the associations between coping strategies and outcomes (Howard and Hoffman Citation2018), where polyregulation (use of multiple strategies) is considered more common (Ford, Gross, and Gruber Citation2019). Latent profile analysis (LPA) is a person-centred approach seeking to identify clusters or ‘profiles’ of individuals based on response patterns across a series of variables (Mathew and Doorenbos Citation2022). LPA would therefore allow multiple coping strategies to be examined concurrently by creating profiles of students’ coping strategy use. Using this approach, Kenntemich et al. (Citation2023) identified five coping profiles of German adults during COVID-19 that varied in the type, for example, problem-focused coping, and use of coping strategies, and were differently associated with wellbeing levels. Pété et al. (Citation2022) described four coping profiles of French athletes during COVID-19 (self-reliant, engaged, avoidant, active and social coping), with avoidant coping associated with higher anxiety and poorer emotional regulation. Despite this recent work, a person-centred approach to examining coping profiles of non-help seeking coping strategies has not been applied in a university student population. Furthermore, previous studies used the Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE), which is capable of capturing the frequency of coping strategy use, but not the effectiveness of each strategy (Carver Citation1997). Exploring the effectiveness of each strategy can help tailor information and support for students to better understand effective and non-effective coping.

The current study undertook an important extension of previous coping research, seeking to examine student coping profiles based on the perceived effectiveness of strategies post-COVID-19. This study has two aims: (1) to identify latent coping strategy effectiveness profiles in an Australian university student population, using LPA and (2) to explore differences in levels of psychosocial distress between the profiles. Although LPA is data-driven, based on previous research (Fornés-Vives et al. Citation2016; Huang et al. Citation2020), it is first hypothesised that three profiles will emerge: one profile predominantly characterised by effective use of problem-focused coping strategies, one characterised predominantly by effective use of emotion-focused coping strategies, and one consisting of students who do not effectively use coping strategies. Based on previous research (Rice et al. Citation2021; Zaman and Ali Citation2019), the second hypothesis is that students in the problem-focused coping strategies profile will have lower mean levels of psychosocial distress than the emotion-focused and no effective coping strategies profiles.

Methods

Participants

University students aged 18 + and enrolled at a Monash University Australian campus were recruited as part of the broader Thrive@Monash survey series that assessed students’ overall well-being at different timepoints during and beyond COVID-19. All participation was voluntary and participants provided informed consent. Participants (n = 376) were included in the final analyses. This study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project Number 32546).

Procedure

Monash University students received a link via email inviting them to participate in the 20-minute online Qualtrics survey as part of the broader Thrive@Monash surveys focusing on student wellbeing throughout, and beyond COVID-19. Data were collected between 21 November and 2 December 2022, following the completion of the first full year of on-campus learning post-COVID-19 lockdowns (Victoria did not experience any lockdown measures in 2022). No reimbursement was provided.

Measures

Information regarding demographic characteristics was collected at the start of the survey, including age, gender (female, male, non-binary/gender diverse, gender not listed, or prefer not to say), ethnicity (Southeast Asian, East Asian, South Asian, White/European, African, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, or other), current year of study (first, second, third, or fourth year and higher) and international student status (yes/no).

Psychosocial distress

Perceived stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, and Mermelstein Citation1983) is a 10-item scale measuring perceived stress levels in the last month, for example ‘how often did you feel nervous and stressed?’. Items are measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Items were reversed scored and summed to create a total score, in accordance with the published manual. Higher scores indicate higher perceived stress levels. The PSS has strong psychometric properties, including good reliability (α = 0.74–0.91; Lee Citation2012). There was good internal consistency in the current study (α = 0.88).

Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (Promis)

PROMIS measures are validated, person-centred measures rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Items are summed to create a total raw score and converted to a standardised T-score. Higher scores indicate higher levels of the construct being measured.

Anxiety. Anxiety 4a (Pilkonis et al. Citation2011) comprises 4 items measuring anxiety levels in the last 7 days, for example ‘I felt fearful’, with good convergent validity and internal reliability (α = .89; Kroenke et al. Citation2014) and good reliability in the current study (α = .90).

Depression. Depression 4a (Pilkonis et al. Citation2011) comprises 4 items measuring depression levels in the last 7 days, for example ‘I felt depressed’, with good convergent validity and internal reliability (α = .93; Kroenke et al. Citation2014) and good reliability in the current study (α = .94).

Emotional support. Emotional support 4a (Hahn et al. Citation2014) comprises 4 items measuring emotional support levels in the last 7 days, for example ‘I have someone who will listen to me when I need to talk.’ This scale has good internal consistency for this sample (α = .95).

Social isolation. Social Isolation 4a (Hahn et al. Citation2014), comprises 4 items measuring social isolation levels in the last 7 days, for example ‘I felt left out’, with excellent reliability (α = .92; Primack et al. Citation2017) and good internal consistency for this sample (α = .90).

Coping strategies questionnaire

Coping items were adapted from Thayer, Robert Newman, and McClain (Citation1994). Participants were asked how effective they found 16 coping strategies, for example, ‘exercise’ and ‘be alone’. Two items (‘call someone on the phone’ and ‘use the internet for social communication’) were not included as they were classified as coping strategies that involved seeking help from others and not individual coping strategies, the construct being explored (see Supplementary Material for further details). A coping score for each strategy was derived from this questionnaire with scores ranging from 1 to 6 with 1 indicating that a participant did not use the strategy and 2–6 indicating the effectiveness of the strategy (2 = not effective to 6 = always effective). This scale has acceptable internal consistency for this sample (α = 0.74).

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team Citation2022, version 4.2.2) and RStudio (Posit team Citation2023, version 2023.3.0.386).

Psychosocial distress score

Calculated using: PROMIS Anxiety 4a, PROMIS Depression 4a, PROMIS Social Isolation 4a, PROMIS Emotional Support 4a, and PSS. A principal component analysis (PCA) was run to reduce the 5 scales into a singular score that represents psychosocial distress, to retain maximum statistical power and reduce the risk of Type 1 error in comparisons between coping profiles. A correlation matrix confirmed that the questionnaires were significantly correlated (.27 < |r| < .77, p < .001). All assumptions were met including Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (.83) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (p < .001). One component was extracted from the PCA with an Eigenvalue greater than 1 (3.26; Kaiser Citation1960), and confirmed by a visual examination of the scree plot. This component will be referred to as ‘psychosocial distress’.

Latent profile analysis (LPA)

LPA was conducted using mclust (Scrucca et al. Citation2016) and tidyLPA (Rosenberg et al. Citation2019), packages in R, to identify latent coping profiles. Mahalanobis distance (d = 36.12) was used to identify and remove multivariate outliers and participants who responded with the same response 10 or more times were removed to reduce response bias, for example ‘always effective’ to 10 + coping strategies. Mean coping scores for each coping strategy were standardised prior to conducting the LPA to allow for greater model visualisation. To determine the optimal number of latent profiles, the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), which considers model-fit and model-complexity (Schwarz Citation1978), the Integrated Complete-data Likelihood (ICL) criterion (Biernacki, Celeux, and Govaert Citation2000), and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT; Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén Citation2007) were used. Lower values in BIC and ICL suggest a better model fit. These analyses also consider entropy, the distinctness of each profile, with scores ranging from 0-1 and higher scores indicating better model fit. Demographic characteristics between profiles were compared using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and non-parametric equivalents and appropriate post-hoc tests.

After selecting the optimal LPA model, a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was run to examine the differences in psychosocial distress between profiles. Assumptions were met including homogeneity of variance, assessed by Levene's test (p = .161) and normality, assessed through the inspection of Q-Q plots and Tukey's post-hoc test was run for significant results.

All analyses were conducted with an alpha level of significance set at.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

Students (N = 559) consented to the survey. Several participants (n = 60) did not provide demographic data, 91 participants did not complete the coping strategies questionnaire, and 7 participants did not complete all psychosocial distress questionnaires, all were removed. Several participants (n = 25) were identified as multivariate outliers and/or had responded to the coping questionnaire with the same response 10 or more times and were removed. Thus, the study included n = 376 Monash University students aged 18–81 years (M = 27.76, SD = 10.15). The majority of participants were female (68.6%), almost half were white/European (46.3%), 33.3% were in the first year of their degree, and 37.2% were international students. Sample demographic characteristics are summarised in . Coping strategy use and mean coping scores are displayed in . The most used coping strategies were ‘evaluating/analysing the situation’ (94.7%), ‘being alone’ (94.4%), and ‘listening to music’ (93.6%). The strategies with the highest coping score, reflecting effectiveness, were ‘listening to music’ (M = 4.40, SD = 1.27) and ‘resting/napping/sleeping’ (M = 4.03, SD = 1.42). The least commonly used and least effective were ‘religious activity’ (32.1%, M = 1.95, SD = 1.55) and ‘changing eating habits’ (67.6%, M = 2.84, SD = 1.54).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants.

Table 2. Coping strategy use, mean coping scores and mean psychosocial distress levels.

Student coping profiles

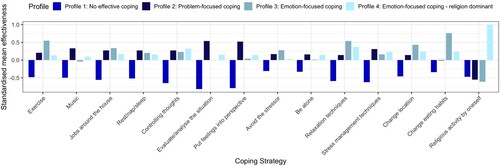

The BIC and ICL both suggested that a 4-profile solution was suitable. BLRT was significant for the 4-profile solution (p < .05). The theoretical meaning of the ideal profiles was considered to adequately map onto Lazarus and Folkman's (Citation1984) theory of coping with the addition of a religion-based coping profile. Whilst other potential solutions were examined, for example, a 3-profile solution, they were not deemed theoretically meaningful and statistical tests were not as robust. Profiles for the 4-profile solution are visually displayed in , and the demographic characteristics of each profile are in .

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of coping profiles and p-values from demographic profile comparison analyses

Profile 1 (n = 113; 30.05%; ‘No effective/no coping’, NEC) was characterised by students who did not use/did not find coping strategies effective. Mean coping scores for ‘exercise’ (M = 3.05), ‘listening to music’ (M = 3.75), ‘resting/napping/sleeping’ (M = 3.28), ‘avoiding the stressor’ (M = 3.14), ‘being alone’ (M = 3.39) and ‘stress management techniques’ (M = 3.00), indicate that this profile considers these strategies to be ‘rarely effective’, based on the scoring of the coping strategies questionnaire. All other coping strategies had a mean coping score below 3, and were not considered effective.

Profile 2 (n = 146; 38.83%; ‘Problem-focused coping’, PFC) comprised students who primarily found problem-focused strategies to be more effective than emotion-focused strategies.

Profile 3 (n = 23; 6.12%; ‘Emotion-focused coping’, EFC) was characterised by individuals who predominantly identified emotion-focused coping strategies, particularly ‘exercise’ and ‘changing eating habits’, to be the most effective.

Profile 4 (n = 94; 25%; ‘Emotion-focused religion-dominant coping’, EFC-R) was primarily characterised by students who found ‘religious activity’ to be the most effective. They found other emotion-focused coping strategies, such as ‘relaxation techniques’, to be more effective than problem-focused strategies.

All demographic comparisons between the four profiles were not significant except for age and ethnicity (p = .017). However, age was not significantly correlated with psychosocial distress and was not included in the psychosocial distress ANOVA. Post-hoc tests show only Profile 1 and Profile 3 differed significantly in age (p = .007) with the NEC profile being significantly younger than the EFC profile. P-values can be seen in .

Differences in levels of psychosocial distress between profiles

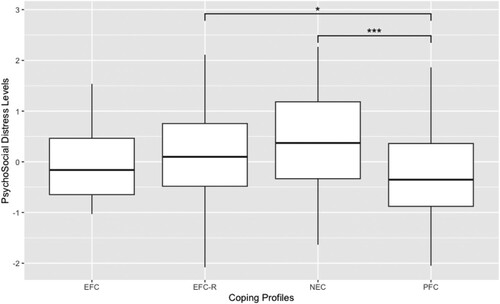

An independent one-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of coping profiles on psychosocial distress with a medium effect size (F(3, 372) = 10.31, p < .001, ηp2 = .08). PFC had the lowest level of psychosocial distress (M = −.29, SD = .91), followed by EFC (M = −.05, SD = .79), EFC-R (M = .08, SD = .94), and NEC (M = .36, SD = 1.03; see ). Tukey's post-hoc comparison showed that psychosocial distress was statistically lower in PFC compared to NEC and EFC-R (see ).

Figure 2. Mean psychosocial distress levels compared between the four coping profiles.

Note: NEC = No effective/no coping, PFC = Problem-focused coping, EFC = Emotion-focused coping, EFC-R = Emotion-focused religion-dominant coping. * p < .05, ** p < .01 and *** p < .001.

Table 4. Post-hoc comparisons of psychosocial distress levels between coping profiles.

Discussion

This study aimed to further existing research to understand university students’ non-help-seeking coping strategies profiles and the relationship between coping strategy use and levels of psychosocial distress. Specifically, four coping profiles were identified in this population: problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, emotion-focused religion-dominant coping, and no effective/no coping strategies. This analysis allowed for a novel insight into profiles of university students' coping strategy use and effectiveness. Comparisons between profiles indicated that problem-focused coping strategies are associated with the lowest levels of psychosocial distress, significantly lower than students who endorsed primarily emotion-focused religion-dominant strategies and no effective/no strategies.

Student coping profiles

The first aim was to identify profiles based on the perceived effectiveness of coping strategies in Australian university students. The three hypothesised profiles were identified, in addition to a fourth profile (EFC-R). Almost a third of students were identified as not effectively engaging with coping strategies (NEC profile), perceiving ‘avoiding the stressor’ and ‘being alone’ to be more effective than problem-focused strategies. They also had the highest levels of psychosocial distress between the four profiles. This may reflect poor mental health literacy, for example, limited knowledge of how to effectively overcome stressful events. This may also reflect the average age of the profile, 25.98 (8.76), suggesting that this profile consists of young adults who may have had less time or fewer opportunities to develop and refine effective coping approaches. Similar ‘low coping’ profiles have been found in previous studies (Freire et al. Citation2020; Hasselle et al. Citation2019; Kenntemich et al. Citation2023). However, this profile does not map onto Lazarus and Folkman's (Citation1984) model of coping which posited that coping strategies fall into one of two broad categories (problem- or emotion-focused) but does not accommodate individuals who do not effectively engage in either of these broad coping approaches. The current study therefore makes an important contribution in highlighting this vulnerable subgroup of university students who would greatly benefit from interventions aiming to enhance their coping skillset.

Similar PFC and EFC profiles from this study have been identified in previous studies, with profiles often focused on either emotion- or problem-focused coping (Hasselle et al. Citation2019; Lin and Wu Citation2014). This aligns with Lazarus and Folkman's (Citation1984) broad classification of coping strategies as either problem- or emotion-focused. Specific strategies examined in the current study that map onto this original theory include ‘evaluating/analysing the situation’ in the PFC profile and ‘avoiding the stressor’ in the EFC profile.

The EFC-R group was not predicted and does not map directly onto Lazarus and Folkman's (Citation1984) binary model of coping strategies, suggesting that a subset of university students effectively use individual religious activity when experiencing stress. This is consistent with previous research reporting a ‘high functional and religious coping’ profile characterised by the use of functional strategies, such as planning, and frequent use of ‘religion-based’ coping (Kenntemich et al. Citation2023). Religion and spirituality are commonly used strategies in non-Australian cohorts, particularly cohorts from the Middle East and Southeast Asia (Abdulghani et al. Citation2020; Salman et al. Citation2022; Yan Citation2019). The EFC-R group demonstrated the highest percentage of international students and the lowest proportion of students from a ‘white/European’ ethnic background, with the majority identifying as South and/or East Asian. This is consistent with the high prevalence of religious practices in students from areas such as Southeast Asia. A minority of Australian university students have been reported to strongly affiliate with a religion or practice religion at home (Hyde and Knowles Citation2013; Jenkin, Garrett, and Keay Citation2023), and in the current study, individual religious activity was the least utilised of all 14 coping strategies. Differences in endorsement of religion-based coping between studies and nations may reflect the nature of how coping was assessed in our study, which asked students about the effectiveness of religious activity by oneself, as opposed to group and organised religious activity (Chai et al. Citation2012; Francis et al. Citation2019).

The identification of four student coping profiles is consistent with previous research (Cabanach et al. Citation2018; Freire et al. Citation2020; Hasselle et al. Citation2019), however, current literature often includes social coping profiles or social coping strategies in their analyses. The current study allows for insight into coping profiles for students handling stressors by themselves without external help, which is vital in helping all students engage in coping strategies regardless of barriers to help-seeking including limited social connections, stigma, financial constraints, and location. Additionally, the identification of four profiles highlights that a binary classification of coping into problem-focused and emotion-focused, as posed by Lazarus and Folkman, appears too simplified as supported by studies that highlight religion/spirituality as an additional strategy (Dias, Cruz, and Fonseca Citation2012). As a result, grouping individuals by problem-focused or emotion-focused categories only, is not likely to be an effective or accurate way to examine the effectiveness and impact of coping on psychological outcomes.

Differences in psychosocial distress between coping profiles

The NEC group had the highest level of psychosocial distress suggesting that students who do not effectively use coping strategies experience greater distress. In comparison to the significantly lower levels of psychosocial distress displayed by the PFC group, this highlights the important role that effective coping plays in managing stress (Folkman et al. Citation1987). A significant difference was also found between PFC and EFC-R highlighting that directly addressing stressors is associated with less psychosocial distress than indirectly dealing with negative feelings, primarily through religious activity. There was no significant difference between the EFC and EFC-R groups, suggesting that religious activity as a coping strategy is not significantly superior to other emotion-focused strategies.

There was no significant difference between psychosocial distress levels in the problem-focused and emotion-focused groups. This contradicts past research that underscores the effectiveness of problem-focused coping over only dealing with feelings that arise from the event through emotion-focused strategies (Gustems-Carnicer and Calderón Citation2013; Sagone and De Caroli Citation2014). This may be a result of potential confounding influences of the nature of the stressor that may impact what strategies are available for a student and are useful and relevant to the specific stressor. The non-significant difference in the PFC and EFC group's psychosocial distress levels is likely because we did not ask about what stressors students were facing, only the strategies. Some stressors may be better suited to emotion-focused strategies and others to problem-focused strategies and promoting only one category of coping strategy would be detrimental to students. This is emphasised in Folkman and Lazarus (Citation1980) who highlighted that individuals who view a stressor as controllable, are more likely to employ problem-focused coping than emotion-focused coping. Ultimately, our findings suggest that primarily problem-focused coping strategies, as well as emotion-focused coping strategies, implemented effectively, are better than no coping strategies.

These results have important implications for distress prevention in university students and suggest that both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies are beneficial to university students. These results may be particularly impactful for students who are not willing to seek external support, as being educated and trained on how to manage stress may better equip them to deal with stress on their own. Even if students are not willing to engage others to assist them in coping with stressors, these findings highlight that there are strategies that they can employ on their own that still lead to positive mental health and well-being outcomes. This may be particularly impactful in situations like COVID-19, where students are unable to access external resources or seek help in person.

These findings have implications for both policy and practice and can help equip university teams and educators with the necessary information to help support university students in times of distress. By promoting and teaching students about coping strategies, students will have a better chance of supporting themselves during tough situations.

For students to achieve their best academically and in their future careers, they need to be able to handle stress effectively. This research provides insight into how to improve student success by promoting the use of coping strategies, primarily problem-focused strategies, to help students manage stress on their own. By equipping educators who work directly with student cohorts with the necessary skills to help students manage stress from early in their university journey, there is also the potential to decrease the burden on university counselling services. This would apply to students experiencing low levels of distress who can be equipped with the tools to prevent further distress.

Limitations and future directions

This study provides a unique insight into university students’ coping profiles from a non-help-seeking coping strategy perspective. It uses well-validated measures of psychosocial distress (Cohen, Kamarck, and Mermelstein Citation1983; Hahn et al. Citation2014; Pilkonis et al. Citation2011) and builds on previous research on coping by exploring the perceived effectiveness of strategies.

A key limitation of this study is that specific causes of stress are not identified. As data were collected at the completion of the university semester during a period where many students did not face academic challenges, the primary cause of stress may not have been academically-focused. Students commonly experience stress relating to finances, housing, future career prospects, or while waiting for exam results, and future research should seek to map coping strategy effectiveness onto specific causes of stress. This would enhance our understanding of the potential impact of interactions between stressor context and coping strategies, on mental health and wellbeing outcomes. Furthermore, this study does not provide insight into specific barriers to coping strategy use. As discussed, a potential cause of low engagement with strategies may be due to a lack of mental health literacy and understanding of effective coping strategy use. Future research should seek to examine higher education students’ mental health literacy and coping strategy effectiveness to understand the relationship between these variables.

Conclusion

Problem-focused coping strategy use, while resulting in less psychosocial distress than religion-dominant coping and no effective/no coping, is not significantly associated with lower levels of psychosocial distress compared to emotion-focused coping. Students should be encouraged to be flexible with their coping strategies and employ strategies based on the stressor and the resources and knowledge that they have. Universities and health services should seek to prevent high psychosocial distress levels by promoting effective coping strategy use and educating students on the benefits of both problem- and emotion-focused coping. By providing mental health literacy to students, they can have the opportunity to try different coping styles and be flexible in when and how many coping strategies they use. Providing students with resources to reduce stress can help them manage stress on their own and improve their university experience and success.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdulghani, Hamza Mohammad, Kamran Sattar, Tauseef Ahmad, and Ashfaq Akram. 2020. “Association of COVID-19 Pandemic with Undergraduate Medical Students’ Perceived Stress and Coping.” Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2020 (13): 871–81. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S276938.

- Akbar, Zarina, and Maratini Shaliha Aisyawati. 2021. “Coping Strategy, Social Support, and Psychological Distress Among University Students in Jakarta, Indonesia During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Frontiers in Psychology 12:694122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.694122.

- Alsubaie, M. Mohammed, Helen J. Stain, Lisa Amalia Denza Webster, and Ruth Wadman. 2019. “The Role of Sources of Social Support on Depression and Quality of Life for University Students.” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 24 (4): 484–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1568887.

- Andrade, Laura Helena, J. Alonso, Z. Mneimneh, J. E. Wells, A. Al-Hamzawi, G. Borges, E. Bromet, Ronny Bruffaerts, G. De Girolamo, and R. De Graaf. 2014. “Barriers to Mental Health Treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys.” Psychological Medicine 44 (6): 1303–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713001943.

- Biernacki, Christophe, Gilles Celeux, and Gérard Govaert. 2000. “Assessing a Mixture Model for Clustering with the Integrated Completed Likelihood.” IEEE transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 22 (7): 719–25. https://doi.org/10.1109/34.865189.

- Cabanach, Ramón González, Antonio Souto-Gestal, Luz González-Doniz, and Victoria Franco Taboada. 2018. “Perfiles de afrontamiento y estrés académico en estudiantes universitarios.” Revista de investigación educativa 36 (2): 421–33. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.36.2.290901.

- Carver, Charles S. 1997. “You Want to Measure Coping But Your Protocol’ Too Long: Consider the Brief Cope.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 4 (1): 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6.

- Chai, Penny Pei Minn, Christian Ulrich Krägeloh, Daniel Shepherd, and Rex Billington. 2012. “Stress and Quality of Life in International and Domestic University Students: Cultural Differences in the Use of Religious Coping.” Mental Health Religion & Culture 15 (3): 265–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2011.571665.

- Cohen, Sheldon, Tom Kamarck, and Robin Mermelstein. 1983. “A Global Measure of Perceived Stress.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24 (4): 385–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404.

- Dias, Cláudia, José F. Cruz, and António Manuel Fonseca. 2012. “The Relationship Between Multidimensional Competitive Anxiety, Cognitive Threat Appraisal, and Coping Strategies: A Multi-sport Study.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 10 (1): 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2012.645131.

- Dingle, Genevieve A., Rong Han, and Molly Carlyle. 2022. “Loneliness, Belonging, and Mental Health in Australian University Students Pre-and Post-covid-19.” Behaviour Change 39 (3): 146–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2022.6.

- Folkman, Susan, and Richard S. Lazarus. 1980. “An Analysis of Coping in a Middle-aged Community Sample.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 21 (3): 219–39.

- Folkman, Susan, Richard S. Lazarus, Scott Pimley, and Jill Novacek. 1987. “Age Differences in Stress and Coping Processes.” Psychology and Aging 2 (2): 171. https://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.2.2.171.

- Ford, Brett Q., James J. Gross, and June Gruber. 2019. “Broadening Our Field of View: The Role of Emotion Polyregulation.” Emotion Review 11 (3): 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919850314.

- Fornés-Vives, Joana, Gloria Garcia-Banda, Dolores Frias-Navarro, and Gerard Rosales-Viladrich. 2016. “Coping, Stress, and Personality in Spanish Nursing Students: A Longitudinal Study.” Nurse Education Today 36:318–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.08.011.

- Francis, Benedict, Jesjeet Singh Gill, Ng Yit Han, Chiara Francine Petrus, Fatin Liyana Azhar, Zuraida Ahmad Sabki, Mas Ayu Said, Koh Ong Hui, Ng Chong Guan, and Ahmad Hatim Sulaiman. 2019. “Religious Coping, Religiosity, Depression and Anxiety Among Medical Students in a Multi-religious Setting.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (2): 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16020259.

- Freire, Carlos, María del Mar Ferradás, Bibiana Regueiro, Susana Rodríguez, Antonio Valle, and José Carlos Núñez. 2020. “Coping Strategies and Self-efficacy in University Students: A Person-centered Approach.” Frontiers in Psychology 11:841. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00841.

- Gustems-Carnicer, Josep, and Caterina Calderón. 2013. “Coping Strategies and Psychological Well-being Among Teacher Education Students: Coping and Well-being in Students.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 28:1127–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0158-x.

- Hahn, Elizabeth A., Darren A. DeWalt, Rita K. Bode, Sofia F. Garcia, Robert F. DeVellis, Helena Correia, and David Cella. 2014. “New English and Spanish Social Health Measures Will Facilitate Evaluating Health Determinants.” Health Psychology 33 (5): 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000055.

- Hasselle, Amanda J., Laura E. Schwartz, Kristoffer S. Berlin, and Kathryn H. Howell. 2019. “A Latent Profile Analysis of Coping Responses to Individuals’ Most Traumatic Event: Associations with Adaptive and Maladaptive Mental Health Outcomes.” Anxiety, Stress & Coping 32 (6): 626–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2019.1638733.

- Holdsworth, Sarah, Michelle Turner, and Christina M. Scott-Young. 2018. “ … Not Drowning, Waving. Resilience and University: A Student Perspective.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (11): 1837–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1284193.

- Howard, Matt C., and Michael E. Hoffman. 2018. “Variable-Centered, Person-Centered, and Person-Specific Approaches: Where Theory Meets the Method.” Organizational Research Methods 21 (4): 846–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117744021.

- Huang, Long, Wansheng Lei, Fuming Xu, Hairong Liu, and Liang Yu. 2020. “Emotional responses and coping strategies in nurses and nursing students during Covid-19 outbreak: A comparative study.” PLoS One 15 (8): e0237303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237303.

- Hyde, Melissa K., and Simon R. Knowles. 2013. “What Predicts Australian University Students’ Intentions to Volunteer Their Time for Community Service?” Australian Journal of Psychology 65 (3): 135–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12014.

- Jenkin, Rebekah A., Samuel A. Garrett, and Kevin A. Keay. 2023. “Altruism in Death: Attitudes to Body and Organ Donation in Australian Students.” Anatomical Sciences Education 16 (1): 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.2180.

- Kaiser, Henry F. 1960. “The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 20 (1): 141–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000116.

- Kenntemich, Laura, Leonie von Hülsen, Ingo Schäfer, Maria Böttche, and Annett Lotzin. 2023. “Coping Profiles and Differences in Well-being During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Profile Analysis.” Stress and Health 39 (2): 460–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3196.

- Klainin-Yobas, Piyanee, Ornuma Keawkerd, Walailak Pumpuang, Chanya Thunyadee, Wareerat Thanoi, and Hong-Gu He. 2014. “The Mediating Effects of Coping on the Stress and Health Relationships Among Nursing Students: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 70 (6): 1287–98.

- Knoesen, Riané, and Luzelle Naudé. 2018. “Experiences of Flourishing and Languishing During the First Year at University.” Journal of Mental Health 27 (3): 269–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1370635.

- Kroenke, Kurt, Zhangsheng Yu, Jingwei Wu, Jacob Kean, and Patrick O. Monahan. 2014. “Operating Characteristics of PROMIS Four-item Depression and Anxiety Scales in Primary Care Patients With Chronic Pain.” Pain Medicine 15 (11): 1892–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12537.

- Larcombe, Wendy, Sue Finch, Rachel Sore, Christina M. Murray, Sandra Kentish, Raoul A. Mulder, Parshia Lee-Stecum, Chi Baik, Orania Tokatlidis, and David A. Williams. 2016. “Prevalence and Socio-Demographic Correlates of Psychological Distress among Students at an Australian University.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (6): 1074–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.966072.

- Lazarus, Richard S., and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer.

- Lee, Eun-Hyun. 2012. “Review of the Psychometric Evidence of the Perceived Stress Scale.” Asian Nursing Research 6 (4): 121–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004.

- Lin, I-Fen, and Hsueh-Sheng Wu. 2014. “Patterns of Coping Among Family Caregivers of Frail Older Adults.” Research on Aging 36 (5): 603–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027513513271.

- Liu, Chang, Melinda McCabe, Andrew Dawson, Chad Cyrzon, Shruthi Shankar, Nardin Gerges, Sebastian Kellett-Renzella, Yann Chye, and Kim Cornish. 2021. “Identifying Predictors of University Students’ Wellbeing During the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Data-driven Approach.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (13): 6730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136730.

- Mathew, Asha, and Ardith Z. Doorenbos. 2022. “Latent Profile Analysis–An Emerging Advanced Statistical Approach to Subgroup Identification.” Indian Journal of Continuing Nursing Education 23 (2): 127–133. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcn.ijcn_24_22.

- McGillivray, Cher J., and Aileen M. Pidgeon. 2015. “Resilience Attributes Among University Students: A Comparative Study of Psychological Distress, Sleep Disturbances and Mindfulness.” European Scientific Journal 11 (5): 33–48.

- Nylund, Karen L., Tihomir Asparouhov, and Bengt O. Muthén. 2007. “Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14 (4): 535–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396.

- Pété, Emilie, Chloé Leprince, Noémie Lienhart, and Julie Doron. 2022. “Dealing with the Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak: Are Some Athletes’ Coping Profiles More Adaptive Than Others?” European Journal of Sport Science 22 (2): 237–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.1873422.

- Pilkonis, Paul A., Seung W. Choi, Steven P. Reise, Angela M. Stover, William T. Riley, David Cella, and PROMIS Cooperative Group. 2011. “Item Banks for Measuring Emotional Distress From the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): Depression, Anxiety, and Anger.” Assessment 18 (3): 263–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191111411667.

- Posit team. 2023. “RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R.”

- Primack, Brian A., Ariel Shensa, Jaime E. Sidani, Erin O. Whaite, Liu yi Lin, Daniel Rosen, Jason B. Colditz, Ana Radovic, and Elizabeth Miller. 2017. “Social Media Use and Perceived social Isolation Among Young Adults in the US.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 53 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.010.

- R Core Team. 2022. “R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.”

- Reeve, Kristen L., Catherine J. Shumaker, Edilma L. Yearwood, Nancy A. Crowell, and Joan B. Riley. 2013. “Perceived Stress and Social Support in Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Educational Experiences.” Nurse Education Today 33 (4): 419–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.11.009.

- Rice, Kylie, Adam J. Rock, Elizabeth Murrell, and Graham A. Tyson. 2021. “The Prevalence of psychological Distress in an Australian TAFE Sample and the Relationships Between Psychological Distress, Emotion-focused Coping and Academic Success.” Australian Journal of Psychology 73 (2): 231–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1883408.

- Rosenberg, Joshua M., Patrick N. Beymer, Daniel J. Anderson, C. J. Van Lissa, and Jennifer A. Schmidt. 2019. “tidyLPA: An R Package to Easily Carry Out Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) Using Open-source or Commercial Software.” Journal of Open Source Software 3 (30): 978. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00978.

- Sagone,, Elisabetta, and Maria Elvira De Caroli. 2014. “A Correlational Study on Dispositional Resilience, Psychological Well-being, and Coping Strategies in University Students.” American Journal of Educational Research 2 (7): 463–71. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-2-7-5.

- Salman, Muhammad, Noman Asif, Zia Ul Mustafa, Tahir Mehmood Khan, Naureen Shehzadi, Humera Tahir, Muhammad Husnnain Raza, Muhammad Tanveer Khan, Khalid Hussain, and Yusra Habib Khan. 2022. “Psychological Impairment and Coping Strategies During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Students in Pakistan: A Cross-sectional Analysis.” Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 16 (3): 920–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.397.

- Schofield, Margot J., Paul O’halloran, Siân A. McLean, Christine Forrester-Knauss, and Susan J. Paxton. 2016. “Depressive Symptoms Among Australian University Students: Who is at Risk?” Australian Psychologist 51 (2): 135–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12129.

- Schwarz, Gideon. 1978. “Estimating the Dimension of a Model.” The Annals of Statistics 6 (2): 461–4.

- Scrucca, Luca, Michael Fop, T. Brendan Murphy, and Adrian E. Raftery. 2016. “Mclust 5: Clustering, Classification and Density Estimation Using Gaussian Finite Mixture Models.” The R Journal 8 (1): 289–317.

- Thayer, Robert E., J. Robert Newman, and Tracey M. McClain. 1994. “Self-regulation of Mood: Strategies for Changing a Bad Mood, Raising Energy, and Reducing Tension.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67 (5): 910. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.5.910.

- Theurel, A., and A. Witt. 2022. “Identifying Barriers to Mental Health Help-Seeking in French University Students during the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Creative Education 13 (2): 437–49. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2022.132025.

- Thompson, Mindi N., Pa Her, Anna Kawennison Fetter, and Jessica Perez-Chavez. 2019. “College Student Psychological Distress: Relationship to Self-Esteem and Career Decision Self-Efficacy Beliefs.” The Career Development Quarterly 67 (4): 282–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12199.

- Vidas, Dianna, Joel L. Larwood, Nicole L. Nelson, and Genevieve A. Dingle. 2021. “Music Listening as a Strategy for Managing COVID-19 Stress in First-year University Students.” Frontiers in Psychology 12:647065. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647065.

- Wang, Haobi, Ting Kin Ng, and Oi-ling Siu. 2023. “How does Psychological Capital Lead to Better Well-Being for Students? The Roles of Family Support and Problem-focused Coping.” Current Psychology 42 (26): 22392–403.

- Wood, Douglas E. 2015. “National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Lung Cancer Screening.” Thoracic Surgery Clinics 25 (2): 185–97.

- Yan, Anson Tang Chui. 2019. “Prediction of Perceived Stress of Hong Kong Nursing Students With Coping Behaviors Over Clinical Practicum: A Cross-sectional Study.” Journal of Biosciences and Medicines 7 (5): 50–60. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbm.2019.75008.

- Ye, Zhi, Xueying Yang, Chengbo Zeng, Yuyan Wang, Zijiao Shen, Xiaoming Li, and Danhua Lin. 2020. “Resilience, Social Support, and Coping as Mediators Between COVID-19-Related Stressful Experiences and Acute Stress Disorder Among College Students in China.” Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 12 (4): 1074–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12211.

- Zaman, Noshi Iram, and Uzma Ali. 2019. “Autonomy in University Students: Predictive Role of Problem Focused Coping.” Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research 34 (1): 101–14. https://doi.org/10.33824/PJPR.2019.34.1.6.