ABSTRACT

Assessment of student learning is commonly understood as a seemingly objective measurement of learning outcomes. It is seen as fair that assessment targets students’ abilities – not their identities or personalities. This idea fails to acknowledge how assessment transforms its object, the students, often in unintended ways. While higher education research has largely emphasised the impact of assessment on student learning, the ontological question of how assessment shapes students has remained marginal. This is despite assessment being a part of the fabric of life in higher education: examinations, assignments, grades, rubrics, rankings, and metrics characterise the student experience. The present study addresses this knowledge gap by reviewing empirical studies on how assessment shapes student identities through a theory-driven integrative review of 32 articles (2007–2023). First, these studies are summarised to understand how they conceptualise ‘identities’, what kinds of assessment practices they depict, and what the reported influences on student identities are. Second, a conceptual synthesis provides a metatheory on how assessment transforms student identities in higher education. This theorisation suggests that assessment shapes students through the ontological mechanisms of (1) gatekeeping, (2) legitimisation, (3) concretisation, (4) socialisation and (5) individualisation. Moreover, the theorisation considers students’ own agency over their identity development. Overall, this study emphasises the crucial, hitherto overlooked role of assessment in shaping students’ professional and personal identities in higher education. This study proposes a research agenda to better understand student identity formation in and through assessment.

Introduction

When students attend higher education, they not only learn new skills and knowledge but become someone new. Universities shape students’ subjectivities their 'identities, values, and sense of what it means to become citizens of the world’ (Giroux Citation2009, 460). This transformative potential of higher education has been a focal point in recent studies, spanning from explorations of student formation to investigations of students’ professional identities (Brooks and O’Shea Citation2021; Dall’Alba and Barnacle Citation2007; Kinchin and Gravett Citation2022; Marginson Citation2023; Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021; Trede, Macklin, and Bridges Citation2012).

Yet, the role of educational assessment has been underplayed in these ontological conversations (Nieminen and Yang Citation2023). Assessment refers to ‘the graded and non-graded tasks, undertaken by an enrolled student as part of their formal study, where the learner’s performance is judged by others (teachers or peers)’ (Bearman et al. Citation2016, 547). The present study addresses how assessment shapes student identities. This goal may seem inappropriate in the current landscapes of higher education. What do student identities have to do with assessment? Assessment has been traditionally understood as a seemingly objective measurement of student learning outcomes, not student identities or personalities (Boud et al. Citation2018). This follows a meritocratic ideal: in order to be fair, assessment should reward students for their merits and not for their personal characteristics (Zwick and Dorans Citation2016). Testaments to such thinking are the widespread practices of ‘bias reduction’ such as double-marking and anonymous feedback.

However, unlike many measurement practices, assessment changes its target. While assessment research has largely explored the effects of assessment on learning, research has also acknowledged that assessment shapes how individuals and groups see themselves (Nieminen, Moriña, and Biagiotti Citation2024; Pryor and Crossouard Citation2008; Citation2010; Stobart Citation2016; Torres, Strong, and Adesope Citation2020; Wiliam, Bartholomew, and Reay Citation2004). School-based studies have shown that assessment steers student identities towards certain educational values and ideologies (Ecclestone and Pryor Citation2003; Kasanen and Räty Citation2002). For example, Löfgren, Löfgren, and Lindberg (Citation2019) discussed how ‘grades at school can be seen as labels of who you are’ (271) in contexts where assessment policies emphasise rankings and competition. In this way, seemingly objective practices, such as grades, may become a part of students’ understanding of themselves rather than simply measuring their abilities. Yet, the focus on identity remains at the margins of assessment research (e.g. Coombs and DeLuca Citation2022). Simultaneously, to date, assessment has received limited attention in research on student identities (Nieminen and Yang Citation2023). This is surprising given the substantial role assessment plays in the contemporary ‘measured university’ with its strong focus on numbers, metrics, rankings, and competition (Peseta, Barrie, and McLean Citation2017). In this context, perhaps more than ever in history, assessment is a ‘part of the fabric of life’ as it has become ‘a powerful social tool because of the consequences for the life chances of those assessed’ (Stobart Citation2016, 56). There is thus an acute need to understand how assessment shapes students’ identities in higher education.

While it can be hypothesised that assessment plays a significant role in students’ identity formation processes, research in this area is fragmented. There are pockets of inspiring studies (e.g. McAlpine Citation2005) and a recent conceptual study (Nieminen and Yang Citation2023), yet no earlier research syntheses to provide a metatheory on how assessment shapes student identities. This study brings together the shattered pieces of evidence through an integrative review. This study builds our understanding of assessment as an ontological practice with social and ethical consequences for how students are shaped and shape themselves in higher education. In doing so, I propose a research agenda to understand student identity formation in and through assessment. If learning in higher education means ‘to become someone’ (Dall’Alba and Barnacle Citation2007), then the ontological functioning of assessment in students’ identity formation processes needs to be thoroughly understood. As an integrative review, this study mainly focuses on building scholarly knowledge about assessment, with its primary audience being researchers in assessment and higher education. At the same time, this review challenges teachers, assessment designers and policy-makers to consider the often unintended role of assessment in student identity formation. My main focus is on professional identities rather than on personal identities, given that professional identity development is commonly seen as a crucial purpose of higher education (Trede, Macklin, and Bridges Citation2012). Yet, as will be seen, these ideas may not be easily separated.

Research questions

This study provides both a summary and an integrative synthesis of earlier studies on how assessment has shaped student identities in higher education.

The summary addresses three questions:

How has empirical research on assessment and feedback in higher education conceptualised student identities?

What kinds of research designs and methods have been used?

What are the findings regarding how assessment shapes student identities?

Based on this summary, a further integrative synthesis is constructed. This synthesis builds an explanatory theory, addressing the main research question in this study: through what kinds of social mechanisms does assessment shape student identities? This explanatory theory can be used in future research and practice to better understand and facilitate student identity formation in assessment.

Methods

Integrative review

This review follows an integrative review methodology. Integrative reviews critique and synthesise earlier literature by forming new frameworks and perspectives on the investigated topic (Torraco Citation2005). They do not only summarise empirical evidence (cf. systematic reviews) nor scope literature and pinpoint avenues for further research (cf. scoping reviews), but produce metatheory and push forward research agendas. Integrative review is a particularly apt review type for this study as they ‘build bridges across communities of practice in the field and uncover[s] connections to other related disciplines.’ (Cronin and George Citation2023, 175) This review type is thus adequate to synthesise knowledge from various fields of literature, such as educational psychology, sociology and philosophy, that rely on differing epistemological and ontological standpoints towards the idea of student identities. Moreover, they can synthesise knowledge from different disciplinary and cultural contexts in which assessment might be implemented in rather different ways (see Cronin and George Citation2023).

Overall, this study represents a relatively broad integrative review that synthesises emerging topics requiring initial synthesis (Torraco Citation2005). I follow the five stages of integrative reviews by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005): problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation.

Literature search

The primary literature search was conducted in March 2023 by using Covidence, which is a reference management system for literature reviews. The search drew on a recommended hybrid strategy of combining a database search with backward and forward snowballing processes to ensure that most, if not all, potential references were identified (Wohlin et al. Citation2022).

The primary search included five databases: Scopus, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) (via EBSCOhost), Web of Science, PsychInfo (via ProQuest), and PubMed.Footnote1 There was no time limitation in the search. The search terms are presented in . These search terms were used to search publications based on their title, abstracts and keywords. The final search protocol involved two terms related to identity, following Danielsson et al. (Citation2023). The search term ‘identit*’ was used rather than ‘professional identity’, a prominent area in higher education research (Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021; Trede, Macklin, and Bridges Citation2012), as it includes the latter yet may have resulted in more diverse results.

Table 1. Search terms of the study.

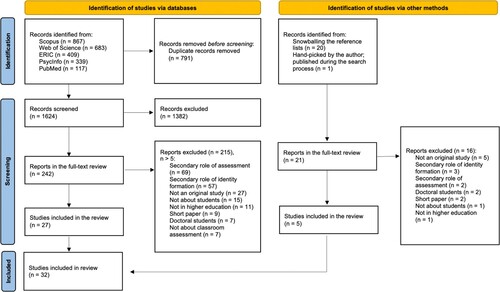

presents the flow diagram of the search process. First, all titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (). Notably, the review focused on original studies that focused on the particular aspect of assessment in student identity formation. Next, the 242 studies chosen for full-text review were read against the same criteria. depicts the reasons for exclusion in this final stage. 27 studies were chosen for data extraction.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Throughout the search process and up until the final data analysis in August 2023, I used citation tracking in Google Scholar with an alert for search terms ‘assessment’, ‘identity’ and ‘education’ (forward snowballing). The abstracts (and potentially full texts) of the potentially relevant sources were checked, and one additional study was identified to the dataset (Liao et al. Citation2023). The reference lists of the included 27 studies were screened (backward snowballing), leading to the identification of four additional studies. The final data corpus thus consisted of 27 + 4 + 1 = 32 studies.

Data extraction and analysis

introduces the data extraction table. The extraction table was purposefully open-ended to enable in-depth interpretation and meaning-making.

Table 3. Extraction table.

Analysis method: summary

The studies were categorised concerning how they conceptualised ‘identities’ and what kinds of research designs and methods they undertook. For this purpose, the categorisation by Radovic et al. (Citation2018) was used. Radovic et al. (Citation2018) systematically reviewed identity research in mathematics education, yet the categorisation system has been used successfully in other review studies beyond mathematics education (Simpson and Bouhafa Citation2020).

Radovic et al. (Citation2018) produced three main dimensions through which varying epistemological and ontological stances towards ‘identity’ could be understood. The subjective/social dimension considers whether one’s conceptualisation is sensitive to the lived, subjective sense of identity or whether it emphasises identities as social products that are produced through social practices and discourses. Second, the representational/enacted dimension concerns the varying levels of emphasis towards identity as something constructed through language. The enacted dimension emphasises that identities are constructed in action through activities. Finally, the change/stability dimension is related to how malleable identity is seen to be: whether it is constantly renegotiated or changes under certain circumstances only.

Through these three dimensions, Radovic et al. (Citation2018) formulated five categories to understand how ‘identity’ is defined, conceptualised and operationalised in research. The categories are:

Identity as individual attributes, emphasising representational and subjective dimensions

Identity as narratives, emphasising representational and subjective dimensions

Identities as a relationship with a specific practice, emphasising representational and social dimensions

Identities ways of acting, emphasising enacted and social dimensions

Identities as afforded and constrained by local practices, emphasising representational and social dimensions

For further examples of these categories, please refer to the next sections, particularly .

Table 4. The conceptualisations of student identities.

Each study was categorised into one category only. While I kept the analysis sensitive for using multiple categories, this was unnecessary. I remained sensitive to other emerging categories and decided to divide studies using a poststructural conceptualisation of ‘identities’ as a new category.

The framework enabled me to interpret the studies beyond what was explicitly stated. Many studies explicitly conceptualised ‘identity’ yet did not align their data collection and analysis methods with this conceptualisation. Moreover, the framework allowed me to understand the differences in seemingly similar studies. To provide an example, the studies by Alizadeh et al. (Citation2018) and Wiewiora and Kowalkiewicz (Citation2019) both addressed ‘leadership identities’ yet, in fact, drew on somewhat different understandings of whether leadership identity is an individual attribute (Alizadeh et al. Citation2018) or whether it is negotiated socially within a particular community of practice (Wiewiora and Kowalkiewicz Citation2018).

Analysis method: synthesis

The further synthesis of the studies answered the main research objective: how does assessment shape student identities? This synthesis followed Cronin and George’s (Citation2023) formulation of redirection for data synthesis in integrative reviews. Redirection ‘organizes domain knowledge by structuring it so that insights that promote new kinds of research emerge’ (Cronin and George Citation2023, 171). This redirection was both inductive and deductive, namely, it made use of earlier ideas on assessment and identity (e.g. Nieminen and Yang Citation2023; Stobart Citation2016) but remained sensitive to the studies being reviewed.

The synthesis uncovered the social mechanisms through which assessment shapes student identities. The analysis produced an explanatory theory of the interrelation between assessment and student identities. A starting point for such theorising was the conceptual study by Nieminen and Yang (Citation2023) that outlined how assessment shapes student identities and might also provide students with the means to shape themselves reflexively.

Summary

Overview of the studies

The 32 studies were predominantly conducted in Anglo-Saxon contexts (12 in Europe, eight in North America, and six in Australasia), with four studies conducted in Asia and one in the Middle East. One study included more than one national context. Twenty-four studies took a disciplinary approach, with eight studies taking a general approach to assessment. The most common disciplines were teacher education (n = 9), language education (n = 4), medical education (n = 3) and business and administration (n = 3). The studies were published rather recently, between 2007-2023. Five of the studies had a longitudinal research design.

E-portfolios were the most commonly addressed assessment practice (n = 8). All specific practices beyond e-portfolios were only mentioned twice (authentic assessment and peer feedback) or once (e.g. examinations, audio journals, blogging, ungrading, test proctoring, Universal Design for Assessment).

Conceptualisations of identity and the accompanying research designs

presents the findings for RQ1 and RQ2.

Identity as individual attributes (2/32)

Two studies addressed identity as an individual attribute that was ontologically separate from its social context. Such studies relied on quantitative or mixed methods, with predetermined items for measuring students’ identities. These studies took an ‘interventionist’ approach to identity development, claiming that interventions could nurture students’ identities in desirable ways.

These studies portrayed assessment as a powerful tool for shaping students’ individual and rather stable identities. Both studies were conducted in medical education. Alizadeh et al. (Citation2018) examined how reflection and feedback could advance medical students’ leadership identities. The feedback intervention successfully improved the level of leadership identity in the intervention group. Sidebotham et al. (Citation2018) examined the power of e-portfolios in the midwifery students’ capstone projects for students’ sense of identity. 73% (n = 22) of the participants agreed that completing the portfolio assessment helped them develop their sense of identity (86).

Identity as narratives (4/32)

Four studies considered identity as narratives. One’s identity narratives were seen to represent wider social and cultural discourses and practices. Narratives were not just the object of study but also the method of choice to collect data. These studies were highly representational as they used narrative inquiry to collect data about students’ identity formation in assessment in retrospect.

Assessment was portrayed as a venue for narrating one’s narrative. This was seen in Andrew’s (Citation2012) study about how reflective journaling not only reveals students’ identities but provides the means to construct identity narratives. This study analysed discursive positionings to showcase how students, in their journals, took part in micro- and macro-narratives as they produced ‘stories that demonstrated their enhanced sensitivity to culture as a part of individuals’ identities’ (Andrew Citation2012, 70). Journaling as an assessment practice captured students’ auto-biographies and learning histories: ‘These are stories about becoming, not just learning.’ (71) Likewise, Nguyen (Citation2013) investigated e-portfolios as ‘a living portal, whereby identity is shared with others and reimagined in narrative and conversation’ (Nguyen Citation2013, 144).

Assessment also shaped students’ identity narratives. Nieminen and Pesonen (Citation2020) examined inaccessible assessment practices that influenced the identity narratives of students with disabilities. This study concluded that inaccessible assessment is a matter of students’ narratives they produce about themselves as ‘diverse learners’. Liao et al. (Citation2023) studied clinical assessment practices in the construction of professional identities of medical trainees. Their analysis showed two plotlines in students’ narratives: ‘striving to thrive’ and ‘striving to survive’. What connects these two studies is that they considered the influences of wider macro-level discourses on students’ identity narration. Whereas Nieminen and Pesonen (Citation2020) discussed broader discourses of disability as a context for assessment, Liao et al. (Citation2023) emphasised the importance of contemporary assessment regimes and their focus on performativity and instrumentalism.

Identities as a relationship with a specific practice (12/32)

11 studies considered identity as the relationship individuals establish with professional practice. Often, identity was connected to the ideas of ‘belonging’ and ‘membership’ in a disciplinary or professional community. This category differs from the narrative studies with a greater emphasis on ‘analyzing how shared meanings are negotiated in a particular practice, with less interest in how big social discourses are negotiated’ (Radovic et al. Citation2018, 30). Methodologically, these studies drew on qualitative surveys, interviews and reflective texts.

Five studies considered the opportunities assessment provides for legitimate participation in one’s profession, harnessing assessment for becoming a future professional. Dantas-Whitney (Citation2002) showed how audiotaped journals made students more aware of the formation processes of their multiple, dynamic and intersecting identities. Wiewiora and Kowalkiewicz (Citation2019) demonstrated how authentic assessment could develop students’ leadership identities in management studies as they ‘started building the authentic concept of themselves as leaders’ (Wiewiora and Kowalkiewicz Citation2019, 426). Three studies considered how assessment contributes to developing in-service teachers’ teacher identities. Doyle et al. (Citation2021) and Fu et al. (Citation2022) focused on teachers’ assessment identities, demonstrating how partaking in assessment is a powerful tool for nurturing students’ developing assessment identities.

Two studies focused on employability. Bennett et al. (Citation2016) examined how e-portfolios promote music students’ career identities. They found that e-portfolios enable one to construct a fluid self-portrait with multimodal elements. Blaj-Ward and Matic (Citation2021) studied how assessment mobilises resources for developing students’ pre-professional identities in various disciplines. This study emphasises that students start positioning themselves in professional fields as future employees through assessment.

Five studies examined assessment as a social practice that developed and regulated students’ sense of belonging. For example, Li and Han (Citation2023) examined feedback practices from the viewpoint of academic discourse socialisation. They shed light on how feedback built spaces for il/legitimate participation for two Chinese international students in a UK university. In a new study environment, their research participants had to reinvent their academic identities, and feedback played both an empowering and disempowering role in these processes (see also Torres and Ferry Citation2019). Similarly, Skyrme (Citation2007) discussed the role of examinations and tests in socialising two Chinese international students to the academic culture in New Zealand. This study concluded that the uniform, examination-driven assessment culture gave students narrow ways of defining their identities. On the other hand, Chapman (Citation2017) discussed how assessment could be used to lower the imposter syndrome of mature students to increase their sense of belonging to higher education.

Identities as a way of acting (2/32)

This identity category shifts the focus from representational to enacted identities. Identity was seen as a ‘constantly changing process where identities are negotiated in moment-by-moment interactions’ (Radovic et al. Citation2018, 30; original emphasis). Such studies rely on observational data or ethnographies.

Two such studies were identified. In these studies, assessment enabled students to act professionally and thus develop their professional identities. Zheng and Huang (Citation2017) and Zheng and Chai (Citation2019) used video data from peer feedback activities to explore how Chinese students developed their identities in the context of academic English. Both studies used the concept of Communities in Practice to analyse how students needed to negotiate their social roles and identities during the peer feedback task. These studies emphasised the power of peer feedback in shifting students from being peripheral participants to legitimate participation.

Identities as afforded and constrained by local practices (8/32)

Eight articles focused on how student identities are afforded and constrained by assessment practices. In these studies, the subjective nature of identities was not emphasised, but instead, ‘relevance was given to particular contexts and how they provided resources that made some identities possible’ (Radovic et al. Citation2018, 31). The focus was thus on assessment design as a social structure for identity formation. These studies utilised naturalistic case studies with varying methodologies to explore how assessment and feedback practices construct student identities locally.

Many articles focused on how assessment could support the development of students’ professional identities. Yet, unlike the studies on identity as a relationship with specific practices, the focus here was less theoretical and more closely connected to the affordances that assessment design provides for identity development. Houghton (Citation2013) discussed the affordances of continuous assessment on ‘helping make identity-development visible’ (314). This study emphasised the importance of harmonising summative and formative assessment in such work. Impedovo, Ligorio, and McLay (Citation2018) used the dialogical self-theory to understand the affordances of an e-portfolio for students’ identity formation. They noted that a coherent structure was needed to ‘catch a glimpse of participants’ ontological experience of becoming a professional’ (Impedovo, Ligorio, and McLay Citation2018, 8). If Impedovo, Ligorio, and McLay (Citation2018) and Silva et al. (Citation2015) reframed e-portfolios as a practice for identity formation – and not just for learning – Torres and Anguiano (Citation2016) did the same for feedback. When feedback was presented as a dialogic process, students could engage their multiple identities in the writing process and develop them as ‘not fixed but fluid and constantly undefined’ (Torres and Anguiano Citation2016, 9).

Two studies examined the hindrances that assessment sets for constructive identity formation. Belluigi (Citation2020) examined assessment in creative arts, noticing that it hinders the development of students’ authentic selves and authorships. This was connected to the performativity cultures of assessment. Rather than developing their artistic identities, students were shown to strategically play ‘the assessment game’ (Belluigi Citation2020, 16). Kjærgaard, Mikkelsen, and Buhl-Wiggers (Citation2023) studied the affordances and hindrances of ungrading: turning graded assessment in the first year of business studies to pass/fail. This study provided nuanced findings on the tensions of how students had to renegotiate their identities in this new culture. While some students felt ungrading made them feel ‘like a whole human being’ rather than a number (Kjærgaard, Mikkelsen, and Buhl-Wiggers Citation2023, 565), others lamented their ‘loss of individual identity’ (568).

Two studies considered how students could use their personal identities as a resource in assessment. Munday, Sajid, and Reader (Citation2014) discussed blogging as a visual diary assessment that enables students to draw on their own cultural identities in early childhood education: students’ personalities could be presented in the final assessment products. Hein and Miller (Citation2004) explored authentic assessment from this viewpoint in Chicano studies. Students were asked to situate their own families within a historical framework. In doing so, they had to connect their personal and professional identities.

Identities as subjectification (4/32)

Four studies stood out with their poststructural approach to identity formation. These studies relied on Foucault’s concept of ‘the subject’, namely, how the student subject is formed within particular assessment practices and discourses (Mayes Citation2010). The datasets in these studies varied from interviews (Barrow Citation2007) to interviews, documents and emails (Lee and Fanguy Citation2022).

Barrow (Citation2006) used Foucault’s terminology to understand assessment as a technology of the self that shapes the student subject: ‘All assessment places students in a web of power, in which they are subject to the application of the expert knowledge of the lecturer who is acting as an assessor.’ (369) A key idea within such a web of power was the neoliberal subjectivity that assessment upheld. Sutton and Gill (Citation2010) discussed the ‘competitive, individualised consumer identity’ that assessment constructs (9). They identified grades as a powerful numbering practice that upholds this identity construction through the ‘economic imperative’ they pose (Sutton and Gill Citation2010, 10). Lee and Fanguy (Citation2022) focused on online proctoring in shaping the student subject through a neoliberal ethos of competition and marketisation. Proctoring was seen as a surveillance mechanism ‘firmly grounded in the discourse of fairness, placing student bodies under increased teacher surveillance’ (485).

Synthesis

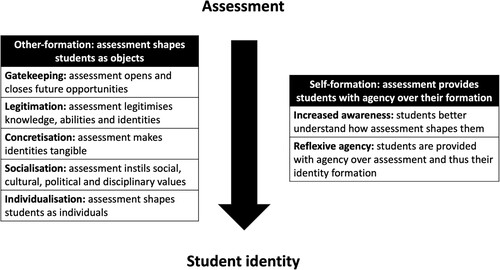

Here, I present the explanatory theory that outlines how assessment shapes student identities, namely, through which social mechanisms this occurs and how, based on the 32 studies. The section is divided into two parts with respect to how much agency students are seen to have over their identity formation, following the theorisation by Nieminen and Yang (Citation2023) (see also Chávez, Fauré, and Barril Madrid Citation2023). First, I present five ontological mechanisms through which assessment shapes students, seeing students as ‘objects’ whose formation is mostly determined by others (‘other-formation’ as phrased by Nieminen and Yang Citation2023). These mechanisms emphasise the non-neutral nature of assessment as a thoroughly social practice. Moreover, they emphasise the power that higher education holds upon students through assessment. Second, I focus on how assessment could provide students with reflexivity to shape themselves (‘self-formation’ in Nieminen and Yang Citation2023).

These ideas are summarised in . The reader should be cautious that in this figure, the terms ‘assessment’ and ‘identity’ are both used in a general sense. Assessment might refer to diverse practices such as high-stakes examinations, peer feedback activities, or e-portfolios. Likewise, ‘identity’, as I have outlined in the previous section, may refer to at least six differing research traditions (Radovic et al. Citation2018). For example, if ‘identity’ refers to identity narratives, the arrow in the middle of the figure relates to how assessment shapes the narratives students tell about themselves. Or, if ‘identity’ is taken as a relatively stable psychological attribute, the arrow would represent the changes within the individual, perhaps identified via quantitative instruments. While the arrow looks seemingly simplistic – as if assessment had a direct influence on student identities – I hope the list of mechanisms in reminds the reader about the complexity, intertwinement and context-specificity of these processes. These ontological mechanisms are not deterministic but they nevertheless provide the means for student identity formation in powerful ways. Finally, this list is not exhaustive. It synthesises the studies in this review and thus only addresses what has been explicitly discussed in past work.

Other-formation: assessment shapes students as objects

Five ontolological mechanisms were discussed to form student identities in assessment. These five technologies are fundamental: they are present in all assessment situations with varying levels of intensity. They are not separate but intersect and overlap in complex ways. At the same time, each technology provides a unique way to understand how assessment shapes student identities.

Gatekeeping: assessment opens and closes future opportunities

The most obvious example of how assessment shapes students’ identities is its gatekeeping role. This refers to what Biesta (Citation2009) called a qualification purpose of education. Through its ‘stakes’, assessment has particular power on student identities over other teaching and learning activities. Even though assessment in higher education rarely has ‘high’ stakes, it still opens and closes spaces for students. Grades and Grade Point Average (GPA) regulate students’ future opportunities in different ways in various national and institutional contexts. Yet, the influence of these on students’ future lives is rarely irrelevant. One helpful way to understand the gatekeeping role of assessment is to pay attention to the ‘splitting moment’ of assessment that occurs as summative assessment splits students into pass/fail or A/B/C/D/F (Cabral and Baldino Citation2019). This splitting moment is always present in assessment; it is imperative to understand the gatekeeping role of these moments for student identities.

In this dataset, the gatekeeping role of assessment was tied to questions of future employability and job opportunities (Blaj-Ward and Matic Citation2021). In Kjærgaard, Mikkelsen, and Buhl-Wiggers’s (Citation2023) study about gradeless learning in first-year business studies, some students were anxious about future opportunities without the prospect of high grades. Some studies explored the influence of failure on student identities, noting that failure in assessment sets various trajectories for ‘failed’ or ‘successful’ identities to develop (Skyrme Citation2007). Such failure caused a loss of self-esteem as students’ ‘identity as a capable learner bec[ame] threatened’ (Sutton and Gill Citation2010, 9).

Legitimation: assessment has particular legitimacy in shaping students

Assessment has particular power over student identities through the legitimate knowledge it produces. Legitimation refers to the act of making something legitimate. Assessment signals which goals, abilities and forms of knowledge are deemed legitimate. Students may consider assessment information as legitimate and seemingly ‘objective’ even though assessment in higher education is rarely standardised nor psychometrically solid. As Andrew (Citation2012) pondered, teachers are in a position of power concerning student identity formation. Assessment encapsulates ‘the rules for the production of ‘truth’ in the discipline’ and incites students to ‘consider constantly his or her being concerning this ‘truth’.’ (Barrow Citation2006, 364)

Yet, not all assessment practices hold the same legitimacy over student identities. Often, seemingly objective practices such as tests and examinations may be perceived as particularly legitimate in determining students’ abilities (see Nieminen and Lahdenperä Citation2024). This is a disciplinary matter, too, as certain assessment practices may be considered legitimate in science but not in arts. For example, student-centred practices, such as self- and peer-assessment, may be considered illegitimate in natural sciences, making them less powerful for guiding students’ identity formation than examinations (Nieminen and Lahdenperä Citation2024).

In some studies, assessment information was considered legitimate in unquestionable ways. For example, in Nieminen and Pesonen (Citation2020), inaccessible assessment strongly influenced students’ identity narratives. The students did not consider that assessment itself may be illegitimate and thus should not impact one’s identity this heavily. Likewise, in Li and Han (Citation2023), a Chinese international student considered the tutor’s feedback comments so powerful that she came to understand themselves as an ‘illegitimate EAL [English as an additional language] writer with a limited right to make her voice heard’ (10). On the other hand, many studies noted that assessment can redetermine what counts as legitimate knowledge. In Hein and Miller (Citation2004) and Munday, Sajid, and Reader (Citation2014), students’ personal identities, cultures and histories were placed at the centre of assessment. When students could showcase their selves rather than suppress them, these identities were legitimised as legitimate knowledge through assessment.

Concretisation: assessment makes identities tangible

Concretisation refers to rendering something concrete, to making something real by giving it a tangible form. Indeed, assessment turns its target tangible. Usually, assessment targets students’ abilities and thus provides students with ways of understanding themselves as more or less capable future practitioners. Only when an ability is assessed can its development be planned, mapped and predicted; only then can interventions be directed towards it. The point here is not that assessment makes identities ‘visible’ but that assessment renders them as concrete and real. The question of which aspects of student learning and identity formation assessment rendered visible was a focal point in many studies reviewed. This is a matter of assessment design, given that different types of assessment concretise student abilities and identities in varying ways.

This constitutive nature of assessment was seen in the way assessment provided the means to concretise students’ professional identity formation processes. Identity formation became something that could be planned, measured and set under an intervention (Alizadeh et al. Citation2018; Sidebotham et al. Citation2018). Bennett et al. (Citation2016) noted how e-portfolios not only deposit students’ professional identities but constitute them and, in doing so, provide the means to address the formation of these identities explicitly: ‘ … they [ePortfolios] are vehicles through which identity is negotiated and constructed (…) ePortfolios facilitate, make explicit and enable the (…) negotiation of aspects of identity’ (115). Assessment rendered the boundaries and intersections of students’ ‘professional’ and ‘personal’ identities tangible, enabling various stakeholders to discuss and shape these intersecting identities (e.g. Silva et al. Citation2015).

Other studies explored the dehumanising aspect of assessment as it reduced complex identities into simplistic forms of data, such as grades. Some studies discussed how uniform assessment practices provided one dimensional and restricted ways for students to develop their identities (Skyrme Citation2007). Chapman (Citation2017) discussed how assessment positions students within a hierarchy of success: with grades, students could compare themselves to others in seemingly simplistic and objective ways.

Socialisation: assessment promotes certain ways of participation

The aspect of socialisation was the most explicitly discussed technology in this dataset. Assessment instilled various social, cultural, political and disciplinary norms, values and ideologies that again shaped students as professional agents. In Biesta’s (Citation2009) words, through assessment, ‘we become members of and part of particular social, cultural and political ‘orders’’ (40). Many studies intentionally used assessment to socialise students in professional communities, such as in the studies discussed in the section for ‘Identities as a relationship with a specific practice’. I will not repeat those words here. These studies used assessment (and authentic assessment in particular) to train students to act as professionals through professional values and identities (Alizadeh et al. Citation2018; Li and Han Citation2023).

Another set of studies explored the unintended aspects of socialisation. Belluigi (Citation2020) discussed ‘the tacit and habitual ways’ through which summative assessment promoted a ‘hidden curriculum’ (6) in arts education. Summative assessment hindered students’ authentic growth as artists through a ‘loss of ownership and sense of discomfort with being positioned as pedagogised subjects rather than future artists.’ (Belluigi Citation2020, 14) Other studies similarly explored the values of neoliberal, marketised higher education that assessment imposed on student identity formation (Lee and Fanguy Citation2022).

Individualisation: assessment shapes students as individuals

All these 32 studies, in one way or another, considered the formation of the student subject in assessment as an individual. That is, wider systems of power operate on the level of an individual, as assessment concerns the learning and abilities of individual students – not groups or communities (Barrow Citation2006). Assessment formed student subjects in ways that resisted communal practices and ideals. In many papers, such an individualisation was connected to neoliberal, acontextual and competitive underpinnings – a particular, contemporary way of understanding ‘the self’ (Lee and Fanguy Citation2022). Fundamentally, this technology reminds us that assessment teaches students to understand themselves as individuals. In this way, students were ‘alienated from their academic community’ (MacKay et al. Citation2019, 318).

Many studies considered how ‘the self’ was constituted in relation to ‘others’. For example, many studies addressed the idea of leadership identity: what kind of a leader will I be for others? (Wiewiora and Kowalkiewicz Citation2019) Likewise, the studies on teacher assessor identities considered teachers’ individual identities but only in relation to the teaching profession, assessment policies and students (e.g. Doyle et al. Citation2021). In many studies, students’ communal identities were ‘individualised’ through assessment: in Silva et al. (Citation2015), one student brought Deaf culture as a part of his individual assessment.

Kjærgaard, Mikkelsen, and Buhl-Wiggers’s (Citation2023) study about gradeless learning is an important example of the individualisation of students. As grades – a profound technology of individualisation – were removed, students felt a part of a learning community but lamented their loss of individual identity. They report the case of Camile who explained that grades ‘make for a self-centred ego culture’ but in the gradeless environment ‘we’re much more willing to help each other by sharing notes, ideas, and materials.’ (Kjærgaard, Mikkelsen, and Buhl-Wiggers Citation2023, 567) Simultaneously, Camile felt that ‘without grades she had lost an important signifier of who she was.’ (568) This study shows how deeply the idea of individualism is ingrained in assessment.

Self-formation: assessment provides students agency over their formation

Two ideas were derived to denote how assessment provides students with agency over their own formation. This is what Nieminen and Yang (Citation2023) called ‘self-formation’ in assessment (see also Marginson Citation2023).

Increased awareness of identity formation

Many studies described how assessment increased students’ awareness of their own identity formation. Students rarely have real agency over assessment policy and practice. However, by making identity formation tangible, students could better understand how their identities were being formed, by whom, and for what purposes. Fittingly, Hein and Miller (Citation2004) called this an ‘awakening’ (315).

Andrew (Citation2012) reported how, through reflective journaling in community placements, students became more aware of and sensitive to the various cultures in New Zealand and their own identities within. Likewise, in Wiewiora and Kowalkiewicz (Citation2019), students became more aware of their leadership identity as they took part in authentic assessment. The authors argue that self-awareness is ‘one of the basic components of authentic leadership’ (8), and indeed one of their participants reported: ‘This experience [authentic assessment] has certainly enlightened me as to the type of manager I hope to be.’ (8) Fu et al. (Citation2022) explored how teacher students could become self-aware of their developing teacher identities. One of the participants summarised how e-portfolios promote one’s awareness of their formation:

For so many students self-awareness doesn't always come very easily but when you have a portfolio that you make that focuses on your abilities, all of a sudden, you're looking at yourself and saying oh actually this is valuable; this is a valuable part of me; this is something valuable that I have learned. (Sophie in Fu et al. Citation2022, 12)

Reflexive agency over identity formation

In some studies, assessment provided students with real agency over their own identity formation (see Marginson Citation2023). In these cases, assessment allowed students to set rules for how their identities were shaped, by whom, and why. This way, the students could redefine their own identities. As Nguyen (Citation2013) aptly phrased it, in these cases, assessment provided students with the means of ‘reading and writing their lives.’ (139)

Many studies reported how students could showcase their authentic selves in assessment. This finding resists the idea of students being the mere objects of assessment, only being able to demonstrate their identities in predetermined ways. For example, in Munday, Sajid, and Reader (Citation2014), art-based blogging enabled early childhood education students to develop their authentic selves as future teachers. One participant, Atia Sajid reported:

The process was very cathartic and it helped me understand myself, and most importantly, my teaching philosophy. (…) If we suppress the voice inside us, it stifles us but if we set ourselves free through art then we can understand other people better and perhaps become better professionals. (Munday, Sajid, and Reader Citation2014, 29)

Many studies noted that promoting students’ agency through assessment is a risky task. For example, students used their increased agency to show resistance to prevalent discourses and practices of assessment (Sutton and Gill Citation2010). In Liao et al. (Citation2023), one participant resisted ‘being viewed as a box-ticker’ in the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) assessment in physician education. Instead, the student ‘construct[ed] her identity as a comprehensive professional whose aim is ultimately to help her patients’ (1110). The authors note that there is a tension between assessment and self-formation:

Within this narrative there is a definite mismatch between assessor and trainee: the assessor's agenda being constructed as getting through the OSCE checklist in a perfunctory manner, and the trainee's agenda being asserted as striving for the bigger picture of becoming a physician. (Liao et al. Citation2023, 1110)

Towards a research agenda on understanding student identity formation in assessment

I have conducted an integrative review of empirical literature concerning student identity formation in assessment and the questions of power and ethics within. This review has theorised how assessment shapes student identities through five social technologies: (1) gatekeeping, (2) legitimisation, (3) concretisation, (4) socialisation and (5) individualisation (). Assessment may also provide the means for students to shape their own identities agentically. The key contribution of this review is to produce a metatheory based on this emerging literature and propose a research agenda on further understanding how assessment shapes students in higher education. I wish to bring assessment to the centre of higher education research that focuses on student being and becoming (Brooks and O’Shea Citation2021; Dall’Alba and Barnacle Citation2007; Marginson Citation2023).

Conceptual and methodological remarks

The studies were summarised by using the categorisation system by Radovic et al. (Citation2018). This summary can guide future research on assessment and student identities as it addresses both the conceptual and methodological issues and their intersections. Future studies may refer to this categorisation () as they conceptualise and operationalise the idea of ‘identity’ in assessment research.

This summary revealed some ‘thick’ areas of research. It seems most research has addressed identities retrospectively, focusing on the subjective aspects of identity (). Naturalistic case studies and rather simplistic and traditional research methods characterise this dataset. To move further, future research may focus more on the enacted aspects of identity in situ, given that this review only identified two such studies. For example, how do students construct their identities in authentic assessment – or perhaps in examinations or self-assessment tasks? Such studies may utilise observational or ethnographic approaches. Ethnographies may be particularly powerful in unpacking how students construct their professional identities in assessment situations. Surprisingly, given that assessment research is often dominated by psychometric knowledge, only two studies were found to use quantitative measurements of identity. This is another potential avenue for future research, particularly regarding the potential of carefully planned interventions for professional identity development. Future narrative studies may particularly want to focus on marginalised identities and how they unfold in students’ assessment-related narratives. This is particularly important given that assessment provides information about abilities – and thus disabilities – and students then use this information to construct their identities. Future research could unpack how marginalised identities may be further marginalised through assessment and how assessment may reframe these identities as strengths through its legitimation function (see Nieminen, Moriña, and Biagiotti Citation2024).

Future studies could enhance the existing evidence base on how assessment ‘other-forms’ students; understanding these processes means that future developmental work can also better address them. Each of the five technologies of ‘other-formation’ provides a lens for understanding how assessment changes students as social agents. Research may also wish to focus on providing inspiring case studies of how assessment could provide the means for ‘self-formation’ in various disciplinary contexts.

One interesting avenue for future research is considering the varying influences of different assessment practices on student identities. One could hypothesise that multiple choice question (MCQ) examinations and e-portfolios provide differing affordances for student identities to develop, and indeed the framework constituted in this study could help unpack these potential differences (see ). However, the very same practice – say, an MCQ examination – may have disparate consequences in different social, cultural, disciplinary, historical and political contexts (as seen in the findings of this study regarding, for example, e-portfolios). In one context, MCQs may promote neoliberal individualisation and competition; in another, they may socialise students to the values of diligence and grit and legitimise students’ powerful knowledge. Moreover, such ontological mechanisms may very well occur simultaneously. Any assessment practice may thus act as ‘a living portal’ whereby identity is ‘reimagined’, as Nguyen (Citation2013, 144) phrased it. Unpacking the relationship between assessment design and student identity formation warrants further investigation in future research.

Methodologically, future studies may draw on richer and more multimodal datasets concerning student identities. Interviews themselves provide rather limited information about students’ identities: it may be beneficial to supplement interview data with, for example, documents, life histories, assessment data, and diary data. There is a particular need for longitudinal designs to comprehensively unpack how assessment shapes student identities throughout higher education as well as in the transition phases.

Theory to practice

In the spirit of integrative reviews, I have provided new perspectives on the widely studied topic of assessment. Yet, as the mantra goes, nothing is more practical than a good theory. I wish this theorisation might guide not just future research, but future practice, too.

Indeed, the question of how assessment shapes student identities is a practical one. This review has shown that assessment has concrete, real consequences for student identities. The first implication for practitioners, then, is to become aware of these often unintended consequences. This is as much of an ethical quest as it is a practical one. The framework provided in this study may guide teachers, counsellors and curriculum designers to consider the potential influences of assessment on student identities and well-being (see ). For example, assessment designers might analyse the socialisation processes that a particular assessment practice promotes. Seemingly objective practices such as examinations may, in fact, instil the values of competition and individualisation into students’ understanding of themselves (e.g. Belluigi Citation2020; Lee and Fanguy Citation2022).

The framework may also guide future assessment design in providing students with more agency over their own identity formation. This may happen through two technologies (). First, students may be asked to reflect upon their own identity formation processes and thus become more aware of them. This could be done by implementing reflection tasks that ask students to critically investigate the role of assessment in their courses (e.g. Fu et al. Citation2022). Second, students may be provided reflexive agency over assessment. I note the particular power of student partnership in assessment design for this goal. This means that students are invited to share their views on assessment and contribute to the design of assessment, feedback and grading practices (see Chan and Chen Citation2023). Only by providing students with real agency over assessment design can they take a lead over their own identity formation in assessment.

One important line of future work is to showcase how student ‘other-formation’ and ‘self-formation’ could be harmonised (as discussed in Mayes Citation2010; see also Marginson Citation2023 and Nieminen and Yang Citation2023). How could assessment form students in desirable ways and provide them agency over their own formation? Pragmatic case studies on this front would be helpful for both research and practice.

Final words

This integrative review has synthesised higher education research to understand how assessment shapes student identities, emphasising assessment as a matter of identity formation – and not just learning. This study proposes a research agenda to better understand the ontological dimensions of assessment. Such research would help us understand the intended and unintended ways assessment shapes students in the ‘measured university’, driven by metrics, rankings and grades.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The search on Scopus was restricted to “psychology” and “social sciences”, and the search on Web of Science was restricted to studies published in journals indexed with the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI).

References

- The studies in the review are marked with an asterisk (*).

- *Alizadeh, M., A. Mirzazadeh, D. X. Parmelee, E. Peyton, N. Mehrdad, L. Janani, and H. Shahsavari. 2018. “Leadership Identity Development through Reflection and Feedback in Team-Based Learning Medical Student Teams.” Teaching and Learning in Medicine 30 (1): 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2017.1331134.

- *Andrew, M. 2012. ““Like a Newborn Baby”: Using Journals to Record Changing Identities Beyond the Classroom.” TESL Canada Journal 29 (1): 57–76. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v29i1.1089.

- *Barrow, M. 2006. “Assessment and Student Transformation: Linking Character and Intellect.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (3): 357–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600680869.

- Bearman, M., P. Dawson, D. Boud, S. Bennett, M. Hall, and E. Molloy. 2016. “Support for Assessment Practice: Developing the Assessment Design Decisions Framework.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (5): 545–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1160217.

- *Belluigi, D. Z. 2020. “"It’s Just Such a Strange Tension": Discourses of Authenticity in the Creative Arts in Higher Education.” International Journal of Education Through Art 21 (5): 1.

- *Bennett, D., J. Rowley, P. Dunbar-Hall, M. Hitchcock, and D. Blom. 2016. “Electronic Portfolios and Learner Identity: An EPortfolio Case Study in Music and Writing.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 40 (1): 107–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.895306.

- Biesta, G. 2009. Good Education in an age of Measurement: On the Need to Reconnect with the Question of Purpose in Education.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 21 (1): 33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9.

- *Blaj-Ward, L., and J. Matic. 2021. “Navigating Assessed Coursework to Build and Validate Professional Identities: The Experiences of Fifteen International Students in the UK.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46 (2): 326–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1774505.

- Boud, D., P. Dawson, M. Bearman, S. Bennett, G. Joughin, and E. Molloy. 2018. “Reframing Assessment Research: Through a Practice Perspective.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (7): 1107–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1202913.

- Brooks, R., and S. O’Shea. 2021. Reimagining the Higher Education Student: Constructing and Contesting Identities. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Cabral, T. C., and R. R. Baldino. 2019. “The Credit System and the Summative Assessment Splitting Moment.” Educational Studies in Mathematics 102 (2): 275–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-019-09907-5.

- Chan, C. K. Y., and S. W. Chen. 2023. “Conceptualisation of Teaching Excellence: An Analysis of Teaching Excellence Schemes.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2271188.

- *Chapman, A. 2017. “Using the Assessment Process to Overcome Imposter Syndrome in Mature Students.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 41 (2): 112–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2015.1062851.

- Chávez, J., J. Fauré, and J. Barril Madrid. 2023. “The Role of Agency in the Construction and Development of Professional Identity.” Learning: Research and Practice 9 (1): 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2022.2134575.

- Coombs, A., and C. DeLuca. 2022. Mapping the Constellation of Assessment Discourses: A Scoping Review Study on Assessment Competence, Literacy, Capability, and Identity.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 34 (3): 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-022-09389-9.

- Cronin, M. A., and E. George. 2023. “The Why and How of the Integrative Review.” Organizational Research Methods 26 (1): 168–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428120935507.

- Dall’Alba, G., and R. Barnacle. 2007. “An Ontological Turn for Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (6): 679–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701685130.

- Danielsson, A. T., H. King, S. Godec, and A. S. Nyström. 2023. “The Identity Turn in Science Education Research: A Critical Review of Methodologies in a Consolidating Field.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 695–754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-022-10130-7.

- *Dantas-Whitney, M. 2002. “Critical Reflection in the Second Language Classroom Through Audiotaped Journals.” System 30 (4): 543–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(02)00046-5.

- *Doyle, A., M. C. Johnson, E. Donlon, E. McDonald, and P. J. Sexton. 2021. “The Role of the Teacher as Assessor: Developing Student Teacher's Assessment Identity.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 46 (12): 52–68. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2021v46n12.4.

- Ecclestone, K., and J. Pryor. 2003. “‘Learning Careers’ or ‘Assessment Careers’? The Impact of Assessment Systems on Learning.” British Educational Research Journal 29 (4): 471–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920301849.

- *Fu, H., T. Hopper, K. Sanford, and D. Monk. 2022. “Learning with Digital Portfolios: Teacher Candidates Forming an Assessment Identity.” Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 13 (1): 1.

- Giroux, H. A. 2009. “Beyond the Corporate Takeover of Higher Education: Rethinking Educational Theory, Pedagogy, and Policy.” In Re-Reading Education Policy. A Handbook Studying the Policy Agenda of the 21st Century, edited by M. Simons, M. Olssen, and M. A. Peters, 458–477. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- *Hein, N. P., and B. A. Miller. 2004. “¿Quién Soy? Finding My Place in History: Personalizing Learning through Faculty/Librarian Collaboration.” Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 3 (4): 307–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192704268121.

- *Houghton, S. A. 2013. “Making Intercultural Communicative Competence and Identity-Development Visible for Assessment Purposes in Foreign Language Education.” The Language Learning Journal 41 (3): 311–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.836348.

- *Impedovo, M. A., M. B. Ligorio, and K. F. McLay. 2018. “The “Friend of Zone of Proximal Development” Role: EPortfolios as Boundary Objects.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 34 (6): 753–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12282.

- Kasanen, K., and H. Räty. 2002. ““You be Sure Now to be Honest in Your Assessment”: Teaching and Learning Self-Assessment.” Social Psychology of Education 5 (4): 313–328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1020993427849.

- Kinchin, I. M., and K. Gravett. 2022. Dominant Discourses in Higher Education: Critical Perspectives, Cartographies and Practice. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- *Kjærgaard, A., E. N. Mikkelsen, and J. Buhl-Wiggers. 2023. “The Gradeless Paradox: Emancipatory Promises but Ambivalent Effects of Gradeless Learning in Business and Management Education.” Management Learning 54 (4): 556–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505076221101146.

- *Lee, K., and M. Fanguy. 2022. “Online Exam Proctoring Technologies: Educational Innovation or Deterioration?” British Journal of Educational Technology 53 (3): 475–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13182.

- *Li, F., and Y. Han. 2023. “Chinese International Students’ Identity (re)Construction Mediated by Teacher Feedback: Through the Lens of Academic Discourse Socialisation.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 61: 101211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101211.

- *Liao, K. C., R. Ajjawi, C. H. Peng, C. C. Jenq, and L. V. Monrouxe. 2023. “Striving to Thrive or Striving to Survive: Professional Identity Constructions of Medical Trainees in Clinical Assessment Activities.” Medical Education 57 (11): 1102–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.15152.

- Löfgren, R., H. Löfgren, and V. Lindberg. 2019. “Pupils’ Perceptions of Grades: A Narrative Analysis of Stories About Getting Graded for the First Time.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 26 (3): 259–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2019.1593104.

- *MacKay, J. R., K. Hughes, H. Marzetti, N. Lent, and S. M. Rhind. 2019. “Using National Student Survey (NSS) Qualitative Data and Social Identity Theory to Explore Students’ Experiences of Assessment and Feedback.” Higher Education Pedagogies 4 (1): 315–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2019.1601500.

- Marginson, S. 2023. “Student Self-Formation: An Emerging Paradigm in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2252826.

- *Mayes, P. 2010. “The Discursive Construction of Identity and Power in the Critical Classroom: Implications for Applied Critical Theories.” Discourse & Society 21 (2): 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926509353846.

- McAlpine, M. 2005. “E-portfolios and Digital Identity: Some Issues for Discussion.” E-Learning and Digital Media 2 (4): 378–87. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2005.2.4.378.

- *Munday, J., A. Sajid, and B. Reader. 2014. “Cultural Identity through Art(s)Making: Pre-Service Teachers Sharing Ideas and Experiences..” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 39 (7): 14–30. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n7.2.

- *Nguyen, C. F. 2013. “The EPortfolio as a Living Portal: A Medium for Student Learning, Identity, and Assessment.” International Journal of EPortfolio 3 (2): 135–48.

- Nieminen, J. H., and J. Lahdenperä. 2024. “Assessment and Epistemic (in)Justice: How Assessment Produces Knowledge and Knowers.” Teaching in Higher Education 300–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1973413.

- Nieminen, J. H., A. Moriña, and G. Biagiotti. 2024. “Assessment as a Matter of Inclusion: A Meta-Ethnographic Review of the Assessment Experiences of Students with Disabilities in Higher Education.” Educational Research Review 42: 100582.

- Nieminen, J. H., and L. Yang. 2023. “Assessment as a Matter of Being and Becoming: Theorising Student Formation in Assessment.” Studies in Higher Education 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2257740.

- *Nieminen, J. H., and H. V. Pesonen. 2020. “Taking Universal Design Back to its Roots: Perspectives on Accessibility and Identity in Undergraduate Mathematics.” Education Sciences 10 (1): 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10010012.

- Peseta, T., S. Barrie, and J. McLean. 2017. “Academic Life in the Measured University: Pleasures, Paradoxes and Politics.” Higher Education Research & Development 36 (3): 453–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1293909.

- Pryor, J., and B. Crossouard. 2008. “A Socio-Cultural Theorisation of Formative Assessment.” Oxford Review of Education 34 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980701476386.

- Pryor, J., and B. Crossouard. 2010. “Challenging Formative Assessment: Disciplinary Spaces and Identities.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (3): 265–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903512891.

- Radovic, D., L. Black, J. Williams, and C. E. Salas. 2018. “Towards Conceptual Coherence in the Research on Mathematics Learner Identity: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Educational Studies in Mathematics 99 (1): 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-018-9819-2.

- *Sidebotham, M., K. Baird, C. Walters, and J. Gamble. 2018. “Preparing Student Midwives for Professional Practice: Evaluation of a Student E-Portfolio Assessment Item.” Nurse Education in Practice 32:84–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.07.008.

- *Silva, M. L., S. Adams Delaney, J. Cochran, R. Jackson, and C. Olivares. 2015. “Institutional Assessment and the Integrative Core Curriculum: Involving Students in the Development of an EPortfolio System.” International Journal of EPortfolio 5 (2): 155–67.

- Simpson, A., and Y. Bouhafa. 2020. “Youths’ and Adults’ Identity in STEM: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal for STEM Education Research 3 (2): 167–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41979-020-00034-y.

- *Skyrme, G. 2007. “Entering the University: The Differentiated Experience of Two Chinese International Students in a New Zealand University.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (3): 357–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701346915.

- Stobart, G. 2016. ““Assessment and Learner Identity.”.” In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, edited by M. A. Peters, 56–60. Singapore: Springer.

- Sutton, P., and W. Gill. 2010. “Engaging Feedback: Meaning, Identity and Power.” Practitioner Research in Higher Education 4 (1): 3–13.

- Tomlinson, M., and D. Jackson. 2021. “Professional Identity Formation in Contemporary Higher Education Students.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (4): 885–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1659763.

- Torraco, R. J. 2005. “Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples.” Human Resource Development Review 4 (3): 356–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283.

- Torres, J.T., Zoe Higheagle Strong, and Olusola O. Adesope. 2020. “Reflection through Assessment: A Systematic Narrative Review of Teacher Feedback and Student Self-Perception.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 64: 100814. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.100814.

- *Torres, J. T., and C. J. Anguiano. 2016. “Interpreting Feedback: A Discourse Analysis of Teacher Feedback and Student Identity.” Practitioner Research in Higher Education 10 (2): 2–11.

- *Torres, J. T., and N. Ferry. 2019. “I Am Who You Say I Am: The Impact of Instructor Feedback on Pre-Service Teacher Identity.” Practitioner Research in Higher Education 12 (1): 3–14.

- Trede, F., R. Macklin, and D. Bridges. 2012. “Professional Identity Development: A Review of the Higher Education Literature.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (3): 365–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.521237.

- Whittemore, R., and K. Knafl. 2005. “The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 52 (5): 546–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x.

- *Wiewiora, A., and A. Kowalkiewicz. 2019. “The Role of Authentic Assessment in Developing Authentic Leadership Identity and Competencies.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44 (3): 415–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1516730.

- Wiliam, D., H. Bartholomew, and D. Reay. 2004. “Assessment, Learning, and Identity.” In Researching the Socio-Political Dimensions of Mathematics Education: Issues of Power in Theory and Methodology, edited by P. Valero and R. Zevenbergen, 43–61. Norwell, MA: Kluwer.

- Wohlin, C., M. Kalinowski, K. R. Felizardo, and E. Mendes. 2022. “Successful Combination of Database Search and Snowballing for Identification of Primary Studies in Systematic Literature Studies.” Information and Software Technology 147:106908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2022.106908.

- *Wright, V., T. Loughlin, and V. Hall. 2017. “Lesson Observation and Feedback in Relation to the Developing Identity of Student Teachers.” Teacher Education Advancement Network Journal 9 (1): 100–12.

- *Zheng, C., and G. Chai. 2019. “Learning as Changing Participation: Identity Investment in the Discursive Practice of a Peer Feedback Activity.” Power and Education 11 (2): 221–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757743819833075.

- *Zheng, C., and X. Huang. 2017. “Learning as Changing Identity Investment in Social Practice, Discourse Analysis of a Peer Feedback Activity.” Advances in Applied Sociology 07 (02): 64. https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2017.72004.

- Zwick, R., and N. J. Dorans. 2016. “Philosophical Perspectives on Fairness in Educational Assessment.” In Fairness in Educational Assessment and Measurement, edited by N. J. Dorans and L. L. Cook, 267–81. New York, NY: Routledge.