ABSTRACT

Over the past twenty years, higher education institutions (HEIs) including universities, polytechnics, and vocational education providers, have become major conduits for the teaching and dissemination of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). The Times Higher Education Impact rankings, other rankings schemes and external accreditation requirements also pressure HEIs to report their progress towards the SDGs periodically. For large HEIs, reporting requirements can equate to significant resource burdens, and these can be insurmountable. In this paper, we develop a novel approach to measuring SDG content in the course descriptions and learning outcomes of 5461 courses offered by a major Australian university. Our method utilises semantic matching, an AI-based technique that assesses similarities between key terms in the dataset (including course descriptions and course learning outcomes) and those in each SDG. Our results achieve a 75% fit to the data and show that Quality Education (SDG 4) and Partnerships for the Goals (SDG 17) are the most common SDGs covered at the case university and that these reflect course learning outcomes that focus on pedagogy. Where SDGs are more domain-specific, there is a much less consistent coverage across the university, and this is observable at the Faculty and School levels. This highlights that it is not possible or desirable to cover all SDG content in all educational offerings consistently. Our algorithm is a potential solution for larger HEIs that seek to capture and report the SDG contributions of their education offerings holistically using existing textual datasets, without the need for excessive resource investments.

Introduction

The advent of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has had a profound effect on higher education institutions (HEIs). Many authors view HEIs, particularly universities, as important advocates for the SDGs (Miller, Cunningham, and Lehmann Citation2021; Schiff et al. Citation2024). This has led towards a drive to include SDG-related content in education offerings. Most HEIs do this through curriculum design (Cardiff, Polczynska, and Brown Citation2024; Chou and Wang Citation2024; Day et al. Citation2024). Educators have also included SDG content as part of their teaching (Cardiff, Polczynska, and Brown Citation2024; Chou and Wang Citation2024; Dziubaniuk et al. Citation2024; Grano and Prieto Citation2020; Manolis and Manoli Citation2021) while also acknowledging a need to accommodate greater diversity through pedagogical approaches (Manolis and Manoli Citation2021; Opoku Citation2024; Shephard et al. Citation2015; von Knorring et al. Citation2024). Incorporating SDGs into HEI practices has, however, led to a need for adaptation at the organisation level.

HEIs have had to change many of the systems and processes they use in their operations to accommodate sustainability-related concerns (Bayhantopcu and Ojea Citation2023; Leal Filho et al. Citation2020; Smith and Heyward Citation2024). For example, sustainability reporting gives rise to new systems, new organisational units, and new activities. Accordingly, HEIs have had to make additional resource investments (Fakir Mohammad, Hinduja, and Siddiqui Citation2024). There has been a need to re-design HEI missions and to shift organisational culture to accommodate SDG implementation (Bayhantopcu and Ojea Citation2023; Dziubaniuk et al. Citation2024; Weber et al. Citation2021). The impetus for change is acute. There is growing pressure on HEIs to adopt sustainable practices and to demonstrate their SDG progress to a range of external stakeholders (Bayhantopcu and Ojea Citation2023; Jones Citation2017).

Many HEIs rely on their own subjective interpretations of SDGs and use manual approaches to collate, analyse and report on their sustainability performance (Dziubaniuk et al. Citation2024; Gutiérrez-Mijares et al. Citation2023). However, where HEIs rely on subjective interpretation to assess their own SDG performance, this has the potential to lead to systematic bias. This means there is a lower likelihood that reporting information is an accurate record of sustainability outcomes (Findler et al. Citation2019; Gutiérrez-Mijares et al. Citation2023). Human error, self-interest, and ‘game-playing’ can often corrupt data collation, analysis and reporting, and resource constraints also place pressures on HEI personnel to produce outputs quickly. This is exacerbated through the manual approaches used by HEI personnel in these activities (Dziubaniuk et al. Citation2024; Findler et al. Citation2019; Tierney, Tweddell, and Willmore Citation2015). The question remains as to how HEIs can report their sustainability outcomes quickly, accurately and comprehensively without encountering the issues that the current, subjective and manual approaches involve (Gutiérrez-Mijares et al. Citation2023).

The purpose of the present study is to develop a method that overcomes the challenges that HEIs face when reporting SDG-related outcomes. Accordingly, we propose a new method for the collation, analysis, and reporting of HEI SDG-related content using semantic matching, an AI-based approach to compare key terms from multiple text-based datasets to determine their similarity (Chandrasekaran and Mago Citation2022; Chang et al. Citation2008; Harispe et al. Citation2015). We draw on a database of 5461 course outlines (specifically, course descriptions (CDs) and course learning outcomes (CLOs)) available in a database held by a major Australian university and two sources of SDG key terms to develop and validate the semantic match algorithm. The algorithm assigns tags to course outline data to flag SDG-related content mentions, if any, based on the similarity between key terms in the course outline and the SDGs.

This study contributes to the higher education (HE) literature by developing a new approach to measuring SDG content in educational offerings at the institutional level. Several authors highlight HEI attempts to measure SDG content in their curriculum, course content, and pedagogy (Geng and Zhao Citation2020; Griebeler et al. Citation2022; Leal Filho et al. Citation2020; Rosen Citation2020; Roszkowska and Filipowicz-Chomko Citation2020; Serafini et al. Citation2022). However, each one relies on the subjective, manual approaches we criticise above. Whether the outputs of these processes are trustworthy is questionable. Moreover, collating, analysing and reporting this information involves significant manual labour. The semantic match algorithm we develop in this paper has the potential to address these issues.

The study also contributes to the debate regarding HEI sustainability performance (Geng and Zhao Citation2020; Griebeler et al. Citation2022; Khare and Stewart Citation2024; Leal Filho, Salvia, and Eustachio Citation2023; Rosen Citation2020; Serafini et al. Citation2022). Our results show that Quality Education (SDG 4) and Partnerships for the Goals (SDG 17) are the most common SDGs covered at the case university. HEIs are more likely to achieve SDGs by simply offering good education products in this case. The results also show considerable dispersion in terms of domain-specific SDG outcomes since they are not applicable to all education offerings. HEIs can achieve some SDG outputs due to their business-as-usual activities, but whether this is the intention behind the SDGs is questionable. For domain-specific SDG coverage, there is a need to develop course content to focus on a specific SDG area of interest. This may be a more direct way to advocate for specific SDGs. This observation challenges an underlying assertion by some authors, that HEIs should advocate all SDGs simultaneously (Leal Filho et al. Citation2020; Sánchez-Carracedo et al. Citation2021; Serafini et al. Citation2022; Smith and Heyward Citation2024; Tierney, Tweddell, and Willmore Citation2015).

Literature review

The SDGs and HEI legitimacy

There is widespread agreement that universities and other HEIs have a key role in promoting the SDGs (Blasco, Brusca, and Labrador Citation2021; Kioupi and Voulvoulis Citation2020; Miller, Cunningham, and Lehmann Citation2021; Rosen Citation2020; Sánchez-Carracedo et al. Citation2019; Schiff et al. Citation2024). While external accreditation requirements and rankings schemes motivate HEIs to adopt and advocate the SDGs, other drivers such as public profile building, student attraction, research income sourcing and philanthropy generation are also important (Blasco, Brusca, and Labrador Citation2021). HEIs, in many cases, have little choice but to demonstrate their adherence to, and promotion of, the SDGs. Many such institutions now have sustainability strategies or plans which communicate a commitment to the SDGs through operations, investments, educational initiatives, and/ or research. Yet, this is only part of a bigger mix. Indeed, HEIs also use advertising, public relations, websites, and other sources to communicate their commitment to the SDGs.

It is important to substantiate the claims that HEIs make with respect to the SDGs, and organisations that make claims towards the sustainability of their activities, their inputs and their outputs, require evidential support (Feng, Lai, and Zhu Citation2020; Thomas and Lamm Citation2012). Without such evidence, the organisation risks jeopardising its reputation and sacrifices the value it might otherwise create (Maurer, Bansal, and Crossan Citation2011). As such, the organisation seeks to establish its legitimacy. Suchman (Citation1995) defines organisational legitimacy as ‘a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions’ (574). The organisation’s attributes and its behaviours must consequently align with a set of standards that reflect social values (Schaltegger and Hörisch Citation2017; Thomas and Lamm Citation2012).

SDGs are representations of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions which derive from a socially constructed process. The United Nations is the custodian of the SDGs, particularly through its Division for Sustainable Development Goals (www.sdgs.un.org/about). The SDGs were introduced at the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro in 2012 as a replacement for the Millennium Development Goals. The SDGs were published as a final draft in July 2014. The SDGs derive from of an open working group and three-year participatory process involving 88 national consultations, six dialogues and door-to-door surveys with multiple stakeholders (https://www.undp.org/sdg-accelerator/background-goals). There are 17 SDGs, which advocate for causes like poverty and hunger reduction, health and wellbeing, education, sanitation as well as a variety of other causes. The SDGs are a comprehensive framework and, as such, are broader than economic, environmental and social interpretations of sustainability that many HEIs currently use (Gutiérrez-Mijares et al. Citation2023). While HEIs are not officially required to adhere or advocate the SDGs, doing so has now become common practice across the sector, particularly through public-facing media (websites, advertising, public relations) and through classroom content (Antó et al. Citation2021; Sánchez-Carracedo et al. Citation2019; Serafini et al. Citation2022).

HEIs must be able to achieve three components of organisational legitimacy – pragmatic, moral and cognitive (Suchman Citation1995; Thomas and Lamm Citation2012). Pragmatic legitimacy refers to the organisation’s perceived ability to deliver practical benefits. HEIs that invest more heavily in SDG-related causes are more likely to deliver on SDG-related outcomes, for example (Miller, Cunningham, and Lehmann Citation2021). Moral legitimacy is the extent to which the organisation’s actions and attributes adhere to relevant social norms and moral obligations. There is variance in terms of the pursuit of SDGs, as is evident in the Times Higher Education Impact rankings and one explanation for this is that HEIs differ in terms of the moral codes they adhere to, with this reflected in the SDGs to which they contribute primarily. Cognitive legitimacy refers to the perceived comprehensibility of an action or policy in terms of the extent to which it is congruent with established narratives or expectations that individuals have regarding the organisation. For HEIs, this requires clear explanations of their SDG-pursuing activities, an issue which is difficult to address (Roszkowska and Filipowicz-Chomko Citation2020; Serafini et al. Citation2022; Shephard et al. Citation2015). For each type of legitimacy, validation through evidence is important to communicate to stakeholders that the HEI takes the pursuit of SDGs seriously (Thomas and Lamm Citation2012).

Methods to demonstrate SDG commitment

The broad range of SDGs has led to varying implications across industries. For example, manufacturing industries tend to focus on materials use (including waste) in production activities, distribution, and related effects such as carbon emissions when assessing their impacts on SDGs (Arora, Wei, and Solak Citation2021; Loosemore, Zaid Alkilani, and Murphy Citation2021; Montalbán-Domingo et al. Citation2019). Service-based industries focus on the SDG impacts of service delivery. In healthcare, for example, SDG outcomes are measurable in terms of instances of morbidities and mortalities (Global SDG Collaborators Citation2018). HEIs face an interesting situation when considering their commitment to the SDGs (Leal Filho, Salvia, and Eustachio Citation2023; Serafini et al. Citation2022). First, there is a need to ensure that inward-facing operational activities contribute to SDGs. This includes the administrative and support activities which facilitate other activities. Second, HEIs can also pursue the SDGs through outward-facing activities such as education delivery and research outputs.

While organisations use a variety of approaches to pursue SDG-related outcomes, demonstrating their commitment to the SDGs is a different consideration. The evidence that organisations are achieving SDG targets can emerge through third-party sources such as government bodies and industry bodies. In this case, there is a reliance on actors separate to the organisation to obtain, analyse, and present data in an acceptable format. This is easier to do when there are established objective statistics such as population census data, weather/ climate data, financial data, and healthcare data. The common feature of this data is that it is quantifiable and from an objective source. Many SDGs use qualitative language and are therefore more difficult to capture and to analyse meaningfully.

Many HEIs must, by law, present reports of their activities. This can be to align with accepted codes of conduct, to adhere to legal and financial reporting obligations, and/ or to maintain accreditations. As such, HEIs must uncover the relevant evidence and submit it in an acceptable format. To do this, there is often a need for the manual collation and cleaning of data as well as its analysis and reporting. This gives rise to potential incomplete or inaccurate data, with subsequent analyses then relying on this dataset, which amplifies the impacts of poor data. Manual data collection, analysis and reporting are often labour-intensive and can lead to bias (including selective disclosure and incomplete reporting) (Abhayawansa Citation2022; Chagas et al. Citation2022). The current evidence suggests it is likely that HEIs face problems such as these in reporting on their SDG commitments (Adomßent et al. Citation2014; Finsterwalder and Kuppelwieser Citation2020; Geng and Zhao Citation2020).

Most HEIs do not have a means to efficiently capture SDG-related evidence at scale and to report it (Gutiérrez-Mijares et al. Citation2023). This is despite large available datasets containing crucial information. Many HEIs rely on the manual reporting approach we outline here and, accordingly, are susceptible to the issues that this raises. We suggest that finding ways to automate SDG reporting is a crucial step towards improving efficiency while also increasing the likelihood that HEIs have visibility of the SDG outcomes that they produce. This is essential to increasing HEI engagement in SDGs, an area where there are currently substantial opportunities for improvement (Findler et al. Citation2019; Leal Filho et al. Citation2020; Leal Filho, Salvia, and Eustachio Citation2023).

Methodology

Our goal in this study is to develop a method that allows HEIs to capture, analyse and report on the SDG content in their educational offerings. Our approach is most useful where large-scale, diverse data are available and, where the need to invest in dedicated resources for analysis and reporting is significant. Therefore, we base our study at a major Australian university with more than 50,000 students enrolled across its education programmes. The university has seven major faculties and 161 Schools, a main campus located in a state capital city and a range of other campuses and facilities throughout the state. The university offers a broad range of programmes, spanning arts, humanities, law, business, medicine, science, and engineering. Each educational offering by the university varies in its SDG-related content. While there is wide interest in the SDGs, the university, at the time of writing, was still in the process of developing a robust approach to capturing and reporting SDG content across its educational offerings. Given its characteristics, we felt this was an ideal setting for our study.

We were able to access a database of the CDs and CLOs for all 5461 undergraduate and postgraduate coursework (i.e. non-thesis or dissertation-based) courses on offer by the university, so this is a census of the population under consideration. This database is held centrally as part of the university’s data lake and is crucial to the administration of the university’s course offerings. Accessing this dataset contributes to the robustness of our algorithm since it covers a vast array of educational offerings across many academic disciplines from across the university. The findings also are relevant to other comparable institutions due to their breadth and diversity.

CDs are paragraphs with between three and five sentences that articulate the purpose of the course, how it fits into a broader programme structure and its main contents. CLOs are normally a list of single sentences that state the learning objectives that a student will achieve by completing the course. One course usually has one CD and between three and six CLOs. presents a random example of the CD and the CLOs of a course in the database. The database contains records for 5461 courses on offer by the university, with 5461 CDs and 38,647 CLOs in total. When we accessed this database, we began the analysis by removing errors, empty values, and duplicates manually. Out of the 38,647 CLOs in the initial database, 33,343 were successfully mapped to the available CDs. The average number of words in the CD text was 121.27 and for the CLO text, it was 16.63. presents a summary of this dataset.

Table 1. A sample course description (CD) and course learning outcomes (CLOs) for an example course.

Table 2. A summary of statistics for the CDs and CLOs in the dataset.

Our semantic match approach requires a comparison between the text in the CDs and CLOs with keywords related to the SDGs. A close examination of the SDGs reveals the potential for several interpretations of keywords. To overcome this issue, we combined two recognised keyword sources to represent the 17 SDGs. The first source was prepared by Monash University and the Sustainable Development Institute (https://www.monash.edu/msdi/initiatives/sdsn). It includes 915 keywords to describe the 17 SDGs. The second source is available from the University of New South Wales. This source also includes a comprehensive list of keywords to describe the 17 SDGs. We include our consolidated list as a web appendix (see web appendices). We manually compared the terms in each list to eliminate duplicates and to consolidate some key terms where there was a very close match. This process resulted in a single file of all SDG key terms, which we then used as an input for the subsequent analyses.

Semantic matching

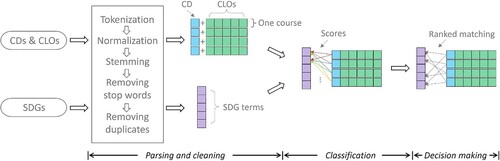

Semantic matching is the assessment of the extent to which two words have the same meaning to determine their similarity. We used semantic matching to appraise the similarity between two text-based pieces of data from two different sources (Chandrasekaran and Mago Citation2022). As we outline above, these sources were the database of CDs and CLOs, and the consolidated list of SDG keywords. The semantic similarity assessment process considers the meaning and context of the text, as opposed to simply comparing text strings. This allows for a deep understanding of the content and accounts for similarities even when the text differs superficially (Chandrasekaran and Mago Citation20221). The advantages of semantic similarity for text matching have been verified in many studies in terms of reliability, accuracy, adaptability, and generalisation (Chandrasekaran and Mago Citation2022; Harispe et al. Citation2015; Zhang, Saberi, and Chang Citation2017). illustrates the overall process of matching SDG terms with the courses (CD and CLOs) we use in this study and involves three steps.

Figure 1. The process of matching SDG content with course descriptions (CDs) and course learning outcomes (CLOs).

Stage 1. Text parsing and data cleaning

In this stage, the algorithm reads input data from the two spreadsheets and merges them into a single data object. The input data consists of CDs and CLOs from spreadsheet 1, and the consolidated SDG keyword list from spreadsheet 2. We merged the CD and CLO text into one paragraph to represent the course and to match with the SDG keywords. The texts of the merged paragraphs are tokenised, stemmed, and normalised, and then the stop words, special characters, and punctuations are removed. This process is to reduce data noise and redundant input, which helps improve machine learning accuracy and efficiency in the next stage. In addition, the SDG keyword lists provide multiple keywords under each of the 17 SDG categories, therefore the SDGs are considered labels of the keywords under them.

Step 2. Classification

In this stage, the algorithm iterates over all the paragraphs merged from CDs and CLOs and assigns a confidence score to the degree of match between and the paragraphs and the SDG keywords based on their semantic similarity. We use a pre-trained model of Zero-Shot Learning (Chang et al. Citation2008) for this purpose. This model takes a paragraph of text (CDs and CLOs) and a candidate keyword (SDG keywords) as input and outputs a confidence score which indicates how well the keyword describes the paragraph. After this step, we used the same process to assign multiple confidence scores for each course-related paragraph (which combines CD and CLO text) to match with every SDG keyword based on semantic similarity.

Step 3. Decision making

In this stage, the algorithm makes the final decision on which SDGs are assigned to each course. The algorithm produces confidence scores. Where these scores are above 20%, the algorithm takes a mean score of matches between the CD/ CLO text and the SDG keyword text and flags a potential match. To confirm the match, the mean score of confidence intervals must exceed a pre-determined threshold. To establish the threshold, we manually matched a sample of 200 course paragraphs (incorporating the CDs and CLOs) to the SDG keywords and evaluated the classification results using different thresholds ranging from 0.01 to 0.99. The best classification performance (accuracy: 0.80, recall: 0.54, and F1 score: 0.46) was achieved when the threshold is set at 0.75. Hence, we used this as a basis to claim that a match exists, which suggests that our algorithm has an accuracy of about 75%.

We have included the Python code for our algorithm in the web appendices.

Results

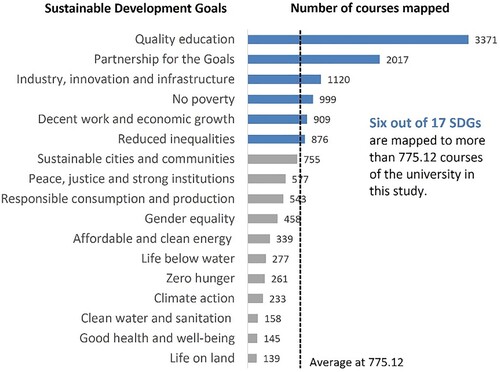

The results are extensive since they cover the 5461 CDs and 33,343 CLOs mapped. To enhance the user-friendliness of these outputs, we present a series of charts that capture the main insights. maps the overall contribution of the university’s courses towards each SDG. We see that the university performs best in Quality Education (SDG 4), followed by Partnerships for the Goals (SDG 17), and least in terms of Life on Land (SDG 15). Overall, an average of 775.12 courses of this university maps to the SDGs, and six out of 17 SDGs map to more than this number in this university.

These results are interesting in that they reflect the pedagogical emphasis of many of the CLOs. CLOs often focus on specific skills sets such as ‘critical thinking’, ‘problem solving’, ‘communication skills’, and ‘presentation skills’. Hence, this university’s educational offerings are principally concerned with SDG 4, with 3371 of the 5461 courses assessed contributing to this outcome. Partnership for the Goals (SDG 17) is the next most prolific SDG in the course data. This is again a reflection of the pedagogical emphasis of these courses, with 2017 advocating skills such as ‘collaboration’, ‘teamwork’, and ‘coordination’. If we consider the next four most common SDGs in the courses data, there is more evidence of domain-specific applications. ‘Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure (SDG 9, covered in 1120 courses), No Poverty (SDG 1, covered in 999 courses), Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8, covered in 909 courses), and Reduced Inequalities (SDG 10, covered in 876 courses), all involve the development of skills or knowledge that can contribute more directly to the specified outcomes in each SDG.

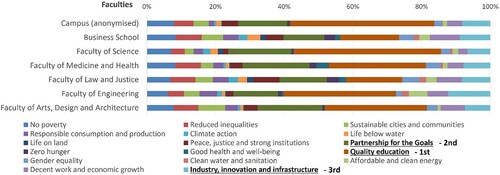

presents a breakdown of SDG matches per course by Faculty, which is useful when trying to understand which parts of the university contribute most/ least to each SDG. This analysis again highlights the difference between the pedagogical nature of some SDGs as opposed to the domain-specific content of others. While each Faculty contributes to Good Education, the Faculty of Science and the Faculty of Engineering both contribute more to Clean Water and Sanitation than the Business School or the Faculty of Law and Justice, for example. Meanwhile the Faculty of Law and Justice contributes more to Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions than all other faculties. The Faculty of Medicine and Health contributes more to Good Health and Well-being than other faculties.

If we look at the School level, a more granular perspective emerges. While we can make many School-by-School comparisons, we’ve chosen two examples to focus on in . We randomly selected two SDGs, namely Gender Equality, and Decent Work and Economic Growth, and compared the top ten schools based on the number of courses that match the two SDGs. Gender Equality, and Decent Work and Economic Growth are treated as domain-specific topics in most cases, so this explains the results of this observation. The School of Law, Society and Criminology (with 56 courses), and the School of Education (with 47 courses) are the top two Schools when it comes to Gender Equality. The School of Population Health (with 21 courses) and the Business School (with 12 courses) rank seventh and tenth respectively. When it comes to Decent Work and Economic Growth, the School of Education (with 68 courses), and the School of Accounting, Auditing and Taxation (with 61 courses) rank first and second, while the School of Banking and Finance (with 49 courses), the School of the Arts and Media (with 31 courses), and the School of Economics (with 29 courses) rank as fourth, ninth and tenth.

Figure 4. Comparison between two SDGs in the top 10 schools with the largest number of matching courses.

To further illustrate the findings, we present an example of a School-level assessment of SDG content in the CDs/ CLOs across seven courses offered by the School of Business (see ). This sort of information is useful for a Department Chair or Head of School when assessing the SDG content in the courses on offer by their School. This may assist when planning for accreditation activities or for the management of SDG content at the course or programme levels.

Table 3. A snapshot of results from business school courses.

Discussion

Gutiérrez-Mijares et al. (Citation2023), after their extensive review of sustainability assessment in the HE sector globally lament the ‘ … lack of a comprehensive single method designed for assessing the three pillars of sustainability’ (1152). In this study, we introduce a semantic match approach to appraising SDG content in a sample of 5461 courses on offer at a major Australian university. Our approach is inclusive in that it covers all course offerings at the university in question (with some exceptions based on data availability and integrity). It also addresses all 17 SDGs, which is much broader than any existing approach and has a wider scope than economic, social, and environmental sustainability. This addresses another one of Gutiérrez-Mijares et al. (Citation2023) concerns, that there is a need to develop an extensive set of measures to capture sustainability content.

Our new algorithm presents an objective way of interpreting SDG content in education offerings. We use a range of key terms (see the web appendices) that amount to a broad set of interpretations of the SDGs. This means there is less reliance on subjective interpretation. Indeed, current approaches used by HEIs rely on the subjective interpretation of sustainability and of sustainability-related dimensions (Antó et al. Citation2021; Crespo et al. Citation2017; Gutiérrez-Mijares et al. Citation2023; Kioupi and Voulvoulis Citation2020; Nagy, Benedek, and Ivan Citation2018; Sánchez-Carracedo et al. Citation2019). Common ways to assess sustainability-related content involve interpretation of qualitative data from a range of documentation or on interviews/ surveys of a variety of respondent types, including students, teachers, and administrators (Gutiérrez-Mijares et al. Citation2023; Sánchez-Carracedo et al. Citation2019).

While we acknowledge that our algorithm achieves 75% accuracy in its current form, semantic matching algorithms improve over time with use since they draw on machine learning. The more use and calibration the algorithm has, the more accurate the results. This means that our new approach also contributes to overcoming a key problem identified in the literature – the lack of a universal approach to assessing SDGs (Roszkowska and Filipowicz-Chomko Citation2020; Sánchez-Carracedo et al. Citation2021; Tierney, Tweddell, and Willmore Citation2015; von Knorring et al. Citation2024). We show that there is no need for such a universal framework since semantic matching is usable to establish SDG contributions from unstructured, textual data, and to do so objectively.

The results of our new algorithm show that Quality Education (SDG 4) and Partnerships for the Goals (SDG 17) are the most common SDGs covered at the case university. HEIs are more likely to achieve SDGs by simply offering good education products in this case. The results also show considerable dispersion in terms of domain-specific SDG outcomes since they are not applicable to all education offerings. Hence, we contribute to the debate regarding HEI sustainability performance (Geng and Zhao Citation2020; Griebeler et al. Citation2022; Khare and Stewart Citation2024; Leal Filho, Salvia, and Eustachio Citation2023; Rosen Citation2020; Serafini et al. Citation2022). The inherent heterogeneity of SDG contributions across courses suggests that it is not possible or desirable to convey all SDG content in all courses. In terms of planning, the implication here is that HEIs can acknowledge this situation, rather than try to cover all SDGs simultaneously, as some sources suggest is advantageous (Leal Filho et al. Citation2020; Sánchez-Carracedo et al. Citation2021; Serafini et al. Citation2022; Smith and Heyward Citation2024; Tierney, Tweddell, and Willmore Citation2015). Some reporting bodies incentivise wider coverage of SDG content in courses, so HEIs submitting to these schemes are likely to struggle. Other reporting bodies allow for selective reporting, which might boost outcomes, but might also disincentivise attempts to cover multiple SDGs and instead to specialise on only a few. Our study suggests that this resembles a tension between different SDGs and HEIs attempts to reconcile their efforts to address them.

Our findings also show that the language contained in several SDGs (and their associated measures or performance indicators) may not reflect the initial intent behind the SDGs. Quality Education (SDG 4), for example, uses very broad terminology. This is one explanation for the outcomes we recorded with our algorithm. The closest keywords in the CDs and CLOs related to elements of pedagogy. While it may be that the United Nations intends to motivate a wide variety of education offerings, a key implication from the present study is that HEIs can account for SDG 4 in their normal activities and without any intention to provide their education offerings to disadvantaged groups. This may be disingenuous. For those SDGs that are more domain-specific, the link between United Nation’s intent and the outcomes that manifest through HEI offerings may align more closely.

Using our algorithm has the potential to improve the efficiency of collating, analysing, and reporting sustainability-related outcomes for HEIs. While access to a database of CDs and CLOs is a necessary pre-condition, many HEIs now have such datasets. As we saw, there is a need to account for data-related issues prior to the analysis. This includes addressing missing data, duplicates, and other errors. As such, it is necessary to clean datasets prior to use. The algorithm does take some computing power to generate results at present. Each iteration took about two-days to run from start to finish. However, this is an improvement over current approaches which, for large datasets, can take many months due to the need for manual data collection, analysis, and reporting. With improvements in computing power, algorithm efficiency, and algorithm accuracy, there is scope to reduce the time necessary to run the algorithm as well as improve its accuracy.

Our new algorithm has several implications for HEIs. The process we describe in this study is useful as a means for HEIs to demonstrate that they contribute to the SDGs. There has been an ongoing debate as to the role of HE and SDG advocacy (Grano and Prieto Citation2020). We envisage the reporting functions that we demonstrate here as parts of HEI submissions to global rankings schemes and to accreditation bodies (Jones Citation2017). Given the benefits we describe above, this means that HEIs could experience greater reporting efficiency and effectiveness in their sustainability reporting by using our algorithm. We also see this in terms of resource conservation. Using our algorithm has the potential to reduce the need to recruit personnel or to redirect current personnel to sustainability-related data collection, analysis, analysis, and reporting.

We envisage our algorithm as useful for planning education content. We see individuals that hold mid and senior management roles in HEIs as the primary beneficiaries. Where individuals with course and programme management responsibilities seek to decide on the SDG-related content volume and type at the course and programme levels, our tool can help identify gaps. This can inform content plans. In a recent exercise, two of the authors evaluated course content across the offerings at one of the Schools in the university used as the source of data for the present study. The tool enabled the identification of extreme cases where there was no SDG content. The authors also used a parallel approach involving manual analysis and coding to validate the results and to provide further granularity. The value of the tool, from a planning perspective, is to identify courses that warrant further consideration, and this reduces the need to consider all course offerings at once.

Conclusion and future research

This study is a step towards streamlining data sourcing, analysis and reporting for HEIs that seek to substantiate claims against the SDGs. The algorithm is most useful for larger HEIs with many course offerings and a database of course outlines (or other, similar documentation) easily accessible for analysis. Where the HEI is smaller, fewer courses require scrutiny, so it may be the case that the appraisal process is less burdensome. The tool could still be useful though, to subsume workload. Where suitable datasets are more difficult to access, then there is a need to assess whether the effort involved in dataset assembly is worthwhile in the first instance. Without such a dataset, it will not be possible to implement the tool. For those institutions that do employ the tool, there is substantial scope to improve the efficiency of SDG content appraisal and reporting.

A variety of future research directions emerge from the present study. One research avenue could involve the application of the algorithm to research data. Most HEIs monitor research outcomes from faculty members. These data normally are stored in a central repository. Tags that apply to individual records such as title, abstract, field of research codes, and other indicators could be useful inputs to a semantic match algorithm, which then compares such indicators with SDG key terms.

Another research avenue could include finding ways to efficiently supplement outputs from the current algorithm to present a more well-rounded picture of SDG content in educational offerings. The current dataset does not include course assessment task information, for example. It may be the case that assessment tasks in each course do cover SDG-relevant concepts and ideas (Shephard et al. Citation2015). There is therefore a need to account for this SDG content in a way that meaningfully and efficiently integrates with the algorithmic approach. The present study does not offer guidelines as to how to select the best algorithm. While several scholars have begun to unpack the dimensions as to how HEIs can make choices in this regard (Leal Filho et al. Citation2020; Rosen Citation2020), there is a need to ensure their legitimacy, and this means investment in capabilities, systems and processes. A useful research direction could focus on how and when the use of decision-making tools such as the one we develop in this study integrates effectively in HEI strategy and implementation.

Supplemental Appendix

Download Zip (594 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank UNSW Business School for the generous funding that supported this project and Michael Zipperle for assistance with data preparation and analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abhayawansa, Subhash. 2022. “Swimming Against the Tide: Back to Single Materiality for Sustainability Reporting.” Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 13 (6): 1361–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-07-2022-0378.

- Adomßent, Maik, Daniel Fischer, Jasmin Godemann, Christian Herzig, Insa Otte, Marco Rieckmann, and Jana Timm. 2014. “Emerging Areas in Research on Higher Education for Sustainable Development – Management Education, Sustainable Consumption and Perspectives from Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of Cleaner Production 62:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.09.045.

- Antó, Josep M., José Luis Martí, Jaume Casals, Paul Bou-Habib, Paula Casal, Marc Fleurbaey, Howard Frumkin, et al. 2021. “The Planetary Wellbeing Initiative: Pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals in Higher Education.” Sustainability 13 (6): 3372–83. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063372.

- Arora, Priyank, Wei Wei, and Senay Solak. 2021. “Improving Outcomes in Child Care Subsidy Voucher Programs Under Regional Asymmetries.” Production and Operations Management 30 (12): 4435–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13506.

- Bayhantopcu, Esra, and Ignacio Aymerich Ojea. 2023. “Integrated Sustainability Management and Equality Practices in Universities: A Case Study of Jaume I University.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 25 (3): 631–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-02-2023-0054.

- Blasco, Natividad, Isabel Brusca, and Margarita Labrador. 2021. “Drivers for Universities’ Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals: An Analysis of Spanish Public Universities.” Sustainability 13 (1): 89–108. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010089.

- Cardiff, Philip, Malgorzata Polczynska, and Tina Brown. 2024. “Higher Education Curriculum Design for Sustainable Development: Towards a Transformative Approach.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 25 (5): 1009–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-06-2023-0255.

- Chagas, Ederson Jorge Melo das, José de Lima Albuquerque, Luiz Flávio Arreguy Maia Filho, and Alessandra Carla Ceolin. 2022. “Sustainable Development, Disclosure to Stakeholders and the Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from Brazilian Banks’ non-Financial Reports.” Sustainable Development 30 (6): 1975–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2363.

- Chandrasekaran, Dhivya, and Vijay Mago. 2022. “Evolution of Semantic Similarity—A Survey.” ACM Computing Surveys 54 (2): Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1145/3440755.

- Chang, Ming-Wei, Lev Ratinov, Dan Roth, and Vivek Srikumar. 2008. “Importance of Semantic Representation: Dataless Classification.” In Proceedings of the 23rd National Conference on Artificial Intelligence – Volume 2, 830–5. Chicago, IL: AAAI Press.

- Chou, Pei- I., and Ya-Ting Wang. 2024. “The Representation of Sustainable Development Goals in a National Curriculum: A Content Analysis of Taiwan’s 12-Year Basic Education Curriculum Guidelines.” Environmental Education Research 30 (4): 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2023.2273790.

- Crespo, Bárbara, Carla Míguez-Álvarez, María Elena Arce, Miguel Cuevas, and José Luis Míguez. 2017. “The Sustainable Development Goals: An Experience on Higher Education.” Sustainability 9: 1353–68. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081353.

- Day, Elizabeth L., Steven J. Petritis, Hunter McFall-Boegeman, Jacob Starkie, Mengqi Zhang, and Melanie M. Cooper. 2024. “A Framework for the Integration of Green and Sustainable Chemistry into the Undergraduate Curriculum: Greening Our Practice with Scientific and Engineering Practices.” Journal of Chemical Education 101 (5): 1847–57. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.3c00737.

- Dziubaniuk, Olga, Catharina Groop, Maria Ivanova-Gongne, Monica Nyholm, and Ilia Gugenishvili. 2024. “Sensemaking of Sustainability in Higher Educational Institutions Through the Lens of Discourse Analysis.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 25 (5): 1085–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-09-2023-0427.

- Fakir Mohammad, Razia, Preeta Hinduja, and Sohni Siddiqui. 2024. “Unveiling the Path to Sustainable Online Learning: Addressing Challenges and Proposing Solutions in Pakistan.” International Journal of Educational Management 38 (1): 136–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijem-07-2023-0334.

- Feng, Yunting, Kee-hung Lai, and Qinghua Zhu. 2020. “Legitimacy in Operations: How Sustainability Certification Announcements by Chinese Listed Enterprises Influence Their Market Value?” International Journal of Production Economics 224: 107563–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.107563.

- Findler, Florian, Norma Schönherr, Rodrigo Lozano, Daniela Reider, and André Martinuzzi. 2019. “The Impacts of Higher Education Institutions on Sustainable Development.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 20 (1): 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-07-2017-0114.

- Finsterwalder, Jörg, and Volker G. Kuppelwieser. 2020. “Equilibrating Resources and Challenges During Crises: A Framework for Service Ecosystem Well-Being.” Journal of Service Management 31 (6): 1107–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-06-2020-0201.

- Geng, Y., and N. Zhao. 2020. “Measurement of Sustainable Higher Education Development: Evidence from China.” PLoS One 15 (6): e0233747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233747.

- Global SDG Collaborators. 2018. “Measuring Progress from 1990 to 2017 and Projecting Attainment to 2030 of the Health-Related Sustainable Development Goals for 195 Countries and Territories: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.” The Lancet 392 (10159): 2091–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32281-5.

- Grano, Carolina, and Vanderli Correia Prieto. 2020. “Sustainable Development Goals in Higher Education.” In Proceedings on 25th International Joint Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management – IJCIEOM, edited by Zoran Anisic, Bojan Lalic, and Danijela Gracanin.

- Griebeler, Juliane Sapper, Luciana Londero Brandli, Amanda Lange Salvia, Walter Leal Filho, and Giovana Reginatto. 2022. “Sustainable Development Goals: A Framework for Deploying Indicators for Higher Education Institutions.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 23 (4): 887–914. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-03-2021-0088.

- Gutiérrez-Mijares, María Eugenia, Irene Josa, Maria del Mar Casanovas-Rubio, and Antonio Aguado. 2023. “Methods for Assessing Sustainability Performance at Higher Education Institutions: A Review.” Studies in Higher Education 48 (8): 1137–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2185774.

- Harispe, Sébastien, Sylvie Ranwez, Stefan Janaqi, and Jacky Montmain. 2015. Semantic Similarity from Natural Language and Ontology Analysis, Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Jones, David R. 2017. “Opening Up the Pandora’s Box of Sustainability League Tables of Universities: A Kafkaesque Perspective.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (3): 480–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1052737.

- Khare, Anshuman, and Brian Stewart. 2024. “Guest Editorial: Making an Impact – UN Sustainable Development Goals and University Performance.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 25 (5): 901–2. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-07-2024-607.

- Kioupi, Vasiliki, and Nikolaos Voulvoulis. 2020. “Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Assessing the Contribution of Higher Education Programmes.” Sustainability 12: 6701–718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176701.

- Leal Filho, Walter, Amanda Lange Salvia, and João Henrique Paulino Pires Eustachio. 2023. “An Overview of the Engagement of Higher Education Institutions in the Implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.” Journal of Cleaner Production 386: 135694–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135694.

- Leal Filho, Walter, Amanda Lange Salvia, Fernanda Frankenberger, Noor Adelyna Mohammed Akib, Salil K. Sen, Subarna Sivapalan, Isabel Novo-Corti, Madhavi Venkatesan, and Kay Emblen-Perry. 2020. “Governance and Sustainable Development at Higher Education Institutions.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 23 (4): 6002–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00859-y.

- Loosemore, Martin, Suhair Zaid Alkilani, and Rodney Murphy. 2021. “The Institutional Drivers of Social Procurement Implementation in Australian Construction Projects.” International Journal of Project Management 39 (7): 750–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2021.07.002.

- Manolis, Evangelos N., and Eleftheria N. Manoli. 2021. “Raising Awareness of the Sustainable Development Goals Through Ecological Projects in Higher Education.” Journal of Cleaner Production 279: 123614–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123614.

- Maurer, Cara C., Pratima Bansal, and Mary M. Crossan. 2011. “Creating Economic Value Through Social Values: Introducing a Culturally Informed Resource-Based View.” Organization Science 22 (2): 432–48. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0546.

- Miller, Kristel, James Cunningham, and Erik Lehmann. 2021. “Extending the University Mission and Business Model: Influences and Implications.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (5): 915–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1896799.

- Montalbán-Domingo, Laura, Tatiana García-Segura, M. Amalia Sanz, and Eugenio Pellicer. 2019. “Social Sustainability in Delivery and Procurement of Public Construction Contracts.” Journal of Management in Engineering 35 (2): 04018065-1–04018065-11. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0000674.

- Nagy, Júlia, József Benedek, and Kinga Ivan. 2018. “Measuring Sustainable Development Goals at a Local Level: A Case of a Metropolitan Area in Romania.” Sustainability 10 (11): su10113962–977. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113962.

- Opoku, Maxwell Peprah. 2024. “Exploring the Intentions of School Leaders Towards Implementing Inclusive Education in Secondary Schools in Ghana.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 27 (3): 539–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2021.1889034.

- Rosen, Marc A. 2020. “Do Universities Contribute to Sustainable Development?” European Journal of Sustainable Development Research 4 (2): em0112–115. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejosdr/6429.

- Roszkowska, Ewa, and Marzena Filipowicz-Chomko. 2020. “Measuring Sustainable Development in the Education Area Using Multi-Criteria Methods: A Case Study.” Central European Journal of Operations Research 28 (4): 1219–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10100-019-00641-0.

- Sánchez-Carracedo, Fermín, Jorge Ruiz-Morales, Rocío Valderrama-Hernández, José Manuel Muñoz-Rodríguez, and Antonio Gomera. 2019. “Analysis of the Presence of Sustainability in Higher Education Degrees of the Spanish University System.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (2): 300–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1630811.

- Sánchez-Carracedo, Fermín, Jordi Segalas, Gorka Bueno, Pere Busquets, Joan Climent, Victor G. Galofré, Boris Lazzarini, et al. 2021. “Tools for Embedding and Assessing Sustainable Development Goals in Engineering Education.” Sustainability 13 (21): su132112154–184. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112154.

- Schaltegger, Stefan, and Jacob Hörisch. 2017. “In Search of the Dominant Rationale in Sustainability Management: Legitimacy- or Profit-Seeking?” Journal of Business Ethics 145 (2): 259–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2854-3.

- Schiff, Daniel S., Jeonghyun Lee, Jason Borenstein, and Ellen Zegura. 2024. “The Impact of Community Engagement on Undergraduate Social Responsibility Attitudes.” Studies in Higher Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2260414.

- Serafini, Paula Gonçalves, Jéssica Morais de Moura, Mariana Rodrigues de Almeida, and Júlio Francisco Dantas de Rezende. 2022. “Sustainable Development Goals in Higher Education Institutions: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 370: 133473–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133473.

- Shephard, Kerry, John Harraway, Brent Lovelock, Miranda Mirosa, Sheila Skeaff, Liz Slooten, Mick Strack, Mary Furnari, Tim Jowett, and Lynley Deaker. 2015. “Seeking Learning Outcomes Appropriate for ‘Education for Sustainable Development’ and for Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 40 (6): 855–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1009871.

- Smith, Jo, and Paul Heyward. 2024. “Policy Efforts to Meet UNESCO’s Sustainable Development Goal 4: A 3-Pronged Approach.” Journal of Education for Teaching 50 (2): 266–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2023.2283422.

- Suchman, Mark C. 1995. “Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches.” The Academy of Management Review 20 (3): 571–610. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788.

- Thomas, Tom E., and Eric Lamm. 2012. “Legitimacy and Organizational Sustainability.” Journal of Business Ethics 110 (2): 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1421-4.

- Tierney, Aisling, Hannah Tweddell, and Chris Willmore. 2015. “Measuring Education for Sustainable Development.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 16 (4): 507–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-07-2013-0083.

- von Knorring, Mia, Hanna Karlsson, Elizabeth Stenwall, Matti Johannes Nikkola, and Maria Niemi. 2024. “Rethinking Higher Education in Light of the Sustainable Development Goals: Results from a Workshop and Examples of Implementation in a Medical University.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 25 (5): 927–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-07-2023-0268.

- Weber, Jana M., Constantin P. Lindenmeyer, Pietro Liò, and Alexei A. Lapkin. 2021. “Teaching Sustainability as Complex Systems Approach: A Sustainable Development Goals Workshop.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 22 (8): 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-06-2020-0209.

- Zhang, Yu, Morteza Saberi, and Elizabeth Chang. 2017. “Semantic-based Lightweight Ontology Learning Framework: A Case Study of Intrusion Detection Ontology.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Intelligence, 1171–7. Leipzig, Germany: Association for Computing Machinery.