ABSTRACT

Shared governance has emerged as an incrementally inclusive modification to common Western forms of governance, which are often top-down, bureaucratic, and individualistic in nature. Anti-oppressive movements call for structural changes which necessarily involve examining where and how decisions are made in post-secondary institutions. This systematic literature review synthesizes scholarship on shared governance in post-secondary settings. This research is guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for conducting systematic reviews, a priori protocol to steer the research process, and the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews. A review of 48 empirical papers published in peer-reviewed journals resulted in five main themes for shared governance in higher education: potentially interested parties; characteristics of governing leaders; principles and values of shared governance; processes of shared governance; and models of shared governance. We also identified gaps in the shared governance literature: underrepresentation of community (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) as well as Indigenous and diverse ways of knowing, and lack of attention to the diverse identities within the interested parties. We proceed to propose inclusive governance as a more appropriate term than shared governance.

Introduction

Contemporary educational leaders are faced with diverse, complex, and ever-changing environments that are characterized by intersecting economic, technological, educational, and social paradigms. Literature on university governance and academic unit governance commonly offers approaches and guidance that delineate strategies and guidelines for effective governance (e.g. Calvo and Bradley Citation2021; Deegan Citation1970; Owen and Grealish Citation2006). Notably, higher education governance remains challenged to create safer and more equitable institutions. One such obstacle is about decision-making – ‘who makes decisions; who has a voice, and how loud that voice is’ (Rosovsky Citation1990, 261)? How and why should certain decision-making mechanisms be adopted? How do we ensure that decolonial approaches build from relationality, explicitly acknowledging and drawing on our unique histories, perspectives, and experiences; and establish, implement, and revise governance structures or processes to be balanced across potentially interested parties (a term we use in this paper for students, faculty, staff, administrators, and community, instead of stakeholders, particularly because of the latter’s colonial connotation [Reed Citation2022])? These questions have become the basis of specific governance approaches and perspectives that seek to improve higher education governance (e.g. see Mangrum and Mangrum Citation2000; Pearce, Wood, and Wassenaar Citation2018; Phillips, Sweet, and Blyth Citation2011).

Johnston (Citation2003) defined shared governance as ‘the process that connects and holds in balance the governance structures contributing to institutional decision making’ (60). Shared governance has emerged as a widely supported approach to university governance (Bezzina and Cutajar Citation2013; Eckel Citation2000; Owen et al. Citation2018; Phillips, Sweet, and Blyth Citation2011). As an incrementally inclusive modification to common western forms of governance (Menon Citation2003), shared governance promises greater involvement of different actants in the operationalization of public universities (Boswell, Opton, and Owen Citation2017; Mercer-Mapstone Citation2020). Shared governance emphasizes effective representation of equity-deserving groups, racialized minorities, as well as self-determination for Indigenous peoples (McKivett et al. Citation2021; Sosa, Garcia, and Bucher Citation2022). Moreover, it confutes misconceptions about collective decision-making and the role of students/faculty in governance (Felten et al. Citation2019; Lizzio and Wilson Citation2009), and aims for greater inclusivity and social justice for many (Boland Citation2005; Dollinger and Mercer-Mapstone Citation2019).

Despite wide support in academic literature and some adoption in practice, shared governance concepts, approaches, and practices are varied. For instance, Owen and Grealish (Citation2006) proposed a Collaborative Change Model that folds collaborative principles like teamwork, mutual respect, and cooperation into shared governance systems to plan jointly, implement and evaluate change in clinical education. The main argument in the model is to develop structured and diverse working groups that establish ‘close contact through cross membership and [circulate] formal summaries of meeting discussion and decisions’ (19). While recognizing the significance of formal structures such as standing committees and an Annual Forum on Governance, Mangrum and Mangrum (Citation2000) emphasized the need to recognize, encourage and incorporate informal structures into governance systems because ‘a great deal of collaboration, idea sharing, and decision making happen constantly among members of the university in informal settings’ (10). In other words, their communication model of shared governance argues for increased alignment between formal and informal structures for effective decision making. Similarly, when it comes to interaction between potentially interested parties (i.e. who talks to whom) during decision-making, Lapworth (Citation2004) argued for a square-based pyramid that encourages enhanced communication among the decision-making bodies where ‘the steering core still occupies the over-arching position at the apex of the pyramid and drives institutional decision-making’ (311). Despite flexibility and broadness in this model, as Lapworth claimed, even this has elements of a top-down style of governance where students and community members remain excluded and reinforces a hierarchical Western model (Cardoso and dos Santos Citation2011; Dollinger and Mercer-Mapstone Citation2019; McKivett et al. Citation2021; Seale et al. Citation2015; Zdravković et al. Citation2018).

Because ‘shared governance can play a facilitative role in institutional change’ (Eckel Citation2000, 20) and is considered as an approach by colleges and universities in different contexts to dismantle structural barriers for some equity-deserving groups (e.g. Cardoso and dos Santos Citation2011; McKivett et al. Citation2021; Mouro et al. Citation2011), the current confusion about its conceptualization, interpretation and implementation calls for a much deeper investigation of how shared governance is understood globally, where the field currently stands in adopting or rejecting shared governance as a model, and how a broader understanding of the approach can be developed to contribute to knowledge building towards more fair systems. With this objective, this systematic literature review synthesizes scholarship on shared governance in post-secondary settings to discuss the ways shared governance is conceptualized and practiced in higher education institutions. A summary of the findings is presented with recommendations for future inquiry.

Methods

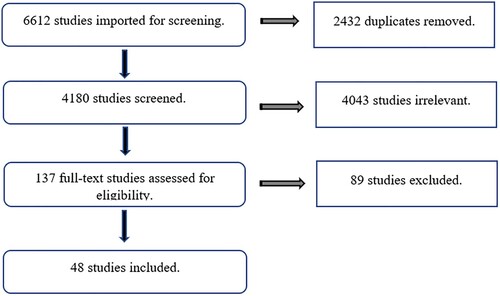

Our systematic review was informed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for conducting systematic reviews (Aromataris and Munn Citation2020). A priori protocol was developed to guide the research (Madesi, Raza, and Bharwani Citation2023) and is reported in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (Page et al. Citation2021). The research team generated a list of keywords and seed articles which an experienced evidence synthesis librarian developed into a comprehensive search strategy. Articles that discuss inclusive governance principles, concepts, approaches, models, or assessments in post-secondary contexts (i.e. university/Faculty-levels, research/community/student partnerships, and focusing on faculty, students, administrators, and internal and external interested parties) were targeted in this search.

Searches were initially run November 16, 2022, and updated January 11, 2023. Databases searched included: Medline All (OVID), Scopus (Elsevier), Web of Science (Clarivate), ERIC (Ebsco), Academic Search Complete (Ebsco), Education Research Complete (Ebsco), and PAIS Index (Proquest) (see Appendix 1 for all search strategies). Results were exported and uploaded to Covidence for deduplication and screening. Following a pilot of the selection criteria (Appendix 2), two researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts, and the full text. Screening disagreements were resolved through consensus.

An excel spreadsheet informed by JBI and Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used as a data synthesis form to extract the data and synthesize the included studies (McArthur et al. Citation2015). PRISMA 2020 checklist was used to maintain transparency in the systemic review (Appendix 3). In this systematic review, we employed a data synthesis form to comprehensively understand the purpose, methodological details, key findings, and limitations of the included studies. Guided by our main research question and the Population, Interest, Context, and Outcome (PICO) framework outlined in our protocol (Madesi, Raza, and Bharwani Citation2023), we initiated a deductive coding approach. This approach focused on gathering information relevant to specific categories: population (including local, First Nations, Metis, and Inuit, and global Indigenous Peoples and equity-deserving communities), interest (encompassing principles, values, models, processes, or assessments of inclusive governance), context (various post-secondary levels including university-level, faculty-level, research group level, and student level), and outcomes (transformation in post-secondary governance). For data analysis, we followed the six-step thematic analysis process proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). This began with familiarizing ourselves with the data and generating initial codes corresponding to the PICO elements. For example, under ‘population’, we collated information about the interested parties involved in shared governance within post-secondary contexts. We maintained a systematic record of this data in the ‘Participant Population’ column of our synthesis form. Similar procedures were applied for coding data related to interest, context, and outcome. Upon generating these initial codes, KR and AB (two of the authors), proceeded to identify themes and sub-themes. This was achieved by examining the collated data under each PICO category for recurrent patterns and insights. To ensure the rigor and consistency of our thematic analysis, these preliminary themes were reviewed by other team members, adhering to the principles of consistency and replicability in data collection, analysis, and reporting (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). Based on their feedback, we refined and definitively labeled the themes, which are presented in the results section. This methodological approach, underpinned by the PICO framework and thorough thematic analysis, enabled a structured and comprehensive examination of inclusive governance in post-secondary settings. The resulting themes not only align with our research objectives but also contribute to a deeper understanding of governance transformation in these contexts.

Results

The search resulted in 6612 records, of which 2432 were duplicates. 4180 records were screened and 137 underwent full-text review, which resulted in 48 studies included in the review (). Four out of the 48 articles were published between 1970 and 2000, while the remaining 44 were published between 2001 and 2022. 38 articles were qualitative in nature, seven quantitative descriptive, and three mixed methods.

Five main themes and several sub-themes were identified from this review. The main themes included: potentially interested parties; characteristics of governing leaders; principles and values of shared governance; processes of shared governance; and models of shared governance. These themes are discussed next followed by a discussion on the findings and recommendations for future research on the topic ().

Table 1. Overview of shared governance themes and definitions.

Potentially interested parties

In terms of who is included in shared governance, five types of potentially interested parties were identified: administrators, faculty, students, staff, and community members. Administrators were recognized as key interested parties in governance in all 48 articles. 21 articles focused on faculty involvement in academic affairs like pedagogy, curriculum development, and instructional policy (Calvo and Bradley Citation2021; Cook-Sather, Becker, and Giron Citation2020; Crellin Citation2010; Warshaw and Ciarimboli Citation2020); in administration such as administrative committees or boards (Bani-Hani and Al-Omari Citation2014); or in both academic and administrative matters (Alfred Citation1985; Almeyda and George Citation2018; Boswell, Opton, and Owen Citation2017; Bucklew, Houghton, and Ellison Citation2012; Fontaine et al. Citation2008; Hai and Anh Citation2022; Jiang and Xue Citation2021; Johnston Citation2003; Jones Citation2011; Kennedy et al. Citation2020; Lewis Citation2011; McDaniel Citation2017; Owen et al. Citation2018; Phillips, Sweet, and Blyth Citation2011; Sosa, Garcia, and Bucher Citation2022; Thompson, Burton, and Berrey Citation1994). 13 articles focused on student participation in academic affairs (Adeola and Bukola Citation2014; Dollinger and Mercer-Mapstone Citation2019; Felten et al. Citation2019; Seale et al. Citation2015; Zdravković et al. Citation2018), administrative affairs (Boland Citation2005; Cardoso and dos Santos Citation2011; Li and Zhao Citation2020; Lizzio and Wilson Citation2009), or both (Alfred Citation1985; Hall Citation2021; Menon Citation2003; Mouro et al. Citation2011). Only two articles discussed staff-student collaboration for shared governance where Bovill et al. (Citation2016) focused on cooperation for effective teaching and learning, and Mercer-Mapstone (Citation2020) outlined principles for enhancing collaboration between the students and staff.

Community engagement in institutional governance was the focus of only two articles, both grounded in Indigenous ways of governance. McKivett et al. (Citation2021) discussed the importance of the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives ‘[to create] culturally responsive medical curricula through medical education research’ that should be based upon listening, facilitating, supporting, and working alongside ‘Indigenous pedagogies and knowledge paradigms’ (67). Wise et al. (Citation2020) discussed the establishment of an Indigenous advisory council (i.e. Consejo) at an Ecuadorian public university that consisted of 11 Indigenous people of different nationalities which aimed to increase Indigenous student university enrollment and graduation as well as to ‘stimulate relevant indigenous research and increase the agency of indigenous participants in research’ (342). The Consejo achieved these objectives but was constrained by a Western legislative authority and by civilizational differences between Indigenous and Western ways; where Indigenous decision-making processes are led by collective approval, contrasted with Western approaches grounded in majority-rule or unanimous voting practices.

Characteristics of governing leaders

Certain qualities and characteristics of higher education leaders are more likely to enable shared governance. These characteristics include a disposition to learning, participation, commitment to relationships, and characteristics that result in transparency.

Being a learner creates necessary conditions to acquire knowledge about students’ and faculty members’ diverse socio-cultural backgrounds and thus perhaps accommodate their academic and professional needs (Calvo and Bradley Citation2021; McKivett et al. Citation2021). Learning can also foster an openness to find newer ways to solve academic and administrative challenges (Mercer-Mapstone Citation2020), enhance communication with and among potentially interested parties (Mangrum and Mangrum Citation2000), and increase faculty, student, and staff participation in governance (Cook-Sather, Becker, and Giron Citation2020; Felten et al. Citation2019; Wise et al. Citation2020).

Advocates of participatory decision-making believe that diverse voices ought to be included in the planning, implementation, and revision of shared governance structures. For example, educators, teachers, and students would co-create curriculum and pedagogical practices (Menon Citation2003; Seale et al. Citation2015); and administrators would engage faculty and/or students in institutional decision-making (Almeyda and George Citation2018; Hai and Anh Citation2022; Lewis Citation2011; Sattarzadeh-Pashabeig et al. Citation2018; Zhuang, Liu, and Hu Citation2022).

A commitment to relationships allows leaders to connect and interact with other potentially interested parties to jointly identify, analyze, and solve problems. Thompson, Burton, and Berrey (Citation1994) provided an example of a president who listened deeply to faculty through town meetings to keep them abreast of external developments but also to directly respond to their concerns and issues. Sattarzadeh-Pashabeig et al. (Citation2018) noted that interrelationship between all potentially interested parties is an element of shared governance practice.

Transparency emerges when leaders promote openness, communication, and accountability that builds trust and mutual respect among members. These important characteristics of leadership underpin the active process of trust-building; they build trust in the decision-making process by openly communicating decisions and actively including input from potentially interested parties (Selzer and Foley Citation2018). Open, trusting communication also helps in ‘negotiating sensitive matters or points of potential conflict’ among potentially interested parties (Wise et al. Citation2020, 347). Pearce, Wood, and Wassenaar (Citation2018) noted that transparent leaders have the potential to align administrative goals (such as achieving marketing objectives or meeting financial targets) with faculty requirements (such as knowledge development and scholarly initiatives) for institutional progress. While recognizing the significance of formal structures, Sattarzadeh-Pashabeig et al. (Citation2018) emphasized the significance of informal structures to build transparency, among other ethical practices.

Principles and values of shared governance

Principles and values orient us as individuals to build and shape – ‘shepherd’ our governance systems (Pearce, Wood, and Wassenaar Citation2018). The literature expresses principles and values including courage (Pearce, Wood, and Wassenaar Citation2018), democracy (participation) (Boland Citation2005), desire to contribute (Li and Zhao Citation2020), as well as ‘mutual trust and respect; transparency; non-discrimination and equality; accountability and the rule of law; and participation and inclusion’ (Wise et al. Citation2020, 346).

The principles and values of different institutions of higher education will also differ depending on whether the institution is public or private, and based on the degree of autonomy or influence from the state, corporations, or communities, reflecting their different intentions or purposes, which in turn also shapes the necessary characteristics of its leaders.

A common concern with living these principles and values is whether it is practical. For example, many fear that student participation in governance will slow down the decision-making process. Menon (Citation2003) argued that if there is no negotiation from a place of equal representation, the speedier decision may be a weaker decision, for it will ‘remain one party’s or one individual’s vision of higher education’ (244). In this way, shared governance is an ethical stabilizer. The practicality emerges from its ability to live the very values it espouses at the outset when developing these models: to encourage power sharing to protect against the misuse of authority by individuals in power while also empowering diverse faculty, students and staff to participate and contribute more fully in decision-making (Pearce, Wood, and Wassenaar Citation2018). Boswell, Opton, and Owen (Citation2017) also noted that faculty and staff empowerment was associated with increased job satisfaction.

Processes of shared governance

Shared governance processes include decision-making mechanisms and procedures to enshrine our stated values, such as valuing diversity, enshrining reflexivity and adopting training programs for the leaders and interested parties involved in decision-making. They help promote dialogue, inclusion, and greater participation of potentially interested parties.

While diversity was described as a core value, we found that many struggled with mechanisms to genuinely and practically value diversity (Selzer and Foley Citation2018). Enshrining pluralism in governance means incorporating diverse ecologies of knowledge in a manner that promotes equal representation in decision-making processes and decisions to foster more inclusive curriculum, pedagogy, and learning environments as described in the literature, but would also apply to research and administrative paradigms as well. In pedagogical governance, Calvo and Bradley (Citation2021) provided examples of models and initiatives that incorporate Latinx cultural capital in the curriculum, such as social work practices to de-center whiteness to promote non-Western frameworks of knowledge, and inclusive course materials from historically marginalized communities. McKivett et al. (Citation2021) argued to incorporate sovereignty-deserving communities; ‘Indigenous representation is necessary in day-to-day curriculum activities, medical education leadership structures, the student cohort, organizational hierarchies, and in ongoing external community engagement efforts’ (7). Additionally, Bovill et al. (Citation2016) highlighted the importance of student-staff partnerships as a mechanism to draw on the knowledge and skills that they both possess. Lizzio and Wilson (Citation2009) recommended enhancing student participation in governance through role-related interventions (e.g. written role statements), training programs, and trust building. Cook-Sather, Becker, and Giron (Citation2020) argued that students should be provided space and encouragement to bring their whole self to the partnership. Similarly, Cardoso and dos Santos (Citation2011) provided case studies of power sharing with students in higher education settings where their role was reconceptualized from being clients or consumers to ‘key institutional actors and as members of the academic community’ (243); and Mouro et al. (Citation2011) gave examples where nurses collaborated with the management to develop and implement a shared governance model through power sharing, consultations, and accountability.

Training programs may: develop skills to effectuate shared governance; impart knowledge about existing governance structures; or orient potentially interested parties about new or emerging governance initiatives. Adeola and Bukola (Citation2014) emphasized the need for ‘courses, seminars and workshops on leadership training … for student leaders to assist them [to] develop the skills needed to perform their challenging roles’ (404). Johnston (Citation2003) also emphasized the need to increase overall faculty knowledge about governance structures and processes through information sharing, mentoring new faculty members, and increasing faculty participation in institutional committees and boards.

Shared decision-making processes require the representation, participation, and involvement of interested parties: faculty, students, and staff. Student representation on university committees was emphasized to democratize the decision-making process related to administrative affairs (e.g. Adeola and Bukola Citation2014; Boland Citation2005; Deegan Citation1970; Dollinger and Mercer-Mapstone Citation2019) and teaching and learning (e.g. Bovill et al. Citation2016; Cardoso and dos Santos Citation2011; Cook-Sather, Becker, and Giron Citation2020; Felten et al. Citation2019). Others (e.g. Fontaine et al. Citation2008; Jones Citation2011; Kennedy et al. Citation2020; Pearce, Wood, and Wassenaar Citation2018; Sattarzadeh-Pashabeig et al. Citation2018; Wise et al. Citation2020; Zhuang, Liu, and Hu Citation2022) highlighted the importance of faculty involvement in academic and administrative decision-making processes to create transparent systems.

To increase the representation of faculty, students, and staff, Sosa, Garcia, and Bucher (Citation2022) proposed five tenants: intersectional representation (based upon race, class, and disciplines); expanded representation of staff of color and part-time/adjunct faculty; active dismantling of Whiteness, racism, and microaggression; additional oversight and accountability; and critical reflexive process. Calvo and Bradley (Citation2021) provided case studies from the US where faculty were involved in initiatives to disrupt Whiteness in the curriculum and fight institutional racism. Similarly, Mangrum and Mangrum (Citation2000) invited administrators to realize the significance of informal communication networks by taking non-Western approaches that adopt non-hierarchical, unplanned/unstructured, and oral communication channels to faculty engagement in decision-making.

Participatory and consultative decision-making processes create space for faculty, students, and staff to shape decision-making. For institutional decision-making, Owen and Grealish (Citation2006) outlined principles for collaborative group process that included: establishing the tasks and responsibilities of the group, its parameters, and terms of reference; designing communication channels; ensuring mutual respect for different views; and monitoring outcomes of the group’s work. If the decisions are pedagogical, Bovill et al. (Citation2016) suggested several guiding principles for co-creation: ‘starting small rather than undertaking co-creation of an entire program curriculum; making clear that entry into co-creation is voluntary; ensuring that collaboration is meaningful and not an empty promise; and regularly questioning motivations and practices’ (205).

In terms of exemplars of collaborative decision-making, Fontaine et al. (Citation2008) provided an example of a decision-making framework from nursing that included initial plan-sharing with faculty, discussion about the initiative, call for further dialogue, appointment of a task force, and implementation of the plan in the light of the feedback from the task force. Crellin (Citation2010) provided an example of shared governance through an approval procedure adopted at Southern New Hampshire University to approve transition to online learning. The process included seven steps: thorough review of the initiative by the potentially interested parties and professors; curriculum committee review; multitiered and multidirectional idea sharing and negotiation between the interested parties and curriculum committee; faculty monitoring to ensure quality; course reviews by faculty; empowerment of faculty to decide course content; and course audit through the evaluation of the course designer’s performance.

Formal mechanisms that promote reflexivity enshrine shared governance by encouraging self-examination amongst leaders to look inwards and question their own actions and assumptions about institutional governance (Mercer-Mapstone Citation2020). Thompson, Burton, and Berrey (Citation1994) included a narration of their college president’s self-reflection textured by deep listening with the faculty (manifested through continuous communication, faculty feedback, and follow-up meetings) to create a balance between internal and external demands. Reflexivity can also work as a method to question the ways students are currently viewed in academic institutions and to reimagine their roles more broadly (Felten et al. Citation2019). This points to shared governance as an agile and responsive approach. It also calls for paying attention to the representation of diverse student voices when students are involved in projects with professors (Seale et al. Citation2015). Bovill et al. (Citation2016) argued for ‘taking an inclusive approach to partnership’ that ‘requires staff and institutions to reframe their perceptions of students (and colleagues) who have traditionally been marginalized’ (204). Sosa, Garcia, and Bucher (Citation2022) emphasized a critically reflective process that focuses on the political and racialized dynamics of decision-making.

To establish representative, participatory, and consultative decision-making processes, all relevant policies, initiatives, and other information must be communicated with potentially interested parties (Boswell, Opton, and Owen Citation2017; Deegan Citation1970; Lapworth Citation2004; Li and Zhao Citation2020; Mangrum and Mangrum Citation2000; Owen and Grealish Citation2006; Phillips, Sweet, and Blyth Citation2011). A literature review on shared governance by Boswell, Opton, and Owen (Citation2017) also noted the relationship between communication and work engagement. Bovill et al. (Citation2016) emphasized that ‘student skepticism and resistance to co-creation might be addressed through more effective communication’ (200). Deegan (Citation1970) marked intercommunication as a distinguishing factor between traditional/separatist models and participatory models of governance. The former maintains hierarchic systems of information sharing via segments or groups where each segment/group (e.g. students or administration) works in isolation from the other(s). The latter, participatory model, promotes collegiality through ‘the delineation of areas of primary responsibility for faculty, administrators, and students, but with established procedures for intercommunication and prior consultation before positions harden’ (11).

Informal communication channels complement formal structures of shared governance to shape decisions on issues related to leadership, agenda-setting, scheduling, implementation of decisions, and outcome monitoring (Mangrum and Mangrum Citation2000). Acknowledging and aligning formal and informal meetings showcases an administrator’s belief in shared governance and can foster meaningful cooperation among faculty and administration. Similarly, Owen and Grealish (Citation2006) presented a collaborative change model that manages change within an institution through enhanced communication among different potentially interested parties. A similar model was proposed by Phillips, Sweet, and Blyth (Citation2011) that promotes collaboration, communication, and knowledge-sharing at an academic unit level or institutional level.

Models of shared governance

Models are the holistic combinations of governance structures and processes. A structure includes decision-making entities such as committees and boards under which roles and responsibilities of different potentially interested parties are outlined to guide the decision-making process; and processes include the policies, procedures, and ways that shape where and how decisions are made.

Alfred (Citation1985) described three models of shared governance that we have simplified as: a co-creative model; a networked model that included the private sector; and an internal consulting model. The co-creative model (called a Functional Model) is where the administration draws on specialized knowledge possessed by the faculty and students to perform specific functions like ‘curriculum construction, recruitment and retention strategies, and assessment of student educational needs and interests’ (34). The second model is a collaborative networked model comprising ‘four primary decision-making groups: faculty; trustees and administrators; agencies of state government; and private-sector organizations’ (35); this model uses sophisticated information systems to understand the shared interests across these four bodies to make decisions about both academic matters (e.g. curriculum development, admission requirements, faculty recruitment, etc.) and administrative issues (e.g. financial affairs and policymaking). The third model is an internal consulting model that encourages faculty and students to participate through a rewards/incentive model; in this model, faculty members can shape their financial advancement and students can shape their future employability – and in return, faculty and students join administrators in making decisions related to institutional governance (e.g. departmental strategic planning and management).

Xiao (Citation2022) identified five governance models at a Chinese university. A Pluralistic Co-governance Model involves the potentially interested parties such as ‘dean, assistant deans, department heads and their assistants, professors, administrative staff, and students’ (9) in decision-making. These parties join different committees that make collaborative decisions on departmental or institutional policies and regulations. The second governance model mentioned by Xiao is the Academic-led Model which is predominantly adopted in basic science disciplines like science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) for academic development (e.g. advancing scholarship, research projects, etc.). Under this model, academic scholars guide the decision-making process based upon their scholarly expertise. Additionally, academic staff are fully supported in undertaking research projects and improving student skills. The Academic-administrative Coordination Model, the third governance model identified by Xiao, develops on the notion that academic work (e.g. teaching, research) and administrative work (e.g. policy formation, program management) need to be separated and assigned to people in those respective fields because ‘when people are assigned to work in the best of their specialties, the most effective result is achieved in the work’ (11). According to Xiao, the fourth governance model is the Academic-social Interaction Model that is common in social sciences and focuses on the scholarly and practical application of their programs. ‘The development of scholarly research is seen in the expansion of graduate studies to match world standards. In practical application, the schools, or departments design programs to focus on producing graduates to meet the needs of practical work fields’ (11). An example of such a model includes joint degree programs where faculty from other universities teach specific courses. Finally, The State-led Model prioritizes state policies and agendas in education and ‘calls for a unification of the administrative and research activities by the creation of a school or department council to provide guidelines and lead the program or projects assigned by the state’ (12). Under this model, the government provides fundings for specific research projects and the expert scholars from an institution collaborate to work on the project (Xiao Citation2022).

Bucklew, Houghton, and Ellison (Citation2012) discussed four academic governance models from the US that are centered around faculty unionization and its role in collective bargaining. A comprehensive model positions the faculty union as the exclusive bargaining agent between the faculty and the university administration to make decisions about faculty issues (e.g. wages, recruitment and retention policies, and leaves and holidays) through a non-symbiotic relationship. In contrast, the co-determination model is a symbiotic relationship developed between the faculty union and university administration to bargain on traditional labor issues (e.g. faculty recruitment, curriculum development, etc.) while ensuring that the contract between the university and faculty allows continuity in ongoing decision-making. Meanwhile, the permissive model allows universities to deviate from collective bargaining processes when modifying policies provided that they align with ‘traditional provisions and practices that ensure faculty involvement’ (386). Lastly, a restrictive or limited model covers a limited range of topics that can be negotiated by the parties. Some examples provided by Bucklew, Houghton, and Ellison (Citation2012) where restrictive models can be observed are the appointments of adjunct faculty, sessional instructors, or teaching assistants.

Deegan (Citation1970) proposed a participatory model that called for establishing a collegial senate, inclusive of administration, faculty, and students, and included legislative and administrative guidelines. Legislatively, a non-traditional tokenism approach encourages participation in decision-making rather than simple presence in committees and is used to select faculty and students to represent their special interests and be rewarded for their efforts. Amongst this range of representatives, this non-traditional approach ‘calls for the delineation of areas of primary responsibility for faculty, administrators, and students but with established procedures for intercommunication and prior consultation before positions harden’ (11). Administratively, newer ideas are supported; institution-wide interests are emphasized; faculty and students are kept informed of state and systemic policies and progress; and institutional challenges are thoroughly analyzed with input from faculty and students.

Mangrum and Mangrum (Citation2000) presented a communication model of shared governance that has four levels. Level 1 defines faculty responsibilities to include teaching, governance, service, and research. Level 2 acknowledges and argues for alignment between formal structures (such as administrative offices, decanal units) and informal structures (such as faculty gatherings and unplanned events). Level 3 concerns the processes for communication and ‘delineates who talks to whom about what topic in what kind of setting and how participants accomplish interactions’ (19). For example, formal communication channels consist of committees that oversee planning, assessments, budgets, and curriculum, and have assigned leaders, asymmetrical relations, agendas/procedures, schedule, established membership, and written documents. Informal communication platforms are networks of individuals that may discuss similar topics such as planning and budgets, but they are characterized by fluid and changing leaders, symmetrical relations, minimal planning, and peer information/knowledge. Level 4 is focused on the content of communication between formal and informal structures and its impact on the outcomes for decision-making, implementation and monitoring.

Phillips, Sweet, and Blyth (Citation2011) proposed a pragmatic collaborative model that can be used at an academic unit and an institutional level. At either level, faculty and administrators coordinate to create professional learning communities (PLC) where faculty provide input in academic areas (promotion and tenure, curriculum, research, and program assessment) and administrative areas (human resources, grants office, financial data, institutional research, professional development funds, research funds, and action agenda funds). For issues relevant to a single academic unit (e.g. College of Education), the PLC advances recommendations to the dean who takes them to the provost/president for approval from the regents. For issues affecting the entire university, the PLC moves recommendations to the faculty senate then to the provost and finally to the president who submits them to the regents for approval.

This systematic review has identified five main themes that are focused on shared governance potentially interested parties, characteristics of governing leaders, principles and values, processes, and models. These themes highlight the areas that have been the focus of research in the past, and also point to future directions for further research on the topic.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we describe potentially interested parties, personal characteristics of leaders, principles, values, processes, and models of shared governance. We proceed to identify gaps in the literature, then we argue that inclusive governance might be a more appropriate term to describe the current progress and future direction of shared governance.

In describing the principles, values, processes, and models of shared governance, we observed that shared governance in post-secondary contexts is a mechanism for equitable outcomes. Many articles highlighted the significance of shared governance towards decolonizing higher education, democratizing decision-making, increasing creative faculty–student partnerships, including Indigenous students, broadening engagement of potentially interested parties, increasing flexibility in system development, promoting accountability, and deepening community development (Boland Citation2005; Li and Zhao Citation2020; Sosa, Garcia, and Bucher Citation2022; Zhuang, Liu, and Hu Citation2022). The literature identifies five potentially interested parties that might participate in shared governance (i.e. administrators, faculty, students, staff, and community members) (Hai and Anh Citation2022; Hall Citation2021; Xiao Citation2022); but we noted the absence of non-human actants (representatives of those who do not otherwise have a voice) such as planetary interests. We also noted several enabling characteristics to participate effectively in shared governance: trust, mutual respect, disposition to transparency, participatory approaches, commitment to learning, and open communication (Almeyda and George Citation2018; Warshaw and Ciarimboli Citation2020; Wise et al. Citation2020). The principles and values of shared governance included epistemic pluralism (Calvo and Bradley Citation2021) and power sharing (Alfred Citation1985; Bezzina and Cutajar Citation2013; Xiao Citation2022). Shared governance processes included: reflexivity (Sosa, Garcia, and Bucher Citation2022), training for potentially interested parties, consultation with concerned faculty or interested parties in decision-making, and implementation procedures (Adeola and Bukola Citation2014; Boswell, Opton, and Owen Citation2017; Cardoso and dos Santos Citation2011; Johnston Citation2003; Owen and Grealish Citation2006; Wise et al. Citation2020). Finally, several models of shared governance were found that blend structures and processes into a cohesive model or approach to shared governance (see Alfred Citation1985; Bucklew, Houghton, and Ellison Citation2012; Calvo and Bradley Citation2021; Deegan Citation1970; Mangrum and Mangrum Citation2000; Xiao Citation2022). We identified gaps in the literature. Community members are underrepresented in the shared governance literature. By community we do not mean the university community but the one external to the institution that is served by the university (and that could offer insights to shape the university).

We found that only two (McKivett et al. Citation2021; Wise et al. Citation2020) of the 48 reviewed papers that emphasized community engagement also drew on Indigenous ways of governance. Because educational institutions contribute to social change and transformation, community representation in governance is essential to reflect community issues and civilizational knowledge from Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples to solve those issues through curriculum, research, and governance (Siemens Citation2012). We argue that future research must explore novel structures and processes to enshrine community in governance; and draw on subjugated Indigenous and non-Indigenous ways of knowing. To shape this body of research, we believe the theory of shared ethical space is important; ‘the ethical space [built on collective moral considerations] offers itself as the theatre for cross-cultural conversations in pursuit of ethically engaging diversity [Indigenous and non-Indigenous] and disperses claims to the human order’ (Ermine Citation2007, 202). Similarly, future research and initiatives to increase community representation in educational structures must also pay attention to diversity across both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, and to the socio-cultural, historic, and civilizational knowledges within these communities.

The extant literature on shared governance could benefit from a broader and more intersectional conceptualization of who is sharing governance. While ‘shared governance’ is generally seen as a positive approach to engage a range of potentially interested parties (e.g. faculty, students, and staff) in decision-making, we noticed a lack of attention to the diverse identities within these groups. These identities may be marked by different genders, sexualities, races, socioeconomics, ethnic backgrounds, religions, language abilities, citizenship, ability, educational status, or positions/designations within an institution (e.g. as a part-time continuing student or a sessional instructor). A more robust appreciation for this intersectionality might also impact the environment, skills, or training that certain groups might need to participate in governance actively and effectively. Shared governance scholars advocate for distributing decision-making power among those with interests in an educational institution or academic program. However, overlooking the diversity within groups, whether faculty, students, or community members, might lead to superficial engagement rather than genuine inclusion. A society cannot decolonize its institutions, revitalize Indigenous knowledge systems, and strive for more equitable and innovative institutions without transforming its governance: where and how decisions are made. And on this path, words matter. Words are shortcuts to concepts that shape our expectations and intuitive understanding of how we operate. Drawing upon equity, diversity, and inclusivity (EDI), anti-oppressive, and relational approaches that call for the removal of systemic barriers and biases against individuals or groups of different races, genders, faiths, sexualities, and backgrounds to ensure their active integration in workplaces and decision-making (Government of Canada Citation2021), we argue that a more appropriate term than shared governance is inclusive governance. Inclusive governance emphasizes constructive, productive, and creative dialogues within the institution that draws on anti-oppressive and relational foundations to continually redress barriers and ensures equitable and balanced access to opportunities and resources for all members of the academic and external community. Inclusive governance reimagines the underlying structures, systems, and processes of collaboration, communication, and dialogue to promote collective decision-making from equal footings.

We justify this shift in nomenclature because ‘inclusive’ governance identifies and amplifies all voices to achieve balance and shared understanding while ‘shared’ governance simply divides the stage. A shared decision may or may not mean equitably shared or balanced; but the term inclusive reimagines structural and procedural interventions (how the table is set and what principles and values inform this process), community engagements (who is invited to the table, how, and why), and dialogics (how the conversation is constructed to facilitate shared understanding and to include all actants).

Any form of inclusive governance presumes a starting point: that we share values. The current literature, while it provides important examples of principles and values, fails to comprehensively articulate and define our values – and especially our shared values. In an increasingly divided world, perhaps what we share is more important than where we disagree.

After all, inclusive governance is not only about structures but also the ways in which we go about our business, which requires us to pay close attention to the intertwined notions of principles, values, and characteristics or leaders – which together shape our shared fate. As we encounter more differences as an academic community – and as a society – we desperately need to understand our shared values from which we can then prioritize the dispositions, practices, and structures that help us to recognize, respect, and value differences which necessarily includes a range of activities including leadership practices across society (Global Pluralism Monitor Citationn.d.).

Inclusive governance offers a less hierarchic, more relational, and constructive approach to involve potentially interested parties – a gap identified in current conceptualizations and implementations of shared governance. This was noticed in Warshaw and Ciarimboli (Citation2020) and several other examples (see Adeola and Bukola Citation2014; Bani-Hani and Al-Omari Citation2014; Selzer and Foley Citation2018) where faculty members, for example, were included in the implementation of decisions that were made somewhere else by the higher administration. As Eckel (Citation2000) concluded, for most decisions, ‘they [the administration] sold the process to the faculty, conducted the individual interviews, interpreted the data they collected, garnered board support, and, in the end, made and announced the final decisions’ (28). Such practices often de-motivate faculty to engage in future administrative affairs or the overall governance of an institution (Jones Citation2011) and thus let the decision-making process be dominated by certain individuals (e.g. administrators) perhaps belonging to certain demographics. Similarly, increasing student representation in committees or boards may diversify their membership (e.g. Wise et al. Citation2020), but this may not necessarily decolonize decision-making if the underlying structures, processes, and values (and linguistics) remain untouched.

Future research in inclusive (shared) governance would need to pay attention to Indigenous ways of knowing. Additionally, a lack of attention to the unprecedented hyper-diversity and complexity within the academy and community runs the risk of certain subgroups’ voices being diluted, marginalized, or misunderstood, whether they be from socioeconomic or ability tranches, gender, sexuality, or ethnic, religious, racial, and linguistic minorities. Future research should seek to develop governance structures and processes that enshrine a commitment to including hyper-diversity, and do so in a safe, constructive, productive manner. Arguably, the democratization of university governance mechanisms, structures and processes should begin with greater participation and engagement of all potentially interested parties (and worldviews) in a shared ethical space to begin the very design of those governance mechanics, drawing upon our shared values which might include, as starting points, the principles of transparency, participation, impact, and pluralism.

Conclusion

Our systematic review of the literature on shared governance in higher education identified key principles, values, processes, and models, revealing that inclusive governance may be a more appropriate term than shared governance. This shift in terminology reflects a deeper commitment to recognizing, respecting, and valuing Indigenous and diverse voices as both a dignified outcome and a mechanism to address systemic barriers.

Inclusive governance offers a relational and constructive approach to involving all potentially interested parties in decision-making. It challenges colonial practices while acknowledging their benefits, addresses historical systemic barriers, and provides generative possibilities for alternative shared futures. By grounding governance in shared values, relationality, and diverse epistemes, higher education institutions can better include diverse and Indigenous communities and contribute to broader social transformation.

Future research should explore innovative governance models that integrate Indigenous and diverse non-Indigenous ways of knowing and ensure broad community representation. Special attention should be paid to identifying our shared values, integrating oral knowledges, and considering literature in non-English languages. Additionally, acknowledging the hyper-diversity within academic and community settings is crucial for developing truly inclusive governance practices.

Adopting inclusive governance can lead to more constructive, productive, and creative decision-making in higher education institutions, fostering a more collaborative and supportive environment for all stakeholders. This approach not only enhances equity and inclusivity but also contributes to the democratization or decolonization of educational institutions, promoting broader social change and transformation.

Supplemental Appendix

Download PDF (972.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adeola, A. O., and A. B. Bukola. 2014. “Students’ Participation in Governance and Organizational Effectiveness in Universities in Nigeria.” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5 (9): 400–4.

- Alfred, R. L. 1985. “Power on the Periphery: Faculty and Student Roles in Governance.” New Directions for Community Colleges 49:25–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.36819854904.

- Almeyda, M., and B. George. 2018. “Faculty Support for Internationalization: The Case Study of a United States Based Private University.” European Journal of Contemporary Education 7 (1): 29–38.

- Aromataris, E., Munn, Z. (eds). 2020. “JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis.” JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Bani-Hani, K., and A. A. Al-Omari. 2014. “The Shared Governance Practices in the Jordanian Universities: Faculty Members Perspective.” Journal of Institutional Research South East Asia 12 (2): 152–79.

- Bezzina, C., and M. Cutajar. 2013. “The Educational Reforms in Malta: The Challenge of Shared Governance.” International Studies in Educational Administration 41 (1): 3–18.

- Boland, J. A. 2005. “Student Participation in Shared Governance: A Means of Advancing Democratic Values?” Tertiary Education and Management 11 (3): 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2005.9967147.

- Boswell, C., L. Opton, and D. C. Owen. 2017. “Exploring Shared Governance for an Academic Nursing Setting.” Journal of Nursing Education 56 (4): 197–203. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20170323-02.

- Bovill, C., A. Cook-Sather, P. Felten, L. Millard, and N. Moore-Cherry. 2016. “Addressing Potential Challenges in co-Creating Learning and Teaching: Overcoming Resistance, Navigating Institutional Norms and Ensuring Inclusivity in Student-Staff Partnerships.” Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education Research 71:195–208.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bucklew, N., J. D. Houghton, and C. N. Ellison. 2012. “Faculty Union and Faculty Senate co-Existence: A Review of the Impact of Academic Collective Bargaining on Traditional Academic Governance.” Labor Studies Journal 37 (4): 373–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160449X13482734.

- Calvo, R., and S. Bradley. 2021. “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Lessons Learned Dismantling White Supremacy in a School of Social Work.” Advances in Social Work 21 (2/3): 920–32. https://doi.org/10.18060/24466.

- Cardoso, S., and S. M. dos Santos. 2011. “Students in Higher Education Governance: The Portuguese Case.” Tertiary Education and Management 17 (3): 233–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2011.588719.

- Cook-Sather, A., J. W. Becker, and A. Giron. 2020. “While We Are Here: Resisting Hegemony and Fostering Inclusion Through Rhizomatic Growth via Student-Faculty Pedagogical Partnership.” Sustainability 12:67–82. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176782.

- Crellin, M. A. 2010. “The Future of Shared Governance.” New Directions for Higher Education 151:71–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.402.

- Deegan, W. L. 1970. Student Government and Student Participation in Junior College Governance – Models for the 1970s. Los Angeles.: University of California.

- Dollinger, M., and L. Mercer-Mapstone. 2019. “What’s in a Name? Unpacking Students’ Roles in Higher Education Through Neoliberal and Social Justice Lenses.” Teaching & Learning Inquiry 7 (2): 73–89. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.7.2.5.

- Eckel, P. D. 2000. “The Role of Shared Governance in Institutional Hard Decisions: Enabler or Antagonist?” The Review of Higher Education 24 (1): 15–39. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2000.0022.

- Ermine, W. 2007. “The Ethical Space of Engagement.” Indigenous Law Journal 6 (1): 193–204.

- Faguet, J. P., and M. Shami. 2022. “The Incoherence of Institutional Reform: Decentralization as a Structural Solution to Immediate Political Needs.” Studies in Comparative International Development 57:85–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-021-09347-4.

- Felten, P., S. Abbot, J. Kirkwood, A. Long, T. Lubicz-Nawrocka, L. Mercer-Mapstone, and R. Verwoord. 2019. “Reimagining the Place of Students in Academic Development.” International Journal for Academic Development 24 (2): 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1594235.

- Fontaine, D. K., N. A. Stotts, J. Saxe, and M. Scott. 2008. “Shared Faculty Governance: A Decision-Making Framework for Evaluation the DNP.” Nursing Outlook 56 (4): 167–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2008.02.008.

- Global Pluralism Monitor. n.d. https://monitor.pluralism.ca/.

- Government of Canada. 2021. “Best Practices in Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Research.” https://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/nfrf-fnfr/edi-eng.aspx.

- Hai, P. T. T., and L. T. K. Anh. 2022. “Academic Staff’s Participation in University Governance – a Move Towards Autonomy and its Practical Problems.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (8): 1613–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1946031.

- Hall, R. 2021. “Students as Partners in University Innovation and Entrepreneurship.” Education + Training 63 (7/8): 1114–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-01-2021-0003.

- Jiang, H., and Y. Xue. 2021. “Perceptions of Faculty Leadership in University Governance: A Case Study.” Chinese Education & Society 54 (5–6): 207–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10611932.2021.1990626.

- Johnston, S. W. 2003. “Faculty Governance and Effective Academic Administrative Leadership.” New Directions for Higher Education 124:57–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.130.

- Jones, W. A. 2011. “Faculty Involvement in Institutional Governance: A Literature Review.” Journal of the Professoriate 6 (1): 117–35.

- Kennedy, D. R., T. K. Harrell, N. M. Lodise, T. J. Mattingly, J. P. Norenberg, K. Ragucci, P. Ranelli, and A. S. Stewart. 2020. “Current Status and Best Practices of Shared Governance in US Pharmacy Programs.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 84 (7): 909–18. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7281.

- Lapworth, S. 2004. “Arresting Decline in Shared Governance: Towards a Flexible Model for Academic Participation.” Higher Education Quarterly 58 (4): 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2004.00275.x.

- Lewis, V. M. 2011. “Faculty Participation in Institutional Decision Making at Two Historically Black Institutions.” The ABNF Journal 22 (2): 33–40.

- Li, X., and G. Zhao. 2020. “Democratic Involvement in Higher Education: A Study of Chinese Student e-Participation in University Governance.” Higher Education Policy 33 (1): 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-018-0094-8.

- Lincoln, S. Y., and E. G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. California: Sage.

- Lizzio, A., and K. Wilson. 2009. “Student Participation in University Governance: The Role Conceptions and Sense of Efficacy of Student Representatives on Departmental Committees.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (1): 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802602000.

- Madesi, S., K. Raza, and A. Bharwani. 2023. “Inclusive Governance in Post-secondary – Systematic Review Protocol.” PROSPERO 2023 CRD42023390890. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID = CRD42023390890.

- Mangrum, F. G., and C. W. Mangrum. 2000. “The Connection Between Formal and Informal Meetings: Understanding Shared Governance in the Small College Environment.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Central States Communication Association, Detroit, USA.

- McArthur, A., J. Klugárová, H. Yan, and S. Florescu. 2015. “Innovations in the Systematic Review of Text and Opinion.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3): 188–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000060.

- McDaniel, M. M. 2017. “Institutional Climate and Faculty Governance in Higher Education: A Shift from Capitalist to Shared Governance Models.” Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor 29:34–44.

- McKivett, A., K. Glover, Y. Clark, J. Coffin, D. Paul, J. N. Hudson, and P. O’Mara. 2021. “The Role of Governance in Indigenous Medical Education Research.” Rural and Remote Health 21:64–73.

- Menon, M. E. 2003. “Student Involvement in University Governance: A Need for Negotiated Educational Aims?” Tertiary Education and Management 9 (3): 233–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2003.9967106.

- Mercer-Mapstone, L. 2020. “The Student-Staff Partnership Movement: Striving for Inclusion as We Push Sectorial Change.” International Journal for Academic Development 25 (2): 121–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1631171.

- Mouro, G., H. Tashjian, T. Daaboul, K. Kozman, F. Alwan, and A. Shamoun. 2011. “On the Scene: American University of Beirut Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon.” Nursing Administration Quarterly 35 (3): 219–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3181ff3b9d.

- Owen, D. C., C. Boswell, L. Opton, and C. Meriwether. 2018. “Engagement, Empowerment, and job Satisfaction Before Implementing an Academic Model of Shared Governance.” Applied Nursing Research 41:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2018.02.001.

- Owen, J., and L. Grealish. 2006. “Clinical Education Delivery – A Collaborative, Shared Governance Model Provides a Framework for Planning, Implementation and Evaluation.” Collegian 13 (2): 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1322-7696(08)60519-3.

- Page, M. J., J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, et al. 2021. “The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews.” BMJ 2021:372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Pearce, C. L., B. G. Wood, and C. L. Wassenaar. 2018. “The Future of Leadership in Public Universities: Is Shared Leadership the Answer?” Public Administration Review 78 (4): 640–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12938.

- Phillips, W., C. Sweet, and H. Blyth. 2011. “Using Professional Learning Communities for the Development of Shared Governance.” Journal of Faculty Development 25 (4): 18–23.

- Reed, M. 2022. “Should We Banish the Word ‘Stakeholder’”? https://www.fasttrackimpact.com/post/why-we-shouldn-t-banish-the-word-stakeholder?postId = 1a6b9631-56a5-416e-a796-86d6dfb30d87.

- Rosovsky, H. 1990. The University: An Owner’s Manual. New York: Norton & Company.

- Sattarzadeh-Pashabeig, M., F. Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, M.-M. Sadoughi, A. Khachian, and M. Zagheri-Tafreshi. 2018. “Characteristics of Shared Governance in Iranian Nursing Schools: Several Souls in one Body.” Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 23 (5): 344–51. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_4_18.

- Seale, J., S. Gibson, J. Haynes, and A. Potter. 2015. “Power and Resistance: Reflections on the Rhetoric and Reality of Using Participatory Methods to Promote Student Voice and Engagement in Higher Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 39 (4): 534–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.938264.

- Selzer, R., and T. Foley. 2018. “Implementing Grassroots Inclusive Change Through a Cultural Audit.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 13 (3): 284–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-10-2016-1455.

- Siemens, L. 2012. “The Impact of a Community-University Collaboration: Opening the “Black Box”.” Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research 3 (1): 5–25. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjnser.2012v3n1a94.

- Sosa, L. V., G. A. Garcia, and J. Bucher. 2022. “Decolonizing Faculty Governance at Hispanic Serving Institutions.” Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 22 (3): 325–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/15381927221126781.

- Taylor, S. K., K. J. Aronson, and R. K. Mahtani. 2021. “Summarising Good Practice Guidelines for Data Extraction for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 26 (3): 88–90. http://ebm.bmj.com/.

- Theriault, S. 2012. “Indigenous Peoples and Climate Change Policies: A Comparative Assessment of Indigenous Governance Models in Canada.” In Local Climate Change Law: Environmental Regulation in Cities and Other Localities, Benjamin J. Richardson (dir.), Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Thompson, P. H., T. Burton, and C. Berrey. 1994. “Shared Leadership.” Leadership in Metropolitan Universities 5 (3): 61–70.

- Warshaw, J. B., and E. B. Ciarimboli. 2020. “Structural or Cultural Pathways to Innovative Change? Faculty and Shared Governance in the Liberal Arts College.” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 122 (8): 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146812012200814.

- Wise, G., C. Dickinson, T. Katan, and M. C. Gallegos. 2020. “Inclusive Higher Education Governance: Managing Stakeholders, Strategy, Structure and Function.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (2): 339–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1525698.

- Xiao, H. 2022. “A Case Study of the Governance Models of Schools and Departments in Tsinghua University, China.” Educational Planning 29 (1): 5–17.

- Zdravković, M., T. SerdinÅ¡ek, M. SoboÄan, S. Bevc, R. Hojs, and I. Krajnc. 2018. “Students as Partners: Our Experience of Setting Up and Working in a Student Engagement Friendly Framework.” Medical Teacher 40 (6): 589–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1444743.

- Zhuang, T., B. Liu, and Y. Hu. 2022. “Legitimizing Shared Governance in China’s Higher Education Sector Through University Statues.” European Journal of Education 57 (1): 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12493.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Search terms

Database(s): Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to November 18, 2022 Search Strategy:

Appendix 2: Literature criteria and systematic review protocol

Inclusive Governance in Post-Secondary – Systematic Review Protocol

1. Title of a Qualitative Review Protocol

Inclusive governance in post-secondary contexts: A qualitative systematic review protocol.

2. Review Question

This review will employ the modified Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICo) approach to developing a systematic review question.

P – Population

First Nation, Métis, Inuit, global Indigenous, and diverse global governance concepts and practices in post-secondary contexts

I – Interest

Inclusive governance principles, concepts, approaches, models, or assessments

C – Context

Post-Secondary contexts (university-level, Faculty-level, research group level, and student level)

Question: What Indigenous and diverse global inclusive governance concepts and practices could inform post-secondary governance transformation?

3. Introduction

The essence of this systematic review emerges from a shared mission to dismantle structural barriers and systemic discrimination in Faculty governance on a path to equitable outcomes and Indigenous self-determination. By making Faculty governance more inclusive of Indigenous and non-Indigenous equity-deserving community voices and realizing our constitutional mandate to Indigenous self-governance, we anticipate several benefits. In the academy, we will more effectively understand, reflect, and respond to equity-deserving community needs and aspirations; proactively respond to equity-deserving community objectives with research, education, and student services; and co-create new ways of co-governing higher education with Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

The overarching purpose of this systematic review is to gather evidence that will inform the co-design of an inclusive governance model for post-secondary governance transformation. For purposes of this review, the following terms will be understood as follows:

Inclusive refers to the active, intentional, and ongoing engagement with diversity (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2022).

Governance: Good governance is defined by the Institute of Governance as drawing on four key dimensions Who has power? Who makes decisions? How do stakeholders make their voices heard? How account is rendered

Indigenous refers to ‘minority status, significant historical attachment to land and natural resources, prior occupation, cultural distinctiveness, an experience of colonisation, oppression, marginalization or dispossession, and self-identification.’ (Theriault Citation2012, p. 246)

Decolonization is about ‘cultural, psychological, and economic freedom’ for Indigenous people with the goal of achieving Indigenous sovereignty – the right and ability of Indigenous people to practice self-determination over their land, cultures, and political and economic systems. (Interdependence: Global Solidarity and Local Actions)

Indigenous Peoples in Canada: Section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982 declares that Indigenous peoples in Canada include First Nations, Inuit, and Métis (FNMI). FNMI are the first peoples of the land. First Nations and Inuit are groups that have lived on the land now called Canada since time immemorial; Métis are a distinct Indigenous people with a distinct culture arising from the intermarriage of fur traders and First Nations women post-contact.

Global Indigenous: International Labour Organization Convention No. 169 describes Indigenous people globally as tribal peoples in independent countries whose social, cultural, and economic conditions distinguish them from other sections of the national community and whose status is regulated wholly or partially by their own customs or traditions or by special laws or regulations. Peoples in independent countries who are regarded as indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country, or a geographical region to which the country belongs, at the time of conquest or colonization or the establishment of present state boundaries and who irrespective of their legal status, retain some or all their own social, economic, cultural, and political institutions.

Institutional reform refers to the ‘changes to the rules of the game that determine how collective decisions are taken and resources raised and expended for public purposes’ (Faguet and Shami Citation2022, p. 83).

Collaborative decision-making refers to a process with the involvement of two or more stakeholders who fully communicate with each other to reach an agreement on final decision.

On August 19, 2022, a preliminary search for existing systematic reviews on the topic has been conducted on the Campbell Collaboration, JBI Evidence Synthesis, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO, and found that the review question has not been addressed previously.

4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

1.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

(1) Peer-Reviewed Articles

(2) Qualitative, Quantitative, Mixed Methods, Text, and Opinions

(3) Any language

(4) Inclusivity: to embrace the active, intentional, or ongoing engagement with diversity and promotes authenticity, consensus, epistemic pluralism, parallel paths, relationality, or trust.

(5) Governance: encompassing any individual(s), process(es), or body(ies) that shape the vision, mission, strategy, direction, or ways of making decisions.

(6) Post-secondary (all types of higher education including technical schools, universities, colleges, relating to any discipline and including offices, subunits, student collaborations, and research programs within a post-secondary institution)

1.4.2. Exclusion criteria

1. Not peer-reviewed

2. Blogs, conferences proceedings, magazine articles, book chapters

3. Not governance related (not specific policies unless related to the direction, vision, mission, strategy, or ways of making decisions)

4. Not post-secondary

5. Not including diversity in an active, intentional, or ongoing basis

1.5. Search Strategy

This search will consider papers published by both commercial and academic publishers. The review team has contacted an experienced research librarian at the University [Name removed for anonymous review] for help with refining search terms, developing a search strategy and navigating the different databases.

The search strategy for this review will be conducted in a three-phase process:

Phase one consists of two steps:

the identification of initial key words (see section 1.3 above) based on knowledge of the field to perform an initial search.

the analysis of text words contained in the titles and abstracts of papers, and of the index terms used in a bibliographic database to describe relevant articles to build comprehensive and specific search strategy for each included database.

Phase two involves implementing database-specific searches for each database included in this protocol.

Search Rationale: published literature that meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Details of the search terms are in the search strategy in appendix 1.

Six Databases Developed and Searched:

1. Web of Science

2. Scopus

3. ERIC

4. Education Research Complete

5. Academic Search Complete

6. Medline

Phase three involves the review of the reference lists of all studies that are retrieved for appraisal to search for additional studies.

The search strategy will aim to find qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, text and opinion peer reviewed articles in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. An initial limited search consisting of eight articles has been undertaken followed by analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract, and of the index terms used to describe article. This informed the development of a search strategy which will be tailored for each information source. Please see appendix 1 for search strategy details.

1.6. Assessment of Methodological Quality

All records that are eligible for inclusion in this review will be assessed for methodological quality using an Excel sheet. The following steps will be followed:

(1) The three reviewers have met, discussed, and concurred on the methodical procedures of how a decision to include or exclude a study will be made before critical appraisal commences.

(2) All the three reviewers will independently rate the interrater reliability agreement before any screening starts.

(3) The review team has agreed to set 80% as the interrater reliability agreement rate.

(4) Two reviews will screen all the records for inclusion and exclusion.

(5) Reviewers are blinded to each other’s assessment and assessments can only be compared once initial appraisal of an article is completed by both reviewers.

(6) Where there is a lack of consensus, discussion between reviewers should occur.

(7) In case of disagreements between the two reviewers, the third reviewer will be responsible for resolving conflicts.

(8) All included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies will be critically appraised using the MMAT tool. Text and Opinion included studies will be critically appraised using the JBI checklists. See appendix 2 for mixed methods studies and appendix 3 for the standard JBI critical appraisal instruments for text and opinion studies.

1.7. Data Extraction

To ensure that similar data across all the included studies is maintained, the MMAT’s systematic review standardized data extraction tools will be employed for all included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. This review will use the standard JBI data extraction tool for text and opinion studies.

Data will be extracted from papers included in the review to determine the characteristics of included studies, risk of bias assessments, risk of error and improving validity and reliability.

The rationale for providing sufficient information about included studies facilitates readers to assess the generalisability and replicability of the findings from this review and establish value of the pooled analysis. The data extracted will include specific details about the populations, context, culture, geographical location, study methods and the phenomena of interest relevant to the review question and specific objectives.

Data extraction form will be piloted, and reviewers will receive training before extraction starts (Taylor, Aronson, and Mahtani Citation2021). Instructions will be given with extraction forms highlighting codes and definitions used in the form to reduce subjectivity and to ensure consistency. An Excel data extraction sheet will be developed following the criteria and process above.

Data extraction will constitute the following details:

Population

Local Indigenous Peoples: First Nation, Métis, Inuit (and which specifically)

Global Indigenous Peoples: name of specific Nation/community/ /region/Peoples.

Local or global Equity deserving community: Name of specific community (: i.e. people of color, LGBTQ, women, people with different abilities, etc.)

Community (internal or external) engaged + description, I.e. who are the drivers?

Other relevant demographics

Interest

Description of Principles

Description of Values

Description of Models (structures, processes, approaches, practises) Is a system transformation described?

If is a transformation, is the prior context, described

If is a transformation, is the intention or impetus described?

If it is a transformation, who was engaged and how?

If it is a transformation, is implementation described, (if so, describe of implementation approach, actions, and lessons)

Impact or outcome described or measured of articulated principles, values, models, or practises

Assessment suggested or used + description

Other

Context

Students, staff or faculty

Type of Higher Education institution (university, college, technical school, etc)

Indigenous Higher Education entity?

Level of Higher Education (full institution-level; faculty or school-level; research team-level; student-student level)

Specific decision-making body involved