ABSTRACT

Routine diagnosis of Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG) and Mycoplasma synoviae (MS) is performed by collecting oropharyngeal swabs, followed by isolation and/or detection by molecular methods. The storage temperature, storage duration and the type of swab could be critical factors for successful isolation or molecular detection. The aim of this study was to compare the influence of different types of cotton-tipped swab stored at different temperatures, on the detection of MG and MS. To achieve this, combined use of traditional culture analysis (both agar and broth), with modern molecular detection methods was utilized. Performances of wooden and plastic shaft swabs, both without transport medium, were compared. Successful culture of M. gallisepticum was significantly more efficient from plastic swabs when compared to wooden, whereas no difference was seen for the re-isolation of M. synoviae. Storage at 4°C compared to room temperature also increased the efficiency of culture detection for both Mycoplasma species. When stored at room temperature, PCR detection limits of both MG and MS were significantly lower for wooden compared to plastic swabs. The qPCR data showed similar detection limits for both swab types when stored at both temperatures. The results suggest that swabs with a plastic shaft are preferred for MG and MS detection by both culture and PCR. While a lower storage temperature (4°C) is optimal for culture recovery, it seems that both temperatures investigated here are adequate for molecular detection and it is the swab type which carries a greater influence.

Introduction

Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG) and Mycoplasma synoviae (MS) are important poultry pathogens worldwide, both responsible for substantial economic losses. Oropharyngeal swabs collected from suspected infected flocks are routinely analysed to confirm the presence of mycoplasmas by culture and/or molecular methodology. Sample storage temperature and the type of swab could influence successful detection (Christensen et al., Citation1994; Zain & Bradbury, Citation1995; Zain & Bradbury, Citation1996; Daley et al., Citation2006; Ferguson-Noel et al., Citation2012). The use of suitable transport media (such as mycoplasma broth or charcoal) has been advised for the transportation of samples.

As favourable transportation of samples for culturing may be the most important factor affecting the successful detection of mycoplasmas (Drake et al., Citation2005), it is important to consider that field samples normally arrive at the laboratory 1–3 days after sampling. For PCR detection of MG or MS, results can be influenced by various factors, including the amount of DNA recovered, which could depend on the type of swab used, as well as the DNA extraction method (Brownlow et al, Citation2012).

The aim of this study was to compare two types of dry cotton swabs (wooden versus plastic shafts) which were stored at two different temperatures. Additionally, we investigated the effect of a longer duration between sample taking and laboratory processing. The influences of these factors on detection of MG and MS by isolation, and conventional PCR and real-time PCR were assessed.

Materials and methods

Mycoplasma strains and culture

Two mycoplasma type strains were used throughout the study: MG PG31 and MS WVU 1853. Both strains were titrated using the viable counts method according to Miles et al. (Citation1938) and expressed as colony-forming units (CFU)/ml. Briefly, strains were 10-fold diluted up to 10−7 in mycoplasma broth. Then, 100 µl of each strain dilution were inoculated onto mycoplasma agar (MA) plates, using one plate per dilution. Both broth and agar media were prepared as previously reported (Bradbury, Citation1977; Zain & Bradbury, Citation1995). The plates were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 7 days before colonies were counted using a dissecting microscope. Titres were determined as 1.63 × 108 and 4.7 × 107 CFU/ml for MG and MS, respectively.

Swabs

The performances of the following types of cotton-tip dry swab without transport medium were compared: wooden shaft and plastic shaft (Alpha Laboratories Ltd., Eastleigh, UK). For each mycoplasma species, each type of swab was used for culture or molecular analysis: swabs were stored at 4°C and room temperature (RT; 21–23°C), for 1, 2 and 3 days post inoculation (dpi). At each time point, eight swabs of each type were sampled. In addition, cotton swabs with plastic shafts in Amies charcoal transport medium (Deltalab, Barcelona, Spain) were used for comparison.

Experimental design

MG and MS stock cultures with known titres were serially diluted (neat to 10−7). Each series of wooden or plastic swabs, as well as the charcoal media swabs, were dipped into these broth dilutions for 15 s. Subsequently, swabs were stored at either 4°C or RT as described above. Then, MG and MS recovery was attempted by culture and molecular methods (see below). Both culture recovery and molecular detection were repeated in triplicate for all samples.

Mycoplasma recovery by culture

Following storage at different temperatures, each of the dry (plastic and wooden) and charcoal swabs were plated onto MA and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After 7 days of incubation, colonies were quantified using a score from 0 to 4 as previously described (Ley et al., Citation2003).

Molecular detection of mycoplasmas

Swabs intended for mycoplasma molecular detection were dipped into 600 µl of working solution D (4M guanidinium thiocyanate, 25 mM sodium citrate, pH 7; 0.5% sarcosyl, 0.1M 2-mercaptoethanol) (Chomczynski & Sacchi, Citation2006) and stored at −20°C for a minimum of 3 h. DNA was then extracted using the DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Manchester, UK), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and stored at −20°C until use. The extracted DNAs were tested using a duplex PCR targeting the MG mgc2 gene and the MS vlhA gene (Moscoso et al., Citation2004). DNAs were also tested in duplicate using a commercial quantitative PCR (qPCR) kit for both MG and MS detection (BioChek, Reeuwijk, Netherlands) on the Rotor-gene Q platform (Qiagen). Obtained Ct values were compared against a previously established standard curve (data not shown) of known concentrations, where relative log REU values were obtained.

Statistical analysis

Detection limits obtained from both culture and conventional PCR were analysed to identify statistically significant differences using the Student t-test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Mycoplasma recovery by culture

M. gallisepticum

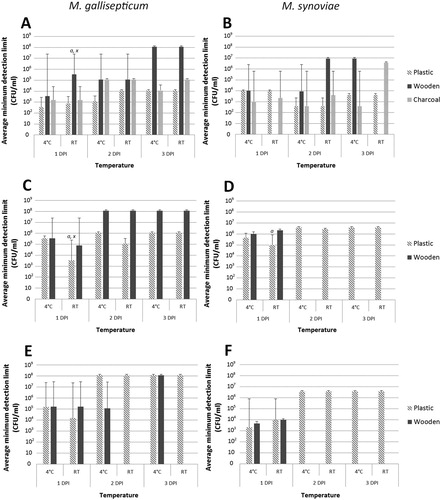

Culture of MG from swabs stored at RT showed that recovery was significantly more efficient for plastic (7.62 × 102 CFU/ml) than wooden (3.49 × 105 CFU/ml) swabs (P < 0.01) ((A)). Plastic swabs also had the greatest detection ability for MG culture from swabs stored at 4°C (3.49 × 102 CFU/ml) compared to RT (7.62 × 102 CFU/ml) ((A)), though there were no significant differences. The same was true at 2–3 dpi, as the plastic swabs showed greater detection ability compared to the wooden swabs, with only the high concentration sample (1.17 × 108 CFU/ml) showing a successful culture from wooden swabs by 3 dpi.

Figure 1. Comparison of each swab type following storage at 4°C or room temperature (RT). (A) Culture efficiency for MG; (B) Culture efficiency for MS; (C) PCR detection of MG; (D) PCR detection of MS; (E) qPCR detection of MG; (F) qPCR detection of MS. Data shown as mean of the highest dilution producing a positive culture result, with standard error margins. Groups with the notation of “a” indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences within the same temperature, whereas “x” indicates significant differences against the corresponding group at the other temperature.

M. synoviae

M. synoviae By 1 dpi we were able to isolate MS to a minimum of 4.7 × 103 CFU/ml from plastic and wooden swabs stored at 4°C and plastic swabs stored at RT. The ability to re-detect MS from plastic swabs did not alter throughout for either temperature. No MS were isolated from wooden swabs stored at RT at 1 or 3 dpi, however high concentration samples were detected at 2 dpi ((B)).

Molecular detection of mycoplasmas

M. gallisepticum

At 1 dpi, minimum PCR detection limits were on average significantly lower for plastic (3.49 × 103 CFU/ml) compared to wooden (7.62 × 104 CFU/ml) swabs when stored at RT (P < 0.05), whereas the two swab types showed no difference in detection limits when stored at 4°C ((C)). At later sampling points, the plastic swabs showed a greater ability to detect MG for both incubation temperatures. Similarly, the MG qPCR assay had greater detection capability when applied to plastic swabs stored at RT (1.63 × 104 CFU/ml) compared to wooden swabs (1.63 × 105 CFU/ml) at 1 dpi. However, similar to PCR data, both swab types showed the same sensitivity at 4°C ((E)). At 2 and 3 dpi, only the wooden swabs stored at 4°C were positive for MG, with all plastic swabs positive, although only at a higher concentration (1.17 × 108) compared to 1 dpi.

M. synoviae

By PCR, plastic swabs showed a lower minimum detection limit compared to wooden swabs when stored for 24 h at 4°C (4.7 × 105 and 1 × 106 CFU/ml) and a significantly (P < 0.05) lower result when stored at RT (1 × 105 and 2.2 × 106 CFU/ml, respectively) ((D)). At 2–3 dpi, it was only possible to detect MG from the plastic swabs. In contrast, the MS qPCR showed the same detection sensitivity at 1 dpi for both types of swabs at RT (1 × 104 CFU/ml), but a greater efficiency when applied to plastic swabs at 4°C (plastic = 2.2 × 103 CFU/ml; wooden = 4.7 × 103 CFU/ml) ((F)). Results at 2 and 3 dpi were similar to the PCR detection, with no wooden swabs positive for MS.

Discussion

Typically, when potentially infected poultry are sampled for mycoplasma detection, cotton-tipped swabs are transported to the laboratory by the following day; however, this may take several days depending on the location and method. While it is advised that transportation should also include ice or a cold pack to preserve sample integrity, this may not always be possible. For this reason, we investigated the influences of storage at two temperatures (4°C and room temperature), and several incubation times (1–3 dpi) on the recovery of MG and MS using molecular and traditional culture methodologies. Previous work has highlighted the difference between swab types (Zain & Bradbury, Citation1995; Ferguson-Noel et al., Citation2012); however we report the first study to combine the use of traditional culture analysis (both agar and broth), with modern molecular detection methods.

Findings from this study showed that dry plastic and charcoal swabs (both with a plastic shaft) had a similar ability to detect MG via culture when stored at 4°C and RT. In contrast, while not significant, it appears that charcoal swabs were more effective for culturing MS when stored at 4°C, with both plastic shaft swabs out-performing the wooden shaft. For both MG and MS, the dry plastic and charcoal swabs had a greater sensitivity to recover when stored at 4°C, suggesting that transporting swab samples on ice is advantageous for successful detection (Zain & Bradbury, Citation1996).

In this study, the charcoal swabs showed a similar level of detection, irrespective of the storage temperature or duration, perhaps due to the preserving properties of the charcoal medium, negating the effects of temperature fluctuations. The type of transport medium and swab type used for sample preservation have been shown to vary in ability to culture both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria (Tan et al., Citation2014), with a possible reduction in recovery ability after 24 h (Roelofsen et al., Citation1999).

On the culture of mycoplasmas, it appears that, for both MG and MS, samples collected using wooden swabs and stored at RT could be detrimental for the detection of these organisms, by either isolation or PCR (especially for MS). In this study, although a reduced number of colonies were recovered for MG, no viable colonies were recovered for MS from wooden swabs stored at RT for either 1 or 3 dpi. Similarly, reduced levels of MG or MS detection were found in wooden swabs stored at RT when detection was attempted by PCR. The growth rate and viability of MG and MS can be also affected by the pH of the broth (Lin et al., Citation1984; Ferguson-Noel et al., Citation2013) and it was previously hypothesized that greater humidity and lower temperature protected against the effect of low pH (Zain & Bradbury, Citation1996). This could be particularly true for MS, which may no longer be viable under a low pH (Ferguson-Noel et al., Citation2013). In the present study, while the broth pH was not measured during incubation, a colour indicator alteration suggested an alteration in pH, alongside the difference in physical features of the wooden compared to the plastic swab (Ismail et al., Citation2013).

Using molecular methods to detect MG, plastic swabs at RT initially displayed the greatest sensitivity. This could be related to permissive mycoplasma growth temperatures, which ranged from 20°C to 45°C (Brown et al., Citation2011). Previous work has reported that MG grown in mycoplasma broth and incubated at room temperature initially shows an increased titre up to 8 h post inoculation, followed by a rapid decline in viability (Christensen et al., Citation1994). Additionally, Zain and Bradbury (Citation1996) demonstrated that the viability of MG on wet swabs reduces following 4 h of incubation at 24–26°C. In the present study, molecular data showed that while the total genomic presence (viable and non-viable) increased, the number of viable colonies decreased when swabs were stored at RT. This was further emphasized at 2 and 3 dpi, as only the samples containing the highest concentrations of MG and MS were detected from plastic swabs, with no detections possible at RT (MG) or any temperature (MS) from wooden swabs.

In conclusion, results from the current study suggest that swabs with a plastic shaft should be preferred over those with a wooden shaft for MG and MS detection by culture, PCR and qPCR. While a lower storage temperature (4°C) is better for culture recovery, it seems that both temperatures investigated here are adequate for molecular detection, and the swab type is the bigger factor in determining a positive recovery.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank BioChek for the qPCR kits that were used for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bradbury, J.M. (1977). Rapid biochemical tests for characterization of the mycoplasmatales. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 5, 531–534.

- Brown, D.R., May, M., Bradbury, J.M., Balish, M.F., Calcutt, M.J., Glass, J.I., Tasker, S., Messick, J.B., Johansson, K.-E. & Neimark, H. (2011). Genus I. Mycoplasma. In N.R. Krieg, J.T. Staley, D.R. Brown, B.P. Hedlund, B.J. Paster, N.L. Ward, W. Ludwig, & W.B. Whitman (Eds.), Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (pp. 575–611). New York: Springer.

- Brownlow, R.J., Dagnall, K. & Ames, C.E. (2012). A comparison of DNA collection and retrieval from two swab types (cotton and nylon flocked swab) when processed using three Qiagen extraction methods. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 57, 713–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.02022.x

- Chomczynski, P. & Sacchi, N. (2006). The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction: twenty-something years on. Nature Protocols, 1, 581–585. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.83

- Christensen, N.H., Christine, A.Y., McBain, A.J. & Bradbury, J.M. (1994). Investigations into the survival of Mycoplasma gallisepticum, Mycoplasma synoviae and Mycoplasma iowae on materials found in the poultry house environment. Avian Pathology, 23, 127–143. doi: 10.1080/03079459408418980

- Daley, P., Castriciano, S., Chernesky, M. & Smieja, M. (2006). Comparison of flocked and rayon swabs for collection of respiratory epithelial cells from uninfected volunteers and symptomatic patients. Jounal of Clinical Microbiology, 44, 2265–2267. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02055-05

- Drake, C., Barenfanger, J., Lawhorn, J. & Verhulst, S. (2005). Comparison of easy-flow Copan liquid Stuart’s and Starplex swab transport system for recovery of fastidious aerobic bacteria. Jounal of Clinical Microbiology, 43, 1301–1303. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1301-1303.2005

- Ferguson-Noel, N. & Noormohammadi, A.H. (2013). Mycoplasma synoviae Infection. In D.E. Swayne, J.R. Glisson, L.R. McDougald, L.K. Nolan, D.L. Suarez, & N. Venugopal (Eds.), Diseases of Poultry (pp. 900–906). Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell by John Wiley & Sons.

- Ferguson-Noel, N., Laibinis, V.A. & Farrar, M. (2012). Influence of swab material on the detection of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae by real-time PCR. Avian Diseases, 56, 310–314. doi: 10.1637/9972-102411-Reg.1

- Ismaïl, R., Aviat, F., Michel, V., Le Bayon, I., Gay-Perret, P., Kutnik, M. & Fédérighi, M. (2013). Methods for recovering microorganisms from solid surfaces used in the food industry: a review of the literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10, 6169–6183. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10116169

- Ley, D.H. & Yoder, H.W. (2003). Mycoplasma gallisepticum Infection. In B.W. Calneck, Mosby-Wolfe (Eds.), Diseases of Poultry (pp. 194–207). Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell by John Wiley & Sons.

- Lin, M.Y. & Kleven, S.H. (1984). Improving the Mycoplasma gallisepticum and M. synoviae antigen yield by readjusting the pH of the growth medium to the original alkaline state. Avian Diseases, 28, 266–272. doi: 10.2307/1590152

- Miles, A.A., Misra, S.S. & Irwin, J.O. (1938). The estimation of the bactericidal power of the blood. Journal of Hygiene (London), 6, 732–749.

- Moscoso, H., Thayer, S.G., Hofacre, C.L. & Kleven, S.H. (2004). Inactivation, storage, and PCR detection of mycoplasma on FTA® filter paper. Avian Diseases, 48, 841–850. doi: 10.1637/7215-060104

- Roelofsen, E., van Leeuwen, M., Meijer-Severs, G.J., Wilkinson, M.H. & Degener, J.E. (1999). Evaluation of the effects of storage in two different swab fabrics and under three different transport conditions on recovery of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Jounal of Clinical Microbiology, 37, 3041–3043.

- Tan, T.Y., Yong Ng, L.S., Fang Sim, D.M., Cheng, Y. & Hui Min, M.O. (2014). Evaluation of bacterial recovery and viability from three different swab transport systems. Pathology, 46, 230–233. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000074

- Zain, Z.M. & Bradbury, J.M. (1995). The influence of type of swab and laboratory method on the recovery of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae in broth medium. Avian Pathology, 24, 707–716. doi: 10.1080/03079459508419109

- Zain, Z.M. & Bradbury, J.M. (1996). Optimising the conditions for isolation of Mycoplasma gallisepticum collected on applicator swabs. Veterinary Microbiology, 49, 45–57. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00177-8