ABSTRACT

Necrotic enteritis (NE) is one of the most detrimental infectious diseases in the modern poultry industry, characterized by necrosis in the small intestine. It is commonly accepted that NetB-producing C. perfringens type G strains are responsible for the disease. However, based on both macroscopic and histopathological observations, two distinct types of NE are observed. To date, both a haemorrhagic form of NE and the type G-associated non-haemorrhagic disease entity are commonly referred to as NE and the results from scientific research are interchangeably used, without distinguishing between the disease entities. Therefore, we propose to rename the haemorrhagic disease entity to necro-haemorrhagic enteritis.

Background

Clostridium perfringens is widespread throughout the environment and is a member of the normal intestinal microbiota of most mammals and birds (Songer, Citation1996). However, this bacterium is also one of the most common pathogens, causing a wide variety of diseases ranging from histotoxic to enteric infections (Petit et al., Citation1999). C. perfringens itself is not invasive, but causes disease through the production of a wide array of toxins and enzymes. However, no single strain produces the entire toxin repertoire, resulting in considerable variation in toxin profiles and disease syndromes produced by different toxinotypes of this bacterium (Petit et al., Citation1999). One of these diseases is avian necrotic enteritis (NE). The disease mainly affects broilers, but is also seen in turkeys (mostly young meat-type), layer pullets (mostly pullets kept on litter), and some other avian species (Abdul-Aziz & Barnes, Citation2018).

Necrotic enteritis is characterized by necrosis in the small intestine caused by C. Perfringens toxins. Originally, alpha toxin was considered to be the main virulence factor for NE, until the NetB toxin was identified as a crucial factor in disease pathogenesis (Keyburn et al., Citation2008; Keyburn, Bannam et al., Citation2010). Since then, a lot of research has been conducted on the identification of risk factors, pathogenesis, and preventive measures of NetB-associated NE (Mot et al., Citation2014; Moore, Citation2016; Prescott et al., Citation2016; Wade et al., Citation2016, Citation2020; Calik et al., Citation2019). However, despite the overwhelming evidence of the importance of NetB-producing type G strains in NE pathogenesis, this is still a matter of debate in the scientific community, with some research groups describing the isolation of netB-negative type A strains from diseased birds (Yin et al., Citation2017; Li et al., Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2019). Experimental inoculation of birds with these field isolates routinely results in the reproduction of disease, indicating the pathogenic nature of the isolated type A strains. However, re-isolation of the inoculated strain is essential to prove its pathogenicity, but was not reported (Yin et al., Citation2017; Li et al., Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2018). These contradictory findings are also reflected in the literature when gross pathological lesions are described. While there is a consensus on the presence of necrosis of the small intestinal mucosa, co-occurrence of Eimeria infection and the involvement of C. perfringens in NE, there seems to be disagreement on the macroscopic disease presentation, with both a non-haemorrhagic form and a haemorrhagic form being described ().

Table 1. Description of the main characteristics of both haemorrhagic and non-haemorrhagic necrotic enteritis.

Non-haemorrhagic necrotic enteritis

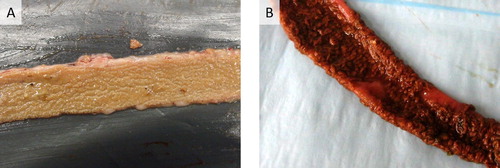

The non-haemorrhagic form of NE is currently the best described and most commonly accepted form of NE in the scientific community. The disease can occur in both a clinical form, which is relatively rare, and a more prevalent subclinical form. The clinical form is characterized by sudden death, often without premonitory clinical signs. The subclinical form does not cause any mortality, although it can cause severe economic losses due to poor bird performance (Van Immerseel et al., Citation2009; Timbermont et al., Citation2011; Kaldhusdal et al., Citation2016). Gross lesions of NE are typically restricted to the small intestine, with the jejunum and ileum being most frequently affected, although lesions can be occasionally observed in the duodenum. Clinical NE is characterized by confluent mucosal necrosis, often covered by a pseudomembrane ((A)) (Long et al., Citation1974; Cooper & Songer, Citation2010; Cooper et al., Citation2010; To et al., Citation2017). In the subclinical form, multifocal ulcers in the form of a depression in the mucosal surface, with discoloured (white-yellow), amorphous material adhering to the mucosal surface are typically observed (Cooper & Songer, Citation2010; Timbermont et al., Citation2011; Smyth, Citation2016; To et al., Citation2017). Infrequently, multifocal necrosis in the liver may be seen (Cooper et al., Citation2013; Kaldhusdal et al., Citation2016; Abdul-Aziz & Barnes, Citation2018). Histopathologically, diffuse and severe coagulative necrosis of the mucosa is observed, starting from the villi tips. A sharp demarcation line composed of inflammatory cells delineates the healthy tissue from the necrotic tips, with abundant Gram-positive rods present in the necrotic debris (Timbermont et al., Citation2009; Cooper & Songer, Citation2010; Cooper et al., Citation2013; To et al., Citation2017). Non-haemorrhagic NE is caused by netB-positive C. perfringens type G strains. Indeed, several studies have compared the pathogenicity of both netB-negative and netB-positive strains isolated from the same outbreak flock or from flocks in the same geographic region in an experimental model for non-haemorrhagic NE, concluding that all netB-positive strains are able to cause non-haemorrhagic NE lesions, whereas netB-negative strains seldomly cause disease (Cooper & Songer, Citation2010; Cooper et al., Citation2010; Keyburn, Yan et al., Citation2010). Moreover, a netB-mutant was unable to produce NE lesions, whereas full virulence was recovered when netB was restored, fulfilling Koch’s postulates (Keyburn et al., Citation2008).

Figure 1. Gross pathology of the small intestine of broilers suffering from severe non-haemorrhagic (A) or haemorrhagic (B) necrotic enteritis. In both cases, extensive necrosis of the mucosal surface is observed. The mucosa is covered by a pseudomembrane which consists of (A) discoloured amorphous material for NetB-associated disease or (B) blood-tinged necrotic material for the disease linked with netB-negative type A strains.

Necro-haemorrhagic enteritis

The haemorrhagic form of NE is characterized by a sudden increase in flock mortality, mostly without premonitory clinical signs. To our knowledge, no subclinical form of this disease entity has been reported to date. On necropsy, gross lesions are primarily found in the small intestine, particularly in the jejunum and ileum. The affected intestinal segment is typically haemorrhagic, with the mesentery often engorged with blood (Dahiya et al., Citation2005; Hargis, Citation2019). This is in contrast to the typical image caused by type G strains, where haemorrhages are rarely observed (Long et al., Citation1974; Cooper et al., Citation2013; Uzal et al., Citation2016; Abdul-Aziz & Barnes, Citation2018). At the level of the mucosa, necro-haemorrhagic disease is characterized by confluent mucosal necrosis, often covered by a pseudomembrane ((B)). In less severe cases, multifocal, brown-grey, necro-haemorrhagic lesions are found. Microscopically, lesions are characterized by necrosis and haemorrhage extending downwards from the tip of the villi (Fletcher et al., Citation2008; Hargis, Citation2019). In less advanced stages, oedema and congestion in the lamina propria are reported, as well as desquamation of epithelial cells at the tips of villi (Dahiya et al., Citation2005), all events that are typically linked to the action of alpha toxin (Morris et al., Citation2012; Goossens et al., Citation2017). Haemorrhagic NE seems to be linked with specific netB-negative C. perfringens type A strains, as the disease can be experimentally reproduced with netB-negative strains isolated from diseased birds (Yin et al., Citation2017; Li et al., Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2018). However, re-isolation of the inoculated C. perfringens strains was not reported, and no studies to identify causative toxins or virulence factors have been conducted so far.

Implications for the current understanding of NE

Currently, the term necrotic enteritis is used to describe both a haemorrhagic and non-haemorrhagic enteric disease in broilers. However, based on both macroscopic and histopathological observations, it is clear that these are two different disease entities, likely caused by two different toxinotypes of C. perfringens. The description of these two syndromes under one common term has led to a great deal of confusion in the scientific literature. NetB was proved to be essential in development of non-haemorrhagic NE lesions; however, the causative toxins for inducing haemorrhagic NE lesions remain to be identified. Especially for early case reports, and research performed before the identification of NetB, it is rather challenging to find out which disease entity was involved, and one can only tentatively identify the actual disease syndrome based on the description of the lesions. Indeed, NE was originally described by Parish in 1961 as a disease characterized by haemorrhagic necrosis of the small intestine, whereas, in 1974, Long and colleagues reported NE as a non-haemorrhagic disease syndrome (Parish, Citation1961; Long et al., Citation1974). This intertwined description of two disease entities creates confusion to the point that review papers refer to the morphological description of early NE lesions by Olkowksi et al. as representative of the non-haemorrhagic type G-induced disease, while field lesions observed by these authors (mesenteric vessels engorged with blood, patchy congestion and haemorrhages on histology) actually point towards the haemorrhagic disease syndrome (Olkowski et al., Citation2006, Citation2008). This indicates that the commonly accepted histopathological events linked to onset of non-haemorrhagic type G-induced NE might not be valid and should be reassessed. Furthermore, the lesions described in haemorrhagic NE show remarkable similarities with bovine necro-haemorrhagic enteritis, a disease caused by C. perfringens type A strains, for which alpha toxin was identified as an essential virulence factor, pointing towards a potential role of alpha toxin in type A-associated NE disease development (see Goossens et al., Citation2017 for a recent review describing the effects of alpha toxin in enteric diseases).

Concluding remarks and future directions

NE in broilers is an enteric disease showing two different macroscopic and histopathological representations. The differences in observed intestinal lesions might be due to the involvement of different toxins. However, current nomenclature makes it difficult to distinguish the disorders from one another. As the disease linked to netB-negative type A strains is characterized by both intestinal necrosis and haemorrhages, we propose to rename this syndrome as avian necro-haemorrhagic enteritis. For unknown reasons, research groups working on either of the two disease entities show somewhat different geographic distributions. Whether this truly reflects a different geography of the NE types, which might be attributed to different breeds of broilers, different housing conditions and litter management, or even other factors, remains to be elucidated. Moreover, it is unknown whether the same factors predispose birds to both types of NE.

In order to fully understand disease pathogenesis and to develop prevention strategies, a clear distinction should be made between both types of NE. Indeed, vaccines based on NetB or other type G-specific proteins will not provide protection against haemorrhagic NE. To rationally develop control strategies for haemorrhagic NE, fulfilment of Koch’s postulates in an experimental model, followed by identification of the essential virulence factors in this disease, will be indispensable. Furthermore, as it is hitherto unclear which early pathological events are caused by either C. perfringens type, there is an urgent need for reassessing the histopathological observations associated with early onset of both syndromes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Billy Hargis for the picture of C. perfringens type A-induced necro-haemorrhagic enteritis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdul-Aziz, T. & Barnes, H.J. (2018). Necrotic enteritis. In Gross Pathology of Avian Diseases: Text and Atlas (pp. 50–52). Madison, WI: Omnipress.

- Calik, A., Omara, I.I., White, M.B., Evans, N.P., Karnezos, T.P. & Dalloul, R.A. (2019). Dietary non-drug feed additive as an alternative for antibiotic growth promoters for broilers during a necrotic enteritis challenge. Microorganisms, 7, 257. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7080257

- Cooper, K.K. & Songer, J.G. (2010). Virulence of Clostridium perfringens in an experimental model of poultry necrotic enteritis. Veterinary Microbiology, 142, 323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.09.065

- Cooper, K.K., Songer, J.G. & Uzal, F.A. (2013). Diagnosing clostridial enteric disease in poultry. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 25, 314–327. doi: 10.1177/1040638713483468

- Cooper, K.K., Theoret, J.R., Stewart, B.A., Trinh, H.T., Glock, R.D. & Songer, J.G. (2010). Virulence for chickens of Clostridium perfringens isolated from poultry and other sources. Anaerobe, 16, 289–292. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.02.006

- Dahiya, J.P., Hoehler, D., Wilkie, D.C., Van Kessel, A.G. & Drew, M.D. (2005). Dietary glycine concentration affects intestinal Clostridium perfringens and lactobacilli populations in broiler chickens. Poultry Science, 84, 1875–1885. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.12.1875

- Fletcher, J.O., Abdul-Aziz, T. & Barnes, H.J. (2008). Alimentary system. In J.O. Fletcher (Ed.), Avian Histopathology (pp. 164–201). Madison, WI: American Association of Avian Pathologists.

- Goossens, E., Valgaeren, B.R., Pardon, B., Haesebrouck, F., Ducatelle, R., Deprez, P.R. & Van Immerseel, F. (2017). Rethinking the role of alpha toxin in Clostridium perfringens-associated enteric diseases: a review on bovine necro-haemorrhagic enteritis. Veterinary Research, 48, 9. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0413-x

- Hargis, B.M. (2019). Overview of necrotic enteritis in poultry.MSD MANUAL Veterinary Manual 11th edition.

- Kaldhusdal, M., Benestad, S.L. & Lovland, A. (2016). Epidemiologic aspects of necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens – disease occurrence and production performance. Avian Pathology, 45, 271–274. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2016.1163521

- Keyburn, A.L., Bannam, T.L., Moore, R.J. & Rood, J.I. (2010). NetB, a pore-forming toxin from necrotic enteritis strains of Clostridium perfringens. Toxins (Basel), 2, 1913–1927. doi: 10.3390/toxins2071913

- Keyburn, A.L., Boyce, J.D., Vaz, P., Bannam, T.L., Ford, M.E., Parker, D., Di Rubbo, A., Rood, J.I. & Moore, R.J. (2008). NetB, a new toxin that is associated with avian necrotic enteritis caused by Clostridium perfringens. PLoS Pathogens, 4, e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040026

- Keyburn, A.L., Yan, X.X., Bannam, T.L., Van Immerseel, F., Rood, J.I. & Moore, R.J. (2010). Association between avian necrotic enteritis and Clostridium perfringens strains expressing NetB toxin. Veterinary Research, 41, 21. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2009069

- Li, Z., Wang, W., Liu, D. & Guo, Y. (2018). Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus on the growth performance and intestinal health of broilers challenged with Clostridium perfringens. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 9, 25. doi: 10.1186/s40104-018-0243-3

- Long, J.R., Pettit, J.R. & Barnum, D.A. (1974). Necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens. II. Pathology and proposed pathogenesis. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research, 38, 467–474.

- Moore, R.J. (2016). Necrotic enteritis predisposing factors in broiler chickens. Avian Pathology, 45, 275–281. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2016.1150587

- Morris, W.E., Dunleavy, M.V., Diodati, J., Berra, G. & Fernandez-Miyakawa, M.E. (2012). Effects of Clostridium perfringens alpha and epsilon toxins in the bovine gut. Anaerobe, 18, 143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.003

- Mot, D., Timbermont, L., Haesebrouck, F., Ducatelle, R. & Van Immerseel, F. (2014). Progress and problems in vaccination against necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens. Avian Pathology, 43, 290–300. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2014.939942

- Olkowski, A.A., Wojnarowicz, C., Chirino-Trejo, M. & Drew, M.D. (2006). Responses of broiler chickens orally challenged with Clostridium perfringens isolated from field cases of necrotic enteritis. Research in Veterinary Science, 81, 99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2005.10.006

- Olkowski, A.A., Wojnarowicz, C., Chirino-Trejo, M., Laarveld, B. & Sawicki, G. (2008). Sub-clinical necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens: novel etiological consideration based on ultra-structural and molecular changes in the intestinal tissue. Research in Veterinary Science, 85, 543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.02.007

- Parish, W.E. (1961). Necrotic enteritis in the fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus). I Histopathology of disease and isolation of a strain of Clostridium Wellchii. Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics, 71, 377–393. doi: 10.1016/S0368-1742(61)80043-X

- Petit, L., Gibert, M. & Popoff, M.R. (1999). Clostridium perfringens: toxinotype and genotype. Trends in Microbiology, 7, 104–110. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01430-9

- Prescott, J.F., Parreira, V.R., Mehdizadeh Gohari, I., Lepp, D. & Gong, J. (2016). The pathogenesis of necrotic enteritis in chickens: what we know and what we need to know: a review. Avian Pathology, 45, 288–294. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2016.1139688

- Smyth, J.A. (2016). Pathology and diagnosis of necrotic enteritis: is it clear-cut? Avian Pathology, 45, 282–287. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2016.1158780

- Songer, J.G. (1996). Clostridial enteric diseases of domestic animals. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 9, 216–234. doi: 10.1128/CMR.9.2.216

- Timbermont, L., Haesebrouck, F., Ducatelle, R. & Van Immerseel, F. (2011). Necrotic enteritis in broilers: an updated review on the pathogenesis. Avian Pathology, 40, 341–347. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2011.590967

- Timbermont, L., Lanckriet, A., Gholamiandehkordi, A.R., Pasmans, F., Martel, A., Haesebrouck, F., Ducatelle, R. & Van Immerseel, F. (2009). Origin of Clostridium perfringens isolates determines the ability to induce necrotic enteritis in broilers. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 32, 503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2008.07.001

- To, H., Suzuki, T., Kawahara, F., Uetsuka, K., Nagai, S. & Nunoya, T. (2017). Experimental induction of necrotic enteritis in chickens by a netB-positive Japanese isolate of Clostridium perfringens. The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 79, 350–358. doi: 10.1292/jvms.16-0500

- Uzal, F.A., Songer, G.J., Prescott, J.F. & Popoff, M.R. (2016). Clostridial Diseases of Animals. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Van Immerseel, F., Rood, J.I., Moore, R.J. & Titball, R.W. (2009). Rethinking our understanding of the pathogenesis of necrotic enteritis in chickens. Trends in Microbiology, 17, 32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.09.005

- Wade, B., Keyburn, A.L., Haring, V., Ford, M., Rood, J.I. & Moore, R.J. (2016). The adherent abilities of Clostridium perfringens strains are critical for the pathogenesis of avian necrotic enteritis. Veterinary Microbiology, 197, 53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.10.028

- Wade, B., Keyburn, A.L., Haring, V., Ford, M., Rood, J.I. & Moore, R.J. (2020). Two putative zinc metalloproteases contribute to the virulence of Clostridium perfringens strains that cause avian necrotic enteritis. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 32, 259–267. doi: 10.1177/1040638719898689

- Wilson, K.M., Chasser, K.M., Duff, A.F., Briggs, W.N., Latorre, J.D., Barta, J.R. & Bielke, L.R. (2018). Comparison of multiple methods for induction of necrotic enteritis in broilers. I. Journal of Applied Poultry Research, 27, 577–589. doi: 10.3382/japr/pfy033

- Yang, W.Y., Lee, Y.J., Lu, H.Y., Branton, S.L., Chou, C.H. & Wang, C. (2019). The netB-positive Clostridium perfringens in the experimental induction of necrotic enteritis with or without predisposing factors. Poultry Science, 98, 5297–5306. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez311

- Yin, D., Du, E., Yuan, J., Gao, J., Wang, Y., Aggrey, S.E. & Guo, Y. (2017). Supplemental thymol and carvacrol increases ileum Lactobacillus population and reduces effect of necrotic enteritis caused by Clostridium perfringens in chickens. Scientific Reports, 7, 7334. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07420-4

- Zhang, B., Gan, L., Shahid, M.S., Lv, Z., Fan, H., Liu, D. & Guo, Y. (2019). In vivo and in vitro protective effect of arginine against intestinal inflammatory response induced by Clostridium perfringens in broiler chickens. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 10, 73. doi: 10.1186/s40104-019-0371-4