ABSTRACT

This conceptual paper focuses on understanding the interactions between art, science, and technology as forms of wide interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary collaboration. There is scarce knowledge about how the wide interdisciplinary interaction between artists, scientists, and technologists can be conceptualized through a shared framework for collaboration. The ecology of collaboration involves a complex set of social structures varying between autonomous individually organized teams and institutional programmes. By using a social ecological approach, integrating social, organizational, and cultural factors, art, science, and technology (AST) collaborations can be characterized by a sequence of antecedent, process, and outcome conditions. These elements are organized to form a conceptual framework for art-science collaborations, elaborating on AST in its relationship to knowledge, aesthetics, interdependence, and experimentalism as antecedent conditions, while outlining the process elements and possible outcomes of the collaborations. The framework can be a vehicle for evaluation and reflection for practitioners, researchers, educators, and policymakers.

Introduction

We are witnessing a growing interest in what the intersection of art, science, and technology can offer. Perhaps the most notable and cited moment in the history of art-science is C.P. Snow’s two-cultures assertion that art, as the domain of literary intellectuals, and science are polarized to the point of mutual incomprehension. While the binary disciplinary positions of art and science may still prevail (particularly in western cultures) on many levels today, experiments on art and technology have emerged as an avant-garde response to such assertions. In 1966, a group of Bell Labs engineers and artists staged ‘9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering’, a series of public performances featuring art and technology, which then became one of the most well-known examples of collaboration between artists, scientists, and engineers. Regardless of the mounting interest and the commitment to build an alternative ‘third culture’ at the intersection of art, science, and technology, theoretical grounding for such a ‘third’ culture remains a challenge as the convergence of these broad disciplines generates the kind of work, knowledge, and synergy in territories unclaimed either by art or science. The process of collaboration through which such unclaimed synergies emerge remains ambiguous, awaiting reinvention with each attempt. Therefore, this paper proposes to analyze the conditions which characterize interactions between artists, scientists, and engineers, contributing to an understanding of the nature of collaborations in this unique intersection. The proposed framework is intended to benefit future collaborations including aspects such as formation, functioning, and evaluation as well as empirical research and policy-level work.

Despite a substantial body of literature and research in organizational studies, public administration, healthcare, sustainability as well as team science and social work, research is notably limited on how a shared framework for collaboration between artists, scientists, and technologists can be conceptualized as a form of interdisciplinary (ID) or transdisciplinary (TD) cultural and creative practice. Several scholarly and empirical works (Jones and Gallison Citation1998; Ede Citation2005; Miller Citation2014; Dieleman Citation2017; Vienni Bapista et al. Citation2019; Cateforis, Duval, and Steiner Citation2019; Schnugg Citation2019; Muller et al. Citation2020; Cardenas, Rodegher, and Hamilton Citation2021; Salter Citation2021) have been instrumental in exploring this niche gap, while another recent initiative is arts and science integrative research (ADIR). ADIR researchers and practitioners have invested in institutionalizing their efforts further through the Alliance for the Arts and Research Universities (a2ru) and encourage future scholarship in developing the field to address key challenges, such as methods and frameworks for working in diverse mediums, evaluation, and recognition, as well as communication across different epistemic cultures of art, science, and technology. In particular, Cardenas, Rodegher, and Hamilton (Citation2021) note that working across disciplinary boundaries of AST, practitioners struggle to find avenues for meaningful evaluation of and reflection on their collaborative processes and disciplinary integration. Moreover, the ecology of collaboration involves a complex set of social structures varying between autonomous individually organized teams and institutional programmes, further substantiating the recent interest in developing shared frameworks for collaboration across diverse epistemic cultures (Stokols et al. Citation2008).

In response, ADIR proposes a framework for collaboration focusing on an ‘institutional’ organization angle with a novel product target (Cardenas, Rodegher, and Hamilton Citation2021). These efforts validate the need and relevance of framework thinking as stipulated in this paper. In relation to these recent efforts, this paper relates to the meso (role of process in project development and execution) and micro (conditions for facilitating creative collaboration) elements of the ADIR Framework. In our proposed framework, we argue that a shared ecology of collaboration should consider process elements as well as the conditions leading to such collaborations, which in our case are the antecedents. Our argument slightly differs from that of micro conditions of the ADIR framework in the sense that antecedent conditions are not necessarily limited to facilitating factors but also include a thread of historical events and trends which potentially bear upon the social and cultural contexts in which AST collaborations develop and function.

The goal of this paper is to offer a pragmatic approach informed by key historical, social, and cultural factors that contribute to the development of the hybrid domain of AST. Subsequently, a framework for collaboration supports such a pragmatic effort by offering a tool for understanding and reflection, and an instrument to experiment when developing and navigating AST collaborations, while offering entry points for further research. This framework is built with the acknowledgment that the practice of AST is immensely diverse, fluid in modalities, and resists taxonomy. A shared conceptual framework is hence proposed which can be relevant for diverse institutional and non-institutional structures as well as purposes ranging from novelty-solution-design to experimental approaches. As such, the proposed framework adopts a social ecological perspective. Social ecology is perceived to offer an overarching viewpoint, to understand complex interrelations between diverse environmental and personal levels integrating social, behavioural organizational, and cultural factors (Gray and Wood Citation1991; Stokols et al. Citation2008).

Furthermore, a framework for collaboration is useful in building systematic knowledge around diverse forms, approaches, co-creating styles, and dialogue across distant epistemic cultures, which is a gap in the field of AST. As Shanken (Citation2005, 415) argues,

[g]iven the increasing dedication of cultural resources to engage artists and designers in science and technology research, there is great need for scholarship that analyses case-studies, identifies best practices and working methods, and proposes models for evaluating both the hybrid products resulting from these endeavours and the contributions of the individuals engaged in them.

The paper introduces the framework in three main sections. The first section provides an ontological framing for AST based on historical, philosophical, and empirical contributions in the field. Section two discusses AST in relation to the three pillars, namely inter and transdisciplinarity, arts-based research, and collaborative art. The final section proposes the framework approach inspired by the key attributes of these three pillars and their contextualization in AST.

1. Art-science-technology: a purposeful description

Before attempting to unveil the social ecology of AST collaborations, it is useful to define what is meant by art-science, as the term applies to a wide range of interactions involving artists and scientists. Ontologically speaking, the multiplicity and diversity of forms and models make it a daunting task to arrive at a commonly agreed definition of what art-science-technology interaction is. Often referred to as ‘art-science’, ‘Sci-art’, or ‘information arts’ (Wilson Citation2002), attempts to define the practice of art-science-technology often stagger at the boundaries of these disciplines. Muller et al. (Citation2020, 231) offer a general framing for art-science as ‘a heterogeneous field of creative research and production, characterized by the collaboration of artists and scientists and by research combining scientific and aesthetic investigation’. The Art-Science Manifesto by Bob Root Bernstein, Todd Siler, Adam Brown, and Kenneth Snelson published in 2011, conceives art-science as a promise for ‘achieving a more complete and universal understanding of things’ with the purpose of creating a more sustainable future (Root-Bernstein et al. Citation2011, 192). AST is perceived to challenge the ways of artistic production, how subject matter functions within a society, and how societally and culturally progressive contemporary art connects with science and technology while driving new agendas for scientific and technological innovation (Wilson Citation2002; Malina Citation2006). Based on this framing, we can argue that there is a shared opinion framing art-science as a practice of creative research and hybrid forms of contemporary aesthetic production whereby the scientific and technological matter and their relationship to society are critically approached.

2. Building bridges: art-science-technology at the intersection of transdisciplinarity, arts-based research, and collaborative art

The interaction between art-science and society has historically been claimed to inhabit a ‘third space’ or a ‘third culture’ (Muller et al. Citation2020). However, the boundary relations between various contributing domains to build such ‘third culture’ remain vague. Therefore, based on the key attributes of the above ontological framing of AST, we argue that three key theoretical pillars contribute to understanding the commonly encountered characteristics of collaborative practice in AST. These three pillars which ultimately inform the AST Collaborations Framework are inter- and transdisciplinarity theory and research, arts-based research, and collaborative art.

First, we focus on the relationship between arts-based research and AST practice. In the literature, it is quite common to encounter the practice of art-science being referred to as ‘research’ and the hybrid persona of the practitioner as ‘researcher’. Nonetheless, Borgdorff (Citation2012) makes a notable distinction between artistic research and art-science collaborations, on the basis that in ‘standard art science’ artists focus on communicating science, being outsiders to scientific practice and therefore these collaborations tend to keep disciplinary silos intact, even accentuating the divide. The ‘standard art-science’ viewpoint, while oversimplifying the AST practice, also raises several questions. First and foremost, acceptance of a ‘standard art-science’ not only does injustice to the field but is ontologically inaccurate. Many scholars and practitioners agree that where the interaction is limited to mere science communication through art, it is considered to be the least interesting form of melding the two fields (Borgdorff Citation2012; Macklin and Macklin Citation2019). Therefore, the ideal type of art-science collaboration referred to by Wilson (Citation2002), Malina (Citation2006), Muller et al. (Citation2020), Schnugg (Citation2019), and Zurr and Catts (Citation2020) occurs when scientific and technological matter informs the art making, building unconventional connections between knowledge, culture, and society. This suggests a strong connection to arts-based research. Borgdorff identifies three main types of artistic inquiry whereby art knowledge is constructed through investigation on, for, and in the arts (Borgdorff Citation2012; Hannula, Suoranta, and Vaden Citation2014). Of particular relevance is ‘Research in the arts’ which is defined as the artistic and creative practice which materializes the notion that the subject and object of research cannot be separated, and consequently that theory and practice cannot be disconnected. Disembodied Cuisine, by Oron Catts, Ionat Zurr, and Guy Ben-Ary, is an example of such interconnectedness. The work offers a critical space where tissue culture research, ethics and human consumption intersect. Such works bear deep theoretical and ethical considerations. In the case of Disembodied Cuisine, artists critically approach positive claims of technological innovations (at the time the false claim of victimless meat) in favour of creating new markets and consumption patterns. In a similar vein, Schnugg (Citation2019) discusses contextualization as a method of understanding the significance of larger questions such as the power of narrative and storytelling, incorporating theoretical undercurrents in building new connections in science and technology.

Second, there seems to be a need to empirically establish a meaningful representation of art-science in the wider ID/TD discourse. Sleigh and Craske (Citation2017) provide a historical analysis of the epistemologies of art-science and argue that changes in the cultural politics of the respective disciplines have led to the emergence of art and science as a ‘transdiscipline’ primarily characterized by the vague term ‘creativity’ (Sleigh and Craske Citation2017). Numerous papers and discussions refer to art-science-technology collaborations as a transdisciplinary (TD) or interdisciplinary (ID) endeavour. In Entangle Physics and the Artistic Imagination, Ariane Koek (Citation2017), the founder of CERN Arts Residency, points out that due to the multiplicity of modalities and the diversity of intentions it almost becomes meaningless to apply a universality through the terms ‘art-science’ or ‘sci-art’. Instead, Koek (Citation2017, 20) argues that ‘(w)hat is perhaps far more important is the notion of transdisciplinarity’, which she defines as ‘that intellectual and creative space where different forms of knowledge and expertise meet across, around and on the boundaries and borders’. While most of these propositions remain on an intellectual level, the EC funded Horizon project SHAPE-ID (https://www.shapeid.eu/), takes a more investigative approach and looks at the conditions for successful integration of arts, humanities, and social sciences into interdisciplinary research (IDR) and transdisciplinary research (TDR). In their final report, authors conclude that the integration of art and humanities in ID/TD discourse remains limited and offers structural guidance for strengthening such integration (Vienni Bapista et al. Citation2019).

Although a somewhat consensual definition for TD would better allow the interpretation of AST as a form of wide ID or TD practice, many scholars agree that such a definition has not yet come to fruition and that systematic empirical studies are scarce beyond individual cases (Vienni Bapista et al. Citation2019; Dieleman Citation2017; Klein Citation1990; Mansilla Citation2006; Wickson, Carew, and Russell Citation2006). Therefore, the two distinct ontological approaches in transdisciplinarity, namely the Zurich and CIRET (Le Centre International de Recherches et Etudes Transdisciplinaires) approaches, collectively offer a more expansive viewpoint to conceive meaningful boundaries for an AST landscape.

Each of the ontological approaches under the umbrella domain of interdisciplinarity studies recognizes that interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary practice focus on creating new and overarching approaches to knowledge creation. Both have emerged from the shifting proximities of theory and practice in the modern theory of knowledge, which foregrounds combining science-oriented knowing through what is measured, with embodied and enacted ways of knowing through an aesthetic and polyphonic language of what is perceived. Within the CIRET approach, pioneered by Basarab Nicolescu, TD is described as the realm between, across, and beyond disciplines, achieved through transgressing the boundary relations between the object and subject in scientific knowledge creation (Nicolescu Citation2010, Citation2014). This view reinforces the imperative of multiple and complementary ways of creating knowledge, with no hierarchical order between them (Dieleman Citation2012). The Zurich approach inspired by Gibbons et al. (Citation1994), underscores transdisciplinarity with a particular focus on solutionism, which they coined as Mode-2 Science, later on further developed as Mode-2 Society. Within this framework, Gibbons et al. (Citation1994) and Nowotny, Scott, and Gibbons (Citation2001) argue that new knowledge is socially contextualized, and therefore built with the goal of devising solutions to complex societal or market-oriented problems (Gibbons et al. Citation1994; Nowotny, Scott, and Gibbons Citation2001; Pohl, Truffer, and Hadorn Citation2017).

Already devised as a form of research, Mode-2 leaves certain epistemological gaps relatively harder to cross between TD and arts-based research. Its focus on solutions to complex societal problems materializes such a gap as many AST collaborations are as concerned with answers as much as they are – and maybe even more so – with foregrounding speculative or established questions and underlying conflicts as opposed to resolving or levelling with them (Calvert and Schyfter Citation2017; Dieleman Citation2017; Vesna, Campbell, and Samsel Citation2019). Consequently, following Nicolescu’s perspective prepares the grounds to develop a framework that can theoretically manifest phenomenological transdisciplinarity (Nicolescu Citation2014). Earlier ontological contributions on distinctions between multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinarity (Klein Citation2017) are also important for establishing such a framework. Klein layers interdisciplinarity by establishing distinct forms of critical, methodological, and instrumental ID. According to Klein (Citation2017), critical ID involves challenging existing knowledge paradigms, and contesting the status quo in its approach to radical, marginalized topics of interest. As a philosophical stance, it creates new transgressive domains, such as the feminist, post-structuralist, and de-disciplined paradigms. In that respect, Klein suggests that it intersects with transcendent, transgressive properties of a particular trendline in transdisciplinary theory, which reinforces the emergence of new theoretical paradigms predominantly through ID in humanities. In this view, AST can arguably be best situated on a spectrum of wide ID and TD rather than being associated exclusively with one or the other. The main reasoning is that there is not enough empirical research to justify a strict association, nor it would be a meaningful resolution given the fluidity prevalent across the domains. Moreover, TD of CIRET heritage shares a kinship to critical ID (Klein Citation2017). Certain practices of TD in arts-based research are also claimed to follow a similar intellectual lineage (Borgdorff Citation2012).

Furthermore, in critical ID the imperative to contest the status quo and accepted norms of disciplinary knowledge and practice strongly resonate with art’s ethical or activist position in the collective art movements (Kester Citation2011). Critical ID can also be said to be analogous to the logic of ontology argument as explained by Born and Barry (Citation2010). Instrumental ID, on the other hand, is more focused on problem-solving foregrounding across disciplinary interaction which connects with the notion of Mode-2 Science, or Mode-2 Society (Klein Citation2017; Nowotny, Scott, and Gibbons Citation2001). This notion refers to new knowledge being socially contextualized, and therefore built with the goal of devising solutions to complex societal or market-oriented problems (Gibbons et al. Citation1994; Nowotny, Scott, and Gibbons Citation2001). The concept can be associated with the logic of innovation by Barry, Born, and Weszkalnys (Citation2008) and later contextualized specifically in art-science (Born and Barry (Citation2010)). Hence the broader use of wide [critical] ID and TD in this paper provides a certain level of flexibility, and the abbreviation ‘ID/TD’ is intended to maintain this flexibility rather than denoting the interchangeability of these concepts.

A final point of the bridging argument focuses on interpreting art-science as a form of collaborative art, which Kester (Citation2011) discusses with vigour dating back to early modernism. Collaboration in an art context, according to Kester, simply denotes ‘working or in conjunction with’ and is rooted in challenging the Kantian notion of the single-authored artwork preformulated by an authoritative creative genius and presented to the public. New collective movements that experimented with novel configurations of artists’ relationships with the public and engaged with social, political, and economic agendas pushed art into alternative zones of cultural production. At the same time, collective and collaborative approaches lead to participatory and dialogical processes (public engagement) and experience-based art digressing from the object-based production. Heavily critiqued in the realm of art and aesthetic theories, socially engaged, activist art championed the flux between ethics and aesthetics on the basis of antagonistic attitude in form, expression, and making of art (Miller Citation2006). Notably, the social interface suggests the employment of novel and emergent methodologies for research, representation, and dissemination eventually creating a permeability between art and other forms of cultural production (Kester Citation2011).

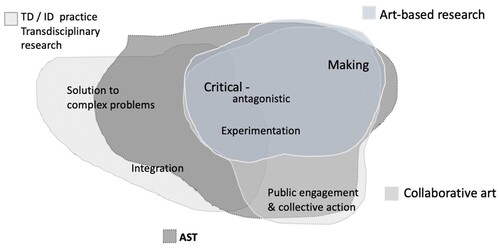

Bridging three distinct theoretical viewpoints, namely ID/TD theory and practice, arts-based research, and collaborative art, forms the foreground characteristics of a conceptual AST space (see ). The interdisciplinary taxonomy (Klein Citation2017) was useful in identifying relevant components of wide ID/TD discourse as a solution to complex problems, integration of knowledge, and transgressing disciplinary paradigms through a critical imperative. Arts-based research invites critical and sometimes antagonistic positions of artistic thinking, experimentation, and art-making as part of research (Borgdorff Citation2012). Finally, collaborative art explicitly introduces the public engagement aspect (Kester Citation2011), which draws parallels with multistakeholder participation in ID/TD practices while the motivations, methods, and involvement might significantly differ.

This landscape allows for the fluid boundaries of interacting concepts to be visible. As such, collaborations in this landscape most likely host participants of diverse backgrounds with possibly conflicting interests, pursuing individual as well as collective goals. Such dynamics can potentially imply limited to no connection between respective disciplinary paradigms eventually cohabiting a space of what Zurr and Catts (Citation2020) humorously call ‘tense-disciplinary’ relations, referring to the acceptance of inherent differences between art and science and at the same time embracing that tension for its potential of liberating knowledge from the silos that it is created in. In this respect, questions around what differentiates the AST collaborations as a wide [critical] ID/TD practice are addressed through the key characteristics of the landscape in .

3. A conceptual framework for collaboration in AST

Collaboration is a concept that is heavily grounded in sociology and organization theories (e.g. Durkheim Citation1933; Hackman Citation1990; McGrath Citation1984). Different definitions of what constitutes a collaboration indicate that this is yet another area of multiplicity. Thomson and Perry (Citation2006) present a definition of collaboration that reflects the dynamics between artists and scientists as opposed to the binary drivers rooted in the political traditions of civic republican collectivism versus classical liberalist individualism. They suggest that collaboration is ‘a process in which autonomous or semi-autonomous actors interact through formal and informal negotiation, jointly creating rules and structures governing their relationships … ; it is a process involving shared norms and mutually beneficial interactions’ (Thomson and Perry Citation2006, 23).

Social science studies on collaboration do not make an explicit contribution to understanding the ID/TD collaboration process involving artists. A few scholars notably engage with the philosophical and art historical aspects of the subject (Davis Citation2005; Dieleman Citation2012; Richmond Citation1984), bridging the dialogue between research, art, and science (Leach Citation2005; Jones and Gallison Citation1998). However, understanding collaboration in a predominantly creative environment, whereby motives such as experimentalism and contesting the status quo are foregrounded, requires looking beyond the collaborations encountered in organizational settings. In that vein, the unique environment of AST collaborations suggests that both experimental, as well as purpose/solution-driven motivations, shape the research and practice of ID/TD through embedding a participatory climate of co-thinking and creating with audiences, stakeholders, citizen scientists, artists, scientists, and technologists.

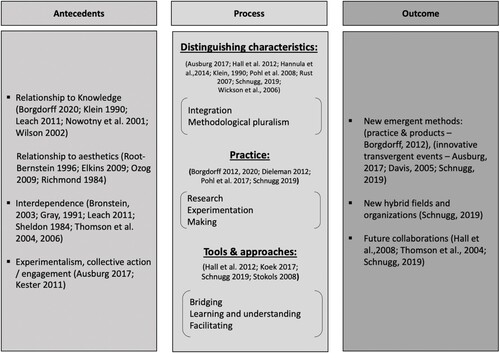

While the background theories of TD and wide ID practices, arts-based research, and collaborative art offer an understanding of key qualities of collaborative practices, a set of qualities is insufficient in interpreting how they collectively translate into a framework for collaboration in AST. Gray and Wood (Citation1991) and Thomson and Perry (Citation2006) make use of three key components that can structure a collaborative framework: (i) Antecedents as the preconditions (individual or group motivations and environmental stimulants) giving rise to collaborations; (ii) Process as the articulation of how collaboration occurs (framing the process by which participants interact to achieve the desired goals); and (iii) Outcomes as the expected results (including conditions for success and specific results associated with the activities) of collaboration.

In an attempt to translate pertinent literature to form a conceptual framework within the antecedent, process, and outcome scheme in AST collaborations, the most commonly cited attributes of wide ID and TD methods and processes, including those informed by empirical case discussions, were organized under Antecedents, Process and Outcomes (see ).

Antecedent conditions in the context of AST are informed by how paradigm shifts in knowledge theories, the culture of science, and art history perspectives collectively shape the formation of an alleged ‘third culture’ and how these dynamics potentially reflect on the interaction between artists, scientists, and engineers. The process of collaboration is a combination of distinguishing characteristics, practices, tools, and approaches commonly mentioned in method-focused works notably in ID/TD research and arts-based research. Outcomes point out the potential and expected results of collaborations.

Following a critical and regenerative reading into background theories and the extant literature on AST, arts-based research, collaborative art, wide ID/TD research, and practice as well as diagnostic discussions on challenges in empirical examples, a conceptual framework for AST collaborations is hereby proposed.

Such a framework aims at sparking new ideas that bridge the commonly agreed theoretical gaps between AST and wide [critical] ID and TD while also providing several pragmatic entry points to further developing ‘framework’ thinking in order to benefit practitioners, researchers, educators, and policymakers in the field.

Antecedents

Discussions on art and science are often based on similarities versus differences primarily in relation to knowledge creation and aesthetics. A considerable volume of the intellectual contribution in this originates from and returns to the heated discussion over C.P. Snow’s Two Cultures debate (Snow Citation1959). The significance of this debate is perhaps not the assertion that epistemologically and ontologically the two disciplines are incontestably different, but that they are entrenched in a ‘gulf of mutual incomprehension’ (Snow Citation1959, 4). While this strongly provocative narrative is perhaps being replaced by his revisited notion of possible dialogue in Two Cultures, a Second Look (Snow Citation1964), the original idea still preoccupies the discourses of art-science critique. Strong advocacy for the separationist view from the perspective of aesthetics is held by Elkins (Citation2009) who considers this discussion to be fundamentally problematic. In his argumentation, there is recognition of mutual fascination between art and science; however, he deems the discussion on aesthetics in arts and science as a ‘drunken conversation’ (Elkins Citation2009, 34) stemming from an insurmountable gap between the two domains with respect to the meaning of aesthetics. The discussion on aesthetics, how it is resolved or addressed in the collaborative process, and whether a notion of shared aesthetic emerges within art-science or whether it belongs in the jurisdiction of art exclusively, remains mostly unexplored.

Proponents of art and science similarity maintain that both disciplines are interested in the construction of truth but employ different approaches (Root-Bernstein Citation1996; Root-Bernstein et al. Citation2011; Jones and Gallison Citation1998). There are transient views that span the two edges of the similarity-difference binary and argue that they are complementary disciplines that function across cognitive rationality and imagination with a certain level of interdependence (Sheldon Citation1984; Thomson and Perry Citation2006). Similarly, Malina offers the ‘network metaphor’, which envisions an ecology of sourcing new ideas, practices, and concepts in response to changing social and cultural structures, thus suggesting a strong connection between what we know, and how we create knowledge in the societal context (Malina Citation2006). Along these lines, Ascott (Citation2000) points out a common thread between art and science with respect to knowledge creation and the subsequent emergence of art-science-technology as a progressive field. The commonality lies in radical new approaches to understanding the nature of cognition, awareness, perception, and consciousness, while the mind is positioned as both the object and subject of art (Ascott Citation2000).

In relation to the aesthetics theory, concepts like unity, simplicity, creative interpretation, and experience find expressions both through science and art. Based on numerous quotes and examples from scientific discoveries, Root-Bernstein (Citation1996) exemplifies how scientific formulations are built on the premise of ‘aesthetic’ considerations, which have an impact on generating the types of mental pictures that enable new discoveries (Root-Bernstein Citation1996; Schnugg Citation2019). In a similar vein, the inherent connection between aesthetic considerations and form introduces new dimensions to be integrated into the wide ID/TD process of creative research and practice (Cardenas, Rodegher, and Hamilton Citation2021). Richmond (Citation1984) makes use of cognitive monism and aesthetic monism in building his assertion that art and science are interdependent faculties of knowledge and meaning-making, each instrumentalizing different degrees and uses of epistemic and ontological premises.

Interdependence, therefore, is included as a relevant antecedent condition in the context of AST, stemming from theories of cross-sectoral collaboration in public administration (Bryson, Crosby, and Stone Citation2015; Thomson and Perry Citation2006) as well as interdisciplinary collaboration (Bronstein Citation2003). In a rhizomatic fashion, critical theory and cultural studies influence the paradigm shifts in contemporary artistic, scientific, and technological knowledge making. Cultural theory contests conventional notions of culture and the divide between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture in understanding sciences, arts, and humanities. Critical theory in Horkheimer’s ([Citation1972] Citation2002) elucidation is a gamut of critical attitude and critical thinking (Horkheimer [Citation1972] Citation2002). Such a premise is the foundation for collapsing the barriers between wide apart disciplines such as art, technology, and science, pushing new knowledge and meaning-making to become an interdependent act (Wilson Citation2002). Interdependence is also a foregrounded notion with regard to the relationship between technology and culture, societal development, and creative production (Leach Citation2005).

Despite the acknowledgment of complementarity between art, science, and technology in knowledge creation, empirical research suggests that an inherent disciplinary divide at times prevails in the process of collaboration, demarking the ideas of subjectivity and aesthetic value in art and objectivity and utility in science (Leach Citation2011). Leach implicitly weaves the concept of integration through the interdependence of subjectivity and objectivity. Similarly, technology disrupts the divide and invites new boundary relations between knowledge and research practices as well as offering new types of creative production (Leach Citation2005). As a combined change effect, he develops argumentations for new knowledge creation paradigms fuelled by technology and integrative research trends.

A final point on antecedent conditions for art-science collaborations relates to experimentalism. Several factors contribute to ‘experimentalist’ motivations in AST collaborations. First and foremost is our undeniable relationship with technology. Artists have long been fascinated by and making use of technology as a medium. The cognitive, social, and cultural interplay between technology and society has fuelled the experimentation around new aesthetics and a symbolic language in art, which at the same time embodies a bridging role for art between science and society (Ozog Citation2009; Leach Citation2005; Cateforis, Duval, and Steiner Citation2019). Experimentalism defines the very core idea behind AST collaborative schemes historically spearheaded by Experiments in Arts and Technology (E.A.T) and LACMA and later on followed by renowned programmes such as CERN Arts (Koek Citation2017), NTIF (Leach Citation2005), and UK Welcome Collection (Arnold Citation2017). These programmes advocate the value of experimentation and release the pressure of rigid pre-defined solutions in favour of investigating possibilities. The antecedent conditions shape the ‘third space’ where the effective process of collaboration takes place.

Process

A collaborative process between artists, scientists, and engineers involves working on a joint project or a relevant research question (Schnugg Citation2019). Thomson and Perry (Citation2006, 23) offer a synthesized description of a collaboration process as a course

in which autonomous actors interact through formal and informal negotiation, jointly creating rules and structures governing their relationships and ways to act or decide on the issues that brought them together; it is a process involving shared norms and mutually beneficial interactions.

Distinguishing characteristics. Integration is considered to be a key attribute (Pohl et al. Citation2021) that differentiates ID/TD practice from other forms of collaboration encountered in the organization and social work literature (Klein Citation1990; Pohl et al. Citation2021). Pohl et al. (Citation2021) define the concept as an open-ended learning process whereby elements that have been disparate are connected and the outcomes of such relationships are not pre-determined. Integration seeks to establish a balance between retaining plurality and attaining consensus across diverse thought styles, knowledge, ideas, or practices. In the context of collaborative research undertaken by artists, scientists, and technologists, integration is characterized by a multi-level convergence of diverse epistemological and ontological perspectives, the unity of subject and object in an investigation, and a synthesis of theory and practice mostly through arts-based research. Integration is also discussed as the incorporation of non-propositional, experiential knowledge as part of a methodology in making a claim to new knowledge (Ausburg Citation2017; Rust Citation2007; Wickson, Carew, and Russell Citation2006).

The concept of integration, however, is vaguely recognized in art-science collaborations and much remains to explore. Nevertheless, integration remains a relevant issue not only at the cognitive level but also pertaining to social and organizational dynamics, such as disciplinary exchanges and rethinking disciplinary identities (Darbellay et al. Citation2014). Methodological pluralism appears to be a common ground between ID/TD research and artistic research, meaning that there is no single, restricted method or approach employed in artistic inquiry (Borgdorff Citation2012; Hannula, Suoranta, and Vaden Citation2014). Engaging the meta-knowledge domains of art, science, and technology along with diverse participant groups inherently suggests the use of multiple epistemic traditions. Art-science scholars consistently argue that expecting to see a systematic methodology is not only unrealistic but also counterintuitive to the diversity and multiplicity of the field.

Practice. As practice and phenomenology gain equal footing with theory in shaping the context of discovery – particularly in cognitive science, Science and Technology Studies (STS), and cultural studies – contextualized, embodied, and enacted forms of cognition have been integrated into the ways new knowledge is created (Borgdorff, Peters, and Pinch Citation2020; Gibbs Citation2014). In line with this proposition, arts-based research introduces an important element to the practice: the creative process of making or producing the work. The making of art embodies cultural, social, contextual, and aesthetic concerns and is strongly linked to the research question irrespective of whether the intended output is a solution, a deeper understanding, a provocation, an engagement, or a combination of these ends. Therefore, what appears to differentiate arts-based research from wide ID or TD research is the element of the artwork which, in the context of AST, involves the creative and cultural process of embedding the scientific and technological elements in concept and knowledge creation. A way to integrate the creation of the artwork in the wide ID or TD practice in the AST context can be informed by the process in arts-based research, which is an intertwinement of research, experimentation, and making (Borgdorff Citation2012).

Hannula, Suoranta, and Vaden (Citation2014) characterize the doing of arts-based research, which they describe as ‘inside-in’. There is a strong presence of subject-object interaction (alternating between insider and outsider positions), it is mostly practice-based, contextual, self-critical, and interwoven into the creative process of art making. Dieleman (Citation2017) discusses the notion of ‘spaces of experimentation and imagination’. Experimentation and imagination, he argues, encourage an inquiry into alternative realities through diverse and simultaneous ways of exchanging experiences, metaphoric representation, and introspection. At the same time, these exchanges create surprise and perhaps confusion, ultimately, inviting collaborators to challenge and transcend the existing disciplinary boundaries. Experimentation does not necessarily function to solve problems but encourages engagement with the research question (Dieleman Citation2017).

Making or producing the actual work is strongly intertwined with the research process, and that is claimed to be the difference between arts-based research and other forms of applied knowledge production (Borgdorff Citation2012). Experimentation and making can be intertwined, and, unlike hypothesis-driven scientific research, an AST collaboration can start with anticipation of what may possibly lie ahead (Rust Citation2007). Therefore, experimentation is a vital part of the creative making process. Tools such as artistic interventions, reflection, and play, are employed to complement the subject-object interaction and participative quality of artistic research (Borgdorff, Peters, and Pinch Citation2020; Borgdorff Citation2012). These practices may lead to interesting tensions between artists, engineers, and scientists, as they potentially interrupt the systematic, designed processes of ID/TD research (Repko, Newell, and Szostak Citation2012). However, the extent to which the act of making, or creative production is considered to be a part of the collaboration between artists and scientists remains uncharted territory.

Tools and approaches. The distinguishing process characteristics denoted by integration and methodological pluralism most logically translate into mechanisms pertinent to communication, meaning-making, and social weaving. Therefore, the proposed tools and approaches are focused on these aspects and organized into three themes: (i) bridging, (ii) learning and understanding, and (iii) facilitating (Hall et al. Citation2012; Schnugg Citation2019; Stokols et al. Citation2008).

Bridging involves the creation of a shared language and common meanings, the identification of common goals and research questions, the alignment of expectations, as well as a collective design of methods. In addition, developing a common problem space through the use of diverse tools such as shared mental models, cognitive artifacts, and concept mapping appears to be a critical practice in ID/TD collaborations (Hall et al. Citation2012; Stokols et al. Citation2008). However, there is not enough empirical evidence to argue to what extent the creation of a shared language, common meanings, and goals are strategies adopted in AST collaborations due to their unique qualities in the practice of research, experimentation, and making.

The practices which focus on ‘learning and understanding’ involve orienting into and developing a good level of understanding of the disciplinary fields involved in collaboration, including their disciplinary cultures, perspectives, and values. This also asks for engaging critically with the methodological traditions and knowledge cultures of the participating fields. Hall et al. (Citation2012) in their discussion of team science, refer to this aspect as developing critical awareness, by which they mean reaching an understanding of fundamental as well as methodological strengths and limitations of collaborators’ own and other fields. In art science, disciplinary learning entails experiential involvement with scientific, technological, and artistic materials and methods (Hall et al. Citation2012; Koek Citation2017; Schnugg Citation2019).

The approaches that relate to ‘facilitating’ the collaborative environment focus on a mix of values, motivations, and interpersonal and intrapersonal agency. The most common cultural norm that has a facilitating influence is the acknowledgement that collaborators are experts in their field and that all members meaningfully contribute to the collaborative environment. Creating a psychologically safe space is argued to be critical for encouraging collaborators’ independent exchange of ideas and thoughts and for flattening potential disciplinary hierarchies. Social cohesiveness and familiarity are argued to relate to productivity; hence, these aspects are considered among the facilitating factors (Anzures and Marques Citation2022; Hall et al. Citation2012; Stokols et al. Citation2008).

Outcomes

The Outcomes component is the least developed across studies on collaboration. Gray and Wood (Citation1991) offers a theory-practice mapping with respect to what constitutes an outcome in collaboration; in so doing, the author confirms that the perception and conceptualization of outcomes are relatively more diverse than the formulation of antecedents and process conditions. Some approaches to outcomes focus on the process achievements vis-a-vis the goals, while others offer a specific system for classification and measurement. Alternatively, outcomes are also defined as a projection or mere guesswork on the spill-over effects of collaboration (Gray and Wood Citation1991). Hall et al. (Citation2012) briefly discuss near, intermediate, and long-term outcomes of TD collaborations, such as new future collaborations, and innovative or new applied lines of research (Hall et al. Citation2012).

With respect to outcomes, many scholars place an emphasis on the value perspective and attempt to justify the perceived value in art-science. For example, Schnugg (Citation2019) approaches value from an organizational, social, and cultural perspective. From an arts-based research point of view, new methods and tools emerge, foregrounding the innovative and creative capabilities of AST collaborations (Borgdorff Citation2012; Davis Citation2005). Koek (Citation2017) emphasizes the instrumentality and impact of creativity and imagination, while Zurr and Catts (Citation2020) foreground the critical angle and adversarial role of arts in advancing science and technology.

The organization of antecedent, process, and outcome conditions allows us to look into the ‘doing of collaboration’ and to open the black box of content and structural elements of AST. In doing so, we are also encouraged to think about and investigate the relationship between these elements situated in specific AST contexts, and validate their relative significance in specific practices in order to build a more comprehensive understanding of their social ecology. This framework should not be seen as an attempt to iron out the tensions, often conflicting epistemic heritage, messiness, and conflict-prone dynamics of AST but rather to draw attention to how these elements interact to enable negotiations and meaningful outcomes in the possible absence of a consensus.

4. Conclusion

The AST Collaborations Framework is an attempt to construct a disciplinary inclusive approach for understanding wide ID/TD interactions between art, science, and technology in a collaborative setting. Key contributions of the AST Collaborative Framework pertain to developing an understanding of collaboration elements and associated social processes, and providing a starting point for building overarching yet flexible systematic knowledge while strengthening the position of art more elaborately within the ID/TD discourse.

The quality and process of interaction and dialogue between artists, scientists, and engineers have long been a subject of interest. However, when it comes to decoding the ‘doing’ of collaboration between artists and scientists, systematic empirical studies are scarce. The current paper proposes to address this observed gap by moving beyond the narrative of what works and what does not in methodology discussions of AST collaborations.

A framework for collaboration is useful in building systematic knowledge around diverse forms, approaches, and styles for co-creating, documenting, evaluating, and building dialogue across distant epistemic cultures. In parallel, there is a growing interest in making the social process of AST collaborations a part of the creative content for purposes of audience/participant engagement as well as evaluation material (Vesna Citation2001; Leach Citation2005; Verena and Kaiser Citation2021). Therefore, the current paper also contributes by providing entry points to social processes and inviting future empirical research into investigating the implications of the framework elements discussed herein.

In this discussion, ID/TD theories and methodologies offer the ontological and epistemological grounds for synthesizing interactions across disciplines through blending, linking, and borrowing methods and paradigms, while maintaining a certain ‘disciplinary’ reference in the production of the target output. Arts-based research theories underscore the significance and iterative weaving of ‘making’ or ‘performing’ as part of research, therefore bridging art and ID/TD theories in the context of AST. Critical, often antagonistic, and activist motives introduced through collaborative art encourage thinking through collaborative processes as spaces of potentially conflicting interests, value systems as well as shared goals.

Henceforth, the proposed AST Collaborations Framework is intended to provide an alternative approach, organizing these interacting elements in the specific context of art-science through the loose structural approach of antecedents, process, and outcomes conditions in which collaborations function.

Antecedents offer diverse and often connected concepts, which give direction to AST interactions in the collaboration process. Through the inclusion of artistic research and creation, AST collaborations bring aesthetics and knowledge closer in the discourse of ID/TD research and practice. Experimentation in AST enriches the scientific process by juxtaposing the need for certainty in science with creativity stemming from uncertainty and ambiguity in art. Interdependence calls for new paradigmatic schemes in the collaborative process whereby subject/object, theory/practice, embodied/scientific, and subjective/objective binaries can meaningfully co-exist. Such qualities connect to Process components of methodological pluralism, encouraging a deeper understanding of proposed tools and approaches to bridging, learning, and understanding, and facilitating. In its acknowledgment of these precedence conditions, the Framework for AST Collaborations liberates prescribed methodological designs for the ID/TD process and encourages a toolkit mentality as suggested in the Practice component of the collaborative process.

The concept of integration in relation to antecedent conditions is a cross-cutting topic. The AST Collaborations Framework is intended to trigger a deeper investigation into how integration unfolds on a spectrum of wide ID/TD research and creative making across the diverse AST landscape. This landscape currently holds a spectrum of experimental collaborative programmes, as well as specific project-driven initiatives such as critical, socially engaged art, and functional designs (solutions). Integration in the context of these diverse modalities should be investigated more closely on the levels of research, experimentation, and making. A final point on integration pertains to social and organizational dynamics such as disciplinary exchanges and rethinking disciplinary identities (Darbellay et al. Citation2014).

Future implications for research are ample. Immediate potential lies in investigating constructs of integration in AST. For example, future research might shed more light on understanding how bridging, learning, understanding, and facilitating can relate to social dynamics and disciplinary identities. Such efforts can potentially have implications for transcending boundaries towards the reconfiguration of ‘hybrid/third spaces’, generating new ontologies informing relevant measures of value, utility, and meaning in engaging with AST collaborations.

Through a combined discussion of the AST landscape and the AST Collaborations Framework, we build a case for a spectrum use of [critical] wide ID/TD in the context of AST collaborations. Further empirical research can potentially address questions around how the framework constructs form and function in relation to different types of AST collaborations. The field can benefit from a systematic understanding of the relationships between antecedent, process, and outcome elements and their implications on collaboration effectiveness. The AST Collaborations Framework can be further developed for field use in different settings such as experimental, solution design, socially engaged art, and/or critical co-creation. Moreover, differences and similarities between self-organizing autonomous teams and institutional collaborative efforts in relation to the framework can provide rich insights. The resulting call for action is to encourage ID/TD research into investigating methodologies, evaluation principles, and process structures specifically addressing critical creative making and knowledge co-creation in AST while maintaining a shared social ecological viewpoint.

Currently, progressive collaborations are happening in which the boundaries of aesthetics, scientific knowledge, and technological innovation are crossed, delivering unfamiliar perspectives. The present article offers a reflection on these collaborations, establishing a framework for the field of AST which can be used for further (empirical) studies, as a tool for understanding and reflection, as an instrument to guide development and implementation as well as a roadmap which can be taken into policy discussions. This paper is therefore a step towards contributing to a new narrative reflecting on the common space of experience between artists, scientists, and engineers; a narrative that needs to emerge out of empirical studies to depict what Vesna (Citation2001, 124) describes as ‘bridging and synthesising many worlds while composing “something else” becomes the art’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Zeynep Birsel

Zeynep Birsel’s research focuses on inter/transdisciplinary collaborations in cultural and creative industries. She investigates boundary crossing works and co-working practices involving art, science, and technology.

Lenia Marques

Lenia Marques’ research focuses on the development of the cultural and creative industries and their relationships with other fields, such as tourism and events. Her interest is particularly in cities and the development of cultural and creative policies, and the relationship of creativity and urban processes.

Ellen Loots

Ellen Loots is specialized in arts management, cultural organizations, and creative entrepreneurship, and has a special interest in the motivations and behaviours of individuals and organizations in the cultural and creative industries. Social challenges such as justice, community, and sustainability influence many of her choices in research and teaching.

References

- Anzures, F. A. S., and L. Marques. 2022. “The LED Lamp Metaphor: Knowledge and the Creative Process in new Media art.” Poetics, 92: 101644. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2022.101644.

- Arnold, K. 2017. “A Very Public Affair: Art Meets Science.” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 42 (4): 331–344.

- Ascott, R. 2000. Art, Technology, Consciousness mind@large. Bristol, UK: Intellect Books Ltd.

- Ausburg, T. 2017. “Interdisciplinary Arts.” In The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, edited by Robert Froedman, Julie Thompson Klein, and Roberto C. S. Pacheco, 131–143. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Barry, A., G. Born, and G. Weszkalnys. 2008. “Logics of Interdisciplinarity.” Economy and Society 37 (1): 20–49.

- Borgdorff, H. 2012. The Conflict of the Faculties – Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia. The Netherlands: Leiden University Press.

- Borgdorff, H., P. Peters, and T. Pinch. 2020. Dialogues between Artistic Research and Science and Technology Studies. New York: Routledge.

- Born, G., and A. Barry. 2010. “ART-SCIENCE from Public Understanding to Public Experiment.” Journal of Cultural Economy 3 (1): 103–119.

- Bronstein, L. 2003. “A Model for Interdisciplinary Collaboration.” Social Work 48 (3): 297–306.

- Bryson, J. M., B. C. Crosby, and M. Stone. 2015. “Designing and Implementing Cross-Sector Collaborations: Needed and Challenging.” Public Administration Review 75 (5): 647–663.

- Calvert, J., and P. Schyfter. 2017. “What can Science and Technology Studies Learn from Art and Design? Reflections on ‘Synthetic Aesthetics.’” Social Studies of Science 47 (2): 195–215.

- Cardenas, E., S. Rodegher, and K. Hamilton. 2021. “The Future of Arts Integrative Work; Creating New Avenues for Advancing and Expanding the Field.” In Routledge Handbook of Art, Science and Technology Studies, edited by Megan K. Halpern, Dehlia Hannah, and Kathryn de Ridder-Vignone, 273–395. New York: Routledge.

- Cateforis, D., S. Duval, and S. Steiner. 2019. Hybrid Practices Art in Collaboration with Science and Technology in the Long 1960s. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Darbellay, F., Z. Moody, A. Sedooka, and G. Steffen. 2014. “Interdisciplinary Research Boosted by Serendipity.” Creativity Research Journal 26 (1): 1–10.

- Davis A. 2005. Transvergence in Art History. Switch, 20, CADRE Laboratory for New Media, San Jose State University, CA. Accessed January 7, 2021. http://www.ekac.org/transvergence.html

- De Wachter, E. M. 2017. Co-Art: Artists on Creative Collaboration. London: Phaidon Press Limited.

- Dieleman, H. 2012. “Transdisciplinary Artful Doing in Spaces of Experimentation and Imagination.” Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science 3: 44–57.

- Dieleman, H. 2017. “Transdisciplinary Hermeneutics: A Symbiosis of Science, Art, Philosophy, Reflective Practice, and Subjective Experience.” Issues In Interdisciplinary Studies 35: 170–199.

- Durkheim, E. 1933. The Division of Labor in Society. Translated from the French by George Simpson. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press.

- Ede, S. 2005. Art and Science. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.

- Elkins, J. 2009. “Aesthetics and the Two Cultures: Why Art and Science Should Be Allowed to Go their Separate Ways.” In Rediscovering Aesthetics, Transdisciplinary Voices from Art History, Philosophy, and Art Practice, edited by T. O’Connor, F. Hallsall, and J. Jansen, 34–50. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gibbons, M., C. Limoges, H. Nowotny, S. Schwartzman, P. Scott, and M. Trow. 1994. The New Production of Knowledge. London: Sage.

- Gibbs, L. 2014. “Arts-Science Collaboration, Embodied Research Methods, and the Politics of Belonging: ‘SiteWorks’ and the Shoalhaven River, Australia.” Cultural Geographies 21 (2): 207–227.

- Gray, B., and D. J. Wood. 1991. “Collaborative Alliances: Moving from Practice to Theory.” Journal of Behavioral Science 27 (1): 3–22.

- Hackman, J. R. 1990. Groups that Work (and Those That Don't). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Hall, K. L., A. L. Vogel, B. Stipelman, D. Stokols, G. Morgan, and S. Gehlert. 2012. “A Four-Phase Model of Transdisciplinary Team-Based Research: Goals, Team Processes, and Strategies.” TBM 2: 415–430.

- Hannula, M., J. Suoranta, and T. Vaden. 2014. Artistic Research Methodology, Narrative, Power and the Public, e-book, www.peterlang.com.

- Horkheimer, M. (1972) 2002. Critical Theory Selected Essays. New York: The Continuum. (Horkheimer, Max, 1895–1973. Critical Theory. Translation of: Kritische Theorie. “Essays from the Zeitschrift fur Soaalforschung” – Pref. Reprint, Originally published, New York: Seabury Press).

- Jones, C. A., and P. Gallison. 1998. Picturing Science Producing Art. New York: Routlage.

- Kester, G. H. 2011. The One and the Many, Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Klein, J. T. 1990. Interdisciplinarity: History, Theory and Practice. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press.

- Klein, J. T. 2017. “Typologies of Interdisciplinarity: The Boundary Work of Definition.” In The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity. 2nd ed., edited by R. Froedman, J. T. Klein, and C. S. Pacheco, 21–34. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198733522.013.42 (e-book).

- Koek, A. 2017. “In/Visible: The Inside Story of the Making of Arts at CERN.” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 42 (4): 345–358.

- Leach, J. 2005. “‘Being in Between’: Art-Science Collaborations and a Technological Culture, Social Analysis.” The International Journal of Anthropology 49 (1): 141–160.

- Leach, J. 2011. “The Self of the Scientist, Material for the Artist – Emergent Distinctions in an Interdisciplinary Collaboration.” Social Analysis 55 (3): 143–163.

- Macklin, J. E., and M. Macklin. 2019. “Art-Geoscience Encounters and Entanglements in the Watery Realm.” Journal of Maps 15 (3): 9–18.

- Malina, R. F. 2006. “Welcoming Uncertainty: The Strong Case for Coupling the Contemporary Arts to Science and Technology.” In Artists in Labs: Process of Inquiry, edited by Jill Scott, 15–23. Wien: Springer-Verlag.

- Mansilla, V. B. 2006. “Interdisciplinary Work at The Frontier: An Empirical Examination of Expert Interdisciplinary Epistemologies.” Issues in Integrative Studies 24: 1–31.

- McGrath, J. E. 1984. Groups: Interaction and Performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Miller, J. 2006. “Activism vs. Antagonism: Socially Engaged Art from Bourriaud to Bishop and Beyond.” FIELD Journal of Socially Engaged Arts Criticism 3: 165–183.

- Miller, A. 2014. Colliding Worlds How Cutting-Edge Science is Redefining Contemporary Art. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Muller, L., J. Bennett, L. Froggett, and V. Bartlett. 2020. “Emergent Knowledge in the Third Space of Art-Science.” Leonardo 53 (3): 321–326.

- Nicolescu, B. 2010. “Methodology of Transdisciplinarity – Levels of Reality, Logic of the Included Middle and Complexity.” Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science 1 (1): 19–38.

- Nicolescu, B. 2014. “Methodology of Transdisciplinarity.” World Futures 70 (3-4): 186–199. doi:10.1080/02604027.2014.934631.

- Nowotny, H., P. Scott, and M. Gibbons. 2001. Rethinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Ozog, M. 2009. “Art Investigating Science: Critical Art as a Meta-discourse of Science, Cognition and Creativity.” Digital Arts and Culture. Arts Computation Engineering, UC Irvine. Accessed September 2, 2021. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4k9509qj.

- Pohl, C., J. T. Klein, S. Hoffmann, C. Mitchell, and D. Fam. 2021. “Conceptualising Transdisciplinary Integration as a Multidimensional Interactive Process.” Environmental Science and Policy 118: 18–26.

- Pohl C, B. Truffer, and G.H. Hadorn. 2017. Addressing Wicked Problems Through Transdisciplinary Research. In: The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity, 2nd ed., edited by Robert Frodeman, J. T. Klein, and R. S. C. Pacheco, 319–331. Oxford University Press.

- Repko, A. F., N. H. Newell, and R. Szostak. 2012. Case Studies in Interdisciplinary Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Richmond, S. 1984. “The Interaction of Art and Science.” Leonardo 17 (2): 81–86.

- Root-Bernstein, R. S. 1996. “The Sciences and Arts Share a Common Creative Aesthetic.” In The Elusive Synthesis: Aesthetics and Science, edited by Alfred I. Tauber, 49–82 . Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, vol. 182. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-1786-6_3

- Root-Bernstein, R. S., T. Siler, A. Brown, and K. Snelson. 2011. “ArtScience: Integrative Collaboration to Create a Sustainable Future.” Leonardo 44 (3): 192. doi:10.1162/LEON_e_00161.

- Rust, C. 2007. “Unstated Contributions – How Artistic Inquiry Can Inform Interdisciplinary Research.” International Journal of Design 1 (3): 69–76.

- Salter, C. 2021. “The art-Science Complex.” In Routledge Handbook of Art, Science and Technology Studies, edited by Megan K. Halpern, Dehlia Hannah, and Kathryn de Ridder-Vignone, 273–395. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Schnugg, C. 2019. Creating Art Science Collaboration. Switzerland: Cham: Palgrave MacMillen.

- Shanken, E. A. 2005. “Artists in Industry and the Academy: Interdisciplinary Research Collaborations.” Leonardo 38 (4): 278–279.

- Sheldon, R. 1984. “The Interaction of Art and Science.” Leonardo 17 (2): 81–86.

- Sleigh, C., and S. Craske. 2017. “Art and Science in the UK: A Brief History and Critical Reflection.” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 42 (4): 313–330.

- Snow, C. P. 1959. The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. The Rede Lecture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Snow, C. P. 1964. The Two Cultures and a Second Look: An Expanded Version of the Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stokols, D., S. Misra, R. P. Moser, K. L. Hall, and B. K. Taylor. 2008. “The Ecology of Team Science Understanding Contextual Influences on Transdisciplinary Collaboration.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35 (2S): S96–S115.

- Thomson, A. M., and J. L. Perry. 2006. “Collaboration Processes: Inside the Black Box.” Public Administration Review. Special Issue, 66: 20–32.

- Thomson, A. M., J. L. Perry, and T. K. Miller. 2009. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Collaboration.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19 (1): 23–56.

- Verena, H., and M. L. Kaiser. 2021. “An Alphabetical Order of Accusations, Beginnings and Groceries.” A Report on connecting, writing and improvisation. https://jegensentevens.nl/2021/11/an-alphabetic-order-of-accusations-beginnings-and-groceries-on-connecting-writing-and-improvisation/?fbclid=IwAR3YK10qHXz6EutqYtuuEj8dRwAIg3h52Zn9w-jXd4YU3KorXoZjGI6xcFU.

- Vesna, V. 2001. “Towards a Third Culture: Being in Between.” Leonardo 34 (2): 121–125.

- Vesna, V., B. Campbell, and F. Samsel. 2019. “Victoria Vesna: Inviting Meaningful Organic Art-Science Collaboration.” IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 39 (4): 8–13.

- Vienni Bapista, B., M. Maryl, P. Wciślik, I. Fletcher, A. Buchner, D. Wallace, and C. Pohl. 2019. SHAPE-ID: Shaping Interdisciplinary Practices in Europe. Preliminary Report of Literature Review on Understandings of Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Research. www.shapeID.eu (https://www.shapeid.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/SHAPE-ID-822705-D2.1-Preliminary-Report-on-Literature-Review.pdf).

- Wickson, F., A. L. Carew, and A. W. Russell. 2006. “Transdisciplinary Research: Characteristics, Quandaries and Quality.” Futures 38: 1046–1059.

- Wilson, S. 2002. Information Arts, Intersections of Art, Science, and Technology. London: The MIT Press.

- Zurr, I., and O. Catts. 2020. “Tense-disciplinary Collaborations with Frontier Technologies.” Non-Traditional Research Outcomes (NTRO). Accessed September 2, 2021. https://nitro.edu.au/articles/2020/8/31/tense-disciplinary-collaborations-with-frontier-technologies.