Abstract

The coordination of activity across sites and spaces of production and consumption is a key concern for economic analysis. Joining a revival in the application of convention theory to agro-food scholarship, this paper considers complementary insights – related principally to ‘the economy of qualities’ – that animate different aspects of e/valuation, competition and alignment. These understandings are extended by more thoroughly acknowledging contemporary developments in consumption scholarship. The arguments are advanced through a case study of the orange juice market, linking its current high-carbon trajectory to the commercial and cultural significance of freshness. The analysis offers new insights into distributed processes of qualification as well as the mechanisms through which conventions are assembled and sustained. Finally, a more integrated approach to food production and consumption is outlined.

Introduction

The coordination of activity across sites and spaces of production and consumption is a key concern for economic analysis, so too are the mechanisms of valuation and evaluation that help in achieving alignment. While this can be observed across multiple domains, it is pronounced in current discussions of food security and sustainability.Footnote1 There is an emerging consensus – albeit with some scepticism as to the transformative potential of ‘holistic’ methods for quantifying value (Freidberg, Citation2014) – that ‘integrated’ and ‘whole chain’ approaches are needed (e.g. Horton et al., Citation2017; Ingram, Citation2011; Marsden & Morley, Citation2014). Similarly, contemporary social scientific approaches to the moral economies of food suggest greater attention should be paid to consumption and consumers (Glaze & Richardson, Citation2017; Wheeler, Citation2018). This paper engages with these concerns by revisiting two foundational trends in agro-food scholarship – specifically the application of convention theory (see Ponte, Citation2016) and the incorporation of insights from contemporary consumption scholarship (see Goodman, Citation2002). In doing so, it argues that a focus on qualities and conventions permits the development of integrative perspectives on production and consumption that in turn contribute to a reframing of debates around the environmental sustainability of food systems.

Our starting point is an interest in how conventions facilitate the alignment of disparate economic actors (producers and consumers). It is logical, then, to turn to convention theory (Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006[Citation1991]), which has been particularly influential in the study of food and agriculture. It was mobilized extensively between the late 1990s and mid-2000s (see Murdoch & Miele, Citation2004; Wilkinson, Citation1997) to examine ‘alternative food networks, coordination and governance of agro-food value chains, and the so-called “quality turn” in food production and consumption’ (Ponte, Citation2016, p. 12). Convention theory is now experiencing something of a resurgence as new branches of agro-food research start to embrace it (including consumption, see Stamer, Citation2018; Thorslund & Lassen, Citation2017). Increased engagement has been accompanied by a proliferation in the ways that ‘convention’ and associated concepts of ‘quality’ and ‘orders of worth’ are used. This gives occasion to reflect on what a convention is and the analytical work it is expected to do. An initial aim of this paper is to bring clarity to the various concepts that are at stake here by considering their use within convention theory and related approaches that deal more explicitly with qualities (notably Callon et al., Citation2002). Convention theory and the economy of qualities perspective offer complementary insights into different aspects valuation and evaluation (cf. Lamont, Citation2012) as well as to economic competition and coordination (cf. Ponte & Gibbon, Citation2005). Our view in this paper is that there are clear benefits to integrating these perspectives, however they do not – whether individually or in combination – sufficiently conceptualize the role of consumption in the phenomena that they interrogate.

This observation recalls the more general debate about the terms on which understandings of consumption are ‘brought in’ (or not) to agro-food research. Again, these debates were particularly active between the late 1990s and mid-2000s (e.g. Goodman & DuPuis, Citation2002; Lockie & Kitto, Citation2000). Notably, David Goodman suggested that despite widespread recognition of the need to acknowledge consumption, its inclusion had been nominal and that the field was ‘impeded by a reluctance to cut loose from analytic frameworks that privilege the production “moment”’ (Citation2002, p. 272).Footnote2 Consequently, Goodman identified a gulf between conceptualizations of consumption within agro-food scholarship (as consumer behaviour, needs to be met, or markets to be created) and the richness of perspectives being developed under the wider ‘turn’ to consumption across the social sciences (see Miller, Citation1995). In some ways, much has changed in the intervening years. Consumption appears to have been legitimated as a key topic within agro-food research, which has become much more attuned to developments in contemporary social theory (see M. K. Goodman, Citation2016). However, many of the problems identified by David Goodman still remain. For example, consumption continues to be conceptualized somewhat narrowly as either shopping, aggregates of consumer choices, or eating. Relatedly, consumption scholarship has itself been a vibrant field of conceptual renewal over the last c. 20 years and yet many of its key advances have yet to register in agro-food research.

More generally, the deep-seated intellectual divisions of labour that underpin the separation and purification of ‘production’ and ‘consumption’ as distinctive analytic categories are showing few signs of abatement. For example the aforementioned extension of convention theory to studies of consumption has happened at the expense of studying production, reflecting the continued tendency for research on food production and food consumption to be compartmentalized (Murcott, Citation2013). The gulf between agro-food research and consumption scholarship still stands, suggesting that the overall tenor of Goodman's critique remains valid. This paper engages with this problematic by taking stock of recent developments in consumption scholarship – theories of practice (following Warde, Citation2005) and consumer involvement in qualification processes (Cochoy, Citation2008) – suggesting that they are conceptually compatible with convention theory and the economy of qualities. We demonstrate how they substantively expand and help deliver on the integrative potential of these approaches. In turn we suggest that the analysis of qualities and conventions provides a way to explore the interactions between production and consumption without artificially separating or privileging either category.

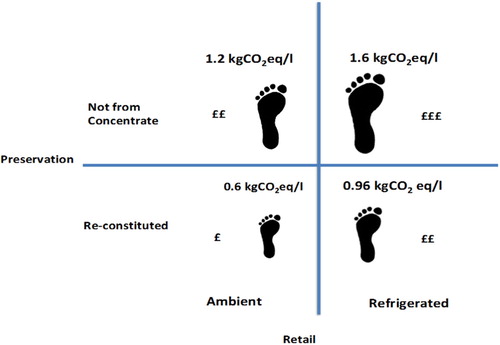

These arguments are advanced through an analysis of ‘freshness’, which arguably is both a quality of food and a key coordinating principle of contemporary food systems. The industrial production of ‘freshness’ since the post-1930 development of cold chain has had significant consequences for the geographies of primary production, the organization of supply chains, investments in new technologies, branding and retail strategies, the ecological burden of global distribution, and consumer expectations. Despite this commercial, cultural and environmental importance, the topic of freshness has not been subject to sustained and critical social scientific engagement (although see Freidberg, Citation2009 for a notable exception). This paper joins the emerging body of work (Evans, Citation2014; Foster et al., Citation2012; Holmes, Citation2013; Jackson et al., Citation2019) that addresses the unintended consequences of securing freshness in the production and consumption of food. Specifically it focuses on the orange juice (henceforth OJ) market, which is currently on an environmentally problematic trajectory.Footnote3 shows the carbon footprint associated with different varieties of OJ. Production and consumption in the UK retail market has converged on OJ that is refrigerated and ‘not from concentrate’. This is the most carbon-intensive variety and our analysis demonstrates how the embedding of freshness conventions has positioned it favourably within the economy of qualities.

The following sections elaborate the debates that frame our analysis, allowing us to present ‘freshness’ as an exemplar of the issues under consideration. We then draw on a range of qualitative and secondary empirical materials to present the case study of OJ. Our analysis first explores the historical and industrial production of ‘freshness’ conventions, arguing that they provide the basis for both competition and coordination between firms. We then address the role of consumption and consumers in this economy of qualities. To conclude we consider the theoretical implications of our analysis and identify future research directions. Additionally, by highlighting the contingency of environmentally problematic conventions and the mutability of qualities, we shed new light on research and policy approaches to sustainable food that have hitherto taken conventions for granted and viewed qualities as self-evident.

Conventions, qualities and orders of worth

Convention theory has provided ‘analytical guidance’ and ‘theoretical insight’ across multiple branches of agro-food scholarship (Ponte, Citation2016, p. 12). The starting point for these applications is On justification (2006[1991]) in which Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot posit the existence of multiple ‘orders of worth’. These orders serve as reference points for the legitimation and justification of action, and as the basis for agreement and coordination (or not) in social and economic life. In addition to market conventions that equate worth with economic value (price), Boltanski and Thévenot identify the culturally established – and so culturally contingent – grounds for locating worth in terms of: collective interest (civic orders), productivity and efficiency (industrial), trust (domestic), reputation and opinion (renown), and creativity (inspired). The literature on agro-food economies and their social worlds has developed along at least two lines to encompass: (i) a more explicit focus on conventions as the basis for economic coordination and (ii) an emphasis on qualities as the basis of exchange. The concepts of convention, quality and orders of worth are often treated interchangeably as a result of their associations with convention theory. This lack of conceptual and definitional clarity means that ‘conventions’ are currently expected to do a lot of analytic work. The term is used variously to refer to: agreements and expectations that help organize the food chain, the multiple ‘orders of worth’ that underpin these ‘rules’, and to qualities of food. This section briefly reviews, separates and clarifies the concepts that are at stake here. It then considers their usage in relation to the analysis of freshness in the agro-food sector.

First, conventions refer to established ways of doing things. They are formal and informal agreements – based on mutually constituted expectations about the conduct of others – that facilitate the coordination of economic activity (see Biggart & Beamish, Citation2003; Stark, Citation2009; Wilkinson, Citation1997). By this definition, we suggest that the requirement for food to be ‘fresh’ can reasonably be thought of as a convention. Beyond the basic observation that nobody expects food to be ‘rotten’ or ‘spoiled’, we note that agreement over the desirability of ‘freshness’ has consequences for firm strategy. Food manufacturers and retailers in alternative food networks have long contrasted the freshness and quality of their produce with their industrial counterparts, however key actors in conventional food systems are now making claims and competing on the ‘freshness’ of their produce. For example, supermarkets across Europe offer ‘freshness guarantees’Footnote4 just as Subway – the world's largest fast-food restaurant – has trademarked the advertising slogan ‘eat fresh’. These expectations have consequences in terms of which foodstuffs are produced and where (e.g. the agricultural resources dedicated to producing fresh fruit and vegetables) as well as how they are processed, transported and sold (e.g. cold chain technologies). In this reading, the orders of worth (market, civic, domestic and so on) identified by Boltanski and Thévenot are not conventions. Rather, they represent shared repertoires and conceptions of the common good that are appealed to in order to justify action, resolve disagreements and thus establish the ‘rules’ that guide conduct and coordination. The analysis that follows explores the emergence and reproduction of ‘freshness conventions’ through reference to the orders of worth that underpin and sustain them.

In another usage, conventions refer to agreements about the characteristics that form the basis for exchange (see Eymard-Duvernay, Citation1989; Storper & Salais, Citation1997). This approach stresses that price alone is not always a reliable basis for evaluating a product or its production process. In this view, the orders of worth identified by Boltanski and Thévenot represent the various criteria by which products are qualified for exchange and/or the terms on which qualities (other than price) are used to compete or solve problems of economic coordination. At one level, the term ‘qualities’ describes distinctive (non-pecuniary) attributes of food, however it also carries ‘unfailingly positive connotations’ insofar as saying something has quality ‘is almost always to recommend it’ (Harvey et al., Citation2004, p. 1). Understood as a quality of food, freshness is no exception. It refers to a set of characteristics that are typically evaluated positively through reference to multiple orders of worth. Nevertheless, the analysis that follows suggests that there is a subtle but important distinction to be maintained between qualities of food (specific attributes and characteristics) and notions of quality (the value attached to these qualities).

In order to make this move, we draw on the economy of qualities perspectives developed by Callon et al. (Citation2002). It stresses that qualities are never simply observed, rather:

All quality is obtained at the end of a process of qualification, and all qualification aims to establish a constellation of characteristics, stabilized at least for a while, which are attached to the product and transform it temporarily into a tradable good in the market. (Callon et al., Citation2002, p. 199, emphasis added)

For the purposes of the analysis that follows, we suggest that it is useful disentangle these overlapping concepts along the following lines: (i) using conventions to refer to mutually constituted and widespread expectations; (ii) using qualities to refer to specific combinations of characteristics that are attached to products or processes; (iii) using quality to refer to agreements around the positive judgement of value that emerges from a constellation of characteristics, and (iv) using orders of worth to refer to shared notions of the common good that underpin conventions and the positive evaluation of particular qualities. These distinctions suggest that a combination of convention theory and the economy of qualities is necessary (cf. Ponte & Gibbon, Citation2005) and the novelty of the integration proposed here – aside from the work it does in defining and clarifying concepts – is to enrich understandings of how consumption relates to qualities and conventions. It is to this that we now turn.

Consumption, convention theory and the economy of qualities

Both convention theory and the economy of qualities perspective gesture towards the analysis of consumption. For a convention to be a mutually constituted expectation it must surely reach beyond the coordination of supply side actors. In the case of ‘freshness’, it is not controversial to suggest that this is also a key concern for consumers (see Eurobarometer, Citation2010). Similarly, Callon et al. are explicit that qualification involves an apparatus of distributed cognition, and that success in the economy of qualities is dependent on consumer preferences. Nevertheless, the development of these approaches has been lopsided and biased to production, leaving consumption as something of an afterthought. Applications of convention theory to agro-food scholarship (e.g. Morgan et al., Citation2008) conceptualize consumption as the aggregate of choices that send signals representing ‘demand’ in the marketplace (e.g. ‘discerning’, ‘affluent’ and ‘educated’ consumers driving the growth of ‘quality’ produce). Similarly, the economy of qualities perspective conceptualizes consumption as a matter of market attachment – effectively truncating its relevance at the moment of purchase (see Miller, Citation2002). In both cases, consumption ‘emerges only to disappear again into a production-centred framework’ (cf. Goodman & DuPuis, Citation2002, p. 7). By extension, the significant potential that exists for these approaches to transcend the bifurcation of economic activity into ‘production’ and ‘consumption’ is stymied. Part of the issue, as we see it, is the ongoing reluctance – within and beyond agro-food research – to acknowledge insights from contemporary consumption scholarship and incorporate these into understandings of markets. This section introduces some key developments, suggesting that they help in realizing the ambition of integrating production and consumption via a focus on qualities and conventions.

In recent years, the sociology of consumption – at least in Northern and Western Europe – has experienced a ‘turn’ to practice (following Warde, Citation2005). Put briefly, this work suggests that practices – as opposed to individuals, social structures or discourses – are the basic unit of social analysis. Practices are recognizable and discernible entities that encompass practical activities and their representation. They are configured by the alignment of heterogeneous elements including skills, affective know-how, meanings, bodily activities and materials. In the normal running of things, people carry out practices in accordance with shared and historically established understandings of normality and appropriate conduct. Practices therefore take the form of routinized behaviours that are performed by individuals without too much in the way of conscious deliberation.Footnote5 Applying these ideas to the study of consumption, Warde (Citation2005, p. 145) establishes that a good deal of consumption occurs not for its own sake, but within and for the sake of practices. It follows that consumption scholarship could usefully turn its attention to the dynamics of practices, emphasizing ‘routine over actions, flow and sequence over discrete acts, dispositions over decisions and practical consciousness over deliberation’ (Warde, Citation2014, p. 286). Further, by emphasizing ‘doing over thinking, the material over the symbolic, and embodied practical competence over expressive virtuosity in the fashioned presentation of self’ (Warde, Citation2014, p. 286), this approach provides a rejoinder to the dominant view of consumption as social communication.

Conceptualizing consumption in this way hints at significant overlap with the pre-occupations of convention theory. It also offers a powerful corrective to the limitations of how consumption is conceptualized in agro-food research, convention theory, and the economy of qualities of perspective. Most notably it expands the gaze of consumption scholarship beyond mercantile acts and ‘shopping’. It encompasses a focus on activities that are not colloquially understood as ‘consuming’ – for example cycling or playing the cello – but nevertheless require ‘moments’ of consumption (e.g. access to specialized equipment) in order to carry them out in accordance with prevailing standards of normality and appropriate conduct. There is a risk here of rendering the concept analytically useless, fuelling concerns from outside of consumption scholarship that the field fails to define what is – and what is not – consumption (see Graeber, Citation2011). Warde helpfully identifies a number of phenomena that might reasonably be thought of as consumption. In addition to ‘acquisition’, he points to ‘appropriation’ (involving use, personalization and incorporation into people's lives) and ‘appreciation’ (involving frameworks of judgement as well as deriving pleasure or satisfaction) as further moments of consumption. Recent developments (see Evans, Citation2019) have suggested that each of these ‘As’ has a counterpart ‘D’ (‘appreciation’ mirrors ‘devaluation’; ‘appropriation’ mirrors ‘divestment’; ‘acquisition’ mirrors ‘disposal’) that should be included in order to capture additional moments of consumption without lapsing into the trap of viewing virtually any activity as consumption. We operationalize this definition in the analysis that follows.

Within the economy of qualities framework, Franck Cochoy has already encouraged greater attention to consumption. Cochoy's interventions in consumption scholarship (e.g. Citation2007, Citation2008Footnote6) attend to the role of devices (cf. Callon et al., Citation2007) – such as shopping trolleys and supermarket shelves – in moving consumers beyond price-based calculations. He suggests that consumption involves qualculation – quality-based judgements of ‘the best choice when calculation is not possible’ (Cochoy, Citation2008, p. 26). Qualculation is a delicate balancing act between intentions, the options available and the information (e.g. on packaging) that is offered. Further, he suggests that consumption also involves calqulation in which individual shoppers are transformed into collective clusters by ‘anticipating, measuring, testing, influencing and correcting’ (Cochoy, Citation2008, p. 30) discrepancies between one another. Calqulation refers to the collective aspects of consumer choice (e.g. how clusters reach decisions) and the ways in which clusters position themselves in relation to others (e.g. by copying or distancing themselves from particular forms of consumption). The concepts of qualculation and calqulation represent important additions to the account of consumption offered by the economy of qualities framework. It could be argued, however, that they suffer the same limitation of curtailing these advances at the moment of purchase. We suggest that some of the ‘moments’ identified above – specifically appreciation and devaluation – could usefully extend these developments further to encompass a focus on processes of consumption. Our analysis explores how these qualitative calculations are both institutionalized in practices as entities and reproduced in the performance of practices.

Case study: freshness and the orange juice market

The analysis that follows is based on two empirical studies that were initiated to explore changes in the organization and environmental impact of food production and consumption. The first is a study of innovation in the provision of OJ undertaken as part of a project exploring the role of demand in stimulating eco-innovation. The research involved key informant interviews with multiple retailers, manufactures and processors, brand owners, trade associations, producers of agricultural inputs, packaging suppliers and organizations representing primary producers. Secondary and documentary data were collected from industry sustainability reports, market research sources, household expenditure surveys, standards and regulations, and historical accounts of the case study commodities (notably Hamilton, Citation2009). The second is an ethnographically informed study involving sustained and intimate contact with 19 ‘ordinary’ households (53 respondents) on two streets in the North West of EnglandFootnote7 over a 10-month period. This was ostensibly a study of food waste, however, it encompassed a focus on broader food practices including planning, shopping, storage, preparation and eating. A range of methods were used including repeat in-depth interviews with multiple household members, ‘hanging out’ (in people's homes and in neighbourhood amenities), ‘going along’ to discuss and observe food practices (such as grocery shopping and meal preparation) in situ, cupboard rummages, fridge inventories and home tours.

This paper is not a vehicle for the extensive presentation of empirical materials. Detailed and separate summaries of these studies and their findings are offered elsewhere (Evans, Citation2014; Mylan, Citation2016). The purpose and unique contribution of this paper is to bring insights from the two studies together, make ‘freshness’ the explicit focus, and demonstrate some of the ways in which a focus on qualities and conventions may contribute to the development of ‘integrative approaches to production and consumption’ (cf. Goodman & DuPuis, Citation2002, p. 7). In piecing together a study of ‘production’ and a study of ‘consumption’, we acknowledge there is much our analysis cannot do. For example, we are not able to explore the relationships or the role of feedback between the producers and consumers in the individual studies. Nevertheless, our analysis moves between theoretical registers and empirical illustrations to showcase the integrative potential of qualities and conventions.

We proceed via the case study of orange juice (OJ). OJ is defined (at least in North America and Europe) as the juice that results following manual or mechanical extraction from a defined number of species of orange fruit (Hamilton, Citation2009). In the UK retail market, OJ is categorized and classified according to methods of processing and preservation (Mintel, Citation2010). Juice labelled ‘from concentrate’ undergoes heat treatment that removes water content and reduces microbial activity, resulting in a pulp that is then transported in bulk and eventually reconstituted (with water) to its original strength. By contrast, juice labelled ‘not from concentrate’ is transported chilled and at full strength. Further variation in juice results from whether or not it is sold ‘chilled’ or ‘at ambient temperature’. Looking again at , OJ that is ‘not from concentrate’ and ‘chilled’ is shown to have the highest carbon footprint (6.4 kg of CO2 equivalent per litre), nearly triple the lowest impact (2.4 kg of CO2 equivalent per litre) version (‘reconstituted’ and ‘ambient’). Despite only modest variation in taste across these four versions of OJ (Mintel, Citation2010), production and consumption has converged on the version with the highest environmental impact.

A discussion of how much carbon is necessary or acceptable in the production and consumption of OJ is beyond the scope of this paper. On the one hand, this is a technical rather than a social scientific question. On the other, it would require a systematic effort on our part to make ‘environmental impact’ a visible attribute of OJ markets and to position ‘low carbon’ favourably within the economy of qualities. While this could be an interesting application of the theoretical resources developed here (perhaps engaging with debates about adding a dedicated ecological ‘order of worth’ to the categories of convention theory, e.g. Blok, Citation2013), our intentions are more analytic than normative. We are interested in how the environmental impacts of production and consumption can be animated by a focus on the mutability of qualities and contingency of conventions. Accordingly we focus on the commercial and cultural significance of freshness, showing how it underscores the high-carbon trajectory of the OJ market. We begin with consideration of how the associations between processing, preservation and the desirability of ‘fresh’ OJ have historically taken hold.

Assembling conventions

We are primarily interested in the embedding of freshness conventions in the UK retail market, however, any such account must necessarily make detours to the United States. It was here that the commercial processing of orange juice began in the early twentieth century as a response to surplus orange production in Florida. The first mechanized juicing plants opened in the 1920s, at which point preservation involved boiling to remove water. This produced a thick sticky pulp that was canned and then consumers were given instructions to dilute before drinking. Canned juice is reported to have a ‘cooked’ flavour (Hamilton, Citation2009) that does not replicate the taste of freshly squeezed oranges. Accordingly, campaigns were launched that sought to establish the equivalence of ‘fresh’ and ‘canned’ juice through appeals to a range of other qualities such as health, convenience and associations with place (). Multiple orders of worth can be located in these campaigning efforts – for example domestic (establishing trust in food through appeals to nature and locality, cf. Murdoch & Miele, Citation1999) and industrial (the efficiency of canning compared to juicing oranges manually) – to establish the ‘freshness’ and quality of canned juice. While these strategies were successful in overcoming the suboptimal taste of canned OJ at the time, these initial associations were soon to be disrupted by subsequent technological developments.

Figure 2 Advertising from the Florida Department of Citrus, 1930s

Source: Florida Department of Citrus.

The OJ market expanded rapidly between the mid-1940s and the start of the 1960s (Morris, Citation2010; White, Citation1986) accompanied by a shift in preservation and processing techniques. Concentrated juice could now be frozen following a period of less intensive boiling. The development and diffusion of commercial freezing technologies made it possible to produce and distribute a product – known as frozen concentrated orange juice (FCOJ) – that more closely resembles the flavour of fresh-squeezed oranges (Morris, Citation2010). FCOJ became known as ‘the miracle product’ by virtue of its combination of desirable attributes and qualities such as affordability (underpinned by market orders of worth), health (civic orders) and convenience (industrial) as well as tasting better (renown) and more natural (domestic) than the previously popular canned juice. Above all else, FCOJ was promoted as ‘fresh’ – with marketing campaigns emphasizing that it is ‘fresher’ than canned juice or ‘the freshest orange juice frozen’ (see Mylan, Citation2016). As was the case with canned juice, the quality and ‘freshness’ of FCOJ was established through reference to a range of other qualities (the attributes of ‘the miracle product’) and the orders of worth that sustain them. In the United Kingdom, the growth of the OJ market was slow throughout the 1970s but the introduction of FCOJ saw juice consumption more than double from 97 ml per person per week in 1981 to 251 ml per person per week in 1990. During the same period, OJ was distributed by milkmen (sic), who have historically delivered ‘fresh’ produce directly to people's houses on a daily basis. It seems credible that this will have played a role in establishing the links between OJ and ‘freshness’.

More generally, the move from canned juice to FCOJ between the mid-1940s and mid-1980s is central to understanding the emergence of environmentally damaging freshness conventions in the production and consumption of OJ. First, it established the enduring links between low temperatures and the ‘freshness’ of OJ. Allied to this, the expectation that OJ ought to be ‘fresh’ – and so cold – started to shape the ways in which its production and distribution was orchestrated. Notably, the ‘miracle product’ (FCOJ) was reliant on the development of cold chain technologies and the juice industry was among the first to take advantage of advances in mechanically refrigerated transportation. Tropicana's ‘Juice Trains’ – including the first unit train in the food industry – transported large amounts of frozen juice from Florida to New York and were reportedly a famous sight throughout the 1970s (White, Citation1986). Viewed as such, there has been a clear shift in the meaning of ‘fresh’ OJ from associations with time and proximity (freshly squeezed Florida oranges) to the technology that secures it (cf. Freidberg, Citation2009). Ambiguity as to what ‘freshness’ is has enabled claims to be made on the freshness of industrially produced OJ.

The evolving economy of qualities

The definitional slipperiness of ‘freshness’ underpinned a regulatory intervention made by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1961. They had become concerned that consumers may not fully understand the characteristics of OJ. The Standards of Identity Trials that followed (discussed at length by Hamilton, Citation2009) concluded that the word ‘fresh’ could not accurately be used to describe commercially produced or processed OJ. It continues to be prohibited by United States and European regulation although a number of other words are used in its place such as ‘pure’.Footnote8 Despite these prohibitions, ‘freshness’ has been a defining feature of generic and branded orange juice marketing since the birth of the industry and it remains the terrain on which firms attempt to differentiate products on the basis of quality (cf. Callon et al., Citation2002). Competition in the juice industry intensified from the 1980s onwards as a result of new firms (such as Proctor and Gamble) entering the OJ market (which was hitherto dominated by major brands such as Tropicana and Minute Maid), supermarkets developing their own-brand ranges, increased expenditure on branded advertising (Morris, Citation2010), and new product developments (such as ‘added pulp’). Just as freshness conventions (the mutually constituted expectation the OJ ought to be fresh) facilitates the coordination of economic activity along the food chain, so too can they set the stage for economic competition.

Accepting that ‘fresh’ is synonymous with quality in the OJ market, it is instructive to consider how juice gets qualified as ‘fresh’ when the use of the word is prohibited. The orders of worth identified by convention theory help understand the positive evaluation and favourable position of ‘fresh’ OJ within an economy of qualities, however they say little of the (intrinsic) attributes and characteristics that must be considered in order to position produce as ‘fresh’. The case of OJ shows that these are both historically variable and tied intimately to technological development. The aforementioned shift from canned pulp to FCOJ was followed by a subsequent shift to ‘not from concentrate’ (NFC) OJ. This was enabled by the development of ‘flash pasteurization’ techniques that obviated the need for concentration. Tropicana introduced the term on its packaging in the early 1980s, accompanied by a marketing campaign highlighting that NFC juice involves ‘less processing’, is more ‘natural’, and is therefore ‘fresher’ than FCOJ. Tropicana's NFC juice expanded into Europe in the early 1990s, where sales grew year on year. By the end of the decade, NFC per-capita juice consumption in the United Kingdom was double that of the United States (Morris, Citation2010). Concentration can therefore be seen as a key attribute that is taken into consideration when qualifying OJ as ‘fresh’.

Another key attribute is refrigeration. NFC juice initially required refrigeration during transportation and storage to minimize microbial activity, however, advances in aseptic packaging technology have reduced the need for doing so. NFC juice is nevertheless sold in refrigerated cabinets in most UK supermarkets. Recalling the long-standing associations between the temperature and ‘freshness’ of OJ, these cabinets appear to be functioning less as a method of preservation than as a qualification device that frames the encounter between producers and consumers (Mylan, Citation2016; cf. Cochoy, Citation2011). Even when reconstituted juice is sold from the fridge, it outperforms – and is sold for a higher price – than NFC juice sold at ambient temperature. This suggests that refrigeration has superseded labelling (as ‘not from concentrate’) as the key mechanism through which firms qualify OJ as ‘fresh’, compete on quality and charge price premiums (Foster et al., Citation2012). Notably, OJ is a key product around which UK supermarkets have sought to develop their own ‘premium’ offerings to rival and compete with branded goods. Given the trend for most OJ (80 per cent of the UK market by the end of the 1990s, see Euromonitor, Citation2010) to be purchased in supermarkets, they have used the device at their disposal – in store refrigeration – to support the requalification (from concentration to refrigeration) of what ‘freshness’ is in relation to OJ. Crucially, though, it is the combination of ‘not from concentrate’ and ‘chilled’ that qualifies OJ as ‘fresh’ and allows for product differentiation along the lines of quality.

The ‘invisible mouth’

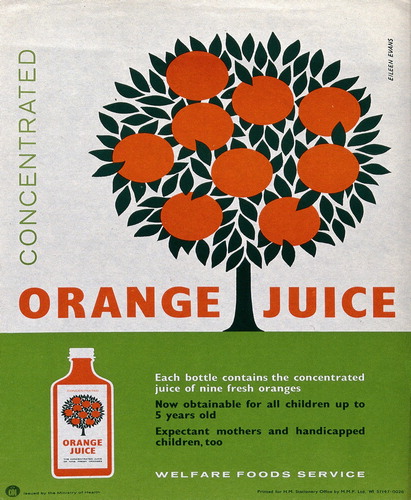

Having explored the emergence and persistence of freshness conventions in the ‘production’ of OJ, our analysis turns now to consideration of freshness and OJ consumption. Consumption and consumers – the ‘invisible mouth’ in agro-food scholarship (Lockie, Citation2002) – are central to understanding the ‘creeping normalization’ (cf. Shove & Southerton, Citation2000) of OJ's high-carbon trajectory. The industrial production of freshness as a quality of OJ in the United States is matched by a parallel history involving concerted efforts to construct and mobilize the fresh OJ consumer (cf. Evans et al., Citation2017; Lockie, Citation2002). For example, the Florida state government established the Florida Department of Citrus in 1935 to represent the interests of Florida juice growers. Amongst other things, they ran advertising campaigns to promote OJ consumption (see ). These campaigns were complemented by the efforts of Florida Foods, a cooperative of orange growers, who initiated a programme of door-to-door product demonstrations extolling the health benefits of OJ and giving instructions on how to use canned juice. In the United Kingdom, OJ was first introduced as part of the wartime Government's Vitamin Welfare Scheme and continued as part of the post-WWII ‘Marshall Plan’ for European recovery. It was promoted as healthy by virtue of its high vitamin C content and was offered to mothers and infants through welfare clinics (and thus known colloquially as ‘welfare juice’) in medicine-like bottles (see ). The associations between OJ and health have persisted in subsequent decades, largely as a result of nutritional advice offered by the UK's National Health Service.Footnote9 It is important, then, to acknowledge that a range of state and civil society actors – as well as firms – have been involved in stimulating consumer demand for OJ.

Figure 3 Poster from the UK's Ministry of Health offering free daily portions of orange juice 1939–1945 (catalogue reference: INF 13/194)

Source: Wellcome Collection.

Attention must also be paid to how technologies mediate the relationships between producers and consumers, and how technological change shapes discernible patterns of consumption. For example between 1924 and 1926, the Florida Citrus Exchange, another cooperative of orange growers, stimulated demand for surplus oranges by distributing OJ extractors to 16,000 households in the United States (Hamilton, Citation2009). Similarly, the aforementioned post-war growth in the juice industry in the United States relied not just on the mechanization of the cold chain but also the attendant rise in domestic refrigerators. By the late 1940s, these were present in three-quarters of American homes (Bowden & Offer, Citation1994). At this time just 2 per cent of British households had a (relatively small) fridge, rising to 58 per cent in 1970. By the late 1990s, when supermarkets were using chillers as qualification devices, nearly every British household had a refrigerator that was large enoughFootnote10 to store cartons of ‘fresh’ OJ and continue chilling them after purchase.

Our research into contemporary UK food practices reveals that freshness conventions are sustained by wider cultural imperatives to cook and eat ‘properly’. Amongst the participating households, there is a set of shared understandings of what this means and entails. For reasons of brevity, these can be summarized as follows (see Evans, Citation2014):

Meals that have been prepared – preferably cooked – at home are ‘proper’ whereas snacks or takeaways are not.

Meals should be prepared using ‘healthy’ ingredients, including ‘fresh’ fruit and vegetables.

‘Fresh’ produce is preferable to tinned, canned or frozen alternatives.

Meals should be prepared from scratch as opposed to ‘cheating’ by, for example, using ready-made stir-in sauces.

Even participants whose food practices are far removed from this ideal still situate themselves in terms of their perceived ‘failure’ to adhere to it. Importantly, ‘freshness’ cuts across many dimensions of ‘proper’ food. Respondents use it to: describe a set of favourable sensory associations (‘a really nice flavour, it is light, and, um, it just tastes really fresh’); narrate the time and distance between harvest and consumption (‘when vegetables are fresh and I get them straight from my allotment, they taste better’); how recently something has been cooked (‘there is nothing nicer than freshly baked bread, straight out the oven’), and to position food in relation to less desirable alternatives (‘frozen vegetables are handy, but fresh are much better for you’) or ‘processed’ food more generally (‘food is best when it is fresh, when it hasn't been messed with’). Again, ‘freshness’ can be seen as a mutable and nebulous quality that is configured via the intersection of other qualities and the orders of worth that sustain them. Moreover, it suggests that freshness conventions not only shape the organization of food production, they also shape the coordination of practices involving food consumption. It is not surprising, then, that these data suggest ‘freshness’ is a key consideration in the consumption of OJ with, for example, parents giving their children a small glass of fresh juice at breakfast because ‘it is good for them’.

Performance and qualification

We turn now to the question of how consumers measure and evaluate the ‘freshness’ of the different OJ options proposed to them against a backdrop in which none of them can be marketed as such. The successful qualification of OJ as ‘fresh’ is reliant on – and open to negotiation or resistance by – processes of consumption. However, our data suggest that in their performance of food-related practices, consumers have aligned with the industrial production of ‘fresh’ OJ and become ‘attached’ to refrigerated, not-from-concentrate varieties. For example, when Kirsty (a married mother of two who owns her own home and identifies as ‘solidly working class’) goes to the supermarket, which she does every 7–10 days, she purchases 2–3 cartons (containing 1–1.5 litres each) of OJ (‘my lot get through it by the trough load’). She only ever purchases chilled juice that ‘has bits in’Footnote11 and is labelled ‘pure’. She reports that it is ‘just better, better quality, and fresher’. She also suggests it is ‘more like real fruit’, which is important in the context of her household repeatedly struggling to eat the fruit they purchase as part of their efforts to ‘eat properly’. She makes a quality-based calculation (qualculation) on the basis of the information available (the refrigerator, the packaging). That she does so on behalf of – and in the interests of – other household members suggests it also involves calquation. Viewed as such, the ways in which Kirsty shops, in common with many respondents, sustain the associations between ‘freshness’, ‘quality’ and the high-carbon trajectory of OJ.

We do not dispute the role of commercial actors or their power to enrol consumers in ‘the distributed apparatus of qualification’ (Callon et al., Citation2002, p. 206), however, care must be taken not to overstate the extent to which the industrial production of freshness is a fait accompli. Our respondents do not appear quite so ignorant of agricultural production or easily duped into believing that industrially produced food is somehow ‘natural’ (cf. Freidberg, Citation2009, p. 7). For example, when talking to Heather (a married mother of two children who owns her home and identifies as coming from a ‘well to do’ background) in her kitchen, she talks generally about the importance of eating fresh foods. She lightly pokes fun at the pastoral images and text that are used to promote the produce in her cupboards and fridge (including OJ), noting the ‘irony’ that ‘it obviously comes from a factory somewhere, not a cottage garden or country kitchen’. When pressed on why freshness matters to her, she explains that it helps guarantee the [high] quality of produce. She also draws a distinction between people ‘like her’ and people who consume less fresh produce because ‘they can't afford it or maybe don't care as much about eating properly’. This echoes Plessz and Gojard’s (Citation2015) work on fresh vegetable consumption in France, which highlights how the associations that have been historically attached to fresh produce are compatible with middle class ideas of health and good taste. It follows that consumers may – independently of direct commercial intervention – be invested in sustaining the distinction between food that is fresh and food that is not as means of marking identities and upholding symbolic divisions between groups (cf. Cochoy on calquation).

From a different angle, it will be recalled that consumption is a process that extends beyond the moment of ‘shopping’. As such, consumers are liable to continually measure, monitor and assess ‘freshness’ in the course of performing the sequences of activity (e.g. cooking, eating, storing, disposing) that together constitute their food-related practices. While ongoing qualification trials (involving appreciation and devaluation) are more pronounced in relation to some foodstuffs (e.g. chicken) than others, these data reveal instances of OJ being deemed ‘no longer fresh’ enough to be potable. For example, when talking through the items in Tom's (an IT professional in his mid-1920s who lives alone in a converted apartment that he owns) fridge, he comes across a carton of OJ that he had purchased especially for a visitor (he ‘doesn't really drink it’ himself). He checks the expiration date, which is still fine, but then sips a little directly from the carton and concludes it no longer tastes fresh enough for him to ‘go out of [his] way’ to drink it. Consequently, he pours it down the drain before placing the empty carton in the recycling bin (disposal has followed devaluation). This serves as a reminder that foodstuffs are particularly well suited to claims that ‘things’, especially things in flux (e.g. as they decay), play an active role in processes of qualification (cf. Evans, Citation2018; see also Gregson et al., Citation2013). It also suggests that to properly account for consumption, attention must be paid both to the qualification of goods at an abstract and general level (the ‘freshness’ of NFC juice that is sold chilled) and to the trajectories of specific products as they unfold in real time (ongoing processes of requalification).

Discussion and conclusion

This paper has elaborated some characteristics of an approach that places ‘qualities’ and ‘conventions’ at the forefront of thinking about market coordination. To illustrate, the preceding analysis has looked across the production and consumption of OJ to explore the genesis and reproduction of freshness conventions. Particular attention has been paid to technological developments in processing and preservation, the relationships between ‘freshness’ and other qualities of food, and distributed processes of qualification. Rather than laying the analytic burden fully on convention theory, we have argued that the economy of qualities perspective offers complementary insights. Convention theory animates outcomes related to agreement – the expectation that OJ ought to be ‘fresh’ – and the orders of worth that underpin this convention. It demonstrates how freshness conventions provide the basis for coordination – for example in the case of manufacturers, distributors, retailers and consumers agreeing to keep OJ refrigerated along the chain. The economy of qualities perspective animates outcomes related to the temporary stabilization of characteristics that transform a product into tradable good (‘fresh’ OJ). It demonstrates how qualities provide the basis for economic competition – for example in the case of supermarkets using in-store refrigerators to promote their own-brand premium OJ offerings. We suggest there are clear merits in bringing these approaches together. For example the economy of qualities perspective attends to the characteristics and attributes that are taken into consideration when products are qualified, whereas convention theory highlights the terms on which these qualities become exchangeable. We do not claim any novelty in making the case for combination. Our contribution here has been to separate and clarify a number of related concepts – conventions, qualities, quality and orders of worth – in order to better mobilize these ideas and their empirical application in agro-food scholarship.

Our second and key contribution has been to more fully account for processes of consumption. The demonstrable significance of freshness in the OJ market intimates that mass consumption has aligned with the industrial production of a quality. Rather than interpreting this, simply, as the commercial manipulation of consumer demand – and thus using consumption as a way to talk about production (cf. Goodman, Citation2002) – our analysis has been informed by contemporary developments in consumption scholarship. It has demonstrated that patterns of consumption are configured by a range of actors; that consumers are invested in the qualification processes that uphold the associations between ‘freshness’ and quality, and that freshness conventions are reproduced and sustained through food practices. Additionally, we have shown that consumer involvement in the distributed apparatus of qualification is not exhausted at the point or ‘moment’ of acquisition. Having made the case for paying greater attention to consumption, it is important that we acknowledge the flipside of this argument. Consumption scholarship has much to learn from contemporary developments in agro-food research and it seems credible to suggest that concepts related to qualities and conventions offer some useful departures from an over-reliance on Bourdieusian notions of taste (see also Harvey et al., Citation2004, p. 2). For example, they offer greater insight into the mechanisms through which judgments and evaluations are made in moments of appreciation and devaluation.

It would seem, then, that a focus on qualities and conventions can help develop understandings that ‘account more adequately for both contingency and regularity along food chains’ (cf. Lockie & Kitto, Citation2000, p. 4). While there are a lot of conceptual resources at stake here (convention theory, economy of qualities, theories of practice), we note that they belong to the same ‘family’ of theories (Jones & Murphy, Citation2011). They are for the most part ontologically compatible and share, to varying degrees, an interest in practical routines, heterogeneous associations (between humans and non-humans, economic and non-economic actors) and stabilized social action. Taken together they offer significant potential for genuinely integrative analyses of production and consumption. We acknowledge that our analysis of freshness does not fully realize this potential and that it is limited by its reliance on bringing two separate studies together ex post facto. Important questions remain, for example, concerning the ways in which producers respond to changes in consumer practices. There is a need for further studies of specific products that are initiated with the seamless integration of ‘production’ and ‘consumption’ – and the recursive interactions between them – in mind from the outset. Our hope is that the analysis of the OJ market convinces of this need as well as offering the theoretical tools to guide the design and analysis of future research. Additionally, our approach to qualities and conventions of freshness could usefully be extended and applied to a range of other empirical cases – for example the convenience, authenticity or ethical credentials of food – where the articulation of value and the coordination of production and consumption are a key concern.

Finally, we return to the theme of environmental sustainability. When applied to food, freshness is almost universally seen as a good thing and yet the analysis has shown that its commercial and cultural significance carries adverse environmental consequences. It follows that qualities and conventions of freshness should be central to any discussion of promoting greater sustainability in the OJ market. One approach is to think about changing the combination of attributes that are considered when OJ is qualified as fresh. Our analysis shows that ‘fresh’ OJ has been re-qualified over time, suggesting that there is nothing self-evident about the current situation. The challenge here is to change shared understandings and expectations of what freshness is such that it aligns with the lowest carbon attributes (concentrated, ambient – see ). Another approach is to abandon freshness as a coordinating principle in the production and consumption of OJ. Our analysis shows that the significance of freshness derives from its associations with other qualities (such as health and provenance) and the various orders of worth that underpin these. The challenge here is to think about re-organizing the OJ market around the qualities that freshness stands in for. Reference could be made to multiple orders of worth in order to position low-carbon juice favourably within the economy of qualities. It could be promoted on the grounds that it is at least as healthy (civic orders) and safe (domestic) as its high-carbon counterpart (tentative ecological orders) but that it tastes just as good (renown). Both approaches would require a coordinated effort across ‘production’ and ‘consumption’ involving a range of human and non-human actors. However, so too does the maintenance of the OJ market and its current high-carbon trajectory. Looking at what holds these arrangements in place – qualities and conventions – offers new insights into how they might be reconfigured in a more sustainable register.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous referees and the Editorial Board for engaging so thoroughly and constructively with this manuscript. It has been improved considerably as a result. The ideas in this paper have also benefited from ongoing discussion with colleagues at the Universities of Manchester, Sheffield and Bristol. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

David M. Evans

David M. Evans is Professor of Material Culture at the University of Bristol. His research is located broadly within economic sociology with specific interests in food and sustainability. His current work (funded by the EPSRC) is focused on single use plastics – packaging in particular – and their role in processes of economic organization. He is also researching and writing a book on supermarkets and social change.

Josephine Mylan

Josephine Mylan is Lecturer in Sustainability and Innovation, Alliance Manchester Business School, University of Manchester. Her research engages with questions of how societies can transition to less resource intensive ways of meeting their needs. She has specific interests in sustainable consumption and production, low carbon transitions, firm and industry responses to environmental problems, and the co-evolution of technology and cultural conventions.

Notes

1 Here and throughout, ‘food’ is used as shorthand for ‘food and drink’.

2 The same could be said of a great many fields – for example the making of ethical trade relations.

3 Environmental impacts are multiple, however we restrict our claims to carbon intensity.

4 For example: https://www.sainsburys.co.uk/shop/gb/groceries/get-ideas/values/freshness or https://www.pingodoce.pt/pingodoce-institucional/noticias/selo-frescura-pingo-doce/ (accessed 01/02/2019).

5 The theory nevertheless stresses that people can and do experiment with different ways of doing things, meaning that the reproduction of practices (as entities) is by no means guaranteed.

6 Earlier and unpublished versions of this work are cited by Callon et al. (Citation2002).

7 The term ‘ordinary’ reflects that the streets were chosen in order to encounter everyday lives as they are found without recourse to conventional categories of sociological analysis (following Miller, Citation2008). The study makes no claims to representativeness, however the participating households reflect a spread of income band, age, housing structure, housing tenure and household composition.

8 OJ can be labelled ‘freshly squeezed’ if it is sold within 36 hours of extraction. This variety of juice accounts for less than 1 per cent of the UK market.

9 For example http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/5ADAY/Pages/Whatcounts.aspx (accessed 01/02/2019).

10 In the United Kingdom, large fridges and freezers – of the kind found in North American homes – are still not commonplace. A fridge that is 130 cm (51.2 inches) high is considered tall.

11 ‘Added pulp’ can be interpreted as another innovation that producers have used to qualify industrial OJ as ‘fresh’. Kirsty's practices hint at some of the ways in which they may have been successful in doing so.

References

- Biggart, N. & Beamish, T. (2003). The economic sociology of conventions: Habit, custom, practice and routine in market order. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 443–464.

- Blok, A. (2013). Pragmatic sociology as political ecology: On the many worths of nature(s). European Journal of Social Theory, 16(4), 492–510.

- Boltanski, L. & Thévenot, L. (2006[1991]). De la justification: Les Économies de la Grandeur. Paris: Gallimard.

- Bowden, S. & Offer, A. (1994). Household appliances and the use of time: The United States and Britain since the 1920s. The Economic History Review, 47(4), 725–748.

- Callon, M., Meadel, C. & Rabeharisoa, V. (2002). The economy of qualities. Economy and Society, 31(2), 194–217.

- Callon, M., Millo, Y. & Muniesa, F. (2007). Market devices. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cochoy, F. (2007). A sociology of market-things: On tending the garden of choices in mass retailing. The Sociological Review, 55(S2), 109–129.

- Cochoy, F. (2008). Calculation, qualculation, calqulation: Shopping cart arithmetic, equipped cognition and the clustered consumer. Marketing Theory, 8(1), 15–44.

- Cochoy, F. (2011). De la Curiosité: l'art de la séduction Marchande. Malakoff: Armand Colin.

- Eurobarometer. (2010). Special Eurobarometer 354: Food-related risks.

- Euromonitor. (2010). Fruit and vegetable juice: United Kingdom.

- Evans, D. (2014). Food waste. London: Bloomsbury.

- Evans, D. M. (2018). Rethinking material cultures of sustainability: Commodity consumption, cultural biographies and following the thing. Transactions of the IBG, 43(1), 110-121.

- Evans, D. M. (2019). What is consumption, where has it been going, and does it still matter? The Sociological Review, 67(3), 499–517.

- Evans, D., Welch, D. & Swaffield, J. (2017). Constructing and mobilizing ‘the consumer’: Responsibility, consumption and the politics of sustainability. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(6), 1396–1412.

- Eymard-Duvernay, F. (1989). Conventions de qualité et forms de coordination. Revue Économique 40(2), 129–150.

- Foster, C., McMeekin, A. & Mylan, J. (2012). The entanglement of consumer expectations and (eco) innovation sequences: The case of orange juice. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 24(4), 391–405.

- Freidberg, S. (2009). Fresh: A perishable history. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Freidberg, S. (2014). Calculating sustainability in supply chain capitalism. Economy and Society, 42(4), 571–596.

- Glaze, S. & Richardson, B. (2017). Poor choice? Smith, Hayek and the moral economy of food consumption. Economy and Society, 46(1), 128–151.

- Goodman, D. (2002). Rethinking food production–consumption: Integrative perspectives. Sociologia Ruralis, 42(4), 271–277.

- Goodman, D. & DuPuis, E. (2002). Knowing food and growing food: Beyond the production-consumption debate in the sociology of agriculture. Sociologica Ruralis, 42(1), 2–22.

- Goodman, M. K. (2016). Food geographies I: Relational foodscapes and the busy-ness of being more-than-food. Progress in Human Geography, 40(2), 257–266.

- Graeber, D. (2011). Consumption. Current Anthropology, 52(4), 489–511.

- Gregson, N., Watkins, H. & Calestani, M. (2013). Political markets: Recycling, economization and marketization. Economy and Society, 42(1), 1–25.

- Hamilton, A. (2009). Squeezed: What you don’t know about orange juice. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Harvey, M., McMeekin, A. & Warde, A. (2004). Qualities of food. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Holmes, S. (2013). Fresh fruit, broken bodies: Migrant farmworkers in the United States. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Horton, P., Banwart, S., Brockington, D., Brown, G. W., Bruce, R., Cameron, D., … Jackson, P. (2017). An agenda for integrated system-wide interdisciplinary agri-food research. Food Security, 9(2), 195–210.

- Ingram, J. (2011). A food systems approach to researching food security and its interactions with global environmental change. Food Security, 3(4), 417–431.

- Jackson, P., Evans, D., Truninger, M., Meah, A. & Baptista, J. (2019) Enacting freshness in the UK and Portuguese agri-food sectors. Transactions of the IBG, 44(1), 79–93.

- Jones, A. & Murphy, J.T. (2011). Theorizing practice in economic geography: Foundations, challenges, and possibilities. Progress in Human Geography, 35(3), 366–392.

- Lamont, M. (2012). Toward a comparative sociology of valuation and evaluation. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 201–221.

- Lockie, S. (2002). The invisible mouth: Mobilizing ‘the consumer’ in food production–consumption networks. Sociologia Ruralis, 42(4), 278–294.

- Lockie, S. & Kitto, S. (2000). Beyond the farm gate: Production–consumption networks and agri-food research. Sociologia Ruralis, 40(1), 3–19.

- Marsden, T. & Morley, A. (2014). Sustainable food systems: Building a new paradigm, London: Earthscan.

- Miller, D. (1995). Acknowledging consumption. London: Routledge.

- Miller, D. (2002). Turning Callon the right way up. Economy and Society, 31(2), 218–233.

- Miller, D. (2008). The comfort of things. Cambridge: Polity.

- Mintel. (2010, November). Fruit juice and juice drinks – UK. London: Mintel.

- Morgan, K., Marsden, T. & Murdoch, J. (2008). Worlds of food: Place, power, and provenance in the food chain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morris, R.A. (2010). The US orange and grapefruit juice markets: History, development, growth and change. EDIS document FE834. Gainesville: Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida.

- Murcott, A. (2013). A burgeoning field. In A. Murcott, W. Belasco & P. Jackson (Eds.), The handbook of food research (pp. 3–24). London: Bloomsbury.

- Murdoch, J. & Miele, M. (1999). ‘Back to nature’: Changing ‘worlds of production’ in the food sector. Sociologia Ruralis, 39(4), 465–483.

- Murdoch, J. & Miele, M. (2004). A new aesthetic of food? Relational reflexivity in the ‘alternative’ food movement. In M. Harvey, A. McMeekin & A. Warde (Eds.), Qualities of food (pp. 156–175). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Mylan, J. (2016). The directionality of desire in the economy of qualities: The case of retailers, refrigeration and reconstituted orange juice. In H. Bulkeley, M. Paterson & J. Stripple (Eds.), Toward a cultural politics of climate change: Devices, desires and dissent (pp. 142–159). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Plessz, M. & Gojard, S. (2015). Fresh is best? Social position, cooking, and vegetable consumption in France. Sociology, 49(1), 172-190.

- Ponte, S. (2016). Convention theory in the Anglophone agro-food literature: Past, present and future. Journal of Rural Studies, 44(4), 12–23.

- Ponte, S. & Gibbon, P. (2005). Quality standards, conventions and the governance of global value chains. Economy and Society, 34(1), 1–31.

- Shove E. & Southerton D. (2000). Defrosting the freezer: From novelty to convenience: A narrative of normalization. Journal of Material Culture, 5(3), 301–319.

- Stamer, N. (2018). Moral conventions in food consumption and their relationship to consumers’ social background. Journal of Consumer Culture, 18(1), 202–222.

- Stark, D. (2009). The sense of dissonance: Accounts of worth in economic life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Storper, M. & Salais, R. (1997). Worlds of production. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Thorslund, C. & Lassen, J. (2017). Context, orders of worth, and the justification of meat consumption practices. Sociologia Ruralis, 57(S1), 836–858.

- Warde, A. (2005). Consumption and theories of practice. Journal of Consumer Culture, 5(2), 131–153.

- Warde, A. (2014). After taste: Culture, consumption and theories of practice. Journal of Consumer Culture, 14(3), 279–303.

- Wheeler, K. (2018). The moral economy of ready-made food. British Journal of Sociology, 69(4), 1271–1292.

- White, J. W. (1986). The Great Yellow Fleet. Marino, CA: Golden West Books.

- Wilkinson, J. (1997). A new paradigm for economic analysis: Recent convergences in French social science and an exploration of the convention theory approach with a consideration of its application to the analysis of the agrofood system. Economy and Society, 26(3), 305–313.