Abstract

The importance of tenure security for development and wellbeing is often reduced to questions about how titles can guarantee rights, overlooking the contested and layered nature of property rights themselves. We use the case of Lagos to analyse property rights as ‘analogue’ rather than ‘digital’ in nature – things that only exist by degree, where a dynamic urban situation renders the distinction between a right and a claim much less clear than conventional approaches suggest. We argue that property taxation plays important and unanticipated roles in efforts to realize property rights. To fully understand attempts to construct rights it is necessary to analyse the range of payments, documents, social relations and other strategic moves that people make to thicken property claims in contexts of ‘radical insecurity’.

Introduction

There is nothing like a feeling of tenure security when it comes to Lagos. At any fucking time you can be denied. But if you are in a community, we are like one big family. This gives you social security but not tenure security – this has to come from government.Footnote1

Property is a social fact or it is no fact at all. It is not something that is established by individual assertion … . Property is a matter of shared expectations … The learning and evolution of ideologies, myths and metaphors underlies the consent that makes the opportunities of owners real. (Schmid, Citation1999, p. 237)

Debates on the utility and effectiveness of tenure regularization and property titling rumble on, particularly in developing countries where the layering of pre-colonial, colonial and postcolonial land regimes have generated complex multi-layered systems for acquiring and using property. In the wake of the hugely influential work of de Soto (Citation2000), and his many critics, the substance of debate has primarily revolved around whether and how giving people formal property rights contributes to their own wellbeing and to economic growth. However, behind most positions in this debate lie assumptions about the feasibility of distinguishing between possessing a property right and not possessing one – and beyond this between owning and not owning – which, we argue in this paper, do not stand up to close scrutiny in much of the world. Although few scholars today would see property rights as a ‘digital’ system of zeros and ones, the assumptions behind dominant conceptions of ownership run deep, and shape the ideational and normative framings of both policymakers and publics. There is therefore an ongoing need to better understand the relationship between legal rights and the broader range of claims made to property in situations where the latter are so effective unsettling the former, often rendering the line between the two thin and mutable.

We came unintentionally to the issue of property rights in Lagos; our research was designed initially to explore property tax reforms and their relationship to broader governance reforms in the city. However, we became alert to an added layer of complexity early on, while discussing our research proposition with a Nigerian colleague. He responded to our mention of the Lagos Land Use Charge by remarking: ‘Ah! My mum doesn’t joke with that. Even when she travels she calls us to make sure we’ve paid it for her’. We were immediately struck by how unusual it is to find a tax – let alone a relatively new tax – which people are so enthusiastic to pay that they prioritize it while travelling abroad. This cannot be explained by fear of enforcement, due to the low enforcement capacity shown in studies of income tax in Lagos. Nor, as it turned out, can it be explained by a strong association between paying and enjoying improved by infrastructure and services. Instead, our research became centred on uses and meanings of taxation which emerge as an unintended consequence of reform and its interplay with realities on the ground, feeding into understandings of claims to maintain control and use of property.

When taxation is considered in relation to property rights, it is often not through the lens of property tax but rather with reference to the role of property rights in enhancing fiscal capacity more generally (see e.g. Besley & Persson, Citation2009), or normative questions such as whether inheritance tax is an infringement of property rights (O'Kane, Citation1997). Yet the payment of property tax, we found, is often part of a broader process through which contemporary Lagosians use assemblages of both formal and informal payments, social and political relationships and various documents to make their property rights more secure. This prompted us to rethink what a property right fundamentally is, how it is constituted by the moves that people make to try and realize it, and how easily, if at all, it can be distinguished from a property claim in a context such as Lagos. We use the case of Lagos to analyse the quality of a property right itself as not ‘digital’ in nature – something that exists or doesn’t, but as ‘analogue’ – something that exists in varying and variable degree, and in relation to which the dividing line between a right and a claim is not as clear as conventional scholarship would suggest. This highlights the importance of analysing the strategic moves that people make to increase the solidity of rights they think they already have.Footnote2

This paper is based primarily on fieldwork in Lagos in September-October 2016 and February 2017, consisting of interviews with a wide range of stakeholders including tax and land officials, property owners and developers, waterfront communities, individuals and groups associated with omo onile land claims, lawyers and NGO representatives. Across these two field visits, we moved repeatedly between the three worlds of middle-class Lagosians fighting rival claimants to their land whilst instigating their own claims on others, waterfront communities struggling to defend their auto-constructed property claims, and the bureaucratic spaces of land and tax officials. Analytical reflection after each trip allowed us to iteratively build our analysis of the interplay of rights and claims, and their relationship to everyday payments, bureaucratic procedures and the progressive accumulation of paper, moral citizenship and coercive capacity that bolsters Lagosians’ efforts to secure themselves in place.

The article begins with a discussion of tenure security in developing countries and how this relates to broader debates on property rights and property claims, with particular attention to the neglected role of taxation. This is followed by a discussion of the forces which have shaped conceptions of landed property in Lagos through three distinct historical epochs, producing in the present a densely-layered, ambiguous realm of property rights and radically insecure tenure. The paper then introduces Lagos State’s two major reforms relevant to our focus: the introduction of the property tax known as the Land Use Charge (LUC), and streamlining the issuance of Certificates of Occupancy. Given that these new systems coexist with extensive informal payments relating to property, we introduce the role of omo onile, Lagos’ increasingly ubiquitous claimants to traditional land rights, whose demands meld customary payments and extortion. We then use two narratives to show how richer and poorer Lagosians both, in different ways, pursue mixed tactics to maximize leverage and secure property rights within this dynamic context, with property tax playing an important but unanticipated role. Finally, our conclusion discusses what Lagosians’ tactics can tell us about the nature of property rights themselves, as processual rather than bounded social facts, and as obtainable more often in degree than as absolutes. It also suggests that official property rights are almost hopelessly thin and limited in their capacity to generate corresponding non-interference by others, such that the main practices associated with property in such contexts are multidimensional efforts to progressively thicken property claims.

Conceptualizing property rights and the role of taxation

The debate about the liberating potential of private property titles has been a persistent backbone of international development discourse in the past half century. The emphasis on the developmental benefits of legal title in urban areas was amplified by the influential work of Peruvian political economist Hernando de Soto (Citation2000), who forwarded the persuasively linear argument that formalizing existing informal systems of property tenure in the developing world would unleash huge reserves of land collateral for grassroots capital investment. De Soto’s work represented the apogee of growing faith in the transformational potential of legal institutions in urban development, based on his claim that without formal representations (i.e. property titles), the assets of the poor are ‘dead capital’.

De Soto’s work has been criticized on a conceptual level for sidelining the material fact of inequality of access to property, its teleological and ahistorical approach to the evolution of property rights globally, its assumption that it is possible or even desirable to individualize all land titles, the risks it would pose to basic survival assets for the poor, and its undifferentiated treatment of the poor in general (Bromley, Citation2008; Hendrix, Citation1995; Musembi, Citation2007; Payne, Citation2001; Toulmin, Citation2009). It has also been criticized at a more empirical level for generalizing far beyond what the evidence can reliably indicate (Woodruff, Citation2001), sidelining considerable evidence that access to land collateral is far from the most significant predictor of access to credit in poor communities (Gilbert, Citation2002); and, most significantly in African contexts, assuming that informal systems are linear and singular, when in fact ‘bundles’ of differential or relative use and allocation rights abound (Cousins et al., Citation2005; Earle, Citation2014; Marx, Citation2009; Musembi, Citation2007). Despite this, the popularity of these ideas with both donor organizations and a significant section of developing-world policymakers persists.

The ease of criticizing de Soto today should not obscure the complexity of ongoing conceptual and empirical dilemmas about property rights and tenure security. Recent literature has questioned the very idea that we know what security of tenure even is (Obeng-Odoom & Stilwell, Citation2013). Legalistic definitions rooted in capitalist institutions contend with social conceptions based on fundamentally different moral economies (Amanor, Citation2010; Obeng-Odoom & Stilwell, Citation2013). In trying to unpack the concept, Van Gelder (Citation2010) introduces a distinction between legal security, perceived security and de facto security. This acknowledges important differences between official documents that purport to bestow security, perceptions that one’s property is secure (which may be based on factors such as community relations or past experience), and the actual fact of holding onto property for a long period of time. These different elements of tenure security are seen as overlapping, including through the ‘stacking’ of formal and informal rules, whereby occupants attempt to construct a bridge from de facto to legal tenure security (Van Gelder, Citation2010, p. 454).

Our approach acknowledges these important interventions, but we argue that they do not go far enough in problematizing security of tenure. The idea of building bridges from de facto to legal security implies a linear process through which actual security becomes formalized, while the reality can be much messier and can often look like the reverse: i.e. people using myriad legal and official documents in order to try and build their de facto security (even as some use the same tools to demolish that of others). Beyond this, the empirical realities in a city like Lagos remind us of the need for conceptual rigour in interrogating not only the relationship between property titles and tenure security, but the relationship between these phenomena and the concepts of property rights and property claims. Crucially, the latter concept alerts us to how titles and rights acquire their most significant meaning not by legal priority alone but by participation in a dynamic social field. Rather than being categorically separate, this study showcases planes of action in which one can easily become the other, via the interaction between law, popular legitimacy and ‘acts on the ground’.

Conventional legal approaches distinguish firmly between property rights (which involve a corresponding duty by others not to interfere with the right-holder’s possession) and mere privileges or freedoms to use property (Cole & Grossman, Citation2002, p. 323). In this approach, a right is a legal quality that needs to be clearly distinguished from a claim to a right; rights are not acquired merely by claiming them. This evolved legalistic conception of property rights is rooted in the Lockean conception whereby government exists to transform possessions into property (backed up by the threat of state coercion), but also diverges from Locke’s argument that appropriation and use are the ultimate origin of property. Contemporary ideas of property rights do not hold that first possession or use is in themselves constitutive of property, but rather that context-specific legal principles and social legitimation are. Thus ‘a property claim becomes a property right only when it is socially or legally recognized as such, signifying the voluntary acceptance and enforcement of concomitant duties of noninterference’ (Cole & Grossman, Citation2002, p. 323). The problem with such definitions, however, is first that they conflate legal and social recognition, and second that they presume that acceptance and enforcement of such non-interference are achieved (or indeed achievable).

These ideas of property rights, distinct from mere property claims, have flowed through generations of policies that assume private property rights can be meaningfully introduced to the exclusion of other claims, and that these rights can be securely and wholly guaranteed by titles (see e.g. Deininger, Citation2003). However, in much of the world, the encounter between indigenous institutions for accessing and claiming property, colonial property institutions, and further sweeping land reforms after independence have led to unsettled tenurial landscapes that complicate the very idea of property. At a conceptual level, it is often recognized that property ‘is both an individual and a collective or associational right’, and that ‘in different historical epochs or different cultures, one aspect or the other emerges pre-eminent’ (O'Kane, Citation1997, p. 474). This however overlooks the degree to which in many postcolonial contexts neither is pre-eminent, and the two dimensions continually bleed into one another. The colonial bifurcation between the realm of the collective/customary on the one hand, and the individual/private on the other – famously theorized by Mamdani (Citation1996) – thus was never complete, and obscured more nuanced understandings of property.

In what follows, we offer an empirically-grounded contribution to this literature. We explore the role that new reforms to taxation, other official payments, and various forms of related documents play in the construction of property rights in Lagos – but also how these compete with a realm of unofficial (but highly organized) payments and processes to ‘traditional’ authorities who also claim rights over property. In this complex landscape of property-related transactions, one of the most interesting tactics has been the adaptative reframing of the Lagos Land Use Charge, a payment with no actual statutory link to establishing property rights, but whose perceived utility has become a social fact; with its legitimacy and currency forcing its partial admission into more formal processes which purport to streamline and exclude such practices. Taxation has received inadequate attention in the literature on tenure security and property rights: indeed, tax is predicated on an assumption of a clear, unambiguous owner of the property in question; i.e. it is seen as a consequence of property rights rather than constitutive of them. However in the course of our research we have found that the reality is rather different: where legal frameworks concerning land rights are inadequate, mutable and coexistent with powerful informal norms, tax itself may come to form one of the elements in the building of a claim which, in as much as it is to some degree socially, even if not legally recognized, is not so easy to distinguish from a property right.

The historical evolution of property rights in Lagos

The history of property rights in Lagos is marked by three different epochs, each with their own implications. First is a precolonial era, marked primarily by communal ownership and derived rights of tenure or occupancy, in which the present-day Lagos area was a patchwork of communities, farmland and bush, but which grew most dynamically around the trading town established on Lagos Island.Footnote3 Precolonial land ownership was vested in lineages. Men and women had use-rights to communal property but not alienable rights of sale; instead allocation would revert to the collective if it fell into disuse. The family compound, as residential, agricultural, business and social unit was the node of development, and beyond the large kinship networks engendered by polygamous marriage, people could attach themselves to a family by giving labour or political support. Slaves could be allocated land, and immigrants could gain use-rights with family consent; the legitimating payment was either a tribute of produce, or a symbolic payment (such as kola nut). The rent system known as ishakole was therefore important not just for its cash value but because it displayed a continuing acknowledgement of allocation rights. However, over time these allottees and their descendants sometimes also became subsidiary land-allocators in their own right, leading to contested claims of entitlement and origin (Barnes, Citation1986).

The second epoch began around the time of formal British annexation of Lagos in 1861. Mann (Citation1991) captures the contradictions, evolutions and working misunderstandings built into land title at that transitional moment. On the eve of British takeover, communal rights in land were already evolving under population growth and urbanization, with changing relationships between people translated into bundles of recognized title and usage rights. Returnee ex-slaves from Brazil and Sierra Leone, as well as Europeans, brought their own accustomed conceptions of alienable private property rights, and interpreted land grants from the Oba of Lagos in this way. A market developed, consolidated by formal British rule introducing Crown laws and an ethic of development through private property (Mann, Citation1991, p. 690). In creating and recognizing these rights, the new colonial dispensation did not de-recognize pre-existing concepts of land tenure and title. Mann even notes that colonial courts often sided with collective ownership when adjudicating disputes between individual grantees or their descendants and those who claimed customary rights in the land, meaning that in the end, the legal effect of crown grants stopped short of transforming a communal system into an individuated one; instead, the existence of one continued inside the other. Indeed, customary communal tenure remained the dominant mode for most Lagosians. ‘Most persons never bothered to obtain crown grants for the land they occupied. Even in cases where individuals did acquire crown grants … land granted by the crown often became collectively owned family property after the death of the original grantee’ (Mann, Citation1991, p. 691). This dual system continued throughout the next century, albeit punctuated by occasional large-scale planned development and alienation by government as the port-colony of Lagos became the capital of colonial Nigeria.

The third epoch was the zenith of Nigeria’s military-led developmental statism: the introduction of the 1978 Land Use Decree (subsequently, Act). This law aimed to replace the plethora of customary, private and Crown systems with a new tenure system vesting all land rights in the state, with the stated aim of tidying up overlaps, eliminating fraud and promoting development. After 1978, urban land was given out under statutory rights of occupancy by state governors, while rural land was allocated under customary rights of occupancy by local governments.Footnote4 The approval of the state was also needed for formal transfer or sale. However, due in part to the state’s incomplete capacity to enforce these transformations, and in part to transitional provisions written into the Act, the new system did not completely extinguish the old but came to exist alongside it.Footnote5 In urban areas, the law allowed that the ownership of developed land held under pre-existing freehold be effectively recognized.

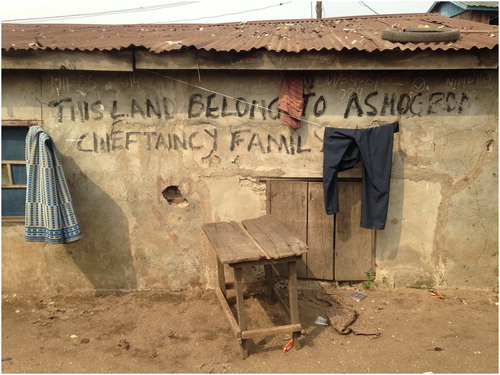

The evolution of property rights over these three epochs mean that land procedures are marked by what Bierschenk and Olivier de Sardan (Citation2014, p. 221) call the ‘institutional layering’ common in postcolonial bureaucracies: instead of displacing previous practices, the new system accretes on top of the old and coexists with it. For example in Lagos today, most plots or property legally established and registered pre-1978 have a freehold property right, while plots established or registered post-1978 are 99-year leaseholds, with the value affected by the years left on the lease. Neither of these systems have extinguished the legal recognition of historic claims to land allocation by Chieftaincy families. Furthermore, land transactions are marked by informalization and opportunism: processes accelerated equally by economic boom in the 1980s and post-structural adjustment decay in the 1990s, both of which promoted urban expansion, and made property both a commodity in demand and a safe store of wealth, while the capacity of the state to regulate it fell behind. This led to plentiful disputes, resulting in fait accomplit as perhaps the most important form of tenure, and the rise of the phenomenon known as omo onile – ‘sons of the soil’ with the coercive capacity and notional legitimacy to demand that property developers and home improvers pay levies in the name of customary payments to landowning communities.

These trends were given further momentum by Nigeria’s mid-2000s oil boom, which fuelled a property bubble. While this led to even greater demand for urban land and inflated land prices throughout Lagos, the recession that began in 2015 stimulated the growth in unemployed and underemployed people who sought to capitalize on land values through coercion, while capital export restrictions and the poor performance of other investments re-fuelled speculative demand for real estate. In common with many other cities across the world, Lagos property values reached heights far out of proportion with earnings and GDP growth potential; hence the observation made by one interviewee that ‘land is the crude oil of Lagos’.Footnote6 These conditions heightened both the salience of urban property rights and the significance of efforts to raise government revenue from property.

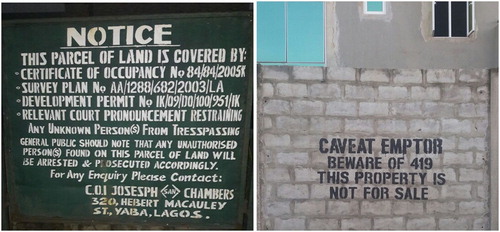

Insecure tenure, as can be seen above, is a product of the layered history, but is also an aspect of a dominant present-day Nigerian milieu of ‘radical insecurity’. Pratten (Citation2013, p. 246) contrasts this with episodic or recurrent insecurity in the face of a particular threat, being instead rooted in ‘the context itself, a permanent, radical sense of uncertainty, unpredictability and insecurity’. This concept also represents how economic, political, physical, existential and identity-based precarity blend into a pervasive preoccupation with the problematics of fixity and security on a general level (Marshall, Citation2009). The combination of the Land Use Act with increasingly corrupt military dictatorships contributed significantly to this insecurity as regards land in Lagos; officials had more incentive and power to alienate lands for purposes other than those stated, some notorious evictions of poor communities for development purposes took place, and fake land sales became a stock trick during the boom in fraudulent ‘419’ activities accompanying the cash-starved post-structural adjustment period. These compounded the ubiquitous contestations, court cases, evictions, family feuds and pluralistic marriage and inheritance practices which already rendered the property picture complex.Footnote7 Such practices also spawned an arsenal of pre-emptive measures ranging from visible signalling to wide-ranging legal armaments (see ), sights now commonplace in Nigeria, as well as many other parts of Africa. Less well-understood however, is how various forms of formal and informal taxation shape radical insecurity over property.

Reforming tax and land administration in Lagos

The introduction of the new system of property tax known as the Land Use Charge (LUC) in Lagos was part of a much broader overhaul of governance since State Governor Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s 1999–2007 tenure, about which there is a growing literature (see Babawale and Nubi, Citation2011; Bekker & Fourchard, Citation2013; Bodea & Lebas, Citation2016; Cheeseman & de Gramont, Citation2017). Through a series of reforms involving semi-privatization and strengthening of taxes in the State, government revenues increased from less than 10 billion Naira in 1999 to almost 140 billion a decade later (Cheeseman & de Gramont, Citation2017, p. 458). The majority of this increase was due to reforms of Personal Income Taxation (PIT), but LUC also increased hugely, to the extent that annual revenues from the LUC in 2015 were around 14 times the amount collected in 2004.Footnote8

The 2001 LUC reforms consolidated three pre-existing payments (tenement rates, ground rent and Neighbourhood Improvement Charge) into one, and were inspired in part by a World Bank report from the early 1990s suggesting that Lagos State was only collecting around 25 per cent of potential tenement rates, and less than 5 per cent of potential ground rent. The reforms experienced substantial teething problems, but from 2007, Governor Fashola (Tinubu’s successor) placed increased priority on the LUC, giving the private company tasked with implementing it – the Land Records Company (LRC) – a grant to make an inventory of all properties in the state, which led to an increase from 45,000 enumerated properties in 2007 to 750,000 by 2010.Footnote9 Substantial civic education was undertaken to promote the virtues of the tax, and collection dramatically grew from the late 2000s.

Although clearly a very effective set of official reforms, it is important to note that there is significant scope for informal negotiation in how the LUC is applied in practice. One interviewee related how her mother had disputed an LUC assessment by appealing on two grounds: first that she was a widowed retiree, and second that she was from a deep-rooted Lagos Island-based family who had a history of sponsoring public works. The blurred boundaries of procedure thus encompass citizenship claims based both on formally recognized categories of hardship, and a concurrent register in which indigeneity, moral citizenship, kinship, rectitude and community contribution back up the formal categories and can mediate the state’s claim.Footnote10 A further point of interest is the question of who actually pays the tax in practice. In theory, it should be paid by property owners, and most rental contracts have a clause about the landlord paying. But when disputes arise because the owner refuses to pay, which can lead to the sealing off of the property, the LUC Tribunal can give the tenant a letter making them ‘an agent for the LUC’ and they can legitimately deduct it from their rent.Footnote11 As we explore later, the question of who pays also holds relevance for claims made about property rights.

Alongside tax reforms, another central policy plank of the Tinubu era was the reform and streamlining of the official process of recognizing property rights: the issuance of Certificates of Occupancy, colloquially known as ‘C of O’. In law, this is the only document which confers a freehold or leasehold property right, and is therefore considered the ‘gold standard’ by those seeking absolute tenure security.Footnote12 Despite these reforms, the vast majority of land transactions and acquisitions in this city of up to 20 million people never reach the C of O stage. In 2016, fewer than 1,000 such were approved, and in the highest performing year (2013), it was only 2,282.Footnote13 Officially purchasing a property necessitates paying a range of taxes and fees collectively termed ‘Governor’s Consent’ in order to acquire a Deed of Assignment, stamped by the Attorney General and Commissioner for Stamp Duty. This is recognized by government as an equitable interest, but for a legal interest, a C of O is required. Unlike the Deed of Assignment, getting a C of O is not just about making payments: even post-reform, it is a complex and demanding process through which multiple documents, historic records, photographs and plans are carefully vetted and need to be signed off by as many as nine different people. The C of O thus remains a distant ideal for the vast majority. Moreover, although having a C of O is the greatest form of legal security of tenure attainable, even the few who possess one may not be safe from contesting claims to pre-existing rights to the land, as we will show.

In the lacuna created between acquisition of a property and the semi-mythical quest for a robust formal title, each paper milestone on the journey towards a C of O becomes its own imputed property right by proxy, with differently leveragable powers to ward off threats of displacement or contestation, whether from officialdom or rival claim-makers. Every payment made and every document received linked to the acquisition, demarcation, exchange and use of property, anything committed to paper that can indicate official recognition of some claim to the property, can become part of the effort to assemble property rights and anchor claims. Moreover, beyond the realm of official payments and documents lies a parallel system where institutionalized but technically non-formal payments and documents have their own role.

Informal payments and property rights

There are two different registers of ‘informal’ payments on property in Lagos. The first is an offshoot of the official procedures for obtaining documents for land titling: in other words, bribes to officials to facilitate or speed up bureaucratic processes.Footnote14 These are very often demanded and paid, but are of minor public salience compared to the major mode of informal property taxation in Lagos: the structured system known as omo onile, which makes its claims in an entirely different register (Agboola et al., Citation2017).Footnote15 Payment of levies to groups claiming longstanding ancestral links and traditional authority over the land is common across cities in Southern Nigeria. Termed ajagungbales (‘land grabbers’) in Ogun State, and claiming the title of Community Development Associations (or CDAs) in Benin City (Ezeanah, Citation2018), these groups usually go by the term omo onile in Lagos. In its literal sense of ‘children of the land’ the term is associated with indigeneity and land rights, but in popular discourse it is much more pejorative, being ‘synonymous with “parasites, hoodlums and enemies of progress”’.Footnote16 Where omo onile groups lay claim to a plot of land (regardless of the historical legitimacy of this claim, which can vary widely) they will demand payment from a prospective property developer at every stage of the process. Thus, for example, the laying of foundations, building of successive floors, and roofing will all be associated with payment of a specific levy, which can amount to very substantial sums, subject to no official regulation. As one official noted, ‘you basically have to pay omo onile for every truck of materials that comes in’.Footnote17

There is significant ambiguity surrounding the term omo onile, though it now has such negative connotations that few would self-identify with it. At the upper end of society, Lagos families with longstanding claims to land (which they actively maintain by making clear their expectations that they should benefit from current use of that land) distance themselves from the practices associated with ‘the lowly omo onile, who are thugs’.Footnote18 This idea of disreputable youth predating on land is contrasted with the ‘respected, good Lagos families’ that do not have to resort to violence. However, even those considered by others to be ‘lowly omo onile’ often have well-developed claims to legitimacy, derived from membership of families claiming first-settler status. One way in which these rights are asserted and defended is by recourse to the early colonial period Mann describes, with one claimant citing an 1860 judgement and stating that ‘the colonial master really helped the families to determine the boundaries of their land’.Footnote19 In the words of another member of a family claiming rights to 18.7 hectares of land in Lagos, ‘I’m not a land-grabber, I’m fighting for my rights. I don’t call myself omo onile. If you do that, people see you as coming with touts … my family don’t do that’. Such families argue that there is a new form of ‘contemporary land-grabbers’ who do not belong to a historic family and are often the hired hands of criminal interests.Footnote20

Omo onile payments are frequently complicated by the large and hierarchical nature of the extended families claiming authority over the land in question. It is not uncommon to have to make payments to a lower-level omo onile ‘boss’ as well as the ‘big omo onile boss’, often under the threat of violence.Footnote21 Moreover, the ‘original’ claims to a particular piece of land may be fragmented among many descendants, which inflates the levies demanded by these groups, since elders have to distribute resources among an ever-growing number of people. One member of an Ikorodu-based family with long-standing land claims referred to having to distribute resources to around 200 people, determined by a family tree that dates back to 1860.Footnote22 Unsurprisingly, family disputes over the distribution of such payments are also rife. Anyone hoping to build on land in Lagos that may be affected by omo onile claims (a large but unknown proportion of urban land) has to factor in this cost from the outset. These practices are so informally institutionalized as to be comparable with taxes in terms of their effect on investment behaviour and viability.Footnote23 Getting around the problem is challenging and unpredictable. For the wealthy, one option is to purchase land that has already been allocated to a government scheme, or to purchase an unfinished building carcass from a developer who has already negotiated with claimants. Yet even these are no guarantee of absolute security if the omo onile do not feel adequately compensated by the first buyer.

From the perspective of those making these claims, a common complaint is that the compensation provided by the military government when acquiring land under the 1978 Land Use Act was highly insufficient, and unrelated to market value. Moreover, land previously acquired by government for public works is often actually used for private residential or commercial developments. Given their claims to historic ownership, omo onile groups feel they should benefit from this increased value when it is used for profit.Footnote24 It is this history of contested legitimacy and the ‘original sin’ of government alienation under autocratic rule that underpins the accusation that ‘government is the chief land-grabber’, with the state conversely using the discourse of criminality to undermine traditional claimants.Footnote25 The determination to maintain rights over land has been augmented in Lagos because land is one of the few domains in which traditional leaders are still able to exert authority. This has made clamping down on omo onile activities difficult politically, since they are substantial in both number and influence; in certain respects, these practices were for a significant time tacitly condoned.

Payments, documents and tactical land claims: two Lagosian cases

To gain any sense of security over property in Lagos, it is necessary to navigate the web of formal and informal payments discussed above, which are backed with varying degrees of coercion and legitimacy. The options available to Lagosians differ widely depending on income, social networks and leverage, but people of all income and status levels are engaged in a triangulated game of tactics which employs official process, traditional legitimacy, facts on the ground, and new options such as tax administration practices. To illustrate, we relate here narratives from two very different sectors of society, which show how contested and insecure property rights are across the spectrum, and how title and payment are only parts of a wider socially-embedded complex of rights and claims. The first involves a middle-class property developer buying land in the apparently clearly-structured formal market; while the second is a story of informal settlement-dwellers in Lagos’s lagoon-side waterfront communities.

A plot thickens

The first case concerns a middle-class professional couple who bought a plot in a government scheme at Oregun in Lagos mainland, where land formally acquired by government in 1993 had been subdivided and serviced for the purpose of residential property development. Purchasing from such schemes is supposedly the safest, most official way of accessing land, as conflicting claims from omo onile have (in theory) been settled by government. The couple bought a plot in 2000 and regularized it through Governor’s Consent and registration by 2006, including through acquisition of a C of O. They soon found, however, that the omo onile family claiming ownership were still contesting the government alienation and compensation in court. Despite their possession of all legally necessary title, the couple decided to pay again for the same land, this time as a sum to the omo oniles, ‘because if you don’t pay, they can make life hell for the construction process’.Footnote26

From 2006 they left the land undeveloped until 2014, during which time the omo oniles re-sold an area including their plot to another private developer, which the latter had fenced off, leaving their plot completely inaccessible. This developer refused to acknowledge the original sale and when a meeting was called to resolve the matter, refused to re-purchase it or to be re-located, and in addition had himself re-sold part of it as business premises to someone dealing in diesel. After a police intervention that resolved in the couple’s favour, using the new ‘Land-grabbers Act’ (discussed below) as threat, they instantly set to work on fencing their plot; but as this proceeded, a separate faction of omo onile came to ask for fees, using the name of the O’odua People’s Congress (OPC) militiaFootnote27 as leverage. These further demands were only deflected by displaying paperwork, by calling upon a joint police-military task force to maintain the peace, and by the couple using their status and connections to reach out to the state OPC leadership to threaten the local gang to back off. Even this, however, did not end the matter because the secondary purchaser of their land took them to court in a protracted dispute.

This series of incidents, like so many disputes, was rooted in government acquisition of land under the 1978 Act, and the traditional landholders’ belief that they had been inadequately compensated. In the lengthy hiatus between government acquisition and the release of land onto the formal market, these omo oniles had proceeded to sell parts of the land themselves onto third parties (some of whom subdivided and sold again), while the state ‘officially’ sold to the couple we interviewed. Such situations are not uncommon, and as land continues to change hands, the task of tracing the critical ‘illegitimate’ juncture that gave rise to multiple conflicting claims becomes ever more challenging. In this case, possession of a C of O did little to prevent the couple from court battles, forced entry, violent episodes and the cost of providing their own private security on the plot over an extended period. In other words, their ‘gold standard’ property right proved ‘thin’ in terms of its corresponding duty for others not to interfere, and in the end was just one among many other competing claims that the couple had to work actively, and constantly, to thicken through supplementary means.

This case of a single plot can function as a kind of ‘thick description’ exemplifying the complexities of land development in Lagos. We may note the diverse parties to the transaction: two private buyers, two factions of omo-onile, courts, one ethno-regional security militia, two federal security agencies (police and military), and two different Lagos state bureaucracies (Lands and the Surveyors’ Office), lawyers, builders and one sub-letting tenant. We may also note the strong role of historical grievance; or the productive nature of such a grievance, spawning a court case as renewable resource. And we can see clearly the mixed tactics to shore up property rights: courts, police, tradition, goodwill, threat, fait accompli.

Fighting on the beaches

Ebute Ilaje community lies on the lagoon on the edge of Lagos mainland, close to the University of Lagos’ waterside campus. It is a community of permanent concrete-block structures, with streets and drainage canals (see ). Its inhabitants are mainly Ilaje Yoruba-speakers inhabiting waterside communities around the lagoon, whose primary occupation is loading sand from the shallow lagoon bed into flat-bottom boats and selling it to the city’s booming construction industry. The community today has a youthful and educated leadership, linked into rights NGOs. Yet, until recently it had been engaged in a virtual civil war, with residents fighting against their own Baale (traditional ruler), who was trying to sell off its land. At least one community leader was killed before the Baale was effectively exiled, and now a de facto peace sees Ebute Ilaje today as both a community relatively far down the road to formal recognition, and one whose real estate remains a valuable and contested resource. The community’s security of tenure is based primarily on payments for waterfront usage to Nigeria’s National Inland Waterways Authority (NIWA).Footnote28

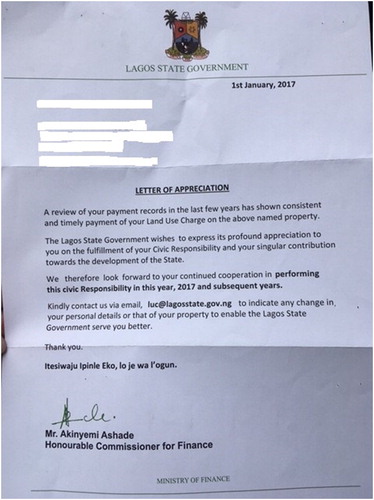

Unlike many waterfront communities in Lagos, many Ebute Ilaje residents (who are often landlords housing tenants in their own homes) are registered for the Land Use Charge.Footnote29 In fact, when asked about documentation proving their tenure, community members produced the official thank you letter sent by the Ministry of Finance to encourage continued LUC compliance (see ). Furthermore, in October 2016, property registration plaques were put in place for the first time, despite many properties in the community having paid the LUC for years. The plaques caused some consternation at first, as there was little information about what they were for, but in the period since appear to have bolstered the view among LUC payers that the payment of the tax constitutes some recognition of the legitimacy of their settlement.Footnote30 Yet at the same time as State authorities seem to have backed off from contesting their rights to live there, the government is pursuing a parallel means of making their tenure untenable; banning, beaching and then breaking up the sand-diggers’ boats on the pretext of environmental protection (see ).Footnote31

Just a little further north lies Ago-Egun community (see ), a less formalized settlement with a less educated (yet more historically united) population, and with a more positive history of negotiation with state government. The Egun people dwelling there have a difficult ethnic citizenship relationship to Lagos State; though they have historically lived on both sides of Nigeria’s international border, their historic fealty to the kings of Dahomey in present-day Benin Republic leads them to be routinely dismissed as ‘Beninois immigrants’ in official discourse. The inhabitants dwelled in stilt houses over the water until recently, when the Fashola administration told them to become land-dwellers. This they did by building their own land, creating foundations and streets from plastic rubbish, overlaid with sand, a mixture with a telltale springiness underfoot. And yet despite this clear creation of their own land – literally property created through labour as purely as Locke would have envisaged it – their tenure was very fragile and involved sub-letting through two separate systems. In the formal state system, their presence was tacitly acknowledged by the Federal Government’s NIWA as sub-tenants under the foreshore permission granted to neighbouring Ebute Ilaje, though this was highly tenuous and they had no official documents to evidence it. At the same time, in the traditional system, they also pay tribute rent to the Ashogbon chieftaincy family (who are in a very real sense omo onile, despite not being referred to as such), who control the dry land by which they are connected to the rest of Lagos (see ).

Relative to those in Ebute Ilaje, those in Ago Egun have much less documented formal security. The only document they were able to present to us to support their property claims was the incorporation certificate of their fishing co-operative association, which they saw as indicating propriety of their community as a government-recognized body in the face of accusations that their presence is temporary and recent.Footnote32 Significantly, in Ago Egun, no-one has even come to ask for payment of the LUC. Their single document was entirely unrelated to land and or property, yet it still offered them a degree of hope with regard to their tenure security, reinforced by the tributary traditional system.

Despite the complexities and specificities of these cases, some common characteristics emerge. One is that regardless of wealth, status and education, all of these actors use a mixed bag of tactics; formal and informal, documentary and bureaucratic as well as street action, to pursue their security of tenure – although this is not to ignore the important difference that in poorer areas the attempt to secure tenure is generally as a whole community, rather than as individuals. Another is that these cases show omo onile active in plural ways; resisting the state, but also colluding with it, evicting some buyers and tenants, but also guaranteeing (or attempting to guarantee) the rights of others. Equally clear is that the parties to these disputes can be diverse in the extreme: Federal government, State government, community NGOs and CBOs, indigene families, and a host of freelance actors purveying legal assistance, political leverage and street violence. This is not a neat bilateral portrait of state repression and counterpart popular resistance, but of actors ranging from foreign-educated lawyers to fishing communities engaging closely with state processes the better to gain a foothold, assisted by the positionalities inherent in Nigeria’s federal system, while also engaging with omo onile claims. And finally, the payment of state dues and fees including (but not limited to) the LUC has become a tactical manoeuvre, plurally playing into registers of security: by documentation, by fact on the ground, and by performed moral citizenship, in which tax payment is displayed alongside discourses such as legitimating histories and good security management as a reason to have property and residence rights recognized.

Situating taxation in Lagosian struggles to overcome radical insecurity

To better understand where the Land Use Charge sits in this medley of manoeuvres, payments and documentation deployed to fight off rival property claims and incrementally solidify property rights, it helps to look more closely at why people actually pay it. While literature on income tax reform in Lagos emphasizes how improved service delivery has been central to encouraging compliance, the same cannot easily be said of the LUC, which our interviewees – both rich and poor – rarely associated with tangible improvements in infrastructure and services. In part, community members saw their payment as an instalment paid upon mutual trust: ‘it’s our civic responsibility, we have done our part, now it’s time for government to do their part’.Footnote33 Indeed, in more marginal communities such as Ebute Ilaje, the coming of the LUC to their homes was widely perceived as bestowing governmental recognition on the community. One perceived function of paying the LUC is therefore to keep other claimants to the land off your back, whether the threat comes from omo onile groups, the State government itself, or both.

Although in strictly legal terms paying the LUC does not affirm ownership of the land in any way, this does not mean it has no significance as an indicator of property rights for the people who pay it. In fact, Lagos State land governance officials affirmed that people sometimes bring Land Use Charge payment receipts, as well as evidence of payment of ground rent or tenement rates in the past, as evidence of their land rights.Footnote34 Contrary to the official government perspective, then, members of communities such as Ebute Ilaje cling to the significance of LUC payments, enumeration plaques and ‘good citizenship’ letters (see above) as tokens of tenure security. Many interviewees affirmed that they do believe paying the LUC helps them in their efforts to avoid eviction. After the government’s decision to shut down their economically vital sand business, people in Ebute Ilaje continued to pay the LUC despite their anger, ‘because it should at least stop us from getting evicted’.Footnote35 This stance has some basis in precedent due to an eviction from Badia informal settlement in 2012, where – citing a link between the eviction and an ongoing World Bank project as justification – a group of people successfully took legal action that resulted in LUC receipts being used as proof of entitlement to compensation.Footnote36

Our observations on these strategic uses of LUC were supported by the founders of the Land Records Company, who noted that even while rolling out the system of property tax registration, two things happened. First, registrants pre-empted the additional value of LUC in relation to property rights: landlords seeing a tenant’s name on the LUC demand would call LRC to complain, alleging that the company was trying to reassign their property (and lest this fear seem irrational, bear in mind the slow mutation of tenancy to ownership which Mann records in early Lagos). Secondly, because of the additional costs and complications of obtaining a C of O, LRC employees began to note cases of the LUC demand notice itself being touted as a matter of record: a claimed de facto property right.Footnote37

Conclusions

In theory, since the reforms of the Tinubu/Fashola era, property rights in Lagos should be a straightforward affair: ownership rights are vested exclusively in a C of O, which all legitimate owners can acquire and which obliges others not to interfere; LUC payments indicate (at most) legitimate occupancy or tenancy; and any informal payments to traditional claimants may bolster personal security and social wellbeing, but have nothing to do with rights. Yet this apparently rational formulation fails on every count. As our example of the wealthy middle-class couple shows, even possession of a C of O does not prevent contesting claims, which are often violent and equally grounded in discourses of legitimacy. Thus, although there are clearly differing degrees of vulnerability to eviction and expulsion – as evidenced by the ongoing, egregious evictions on the Lagos waterfronts since 2016Footnote38 – tenure insecurity is something that virtually everyone in Lagos has in common. Meanwhile, the distinction between occupancy and ownership is not as clear as rationalist discourses would have it (the fact the gold standard of ownership is called a ‘Certificate of Occupancy’ is perhaps telling here). Given the extent to which the ongoing legitimacy of the 1978 Decree is contested, all supposed property rights that flow from actions taken under this law are thrown into question – and indeed, given the mismatch between postcolonial formal legal jurisprudence on one hand, and traditional idioms of legitimacy on the other, sometimes all law itself is in question. In the fluid field of play of ownership, rights and claims, payments such as the LUC – and indeed any intervention which provides state recognition of occupancy – proves of utilitarian value beyond what its designers imagined, moving the status of an occupant closer to something else. So we are finally able to make better sense of our colleague’s mother and her insistence on tax receipts; in a context of generalized property insecurity, Lagosians have latched on to the regulatory and recording potential that tax certification offers as a way to establish a paper trail which also documents their citizenship, a way to make property claims ‘thicker’ and more provable.

Also remarkable is the fact that in Lagos’ dynamic and insecure property world, the developers fighting omo onile in one place often are the omo onile fighting the state in another. Thus, the middle-class couple cited above are fighting an entirely separate court case against Lagos State regarding government alienation of family lands in Lagos Island, for which they believe they were inadequately compensated during the relocations of the mid-twentieth-century. Attempting to exert rights based on their own historical grievances of land alienation for development, one of them wryly noted that ‘sometimes we too exhibit omo onile behaviour’.Footnote39 The contestation we document, then, is not as simple as a picture of marginalized people existing in a realm of ‘traditional’ tactics, customary claims, social codes and street-based action, while educated and empowered people use formal tactics, legal rights and access to the state to dispossess and accumulate. Instead, everyone is deploying their mixed bag of social, legal, economic and political assets to lodge a stake in various domains and then leverage it. Neither does this research depict a process of informal payments becoming formalized into taxes over time: rather it is a story of interpenetration. The informal is in the midst of the formal sphere, mediating its practices, such as the occasional negotiability of Land Use Charge rates for sympathetic cases from ‘good Lagosian families’. And at the same time, formalization has come to meet the informal in the ‘Land-Grabbers’ Act’ passed in 2016, which in its Section 11 actually legalizes omo onile payments of an unspecified ‘reasonable’ amount – thus ushering in legal recognition of some omo onile rights over property for the first time, in the very law that was meant to limit their activity.Footnote40 In this context, all claims, alliances and registers of rectitude and legitimacy are fair and useful game.

What the majority of de Soto’s critics rarely challenge is the idea that a formal property right established in law is itself an entity; a clearly defined object which either exists or doesn’t and is distinct from a mere claim to a right. Our analysis of Lagos shows however that even in the formal sphere, a property right is inherently processual and multidimensional. For a property right to exist as a social fact requires a bundle of qualities to be effectively evident in sufficient degree – legal title, social legitimacy, active enforceability and material presence on the ground. In this conception, legal title is just one possible attribute of a property right, and is itself laced with informal process in terms of its acquisition and interpretation, rather than being the negation of informality itself. Moreover, rights themselves will always remain thin unless they are backed up by deeper socially-legitimated claims. While this is in some regards obvious, what Lagos reveals is the range of ways in which people in some contexts have to innovate and work to thicken these claims, At its most secure, property might involve a freehold with Certificate of Occupancy issued and collected, a long-established and wholly-owned building on the site, and no traditional landholder, family or governmental claims against it. At the most insecure it could be a bundle of Land Use Charge receipts or a pink copy of a building plan of a hastily-built shared-ownership structure, built on marginal or even self-created land leased from a chieftaincy family via a worker’s cooperative, besieged by rival claims from State and Federal governments with stakes in recognizing or denying its legitimacy. And for most people, it could be virtually any combination in between, as they seek to overcome the enduring and unsettling provisionality that living amid radical insecurity engenders (Simone, Citation2004). Viewed as an extreme case in terms of the radical nature of property insecurity, Lagos illuminates aspects of property with much broader implications; aspects that are often obscured by legalistic norms and long-embedded assumptions of the capitalist paradigm.

Property rights in Lagos are therefore hard to distinguish from claims but are also, in some sense, more true to the spirit of Locke – rooted in use, possession, and indeed labour on multiple fronts – than to contemporary definitions that suggest they are based on rational principles and conferred by the stroke of an administrative pen. The prevailing idea that they are quantifiable, unlike other forms of rights (O'Kane, Citation1997), is revealed as a fiction in Lagos: the reality is that they are simply claims that can only be realized more solidly as rights over time and with substantial effort and resources. As a claimant, once you have a start, your work is to deepen them, entrench them, solidify them; effectively a system of rights by instalment. Interpreting property rights as non-digital in this way underlines the importance of analysing their ‘analogue’ character, and of understanding the strategies and tactics through which people attempt to secure rights by thickening underlying claims: a process that in Lagos we have shown to be wide open to innovative action.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers, journal Editor and Editorial Board, two anonymous reviewers from the International Centre for Tax and Development, and Ryan Powell for their helpful and insightful comments on earlier drafts. In addition we want to thank Abiola Sanusi and Bunmi Ibraheem, Bukola Bolarinwa, ‘N.F.A.’, Mr Sunday Olamide, Nicole Wilson, Hakeem Bishi, Mojisola Rhodes, Lagos State Government, University of Lagos Department of Urban Planning, and Justice and Empowerment Initiative (especially the Real Megan Chapman), as well as the residents of all communities visited for their invaluable help during the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Tom Goodfellow is a Senior Lecturer in Urban Studies and Planning at the University of Sheffield. His research concerns the comparative political economy of urban development in Africa, with particular interests in the politics of urban informality, urban conflict and violence, land value capture, urban infrastructure and housing. He has conducted research in Uganda, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Tanzania. He is co-author of Cities and development (Routledge, 2016) and sits on the Editorial Board of African Affairs.

Olly Owen is a Research Associate at Oxford University’s African Studies Centre and Institute for Social and Cultural Anthropology. A political anthropologist of West Africa, he specializes in studies of governmental institutions in practice, examining policing, taxation and infrastructure. He has also conducted historical work on Nigerian soldiers in WWII. He has co-edited a 2017 book Police in Africa: The street-level view and been published in journals including Africa, African Affairs, Development and Change and Development Policy Review. He currently acts as Research Director for the Nigerian Tax Research Network, supported by the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex and also works with The Policy Practice.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interview with legal officer for community NGO, 16 February 2017.

2 This also has implications in increasing the value of those rights. Although outside the scope of this paper, this points us to a possible alternative theorisation of a ‘property ladder’. Rather than its everyday meaning in countries such as the United Kingdom and United States, which refers to the strategy of amassing capital and credit to buy into and progressively trade upwards upon a rising speculative market (Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2018), this alternative ‘property ladder’ is about making existing claims more solid and realisable in value.

3 The city area of today also encompasses older previously independent towns such as Badagry and Ikorodu with their own traditional landholders.

4 Nigeria’s constitution recognises three levels of territorial administration: federal, state and local governments.

5 http://www.nigeria-law.org/Land%20Use%20Act.htm. Accessed 10 July 2017.

6 Interview with member of traditional landowning family, 5 October 2016.

7 These are in turn underwritten by a linkage between land ownership, identity and belonging which mean that someone’s land ownership may have deep implications for their citizenship, and vice versa.

8 Interview with LIRS Board Secretary Jimi Aina, 6 October 2016. See Goodfellow and Owen (Citation2018) for a full discussion of the tax reforms and their consequences.

9 This figure was provided by a former LUC official interviewed on 7 October 2016.

10 Such appeals and bureaucratic acquiescence with them also fundamentally blur any attempted neat division between ‘civic’ and ‘primordial’ modes of citizenship after Ekeh (Citation1975).

11 Interview with LUC tribunal representative, 17 February 2017. A draft law, introduced, then withdrawn and revised in early 2018 embeds this possibility even further.

12 There are five different routes to obtaining it, depending on the origin of the land claim, but we do not detail these here due to space considerations.

13 Figures from Lagos State Bureau of Lands.

14 Property developers, often concerned about costs and speed, may choose to pay official rates or to pay bribes to officials; the intelligent and well-financed may even choose to do both, speeding up development free from interference while also obtaining the necessary paperwork needed. Interview with property developer, Ikoyi, 3 October 2016.

15 For a history of the evolution of the Omo Onile, see Akinyele (Citation2009).

16 ‘Omo onile: Miscreants who are as powerful as the state’, Nigerian Tribune, 16 July 2016. http://www.tribuneonlineng.com/omo-onile-miscreants-powerful-state/. A similar phenomenon is known as ‘land guards’ in Accra, Ghana.

17 Interview with land official, 5 October 2016.

18 Interview with Lagos property lawyer, 30 September 2016.

19 Interview with indigenous land claimants, 5 October 2016.

20 Interview with indigenous land claimants, 5 October 2016. Interviewees dated this phenomenon back around a decade.

21 Interview with NGO representative, 30 September 2016.

22 Interview with NFA, 5 October 2016.

23 Although perhaps not in terms of their perceived legitimacy; as one real estate developer put it, ‘You pay taxes in the UK to benefit the poor, here we pay an idiot’. Interview with property developer, 3 October 2016.

24 Interview with indigenous land claimants, 5 October 2016.

25 Interview with indigenous land claimants, 5 October 2016. We also see the invocation of the discourse of moral citizenship in other forms of land claim; thus in order to more easily evict waterfront communities, government officials may demonise them as dens of armed robbers, while in contrast dwellers in such communities were keen to emphasise to us their law-abiding nature as part of their claim to continued tenure.

26 Interview with middle-class lawyer, 30 September 2016. Disruptive tactics can include harassing or intimidating contractors or workers, rendering the site deliberately insecure and vulnerable to theft or vandalism, or creating physical obstructions to access. See also Agboola et al. (Citation2017) and Ezeanah (Citation2018) on Benin City.

27 See Nolte (Citation2007) for a discussion of this group.

28 Although the community is in Lagos State, Nigeria like the UK vests rights to the foreshore in national government.

29 Tax collectors come once a year to individual houses to collect the payment in this kind of settlement, where typically people pay around 2,000–5,000 Naira depending on the nature of their property, with some exceptional properties paying up to 16,000.

30 Interview with Ebute Ilaje community representative, 14 February 2017.

31 As in colonial practice (see Ahire, Citation1991) both environmental and security framings are invoked in the service of evicting slum-dwellers.

32 This echoes broader findings from research conducted by others in waterfront communities, which found that people use documents ranging from bills for basic utilities, to television and radio licenses, to informal documents recording property transfers in their efforts to build a claim to their land. Interview with legal NGO, 9 February 2017.

33 Interview with member of Ebute Ilaje community, 14 February 2017.

34 Interviews with Lagos State land official, 13 February 2017 & with LUC tribunal representative, 17 February 2017.

35 Interview with property owner, Ebute Ilaje, 14 February 2017.

36 It may also encourage the uptake of LUC as a pre-emptive strategy, just as many Nigerians register to vote ‘just in case’ the voter card subsequently becomes required for some other identity confirmation or allocation process.

37 Omodele Ibrahim ‘Property tax: An effective economic development tool’ – presentation at Nigeria Tax Research Network conference, Abuja, 13 September 2017.

38 See for example: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/may/31/destroyed-community-lagos-nigeria-residents-forced-evictions-demolitions. Accessed 25 September 2017.

39 Interview with lawyer, 5 October 2016.

40 The official title of this law is ‘A law to prohibit forceful entry and illegal occupation of landed properties, violent and fraudulent conducts in relation to Landed Properties in Lagos State and connected purposes’, gazetted 9 September 2016. It was promoted to the public primarily as a way to stop the ‘social nuisance’ of entrepreneurial omo-onile activities and therefore catered primarily to an intended audience (and electorate) of putative property developers and home improvers.

References

- Agboola, A. O., Scofield, D. & Amidu, A. R. (2017). Understanding property market operations from a dual institutional perspective: The case of Lagos, Nigeria. Land Use Policy, 68, 89–96.

- Ahire, P. T. (1991). Imperial policing: The emergence and role of the police in colonial Nigeria 1860-1960. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Akinyele, R. T. (2009). Contesting for space in an urban centre: The Omo Onile syndrome in Lagos. In F. Locatelli & P. Nugent (Eds.), African cities: Competing claims on urban spaces (pp. 109–133). Leiden: Brill.

- Amanor, K. S. (2010). Family values, land sales and agricultural commodification in South-Eastern Ghana. Africa, 80(11), 104–125.

- Babawale, G. K. & Nubi, T. (2011). Property tax reform: An evaluation of Lagos State land use charge, 200. International Journal of Law and Management, 53(2), 129–148.

- Barnes, S. (1986). Patrons and power: Creating a political community in Metropolitan Lagos. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Bekker, S. & Fourchard, L. (Eds.). (2013). Governing cities in Africa: Politics and policies. Pretoria: HRSC Press.

- Besley, T. & Persson, T. (2009). The origins of state capacity: Property rights, taxation, and politics. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1218–1244.

- Bierschenk, T. & Olivier de Sardan, J.-P. (2014). States at work: Dynamics of African bureaucracies. Leiden: Brill.

- Bodea, C. & Lebas, A. (2016). The origins of voluntary compliance: Attitudes toward taxation in urban Nigeria. British Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 215–238.

- Bromley, D. (2008). Formalising property relations in the developing world: The wrong prescription for the wrong malady. Land Use Policy, 26(1), 20–27.

- Cheeseman, N. & de Gramont, D. (2017). Managing a mega-city: Learning the lessons from Lagos. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 33(3), 457–477.

- Cole, D. H. & Grossman, P. Z. (2002). The meaning of property rights: Law versus economics? Land Economics, 78(3), 317–330.

- Cousins, B., Cousins, T., Hornby, D., Kingwill, R., Royston, L. & Smit, W. (2005). Will formalising property rights reduce poverty in South Africa’s ‘second economy’? Questioning the mythologies of Hernando de Soto. PLAAS Policy Brief No. 18.

- de Soto, H. (2000). The mystery of capital. London: Bantam.

- Deininger, K. W. (2003). Land policies for growth and poverty reduction. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Earle, L. (2014). Stepping out of the twilight? Assessing the governance implications of land titling and regularization programmes. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(2), 628–645.

- Ekeh, P. P. (1975). Colonialism and the two publics in Africa: A theoretical statement. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 17(1), 91–112.

- Ezeanah, U. (2018). The delivery of quality housing in Benin City: The influence of formal and informal institutions. Doctoral dissertation. University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. Retrieved from http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/19805/

- Forrest, R. & Hirayama, Y. (2018). Late home ownership and social re-stratification. Economy and Society, 47(2), 257–279.

- Gilbert, A. (2002). On the mystery of capital and the myths of Hernando de Soto: What difference does legal title make? International Development Planning Review, 24(1), 1–19.

- Goodfellow, T. & Owen, O. (2018). Taxation, property rights and the social contract in Lagos. ICTD Working Paper No. 73. Brighton: Institute for Development Studies.

- Hendrix, S. E. (1995). Myths of property rights. Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 12(1), 79–95.

- Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mann, K. (1991). Women, landed property, and the accumulation of wealth in early colonial Lagos. Signs, 16(4), 682–706.

- Marshall, R. (2009). Political spiritualties: The pentecostal revolution in Nigeria. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Marx, C. (2009). Conceptualising the potential of informal land markets to reduce urban poverty. International Development Planning Review, 31(4), 335–353.

- Musembi, C. N. (2007). De Soto and land relations in rural Africa: Breathing life into dead theories about property rights. Third World Quarterly, 28(8), 1457–1478.

- Nolte, I. (2007). Ethnic vigilantes and the state: The Oodua People's Congress in southwestern Nigeria. International Relations, 21(2), 217–235.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. & Stilwell, F. (2013). Security of tenure in international development discourse. International Development Planning Review, 35(4), 315–333.

- O'Kane, S. G. (1997). What right to private property? Economy and Society, 26(4), 456–479.

- Payne, G. (2001). Urban land tenure policy options: Titles or rights? Habitat International, 25(3), 415–429.

- Pratten, D. (2013). The precariousness of prebendalism. In W. Adebanwi & E. Obadare (Eds.), Democracy and prebendalism in Nigeria: Critical interpretations (pp. 243–258). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schmid, A. (1999). Government, property, markets … in that order … not government versus markets. In N. Mercuro & W. J. Samuels (Eds.), The fundamental interrelationships between government and property (pp. 237–241). London: Routledge.

- Simone, A. M. (2004). For the city yet to come: Changing African life in four cities. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Toulmin, C. (2009). Securing land and property rights in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of local institutions. Land Use Policy, 26(1), 10–19.

- Van Gelder, J. L. (2010). What tenure security? The case for a tripartite view. Land Use Policy, 27(2), 449–456.

- Woodruff, C. (2001). Review of de Soto’s ‘The mystery of capital’. Journal of Economic Literature, 39(4), 1215–1223.