Abstract

This paper explores the relationship between labour market dualization, insecurity and low fertility, through a case study of South Korea, an extreme case of ultra-low fertility where the total fertility rate fell to 0.84 in 2020. It is argued that the long-term nature of the insecurity associated with dualization, as well as its impact on people’s perceptions of present and future insecurity, mark dualization out as a particular phenomenon whose impact on fertility current demographic approaches struggle to fully understand. Rather than restricting the focus to the education-employment transition, we show how permanent insecurity in highly dualized labour markets depresses fertility.

1. Introduction

In recent decades fertility rates have declined substantially across the developed world to the extent that since the 1970s the majority of OECD countries have experienced below replacement rate levels of fertility (that is, total fertility rates (TFRs) of 2.1). In some countries (such as France, Sweden and the United States) fertility rates are only moderately below replacement levels, yet a significant number of other countries (especially in southern Europe and East Asia) have recorded ‘lowest-low’ fertility rates (TFRs of 1.3 or below), which are typically perceived as pressing demographic challenges by governments in these countries. While many of these countries have seen a recent uptick in TFRs from their nadir in the late-1990s or early-2000s, South Korea stands out as an extreme case of persistently low fertility. Indeed, Korea has been experiencing lowest-low fertility since 2001 (OECD, Citation2020).

Addressing this issue has been a political priority in Korea since the early 2000s and has led to significant policy changes, most dramatically the path-departing expansion of work-family policies (Fleckenstein & Lee, Citation2017a). This mirrors a general trend across the OECD of childcare and parental leave expansion and reflects international consensus that improving the possibilities for women to reconcile employment and family responsibilities is key to raising fertility rates (OECD, Citation2017a; Olivetti & Petrongolo, Citation2017). This consensus is based on demographic research arguing that low fertility rates result from an ‘incomplete gender revolution’, in which gender equity has been achieved in the public institutions of education and employment but not in the private sphere of the family, where women still undertake the majority of unpaid labour, particularly childcare (e.g. Anderson & Kohler, Citation2015; Esping-Andersen & Billari, Citation2015; Goldscheider et al., Citation2015; McDonald, Citation2000a). Yet, such interventions informed by demographic gender equity theory do not appear to be impacting Korea’s fertility rates, which are continuing to decline; indeed 2020 saw a record low of 0.84, considerably below other low fertility countries (Statistics Korea, Citation2021).

Korea’s ultra-low fertility thus presents an intriguing puzzle for demographic research: it is simultaneously an extreme case of a general pattern of low fertility rates across the OECD and one that appears resistant to interventions that are predicted to raise fertility rates. To help explain this, this paper highlights an aspect of Korean society that is largely overlooked in the demographic literature: labour market dualization; that is, increasing polarization in the labour market between a shrinking core of well-remunerated and well-protected insiders and a growing number of people in precarious employment at the margins of the labour market. While dualization has received much attention in comparative political economy, research into its impact on fertility is scant. Indeed, in the context of generally rising female employment, the demographic literature tends to take gender equity in the labour market for granted and examines intra-household behaviours as the key to low fertility. This presents a striking blind spot in these theories, especially given dualization is a gendered process in which women generally face higher risks of becoming labour market outsiders, and the associated lack of income and security.

We therefore propose to extend dualization to the study of ultra-low fertility. It is argued that the long-term nature of the insecurity associated with dualization, as well as the importance of people’s perceptions of present and future insecurity, mark dualization out as a particular phenomenon whose impact on fertility is underappreciated. Taking a macro-sociological approach, bolstered with attitudinal data to highlight the importance of perceptions, we argue that dualization has depressed fertility in Korea in three ways. First, and in agreement with much of the demographic literature, we argue that it leads people in their twenties to prioritize skill formation and postpone family formation. However, we find that pressures from dualization not only lead to childbirth postponement because of temporary insecurity in the education-employment transition (Blossfeld et al., Citation2006) but to smaller family sizes and to some opting to forego parenthood altogether. Instead of reducing insecurity to a temporary phenomenon, in the education-employment transition for instance, we argue that insecurity has become a permanent feature of people’s working lives in highly dualized labour markets – affecting not only the growing numbers of people in precarious jobs across different ages but also labour market insiders increasingly worry about losing insider employment. Thus, suggestions of clearly separated labour markets with secure insiders and insecure outsiders (e.g., Rueda, Citation2014) have become increasingly questionable in highly dualized societies where insecurity crosses these boundaries, as the extreme case of Korea demonstrates. Second, dualization is gendered, which manifests itself, for example, in the gender pay gap and women’s over-representation at the margins of the labour market. Hence, far from the emancipatory experiences in the workplace suggested by gender equity theories in the demographic literature, the emergence of an ‘adult worker model’ (Lewis, Citation2001) disproportionally pushes women into outsider jobs that contribute little to gender equity. This gendered nature of dualization – including the misalignment of labour market institutions and women’s views on work and family – increases women’s opportunity costs of having children to extreme levels, and thus further depresses childbirth. Third, the increasingly competitive nature of dualized labour markets place great pressure on families to invest significant sums in their children’s education, in order to give them a chance to secure insider employment. The permanent nature of insecurity can solidify such behaviour into social norms, which can dramatically increase the cost implications of having a child.

Korea provides an apposite case for such an examination because it represents an extreme case both of ultra-low fertility and of a dualized labour market. As such, the relationship between dualization and fertility is likely to be most stark in Korea. Nevertheless, the relevance of the argument is not limited to this case; each of the features of dualization highlighted as negatively impacting on fertility rates are evident and growing across the OECD. Dualization in labour markets and the polarization of employment have been widespread and growing trends (Emmenegger et al., Citation2012; Rueda, Citation2014). Increasing rates of tertiary education, skills acquisition and the postponing of family formation are also prevalent among many OECD countries (OECD, Citation2019a, Citation2021). Increased perceptions of inequality are also common to many high-income societies, in the context of growing labour market instability, ‘casualisation’ of employment, retrenchment in social protection, and the shrinking influence of labour unions (OECD, Citation2015). Finally, private education expenditure is a feature across OECD countries. While Korea is widely recognized as an extreme case of so-called ‘shadow education’, excessive private tutoring is widespread in many Asian countries, and is gaining greater prominence in Europe too (Bray, Citation2021). Korea’s experience therefore reveals how fertility patterns interact with dualization and also provides a warning for other OECD countries of how these interactions, left unaddressed, can lead to equilibria that are very difficult to break down.

The article proceeds as follows: the next section maps Korea’s ultra-low levels of fertility, emphasizing that postponement of family formation is only one of a number of trends impacting on the overall fertility rate. Subsequently, the demographic literature is explored to situate our argument in previous work. This section, drawing on labour market research on insecurity, demonstrates that the insecurity provoked by highly dualized labour markets has ‘scarring effects’ that last well beyond the education-employment transition discussed in the demographic literature and therefore do not merely postpone childbirths but can also prevent them altogether. Moreover, it argues that in dualized labour markets these effects are not confined to those who themselves have experienced outsider employment, but perceptions of permanent insecurity have proliferated among those in insider jobs and indeed their partners too, because the consequences of losing that status are both severe and widely understood. The remainder of the paper refocuses on Korea to elucidate each of the three ways in which dualization relates to low fertility. The paper concludes with a discussion of policy implications of these arguments.

2. The mapping of ultra-low fertility: South Korea in comparative perspective

The trajectory of Korea’s TFR matches most OECD countries over the last 50 years, falling from high rates in the 1970s to below replacement levels in the 1980s and continuing to fall in the 1990s. However, Korea’s fertility decline has been more extensive than in any other OECD country, marking Korea out as an extreme case. Korea’s TFR in 2018 was at 0.98, the first time that any OECD country has seen its TFR dip below one, and has since dropped further to 0.84 (Statistics Korea, Citation2021). Although TFRs in other low-fertility countries have recovered somewhat since the 2000s, we still observe great difficulties with reaching and remaining in the so-called demographic ‘safety zone’ (that is, TFRs higher than 1.5) (McDonald, Citation2006).

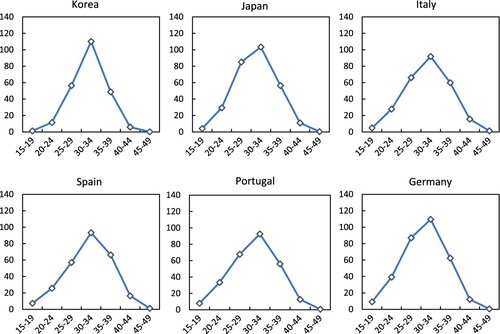

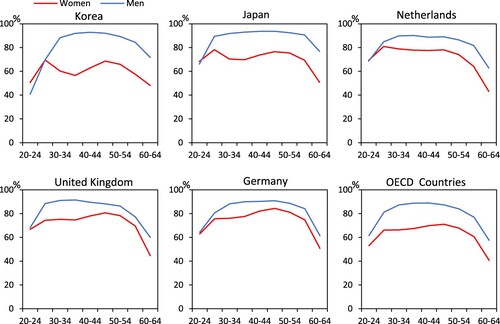

Studies of lowest-low fertility countries have found that much of the nadir at the turn of the millennium was due to tempo effects from childbirth postponement and some of this is likely to be compensated for by rises in quantum fertility among women in their thirties (Goldstein et al., Citation2009; Myrskylä et al., Citation2009). However, Korean women in their twenties do not merely postpone childbirth to a greater extent than in other countries, which can be seen in the fact that the fall in the fertility rate among women aged 25–29 has been more dramatic since 2000 than in any other OECD country, but this is not being compensated for by births among older women. As demonstrates, while Korea’s birth rates among women aged 30–34 are not particularly low, Korea’s ‘fertility triangle’ is rather sharp due to low birth rates among both the adjacent age groups. Also, an increasing number of Korean women remain unmarried and childless: since 1990 the marriage rate has fallen by 41 per cent, one of the largest drops in the OECD, which is significant for fertility in a country in which only 2 per cent of children are born to unmarried parents (OECD, Citation2021). Smaller families and increasing childlessness in Korea produce a continuous, negative trend in the TFR, despite a positive impact from slowing tempo effects (Choe & Retherford, Citation2009; Yoo & Sobotka, Citation2018).

Figure 1 Birth rates (births per 1,000 women) by women’s age in selected countries, 2016.

Source: OECD (Citation2021)

With the objective of reversing these fertility trends, successive Korean governments have been committed to a ‘path shift’ in work-family policy, most notably free childcare provision (Fleckenstein & Lee, Citation2017a; Lee, Citation2018). However, Korea’s fertility rate has continued to fall, in spite of the international consensus that reconciling employment and childcare responsibilities is an important tool for increasing fertility rates (OECD, Citation2017b; Olivetti & Petrongolo, Citation2017). The next section examines gender equity theories which underpin this consensus in addition to research emphasizing links between temporary insecurity and lower fertility rates. It argues that the impact dualization may be playing in relation to fertility is not sufficiently recognized in the demographic literature.

3. Dualization, insecurity and low fertility

The dramatic fall in fertility rates across the OECD since the 1970s have prompted a preoccupation in the demographic literature with the drivers of fertility behaviour (see Balbo et al., Citation2013). Underpinning this work is the predominant notion that the decision to have a child is a rational one, based on cost–benefit analysis (e.g. Becker, Citation1981). A feature of the literature is interpreting macro trends through the prism of micro-calculations of costs and benefits, with the implication that policy interventions should therefore be focused on reducing costs or increasing incomes. As the literature has developed, a broader range of factors have been considered as inputs to fertility decisions, taking into account criticisms that the assumptions of simple rational choice models omit key factors, such as changing values and norms, and they therefore struggle to explain recent fertility trends, especially the cross-national correlation between higher female employment levels and higher fertility rates (e.g. Castles, Citation2003). More recent theories highlight the mediating capacity of national institutional structures in fertility decisions, in particular through reducing the conflict between employment and family life for women. McDonald’s (Citation2000a) gender equity theory argues that fertility remains low in countries in which gender equity in individual-oriented institutions (such as higher education or the labour market) is not matched in family-oriented institutions and the family itself. Moreover, fertility rates are predicted to recover, or at least stabilize, in countries where ‘dual-earner/dual-carer’ families are increasingly common, with gender equity in the family representing the second half of the ‘gender revolution’ (e.g. Anderson & Kohler, Citation2015; Esping-Andersen & Billari, Citation2015).

Given the focus on the imbalance in gender equity between employment and the family, this literature understandably highlights the crucial role that work-family policies can play in helping women combine employment and family responsibilities and also in encouraging men to take on a greater proportion of the latter. With the exception of a concern for ‘family-friendly’ employment practices, much of the focus of this literature is therefore on the family, with relatively little attention paid to the labour market; equity in employment appears to be largely assumed, based on aggregate employment rates, and the focus is on increasing gender equity within families. Yet, a key feature of post-industrial society is growing employment insecurity, featuring rising levels of precarious, non-standard employment, and, relatedly, increasing dualization in labour markets between insiders and outsiders, with women forming a large proportion of the latter (Emmenegger et al., Citation2012). It thus appears reasonable to expect that labour market dualization has a profound impact on individuals’ decisions in several areas including family formation. Given the cost–benefit calculation assumed to be at the base of fertility decisions, it is remarkable that the fertility literature has not focused more on the role of dualization and the changing nature of labour markets. In fact, theorists in this literature tend to see labour market deregulation and the proliferation of non-standard employment as positive factors in that they provide women with flexible employment that can be more easily combined with childrearing. For example, Brinton and Lee (Citation2016) argue that employment protection for labour market insiders may depress fertility by disadvantaging women who want to work flexibly (in other words, women are forced to choose between careers or children) and by reducing the availability of stable jobs for young people, leading to postponement of fertility. This chimes with a strand in the literature which views strong labour market protection and unions as detrimental to fertility rates (e.g. Adserà, Citation2005; Bertola et al., Citation2002).

This is not to argue that there has been no interest in insecurity in the demographic literature. Research on the effects of insecurity on fertility behaviour has been prompted by drops in fertility in post-socialist eastern Europe during the transition from planned to market economies (e.g. Eberstadt, Citation1994) and in southern Europe, which is characterized by very high levels of youth unemployment and fragmented labour markets (e.g. McDonald, Citation2000b). A third strand of interest comes from those investigating the impact of globalization on fertility (Blossfeld et al., Citation2006). The assumption in these literatures is that insecurity is a temporary feature, either produced by an economic shock, or one that affects people primarily at the education-to-employment transition and therefore has an indirect effect on fertility by leading young people to postpone family formation in favour of skill formation (e.g. Adserà, Citation2004; Kreyenfeld et al., Citation2012; Modena et al., Citation2014). However, given that dualization is an ongoing process, the resulting insecurity is better conceptualized as a permanent situation for a large proportion of the population, potentially affecting them throughout their working lives. While it is undoubtedly the case that it can lead to postponement of fertility, it is not unreasonable to assume that insecurity associated with dualization has a direct negative impact on fertility decisions throughout one’s reproductive years. Moreover, drawing on the labour market research on insecurity, it is argued that these long-term effects are not limited to those at the margins of the labour market, as the possibility and consequences of losing employment also affect insiders’ perceptions of security.

These effects of insecurity are absent from the fertility literature. This could be because of the rational choice underpinning in much of the literature: the assumption that fertility decisions are made with full knowledge of the potential costs and benefits of children, when in reality individuals can only evaluate perceived costs and benefits (Gauthier, Citation2007). The decision to have a child necessitates a long-term perspective, involving making assumptions about the future which one cannot know for certain. This chimes with labour market research on insecurity, which has shown that perceptions of job insecurity are multifaceted and only partially related to objective levels of insecurity. In their seminal work, Clark et al. (Citation2001, p. 221) have shown that ‘life satisfaction is lower not only for the current unemployed (relative to the employed), but also for those with higher levels of past unemployment’, and explaining this observation they point to the lasting psychological impact of unemployment – ‘scars’ because people continue to be ‘scared’, even though they might appear to have, in objective terms, recovered from their earlier job loss. Lübke (Citation2021), for instance, demonstrates that job insecurity has a significant impact on self-assessed health for all age groups in Germany, including young people; and Kim and Kim (Citation2018) show an association between job insecurity and depression. With a very similar impetus, Kim et al. (Citation2006) point to irregular employment contributing to poorer mental health, which affects women to a greater extent than men (controlled for socio-economic status and health behaviours). In terms of gender differences, Mauno and Kinnunen (Citation2002), drawing on Finnish survey data, show that women experience more uncertainty about their jobs than their partners, and women’s job insecurity is affected more strongly by poor economic conditions. Using Italian data, Bonanomi and Rosina (Citation2022) not only show that the experience of NEET (not in employment, education or training) affects well-being, but also that well-being becomes a predictor of changes in occupational status. More dissatisfaction with one’s life situation is associated with a greater risk of the experience of NEET in the future, while greater reported well-being is associated with a greater chance of escaping NEET. Similarly, Klug et al. (Citation2019) provide evidence from Germany that temporary contracts – a key feature of labour market dualization – facilitate life trajectories of higher perceived job insecurity. In other words, young people’s subjective perceptions appear to leave scars. It might thus not surprise that Ralston et al. (Citation2022), using Scottish census data, and Helbling and Sacchi (Citation2014), studying Swiss youngsters with vocational qualifications, demonstrate long-term scarring that is associated with the experience of NEET.

Building on this research that stresses the importance of perceptions of future prospects and drawing on German data, Knabe and Rätzel (Citation2011) suggest it is not necessarily an actual experience of unemployment but the fear of unemployment that reduces life satisfaction. Controlling for future expectations, they find that much of the unemployment effect disappears. This is crucial because in a highly dualized labour market, the negative effects of losing employment are both potentially high and widely understood, therefore increasing anxiety related to keeping one’s job; and indeed considerable anxiety in reproductive years could be expected, as the prospect of either procuring relatively secure insider employment or maintaining it once secured has become ever more uncertain. Here, it is important to underline that comparative research indicates that such effects are mediated by labour market and welfare institutions (see for an overview, Chung & Mau, Citation2014). For instance, strong social protection for the unemployed can serve as an important mechanism reducing anxiety caused by the fear of job loss (Hipp, Citation2016). Origo and Pagani (Citation2009) have found that temporary workers’ level of insecurity varies according to their perceptions about not only the state of the wider economy (i.e. the perceived risk of job loss) but also the welfare state (i.e. perceived social security). Further, research on insecurity and dualization suggests that countries with highly dualized labour markets lack the corporatist institutions with strong labour unions which provide insiders with a greater sense of job security (Chung, Citation2019).

The intertwined phenomena of scarring and scaring reveal the fundamentally subjective nature of insecurity, relating to one’s perceptions of one’s current and future situation. In the context of a highly dualized labour market therefore, the predominance of insecurity means that fertility decisions are necessarily broader than simply weighing up costs versus income, as rational choice approaches in demography suggest. Some research demonstrates this link: evidence from labour market deregulation in Italy found that the effects of employment insecurity on childbearing intentions varied according to women’s future prospects; for women with low income and education, high employment insecurity made little difference to their intentions, while for women with high income and education levels, high employment insecurity led to the postponement of childbearing (Modena et al., Citation2014). Similar results have been found in eastern Germany in terms of economic uncertainty (Kreyenfeld, Citation2010). These results imply that insecurity relates to fertility not only through its impact on income but also in terms of how it affects perceptions of future prospects. In other words, in a highly dualized labour market where the consequences of outsider employment are widespread and obvious, individuals may fear such a future outcome, regardless of whether it becomes a reality or not. Perceptions of insecurity may therefore affect the fertility decisions not only of those most likely to end up in outsider employment, but also those who worry about such an outcome, even if the likelihood might be small.

Building on this, we argue that dualization is likely to negatively affect fertility decisions through its implications for individuals’ perceptions of their current situation and long-term prospects. Further, the insecurity associated with dualization is qualitatively different to periodic episodes of insecurity, which is the focus of much of the literature. In highly dualized labour markets, many workers, particularly women, may see insecurity as a permanent feature of their working life (see also Modena et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, in contexts of intense labour market competition, the associated costs of childrearing (most notably, the costs of education) are likely to be perceived as higher and longer lasting, as parents will want to ensure their child is able to access insider employment. Dualization therefore is likely to intensify the quality-quantity trade-off in parents’ decision-making (Becker & Lewis, Citation1973). Our case study of fertility in Korea provides evidence for each of these effects.

4. Dualization in Korea

While dualization is a feature of the labour markets of most OECD economies, the Korean labour market exhibits a relatively extreme version of this phenomenon, which is widely related to labour market deregulation in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (Fleckenstein & Lee, Citation2017b). Around one third of employees in Korea are found in typically very insecure non-standard employment, with the lion’s share in temporary jobs (21.2 per cent of all employment), considerably higher than the OECD average of 11.7 per cent. Furthermore, the Korean labour market has very high levels of self-employed workers, with a quarter of total employment in this category (25.1 per cent). This is also considerably higher than other countries including Germany (10.2 per cent), often seen as the archetype of dualization processes (OECD, Citation2019b). A large proportion of the self-employed in Korea are essentially precarious workers with income insecurity and in-work poverty similar to the levels of labour market outsiders (Shin, Citation2013).

Non-standard employment is closely related to low wages: the average wage of non-standard employees is only two-thirds of that of standard employees (OECD, Citation2018a). This can be seen at the firm level, with Korea having the largest gap in average labour income between firms at the 90th and 50th percentile (OECD, Citation2016). This high proportion of outsider employment with relatively low wages has led to rapidly increasing income inequality and a polarized labour market in terms of income (OECD, Citation2019b). Aside from remuneration, outsider employment is considerably more insecure than insider employment, with average tenure in 2016 of only 29 months for those in non-standard employment, compared to 89 months among standard workers (OECD, Citation2018b). Furthermore, there is a considerable difference between the opportunities offered to labour market outsiders in terms of access to education and training. Figures from 2016 show that although they made up a third of all employees, non-standard workers were only offered 1.8 per cent of the in-work training opportunities provided by employers (Yun, Citation2016).

Outsider employment is therefore relatively widespread and an objective phenomenon: it is poorly paid, insecure and holds little prospect of career progression. Moreover, it is also a long-term experience. A feature of Korea’s dualized labour market is deep ‘scars’ from outsider employment: non-regular workers are less likely to move to a regular job within 12 months than unemployed people with comparable characteristics (OECD, Citation2015). An examination of Korean perceptions indicates that such scarring is complemented by considerable ‘scaring’; that is, long-term perceptions of insecurity. Concern about insecurity is much more widespread than the third of employees in non-standard employment: when surveyed in 2005, only 40 per cent of Korean workers felt their jobs were secure, compared to 61 per cent in Japan and much higher figures in the United Kingdom and the United States (68 per cent and 74 per cent respectively), two rather flexible labour markets with very little employment protection. Further, this feeling of insecurity is not confined to young people, the figure falls to 37 per cent for those aged 35–54, compared to 58 per cent in Japan, 64 per cent in the United Kingdom and 69 per cent in the United States (ISSP Research Group, Citation2013). In 2005, 62 per cent said they would prefer to work in a large firm rather than a small firm, while 63 per cent said they would prefer to work for the government or civil service than a private employer (Kim et al., Citation2017). A survey in 2012 asked for reasons for this reluctance to work in small firms and found, unsurprisingly, that poor salaries, lower job security and less generous benefit packages were the key responses (Kim et al., Citation2012).

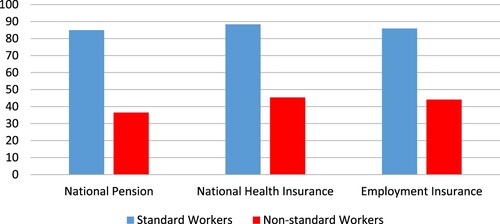

Moreover, despite some improvements in social welfare provision, unemployment protection remains residual in Korea (Fleckenstein & Lee, Citation2017b) – not only is benefit generosity poor by international standards but social insurance coverage is much lower for non-standard workers than for standard employees (see ). This further places a premium on securing insider employment and exacerbates insecurity for outsider workers (Kwon, Citation2018). The country thus lacks the social protection institutions that could mitigate job insecurity and corresponding anxiety (cf. Chung & Mau, Citation2014; Hipp, Citation2016), and this lends credence to the notion that, in Korea, the anxiety provoked by insecurity is not only felt by those at the margins of the labour market but also insiders with poor social protection ‘buffers’ in the country’s increasingly liberal labour market. Indeed, international survey data suggests that Koreans are more anxious about employment insecurity than in comparative countries: in 2005 only 31 per cent of Koreans say that they do not worry at all about the possibility of losing their job, which is 19 percentage points lower than in Japan, a country with very similar labour market institutions (ISSP Research Group, Citation2013). Attitudinal data further demonstrates a perceived absence of support from the welfare state: in a survey in 2015, two thirds of respondents aged 19–34 agreed with the statement that ‘in Korean society if you fail, that is it’ while only a third agreed that ‘even if you fail, there is another chance’ (Hankyoreh Institute, Citation2015). This is not a phenomenon exclusive to younger generations: among all age groups under 50, more people report negative perceptions of social security than positive (Oh et al., Citation2016). Further, in a survey in 2016, the proportion of people who, asked how well the government responded to unemployment, answered ‘badly’ or ‘very badly’ was above 50 per cent in every age group except the over 60s (KIHASA, Citation2016). The lack of social security coverage for large portions of the Korean population is therefore likely to intensify concerns about insecurity and exacerbate fears about outsider employment.

Figure 2 Proportion of workers covered by social insurance schemes, 2017.

Source: Statistics Korea (Citation2017)

Thus, Korea exhibits significant labour market dualization, exacerbated by weak coverage of social protection, which is corroborated by attitudinal data showing that Korean workers perceive the labour market as heavily dualized and perceive a corresponding high degree of insecurity in their own jobs and in Korean society more broadly. Further, these features are felt across the working-age population and are not simply issues for young people or those already in outsider employment. The dualized nature of the Korean labour market therefore displays many of the features likely to impact on fertility decisions beyond the direct effect on individual’s incomes.

5. Dualization and fertility in Korea

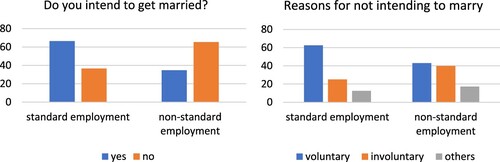

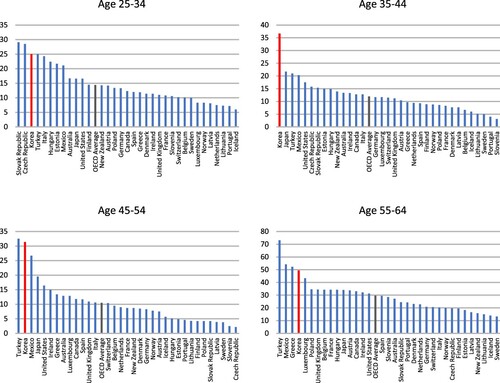

As the literature on insecurity and fertility suggests, the premium on securing insider employment is associated in Korea with young people spending more time on education and skill acquisition and postponing family formation (e.g. Blossfeld et al., Citation2006). This is one of the causes of Korea’s exceptionally high levels of tertiary education, with 70 per cent of 25–34 year olds having tertiary-level education compared to the OECD average of 44 per cent (OECD, Citation2019a). Attitudinal research reveals that concerns about career and labour market outcomes play a significant role in young Koreans’ family planning: among single people aged 20–44, 83.7 per cent of men and 81.3 per cent of women agree or strongly agree that not having sufficient income security to maintain marriage was a reason for ‘people postponing or not getting married at all’, while similar proportions agree or strongly agree that ‘failing to get a job or [finding it] difficult to get a secure job’ was another reason (Kim, Citation2016). Concerns about the labour market are not only related to postponement of family formation however, they are also a factor in what is known as the ‘sampo generation’: the growing number of young Koreans rejecting, not merely postponing, the traditional expectations of courtship, marriage and children (Pang & Yoo, Citation2015). Attitudinal surveys reveal that as many as 31 per cent of women aged 20–39 say that they do not intend to get married, and among the key reasons cited are the financial burdens, insufficient income and employment insecurity (Choi et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, a survey in 2014 among 16–34 year olds in Seoul found that there was a large difference in marriage intention between those in insider and outsider employment, with the latter significantly more likely to have no intention of getting married and cite involuntary reasons for this decision (see ).

Figure 3 Survey on marriage intentions, 16–34 year olds, Seoul, 2014.

Source: Choi et al. (Citation2014)

Why are Koreans not merely postponing family formation but reducing the number of children and in some cases rejecting them completely? As highlighted above, insecurity associated with dualization is distinct from other types of labour market instability because it is often a long-term or permanent feature of many people’s lives. Further, fear of insecurity may affect those who do not directly experience the effects of insecurity themselves. If employment stability, income security and thus the ability to provide well for children are perceived as potentially remote prospects, this can act as a powerful mechanism depressing the long-term commitment to family and children; and the absence of meaningful social protection aggravates the current and perceived future vulnerability from outsiderness in the labour market. However, not only do weak social welfare institutions leave Koreans vulnerable, the country also lacks corporatist institutions with strong trade unions that could provide insiders with a greater sense of security (cf. Chung, Citation2019). Instead, the Korean labour movement has been on a dramatic decline, with its limited influence restricted to large workplaces where fearful insiders are largely preoccupied with defending their ‘privileged’ position, typically at the expense of outsiders. In this context, it is important to underline that the economic turmoil of the 1997 Asian financial crisis and subsequent labour market deregulation not only drove the proliferation of irregular employment, but also left previously well-protected insiders more vulnerable to the market. Corresponding with the insecurity literature, economic crisis has left a lasting scar in the collective memory of Korean workers, including those who should feel most confident about their future. Peak labour organizations, despite some progress, have struggled to overcome the insider orientation of enterprise unions, which is increasingly considered an unviable strategy in an environment of labour weakness (Fleckenstein & Lee, Citation2019; Yang, Citation2006). Perceptions of insecurity are thus not limited to outsiders. Critically, these effects of dualization on family formation are amplified by two related developments: first, because dualization is gendered, it increases the conflict between family and career for women to an extreme level; and second, it exacerbates the quantity-quality trade-off by raising the costs associated with children due to the premium attached to education. Both of these raise the costs (indirect and direct) of having children to a level that is perceived as unaffordable for many families.

5.1. Dualization and work-family conflict

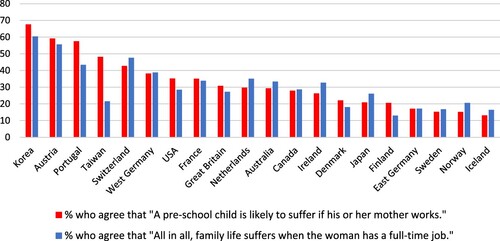

The literature on fertility stresses that in contexts in which combining work and family roles is difficult, children involve very high opportunity costs for many women who are forced to sacrifice their careers to have a family (e.g. Becker, Citation1981; McDonald, Citation2000a). The dualized Korean labour market represents such a context, where insider jobs are built on a male-breadwinner model and require long hours: full-time Korean employees work among the longest hours in the OECD, with an average of 45.7 hours per week (OECD, Citation2019b). Along with long hours, gender roles in Korean families are relatively conservative, with women undertaking the vast majority of unpaid domestic work within families: comparative data reveals that among OECD countries, men spend considerably less time on unpaid work in Korea than in any other country apart from Japan (OECD, Citation2021). These factors mean that should women stay in the labour market after childbirth, they are likely to face an extreme double burden of long hours of paid employment as well as unpaid domestic work. Indeed, social norms reflect the fact that, for most families, combining work and family is very difficult: two-thirds of Korean respondents agreed in 2012 that ‘a pre-school child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works’, a greater proportion than in any other country surveyed by the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP). Furthermore, a higher proportion of Koreans than in other countries also agreed that ‘family life suffers when the woman works full-time’ (see ). And while survey evidence from 2006 shows that nearly three-quarters (73 per cent) of Koreans agree that ‘men ought to do a larger share of household work than they do now’, other evidence points to a greater demand for part-time work (see Kim et al., Citation2017). This incompatibility between standard employment and family responsibilities puts huge downward pressures on fertility.

Figure 4 Responses to ISSP questions on maternal employment, 2012.

Source: ISSP Research Group (Citation2016)

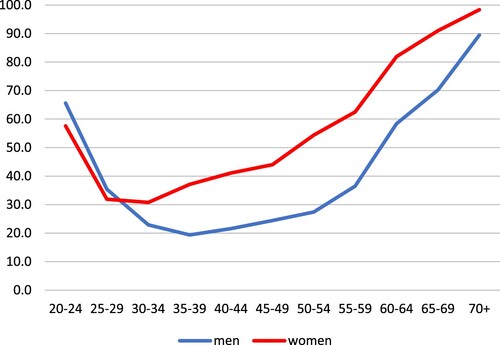

Attempts to ease this conflict have resulted in expansion of parental leave policies, with financial incentives for fathers to take leave and to encourage combinations of leave and part-time employment (Kim, Citation2020). However, this provision has encountered friction with Korea’s traditional employment practices and non-compliance is relatively common: 28 per cent of Korean employers admit that they have illegally restricted their employees’ access to parental leave, with the most common restriction being that they ‘forced their employees not to take leave’ (Song, Citation2019). Beside employer intransigence, cultural norms also mitigate against full use of parental leave and it is no surprise that take up rates are very low: while 303,100 babies were born in Korea in 2019 only 73,306 employees took maternity leave (approximately 24 per cent) and 105,165 employees took parental leave (approximately 17 per cent) (Kim, Citation2020). Low take up of leave indicates that many women withdraw from the labour market at childbirth, and those that do, do so for an average of 10 years (Hong & Lee, Citation2014). This can be seen in the gender employment gap, which is non-existent among people aged 20–29, but widens significantly among people aged 30–34, to a greater extent than in other OECD countries, and then remains comparatively large over later age groups (see ).

Figure 5 Gender employment gaps, by age, selected countries.

Source: OECD (Citation2021)

In this context, it is also important to point out the relatively low though increasing incidence of part-time work in Korea (15.4 per cent in 2020, up from 7 per cent in 2000; compared to 22.5 per cent in Germany, 25.8 per cent in Japan, and 36.9 per cent in the Netherlands [OECD, Citation2023]), which can be seen as presenting an additional challenge in work-family reconciliation and thus facilitating labour market withdrawal among young women. In a heavily dualized labour market, withdrawing from employment represents a very significant sacrifice for women in insider employment, as they are unlikely to regain insider status upon their return. Indeed, dualization in the Korean labour market has a very gendered character: women make up 55 per cent of those in non-regular employment, and only 39 per cent of those in regular employment (OECD, Citation2018b), a gap that only appears in the over-thirties and remains quite high at around 20 per cent throughout all subsequent age groups (see ).

Figure 6 Proportion of employees in non-regular employment, by age and gender, 2018.

Source: Kim (Citation2018)

This gendered dualized labour market is a key reason for Korea’s very large gender wage gap, which at 34 per cent is the highest in the OECD, much higher than the average of 13 per cent. Once again, this very high rate only develops when people enter their thirties: for those aged 25–29 the gender wage gap is near the OECD average of 10 per cent, yet for people aged 40–44 it stands at 42 per cent, whereas the OECD average is 24 per cent (OECD, Citation2018a). Key reasons for this are the concentration of women in low-paid, low-productivity employment and that relatively few women are in well-paid, managerial positions, either in the private sector or in the civil service. In total, nearly a third (30 per cent) of female employees are in low-paid employment in Korea, considerably higher than the OECD average of 19 per cent (OECD, Citation2019b). For highly educated women returning to outsider employment there is a significant reduction in status, and many choose to remain economically inactive after childbirth: as demonstrates, Korea has high levels of economic inactivity among women with tertiary education among all age groups, but the gap between Korea and other OECD countries is especially stark for women aged 35–44. These high levels of economic inactivity reduce the family income that is available for costly private tuition, which is increasingly regarded as a necessity for securing an insider job, and thus force many families to choose ‘quality’ over ‘quantity’, as we will show in the next section.

Figure 7 Economic inactivity rates among women with tertiary education, by age groups, OECD countries, 2018.

Source: OECD (Citation2019a)

This situation indicates that women face very high opportunity costs from having children, something recognized in international attitudinal surveys, with Korean women among the most likely to agree with the statement that children ‘restrict the career chances of one or both parents’ (ISSP Research Group, Citation2016). While long working hours, inflexible working practices, traditional attitudes and employer non-compliance with work-family reconciliation measures all contribute to Korean women tending to leave paid employment at childbirth, it is the dualized labour market that turns what may be seen as a ‘career pause’ in some countries into a permanent sacrifice in Korea. This is a clear example of the way in which dualized labour markets lead to a permanent form of insecurity that affects insiders as well as outsiders. Given the stark choices facing women in this situation, it should be no surprise that an increasing number of young women are choosing not just to postpone, but to forego having children altogether.

5.2. Dualization and the direct costs of children

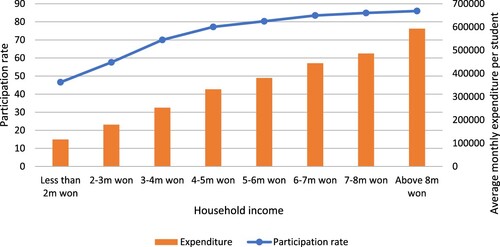

It is well established that Korean society holds education in high esteem, with Confucianism widely seen as providing the cultural foundation for Koreans’ educational drive (Seth, Citation2002). As discussed earlier, enrolment rates in universities are now uniquely high: nowhere else in the OECD do more young people enter tertiary education. Aside from these very high levels of tertiary education, the most striking aspect of Korean education is the extraordinary growth and usage of private tutoring alongside public education: it is estimated that 76 per cent of Korean school students receive private tutoring, with the figure for elementary school students even higher at 82 per cent, with each student spending an average of 6.7 hours per week in private tuition; and the average monthly expenditure per participating student is roughly 11 per cent of average household income (Statistics Korea, Citation2022). Unsurprisingly, both participation rates and the level of expenditure are correlated with household income, with those with an income of more than 8 million won (about $6,300) per month spending roughly five times as much per student as those earning less than 2 million won ($1,575), while the respective participation rates are 86 per cent and 47 per cent (see ). Fierce competition in education fuelled by the dualized labour market, we argue, has led most Korean parents to spend a significant portion of their household income on private education, a burden that is intensified if there is only one parent in work.

Figure 8 Participation rates and average monthly expenditure on private tuition by household income, 2021.

Source: Statistics Korea (Citation2022)

Links between Korean ‘education fever’ and low fertility is a feature of the demography literature. Anderson and Kohler (Citation2013) find that Korean provinces with higher birth rates spend less per household on education than those with lower birth rates, suggesting that the cost of education in the latter regions supresses birth rates; they show the same regional effect in terms of the concentration of large and small families. Kim (Citation2017) finds that private expenditure on childcare and private education is negatively correlated with the intention to have a second child.

However, the foundation of Korea’s ‘education fever’ in the dualized labour market is rarely adequately articulated in the context of fertility decisions. The argument here is that the same dualization which drives childbirth postponement in women’s twenties and leads some to opt out of marriage and childbirth altogether is also driving families to opt for fewer children due to the costs of private education and the intense competition for insider jobs. Instead of seeing ‘education fever’ as a cultural quirk emerging from Koreans’ adherence to Confucian values, the argument here is that dualization has led to a self-reinforcing institutional equilibrium in which Korea’s ‘winner-takes-all’ labour market places an immense amount of pressure on families to achieve the best possible education.

However, while it is clear that a university degree is seen as a prerequisite for a good career in Korea, even about one third of those in non-standard employment have completed tertiary education (OECD, Citation2018b). Adding to educational pressure, in Korea’s hierarchical university system the value of degrees varies considerably among different universities. Evidence shows that labour market success is strongly related to the attendance of ‘elite’ universities, that graduates of universities in Seoul have better labour market outcomes and that, aside from a few specific subjects, the choice of university is more important for income than the choice of subject (Kim & Lee, Citation2006; Park, Citation2015). The huge expansion in tertiary education in Korea in the 1990s largely took place in private institutions and outside Seoul, meaning today a much lower proportion of university entrants go, for instance, to one of the three Seoul ‘elite’ institutions, Seoul National University, Korea University or Yonsei University; in 1981, 14 per cent of high school graduates entered these three universities, by 2007 this figure was only 3 per cent (Kim, Citation2010). Competition for ‘elite’ universities is severe and has a deep impact on the rest of the Korean education system, most notably in the level of expenditure and attendance of private tuition.

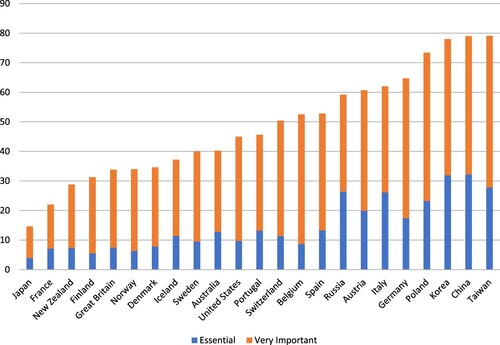

Our argument above is that the effects of dualization are particularly strong because they are perceived as permanent, and because they are not restricted to labour market outsiders but affect a growing and substantial number of insiders too. This applies just as much in the case of ‘education fever’: indeed, we argue that it is through Koreans’ perceptions of the importance of education and ensuring that their children have access to insider employment that the use of costly private education has crystallized into a social norm, with parents reporting the perception that their child will be disadvantaged if they do not use private tuition (Fleckenstein & Lee, Citation2019). This is fuelled by a common belief among Koreans that the level of prestige of the university one attends translates directly into one’s future career success and these views are structured and reinforced through university ranking systems. A survey in 2011 asking respondents for reasons for the growth in private tutoring spending found that the most common response was ‘the name of the university one graduates from is important for future job prospects’, while the second and third most common both referred to competition for university places (Jones, Citation2013). In a survey in 2014, three quarters of respondents (76 per cent) believe that educational attainment determines one’s life (Hankook Daily, Citation2014). But winning a place at an elite institution provides students with more than just education: as with other hierarchical university systems, alumni networks are important for graduates; and this is reflected in public attitudes. For example, 32 per cent of Koreans say that ‘knowing the right people’ is essential in getting ahead in life, while 78 per cent say it is either essential or very important, which, as shows, are comparatively very high proportions (ISSP Research Group, Citation2017). From a fertility point of view, this spending on education represents a very heavy financial cost for potential parents to consider, which can be seen in that Korea is one of only a few countries in which more than 50 per cent of respondents to an ISSP survey in 2012 agreed that ‘children are a financial burden on their parents’ (ISSP Research Group, Citation2016). Furthermore, a survey in 2015 that directly asked Koreans about why they did not plan to have more children found the most common response was ‘education costs’ (Lee et al., Citation2015). Thus, dualization and the associated insecurity has deep-rooted implications for the perceived costs of raising children, an effect that reaches across Korean society.

Figure 9 Importance of ‘knowing the right people’ in getting ahead in life, 2009.

Source: ISSP Research Group (Citation2017)

6. Conclusions

We have shown that the relatively extreme, though not unique, labour market dualization in Korea plays a very significant role in the country’s persistently low birth rate. It is argued that it has three main effects. First, not only has dualization encouraged the trend of young people postponing family formation and therefore the sharp and sustained fall in fertility rates among women in their twenties, it has also depressed family size and even led to young couples foregoing parenthood altogether because of the permanent insecurity that is associated with the prospect of outsiderness. In highly dualized labour markets, young people cannot be confident that insecurity is confined to the education-employment transition, but it might become a feature of their entire working life. Further, fear of insecurity affects more than just those most likely to become labour market outsiders; in a context in which outsider employment has severe consequences, fear of insecurity is evident among insiders as well. Thus, the particular nature of dualization associated with insecurity affects fertility decisions across a broad swathe of the population. Second, dualization is gendered; it therefore intensifies the incompatibility between work and family for women, especially those in insider employment, and significantly raises the stakes of a temporary withdrawal from the labour market. Dualization contributes to children representing very high opportunity costs for women in terms of their careers and future earning ability and therefore influences the growing trend in childlessness. Third, the intense competition for insider employment inherent to the dualized labour market has led to the entrenchment of ‘education fever’ as a social norm in which parents spend significant sums on their children’s education. Private tutoring in particular is widely perceived as a huge burden on family finances; and feelings of permanent insecurity are likely to impact on families’ confidence that they can afford to invest significant and sustained amounts in their children’s education – especially when women’s withdrawal from the labour market consigns families to reliance on a single, potentially insecure income in the absence of meaningful social protection mechanisms, while women’s subsequent return to employment will typically be in outsider employment.

These findings pose a significant challenge not only to demographic theories that consider insecurity as a temporary problem confined to the education-employment transition but also to gender equity theories of fertility. In particular, they question the assertion that gender equity has been achieved in employment institutions and the lack of attention to labour market conditions. The dualization of labour markets across the OECD is a gendered process; women tend to be over-represented among labour market outsiders, meaning many women’s experiences of employment is insecure, poorly remunerated and associated with a host of negative outcomes from limited career progression to exclusion from social security programmes. Feminist scholars have long pointed out the problems with assuming that an ‘adult worker model’ is inherently one that is positive for women (e.g. Lewis, Citation2001). Indeed, the Korean case demonstrates that a heavily dualized labour market poses a number of difficult dilemmas for women, which do little to enhance gender equality or align with the aspirations of career-oriented women. The findings show that in general young people face uncertain futures, with the possibility of a lifetime of outsider employment a credible threat and one that faces women in particular, making the choice to have children one that is fraught with risk, especially for women. However, while challenging some of the foundational assumptions, our findings also demonstrate that the logic of gender equity theories add to the low fertility picture in Korea, although they are exacerbated by labour market conditions. In the context of a dualized labour market, young women that do manage to secure insider employment face very high opportunity costs from the prospect of children. While the traditional nature of Korean gender roles certainly adds to these costs, the overriding contributor is the fact that insider employment is largely structured around male-breadwinner working patterns – it is overwhelmingly full-time, inflexible and with very long hours – while giving up insider employment will often consign one to a lifetime of outsider employment due to scarring effects. In this context, it is not simply the mismatch between gender equity in public and private institutions that causes low fertility, but it is the continuing disadvantages women face in both realms that contribute. The fact that Korea’s path-shifting work-family policies have had no discernible effect on the country’s fertility rate would appear to support these conclusions.

The policy implications of our argument are significant: addressing insecurity appears critical to reversing the downward pressure it places on fertility. To date, neither of the two most frequently proposed solutions address this issue: social investment or liberal labour market reforms. The former prioritizes investments in human capital and promotes women’s employment – which are certainly important for ‘future-proofing’ Korea – but such a strategy is ‘thin’ with regard to perceived insecurity in the face of dualization and the absence of strong social protection mechanisms. Having said this, from the outset of social investment advocacy, Esping-Andersen (Citation2002, p. 5) has argued that the ‘minimization of poverty and income insecurity is a precondition for an effective social investment strategy’. In any case, our research suggests that the preoccupation with work-family policies in Korea at the expense of social protection requires reconsideration. Bonoli et al. (Citation2017) underline that a more equal distribution of incomes is imperative if social investment strategies are to deliver their promise of greater equality of opportunity and social mobility; and our research argues this is true also for the reversal of fertility decline. Alternatively, the OECD has frequently suggested that Korea addresses dualization by reducing the employment protection regulations that govern insider jobs (see e.g. OECD, Citation2018a). While this could help to ‘level the playing field’ in the Korean labour market, it is likely to increase rather than reduce insecurity and would therefore intensify many of the impacts that this paper has discussed. Policy ideas are needed which address how young people, and young women in particular, experience a range of institutions including formal and informal education, the transition from education to employment and, fundamentally, the labour market itself. While Korea presents an extreme case, the trends highlighted in the Korean labour market associated with dualization are present across the OECD. As such, Korea can act as a warning for other OECD countries which are seeing some of these features develop in their own societies. Continued dualization might eventually reverse the recent fertility ‘recovery’ in a number of European countries, if increased perceived insecurity because of growing insider/outsider polarization suppresses the quantum fertility of women in their thirties – the source of recent fertility increases in low-fertility countries. Policymakers might be thus well advised to consider growing labour market dualization more carefully.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timo Fleckenstein

Timo Fleckenstein is an Associate Professor in the Department of Social Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His research focuses on labour market, family and education policies with a particular interest in the comparison of Europe and East Asia.

Soohyun Christine Lee

Soohyun Christine Lee is a Korea Foundation Senior Lecturer in Korean and East Asian Political Economy in the Department of European and International Studies at King’s College London. Her research interests lie in the comparative political economy of welfare states, with a regional focus on East Asia.

Samuel Mohun Himmelweit

Samuel Mohun Himmelweit is an LSE Fellow in the Department of Social Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His research interests involve the comparative analysis of welfare state continuity and change in the face of challenges presented by socio-economic and demographic trends.

References

- Adserà, A. (2004). Changing fertility rates in developed countries: The impact of labor market institutions. Journal of Population Economics, 17(1), 17–43.

- Adserà, A. (2005). Vanishing children: From high unemployment to low fertility in developed countries. American Economic Review, 95(2), 189–193.

- Anderson, T. & Kohler, H.-P. (2013). Education fever and the East Asian fertility puzzle. Asian Population Studies, 9(2), 196–215.

- Anderson, T. & Kohler, H.-P. (2015). Low fertility, socioeconomic development, and gender equity. Population and Development Review, 41(3), 381–407.

- Balbo, N., Billari, F. C. & Mills, M. (2013). Fertility in advanced societies: A review of research. European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie, 29(1), 1–38.

- Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press.

- Becker, G. S. & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2), S279–S288.

- Bertola, G., Blau, F. D. & Kahn, L. (2002). Labour market institutions and demographic employment patterns (Discussion Paper). London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Blossfeld, H.-P., Klijzing, E., Mills, M. & Kurz, K. (2006). Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society: The losers in a globalizing world. Routledge.

- Bonanomi, A. & Rosina, A. (2022). Employment status and well-being: A longitudinal study on young Italian people. Social Indicators Research, 161(2-3), 581–598.

- Bonoli, G., Cantillon, B. & Van Lancker, W. (2017). Social investment and the Matthew effect: Limits to a strategy. In A. Hemerijck (Ed.), The uses of social investment (pp. 66–76). Oxford University Press.

- Bray, M. (2021). Shadow education in Europe: Growing prevalence, underlying forces, and policy implications. ECNU Review of Education, 4(3), 442–475.

- Brinton, M. C. & Lee, D.-J. (2016). Gender-role ideology, labor market institutions, and post-industrial fertility. Population and Development Review, 42(3), 405–433.

- Castles, F. G. (2003). The world turned upside down: Below replacement fertility, changing preferences and family-friendly public policy in 21 OECD countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 13(3), 209–227.

- Choe, M. K. & Retherford, R. D. (2009). The contribution of education to South Korea’s fertility decline to ‘lowest-low’ level. Asian Population Studies, 5(3), 267–288.

- Choi, E.-Y., Park, S.-Y., Jin, N.-Y., Kang, S.-J., Lee, B.-J., Kim, K.-T., … Kim, S.-H. (2014). Policy proposal to address housing poverty among the youth living in Seoul. Seoul Metropolitan Council.

- Choi, H.-M., Yoo, H.-M., Kim, J.-H. & Kim, T.-W. (2016). Perception of non-marriage among young people and policy measures to address low-fertility. Korea Institute of Child Care and Education.

- Chung, H. (2019). Dualization and subjective employment insecurity: Explaining the subjective employment insecurity divide between permanent and temporary workers across 23 European countries. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 40(3), 700–729.

- Chung, H. & Mau, S. (2014). Subjective insecurity and the role of institutions. Journal of European Social Policy, 24(4), 303–318.

- Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y. & Sanfey, P. (2001). Scarring: The psychological impact of past unemployment. Economica, 68(270), 221–241.

- Eberstadt, N. (1994). Demographic shocks after communism: Eastern Germany, 1989–93. Population and Development Review, 20(1), 137–152.

- Emmenegger, P., Häusermann, S., Palier, B. & Seeleib-Kaiser, M. (2012). The age of dualization. Oxford University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2002). Towards the good society, once again? In G. Esping-Andersen, D. Gallie, A. Hemerijck & J. Myles (Eds.), Why we need a new welfare state (pp. 1–25). Oxford University Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. & Billari, F. C. (2015). Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 1–31.

- Fleckenstein, T. & Lee, S. C. (2017a). The politics of investing in families: Comparing family policy expansion in Japan and South Korea. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 24(1), 1–28.

- Fleckenstein, T. & Lee, S. C. (2017b). The politics of labor market reform in coordinated welfare capitalism. World Politics, 69(1), 144–183.

- Fleckenstein, T. & Lee, S. C. (2019). The political economy of education and skills in South Korea: Democratisation, liberalisation and education reform in comparative perspective. The Pacific Review, 32(2), 168–187.

- Gauthier, A. H. (2007). The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: A review of the literature. Population Research and Policy Review, 26(3), 323–346.

- Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E. & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207–239.

- Goldstein, J. R., Sobotka, T. & Jasilioniene, A. (2009). The end of ‘lowest-low’ fertility? Population and Development Review, 35(4), 663–699.

- Hankook Daily. (2014). 76% of public believes ‘education attainment determines one’s life’.

- Hankyoreh Institute. (2015). Young people’s perception survey. Hankyoreh Institute.

- Helbling, L. A. & Sacchi, S. (2014). Scarring effects of early unemployment among young workers with vocational credentials in Switzerland. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 6(1), 12.

- Hipp, L. (2016). Insecure times? Workers’ perceived job and labor market security in 23 OECD countries. Social Science Research, 60(1), 1–14.

- Hong, S.-A. & Lee, I. (2014). Fathers’ use of parental leave in Korea: Motives, experiences and problems. Korean Women’s Development Institute.

- ISSP Research Group. (2013). International social survey programme: Work orientation III – ISSP 2005. GESIS Data Archive.

- ISSP Research Group. (2016). International social survey programme: Family and changing gender roles IV – ISSP 2012. GESIS Data Archive.

- ISSP Research Group. (2017). International social survey programme: Social inequality IV – ISSP 2009. GESIS Data Archive.

- Jones, R. S. (2013). Education reform in Korea (OECD Economics Department Working Papers). OECD Economics Department.

- KIHASA. (2016). Korea welfare panel study. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; Institute of Social Welfare, Seoul National University.

- Kim, E. H.-W. (2017). Division of domestic labour and lowest-low fertility in South Korea. Demographic Research, 37(24), 743–768.

- Kim, E.-S., Kim, K.-S. & Yoon, E.-S. (2012). The actual condition survey of job mismatch in Gyeonggi-Do. Policy Studies, Gyeonggi: Gyeonggi Research Institute.

- Kim, H. (2020). Korea country note. In A. Koslowski, S. Blum, I. Dobrotić, G. Kaufman & P. Moss (Eds.), International review of leave policies and research 2020 (pp. 365–372). FernUniversität in Hagen.

- Kim, I.-H., Muntaner, C., Khang, Y.-H., Paek, D. & Cho, S.-I. (2006). The relationship between nonstandard working and mental health in a representative sample of the South Korean population. Social Science & Medicine, 63(3), 566–574.

- Kim, J., Kang, J., Kim, S.-h., Kim, C., Park, W., Lee, Y.-S., … Kim, S. (2017). Korean general social survey 2003–2016. Sungkyunkwan University.

- Kim, S. (2010). Globalisation and individuals: The political economy of South Korea’s educational expansion. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 40(2), 309–328.

- Kim, S. & Lee, J.-H. (2006). Changing facets of Korean higher education: Market competition and the role of the state. Higher Education, 52(3), 557–587.

- Kim, S. G. (2016). The 2012 national survey on fertility, family health and welfare in Korea. KIHASA.

- Kim, Y. & Kim, S.-S. (2018). Job insecurity and depression among automobile sales workers: A longitudinal study in South Korea. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 61(2), 140–147.

- Kim, Y.-S. (2018). The scale and situation of non-standard employment (KLSI Issue Paper). Korea Labour & Society Institute.

- Klug, K., Bernhard-Oettel, C., Mäkikangas, A., Kinnunen, U. & Sverke, M. (2019). Development of perceived job insecurity among young workers: A latent class growth analysis. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 92(6), 901–918.

- Knabe, A. & Rätzel, S. (2011). Scarring or scaring? The psychological impact of past unemployment and future unemployment risk. Economica, 78(310), 283–293.

- Kreyenfeld, M. (2010). Uncertainties in female employment careers and the postponement of parenthood in Germany. European Sociological Review, 26(3), 351–366.

- Kreyenfeld, M., Andersson, G. & Pailhé, A. (2012). Economic uncertainty and family dynamics in Europe. Demographic Research, 27(28), 835–852.

- Kwon, J. (2018). Effects of health shocks on employment and income. Korean Journal of Labour Economics, 41(1), 31–62.

- Lee, S. C. (2018). Democratization, political parties and Korean welfare politics: Korean family policy reforms in comparative perspective. Government and Opposition, 53(3), 518–541.

- Lee, S.-S., Park, J.-S., Lee, S.-Y., Oh, M.-A., Choi, H.-J. & Song, M.-Y. (2015). The 2015 national survey on fertility and family health and welfare. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA).

- Lewis, J. (2001). The decline of the male breadwinner model: Implications for work and care. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 8(2), 152–169.

- Lübke, C. (2021). How self-perceived job insecurity affects health: Evidence from an age-differentiated mediation analysis. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 42(4), 1105–1122.

- Mauno, S. & Kinnunen, U. (2002). Perceived job insecurity among dual-earner couples: Do its antecedents vary according to gender, economic sector and the measure used? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75(4), 295–314.

- McDonald, P. (2000a). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26(3), 427–439.

- McDonald, P. (2000b). Gender equity, social institutions and the future of fertility. Journal of the Australian Population Association, 17(1), 1–16.

- McDonald, P. (2006). Low fertility and the state: The efficacy of policy. Population and Development Review, 32(3), 485–510.

- Modena, F., Rondinelli, C. & Sabatini, F. (2014). Economic insecurity and fertility intentions: The case of Italy. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(S1), S233–S255.

- Myrskylä, M., Kohler, H.-P. & Billari, F. C. (2009). Advances in development reverse fertility declines. Nature, 460(7256), 741–743.

- OECD. (2015). In it together: Why less inequality benefits all. OECD.

- OECD. (2016). Promoting productivity and equality: Twin challenges. OECD Economic Outlook. OECD.

- OECD. (2017a). Starting strong 2017: Key OECD indicators on early childhood education and care. OECD.

- OECD. (2017b). Pursuit of gender equality: An uphill battle. OECD.

- OECD. (2018a). OECD economic surveys: Korea 2018. OECD.

- OECD. (2018b). Towards better social and employment security in Korea. OECD.

- OECD. (2019a). Education at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD.

- OECD. (2019b). Employment database. OECD.

- OECD. (2020). Fertlity rates (indicator). OECD.

- OECD. (2021). Family database. OECD.

- OECD. (2023). Part-time employment rate (indicator). OECD.

- Oh, Y.-S., Kim, M.-K., Lim, W.-S., Kang, J.-W., Lee, K.-H. & Lee, S. (2016). Survey on public perception of social security achievement. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA).

- Olivetti, C. & Petrongolo, B. (2017). The economic consequences of family policies: Lessons from a century of legislation in high-income countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), 205–230.

- Origo, F. & Pagani, L. (2009). Flexicurity and job satisfaction in Europe: The importance of perceived and actual job stability for well-being at work. Labour Economics, 16(5), 547–555.

- Pang, H. & Yoo, S. (2015). Korean newspapers and discourses on the young generation: From silk generation to sampo generation. Korean Journal of Journalism & Communication Studies, 59(1), 37–61.

- Park, H. (2015). A study on the horizontal stratification of higher education in South Korea. Asia Pacific Education Review, 16(1), 63–78.

- Ralston, K., Everington, D., Feng, Z. & Dibben, C. (2022). Economic inactivity, not in employment, education or training (NEET) and scarring: The importance of NEET as a marker of long-term disadvantage. Work, Employment and Society, 36(1), 59–79.

- Rueda, D. (2014). Dualization, crisis and the welfare state. Socio-Economic Review, 12(2), 381–407.

- Seth, M. J. (2002). Education fever: Society, politics, and the pursuit of schooling in South Korea. University of Hawaii Press.

- Shin, K.-Y. (2013). Economic crisis, neoliberal reforms, and the rise of precarious work in South Korea. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(3), 335–353.

- Song, K.-S. (2019, May 8). Childcare leave taken by fewer than may want it. Korea JoongAng Daily.

- Statistics Korea. (2017). Press brief: Results of supplementary survey by employment type (August 2017). Economically Active Population Survey. Statistics Korea.

- Statistics Korea. (2021). Birth statistics. Statistics Korea.

- Statistics Korea. (2022). Private education expenditures survey of elementary, middle and high school students in 2021. Statistics Korea.

- Yang, J.-J. (2006). Corporate unionism and labor market flexibility in South Korea. Journal of East Asian Studies, 6(2), 205–231.

- Yoo, S. H. & Sobotka, T. (2018). Ultra-low fertility in South Korea: The role of the tempo effect. Demographic Research, 38(22), 549–576.

- Yun, H. (2016). Implications of the performance evaluation of the job creation project. KDI Focus. Korea Development Institute.