Abstract

The asset management industry is becoming a systemic feature of global finance, yet has evaded regulators’ efforts to designate its largest firms as systemically important institutions. How has this been achieved? We use as our example BlackRock’s running commentary on the evolving plans of both prudential (banking) and securities (market) regulators in the period from 2008 to 2018. We show how asset managers engaged in successful recognitional politics, based on a decade-long struggle to influence how they were seen across the regulatory divide. James C. Scott’s most recent thoughts on legibility codes provide us with our conceptual language of shape-shifters and chameleons. Two distinct strategies were simultaneously in play. As a shape-shifter, BlackRock repeatedly changed form in its self-presentation to prudential regulators concerned with systemic risk, so they could not be certain what they were looking at. As a chameleon, it invited securities regulators to maintain their authority over the asset management industry, so it could increasingly blend into the supposedly safe category of market-based finance.

Introduction

The numbers appear to confirm the prediction of the former chief economist of the Bank of England, Andy Haldane (Citation2014), that this would be the ‘age of asset management’. Between 2010 and 2021, the industry increased its assets under management from US$46.6 trillion to $108.6 trillion, equivalent to one-fifth of the world’s entire asset base (BCG, Citation2023). The largest firm, BlackRock, was alone responsible for $10 trillion (FSB, Citation2021). This rapid growth occurred without a parallel increase in regulatory scrutiny, as asset managers continued to be watched closely by securities regulators but had avoided similar oversight by prudential regulators. Volatility during the COVID-19 pandemic called this favourable position into question. In some instances, central banks had to introduce ostensible backstops to asset classes and market segments previously considered outside their reach, invariably propping up the investment positions of asset managers (IMF, Citation2020). A key question thus emerges: given the increasingly systemic role of asset managers, how have they escaped the types of regulations placed on similarly systemically important counterparts in the aftermath of the global financial crisis?

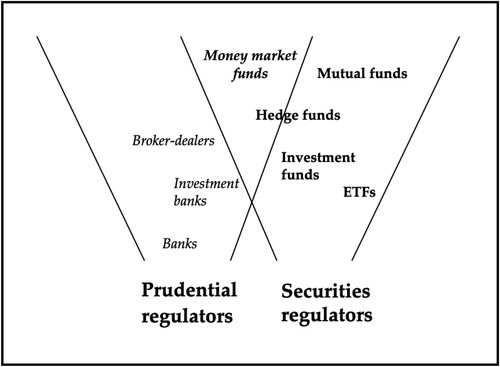

The existing political economy literature on asset managers fails to provide a definitive answer. It has extensively studied their market power (their role in influencing the corporate governance of the firms they invest in (Baines & Hager, Citation2023; Braun, Citation2022; Fichtner & Heemskerk, Citation2020)) and their structural power (acting as mediators of creditworthiness and solvency in emerging-market sovereign bond markets (Bonizzi & Kaltenbrunner, Citation2024)). However, their instrumental power, such as the capacity to lobby successfully for a favourable political landscape, has received rather scant attention (but see James & Quaglia, Citation2023). In part, this is because studies of post-crisis reform have tended to focus on the key industries under regulatory scrutiny, such as banks and shadow banks (e.g., Baker, Citation2013; Pagliari & Young, Citation2016), or on the regulators themselves (Thiemann, Citation2024). This literature has yielded important insights, most notably the idea that financial actors strategically exploit inter-institutional and jurisdictional tensions between typically light-touch securities market regulators and more prudentially-minded banking regulators (Quaglia, Citation2022). By aligning themselves with securities regulators, financial actors can resist the expansive gaze of banking regulators concerned with systemic risks. Yet, the precise form of political agency pursued by asset managers in this process is underexplored – a crucial gap, given that the industry appeared to be achieving the best-of-all-worlds scenario by remaining answerable to the less onerous demands of securities regulators despite the increasing scale and interconnectedness of the markets in which it operated.

The instrumental power and regulatory capture literatures offer a useful starting point for analysing how this situation arose. The favourable position from which asset managers conduct their day-to-day business looks similar in many respects to what these literatures tell us we should encounter had BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street et al. used their formidable resources to lobby directly for self-interested outcomes. But subtler metaphors of sight are more apt in this instance than focusing on exercises of raw instrumental power or capture. Asset managers enacted strategies to influence how they were seen by regulatory authorities, on the assumption that if they were to be recognized as a particular type of entity then they could, in effect, choose which regulatory framework they would be incorporated into. This is different from refusing to be bound by policies they find disagreeable and seeking to impose their own understanding of where the outer limits of feasible policy lie (see Carpenter & Moss, Citation2013, for an overview). Many possible variants have been suggested on the capture theme: the broader sociological circles in which policymakers move; the cultural signifiers that are most important to those environs; the basic cognition that helps to distinguish good policies from bad; and the policymaking network itself (e.g., Kwak, Citation2014). Yet in our case it does not seem as though anything has been captured in the classical sense of an agency succumbing directly to the influence of those it is formally required to regulate.

We prefer to focus our explanatory content on what we term recognitional politics, a strategy not so much to capture prudential authorities as to make it harder for them to know what they are looking at. This is recognition, then, in the everyday sense of ‘being seen as’. We analyse BlackRock specifically, not because it stood alone in challenging the favoured optics of prudential regulators, but because it has donned the mantle of self-appointed spokesperson for the asset management industry within what, in reality, is a dense network of competing attempts by industry insiders to add their voice to debates. BlackRock does stand out, though, for how much money it allocated to financing a more detailed running commentary than the regulators themselves managed on the implications of proposed changes to regulatory principles. It was noticeable that we had over 100 publications and 17 responses to sector-wide consultation documents from which to reconstruct the pattern of BlackRock’s statements, compared with just over 40 policy papers published in aggregate by the Federal Reserve, Financial Stability Board (FSB), Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) and the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). However, BlackRock’s decision to throw a lot of its own funds at occupying regulators’ time was not an attempt to effect what Wendy Wagner (Citation2010, p. 1328) calls ‘information capture’. It was designed instead to obstruct prudential regulators from gaining a clear line of sight of asset managers as bank-like entities so they could remain under the remit of securities regulators. BlackRock enacted recognitional politics specifically to avoid being caught in prudential regulators’ ever-expanding gaze, not to reject all possible regulation of its activities or even to imprint its interests explicitly on the fine print of new regulatory policy.

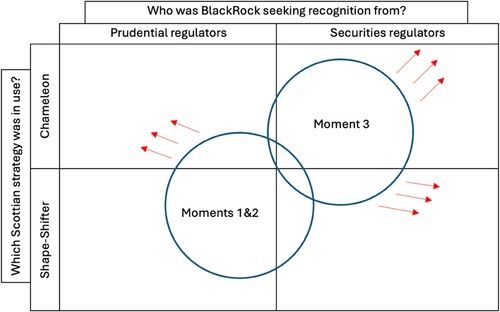

We employ James C. Scott’s idea of legibility codes (Citation1998, pp. 30–37) to develop our theoretical argument. This concept has been used to show how state officials mould a particular image of the agents they wish to regulate as a way of rendering otherwise hard-to-define entities and activities accessible to political management. There is an important difference, though, between the feel of his earlier and later work. In 1998’s Seeing Like a State, regulation comes across as a simpler process in which regulators enact a one-time freeze of their preferred image of those they wish to regulate. In 2009’s The Art of Not Being Governed, the regulated are provided with considerably more agency to unsettle regulators’ plans, changing form or disappearing from view altogether to deny regulators a firm fix on what they think they are seeing. BlackRock did exactly that when providing prudential regulators with a moving target which refused to align with their expanding field of vision in the 2010s (see ). Asset managers appeared content to allow themselves to be seen by securities regulators so that they might continue to be subjected to their lighter-touch demands, but this first meant that they had to disrupt the sight of prudential regulators. As the Fed, FSB and FSOC were intent on viewing more and more financial firms in bank-like form, this required significant discursive hopping between different frames. BlackRock developed counter-legibility codes to open spaces of ambiguity between what prudential regulators believed they were seeing and how asset managers consented to be seen.

Our paper makes two distinctive contributions: firstly, to the emerging specialist literature around the asset management industry; and secondly, to more general debates about how financial firms influence regulation. We are particularly interested in emphasizing the currently underspecified political influence of asset managers: how the absence of shared understandings of the effects of their business practices on systemic events opens spaces for recognitional politics (cf. Macartney et al., Citation2020). The paper is structured as follows. We begin by exploring original conceptual themes of recognitional politics to further differentiate ourselves from the notion of regulatory capture. We explain how BlackRock helped shape the lens through which the asset management industry was seen, hoping that this would influence its place in the regulatory landscape. Three empirical sections subsequently show how this instance of successful recognitional politics worked in practice, as the relevant regulations crystallized across three distinct but nonetheless co-evolving moments of change. Against the initial backdrop of uncertainty about who would win the inter-institutional regulators’ struggle, BlackRock found increasingly creative ways in the first two moments to distinguish asset management from both banking and shadow banking. Only when it looked relatively assured that asset managers would remain under the instruction of securities regulators did BlackRock explicitly situate itself in a third moment within the nascent category of safe and desirable market-based finance. The Scottian language we develop below identifies these strategies as those of the shape-shifter and chameleon respectively.

Beyond regulatory capture to recognitional politics

The question of how special interests influence state policy is the domain of the regulatory capture literature (Dal Bó, Citation2006). Definitively charting such influence has proved elusive, however, leading critics to question the cause altogether. Our alternative account suggests that private actors – under select circumstances – can introduce ambiguity into regulatory debates, so that the regulatory community might begin to doubt how useful its current cognitive lenses are (Babic et al., Citation2022, p. 134). This appears particularly effective in the context of inter-institutional disputes about who owns a particular area of regulation (see Quaglia, Citation2022). Contrary to the implications of the regulatory capture literature, private actors might not get to choose their own regulations, but they might be able to reshape the prevailing fields of vision to enhance the likelihood of their preferred authority doing the regulating. We understand this as an instance of successful recognitional politics.

Although its history has yet to be written in such a way, the modern state form is deeply influenced by recognitional politics. Reflecting on his 1998 classic, Seeing Like a State, Scott (Citation2021, p. 509) has recently described the contemporary state as ‘a vast anti-vernacular machine’. It has an interest in legislating out of existence forms of everyday behaviour that its political principals regard as detrimental to smooth societal functioning. Such outcomes depend on first being able to read each individual’s activities against a consistent framework of what is permissible and what is not. An overarching cognitive blueprint is therefore necessary if the state is to render social, economic and political entities ‘legible’, to use Scott’s (Citation1998, p. 2) famous phrase. Seeing Like a State speaks to concerns Scott had prioritized throughout his career – the possibility of agrarian revolution-from-below – but in the way it has entered the political economy and economic sociology literatures it has been turned into something approaching a catch-all explanation of how the regulatory gaze comes into focus from above.

Applying Scott’s concepts beyond their original setting has maybe not worked as well as the proponents of such a move would have liked. Scott himself has been criticized by his fellow anthropologists for seeing too much like a state, giving it ‘credit for more power than it merits’ and conflating it with the broader analytical category of regulatory authority (Klausen, Citation2021, p. 483). He has been happy to ‘plead guilty as charged’: ‘I fear that my book leaves the impression that the state is little more than a “legibility” manufacturing machine’ (Scott, Citation2021, p. 507, 513). In much of the work that has followed Seeing Like a State, the metaphor of sight operates in one direction only: regulatory bodies see only what they want to see (Broome & Seabrooke, Citation2007; Moschella, Citation2012; Vetterlein, Citation2012). Scott’s (Citation2021, p. 512) apparent change of heart on the concept of legibility is therefore of some significance, because it begins to question whether officials can always enlist the targets of policy initiatives into their chosen regulatory optic. He makes it clear that if he were writing Seeing Like a State again today, he would be distinguishing wherever possible between visual order and working order. The former refers to the neat outlines of cognitive blueprints, the latter to the much messier practices of compromise through which actual regulations typically arise. In Scott’s reworked language of legibility, regulators are always likely to have to settle for one of the various ‘shades of gray’ of working order (Carpenter & Moss, Citation2013, p. 9). Given that so many outcomes ultimately rest on the state’s choice of how to see, it is inconceivable that this should not become a site of political struggle. But we can only know on a case-by-case basis how far regulatory authorities will have to retreat from their initial conception of visual order.

Insufficient attention has been placed on what it means ‘to be seen as’ from the perspective of the targets of policy initiatives. This is equally true of specific interventions in the debate about regulatory capture as it is of more general attempts to use Seeing Like a State for conceptual inspiration. Existing empirical studies in both traditions have tended only to ask what the observing institution wishes to see. However, we must expect that anyone newly coming into the state’s chosen optics will attempt to deliberately blur the picture of what officials think they are looking at. What happens when those who the state wishes its regulatory agencies to see in a particular way consciously manufacture doubt about what is visible, shedding their passivity to mobilize to obstruct a clear line of sight?

Scott’s work post Seeing Like a State offers important insights in this regard, especially The Art of Not Being Governed. This is the only one of his other books in which the metaphor of sight is anywhere near as prominent. But the direction of agency is reversed. In Seeing Like a State, peasants, hill tribes and traditional elders are all present, but they almost never exercise agency in response to the state’s anti-vernacular intentions (Hurst, Citation2021, p. 499). They are rendered inert by an all-powerful policymaking apparatus, disoriented by everything being done to them, and generally stripped of strategic calculation about how best to organize themselves in response. In The Art of Not Being Governed, by contrast, the same people are afforded much more agency to deny particular forms of recognition by the state. They are forever creating spaces of uncertainty between existing and newly announced regulations, seeking to benefit from contrived ambiguity in the state’s process of sight (Lee, Citation2015, p. 43). Scott (Citation2009, pp. 207–219) writes in this regard about carefully constructed ‘social structures of escape’.

The key visual metaphors marking the change in focus between the two books are those of shape-shifting and disappearing. In The Art of Not Being Governed, Scott celebrates the success of highland tribes in southeast Asia in rendering themselves at most only partially known to lowland governing authorities seeking to incorporate them into a legibility code. ‘Like a chameleon’s color adapting to the background’, he writes, ‘a vague and shape-shifting identity has great protective value and may, on that account, be actively cultivated’ (Scott, Citation2009, p. 256). Scott appears to elide metaphors in this instance, as changing form like a shape-shifter and disappearing like a chameleon imply different things: being seen as something else versus no longer being able to be seen at all. It appears to be this multifaceted technique of evasion that Scott (Citation2009, p. 209) has in mind when he writes: ‘when nonstate peoples (a.k.a. tribes) face pressures for political and social incorporation into a state system, a variety of responses is possible … They may, of course, fight to defend their autonomy … [or] they may make themselves invisible or unattractive as objects of appropriation’. The tribes he studied alternated strategically between ‘relative stateness and statelessness’, making themselves visible for certain purposes but invisible for others (Scott, Citation2009, p. 164). They perfected what might be called an anti-anti-vernacular approach, never revealing themselves in their totality to observing others, oscillating between distinguishing themselves from the intended subjects of the state’s legibility efforts and disappearing from the gaze of authorities altogether. This is a prime example of what we call recognitional politics.

As the 2010s progressed, BlackRock employed these two tactics – of shape-shifting and disappearing – in its interventions in debates about the regulation of the asset management industry. Its preference for remaining only within securities regulators’ line of sight meant that it had to be active in convincing prudential regulators that it remained outside their alternative way of seeing. These moments were characterized by shape-shifting: seeking to intervene in defining the risks authorities were searching for, before actively telling authorities ‘we are not that kind of industry’. Successful shape-shifting in this instance meant only that it was no longer on prudential regulators’ radar, rather than that it had escaped all regulations. One aspect of BlackRock’s recognitional politics thus involved rejecting any association with bank-like entities, at the same time as adding its voice to early demands that such entities be subjected to newly restrictive legislation following their role in the global financial crisis. This was a far more subtle Janus-faced discursive strategy than is typically evidenced in accounts of harder forms of regulatory capture. ‘Asset managers and regulators have a shared interest in ensuring potential risks to financial stability are mitigated’, BlackRock (Citation2016, p. 1) declared, making clear it was ‘interested in pursuing solutions that improve market stability and soundness’. If anything, it urged regulators to go further, supporting ‘additional reforms that address systemic risks’ (BlackRock, Citation2014c, p. 1).

Yet, this ultimately was revealed to be about regulating financial industries other than its own. BlackRock joined an industry chorus in insisting that the regulators’ focus shift from targeting institutions to targeting activities. The status of the firm as a bank-like entity was not a problem in itself; it was a question of whether the positions on its balance sheet created systemic risk that might lead to instability. BlackRock’s claim that it was not a bank seems reasonable, but its related argument that because it was not a bank it did not carry systemic risk is more dubious. Its early shape-shifting appears to have been based on a false equivalence. A key feature of this approach was to increasingly present its own industry as a sanitized viable credit alternative. This involved discursive hopping to use initial arguments about what it was not as inbuilt justification for eventually asserting that asset managers limited themselves to systemically safe activities within market-based finance. The chameleon’s disappearing strategy described by Scott thus became apparent. As a clearer context took shape in the minds of authorities, BlackRock found it considerably easier to blend into the unassuming landscape of safe, plain-vanilla financial activities. BlackRock spoke a technical language to effect such camouflaging outcomes. Its elaborate characterization of banking processes that were based on both runnable deposits and excessive leverage strategically emphasized the risks beyond their sheltered realm of asset management. These artful manoeuvres – represented pictorially in – allowed them to seemingly vanish from the scrutiny of prudential regulators while blending into the background of securities regulators’ existing legibility code (e.g., BlackRock, Citation2014a, Citation2015a, Citation2018). The shape-shifter and the chameleon were therefore active simultaneously (see Appendix).

From banking to market-based finance, moment 1: Post-crisis banking regulation

This first empirical section traces the asset management industry’s successful efforts to shape the SIFI (systemically important financial institution) debate through a counter-legibility project. Spearheaded by the newly created FSOC in the United States, the process for the ‘supervision and regulation of certain nonbank financial companies’ began in October 2010 (FSOC, Citation2012). At this early stage, the asset management industry contended that it was ‘unlikely to pose a threat to US financial stability’ (FSOC, Citation2012), because it was ‘not vulnerable to significant liquidity risk or maturity mismatches’ (FSOC, Citation2011). Here, it was objecting to regulators’ attempts to find entities that were sufficiently like banks to incorporate them within the increasingly expansive lens of prudential regulation. Asset managers initially identified as a first distinguishing characteristic banks’ reliance on runnable deposits or short-term wholesale funding; this created solvency risks, they said, to which they were immune because they had no similar reliance.

Despite these objections, in April 2012 the FSOC instructed the Office of Financial Research (OFR) to undertake a report that was always likely to require a more complex response than simply telling prudential regulators they were wrong. Published in September 2013, it acknowledged that although asset managers differ from banks in some ways, there were also important similarities, ‘including that they both hold money-like liabilities that might expose asset managers to the same types of runs as banks’ (Ryan, Citation2014; see OFR, Citation2013). In addition, the struggle to enhance supervision of asset managers centred on a desire by the OFR (and FSOC) to avoid future government bailouts of any financial institution (BlackRock, Citation2014b, p. 2). In prudential regulators’ minds, any institution that could experience outflows akin to a bank run was likely to require central bank intervention at some point, and thus should fall under the same form of regulation. The OFR study was met with widespread criticism from the asset management industry for its ‘alarmist portrait’ (Forbes, Citation2013) based on ‘a litany of nightmare closet “could happens”’ (Financial Times, Citation2013). Here we see the first signs of an explicit counter-legibility political strategy emerging, with the suggestion that whatever prudential regulators’ favoured legibility template allowed them to see, it was not the world that the asset management industry inhabited. At this point, what Scott (Citation2009, p. 219) calls ‘utter plasticity’ began to inform the first moment of the industry’s response.

As BlackRock recognized, there were obvious strategic incentives in keeping asset management within the purview of securities regulation (Quaglia, Citation2022). To do so, it chose not to promote what might be expected in a case of regulatory capture, an obviously self-centred agenda emphasizing that it was too important to the overall efficiency of the financial system to have its activities curtailed. Instead, it highlighted what it said was the misleading conflation of asset management and banking within prudential regulators’ legibility template (BlackRock, Citation2014a, p. 2). In addition to the idea of short-term runnable deposit risk that plagued the banking system, it added another risk category inherent to banking: the issue of leverage. Highly leveraged bank balance sheets were indicative of high interconnectedness, threatened contagion and systemic risk. BlackRock emphasized, by way of contrast, that asset managers do not use runnable short-term funding and do not have an asset-liability mismatch on their balance sheets. As they do not use their own balance sheets, they do not act as the counterparty in trades or derivatives transactions, allowing BlackRock (Citation2015a, p. 11) to assert that they have significantly lower risk exposures than the banks that failed during the financial crisis. BlackRock (Citation2014c, p. 6, emphasis added) stressed that ‘the vast majority of regulators now pondering how to design appropriate macro-prudential regulation for the financial system have assimilated the banking model deeply into their thinking. Yet it is precisely on this axis that banks and asset managers are fundamentally different … [since] the bank as the asset owner is a principal, not an agent’.

By late 2014, the FSOC acknowledged that its legibility template was inadequate and that its policy priorities were now a non-starter, choosing to abandon the SIFI designation of asset managers as its preferred form of recognition. Asset managers’ efforts appeared to have paid dividends, with the FSOC (Citation2016, p. 5) admitting that industry participants at the May 2014 conference had ‘helped shape the Council’s approach to its work’. The focus in the US pivoted away from regulating at the institutional level in the face of successful discursive positioning as ‘not a bank’; industry representatives’ successful shape-shifting had nudged prudential regulators towards an activities-based approach.

BlackRock’s defence – that asset managers engage in practices fundamentally different from banking – was applied at the global level too. Global efforts around SIFI designation also began in 2010 when the G20 leaders endorsed a framework established by the FSB (Citation2010). The G20 tasked the FSB, in consultation with IOSCO, ‘to prepare methodologies to identify systemically important non-bank financial entities’ (G20, Citation2011). In a first consultative document in January 2014, the proposals replicated ideas presented in the much-maligned US OFR report (SEC, Citation2014, p. 7).

The FSB’s approach thus again threatened to derail the asset management industry’s attempt to present itself in shape-shifting terms as ‘not a bank’, but it proved equally as susceptible as the OFR to a counter-legibility political strategy. Once more, the recognitional politics enacted by the asset management industry revolved around the shape-shifter’s argument that it was wholly different from how it was being seen. Its key concern was that the FSB linked systemic risk to the size of individual institutions such as investment funds, rather than to their activities. To mobilize against the FSB’s approach, asset managers sought to return to the issue of banking practices that had proved so successful in the US regulatory debate. BlackRock (Citation2014b, p. 1) reiterated arguments that asset managers were neither the owner of the assets nor the counterparty to trades, meaning that ‘Asset Managers are not a source of systemic risk’. The Investment Company Institute (ICI), the trade association of the industry, was even more scathing. It argued that the FSB’s proposed reforms ‘may be far broader than necessary and sweep beyond any demonstrable risks’, and that they attempted ‘to paint the entire canvas of the financial system with a single broad brush’, thus ‘dramatically expand[ing] the authority of bank regulators’ (ICI, Citation2014, p. 1). The attack was on the entire legibility template and the selective vision it implied that everything should be treated as a bank. As the ICI (Citation2014, p. 2, original emphasis) highlighted, in the US the FSOC had only considered SIFI designation ‘in rare and compelling cases’, hoping this would serve as a benchmark for the FSB. Victories won in the struggle over legibility codes at the national level thus risked being undermined by a second wave of global regulatory efforts.

In response to these criticisms the FSB reconsidered its original strategy, coming round to the idea that it had initially misjudged the financial stability risks associated with the asset management industry. Mobilization by the industry, allied with sympathetic support from, most notably, the US SEC, was proving effective (Financial Times, Citation2015a). But, at this stage, only on this specific point. The FSB (Citation2015a) was yet to end its interest in SIFI designation, provoking even stronger condemnation than previously from private firms that knew they had much to lose from such an outcome. BlackRock (Citation2015b, p. 3) again argued that ‘Asset Managers are fundamentally different from banks and other financial institutions’. The ICI (Citation2015, p. 2) also repeated its concern about ‘the continued propensity of banking-oriented regulators in various jurisdictions and on the global stage to view the asset management industry through the lens of banking’. It strenuously objected to the ‘characterization of all portions of the financial system other than banks as mere shadow banks’ (ICI, Citation2015, p. 3), a point we return to in the following section. It went further to argue that previous objections raised by the asset management industry had done little to have ‘“moved the dial” in terms of the FSB’s thinking’, as the proposed methodologies for investment funds and asset managers remained ‘firmly rooted in the banking mindset’ (ICI, Citation2015, p. 3). The result, in the ICI’s (Citation2015, p. 7) opinion, was that ‘despite every cogent reason to focus on sector-wide activities and practices, the FSB seemed blindly determined to pursue an entity-based approach’, seeking ‘consistency with the treatment of banks’.

Then, on 16 June 2015 a decisive blow was struck by IOSCO (Citation2015), when it endorsed the approach proposed by the asset management industry and challenged the SIFI designation process of the FSB. In clarifying its position, the Board’s chairman noted that ‘we don’t regulate the markets like we regulate the banks’ (cited in Financial Times, Citation2015b). Shortly after, the FSB then announced that it had ‘decided to wait to finalise the assessment methodologies for non-bank non-insurer global systemically important financial institutions (NBNI G-SIFIs) until the current FSB work on financial stability risks from asset management activities was completed’ (FSB, Citation2015a, p. 1). The decision to pause the G-SIFI inquiry was a major step-down for the FSB, again equivalent to rendering its own legibility templates obsolete, and a significant affirmation of the industry’s shape-shifting strategies. Most importantly, by 2017, the FSB had adopted language consistent with the recognitional demands of the largest private firms. It noted that ‘asset managers and their funds pose very different structural issues from banks and insurance companies. In contrast to banks and insurance companies, which act as principals in the intermediation of funds, asset managers usually act as agents on behalf of their clients’ (FSB, Citation2017, p. 8, original emphases). ‘This different structure of the asset management sector’, it continued, ‘offers some important stabilising features to the global financial system’ (FSB, Citation2017, p. 9). The counter-legibility template was thus accepted as the regulators’ new legibility template. As BlackRock (Citation2020, p. 11) concluded in a discreet nod to its successful recognitional politics, regulatory institutions had ‘pivoted … towards a products and activities approach as the most effective way of mitigating risks in asset management’. The industry had contributed to the prudential framing of banks as sources of risk, while shape-shifting to ensure that it was immune from being seen in similar terms, even though its members could be simultaneously not-banks and agents of systemic instability.

From banking to market-based finance, moment 2: Shadow banking regulation

In parallel to the SIFI debate, regulatory discussion around the question of shadow banking picked up during the 2010s. Initially, authorities opted to ‘cast the net wide’ with a ‘broad definition’ that captured ‘the system of credit intermediation that involves entities and activities outside the regular banking system’ (FSB, Citation2011). The new but often opaque terminology of shadow banking presented its own problems for the asset management industry. There was a danger to asset managers that if they were not seen as banks, then they would still be seen as bank-like institutions – those that engaged in shadow banking processes and thus posed similar risks to banks. To address this challenge, the asset management industry followed a strategy that mirrored what we have already seen in the SIFI debate, overlapping with it in real time (see Appendix). Firstly, BlackRock denied that specific institutions from within the asset management universe posed systemic risks; secondly, it sought to refocus the debate on activities rather than institutions, attempting to identify practices common to shadow banks and banks but alien to asset management. The first of these shape-shifting moves began to sow doubt about whether prudential regulators’ legibility templates were really fit for purpose; the second aimed to move asset managers beyond the parameters of prudential regulation altogether. This strategy involved accelerated discursive hopping between different sets of claims, whereby asset managers only revealed small parts of themselves when they fell into the line of sight of what they considered the ‘wrong’ regulators.

In November 2010, G20 leaders highlighted strengthening regulation and supervision of shadow banking as a main priority for the FSB (Citation2011). The concern in the United States was that this parallel system lacked official access to public liquidity backstops despite being ‘susceptible to disruptions that threaten financial and economic stability’ (FDIC, Citation2012, p. 2). Thus, while officially shadow banks lacked access to public safety nets, de facto they were seen to pose systemic risks which would require public-sector intervention.

This expansive definition of shadow banking was immediately unpopular with the asset management industry. Initially, in 2011, the ICI responded to US authorities, criticizing the view that money market funds ‘lurk in a seemingly unregulated world of shadow banking’ (ICI, Citation2011). As money market funds (MMFs) were part of the asset management universe, their simultaneous inclusion within shadow banking threatened to blur the neat separation between the two domains that asset managers were keen to maintain. Reinstating the clarity of this distinction was crucial for the discursive manoeuvrings about how they should be seen, and which regulators should recognize them as liable for oversight. Accordingly, they contended that it was ‘time to stamp out the confusion around shadow banking’ (ICI, Citation2011). A year later, asset managers responded to the European Commission’s Green Paper on Shadow Banking with similar concerns. In particular, the ICI expressed misgivings that ‘the use of the term shadow banking to describe the system of market-based financing discussed in the green paper continues to be merely an epithet, connoting that all activities so labelled lack both transparency and any regular or official status and casting a pejorative tone on the system of credit intermediation’ (ICI, Citation2012, p. 1).

To counter the threat posed by the likely inclusion of institutions such as money market funds within the shadow banking category, the ICI appealed to the precedent established in the SIFI designation debate: that regulatory scrutiny should not pertain to institutions, but rather to activities. The counter-legibility political strategy was dusted down and used again in pursuit of further shape-shifting. The ICI asserted that the ‘attempt to view capital markets financing through the lens of banking regulation distorts its character and makes it more difficult for regulators and policymakers to assess the nature of the risks in this system and the potential threats to financial stability that the aggregate of the two systems could present’ (ICI, Citation2012, p. 2). The application of a bank regulation mindset to shadow banks as institutions prompted similar criticisms from asset managers to those raised earlier in our analysis.

This time, however, the lack of consensus around shadow banking made it more difficult to deflect attention from certain types of institutions. If the definition of banking, from prudential regulators’ perspective, was relatively clear from the outset and the emphasis of the asset management industry’s efforts was therefore to argue that asset managers were not banks and therefore needed to be regulated differently, shadow banking proved more problematic for the industry to address. There was a background to blend into after some simple shape-shifting in the former case, but not the latter; regulators had turned the background into a moving target, requiring asset managers to enact more complex shape-shifting in response. As one critic argued, ‘a shadow banking bandwagon [had] gathered steam and [was] rolling around like a loose cannon ready to crush non-bank entities that were involved in the financial crisis regardless of whether they had anything to do with its causes’ (Fein, Citation2012, p. 2). Concerted self-redefinition to impose clear lines of demarcation was the chosen strategy to derail the bandwagon, but this was not without its problems. The differences between asset management and shadow banking proved difficult to maintain, because regulators were only just developing new frames for each category. Where a strong legibility code for what constitutes banking already existed, it did not for shadow banking, forcing asset managers to rehearse their not-a-shadow-bank mantra every time prudential regulators adjusted their line of sight.

By 2013–2014, criticisms of the expansive definition of shadow banking started to bear fruit. The FSB narrowed its focus ‘by filtering out non-bank entities and activities that do not pose bank-like risks to financial stability’ (FSB, Citation2013, p. 5). This refined the selective vision embedded in its legibility template accordingly, allowing the asset management industry to shape-shift in line with ways of seeing that fell outside the remit of prudential regulation. In other words, the same change that would ultimately take place in the SIFI designation process – away from institutions and towards activities-based regulation – was already starting to unfold in the shadow banking debate, with institutions being examined ‘by function rather than entity’ (Kodres, Citation2019). The turn towards activities allowed BlackRock to recycle the by now familiar critique that banking processes – notably a runnable deposit base, extensive leverage, and the need for central bank backstops – underpinned the operation of banks and shadow banks alike, but not those of asset management. This second moment was characterized by sustained efforts by asset managers to argue that their activities stood them apart from institutions that rightly fell within prudential regulators’ optics.

In repeatedly changing form when faced with prudential regulators’ evolving legibility code to position itself as something other than a shadow bank, BlackRock began to invoke a line of argument traditionally used by the banking sector to counter more stringent regulation (Hardie & Macartney, Citation2016). It stressed that ‘applying bank-like regulation could be harmful to the real economy. This is because bank-like regulation entails restrictions and costs that will be borne by investors’, which may in turn ‘discourage investment’ (BlackRock, Citation2018, p. 4). By promoting a positive role for the real economy, though, BlackRock acknowledged that it could not simply present itself as not a bank and not a shadow bank. Instead, a positive identifier was needed to make sure that asset management would be seen as useful for the real economy. Its recognitional politics strategy therefore increasingly married constant changes of form to keep prudential regulators guessing how they would present themselves next with an attempt to disappear within securities regulators’ existing legibility codes for market-based finance. The refusal strategy of the Scottian shape-shifter thus increasingly became the more acquiescent strategy of his chameleon.

From banking to market-based finance, moment 3: The embrace of market-based finance

In specifying a positive vision for its industry, BlackRock followed the regulatory community’s turn away from the broad definition of shadow banking and towards an alternative framing that already existed on the margins of debates: that of ‘market-based finance’. Already in 2012, the FSB acknowledged that while shadow banking had become the commonly employed term, it was controversial. Its negative connotations threatened to undermine the idea that non-bank credit ‘intermediation, appropriately conducted, provides a valuable alternative to bank funding that supports real economic activity’ (FSB, Citation2012). The idea that market-based finance could provide a sanitized version of shadow banking received new impetus in the G20 St Petersburg Summit Declaration in September 2013, which emphasized the need to develop a policy framework for monitoring and regulating non-bank credit intermediation. Drawing on this idea, in 2014 the FSB published a revealingly titled progress report, Transforming shadow banking into resilient market-based financing. The intention of this project, it argued (FSB, Citation2015b, p. 1), was ‘to build safer, more sustainable sources of financing for the real economy’, if properly regulated (see Engelen, Citation2017).

For asset managers, a primary interest was to distinguish the purportedly low-risk and sustainable nature of market-based finance from systemically risky and crisis-prone shadow banking. To create a distinguishing characteristic, BlackRock sought to intervene in the burgeoning discussion around liquidity and leverage in post-crisis regulatory circles. Reframing the relevance and nature of liquidity and leverage concerns for the asset management industry became the means of enforcing a positive self-designation. Denying the relevance of such systemically risky practices – and thus for central bank backstops – provided further support for its previous negative not-a-bank and not-a-shadow-bank self-designations, while blending into the background of safe, market-based finance. Chameleon tendencies thus became more likely, because as the framing of market-based finance became more secure, asset managers could disappear into an increasingly accepted category that was outside prudential regulators’ reach.

Following the crisis, regulators were increasingly distinguishing various forms of liquidity, key amongst them funding liquidity – the ability of institutions to access new funds – and market liquidity – the ability to trade an asset at short notice and with little impact on its price (Brunnermeier & Pedersen, Citation2009). The traditional concern of banking regulators was funding liquidity: if a bank ran into trouble, a lender of last resort could prop up its operations if it was considered illiquid but fundamentally solvent. However, the development of increasingly complex banking practices that combine traditional deposit taking with investment banking activities (such as trading and risk management) shifted regulatory attention to the question of market liquidity. As banks were trading bonds and structured credit products as collateral within markets, fluctuations in collateral asset prices could induce funding pressures that were easily amplified across markets. Within increasingly market-based financial systems, liquidity concerns were thus not limited to individual bank funding positions but rather to their exposure to common asset price swings (Pape, Citation2020), hence why prudential regulators came knocking at asset managers’ doors.

This gave BlackRock added incentive to distinguish between the liquidity risks faced by banks and shadow banks and those faced by asset managers and the funds they manage. To make this distinction – and deny that the systemic interactions between funding and market liquidity could affect asset managers – BlackRock (Citation2015c) proposed an alternative taxonomy of liquidity, which had within it an alternative legibility code. It deemed funding liquidity to be a problem unique to banks and shadow banks, precisely because such institutions relied on substantive asset-liability mismatches: banks and shadow banks ‘hold assets that are funded by temporary financing. Funding liquidity risk is the risk that the entity will be unable to renew the funding (i.e., rollover risk)’ (BlackRock, Citation2015c, p. 3). Given this mismatch, all bank-like entities, whether conventional banks or shadow banks, were prone to runs whenever depositors lost confidence in the institution’s ability to produce sufficient liquid assets to pay liabilities as they came due. By contrast, BlackRock asserted, non-bank financial intermediaries such as mutual funds or investment funds merely faced redemption risks. Similar to funding liquidity risk, redemption risk ‘is the risk that a fund might have difficulty meeting its investors’ requests to redeem their shares for cash’ (BlackRock, Citation2015c, p. 3). The difference is that while banking and shadow banking liabilities promise convertibility at par, other non-bank liabilities such as mutual fund shares ‘fluctuate in value and the shareholders have equal claims to the assets in the fund. If the underlying assets in a mutual fund decline in value, the shares of the fund will decline in line with the underlying assets’ (BlackRock, Citation2017, p. 8). There is plenty to dispute in this claim, given stable net asset values in money market funds which give them a bank-like status. But from BlackRock’s perspective, the specific detail was less important than reinforcing the impression that what distinguished market-based finance from bank-like entities was its in-built immunity from generating systemic risk. Even if mutual funds experienced serious trouble, it said, ‘investors would still be entitled to pro rata shares of the underlying securities or cash generated by the liquidation of the underlying securities’ (BlackRock, Citation2017, p. 8). The key to counteracting such redemption risk, according to BlackRock, was simply to sharpen internal liquidity risk management as a self-regulatory mechanism.

Similarly, BlackRock proposed a reconsideration of market liquidity risks for market-based finance. While macroprudential regulators were proposing intrusive stress-testing exercises for banking institutions, it was adamant that asset management should not be pulled in this particular direction. Stress tests, BlackRock argued in 2017, were designed to mitigate systemic risk. Banks can contribute to systemic risk when fire sales create funding difficulties, thus causing not just market movements but insolvency concerns that, as banks are highly leveraged institutions, can quickly create knock-on effects within the broader financial system. By contrast, as mutual or investment funds do not face such funding liquidity risks, their asset sales are not systemic. In fact, even fire sales by funds should be seen simply as market corrections, BlackRock (Citation2017) maintained. They reflect not the build-up of systemic risk (and thus the object of macroprudential policy), but rather market risks that contribute to healthy price fluctuations. In aiding price discovery, funds are thus contributing to the efficient operation of markets, rather than causing market failure. BlackRock argued that macroprudential interventions which undermine the process of price discovery create systemic risks, as they disrupt the efficient pricing of assets. In this view, macroprudential policies that violate private market risk protocols ‘run counter to investors’ best interests’ and cause investors to retreat, which would ‘likely lead to distortions that ultimately destabilize markets’ (BlackRock, Citation2017, p. 15).

Behind this somewhat technical intervention we can ascertain a clear strategy of seeking to be seen in a specific way, in keeping with the general objective of recognitional politics. In this instance, though, it was to be seen as being unremarkable against the norms of market-based finance, so that asset managers no longer stood out as a potential target of prudential regulation. As they realized, prudential regulators’ growing attention to complex liquidity structures could lead to a situation in which any actor exposed to key asset classes or trading techniques was to be considered a systemic risk factor. To counter such a move, they sought to divorce their industry from the prudential view on liquidity (e.g., Adrian & Shin, Citation2010), so that they would remain outside prudential regulators’ reworked and rapidly expanding legibility templates. Here, BlackRock implicitly latched onto a longstanding division between economics and finance theory in understanding liquidity. Simply put, within economics, liquidity always addresses the scarcity of money: in a downturn, not all credit commitments can be exchanged into money, and the inability to settle all debts manifests itself in the form of financial and economic crisis (Mehrling, Citation2012). The resulting funding or cash-flow shortfall is a key concern to prudential regulators, as it can induce institutional failures with knock-on effects that require substantive public sector interventions. By contrast, finance theory effectively abstracts from cashflow problems: here, the contraction of credit merely registers as price volatility or discontinuity. Liquidity itself is abundant; it is merely a question of finding the right pricing mechanism (Black, Citation1970). From this perspective, liquidity is collapsed into mere risk that can be managed through appropriate portfolio selection and risk management tools, a self-regulatory route.

Critically, BlackRock’s interpretation of liquidity depended on the absence of leverage. Within the banking sector, leverage is highly procyclical: with balance sheets marked-to-market, any change in asset prices immediately shows up on banks’ balance sheets and imprints on their risk management models. A rise in asset prices invites higher leverage, as banks seek to capitalize on their increased risk-taking capacity. Leveraged balance sheets thus enhance gains during asset booms at the cost of magnifying losses when overall conditions change (Adrian & Shin, Citation2010). For the asset management industry, the use of leverage complicates the clean narrative of efficient price discovery, because it amplifies a portfolio’s reaction to price swings. Under such conditions, investors face considerable first-mover advantages when exiting, thereby increasing the likelihood of run-like redemption requests that trigger fire sales. Such risks were not entirely theoretical: at the time, leverage had been growing substantially in exchange-traded funds, as well as in fixed-income and open-ended funds, particularly those focused on emerging markets (Pasqual et al., Citation2021).

In 2016, the FSB (Citation2016, p. 2) addressed the question of leverage as part of a broader set of policy recommendations to rectify ‘structural vulnerabilities from asset management activities’. As it noted, leverage measurements and associated leverage limits varied considerably between types of funds and across jurisdictions. With reporting inconsistent and incomplete, uncertainties remained, especially around the inclusion of off-balance sheet derivatives positions. To streamline the assessment of leverage, the FSB recommended that IOSCO develop a consistent leverage framework. In response, the Global Association of Risk Professionals (GARP) questioned the very viability of a singular leverage framework, stating somewhat stridently that this was the wrong lens through which to see. Unlike banks which shared a level of consistency in the type of practices and investments they made, the investment portfolios of asset managers, it said, varied considerably across asset classes, suggesting that a single measure of leverage would be wholly inadequate to capture their actual risk exposure (GARP, Citation2016). In 2019, BlackRock (Citation2019) cited GARP’s argument approvingly in its own response to IOSCO’s consultation on a new leverage framework. The industry’s position was clear: a new and uniform methodology for measuring leverage was only to be welcomed if it left sufficient space for a wide variety of business practices, into which asset managers would increasingly disappear from prudential regulators’ field of vision.

Confronted with the regulatory push for a unified leverage framework and amidst ongoing questions over the classification of asset managers’ liquidity practices, BlackRock (Citation2018) was forced into a strategic admission in its report, Taking market-based finance out of the shadows. Its key tenet – summarized in a speech by BlackRock vice-chair Barbara Novick in May 2019 – was that ‘non-bank finance should be viewed as a continuum’: ‘at one end of the spectrum is market-based finance – which underpins financial stability; at the other is shadow banking – which presents systemic risk’ (Novick, Citation2019, p. 2). As such, ‘entities that are closer to bank-like activities [but only such entities] may pose systemic risk and should be subject to bank-like regulation’ (Novick, Citation2019, p. 3). BlackRock (Citation2018, p. 6) once again drew on familiar themes: shadow banking was characterized by its reliance on runnable funding liquidity and high levels of leverage, which in turn would require central bank backstops. By contrast, market-based finance relied on ‘unlevered investments in financial instruments’ such as stocks and bonds that ‘provide capital to the real economy without introducing additional risk into the system’. According to this framing, not only was market-based finance unproblematic, but it was also unambiguously socially useful. Yet in defining non-bank finance as a continuum to double down on the assertion that a bank-focused legibility code was mistakenly applied in its case, BlackRock thus implicitly acknowledged that demarcating the boundaries of market-based finance would require continuous policing. The debate about how best to regulate the asset management industry was thus far from conclusively closed down.

Conclusion

As it moved through three distinct moments of recognitional politics, BlackRock engaged more explicitly with the details of the regulatory debate using the technical language of leverage and liquidity. We should not get too distracted, though, by the performative display of legal and economic expertise contained in its numerous discussion papers. This was merely the medium to carry what was, in essence, a straightforward argument: that it knew only too well what it wanted from the resolution of the inter-institutional conflict over who should regulate the asset management industry. Its message to prudential regulators was that they had misunderstood what they thought they were looking at; its message to securities regulators was that their legibility code was based on an acceptable way of seeing (Quaglia, Citation2022). Taking each intervention in isolation, BlackRock’s discursive hopping can seem to embody a purely defensive stance, responding in a reactive fashion to whatever obstacle regulators had most recently placed in its way. Taken in aggregate, though, this apparently scattergun approach is revealed to be intensely forward-looking. BlackRock’s successful recognitional politics manufactured such doubt about whether the asset management industry should be regulated as bank-like entities (through moments of shape-shifting) that it eventually felt enabled to declare that it belonged to the category of market-based finance (the moment of disappearing into the background). Its strategy in the purely negative moments was to render itself illegible from the perspective of prudential regulators, but in the positive moment to signal to securities regulators that it already acted in strict accordance with their standards.

Our account in this paper therefore prompts the question of whether BlackRock was actually correct: is the asset management industry qualitatively distinct from banking and shadow banking? Is the industry an unproblematic exponent of market-based finance? If so, was Blackrock justified in asserting that any industry involved in market-based finance poses minimal systemic risks? We have no space to answer this question comprehensively, but our sceptical account of BlackRock’s representation of leverage and liquidity risk aligns with emerging themes in the critical financial economics literature which point to the very real possibility that, under certain conditions, the asset management industry can indeed pose system-wide threats. As a result, an appropriate process for designating systemically important financial institutions within the industry is still required (De Smet, Citation2022).

This dynamic and, indeed, ongoing struggle fits well with our notion of recognitional politics, which itself has potentially wide applicability. Certainly, giant tech platforms and cryptocurrency firms also seem to have used similar strategies to produce outcomes analogous to those depicted in the regulatory capture approach, but without regulatory capture per se being the means of approaching their goal. The common feature in all these instances appears to be that newly emerging or rapidly growing industries draw particular attention from regulatory agencies, questioning how they fit within existing legibility architectures. Our case shows the value of extending the recognitional politics approach to produce more nuanced and historically specific readings of the cognitive and ideological mechanisms in operation across all these settings. Inspired by Scott’s reworked concept of legibility and the political agency exemplified by shape-shifters and chameleons, we highlight how complex techniques of discursive hopping influence the broad parameters of regulatory debates rather than seeking to exercise direct control over which policies come to pass.

There is still nothing to suggest, though, that the asset management industry’s successful recognitional politics strategy from the 2010s will prove a one-and-done thing. Additional research will be required to adjudicate on whether moments of recognitional politics become less pronounced after an initial burst of energy, or whether they prove to be more cyclical. After all, future iterations of financial innovation are likely to push the boundaries of asset managers’ activities ever further outwards, so that they might once again attract the attention of prudential regulators. The asset management industry has secured one apparently unlikely victory by persuading the regulatory community in the face of contradictory evidence that it does not consist of systemically important financial institutions. Yet this will not prevent the same question being asked of it again if market-based finance becomes associated with the next crisis. If anything at all is guaranteed here, it is that the shape-shifter and chameleon will likely have to reassert themselves on further occasions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for research support provided by Martha Courtauld (May–June 2021). Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the European University Institute, Florence (October 2023) and the University of Edinburgh (February 2024). We thank the participants of both workshops as well as four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Huw Macartney

Huw Macartney is Associate Professor of Political Economy at the University of Birmingham.

Fabian Pape

Fabian Pape is a Fellow in International Political Economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Matthew Watson

Matthew Watson is Professor of Political Economy at the University of Warwick.

References

- Adrian, T. & Shin, H. S. (2010). Liquidity and leverage. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 19(3), 418–437.

- Babic, M., Huijzer, J., Garcia-Bernardo, J. & Valeeva, D. (2022). How does business power operate? A framework for its working mechanisms. Business and Politics, 24(2), 133–150.

- Baines, J. & Hager, S. B. (2023). From passive owners to planet savers? Asset managers, carbon majors and the limits of sustainable finance. Competition & Change, 27(3-4), 449–471.

- Baker, A. (2013). The new political economy of the macroprudential ideational shift. New Political Economy, 18(1), 112–139.

- Black, F. (1970). Fundamentals of liquidity. University of Chicago Press.

- BlackRock. (2014a). Letter to SEC Secretary Lew. Retrieved from https://www.sec.gov/comments/am-1/am1-35.pdf

- BlackRock. (2014b). Comments on the consultative document of assessment methodologies for identifying non-bank non-insurer global systemically important financial institutions. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/r_140423h.pdf

- BlackRock. (2014c). Who owns the assets? Developing a better understanding of the flow of assets and implications for financial regulation. ViewPoint. Retrieved from https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/viewpoint-who-owns-the-assets-may-2014.pdf?n=90737

- BlackRock. (2015a). BlackRock response, re notice seeking comment on asset management products and activities (FSOC 2014-0001). Retrieved from https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/publication/fsoc-request-for-comment-asset-management-032515.pdf

- BlackRock. (2015b). Comments on the consultative document (2nd) assessment methodologies for identifying non-bank non-insurer global systemically important financial institutions. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/BlackRock.pdf

- BlackRock. (2015c). Addressing market liquidity. ViewPoint. Retrieved from https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/viewpoint-addressing-market-liquidity-july-2015.pdf

- BlackRock. (2016). Comments on the consultative document for proposed policy recommendations to address structural vulnerabilities. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/BlackRock1.pdf

- BlackRock. (2017). Macroprudential policies and asset management. ViewPoint. Retrieved from https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/viewpoint-macroprudential-policies-and-asset-management-february-2017.pdf

- BlackRock. (2018). Taking market-based finance out of the shadows. ViewPoint. Retrieved from https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/viewpoint-taking-market-based-finance-out-of-the-shadows-february-2018.pdf

- BlackRock. (2019). Public comment on IOSCO report: Leverage. Retrieved from https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/publication/iosco-public-comment-on-iosco-report-leverage-020119.pdf

- BlackRock. (2020). Lessons from COVID19: Overview of financial stability and non-bank financial institutions. ViewPoint. Retrieved from https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/viewpoint-lessons-from-covid-overview-financial-stability-september-2020.pdf

- Bonizzi, B. & Kaltenbrunner, A. (2024). International financial subordination in the age of asset manager capitalism. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 56(2), 603–626.

- Boston Consulting Group. (2023). The tide has turned: Global asset management 2023. Retrieved from https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/the-tide-has-changed-for-asset-managers

- Braun, B. (2022). Exit, control, and politics: Structural power and corporate governance under asset manager capitalism. Politics & Society, 50(4), 630–654.

- Broome, A. & Seabrooke, L. (2007). Seeing like the IMF: Institutional change in small open economies. Review of International Political Economy, 14(4), 576–601.

- Brunnermeier, M. K. & Pedersen, L. H. (2009). Market liquidity and funding liquidity. Review of Financial Studies, 22(6), 2201–2238.

- Carpenter, D. & Moss, D. A. (Eds.). (2013). Introduction. In Preventing regulatory capture: Special interest influence and how to limit it (pp. 1–22). Cambridge University Press.

- Dal Bó, E. (2006). Regulatory capture: A review. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 22(2), 203–225.

- De Smet, J. (2022). The systemic importance of asset managers: A case study for the future of SIFI regulation. European Business Law Review, 35(2), 227–262.

- Engelen, E. (2017). How shadow banking became non-bank finance. In A. Nesvetailova (Ed.), Shadow banking: Scope, origins and theories (pp. 40–74). Routledge.

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). (2012). Restructuring the banking system to improve safety and soundness. Thomas Hoenig and Charles Morris. Retrieved from https://www.fdic.gov/about/learn/board/restructuring-the-banking-system-05-24-11.pdf

- Fein, M. (2012). The shadow banking charade. Retrieved from https://www.sec.gov/comments/s7-04-09/s70409-95.pdf

- Fichtner, J. & Heemskerk, E. M. (2020). The new permanent universal owners: Index funds, patient capital, and the distinction between feeble and forceful stewardship. Economy and Society, 49(4), 493–515.

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2010). Reducing the moral hazard posed by systemically important financial institutions: FSB recommendations and time lines. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/r_101111a.pdf?page_moved=1

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2011). Shadow banking: Scoping the issues: A background note of the Financial Stability Board. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/r_110412a.pdf

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2012). Global shadow banking monitoring report 2012. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/r_121118c.pdf

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2013). Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report 2013. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/r_131114.pdf

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2015a). Public response to the March 2015 consultative document: Assessment methodologies. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/2015/06/public-responses-to-march-2015-consultative-document-assessment-methodologies-for-identifying-nbni-g-sifis/

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2015b). Transforming shadow banking into resilient market-based financing: An overview of progress. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/shadow_banking_overview_of_progress_2015.pdf

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2016). Consultative document: Proposed policy recommendations to address structural vulnerabilities from asset management activities. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/FSB-Asset-Management-Consultative-Document.pdf

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2017). Policy recommendations to address structural vulnerabilities from asset management activities. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/FSB-Policy-Recommendations-on-Asset-Management-Structural-Vulnerabilities.pdf

- Financial Stability Board. (2021). Lessons learnt from the COVID-19 pandemic from a financial stability perspective. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P130721.pdf

- Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). (2011). Authority to require supervision and regulation of certain non-bank financial companies: Summary. Retrieved from https://www.regulations.gov/document/FSOC-2011-0001-0045

- Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). (2012). Authority to require supervision and regulation of certain non-bank financial companies. Retrieved from https://www.regulations.gov/document/FSOC-2011-0003-0017

- Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). (2016). Minutes of the FSOC. Retrieved from https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/261/April%2018%2C%202016%20Minutes.pdf

- Financial Times. (2013). Asset managers fear more oversight from US Treasury. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/789bd516-2ac3-11e3-ade3-00144feab7de

- Financial Times. (2015a). Big US fund managers fight off ‘systemic’ label. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/4cd1e06a-2a44-11e5-acfb-cbd2e1c81cca

- Financial Times. (2015b). Plans to label big fund managers ‘systemic’ in jeopardy. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/bff61c56-14ef-11e5-a51f-00144feabdc0

- Forbes. (2013). Our worst fears about Dodd Frank’s FSOC are being confirmed. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2013/11/26/our-worst-fears-about-dodd-franks-fsoc-are-being-confirmed/?sh=4f8d64e93c86

- G20. (2011). Cannes summit final declaration. Building our common future: The renewed collective action for the benefit of all. Retrieved from http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2011/2011-cannes-declaration-111104-en.html

- Global Association of Risk Professionals (GARP). (2016). GARP leverage letter in response to referenced consultative document. Retrieved from https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/Global-Association-of-Risk-Professionals-GARP.pdf

- Haldane, A. (2014, April 4). The age of asset management. Speech at the London Business School. Retrieved from https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2014/the-age-of-asset-management.pdf?la=en&hash=673A53E92A9EB43E5689ED7BE33628F62C4871F1

- Hardie, I. & Macartney, H. (2016). EU ring-fencing and the defence of too-big-to-fail banks. West European Politics, 39(3), 503–525.

- Hurst, W. (2021). Reflecting upon James Scott’s Seeing like a state. Polity, 53(3), 498–506.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2020). Central bank support to financial markets in the coronavirus pandemic. Special series on COVID-19. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/covid19-special-notes

- International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO). (2015). Meeting the challenges of a new financial world. Retrieved from https://www.iosco.org/news/pdf/IOSCONEWS384.pdf

- Investment Company Institute (ICI). (2011). Time to stamp out the confusion around ‘shadow banking’. Retrieved from https://www.ici.org/viewpoints/view_11_mmfs_fsb

- Investment Company Institute (ICI). (2012). European Commission green paper on shadow banking. Retrieved from https://www.ici.org/doc-server/pdf%3A26243.pdf

- Investment Company Institute (ICI). (2014). Assessment methodologies for identifying non-bank non-insurer global systemically important financial institutions: Proposed high-level framework and specific methodologies. Retrieved from https://www.ici.org/doc-server/pdf%3A14_ici_fsb_gsifi_ltr.pdf

- Investment Company Institute (ICI). (2015). Consultative document (2nd): Assessment methodologies for identifying non-bank non-insurer global systemically important financial institutions: Proposed high-level framework and specific methodologies. Retrieved from https://www.ici.org/doc-server/pdf%3A15_ici_fsb_comment.pdf

- James, S. & Quaglia, L. (2023). Epistemic contestation and interagency conflict: The challenge of regulating investment funds. Regulation & Governance, 17(2), 346–362.

- Klausen, J. C. (2021). Seeing too much like a state? Polity, 53(3), 476–484.

- Kodres, L. (2019). Shadow banks: Out of the eyes of regulators. Finance and Development Papers. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Back-to-Basics/Shadow-Banks

- Kwak, J. (2014). Incentives and ideology. Harvard Law Review Forum, 127(7), 253–258.

- Lee, M. N. M. (2015). Dreams of the Hmong Kingdom: The quest for legitimation in French Indochina, 1850–1960. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Macartney, H., Howarth, D. & James, S. (2020). Bank power and public policy since the financial crisis. Business and Politics, 22(1), 1–24.

- Mehrling, P. (2012). The inherent hierarchy of money. In L. Taylor, A. Rezai & T. Michl (Eds.), Social fairness and economics: Economic essays in the spirit of Duncan Foley (pp. 394–404). Routledge.

- Moschella, M. (2012). Seeing like the IMF on capital account liberalisation. New Political Economy, 17(1), 59–76.

- Novick, B. (2019). Remarks at the OeNB macroprudential policy conference: ‘Agnostic on non-banks?’ Retrieved from https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/publication/barbara-novick-remarks-oenb-macroprudential-policy-conference-050919.pdf

- Office of Financial Research (OFR). (2013). Asset management and financial stability. Retrieved from https://financialresearch.gov/reports/files/ofr_asset_management_and_financial_stability.pdf

- Pagliari, S. & Young, K. (2016). The interest ecology of financial regulation: Interest group plurality in the design of financial regulatory policies. Socio-Economic Review, 14(2), 309–337.

- Pape, F. (2020). Rethinking liquidity: A critical macro-finance view. Finance and Society, 6(1), 67–75.

- Pasqual, A., Singh, R. & Surti, J. (2021). Investment funds and financial stability: Policy considerations. International Monetary Fund Departmental Paper No. 2021/018. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/09/13/Investment-Funds-and-Financial-Stability-Policy-Considerations-464654

- Quaglia, L. (2022). The perils of international regime complexity in shadow banking. Oxford University Press.

- Ryan, D. (2014). Nonbank SIFIs: No solace for US asset managers. Harvard Law School Forum. Retrieved from https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2014/03/27/nonbank-sifis-no-solace-for-us-asset-managers/

- Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press.

- Scott, J. C. (2009). The art of not being governed: An anarchist history of upland Southeast Asia. Yale University Press.

- Scott, J. C. (2021). Further reflections on Seeing like a state. Polity, 53(3), 507–514.

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (2014). Public feedback on OFR study on asset management issues. Retrieved from https://www.sec.gov/comments/am-1/am1-52.pdf

- Thiemann, M. (2024). Taming the cycles of finance? Central banks and the macro-prudential shift in financial regulation. Cambridge University Press.

- Vetterlein, A. (2012). Seeing like the World Bank on poverty. New Political Economy, 17(1), 35–58.

- Wagner, W. (2010). Administrative law, filter failure, and information capture. Duke Law Journal, 59(7), 1321–1432.