ABSTRACT

The collecting and cultural signification of oriental manuscripts in nineteenth-century Britain are a hitherto under-researched field that is ripe for re-evaluation in the light of postcolonial theory. The Bibliotheca Lindesiana, assembled by the twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth earls of Crawford in the years coterminous with Victoria’s reign, contained one of largest and most diverse collections of oriental manuscripts in Britain. This paper deploys the Bibliotheca Lindesiana as a case study in order to investigate the motives and mechanisms which underlay the formation of oriental manuscript collections in Victorian Britain, and to explore the diverse ways in which such collections folded into wider issues of race, imperialism and organisations of knowledge. The earls of Crawford are contextualised though comparison with other collectors of oriental books and manuscripts, in terms of their backgrounds, interests, motives and mechanisms of collecting. While they were not intricated in the official structures of orientalism, the earls of Crawford are shown to have engaged with and contributed to wider orientalist discourses through their acquisition of books and manuscripts (some of which were implicated in aggressive imperialism), via their employment of experts to catalogue the material, and in opening the collections to academic investigation.

Introduction

The collecting and cultural signification of oriental manuscripts in nineteenth-century Britain are an under-researched phenomenon. In contrast to the collecting of oriental ceramics, textiles and other applied arts, which have accreted an extensive, critical literature, manuscript studies have hitherto been restricted to profiles of individual collectors and surveys of institutional holdings.Footnote1 This paper will employ the Bibliotheca Lindesiana, the library of the Lindsay family, earls of Crawford, as a case study through which to investigate the motives and mechanisms that propelled the formation of oriental manuscript collections in Victorian Britain, and to explore the diverse ways in which such collections folded into wider issues of race, imperialism and organisations of knowledge.

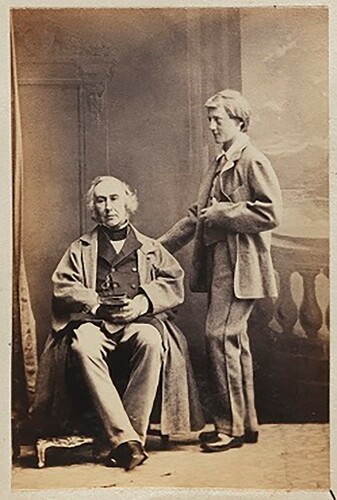

The Bibliotheca Lindesiana, while predominantly a library of European printed materials, contained one of largest and most diverse collections of oriental manuscripts in Britain.Footnote2 In the second half of the nineteenth century, Alexander Lindsay (1812‒80), known for most of his life as Lord Lindsay, and his son (James) Ludovic Lindsay (1847‒1913), respectively twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth earls of Crawford (), amassed over three thousand oriental books and manuscripts. These included large numbers of Middle Eastern manuscripts in Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Samaritan; South Asian works in Sanskrit and numerous modern Indian languages; Chinese and Japanese printed books and manuscripts; texts on palm-leaf, bamboo, bone and copper from South-East Asia; papyri from Egypt in Hieroglyphic, Hieratic, Demotic, Greek, Arabic and Coptic; as well as Syriac, Armenian, Coptic and Ethiopic Christian codices and scrolls. These materials were sold to Enriqueta Rylands in 1901, to form one of the cornerstone collections of the John Rylands Library in Manchester, where they remain.Footnote3

Figure 1. Photographic portrait of Lord Lindsay and his son Ludovic, by Camille Silvy, albumen print, 17 February 1863. Copyright National Portrait Gallery, London.

The earls’ engagement with orientalism spanned three-quarters of a century, from Lindsay’s precocious command of Persian as a schoolboy at Eton in the 1820s to the turn of the century when Ludovic was acquiring papyri from Egypt and ‘exotic’ materials from South-East Asia. This was the era when the British Empire was reaching maturation, with thickening military, administrative, commercial and cultural networks across the globe.Footnote4 It was also a period when scholarly engagement with the East developed from ‘lonely orientalists’, few in number, ‘undisciplined’, and with limited access to oriental manuscripts and museum objects, through several decades of professionalisation and complexification, to the end of the century when the discipline was becoming highly wissenschaftlich, with specialist research institutes, university chairs, and large state-run museums, libraries and archives.Footnote5 These trends, while slower to emerge in Britain than in mainland Europe, were to a significant extent inscribed in the development of the Bibliotheca Lindesiana.

The questions that I address in this paper include: What motivated Lindsay and Ludovic to collect oriental materials, when most nineteenth-century library builders confined their activities to Western manuscripts and printed books? How did the oriental collections support Lindsay’s own researches into racial classification, ethnology and comparative religion? How did Lindsay and Ludovic assemble these collections, and were there any differences between their respective practices? How did the earls of Crawford compare with other collectors of oriental books and manuscripts in terms of their backgrounds, interests, motives and mechanisms of collecting? And how did they engage with and contribute to wider orientalist discourses in their acquisition of material, in their endeavours to exert intellectual control over such heterogeneous collections, and in opening them up to researchers?

I shall examine the development of the library’s oriental collections and the earls’ engagement with orientalist discourses, through the lens of postcolonial studies, deploying several analytical tools, including Benedict Anderson’s ‘totalising classificatory grid’; Michel Foucault’s metonymic application – refined by Anne Brunon-Ernst – of Bentham’s Panopticon to a wide range of systems of discipline and control; Tony Ballantyne’s model of the British empire as a web rather than a centre and periphery; and investigations of the phenomenon of world’s fairs, or expositions universelles, by Paul Greenhalgh, Timothy Mitchell and John Ganim.Footnote6 Sadiah Qureshi offers a particularly nuanced reading of the racial aspects of such exhibitions: while ‘ethnic difference clearly played a critical role in the shows’ promotion and receptions’, he argues that ‘such associations were not inherent, self-evident, or uniformly adopted.’Footnote7

The primary evidence for this investigation lies in the collections of the Bibliotheca Lindesiana and in their archival traces: the extensive Crawford Library Papers, now housed at the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh, and in Lindsay’s monumental Library Report of 1861–65, the most detailed exposition by any nineteenth-century bibliophile of their collecting principles and ambitions.Footnote8

Motives for the Formation of the Oriental Collections

Lindsay’s explicit intention in (re)building the Bibliotheca Lindesiana was to create a universal, panoptical library which would serve the present and future needs of the Lindsay family:

I have always […] proceeded on the principle that a family library should be catholic in character – should include the best and most valuable books, landmarks of thought and progress, in all cultivated languages, Oriental as well as European. What one member of the family cannot, another may be able to read and appreciate. […] On this principle of literary catholicity you will be prepared, I think […] to recognise and acquiesce in the frequent occurrence in this Report of books in languages – as, for example, Arabic, Turkish, Armenian, Persian, Sanscrit, Chinese, Japanese, and others – very foreign to our European ears.Footnote9

While Lindsay professed that ‘I have never bent my thoughts’ in the direction of a manuscript library, he confronted the central importance of manuscripts in Middle Eastern and South Asian cultures.Footnote15 In order to document the faiths, literatures, arts and histories of these regions, it was therefore imperative to acquire a wide range of indigenous writings, as well as the secondary literature generated by Western orientalists.

Modern commentators have adduced a multitude of factors – linguistic, religious, cultural, political and technical – to explain the late adoption of print in the Middle East and South Asia.Footnote16 Space limitations preclude a detailed explication of the competing theories here, but the fortuitous implication for Lindsay was that he was collecting oriental manuscripts at a time when their indigenous cultural importance was diminishing; as they became displaced by print, they were more readily obtainable than in previous eras.

Allied to Lindsay’s utilitarian ambition of creating a universal, panoptical library, and the late adoption of printing in Middle Eastern and South Asian cultures, there was a further reason for his collecting manuscripts from these regions: to support his studies of comparative religion, ethnology and linguistics, which were grounded in his profound Christian (Anglican) faith. Nicolas Barker has succinctly summarised Lindsay’s aims:

To study the ancient literature of every nation, to understand the philological basis of their linguistic links, to know the other forms, in art and archaeology, in which ancient civilizations have been preserved, to recognize in all of them the grand design of God for all His peoples, underlies all his subsequent writing and speculation, and the formation of the Bibliotheca Lindesiana.Footnote17

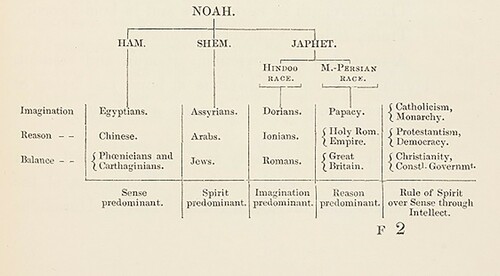

Lindsay synthesised earlier theological and philological approaches – in particular Japhetanism and Sir William Jones’s discovery of the unity of Indo-European languages – with a Hegelian dialectic and overt nationalism, to conclude that humanity had achieved its zenith in nineteenth-century Britain.Footnote19 He argues in Progression by Antagonism that ‘truth’ lies at the ‘point of intersection or compromise’ between imagination and reason, which ‘meet, in national combination and reconciliation, first and solely, however imperfectly, in the character and constitution, Ecclesiastical and Civil, of Great Britain’.Footnote20 Lindsay’s classification of civilisations was based upon the post-diluvian tripartite division of humanity deriving from the three sons of Noah (). He identifies the Egyptians, Chinese and Phoenicians – the least developed peoples – as the children of Ham, living in an era when ‘sense’ predominated; the Assyrians, Jews and Arabs as the sons of Shem, in which ‘spirit’ prevailed; and the superior ‘Hindu’ and ‘Medo-Persian’ (Aryan or Indo-European) races as the offspring of Japhet, amongst whom ‘imagination’ and ‘reason’ (the constituents of ‘intellect’) respectively dominated. It should be noted that this was not a scheme of Lindsay’s own devising but was grounded in a tradition that Colin Kidd traces back to Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies in the seventh century, in which Europe was associated with the stock of Japhet.Footnote21

Figure 2. ‘Descendants of Noah and the Progress of Intellectual Development’, from Lord Lindsay’s Progression by Antagonism (London: John Murray, 1846), p. 55. Copyright The University of Manchester.

To what extent were Lindsay’s views on ethnology and comparative religion supported by, or even dependent upon, his manuscript collections? Did the former determine or inform his collecting of oriental materials? Certainly, the bulk of the oriental manuscripts was acquired after the publication of Progression by Antagonism in 1846, and so cannot have influenced its formulation. In the Library Report, Lindsay listed some thirty oriental manuscripts, chosen to exemplify the extraordinary range of formats, materials, scripts and forms of decoration employed in written texts across many civilisations, but these ‘bibliographical curiosities’ were assigned to the extempore ‘Museum’ department of the library and were deemed to have little research value. On the other hand, by 1865 he had already amassed major collections of Chinese and Japanese books, and in the following decade he would go on to assemble large collections of Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Hebrew, Samaritan, Coptic, Ethiopic and South Asian manuscripts. These were certainly acquired for their research potential, rather than as mere ‘wonders’, and it is perhaps significant that the manuscript collections embraced all three branches of humanity, as Lindsay conceived them. He continued to develop his theories of Japhetan superiority throughout his life, culminating in the posthumously published Creed of Japhet, an attempt to delineate the Ur-religion of the Aryan race, for which he drew extensively upon the philological researches of Max Müller, John Muir and Martin Haug on the Rigveda and the Avesta, copies of which were to be found in the library.Footnote22

However, Lindsay’s limited linguistic skills (other than his early mastery of Persian when he was at Eton) were a practical impediment to his close study of the non-Western collections. Thus the collections furnished him with broad impressions, rather than detailed, empirical evidence. They corroborated his views on the relative progress of various civilisations, and reinforced his liberal appreciation of their manifold contributions to human development, but it cannot be claimed that his theories were built upon any evidence they provided. Lindsay may have hoped one day to interrogate his oriental collections, but he was primarily collecting on behalf of future generations of his family, and to benefit the wider world of scholarship.

Indeed, it would be a gross distortion to argue that Lindsay collected oriental materials merely, or even primarily, to corroborate his theories of racial superiority. One of the most striking aspects of the Library Report is the space and attention Lindsay accords to non-European cultures. He makes a series of generalised claims for the importance of non-Western civilisations, which are remarkably enlightened for the mid-nineteenth century:

It is not, in fact, Europe but Asia which should take bibliographical and literary precedence in the present department of the class of History. The great Universal Histories of the East are of higher importance than any of the preceding, as being written in many cases by men of science, observation, and experience, philosophers and statesmen, the Tacituses, Macchiavellis, and Montesquieus of their time and clime. […]

I cannot and I will not apologize for these various works of history or topography of which I have enumerated so many, whether as in our possession or as desiderata – the sources and springs of Oriental story. […] it will be seen that, apart from and independently of the great line of thinkers and actors familiar to Europe, and whom we commonly consider as the exclusive agents of the Almighty in promoting that progressive development, a thousand tributary rills of influence have poured in from unsuspected sources to swell and affect the main ^general^ current of human destiny. It is as the keys to these sources – of a remoter and yet nearer and more universal Nile – that I seek for these obscure and uncouth-sounding volumes of Oriental history, which at the first sight and aspect appear so uninteresting and uninviting.Footnote23

Lindsay even exhorts his countrymen ‘not to despise either Hindoo or Chinese […] but to recognize in him a kinsman in thought as well as in blood, and one too of an elder stock, still deserving of reverence’.Footnote24 For the post-Indian Rebellion 1860s this was an astonishing assertion – one hears echoes of Montesquieu, Voltaire and Goethe.

In summary, Lindsay was motivated to collect orientalia by his ambition to create a panoptical library, embracing all the world’s major civilisations, which would furnish data for his and others’ researches into ethnology, comparative religion, linguistics and other disciplines. While Lindsay claimed not to collect manuscripts per se, the central importance of the manuscript tradition in Middle Eastern and South Asian cultures obliged him to amass such material in order adequately to represent their achievements.

Ludovic did not share his father’s expansive interests in comparative religion, ethnology, and the diverse cultures of the East. He may also have come to the realisation that Lindsay’s dream of a universal library was neither attainable nor necessary, given the rise of institutional libraries in the late nineteenth century. Krzysztof Pomian argues that the development of public museums (and, by implication, libraries) relieved the private collection of its cognitive functions, liberating it to become, ‘sans réserve’, an expression of the collector’s personality.Footnote25 While Pomian exaggerates the public‒private dichotomy, the Bibliotheca Lindesiana instantiates a decisive shift towards subjectivity and selectivity in private collections.

Thus Ludovic abandoned his father’s ambition of creating a panoptical library, concentrating his collecting instead on particular types of material, such as illuminated Western manuscripts and jewelled bindings, incunabula, scientific books, proclamations and broadsides, French Revolutionary documents, philatelic material, exotic manuscripts from South-East Asia, and Egyptian papyri. It is difficult to perceive any coherence or philosophical structure to this bricolage, and he moved rapidly from one field of collecting to another. Enthusiasm rather than scholarship seems to have been his primary motivation. He was particularly drawn to decorated manuscripts and exemplary, rather than representative, items. His librarian reported: ‘Lord Crawford told me he did not care to increase the number of ordinary Oriental MSS.; his desire being rather to secure any, such as the Kufic Koran, of extraordinary interest, either for antiquity or beauty of workmanship.’ Ludovic appears to have treated such items as bibelots – curiosities – rather than research tools.Footnote26 His interests in Egyptian papyri and in South-East Asian manuscripts were kindled by his own visits to those regions, and thus these oriental manuscripts functioned as Susan Stewart’s ‘souvenirs of the exotic’: ‘on the one hand, the object must be marked as exterior and foreign, on the other it must be marked as arising directly out of an immediate experience of its possessor.’Footnote27

There is in fact some evidence that interest in oriental manuscripts waned amongst private collectors in Britain during the second half of the nineteenth century. The number of auctions featuring oriental manuscripts appears to have declined in this period, while in 1866 the bookseller Bernard Quaritch complained that,

there is very little demand for Oriental MSS. Dr. [John] Nicholson of Penrith Cumberland is one of my few remaining Oriental scholars, living in England. On the Continent and in the East, however, I have many customers of Oriental MSS.Footnote28

Mechanisms for the Development of the Oriental Collections

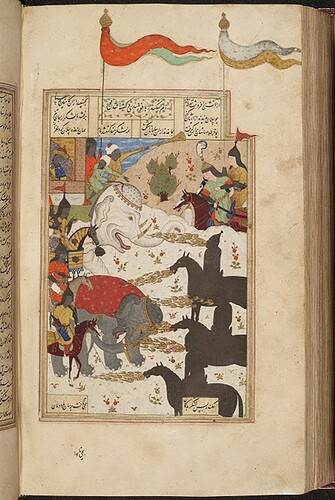

Lindsay accumulated the printed collections and Western manuscripts largely through the purchase of single items, from booksellers and at auction, or occasionally by gift or exchange with fellow collectors. Some oriental manuscripts were acquired in similar fashion, from a magnificent Shahnameh bought from the bookseller Joseph Lilly in 1855, to a manuscript of the Legends of Damar Wulan, illustrated with two hundred images derived from the Javanese shadow-puppet tradition, for which he paid Bernard Quaritch (his dealer of choice) £40 in 1877.Footnote30 However, these were generally the more important items, which were accorded connoisseurial and commercial status similar to that of Western manuscripts. The bulk of oriental material was acquired by other means.

In contrast to his normal practice of drawing up long lists of printed desiderata and employing agents to seek out the works he wished to obtain, Lindsay purchased entire collections of Middle Eastern manuscripts. As his son later remarked: ‘The principle here adopted was undoubtedly a good one – […] each private collection bought entire represents, as it were, and concentrates into the moment of such sale and purchase, a lifetime of watchful success and accumulation.’Footnote31 This was a pragmatic solution to the practical difficulties of obtaining material from the East. Moreover, since Lindsay lacked sufficient expertise to assess the collections himself, he relied heavily upon the reputations of the collectors from whom he purchased in order to validate and valorise the material.

From the early 1860s onwards, Lindsay purchased a series of major collections that propelled the Bibliotheca Lindesiana into the forefront of orientalist libraries. One of the first collections he acquired was that of the Belgian savant Pierre Léopold van Alstein (1792‒1862), which was sold at Ghent in 1863. Quaritch attended the auction and succeeded in securing the entire collection of oriental manuscripts for 3,000 francs (£120), colluding with the directeur de la vente to outwit the hapless librarian of the Bibliothèque Royale in Brussels, who had received a grant to buy the collection.Footnote32 It was significant as the first collection of Japanese books to reach Britain, reflecting Lindsay’s innovative tastes in book collecting, but it also contained important Chinese works.Footnote33 An auction of books from the collection of the French orientalist Jean-Pierre Guillaume Pauthier (1801‒73), in June 1870, afforded an opportunity to augment the Chinese department; Lindsay secured four lots of Chinese books, a set of eighty-six Chinese drawings and a Tamil manuscript, Valliy-ammai-purāṇam, for a total outlay of only £22.Footnote34 A further sale took place in Paris after Pauthier’s death, in December 1873, at which Lindsay secured twelve lots of Chinese books at a cost of £118 10s.Footnote35

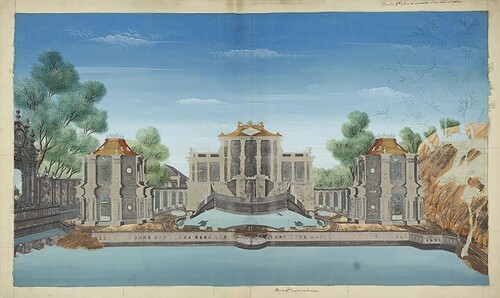

Lindsay took advantage of the opening up of China to purchase material through agents in Beijing and Shanghai, such as Rev. Joseph Edkins and Rev. Alexander Wylie.Footnote36 This reliance on missionaries reveals the contingent and ambivalent nature of the trade in Chinese books and manuscripts in the aftermath of the Second Opium War and the Taiping Rebellion. Although the Treaty of Tientsin of 1858 and the Peking Convention of 1860 had compelled the Chinese government to permit Western traders and missionaries to travel unhindered throughout China, in practice movement beyond the toehold treaty ports was still fraught with difficulty and danger. Peripatetic missionaries were amongst the few Westerners with sufficient knowledge of the indigenous language and culture and with suitable Chinese contacts to enable them to acquire books in parallel with their proselytising activities; they infiltrated Christian texts into China and exported Chinese books to Europe.Footnote37 Thus within a decade Lindsay succeeded in building one of the largest and most important collections of Chinese books and manuscripts in Britain (); it comfortably exceeded the 299 titles recorded in Edkins’s Citation1876 catalogue of Chinese works in the Bodleian Library.Footnote38

Figure 3. Unique hand-coloured plate from ‘Twenty Views of the European Palaces in the Garden of Perfect Brightness’, a set of 20 prints commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor in the 1760s. This set was purchased by Lord Lindsay from Bernard Quaritch in 1863. Chinese 457, plate 2a. Copyright The University of Manchester.

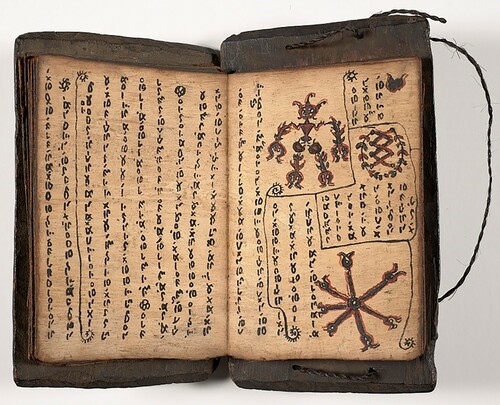

Ludovic discontinued his father’s practice of purchasing entire collections, adopting different strategies to augment the oriental collections. He developed a particular interest in the literatures of South-East Asia, stimulated by a cruise to the Far East in the winter of 1897. Although his enquiries after manuscripts in the region were fruitless, on his return to Europe he purchased a considerable number through the agency of Cornelis Marinus Pleyte (1863‒1917), a director of the Leiden-based publishers E. J. Brill and the author of several works on the languages and cultures of South-East Asia.Footnote39 Pleyte managed to obtain manuscripts in numerous languages – Achinese, Balinese, Batak, Buginese, Burmese, Javanese, Kawi, Madurese, Makasarese and Malay – procuring them both via missionaries and colonial administrators, and first-hand during his own visit to the region in 1899. Again one observes the collector’s reliance on trusted field-workers such as missionaries and government officials. While Lindsay had sought a few examples of South-East Asian manuscripts to populate his universal library of world literatures, Ludovic’s motives are harder to penetrate. As noted earlier, the exoticism of the material seems to have held appeal, and the broad range of media on which the manuscripts were written is noteworthy: palm leaf, bamboo, bone, bark and copper sheet. He instructed his librarian: ‘Get all the Batak he [Pleyte] will let you have especially the Bamboo ones.’Footnote40

Contextualising the Earls of Crawford in Relation to Other Collectors of Oriental Manuscripts

The earls of Crawford were not unique or even unusual in acquiring oriental manuscripts: pervasive orientalism ensured that many private libraries incorporated such material during the nineteenth century, in Britain and elsewhere in Europe. In order to assess more fully the earls’ significance as collectors and to distinguish any atypical or unique features of their collecting – in terms of motives, methods, scale and focus – it is imperative to contextualise them in relation to other collectors.Footnote41

Most collectors of oriental manuscripts in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries fall into three broad categories. The first comprised ‘field’ orientalists – officers of the East India Company (EIC), its European rivals and their respective armies, and those who followed in their wake, such as missionaries and traders – who acquired manuscripts in the colonial ‘contact zone’, as war booty, or through the more-or-less legitimate acquisition of indigenous libraries and single manuscripts; these men were in Bayly’s ‘vanguard of the imperial information collectors’.Footnote42 Secondly, there was an expanding cohort of metropolitan orientalists – independent scholars and, increasingly, those holding positions within the academy – who acquired manuscripts to support their research. The third group consisted of elite collectors who obtained specimen manuscripts to exemplify the highest standards of Eastern art and calligraphy, and to stand as comparators with their illuminated manuscripts from medieval and Renaissance Europe.

Of course, there were notable exceptions to this tripartite classification: William Beckford (1760‒1844) and William Bragge (1823–84), for example, defy easy categorisation. Beckford, ‘lone wolf among collectors’, embodies the syncretism of medievalism and orientalism, those mutually reinforcing ‘othernesses’, which flourished during the era of Romanticism.Footnote43 Ganim has explored this linkage, pointing out that geographic and temporal alterities are to some extent interchangeable: the past is indeed another country.Footnote44 Thus as well as medieval, Renaissance and modern European paintings, furniture and objets d’art, Greek and Roman antiquities, and an impressive library of printed books and European manuscripts, Beckford assembled a significant collection of oriental manuscripts, while Lucian Harris claims that his albums of Indian miniatures probably constituted the largest private collection of such material in Britain in the early nineteenth century.Footnote45

Our first group, ‘company’ orientalists, was responsible for acquiring tens of thousands of manuscripts during Britain’s long history of engagement in South Asia. Notable collectors included: Rev. George Lewis (c.1663–1729), chaplain at Fort St George, Madras, who donated a collection of over seventy manuscripts to Cambridge University Library;Footnote46 the Swiss scholar-mercenary Antoine Polier (1741‒95), who fashioned a collection of over six hundred manuscripts under the ‘double persona’ of a gentleman-orientalist and Mughal nobleman;Footnote47 Edward Ephraim Pote (1741‒1832), an EIC officer who purchased the majority of Polier’s collection;Footnote48 Sir William Jones (1746‒94), who bequeathed two hundred Sanskrit, Persian, and Arabic manuscripts to the Royal Society;Footnote49 Charles Wilkins (d. 1836), translator of the Bhagavadgītā;Footnote50 Colin Mackenzie (1753‒1821), who acquired 1,568 ‘literary’ manuscripts while serving as Surveyor-General of Mysore and later Madras;Footnote51 Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1765‒1837), Professor of Sanskrit and Hindu Law at Fort William College in Calcutta;Footnote52 the Persian scholar Sir William Ouseley (1767‒1842);Footnote53 his brother, Sir Gore Ouseley (1770‒1844), who amassed a magnificent library of manuscripts during his mission to Tehran in 1810‒14;Footnote54 Claudius James Rich (1786/7‒1821), the EIC’s resident in Baghdad, whose collection of over eight hundred Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Chaldean and Syriac manuscripts was purchased by the British Museum in 1825;Footnote55 and Sir Henry Miers Elliot (1808‒53), who collected over 450 Persian, Arabic and Hindustani manuscripts during his service with the EIC in India.Footnote56

Such collections exemplify the hybridity of the EIC itself, that curious amalgam of private enterprise and agency of British imperialism in the East. The collections both mirrored the individualised experiences, tastes and interests of the officers who assembled them – exhibiting the qualities of souvenirs or trophies – and simultaneously manifested and were authorised by the policies and practices of the EIC and of the British Government, in seeking to outmanoeuvre their European rivals and subjugate indigenes in the name of trade and empire.Footnote57 The collections were heavily implicated in imperialism, which was itself a form of collecting on the national scale, as Elsner and Cardinal have explicated.Footnote58 Many ended up in the possession of the EIC and other institutions, underscoring their equivocal public-private status; the presence of indigenous manuscripts within institutional collections at the heart of empire continually reaffirmed – indeed re-enacted – British conquests (military, political and cultural). Manuscripts thus functioned as instruments of colonial intelligence gathering and control; they constituted an additional component of Anderson’s ‘totalising classificatory grid’, alongside the census, the map and the museum, which ‘illuminate the late colonial state’s style of thinking about its domain’.Footnote59

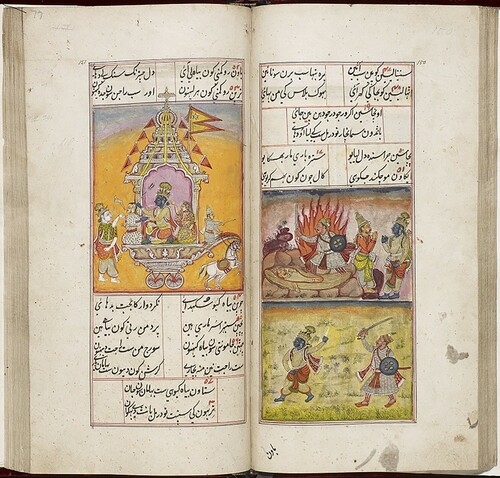

One of Edward Said’s tenets is the implication of academic interest in the East with colonialism, or muscular orientalism.Footnote60 Certainly it is impossible to draw clear distinctions between ‘Company’ orientalists and their counterparts in the academy, in terms of the personnel involved, their networks, their competences, or their motives for engaging with the East. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, many experts in Sanskrit, Arabic and Persian languages and literatures were Company men, whose duties demanded at least some linguistic abilities in order to communicate with the people over whom they ruled. One such was Turner Macan (1792‒1836), chief Persian interpreter to the Commander-in-Chief of India, who assembled an important collection of books and manuscripts; these included a copy of the Shahnameh said to have belonged to the Kings of Oudh, which formed the basis for Macan’s published edition, and was purchased by Lindsay in 1854 ().Footnote61 Even orientalists firmly situated within British universities engaged with colonialism, such as Edward Granville Browne (1862‒1926), Professor of Arabic at Cambridge, who trained officers of the Egyptian and Sudanese civil service and the diplomatic service in the Levant. His working collection of almost five hundred Persian, Arabic and Turkish manuscripts was bequeathed to Cambridge University Library.Footnote62

Figure 4. The Bhāgavata-Purāṇa is one of the most sacred texts for followers of Krṣṇa. This eighteenth-century copy of a Hindustani translation is decorated with 146 miniatures. It was owned by Rebekah Bliss (1749–1819) and Nathaniel Bland (1803–65) before being acquired by Lord Lindsay. Hindustani MS 2, fols 76b–77a. Copyright The University of Manchester.

During the nineteenth century there arose a cohort of collectors like Lindsay, whose interest in oriental manuscripts was neither inspired by first-hand experiences of the East, nor motivated by the imperatives of their official positions as functionaries of the EIC or the British Government. In 1866 Lindsay purchased the manuscripts of two stay-at-home orientalists, Nathaniel Bland (1803‒65) and Duncan Forbes (1798‒1868). Bland was a gentleman-scholar of Persian literature, who served on the council of the Royal Asiatic Society and published several articles in the Society’s Journal.Footnote63 Bland appears to have begun collecting manuscripts in the 1820s, buying extensively from the booksellers John Cochrane, Howell & Stewart, and William Straker, who all specialised in oriental books and manuscripts. He also made substantial purchases at the sales of the earl of Guilford (1835), Turner Macan (1838), Rebekah Bliss (1842), and Silvestre de Sacy (1842).Footnote64 By 1838 he had expended over £600 on manuscripts ().Footnote65 Quaritch described him in 1866 as ‘a first class Arabic and Persian scholar, who bought MSS. 20 and 30 years ago almost at any price, he was then very rich.’ Unfortunately Bland lost his entire fortune to gambling and shot himself at Bad Homburg in August 1865. The following June Quaritch sold his manuscript collection to Lindsay in two instalments of £450 and £400.Footnote66

Figure 5. This copy of the Shahnameh, dated 949AH/1542AD, is said to have belonged to the Kings of Oudh. It formed the basis of Turner Macan’s 1829 edition and later belonged to Edward Craven Hawtrey, Provost of Eton. It was purchased by Lindsay in 1854. Persian MS 932, fol. 381b. Copyright The University of Manchester.

Like Browne, Bland’s friend Duncan Forbes epitomises the gradual academicisation of orientalism in England during the nineteenth century. After a residency at the Calcutta Academy in 1823‒26, curtailed by ill health, he spent the remainder of his career in London; from 1837 he held the chair of oriental languages at King’s College, despite a lacklustre scholarly reputation. Lindsay purchased fifty-six Forbes manuscripts from William H. Allen & Co., publishers to the India Office, paying a total of £362 2s.Footnote67 Quaritch remarked: ‘In former years Dr. Forbes used to scoure [sic] the London market, but he would rarely buy anything but low priced articles.’Footnote68 This was a scholar’s working library, enlivened by a few choice literary texts, rather than a connoisseur’s collection.

From ‘field’ and scholarly orientalists, I turn to the third group of collectors. It was not unusual for elite manuscript collectors and bibliophiles to possess a handful of exemplary oriental items, alongside their Western illuminated codices and printed books, which provided a veneer of oriental exoticism. They especially favoured richly decorated Persian and Sanskrit manuscripts and calligraphic Qur’āns, which were selected according to similar aesthetic criteria as illuminated Western codices, reinforcing the perennial association of the East with luxuriance and excess. Like exotic flowers uprooted by plant-hunters and classified along ‘scientific’ principles, the manuscripts’ specific cultural and religious contexts were elided in a process of assimilation into European artistic and literary canons, while they simultaneously retained a generalised ‘otherness’, and were often appended to, rather than fully integrated with, collections. Homi Bhabha’s famous conceit, ‘Almost the same, but not white’, originally applied to colonial mimicry, is equally pertinent to the ambivalence of oriental manuscripts when transposed to the connoisseurial context of elite libraries.Footnote69 Thus Henry Huth (1815‒78) owned fine copies of the Bhagavadgītā and Shahnameh, an Ethiopic Prayerbook, and an Armenian Evangelia.Footnote70 The collection of two hundred manuscripts, which Frank McClean (1837‒1904) bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, included ten Arabic and Persian manuscripts and single examples of Ethiopic, Armenian and Pali.Footnote71 Similarly, the seventy-one manuscripts recorded in the library of William Tyssen-Amherst (1835‒1909) were overwhelmingly European; the nine oriental manuscripts – a complete Qur’ān and portions of three others, two Persian codices including a collection of Ferdowsi’s poetry, and three Arabic manuscripts – were relegated to the final section of the catalogue.Footnote72

Geographically proximate to the earls of Crawford but separated from them in time and class was the Blackburn industrialist Robert Edward Hart (1878–1946). He utilised the wealth derived from his family’s rope-making business quietly to accumulate twenty-one Islamic and Jewish manuscripts (one-third of which were illuminated Persian works), alongside a larger number of medieval Christian manuscripts and an exceptionally fine printed collection spanning from fifteenth-century block-books to the Kelmscott Chaucer. Hart’s motives for collecting orientalia are opaque in the absence of any clear statement of intent, but he appears to have been interested in diverse material formats and communication technologies, such as cuneiform tablets and palm-leaf manuscripts, and at least some of the items appear to have functioned as souvenirs of his extensive travels and of his firm’s international trade networks. Cynthia Johnston convincingly argues that his collecting in general and his subsequent philanthropic gifts to Blackburn Museum both epitomised and affirmed a ‘highly developed regionalism’ and local civic pride. These were motivations very different from those impelling the earls of Crawford.Footnote73

At the apex of collecting, the cabinet of Baron Edmond de Rothschild (1845‒1934) epitomised the taste for superlative examples of the art of illumination within the Judaeo-Christian traditions; the few oriental manuscripts he possessed, including the incomparable Shah Tahmasp or ‘Houghton’ Shahnameh, half of the famous Akbar-Nameh, and three albums of Indian and Persian miniatures, conformed to the dominant aesthetic of Western connoisseurship.Footnote74

The Sheffield industrialist William Bragge serves as an interesting comparator to Lindsay and Ludovic.Footnote75 While susceptible to the allure of illuminated medieval manuscripts, Bragge also acquired a wide range of material from across the world, with some thirty languages represented in his collection. In addition to manuscripts in Arabic, Persian and the other principal languages of the Middle East and South Asia, Bragge owned material on palm-leaf and bamboo from South-East Asia; Mexican, Ethiopic and Tibetan manuscripts; and volumes of Chinese and Japanese drawings. There is insufficient evidence to reconstruct Bragge’s motives in assembling such materials, but the collection reflected Bragge’s own cosmopolitan life, the growth of industrial and commercial networks across continents, and the globalisation of the manuscript market in this period. When the manuscripts were sold in 1876, one-quarter of the five hundred or so lots comprised oriental material.Footnote76

The Bragge collection closely parallels the manuscript portion of the Bibliotheca Lindesiana in the broad range of cultures, languages and writing formats represented, albeit on a much smaller scale. Like Lindsay, Bragge was a major patron of Quaritch, who discerned similarities between his two customers.Footnote77 However, the correspondences should not be overplayed; as I noted above, Bragge’s motives for collecting oriental manuscripts are difficult to penetrate, but he may be characterised as a serial collector: alongside manuscripts he collected editions of Cervantes, pipes and smoking paraphernalia, books on tobacco, and precious gems. He appears to have collected oriental manuscripts as curiosities, in the Wunderkammer tradition, or as personal souvenirs, more akin to Ludovic’s interest in exotic material purely for its eclecticism, in contrast to Lindsay’s more rigorous intellectual approach. We cannot surmise the depths of Bragge’s intellectual and aesthetic engagement with his oriental collections, but there is no evidence that his manuscripts were catalogued before their sale in 1876, and they were rarely consulted by scholars.Footnote78

Thus the earls of Crawford were quite unlike other nineteenth-century collectors of oriental manuscripts, both in the scale of their acquisitions, and in the broad geographic and cultural horizons of their collecting. They differentiated themselves from elite or ‘cabinet’ collectors by not restricting their orientalia to a small number of superlative specimens. Nor did they confine their collecting to material from a particular region or culture, whereas most academic and ‘Company’ orientalists tended to acquire manuscripts from the countries where they were stationed or where their academic interests lay. And notwithstanding the analogies between Bragge and the earls of Crawford – in terms of the mechanisms by which they assembled their collections and the range of material represented in them – they were separated not merely by social class but also by the scale and (certainly in Lindsay’s case) the intellectual underpinnings of the Bibliotheca Lindesiana. The earls of Crawford were indeed exceptional in the scope and ambition of their collecting of oriental manuscripts.

The Earls' Engagement with Orientalist Discourses

The earls of Crawford engaged with orientalist discourses in a variety of contexts: through the mechanisms by which they acquired manuscripts; via their interactions with scholars and experts in the ongoing project to impose intellectual control over the collections; and in their endeavours to make the oriental material available to researchers. It is essential to explore these modes of engagement in greater detail, before I consider whether and to what extent the oriental collections of the Bibliotheca Lindesiana themselves contributed to and advanced wider orientalist discourses.

Many British collections of oriental manuscripts were directly implicated in militant imperialism, as I have already observed. For example, after the fall of Seringapatam several thousand volumes were transferred from Tipu Sultan’s library to Fort William College, where they were catalogued by Charles Stewart; some were later transferred to England and ultimately resided in the British Museum and the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, thus corroborating the mutually reinforcing associations between academic orientalism and active imperialism.Footnote79 In the preface to his catalogue Stewart recorded that very few of the books had been purchased by Tipu Sultan or his father: instead they had been plundered from the libraries of other Indian states.Footnote80 No doubt this helped assuage British consciences, but it also warns against simplistic, reductive readings of manuscript collecting as the unequivocal manifestation of a brutal imperialism imposed upon innocent indigenes. Rather, one should acknowledge the nuanced, contingent positions of both rulers and ruled within imperialism.Footnote81 It must also be remembered that spoliation was a characteristic of European wars too: colonial forces simply exported practices honed on native soil.Footnote82

Although Lindsay was not directly engaged in imperialism (unlike his grandfather, Alexander Lindsay, who as governor of Jamaica in the 1790s had viciously suppressed a Maroon rebellion, or his great uncle Robert, who grew rich from private trading ventures while serving with the EIC), his collecting practices certainly benefited indirectly from aggressive colonialism. In the Library Report he openly declares that he sought to form the Bibliotheca Lindesiana by ‘bringing the spoils of many a distant land, through the compulsion of peace, towards its subsequent edification’.Footnote83 While the oxymoronic ‘compulsion of peace’ encapsulates the contradictions at the heart of imperialism, Lindsay states explicitly that the development of the library was predicated upon the simultaneous expansion of Britain’s empire, and it is certainly the case that a large number of his manuscripts derived, directly or indirectly, from military exploits around the world. In 1862, for example, Quaritch informed Lindsay that he had recently acquired an exceptional copy of the Sri Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred book of Sikhism, said to have been ‘wrested out of the hands of a Sikh Priest at the battle of Guzerat by an Officer of the 52nd Bengal Native Infantry’. Overlooking such doubtful provenance, Lindsay told Quaritch that he would ‘be glad to keep the Sikh MS, which is of great curiosity & value’.Footnote84

In 1868 Lindsay acquired two collections of manuscripts that were closely associated with recent colonial campaigns. In July he paid £400 for 717 Arabic, Persian and Turkish manuscripts and sixty-four printed books offered by the executors of Colonel George William Hamilton (1807‒68), who had served with the EIC as a regimental interpreter in central and northern India. Hamilton exemplified the Company soldier-scholar: he ‘always paid great attention to the native languages, not merely the vernaculars, but also to the Arabic and Persian, and gradually collected a good oriental library’, while during the 1857 Rebellion, ‘he marvellously held his ground and kept the soldiery from breaking out into violence.’Footnote85 Both Quaritch and Charles Rieu of the British Museum advised that Hamilton’s manuscripts had been looted, the former claiming that

although the MSS. as a general rule are not of any antiquity, they were for the most part transcribed for the Kings & Nabobs of Oude, being in fact plunder from the libraries of Lucknow – which is some warrant for their correctness.

While Lindsay was negotiating the purchase of the Hamilton manuscripts – fruits of imperialism in India – Quaritch was securing for him a collection of Ethiopic manuscripts, booty from the Anglo-Indian expedition to Abyssinia. Less than three months after the sacking of Magdala in April 1868, the bookseller dashed off a letter to Lindsay informing him that he had just bought a ‘very curious’ collection of seven Ethiopic manuscripts from the infamous Magdala hoard, of which some 350 manuscripts were presented to the British Museum:

Though it was stated that all the Manuscripts looted at Magdala had been given up to Mr [Richard] Holmes for the British Museum, it appears that Mr [Hormuzd] Rassam contrived to have some private loot or private purchase at one of the Churches at Magdala, which acquisition, he not being a soldier, was not surrendered. Captain [Howard] Coghlan […] bought these MSS. from Mr Rassam at Magdala and brought them to London. Captain Coghlan landed only yesterday, to-day they were offered to me for £150, but I bought them at a price to be able to sell them to your Lordship at £100.Footnote87

cannot but lament, with Mr Quaritch, that the fate of war should thus deprive the poor people of what is not only their scanty literature but the material means of carrying on their religious worship. Still Magdala and its neighbourhood is but a fragment so to speak of Abyssinia.Footnote88

In the cases of both the Hamilton library and the Ethiopic manuscripts, it is significant that the British Museum had already obtained material from the same sources. The Museum’s official acquisition procedures not only validated the importance of the manuscripts, but also legitimated them and normalised the doubtful circumstances through which they were obtained, thereby justifying and sublimating the collector’s private purchases. The Museum was not only a beneficiary of empire; it was instrumental in authorising and advancing imperialism, as Thomas Richards cogently argues:

In a very general way the capillaries of an institution like the British Museum traversed the British Empire, and as a political institution the museum tended to intervene forcefully in the Empire (where cultural treasures often needed to be taken by force).Footnote90

Such examples of indigenous ‘talking back’ are reminders that local agency was a significant – if largely occluded – factor in the formation of orientalist libraries. Only rarely did the earls of Crawford deal directly with indigenes; for example, when Ludovic purchased papyri from dealers in Cairo.Footnote93 Nevertheless, many of their suppliers (fellow collectors, booksellers and agents ‘in the field’) did treat with local informants, owners and vendors who, except in the extreme case of plunder, were to varying degrees able to influence the quality, quantity and prices of manuscripts that came onto the market. Collectors such as Ludovic complained both that the best material was withheld from them and that they were obliged to pay excessive amounts for second-rate manuscripts. Thus subaltern voices insinuated themselves into elite collections such as the Bibliotheca Lindesiana.Footnote94

Even when the earls of Crawford were not directly implicated in aggressive imperialism, they benefited from the traffic of oriental manuscripts that developed in the wake of colonial adventures. Ballantyne’s model of the British empire as a web is a more faithful representation of the shifting interdependences of colonialism than the traditional centre-and-periphery model, but London was undoubtedly the focus of international trade in manuscripts; they were a commodity of empire alongside staples such as tea, sugar and cotton.Footnote95 Quaritch functioned as an entrepôt for books and manuscripts arriving in Britain from all over the world although, as I noted earlier, other booksellers also dealt in orientalia, such as Charles John Stewart, from whom Lindsay purchased a collection of twenty-two Samaritan manuscripts for £450 in July 1872.Footnote96 Lindsay also acquired a large number of manuscripts on the Continent, where there was a longer tradition of collecting and studying such material, thanks to three hundred years of Dutch engagement in the East Indies and the concomitant expertise accumulated at the University of Leiden, whose pre-eminence in orientalist studies was eventually supplanted by Paris during the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote97 Thus the van Alstein, Pauthier and H.C. Millies sales all furnished Lindsay with significant numbers of important manuscripts ().

Figure 6. Pustaha, Batak magic book written on the inner bark of the alim tree. It was acquired by Lord Lindsay at the auction of the library of the Dutch Orientalist Hendrik Christiaan Millies (1810–68) in 1870. Batak MS 1. Copyright The University of Manchester.

The earls of Crawford engaged with orientalist discourses in other contexts. They collaborated with scholars and experts in their endeavours to impose intellectual control over the collections, and to make them more accessible to researchers and more widely known. The slow development of orientalist disciplines within British universities, in comparison with their continental counterparts, is apparent in the continual difficulties that Quaritch and the earls experienced in finding suitable experts in Britain to catalogue the collections; instead they regularly turned to European scholars for assistance.Footnote98 Thus in 1870 Quaritch confessed that he knew of no-one who could catalogue Siamese manuscripts, while twenty-two years later Reinhold Rost lamented that Edward Cowell in Cambridge was the only person in Britain competent to catalogue Zend and Sanskrit manuscripts. ‘But I doubt whether he would undertake this matter. In that event I would recommend Professor Geldner, of Berlin.’Footnote99

The scholars and experts who were employed to catalogue the oriental collections were an eclectic assortment. They included Sukias Baronian, Armenian minister in Manchester (Armenian); Sir Ernest Wallis Budge of the British Museum (Coptic); Frederick Cornwallis Conybeare of Oxford (Armenian); (Sir) Arthur Cowley of Oxford (Samaritan); Prof. Karl Friedrich Geldner of Berlin (Parsi); Abraham Löwy, minister at the West London Synagogue (Samaritan and Hebrew); Prof. George Karel Niemann of Delft (Batak); Léon Pagès of Paris (Japanese); Rev. John Medows Rodwell (Coptic); Dr Reinhold Rost of the India Office Library and St Augustine’s Missionary College, Canterbury (Punjabi); Prof. Albert Cornelis Vreede and Cornelis Marinus Pleyte of Leiden (South-East Asian manuscripts); Dr Edward William West, independent scholar (Parsi); and John Williams, Assistant Secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society (Chinese). The development of the papyrological collections brought other scholars within the ambit of the library: Walter Ewing Crum, Francis Llewellyn Griffith, Bernard Grenfell, Arthur Hunt, and Prof. Josef Karabaček in Vienna.

The diversity of these experts – some situated within the academy, others located within the cognate fields of museums and libraries, and yet others independent researchers and those whose cultural and linguistic backgrounds were their principal qualification – demonstrates the contingent, transitional status of orientalism in the second half of the nineteenth century: the exterior boundaries and internal structures of the discipline were as yet poorly delineated; there remained significant intersections with theological and classical studies; and distinctions between amateur and professional were faintly drawn.

There was a strong element of self-interest in these experts’ engagement with the library: they were eager to study and describe the largely unexplored Crawford manuscripts because of the opportunities they afforded to make significant discoveries. The earls of Crawford were munificent in permitting scholarly access to the collections, not only at Haigh Hall, but also by lending material out for sustained periods of study. For example, in September 1887 John Gwynn of Trinity College Dublin enquired through an intermediary if he might borrow a Syriac New Testament, which was already on loan to Rev. George H. Gwilliam in Oxford. Permission was duly granted. When Edmond enquired in December 1892 whether Gwynn had finished with the manuscript, the latter explained that he had returned it to Gwilliam over a year earlier. Gwynn also provided a full report on the volume, claiming that it was ‘the only complete Syriac MS. New Testament ever brought from the East into a European Library’. After further prompting, Gwilliam eventually returned the manuscript in September 1893, a full six years after the initial loan.Footnote100

The degree of academic engagement with the Bibliotheca Lindesiana is demonstrated by the adverse reaction to the sale of the manuscripts to Enriqueta Rylands in 1901. Far from welcoming their ultimate deposition in a public institution, scholars protested that their ready access to material had been abruptly curtailed. Edward Granville Browne was greatly inconvenienced by the recall of Persian MS 308, which he had been studying since 1898 for his edition of the Lubāb ul-Albāb. He told Edmond:

Lord Crawford has been so generous and yourself so kind in letting me have the MS. for so long that it would be most ungracious of me to complain of its recall, though I will admit that it is a disappointment, as I had been making it the pièce de résistance of my work.Footnote101

These MSS., we are glad to learn, have recently been made accessible, but until the wise and liberal policy of Lord Crawford is adopted, their transfer to the place mentioned must be regarded by Oriental students as a great calamity.Footnote103

These forms of engagement with academic orientalists were obviously circumscribed and specific, and there is no evidence that the earls of Crawford considered themselves members of an orientalist community, however loosely defined.Footnote104 Neither Lindsay nor Ludovic engaged with the formal structures of orientalism, which organised, disseminated and legitimated orientalist discourses: they were members of neither the Royal Asiatic Society nor the Royal Geographical Society, for example. They were peripheral figures in the development of academic orientalism in Britain. While they were generous in loaning material to scholars, the physical isolation of the collections in Wigan, remote from the principal loci of scholarship, and the lack of detailed catalogues inhibited their exploitation for research. When Ludovic’s son, Lord Balcarres, complained in 1898 that the library’s oriental department was little used, Edmond pointed out that he was sending a copy of the newly-published Hand-List of Oriental Manuscripts to Edward Browne in Cambridge, adding: ‘As the library gets better known the Oriental books will be more asked for.’Footnote105 However, this unsatisfactory situation persisted long after the transfer of the collections to Enriqueta Rylands: throughout the twentieth century they continue to be underutilised in comparison with analogous collections in the established centres of academic orientalism in Britain and mainland Europe.

Conclusion

The Crawford collection, while exceptional in size and richness, illuminates trends and issues which affected a wider cohort of collectors. Lindsay was motivated to collect oriental manuscripts by his desire to fashion a panoptical library, encompassing all the major civilisations of the post-Noachian diaspora, in order to facilitate his and others’ researches into ethnology, comparative religion, linguistics and numerous other fields. His attitudes towards issues of race, imperialism and the East are complex and ambivalent, mirroring wider trends and debates in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. He was prepared to deploy teleological arguments in support of British imperialism and overlooked acts of colonial violence by which manuscripts were wrested from their indigenous contexts. On the other hand, his possession of oriental materials evidenced – and may have encouraged – an unusually enlightened attitude towards non-European cultures and their achievements, akin to Sir William Jones’s earlier quest for a sympathetic understanding of Indian civilisations. Lindsay’s racial theories synthesised earlier monogenist and philological – broadly liberal – approaches with a Hegelian dialectic and blatant nationalism, to argue for the superiority of the Aryan races, which he believed had reached their apogee in Victorian Britain. Yet he did so with that ‘delicate manner […] wherewith anything can be said or done by a gentleman’.Footnote106 Unlike contemporary scientific racists, he acknowledged kinship, however distant, with ‘inferior’ races.

Lindsay’s interest in racial classification connected to his concern with social distinction and class, and in particular his advocacy for the continued relevance of the aristocracy; he believed that social distinctions within nations were intrinsically connected to wider racial classifications, while his aristocratic upbringing and sense of social obligation inculcated paternalistic benevolence towards other races. These overlapping concerns reflect wider associations between imperialism and the self-fashioning of Britain’s social elite, as Mark Girouard has argued:

[t]he sources of imperialism and the sources of the Victorian code of the gentleman are so intertwined that it is not surprising to find this code affecting the way in which the Empire was run. […] The philosophy of imperialism was essentially élitist.Footnote107

While Edward Said’s thesis has informed this discussion of the earls’ engagements with orientalism, subsequent postcolonial studies have helped to uncover a more complex, contingent position: a matrix of loosely related orientalist discourses, intersecting with the cognate disciplines of theology and classics, and enjoying a far from straightforward relationship with muscular imperialism. This more nuanced approach permits a fuller appreciation of the complex and sometimes contradictory relationships between the earls of Crawford and wider orientalist discourses. I have shown that although neither Lindsay nor his son were intricated in the official structures of orientalism, which became increasingly formalised and ramified towards the end of the century, they engaged with orientalism in various ways: through their acquisition of books and manuscripts, some of which were implicated in aggressive imperialism, while others had been accumulated by academic orientalists in Britain and Europe; via their employment of experts to catalogue the material; and by opening the collections to academic investigation.

Interest in oriental manuscripts was less prevalent than the contemporary collecting of Eastern applied arts. Indeed, I have argued that the number of private collections of oriental manuscripts declined during the nineteenth century, reflecting a hardening of attitudes both in Britain and in the colonial ‘contact zone’. Nevertheless, the collecting of these texts is significant for its close association with – and illumination of – wider trends in imperialist and racial discourses, and with indigenous resistances thereto. While the Bibliotheca Lindesiana functions as an apposite case study of a major collection of oriental manuscripts, a more thorough investigation of the wider phenomenon – one that situates manuscript collecting within the broader discourses around imperialism and the collecting of indigenous material cultures – is therefore long overdue.

Acknowledgements

This article originated in a chapter of my PhD thesis, ‘Class Acts: The Twenty-Fifth and Twenty-Sixth Earls of Crawford and their Manuscript Collections’ (University of Manchester, 2017). I am grateful to my supervisors, Professor Stephen Milner, Dr Guyda Armstrong and Professor David Matthews, for their unstinting support and sage guidance throughout the course of my studies, and to Professor Anindita Ghosh, who offered constructive comments on an early draft of the chapter. Cynthia Johnston of the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, and Stephanie Seville, Curator of Art at Blackburn Museum & Art Gallery, were generous of their time and expertise on R. E. Hart. This article has benefited significantly from the incisive suggestions of the journal’s anonymous reviewers. I am fully responsible for all remaining errors and deficiencies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 On the collecting of oriental antiquities and applied art, see, for example, Clunas, “Oriental Antiquities”; Jackson, “Persian Carpets”; MacKenzie, Orientalism; Roxburgh, “Au Bonheur des Amateurs”; Porter, Chinese Taste. Ghobrial, “Archive of Orientalism,” provides an excellent analysis of the collecting of oriental manuscripts in the early modern period. Pearson, Oriental Manuscript Collections, has not been entirely superseded as an overview of institutional manuscript collections.

2 On the Bibliotheca Lindesiana, see Barker, Bibliotheca Lindesiana; Barker, “Making of a Collector”; Brigstocke, “Lindsay, Alexander William”; Gingerich, “Lindsay, James Ludovic”; Hodgson, Class Acts; Ridley, “Lindsay, David Alexander Edward.” For an overview of the oriental manuscripts, see Taylor, “Oriental Manuscript Collections.”

3 There were also several thousand papyrus fragments. List of European and oriental manuscripts compiled by A.B. Railton of Sotheran’s, July 1901: University of Manchester Library (UML), Railton Papers, ABR/2/2. Lists of items received from Haigh Hall, 1901: UML, John Rylands Library Archive, JRL/6/1/6/1/5.

4 For an introduction to British imperialism, see Porter, Oxford History; Said, Orientalism; Said, Culture and Imperialism.

5 On disciplinarity in relation to orientalism, see Bayly, Empire and Information; Marchand, German Orientalism; Reid, Whose Pharaohs?, 93–136. The phrase ‘lonely orientalists’ is from Marchand, p. 102.

6 Anderson, Imagined Communities; Ballantyne, Orientalism and Race; Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 195–228; Brunon-Ernst, “Deconstructing Panopticism”; Greenhalgh, Ephemeral Vistas; Mitchell, Colonising Egypt; Ganim, Medievalism and Orientalism.

7 Qureshi, Peoples on Parade, 276.

8 I am grateful to the twenty-ninth earl of Crawford for permitting me to consult the Crawford Muniments, and to and photograph the Library Report.

9 Balcarres House, Colinsburgh, Fife, Crawford Muniments: Lord Lindsay’s Library Report, 1861‒65, Introduction, p. 16.

10 Letter from Lindsay to Anne Lindsay, 30 March 1843; CPP, 94/11, fols 1192‒3.

11 Pitt-Rivers argued that the object of an anthropological collection was to ‘trace out […] the sequence of ideas by which mankind has advanced from the condition of the lower animals to that in which we find him at the present time, and by this means to provide really reliable materials for a philosophy of progress.’ Pitt-Rivers, Evolution of Culture, 9–10.

12 Mitchell observes that ‘the panopticon […] was a colonial invention. The panoptic principle was devised on Europe’s colonial frontier with the Ottoman Empire, and examples of the panopticon were built for the most part not in northern Europe, but in places like colonial India.’ Mitchell, Colonising Egypt, 35. See also Brunon-Ernst, “Deconstructing Panopticism.” On panoramas, see Comment, The Panorama; Otto, “Between the Virtual.”

13 Bowler, Invention of Progress, 106–28; Burrow, Evolution and Society, 101–36; Ganim, Medievalism and Orientalism, 95–8.

14 Burrow, Evolution and Society, 80.

15 Letter from Lord Lindsay to Bernard Quaritch, [10 May 1860]; National Library of Scotland, Acc. 9769, Crawford Papers, Crawford Library Letters (hereafter CLL), Jan‒June 1860, fol. 185. Library Report, Epilogue, p. 7.

16 See, for example, Bayly, Empire and Information, 200, 38‒43; Mahdi, “From the Manuscript Age”; Mitchell, Colonising Egypt, 152; Nasr, “Oral Transmission”; Robinson, “Technology and Religious Change”; Wilson, Translating the Qu’ran. Bayly convincingly argues that indigenous information orders – the systems and structures for gathering and disseminating information and organising knowledge – were permeable and malleable, capable of adapting themselves and of exploiting new technologies that furthered the interests of those parties which possessed most economic, social and cultural capital within the order. Both religious and secular authorities, as well as dissenting voices, found that print enabled them to promulgate their views more effectively.

17 Barker, Bibliotheca Lindesiana, 89.

18 Stepan, Idea of Race, 45. Her thesis is supported by Hall, Civilising Subjects. On Victorian theories of progression, see also Burrow, Evolution and Society; Bowler, Invention of Progress. Monogenists adhered to the biblical account of a common source for the whole of humanity, while polygenists such as John Crawfurd (1783–1868) argued that the different races had separate origins and were in fact distinct species. Crawfurd, “Classification of the Races of Man.”

19 He claims that ‘it is from the collision of partial truths that Truth in the abstract, disencumbered from the alloy of earthly prejudice, soars aloft and darts onward to her goal.’ Lindsay, Progression by Antagonism, 12–13.

20 Ibid., 17, 67.

21 Kidd, British Identities, 27. Ganim notes that the tradition is found in England as far back as Ælfric of Eynsham (d. c.1010): Ganim, Medievalism and Orientalism, 78.

22 Lindsay records his reliance on published editions rather than the manuscripts. Lindsay, Creed of Japhet, xlvii. The work was published posthumously; his widow claimed that it was ‘looked upon by him as the great work of his life’ (p. xiii).

23 Library Report, History, pp. 15, 68.

24 Library Report, Historical Paralipomena, p. 19.

25 Pomian, “Collections: une typologie historique,” 18. Quoted in Bielecki, The Collector, 87. See also Pomian, Collectors and Curiosities, 258–75; Müller, “Amateur and the Public Sphere,” 433.

26 Letter from J.P. Edmond to Lord Balcarres, 15 February 1897; CLL, Jan‒Feb 1897, fol. 156. On bibelots, see Saisselin, Bricabracomania.

27 Stewart, On Longing, 147.

28 Letter from Quaritch to Lindsay, 28 August 1866; CLL, Aug–Dec 1866, fol. 299. A search of The Times Digital Archive reveals that during the nineteenth century advertisements for auctions bearing the phrase ‘oriental manuscripts’ occurred in 1827, 1833, 1836, 1837, 1838, 1839, 1853 (twice), 1857, 1860, 1867, 1869, 1889 and 1890. Of course, not all auctions were advertised in The Times, and many auctions would have included oriental manuscripts without explicit mention in the advertisement. This slight evidence is corroborated by an analysis of auctions recorded in Barwick, English Book Sales: in the period 1830–39, summary entries for 10 out of 638 auctions explicitly refer to oriental books and manuscripts (1.56%), but only 4 from 713 during the 1860s (0.56%). Inevitably many more auctions contained oriental material than those identifiable in Barwick, and it is not possible to derive absolute figures; however, the declining proportion of oriental auctions over these decades is incontrovertible. On John Nicholson, see Arberry, Oriental Essays, 197–8; Sieveking, Memoir and Letters, 130–212.

29 Ballantyne, Orientalism and Race, 44–9; Bayly, Empire and Information, 315–64.

30 Letter from Lilly to Lindsay, 3 January 1855; CLL, 1850‒56, fol. 140. Now Rylands Persian MS 932. Letter from Lindsay to Quaritch, [15 October 1877]; CLL, 1877, fol. 112. Now Rylands Javanese MS 7.

31 Lindsay, Oriental Manuscripts, ix–x. Ludovic borrows the wording used by his father in the Library Report, Introduction, p. 17.

32 Letter from Quaritch to Lindsay, 2 June 1863, and letter from Lindsay to Quaritch, 8 June 1863; CLL, Jan‒June 1863, fols 271, 281. The sale is described in Barker, Bibliotheca Lindesiana, 211. On van Alstein, see Callewaert, “Van kamergeleerden tot reizigers,” 142; Catalogue des livres et manuscrits.

33 On Lindsay’s Japanese collection, see Kornicki, “Japanese Collection.” On the collecting of Japanese books in this period, see Kornicki, “Collecting Japanese Books”; Lindsay is discussed on p. 29. Stephen Jones notes the influence of the Great Exhibition in fostering interest in Japanese art, arguing that ‘intellectual curiosity about Japanese art, as opposed to generalised enthusiasm for things oriental, cannot be identified before the 1850s.’ Jones, “England and Japan,” 150.

34 Invoice for the Pauthier sale; National Library of Scotland, Acc. 9769, Crawford Papers, Crawford Library Invoices, 1870–1, f. 62. Lindsay’s purchases are now Rylands Chinese books 79, 393, 431 and 451, Chinese drawings no. 35 and Tamil MS 1.

35 Catalogue des livres de linguistique; Bibliothèque chinoise. Receipt from Quaritch to Lindsay, 16 April 1874; National Library of Scotland, Acc. 9769, Crawford Papers, Crawford Library Receipts (hereafter CLR), 1871‒92, fol. 1396.

36 On Edkins, see Box, “In Memoriam”; “Joseph Edkins”; Bushell, “Nécrologie”; Cordier, “Rev. Joseph Edkins.” On Wylie, see Carlyle, “Wylie, Alexander.”

37 On missionary activity in China, see Austin, China’s Millions; Lodwick, Crusaders against Opium; Tiedemann, “Indigenous Agency.”

38 Edkins, Catalogue of Chinese Works.

39 An obituary and bibliography of Pleyte was published by Krom, Levensbericht van C.M. Pleyte Wzn.

40 Letter from Ludovic to Edmond, 15 October 1897; CLL, Sep‒Oct 1897, fol. 106.

41 Collecting of oriental manuscripts in the nineteenth century is under-researched, limited to profiles of individual collectors and studies of the provenance of institutional holdings. For the early modern period, see Ghobrial, “Archive of Orientalism.”

42 Bayly, Empire and Information, 291. See also Peers, “Colonial Knowledge.”

43 The phrase ‘lone wolf’ comes from Munby, Connoisseurs, 77.

44 Ganim, Medievalism and Orientalism, 3.

45 Harris, “Archibald Swinton,” 360. See also Ostergard, William Beckford, 217‒27, 337‒48; Hauptman, “Beckford, Brandoin, and the Rajah”; Garrett, “Ending in Infinity”; Saglia, “William Beckford.”

46 Ansorge, “Revd George Lewis.”

47 Jasanoff, Edge of Empire, 52.

48 On Polier and Pote, see Subrahmanyam, “Colonel Polier”; Hauptman, “Beckford, Brandoin, and the Rajah.”

49 Jones’s collection was transferred to the India Office Library in 1876. Cannon, “Sir William Jones,” 225–6; Tawney and Thomas, Catalogue of Two Collections.

50 Trautmann, “Wilkins, Sir Charles.”

51 Blake, “Colin Mackenzie”; Cohn, Colonialism, 81–91; Dirks, “Colonial Histories”; Kouznetsova, “Colin Mackenzie.”

52 Gombrich, “Colebrooke, Henry Thomas.”

53 Robinson, Descriptive Catalogue, xxii–xxiii, Ouseley, Catalogue.

54 Ouseley, Biographical Notices, v–ccxxvi; Robinson, Descriptive Catalogue; Ferrier, “Ouseley, Sir Gore.”

55 Rieu, Catalogue of Persian Manuscripts, xi–xii; Lane-Poole, “Rich, Claudius James.”

56 Penner, “Elliot, Sir Henry Miers”; Rieu, Catalogue of Persian Manuscripts, 22–4.

57 On trophies, see Stewart, On Longing, 147.

58 Elsner and Cardinal, Cultures of Collecting, 2. See also Jasanoff, “Collectors of Empire,” 113–14.

59 Anderson, Imagined Communities, 184.

60 Said, Orientalism. British universities were heavily implicated in imperialism: see Goff, Classics and Colonialism; Vasunia, “Greek, Latin.”

61 Letter from Lilly to Lindsay, 3 January 1855; CLL, 1850‒56, fol. 140. Receipt from Lilly to Lindsay, 15 January 1855; CLR, 1846‒55, fol. 798. Macan, Shah Nameh, xv. It is now Rylands Persian MS 932: see Robinson, Persian Paintings, 163–89.

62 McLean, “Professor Extraordinary”; Dalby, “Dictionary of Oriental Collections,” 254–7; Browne and Nicholson, Catalogue.

63 Beveridge, “Bland, Nathaniel.” The Bland collection comprised 204 Arabic, 12 Hindustani, 1 Parsi, 2 Pashto, 366 Persian, 2 Sanskrit and 69 Turkish manuscripts, as well as 5 Chinese and 9 Japanese books, and an unknown number of Chinese drawings; information kindly supplied by my colleague Elizabeth Gow.

64 Quaritch recalled, ‘Before my time several booksellers brought out large catalogues of Oriental MSS. for instance Straker, Howell & Stewart, and Cochrane.’ Letter from Quaritch to Lindsay, 28 August 1866; CLL, Aug–Dec 1866, fol. 299. On Bliss, see Davies, “Rebekah Bliss”; the sale is mentioned on p. 55.

65 Bland summarised his purchases of manuscripts up to 1838 on a small sheet headed ‘MSS’, now bound into a volume of his papers, memoranda and notes on oriental literature and superstitions. British Library, Add MS 30378, fol. 199.

66 Letters from Quaritch to Lindsay, 6 and 25 June 1866; CLL, Jan‒July 1866, fols 214, 239.

67 Receipts from William H. Allen & Co. to Lindsay, 17 June 1866 and 18 January 1867; CLR, 1863‒70, fols 1222, 1232. On Forbes, see Loloi, “Forbes, Duncan”; Forbes, Catalogue.

68 Letter from Quaritch to Lindsay, 28 August 1866; CLL, Aug‒Dec 1866, fol. 299.

69 Bhabha, Location of Culture, 128; Fulford, “Poetic Flowers.”

70 Huth and Ellis, Huth Library, 140, 518, 1181‒2, 449.

71 James, McClean Collection.

72 de Ricci, Hand-List.

73 Johnston, “Spending a Fortune,” 109. See also Cantone, Robert E. Hart’s Oriental Manuscripts; Johnston and Hartnell, Cotton to Gold.

74 de Hamel, The Rothschilds, 28, 53‒9.

75 Stoneman, “Linked Collections.”

76 Sotheby, Catalogue of a Magnificent Collection. Lindsay purchased 3 Balinese, 2 Buginese, 1 Kawi, 3 Javanese, 1 Madurese and 1 Malay manuscript at the Bragge sale.

77 Letter from Quaritch to Lindsay, 12 April 1864; CLL, Jan‒May 1864, fol. 157.

78 I have identified only one academic paper citing manuscripts while they were in Bragge’s ownership: Franks, “Two Manuscript Psalters.”

79 Bayly, Empire and Information, 150.

80 Stewart, Descriptive Catalogue, v.

81 Maya Jasanoff argues that ‘the history of collecting reveals the complexities of empire; it shows how power and culture intersected in tangled, contingent, sometimes self-contradictory ways.’ Jasanoff, Edge of Empire, 6.

82 On the effects of Napoleon’s campaigns upon the book trade, see Jensen, Revolution, 32–67.

83 Library Report, Introduction, p. 19. On Alexander Lindsay, see Henderson, “Lindsay, Alexander.” On Robert Lindsay, see Barker, Bibliotheca Lindesiana, 24–6.

84 Printed catalogue slip, presumed to be from Bernard Quaritch, pasted into the unpublished “Handlist of Hindustani, Marathi & Panjabi MSS” in the Bibliotheca Lindesiana, now at the John Rylands Library. Letter from Lindsay to Quaritch, n.d.; CLL, 1862, fol. 144. Dating from the late seventeenth century, the manuscript (now Rylands Punjabi MS 5) is one of the earliest surviving Granths and an object of deep reverence by Sikhs.

85 Obituary of Hamilton in Royal Asiatic Society, “Forty-Fifth Anniversary Meeting.” The Crawford Hamilton collection comprised 303 Arabic, 407 Persian and 7 Turkish manuscripts: information kindly supplied by Elizabeth Gow.

86 Letter from Quaritch to Lindsay, 17 July 1868; CLL, July‒Dec 1868, fol. 334. Judith Green makes a similar point concerning the theft of Chinese ethnographic material: Green, “Curiosity, Art and Ethnography,” 125.

87 Letter from Quaritch to Lindsay, 10 July 1868; CLL, June‒Dec 1868, fol. 318. On the Magdala library, see Pankhurst, “Library of Emperor Tewodros II.” For a contemporary account of the looting of Magdala, see Stanley, Coomassie and Magdala, 154–6.

88 Letter from Lindsay to Quaritch, 21 July 1868; CLL, June‒Dec 1868, fol. 339.

89 Leerssen notes Carlyle’s similarly unsentimental acceptance of the extermination of native Americans. Leerssen, “Englishness, Ethnicity,” 66–7.

90 Richards, Imperial Archive, 15.

91 Letter from Edmond to Ludovic, 16 May 1898; CLL, May‒June 1898, fol. 236. One of the items is now Rylands Kawi MS 2; the other has not been identified. The Dutch removed 425 lontar manuscripts from Cakranegara in 1894: Fitzpatrick, “Public Library,” 276.

92 Behrend, “Manuscript Production,” 427.

93 Likewise, Alison Petch notes that Pitt-Rivers and A.W. Franks collected ethnographic objects second-hand, rather than directly from indigenous sources. Petch, “Assembling and Arranging,” 240.

94 On local agency, see Dirks, “Colonial Histories.” I am grateful to Prof. Anindita Ghosh for this reference.

95 Ballantyne, Orientalism and Race, 15.

96 Letter from Lindsay to Min, 22 May 1872; CPP, 94/21. Quoted in Barker, Bibliotheca Lindesiana, 248.

97 Schmidt, “Johannes Heyman,” 75; Schwab, Oriental Renaissance, 45–6.

98 Schwab, Oriental Renaissance, 43, argues that ‘the Oriental Renaissance – though not Indic studies themselves – had only an ephemeral career in […] England.’