ABSTRACT

This article examines how the Hong Kong government promoted and preserved Chinese culture through postage stamps and coins. It shows that colonial officials attempted to utilise these tangible forms of Chinese culture to win popular support from the 1960s on. This was an era when the British and colonial governments hoped to hold onto Hong Kong before discussing the colony’s future with Chinese leaders. Colonial officials thus attempted to secure public trust and improve the government’s image. This article analyses cultural policies of this era. It reveals how colonial administrators featured traditional Chinese culture in postage stamps and coins to showcase their ‘imagination and sensibility to what appeals to Hong Kong people’, a phrase used by Secretary for Chinese Affairs John Crichton McDouall in the 1960s. While previous studies have shown how colonial authorities utilised objects to reinforce imperial superiority and construct a sense of the Other, this article argues that political calculations made Hong Kong officials appear to respect how local people actually understood their culture. By cooperating with the Crown Agents and the Royal Mint, colonial administrators incorporated Chinese symbols in these everyday objects to demonstrate their care for the people’s culture.

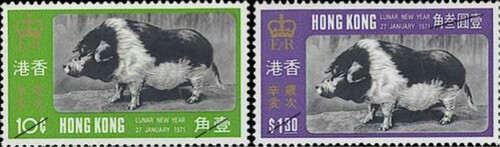

In August 1970, a quarrel about pigs arose between the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the Hong Kong government. Colonial officials had submitted designs of postage stamps commemorating the Lunar Year of the Pig, which would begin in January 1971. However, Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs Alec Douglas-Home rejected this outright: the pig image was in ‘bad taste’.Footnote1 Governor David Trench defended the design. Hong Kong people treasured the Lunar New Year stamps, he argued, and discontinuing this series would lead to public discontent. ‘Regret I do not consider it feasible to produce a satisfactory design commemorating the Year of the Pig without incorporating a pig’, Trench replied in a telegraph, ‘and I also do not consider it possible to explain the absence of a 1971 commemorative issue without causing much comment and some ridicule’.Footnote2 London and Hong Kong officials eventually compromised. After understanding the local importance of the stamps, Douglas-Home softened his tone and explained that he simply objected to the design, not the issue.Footnote3 Local officials accommodated Douglas-Home’s taste by replacing the local Chinese pig with a boar.Footnote4

Similar episodes occurred in Hong Kong from the late 1960s on. This article argues that the colonial government attempted to show its care for local customs by featuring Chinese culture on postage stamps and coins, two objects that were circulated and advertised in people’s everyday life. Scholars have revealed and examined how the Hong Kong government initiated reforms in areas such as education, housing, and the fight against corruption. With more declassified files, recent scholarship has revisited these reforms. It has shown how colonial officials surveyed and constructed public opinion, how they had already formulated the reforms from the early 1960s on, and Governor Murray MacLehose was in many ways a reluctant reformer.Footnote5 Instead of focusing on how the government tried to close the gap of communication between society and the state, this article reveals how it utilised people’s culture and their émigré attachment to China to shape public opinion and create a benevolent image of itself.

Contemporary local events and Anglo-Chinese diplomacy help contextualise this colonial policy. After hundreds of youths rioted to voice their social discontent in April 1966, the government recognised the need to close the communication ‘gap’.Footnote6 Inspired by the Cultural Revolution in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), another series of riots started in May 1967 and lasted for over six months.Footnote7 After suppressing the violence, the British and colonial governments realised that Hong Kong’s future ‘must eventually lie’ with the PRC. They hoped to hold onto the colony before discussing Hong Kong’s future with Chinese leaders.Footnote8 The British and PRC governments later agreed to maintain a status quo for the time being: in 1971, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai reasserted the PRC’s Hong Kong policy of ‘long-term planning and full utilisation’. He expressed to the British side that the PRC did not intend to take back Hong Kong until 1997, when the New Territories lease would expire. In response, Douglas-Home proposed to his cabinet that the British government should maintain the status quo and only raise the Hong Kong issue with the PRC later. The early 1970s was an era when the two countries embarked on a new series of communication and established diplomatic relations. The (potentially contentious) issue of Hong Kong had nowhere to stand in this new Anglo-Chinese diplomacy. In 1972 the PRC’s permanent representative at the United Nations Huang Hua requested that Hong Kong be removed from the list of colonial territories. However, British officials saw his action as a mere reaffirmation of the PRC’s long-term position on the colony and took no further action.Footnote9 This development gave the British and colonial governments an opportunity to hold onto Hong Kong and stabilise this colony until the early 1980s, when the expiry of the New Territories lease was approaching.

Hong Kong officials did not merely stabilise their colony. Murray MacLehose, the newly inaugurated governor in 1971, devised local strategies that aimed at safeguarding metropolitan interests in future negotiations regarding Hong Kong. In October 1971, he wrote to the FCO that his aim ‘must be to ensure that conditions in Hong Kong are so superior in every way to those in China that the CPG [Central People’s Government] will hesitate before facing the problems of absorption’.Footnote10 Later in May 1972, he also expressed to the FCO that the colonial government should improve Hong Kong’s conditions to prepare for ‘the best prospect for the least unsatisfactory arrangement with China on the long term future of the Colony’.Footnote11 In other words, to MacLehose, improving Hong Kong’s conditions was a way to preserve British interests. As MacLehose also stated in his dispatches to the FCO, this strategy included programmes in areas such as housing, education, and cultural development.Footnote12 Though commemorative stamps had existed in the colony before MacLehose took up his governorship, their continuous and increasing appearance during the 1970s reveals how colonial officials further demonstrated their care for people’s culture under the above context. As later sections show, the early attempts were also part of the government’s efforts to improve its image after the disturbances.

Officials utilised Chinese culture to help them improve relations with the local population. While people in Hong Kong and the world today tend to view the city as a place with its own identity, we must be careful about reading history through the present. From the mid-1940s on, waves of refugees fled to Hong Kong from mainland China.Footnote13 The ‘sojourner mentality’ of these immigrants began to fade during the 1950s, and a Hong Kong local identity emerged during the 1970s in contrast to the mainland Chinese identity.Footnote14 Nevertheless, a large group of the émigré and the locally new-born populations concurrently held a cultural attachment to China. Focusing on refugee scholars and teachers, Bernard Luk described this phenomenon as ‘a Chinese identity in the abstract’ and ‘a patriotism of the émigré’. Even though these scholars settled in Hong Kong, they were not interested in local history. Instead, they continued to teach and research Chinese culture and history. This situation posed a problem to the colonial government, which was countering Chinese patriotism through education during the 1950s.Footnote15

Local leaders during the 1970s also publicly expressed their attachment to Chinese culture. In their view, the Cultural Revolution in mainland China had devastated much of the Chinese tradition and they needed to preserve the customs that were still present in Hong Kong.Footnote16 For instance, Director of Cultural Services Darwin Chen urged the government to save the remains of Chinese culture, and merchant Yu Lok-yau attempted to promote Chinese traditions for all generations through lantern carnivals in Victoria Park (which is still an annual event today). Some social leaders also urged the government to stop discriminating against Chinese culture. Urban Council member Denny Huang, for example, called for an improved status of the Chinese language during the early 1970s.Footnote17 Part of the younger generation also inherited this ‘Chinese identity in the abstract’. From the late 1960s on, student activists demanded that the government recognise Chinese as an official language in the colony.Footnote18 Later during the early 1970s, university students protested against Japan’s claims to what China calls the Diaoyu Islands (and Japan calls the Senkaku Islands).Footnote19 Even though Hong Kong’s population paid greater attention to local issues in the late 1970s, their cultural attachment to various Chinese traditions persisted. As later sections reveal, objects featuring traditional Chinese culture, especially the Lunar New Year, were well received among the local population.

Chinese culture is a notion that has evolved in the recent century.Footnote20 This study focuses on Chinese cultural items that colonial officials perceived to be useful in securing people’s trust. These officials preserved and promoted traditional Chinese culture that was present in Hong Kong. Examples included festival celebrations, Cantonese operatic performances, and monuments.Footnote21 To colonial officials, these items were part of the local culture, as many Hong Kong people were still attached to them. In other words, a notion of cultural ‘Chineseness’ existed in local people’s everyday life. The colonial government utilised this characteristic of local society to suit people’s preference and hope to secure their support. By cooperating and negotiating with the Crown Agents and the Royal Mint, colonial officials incorporated Chinese symbols in postage stamps and commemorative coins.

Objects and Colonialism

Historians have written much on objects and colonialism since Bernard Cohn published his classic Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge. ‘An object’, Cohn argued, ‘can be transformed through human labor into a product which has a meaning, use, and value’.Footnote22 He showed how British colonisers constructed a history of India and established their superior status over the colonised through objects such as antiquities, war relics, and guidebooks. Later works have further revealed how colonisers and collectors added their own meanings to colonial objects, such as indigenous relics, images (both photographic and artistic), and crafts, to reinforce imperial superiority, and sometimes to construct a sense of Otherness among Western audiences.Footnote23 Some sellers and collectors exoticised native arts and crafts to boost tourism and trade.Footnote24 Nevertheless, as David Washbrook has reminded us, we should not regard colonial culture as merely the ‘West’ imposing its norm on the Other. Such an overview across the ‘entire colonial (and European) cultural experiences’ risks being anachronistic.Footnote25

Instead of simply showing how colonial officials created their own meanings for objects, this article reveals how they created objects that promoted and preserved local culture. To be sure, the colonial government did so not out of benevolence, but to secure trust. The context of late colonial Hong Kong prompted the government to respect how its people actually understood their culture. Existing works on British late colonialism reveal how officials attempted to maintain imperial influence and leave legacy through cultural agencies and products in the post-war era.Footnote26 The case of Hong Kong demonstrates how this cultural project not only spread metropolitan culture but also promoted peripheral culture later in the twentieth century.

This article focuses on postage stamps and coins, two objects that were circulated in everyday life. They were items that people from different classes, sectors, and education background would inevitably encounter. The low costs of postage stamps, for instance, enabled more ordinary people to perceive them as collectables in contrast to luxurious objects such as antiques.Footnote27 Various scholars have reminded us of the importance of philatelic evidence in historical research. Much of this effort focuses on the semiotics and symbolism of postage stamps, while Donald M. Reid has explained that they can be a source for topics such as the history of printing technology, postal services, and communication systems.Footnote28 Studies on numismatics also focus much on the symbolic aspects of coins, be they from pre-modern or modern eras.Footnote29 Through extensive archival research, this article shows that the design and production processes also deserve attention: officials, in both London and Hong Kong, British and Chinese, communicated and negotiated on the designs of the objects to ensure that the products would conform to local perception. Using postage stamps for political purposes, however, was not something new to the British imperial world. Britain and its territories had issued commemorative stamps to mark celebratory occasions, such as the victory in the First World War, the Silver Jubilee of George V, and the British Empire Exhibition of 1924–25. In some cases, the issuing territories could add local elements in the stamp designs.Footnote30 However, the purpose of issuing commemorative stamps changed in 1960s’ Hong Kong. Instead of demonstrating British superiority or strengthening ties between territories and London, colonial administrators attempted to use stamps to showcase their care for local culture.

Existing studies of objects in Hong Kong focus largely on those for exhibition and display, such as museum exhibits, arts, and buildings. These works focus primarily on interpreting the meanings of the objects or the collecting process.Footnote31 This article brings a new perspective by examining how colonial administrators utilised objects circulated in everyday life to maximise their impact, and how they created the objects that conveyed the meanings they wanted. As later sections reveal, Hong Kong officials also sought to promote these cultural products to the wider world. For British agencies, this was simply to increase revenue. For colonial officials, however, it was a way to show people in and outside Hong Kong how well they preserved the region’s culture.

Postage Stamps for the Lunar New Year

Officials from both the British and Hong Kong governments cared greatly about postage stamps. The Colonial Office and, later, the FCO, tightly monitored the issuance of postage stamps for British dependent territories, including Hong Kong. The FCO believed that dependent territories lacked ‘local talent capable of arranging and supervising the design and production of stamps’, and local administrators ‘do not have the expertise to deal with developments in the international philatelic business’.Footnote32 All issues thus required the approval of the monarch and the British government, which had the ‘ultimate responsibility in the final analysis’.Footnote33 The Crown Agents, based in London, acted as the middleman between London and Hong Kong (and other dependent territories). Although the agents were a private organisation largely independent of the British government, they followed instructions from the British government and helped territories design, ship, and print postage stamps.Footnote34 Whereas Hong Kong officials often saw the agents as providing unsatisfactory service and causing delays in stamp production, they were backed by London. The Hong Kong government also recognised that cooperating with the agents helped the government obtain the Queen’s approval.Footnote35

The British government valued postage stamps because they generated revenue, created employment opportunities, and incorporated royal symbols. British officials also attempted to build ‘a respectable image’ of Commonwealth countries and dependent territories. They believed postage stamps could boost a territory’s tourism by ‘putting it on the map’ of collectors.Footnote36 Colonial officials prepared Hong Kong’s postage stamps under the above contexts. For instance, Hong Kong had to seek London’s approval before it could start designing its first pictorial issues in 1968.Footnote37 The FCO also required Hong Kong to submit stamp proposals at least eighteen months beforehand. As royal symbolism, such as the crown, had to appear on all stamps of British dependent territories, London officials would reject designs which they perceived to be inappropriate.Footnote38 The office sometimes instructed Hong Kong and other dependent territories to produce Commonwealth-wide issues, such as the one commemorating the Queen’s silver wedding anniversary in 1972.Footnote39

Hong Kong people also cared about postage stamps. From 1968 to 1983, the leading local newspaper Wah Kiu Yat Po (literally meaning the Overseas Chinese Daily News in Cantonese, though its focus in this era was local) dedicated a bi-weekly section titled ‘Philately’. During the 1970s, it faced fierce competition from other newly founded newspapers such as Ming Pao, Oriental Daily, and Hong Kong Economic Journal. A regular section could survive only if it enjoyed a wide readership.Footnote40 The stable appearance of the philately section in the Wah Kiu Yat Po reveals the popularity of stamp collecting. As later sections show, postage stamps, especially those featuring traditional Chinese culture, sold well in Hong Kong.

The colonial government utilised postage stamps to promote traditional Chinese culture. In 1965 Hong Kong’s postmaster general received a suggestion from the Crown Agents: the colony could produce stamps to commemorate the Lunar New Year, and this could help increase local revenues and publicise the city. As the agents suggested, the government could produce stamps that would ‘most definitely appeal to the local Chinese’ by featuring the ‘customary Chinese way of designating lunar years’ and the zodiacal animal of the year.Footnote41

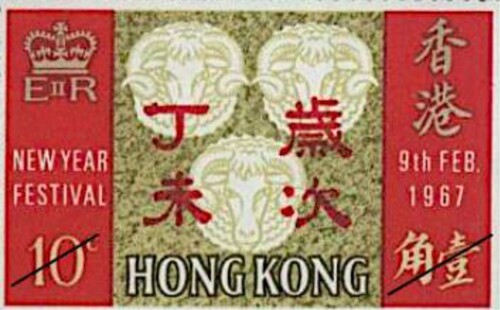

For the Crown Agents, selling postage stamps was about profit. For the Hong Kong government, however, it was a way to improve its image. Secretary for Chinese Affairs John Crichton McDouall, who was responsible for advising the government on local Chinese issues, supported this proposal. He did so not only because of the additional revenue the issue could bring, but because of the ‘local appreciation of this evidence of Government’s imagination and sensibility to what appeals to Hong Kong people’ and the ‘prestige value for Hong Kong abroad’.Footnote42 Within the same year, there was also some correspondence to the South China Morning Post, the colony’s leading English newspaper, arguing that local stamps should ‘stand for the culture and spirit of a city’. The anonymous writer also stressed how postage stamps were a ‘highly economical and effective weapon’ for promoting tourism due to their ‘ubiquitous peculiarity’.Footnote43 Officials implemented this proposal in 1966 and issued the first Lunar New Year stamps in 1967, after the government suppressed the Star Ferry Riots and recognised the importance of building a sense of belonging. They emphasised how the designs of the new stamps could please local Chinese. For instance, they commented that designers should use the ‘lucky Chinese red colour’.Footnote44 Governor David Trench also insisted that the shade of red in the original design did not fit into traditional Chinese celebration well.Footnote45 shows the image of the 10¢ denomination of this stamp issue.

Hong Kong officials, with the help of the Crown Agents, succeeded in attracting both local and overseas collectors. The Hong Kong Post Office marked the first day of sale by organising a small ceremony, with Colonial Secretary David Irving Gass being the first person to buy the stamps. Crowds queued for hours that day to purchase the commemorative stamps, even though the office announced that they would be on sale for the rest of the month. Postmaster General Alfred George Crook told the press that the government issued the stamps so the public could send New Year greetings to their friends.Footnote46 He later described this issue as ‘successful’ and ‘well received’.Footnote47 Overseas sales also surpassed other Hong Kong stamps. Crown Agents reports reveal that the Lunar New Year issue outsold all others of 1966. The revenue generated by this issue was also greater than previous commemorative issues, such as the World Health Organisation Stamp issue and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation issue. Even though the pictorial issue of 1968 included stamps in six denominations, the average sales volume of each denomination was still lower than that of the 1967 Lunar New Year issue.Footnote48

The Hong Kong government realised the popularity of these Lunar New Year stamps and thus proposed to the FCO that it should produce such stamps every year. Through producing a postage stamp series with a complete cycle of the twelve Chinese lunar years, the government could demonstrate how it cared about the Lunar New Year, ‘the principal period of celebration with the Chinese’.Footnote49 Postmasters general required designers to incorporate items which they believed looked pleasant to Chinese people on upcoming stamps. As the Hong Kong government had to submit stamp proposals for FCO’s approval, it began the design process one to two years in advance. In 1967, J. A. Taylor in the General Post Office suggested that designers of the next issue include water and trees, which were associated with the year, and red colour, for which the public would ‘undoubtedly find general favour’.Footnote50 The following year, Taylor required dogs, background colours, and calligraphy appearing on the 1970 stamps to conform with Chinese traditions.Footnote51

Postmasters general relied on Chinese officers from the Secretariat for Home Affairs to make the designs conform with traditional Chinese images. During the late 1960s, the Hong Kong government started to become more responsive to the people’s concerns. The Secretariat for Home Affairs (reorganised in 1969 from the Secretariat for Chinese Affairs) took up this mission. It recruited Chinese officers to help the government communicate with the people and handle local Chinese matters.Footnote52 These officers were knowledgeable about Chinese culture. Postmasters general thus relied on their advice, especially those on Chinese geomancy, to design the commemorative stamps. Geomancy mattered greatly to Chinese communities. As today, many local people deeply believed in its principles, which specify the symbols and elements (such as animals, colours, and numbers) that would help maintain or destroy a person’s well-being.Footnote53 Officials were thus cautious to ensure policies did not violate geomantic rules.Footnote54 In 1971, for instance, officer H. K. Chan commented to Postmaster General Cecil George Folwell that the rats on the 1972 stamp should ‘look smart and pleasant’ and should not be running or eating. Designers should also use dark, red, or white colours instead of yellow, which could imply bad luck in this year. Water could appear in the design as it was an ‘auspicious element’.Footnote55 In 1973 another officer, K. L. Wong, commented that a white rabbit was acceptable from the ‘traditional point of view’, while twilight and grass were the ‘auspicious’ elements of the year as they symbolised growth.Footnote56

These officers sometimes provided images for designers, who might be foreigners, to draw animals in the proper Chinese ways. For instance, in 1974 Wong informed Taylor that the dragon’s design should follow the style of the renowned Lingnan School painter Chao Shao-an, so that the stamps could show 1976 as ‘a year of affluence and abundance’ with ‘promises of success’.Footnote57 In 1975 the officer reminded Taylor that the snake on the 1977 stamps should match the one described in the ancient Chinese tale ‘Search for the Sacred’: the snake should be ‘in a coil with its head raised above the body’ to show that snake was a ‘grateful creature’ and ‘indicative of dignity’.Footnote58 Taylor later chose a design with an unnatural snake because it looked similar to Chinese tradition. In 1976, Wong suggested that the stamps for 1978 should reveal the good qualities of the horse by Chinese standards: ‘speed, stamina and freedom’. The officer also proposed specific designs, such as ‘a single white steed charging at full speed’ and ‘a running horse’ that would ‘signify progress and a free spirit’.Footnote59 The Stamp Advisory Committee also recommended that designers reproduce famous Chinese paintings of horses on the stamps.Footnote60

Meanwhile, colonial officials eliminated any elements that might imply misfortune or adversity. In 1968 they had to re-design the stamps because the cock on the design had a ‘split’ tail, a sign of bad luck for some Chinese people.Footnote61 In 1970 the postmaster general also reminded the designer that only one dog should appear on each stamp because ‘two dogs side by side would form a Chinese character which conveys the idea of imprisonment’, while three dogs would mean ‘tempest’.Footnote62 He also noted that the colour red should not appear as it was destructive to white, the symbolic colour for the year.Footnote63

Postmasters general gave similar orders to designers in other years. In 1969 the designer could draw neither a running pig nor pigs in pairs because such images would carry ‘a sense of war’.Footnote64 In 1971 the designer was asked to draw an ox, but not a tame cow or a bull, and not to use green as it was the ‘prohibitive colour of the year [1973]’.Footnote65 In 1972 the designer could not draw a white tiger for the 1974 stamps because it was ‘objectionable from the traditional point of view’.Footnote66 In 1974 a Chinese officer, Wong Ki-lin, advised the designer of the 1976 stamps that ‘only the head of one dragon should appear in the design and the abdomen and the exterior parts of the dragon should not appear in the stamps,’ as this was the ‘viewpoint accepted by the community at large’.Footnote67 Even the Executive Council occasionally intervened in the design process. For instance, in 1973 its members required the designer to change the background colour of the stamps from light blue to pale purple or violet. They consulted the Secretariat for Home Affairs and realised that light blue implied ‘inauspicious’ happenings, such as death.Footnote68

The government emphasised not only the visual, but also the biological aspect of the animals. In 1970 officials stressed that the pig on the 1971 stamps should be a ‘locally improved breed of Chinese pig’. They did so because, according to the Agricultural and Fisheries Department, local farmers had started to use this type of pig for breeding and the department hoped to further promote this local Chinese breed.Footnote69 As we have already seen, local officials defended the design when a controversy arose over the pig postage stamp. Apart from explaining the stamp’s local importance, Governor David Trench also pointed out to the FCO that Taiwan had already followed Hong Kong to issue Lunar New Year stamps, with the next one featuring pigs.Footnote70

This correspondence reveals that Hong Kong officials were aware of cultural policies across the Taiwan Strait. In November 1966, Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government initiated the Cultural Renaissance Movement. Chiang’s regime demonstrated its efforts in safeguarding Chinese traditions in contrast to the perceived assault against heritage, customs, and culture in mainland China during the Cultural Revolution. This was ‘cultural combat’ against the PRC.Footnote71 As for the case of Hong Kong, the colony provided a base for the United States to launch its cultural warfare again communism during the 1950s.Footnote72 Currently, there is no available archival evidence showing that the colony’s postage stamps were part of the cultural warfare from the late 1960s on. Nevertheless, the development in Hong Kong resembles the cultural politics in the wider East Asian region. To colonial officials, issuing Lunar New Year stamps could help them illustrate their reverence for Chinese traditions, given the cultural destruction in mainland China and the local call for cultural salvage (as mentioned at the beginning of this article).

After understanding the significance of the stamps, Douglas-Home changed his stance and simply required Hong Kong officials to revise the design. Local officials then included a boar in the design ().Footnote73 In the following year, local officials again tried hard to make London approve the rat stamps. They collected public opinion through City District Offices, where political officers collected people’s views and received complaints about government policies from the late 1960s on, and reported to London that the issue was feasible because of public support.Footnote74 For instance, people expressed that they were enthusiastic about the upcoming issue and believed rats represented ‘wit, vitality and alertness’. One interviewee strongly supported issuing rat stamps and even suggested putting Mickey Mouse on the design.Footnote75 While scholars have revealed how tensions grew between London and Hong Kong due to issues such as social security, fiscal matters, and policy blueprints, the above examples show that misunderstanding also existed over local culture.Footnote76 Nevertheless, the compromise between the two sides reveals how both London and Hong Kong officials valued the cultural strategy of preserving Chinese culture.

These stamps clearly appealed to Hong Kong people. In 1968 one of the stamps featuring the Year of the Monkey was ‘running out’ within the first few days of sale.Footnote77 One month later, Taylor reported to the Crown Agents that all monkey stamps were sold out.Footnote78 In 1969 the Lunar New Year stamps brought doubled revenue to the Post Office on the first day of sales. Controller of Post S. L. Mak reported that the total revenue on that day was HKD 140,000, while the daily average revenue was only HKD 60,000. People also had to queue for a long time even though the office arranged additional staff to serve in the post offices.Footnote79 One internal report shows that the sales of Lunar New Year stamps were usually higher than those of others.Footnote80 The Crown Agents also initiated global promotion campaigns for the stamps. Every year the agents reported to the colonial government all advertisements on overseas publication, including those in Europe, Asia, and Oceania.Footnote81

Postage Stamps for Hong Kong Chinese: More Episodes

Hong Kong officials also inserted Chinese culture in other stamp issues. In 1971 officials planned to produce a new definitive issue for the colony. They required the stamps to have ‘a representation of Her Majesty combined with motifs of an essentially Chinese character’. Several British companies, such as Harrison & Sons and De La Rue, submitted designs to the government. Officials, including Governor Trench, preferred the designs from Harrison & Sons because they were more ‘Chinese’: they included ‘a Chinese carpet which depicts the peony, symbol of prosperity’ which were ‘often used as temple hangings in the late 17th century’, a ‘flower panel derived from a 17th century carved lacquer tray’, and also a unit pattern from a porcelain dish in Qing China. The Executive Council later selected the second design for all denominations.Footnote82

Postage stamps commemorating the Festival of Hong Kong also displayed Chinese culture, as if the festival was somehow a traditional Chinese one. The Hong Kong government held this festival bi-annually from 1969 to 1973 to develop a sense of local identity.Footnote83 In December 1970 the Festival of Hong Kong Office submitted draft designs to the postmaster general. While the Festival of Hong Kong included more than Chinese culture, the designs featured only Chinese elements (except the festival logo).Footnote84 Designer Kan Tai Keung recalled in an interview that this issue was a breakthrough as this (together with the pig stamps) was the first time the government had ever invited a local Chinese artist to design the stamps. He believed local stamps should have higher standards comparable to British designs and should feature Chinese cultural elements. His designs thus used Chinese calligraphy and graphics in modern ways. This opened the way for colonial officials to cooperate with local Chinese designers.Footnote85 The government later drew attention to these Chinese elements when it publicised the festival stamps: its press release emphasised ‘Chinese girls dancing’ and the ‘Hong Kong flower emblem combined with a figure from a Dragon Dance’ as the focuses of the designs.Footnote86

The story repeated itself in 1973, when officials were preparing for the commemorative issue of the next Festival of Hong Kong. Taylor noted that ‘subjects with a distinctive Chinese theme would be preferred’.Footnote87 Officials liked the 1971 designs by Kan, and they invited him again to design both the stamps and the first day cover. He continued to emphasise Chinese culture and focused on calligraphy this time.Footnote88 The government later introduced the issue as stamps featuring ‘a stylised version of a single Chinese character made up of a combination of festival symbols’.Footnote89

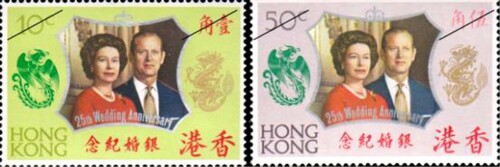

Even stamp issues commemorating royal occasions included local Chinese culture. In 1971 the Crown Agents informed the British dependent territories that they should issue stamps to commemorate the silver wedding anniversary of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip. The agents also suggested to the Hong Kong government that the colony’s stamps should include ‘Chinese junk boats in harbour scene’ and ‘head of a chow’ dog, which the agents believed could represent Hong Kong. Though Postmaster General Malki Addi disagreed with these symbols, he agreed that the Hong Kong stamps should include representative items of the city. He then proposed to include a dragon and a phoenix, which represent jubilation and luck.Footnote90 H. K. Chan of the Secretariat for Home Affairs agreed with Addi’s choice and recommended that he refer to the book Treasures of China for images of dragons and phoenixes in Chinese culture.Footnote91 Similar to how former officials prepared for the Lunar New Year issues, Addi consulted experts so the designs would match the perception of the two mythical creatures in Chinese communities.Footnote92 The Executive Council later suggested changing the Chinese characters of the stamps into red, the celebrative colour in the Chinese tradition.Footnote93 Local officials also attempted to make this cultural product reach the largest possible audience through understanding people’s habits. They first planned to issue only a 50¢ stamp. However, they later realised that Hong Kong people seldom used postage stamps of such a high value. They then decided to issue a 10¢ domination (), which was more common in local postage during the 1970s.Footnote94

Figure 3. Postage Stamps Commemorating the Silver Wedding of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip, 1972.

The Hong Kong government also emphasised Chinese culture in later stamp issues which commemorated royal occasions. In the 1973 issue for the wedding of Princess Anne, the Queen’s daughter, the government invited Fung Hong-hau, ‘the most famous calligraphist’, to furnish the Chinese characters into a traditional style. It also required the designer to use mainly pink and fuchsia because ‘reddish colour is traditionally considered auspicious for such an occasion’.Footnote95 In 1976 the Crown Agents invited governments of dependent territories to produce a stamp issue that celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of Queen Elizabeth’s accession to the throne. The agents also asked each government to include in the issue one local scene related to the Queen.Footnote96 As with previous issues, the Hong Kong government chose a scene that showcased Chinese tradition in Hong Kong. It selected the scene in which the Queen dotted the eye of a dragon (bringing the dragon to life) during her visit in 1975.Footnote97 While the stamps were made to commemorate the royal occasion, they also attempted to show Hong Kong people that even the British monarch and her government cared about traditional Chinese culture. The Stamp Advisory Committee later decided to make this ‘eye-dotting’ scene as the design for the $1.30 denomination, which was usually used for airmail postage to Britain and Europe. The committee believed that the scene was of higher ‘novelty’ to these places.Footnote98 This helped promote local traditions to overseas audiences.

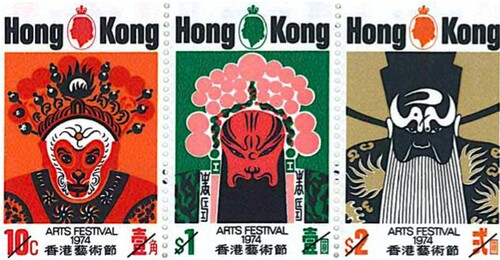

Local officials sometimes emphasised Chinese culture on stamps, even for events that did not fully focus on it. In 1972 they started discussing how to design stamps for the Hong Kong Arts Festival of 1974. They concluded that the stamps should only show ‘the performing arts giving emphasis to Chinese culture’, and the designer decided to feature the masks in Cantonese opera, each featuring one mythical or historical figure: Sun Wukong (the Monkey King), Guan Yu (the Martial God), and Bao Zheng (the legendary Judge Bao) ().Footnote99 On the one hand, officials utilised the stamps to commemorate the festival. On the other hand, they promoted Hong Kong as a traditional Chinese place, even though the festival did not merely include Chinese culture.Footnote100 A South China Morning Post report commented that ‘although Cantonese opera does not have a particularly prominent place in this year’s festival, the stamps show the more picturesque side of traditional Hongkong and will perhaps help to draw more overseas visitors to future festivals’.Footnote101

Similar situations occurred in later years. In 1974 the government planned to issue stamps that featured local festivals. However, the Home Affairs Department suggested including traditional Chinese festivals only, and the postmaster general agreed ().Footnote102 This issue also illustrated Hong Kong’s position as more Chinese than China. As the South China Sunday Post explained, ‘the various festival stamps of Hongkong are of interest to folklore students, as this island colony retains, even in this modern age, various ancient Chinese customs which are no longer practised in China itself’.Footnote103 In other words, the colonial government seized again this ‘Chineseness’ of Hong Kong and publicly illustrated its understanding of local culture. Later in 1978, London allowed Hong Kong to produce a stamp issue featuring local rural architecture. Local officials decided to include only traditional Chinese structures in the designs, such as the Hakka Wai and various ancestral halls in the New Territories.Footnote104 The official introductory text of the issue described the architecture as ‘fine examples of Chinese rural architecture of historical interest’. Images on stamps also displayed the traditional Chinese geomancy embedded in the structures: fung-shui (literally meaning wind and water).Footnote105 This stamp issue complemented official efforts to preserve these Chinese monuments, which was another attempt to suit people’s cultural preference and secure their trust.Footnote106

The General Post Office also helped the colonial government to secure local people’s trust through replying to their philatelic suggestions and enquiries. Throughout the 1970s, many local Chinese proposed postage stamps designs or ideas through letters. Though most of their ideas were rejected, they were still respected by officials. Through bureaucratic language such as ‘your suggestions have been noted and will be borne in mind for the future planning’, the General Post Office at least superficially paid attention to the proposed ideas, without giving a poor image of the government to local Chinese.Footnote107 A resident even suggested to the postmaster general that ‘it is the wish of the majority of the Hong Kong residents like [sic] to see all designs of stamps are the work by one of them’.Footnote108 An official replied with a list of all postage stamps designed recently by local artists, trying to prove how the government had respected its people.Footnote109 Moreover, the General Post Office usually selected Chinese officials to reply to these letters in Chinese, giving a sense to the public that local Chinese had a say in government. During the late 1960s and 1970s, local youth and activists became aware of how government policies discriminated against local Chinese who could not speak English. They thus demanded that the government recognise Chinese as an official language and be willing to communicate with its people in Chinese. The government pacified them with the Official Language Ordinance and various bureaucratic reforms.Footnote110 Responding to people’s concerns, stamp issues in this case, thus constituted part of the government’s attempts to gain their trust, to improve its image, and, in MacLehose’s planning, to preserve British interests in Anglo-Chinese diplomacy.

Commemorative Coins

London and Hong Kong also cared whether the designs of local coins were in proper Chinese styles. For instance, in October 1977 officials commented on the design of the new one-dollar coin. The Chinese character for ‘dollar’ was ‘too rounded at the bottom left hand corner’ and some of the designs had to be more accurate in the ‘particular style of Chinese writing’.Footnote111 In the second half of the 1970s, officials also started using commemorative coins for similar purposes as postage stamps: to show that the colonial government cared about people’s customs. The first Hong Kong gold coin for legal tender appeared in 1975 to commemorate Queen Elizabeth’s visit.Footnote112 Officials later suggested issuing coins to celebrate the festival most valued by the local Chinese population: Lunar New Year. From 1976 on, the Hong Kong government commissioned the Royal Mint to produce gold coins to celebrate the festival and to ‘trace the years of ancient Chinese Lunar Cycle’.Footnote113

The government greatly valued these coins. In 1976, when it issued them for the first time, it emphasised that they were coins from the ‘Crown Colony of Hong Kong’ and declared them legal tender.Footnote114 Local officials also took great care of advertisements. They produced promotional films for the public service slot of local television channels. Officials agreed in 1977 that the government should be ‘spending a great deal more on advertising’ and should stress that the coins were legal tender. Hong Kong and many other former territories of the British Empire relied on the Royal Mint to produce coins for both circulation and commemoration in this period. Sarah Stockwell has shown how, during the 1960s, the mint succeeded in securing the numismatic markets in various postcolonial states. Factors such as its determination to secure new markets in the Commonwealth, the legacy of the colonial networks, and its expertise in design facilitated this development.Footnote115 While Stockwell’s study focuses on African states, the mint’s domination of the numismatic markets also applied to Hong Kong in the 1970s. The Hong Kong government cooperated and sometimes relied on the mints to promote and sell its Lunar New Year coins.

At the same time, the British government monitored coin issues in its dependent territories. Gold coins had always been highly emblematic in the history of British coinage. They were called the ‘gold sovereign’, in which the head of the monarch appeared on the designs. The gold sovereign had been a symbol of British national identity from the nineteenth century onwards.Footnote116 A policy statement of the FCO in 1978 stressed that these coins also mattered globally. Collectors around the world focused primarily on ancient, medieval, and rare modern coins before the mid-1960s. However, they had become greatly interested in new gold coins due to their high standard of production. The FCO stated that investors had also paid greater attention to ‘coins with high intrinsic value’, and ‘the demand for coins by collectors’ had ‘increased enormously’ as a result.Footnote117 The British government thus intervened in coinage matters in dependent territories, including Hong Kong. For instance, in 1978 the FCO learned that numismatic coins produced by dependent territories were of questionable legality and were not backed by adequate assets. It therefore commissioned the Bank of England to recommend how the FCO could involve itself more in the coinage matters of the territories. This inquiry was also aimed to protect the royal imagery, as the FCO hoped to prevent collectors from associating the Queen’s head, which had to appear in the designs, with problematic coins.Footnote118

In fact, earlier in 1975 the mint had already proposed to the Hong Kong government that the Lunar New Year coins should be ‘expected to have great appeal among collectors in all parts of the world and … be a source of useful publicity’.Footnote119 The Royal Mint persisted in continuing the coin issues even though they were not as popular as officials had expected in the first few years. Instead, the mint promoted the coins even more aggressively by asking branches of the Hongkong Shanghai Banking Corporation (commonly known as HSBC) in the United States to allow owners to redeem the coins. It also sold the coins as jewellery and promoted their ‘investment potential’.Footnote120 The Hong Kong government and the mint once considered stopping the coin series or producing coins with reduced ‘fineness’ due to the increasing price of gold. However, Hong Kong’s Secretary of Monetary Affairs Douglas Blye reminded the mint that they had promised to produce a complete series of twelve coins, and that breaking this promise would harm the image of both the mint and the government.Footnote121 The mint thus chose not to abandon this project. In fact, Hong Kong officials always reported that the coins were in huge demand among the local population. In 1978 the horse coins were sold out within a short period of time.Footnote122 In 1979 they were so popular that local officials suggested allocating more coins to the Hong Kong market.Footnote123 Later in 1981, the Hong Kong government reported that the popularity of the coins persisted in the colony.Footnote124

Officials attempted to make traditional elements on the coins understandable to people overseas, including the animals and the messages they implied. Promotional brochures introduced the traditional Chinese calendar and the twelve animals in the lunar cycle. Officials also tried to introduce Lunar New Year customs to foreigners. For instance, the 1977 brochure used the qualities of ‘snake people’ in traditional Chinese culture as the selling point: ‘Those born in the Year of the Snake, according to Chinese, are attractive and wise’. It also related this traditional festival to Western civilisation: ‘Jacqueline Onassis and Princess Grace of Monaco were both born in the Year of Snake as were Picasso, Gandhi, Flaubert, Brahms, Darwin and Abraham Lincoln’.Footnote125 An advertisement in the American state of Iowa emphasised that ‘the snake is the guardian of treasure, and thousands of types are to be found in Chinese literature’. It also stressed that people born in the Year of the Snake could get along with those born in the years of ox and cockerel.Footnote126

While this was a promotional tactic to boost sales, it was also the Hong Kong government’s attempt to show how it cared about its traditional Chinese culture. Even though foreigners might not buy these coins, readers of the leaflets would still be reminded that Hong Kong was a Chinese city under British rule. Hong Kong officials decided what should appear on these promotional materials. Texts on the brochures were prepared every year by Hong Kong officials.Footnote127 Local officials also provided information related to traditional Chinese customs and animals of the year to the Royal Mint. In 1977 they provided information on how to promote horse coins. They suggested the mint to mention that people born in the Years of the Horse were ‘self-sufficient and independent, well-liked and much admired’.Footnote128 The finalised advertisement not only promoted these merits of the horse people, but also how horses appeared in traditional Chinese culture, such as art, tales, and worship.Footnote129

Two years later, when officials were promoting coins for the coming Year of the Monkey, the brochure also stressed that the monkey appearing on the coin was the one ‘commonly found in Hong Kong and China’. As in previous years, the brochures introduced to foreign audiences how monkeys appeared in traditional Chinese culture. For instance, how the Monkey God was worshipped by Buddhists and Taoists in Hong Kong and how monkeys, such as the Monkey King from the classic novel Journey to the West, had been ‘a source of fascination to the Chinese for many centuries’.Footnote130 However, officials would eliminate from the advertisement all elements associated with communist China. For instance, ‘Mao Tse-tung [Mao Zedong]’ was deleted from the draft list of famous historical figures.Footnote131 Other overseas promotional booklets, such as those in Britain and America, also required Hong Kong’s approval.Footnote132 Local officials strove to ensure that the mint would properly spread the colony’s image as a traditional Chinese city. In 1980, for example, Hong Kong warned the mint that the draft information leaflet was ‘subject to amendment’. In 1981 officials from the mint re-stated that they had to seek permission from the Hong Kong side before publishing the leaflet.Footnote133

The Royal Mint promoted these coins worldwide after receiving information from Hong Kong. English-speaking countries were not the mint’s only targets: it also advertised the coins in European newspapers and magazines.Footnote134 In 1981 it introduced the coins into the Southeast Asian market.Footnote135 At the same time, the mint promoted the coins through television advertisements featuring Chinese traditions. It cooperated with the Hong Kong Tourist Association, a semi-official organisation, to produce posters and films selling the coins in the United Kingdom and the United States. For instance, in 1978 the association found a Chinese woman to hold the coin in the photo.Footnote136 The mint later hoped to promote the coins in Chinese television stations in the United States, and specifically found ‘someone of Chinese ethnic origin from the Hong Kong Trade Office’ as the background narrator.Footnote137 In other words, Hong Kong, through agents such as the mint and the tourist association, promoted itself as a traditional Chinese city. Even though the audience of the promotion might not buy the coins, they would receive the messages about Chinese traditions in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong officials also strove to incorporate images that conformed with traditional Chinese standards on coin designs, even if they had to contact officials from the PRC. In 1977 officials believed the image of the Gansu Horse, an iconic creature in traditional Chinese culture, would make the coin more attractive. As the image came from a painting in the PRC, they decided to seek Beijing’s approval before putting it on the coins. They did so through the Political Adviser office and the New Chinese News Agency, the de facto embassy of the PRC in Hong Kong.Footnote138 In an era when the British and Hong Kong governments had an uncertain relationship with the PRC, this action was unprecedented. On the one hand, Hong Kong officials endeavoured to show that they understood the people’s culture. On the other hand, they showed to the mainland Chinese government that the colonial administrators had managed Hong Kong’s Chinese people well by taking care of their traditional customs. The PRC’s State Museums and Archaeological Data Bureau later approved Hong Kong’s request. It also thanked the Hong Kong government for choosing the ‘bronze speeding horse with its hind hoof treading on the flying swallow’ as the ‘effigy of the coin’.Footnote139 Governor Murray MacLehose later planned to present a set of Lunar New Year coins to the Chinese Premier when he visited Beijing in 1979.Footnote140 Again, archival records do not reveal why MacLehose did so. Considering the strategy he proposed in the early 1970s, nevertheless, his aim could be to show to mainland Chinese officials that his government had managed its people well, thus hoping to make them ‘hesitate’ before raising the issue of Hong Kong.

Conclusion

Pigs and rats might not win people’s affection as pets, but they did when officials put them on postage stamps and coins. By producing and selling objects that showcased Chinese festivals and customs, colonial officials attempted to demonstrate how they cared about local culture. This was an effort to secure trust. While other reforms in this era aimed to collect and respond to people’s voices, this cultural policy turned their voices and preferences into tangible everyday products. Even though not all members of society would actually purchase the stamps and coins, they could still sense the official efforts through advertisements around them. By cooperating and negotiating with the FCO and other British agencies, the Hong Kong government strove to continue these cultural efforts. It hoped to demonstrate to people both inside and outside the colony that it protected local culture well. For the Royal Mint and the Crown Agents, these cultural products might be more about profits. For colonial officials, however, this was part of their cultural policies from the 1960s on. By preserving and promoting traditional Chinese culture, they attempted to showcase their ‘imagination and sensibility to what appeals to Hong Kong people’. In MacLehose’s planning, this was an attempt to secure public trust and preserve British interests in the upcoming Anglo-Chinese negotiation over Hong Kong.

This is also a story of objects and colonialism that differs from the grand narratives of imperial superiority or exoticising the Other. Archival evidence reveals that, at least in Hong Kong, instead of creating European meanings to indigenous objects, colonial administrators created objects that conformed with local traditions and customs. Instead of spreading metropolitan culture, colonial administrators promoted peripheral culture. To gain people’s trust, they presented images that conformed with Chinese traditions, even though the images provoked minor quarrels between London and Hong Kong. The objects examined in this article were also not simply for display: they had monetary value and were circulated among the public. Though existing records may not fully reveal how successful this policy was, newspaper reports and various sales statistics still show that many local Chinese accepted and bought the objects.

Embracing Chinese culture with objects became Hong Kong’s annual tradition thereafter. The colonial government continued to issue Lunar New Year coins until the late 1980s, and private coinage companies took up this job afterwards. Meanwhile, postage stamps that featured Chinese culture never faded away in Hong Kong. Festivals, musical instruments, vessels, and many other items in Chinese traditions became the themes of commemorative stamps in the 1980s and 1990s. Hong Kong’s postcolonial Post Office (and perhaps also the collectors) has never got bored with Chinese culture. In an age when correspondence and greetings do not require postage stamps to embark upon their journeys, these miniatures are still being produced and sold in great numbers. Following the ‘tradition’ established in the late 1960s, the postcolonial Hong Kong government continues to sell brand new postage stamps to commemorate the Lunar New Year. Officials also utilise them to embrace Chinese culture and history. Chinese heritage, calligraphy, heroes, and so on take turn to occupy a space on the miniature. Even the COVID-19 crisis cannot deter Hong Kong officials from embracing Chinese culture: they have already issued five sets of stamps for this purpose during the first half of the turbulent 2020.Footnote141

Acknowledgments

I am most grateful to John Carroll for his critical and insightful comments on the earlier drafts of this article. My thanks also go to Reed Chervin, Peter Cunich, Esther Lau, Florence Mok, Carol Tsang, and the members of the 11 Harvey Road community in Cambridge in 2020-21 (Alisha Flaherty, Nathanael Lai, Beatrice Robson, Tan Chee Yong, and Seetha Tan). Their suggestions and support have made this article possible. I would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and the participants of my World History Workshop presentation at Cambridge for their constructive and encouraging feedback. Special thanks to the Postmaster General of Hong Kong for allowing me to reproduce the stamp images. Part of this research was completed during my MPhil study at the University of Hong Kong. It was supported by the university’s Postgraduate Scholarship and its travel grant. All errors remain my responsibility.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Secretary of State to Governor Hong Kong, 13 August 1970, Hong Kong Record Series (HKRS) 1082-1-3, Public Records Office (PRO), Hong Kong.

2 Governor Hong Kong to Secretary of State, 18 August 1970, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

3 Secretary of State to Governor Hong Kong, 18 August 1970, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

4 Folwell to Hon. Colonial Secretary, 24 August 1970, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

5 For instance, see Mok, “Public Opinion Polls,” 66–87; Yep, “The Crusade Against Corruption,” 197–221; Yep and Lui, “Revisiting the Golden Era,” 249–72.

6 Kowloon Disturbances, 127–28.

7 The 1966 Riots and the resulted Commission of Inquiry made colonial officials realise that there were no effective communication channels between the government and the public. The 1967 Riots reinforced this view among senior civil service. These officials accepted that they had to reform to legitimise the colonial government’s authority in Hong Kong; see Scott, “Bridging the Gap,” 139–41.

8 Tsang, A Modern History, 211–2.

9 Mark, “Development Without Decolonisation,” 332–3; Mark, The Everyday Cold War, 185–7.

10 MacLehose to Wilford, 27 October 1971, Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) 40/331, The National Archives (TNA), Kew, Surrey, UK.

11 Laird to Wilford, Monson, Logan, and Graham, 15 May 1972, FCO 40/391, TNA.

12 Cheung, “The 1967 riots,” 72–3.

13 Mark, “The ‘Problem of People’,”, 1145–81; Mok, “Chinese Illicit Immigration,” 340–7.

14 Tsang, A Modern History, 181; Ku, “Immigration Policies,” 351.

15 Luk, “Chinese Culture,” 667–8.

16 During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards destroyed national relics and attacked people adhering to customs; see MacFarquhar and Schoenhals, Mao’s Last Revolution, 118–22.

17 “Chen Dawen fangtanlu” [A Record of Interview with Darwin Chen], 254–5; “Zhongqiu caidenghui xianci” [A Speech for the Mid-Autumn Lantern Festival], Wah Kiu Yat Po, 29 September 1974, 3.2; “Huang Menghua Zhang Youxing” [Denny Huang and Hilton Cheong-Leen], Kung Sheung Daily News, 22 October 1970, 5.

18 Sweeting and Vickers, “Language and the History,” 28–9.

19 Carroll, A Concise History, 170.

20 Louie, “Defining Modern Chinese Culture,” 7–19.

21 For instance, see General Assessment on Local Celebration (urban) Events, December 1973, HKRS 489-7-23, PRO; Barnes to Director of Urban Services and Secretary for the New Territories, 16 January 1978, HKRS 410-4-9.

22 Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms, 76.

23 For instance, see Brown, “Trophies of Empire,” 40–83; Mirzoeff, “Photography at the Heart,” 167–87; Flynn, “Taming the Tusk,” 188–205; and Jasanoff, “Collectors of Empire,” 109–35.

24 For instance, see Lee, “Tourism and Taste Cultures,” 267–81; Batkin, “Tourism Is Overrated,” 282–98; and Furlough, “Une Leçon des Choses,” 457.

25 Washbrook, “Orients and Occidents,” 603.

26 Examples include Harper, The End of Empire, 274–307 and Ritter, Imperial Encore.

27 For instance, Frank Dikötter describes postage stamps in early twentieth century China as democratising the traditional way of collecting objects. Unlike antiques, stamps were “accessible” to ordinary people who wished to be collectors; Dikötter, Things Modern, 70.

28 Scott, European Stamp Design; Reid, “Symbolism of Postage Stamps,” 224–6.

29 For instance, see Hussain, “Symbolism and the State,” 17–40; Fallon, “Imperial Symbolism,” 119–31; Marten and Kula, “Meanings of Money,” 183–98; Eagleton, “Designing Change,” 222–44; also mentioned in Stockwell, The British End, 192.

30 Jeffery, “Crown, Communication,” 56–61.

31 For instance, see Vickers, Search of an Identity, 71–4; Wear, “The Sense of Things,” 173–204; and Abbas, Hong Kong, 63–70.

32 “Restricted: Philately,” enclosed in Bridger to Farrell, 14 April 1978, FCO 40/916, TNA.

33 Saving Despatch: Postage Stamps, 15 April 1971, HKRS 313-7-1, PRO; Farrell to Lohse, 22 March 1978, FCO 40/916, TNA.

34 Ponko, “History and the Methodology,” 43.

35 Folwell to Hon. Colonial Secretary, 14 December 1970, HKRS 313-7-1, PRO; Jenney to Postmaster General, 12 January 1971, HKRS 313-7-1, PRO; Palmer to Hon. Colonial Secretary, 14 January 1971, HKRS 313-7-1, PRO.

36 “Restricted: Philately,” enclosed in Bridger to Farrell, 14 April 1978, FCO 40/916, TNA.

37 Memorandum for Executive Council: New Postage Stamps, 7 April 1967, HKRS 313-7-1, PRO.

38 MacLehose to Fung, 10 April 1972, HKRS 313-7-1, PRO; Secretary of State to Governor Hong Kong, 13 August 1970, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

39 Circular Saving Despatch No: 35/71, 8 June 1971, HKRS 313-7-1

40 Ding, “Huaqiao ribao,” 243-44.

41 Crown Agents to Postmaster General, 17 September 1965, HKRS 2176-1-24, PRO.

42 McDouall to Crook, 4 October 1965, HKRS 2176-1-24, PRO.

43 “Hongkong Stamps,” South China Morning Post, 6 November 1965, 12.

44 Folwell to Crown Agents, 21 May 1966, HKRS 2176-1-24, PRO.

45 Folwell to Crown Agents, 17 November 1966, HKRS 2176-1-24, PRO.

46 “Public Rushes New Year Stamp Issue,” South China Morning Post, 18 January 1967, 6.

47 Crook to Hon. Colonial Secretary, 1 February 1967, HKRS 313-7-1, PRO.

48 Crowley to Crown Agents, 15 May 1968, HKRS 2176-1-14, PRO; Statement of Sales by the Crown Agents from Release 1.12.66 to Withdrawal 28.2.67, 25 May 1967, HKRS 2176-1-14, PRO; Statement of Sales by the Crown Agents from Release 24th April 1968 to Withdrawal 23rd July 1968, 25 November 1968, HKRS 2176-1-16, PRO.

49 Governor to Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs, 6 April 1967, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

50 Taylor to Crown Agents, 19 May 1967, HKRS 2176-1-25, PRO.

51 Taylor to Secretary for Chinese Affairs, 8 November 1968, HKRS 2176-1-27, PRO.

52 Tsang, Governing Hong Kong, 87; Hayes, Friends and Teachers, 87.

53 Meyer, “Feng-Shui,” 149–50.

54 For instance, retired officer James Hayes recalls that the government encountered obstacles when he negotiated with villagers over the construction of the Shek Pik reservoir, in which the villagers perceived it as violating various geomantic principles; see Hayes, Friends and Teachers, 34, 35–6, 44–5.

55 Chan to Postmaster General, 16 February 1971, HKRS 2176-1-27, PRO.

56 Wong to Taylor, 9 April 1973, HKRS 2176-1-32, PRO.

57 Wong to Taylor, 5 March 1974, HKRS 2176-1-33, PRO.

58 Wong to Taylor, 25 April 1975, HKRS 2176-1-34, PRO.

59 Wong to Taylor, 19 May 1976, HKRS 2176-1-35, PRO.

60 Dickson to Wong, 30 July 1976, HKRS 2176-1-35, PRO.

61 Memorandum for Executive Council: New Postage Stamps, 16 August 1968, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

62 Chan to Postmaster General, 18 November 1968, HKRS 2176-1-27, PRO.

63 Chan to Postmaster General, 26 November 1968, HKRS 2176-1-27, PRO.

64 Chan to Postmaster General, 11 November 1971, HKRS 2176-1-28, PRO.

65 Chan to Postmaster General, 4 November 1971, HKRS 2176-1-30, PRO.

66 Leung to Postmaster General, 17 August 1972, HKRS 2176-1-31, PRO.

67 Wong to Taylor, 5 March 1974, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

68 Memorandum for Executive Council: Postage Stamp Issue for Lunar New Year 1974, 7 February 1974, HKRS 2176-1-31, PRO.

69 Memorandum for Executive Council: Special Postage Stamps for Lunar New Year 1971, 10 August 1970, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO; Webb to Wong, 9 March 1970, HKRS 2176-1-28, PRO; Folwell to Hon. Colonial Secretary, 24 August 1970, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

70 Governor to Secretary of State, 18 August 1970, HKRS 2176-1-28, PRO.

71 Tozer, “Taiwan’s ‘Cultural Renaissance’,” 85.

72 Roberts, “Cold War Hong Kong,”42-6.

73 Folwell to Hon. Colonial Secretary, 24 August 1970, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

74 Steve Tsang, A Modern History, 190.

75 Chan to Postmaster General, 16 February 1971, HKRS 1082-1-3, PRO.

76 Yep and Lui, “Revisting the Golden Era,” 258–65.

77 “Special Stamps Running out,” Standard, 3 February 1968.

78 Taylor to Crown Agents H. Division, 6 March 1968, HKRS 2176-1-25, PRO.

79 Mak to S. C. P. (T), 13 February 1969, HKRS 2176-1-26, PRO.

80 “F. D. C. only,” n.d., HKRS 2176-1-28, PRO.

81 Hayball to Postmaster General, 10 May 1968, HKRS 2176-1-25, PRO; Collins to Postmaster General, 21 April 1970, HKRS 2176-1-27, PRO; Jones to General Post Office, 11 October 1971, HKRS 2176-1-28, PRO.

82 Folwell to Hon. Colonial Secretary, 15 February 1971, HKRS 1082-1-2, PRO; Mathews to Postmaster General, 7 April 1971, HKRS 1082-1-2, PRO.

83 Memorandum for Executive Council: Hong Kong Week, 9 July 1968, HKRS 489-7-22, PRO.

84 Whitley to Postmaster General, 3 December 1970, HKRS 2176-1-49, PRO.

85 Kan, “Festival Commemorative Stamps,” 16 September 2009, Oral History Interview, Hong Kong Memory Project.

86 Press Release, attached in Postmaster General to Director of Information Service, 14 October 1971, HKRS 2176-1-49, PRO.

87 Taylor to Crown Agents, 30 January 1973, HKRS 2176-1-54, PRO.

88 Kan, “Festival Commemorative Stamps.”

89 Postmaster General to Director of Information Service, 18 August 1973, HKRS 2176-1-54, PRO.

90 Addi to Chan, 30 November 1971, HKRS 313-7-1, PRO.

91 Chan to Addi, 12 January 1972, HKRS 2176-1-50, PRO.

92 Addi to Hon. Colonial Secretary, 21 January 1972, HKRS 2176-1-50, PRO; Jenney to Addi February 1972, HKRS 2176-1-50, PRO.

93 Jenney to Postmaster General, 10 May 1972, HKRS 2176-1-50, PRO.

94 Jenney to Postmaster General, 3 February 1972, HKRS 2176-1-50, PRO.

95 Wong to Taylor, 30 July 1973, HKRS 2176-1-55, PRO.

96 Davies to Postmaster General, 15 January 1976, HKRS 2176-1-64, PRO.

97 Taylor to Crown Agents, 26 January 1976, HKRS 2176-1-64, PRO.

98 Taylor to Crown Agents, 12 March 1976, HKRS 2176-1-64, PRO.

99 Hookham to Addi, 24 January 1973, HKRS 2176-1-52, PRO; Hookam to Bellenden, 19 December 1972, HKRS 2176-1-52, PRO.

100 “Wording for Commemorative Stamps stickers,” attached in Postmaster General to Wong, 25 May 1973, HKRS 2176-1-52, PRO.

101 “Arts Festival Stamps,” South China Morning Post, 6 February 1974, 4.

102 Wong to Postmaster General, 11 March 1974, HKRS 2176-1-57, PRO.

103 “Stamp Story: Festival of Moon Cakes,” South China Sunday Post, 11 April 1976, 5.

104 Tam to Secretary for New Territories Administration, 11 July 1978, HKRS 2176-1-72, PRO.

105 “Special Stamp Issue 1980,” attached in Taylor to Crown Agents, 11 March 1980, HKRS 2176-1-72, PRO.

106 “MOOD: Preservation of old buildings (2,500 respondents); Anti-rabies campaign (1,7000 respondents),” 5 December 1977, HKRS 410-4-9, PRO; Barnes to Director of Urban Services and Secretary for the New Territories, 16 January 1978, HKRS 410-4-9, PRO.

107 Luk to So, 24 April 1974, HKRS 2176-1-13, PRO.

108 Choy to Postmaster General, 20 May 1974, HKRS 2176-1-13, PRO.

109 Luk to Choy, 24 May 1974, HKRS 2176-1-13, PRO.

110 “Benevolent Linguistic Despotism,” South China Modern Post, 16 May 1983, 23.

111 Hart to Sewell, 13 October 1977, Royal Mint (MINT) 34/SR/Z, TNA.

112 MacLehose to FCO, 13 December 1974, FCO 40/520, TNA.

113 “1977 is the Year of the Snake,” leaflet, 1977, MINT 34/S4/Z, TNA.

114 “The Year of the Dragon,” 1976, MINT 34/SV/Z, TNA; “Xianggang jinian jinbi” [Hong Kong commemorative coins], leaflet, 1977, MINT 34/S4/Z, TNA.

115 Stockwell, The British End, 191–228.

116 Daunton, “Britain and Globalisation,” 24.

117 “Numismatic Coin Issues,” 26 January 1978, FCO 40/969, TNA.

118 Ibid.

119 Paper by the Royal Mint, attached in Dowling to Douglas, 12 June 1975, MINT 34/TB/Z, TNA.

120 Emden to Dowling, 17 May 1977, MINT 34/S4/Z, TNA.

121 Blye to Hart, 12 February 1979, MINT 34/TH/Z, TNA.

122 “HK $1000 Gold Coin: Sold Out in Hong Kong,” press release, 1978, MINT 34/SV/Z, TNA.

123 Hart to Lotherington, Mansley, Cox, Jones, and Cragg, 26 January 1979, MINT 34/TH/Z, TNA.

124 Note on Meeting with Mr. D. W. A. Blye, 20 July 1981, MINT 34/TL/Z, TNA.

125 “1977 is the Year of the Snake,” brochure, 1977, MINT 34/S4/Z, TNA.

126 “Hong Kong $1,000 Gold Coin Heralds Year of the Snake,” 28 December 1976, MINT 34/S4/Z, TNA.

127 Note of a Meeting with Mr. Douglas Blye, 10 August 1979, MINT 34/S7/Z, TNA.

128 Emden to Edge, 4 August 1977, MINT 34/ST/Z, TNA.

129 Year of the Horse Order Form, 1978, MINT 34/ST/Z, TNA; “British Royal Mint Announces Hong Kong Year of the Horse HK $1000 Gold Coin,” 6 January 1978, MINT 34/SV/Z, TNA.

130 “Hong Kong HK$1000 Gold Coin,” 18 October 1979, MINT 34/S7/Z, TNA; “Hong Kong $1000 Lunar Year Coin,” 1980, MINT 34/TB/Z, TNA.

131 “Do you have a snake in your family,” draft brochure, 31 December 1976, MINT 34/S4/Z, TNA.

132 Hart to Mansley, n.d., MINT 34/S7/Z, TNA.

133 Hart to Mansley, 27 August 1980, MINT 34/TK/Z, TNA; Hart to Bendon, 28 July 1981, MINT 34/TL/Z, TNA.

134 “1977 is the Year of the Snake,” leaflet, January 1977, MINT 34/S4/Z, TNA; “Ein exclusives Angebot für Sammler und Geldanleger” [An Exclusive Offer for Collectors and Investors], 24 June 1977, MINT 34/S4/Z, TNA; “Un dragon d’or pour Hong Kong” [A Golden Dragon for Hong Kong], n.d., MINT 34/S4/Z, TNA.

135 Lotherington to Blye, 18 February 1981, MINT 34/TK/Z, TNA.

136 Woodman to Emden, 5 January 1978, MINT 34/SV/Z, TNA; Woodman to Dunt, 6 January 1978, MINT 34/SV/Z, TNA.

137 Emden to Jones, 6 February 1978, MINT 34/SV/Z, TNA.

138 Wilson to Masefield, 7 January 1978, FCO 40/969, TNA.

139 Wang to Wilson, 28 January 1978, FCO 40/969, TNA.

140 Note of a Visit to the Colonial Secretariat, Hong Kong, 19 March 1979, MINT 34/TH/Z, TNA.

141 Hong Kong Post Stamps, “2020 Stamps Issuing Programme,” accessed 30 July 2020, Hong Kong Post Stamps. https://stamps.hongkongpost.hk/stamp/detail/2477b1c4-3b0c-4ef3-a288-ce92e3e72ebc.

References

- Abbas, Ackbar. Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1997.

- Batkin, Jonathan. “Tourism Is Overrated: Pueblo Pottery and the Early Curio Trade, 1880–1910.” In Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, edited by Ruth B. Phillips, and Christopher B. Steiner, 282–98. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Brown, David Blayney. “Trophies of Empire.” In Artist and Empire: Facing Britain's Imperial Past, edited by Allison Smith, 40–83. London: Tate Publishing, 2015.

- Carroll, John M. A Concise History of Hong Kong. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2007.

- Cheung, Gray Ka-wai. “How the 1967 Riots Changed Hong Kong’s Political Landscape, with the Repercussions Still Felt Today.” In Civil Unrest and Governance in Hong Kong: Law and Order from Historical and Cultural Perspectives, edited by Michael H. K. Ng, and John D. Wong, 63–75. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Cohn, Bernard S. Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Daunton, Martin. “Britain and Globalisation Since 1850: I. Creating a Global Order, 1850–1914.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 16 (2006): 1–38. doi: 10.1017/S0080440106000405

- Dikötter, Frank. Things Modern: Material Culture and Everyday Life in China. London: Hurst & Company, 2007.

- Ding, Jie. “Huaqiao ribao” yu Xianggang Huaren shehui – 1925–1995 [The Wah Kiu Yat Po and Hong Kong Chinese Society – 1925–1995]. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 2014.

- Eagleton, Catherine. “Designing Change: Coins and the Creation of New National Identities.” In Cultures of Decolonisation: Transnational Productions and Practices, 1945–70, edited by Ruth Craggs, and Claire Wintle, 222–44. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016.

- Fallon, Hugh C. “Imperial Symbolism on Two Carolingian Coins.” Museum Notes (American Numismatic Society) 8 (1958): 119–31.

- Flynn, Tom. “Taming the Tusk: The Revival of Chryselephantine Sculpture in Belgium During the 1890s.” In Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, edited by Tim Barringer, and Tom Flynn, 188–204. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Series 40. The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, United Kingdom.

- Furlough, Ellen. “Une Leçon des Choses: Tourism, Empire, and the Nation in Interwar France.” French Historical Studies 25, no. 3 (2002): 441–73. doi: 10.1215/00161071-25-3-441

- Harper, T. N. The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Hayes, James. Friends and Teachers: Hong Kong and Its People, 1953–87. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1996.

- Hong Kong Post Stamps. 2020. Stamps Issuing Programme and Introduction.” Hong Kong Post Stamps. Accessed 30 July 2020. https://stamps.hongkongpost.hk/stamp/detail/2477b1c4-3b0c-4ef3-a288-ce92e3e72ebc.

- Hong Kong Record Series 313, 410, 489, 1082, and 2176. Public Records Office, Government Records Service, Hong Kong.

- Hussain, Syed Ejaz. “Symbolism and the State Authority: Reflections from the Art on Indo-Islamic Coins.” Indian Historical Review 40, no. 1 (2013): 17–40. doi: 10.1177/0376983613475863

- Jasanoff, Maya. “Collectors of Empire: Objects, Conquests and Imperial Self-Fashioning.” Past & Present 184 (2004): 109–35. doi: 10.1093/past/184.1.109

- Jeffery, Keith. “Crown, Communication and the Colonial Post: Stamps, the Monarchy and the British Empire.” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 34, no. 1 (2006): 45–70. doi: 10.1080/03086530500411290

- Kan, Tai Keung. “The Design of the Festival Commemorative Stamps.” 16 September 2009. TW-KTK-LIFE-011, Oral History Interview, Hong Kong Memory Project.

- Kowloon Disturbances 1966: Report of Commission of Inquiry. Hong Kong: Government Printer, 1967.

- Ku, Agnes S. “Immigration Policies, Discourses, and the Politics of Local Belonging in Hong Kong (1950–1980).” Modern China 30, no. 3 (2004): 326–60. doi: 10.1177/0097700404264506

- Kung Sheung Daily News. 1970.

- Lai, Victor and Eva Man Kit-Wah, eds. Yu Xianggang yishu duihua 1980–2014 [Dialogues with Hong Kong Arts 1980–2014]. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 2015.

- Lee, Molly. “Tourism and Taste Cultures: Collecting Native Art in Alaska at the Turn of the Twentieth Century.” In Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, edited by Ruth B. Phillips, and Christopher B. Steiner, 267–81. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Louie, Kam. “Defining Modern Chinese Culture.” In The Cambridge Companion to Modern Chinese Culture, edited by Kam Louie, 1–19. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Luk, Bernard Hung-Kay. “Chinese Culture in the Hong Kong Curriculum: Heritage and Colonialism.” Comparative Education Review 35, no. 4 (1991): 650–68. doi: 10.1086/447068

- MacFarquhar, Roderick, and Michael Schoenhals. Mao’s Last Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006.

- Mark, Chi-kwan. The Everyday Cold War: Britain and China, 1950–1972. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- Mark, Chi-kwan. “The ‘Problem of People’: British Colonials, Cold War Powers, and the Chinese Refugees in Hong Kong, 1949–62.” Modern Asian Studies 41, no. 6 (2007): 1145–81. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X06002666

- Marten, Lutz, and Nancy C. Kula. “Meanings of Money: National Identity and the Semantics of Currency in Zambia and Tanzania.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 20, no. 2 (2009): 183–98. doi: 10.1080/13696810802522361

- Meyer, Jeffrey F. “‘Feng-Shui’ of the Chinese City.” History of Religions 18, no. 2 (1978): 138–55. doi: 10.1086/462811

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. “Photography at the Heart of Darkness: Herbert Lang’s Congo Photographs (1909–15).” In Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, edited by Tim Barringer, and Tom Flynn, 167–87. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Mok, Florence. “Chinese Illicit Immigration into Colonial Hong Kong, c. 1970–1980.” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 49, no. 2 (2021): 339–67. doi: 10.1080/03086534.2020.1848402

- Mok, Florence. “Public Opinion Pools and Convert Colonialism in British Hong Kong.” China Information 33, no. 1 (2019): 66–87. doi: 10.1177/0920203X18787431

- Ponko, Vincent, Jr. “History and the Methodology of Public Administration: The Case of the Crown Agents for the Colonies.” Public Administration Review (1967): 42–7. doi: 10.2307/973184

- Reid, Donald M. “The Symbolism of Postage Stamps: A Source for the Historian.” Journal of Contemporary History 19 (1984): 223–49. doi: 10.1177/002200948401900204

- Ritter, Caroline. Imperial Encore: The Cultural Project of the British Empire. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2021.

- Roberts, Priscilla. “Cold War Hong Kong: Juggling Opposing Forces and Identities.” In Hong Kong in the Cold War, edited by Priscilla Roberts, and John M. Carroll, 26–59. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2016.

- Royal Mint, Series 34. The National Archives, Kew, Surrey, United Kingdom.

- Scott, David. European Stamp Design: A Semiotic Approach to Design Messages. London: Academy Editions, 1995.

- Scott, Ian. “Bridging the Gap: Hong Kong Senior Civil Servants and the 1966 Riots.” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 45, no. 1 (2017): 131–48. doi: 10.1080/03086534.2016.1227030