ABSTRACT

Convict labourers in Bermuda formed part of a uniquely mixed workforce that challenged racial and class-based divisions of labour in the British Empire. Following the War of 1812, investment poured into Bermuda's royal naval dockyard to secure its strategic position; convicts arrived in 1824, working alongside enslaved people, free black workers, and colonial soldiers. This article reveals the nature of interactions between different types of free and unfree labourers in Bermuda between 1824 – when convicts arrived – and 1838, when a change in governance took place. It examines racial diversity in the dockyards and the arrival of convict labourers, before considering perceived threats of racial intermixing and opposition to convict labour deployment in Caribbean colonies. The final section examines perceptions of convicts – moments where they equated their experiences to slavery, and administrative unease over interactions with white military workers. What the article shows is that although there were concerns over racial intermixing, officials objected most strongly to interactions between white workers of different classes, fearing their alliances would alter the island's power balance. In detailing the coexistence and interactions between contrasting labour types, this article provides a greater sense of the nuances of labour deployment and administrative anxiety in colonial locales.

Introduction

Convict labourers arrived in Bermuda in 1824. Amongst the white sands, sparkling seas and blue skies they became part of a unique workforce on the island that challenged racial and class-based divisions of labour in the colonies, as they worked alongside enslaved and free black people, and colonial soldiers. Transporting convicts to Bermuda was an experiment – in 1822, facing ever-growing numbers in prisons, the Home Secretary Robert Peel advocated ‘a combination of hard labour and expatriation to some of the colonies, the Bermudas for instance, where public works were carrying on.’Footnote1 But Peel's proposals were not carried over to other British colonies. In the Caribbean, the idea of convicts working alongside enslaved people was met with opposition. William Burge, Agent for Jamaica and former Attorney-General, stated that the idea of transporting convicts there would ‘not only be very mischievous, but would be altogether impracticable,’ as Jamaica’s black population was far greater than in Bermuda.Footnote2 White inhabitants were vastly outnumbered, and Burge believed that if free and enslaved people witnessed ‘the degraded state of convicts’, the balance of society there would become unstable, as it was ‘held together by the mere influence of opinion’.Footnote3 Burge strongly believed that ‘the moral influence’ of convicts would have a negative effect on enslaved populations, and that islands such as Trinidad, by virtue of their small size, would find it ‘quite impossible to employ them at a distance from the slave population’.Footnote4 Bermuda was small, but there appeared to be less concern over racial intermixing; instead, correspondence reveals far greater objections to interactions between convicts and white workers, the various military regiments who laboured alongside them.

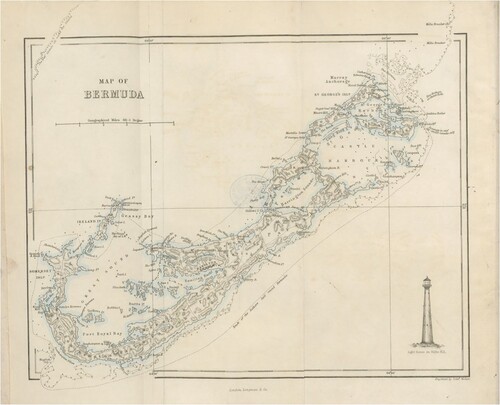

Only twenty miles long, Bermuda had been under British rule since the seventeenth century and was in close proximity to Atlantic sea lanes.Footnote5 shows a map of the island, with its primary dockyard and barracks situated on Ireland Island, at the northwesternmost point. Its location placed it ‘in the eye of all trade’, as nine out of every ten ships sailing between the Caribbean and Europe or North America passed the island.Footnote6 If the Caribbean was a region defined by lucrative markets and exported goods, Bermuda was the opposite. Its key purpose as a British overseas colony was strategic. The island is roughly 900 miles from the Caribbean, 800 from New York, and 870 from Halifax, Nova Scotia. By contrast, a British outpost like Jamaica is a little over 2,000 miles from Halifax, and over 1,500 from New York. With losses along America’s Eastern Seaboard after the Revolution and War of 1812, Bermuda’s role in supporting the British presence overseas became highly important. After the War of 1812, it was designated an imperial fortress; the strategic position of Bermuda, along with Halifax, Nova Scotia, Gibraltar and Malta, were heavily invested in as sites where Royal Naval squadrons had safe access to repairs, refilling, and military garrisons should there be the need for both local defence and amphibious campaigns.Footnote7

Figure 1. Map of Bermuda. Source: British Library Flickr, Ferdinand Whittingham, Bermuda, a colony, a fortress, and a prison; or, Eighteen months in the Somers’ Islands. (London: Longman, 1857).

Michael J. Jarvis’s work has profiled how Bermuda’s intensive maritime community capitalised on its position for trade; however, the significance of convict labour in the history of Bermuda’s maritime infrastructure remains overlooked.Footnote8 Clare Anderson asserts that convicts became part of a colonial labour repertoire in which they were deemed suitable for the purpose of imperial expansion.Footnote9 Convict labour became a central aspect of the development of Bermuda’s dockyards in the nineteenth century – their experiences are foregrounded in what follows. In detailing the coexistence and interactions between contrasting labour regimes, we gain a greater sense of the complexities and nuances of labour deployment in individual colonial locales.

At its heart, this article examines the interactions between, and discourses surrounding varied types of maritime worker in Bermuda. It examines more closely the nexus between colonialism, and three primary labour types: enslaved, convict, and military. The first section begins by unpacking the perceived need for labour on the island in the 1820s, before considering its labour force of free and enslaved workers, and the arrival of convicts. Virginia Bernhard contends that Bermuda’s shift from an agricultural economy to a maritime one transformed race relations, as free and enslaved black workers laboured alongside white men, forming relationships quite unlike other colonial societies.Footnote10 Convicts were in fact first landed in Bermuda in the seventeenth century, and it is likely some were sold to Bermudian owners in the eighteenth century.Footnote11 There were also other eighteenth-century precedents; as Ruth Pike outlines, the Spanish replaced enslaved labour employed in fortress construction in Puerto Rico with convicts because death rates among the former were unacceptably high.Footnote12 Convicts were seen as cheap and expendable compared with enslaved people, yet Ulbe Bosma has argued that high mortality rates amongst colonial soldiers and convicts deployed in empire-building ‘was just part of their lot’.Footnote13 Using convict labourers in the Australian colonies sidestepped the problems associated with deploying a largely white coerced labour force alongside enslaved African workers – this was not the case in Bermuda. This article looks at the dynamics of a mixed labour force and attitudes towards it, exposing the distinctions made between race and class.

Racial intermixing was more common in port cities; Pepijn Brandon, Niklas Frykman, and Pernille Røge’s collection on free and unfree labour in Atlantic and Indian Ocean has shown that port cities brought together labouring populations of different backgrounds and statuses – legally free or semi-free wage labourers, soldiers, sailors, and the self-employed, indentured servants, convicts, and enslaved people.Footnote14 The hubs of mixed labour in Bermuda were its dockyards – on Ireland Island and the town of St George’s. These were geographically removed from the small capital, Hamilton. Studies of urban port cities examine the consequences of the presence of mixed groups on and around the docks and neighbourhoods that stretched behind them.Footnote15 Brad Beaven has argued that the presence of people from many cultures in these waterfront districts created a kind of ‘international contact zone’ where seafarers of different nationalities came together in various forms of contact and exchange.Footnote16 Bermuda’s dockyards were spaces which provided an international contact zone for its maritime workers. However, the sites were ordered, and blending of work with leisure was unauthorised. The second section of this article examines security matters: local objections to convicts and settlement, alongside concerns over racial intermixing. We see that the dockyard became a space of contact and exchange where free black workers traded goods including food and alcohol with convicts.

This article contends that the decision to send convicts to Bermuda challenged racial divisions of labour that were not typically tolerated in other economies dependent on slavery. This was due to the maritime nature of labour in Bermuda, and the size of the colony. Jarvis’s work suggests that Bermuda, the first English colony to import African labour, developed a particular kind of maritime slavery.Footnote17 Until abolition, slavery underpinned every aspect of Bermuda’s maritime economy, from shipbuilding to buying and selling cargoes, to dockyard construction. Work by Ann Coats, Jarvis and James E. Smith has tended to focus on relationships between the enslaved and enslavers,Footnote18 but Bermuda also presents an opportunity to examine and bring together the interactions between the different labour regimes that supported colonial expansion.Footnote19 Scholars including Clare Anderson, Kay Saunders, David Northrup and Marcelo Badaró Mattos have all invited comparisons between convicts and coerced, indentured and free labourers across Empires.Footnote20 Military workers have generally been excluded from these labour types, yet Ulbe Bosma, Nick Mansfield and Megan C. Thomas argue they played a key role in colonisation; Bosma points out that ‘soldiers, and next to them convicts, were ideally suited to [sustain] imperial interests’, and were in a sense un-free.Footnote21 The final section explores the porosity of identities and boundaries between free and unfree labour. It taps into the long-standing debates around transportation rhetoric examined by Jane Lydon, Jennie Jeppeson, asking, how convicts saw themselves: as workers, or as enslaved?Footnote22 Administrative records reveal a degree of unease that convicts would morally corrupt white military workers; working alongside each other raised questions on how to maintain white male power in a colony where demographic balances were shifting.

Assessing the interactions between free, unfree, and enslaved workers in Bermuda presents an opportunity to examine not only the coexistence of different labour types, but also small human acts of resistance, exchange, and alliance. Furthermore, Bermuda’s maritime characteristics also help us build a larger picture that underlines the nuances of labour deployment in colonial locales – this emphasises the importance of avoiding viewing colonies within the British empire and elsewhere as homogenous. Before proceeding, it must be noted that this article does not equate the experience of convict transportation with that of slavery. Hamish Maxwell-Stewart writes that the two systems shared much in common, but an understanding of how plantation – and, in Bermuda’s case, maritime – slavery worked, and the forces which brought about its demise, can be helpful in exploring the manner in which similar processed played out in penal colonies.Footnote23 Additionally, a moment must be taken to reflect upon the anonymity of both the convicts and enslaved people caught up in imperial processes. The contemporary sources assessed here paid little attention to the lives, dignity and experiences of these marginalised groups.Footnote24 While what follows reflects upon the content and language used within these reports, the perspective through which this article views convicts and enslaved people is, inevitably ‘from above’. The biases and elisions of the state sources used here mask the intricacies and occurrences of brutality, coercion and survival under British colonial rule: that too, is part of the story told here.Footnote25

Maritime Infrastructure: Racial Diversity in Bermuda’s Dockyards

Most of Bermuda’s male enslaved population worked in maritime occupations. Mary Prince, born into slavery at Brackish Pond in Devonshire Parish, recounted in her memoir that her father was a sawyer enslaved by a ship-builder.Footnote26 Other enslaved men laboured in shipbuilding, as carpenters, joiners, caulkers, pilots and mariners, fishermen and wharf workers.Footnote27 Reliance on black maritime labour depended on locale and need.Footnote28 For Bermuda, the need to carry out public works in resulted in the army and navy accommodating local practices – the Admiralty purchased suitable land, and a military garrison was based in dockyards to protect the naval base. Island enslavers began to hire out their men to work for the military, which assumed the cost of feeding and housing them. Work began in earnest in 1809. Employed on the site at Ireland Island, at the North West of the island, were 74 English artificers, 54 Bermudian artificers, 164 labourers, and an unspecified number of enslaved men, hired from their Bermudian enslavers.Footnote29 By 1814, towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars and War of 1812, Bermuda Yard employed a workforce of 381, of whom 67 were established artificers and 107 were extra artificers. There were also 31 French prisoners and 176 labelled as ‘American refugee Negroes’ housed on the receiving ship, HMS Ruby.Footnote30 These figures show that prior to the arrival of convicts, the dockyard at Bermuda was a very mixed site; prisoners of war, and enslaved and free black men – from America and France, some captured at sea, others illegally trafficked – worked alongside British militiamen and engineers.Footnote31 By the time the first convict ship arrived in the 1820s, free and enslaved black Bermudians had been a part of the maritime workforce for over 100 years.Footnote32

As Bermuda’s dockyard complex was constructed on a grander scale, certain events prompted the British government’s decision to deploy convict workers in Bermuda. The first was the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which formally abolished the slave trade but not slavery itself.Footnote33 The lack of opportunity for emigration and an increase in Bermuda’s black population could have answered the perceived need for labour on the island.Footnote34 Indeed, on the subject of introducing free labour to the colonies, Lord Dudley stated that in Antigua, ‘very little profit or renumeration sufficed to induce men to labour in the most insalubrious situations, and at works which were obviously injurious to health.’Footnote35 However, as the scope of improvements in Bermuda’s dockyards continued to expand, both the local workforce and free labour migration were seen as not capable of meeting demand.Footnote36 In 1818, the royal naval dockyard officially became the British headquarters for the North America Station. But that year and 1819 saw a series of yellow fever epidemics, which took heavy tolls on British artificers and black employees, leading to an additional shortage of workers.Footnote37 Bermuda’s slow rate of development was criticised in parliament in 1821, as Clerk of Ordnance Robert Ward presented yearly estimates, stating that ‘some years ago there was a sum granted for the fortification of Bermuda […] indeed the fortifications were not yet finished’.Footnote38 Preferable to hiring small groups and individuals with varied skills from multiple sources was a mass deployment of workers. The move also had to be cost-effective, as the post-war years brought with them an economic depression prompting expenditure cuts across dockyards.Footnote39

In England, rising convict numbers and increased prison overcrowding was also prompted by the economic downturn. Cities coping with population booms saw crime rates rising sharply, with the most common crime being small-scale theft.Footnote40 In 1822, Home Secretary Robert Peel stated in the Commons that ‘something should be done with respect to transportation’.Footnote41 He suggested one scheme for Bermuda ‘which might lay the foundations of a new mode of punishment, free from many of the objections to the present system of transportation, and combining it with hard labour’.Footnote42 The Superintendent of convict hulks, John Henry Capper, sent quarterly reports to Peel, and stated in 1823 that dockyards sometimes suffered from a surplus of convict labourers. Capper noted that there was, in fact, not enough labour at Sheerness ‘for the constant employment of all the prisoners belonging to both ships stationed there’.Footnote43 He hoped that departures of a convict ship to New South Wales would thin out numbers but supply was outweighing demand as numbers continued to rise. Peel’s drive to deploy convicts in Bermuda also coincided with a supposed outbreak of scurvy in Millbank penitentiary.Footnote44 The Morning Chronicle published a report condemning administrators, accusing them of willingly allowing prisoners to die in order to save transportation costs.Footnote45 It stated that ‘the mind of the person, who contrived this prison [might have] been influenced by the diabolical idea of saving the expense of conveying convicts to distant settlements by a commutation that would put an end to all their earthly troubles’.Footnote46 The sick prisoners were removed from Millbank, an action which placed more pressure on overcrowded prison hulks.Footnote47

Peel’s Bermuda proposal was authorised by an Act of Parliament on 4 July 1823, and represented a new form of secondary punishment which could prove both profitable to the state and alleviate the pressure on hulks in England.Footnote48 The first convict ship, the Antelope, sailed on 6 January 1824. One month later, it was reported in the House of Commons that engineer Josias Jessop had ‘given a very favourable report of [Bermuda] as a station for shipping’.Footnote49 He estimated that the naval and ordnance works would take around thirteen to fourteen years to complete, but Member of Parliament Henry Bright argued that the public works were worth undertaking, as ‘in the event of war, the island might be easily taken [and so] it was very material that as soon as possible it should be put in a state of defence.’Footnote50 In fact, the public works at Bermuda continued for a period of over 40 years. During this time, seven hulks were put into use, averaging around 236 convicts per ship.Footnote51 With no barracks or prisons to house convicts on the island, it was decided that prison hulks would be moored up in the dockyards. Aside from the costs of maintaining them, convicts were a low-cost and mobile workforce. Bermuda was one of many attempts by the British government to deploy convict labour in its colonies; although the First Fleet of convicts sailed to New South Wales in 1787, this followed a series of ill-fated attempts to find suitable sites, including Africa, India and Madagascar.Footnote52 The Bermuda experiment, however, was not a settlement scheme, and solely focused on labour.

The demographic of convict workers on the hulks in Bermuda differed from those in England, as those selected for transportation were initially hand-picked for their age and strength. This was something which mirrored practice in the Australian colonies.Footnote53 Home Office petitions reveal that convicts were sentenced to seven years, fourteen years, or transportation for life for numerous offences. Both George Hutcheson, aged 38, convicted of house-breaking at Aberdeen, and William Wilkie, 20 years old, convicted of theft at Perth, received sentences of seven years’ transportation.Footnote54 Conversely, 23-year old George Davis received a life sentence at the Old Bailey for stealing a watch, and fellow prisoner, 17-year old John Nobley received the same sentence for stealing a handkerchief.Footnote55 Both had their sentences reduced to fourteen years on account of good conduct on board the Antelope. As well as their age and strength, prisoners were selected for their skills. One year after the Antelope arrived, the Commissioner of the dockyard Captain Thomas Briggs wrote to the Navy Board in London stating that a further 100 convicts could be sent from England, and suggested that ‘they should be selected from those who have served the trades therein specified: masons, house joiners, plumbers, painters, plasterers, horse shoeing smith and farrier [and] clockmaker – to attend repairs of yard clock’.Footnote56 In some register books, convicts’ former employment was noted down, so selecting skilled men for the next transports was a relatively simple process. While awaiting transportation on the hulks in England, men were put to work in the dockyards, so administrators could also ask overseers to recommend suitable men.

The first three hundred men sent out on board the Antelope were employed on the public works in the dockyard under the Naval Department.Footnote57 Numbers were relatively low in comparison to the 651 male convicts who had been sent to New South Wales and the 750 sent to Van Diemen’s Land the previous year, which reflected the experimental nature of the establishment in its early years.Footnote58 Setting up the convict establishment in Bermuda was expensive, but the product of convict labour was intended to offset the cost of transporting, victualling and clothing. In 1824, the expense in running the Antelope came to £7,065.6s.3d., around one thousand pounds more than that of the Justitia at Woolwich, and two thousand more than the Leviathan at Portsmouth, which came to £5,101.19s.10d.Footnote59 The value of convict labour would only offset costs if the system ran effectively. In 1824, Superintendent Capper remarked that a lack of attention to detail on the part of colonial officials explained why the establishment at Bermuda was so expensive.Footnote60 Colonel Davies, an outspoken critic of military expenditure, condemned management in the colonies, calling it ‘the most infamous system of jobbing on the face of the globe’.Footnote61 Capper’s insistence that the true value of convict labour in Bermuda had not yet been measured reflected his desire to justify initial outlays, but also suggested that his physical separation from the establishment as its Superintendent made the operation difficult to regulate. By 1828, the value of convict labour at home and overseas was estimated at £73,000, with Peel stating to the Commons ‘if there had been no convicts to do the work, the government must have paid that sum for labour done on public works’.Footnote62

In marked contrast to dockyards in England, labour was not racially segregated in Bermuda’s dockyards. Demographics on board the hulks themselves were equally diverse, as Bermuda was used as a reception site for non-white convicts sentenced in the Caribbean in the same way as it received British colloquially convicted soldiers. As early as February 1824, Major General Murray, the Governor of Demerara (now British Guiana) suggested transporting a group of rebel enslaved men who had caused a revolt in that colony to Bermuda. He felt it was dangerous to return the fifteen men to the properties where they were held in slavery, and hoped that they ‘might be removed to Bermuda, a climate congenial to them, and where they might be kept employed as convicts’.Footnote63 The idea that Bermuda could become a repository for convicts from Atlantic colonies was not something that administrators desired; by June 1826, it was requested that ‘every case of transportation to Bermuda from America and the West Indies […] must be notified to the Home Department before the convict can be received at Bermuda’.Footnote64 Attempts to legislate against this practice suggest that administrators were keen to racially segregate Bermudian hulk labour. However, it could more simply reflect concerns over capacity. As detailed in the third section, an influx of white ex-military prisoners from Canada in the 1830s was also met with opposition. All prisoners could petition for early release, but if their behaviour was in doubt, or crime judged too severe, they were not successful. For example, convict Samuel Smithson, tried of assault and mutiny in Demerara and held on board the Weymouth hulk, claimed that he was innocent and had family dependents, but his case was marked ‘nil’ by administrators.Footnote65 Convict hulks both at home and in Bermuda were homosocial environments, but in 1830, there two women – Maria Tinney, alias Kendrick, and Sophia Sancius – were transported to Bermuda from Demerara, although authorities agreed that this action was a mistake and sent them back.Footnote66

Advancing abolition and expansion of the public works prompted the British state to send more convicts to Bermuda. While shows that convict numbers peaked at 1302 in 1829, they were dwarfed by returns of enslaved people in Bermuda; these numbered 5176 in 1820, 4608 in 1827, 4371 in 1830 and 4203 in 1834.Footnote67 They tell of a slow decline (that was not related to deaths) and indicate that they were being sold by their enslavers in advance of abolition. This supported administrators’ views that the enslaved population of Bermuda was too small, and therefore convict workers were needed.Footnote68 In 1827, Bermuda’s Governor, Tomkyns Hilgrove Turner, commented that population had decreased since the census was taken in 1823 due to the removal of people after a change in trade laws. He stated that the enslaved population had decreased ‘in a great degree by the late exportation of a considerable number of slaves, for whom there was little or no employment here, to the West Indies on the license there to be sold.’Footnote69 Turner also assumed that the passing of the Slave Act, which went into operation on 1 January 1825 also accounted for decreased numbers.

Table 1. Numbers of convicts on hulks in Bermuda, 1820–1840.

shows a decline in convict numbers from 1834 onwards. This can be explained by Bermuda’s attitude to abolition: along with Antigua, Bermuda chose to opt out of the apprenticeship phase altogether, proceeding straight from slavery to free wage labour in 1834.Footnote70 The mainly maritime and domestic enslaved people on the island had virtually no alternative but to continue working for their former enslavers.Footnote71 This availability of labour may have influenced administrators’ decisions to reduce the convicts at Bermuda. However, when the Select Committee on Transportation interviewed former Commander of the Engineers Colonel Tylden in 1837, he was asked why Bermuda did not choose to employ free labourers on the public works. He replied that the convicts worked ‘much better’ than free black men.Footnote72

Objections: Settlement and Racial Intermixing

The British government found that the expense of sending convicts to New South Wales engendered small losses. Robert Peel suggested that if ‘means could be found at all in the colonies of employing convicts in public works, in the same manner as Bermuda’, that sum would be reduced..Footnote73 MP John Benett argued that the labour ‘ought to be performed in the colonies’, and that if the government wanted to promote emigration, they should begin with convicts, who he called ‘the worthless part of the population’.Footnote74 Attention turned to other British colonies as possible destinations for convict transportation. Peel ruled out Canada, as facilities were slim, and convicts would need a strong military guard.Footnote75 He felt that the subject ‘deserved the most serious investigation’, and it was addressed by Select Committee on Secondary Punishments in 1831.Footnote76 The Committee interviewed the Governor of Trinidad, Major General Lewis Grant, on its fortifications. Grant stated that ‘works of defence are much wanted at Trinidad’, and that the government could deploy convict labour there as it would be ‘procured at a very low rate [and] would afford a constancy of employment’.Footnote77 Grant believed that punishment in Trinidad would be no different than that in New South Wales and Bermuda, and that work could be ‘regulated in reference to the climate’.Footnote78 Furthermore, he suggested sending convicts’ wives and families out with them, in order to establish what he called a ‘white agricultural population’, who would eventually replace the enslaved field workers.Footnote79 Grant’s proposals mirrored those already in practice in the Australian colonies, whereby convicts could finish their sentences and settle in the country.

Convicts occupied an extremely circumscribed place within settler colonialism and were excised from visions of British expansion. No plans were ever put in motion which allowed convicts to remain in Bermuda, and their stays were only temporary. Convicts were either transported home or onwards to the Australian colonies; they might also wait for their sentences to expire, or a royal pardon. Even so, a letter printed in The Bermuda Gazette in 1830 raised concerns about convicts settling on the island, asking: ‘Are these men to be turned adrift upon us? Is this little Colony to be inundated with such a swarm of felons? It is perfectly clear that the Government in England never contemplated spreading such a pestilence among us.’Footnote80 The author declared that Bermuda’s population was too high and that the island was continually low on resources, and thus unable to provision for released convicts. Bermuda’s population was estimated at around 20,000 in 1831.Footnote81 Officials routinely argued that there was not enough food on the island to support its population. Governor Turner commended in April 1827, ‘Except a small quantity of potatoes, that have been chiefly exported, and a still smaller quantity of onions and arrowroot, we have no other means of support from this barren rock, when nearly cut off from the rest of the world perfect famine presents itself.’Footnote82 At that time, Turner lamented the shutting of American ports, and how it risked driving the colony into poverty and famine. The newspaper article reveals that locals were tapping into this rhetoric as an attempt to deter settlement from undesirable groups. However, numerous advertisements for bread, meat and other supplies in local papers implied that provisions were being sourced from merchants who likely imported goods from America, not locally.

Local objections did not prevent some convicts from hoping they could remain on the island. One man who had returned from serving seven years in Bermuda allegedly reported to his friends that he planned ‘to return by the first opportunity to Bermuda as a settler, having found that he could employ his industry to better purpose there than in this country.’Footnote83 Some believed that if the government passed the necessary legislation, many former convicts would gladly return.Footnote84 However, the 1838 Select Committee on Transportation recommended that a permanent penal establishment should not be formed on the island due to the ‘strong objection which the inhabitants of the colony are understood to entertain’, in addition to voicing concerns the soil was not good enough to allow the convicts to grow crops and provide for themselves.Footnote85 The Select Committee interviewed former Commander of the Engineers at Bermuda, Colonel William Burton Tylden, who further emphasised that the islanders were ‘afraid of having a great many of those people thrown upon them.’Footnote86 The most significant example of colonial objections to convict settlement came when a selection of men (including Irish nationalist John Mitchel) were sent from Bermuda to the Cape of Good Hope on board the Neptune in the late 1840s. The proposal to establish a penal colony there was met with such furore that it became the most emotive local rallying cry for settler political representation.Footnote87

The Select Committee asked Major General Grant whether he thought the black population in Trinidad – then numbering roughly 22,000 enslaved people, not including free persons of colour – might begin to rebel against their enslavers if they saw white men in chains labouring in the fields.Footnote88 Numbers of enslaved people in Bermuda were lower than Trinidad, with some 4,608 recorded in 1827.Footnote89 Grant believed that if only 200–300 convicts were initially sent out to Trinidad, numbers would be so proportionally low that it would not be difficult to separate convicts from enslaved people.Footnote90 However, his opinion was countered by that of William Burge, Agent for Jamaica. He felt that sending convicts to Jamaica was ‘very mischievous [and] altogether impracticable’ as the black population there vastly outnumbered the white population.Footnote91 Furthermore, he argued that there were no public works in Jamaica left for the convicts to be put to work on, as all forts and barracks had been completed, and that the roads were maintained by the enslaved population.Footnote92 Burge’s rejection of convict transportation to the Caribbean is at odds with the situation in Bermuda. The island was far smaller than Trinidad, and there, too, the black population – free and enslaved – outnumbered white settlers and convicts. Vice Admiral Charles Fleeming felt that race relations in Bermuda were stronger than any islands he had visited in the Caribbean, stating that the free and enslaved population in Bermuda were ‘more moral’, and that their enslavers were ‘smaller proprietors who live almost with [them]’, perhaps accounting for stability on the island.Footnote93 These concerns tie back to the ‘Botany Bay decision’ to send convicts to New South Wales; one attraction of sending convicts to Australia was that it sidestepped the problems associated with deploying a largely white coerced labour force alongside African coerced workers.

Racial intermixing was not unique to Bermuda’s dockyards; by 1803, black men (mostly free) filled about 18 percent of American seamen’s jobs, until mid-century changes in waterfront hiring practices began to squeeze them out of the maritime labour force.Footnote94 In the Caribbean, it was remarked that some men labelled as military labourers were in fact formed from disbanded West India regiments, or were ‘captured negroes’ or enslaved people.Footnote95 The presence of black workers on public works in the colonies strikes a contrast with the royal naval dockyards in England, which largely excluded them.Footnote96 Although convicts in the dockyards were separated from the general population, segregating them from Bermuda’s free and enslaved workers was impossible. It was remarked that ‘black labourers and black women’ communicated with convicts, the latter of whom ‘brought things on board, fruit and vegetables’.Footnote97 These exchanges carried risks, as they increased opportunities to buy and sell prohibited goods. From the perspective of the convict establishment in Bermuda – as opposed to colonial administrators, or inhabitants of the island – opposition to racial intermixing centred around access to alcohol. In January 1829, Commissioner Briggs and the overseer at Bermuda reported that convicts had obtained spirits ‘from some free persons, when on shore at labour.’Footnote98 Superintendent Capper in England attributed these spirits to the ‘spirit of great insubordination [which] had manifested itself among a few of the most incorrigible convicts’.Footnote99 One year previously, Capper had stated in a letter to Briggs that the value of military guards was twofold: they not only oversaw the labouring convicts, but also ‘prevent[ed] the intercourse of free persons with the convicts’.Footnote100

While convicts were not generally permitted alcohol, unless in the form of small beer or the occasional measure of rum, it is worth noting that alcohol consumption in all royal naval dockyards was frowned upon. In 1835, Superintendent Capper commented that convicts were sometimes rewarded with a pint of beer a day for particularly laborious work, but that in Chatham dockyard, a new system of policing prevented shipwrights and other workers from bringing ‘a drop of beer into the yard, or any liquor whatever.’Footnote101 In Bermuda, attempts to restrict the sale of alcohol to convicts reached the local press; in 1838, a notice was placed on the front page of the Royal Gazette, under the headline ‘CAUTION’.Footnote102 Addressed to all those employed in the dockyard, or who had business on Ireland Island, the notice outlined the case of two Bermudian black men employed as carpenters in the dockyard, Richard Jobson and John Carmichael. The men had been charged with supplying ‘ardent spirits to the convicts’ and were fined twenty pounds alongside being given a jail sentence of three months.Footnote103 The men would not face any time on the hulks, however, as legislation passed in 1827 decreed that all enslaved or free people would be ‘employed upon the tread-mill’ in Hamilton and St George gaols, a repetitive, non-productive form of punishment.Footnote104 Their case served as a warning to others tempted to sell illicit goods to convicts. However, it also goes some way to show that convicts and local labourers found moments to come together, forming alliances and supply chains of their own.

Very few images depicting Bermuda’s convict station exist, and ever fewer show its convict labourers. However, a collection of watercolour sketches dating from 1860 provide some insight into the interactions between convicts and local workers. is an image entitled ‘Sick convicts going to hospital’ and depicts three white convicts descending some wooden steps to board a small boat. A dark-skinned man to the left of the image is seen waiting for the convicts, the sail of the boat behind him. The convicts are easily recognisable due to their linen uniforms. In the 1840s, Irish political prisoner John Mitchel kept a journal on board the Dromedary hulk and described the hulks as ‘peopled by men in white linen blouses and straw hats’.Footnote105 The prisoners in have the words ‘Medway’, the name of a prison hulk, sewn onto the front of their clothing, along with their numbers. Their blue armbands may refer to a system of classification that separated them according to behaviour. The dark-skinned man in the boat is dressed differently, in a blue shirt, and tailored trousers. He is wearing a straw hat much like that worn by the convicts, which may signify that he is employed by the establishment. This image confirms that black pilots ferried convicts from the hulks to the dockyards. There is no presence of an overseer, which suggests that once on the water, convicts may have conversed freely in the boat. Befriending men who knew how to sail presented opportunities to escape. Indeed, Governor Turner stated in 1828 that in their daily journeys to and from the hulks, the convicts ‘have it in their power to board any merchantmen and sail away.’Footnote106 As such, befriending boatmen was a further reason why authorities frowned upon intermixing of free black sailors and convict workers.

Perceptions and Corruption: White Workers

In a report published in 1824, Lieutenant-Governor Arthur in Van Diemen’s Land observed that the convict ‘is a slave, but while he feels very deeply the degradation of slavery, he looks forward to its conclusion’.Footnote107 Many convicts, unlike enslaved people, knew when their sentences would expire, and that they would become free men. However, as various reformers and members of parliament grew to criticise transportation as a form of punishment from the 1830s onwards, public conflations between slavery and convicts continued.Footnote108 Discussing transportation to New South Wales, Edward Gibbon Wakefield declared in 1831 that the convict ‘lives very comfortably, though he may be called a slave’.Footnote109 The Governor of Cold Bath Fields house of correction in Clerkenwell, George Laval Chesterton concurred, ‘I always endeavoured to impress upon them [prisoners] that transportation over the seas is absolute slavery; but they seemed to listen to the statements with that sort of distrust, that I think they do not believe it to be the case.’Footnote110 These comparisons between the convict experience and slavery are interesting – despite this use of language, transportation had rarely been viewed as a punishment severe enough for offenders, or a deterrent against crime. In fact, Wakefield stated that many prisoners he had spoken to had their minds ‘bent upon the colonies […] and bent upon attaining a degree of wealth and happiness’.Footnote111 Although convicts could not settle in Bermuda, transportation itself could provide many with an opportunity to gain a degree of education, save the small payments they had earnt, and have a fresh start once released.Footnote112

Reformers and administrators were blurring the lines between convict labour and slavery, but news media reinforced this at a local level. Bermuda’s presses gave inhabitants opportunities to read – and form opinions – about convicts. Articles printed in the Royal Bermuda Gazette and the Bermuda Gazette show that usage of terms related to slavery and abolition to describe convicts were relatively commonplace. In 1820, four years before the arrival of the Antelope, the Gazette published an article with a detailed description of a convict ship to New South Wales. The article described the layout of the ships with imagery evocative of slave ships and the middle passage.Footnote113 One paragraph on the use of chains stated: ‘this image of slavery is copied from the irons used in the slave ships in Guinea; as in these, bolts and locks are also at hand.’Footnote114 As many Bermudian landowners and merchants were also enslavers, these images were potentially less shocking to them as readers than those in England who had less direct contact with enslaved people. In 1827, Governor Turner remarked that he was ‘sorry to observe that much prejudice exists on the part of the white inhabitants generally to extend in any degree [the benefits of education] to the children of the slave and free coloured population, particularly the former’.Footnote115 This reluctance amongst white residents to promote education is demonstrative of a wider disinclination to invest in the marginalised communities on the island. It’s interesting therefore that the newspaper article depicted white people in chains; editors may have felt that these descriptions would provoke a reaction amongst their readers, but it’s unclear whether that would have been sympathy, or simply a morbid fascination with criminality.

One incident in July 1830 is a noteworthy example that convicts themselves recognised the parallels between their experience and that of enslaved people. In a report to Home Secretary Peel, Superintendent Capper reported that convicts on board the Coromandel hulk had caused some disturbance that year and had lately ‘committed acts of great violence on the persons of the officers placed over them.’Footnote116 The Bermuda Gazette covered the story, claiming that one convict, James Ryan, was mistakenly shot by convicts who were attempting to shoot their overseers. The Gazette reported that convicts on the Coromandel reportedly sang the rallying cry, ‘Brittons (sic.) never will be Slaves’.Footnote117 The chant, a line from the song ‘Rule Britannia’, highlighted tensions on board. Convicts identified as British and so clung to a sense of their national identity but saw their labour as a form of slavery. Their status as British – and potentially, their whiteness – connected them to concepts of freedom, especially significant in the wider context of abolition. By printing details of this incident, the Gazette strengthened perceived links between forced labour and slavery. Ease of communication on board the hulks heightened the risk of convicts spreading feelings of discontent, but further connections to slavery can be identified in the convicts’ use of song as a refuge from, or challenge to oppression.Footnote118 The article portrayed the convicts as a dangerous group, liable to cause harm if not properly regulated. In fact, Capper later reported that William Tate at Portsmouth remarked that a small number of convicts from Bermuda who had been sent back displayed ‘a strong spirit of insubordination, and [have] been refractory in the extreme’.Footnote119

Official correspondence reveals a concern of moral corruption arising from interactions between convicts and other white workers in Bermuda; in 1827, Governor Turner wrote to the Prime Minister Frederick Robinson that the military detachment at Ireland Island overseeing the convicts had good morals, which prevented their risk of corruption: ‘It is possible, even probable, nothing serious may arise but they are in possession of power and prudence forbids their temptation.’Footnote120 Knowing that they possessed weapons was seen to ensure their mastery over the convicts. However, if convicts ever likened their experience to that of slavery, or objected to the parallels documented in the Royal Gazette, there was still a risk this feeling would spread to other workers. Yet the living and working conditions of Bermuda’s white military workers were far removed from the close and humid decks of the prison hulks. The military garrison was situated on a ‘high, healthy and beautiful position’, and were equipped with sleeping quarters, outhouses, canteens and cooking houses, with even plans for a public house.Footnote121 To increase security, it was deemed a matter of propriety that a ship of war should be stationed close to Ireland Island, where the convicts laboured.Footnote122 Unlike convicts, sappers and miners were allowed to be accompanied to Bermuda by their families. A letter from Chaplain R.R. Bloxham in June 1827 remarked that eighty ‘wives and children have arrived on the Hebe’.Footnote123 This group therefore had not only a degree of liberty, but also a larger familial – and social – network on which to rely.

In March 1827, Governor Turner wrote to Secretary of State for War and the Colonies Earl Bathurst and stated that the military presence on the island was small; he referred to the 96th Regiment, which had been recruited in Ireland, and a ‘small attachment of artillery sappers and miners’.Footnote124 On the 96th Regiment, Turner remarked that they were very young men, who were chiefly employed in working parties. They were ‘much given to drink and irregular behaviour’.Footnote125 As well as working on construction in the dockyards, the sappers and miners were responsible for guarding the 700 convicts in Bermuda at that time; their roles ranged from carpenters, masons and smiths, to foremen, overseers, and in some instances clerks of the works.Footnote126 They could both perform labour and superintend the convicts. Turner’s concerns about the drunkenness of the young Irish men in the 96th Regiment were realised one year later; in September 1828, despatches detailed the criminal cases of two former soldiers of the 96th Regiment, suggesting that all three should be transferred to the convict establishment at Ireland Island as there were no means to send them to any other destination for punishment.Footnote127 The two army men – Brian Shea and Edward McDonald – had been stationed in Bermuda with their regiment between 1825–8 and were convicted of highway robbery.Footnote128 The 96th Regiment had been raised in Ireland, and was later to provide detachments for convict ships sailing to the Australian colonies.Footnote129 In contemporary accounts, the Irish soldier was portrayed as drunken, ill-disciplined, and only effective when led by English officers.Footnote130 Indeed, Turner’s initial letter made comment on ‘Major White, a steady and zealous officer’ who commanded the regiment.Footnote131 Irish soldiers therefore constituted a white social group who faced prejudice.

The case of military prisoners Shea and McDonald show that some prisoners who had been convicted in Bermuda itself were also sent to the hulks. But the presence of former military convicts on board the hulks was seen to pose a further security risk. These prisoners came to the hulks with connections outside, and knowledge about the system. As the site became more established, military deserters from Canada and the Caribbean were sent to Bermuda, with 118 convicted by court martial in the colonies in 1837 alone.Footnote132 In November 1828, Governor Turner wrote that the convicts on board the Coromandel were behaving in a disorderly manner, striking their keepers and cheering violent outbreaks. He believed that prisoners had become incensed ‘by some information, that the laws of Bermuda are more lenient than even their present discipline.’Footnote133 Turner felt that troops might be needed on board, but had concerns as there were ‘many who have been soldiers among the convicts’.Footnote134 A fortnight later, Turner came back to the subject, commenting that he did not approve of plans to house Shea and McDonald from the 96th Regiment on the hulks; he stated that the convict hulks had recently some 50 Irish prisoners who were ‘very bad characters’ and that when the 96th Regiment was stationed at Ireland Island ‘there might be more communication than was prudent between them’.Footnote135 Irish prisoners bonding with members of the regiment, or with Shea and McDonald posed a risk. Turner felt that court martialled soldiers, particularly deserters, should not be sent to Bermuda, as working alongside military personnel ‘they would find the soldiers more ready to commiserate, and to communicate with them.’Footnote136

When military deserters were housed on the hulks, this led to increased security fears. In one incident where convicts became riotous, Turner blamed intermixing: ‘It is much to be regretted that so large a number of convicts are deserters from the troops, and that the contempt, and detestation in the soldiers is so much diminished’.Footnote137 He outlined that it was impossible to prevent communication between the military deserters and any former acquaintances. Although Governor Turner pushed to stop the flow of military deserters being housed on the hulks, he was overruled. Home Office records for Shea show that he was in Bermuda on 5 November 1828 with a life sentence, but there is no evidence McDonald was on the hulks.Footnote138 In some cases, ex-military prisoners petitioned for mercy; in 1829, Patrick White, a former soldier in Halifax’s 96th Regiment successfully petitioned for discharge after seven years’ service due to a severe injury to his left foot in a quarry in Bermuda.Footnote139 White’s pardon was recommended by the overseer of the Antelope hulk, R. Skinner, and the Commissioner of Bermuda Yard, Thomas Briggs. Some concerns around white labourers intermixing – both in the dockyards and on the hulks themselves – were based on ethnicity, or social class. But correspondence reveals that any situation in which military workers found themselves talking to or feeling sympathy for convicts – and in some cases, living alongside them – was where boundaries became porous. Their uniforms may have differed, and their status, but skin colour set convicts and colonial soldiers apart from black Bermudian workers. Any rioting, or collusion between them, would therefore undermine attempts to maintain white hegemony in the colony.

Conclusion

This article has examined the interactions between convict labourers in Bermuda and enslaved, free, and military workers. In Bermuda, convicts were part of a wider network of labourers that was not forcefully divided by race or class. The sources examined here show that a greater sense of administrative anxiety existed amongst colonial officials and local inhabitants when white workers intermixed. In all cases, it was felt that communication amongst free and unfree labourers created security risks in a colony that was not yet fully fortified, or necessarily easy to control, so far removed from England. For Governor Turner, it was imperative that the work in the dockyard complex was quickly completed and the site secured. In a letter to William Huskisson in 1828, he stated that steamboats could reach the island easily, and that in New York, a Bermudian pilot was kept employed to help navigate the difficult passages. In this context, Turner believed that the convicts posed a more serious security risk – not to the colony, but to the empire more broadly, stating ‘the easy means of intelligence an enemy can have with the convicts previous to any attempt [of attack]’ made Ireland Island vulnerable.Footnote140 It was therefore important that collusion between different types of workers was eradicated. Although sources show that there were objections to racial intermixing in Bermuda, what we see more strongly are objections to mixing between different classes – convicts were lower class, what William Burge in Jamaica labelled ‘in a degraded state’, while military workers were socially superior.Footnote141

This article highlights how much the contexts of colonial infrastructure projects and labour deployment could differ according to locale. The specific dynamics of Bermuda’s dockyard were reflected in both the hulks and in local labour forces. There was no alternative labour supply after the abolition of slavery in 1833, so convicts answered the colony’s demand for labour. Bermuda’s convict hulks themselves housed a more mixed society on board than in England, and included prisoners from British colonies, such as Demerara, Canada, and Ireland. This diversity was not necessarily a security risk, but it was an unknown to administrators, who were wary of collaboration. Convicts may have constituted a lower class of white worker – and even identified their experience as similar to that of enslaved people – but when we compare concerns over intermixing, far greater emphasis was placed on fears over the corruption of white workers. Does this suggest that colonial administrators feared an uprising of white workers?

Together, Bermuda’s free and un-free labourers were empire-builders; their work consolidated power and strengthened Britain’s capacity to trade. Without them, the designs to make Bermuda an imperial fortress would not have been realised. However small the location, their role was key, and their coexistence was part of a wider context of colonial labour deployment that must be incorporated into larger imperial histories. The reliance on contrasting labour regimes in Bermuda’s dockyards made it a unique site for British convict administration. But management changed on 1 January 1838 when the new Governor of the island, William Reid, was officially given sole responsibility of the convict station. The establishment was transferred from Home Office to Colonial Office control and Superintendent Capper’s authority in Bermuda was abolished by an act of parliament. Furthermore, as Reid pushed for more improvements in the island’s maritime infrastructure, the whole service of supply, payment and account was transferred to the Treasury.Footnote142 Future studies will require a fuller, longitudinal examination of Bermuda’s convict establishment, considering convict flows from Caribbean colonies, rising numbers in the years after abolition, and influxes from Ireland during the turbulent famine years. The period assessed within this article has brought to light some of the human elements of penal and colonial legislation that are often forgotten. By examining the relationships and networks sustained by convicts and the island's diverse workforce, we can take the first steps towards rebuilding their lives and experiences.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dr Kristy Warren and Professor Claire Connolly for their feedback and discussion.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Hansard – Commons, Criminal Laws, 429.

2 BPP, Select Committee on Secondary Punishments (1831), Minute 1650, 118.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid, Minutes 1654–7, 119.

5 Willock, Bulwark of Empire, 2.

6 See Jarvis, In the Eye of All Trade.

7 See Grocott, “A Good Soldier, but a Maligned Governor,” Gregory, Malta, Britain, and the European Powers and Cuthbertson, The Halifax Citadel.

8 Jarvis, Eye of all Trade.

9 Anderson, “After Emancipation,” 114. See also Anderson, Convicts.

10 Bernhard, Slaves and Slaveholders in Bermuda, 274.

11 Smith, Slavery in Bermuda.

12 Pike, Penal Servitude.

13 Bosma, “European Colonial Soldiers”.

14 Brandon et al., “Free and Unfree Labor,” 1–18.

15 See Nilson, “Hey Sailor, Looking for Trouble?” and Thayer, “Sailors’ Homes”.

16 Beaven, “The Resilience of Sailortown Culture”. See also Milne, People, Place and Power.

17 Jarvis, In the Eye of All Trade.

18 Coats, “Bermuda Naval Base”; Jarvis, “Maritime Masters and Seafaring Slaves”; Smith, Slavery in Bermuda.

19 See also Steinfeld, Coercion, Contract, and Free Labor and Klein, “Slavery, The International Labour Market”.

20 Anderson, Subaltern Lives; Anderson, “Convicts and Coolies”; Saunders (ed.), Indentured Labour in the British Empire; Northrup, Indentured Labour in the Age of Imperialism. Mattos, Laborers and Enslaved Workers Experiences.

21 Bosma, “European Colonial Soldiers” and Thomas, “Securing Trade”. See also Mansfied, Soldiers as Workers.

22 Jeppesen, “Within the Protection of Law”; Lydon, Anti-Slavery and Australia; Barrett Meyering, “Abolitionism, Settler Violence and the Case Against Flogging,” Maxwell-Stewart, ““Like Poor Galley Slaves … .””.

23 Maxwell-Stewart, ““Like Poor Galley Slaves … .””, 58.

24 Frost and Maxwell-Stewart have addressed the difficulty of piecing together fragmentary evidence in Chain Letters; see also Stoler, Along the Archival Grain.

25 See Foreman, et al., “Writing about Slavery/Teaching About Slavery”.

26 Prince, The History of Mary Prince, 1.

27 For more on slavery in Bermuda, see Outerbridge Packwood, Chained on the Rock.

28 See Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers,” 9.

29 Hollis Hallett, Forty Years of Convict Labour, 2.

30 Coats, “Bermuda Naval Bases,” 166.

31 NMM, LAD 29, sections entitled “Negro Labourers” and “Bermudian Negroes,” 2–3.

32 Coats, “Bermuda Naval Bases,” 149.

33 Slave Trade Act, 1807: 47 Geo III Sess. 1 c. 36.

34 Although the “racial” balance was altered, the total population of Bermuda remained relatively stable; in 1729, the population of Bermuda was 8,774; just over a century later, the 1851 census showed the population to be 11,092. See Warren, “A Colonial Society in a Post-Colonial World,” 14 (citing Packwood, Chained on the Rock, 33 and Godet, Bermuda, 154).

35 Hansard – Lords, Slavery in the West Indies (1826), 202–7.

36 Klein, “Slavery, the International Labour Mart and the Emancipation of Slaves,” 212.

37 Packwood, Chained on the Rock, 69.

38 Hansard – Commons, Ordnance Estimates (1821), 681–93.

39 MacDougall, “The Changing Nature of the Dockyard Dispute,” 56.

40 Emsley, Crime and Society in England, 13.

41 Hansard – Commons, Criminal Laws (1822), 790–805.

42 Ibid.

43 BPP, Reports Relating to Convict Establishments (No.2), 1823, 5.

44 McConville, English Prison Administration, 144–5; McRorie Higgins, “The Scurvy Scandal at Millbank Penitentiary,” 513–34.

45 See also McKay, ““Allowed to Die”?”.

46 “Millbank Penitentiary,” Morning Chronicle, 14 July 1823.

47 McConville, English Prison Administration, 145. See also Hansard – Commons, Penitentiary House at Millbank (1824), 636–40.

48 Male Convicts Act: 1823, 4 Geo. IV, c.47.

49 Hansard – Commons, Navy Estimates (1824), 296–301.

50 Ibid.

51 Campbell, The Intolerable Hulks, Appendix A, 228.

52 See Christopher, A Merciless Place and Maxwell-Stewart, “Transportation from Britain and Ireland”.

53 Nicholas and Shergold, “Transportation as Global Migration,” 28–43.

54 TNA, HO 17/88/85, 15 December 1828.

55 Ibid.

56 TNA, CO 37/85, “Navy Office,” 25 April 1825 and 4 February 1825, 271–75.

57 BPP, Account of Number of Convicts Transported to British Colonies (1822–23), 1–2.

58 Ibid.

59 BPP, Reports Relating to Convict Establishments (No.1), 1827, 3.

60 BPP, Reports Relating to Convict Establishments (No.2), 1825, 6.

61 Hansard – Commons, Army Estimates (1826), 1119–31.

62 Hansard – Commons, Miscellaneous Estimates (1828), 907–15.

63 BPP, Correspondence with Governors of Colonies in W. Indies respecting Insurrections of Slaves (1822–24), No.14, 66.

64 TNA, CO 37/86, “Home Department,” 6 June 1826, 153.

65 TNA, HO 17/123/75, Petition of Samuel Smithson, 17 February 1830.

66 TNA, CO 37/90/16, 22 April 1830, 50–51.

67 BPP, Return of Number of Slaves registered in Slave Colonies (1833), 2. Figures for 1838 are taken from Population Returns from Slave Colonies since 1833 (1835).

68 See Anderson, “Transnational Histories of Penal Transportation,” 387.

69 TNA, CO 37/87/10, “Population,” 8 March 1827, 48.

70 See Craton, “Reshuffling the pack,” 45–6.

71 Ibid, 45.

72 BPP, Select Committee on Transportation (1837), Minute 1017, 87. See also NMM, LAD 29. BPP, Select Committee on Transportation (1837), Minute 1209, 103.

73 Ibid.

74 Ibid.

75 Hansard – Commons, Miscellaneous Estimates – Millbank Penitentiary (1830).

76 Ibid, and BPP, Select Committee on Secondary Punishments (1831).

77 BPP, Select Committee on Secondary Punishments (1831), Minute 1491, 105.

78 Ibid, Minute 1492, 105.

79 Ibid, Minute 1493, 105.

80 “TO THE EDITOR OF THE ROYAL GAZETTE,” Bermuda Royal Gazette, 4 April 1830.

81 Hansard – Commons, Newfoundland (1831), 1377–88.

82 TNA, CO 37/87/10, 9 April 1827, 66.

83 BPP, Select Committee of House of Lords on Gaols and Houses of Correction in England and Wales (1835), 482.

84 Ibid.

85 BPP, Select Committee on Transportation (1837), xliii.

86 Ibid, Minute 1000, 86.

87 See Anderson, “Convicts, Carcerality and Cape Colony”; Lester, Imperial Networks, 177.

88 BPP, Select Committee on Secondary Punishments (1831), Minute 1502–10, 106.

89 BPP, Return of Slave Population in H.M. Colonies in W. Indies (1828), 1.

90 BPP, Select Committee on Secondary Punishments (1831), Minute 1506, 106.

91 Ibid, Minute 1650, 118.

92 Ibid.

93 BPP, Report from Select Committee on the Extinction of Slavery (1831–2), Minutes 2839-2840, 218–9.

94 Bolser, Black Jacks, 6.

95 BPP, Second Report from the Select Committee on the Public Income and Expenditure of the United Kingdom, Appendix No.1 (9.), 236.

96 See Foy, “Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners,” 6–35.

97 BPP, Select Committee on Transportation (1831), Minute 1209, 103.

98 BPP, Reports Relating to Convict Establishments (No.2), 1829, 7.

99 Ibid.

100 TNA, CO 37/88/23, 2 December 1828, 119.

101 BPP, Select Committee of House of Lords on Gaols and Houses of Correction in England and Wales (1835), 258.

102 “CAUTION,” Bermuda Royal Gazette, 14 August 1838.

103 Ibid.

104 BPP, Papers in Explanation of Measures adopted for Amelioration of Condition of Slave Population in H.M. Possessions in W. Indies, S. America and Mauritius (1829), 88.

105 Mitchel, Jail Journal, 57.

106 TNA, CO 37/88/23, “Commander in Chief,” 4 August 1828, 99.

107 BPP, Correspondence between Secretary of State and Australian Colonies on Secondary Punishments (1834), 25.

108 Barrett Meyering, “Abolitionism, Settler Violence and the Case Against Flogging,” 06.3. Maxwell-Stewart writes that the campaign against slavery, which solidified in the period 1823-1838, had a direct impact upon attitudes towards convict transportation, in ““Like Poor Galley Slaves … .,”” 52. See also Jeppesen, “Within the protection of law” and Lydon, Anti-Slavery and Australia.

109 BPP, Select Committee on Secondary Punishments (1831), Minute 1441, 102.

110 BPP, Select Committee on Secondary Punishments (1831), 40.

111 BPP, Select Committee on Secondary Punishments (1831), Minute 1397, 98.

112 See Carey, Empire of Hell, 257-281.

113 “Description of a Convict Ship,” Bermuda Gazette, 23 September 1820.

114 Ibid.

115 TNA, CO 37/87/10, “Education,” 8 March 1827, 42.

116 BPP, Reports Relating to Convict Establishments (No.1), 1830, 1.

117 “John Wilkins, Second Mate … ,” Bermuda Royal Gazette, 4 May 1830.

118 White and White, The Sounds of Slavery, 93.

119 BPP, Reports Relating to Convict Establishments (No.1), 1830, 2.

120 TNA, CO 37/87/22, 24 September 1827, 138–9.

121 TNA, CO 37/87/10, “Military Establishment,” 8 March 1827, 47.

122 TNA, CO 37/87/22, “Admiralty,” 1 December 1827, 293.

123 TNA, CO 37/87/10, 1 June 1827, 79.

124 TNA, CO 37/87/10, “Military Establishment,” 8 March 1827, 40.

125 Ibid.

126 BPP, Second Report from the Select Committee on the Public Income and Expenditure of the United Kingdom, 95.

127 TNA, CO 37/88/18, No 14, 11 September 1828, 56–57.

128 TNA, CO 37/88/18, 17 May 1828, 23.

129 Petrow, ““Military Outrage””.

130 Deery, “The Contribution of the Irish Soldier”.

131 TNA, CO 37/87/10, “Military Establishment,” 8 March 1827, 40.

132 BPP, Reports Relating to Convict Establishments (No.2), 1837, 5. See also Henderson, “Banishment to Bermuda”.

133 TNA, CO 37/88/20, No.16, 2 November 1828, 60–1.

134 Ibid.

135 TNA, CO 37/88/23, No 19, 15 November 1828, 66–67.

136 Ibid.

137 TNA, CO 37/90/9, No.7, 22 March 1830, fol.28.

138 TNA, HO 13/52/26, 5 November 1828.

139 TNA, HO 17/63/67, Petition of Patrick White, December 1829.

140 TNA, CO 37/88/3, 25 February 1828, 7–8.

141 Hansard – Commons, Criminal Laws, 429.

142 Hollis Hallet, Forty Years of Convict Labour, 19.

References

- Anderson, Clare. “After Emancipation: Empires and Imperial Formations.” In Emancipation and the Remaking of the British Imperial World, edited by Keith McClelland, Nicholas Draper, and Catherine Hall, 113–127. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014.

- Anderson, Clare. “Convicts and Coolies: Rethinking Indentured Labour in the Nineteenth Century.” Slavery & Abolition 30, no. 1 (2009): 93–109. doi:10.1080/01440390802673856.

- Anderson, Clare. Convicts: A Global History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Anderson, Clare. “Convicts, Carcerality and Cape Colony Connections in the 19th Century.” Journal of Southern African Studies 42, no. 3 (2016): 429–442. doi:10.1080/03057070.2016.1175128.

- Anderson, Clare. Subaltern Lives: Biographies of Colonialism in the Indian Ocean World, 1790–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Anderson, Clare. “Transnational Histories of Penal Transportation: Punishment, Labour and Governance in the British Imperial World, 1788–1939.” Australian Historical Studies 47, no. 3 (2016): 381–397. doi:10.1080/1031461X.2016.1203962.

- Barrett Meyering, Isobelle. “Abolitionism, Settler Violence and the Case Against Flogging: A Reassessment of Sir William Molesworth’s Contribution to the Transportation Debate.” History Australia 7, no. 1 (2010): 06.1–06.18. doi:10.2104/ha100006.

- Beaven, Brad. “The Resilience of Sailortown Culture in English Naval Ports, c. 1820–1900.” Urban History 43, no. 1 (2016): 72–95. doi:10.1017/S0963926815000140.

- Bermuda Gazette. Description of a Convict Ship. 23 September 1820.

- Bermuda Royal Gazette. “CAUTION.” 14 August 1838.

- Bermuda Royal Gazette. “John Wilkins, Second Mate … .” 4 May 1830.

- Bermuda Royal Gazette. “TO THE EDITOR OF THE ROYAL GAZETTE.” 4 April 1830.

- Bernhard, Virginia. Slaves and Slaveholders in Bermuda, 1616–1782. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999.

- Bolser, Jeffrey. Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Bosma, Ulbe. “European Colonial Soldiers in the Nineteenth Century: Their Role in White Global Migration and Patterns of Colonial Settlement.” Journal of Global History 4, no. 2 (2009): 317–336. doi:10.1017/S1740022809003179.

- BPP (British Parliamentary Papers). Account of Number of Convicts Transported to British Colonies, 1822–23. 1824, Sessional Papers 19: 1–2.

- BPP. Correspondence between Secretary of State and Australian Colonies, on Secondary Punishments. 1834, Sessional Papers, Paper No.82, Vol.47.

- BPP. Correspondence with Governors of Colonies in W. Indies respecting Insurrections of Slaves, 1822-24. 1824, Sessional Papers, Paper No. 333. Vol.23.

- BPP. Papers in Explanation of Measures Adopted for Melioration of Condition of Slave Population in H.M. Possessions in W. Indies, S. America and Mauritius. 1829, Sessional Papers, Paper No. 333, Vol. 25.

- BPP. Population Returns from Slave Colonies since 1833. 1835, Sessional Papers, Paper No.420, Vol. 51.

- BPP. Report from Select Committee on the Extinction of Slavery throughout the British Dominions, 1831-2. Sessional Papers, Paper No.721, Vol.20.

- BPP. Report from the Select Committee on Criminal Commitments and Convictions. 1828. Sessional Papers, Paper No.545, Vol.6.

- BPP. Report from the Select Committee on Secondary Punishments, 27 September 1831, Sessional Papers, vol. 7, 1–177.

- BPP. Report from the Select Committee on Transportation. 14 July 1837, Commons Papers, Paper No. 151, vol. 19, 1–754.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments.1823, Sessional Papers, vol. 15, 1–10.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments. 1825, Sessional Papers, vol. 23, 1–10.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments. 1826-7, Sessional Papers, vol. 19, 1–12.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments. 1828, Sessional Papers, vol. 20, 1–12.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments, 1829, Sessional Papers, vol. 18, 1–16.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments, 1830, Sessional Papers, vol. 23, 1–16.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments, 1830-1, Sessional Papers, vol. 12, 1–16.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments, 1831-2, Sessional Papers, vol. 33, 1–16.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments, 1833, Sessional Papers, vol. 28, 1-12.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments, 1834, Sessional Papers, vol. 47, 1-12.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments, 1835, Sessional Papers, vol. 45, 1-10.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments, 1836, Sessional Papers, vol 41, 1-10.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments. 1837, Sessional Papers, vol. 72, 1-10.

- BPP. Reports Relating to Convict Establishments. 1837-8, Sessional Papers, vol. 42, 1-10.

- BPP. Return of Number of Slaves registered in Slave Colonies. 1833, Sessional Papers, Paper No.539, Vol.26.

- BPP. Return of Slave Population in H.M. Colonies in W. Indies. 18 April 1828, Sessional Papers, Vol.25.

- BPP. Second report from the Select Committee on the Public Income and Expenditure of the United Kingdom (Ordnance Estimates), 1822. 1828, Sessional Papers, Paper No.420, Vol.5.

- BPP. Select Committee of House of Lords on Gaols and Houses of Correction in England and Wales. 1835, Sessional Papers, Vols.11, 495, 12 and 57.

- Brandon, Pepijn, Niklas Frykman, and Pernille Røge. “Free and Unfree Labor in Atlantic and Indian Ocean Port Cities (Seventeenth–Nineteenth Centuries).” International Review of Social History 64, no. S27 (2019): 1–18. doi:10.1017/S0020859018000688.

- Caird Library, National Maritime Museum (NMM), LAD29 [formerly HIS/21]. “On the several methods of providing artificers and labourers for the works connected with the dockyard on Ireland Island.” Bermuda, ca.1863.

- Campbell, Charles. The Intolerable Hulks: British Shipboard Confinement, 1776–1857. Tuscon, Arizona: Fenestra Books, 2001.

- Carey, Hilary. Empire of Hell: Religion and the Campaign to End Convict Transportation in the British Empire, 1788–1875. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Christopher, Emma. A Merciless Place: The Lost Story of Britain's Convict Disaster in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Coats, Anne. “Bermuda Naval Bases: Management, Artisans and Enslaved Workers in the 1790s: The 1950s Bermudian Apprentices’ Heritage.” The Mariner’s Mirror 95, no. 2 (2009): 149–178. doi:10.1080/00253359.2009.10657094.

- Craton, M. J. “Reshuffling the pack: the transition from slavery to other forms of labor in the British Caribbean, ca. 1790-1890.” New West Indian Guide/Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 68, no. 1–2 (1994): 23–75. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002659.

- Criminal Law Act, 1776: 16 Geo III, c.43.

- Cuthbertson, Brian. The Halifax Citadel: Portrait of a Military Fortress. Halifax: Formac Publishing Company, 2001.

- Deery, James. “The contribution of the Irish soldier to the British Army during the Peninsula campaign 1808 – 1814.” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 98, no. 394 (2020): 239–261. doi:10.33232/JMHDS.1.1.11.

- Ekirch, Roger A. Bound for America: The Transportation of British Convicts to the Colonies, 1718–1775. Oxford: Clarendon, 1987.

- Emsley, Clive. Crime and Society in England, 1750–1900. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Godet, Theodore L. Bermuda: Its History, Geology, Climate, Products, Agriculture, Commerce, and Government, From the Earliest Period to the Present Time; With Hints to Invalids. London: Smith, Elder and Company, 1860.

- Henderson, Jarett. “Banishment to Bermuda: Gender, Race, Empire, Independence and the Struggle to Abolish Irresponsible Government in Lower Canada.” Histoire sociale / Social History 46, no. 92 (2013): 321–348. doi:10.1353/his.2013.0073.

- Hollis Hallett, C. F. E. Forty Years of Convict Labour: Bermuda 1823-1863. Bermuda: Juniperhill Press, 1999.

- Foreman, P. Gabrielle et. al., ‘Writing about Slavery/Teaching About Slavery: This Might Help’ community-sourced document, Accessed April, 15, 2021. https://naacpculpeper.org/resources/writing-about-slavery-this-might-help.

- Foy, Charles R. “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783.” International Journal of Maritime History 28, no. 1 (2016): 6–35. doi:10.1177/0843871415616922.

- Frost, Lucy, and Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, eds. Chain Letters: Narrating Convict Lives. Carlton South: Melbourne University Press, 2001.

- Gregory, Desmond. Malta, Britain, and the European Powers, 1793–1815. Vancouver: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1996.

- Grocott, Chris. “A Good Soldier, but a Maligned Governor: General Sir Archibald Hunter, Governor of Gibraltar 1910–13.” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 37, no. 3 (2009): 421–439. doi:10.1080/03086530903157615.

- House of Commons. Army Estimates. 6 March 1826, vol. 14, cc.1119-31.

- House of Commons. Criminal Laws. 4 June 1822, Vol.7, cc.790-805.

- House of Commons. Miscellaneous Estimates. 30 May 1828, vol. 19, cc.907-15907.

- House of Commons. Miscellaneous Estimates – Millbank Penitentiary. 21 May 1830, vol. 24, cc.938-51938.

- House of Commons. Navy Estimates. 20 February 1824, vol. 10, cc.296-301.

- House of Commons. Newfoundland. 13 September 1831, vol. 6, cc.1377-88.

- House of Commons. Ordnance Estimates. 11 May 1821, vol. 5, cc.681-93.

- House of Commons. Penitentiary House at Millbank. 1 March 1824, vol. 10, cc6.36-40.

- House of, Lords. Slavery in the West Indies – Memorial of the Assembly at Antigua. 14 April 1826, vol. 15, cc.202-7.

- Jarvis, Michael J. “Maritime Masters and Seafaring Slaves in Bermuda, 1680–1783.” The William and Mary Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2002): 585–622. doi:10.2307/3491466.

- Jarvis, Michael J. In the Eye of All Trade: Bermuda, Bermudians, and the Maritime Atlantic World, 1680–1783. North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Jeppesen, Jennie. “‘Within the Protection of Law’: Debating the Australian Convict-As-Slave Narrative.” History Australia 16, no. 3 (2019): 534–548. doi:10.1080/14490854.2019.1636674.

- Klein, Martin A. “Slavery, the International Labour Mart and the Emancipation of Slaves in the Nineteenth Century.” In Unfree Labour in the Development of the Atlantic World, edited by Paul E. Lovejoy, and Nicholas Rogers, 197–221. Ilford: Frank Cass, 1994.

- Lydon, Jane. Anti-Slavery and Australia: No Slavery in a Free Land? London: Routledge, 2021.

- MacDougall, Philip. “The Changing Nature of the Dockyard Dispute, 1790–1840.” In History of Work and Labour Relations in the Royal Dockyards, edited by Ken Lunn, and Anne Day, 41–65. London: Mansell, 1999.

- Male Convicts Act: 1823, 4 Geo. IV, c.47.

- Mansfied, Nick. Soldiers as Workers: Class, Employment, Conflict and the Nineteenth-Century Military. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016.

- Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish. “Like Poor Galley Slaves … .’: Slavery and Convict Transportation.” In Legacies of Slavery: Comparative Perspectives, edited by M.S. Fernandes Dias, 48–61. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007.

- Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish. “Transportation from Britain and Ireland, 1615–1875.” In A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies, edited by Clare Anderson, 183–210. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

- McConville, Séan. A History of English Prison Administration: Volume 1, 1750–1877. London: Routledge, 1981.

- McKay, Anna Lois. “‘Allowed to Die’? Prison Hulks, Convict Corpses and the Inquiry of 1847.” Cultural and Social History 18, no. 2 (2021): 163–181. doi:10.1080/14780038.2021.1893917.

- McRorie Higgins, Peter. “The Scurvy Scandal at Millbank Penitentiary: A Reassessment.” Medical History 50, no. 4 (2006): 513–534. PMID: 17066131; PMCID: PMC1592637. doi:10.1017/S0025727300010310.

- Milne, Graeme J. People, Place and Power on the Nineteenth-Century Waterfront. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Mitchel, John. Jail Journal; or, Five Years in British Prisons. New York: Published at the Office of The Citizen, 1854.

- Morgan, Gwenda, and Peter Rushton. Banishment in the Early Atlantic World: Convicts, Rebels and Slaves. London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

- Morgan, Gwenda, and Peter Rushton. Eighteenth-Century Criminal Transportation: The Formation of the Criminal Atlantic. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Morning Chronicle. ‘Millbank Penitentiary’. 14 July 1823.

- Nicholas, Stephen, and Peter R. Shergold. “Transportation as Global Migration.” In Convict Workers: Reinterpreting Australia’s Past, edited by Stephen Nicholas, 28–43. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.