ABSTRACT

Two-sided markets are characterised by the presence of an intermediary and two groups of end-users. In the cruise market, cruise lines may play the role of intermediaries to connect the two end-users, viz. cruise passengers and cruise ports. Our research explored whether the cruise industry can be regarded as a two-sided market, starting with a theoretical modelling. The findings show that cruise lines might be hybrid intermediaries, selling their own ship-based products and services, while offering also a platform to enable the transaction between cruise passengers and cruise ports. This particular business model of a quasi-two-sided market is also reflected in the pricing scheme of cruise industry, whereby cruise ports charge an entry fee from cruise lines and port dues from cruise passengers. We illustrate an empirical analysis on the basis of the cruise market in Japan, and it provides a preliminary clue that the behaviours of cruise ports and cruise lines are consistent with our theoretical framework. The results are not convincingly significant due to data limitations, hence, the concept of a ‘two-sided market’ in the cruise industry call for further empirical research.

1. Introduction

Tourism is a multifaceted market, in which the tastes of visitors determine not only the rise and decline of tourist destinations characterized by differences in natural amenities, cultural heritage, arts, entertainments, and sports facilities, but also the travel modes used. As well as travel by road, rail, and air, in recent years, we have observed the rapidly rising popularity of cruise tourism. The revitalization of travel by cruise ships is a striking phenomenon that ties in with the need for relaxed and varying tourist flows to interesting coastal places. Cruise tourism has been recognized as the fastest-growing category in the leisure travel market, with an average annual passenger growth rate of approximately 7.2%. Cruise Line International Association (Citation2015) showed that cruising has contributed $1.99 billion of direct tourist expenditure, generated 45,225 jobs, and provided $728.1 million in wage income to the residents of cruise port cities.

If we trace the origin of the modern cruise industry back to the 1980s, we would find that the big success of the cruise economy is attributed to the cruise lines’ performance. Based on the theory of two-sided markets (Rochet and Tirole Citation2002; Armstrong Citation2006; Rysman Citation2007; Li Citation2015), our research aims to explore and identify a two-sided cruise market concept in cruise industry, while it further analyses the empirical structure of the cruise industry by applied statistical modelling.

As Cruise Line International Association (Citation2014) reported, there are in total 52 cruise ships offering a total of 1065 separate cruise products, 9 of which were all-year-round in the Asian markets in the year 2015; by then, in total, the cruise capacity had reached 2.17 million passengers, with 2.05 million passengers on ‘Asia-Asia cruises’ and 0.12 million on ‘Voyages sailing through Asia’, which means 94.47% of these cruise passengers will be primarily from Asia. In the past, cruise tourists used to be regarded as the ‘happy few’ senior segment of consumers, but nowadays cruise lines are switching from pure luxury to both upper and middle-priced market segments as well, in order to attract lower budget tourists. As the research of Florida-Caribbean Cruise Association (Citation2014) shows, the average age of cruise passengers has fallen from 65 to 49 years. These customers have also other personal characteristics, such as being college-educated, full-time employed, and having an average annual salary of US$114,000. According to Chen et al. (Citation2016), the Asian cruise markets are significantly different from most mature markets in Europe and North America, in terms of various demands, customer value, and the willingness-to-pay of regional cruise tourists.

On the basis of concepts from two-sided markets theory and previous research on Asian cruise markets, we aim to explore the relevance of the two-sided markets concept for cruise economics and the structure of Asian cruise markets. There are three main questions on which we focus in our research: (a) Is the cruise market a two-sided market?; (b) If so, what is the structure of the Asian cruise market?; and (c) How do two-sided markets actually function in Asian and more specifically, Japanese cruise markets? In this research, we focus on modelling the features of two-sidedness in Asian cruise markets. Findings on the so-called hybrid platforms and quasi-two-sided markets in the cruise industry, may help improve the strategies of the cruise lines’ itineraries and the policy making of cruise ports to attract more cruise ship visits.

The present paper is organised as follows. First, we offer a literature review in Section 2, which leads to the research framing of two-sided markets. The subsequent Section 3 then theoretically analyses the two-sided markets in the cruise industry, followed by an empirical exploratory analysis of the Japanese case in Section 4. The final section provides a discussion and conclusion.

2. Two-sided markets

2.1. Theoretical background

In the past few decades, two-sided markets have become a focal point of research in usually industrial economics. The feature of such markets, viz. two-sidedness, was first identified in early meso-economic research of the media market. A two-sided market is a specific type of market, but there is no precisely established definition. Most studies identified in the prevailing research on two-sided markets are based on indirect network effects or the pricing structure, focussing on the actions of the market intermediary.

Starting from the 1950s, Corden (Citation1952-1953) analysed the profits of two-sided end-users, viz. newspaper sales to readers and the sale of advertising space to firms. The term ‘two-sided markets’ concept was first used by Rochet and Tirole (Citation2002) in the context of payment cards. Then, Rochet and Tirole (Citation2003) extended the ‘two-sided markets’ model of payment cards to a general model of platform competition in two-sided markets, by addressing the specification of the agents’ utility, the structure of the platforms’ fees, a subscription charge in the event of a successful match, or a negative subscription charge with profits from taxing transactions on the platforms. Later on, Armstrong (Citation2006) developed three theoretical models of two-sided markets and the main determinants of equilibrium, viz. price externalities, transaction fees, and number of accessible platforms. Rysman (Citation2004) mentioned that two-sidedness might to some extent exist in all markets, but the question is how important the two-sided issue is in determining the outcomes of real interest.

The definition of two-sided markets is very broad, and it raises the interesting question of whether or when a market can be defined as two-sided. In our research, we start from a firm (cruise line) acting as a platform to link the two sides of end-users (cruise tourists and cruise ports). The transaction between cruise tourists and cruise ports is also significantly influenced by the cruise lines’ duration of stay in ports, shore itineraries, etc.

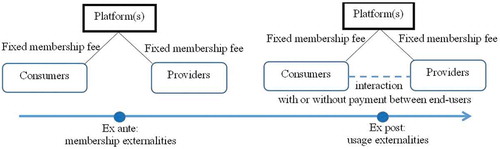

2.2. The platform of two-sided markets

A core feature of two-sided markets is the existence and functioning of an intermediary, viz. the platform. In the previous contribution of Rochet and Tirole (Citation2002; Citation2003; Citation2006), Evans (Citation2003), Armstrong (Citation2006), and Weyl (Citation2010), the platform in two-sided markets appears to have three main characteristics: (a) they are multi-product firms which provide distinct products to the two sides of the market; (b) users’ benefits on the platform depend on how well the platform performs on the other side of the market; and (c) platforms are price setters on both sides of the market. Damiano and Li (Citation2008) argued that matching markets are two-sided, in the sense that the matching ‘platform’ is more attractive as more participants sign up. shows how platforms function in two-sided markets.

Figure 1. Two-sided markets (Rochet and Tirole Citation2006).

The literature on two-sided markets is distinguished by its focus on the actions of the market platform. In order to provide a precise classification, Evans (Citation2003) identified three main types of two-sided markets: (a) Market-Makers, which enable different groups to transact with each other, such as shopping malls and eBay; (b) Audience-Makers, which match advertisers to audiences, for instance, newspapers, television, Google, etc; and (c) Demand-Coordinators, which provide goods or services to generate indirect network effects across two or more groups, like payment cards and software. In a subsequent review paper, Rochet and Tirole (Citation2006) argue that a market is two-sided if the platforms can affect the volume of transactions by charging more to the one side of the market and reducing by an equal amount the price being paid by the other side.

In two-sided markets, platforms play a big role in the transaction between the two end-users, viz. the consumers and the providers. As intermediaries, the revenue of platforms depends on their business model, such as membership charge, transaction fee, or trading their own products. It is noteworthy that there is a variety of intermediaries in two-sided markets, which are not extremely merchant-oriented or platform-based but fall in between.

2.3. The features of two-sided markets

Evans (Citation2003) presented three necessary conditions for the existence of two-sided markets: (a) they have two or more distinct groups of customers; (b) they exhibit externalities being associated with two-sided end-users; and (c) there is an intermediary internalising the externalities created by two-sided end-users. Rochet and Tirole (Citation2006) further stated three types of costs, viz. transaction costs among end-users, platform-imposed pricing constraints between end-users, and fixed membership fees. Hagiu (Citation2009) discussed two strategies of market intermediation (merchant mode and two-sided platform mode) and the pricing structures of two-sided markets’ platforms, in order to estimate the factors which drive two-sided platforms’ non-price governance rules to restrict access beyond what they can achieve through pricing alone. Lin, Wu, and Zhou (Citation2016) examined the two-sided pricing strategy of a platform, and found that it depends on the two sides’ demand elasticity and network effects, while it might also be influenced by entry fee and subsidy.

Moreover, two-sidedness is essentially also an empirical issue, and this is the focal point in current research on two-sided markets. Some relevant empirical studies address typical two-sided platforms, such as shopping malls (Brueckner Citation1993), magazines (Kaiser and Wright Citation2006; Kaiser and Song Citation2009), payment cards (Rysman Citation2007), airports (Ivaldi, Sokullu, and Toru Citation2011), and newspapers (Argentesi and Filistrucchi Citation2007; Behringer and Filistrucchi Citation2015). Also in recent years, two-sided markets have gained improvement in empirical studies. Boik (Citation2016) examined the effect of platforms and their pricing externality in two-sided markets in the US cable television industry. Elorantaa and Turunenb (2016) discussed how the platforms of service-driven manufactures are used in the complex inter-organizational networks.

3. The two-sided markets in the cruise industry

3.1. The structure of the cruise industry

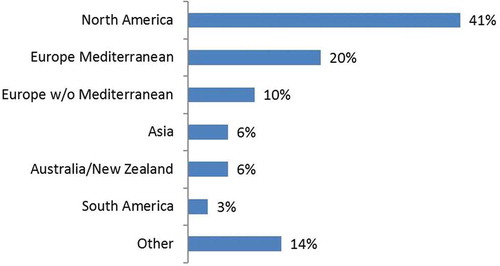

In the cruise industry, cruise lines, cruise ports, and cruise tourists are regarded as the three main stakeholders. Since the 1980s, the success of modern cruise industry has been led by North America (see ), and more than half of the cruise tourists are sourced from that region. The Asian markets accounted for a minor share of 6% in 2015, but there is a big potential for more development and scope for an optimistic estimation of the share in the near future.

Figure 2. Market percentage of international cruise lines (CLIA, Citation2015).

As suppliers, cruise ports can be regarded as public firms, which aim to optimize the economic effects of port cities. The cruise ports in North America are very successful, and they account for 37.3% of all global itineraries in 2014 (CLIA Citation2015). In addition, there are 30 cruise ports in North America, and 10 of them are ranked as the most popular cruise ports in the world. They provide unprecedented convenience, cost savings, and value by placing cruise ships within driving distance of their customers, which means 75% of the North American cruise tourists can drive to cruise ports.Footnote1 The experience of North America is a good example of how to develop more cruise ports in Asia, which will also benefit the economy of cruise port cities. Meanwhile, the increase of cruise ports in Asia is challenging the cruise lines’ optimization, while Asian cruise ports are also confronted with fierce competition within their own country.

3.2. Research in the cruise market

In contrast to the rapid progress of the cruise industry, the relevant research in the field of cruise market is not as abundant as it should be. Since the 1980s, the significant growth of the modern cruise industry has encouraged some researchers to focus on the cruise economy in the Caribbean and the US (Miller Citation1985; Lawton and Butler Citation1987; Hall and Braithwaite Citation1990; Hobson Citation1993), offering some applied qualitative and descriptive quantitative analyses. Later, however, econometric models were increasingly used, such as cruise economic impact studies (Chase and Alon Citation2002), cruise taxing (Mak Citation2008), cruise revenue optimization (Sun, Jiao, and Tian Citation2011), and cruise externalities (Brida et al. Citation2012). The regional economists argued that the economic effects of cruise industry are the main motivation for developing cruise ports (Mescon and Vozikis Citation1985; Jordan Citation2013; Penco and Vaio Citation2014), while there is also some relevant research about cruise ports’ stakeholders (Lester and Weeden Citation2004; Brida et al. Citation2014; Wang et al. Citation2014). In recent decades, the cruise industry has developed into a flourishing and well-dominated market with the top-3 cruise lines having an 83% share and there is also a substantial volume of research on cruise industrial organization (Coleman, Meyer, and Scheffman Citation2003; Wie Citation2005).

Particularly in the Asian markets, there is comparatively more empirical research on the consumer behaviour of cruise tourists, such as their motivation, satisfaction, and intention (Qu and Ping Citation1999; Hung and Petrick Citation2011; Fan and Hsu Citation2014), expenditure (Hyun and Han Citation2015; Lee and Lee Citation2017), and market segmentation (Xie, Kerstetter, and Mattila Citation2012). In this context, the Asian cruise passengers’ willingness-to-pay and customer value were examined (Chen, Zhang, and Nijkamp Citation2016; Neuts, Chen, and Nijkamp Citation2016). Based on the Taiwan market, Chen (Citation2016) explored six related factors in the cruise industry, viz. regulations, onboard service, port facilities, international promotion, cooperation with neighbouring countries, and attractions in port cities.

Generally, studies in cruise economics are few and widely scattered. They also lack systematic frameworks. Actually, the relationships between the three main stakeholders, viz. cruise lines, cruise ports, and cruise tourists, are usually ignored in the current research. Therefore, more relevant theories and models should be developed in order to build a comprehensive cruise research scheme, and also to interpret cruise economics in more depth, which would benefit the theory of cruise economics and the practice of the cruise industry.

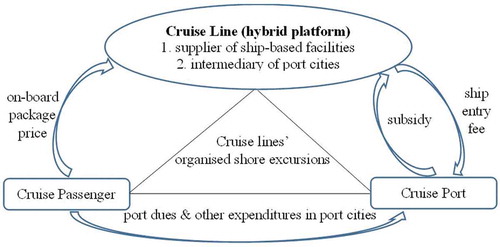

3.3. Clarification of the ‘platform’ of the cruise market

Cruise lines are not pure itineraries between cruise passengers and cruise ports, since they also provide ship-based products and services and port-based shore itineraries. From the theoretical conditions of two-sided markets, cruise lines are hybrid platforms: (a) cruise lines offer different cruise routes with various ports to cruise passenger and take many cruise passengers to visit port cities; (b) there is a transaction between cruise passengers and cruise ports, connecting via cruise lines, and also influenced by the cruise lines’ duration of the stay in ports; and (c) cruise lines have to pay to cruise ports entry fees (Baird Citation1997), and they might get some subsidy depending on how many passengers they bring and the frequency of port visits. This reversed payment from cruise lines to cruise ports might be explained by scarce resources, such as port-city views, local attractions, hinterland tourists resource, etc. And it can also be explained by the hybrid cruise platform, when the cruise line plays the role of Demand-Coordinator, providing products and services to enrich its cruise itinerary.

In order to understand the nature of the cruise market, we will clarify the business mode of cruise lines. As shore itinerary suppliers, cruise ports get access to cruise lines’ platforms firstly and then they transact with the cruise tourists during the cruise lines’ stay in ports. Meanwhile, cruise lines are able to influence the demand of cruise tourists for the cruise ports by transaction time and pricing scheme. Given the earlier arguments, the cruise market satisfies some basic requirements of two-sided markets though not precisely, so the cruise quasi-two-sided market can be identified in .

3.4. Assessment of the two-sided nature of the cruise market

In the cruise market, cruise lines play the role of hybrid intermediaries, selling their own products onboard and also providing platforms to connect cruise tourists and cruise ports. So, the cruise passengers’ demand is influenced by cruise lines, so that the inverse demand function of the cruise passengers can be written as

where P is the price of the cruise travel package; a is the highest willingness-to-pay of a passenger; and Q is the number of passengers.

We will now offer a stylized representation of the behaviour of cruise ports, cruise lines, and cruise passengers. A cruise port achieves its economic benefits from entry fees and port dues paid by a cruise line, so that the net benefit of a cruse port (B) can be written as

where pa is the net payment per passenger to the cruise port; ca is the cost of a passenger in the cruise port; and f(Q) is the economic effects of cruise passengers’ expenditures in the port city.

The profit of a cruise line is as follows

where Π is the profit of a cruise line; c is the onboard cost of a passenger; is the net profit of a cruise line as a result of providing add-on products and services (e.g. onboard duty free shops and shore itineraries); f is the subsidy a cruise line might get from ports.

In order to identify the nature of the cruise market, our theoretical modelling is conducted in two ways, viz. a vertical market and a two-sided market. A comparison of these theoretical results will help for a further empirical test on the nature of the cruise market.

(a) A vertical market

In a general vertical market, cruise ports are suppliers of cruise lines. Taking into account the maximised profits of a cruise line, we now determine the optimal price . From the inverse demand function of cruise passengers, we substitute the price

, so that the first-order condition with respect to

yields

Hence, substituting the number of passengers , the optimal economic effects of a cruise port can be calculated by the first-order condition as follows:

From Equations (2) and (4): max

from Equations (4) and (5):

(b) A two-sided market

We will now examine the position of a cruise line in the context of a two-sided market. Pricing under a two-sided market structure implies that cruise lines consider revenues from both sides, that is, from cruise passengers and cruise ports. In order to maximize the profits of a cruise line, we formulate the first-order condition to the target function of a cruise port and the profit function of a cruise line with respect to as follows:

From Equations (1)–(3): max

With respect to , the first-order condition of the profit function of a cruise line is negative, so that the profit of a cruise line decreases as follows:

So, a corner solution exists that satisfies the profit maximization of a cruise line, written as

from Equations (4) and (8):

Consequently, the net payment to a port is different under a vertical market and a two-sided market. For a further comparison of and

, we need the value of appropriate estimators. The necessary data for an empirical test refer to the highest willingness-to-pay of a passenger (a), the onboard cost of a cruise line for per passenger(c), the service cost of a cruise port for per passenger (ca), the net profit of a cruise line as a result of providing add-on products and services (e), the subsidy a cruise line might get from cruise ports (f), and the economic effects on the cruise port

. The theoretical model constructed here would need a rigorous empirical test in order to assess its relevance in a two-sided market context.

4. Implications for the Asian cruise markets

In the mature Mediterranean cruise markets, cruise industry is considered as a stimulator of port regions (Gui and Russo Citation2011), so that Asian cruise port authorities try to attract cruise ships’ visits. Furthermore, the frequency and duration of cruise ships’ visits are influenced by the cruise port cities’ attractiveness, including their infrastructure, commercial facilities, and tour attractions, and networks with other neighbouring ports (Notteboom and Winkelmans Citation2001; Notteboom and Rodrigue Citation2005). Since cruise ports in the same region are connected by cruise lines, one port’s action will affect – or be affected by – other neighbouring ports, in particular the home ports.

In order to make a provisional test of the two-sided concept in cruise industry, we used the Japanese cruise market as an empirical illustration. Firstly, from the demand side, the Japanese cruise market is considered to have the highest willingness to pay compared to other Asian markets (Chen et al., Citation2016b); Secondly, from the platform side, Japan has hosted both international cruise lines and regional cruise lines; Thirdly, from the supplier side, Japan itself is a typical archipelago country with about 135 passenger ports.

In our research, we have analysed passenger ship visits between 2009 and 2015; they showed that Yokohama is the biggest port with 8466 passenger ship visits. In particular, the Yokohama harbour bureau introduced an incentive programme from March 2012 onwards, particularly as far as the charges for wharfage and water supply are concerned (). Therefore, we have used Yokohama for further analysis, aiming to identify whether the cruise port’s charge influences the cruise lines’ decision, for instance, by visiting cruise ports over a period of 24 h. In the two-sided market concept, this can be regarded as the transaction time between the two end-users of cruise tourists and cruise ports. It is obvious that the incentive programme of cruise ports is a type of subsidy to cruise lines.

Table 1. The incentive programme of Yokohama port.

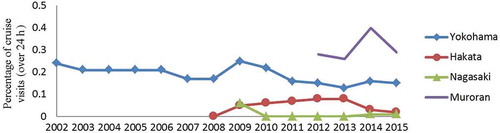

For a better understanding of the influence of Yokohama port incentive programme, we conducted a comparative analysis with three other selected typical Japanese ports (Hakata, Nagasaki, Muroran), by mainly focusing on cruise lines’ duration of stay in ports. Firstly, these three ports are located from the North to the South of the country, as the map in shows. In addition, these three ports are identified as ports of call for both Japanese regional cruise lines and international cruise lines. shows the number of cruise ship visits and the percentage of cruise ship visits of more than 24 h duration of stay in the four Japanese ports, viz. Yokohama, Hakata, Nagasaki, and Muroran.

Table 2. Summary of cruise ship visits to Japanese cruise ports (over 24 h).

shows some fluctuations in the percentage of cruise visits with over 24 h duration of stay. Compared to Yokohama port, the percentage of cruise visits with a duration of over 24 h after 2012 declined for Hakata, rose for Nagasaki, and dramatically increased, and then dropped for Muroran.

Regarding the negative influence of the serious earthquake in east Japan and the Fukushima nuclear radiation in 2011, the stable percentage of cruise visits with a duration of 24 h in Yokohama after 2011 seems to indicate that the incentive programme may have prevented a decrease in the percentage of ships visiting Yokohama for a longer period, although it is beyond the quality of our data to verify this explanation. For a firm conclusion regarding the influence of cruise ports’ subsidy on cruise lines, we need more empirical data for estimating the effects of incentive programmes from more cruise ports.

It should be noted that our tentative statistical analysis has only used a limited set of characteristics of the cruise industry as a two-sided market concept. Some important indicators should be provided, viz. the cruise passengers’ willingness-to-pay, the cruise lines’ onboard cost for per passenger, the cruise lines’ profits from add-on products and services, the subsidy a cruise port might provide to cruise lines, and the cruise passengers’ expenditure in a cruise port. This means that we could only pursue a partial test and draw partial conclusions related to a hybrid platform and a quasi-two-sided market. Consequently, our findings have to be interpreted with caution.

5. Conclusion

This paper has demonstrated the relevance of two-sided markets in the cruise industry using a conceptual approach, in order to clarify the interdependent framework of cruise passengers, cruise lines, and cruise ports. From the perspective of two-sided markets, cruise lines play the role of hybrid platforms, being suppliers of ship-based products and services, and also connecting cruise passengers and ports as intermediaries of port-based shore itineraries. So, the cruise market cannot be regarded as a typical two-sided market.

In our theoretical research, a hybrid platform and a quasi-two-sided cruise market are identified, though some estimators are not available for further empirical tests, such as the cruise passengers’ highest willingness-to-pay, the cruise line’s onboard cost for per passenger, the net profit of a cruise line’s add-on products and services, the service cost for per passenger in a cruise port, and the cruise port’s economic effects. Given that subsidy is widely provided by cruise ports in the emerging Asian cruise markets, the theory of two-sided markets helps to further understand the nature of cruise industry and the relationship between cruise lines, cruise passengers, and cruise ports.

In recent research by Chen et al. (Citation2016a), the authors have argued that cruise passengers are not conventional tourists, as they are characterized by a specific demand for ship-based products and services and port-based shore itineraries. So, cruise lines play dual roles as hybrid platforms, being suppliers of ship-based products and services and also serving as cruise ports’ itineraries. We have explored whether, and how, a two-sided market functions in the cruise industry. Our theoretical research proves that a quasi-two-sided market and a hybrid platform are identified in cruise industry, particularly in those emerging Asian cruise markets which have a subsidy policy provided by cruise ports. In our subsequent empirical test, some estimators were currently not available, so that we had to focus on the effect of the subsidy policy of the Yokohama cruise port. Due to the serious earthquake in east Japan and the occurrence of nuclear radiation in Fukushima in 2011, the subsidy policy provided by Yokohama port starting from March 2012 has not produced a convincing result.

For future research, the cruise lines’ decision-making regarding a port selection should also consider the cruise port cities’ attractiveness and seasonality (Esteve-Perez and Garcia-Sanchez Citation2017), which gives cruise ports some bargaining power to enable them to utilize the cruise lines’ platform. The cruise ports’ bargaining power influences their market size (number and frequency of cruise ship visits) and transaction time (cruise lines’ duration of stay). Hence, solid empirical research will need extensive information on the port cities’ competitiveness and the process of the cruise lines’ decision-making.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank two anonymous referees and the editors for their valuable input in revising the paper. We are also grateful to Jesper de Groote, Erik T. Verhoef, and port authorities in Japan for suggestions and assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. 2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Miami-Dade Seaport Department, Florida.

References

- Argentesi, E., and L. Filistrucchi. 2007. “Estimating Market Power in a Two-Sided Market: The Case of Newspapers.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 22 (7): 1247–1266. doi:10.1002/jae.997.

- Armstrong, M. 2006. “Competition in Two-Sided Markets.” RAND Journal of Economics 37 (3): 668–691. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2171.2006.tb00037.x.

- Baird, A. J. 1997. “An Investigation into the Suitability of an Enclosed Seaport for Cruise Ships the Case of Leith.” Maritime Policy & Management 24 (1): 31–43. doi:10.1080/03088839700000054.

- Behringer, S., and L. Filistrucchi. 2015. “Hotelling Competition and Political Differentiation with More than Two Newspapers.” Information Economics and Policy 30: 36–49. doi:10.1016/j.infoecopol.2014.10.004.

- Boik, A. 2016. “Intermediaries in Two-Sided Markets: An Empirical Analysis of the US Cable Television Industry.” American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 8 (1): 256–282. doi:10.1257/mic.20140167.

- Brida, J. G., G. D. Chiappa, M. Meleddu, and M. Pulina. 2012. “Cruise Tourism Externalities and Residents’ Support: A Generalized Ordered Logit Analysis.” Economics Discussion Paper. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1994246

- Brida, J. G., G. D. Chiappa, M. Meleddu, and M. Pulina. 2014. “A Comparison of Residents’ Perceptions in Two Cruise Ports in the Mediterranean Sea.” International Journal of Tourism Research 16 (2): 180–190. doi:10.1002/jtr.1915.

- Brueckner, J. K. 1993. “Inter-Store Externalities and Space Allocation in Shopping Centers.” Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economic. 71:5–16. Retrieved from. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01096932

- Chase, G., and I. Alon. 2002. “Evaluating the Economic Impact of Cruise Tourism: A Case Study of Barbados.” Anatolia 13 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/13032917.2002.9687011.

- Chen, C.-A. 2016. “How Can Taiwan Create a Niche in Asia’s Cruise Tourism Industry?” Tourism Management 55: 173–183. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2016.02.015.

- Chen, J. M., B. Neuts, P. Nijkamp, and J. Liu. 2016a. “Demand Determinants of Cruise Tourists in Competitive Markets: Motivation, Preference, and Intention.” Tourism Economics 22 (2): 227–253. doi:10.5367/te.2016.0546.

- Chen, J. M., J. Zhang, and P. Nijkamp. 2016b. “A Regional Analysis of Willingness-To-Pay in Asian Cruise Markets.” Tourism Economics 22 (4): 809–824. doi:10.1177/1354816616654254.

- Coleman, M. T., D. W. Meyer, and D. T. Scheffman 2003. “Economic Analyses of Mergers at the FTC: The Cruise Ships Mergers Investigation.” Review of Industrial Organization, 23:121–155. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023%2FB%3AREIO.0000006910.18832.0e?LI=true

- Corden, W. M. 1952-1953. “The Maximisation of Profits by a Newspaper.” The Review of Economic Studies. 20 (3): 181–190. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2295888

- Cruise Line International Association (CLIA). 2014. “Asia Cruise Trends.” 13 May 2015. Retrieved from http://www.cruising.org/docs/defaultsource/research/asiacruisetrends_2014_finalreport-4.pdf?sfvrsn=2

- Cruise Line International Association (CLIA). 2015. “Cruise Industry Outlook.”10 March 2015. Retrieved from http://www.cruising.org/docs/default-source/research/2015-cruise-industry-outlook.pdf

- Damiano, E., and H. Li. 2008. “Competing Matchmaking.” Journal of the European Economic Association 6 (4): 789–818. doi:10.1162/JEEA.2008.6.4.789.

- Elorantaa, V., and T. Turunenb. 2006. “Platforms in Service-Driven Manufacturing: Leveraging Complexity by Connecting, Sharing, and Integrating.” Industrial Marketing Management 55: 178–186. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.10.003.

- Esteve-Perez, J., and A. Garcia-Sanchez. 2017. “Characteristics and Consequences of the Cruise Traffic Seasonality on Ports: The Spanish Mediterranean Case.” Maritime Policy & Management 44 (3): 358–372. doi:10.1080/03088839.2017.1295326.

- Evans, D. S. 2003. “The Antitrust Economics of Multi-Sided Platform Markets.” Yale Journal on Regulation. 202:325–381. Retrieved from. http://aei.brookin~s.ore/admin/~dffiles

- Fan, D. X. F., and C. H. C. Hsu. 2014. “Potential Mainland Chinese Cruise Travelers’ Expectations, Motivations, and Intentions.” Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 31 (4): 522–535. doi:10.1080/10548408.2014.883948.

- Florida-Caribbean Cruise Association (FCCA). 2014. “Cruise Industry Overview.” 18 April 2014 Retrieved from http://www.f-cca.com/downloads/2014-Cruise-Industry-Overview-and-Statistics.pdf

- Gui, L., and A. P. Russo. 2011. “Cruise Ports: A Strategic Nexus between Regions and Global Lines—Evidence from the Mediterranean.” Maritime Policy & Management 38 (2): 129–150. doi:10.1080/03088839.2011.556678.

- Hagiu, A. 2009. “Two-Sided Platforms: Product Variety and Pricing Structures.” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 18 (4): 1011–1043. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9134.2009.00236.x.

- Hall, J. A., and R. Braithwaite. 1990. “Caribbean Cruise Tourism: A Business of Transnational Partnerships.” Tourism Management 11 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1016/0261-5177(90)90069-L.

- Hobson, J. S. P. 1993. “Analysis of the US Cruise Line Industry.” Tourism Management 14 (6): 453–462. doi:10.1016/0261-5177(93)90098-6.

- Hung, K., and J. F. Petrick. 2011. “Why Do You Cruise? Exploring the Motivation for Taking Cruise Holidays, and the Construction of a Cruise Motivation Scale.” Tourism Management 32 (2): 386–393. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.008.

- Hyun, S. S., and H. Han. 2015. “Luxury Cruise Travelers: Other Customer Perceptions.” Journal of Travel Research 54 (1): 107–121. doi:10.1177/0047287513513165.

- Ivaldi, M., S. Sokullu, and T. Toru 2011. “Airport Prices in a Two-Sided Framework: An Empirical Analysis.” Working Paper, Toulouse School of Economics. Retrieved from http://idei.fr/sites/default/files/medias/doc/conf/csi/papers_2011/ivaldi.pdf

- Jordan, L. A. 2013. “A Critical Assessment of Trinidad and Tobago as A Cruise Homeport: Doorway to the South American Cruise Market?” Maritime Policy & Management 40 (4): 367–383. doi:10.1080/03088839.2013.777980.

- Kaiser, U., and M. Song. 2009. “Do Media Consumers Really Dislike Advertising? an Empirical Assessment of the Role of Advertising in Print Media Markets.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 27 (2): 292–301. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2008.09.003.

- Kaiser, U., and J. Wright. 2006. “Price Structure in Two-Sided Markets: Evidence from the Magazine Industry.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 24 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2005.06.002.

- Lawton, L. J., and R. W. Butler. 1987. “Cruise Ship Industry—Patterns in the Caribbean 1880-1986.” Tourism Management 8 (4): 329–343. doi:10.1016/0261-5177(87)90091-4.

- Lee, G., and M. K. Lee. 2017. “Estimation of the Shore Excursion Expenditure Function during Cruise Tourism in Korea.” Maritime Policy & Management 1–11. doi:10.1080/03088839.2017.1298866.

- Lester, J.-A., and C. Weeden. 2004. “Stakeholders, the Natural Environment and the Future of Caribbean Cruise Tourism.” International Journal of Tourism Research 6 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1002/jtr.471.

- Li, J. 2015. “Is Online Media a Two-Sided Market?” Computer Law & Security Review 31 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2014.11.001.

- Lin, M., R. Wu, and W. Zhou. 2016. “Two-Sided Pricing and Endogenous Network Effects.” Social Science Electronic Publishing, Research Collection School of Information Systems. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2426033.

- Mak, J. 2008. “Taxing Cruise Tourism: Alaska’s Head Tax on Cruise Ship Passengers.” Tourism Economics 14 (3): 599–614( 16). doi:10.5367/000000008785633613.

- Mescon, T. S., and G. S. Vozikis. 1985. “The Economic Impact of Tourism at the Port of Miami.” Annals of Tourism Research 12 (4): 515–528. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(85)90075-1.

- Miller, W. H. 1985. “The US Cruise Ship Industry.” Journal of Geography 84 (5): 199–204. doi:10.1080/00221348508979132.

- Neuts, B., J. M. Chen, and P. Nijkamp. 2016. “Assessing Customer Value in Segmented Cruise Markets: A Modelling Study on Japan and Taiwan.” Academy of Marketing Studies Journal 20 (3): 1–13.

- Notteboom, T. E., and J.-P. Rodrigue. 2005. “Port Regionalization: Towards a New Phase in Port Development.” Maritime Policy & Management 32 (3): 297–313. doi:10.1080/03088830500139885.

- Notteboom, T. E., and W. Winkelmans. 2001. “Structural Changes in Logistics: How Do Port Authorities Face the Challenge?” Maritime Policy & Management 28 (1): 71–89. doi:10.1080/03088830119197.

- Penco, L., and A. D. Vaio. 2014. “Monetary and Non-Monetary Value Creation in Cruise Port Destinations: An Empirical Assessment.” Maritime Policy & Management 41 (5): 501–513. doi:10.1080/03088839.2014.930934.

- Qu, H., and E. W. Y. Ping. 1999. “A Service Performance Model of Hong Kong Cruise Travelers.’ Motivation Factors and Satisfaction.” Tourism Management 20 (2): 237–244. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00073-9.

- Rochet, J.-C., and J. Tirole. 2002. “Cooperation among Competitors: Some Economics of Payment Card Associations.” The RAND Journal of Economics. 33 (4): 549–570. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3087474

- Rochet, J.-C., and J. Tirole. 2003. “Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets.” Journal of the European Economic Association 1 (4): 990–1029. doi:10.1162/154247603322493212.

- Rochet, J.-C., and J. Tirole. 2006. “Two-Sided Markets: A Progress Report.” The RAND Journal of Economics 37 (3): 645–667. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2171.2006.tb00036.x.

- Rysman, M. 2004. “Competition between Networks: A Study of the Market for Yellow Pages.” Review of Economic Studies 71 (2): 483–512. doi:10.1111/0034-6527.00512.

- Rysman, M. 2007. “An Empirical Analysis of Payment Card Usage.” The Journal of Industrial Economics 55 (1): 483–512. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6451.2007.00301.x.

- Sun, X., Y. Jiao, and P. Tian. 2011. “Marketing Research and Revenue Optimization for the Cruise Industry: A Concise Review.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 30 (3): 746–755. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.11.007.

- Wang, Y., K.-A. Jung, G.-T. Yeo, and -C.-C. Chou. 2014. “Selecting A Cruise Port of Call Location Using the Fuzzy-AHP Method: A Case Study in East Asia.” Tourism Management 42: 262–270. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.11.005.

- Weyl, E. G. 2010. “A Price Theory of Multi-Sided Platforms.” The American Economic Review 100 (4): 1642–1672. doi:10.1257/aer.100.4.1642.

- Wie, B.-W. 2005. “A Dynamic Game Model of Strategic Capacity Investment in the Cruise Line Industry.” Tourism Management 26 (2): 203–217. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.020.

- Xie, H., D. L. Kerstetter, and A. S. Mattila. 2012. “The Attributes of a Cruise Ship that Influence the Decision Making of Cruisers and Potential Cruisers.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 31 (1): 152–159. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.03.007.