Abstract

The context of child prosthetics is a complex and important area for research and innovation. Yet, like many areas of paediatric medical technology development, there are several barriers to innovating specifically for the unique needs of children (i.e., a relatively small patient population or ‘market’). As such, much child prosthetics technology is developed from the downsizing of adult prosthetics, leading to suboptimal outcomes for children and young people. Since 2016, the Starworks Child Prosthetics Research Network has been exploring this space, bringing children and their families together with key opinion leaders from the NHS, clinical Academia and leading National Research Centres with capabilities in child prosthetics with the aim of increasing research across the system. Above all else, Starworks is centred on the needs of children and their families, ensuring they have an equal voice in driving the ongoing research agenda. This article will share key learnings from the creation and development of the Starworks Network that may be applicable and/or adaptable across a wider paediatric medical technology research and innovation landscape. In particular it will discuss how it addressed three key aims of; (1) Addressing child-specific issues; (2) Building a sustainable network; and (3) Fostering impactful innovation.

1. Introduction

Approximately 2000 children in the UK experience a form of limb difference [Citation1], either through congenital conditions (such as fibular hemimelia, Adams-Oliver Syndrome and congenital upper limb transverse limb deficiency), which may require amputation of the affected limb at an early age, or through traumatic causes (such as car incidents), or illness (such as meningitis or sepsis). Many of these children will go on to use a prosthetic limb, but often encounter a variety of challenges in finding a prosthetic that allows them to live as freely and healthily as their peers and siblings. These include:

Size considerations

Continuously changing anatomy and physiology

Testing - small numbers can make it difficult, costly and time consuming to run trials

Complicated regulatory approval.

In prosthetics, children’s constant growth and change results in increased prosthetic limb redundancy and a higher turnover than general wear and tear [Citation2].

In response to this, in 2016, the UK government committed £1.5 million to support new innovations for children with limb loss. This funding was divided equally between 1) the provision of activity limbs through the NHS, and 2) investment in new innovation to help children with limb loss reach their full potential. The latter provided the funding to launch the NIHR Child Prosthetic Research Collaboration known as The Starworks Network (Starworks). NIHR Devices for Dignity Medtech Co-operative (NIHR D4D) were given the role of leading ‘Starworks,’ due to their track record and focus on clinical areas and themes with high morbidity and unmet needs for NHS patients and healthcare technology users, which have not traditionally benefitted from a high degree of innovation [Citation3]. Now, four years into the programme, it is timely to reflect on successes and key learnings to date.

2. Background

Starworks aims to increase research focus across the ‘system’ of child prosthetics (i.e., across the network of academia, NHS, and industry) in order to accelerate the translation of new inventions and developments in in this area into everyday use. In order to make best use of the government funding, NIHR D4D pump primed the formation of The Starworks Network to bring together four key stakeholder groups- academia, industry, clinical and children and their families, the latter being central to the Starworks project throughout. In this instance, ‘pump priming’ refers to investing the funding in creating a supportive environment for the four key stakeholder groups to explore ideas, project concepts or innovations, that could in turn lead to further research and development, or contribute to larger applications for dedicated research grants.

The Starworks journey is described in detail in Wheeler [Citation4], however for context the key stages included:

Formation of the Starworks Network: This involved recruiting thirty-four experts from the four key stakeholder groups, to ensure multiple perspectives were included in the planning and delivery of Starworks activities.

Needs assessment: An overview of unmet needs in child prosthetics was sought by engaging the four stakeholder groups using methods most appropriate to them (i.e., online surveys addressed clinician’s time-poor working schedules). Children and families were engaged through creative workshops, and bespoke postal questionnaires were developed for children, young adults and parents to support this.

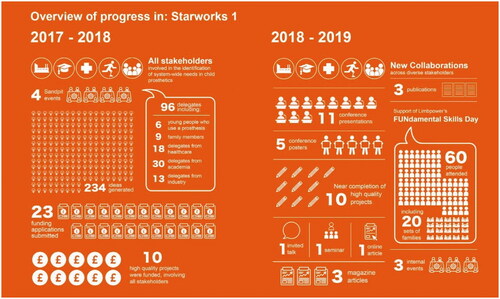

Sandpit events: Four creative, collaborative, multi-stakeholder sandpit events were held across the country, with ninety delegates representing the four key stakeholder groups. Each sandpit was dedicated to a specific theme, including socket fit, upper and lower limb personalisation and adaptation, and digital innovations (all of which emerged from the prior unmet needs assessment). By focussing on creative ways of sharing experiences we were able to gain the priorities and needs for child prosthetic development from each of the different stakeholder groups’ perspectives.

Initial proof of concept funding: In 2017, Starworks put out a national call for applications for up to £50,000 ‘Proof of Concept’ (PoC) funding, focussing on addressing the key challenges within child prosthetics technology. Twenty-three high-quality project proposals were received, all of which addressed at least one of the themes that emerged from the sandpit events. Applications were reviewed by a multidisciplinary panel (including representation from families with experience of child prosthetics) who were asked to consider factors including importance of the unmet need, an appropriate mix of expertise within the project team, and planned engagement with families. Ten projects were awarded funding (a total of £430,000).

Follow on funding: In 2019, a new call for funding was launched by Starworks, which saw six of the PoC projects receiving follow on funding (FoF) to enable them to continue their work in preparation for applying for larger funding applications, thus enhancing the sustainability of research and innovation in this space.

Throughout each of these steps, growth of the Starworks network was also fostered by collaborating and communicating with the key stakeholder groups through means that are best understood and/or accessible to them. For example, whilst academic communities may engage with Starworks via conference presentations, many families can be reached at related charity events (further details are available in ).

Figure 1. Infographic of output metrics and engagement methods for the first two years of Starworks activity.

In order to expand the scope and reach of the Starworks initiative, NIHR Children and Young People MedTech Co-operative (NIHR CypMedTech) became part of the network due to their expertise and capabilities in paediatric medical technology development.

Overall, Starworks had three key aims,

Addressing child-specific issues;

Building a sustainable network

Fostering impactful innovation

As such, this paper will discuss the ways in which these aims were addressed, with a view to the findings of the outputs and learning from this project being adopted to other areas of research

2.1. Addressing child-specific issues

2.1.1. Engaging a variety of stakeholders

In order to identify and address child-specific issues, it is important to make space for a range of relevant perspectives to contribute to a project, and facilitate clear communication between them. Within Starworks, a range of opinions and priorities for research in this space were elicited by considering the insights of clinicians, academics, industry experts, children and families as equally important. This was the first step in developing a shared understanding (between the stakeholder groups) of the everyday, real life issues for children who use prosthetics, and framing these challenges as a concern of the entire family (including siblings and parents).

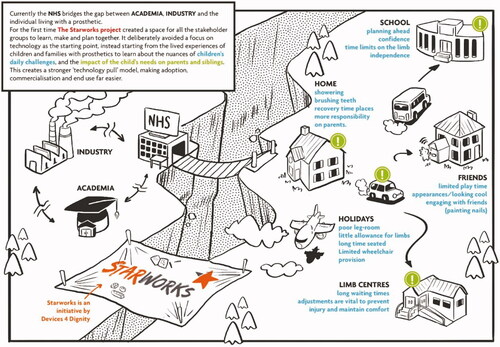

By involving multiple stakeholders together, it became clear that industry & academia often are not aware of these small, but impactful issues that children face. In addition, there (currently) are not many opportunities or funding streams for these stakeholder groups to engage with families in an exploratory way, before an issue/solution is identified, in order to better shape their research agenda. An important role for the Starworks activities, then, was to bridge the gap between these different stakeholder groups, as described further in . Engaging children and families in research and innovation (at any stage of the project) can be challenging, but the rich insights generated in the Starworks initial needs assessments (also detailed in ) demonstrated how valuable and necessary this is.

2.1.2. Taking a creative approach to engagement

Considering the diversity of perspectives within the network (i.e., academics, industry healthcare and families), additional expertise was sought to address potential challenges that could arise in this initial needs assessment, and beyond. For example, power differences between members of different stakeholder groups (i.e., a parent may not feel able to question the opinion of an orthopaedic surgeon during sandpit activities), varying preferences in communication styles (i.e., children may disengage from verbal-only communication), the need to build trust between diverse stakeholder groups, and the complexity of issues being discussed [Citation2]. As such, Design researchers from Lab4Living were invited to support Starworks activities. Lab4Living are a research cluster within Sheffield Hallam University, who bring a creative, design-led approach to research and innovation in the contexts of health and wellbeing, across the life course (see www.lab4living.org.uk).

The team planned and ran several creative, collaborative, multi-stakeholder ‘Sandpit’ events across the country, with ninety delegates representing the four key stakeholder groups. Each sandpit event followed a similar structure (identifying the problem from each stakeholder’s perspective, inspiration via exhibitions and talks, creative warm ups, ideation, prioritisation of ideas, and development of the top 4–6 ideas), with the content being adapted to the key theme for each session.

Ideas from the Sandpits focussed on a number of key issues associated with prosthetic rejection, including; socket fit and comfort; adaptability and growth; connectivity and conductivity within electronic prosthetic devices; unique movement/play patterns for children; information needs for families, and aesthetics.

By focussing on creative ways of sharing experiences we were able to elicit the priorities for child prosthetic development from each of the different stakeholder groups’ perspectives, and support collaborative activities to pull these perspectives together into actionable ‘next steps.’ For many participants, these events presented the first opportunity to speak to, learn from, and work with other stakeholder groups - with many delegates highlighting that this was the most valuable part of the sessions. The fact that many of the PoC applications included people who attended the sandpits, and addressed issues raised in these sessions, demonstrates the value of creating playful, exploratory, multi-stakeholder events such as these.

Putting work in at these early stages, creating a range of methods for multiple perspectives to contribute meaningfully, is key to fostering innovations that respond to ‘clinical pull’ rather than ‘technical push’ (i.e., exploring all available options to address an authentic unmet need, rather than searching for an ill-fitting context to apply an existing technical innovation). This is core to much of the work conducted by NIHR D4D and NIHR CypMedTech, as this can lead to more sustainable innovation that is more likely to survive implementation.

2.2. Building a sustainable network

2.2.1. Formation of the network

From the beginning, Starworks aimed to become a sustainable, ongoing network – a long-term community rather than creating a ‘team’ for a finite project. However, this can be challenging for several reasons. Research priorities and focus changes, funding can run out at a point where projects aren’t ready to apply for further grants, and project team members may move on, to name but a few challenges (see [Citation5] for further discussion of these issues). This can lead to poor implementation and uptake, as well as loss of trust and credibility for the research initiative. It is also often the case that PPI, if carried out, only occurs in the early stages, therefore patients’ views and needs may be taken into account early on but never revisited to check projects still align with them. However, Langley [Citation2] suggests that key considerations for promoting long-term, sustainable collaboration between stakeholders include:

Giving equal voice to all participants

Anticipating the potential for conflicting perspectives

Eliciting issues occurring in everyday life

Engaging in a fun and relative way

With this in mind, a network approach was taken, whereby each of the key stakeholder groups were approached and invited to join an ongoing community of interest centred around the original aim of increasing research focus in child prosthetics. Stakeholders were invited through channels most relevant to them (i.e., via charities for families) and their engagement was optional at all times – they would learn about news and opportunities to be involved in related activities or events, and could opt-in to join if they were interested.

2.2.2. Rationale for a network approach

A network approach within paediatrics has been found to be effective in a range of health technology development contexts. An example of this has been The Technology and Innovation Transforming Child Health (TITCH) network (https://cypmedtech.nihr.ac.uk/titch-network/) was established in 2014 by NIHR D4D and Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust to address the known issues within paediatric technology development. This led to over £4 million in leveraged funding to develop innovations for dedicated unmet needs in child health, and ultimately led to the creation of NIHR CYPMedTech. Within Starworks, the sustainability of the network has been enhanced by ensuring both the research focus, and the methodologies used to address these issues, remain relevant and contemporary.

In terms of the research focus, the co-design approach taken throughout Starworks created a vehicle for all stakeholder groups to have agency over shaping the ongoing direction of the project. For example, the key issues emerging from the initial unmet needs assessment were used as themes for the subsequent sandpit. As such, the community of interest gathered around these topics became more invested in seeing the projects succeed, as they were responsive to their own experiences and expertise.

In terms of the methods used to engage stakeholders, these too were responsive to the preferences of stakeholders, as well as unforeseen changes in the working landscape (such as the Covid-19 pandemic). Details on the specific methods are available in [Citation6] and [Citation7]. For the purposes of this article, the translatable findings can be summarised as the need to develop bespoke, parallel approaches to engaging children and families, and professional stakeholders, on a long-term basis. This was achieved through the three key component parts of the Starworks Network; The Starworks Core Team, The Starworks Expert Network, and the Starworks Ambassador Scheme.

2.2.3. Co-ordinating all stakeholders: the starworks core team

The Starworks core team is made up of key team members from both NIHR D4D and NIHR CYP MedTech, with experience in project management, co-design, and the translation of paediatric healthcare research into practice and technology development. There are three members in total, and they act as a bridge between the two networks, providing a trusted, opt-in way for families to choose which (if any) of the available research opportunities they wish to take part in. In addition, Starworks endeavours to keep families informed of progress made in research projects since their participation.

2.2.4. Engaging professional stakeholders: the starworks expert network

The aim of this network was to engage three of the key ‘professional’ stakeholder groups – clinicians, academics and industry experts. The Expert Network aims to connect research ‘silos’ across the UK, building more of a momentum in research in this area, enhancing its sustainability. This is important to not only facilitate mutual learning but also to support and foster collaborations, facilitate new projects and to identify and validate further unmet needs for children with limb loss. The network approach ensures we have the correct balance of expertise dedicated to supporting innovation.

2.2.5. Engaging children and families: the starworks ambassador scheme

In our work prior to, and during, the sandpit events, Starworks worked closely with charities (e.g., LimbPower), who are well placed to advise on appropriate methods of engagement, having already developed long-term, trusted relationships with the families they work with. This engagement early on was not only successful in gaining trust from children and families [Citation2] but important when focussing on building a network and finding fun, rewarding ways to encourage continued support of Starworks activities.

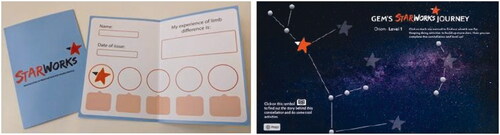

From this, we co-developed the Ambassador network, which aims to engage children and young people who use prosthetics, as well as their siblings (and, by proxy, their parents). Within this, opportunities to be involved in research & innovation are publicised to the parents of registered Starworks Ambassadors (via email and/or social media), who can opt in to taking part if they wish. Each completed activity earns the Ambassador a ‘Star’ for their passport, which, when filled, can be exchanged for a voucher and certificate ().

Figure 3. Examples of the original (paper-based) Starworks Ambassador passport (left), and a screenshot of the post-Covid-19 digital Starworks Ambassador passport (right).

This scheme helps enable children and young people to have a say in a broader range of research and innovation in this area, ensuring it is responding to the real, day to day challenges they experience. Importantly, it also rewards children and young people for sharing their unique expertise, and helps to build trust, so they know they are being listened to and that the information they are providing is vital to continued research. This ‘buy-in’ to the Starworks network is a key foundation to support its sustainability in the future.

2.2.6. Summary

This strong network approach was crucial to navigating potential barriers to innovation in the emerging area of research within child prosthetics. This also had particular importance for the Proof of Concept project teams, discussed below.

2.3. Fostering impactful innovation

Research into clinical prosthetics, particularly that undertaken by prosthetists, has been somewhat lacking when compared to other (similar) clinical fields. It was only from 1996 that prosthetists in England were graduating with academic degrees, and therefore more able to undertake academic research at master’s level or above. The development of the recent Centre of Doctoral Training in prosthetics and orthotics (involving University of Salford, Strathclyde University, University of Southampton, and Imperial College, London) is one response to the relatively small amount of research activity within the sector [Citation8]. Importantly, projects such as Starworks have enabled prosthetists to work with other academics to target specific areas of practice that require improvement. It is this focus on collaborative research, where the skills set of prosthetists, therapists, engineers, and others can be combined within working groups, which is key to forming successful outcomes for prosthesis users.

Similar to the above sections, both the focus of the research supported by Starworks, and the way in which it was supported, were key (but distinct) facets to fostering impactful innovation.

2.3.1. Identifying impactful areas of research

So far this article has discussed how a creative and collaborative approach with all stakeholders has ensured that research in this area is supporting appropriate unmet needs. Indeed, the ten successful PoC projects aimed to address a number of the themes and unmet needs established in the sandpit events, distributed approximately evenly between focussing on upper- and lower-limb prosthetics. The projects also draw on a range of emergent technologies and are exploring their novel applications within this field, including sensor technology, 3 D printing, gamification, and material sciences.

2.3.2. Fostering collaboration

Within Starworks, it was important to recognise that conducting research in a relatively new area (such as child prosthetics) may encounter unforeseen challenges. Additionally, by promoting a multi-stakeholder project team within the PoC projects, the core Starworks team also held some responsibility in supporting stakeholders with less experience/familiarity with research processes (such as some clinicians or prosthetists) to be involved meaningfully.

As such, the PoC projects had the support of the Starworks team throughout to facilitate this process. At the start of the project, the team ensured all four of the key stakeholders groups were involved, and helped to remove any barriers that would have previously prevented them being involved in research (such as helping to set up collaboration agreements, or in writing applications to ethics review boards). During the projects, the Starworks team continued their support, offering regulatory advice, guidance on how to involve children and families, and signposting to relevant resources on a case-by-case basis. Most importantly, a number of group meetings were arranged for each of the PoC teams to network, to showcase their progress, to discuss any challenges they were faced with, and to collaboratively problem-solve (rather than working in isolation). Applying this network approach between the projects helped to avoid silo-working, reduced the burden of addressing challenges that were common to several projects (such as access to families) and also helped to build relationships across the teams themselves.

Being able to capitalise on the range of expertise and experience across the projects, and indeed across the wider Starworks networks, is particularly important in research fields with smaller patient numbers (such as child prosthetics), in order to operate efficiently and sustainably. Indeed, the connections developed between PoC projects also led to several teams joining together in shared applications for (successful) further funding, further enhancing the sustainability of the network.

3. Discussion

3.2. Addressing the ‘market failure’ in child prosthetics

Each of the key learnings above are suggested as potential routes to (at least partially) addressing the ‘market failure’ situation discussed in section 1, which is common across much paediatric health research and innovation.

‘Addressing child-specific issues’ has been noted to present challenges in the short-term, particularly in financial terms due to the (relatively) small patient population (compared with adult markets) [Citation9]. However, if a long-term view is taken, and the challenge is reframed to ask the question, ‘What are the costs of not innovating for CYP patients (as discussed further in a companion paper in this special edition [Citation5]),’ then the economic arguments could be reversed. Within Starworks, it has become clear that failing to take into account things such as different movement patterns (running, playing, jumping, climbing trees or sitting cross-legged at school), contexts of use (water, mud, sand) and priorities (socialising, play, spontaneity) results in prosthetics that do not respond to the unique, emotional, social, physiological and developmental needs of children. If a child is limited in any of these areas during their formative years, the long-term health economic impacts may present a greater cost to them, and health services, in the future [Citation9].

‘Building a sustainable network’ may help to address the ‘market failure’ challenge by facilitating the sharing of knowledge, expertise, experience and resources. Taking a network approach may help to address the unmet needs in an underserved, small patient population more efficiently and cheaply, ensure key challenges only need to be addressed once (avoiding silo working and duplication of effort), and identify other, related contexts where innovations may be relevant (potentially increasing the ‘market’ and enhancing commercial viability of the solution).

‘Fostering impactful innovation’ links closely with the network approach described above, but may also address the ‘market failure’ with its emphasis on ‘impact.’ Within Starworks, discussions between stakeholder groups has highlighted a need for novel, meaningful outcome measures within child prosthetics [Citation10,Citation11]. Whilst healthcare research practice has traditionally been concerned with predominantly quantitative, generalisable measures, both families and healthcare professionals have discussed the myriad of ways a ‘good’ prosthetic can impact on a child’s life, including social engagement, confidence, academic attainment and mental health. Without recognised or ‘validated’ measures to capture these more individual, qualitative (but still very important) impacts, innovations that address these areas may not have a ‘route through’ to market. For example, an innovation that facilitates customisation and personalisation of the way a prosthetic looks may not impact on current measures of ‘success’ (i.e., walking distance), but may improve the child’s relationship with their prosthetic, their confidence, their desire to participate in social activities, and (in turn) the development of social skills that will affect the rest of their lives. Reframing and considering the potential range of impacts of child health technology innovations may help to generate the evidence base needed for funders and healthcare service providers.

As such, the authors suggest that these approaches, and a paradigm shift from quantifiable to more qualitative ways of assessing ‘impact,’ may provide useful considerations when planning and conducting research and innovation for paediatric medtech across a range of contexts. The authors also encourage others to apply and adapt them further.

3.3. Limitations

Lack of targeted funding in this area remains a major challenge. However, through the work of NIHR D4D and NIHR CypMedTech the number of paediatric technology-focussed funding calls has started to increase in recent years with opportunities announced by funding bodies such as Innovate UK, NIHR i4i (Invention for Innovation), NHS England Small Business Research Initiative (SBRI), Healthcare and the Medical Research Council (MRC). The work carried out to date by the Starworks network demonstrates that even a relatively modest amount of funding can go a long way to stimulate and develop innovation development within a diverse and challenging field.

4. Conclusion

The field of child prosthetics, like many areas of paediatric health technologies, faces distinct challenges when conducting research and innovation, including a (relatively) small patient population, the need for tailored co-design approaches, and more. The Starworks child prosthetics research network has explored and addressed some of these challenges between 2016 and 2022 (with plans to continue beyond the date of publication). Through this work, the authors suggest that the methods used in Starworks to achieve the key aims of 1) addressing child-specific issues, 2) building a sustainable network, and 3) fostering impactful innovation, may be translatable across a variety of paediatric medtech contexts. It is hoped that the examples above will encourage further funding and research in paediatric health in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank LimbPower, Steps, Reach charities for their support of Starworks activities, as well as the Starworks Expert Network and our Starworks Proof of Concept projects for their enthusiasm and commitment to this important area of research. In particular, the authors wish to thank the Starworks Ambassadors and all of the children, young people and families who have helped to make the Starworks network a reality.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Edwards P. Hundreds Of Children To Get ‘Activity’ Prosthetics In New Government Funding. Sky News [INTERNET] 2018. Apr 18 [cited 2021 Oct 21]; Research. Available from: http://news.sky.com/story/hundreds-of-children-to-get-activity-prosthetics-in-new-govt-funding-11325711.

- Langley J, Wheeler G, Mills N, et al. Starworks: Politics, power and expertise in co-producing a research, patient, practice and industry partnership for child prosthetics. In Christer, K., Craig, C., & Chamberlain, P. (Eds.) Design 4 health. 2020. pp. 314–322. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Design 4 Health, Sheffield Hallam University: https://research.shu.ac.uk/design4health/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/D4H-Proceedings-2020-Vol-2-Final.pdf

- McCarthy AD, Sproson L, Wells O, et al. Unmet needs: relevance to medical technology innovation?. J Med Eng Technol. 2014;39(7):382–387.

- Wheeler G, Mills N, Langley J. The starworks project: Annual report to national institute for health research 2017–2018. Project Report. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Sheffield Hallam University. 2020. [Monograph]

- Mills, et al. Overcoming Challenges to Develop Technology for Child Health. 2022. [submitted]

- Mills N, Langley J, Bauert C, et al. Co-production in Action: The Starworks Project. Invited webinar and guidance document as part of INVOLVE and Cochrane Training ‘Co-production in Action’ series, 22nd November 2019. Available at: https://training.cochrane.org/resource/co-production-action.

- Wheeler G, Needham A, Mills NThe Starworks Child Prosthetics Research Network: Progress and Next Steps Proceedings of BAPO, et al. 2021b. October 8–9;online. https://www.bapo.com/events/conference-2021/.

- https://www.salford.ac.uk/centre-doctoral-training-prosthetics-and-orthotics#:∼:text=UK%2C%202014).-,The%20EPSRC%20Centre%20for%20Doctoral%20Training%20in%20Prosthetics%20and%20Orthotics,i.ndustry%20and%20third%20sector%20agencies.

- Dimitri P. Child health technology: shaping the future of paediatrics and child health and improving NHS productivity. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(2):184–188.

- Wheeler G, Langley J, Mills N. Risk & reward. Exploring design’s role in measuring outcomes in health. Des J. 2019;22(sup1):2231–2234.

- Wheeler G, Ankeny U, Langley J, et al. Exploring the role and potential impact of novel, meaningful outcome measures for children with limb difference in the starworks project. Poster presented at 5th National PROMS Annual UK Research Conference. 2021a. June 16-17; Online https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/proms-2021.

- Fischer G, Wells S, Rebuffoni J, et al. A model for overcoming challenges in academic pediatric medical device innovation. J Clin Trans Sci. 2019;3(1):5–11.

- Hall M, Wustrack R, Cummings D, et al. Innovations in pediatric prosthetics. JPOSNA. 2021;3(1):1–9.