ABSTRACT

Although photography has long been acknowledged as an important research method and didactical tool in human geography, we feel the need to redraw attention to this particular form of doing explorative research. Today’s society becomes increasingly “ocularcentral”, yet this trend seems unparalleled with a rise of photography in academic work. Based on 10-year experience of using photographic essays in our graduate course on Urban and Cultural Geography, we show how taking pictures can enhance active and engaged learning, spark feelings of enchantment, and stimulate critical, reflexive and non-discursive thinking by asking students to translate theory to practice and vice versa. Our students have “looked with intention” how certain geographical theories are “congealed” in Berlin’s urban landscape, specifically linking theory to empirical practice and vice versa. Despite the act of photography being inevitably partial, personal, biased, voyeuristic, colonial and possibly unethical, we believe that the enthusiasm and geographical gaze it brings into the classroom outweigh these limitations. The paper illustrates with multiple examples how the embodied practice of photography results in students carefully reflecting on the physical and social world around them and acknowledging the multimodality of the city, not just as built environment but also as a social sphere and lived place.

Introduction

Photography has long been acknowledged in this journal as an important – albeit often underutilized – research method in human geography (e.g. Davies, Lorne, & Sealey-Huggins, Citation2019; Hall, Citation2009, Citation2015; Lemmons, Brannstrom, & Hurd, Citation2014; Rose, Citation2008; Sanders, Citation2007). Meanwhile, however, our world is becoming increasingly visually orientated, as illustrated by the rise of social media such as SnapChat and InstagramFootnote1 and the popularity of vlogs. Technological advancements create the potential for everyone to be a photographer, as mobile phones and accompanying apps allow making good-quality pictures (Welsh, France, Whalley, & Park, Citation2012).Footnote2 Consequently, photography and film have become more and more available to both ordinary consumers and researchers. Hence, “ocularcentrism” – a term coined by Jay (in: Rose, Citation2001, p. 7) to define the centrality of the visual in contemporary Western life – is much more omnipresent now than when it was first introduced in 1993. The centrality of the visual is of course much older; inspired by the thinking of Plato, Descartes and the philosophers of the Enlightenment in the late eighteenth century (see also Jonas, Citation1966; Levin, Citation1993), it is often seen as the source of any kind of observation and conceptualization, even far before the dominance of the written and spoken language (Carusi, Citation2012; Evagorou, Erduran, & Mäntylä, Citation2015). The way we use the term is not so much metaphoric but rather directly related to the eye as one of our main bodily senses, our source of knowledge and window to the world. Although one might expect some scepticism in modern science about what the eye actually sees following Descartes’ ideas about the disembodied rational eye, we can nevertheless observe that visualizations of our rational ideas and measurements, under the influence of new visualization techniques, are gaining influence as a medium for our imagination and thinking.

In contrast, however, visual methodologies do not seem to have gained much popularity in the work of both academic staff and students in the field of the social sciences including geographyFootnote3, even though Hall (Citation2009, p. 453) stated: “studying human geography at university without photographic images would be unthinkable.” While maps and landscape drawings have played a fundamental role in the development of geography as a discipline (Sidaway, Citation2002), there is a tendency among geographers to reduce their use of maps (Boria, Citation2013). A quick-scan of recently written Bachelor and Master theses at our geography and planning department indeed shows that many of them lack any map or other illustrations. Moreover, while most of these theses are based on qualitative or mixed methods rather than quantitative research, hardly any of them use visual data as a research method. This contributes to Sanders (Citation2007) findings that the methodological and pedagogical contributions of photographs have been overlooked in geography, mainly limited to field courses (Davies et al., Citation2019). Phillips (Citation2015, p. 621) argued that geography students are “methodologically conservative”, often opting for interviews. It is therefore questionable to what extent photography is indeed becoming less peripheral in human geography’s research practices and curricula, as Hall (Citation2015) claimed.

Consequently, we feel the need to reinvigorate the debate about the importance of using photography as a research method and didactical tool in the geography classroom. As outlined before, taking pictures can enhance active and engaged learning (Davies et al., Citation2019; Hall, Citation2009; Rose, Citation2008; Sanders, Citation2007), feelings of enchantment (Pyyry, Citation2016, Citation2018), and critical, reflexive and non-discursive thinking (Alerby & Bergmark, Citation2012; Latham & McCormack, Citation2009; Sidaway, Citation2002). Of course, also other visual methods like field sketching might be used for similar reasons, and are also used in related research (Bernardt, Huigen, & Van Hoven, Citationforthcoming) but are much less practical to use, and can often not cope with the dynamics of the urban scenery. We would like to enhance the body of literature in two ways. First, we want to emphasize that photographic essays are not merely stimulating motivation and engagement, but also require students to actively think about translating theory to practice and vice versa. We thus want to conceptualize the embodied practice of looking through a lens, while at the same time reflectively involving with the physical and social world around us, creating a lived experience and knowledge. As such our motivation to use photographic essays aligns with Sanders, who talks about the process of “looking with intention” to understand “how ‘ideas’ ground themselves in the landscape” (Sanders, Citation2007, p. 183–4).

Second, there are many good fieldwork ideas in circulation, but limited evidence of what students really get out of them (Phillips, Citation2015). Moreover, “discussions of photographic research methods in the Human Geography curriculum (…) tend to lack long-term perspectives and are often based on a relatively limited amount, or limited range, of data” (Hall, Citation2015, p. 330). In this paper, we would like to share 10 years of experience using photographic essays in our graduate course Urban and Cultural Geography. By providing concrete examples and photographs, we will illustrate both geographical and didactical learning outcomes. Moreover, we also show how photographs were taken in one course can serve as input for analysis or “key teaching resource” (Hall, Citation2015, p. 340) in another course, thus serving multiple purposes in our geography curriculum.

Below, we will first introduce the course and its assignments more elaborately, including our motivations to choose for these particular forms of assessment. In the following sections, we discuss the students’ observations through their cameras’ lenses. We conclude with formulating a number of learning outcomes regarding the photographic essay as a didactical tool.

Urban and cultural geography

We have been teaching the course Urban and Cultural Geography to our Master students for more than 10 years. For the purpose of analysis, we will focus on the last 5 years in this paper (). Each year, about 20 to 35 students participate in the course, which is the first one they take when enrolling in the Master track in Urban and Cultural Geography. The course aims to familiarize students with different theoretical concepts, approaches, and methods regarding contemporary cities, urbanization and urban policies. This includes both classic and contemporary texts on the city and urban life, with a special focus on the cultural aspects of urban life and urban development. Through engagement with works of, among others, Simmel, Wirth, Sennett, Benjamin, and Latour, we explore the variety of ways in which different theorists have attempted to interpret the nature of the contemporary city. However, we explicitly want our students to connect these different theoretical approaches to real-life cases and their own empirical work, as they will also be doing in their own Master thesis research. The didactical means used in this course are hence all geared towards engaging with (often abstract) theoretical perspectives but also with the empirical realities of urban processes in the Netherlands and abroad.

Table 1. Overview of urban & cultural geography master course.

The course consists of a mix of student-led seminars, (guest) lectures and a 4-day field trip to Berlin. The seminars encourage students to engage actively with the literature, while the lecturers illustrate how they apply certain theoretical notions in their own empirical research. Phil Hubbard’s textbook “City” serves as main backbone of the course, which “despite its title, this is not a book about cities. Rather, it is a book about urban theory” (Hubbard, Citation2006/2018, p. 1). Similarly, our course is not a course on cities, but on urban and cultural theories “exploring the way that sociologists, planners, architects, economists, urbanists (and particularly) geographers have sought to make sense of the urban condition” (Hubbard, Citation2006/2018, p. 1). In his first edition of the book, Hubbard categorized these different theories in five chapters: the represented city, the everyday city, the hybrid city, the intransitive city, and the creative city.Footnote4 Each of these “cities” is used as dominant perspective in one of the seminars and lectures. Consequently, students become familiar with different lenses to research the city.

The Berlin fieldtrip takes place at the end of the course and entails a combination of student-led walking tours in which one of Hubbard’s themes is applied to a Berlin neighbourhood, and time to work on the photographic essay. Although we fully support the importance of doing (international) fieldwork (See, e.g., Hope, Citation2009; Phillips, Citation2015), including activating assignments such as student-led tours (Coe & Smyth, Citation2010) or field diary writing (Dummer, Cook, Parker, Barrett, & Hull, Citation2008; Glass, Citation2014), we would like to focus on the use and value of the photographic essay in this paper.

Photographic essays

Students are required to produce individually a photographic essay of 1500–3000 words and 1–15 pictures documenting the results of their observations in Berlin. There is no parity weighting; less pictures do not allow for more words or vice versa. Students have to make their own pictures to train their observational skills, but they are allowed to use maximum two pictures made by other photographers, for example, if they would like to do “repeat photography” (Davies et al., Citation2019; Lemmons et al., Citation2014) and illustrate how the urban landscape looked like in the past. As the joint composition of image and text, the essay should answer the following question posed to the students, pushing them to go beyond superficial observations: How does Berlin challenge, affirm, or force you to abandon ideas you have acquired about cities and city cultures or “the urban” in the course? Hence, the photo-essay must demonstrate in an explicit way how the students are linking their own thoughts to those discussed in class and in the weekly readings as well as to their observations and experiences in Berlin. They prepare beforehand by reading (additional) literature about their selected topic of observation (e.g. everyday life in the city, embodiment, gender representation, city hybridities, urban cultures, social exclusion). Moreover, one lecture prepares the students for doing fieldwork and using photography as a research method, discussing amongst others the framing of images (focus, selection, perspective, composition, etc.) and the ethics of doing photography, including consent and anonymity (Rose, Citation2008).

We do not provide any technological support (e.g. on camera’s functionalities), as using digital cameras is hardly a novelty anymore (different from Latham and McCormack’s time of writing in 2007). Hence, we concur with Watt and Wakefield (Citation2017, in Davies et al., Citation2019, p. 4) that “our students are socially competent photographers, and the practice of taking and sharing photographs is an everyday norm.” Moreover, following Hall (Citation2015), we try to disregard the technical or aesthetical quality of the photographs and instead regard them as pieces of social science data. We also do not offer any institution-owned technological devices, relying solely on student-owned mobile devices (first mainly cameras, currently mostly mobile phones), what Davies and colleagues (Citation2019, p. 4) call “bring your own device” (BYOD). As Welsh et al. (Citation2012) indicated, this is potentially cost-effective for departments but might also have its drawbacks, such as students unwilling to use their private devices for academic purpose or not being able to afford them. However, over the years, we never had a single student approaching us, because he or she was unable or unwilling to use a photographic device, and anyhow, given the ubiquitous availability of smartphone cameras, and almost nonexistent restraints in using them, this nowadays seems to be a rearguard debate. Of course, this does not automatically imply that students will never have a problem. However, as long as relatively cheap disposable cameras are still available as a contingency plan, there is no immediate reason for providing institution-owned devices.

Upon return from Berlin, the students have 3 weeks to finish their essay. The essays are assessed on the basis of a number of equally important requirements, including a clear story line, adequate use of course materials, the selection and framing of the pictures, and general academic conventions such as a good structure and writing style (). Below, we first discuss the advantages of using photographic essays and then outline their limitations.

Table 2. Evaluation form used to assess photographic essays.

Advantages and disadvantages of photographic essays

We selected the photographic essay as a form of assessment for a number of reasons (cf. Hall, Citation2015, p. 329–30). As indicated above, our postmodern world is increasingly visually oriented or “ocularcentral”, amongst others due to technological advancements. Consequently, this assignment is in line with general societal trends as well as our students’ interests and lifeworlds. Many students already employ visual practices in their everyday life through apps such as Instagram, and can hence be regarded as “visually literate digital natives” (Davies et al., Citation2019, p. 3). However, the didactical objectives were more decisive. We strongly agree with Pyyry (Citation2016, p. 103), who stated that the act of taking photographs is an appropriate way to knowledge, since “knowing is inseparable from doing, it happens in encounters within the world.” She asked her students to make pictures of very familiar locations where they regularly hung out. By looking “at the world anew” (Pyyry, Citation2016, p. 102) through the lens of the camera, the students did not take these places for granted anymore, but became aware of local relations and processes. As such, they became “enchanted” and appreciated the special even in mundane, local relations, objects or practices (Pyyry, Citation2018). In other words: photography was used as a method to “make the familiar unfamiliar” (Taylor et al. Citation2013, in Pyyry, Citation2016, p. 102) and question the “taken-for-granted”.

In line with Phillips (Citation2015), we argue that the opposite also occurs. Most of our students visited Berlin before, but none – except for the occasional German student – is very familiar to the city. Yet, by spending time in space, looking around, observing what is happening and basically “reading the landscape” (Lewis, Citation1979), unfamiliar Berlin becomes somewhat familiar to them. Phillips (Citation2015, p. 619) claimed that it is even easier to look with fresh eyes (or using other senses) when one is far from home: “the intense experience of non-local fieldwork, where sensory stimulation prompts enquiry, can be helpful in developing skills that can ultimately be applied nearer to home, to familiar settings that can be more challenging to see with fresh eyes.” This was also explicitly confirmed by students who visited Berlin before, but, when asked, unanimously stated, that from now on they learned to see Berlin with different eyes. It was the camera which made them attentive to more details and to the concerted whole of the details in urban situations. In taking pictures they also had to think a lot about their own composition of the picture (Acton, Citation1997).

Regardless of the level of familiarity, “photography situates the student’s own observation at the heart of the research process, promoting an active engagement with the subject studied” (Hall, Citation2009, p. 455). Not just the mere act of taking pictures is activating, but also the selection, framing and analysis of the pictures: “Photography demands that students register complexity, sort information, look for – and find – pattern and make meaning” (Sanders, Citation2007, p. 185).

In addition to active and engaged learning (Hall, Citation2009; Rose, Citation2008), we opted for photographic essays to encourage students to not just look, but also think about urban landscapes. “For most Americans, cultural landscape just is”, Lewis (Citation1979, p. 11, original emphasis) concluded. For them, the landscape is “something to be looked at, but seldom thought about.” We wanted the students to think how certain theoretical notions were grounded in the landscape (Sanders, Citation2007), requiring them to translate abstract theories in concrete items, persons or urban landscapes. Moreover, doing photography cultivates the students’ sensory receptivity and sense of place (Phillips, Citation2015; Pyyry, Citation2016), which fits within everyday, non-representational ways to research the city (Dowling, Lloyd, & Suchet-Pearson, Citation2018; Latham & McCormack, Citation2009) that have become increasingly popular in academia, including this journal, in recent years (Glass, Citation2014; Simm & Marvell, Citation2015) and that were also discussed in the course textbook (Hubbard, Citation2006/2018, p. 120).

Since our students were challenged to look at Berlin with a specific theoretical perspective in mind, they needed to translate theoretical concepts into observable phenomena in Berlin, or the other way around, interpret these phenomena as representations of the theoretical concepts. However, because taking pictures of these phenomena does not allow the students to focus on these phenomena and interpretations or representations in isolation, it also required them to engage actively with the context, framing and relations, affects and other non-discursive or non-representational elements. So the change of mode and medium of observing brings in the unexpected and unfamiliar, and activates students to think. In addition, since the photographic essay is not just a record of their observations, but should also express their own view and take on the theoretical perspective and the empirical data, another translation of the students’ observations was demanded. They needed to find the best way to use their pictures to tell their own story both verbally as well as through their selection of pictures. This again involves not only discursive expressions, but also non-discursive, or non-representational elements (Latham & McCormack, Citation2009). The results are therefore not so much final truths or “data-as-evidence” (Pyyry, Citation2018) about Berlin or certain theoretical perspectives, but much more exemplify students’ thinking about and dwelling with the city or the urban. As such, it resembles Pyyry’s (Citation2018) statement that the focus of a photowalk is not on the end-product (i.e. making pictures for the essay), but what emerges during the walk itself in terms of knowledge, experience, etc.

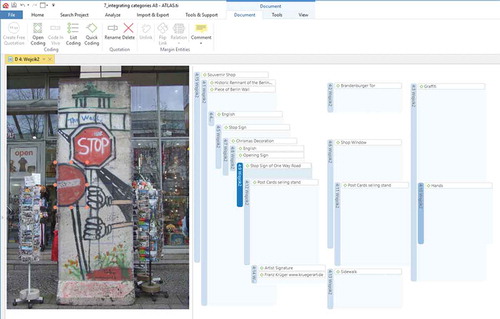

Lastly, we not only value the photographic essay as didactical tool bringing focus, enthusiasm, and enchantment in our Master course, but also because it has allowed us to build up a rich archive of visual data on Berlin over the past decade. With permission from the Master students, we use their pictures in an undergraduate course on qualitative methods, as a dataset to practice content analysis on visual data (see for an example of a coded photograph). As such, student work can become a key teaching resource (cf. Hall, Citation2015, p. 340); the photographic essay thus serving didactical purposes at multiple phases of our geography curriculum. This latter use of the photographic material also adds another aspect to the learning experience. While the Master students are stimulated to translate theory to photographs, the Bachelor students – in reverse – interpret these photographs to reconstruct the stories (including theories) told by the Master students. As such, the undergraduates not only train their analytical skills, but also prepare themselves for their own future photographic assignment in Berlin.

Obviously, photographic essays have their limitations. Photographs are inevitably partial (Sidaway, Citation2002), personal and biased (Hall, Citation2009), voyeuristic and colonial (Sanders, Citation2007) and might say more about (the knowledge or cultural lens of) the photographer than the studied theme (Lemmons et al., Citation2014): “showing not what was, but how things were seen” (Rose, Citation2008, p. 152). As social constructs or representations (Latham & McCormack, Citation2009), photographs do not show “the truth”, but reflections or even reinforcements of misconceptions students have (Nairn,Citation2005, in: Hope, Citation2009). To overcome these limitations, Lemmons et al. (Citation2014) advocate for repeat photography, in which students need to compare “then and now” pictures and see them as (re)creations of culture instead of as objective representations.

Some argue that pictures can never show the “actual” or “present” situation, but are “souvenirs” or “moments of death” (Latour & Hermant, Citation1998; Shields, Citation1996). Consequently, Shields (Citation1996, p. 230) concluded that “photographic ‘shooting’ kills not the body but the life of things, leaving only representational carcasses.” In turn, Latour and Hermant (Citation1998) showed that a full picture can never capture all of Paris; all representations are limited depictions whether it is a ceramic panorama, computer game or satellite picture. Hence, Paris is “invisible” (cf. the title of their photographic essay), or alternatively: there is not one, but “multiple Parises in Paris” (Latour and Hermant, Citation1998,p. 4). Moreover, the subjects of photographic essays are rarely allowed to directly “speak” to the readers; they “represent people, by other people, for yet other people” (Klingensmith, Citation2016, p. 4).

In addition to these more fundamental ontological and epistemological questions what images actually “are” and what they “can do” (Latham & McCormack, Citation2009), there are also some practical and ethical challenges, especially when it comes to photographing local people (Scarles, Citation2013). Our students might not have permission to picture certain persons or places (for example, privately owned shopping centres). In search of the perfect picture illustrating their selected theoretical notions, they might lose sight of what is appropriate, acceptable or responsible, as Scarles (Citation2013) also observed when researching tourist photographic practices. Rose (Citation2001, p. 336) stated that: “the very act of taking photographs creates an opportunity for negotiation about consent.” However, it hard to check whether all imaged persons portrayed in the photographic essays are in fact asked for permission. Lastly, our students were free to focus on a particular topic discussed in class; consequently and in comparison to the classical written exam, we cannot fully assess whether they actually master all course material.

However, many of these limitations can be bypassed by requiring students to reflect upon the use of pictures in their essay, as Hall (Citation2009, p. 460) also advised: “Think about what photographic research methods reveal about the subject you are studying but also think about what they reveal about the process of research, its limitations and possibilities, opportunities and problems and your own part in it.” This not only applies to using photographs when doing fieldwork (e.g. Hall, Citation2009; Pyyry, Citation2018; Rose, Citation2008; Sanders, Citation2007), but also to other innovative methods like reflective fieldwork diaries (Dummer et al., Citation2008) and more experimental, playful and multi-sensory methods like touching or listening (Phillips, Citation2015). Hence, we require our students to reflect on the use of photos as research material, as part of the essay’s assessment criteria ().

Student evaluations

For most of our students, writing a photographic essay on their Berlin fieldwork was a first time experience with using visual data as a research method, confirming Sanders (Citation2007) observation that the pedagogical contributions of photography are still overlooked in geography. The assignment made our students enthusiastic, but also slightly uncomfortable at first. Being often summoned to only functionally include pictures in their writing throughout their student careers, using multiple photographs in their essay felt like spicing-up their work rather than doing serious research with visual data. Alerby and Bergmark (Citation2012, p. 101) found similar scepticism and argued that an important future challenge is “to make this kind of research rigorous and trustworthy as well as accepted by other researchers.” However, after finishing their essays, all doubts had disappeared and students generally enjoyed the assignment not just as “nice”, “alternative” or “creative” (cf. Sidaway, Citation2002), but also because it challenged them (). For example, as one student (class of 2014) remarked:

“It was a really interesting course, which challenged me to look differently to what a city actually is and consists of.”

When asked specifically about the use of photographic essays, the students generally appreciated it as another mode of representing ideas, which forced them to think differently about Berlin (score of 4,3 on scale 1–5), and encouraged them to discover aspects that could not easily be put in words (4,4) and to present their results in a more convincing way (4,3; see ). One student (class of 2018) formulated its benefits as follows:

“The photographic essay was a good way to understand more about the course, not only in words but also in visual image.”

Time constraints and lack of clarity on how to write a photographic essay were the only negative remarks mentioned in student evaluations:

“In Berlin, there was not enough time to prepare a good walking tour and a good essay.” (student from class of 2016)

“The photographic essay was a bit vague, make that more clear.” (student from class of 2016)

In response to these negative remarks in the student evaluations of 2016, we have tried to communicate our expectations more elaborately by adding an evaluation rubric to the course manual (), as well as providing two “best-case” essays from previous years. This might explain the increased appreciation of criteria’s clearness from 3.8 in 2014 to 4.2 in 2018 ().

Materiality of the city

A certain theory or concept was leading when deciding which places to explore; as a result, many students did not visit typical tourist sites such the Brandenburger Tor, Unter den Linden and the East Side Gallery at all – or if they did, they looked at them differently, beyond the typical “tourist gaze” (Davies et al., Citation2019; Urry, Citation1990). Raoul, for example, investigated Ostalgie – a sense of nostalgia for the former East. He was surprised to find how some remnants of the Berlin Wall, are highly commercialized, staged and “touristified” (for example, at Checkpoint Charlie), while others are abandoned or integrated in the everyday life of the Berliners. Hence, his photographic essay made him wander around both familiar and unfamiliar locations in the city, similar to Benjamin’s (Citation1999) flâneur, Burckhardt’s (Citation1998) strollology or the Situationist’s dérive (Pyyry, Citation2018). As such, Raoul choose an approach similar one of Phillips’ (Citation2015) students, who did the “opposite of what a traveller would do” in portraying the small and everyday of New York City rather than the big and spectacular.

Dagmar investigated the accessibility and mobility of Berlin to disabled people, and found out, quoting Sawchuk (Citation2014, p. 417), that impairment is indeed “neither simply subjective, nor medical nor a part of the built environment. It is a state of perpetual being that is relational, contingent, material and temporal.” She first photographed obvious objects that facilitate disabled people, such as wheelchair ramps and Braille signs, but later also became aware of the effects of unpredictable and temporary obstacles in the urban environment, such as out-of-order escalators () or people with strollers, wheelchairs and bicycles all competing for the limited available places on the subway during rush hours. The assignment made her more reflexive regarding how accessible cities really are and how they are often designed for the abled body or “average human being”, something she did not contemplate on before.

Figure 2. Out-of-order escalator turning subway stairs into an obstacle for two elderly ladies (Dagmar van de Schraaf. Oct. 2017).

We advised our students to prepare well before the start of the fieldtrip, so they knew what to look for; yet, at the same time we advocated for flexibility and the possibility of enchantment or “time and space for surprises and changes of direction: time to wander and wonder” (Pyyry, Citation2016, p. 103). Daan was already familiar with the dominance of graffiti in Berlin, but during the fieldtrip he became suddenly fascinated by smaller signs of street art and advertisements that he not considered earlier. Everywhere he looked, he saw lampposts filled with stickers and posters as a way to communicate certain messages, ranging from advertisements and political standpoints to lost-and-found messages and art. Some of the lampposts even doubled in size as a result (). He subsequently tried to research the geography behind the posters: where did which posters emerge and why?

Figure 3. Poster advertisements for parties, doubling in size lampposts in Kreuzberg (Daan Middelkamp. Nov. 2015).

The focus on wheelchair ramps, lampposts and other materialities in the city was present in nearly every photographic essay. Instead, very few people appeared in the pictures (cf. Rose, Citation2008), even though human geography is essentially about the relation between man and the environment. This might have been the result of our repeated warnings concerning ethical considerations such as getting consent and respecting anonymity, although we did not explicitly instructed our students to exclude people or events from their photographs, like Sanders (Citation2007, p. 190). To stimulate our students to focus not only on the built environment, we temporarily added a requirement of conducting at least two short street interviews. However, time to do these interviews proved to be limited in Berlin, next to preparing and conducting walking tours and taking photographs. We hence turned the requirement into a recommendation in the following years, illustrating our continuous efforts to fine-tune the assignment in response to student evaluations.

Nonetheless, the emphasis on materialities was very fitting for those students interested in applying Actor–Network Theory, in which non-human actants are regarded as important as humans in making things happen. Over the years, multiple students focused on natural phenomena such as falling leaves, wind, rain and animals to reflect on the culture–nature dichotomy (Hubbard, Citation2006/2018) and to argue that nature is not excluded or eliminated, but an essential part and “co-constructor” of the city, whether carefully manicured or uncontrollably creeping back onto buildings and pavements. Other students focused on non-human actants such as surveillance cameras, traffic lights, and glass as a construction material. For example, Lisa focused on balconies as non-human actants serving multiple purposes in the city. She argued they are not just part of a building’s facade, but also facilitate individual expression as a way to stand out from the urban, anonymous crowd, provide social surveillance opportunities through “eyes on the street”, and offer opportunities for a greener city. Overall, these students did not take non-humans for granted, but acknowledged that they too have agency in the city.

Picturing the invisible and the non-discursive

In contrast, some students did not try to photograph visible materialities, but instead to “see the invisible” (Phillips, Citation2015). Giovana used a multisensory approach (cf. Dowling et al., Citation2018; Pyyry, Citation2016, Citation2018), by looking for sounds. Similar to Phillips (Citation2015) student Ben, who focused on the sound of the subway, she took photographs of fire trucks, street musicians, pedestrians’ feet and other actors/actants producing soundscapes. It made her very aware of how sounds affect people’s experience of and behaviour in the city, for example, when an ambulance or fire truck approaches (). Yet, next to these intentional sounds, there is a myriad of other unintentional “urban music” like the sound of people walking on the stairs, which often goes unnoticed until something extraordinary happens (e.g. the sound of a running person).

Figure 4. Sirens of the fire brigade create a sense of emergency and urgency (Giovana Militao Medeiros. Oct. 2016).

Bryan tried to capture what was below the surface, arguing that cities are usually conceptualized through their physical appearances above ground (buildings, street, monuments, parks), which ignores the importance of underground infrastructures such as water storages and subway systems. Although this urban underworld might seem invisible at first, it surfaces and interconnects to the world above, for example, through tree root-caused cracks in the pavement, U-Bahn signs, transformer boxes, and information plates locating networks of water pipes, electricity or gas conduits ().

Figure 5. Signs indicating underground water pipes at Nollendorfplatz (Bryan van Alebeek. Oct. 2017).

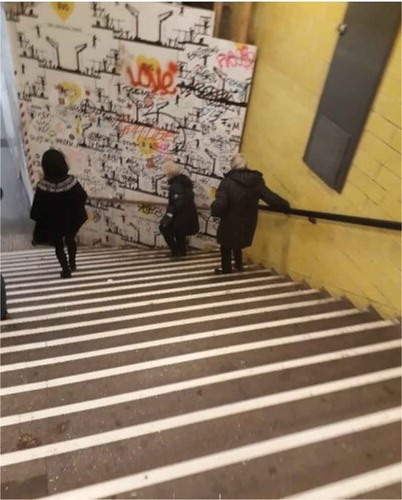

Nils did not focus on invisible materialities, but seemingly invisible people: homeless Berliners. He argued that homeless people are often ignored or avoided in the city, while it serves as their home which they use in ways often very different than intended by city officials or dominant “representations of space” (Lefebvre, Citation1991). Consequently, ventilation grids turn into sleeping places and small springs in the park become washing stations. Nils intended to hand over disposable cameras to the homeless, to illustrate how they understand, use and experience places in Berlin. This form of auto-photography (derived from autobiography) or informant-produced research is particularly helpful when investigating marginalized groups, since it offers researchers a way to let participants speak for themselves (Noland, Citation2006). Unfortunately, however, Nils wrote in his essay that he was “keen to explore the possibilities [of auto-photography] but too naive and inexperienced to expect the failure that my endeavour would eventually become. As one could have expected, finding participants was a rather difficult task (…), the three cameras I gave too willing participants were not delivered back and my time in Berlin was too short to trace the participants through the city.” Instead, he worked in a homeless shelter and spent a day and night on the street with a homeless man. Although this limited his ability to take meaningful pictures for the essay (for privacy and security reasons he could not bring his camera and mobile phone into the shelter), Nils gained unique insights in the lives of homeless people in Berlin. Nils was one of the only students who experimented with more “bodily interventions” in conversation with the photographed subject (cf. Hall, Citation2015; Latham & McCormack, Citation2007), the majority of the essays were based on more disengaged observational processes.

Although the urban landscape described in the student essays might give some clues about what is happening, it remains hard to identify real causes and effects. For example, many students took pictures of redeveloped buildings or construction sites as signs of gentrification, yet other processes could be at play. Moreover, it proved to be difficult to go beyond easy-to-observe discursive signs, like anti-gentrification graffiti and slogans (“yuppies raus”, “Fuck Google”) and to look for non-discursive evidence. Sera, however, did manage to convincingly combine discursive and non-discursive elements in her essay on gender representations. Her first pictures all showed posters, stickers and advertisements that illustrate how gender is expressed in public space, such as a stereotypical wedding fair announcementFootnote5 and a “Goys ‘n’ Birls” sticker criticizing the binary way society still perceives gender. Her final picture, however, also illustrated non-discursive gender representations in Schöneberg, the gay neighbourhood of Berlin (). According to Sera, “on the one hand this picture shows a progressive view of gender. The photographed woman is working, something that was not the norm in the nuclear family, in which the female was supposed to engage in housemaking (…). Moreover, the picture shows a gay store, which indicates that the city is not only built by the heterosexual for the heterosexual (…). However, one can argue that the work that the woman does is stereotypical for a woman. She cares for children, a job that is seen as typically female, because it involves emotion and taking care of the upbringing (…) Moreover, Brunos is a store by and for gay men, but it is not marketing (lesbian) women at all.”

Figure 6. A female child-carer in Schöneberg, showing a rainbow-coloured Berlin bear in front of Germany’s biggest gay store (Sera Turan. Oct. 2018).

What the above cases show is, how all students linked their way of looking to the literature discussed class, or in Pyyri’s words (Citation2018, p. 321), they let “the world ‘speak back’ to theory.” Classic sources such as Simmel’s “The Metropolis and Mental Life” inspired them to be sensitive to the visual and invisible stimuli, and motivated them to take pictures of blasé people in the metro-trains, playing with their smartphones, and ignoring the mini-performances of street musicians in the metro. But also in general through their intensified way of looking they have become aware that urban theory is not just a play with words about the city, but actually materializes and can be observed in multi-modal ways while doing urban fieldwork. As such, they certainly succeeded in achieving our course objective: to describe and interpret different theoretical concepts, approaches, and methods regarding contemporary cities, urbanization and urban policies and to apply them to real-life cases.

Conclusions

We could continue to discuss many more themes of student essays written in the past decade within the framework of our Urban and Cultural Geography course. They would all reveal similar stories of how our students tried to picture certain theoretical notions discussed in class. The photographic essay has undoubtedly stimulated their “geographical gaze” and increased their awareness of urban processes, by “looking with intention” and linking theory to empirical practice. Also, it allows students to acknowledge the multimodality of the city, not just as built environment but also as a social sphere and lived place. Indeed, “attuning to the city with a concept in mind, and a camera lens as a frame, directs attention to details that would otherwise easily pass unnoticed” (Pyyry, Citation2018, p. 316).

Of course, this form of assessment has its limitations, but we believe they are outweighed by the enthusiasm, enchantment, and theoretical and empirical insights it brings into the classroom. Moreover, some limitations (e.g. pictures being partial, subjective, etc.) are resolvable by stimulating reflexive thinking, as also suggested by Hall (Citation2009), although writing these critical reflections remains challenging for our students. Nevertheless, there are certain learning outcomes to be drawn regarding the photographic essay as a didactical tool.

Similar to Sanders (Citation2007, p. 191), we mostly struggled with using the photographic essay as form of assessment: “The decision to give students carte blanche in terms of how they demonstrated mastery of the subject matter was most problematic. At best, the assessment was value laden, contained a measure of imprecision and raised as many questions as it answered. At worst, it was purely subjective.” We also give our students carte blanche, as long as their topic is somehow related to the course material. This implies we only assess a particular subset of the student’s knowledge of the literature and lectures. Moreover, does a high grade truly reflect good mastery of course material (in terms of content), or rather good writing and photography skills (in terms of presentation and argumentation)? As mentioned above, we try to disregard the photographs’ quality by looking at them as pieces of social science data, but we are aware that the act of evaluating photographs can be as subjective as taking them. Our solution to these problems is twofold; to compare our assessments of student’s work and to combine the essay with other assessment practices (seminar and walking tour), which also promotes inclusivity and accommodates varying learning experiences. Both solutions, however, are labour intensive in terms of grading: requiring multiple assignments and multiple assessors. One way to reduce this workload would be to have students write their photographic essay in pairs or teams. This could potentially also stimulate increased dialogue amongst students about their observations and experiences (see Davies et al., Citation2019 on how sharing fieldwork pictures through Instagram triggered class discussions). However, we felt that our Master students should also be granted the opportunity to explore their own individual interests, especially after already collaborating in groups during the seminars and walking tours.

Over the years, the average grades of the essays as well as evaluations of the clearness of assessment criteria have increased (). As discussed above, this could be the result of communicating our expectations more elaborately by means of evaluation rubrics and providing examples of previous photographic essays. From the students’ perspective, another possible explanation for higher grades could be that they have become more multimodal over time; being more experienced with using cameras and visual representations themselves, “given how ubiquitous photographs have become in contemporary society” (Davies et al., Citation2019, p. 15).

It remains difficult to tackle the other point of criticism students raised regarding the essay: limited time available to take pictures during the fieldtrip. Due to budget constraints and the timing of other adjoining courses, we cannot stay longer than 4 days in Berlin, which includes travelling time and (the preparation of) walking tours. Sidaway (Citation2002, p. 97) also observed that “there has been a move to shorter field courses, higher on active student participation and critical reflection.” While the latter two seem favourable developments, they are seemingly in contradiction to the former. In any case, the short time available limits our students to rethink and revisit, which is crucial according to Sanders (Citation2007, p. 190–91, original emphasis): “initial encounters are naive, visceral and frequently lack sophistication and critical appraisal. What we gain from them is often instinctive and a quick read. In order to marry what we study in the classroom with what we see in a place, the rethinking and revisiting that seemed so arduous was actually essential.” We try to overcome this limitation by repeatedly stressing the importance of preparation, including the selection of a certain topic and reading (additional) literature before going to Berlin. The success of using photographic essay as didactical tools thus depends on clear instructions, adequate preparation and a constant fine-tuning of the assignment.

Interestingly, the use of visual images appears to be limited to geographical fieldwork. Most studies on photography as a pedagogical tool discuss how it is used as part of international field courses (e.g. Latham & McCormack, Citation2007, Citation2009). Photography as research method appears less common in courses without fieldtrips as well as in “methodologically conservative” bachelor and master thesis writing, while being even scarcer in published geographic scholarship. This especially applies to the use of new techniques offered by digital photography and social media platforms: “a rift has opened up between the visual practices used in wider society and the way photography is utilized by critical geographers, and in education” (Davies et al., Citation2019, p. 2). Not only is there a disconnection between society and academics, but also between what and how we teach visual methods to our students and how we actually do research ourselves – of course with some exceptions. Our positive experiences with using photography in our master course should hence not only be understood as evidence of photography as a pedagogical tool, but also as a call for academics – including ourselves – to also adopt it more in our own work, beyond teaching. After all, why limit its benefits to students only?

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all Master students that joined us to Berlin in the past decade for their interesting photographic essays, on which we have based this article. We have obtained permission to reproduce the pictures used in this paper. Thanks also to the journal editors and reviewers for their comments and advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. See Davies et al. (Citation2019, p. 5) for statistics on the active users of popular social media platforms, including Instagram and SnapChat. Each has over 300 million monthly active users, while only being launched in 2010 and 2011 respectively, illustrating the quick rise of these social media platforms.

2. Illustrating this quick development is Sidaway’s (Citation2002) description of the practicalities of his field course to Barcelona in 2000 and 2001, during which he provided his students with disposable, single-use cameras. Only a few years later, almost all students possess mobile phones capable of making good-quality pictures. See also Welsh et al. (Citation2012) on changes in student mobile ownership since 2009 and how this has opened up innovative field techniques such as geotagging photographs.

3. This is rather specific for social sciences; in, for example, the natural and technical sciences new visualization techniques and their interpretation are gaining importance. This lagging behind in geography is probably partly due to a lack of technical skills and underequipped research facilities, which in their turn can be traced back to the dominance of language-based data sources.

4. As of 2018, we are using the second edition of Hubbard’s book. In this updated and extended version, Hubbard uses a somewhat different structure and chapter titles, but it still revolves around a number of perspectives or “cities”: divided, world, superdiverse, gendered, queer, represented, post-human and lived cities.

5. The completely pink poster for the Hochzeitsmesse shows a rather normative picture of a wedding couple on a bicycle, with the man biking and taking the lead while the female sits on the rack. It does not reflect the diversity of (same-sex) couples planning to marry. Moreover, the poster was hanging next to an advertisement for a baby fair. Although this could be coincidental, the posters combined represent the dominant idea of a nuclear family consisting of a man and woman, expecting to get a child after marriage.

References

- Acton, M. (1997). Learning to look at paintings. London: Routledge.

- Alerby, E., & Bergmark, U. (2012). What can an image tell? Challenges and benefits of using visual arts as a research method to voice lived experiences of students and teachers. Journal of Arts and Humanities, 1(1), 95–103.

- Benjamin, W. (1999). The arcades project. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Bernardt, C., Huigen, P. P. P., & Van Hoven, B. (forthcoming) Ethnographic sketching: a critical view of Dutch border-space. To be submitted to Ethnography.

- Boria, E. (2013). Geographers and maps: A relationship in crisis. L’Espace Politique, 21(3). doi:10.4000/espacepolitique.2802

- Burckhardt, L. (1998). Strollology: A new science [Promenadologie – Eine neue Wissenschaft]. Passagen/Passages, 24, 3–5.

- Carusi, A. (2012). Making the visual visible in philosophy of science. Visual Representation and Science, 6(1), 106–114.

- Coe, N. M., & Smyth, F. M. (2010). Students as tour guides: Innovation in fieldwork assessment. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 34(1), 125–139.

- Davies, T., Lorne, C., & Sealey-Huggins, L. (2019). Instagram photography and the geography field course: Snapshots from Berlin. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 43, 362–383.

- Dowling, R., Lloyd, K., & Suchet-Pearson, S. (2018). Qualitative methods 3: Experimenting, picturing, sensing. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 779–788.

- Dummer, T. J. B., Cook, I. G., Parker, S. L., Barrett, G. A., & Hull, A. P. (2008). Promoting and assessing ‘deep learning’ in geographical fieldwork: An evaluation of reflective field diaries. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 32(3), 459–479.

- Evagorou, M., Erduran, S., & Mäntylä, T. (2015). The role of visual representations in scientific practices: From conceptual understanding and knowledge generation to ‘seeing’ how science works. International Journal of STEM Education, 2(11), 1–13.

- Glass, M. R. (2014). Encouraging reflexivity in urban geography fieldwork: Study abroad experiences in Singapore and Malaysia. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 38(1), 69–85.

- Hall, T. (2009). The camera never lies? Photographic research methods in human geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 33(3), 453–462.

- Hall, T. (2015). Reframing photographic research methods in human geography: A long-term reflection. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 39(3), 328–342.

- Hope, M. (2009). The importance of direct experience: A philosophical defence of fieldwork in human geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 33(2), 169–182.

- Hubbard, P. (2006/2018). City. London: Routledge.

- Jonas, H. (1966). The nobility of sight: A study in the phenomenology of the senses. In H. Jonas (Ed.), The phenomenon of life: Towards a philosophical biology (pp. 135–156). New York: Harper and Row.

- Klingensmith, K. (2016). In appropriate distance: The ethics of the photographic essay. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Latham, A., & McCormack, D. P. (2007). Digital photography and web-based assignments in an urban field course: Snapshots from Berlin. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 31(2), 241–256.

- Latham, A., & McCormack, D. P. (2009). Thinking with images in non-representational cities: Vignettes from Berlin. Area, 41(3), 252–262.

- Latour, B., & Hermant, E. (1998). Paris: Invisible city. Retrieved from http://www.bruno-latour.fr/virtual/EN/index.html.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Lemmons, K. K., Brannstrom, C., & Hurd, D. (2014). Exposing students to repeat photography: increasing cultural understanding on a short-term study abroad. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 38(1), 86–105.

- Levin, D. M. (ed.). (1993). Modernity and the hegemony of vision. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lewis, P. K. (1979). Axioms for reading the landscape: Some guides to the American scene. In D. W. Meinig (Ed.), The interpretation of ordinary landscapes (pp. 11–32). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Noland, C. M. (2006). Auto-photography as research practice: Identity and self-esteem research. Journal of Research Practice, 2(1), 1–19.

- Phillips, R. (2015). Playful and multi-sensory fieldwork: Seeing, hearing and touching New York. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 39(4), 617–629.

- Pyyry, N. (2016). Learning with the city via enchantment: Photo-walks as creative encounters. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 37(1), 102–115.

- Pyyry, N. (2018). From psychogeography to hanging-out-knowing: Situationist derive in nonrepresentational urban research. Area, 51(2), 315–323.

- Rose, G. (2001). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. London: Sage.

- Rose, G. (2008). Using photographs as illustrations in human geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 32(1), 151–160.

- Sanders, R. (2007). Developing geographers through photography: Enlarging concepts. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 31(1), 181–195.

- Sawchuk, K. (2014). Impaired. In D. Hannam, P. Adey, M. Sheller, K. Merriman, & D. Bissell (Eds.), The routledge handbook of mobilities (pp. 409–420). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Scarles, C. (2013). The ethics of tourist photography: Tourists’ experiences of photographing locals in Peru. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31(5), 897–917.

- Shields, R. (1996). A guide to urban representation and what to do about it: Alternative traditions of urban theory. In A. D. King (Ed.), Re-presenting the city: Ethnicity, capital and culture in the twenty-first century metropolis (pp. 227–252). New York: New York University Press.

- Sidaway, J. D. (2002). Photography as geographical fieldwork. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 26(1), 95–103.

- Simm, D., & Marvell, A. (2015). Gaining a “sense of place”: Students’affective experiences of place leading to transformative learning on international fieldwork. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 39(4), 595–616.

- Taylor, A., Blaise, M., & Giugni, M. (2013). Haraway’s ‘bag lady story-telling’: relocating childhood and learning within a ‘post-human landscape’. Discourse: studies in the cultural politics of education, 34(1), 48–62.

- Urry, J. (1990). The tourist gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary societies. London: Sage.

- Watt, S., & Wakefield, C. (eds.). (2017). Teaching visual methods in the social sciences. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Welsh, K. E., France, D., Whalley, W. B., & Park, J. R. (2012). Geotagging photographs in student fieldwork. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 36(3), 469–480.

- Nairn, K. (2005). The problems of utilizing ‘direct experience’ in geography education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 29(2), 293–309.