ABSTRACT

This article explores the teaching of atmosphere for undergraduate geography students. Though many scholars have observed an “atmospheric turn” in the discipline, teaching atmosphere in human geography has received less attention. To this end, the article examines the design and delivery of a “floating workshop” that engaged students in thinking and feeling the meteorological and affective qualities of atmosphere. Practically, the floating workshop involved the preparation, launch and floating of two solar-powered balloon-like sculptures made by the international artistic community Aerocene. In contrast to practices of mapping or remote sensing with aerial devices like kites or drones that are familiar to geographical pedagogy, this creative practice-based workshop foregrounded sensual and affective observations of atmosphere, from the feeling of wind speeds to the transmission of emotions. This shared atmospheric experience and pedagogical experiment linked theory with practice, activated situated learning processes, and generated critical inquiry into the affective, aesthetic and material dimensions of air and atmosphere.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

I am standing on a rugby field watching a group of students inflate two large, tetrahedral balloons. The students run up and down the field in pairs, holding the “mouth” of each balloon open to the air, then they quickly close it and wait. It is a crisp, sunny day in February. Though the wind is gentle, it easily pushes and pulls the membranes around, causing students to shout in excitement and anticipation. Slowly, one of the balloons begins to levitate off the ground. Its sudden weightlessness sparks surprise and trepidation; it is floating in space without an engine, propeller, or heat-making flame. “It’s like a sea creature!” a student exclaims, as others circle around, holding the creature safely to earth.

This is a scene I have witnessed repeatedly over five years teaching the undergraduate human geography course Atmospheres: Natures, Cultures, Politics at Royal Holloway University of London. In this scene, geography students participate in a series of hands-on, creative, and collaborative practices to better understand the materiality and geography of atmosphere. Together they arrive at a specific set of learnings on atmosphere through shared sensual and affective experiences of floating. As many other pedagogical scholars have shown, sensual and affective encounters are key to inquiry-based teaching in the field (Cook, Citation2008; Herrick, Citation2010) and the classroom (Healey, Citation2005; Spronken-Smith et al., Citation2008). In this paper, I show how workshop-based methods for sensing atmosphere can inform the inquiry-based toolkits of geographical pedagogy.

More specifically, I assess the role of an in-class “floating workshop” for student-led inquiry on the material and affective dimensions of atmosphere. The affective and the atmospheric have sparked important discussions in human geography of late (e.g. B. Anderson, Citation2009; Edensor, Citation2012; McCormack, Citation2008; Sumartojo & Pink, Citation2018). In an article on “fieldworking with atmospheric bodies”, McCormack advances the notion of atmosphere as a sensual field of experience and experiment rather than the “forgotten” or “negative” space above the materiality of the ground (2010; see also Jackson and Fannin, Citation2011). Yet, the relationships between affect and atmosphere remain difficult to grasp for scholars and students alike. Much is made of the entanglement of the meteorological (the physical, material atmosphere) and the affective (the atmosphere as it is felt, sensed, embodied) (Adams-Hutcheson, Citation2019; Engelmann, Citation2021) yet students have difficulty with these ideas in scholarly papers. Though literature on atmospheres is some of the most theoretically dense in the field, students’ struggles with these concepts are not reducible to the style in which they are written. The forgetting of atmospheres is not helped by styles of teaching that privilege the cognitive and the kinetic (e.g. Anderson et al., Citation2001; Bloom, Citation1956) over the affective and experiential. As Brigstocke (Citation2020) shows, affective atmospheres can be staged, manipulated and evaluated in the lecture hall, complicating the binary of inside/outside and cognitive/affective in pedagogical literatures. At the same time, a growing group of practitioners across human and physical geography are using hands-on, creative and collaborative practices to demonstrate the value of sensuality and affect in learning spaces (Bagelman & Bagelman, Citation2016; Boyle et al., Citation2007; Holton, Citation2017; Simm & Marvell, Citation2015). Learning from this work, how might pedagogical practices foreground the sensuality of atmospheric conditions? How might the atmosphere become the site and vehicle for affective encounters, and for critical inquiry into the relations between bodies, atmospheric things and the elemental conditions in which they are immersed?

Asking these questions led me to design a workshop on floating for my undergraduate students. Through the observation of floating in outdoor weather conditions, I hoped to catalyse insights on the entanglement of materiality and affect in the atmosphere, including how affective experiences link to wider experiences of weather and climate in “climate-affective atmospheres” (Verlie, Citation2019). Inspired by the value of the balloon, “as a lure for thinking and feeling atmospheres in both a meteorological and an affective sense” (McCormack, Citation2014, p. 609) the workshop draws from the lighter-than-air practices of an initiative called Aerocene led by the Berlin-based artist Tomás Saraceno. Aerocene is an artistic project and community working to unravel the feedback loops of global aeromobility, fossil fuel extraction and advanced capitalism (Engelmann, Citation2020; Saraceno, Citation2015). The term Aerocene gestures to a speculative epoch in which humans have developed a more careful, ethical orientation to atmosphere. The project takes concrete shape in Aerocene sculptures: absorbent, balloon-like, often tetrahedral envelopes made of fabric, mylar, or plastic that can float using only the energy of the sun and the air. These sculptures are packaged in hand-sewn backpacks called Aerocene Float Kits together with rope, gloves, a floating manual and a Raspberry-Pi payload. Aerocene sculptures have been launched all over the world, and have reached altitudes of over 21 km (Engelmann, Citation2021). The emergence of this project and its global community of practice formed a key aspect of my doctoral dissertation, carried out in collaboration with Studio Tomás Saraceno between 2013 and 2016 (Engelmann, Citation2017). While conducting fieldwork I taught undergraduate and postgraduate workshops on making, launching and flying Aerocene sculptures. This experience, and my embeddedness in the Aerocene Community, gave me the access and skillset to tailor a workshop using Aerocene sculptures for undergraduate geography students. Yet, as I learned in the process and will show in this article, there are a range of ways affective-meteorological atmospheres can be taught and engaged without direct access to Aerocene’s specific practices and networks.

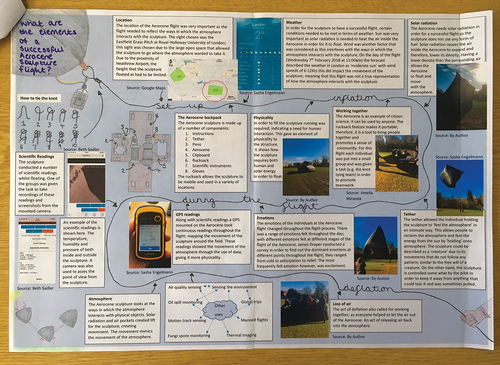

In this article, I draw from a specific occasion of a floating workshop involving thirty-eight third-year undergraduate students at Royal Holloway University of London within the framework of the advanced-level module, Atmospheres: Nature, Culture, Politics. The module traces the complex geographies of atmospheric space in lecture-style teaching, small group seminars and two in-class workshops. In addition to content-driven objectives, the course learning outcomes include the evolution of capacities to observe, sense and engage with atmosphere using practical and aesthetic approaches. To this end, the two workshops challenge students to hone their capacities of atmospheric sensing through group-based experiments. These workshops are linked to one assessment called the “practice portfolio”. As an alternative assessment format, the portfolio challenges students to present their affective, sensual and material engagements with atmosphere in visually rich and narrative ways, and as such may offer a creative alternative to field diaries and journals in other pedagogical spaces. To examine and evaluate students’ experiences of the floating workshop I reference personal communications with students and staff during and after the workshop; student feedback in small-group seminars; feedback from an independent staff peer observer; students’ assessments; an anonymous post-hoc survey; and a final class discussion. I find that the workshop was generative of observations and encounters as well as thrills and anxieties that contributed to diverse understandings of atmospheric conditions. The performance of the workshop, rather than the collection of objective data, was central to the inquiry, and to the reflective materials it generated. Before addressing these in greater detail, in section I further contextualize the floating workshop in geographical pedagogies and literatures.

Atmospheric attunements and inquiry-led pedagogies

What might a pedagogy of atmospheres look like? How does thinking and feeling atmospheres extend well-worn traditions of situated and inquiry-based learning? Bonastra and Jové have recently called for “learning atmospheres”, proposing that the careful construction of context, site-specificity and the use of aesthetic materials may produce, “situated, embodied, imaginative and emotional educational practices” (2022: 385). These authors advocate for the importance of artworks in staging speculative and immersive experiences that can inform critical reflection on place and space (Bonastra and Jové, Citation2022). While a thorough discussion of artistic methods for teaching atmospheres is beyond the scope of this article, the workshop-based methods presented here are what Erin Manning calls “artful” (Manning, Citation2016). Manning elaborates:

Artful practices honor complex forms of knowing and are collective not because they are operated upon by several people, but because they make apparent, in the way they come to a problem, that knowledge at its core is collective. (Manning, Citation2016, p. 13)

As I will show, artful practices including, but not limited to those of artistic communities like Aerocene, foreground the collectivity of knowledge making as a form of situated, inquiry-based learning. The floating workshop is thus legible not only as an artful intervention in a geography module, but also as an experiment in “learning by doing”. It is precisely the cross-legibility of this workshop that renders it suitable for geographical pedagogy invested in atmosphere.

The value of a floating workshop and teaching on atmospheres for situated and inquiry-based learning can be gleaned by returning to the ideas that have animated this conversation in the field. In Situated Learning (Lave et al., Citation1991) Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger assert that learning is inseparable from personal transformation within communities of practice. Thinking with the practices of midwives, Liberian tailors and naval quartermasters, the authors argue that learning occurs when peripheral participants gain skills in close collaboration with each other and with experienced experts (Lave et al., Citation1991). Intrinsic to this argument is the claim that traditional forms of lecture and classroom-based learning, which foreground, “the exchange value of learning independently of its use value” (Lave et al., Citation1991, p. 112) separate students from conditions that test, extend and amplify learning outcomes. Learning, for these authors, is therefore a social phenomenon and participation is key. For Lave, “Doing and knowing are inventive … They are open-ended processes of improvisation with the social, material, and experiential resources at hand” (Lave, Citation2009, p. 204). Numerous scholars have foregrounded the value of open-endedness and experimentality in researching atmospheres (Ash & Anderson, Citation2015; Bremner, Citation2022; Shapiro, Citation2015; Sumartojo & Pink, Citation2018). As I will show, teaching in and with atmospheres requires improvisation and resourcefulness of students and teachers alike.

Statements on the value of learning by doing are common in geographical pedagogy. Cook (Citation2008) emphasizes “active learning scenarios” that facilitate self-awareness in field sites, while Herrick (Citation2010) argues that field-based experiences encourage “deep learning” measured by students’ increased participation in autonomous research. Boyle et al. (Citation2007) survey the relations between cognitive and affective learning during field trips, finding that the affective is crucial to students’ achievements, growth and learning capacities. Savin-Baden (Citation2008) advocates placing students outside of their “comfort zones” in field contexts that can enable “borderland spaces” of learning. This literature resounds in its advocacy for learning-by-doing (Hefferan et al., Citation2002), applying theory to practice, and exposing students to the rich and challenging textures of place, practice and research.

Among recent contributions to inquiry-based learning in geography, there is an active conversation focused on group-based experiments with aerial objects such as kites (e.g. Pánek et al., Citation2018; Sander, Citation2014), drones (Birtchnell & Gibson, Citation2015) and balloons (e.Mountrakis & Triantakonstantis, Citation2012; see also Warren, Citation2010). Given the rise of digital maker-culture, critiques of corporate remote sensing, and the increasing availability of drones in geography departments, this trend is unsurprising. Notable emphases are placed on the dramas of temperamental flying objects. In Pánek et al. (Citation2018) we read of the affective experience of a kite plummeting into the sea with a camera on board, while in Mountrakis and Triantakonstantis (Citation2012) the risk of “catastrophic failure” becomes a powerful animating force for the balloon launch. Such accounts resonate with Ingold’s (Citation2010) work in cultural anthropology on the making and flying of kites with postgraduate students. Ingold finds that teaching and learning in-the-air requires a sensitive agility. Yet Ingold’s (Citation2010) work differs from the aforementioned authors in its empirical focus, which is not on what kites can do for geography or cartography, but on the material entanglements of humans and aerial things. Ingold elaborates:

[the] flyer and kite should be understood not as interacting entities, alternately playing agent to the other as patient, but as trajectories of movement, responding to one another in counterpoint, alternately as melody and refrain. (Ingold, Citation2010, p. 96; my emphasis)

The experience of these trajectories of movement and their reflections in bodies, tethers and aerial things are the learning outcomes of Ingold’s pedagogical experiments with kites (2010). Though the flying of kites differs from the floating of balloons, notions of entanglement, melody and refrain, and trajectories of movement among bodies and atmospheres echo into my account of the floating workshop.

The workshop assessed in this paper reflects aspects of 1) situated learning in which students acquire skills from community experts, and 2) inquiry-based learning using atmospheric objects and methods. As a situated practice, the workshop is founded on the skillful work of the Aerocene Community. During preparatory sessions as well as the workshop itself, two “expert” Aerocene Community members acted as co-instructors. They supported students in the hands-on practices at the core of the workshop and facilitated students’ understanding of the process of floating. The inquiry at the heart of this workshop is the following: how can the floating of a solar-powered wind-driven entity (an Aerocene sculpture) expand our sensory and affective awareness of atmosphere? This inquiry differs somewhat from those proposed by scholars like Roberts (Citation2013), in which students examine data and source material from within the classroom to negotiate geographical questions. My students’ engagements with geographical materials took place outside of the classroom, in the doing of an atmospheric experiment. Yet, in line with Roberts’ notions of inquiry-based learning, students made “sense of information for themselves in order to develop their understanding” and reflected on their learning (Roberts, Citation2013, p. 50). In foregrounding, the affective and sensual over the cartographic and quantitative, the inquiry of the floating workshop also differed from the other balloon, drone and kite-based inquiries. Instead, and in resonance with Ingold (Citation2010), the floating workshop activated the imagination of students through positioning the Aerocene launch as a speculative performance of humans, atmospheres and aerial things.

In the following two sections I turn to the methodology of delivering and teaching the workshop. First, I narrate the classroom-based preparation. Second, I give an account of the floating workshop, drawing from my observations and those of students, an independent staff observer and two Aerocene Community experts. Finally, I summon student and staff voices and draw selections from students’ “practice portfolio” assessments to evaluate the workshop as an experiment in inquiry-based teaching and learning on atmosphere.

The floating workshop

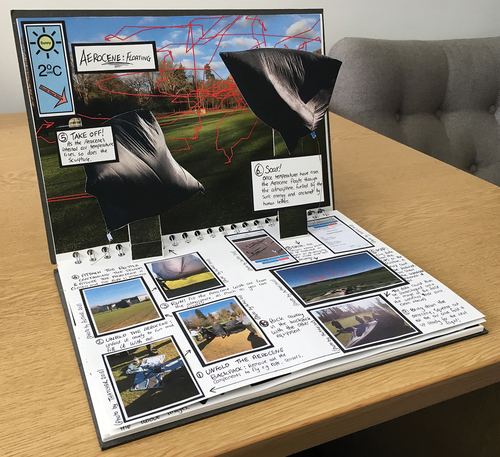

In my human geography module, the floating workshop manifested students’ first attempts at situated and inquiry-based learning. I introduced the Aerocene project in a preparatory one-hour lecture. I then divided the class into two 18-person groups who would each work with one of the Aerocene Float Kits. A member of the Aerocene network – Grace Pappas – was present throughout this session. The aim of the second hour of group-based preparation was to familiarize students with the components of the Aerocene kit through unpacking and handling individual parts; to divide each group into smaller (2–4 persons) teams who would be responsible for specific aspects of the Aerocene launch; and to facilitate some experience with tasks such as knot-tying and payload readying. The smaller teams included: the weather team; the inflation team; the payload team; the knot team; the float team; and the deflation team.

In the intervening week between this initial session and the workshop, the teams continued to prepare. For example, the “weather teams” were responsible for monitoring the weather conditions. Through the Aerocene manuals, they had been instructed in the basic criteria of assessing weather for floating via solar irradiance, wind speed and cloud cover, among other factors. They sent updates to the class throughout the week. Indeed, the weather conditions were a crucial concern, since the floating of the solar-powered Aerocene sculptures would be precluded by rain, snow, or too much wind. The conditions of teaching in this case were weather-dependent, a lesson that I urged students to reflect on.Footnote1 We were lucky, however, and the day of the proposed floating workshop was clear, sunny and cold, with light winds of 6–7 kilometers per hour.

As we assembled in the classroom on the day of the workshop, I introduced another long-term member of the Aerocene community, the artist Jol Thoms. Thoms worked at Studio Tomás Saraceno between 2009 and 2014, was involved in the prototyping of early Aerocene sculptures, and had flown many sculptures in different parts of the world. Then, I requested the weather teams to offer a “report”. Their atmospheric diagnoses were favourable while recommending special caution to gusts of wind. We packed our belongings and processed out of the department to the sports field where I had acquired permission to conduct the workshop.

When we arrived at the field, the class divided: one group followed Thoms to one end of the field, while I stayed with the second group. As some students unpacked the kit, the inflation team began filling the large black fabric envelope with air by running up and down the field, holding the “mouth” of the sculpture open to the wind (see ). A good inflation is crucial so that the sculpture contains enough air to generate lift. Students’ reactions were of visible excitement, thrill, surprise and exhilaration. The team members exclaimed, “We didn’t expect it to be so big!” (Student A) and “it’s incredibly powerful!” (Student B). Another student commented, “I was astounded by its simplicity” (Student C). As inflation progressed, the payload team activated the solar-powered battery contained in the Aerocene Float Kit and connected it to the Raspberry Pi microcontroller inside a plastic water bottle. They positioned the Raspberry Pi Camera on a ribbon that hung outside of the bottle and fixed to the bottom. The “knot team” then carefully tied the entire payload to a strong black tether using several repetitions of the required non-slip knot. By this time the inflation team had sealed the sculpture’s “mouth” shut. The teams approached each other as the Aerocene membrane rippled with wind currents, towering two meters above the students’ heads. The excitement was expressed in laughter and hurried questions as students attached the payload to a loop on the edge of the moving membrane. Hands, cameras, rope, payload, membrane, sun and wind – all of these mingled and moved in a “‘hive of activity’” (Ingold, Citation2007, p. 317), “energised by the flows of materials, including the currents of air, that course through the body” (Ingold, Citation2010, p. 96).

Figure 1. A still image from a video of students inflating one of the Aerocene sculptures, video made by a student. Courtesy of the author.

Once the payload was securely attached to the edge of the Aerocene sculpture, and all knots were checked several times, the “float team” donned the white gloves needed for safely holding the tether. Ideally, one participant holds the rope near the sculpture and focuses on its movements, while the second holds the rope spool, making sure there is enough line. Because the Aerocene sculpture at this stage was part aerostatic object and part kite, the students had to be highly attentive. As Thoms instructed, they needed to move around the field, allowing the Aerocene sculpture to find rising air pockets. In other words, humans and Aerocene sculptures “dance” as they “hold on to the force of the sun” (Thoms, Citation2018: np; See ). As in Mountrakis and Triantakonstantis (Citation2012) account of a student-led helium balloon launch, light-hearted behavior gave way to constructive criticism and the possibility of “catastrophic failure” became palpable. The situation had the texture of what Stengers calls a “cosmic event”: “[an] achievement in the ecology of practice … which does not depend on humans only, but on humans as belonging” to an energetic, more-than-human milieu (Stengers, Citation2013, p. 192). In this case, students’ actions were contingent upon, and collaborating with, the micro-eddies, northeasterly currents and collective affects of a shared atmosphere.

Due to the absence of carbon-based fuel, hydrogen or helium gas, an Aerocene launch is a slow process. The sculptures slowly begin to lift and bounce into the air as photons cascade into the black fabric and warm the volume of air inside, making it less dense than the surrounding air. Wind pulls the membrane in myriad different directions. It can take an hour or more for upward motion to be achieved. Everything depends on the quality of preparation, on the specific atmospheric and solar conditions, and on the attentions of human bodies. An English-department lecturer who had come to the class to assess my teaching noted in her comments that most students remained engaged, even those, “who might have been a bit ‘giddy’ to be out of the classroom” (Peer Observer, Citation2018: np). When the sculptures rose higher into the air, cheers, smiles and claps erupted spontaneously. The rise and fall of the sculptures were caught up in the rise and fall of emotion and sensation. Tethers and invisible lines of movement connected bodies to the aerostatic envelopes. The fact that there were two sculptures flying simultaneously engendered the observation that they were like “buoyant aliens”, writhing and fluttering in an “ocean of air” (Student D). In this way among others, the affective and the meteorological dimensions of atmosphere were both conceptually and materially entangled.

In the Department of Geography at Royal Holloway, students begin to learn about atmospheres in their second year. Understanding atmospheres is important for a variety of reasons, not least among them the capacity to grasp differences, intensities and “densities” in space and place (McCormack, Citation2010). To facilitate “learning atmospheres” during the course of the workshop, Thoms and I instructed students to observe the styles of floating exhibited by the Aerocene sculptures, the affective qualities of the event, and the relations between human participants, atmosphere and the flying sculptures. They were also invited to record images from the airborne Raspberry Pi camera, and to monitor the pressure and temperature sensors inside and outside the membranes.Footnote2 These materials would inform the completion of their practice portfolio assessments (to be discussed further in the next section). Some student observations took unusual styles: one student set up a large format black and white camera. His prints and negatives, presented the following day in small group seminars, were both visually stunning and evocative of the texture of the event in ways that differed from many phone-generated images (see ).

Figure 3. A photograph of the Floating Workshop taken by a student with a large format black and white camera. February 7th 2018. Courtesy of the author.

The workshop was not free of disaster. While changing float teams, one of the Aerocene sculptures was lifted in a high arc over the field and came suddenly hurtling down onto a fence. The student who was flying the sculpture was taken by surprise, and before Thoms or I could help, the sculpture’s fabric had torn. This happened close to the end of the workshop, so the emotional investment in this failure was high. Once we deflated and packed the sculptures away, we gathered in a circle on the field, and discussed how to approach the tear: was it a failure? An opportunity? A lure for thinking about the atmospheric conditions? In fact the patching of Aerocene membranes is central to this community of practice in which such ruptures are very common. Nevertheless, this was a moment in which the “anterior” (Adey, Citation2015) or “excessive” (McCormack, Citation2018) dimensions of atmosphere were forced into the teaching experience, disrupting any remaining assumption that we were in control. The importance of this occurrence will be further discussed in the evaluation of the workshop, following a summary of evaluative techniques.

Floating workshop evaluation

Evaluation of this workshop, and assessment of its value for teaching on atmospheres, was carried out through a mixed methodology. Together with Pappas and Thoms I noted student engagement during the preparatory session, as well as before, during and after the workshop. The English department staff observer supplemented these observations, submitted on a peer reviewer form. Student experiences and reflections were assessed during five two-hour small group seminars that occurred in the two days immediately after the workshop. In addition, and primarily, student learning was grasped in their reflective “practice portfolio” assessments submitted at the end of the course. Finally, an anonymous in-class survey generated 22 responses that highlighted aspects of the workshop’s challenges, innovations and format. While I am not able to draw decisive comparative conclusions, I am nevertheless able to explore student engagement with the floating workshop as an inquiry-based learning endeavor. My findings suggest that students employed the workshop to inquire into the sensual, affective and meteorological qualities of atmosphere, with varying degrees of criticality, detail and depth. The performance aspect – the interactive relations of bodies and aerial things – was for many the most memorable and lasting part of the learning experience.

The practice portfolio is an alternative assessment that tests course learning outcomes connected to the two in-class workshops. These outcomes include: demonstration of capacities to observe air and atmosphere using collaborative, practical and sensory approaches; demonstration of ability to synthesize key concepts with knowledge gained from practice and observation; and effective presentation of text with visual materials. The portfolio does not have a word count; students are limited by the number of A4 pages they submit (two per workshop). Although artistic skill was not a key criteria for assessment, students were invited to employ creative methods to communicate, articulate and convey their learning. The marking criteria noted that portfolios at the distinction (first class) level, “may exhibit a high degree of visual and aesthetic sensibilities” (Engelmann, Citation2018: np). This phrasing echoes the marking criteria for reports, posters and presentations in RHUL’s geography department. Still, the novel format of the assessment and potential for creativity likely posed a challenge to some students, and may have enabled some to experiment differently than others. In all years the course has run, I have dedicated a seminar to different models the portfolios can take. As I do not have access to students’ demographic information, I cannot speak to the degree to which the ability to employ creative methods mapped on to educational, geographical or financial inequalities. However I can attest to the value students found in the option for creativity in the assessment, for which they were vocal in class surveys and in dialogue with an external examiner. Whether they featured creative practices or not, all portfolios had to be professionally and effectively presented.

In its attention to observation, reflection and synthesis, the practice portfolio assessment is similar to the “learning journals” of Moon (Citation2005) and the Reflective Field Diaries of Dummer et al. (Citation2008). The former is a writing-focused assignment that encourages repeated reflection, while the latter, “involve(s) recording, commenting upon and critically examining field observations” (Dummer et al., Citation2008, p. 461). Both assessments attempt to move students beyond passive knowledge acquisition toward analysis, synthesis and “critical reflectivity” (Nairn et al., Citation2000). The practice portfolio operates in a similar vein, yet its focus is on the sensuality and materiality of the in-class workshops, and how they lead us to think differently about atmosphere. In a relatively unusual coursework assessment such as this, students can meet difficulty in parsing what material is most relevant, and what counts as high quality work (Dummer et al., Citation2008; Luchetta, Citation2018). The use of examples to guide students is important, and yet, a degree of openness is valuable too (Luchetta, Citation2018). As I will show, despite some tendencies to rely on passive description, students’ practice portfolios evidence several effective strategies for articulating their inquiries into atmosphere.

Discussion: technical issues and participation

Given the novelty of floating Aerocene sculptures, and the strong emphasis on participation in as a situated learning endeavour, it is first important to consider students’ experiences of the workshop design, practicalities and timeline. Both groups in the class were successful in preparing, launching and flying their Aerocene sculptures. They were also successful in activating the payloads, and connecting to the Rasbperry Pi Camera, pressure and temperature sensors while the sculptures were floating. The ability to “see what the sculpture is seeing” while floating was exciting to students. In addition, the sensor readings allowed students to hypothesize on the correlation between the floating capacity of the Aerocene sculpture and the relative differences in pressure and temperature between inside and outside the membrane. The ability of the sculpture to capture atmospheric energy in its interior volume was sensed directly by students and was also grasped through sensor-generated data.

Together with Thoms and the staff peer observer, I noted the engagement of students with their assigned team tasks. One student commented:

I liked how inclusive the activity was as everyone had a chance to take part. The responsibilities given to each group were evenly balanced as everyone was able to contribute. The groups worked well together to successfully record the practical [activity] (Student E).

However, there were also moments when, given the progression of team tasks, students had to wait for the sculpture to float. The staff observer commented, “This was a challenging session for student participation, because the students were in teams with distinct tasks, not all of which could be done at once” (Peer Observer, Citation2018: np). In these interstitial moments, student engagement appeared to decrease. In a post-workshop discussion, one student wondered whether the float time of the Aerocene sculptures might be shortened for less of these interstitial moments to occur (Student F). However, due to the physics of solar-powered floating, this “slowness” is relatively unavoidable. What emerges is a question about what counts as productive participation in this workshop, and what counts as productive labour in relation to its learning outcomes. Many scholars writing on atmosphere have foregrounded pauses, glitches and periods of waiting as important to grasping atmosphere (Bissell, Citation2010; Nassar, Citation2022). If we follow this scholarship, the variety of rhythms in this workshop, from the fast-paced moments of preparation and launch, to the much slower “waiting” that occurred while the sculptures were becoming buoyant, are potentially part of the atmospheric learning. Yet keeping the student’s commentin mind, greater care is needed in thinking about how the speed and slowness of the workshop is approached and managed.

Another setback, noted earlier, was that some students were unsure of how to generate the best observational material. While some students relished the freedom to encounter the event in an open-ended, experiential fashion, for others, the question of what counted as useful observational material on atmosphere generated some speculation. One student commented, “Some people said they were unsure as to what/how the findings [from the workshop] would be applied” (Student E). Indeed this question arises in the work of Dummer et al. (Citation2008) on open-ended reflective learning and reflective fieldwork diaries. The staff observer, Thoms and I discussed various ways to mitigate these uncertainties in future, for example by creating a worksheet that would structure student observations (Peer Observer, Citation2018). While a worksheet was later implemented, I follow Luchetta (Citation2017) in my belief that a degree of uncertainty in this pedagogical experiment is valuable, since it provides fruitful grounds for student-led questioning on the kinds and qualities of documentation that matter for the inquiry at hand.

The workshop achieved another important, if unexpected, learning objective from the “disaster” of the Aerocene sculpture tear: we learned that the atmospheric conditions in which our workshop took place could overpower us. As Stengers (Citation2013) writes, we were in a position of belonging to volatile conditions rather than mastering them. In a wider sense, and especially in a time of worsening climate crisis, these atmospheric forces are the operative conditions in which learning practices are always already immersed. This is true whether we are experimenting directly in and with the meteorological-affective atmosphere, as occurred in this workshop, or whether we are focused on other questions inside the partial shelter of a classroom. In follow-up seminars students discussed that learning to sense, observe and engage with atmospheric space is learning to move with and respond to the air; it is also learning to be aware of the atmospheric and elemental conditions of all thinking, practicing and being.

Royal Holloway University is situated close to Heathrow Airport. In both Aerocene launch groups, students noted the contrast between the floating of the Aerocene sculptures and the continuous air traffic of passenger planes. A few students captured this visual juxtaposition and included these in their portfolios. The ethics of the Aerocene project, as an endeavor that seeks solar powered and wind driven flight, was imaginatively alluring for students. At the same time, students wondered, how could change in aerial infrastructures come about? How might solar, aerostatic travel intervene in carbon-based mobility regimes? How would it feel – affectively and emotionally – to travel by solar balloon? Although unresolved, such questions point to the adoption of critical stances toward techno-material, elemental and legal geographies of atmosphere that are the outcome of the learning experiences in the workshop.

Discussion: affective and atmospheric learning outcomes

In seminars, surveys and portfolios, students engaged with the links between affect and atmosphere in several key ways. One strategy employed in the portfolios was a narration of the Aerocene launch as it unfolded, linking points in the narrative to key affects, emotions and sensual observations. In this vein, students submitted portfolios that visually depicted all the steps in the Aerocene launch, and tagged, layered or highlighted these steps with affective detail (See ).

Figure 5. A sample practice portfolio employing a narrative “thread” to link steps in the preparation and launch to notable affects, emotions and observations.

In this way, relations between inflation and deflation, buoyancy and drift, affect and emotion were traced in linear, narrative or graphical ways. To add critical depth to their narrations, some students drew from the atmospheric “densities” of McCormack (Citation2010) and the “atmospheric methods” of Ash and Anderson (Citation2015), employing terminologies of “mass” and “weight” to trace the affects of the Aerocene sculptures, the clouds overhead and the agitating currents of air (Student H). A second key strategy included word-based diagrams in student portfolios. In this vein, students created hierarchies of affect and emotion (privileging those affects that seemed most dominant or repetitive) while also showing how the event generated a multiplicity of affects linked to the materiality of air and the floating sculptures. A third strategy included the submission of artwork that evoked the affective textures of the floating workshop. For example, one student wrote a piano piece with progressions that corresponded to stages in preparation, launch, floating and deflation (Student K). Another student (mentioned earlier) employed large format black and white photography to express the relations between air, humans and aerostatic bodies. This student also reflected on the sensations he experienced while observing the event through the lens of a camera, finding that the lens amplified some affects while limiting others, and linking to the work of geographers who use video to study atmosphere (Student L; J. Anderson, Citation2013; Pink et al., Citation2015). Another student followed the work of John Gillespie Magee, a World War I pilot who wrote the poem “High Flight” from 30,000 feet in altitude. This student authored a new poem that, using the poetic praxis and creative syntax of Magee, conveyed the atmosphere of the floating workshop (Student M). These examples evidence the diversity of student engagement and inquiry into the simultaneous meteorological and affective atmospheres of the floating workshop, inquiries that are nuanced in some cases through creative methods.

Another element echoing in students’ portfolios was the notion that launching Aerocene sculptures was a creative negotiation, or performance, of human bodies interacting with atmospheric flows, solar energies and landscape surfaces. In student portfolios, references to the relations of body, sun and wind were common. One student wrote:

We found that once it was in the air, the task became finding a low pressure zone where the sculpture would be allowed to rise … this exertion was welcomed, in recognizing [also] that my co-pilot and I became the alternative energy source needed to fly the sculpture (Student N).

The student highlights atmospheric dynamics as well as the energetic relations between “co-pilots” and the sculpture. Another portfolio drew a musical analogy between searching for hidden air pockets and searching for the “right note” (Student O). These examples chime with Ingold’s writing on kite flying, in which aerial things are not mute tools, but perform an agential relation to human bodies and atmospheres like a, “melody and refrain” (Ingold, Citation2010, p. 96). Thoms and Pappas’ interventions, as well as my own instructions, certainly influenced students’ notions of the workshop as sensual and choreographic. Nevertheless, students did more than repeat what we had instructed; they found other ways to articulate the affective textures of the shared atmospheric experience, which suggests they found rich resources for doing so.

Discussion: inquiry-led learning experiences

How did the floating workshop marshal an inquiry-based approach to expand sensory, affective and material awareness of atmosphere? Student responses and assessments suggest that the inquiry at the heart of the workshop – how can the floating of a solar-powered wind-driven entity expand our sensory and affective awareness of atmosphere? – provided a structure and a set of challenges that sparked collective knowledge production. One student wrote of the workshop, “It allowed [us] to … observe the relationship between the balloon, atmosphere and the sun as it altered and developed” (Student F). In a post-workshop survey, one student commented “[The floating workshop] gave an interesting insight and mode of thinking into how to interact with the atmosphere” (Survey Data, Citation2018). Evidence for the value of the inquiry can also be found in the students’ portfolios. Among the thirty-eight submissions, some students presented reflections on the Aerocene sculptures as amplifiers of atmospheric properties, including both the physicality of wind and the transmission of feelings. Others focused on the surfaces of the Aerocene sculptures that gave visual form to normally invisible aerial currents and inspired embodied reactions. Others noted how the two Aerocene sculptures exhibited different qualities of floating: the sculpture on the northern of the field had a more gentle, constant upward climb, while the one on the southernmost side was forcibly moved around by stronger gusts. For the students, there were different affective-atmospheric dimensions of working with the two floating entities.

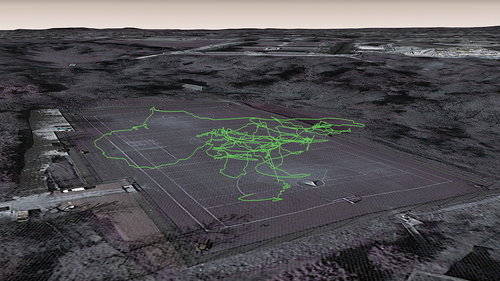

A second mode in which the inquiry of the workshop was expressed was through the optional analysis of flight data collected by a Garmin X GPS tracking device, attached to one of the sculptures. After the workshop, the data were uploaded to a shared class folder where any student could download, import to Google Earth, and explore the data (see ). In keeping with the inquiry leading the workshop, those that chose to work with the data did not treat it as purely quantitative. Some students reflected on the visual path of the sculpture as a diagram of the choreography of human bodies and wind currents. Others highlighted the “aero-poetic” or “aero-glyphic” quality of this aerial tracing (Student P; See also Aerocene, Citation2015). Some overlaid affective observations and phenomena on top of a birds-eye view of the float path, in this way mixing affective experience with the cartographic “view from above”. Still others played with the representation of the float data in sculptural forms (See ). This latter technique is especially interesting because it suggests that the student critically reflected on the data as an abstraction to be supplemented by experience. In sum, student work engaging with the GPS float data was notable for its synthesis of the sensory and affective with the quantitative and cartographic.

Figure 6. GPS float data of the Aerocene sculpture on the Southern side of launch field, Royal Holloway University, London. Image by Joaquin Ezcurra.

Figure 7. A student employs the float data as underlying infrastructure over which sculptural Aerocene sculptures move out of the page, accompanied with text boxes of reflective commentary.

A third body of work falls under the passively descriptive. Many students presented their observations in visual and textual forms without contributing further critical insight into the workshop as an atmospheric inquiry. Here there is less of an attempt to think-with the sensual materials of the experimental workshop to generate new insights, or to connect the practical observations with key concepts. Thus, there are some issues with an inquiry-led approach in that student work can remain in the realm of passive description. In other words, given the workshop’s emphasis on the affective and sensual, and the difficulty of grasping atmosphere more generally, geography students may require further support in understanding the difference between passive portrayal and critical description of atmospheric encounters.

As the diversity of student approaches might suggest, the assessment of these practice porfolios is both exciting and challenging. My confidence in assessing practice-based work is strengthened by two years of assessing portfolios in an art school in Germany. Still, it is sometimes difficult to assess students’ knowledge on atmosphere when portfolios tend toward abstraction. At the same time, the development of marking criteria specific to this assessment, and conversations with students in assessment-focused seminars have greatly supported both me and my students, and suggest that the practice portfolio is transferable to other pedagogical practices. Indeed, I have used practice portfolios to assess independent student experiments with atmosphere. They may be useful for foregrounding the affective and creative “doing” of other pedagogical exercises whether inside or outside the traditional classroom. I continue reflecting on the transferable learnings of the floating workshop in the concluding section.

Conclusion

This article has offered the case of a floating workshop to explore teaching on, in and with atmosphere. I have argued that this workshop can be read through the lens of situated and inquiry-based learning literatures, since it exposed students to a community of practice, while foregrounding inquiry into the sensual, affective and aesthetic dynamics of atmosphere. This workshop differs from other inquiry-based pedagogies in geography, and especially from other inquiry-based pedagogies with aerial things, because it was not focused on generating quantitative or cartographic data. Rather the workshop took as its empirical focus the preparation, launch and floating of solar-powered, wind driven sculptures as devices for expanding sensory and affective awareness of atmosphere.

This article is not primarily a call for geography teachers and lecturers to take up Aerocene practices in teaching atmosphere, though Aerocene Float Kits are available for borrowing at numerous institutions in the UK, Europe and Argentina among other places, and the project has open-sourced most of its resources on making and floating Aerocene sculptures. Rather, through the example of a floating workshop, I seek to generate some modest proposals for teaching atmosphere in human geography. The first of these proposals is that teaching on, in, and with atmosphere can benefit from inquiry-based experiments that highlight the entanglement of meteorological and affective atmospheres. As Verlie (Citation2019) writes, even professional scholars frequently underplay the meteorology that conditions affects, and how affects inform material experiences of atmosphere. The staging of “learning atmospheres” (Bonastra and Jové, Citation2022) may go some way in remediating this. However, given the prevalence of atmosphere in geography we can push further. For example, the now-common technique of making audio recordings on smartphones (e.g. Phillips, Citation2015) might be adapted to probe the affective-meteorological atmospheres of place. The use of paper-based methods of collage or zine-making (e.g. Bagelman & Bagelman, Citation2016) might be reoriented to draw, diagram and query the “atmospheric walls” of university classrooms (Ahmed, Citation2014).

My second proposal is to stage-learning experiences with an attention to speeds and slowness, refrains and repetitions, launches and landings. Too often teaching is condensed into content-heavy lectures and time-limited discussions. Atmospheric literatures in geography, and the experience of the floating workshop narrated in this paper, suggest that choreographing spaces of waiting, pausing or “emptiness” into inquiry-based learning exercises may aid the production of insights on atmosphere. As I have shown, this is far from straightforward for both students and teachers. In contrast to events of observational attunement figured as harmony and smooth calibration, periods of waiting or slowing may result in moments of “misattunement” that disturb, disrupt and frustrate (Zhang, Citation2020). Yet, as Zhang (Citation2020) shows, events of misattunement reveal the conditions that prefigure our abilities to sense and attune to atmospheres in the first place. Therefore, with caution and care, teaching atmospheres may benefit from multiple rhythms of doing, making and learning.

Finally, practice-led experiments like the floating workshop offer ways to foreground artfulness in geographical pedagogy beyond traditionally narrow conceptions of the creative and the artistic. Although supported and inspired by the work of an artistic community, the floating workshop did not present creativity or artfulness in a predetermined form. Rather, creativity was about learning to move, even to dance, with aerostatic envelopes, wind currents, bodies, surfaces and solar-elemental forces. In these actions, we do not read “creativity ‘backwards’, from a finished object to an initial intention in the mind of an agent” (Ingold, Citation2010, p. 91). Rather, “this [workshop] entails reading it forwards, in an ongoing generative movement that is at once itinerant, improvisatory and rhythmic” (Ingold, Citation2010, p. 91). An encounter with modes of creativity that are not limited to art-world objects may be liberating, for students as well as instructors, because it offers a window into aesthetic and material processes that transcend categories, many of which are also intrinsic to the artful practices of the discipline of geography.

Acknowledgements

My profound thanks go to my students in Atmospheres: Nature, Culture, Politics for their brilliant contributions, effervescent enthusiasm and willingness to experiment. Thank you also to the two Aerocene Community experts featured in this article, Grace Pappas and Jol Thoms. I am indebted to Tomás Saraceno for many years of collaboration and friendship, and for lending me an Aerocene Float Kit for use in my teaching in the U.K. Warm thanks to the anonymous English department peer observer who attended the floating workshop and reflected with me on its outcomes. Finally, I am grateful to my Royal Holloway Geography Department colleagues who have supported me with care and criticality in imagining, designing and evaluating an unusual creative practice-based workshop for our undergraduate students.

Disclosure statement

Sasha Engelmann completed her PhD fieldwork in the Studio of Tomás Saraceno, the founder of Aerocene. She continues to collaborate with Aerocene in her teaching and research.

Notes

1. Reflections on the weather dependency included consideration of the weather as a collaborator in the workshop; discussions of the meaning of failure; and contingency planning. If the weather conditions were not appropriate, I would have given the following week’s lecture in place of the week of the workshop, and we would have tried again one week later.

2. While the Aerocene sculpture is flying, a local Aerocene wifi network and a simple mobile phone-based browser search enables grounded viewers to see a live transmission of video and data from the Raspberry Pi on the payload.

References

- Adams-Hutcheson, G. (2019). Farming in the troposphere: Drawing together affective atmospheres and elemental geographies. Social & Cultural Geography, 20(7), 1004–1023. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1406982

- Adey, P. (2015). Air’s affinities: Geopolitics, chemical affect and the force of the elemental. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820614565871

- Aerocene. (2015). Gemini free flight. LRaunch information available at: http://aerocene.org/aug-27-schoenfelde-germany Last Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- Ahmed, S. (2014). Atmospheric walls. Feminist Killjoys [blog]. Available at: https://feministkilljoys.com/2014/09/15/atmospheric-walls/

- Anderson, B. (2009). Affective atmospheres. Emotion, Space and Society, 2(2), 77–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2009.08.005

- Anderson, J. (2013). Evaluating student-generated film as a learning tool for qualitative methods: Geographical “drifts” and the city. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 37(1), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2012.694070

- Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2021). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

- Ash, J., & Anderson, B. (2015). Atmospheric methods. In P. Vannini (Ed.), Non-representational methodologies (pp. 44–61). Routledge.

- Bagelman, J., & Bagelman, C. (2016). ZINES: Crafting change and repurposing the Neoliberal University. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 15(2), 365–392. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/1257

- Birtchnell, T., & Gibson, C. (2015). Less talk more drone: Social research with UAVs. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 39(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2014.1003799

- Bissell, D. (2010). Passenger mobilities: Affective atmospheres and the sociality of public transport. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(2), 270–289. https://doi.org/10.1068/d3909

- Bloom, B., Englehart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. In Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York, Toronto: Longmans.

- Bonastra, Q., & Jové, G. (2022). Rethinking learning contexts through the concept of atmosphere and through contemporary art. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 46(3), 383–402.

- Boyle, A., Maguire, S., Martin, A., Milsom, C., Nash, R., Rawlinson, S., Conchie, S., Turner, A., & Wurthmann, S. (2007). Fieldwork is good: The student perception and the affective domain. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 31(2), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260601063628

- Bremner, L. (Ed.). (2022). Monsoon as method: Assembling monsoonal multiplicities. Actar Publishers.

- Brigstocke, J. (2020). Experimental authority in the lecture theatre. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 44(3), 370–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2019.1698527

- Cook, V. (2008). The field as a ‘pedagogical resource’? A critical analysis of students’ affective engagement with the field environment. Environmental Education Research, 14(5), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802204395

- Data, S. (2018). A student survey in Atmospheres: Nature, Culture, Politics. Royal Holloway University of London.

- Dummer, T. J., Cook, I. G., Parker, S. L., Barrett, G. A., & Hull, A. P. (2008). Promoting and assessing ‘deep learning’ in geography fieldwork: An evaluation of reflective field diaries. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 32(3), 459–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260701728484

- Edensor, T. (2012). Illuminated atmospheres: Anticipating and reproducing the flow of affective experience in Blackpool. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 30(6), 1103–1122. https://doi.org/10.1068/d12211

- Engelmann, S. (2017). The Cosmological Aesthetics of Tomás Saraceno’s Atmospheric Experiments. ( Doctoral Dissertation) Available from the Oxford University Research Archive.

- Engelmann, S. (2018). Marking criteria for practice portfolio assessments. Royal Holloway University.

- Engelmann, S. (2020). Sensing art in the atmosphere: Elemental lures and aerosolar practices. Routledge.

- Engelmann, S. (2021). Floating feelings: Emotion in the affective-meteorological atmosphere. Emotion, Space and Society, 40, 100803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100803

- Healey, M. (2005). Linking research and teaching to benefit student learning. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 29(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260500130387

- Hefferan, K. P., Heywood, N. C., & Ritter, M. E. (2002). Integrating field trips and classroom learning into a capstone undergraduate research experience. Journal of Geography, 101(5), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340208978498

- Herrick, C. (2010). Lost in the field: Ensuring student learning in the “threatened” geography fieldtrip. Area, 42(1), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00892.x

- Holton, M. (2017). “It was amazing to see our projects come to life!” Developing affective learning during geography fieldwork through tropophilia. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 41(2), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2017.1290592

- Ingold, T. (2007). Comment. In V. O. Jorge & J. Thomas (Eds.), Overcoming the modern invention of material culture (pp. 313–317). ADECAP.

- Ingold, T. (2010). The textility of making. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 34(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep042

- Jackson, M., & Fannin, M. (2011). Letting geography fall where it may—aerographies address the elemental. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(3), 435–444.

- Lave, J. (2009). The practice of learning. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists … in their own words (pp. 200–208). Routledge.

- Lave, J., Wenger, E., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation (Vol. 521423740). Cambridge university press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

- Luchetta, S. (2018). Going beyond the grid: Literary mapping as creative reading. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 42(3), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2018.1455172

- Manning, E. (2016). The minor gesture. Duke University Press.

- McCormack, D. P. (2008). Engineering affective atmospheres on the moving geographies of the 1897 Andrée expedition. Cultural Geographies, 15(4), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474008094314

- McCormack, D. P. (2010). Fieldworking with atmospheric bodies. Performance Research, 15(4), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2010.539878

- McCormack, D. P. (2014). Atmospheric things and circumstantial excursions. Cultural Geographies, 21(4), 605–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474014522930

- McCormack, D. P. (2018). Atmospheric things: On the allure of elemental envelopment. Duke University Press.

- Moon, J. (2005). Guide for busy academics no. 4: Learning through reflection. Higher Education Academy.

- Mountrakis, G., & Triantakonstantis, D. (2012). Inquiry-based learning in remote sensing: A space balloon educational experiment. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 36(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2011.638707

- Nairn, K., Higgitt, D., & Vanneste, D. (2000). International perspectives on fieldcourses. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 24(2), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/713677382

- Nassar, A. (2022). Bridges, billboards and kites: Glitches and infrastructures in cairo’s curfews. [Paper presented at the Global Mobilities and Humanities Conference] Konkuk University, South Korea, 27-29 October 2022.

- Pánek, J., Pászto, V., & Perkins, C. (2018). Flying a kite: Playful mapping in a multidisciplinary field-course. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2018.1515190

- Peer Observer. (2018) . Reviewer teaching feedback form. Royal Holloway University.

- Phillips, R. (2015). Playful and multi-sensory fieldwork: Seeing, hearing and touching New York. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 39(4), 617–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2015.1084496

- Pink, S., Leder Mackley, K., & Moroşanu, R. (2015). Researching in atmospheres: Video and the ‘feel’of the mundane. Visual Communication, 14(3), 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357215579580

- Roberts, M. (2013). The challenge of enquiry-based learning. Teaching Geography, 38(2), 50. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/challenge-enquiry-based-learning/docview/1412593682/se-2

- Sander, L. (2014). Kite aerial photography (KAP) as a tool for field teaching. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 38(3), 425–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2014.919443

- Saraceno, T. (Ed.). (2015). Aerocene newspaper. Studio Tomás Saraceno.

- Savin-Baden, M. (2008). Learning spaces: Creating opportunities for knowledge creation in academic life. Society for Research into Higher Education/Open University Press.

- Shapiro, N. (2015). Attuning to the chemosphere: Domestic formaldehyde, bodily reasoning, and the chemical sublime. Cultural Anthropology, 30(3), 368–393. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca30.3.02

- Simm, D., & Marvell, A. (2015). Gaining a “sense of place”: Students’ affective experiences of place leading to transformative learning on international fieldwork. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 39(4), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2015.1084608

- Spronken-Smith, R. A., Bullard, J., Ray, W., Roberts, C., & Keiffer, A. (2008). Where might sand dunes be on Mars? Engaging students through inquiry-based learning in geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 32(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260701731520

- Stengers, I. (2013). Introductory notes on an ecology of practices. Cultural Studies Review, 11(1), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.5130/csr.v11i1.3459

- Sumartojo, S., & Pink, S. (2018). Atmospheres and the experiential world: Theory and methods. Routledge.

- Thoms, J. (2018). Personal communication during floating workshop.

- Verlie, B. (2019). “Climatic-affective atmospheres”: A conceptual tool for affective scholarship in a changing climate. Emotion, Space and Society, 33, 100623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2019.100623

- Warren, J. Y. (2010). Grassroots mapping: Tools for participatory and activist cartography. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Last Retrieved July 3rd, 2018: <http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/65319>

- Zhang, V. (2020). Noisy field exposures, or what comes before attunement. Cultural Geographies, 27(4), 647–664. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474020909494