ABSTRACT

Sports mega-events offer rich and varied opportunities for educating students on key concepts defining geographical ways of thinking. Concept-learning, central to students’ development, can be enhanced by issue-based enquiries that enable them to personalise and apply concepts in meaningful and memorable ways. A diverse range of activities constituting sports mega-events increases likelihood of stimulating interest among students, including those non-active in sport. This paper provides a pedagogic example to demonstrate how geography students can critically engage with their own sport interests to explore the threshold concept of place. It does so through the example of the Tour de France, a professional road cycling race. Three vignettes are presented to interweave theory and empirics, demonstrating how they might be explored using different understandings of place. The first vignette concerns mapping the Tour in relation to space and time, the second to materialities and a sense of place of a finishing line, and the third to a relational politics of place through the inclusion of Plymouth in the 1974 race. Further explorations of place are suggested through themes such as fixity, connectivity, mobility, and temporality, alongside suggestions for class discussion and deeper reflection among students. The pedagogic example provides a template applicable to other sports events.

Introduction

Sport offers rich and varied opportunities for educating geography students on key concepts that define geographical ways of thinking. Richness arises through sport’s centrality to social, cultural, economic, and political life (Bale, Citation2003; Wise & Kohe, Citation2020), as well as its ubiquity in the lives of many individuals, whether for work, health and wellbeing, or leisure and entertainment. The diverse range of activities that constitute sport increases the likelihood of stimulating interest among students. This paper uses a pedagogic example to demonstrate how geography students can critically engage with sports mega-events to develop their conceptual understanding of the foundational geographical idea of place. It relies on using sport-based enquiry to explore and apply threshold concepts in a personalised way to enhance conceptual learning (see Klein et al., Citation2019). While the Tour de France, an annual, professional road-cycling race, is used as an example, the ideas can be transferred to other sports events.

The paper draws, first, on pedagogical literature concerning threshold concepts, before distinguishing sports mega-events and their value for conceptual learning. It then outlines the sport-based enquiry, through three vignettes that serve as examples for exploring and applying different understandings of place: (i) Mapping the Tour, (ii) The transient place of finish lines, and (iii) Promoting connections: the Brittany-Plymouth Tour stage. The paper is designed to offer an indication of how interpretations might be made and thus provides only a partial insight on spatial conceptualisations. This is acknowledged further in the paper’s conclusion.

Threshold concepts

It is well established from pedagogical literature that “learning geographic concepts is an essential building block towards building a student’s deeper disciplinary awareness” (Klein et al., Citation2019, p. 213). Broadly, concepts are sets of ideas that help to define and progress understanding within a discipline. Learning about and engaging with concepts helps students transition towards thinking as geographers (Walkington et al. Citation2018). Fouberg (Citation2019), drawing on the grounding work of Meyer and Land (Citation2003), distinguishes between core and threshold concepts in geography. The former provide disciplinary-specific terminology or “building blocks” (Fouberg, Citation2019, p. 71) that help to progress understanding, while the latter go further, transforming how students see the world and rethink subject matter. By way of example, the concept of scale can help students understand differential processes taking place at local, national, or global levels. Understanding global–local relations helps to transform students’ perceptions to see that the local and global constitute each other (Massey & Jess, Citation1995).

To identify threshold concepts, scholars have used five traits set out by Meyer and Land (Citation2003): transformative, irreversible, integrative, counter-intuitive, and bounded (see Cousin, Citation2006; Fouberg, Citation2013). These traits also indicate why threshold concepts are so important to student learning: they transform a way of thinking or knowing the world, to the extent that once something is known it cannot be unknown (irreversible). Threshold concepts help to deepen understanding by revealing interrelated connections with other concepts (integrative), and are counter-intuitive because they challenge students’ preconceived understandings. Bounded, indicates that a threshold concept has marked edges, differentiating it from other (threshold) concepts. Space, place, and cultural landscapes have been identified as examples of geography’s threshold concepts (Fouberg, Citation2013; Klein et al., Citation2019), with Fouberg (Citation2019, p. 73) suggesting place as “perhaps the most bounded concept in geography”. These threshold concepts are central to the transition that generic undergraduates make to become undergraduate geographers, and thus deserve dedicated attention in the learning process.

To stimulate (threshold) concept-learning, geographers have emphasised the importance of issue-based enquiry. Through this inductive technique, students can be encouraged to personalise, explore, and apply concepts around a particular theme or inquiry, so that they become meaningful in tailored and memorable ways (see, for example, Klein, Citation2003; Spronken-Smith et al., Citation2008). Sport is a particularly powerful tool through which to achieve this. In addition to sport’s richness and ubiquity, many students relate to it at individual or societal levels, whether actively engaged in sport or not. From participation and spectatorship, to an abundance of media attention and public interest in sport, the topic is a central part of everyday life in many societies. These experiences provide opportunity for sport issue-based enquiries in which students can process information about the activity and discover concepts that transform their understanding. This is perhaps most evident through consideration of sports mega-events.

Sports mega-events

Mega-events have been characterised by Roche (Citation2000, p. 1) as “large-scale cultural … events, which have a dramatic character, mass popular appeal and international significance”. Building on this, Horne (Citation2017) emphasises the considerable social, ideological, political, and economic consequences that mega-events have for host cities, regions, and countries, as well as the significant extent of (often global) media attention they draw. Horne (Citation2017, p. 329) also recognises some of the consequences of mega-events for individuals: “the promise of a festival of sport, with emotional moments, shaping personal (life) time horizons.” Typical examples include the Olympic Games, Commonwealth Games, Pan-American Games, and FIFA Football World Cup. Elsewhere, I have argued that the Tour de France can be considered a sports mega-event (see Ferbrache, Citation2013). Most sport mega-events are hosted at regular intervals, though the host countries and cities change.

Due to the character of sports mega-events, they offer a rich issue base for concept-learning (see Digby, Citation2012, for example). Sports have generated a diverse range of resources that students can engage with, from academic materials (e.g. Gold & Gold, Citation2016; Wise & Kohe, Citation2020) to grey literature (e.g. Abraham, Citation2016; James, Citation1963; PyeongChang Organising Committee, Citation2018), including a variety of media forms (e.g. Aguiar, Citation2022; Alom, Citation2022; Extreme, Citation2022; FIFA, Citation2015). Such sources also reveal multiple perspectives among individuals or groups, and in terms of broader socio-cultural, political, economic, and environmental issues. This diversity increases the likelihood that students will be able to draw something of personal interest or experience from sport.

Moreover, sports mega-events often stimulate controversy and public debate (Horne, Citation2007, Citation2017), creating opportunities for student class debate, discussion, and critical reflection, beyond individual analysis. By way of example, Horne (Citation2007) demonstrates how host cities in the UK and Australia have sought to use sports events to stimulate social and economic regeneration. This raises questions concerning opportunity costs and benefits, as well as who can and should benefit. In other examples, sports mega-events have provided a platform for protest and controversial views of opinion around political issues such as the environment, workers’ rights, (trans)gender equality, bodies, and dress code (e.g. Horne, Citation2017; Jefferson-Buchanan, Citation2021; Polo, Citation2003). These sports-related issues are inherently controversial, as well as geographical, and provide stimulating material for students to debate and evaluate, to move beyond singular analysis of any event.

For this article, I draw on the Tour de France. In its current form, the Tour consists of 21 stages over roughly 23 days, during which cyclists race a route of roughly 3,500 km, mostly on French territory. Within this one race, there are multiple individual and team competitions, with the most notable being the general classification or “yellow jersey competition” in which the cyclist completing the course in the minimum amount of racing time is considered the victor. The remaining part of this article draws on the above pedagogical insights on concept learning to explore the threshold concept of place in a personalised way through sport-based enquiry. It comprises three vignettes on the Tour de France.Footnote1

Sport-based enquiry – a pedagogic example

For undergraduate teaching, this enquiry is designed to complement broader instruction, such as a lecture. It might then follow as a class/tutorial activity, or individual exercise with summative assessment. Preparatory reading is required by students, on the concept of place, as well as research into a sports mega-event that interests them. The aim of research is to find and select varied sources that reveal different ideas or information as a base for exploring and applying concepts of place. The aim is to interpret materials through a geographical lens. Furthermore, by sharing examples and analysis in class discussion, students can be encouraged to challenge their ways of thinking, (re)consider alternative readings, reflect critically, and thus move towards deeper learning. Importantly, this process (including feedback) ideally resists reducing place to only one or other approach.

The following trio of vignettes demonstrates how place might be applied to three different sources concerning the Tour de France. In this brief example, I have drawn from concepts expressed in an introductory chapter on place by Tim Cresswell (Citation2014). However, students are encouraged to read more widely and to engage with original sources that may be cited in such introductory texts. Like other sports mega-events, the Tour de France provides many ways for exploring the concept of place. A focal point is to personalise the entry points.

Vignette 1: Mapping the Tour

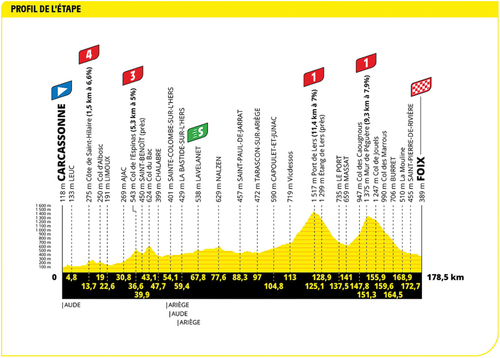

Engaging with sporting events as they happen can help to make geography appear more tangible and connected with real life. As I write, I am following live televised coverage of the Tour de France and marking the cyclists’ progress alongside a map and stage profile. As shown in , the stage profile depicts a start point in Carcassonne and, after climbing and descending through a series of named places (villages, towns, road junctions, mountain passes), its end in Foix.Footnote2 An accompanying itinerary () indicates the route in more specific terms relating to road numbers and more minor locations, as well as providing estimated times at which riders will pass these various points. Such objective depictions provide an example of “location” that Agnew (Citation1987) identifies as one of three key elements constituting place (alongside locale and sense of place). It is a powerful and widely recognised way of conveying place which, for example, enables Tour spectators to accurately know where (and when) they can view the cyclists on the road.

Figure 1. Profile of 2022 Tour de France Stage 16, from Carcassonne to Foix Source: Amaury Sport Organisation (A.S.O.) Citation2022

Table 1. Abbreviated version of Stage 16 route itinerary.

An alternative reading of could focus on place defined by mobility. The continuity of the yellow profile from Carcassonne to Foix connects and unites the aforementioned places. Most sports or sports events are (even temporarily) associated with distinct locations. However, unlike the typically fixed position of a football stadium, or athletic track, the Tour de France provides a useful example to consider the importance of mobility in constituting place. The Tour does not have a fixed place, rather its very meaning is based on movement from start to finish. It is not possible to locate the Tour in one particular city. Instead, the Tour suggests that place is much more about connections and flows, incorporating mobilities.

Cresswell (Citation2014, p. 14) indicates that “Mobility has often been portrayed as the other of place – as place’s enemy” yet rethinking this idea can mark a particular threshold moment for student geographers to see and understand the world differently: less defined by fixed and bounded places, and rather through places characterised by fluidity, flows, and connections. Other useful sporting activities that help to demonstrate this way of rethinking place constituted by mobility include marathons, certain sailing events, and the Torch relay preceding the opening of the Olympic Games. Advanced students might question how a seemingly fixed football stadium can also be understood as place defined by connections and flows.

Vignette 2: The transient place of finish lines

On occasion I have thought about the finish line of a race: it is such an important place to bike riders, it is the focal point of their existence. Their job means that as soon as they leave the start line they are in a desperate rush to get across that finish line. It becomes the most important place in the universe (Southam, Citation2011).

This extract is taken from a short online article written by former professional cyclist, Tom Southam. He evokes the finish line in a cycle race as a place that is fixed at a specific location and distance from the start line. It serves several functions, among them being able to objectively identify a winner. This fixity is important in other sports, for example, deciding whether a ball, puck, or foot is classified as either in or out of the place it ought to be. Southam also suggests the importance of meanings that become attached to place, giving the finish line further significance as “the most important place in the universe”. Geographers have used meaning to differentiate place from (more abstract) space (Tuan, Citation1977), where “Place is … a meaningful segment of space” (Cresswell, Citation2014, p. 4).

A further quote from Southam highlights how the finish line is given a distinct material presence:

Finish lines get tarted up in big bike races. They get a finish gantry; they get stands for the crowd, a podium, large TV screens and V.I.P. areas. But when a finish line is undressed, it is often exposed as just a piece of road… The soulless stretches of tarmac can look so strange on the three hundred and sixty something days of the year that they are not the centre of the cycling universe.

The finish gantry, stands, and TV screens highlight the importance of material presences defining place (see Cresswell, Citation2014, p. 9). They effectively turn a “soulless” or seemingly meaningless stretch of tarmacked road (space) into a meaningful place that defines the race in certain ways for the various competitors, spectators, and officials involved. Valuable links can be made with “sense of place” and the influential work of Yi-Fu Tuan (Citation1977).

A further theme for discussion, here, is the significance of temporal change in understanding place. Meanings of place change over time (for example, with/without a material presence; before and after the race has been won), challenging assumptions that meanings, or the places they relate to, are fixed and stable. Yet, students might like to consider which/whose meanings might endure longer than others, and why; potentially beginning to think about power and a politics of place.

Vignette 3: Promoting connections: the Brittany-Plymouth Tour stage

Stage 2 of the 1974 Tour de France was hosted in Plymouth on the UK’s south coast (). The Tour arrived from the northwest region of Brittany, in part via the newly established Brittany Ferries service connecting Roscoff and Plymouth.Footnote3 With it, came thousands of Breton artichokes, which were distributed freely to roadside spectators before the race itself: a symbol of Brittany’s agricultural heritage and the products available within the enlarged EEC market (Reed, Citation2015).Footnote4

The Plymouth stage was incorporated in a “Breton Week of the Tour”, designed to focus the world’s media attention on Brittany. This may seem a contradiction for most readers, as if Plymouth is “out of place” among a set of Breton stages. The idea of what Brittany is, if Plymouth is incorporated, seems to exceed the familiar geography of the French region. Critical questions can be posed around this apparent contradiction: what assumptions are being made to define Plymouth “out of place”? How might place be rethought for this geography to make more sense?

The difficulty of incorporating Plymouth into a geography of Brittany is shaped by an understanding of place as bounded, closed, and insular. Such conceptualisation marks places as discrete and separate from others. By contrast, a geography incorporating Plymouth within the “Breton Week”, focuses on Brittany defined by openness and connections with elsewhere. Indeed, a vision of Brittany was deliberately constructed in the mid-1970s to emphasise the region’s connections outwards, a significant component of which was the Brittany Ferries transport link. This vision was created with the aim of regenerating the region’s economy, and the Tour, with its rich media following, was used to promote this sense of place:

Local organizers tried to fashion the “Breton Week of the Tour” into an international television event that would shower media attention on the commercial and agricultural resources of Brest and western Brittany and showcase the region’s links to England and international markets. (Reed, Citation2015, p. 122)

Doreen Massey’s (Citation1994) “global sense of place” captures such emphasis on openness and linkages (interrelations) with other places. Cresswell (Citation2014) includes other terms to express similar characteristics, such as horizontality, and relationality. These spatial conceptualisations enable students to challenge often taken-for-granted ideas of place as bounded, discrete, and insular, to rethink place as more connected, contingent, and open. This is an important threshold for geography students to encounter.

Advanced students could further consider the question of politics (see Massey, Citation1994, Citation2005). What sort of politics is imagined through Brittany’s connectivity with Plymouth, and more widely to the UK? As one example, it is no coincidence that this cross-Channel Tour stage occurred in 1974, after accession of the UK and Ireland to the EEC. Their membership altered the geostrategic position of Brittany, from the EEC’s northwestern fringes to a more central (in north–south terms) position within an enlarged peripheral maritime region. Recognition of connections promoted internationally during the Tour (e.g. the maritime transport link, artichokes, French broadcasters in Plymouth), can help to bring into the imagination a fuller awareness of the possibility of more connected futures (politically, economically, socially etc.), illustrating, as Massey (Citation2005) argues, a relational politics of place.

Conclusion

This paper has brought together literature on concept-learning, sports mega-events, conceptualisation of place, as well as a range of sources relating to the Tour de France, to demonstrate how sports geography can help geography students explore, personalise, and apply the threshold concept of place. The three vignettes drew on varied sources, helping to illustrate how place can be applied to everyday or banal situations and materials of personal and research interest. The result is to understand the Tour de France, an annual cycling race, as something geographical and inherently spatial, to actively engage with learning “place”, and stimulate rethinking of the world in different ways.

Examples and interpretations, in this article, provide only partial insights on spatial conceptualisations, in relation to sports mega-events. The vignettes are designed to offer an indication of how interpretations might be made, rather than exhaust or prioritise certain readings or concepts. Key to this exercise is encouraging students to understand how different concepts may be applied to the same examples, and each with different consequences that may be evaluated for critical thinking. For instance, what is the effect of understanding the cities the Tour passes through as objective locations, alongside seeing them as deliberately constructed senses of place? To what extent are the two exclusive? This exercise also advances geographical engagement with the concept of place and how it might be studied. One of the reasons that the author focused on Cresswell (Citation2014), is his encouragement for geographers to develop a “renewed practice of place writing” based on “detailed and patient interweavings of theory and empirics in order to better understand the ongoing process of becoming places.” (p.20). Places, as with sports events, are never fixed or complete, but always evolving. Asking students to recognise this is crucial in shaping their thinking as a geographer.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Some examples of academic introduction to the Tour de France include Palmer (Citation1998, Citation2010), Ferbrache (Citation2013) and Reed (Citation2015). The Tour de France website also provides a useful practical introduction accessible in several languages: www.letour.fr

2. A detailed map of this stage route is available at https://www.letour.fr/en/stage-16

3. Brittany Ferries was established in 1973 by a group of French Breton farmers, to transport their produce to the UK markets.

4. The UK joined the European Economic Community in 1973, of which France was already a member.

References

- Abraham, R. (2016). Tour de France legendary climbs. Carlton Books.

- Agnew, J. A. (1987). Place and Politics: The Geographical Mediation of State and Society. Boston, MA: Allen & Unwin.

- Aguiar, A. (2022). Signs of the Tour: The story behind the simple arrows that point the way to victory in cycling’s most prestigious race. The New York Times. 22 July. Available via: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/22/sports/cycling/tour-de-france-cycling-photos.html?smid=tw-nytsports&smtyp=cur. Retrieved July 23, 2022

- Alom, Q. (2022). Sustainable sport for the Future. Costing the Earth. BBC Radio 4, 18 may 21: 00. Available via: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0017chj Retrieved July 23, 2022

- Amaury Sport Organisation. (2022). A.S.O. Media Content. Available via: https://mediacontent.aso.fr/mediacontent/identification Retrieved July 24, 2022

- Bale, J. (2003). Sports geography. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203478677

- Cousin, G. (2006). An introduction to threshold concepts. Planet 17, 4–5. Available at: https://www.ee.ucl.ac.uk/~mflanaga/Cousin%20Planet%2017.pdf.

- Cresswell, T. (2014). Place. In R. Lee, N. Castree, R. Kitchin, V. Lawson, A. Paasi, C. Philo, S. Radcliffe, M. S. Roberts, & C. W. J. Withers (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Human Geography (pp. 3–21). Sage.

- Digby, R. (2012). London’s 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Making the most of a learning opportunity. Teaching Geography, 37(1), 6–9 https://www.jstor.org/stable/23755236.

- Extreme, E. (2022). Electric Odyssey S02E07: Senegal legacy special. Available via: https://youtu.be/fsfBL_uBiCc Retrieved July 24, 2022

- Ferbrache, F. (2013). Le Tour de France: A cultural geography of a mega-event. Geography, 98(3), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2013.12094380

- FIFA. (2015). The Story of the 2015 FIFA women’s world Cup. Available via: https://www.fifa.com/fifaplus/en/watch/movie/RlE9BOTchoOvpOorS1ih2. Retrieved July 23, 2022

- Fouberg, E. H. (2013). The world is no longer flat to me: Student perceptions of threshold concepts in world regional geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 3(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2012.654467

- Fouberg, E. H. (2019). Finding your way in liminal space: Threshold concepts and curriculum design in geography. In H. Walkington, J. Hill, & S. Dyer (Eds.), Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Geography (pp. 71–86). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Gold, J., & Gold, M. M. (Eds). (2016). Olympic cities: City agendas, planning, and the world’s Games, 1896-2020 (Third ed.). Routledge.

- Horne, J. (2007). The Four ‘Knowns’ of sports mega‐events. Leisure Studies, 26(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360500504628

- Horne, J. (2017). Sports mega-events – three sites of contemporary political contestation. Sport in Society, 20(3), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1088721

- James, C. L. R. (1963). Beyond a Boundary. Stanley Paul & Co.

- Jefferson-Buchanan, R. (2021). Uniform discontent: How women athletes are taking control of their sporting outfits. The Conversation. 25 July. Available via: https://theconversation.com/uniform-discontent-how-women-athletes-are-taking-control-of-their-sporting-outfits-164946. Retrieved July 23, 2022

- Klein, P. (2003). Active learning strategies and assessment in world geography classes. Journal of Geography, 102(4), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340308978539

- Klein, P., Barton, K., Salo, J., Lee, J., & Vowles, T. (2019). Conveying geographic concepts through issues-based inquiry. In H. Walkington, J. Hill, & S. Dyer (Eds.), Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Geography (pp. 211–226). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Massey, D. (1994). Space, place and Gender. University of Minnesota Press.

- Massey, D. (2005). For space. Sage.

- Massey, D., & Jess, P. (1995). Places and cultures in an uneven world. In D. Massey & P. Jess (Eds.), A Place in the World? Places, cultures and globalization (pp. 215–239). The Open University.

- Meyer, J., & Land, R. (2003). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: Linkages to ways of thinking and practicing within disciplines. Enhancing teaching-learning environments in undergraduate courses ( Occasional Report 4). ETL Project, University of Edinburgh.

- Palmer, C. (1998). Le Tour du Monde: Towards an anthropology of the global mega-event. The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 9(3), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-9310.1998.tb00196.x

- Palmer, C. (2010). ‘We close towns for a living’: Spatial transformation and the Tour de France. Social and Cultural Geography, 11(8), 865–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2010.523841

- Polo, J. F. (2003). A côté du Tour: Ambushing the Tour for political and social causes. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 20(2), 246–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360412331305713

- PyeongChang Organising Committee. (2018). Official Report of the PyeongChang 2018 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. Avalable via: https://library.olympics.com/default/official-reports.aspx?_lg=en-GB. Retrieved July 23, 2022

- Reed, E. (2015). Selling the yellow Jersey: The Tour de France in the global Era. Chicago University Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226206677.001.0001

- Roche, M. (2000). Megaevents and Modernity: Olympics and Expos in the growth of global culture. Routledge.

- Southam, T. (2011). The strangeness of finish lines. no place.

- Spronken-Smith, R., Bullard, J., Ray, W., Roberts, C., & Keiffer, A. (2008). Where might sand dunes be on Mars? Engaging students through inquiry-based learning in geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 32(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260701731520

- Tuan, Y.-F. (1977). Space and place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press.

- Walkington, H., Dyer, S., Solem, M., Haigh, M., & Waddington, S. (2018). A capabilities approach to higher education: geocapacities and implications for geography curricula. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 42(1), 7–24.

- Wise, N., & Kohe, G. Z. (2020). Sports geography: New approaches, perspectives and directions. Sport in Society, 23(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1555209