ABSTRACT

Independence is a concept of scholarly interest in relation to higher education, especially when it comes to undergraduate projects. At the same time independence is characterised by a certain conceptual ambiguity, and, consequently, tends to be understood differently in different academic contexts, both nationally, internationally and interdisciplinary. Based on the existing research in the field, we see a need for more studies on how supervisors of undergraduate projects handle this conceptual ambiguity. The aim of this article is, thus, to examine how supervisors from two different education programmes, teacher education and journalism, in two different countries, Sweden and Russia, understand the concept of independence within higher education in connection with the supervision of undergraduate projects. The analysis is based on 12 focus-group interviews with supervisors at different universities in the two countries. In our results, we highlight and discuss seven different understandings of independence that were recurrent in our material and in which phases of the undergraduate project they were seen as most significant. Using Wittgenstein’s ideas on family resemblances, we conclude with a discussion of how the concept independence may be understood in relation to some associated concepts that are also significant within higher education.

Introduction

One of the aims of the Bologna cooperation on higher education, which a large number of European countries are members of, was to reform higher education in order to achieve more comparability in and between different European education systems. The ambition was, among other things, to promote mobility in and between countries (cf. European Ministers in charge of Higher Education Citation1999, 385). But not all aspects of higher education are very easy to make comparable between universities. Many concepts that are highly significant when it comes to student learning processes, didactic choices and educational ideals within higher education, have a tendency to be rather vague and implicit, without clear and unambiguous definitions. This is true of, for instance, learner autonomy, critical thinking or criticality, but also student independence and independent learning (Borg and Al-Busaidi Citation2012; Gardner Citation2007; Moore Citation2011).

As is clear from the well-established research field on independent learning, independence is a concept that has gained scholarly attention in relation not only to the school context, but also in relation to higher education (Broad Citation2006; Cukurova, Bennett, and Abrahams Citation2017; Lau Citation2017; Meyer Citation2010; Meyer et al. Citation2008; Jones, Joan, and Brian Citation1999). It is, in addition, a recurring topic in research that is more specifically geared towards supervision, where independence may be made relevant as a key concept (Gardner Citation2007), as a goal (Gurr Citation2010) or as an important tension when it comes to supervision (Lee Citation2008). Independence is also emphasised in various steering documents connected to higher education, as, for example, in the Swedish Higher Education Ordinance, where it is described as one of the main goals of higher education (cf Swedish Council for Higher Education Citation2017).

The ideal of and expectance of student independence is, in general, most pronounced in relation to the undergraduate project,Footnote1 something that is evident in that it is frequently mentioned in curricula and course plans for courses surrounding the undergraduate project (cf Magnusson Citation2015). That the undergraduate project has a particular relevance when it comes to independence is due partly to its predominance as a means of assessing student performance, partly due to the fact that it generally comes towards the end of the education and that the character of the work the students are expected to do and the organisation of the courses usually makes independence especially possible for, as well as expected of, the students. At the same time as independence is given a lot of significance in relation to the undergraduate project, the concept is also in this context understood in different ways in different academic environments and settings, both nationally, internationally and interdisciplinary (cf Meyer et al. Citation2008).

Independence is, furthermore, sometimes linked to a set of values that is often described as typical for or more prominent in Western and more specifically North-western countries. In quantitative studies of values and attitudes Sweden, for instance, tends to be ranked high when it comes to positive attitudes towards values of individuality, self-expression and also independence. In contrast, a country like Russia is regularly associated with an Eastern culture, where aspects such as authority, collectivity and/or restraint appear to be more highly valued (Inglehart and Welzel Citation2015; Pavlenko and Blackledge Citation2004). Such aspects make it particularly valuable to study what the understandings of independence may look like not only among supervisors from different education programmes within one particular country, but also from countries that may be dominated by different sets of values, but still are part of the Bologna cooperation and its ambition to increase comparability between education systems.

The overarching aim of this article is, accordingly, to examine understandings of independence in higher education, and more specifically to examine how supervisors from two different education programmes, teacher education and journalism, in two countries, Sweden and Russia, understand the concept independence in connection with the supervision of undergraduate projects. The intention of including two countries is, however, not to compare whether the broad descriptions of values and attitudes in the two countries are true or false, but rather to gain a more nuanced comprehension of the complexities and variations concerning the concept of independence.

Survey of the field

Since the aim of the article is to examine and discuss the concept of independence, within the context of undergraduate supervision, we mainly position this study in relation to research concerning related academic concepts such as independent learning, learner autonomy and critical thinking (Atkinson Citation1997; Lipman Citation1987; Davies Citation2011). As was discussed above, many such concepts tend to be rather vague and implicit, without clear and unambiguous definitions, even though they may be very central within the academic context. In some studies, this conceptual ambiguity is explicitly addressed. Both Gardner (Citation2007), Borg and Al-Busaidi (Citation2012) and Moore (Citation2011) investigate different perceptions of these academic concepts, Gardner in student groups, Borg and Al-Busaidi in questionnaires and interviews with English language teachers and Moore in interviews with and texts by practicing academics in three different fields. One aspect that is highlighted in research concerning these concepts is how in different ways they tend to be influenced by and connected to implicit values and norms in academic writing (cf Benson Citation2009; Moore Citation2011; Borg and Al-Busaidi Citation2012).

The concept that is most relevant in relation to our study is, naturally, independent learning. Since this concept has been discussed both in relation to the school context and in relation to higher education, it constitutes a rather extensive field of research (e.g. Broad Citation2006; Cukurova, Bennett, and Abrahams Citation2017; Jones, Joan, and Brian Citation1999; Knight Citation1996; Lau Citation2017; O’Doherty Citation2006). Within this field, independent learning has been defined and described in a number of different ways, in relation to everything from different modes of learning to the provision of materials and resources (cf. Souto and Turner Citation2000, 385) or even as synonymous to distance learning (Moore Citation1973). Since this article focuses on student independence in higher education, not all these perspectives are relevant here. But even though there are obvious differences between the school context and higher education, we do find certain aspects of the discussions of independent learning in school to be also relevant for our study, as for instance in Meyer’s (Citation2010) literature review of research on independent learning in a British context, where he presents and discusses different definitions of independent learning.

It is particularly the discussions of the role of the supervisors, or tutors in schools, when it comes to enabling independent learning among pupils or students, that we find to be of relevance to our study. According to, for example, Meyer et al. (Citation2008) there is a broad consensus within British research on the field that independent learning does not merely involve pupils working alone, and that teachers or supervisors have an important role in enabling and supporting learning. Other scholars have argued similarly that independence is not something that ‘just happens’, but rather that learners need to be ‘enabled to make the best use of independence’ (OECD Citation2017; van Grinsven and Tillema Citation2006, 2). The emphasis on the important role of the supervisor or tutor when it comes to enabling independent learning in the research in the field is one main reason for our choice to focus on supervisors. Even though the research field around independent learning is quite extensive and multi-faceted, it mainly comprises theoretical discussions and descriptions of various kinds, while there is a distinct lack of studies that examine teachers’ and supervisors’ conceptions of independence and, not least, empirical examples of the variations in understandings of the concept. Our study thus fills a gap in this respect.

When discussing different understandings of student independence in this article, we will use Wittgenstein’s (Citation1958) idea of family resemblances as one of our starting points. Wittgenstein saw concepts as related to one another in many different and complex ways, as overlapping or partly synonymous or sometimes as hyponymous. We look at the concept of independence in a similar way, in the sense that we are not trying to detect one specific definition but are, rather, aiming to find different understandings and variations and discuss how they are related to one another and other, similar, concepts.

Material and methods

In this article focus-group discussions will be the object of analysis, as this type of empirical material is highly appropriate for examining how supervisors in different academic contexts understand and relate to the concept of independence, both when it comes to the existing variations and when it comes to similarities and consensus between representatives from the different contexts (cf Krzyzanowskii Citation2008, 162; Morgan and Krueger Citation1993). In total, the focus-group material consists of 12 one-hour focus-group discussions. Each focus group included four-to-six supervisors, both men and women; we conducted seven focus-group discussions within teacher education at different universities in Sweden and Russia, and five focus-group discussions within journalism education in Sweden and Russia, also from different universities.Footnote2

In both Sweden and Russia, we were assisted by a local contact person, who helped us with finding relevant supervisors and with the practical arrangements. The focus groups were then conducted by one of the project researchers, in Russian or Swedish. We used the same question guide in all of the focus groups as a starting point and foundation for the discussions. The question guide included more open questions, such as the informants’ own conceptions when it came to independence in relation to undergraduate projects, and more specific questions, such as how important they regarded independence in supervision to be and if they discussed independence with students or colleagues. The discussions were recorded and transcribed and the ones conducted in Russian were translated to English.Footnote3 The participants were given information about the study and what their participation would involve and each gave their explicit consent to partake. Where needed, the university also gave its ethical approval. All the material has been anonymised.

For the analysis of the material for this article, the two cooperating researchers separately read and systematically coded the informants’ different descriptions of how they understood independence. In the next phase of the analysis, the researchers jointly sorted the coded examples into a number of basic themes or categories that emerged from the reading of the material, such as ‘independence as critical thinking’. All in all we identified seven such major recurring themes in the focus-group material. The method of analysis used could thus be described as following the principles of content analysis (cf Schreier Citation2012; Krzyzanowskii Citation2008, 169).Footnote4 In the text below the given examples have been labelled according to country (SW, RU), education programme (TE, JE) and university in each country (U1, U2), and, where more than one focus group was conducted in the same university, also according to that (1, 2).

Results and findings

In the following we will present the main results from the analysis of the material. We will describe the seven major categories that we discerned in our analysis of the participating supervisors’ different understandings of independence, giving examples of the kind of formulations that were typical of each category. Even though we have here chosen to present the results in the form of different themes, we want to underline that there were variations in the material that are not always easy to capture in this kind of overview. We will return to that in the discussion.

Another aspect worth highlighting is that the discussions, quite naturally, were affected by the particular kind of conversational context a focus group comprises (cf Krzyzanowskii Citation2008). The supervisors did, for instance, often agree with, and elaborate on, what their colleagues had said during the discussion. But they could also disagree with each other, as is obvious in the following example:

Well, I agree with [x] that independence in our situation manifests itself mainly in the choice of a topic. But I don’t agree that it determines all the rest. (JERUU11)

The disagreement they expressed did, however, tend to be more about to which degree or in what way they found a particular aspect to be important or significant in relation to independence in undergraduate supervision, rather than a disagreement on if a certain aspect was relevant at all.

Some of the themes presented below were discussed in more or less all the focus-group interviews, while others were only discussed in some of them. This should also be seen in relation to the focus-group situation, where the participants partly influenced which directions the conversations would take, even though we had a common question guide, and where time frames also set limits for the number of topics and themes that could be covered.Footnote5

Taking initiatives

One of the most central understandings of independence that became visible in the focus-group material, in both countries and in both education programmes, involved the conception of students taking initiatives and making suggestions. This view of independence was in the discussions tightly linked to supervision interaction, and the examples given included students coming up with ideas for the topic of the undergraduate project by themselves as well as students being prepared when coming to a supervision meeting – prepared with for instance ideas concerning which methods or theories to use or which literature to read:

He had an idea when he came to the first meeting, an idea he had come up with himself, what he wanted to do. That is, he had independently formulated the idea of what he wanted to research and he also had suggestions regarding what books he could use, which he wanted to check with me. The whole supervision was characterised by that. He came to every meeting prepared with some step he had taken, a step ahead of me so to speak, and he only wanted to have it confirmed: ‘Is this O.K?’, ‘What do you think?’ and so on, and I felt that this was a wonderful example of independence, how he worked. (TESWU11)

The perceived connection between independence and the students taking initiatives could also include the students’ attitudes and actions during the supervision itself. Another supervisor explained how she wanted students to initiate the discussions during the supervision meetings. She found this to be a sign of independence since this also meant that they reflected on the ideas they had (JERUU21).

As the above and other examples from the material show, the students’ initiatives in terms of preparations and suggestions were regarded as important and desired aspects of independence and as something the supervisors would expect of an independent student. The supervision meetings, then, became an arena where such independence would become visible to the supervisor, but also an arena where the supervisors would encourage or discourage the ideas and initiatives presented by the students. Hence, this understanding of independence included the idea that the students should take initiatives, but also the idea that the role of the supervisor was to confirm if the ideas and thoughts the students had and presented were something to go through with or not. It was, as is evident in the quotation above, a question of the students initiating discussions, not necessarily making all the decisions.

2. Positioning oneself in relation to sources and context

Another understanding of independence that was frequently expressed in the focus-group discussions, in both countries, concerned the relation to sources and context. Independence in this respect could, according to the material, include the ability of the student to successfully position the study, or specific parts of the study, in relation to scientific sources, theoretical concepts or research traditions. One basic aspect of this was to be able to properly position one’s own study in relation to the work of others:

Independence for me means the ability to assess the results of other people’s work independently and see the difference between work done by yourself and the work of others. (TERUU21)

This understanding of student independence was thus connected to the requirement of students to follow standard research ethical procedures concerning quotations and references, as well as to the idea that independence in its most fundamental understanding comprised doing the work yourself and not plagiarising or copying from others. Emphasising this aspect of independence was particularly common in the Russian focus-group discussions. If this was independence at a basic level, then truly succeeding in positioning oneself and one’s work in relation to something else was thought to be a more advanced kind of independence:

I like it if someone for example has some research or a theory or something that you position yourself independently to. … I find that when they really position themselves independently in relation to something, when they have something to position themselves against, that is very independent on an advanced level. We can rarely expect that in these undergraduate projects when it’s like: ‘Help! I’m going to write my first thesis, what should the title page look like?!’ Then we can’t really expect that. Maybe then we should just be happy if they write the text themselves and don’t copy from someone else. (TESWU11)

In addition to being able to show independence in relation to other people’s work and research results, the students were in this understanding of independence expected to be able to relate to the specific academic context they were a part of. In the discussions around this it became clear that the supervisors did not view independence as something limitless that granted the students total freedom. On the contrary, they emphasised the need for setting boundaries and that the desired independence should be developed within these. The rules and boundaries mentioned by the supervisors in the focus groups were both tied to academic norms within a certain context, such as mastering the right or preferred methodology, a certain style of academic writing, genre- and language-recommendations and so on (JERUU11), and to more concrete and explicit limitations for the students, such as templates for how the undergraduate project should be structured, timeframes, the maximum number of pages in the finished text and so on (e.g. TESWU12, TESWU11, TESWU11, TESWU12, JERUU12, JERUU11, TESWU12).

Being able to relate to the academic context in this way was, however, not only seen as a question of following the rules, but also of understanding the rules and boundaries, and thus knowing when, where and why to follow them. Consequently, this aspect of student independence also concerned the students’ relationship to the supervisors. In the focus-group interviews it became clear that independence in this sense included listening to feedback and advice given by the supervisor, but at the same time having the ability to use this in an independent way, in other words not necessarily following such recommendations blindly but, rather, using them for making further, independent, improvements of the work or the text. The ability to position oneself and one’s study in relation to sources and context could thus be displayed both in the text itself and during the supervision meetings.

3. Originality, creativity and enthusiasm

Another way to understand independence that appeared in several of the focus groups in both countries, was tightly linked to ideas around originality and creativity. This could include inventing something of one’s own and making an actual, albeit small, contribution to the research field:

I am, somewhat, of the mind that [independence] is about creativity in a weaker sense of the word. That is, the students should be active and really create what they do in this paper. They should be active in formulating issues that no one has formulated for them and that is a creative process which is connected to that they are supposed to make choices, make decisions during the course of the process. That is also what they have to defend during the examination. (TESWU12)

This understanding of independence could also include aspects such as engagement and enthusiasm, showing an interest or managing to give the text life (JERUU22, TERUU22). One common view was that if students were truly interested in their topic, they tended to become more independent in relation to the supervisor, but often also managed to make a more original and creative contribution. Creativity, originality and enthusiasm or interest thus tended to be viewed as interconnected and were primarily described as displayed in the preparation of the project and during the supervision meetings.Footnote6 In the focus-group discussions, the need for boundaries was mentioned also in relation to this aspect of independence:

But it is interesting, this thing with freedom in relation to boundaries. Since putting up boundaries doesn’t necessarily mean less independence. On the contrary, that might actually trigger creativity …. Because, having completely loose reins doesn’t give maximum independence in that way. (JESWU11)

The boundaries put up by the supervisor, or within a particular academic context or disciplinary setting, could thus be seen not only as something the students should be able to relate to, reflect upon and, to the right extent, follow, as was discussed previously, but also as something that could actually enable creativity and thus increase the level of independence among the students. The relationship between rules and boundaries, on the one hand, and student independence, on the other, was in other words rather complicated and multi-layered in the sense that it could be seen to both restrict student independence and in a certain sense increase it.

4. Motivating, arguing and choosing

Yet another main understanding of independence that was distinguishable in the focus-group material, in both countries and both education programmes was that it should include the students’ ability to motivate and argue for the choices they made in the process of writing the undergraduate project. This understanding of independence could thus be seen as related to the above category of positioning oneself, but here the main focus was the choices the students have to make throughout the work with their undergraduate projects. These choices existed on various levels and one of the aspects that was described as most basic and important, not least in the Russian focus groups, was choosing the topic and subject of the study:

… the topic needs to be chosen independently and then developed as thoroughly as possible. This is what, in my opinion, determines all the rest. … Independent choice of the topic that a person is willing to work on is for me the characteristic of independence. (JERUU11)

The choices mentioned in the focus-group interviews also included, for instance, selecting relevant methods for gathering and analysing the empirical material, and choosing theories and theoretical concepts (JERUU11, TESWU11, JESWU11, etc.). Several participants in the Russian focus groups also emphasised the significance of choosing the supervisor – something that their students were generally expected to do. This was a choice that was in its turn tightly linked to the choice of topic for the project, since different supervisors had academic competence in different fields (JERUU11).

Some of the interviewed supervisors described that this aspect of independence – to make all the necessary choices – could be quite difficult and even stressful for the students. One way to handle that, and thus avoid the work with the undergraduate project getting stranded along the way, was to give the students a limited number of alternatives to choose from (JERUU11, TESWU12, TESWU12, JERUU11, TESWU12). This could thus be regarded as related to the view mentioned above, that giving the students boundaries could actually increase their independence.

In addition to being able to make these necessary choices, the students were expected to be able to explain why they had made that particular choice (JESWU11, JERUU12). The ability to argue for the choices they had made, could be useful both during supervision meetings, since the supervisor might not always agree with the choices, in the finished text itself, and during the defence of the undergraduate project (TESWU11). It was even seen as important for the students to be able to motivate their choices when it was, in fact, the supervisor who had suggested doing things in a certain way (TESWU11). This can be seen as related to how managing to clearly motivate one’s choices and decisions was regarded as a good way of displaying independence and as one way in which the interviewed supervisors saw it as possible to actually assess and grade the level of independence among the students.

Not only motivating and arguing for one’s choices, but also making a case and taking a stand in the text, could be viewed as a sign of independence:

It [independence] is actually to make a point in your work, to really make a case for something. To make a clear contribution: that you manage to write your thesis in relation to previous research, to theories. That is, you make an argument supported by your material … the whole paper and the whole work becomes some sort of argument where you push something …this big independence. (TESWU11)

In this sense, the desired or expected student independence thus involved the ability to argue both for what you are doing (TESWU11, TESWU12) and for what you are proposing/stating (TESWU11). This latter kind of argument was, however, not always seen as something positive and desirable. Participants in one of the Swedish focus-group interviews with supervisors from journalism education, for instance, claimed that it could become quite problematic when students mistook arguing for voicing one’s own personal opinions (JESWU11). To argue a case could, in other words, be regarded as negative if the argument was not founded in anything specific, such as the analysis of the material or theoretical perspectives, but just related the personal views of the writer.

5. Critical thinking and reflection

That independence includes aspects of critical thinking, was also a view that was frequently expressed in the focus-group interviews, in both countries and both education programmes. Criticality, or being able to reflect critically, was described as a rather specific competence, where an independent student should be able to, for instance, read scientific research with ‘critical eyes’ gained from their own experience and work, but also manage to make critical reflections on their own work as well as the work of others (JERUU21, TESWU12, TESWU12, TESWU12). Criticality could thus be viewed as an approach that was present in the reading process or the process of gathering or analysing empirical material, and also as something that could be displayed in the finished text.

In certain ways, this understanding of independence resembles the understanding of independence as being able to position oneself in relation to scientific sources and motivating one’s choices. But in the focus-group interviews it became clear that it also involved something additional, as is evident in the following quote:

Sometimes the first parts look like they were written using a single template: this author says this, that author wrote that, we conclude that all authors did a great job. But when a person is really working hard on a topic, they don’t just write about various perspectives and concepts they find in other books. They agree with some of them and argue with others. They demonstrate their critical thinking. … I see that a person really reflected on this theoretical issue while studying it. That a person didn’t just read books and copy-paste some bits and pieces of theoretical conclusions from them to his paper. This is a manifestation of independence as a skill for critical thinking and perception, attempts to analyse, express one’s own opinion and even argue with renowned authors. (TERUU22)

As the quote exemplifies, the students were in this understanding of independence not only expected to position themselves and their work in relation to previous research and theoretical perspectives, but to take it one step further and actually disagree or argue with other scholars. They should, in other words, approach what others had done with a critical mind, even though these other scholars could be seen as authorities in relation to an undergraduate level project. A similar distinction between using sources and perspectives independently and actually critically reflect on them, is evident in the next example:

I usually talk about broadness. That if you are independent you manage to be both broad and narrow. In other words – if you get the assignment to compare several perspectives, then you shouldn’t use only one source. You should be able to compare several of them. But you should also be able to be critical in relation to this. “Do I think this is correct? Does this theory coincide with my experience?” (JESWU11)

Independence was thus related to criticality on two different levels. On one level, it could consist of activities that the process of writing the undergraduate project could or should involve, such as arguing, analysing, expressing personal opinions, problem solving and so on. On another level, it was related to the approach the students had to such activities – that they should approach everything from reading to gathering material and using theoretical perspectives with a ‘critical eye’. This kind of criticality was, however, seen as part of a more advanced level of independence that could not necessarily be expected by all students, much like the ability to truly position oneself and one’s work in relation to other sources and contexts.

6. Taking responsibility

Yet another specification in the understandings of independence as related to making choices and positioning oneself in relation to sources, literature and theories was that it should involve students taking responsibility. The expected or desired responsibility could concern the practical aspects of the undergraduate project, such as meeting deadlines and following the recommended format for the layout of the essay or the reference system (JESWU11). But the connection between responsibility and independence could also concern more overarching aspects, such as that the students should be aware that they were the ones responsible for the choices they made, as well as for the quality, creativity and originality of the project (TESWU12, TESWU12). It was, in other words, the students who were expected to take responsibility for the project as a whole, even though the supervisors would be there to help them and guide them along the way:

To me independence of a student is primarily related to responsibility. … For me it is important that the students walk this way on their own, because this is the only way they can learn to take responsibility for what they have done, for the conclusions they have come to, the final project they have come up with and which they like. To get through to some final stage that they themselves would be satisfied with (JERUU12)

That taking responsibility might be necessary in order to give the students the satisfaction of feeling that they had succeeded primarily by themselves is one aspect of this, as the quote above indicates. But, according to our material, it could also be a question of what the supervisors did not want to take responsibility for (JERUU21). As for instance, the quality of the final product:

I tell my students … right from the beginning that the responsibility for the quality of what they write in general and the originality of the text in terms of copyright compliance in particular, is completely on them. If they write a bad paper, I won’t give them the highest grade. And that’s their responsibility for independent work. The primary responsibility. (JE RUU11)

That the supervisors in the focus-group interviews emphasised the need for students to take responsibility for the conclusions and the quality of the final product, could be seen as connected to the expected, and mostly regulated, division between, on the one hand, supervising and, on the other hand, examining or grading the undergraduate projects. The supervisors could, in other words, generally not guarantee or promise that a student would pass the exam or receive a particular grade, regardless of what kind of feedback they had given them during the supervision. Even though the relationship between the supervisor and the examiner and the regulations for examination of the undergraduate projects differed both between universities in the two countries and between universities in the same country, this was a theme that was discussed in several of the focus groups.

7. Generalising and synthetising

In the last understanding of independence, that we want to highlight here, it was the students’ ability to generalise or synthetise that was in focus. The ability to generalise or synthetise was mentioned in focus groups in both Russia and Sweden, but it was not one of the most common themes. This aspect of independence was primarily thought to appear in the written text, for instance in the conclusions made by the author, or as in the following quote, in the discussion:

One place where I think that it often becomes visible how independent they are, is when they are supposed to tie the whole work together in the discussion. … when they tie all of these parts together, then I think it usually shows how independent they are. (TESWU21)

The ability to generalise is in this particular context not primarily a question of making a statistically sound study, since most of the students in journalism and teacher education at the universities where the focus-group interviews were conducted tended to use qualitative methods and quite limited materials. To be able to generalise was, rather, seen as an ability to contextualise their own study, through relating it to a larger societal or academic context (TESWU11). In that sense, this last understanding of independence was also connected to the above-mentioned ability to position oneself and one’s study in relation to different contexts. But here the focus was on that the results and conclusions should be discussed in relation to a bigger picture, whether this concerned, for instance, education or media politics, or media debates around school or journalism.

Discussion

As the above analysis of the focus-group material shows, there was a great variation in how student independence was understood and explained by the participating supervisors. In view of the ambition of the Bologna declaration, to try to create greater comparability between universities in different European countries, such variations could, obviously, be regarded as problematic (cf. European Ministers in charge of Higher Education Citation1999, 385). On the other hand, the variations we found could not in any obvious way be related to specific universities, countries or education programmes. There were differences in how independence in relation to writing the undergraduate project was described and understood in focus groups from universities in the same country or from the same education programme, but also similarities between how it was described and understood in focus groups from universities in different countries or from the different education programmes. Considering the differences in values and attitudes that value surveys have shown generally exist between Russia and Sweden, we had in fact initially expected the variations to be more clearly related to country than was actually the case according to the analysis of our material (cf Inglehart and Welzel Citation2015; Pavlenko and Blackledge Citation2004).

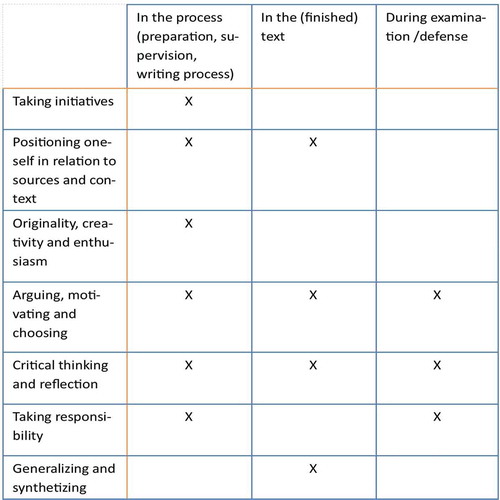

Furthermore, even though student independence generally appeared as a rather vague, complex and not readily defined concept in all of the focus-group interviews, it still tended to be discussed and problematised in quite similar ways, regardless of in which country or university the focus-group discussion took place. There were, in other words, certain common tendencies in the material as a whole when it came to how student independence was defined and discussed, as has also been shown in the examples above. The Table in summarises the different themes or aspects that were evident in our material and in which phases of the work with the undergraduate project these could be expected to be displayed by the students, according to the focus-group interviews. To develop the analysis, we will in the following use the Table in as a starting point for a further discussion of some aspects of student independence that in various ways connect these categories with each other.

Firstly, we want to highlight the relative nature of independence. It was, as has been evident in the examples above, not primarily something that students were thought to either have or not have. Rather, it was perceived as something that students may possess in certain respects and to certain degrees, while at the same time lacking it in other respects. Furthermore, the supervisors did not appear to wish for or desire some kind of ‘total’ independence in their students. This was evident when they talked about what independence, in their opinion, did not consist of, something that they frequently got into during the discussions. In those instances, they recurrently emphasised that the ideal was not in any way that the students should do the work all by themselves, without the support of the supervisors (JESWU11, JERUU11, TESWU12).

To use negations in the way the supervisors did during the discussions, generally indicates the existence of an implicit norm, and the tendency of the participating supervisors to emphasise that independence was not about students working by themselves in isolation, could, consequently, be seen as a reflection of that the prevalent ideas of what independence comprises, include such aspects. This is also addressed in research concerning independent learning, where several scholars have pointed out that independent learning is not equivalent to working in isolation (e.g. O’Doherty Citation2006; Meyer Citation2010). Knight (Citation1996) even describes the key problem with the lack of consensus surrounding definitions of independent learning as related to the fact that independent learning implies being alone and unaided (35).

Students working in isolation, without regular contact with the supervisor, was even described as something problematic if it involved students believing it meant they could do whatever they wanted or students with the attitude and approach that they had nothing to learn (TESWU11, JERUU22, TESWU11). This was, furthermore, related to the experience of the focus-group participants that students working unaided by the supervisors tended to result in final drafts handed in at the eleventh hour, which did not fulfil the expected standard or quality (TERUU22, JERUU21, JERUU21, JERUU22, JERUU22, TESWU11, JERUU12). That this kind of ‘total’ independence was seen as undesirable, could in other words be understood in light of how the predominant understandings of independence included the fact that students should be able to position their own work in relation to the scientific and disciplinary context, in which a dialogue with the supervisor was seen as necessary.

There were thus, as was also discussed in relation to the need for boundaries, certain restrictions in the kind of or degree of independence that was, ultimately, desired from the students. Yet another aspect of this was the awareness expressed by the supervisors that they could not expect the same degree of independence from all students. As has been exemplified above, several of the supervisors distinguished between a basic and an advanced level of independence, or, in some cases, between ‘minimum’ and ‘maximum’ independence (JERUU12). A minimum level of independence could consist of only choosing a subject, while an advanced, or maximum level would include critical thinking and positioning of the work and so on. Here we want to emphasise that the notion of maximum independence was in the discussions not equated with the ‘total’ independence that was seen as problematic. It was, rather, described as the maximum degree of independence that could be expected, or was desired, within the set frames and boundaries (JESWU11). The minimum level of independence was something that all students should achieve, at the very least, while an advanced level of independence was rather seen as an ideal case, which in reality was rarely encountered.

As discussed above, the supervisors generally adjusted their approach to the matter of student independence depending on the abilities and academic level of each student. But the role, nature and manifestation of student independence was also thought to vary depending on where the student was in the working process. In , we pointed out three phases of the work with the undergraduate project in which independence could be manifested: in the process, in the final product and during the defence/examination of the project. One important contrast here thus has to do with seeing process and product as two different contexts where independence may be expressed. Independence in the process was described as manifested in discussions around planning and choices of different kinds, for instance during the supervision meetings, but it was also connected to the notion of students searching for knowledge, as well as processing it and reflecting on it (JERUU11, TESWU11, JERUU11).

We want to underline that the process and the product should not be regarded as opposites in this respect, but could rather be viewed as different aspects of the same competence. Certain supervisors maintained that the process could very well be seen in the final product, and that this, hence, constituted the most important context for manifesting independence (TESWU12). Others argued that independence should be seen as the final result of the whole process, in the sense that it was the process of writing the undergraduate project that developed the students’ independence. According to this view, it was not until the students had actually finished their education that they could be expected to be truly independent (TESWU11). Up until then they had received the help of the supervisors, but were also restricted by the boundaries set up by the university or disciplinary environment they were a part of.

Yet another important contrast here is the relationship between seeing independence as a competence tied to cognitive quality, in other words as a way of ‘thinking’, or seeing independence as ‘doing’, in other words as acting independently. Taking initiatives, planning the work or making the necessary choices are examples of the aspects of independence that are connected to taking action, of ‘doing’, while criticality and creativity are examples of independence as a way of ‘thinking’.

In sum, independence could thus be said to play a role and be manifested in several different contexts, from the process of planning, writing and finding literature when writing the undergraduate project, to the product itself and, in a wider perspective, even in the professional context outside the academic education, after the finished education programme. The main differences thus appeared to be found between mind, text, talking and doing, as well as between process and product.

Concluding reflections

The ways in which central academic concepts are understood and conceptualised in universities and academic contexts are ‘likely to have a major bearing on the shaping of university curricula and of higher education policy as a whole’ (Moore Citation2011, 262). The differentiations described above, not only in the aspects that independence was thought to comprise in the process of writing the undergraduate project, but also in the degree to which it could be expected or was desired from the students, and the contexts where it was thought to be manifested, indicate that it is a complex and multifaceted concept, with many different understandings or meanings. It is, in other words, a concept that may be difficult to use constructively. It needs to be specified in order to be useful – whether the aim is to increase comparability between higher education in different countries, in accordance with the Bologna declaration, or to find a common ground for assessing undergraduate projects at one particular university or within one particular education programme. Considering how supervisors, or tutors, have been pointed out as vital for enabling and encouraging independent learning, we see it as essential to anchor the discussion of the concept of independence in undergraduate supervision in an empirical material that takes into account the views and experiences of the supervisors, as we have done in this article (cf Meyer Citation2010; Meyer et al. Citation2008; OECD Citation2017; van Grinsven and Tillema Citation2006).

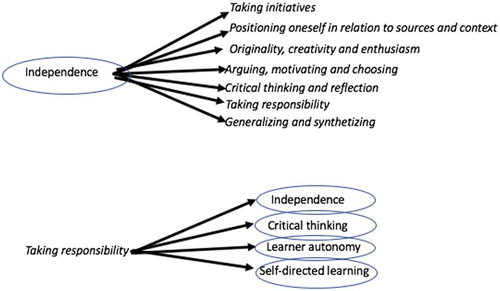

Our analysis furthermore illustrates how concepts such as argument (Lillis Citation1999; Turner Citation1999; Riddle Citation1997; Mitchell Citation1984), critical thinking (Atkinson Citation1997; Lipman Citation1987; Davies Citation2011) and autonomous learning (Gardner Citation2007; Borg and Al-Busaidi Citation2012) are closely related to independence or independent learning. Sometimes these may be hyponyms but they may also at times be used more or less as synonyms (cf Meyer et al. Citation2008; Broad Citation2006; O’Doherty Citation2006). To conclude, we would therefore like to build on Moore’s (Citation2011, 271) discussion of criticality in relation to Wittgenstein’s idea of family resemblances.

According to Wittgenstein, a large number of debates and much thinking have historically been focused on finding unitary definitions to central terms. However, (Wittgenstein Citation1958) argues that this is neither possible nor desirable, considering how language functions. All terms and concepts have a variety of meanings, as a consequence of that they are used in diverse ways in diverse contexts. He calls this ‘family resemblances’, when terms or concepts are related to one another in several different ways, in a ‘complicated network of similarities’. The idea of family resemblances is obviously relevant in relation to independence, independent learning, argument, critical thinking and learner autonomy, seeing that there are clear similarities and overlapping between these concepts, but also differences. Independence is, in other words, one part of the definition of the other concepts, at the same time as the other concepts are also part of the definition of independence.

We think of the variety in meanings and the variety of concepts sharing the same meanings as a double-sided vagueness or openness, where one term or concept can embrace several meanings, and one meaning can be expressed through several concepts, as is exemplified in .

This illustration, even if it only includes one of the categories we have discussed, namely ‘Taking responsibility’, should be seen as a summarisation of our findings. We would, in other words, argue that the variations around the concept of independence come from two directions or exist on two different levels. As shown throughout the article, independence may be understood and defined in several ways. What we want to further underline here, exemplified by , is that each of the defining attributes or criteria for this concept could, in their turn, be part of definitions for different concepts. Each understanding of independence could thus be part of the definitions of other related concepts, such as critical thinking, learner autonomy or self-directed learning.

That this kind of fuzziness is typical of concepts connected to academic learning, as has been discussed throughout the article, further emphasises the importance of being explicit when using a concept or term like independence. It is only then that it may become a truly useful concept in the continuous work of developing and improving the supervision of undergraduate students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jenny Magnusson

Jenny Magnusson is a senior lecturer at the School of Culture and Education at Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden. In her research, her main focus is academic writing and other aspects related to higher education in general and teacher education in particular. She is currently conducting research on supervision of undergraduate projects. Magnusson does most of her teaching at the Department of Teacher Education, where she also coordinates one of the teacher education programmes.

Maria Zackariasson

Maria Zackariasson is professor in European ethnology at Södertörn University, Stockholm, Sweden. Her research has mainly concerned, on the one hand, different aspects of higher education, such as the experiences of university students, student culture and now undergraduate supervision in Sweden and Russia, and, on the other hand, young people’s political and societal involvement through social movements and religious organisations. Zackariasson does most of her teaching at the Department of Teacher Education at Södertörn University, where she since 2016 is also Director of research and Deputy head of department.

Notes

1. The undergraduate project is termed differently in different academic contexts. Sometimes it is called ‘degree project’ or ‘bachelor essay’ and a direct translation of the official Swedish term would be ‘independent project’. We have chosen to use the rather neutral ‘undergraduate project’ throughout the article.

2. All in all, 60 supervisors participated in the focus-group interviews. The empirical material in the larger research project the article is based in also includes supervision communication, consisting of recorded supervision meetings, emails, drafts with comments from supervisors and steering documents related to the undergraduate project, such as assessment criteria, syllabi and curricula, from universities in Sweden and Russia.

3. This was done to ensure that all of the focus-group material was available to all of the researchers in the project, not just the ones fluent in Russian. The focus-group interviews conducted in Swedish have been translated when needed, as when using quotations from them in international contexts. As always, there is a potential risk that some of the original meaning is changed when interview quotes are translated. We have, however, tried to keep the translations as true to the meaning of the original transcripts as possible.

4. In some research contexts this analytical approach is also called thematic analysis.

5. There are also aspects of independence in relation to undergraduate supervision that are not covered in the themes or our discussion of them in this article, such as the frequency of supervision meetings, the forms these generally took and the strategies used by the supervisors. We have studied some such aspects in previous articles and intend to further examine others in forthcoming publications (cf Magnusson Citation2015, Citation2016; Zackariasson Citation2018).

6. Even though originality and creativity were often mentioned together and defined similarly, originality was also in some cases, especially in the Russian material, connected to the risk of plagiarism (e.g. JERUU11).

References

- Atkinson, D. 1997. “A Critical Approach to Critical Thinking in TESOL.” TESOL Quarterly 31 (1): 71–94. doi:10.2307/3587975.

- Benson, P. 2009. “Making Sense of Autonomy in Language Learning.” In Maintaining Control: Autonomy and Language Learning, edited by R. Pemberton, S. Toogood, and A. Barfield, 13–26. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Borg, S., and S. Al-Busaidi. 2012. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices regarding Learner Autonomy.” ELT Journal 66 (3): 283–292. doi:10.1093/elt/ccr065.

- Broad, J. 2006. “Interpretations of Independent Learning in Further Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 30 (2): 119–143. doi:10.1080/03098770600617521.

- Cukurova, M., J. Bennett, and I. Abrahams. 2017. “Students’ Knowledge Acquisition and Ability to Apply Knowledge into Different Science Contexts in Two Different Independent Learning Settings.” Research in Science & Technological Education 36 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/02635143.2017.1336709

- Davies, M. 2011. “Introduction to Special Issue on Critical Thinking in Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 30 (3): 255–260. doi:10.1080/07294360.2011.562145.

- European Ministers in charge of Higher Education. 1999. “The Bologna Declaration of 19 June 1999: Joint Declaration of the European Ministers of Education.” European Association of Institutions in Higher Education. Accessed September 1 2017. https://www.eurashe.eu/library/bologna_1999_bologna-declaration-pdf/

- Gardner, D. 2007. “ Understanding Autonomous Learning: Students’ Perceptions.” Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Independent Learning Association 2007 Japan Conference: Exploring theory, enhancing practice: Autonomy across the disciplines. Chiba, Japan: Kanda University of International Studies.

- Gurr, G. 2010. “Negotiating the “Rackety Bridge” — A Dynamic Model for Aligning Supervisory Style with Research Student Development.” Higher Education Research & Development 20 (1): 81–92. doi:10.1080/07924360120043882

- Inglehart, R., and C. Welzel. 2015. “The World Values Survey Cultural Map of the World. World Values Surveys Project.” Accessed September 1 2017. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp

- Jones, C., T. Joan, and S. Brian, ed. 1999. Students Writing in the University - Cultural and Epistemological Issues, Studies in Written Language and Literacy. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Knight, P. 1996. “Independent Study, Independent Studies and Core Skills in Higher Education.” In The Management of Independent Learning, edited by J. Tait and P. Knight, 29–37. London: Routledge.

- Krzyzanowskii, M. 2008. “Analyzing Focus Group Discussions.” In Qualitative Discourse Analysis in the Social Sciences, edited by R. Wodak and M. Krzyzanowski. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lau, K. 2017. “‘The Most Important Thing Is to Learn the Way to Learn’: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Independent Learning by Perceptual Changes.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 42 (3): 415–430. doi:10.1080/02602938.2015.1118434.

- Lee, A. 2008. “How are Doctoral Students Supervised? Concepts of Doctoral Research Supervision.” Studies in Higher Education 33 (3): 267–281. doi:10.1080/03075070802049202.

- Lillis, T. 1999. “Whose Common Sense.” In Students Writing in the University: Cultural and Epistemological Issues, Studies in Written Language and Literacy, edited by C. Jones, J. Turner, and B. Street, 127–147. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Lipman, M. 1987. “Critical Thinking: What Can It Be?.” Analytic Teaching 8 (1): 5–12.

- Magnusson, J. 2015. “Självständighetens Praktik – uppfattning och användning av begreppet självständighet i relation till det självständiga arbetet.” ASLA 10: 91–105.

- Magnusson, J. 2016. “Text i samtal: Hur texter används som resurser i handledningssamtal.” Svenskans Beskrivning 35: 343–355.

- Meyer, B. 2010. “Independent Learning: A Literature Review and a New Project.” British Educational Research Association Annual Conference 1–7.

- Meyer, B., N.Haywood, D.Sachdev, and S.Faraday. 2008. What Is Independent Learning and What are the Benefits for Students? London: Department for Children, Schools and Families.

- Mitchell, S. 1984. The Teaching and Learning of Argument in Sixth Forms and Higher Education. Hull: University of Hull: Centre for Studies in Rhetoric.

- Moore, M. G. 1973. “Toward a Theory of Independent Learning and Teaching.” The Journal of Higher Education 44 (9): 661–679. doi:10.2307/1980599.

- Moore, T. J. 2011. “Critical Thinking and Disciplinary Thinking: A Continuing Debate.” Higher Education Research & Development 30 (3): 261–274. doi:10.1080/07294360.2010.501328.

- Morgan, D. L., and R. A.Krueger. 1993. “When to Use Focus Groups and Why.” In Successful Focus Groups: Advancing the State of the Art, edited by D. L. Morgan. London & Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- O’Doherty, M. 2006. LearnHigher. Manchester: University of Manchester.

- OECD. 2017. Learners for Life: Student Approaches to Learning. OECD Publishing. Accessed 2017 September 1. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/programmeforinternationalstudentassessmentpisa/learnersforlifestudentapproachestolearning-publications2000.htm

- Pavlenko, A., and A.Blackledge. 2004. Negotiation of Identities in Multilingual Contexts, Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Clevedon; Buffalo: Multilingual Matters.

- Riddle, M. E. 1997. The Quality of Argument: A Colloquium on Issues of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Middlesex: Middlesex University.

- Schreier, M. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. London & Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Souto, C., and K. Turner. 2000. “The Development of Independent Study and Modern Languages Learning in Non-Specialist Degree Courses: A Case Study.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 24 (3): 385–395. doi:10.1080/030987700750022307.

- Swedish Council for Higher Education. 2017. “ The Higher Education Ordinance, Svensk Författningssamling 1993:100.” Ministry of Education and Research. Accessed April 11 2017. https://www.uhr.se/en/start/laws-and-regulations/Laws-and-regulations/The-Higher-Education-Ordinance/

- Turner, J. 1999. “Academic Literacy and the Discourse of Transparency.” In Students Writing in the University - Cultural and Epistemological Issues, Studies in Written Language and Literacy, edited by C. Jones, J. Turner, and B. Street, 149–160. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- van Grinsven, L., and H.Tillema. 2006. “Learning Opportunities to Support Student Self-Regulation: Comparing Different Instructional Formats.” Educational Research 48 (1): 77–91. doi:10.1080/00131880500498495.

- Wittgenstein, L. 1958. Philosophical Investigations. 2nd ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Zackariasson, M. 2018. (fc). “I feel really good now!’ – Emotion and independence in undergraduate supervision.”