ABSTRACT

Research into student experiences of learning about potentially emotionally sensitive topics tends to focus on the use of trigger warnings, with less attention paid to other teaching strategies and to broader context. This questionnaire study of 917 arts, humanities and social science students therefore sought to explore the extent to which students experienced courses as distressing, and their perceptions of the teaching strategies implemented by staff. Overall distress levels were low, and university was viewed as a good place for learning about difficult topics. However, a small number of students reported a high level of distress, particularly in relation to seminars. The importance of the overall approach taken by staff to teaching, and their personal approachability was emphasised more than specific strategies. Findings emphasised the importance of staff moving beyond a singular focus on trigger warnings, to consider student course experience more holistically. Implications for university teaching are discussed.

Introduction

Much of the writing on approaches to teaching emotionally sensitive topics in universities has focused on the specific issue of trigger warnings (TW). In the United States in particular, there has been heated debate for and against the use of TW, with much of this played out in popular media (e.g. Lukianoff and Haidt Citation2015). Recent years have seen moves towards more academic study of TW (e.g. Jones, Bellet, and McNally Citation2020), with important consideration of students’ experiences of these (e.g. Bentley Citation2017; Cares et al. Citation2019). However, debate around the use of TW is often a contentious and tightly focused one (Wyatt Citation2016), which is in danger of becoming detached from a broader consideration of how academic staff approach the teaching of potentially emotionally sensitive topics. The present study therefore explored the extent to which students experienced distress during courses containing potentially emotionally sensitive topics and their perceptions of the teaching approaches that university staff took in relation to this. It included, but went well beyond, consideration of TWs, investigating student experiences of a range of strategies employed by staff before and after the teaching of such topics. Here the literature on the teaching of sensitive topics and TWs is briefly reviewed.

There is no consensus as to what constitutes a ‘sensitive topic’ within university teaching. While many students might find a topic such as genocide difficult to learn about, responses to other topics, such as violence or suicide, might depend on an individual student’s prior life experiences. Responses to yet other topics, such as race, class, or sexuality, might depend on a student’s own identity as well as their experiences. For some students, particularly those with past experience of trauma, it may be very difficult to predict which topics or teaching materials may be experienced as difficult (Colbert Citation2017). Topics might also be experienced as more or less sensitive depending on the composition of the class, the type and context of teaching, and the lecturer involved (Wyatt Citation2016).

There is now a substantial literature on pedagogical approaches to teaching sensitive topics. This literature often focuses on the importance of interpersonal relationships and creating a particular kind of space, e.g. safe (Klesse Citation2010; Pilcher Citation2017) or brave (Alakoc Citation2019). Other common elements are establishing expectations of respectful discussion (Lichtenstein Citation2010), encouraging reflexivity, recognising staff and student positionality (Klesse Citation2010), and the use of creative pedagogies (Pilcher Citation2017; Alakoc Citation2019). There are various justifications for offering a learning and teaching experience which it is known in advance may cause distress in some students. The most obvious of these is where sensitive topics need to be covered in a professional practice programme. Another justification is that encountering sensitive and potentially distressing topics can be transformative (Simon Citation2011). Here Britzman’s notion of ‘difficult knowledge’ is frequently invoked (Britzman Citation1998, Citation2013). Alongside knowledge of events that are traumatic (e.g. war and genocide), ‘difficult knowledge’ also includes ‘learning encounters that are cognitively, psychologically and emotionally destabilising for the learner’ (Bryan Citation2016, 10). Indeed, Gubkin (Citation2015) emphasises the need to distinguish between learning which emotionally challenges or discomforts, and that which does emotional harm. What is not always clear though is how emotionally sensitive topics might be experienced differently, depending on how and where they are encountered in a course: whilst Ashe (Citation2009) suggest that seminars may be particularly problematic, there is less knowledge of the extent to which sensitive topics are experienced as distressing when they are encountered during e.g. course lectures, reading and assessments.

Moving from the broad principles which can underpin the teaching of sensitive topics to the more narrowly focused literature on TW, we can trace the term from its origins in online blogs, as well as clinical work in post-traumatic stress disorder (Colbert Citation2017; Wyatt Citation2016). In recent years the discussion has extended to TW for teaching on university campuses. There is no definitive definition in the academic literature (see George and Hovey Citation2020 for a more detailed discussion), but TWs can be broadly defined as any advanced cautionary statement about a topic which might cause distress to others (Wyatt Citation2016).

This debate is covered comprehensively elsewhere (e.g. Wyatt Citation2016), but in brief, arguments against TW include that they may: be a threat to academic freedom; run counter to the purpose of higher education by suggesting that challenging ideas are dangerous; encourage students to view themselves as fragile and unable to face discomfort in the pursuit of learning; lead to students avoiding rather than confronting triggering situations; cause students to remember the teaching as more negative (Lukianoff Citation2016). It is also suggested that TW may be ineffective (Jones, Bellet, and McNally Citation2020) and, furthermore that because triggers are varied and individual to different students, it would be logistically impossible to warn against every potentially triggering situation (Boysen and Prieto Citation2018). In contrast, proponents argue that TWs are: an appropriate accommodation for students with trauma-related mental health difficulties; an act of inclusion and empathy towards students; a means of fostering open and authentic discourse between staff and students; a reminder to non-affected students about the need to discuss topics sensitively (Nolan and Roberts Citation2021); and – by allowing students to emotionally prepare for difficult material – a means of facilitating, rather than avoiding the teaching of sensitive topics (Carter Citation2015). Yet others report findings suggesting that TWs are neither significantly helpful nor harmful in terms of emotional impact on students (Sanson, Strange, and Garry Citation2019).

Boysen and Prieto (Citation2018) surveyed psychology college and university staff and reported that under half used TWs, and that they tended to be reserved for potentially traumatic topics, and that they were very seldom viewed as necessary for topics such as race, socio-economic status, and religion. A small number of recent studies have examined student experiences of TWs. Beverly et al. (Citation2018) surveyed medical students who suggested that, because of the nature of their profession, they needed to develop skills of handling distressing material through university. Similarly, Bentley (Citation2017) surveyed undergraduate students taking courses on war or terrorism. Some felt that TWs were beneficial, particularly for those with pre-existing conditions (e.g. mental health conditions), and particularly if the warnings were not excessive. Some, though, reported being more apprehensive about the learning as a result of the TWs, and others felt that they were superfluous when it was obvious (e.g. from the course title), that the course would contain emotionally difficult material.

Whilst relatively small scale, these studies provide an important perspective on staff and student experiences of TWs. However, as Storla (Citation2017, 190) noted, TWs alone cannot be expected to ‘shoulder the burden’ when teaching emotionally difficult material; while much has been written about TWs there is less available on other practical strategies that tutors can use. From the limited literature, suggestions include making sure that students know they can opt out or leave a session (Dalton Citation2010), ensuring students have information about course content (Lowe Citation2015; Pilcher Citation2017), and providing opportunities to de-brief (Pilcher Citation2017) or being available after the teaching sessions if students wish to talk (Caswell Citation2010). However, in contrast to TWs, there has been less research into this broader range of approaches. There is therefore now a need to explore how students experience this wider range of teaching strategies.

The research to be reported here, was a large questionnaire study of undergraduate and postgraduate students in arts, humanities, and social science, studying courses which were identified as containing potentially emotionally sensitive material. These disciplines were chosen because they afforded the opportunity to explore a very wide range of teaching around potentially emotionally sensitive topics. A broad definition was adopted here, mindful that emotionally sensitive topics might include both those which may evoke previous trauma (e.g. sexual violence) as well as those which may be sensitive to particular groups (e.g. race, religion) (Lowe and Jones Citation2010). Here, as with other research studies (e.g. Caswell Citation2010), we adopt Lee and Renzetti’s (Citation1993, 9) broad definition of a sensitive topic as one which ‘involves potential costs to those participating … [going] beyond the incidental or merely onerous’.

The questionnaire sought to explore three questions in relation to student experiences of university courses containing potentially emotionally sensitive topics. Firstly, we asked to what extent do students perceive these courses and course components as potentially or personally distressing? Secondly, what teaching strategies do students perceive that staff have implemented (or could have implemented) in the teaching of potentially emotionally sensitive topics? Thirdly, what actions do students report that they themselves take in relation to any personally distressing teaching?

Methods

Participants

Participants were 917 undergraduate (UG) and postgraduate taught (PGT) arts, humanities and social science students within a Russell group university. Potential participants were identified using the following process: initially, course titles were searched in the internal university course catalogue in order to identify arts, humanities and social science courses which might contain potentially emotionally sensitive topics in the course content. This was done using a list of 49 core keywords drawn from the existing literature in this field. This list was then expanded through discussion and a thesaurus search using the PsycINFO database. The final full listFootnote1 of 234 search terms included e.g. ‘death’, ‘violence’, and ‘mental health’. 1477 course titles were identified, which was then reduced to 198 courses on the basis of a course descriptor review conducted by two members of the research team. Courses were excluded if the course descriptor indicated that the substantive course content was very unlikely to trigger emotional distress. All university staff involved in teaching across the arts, humanities and social sciences were then contacted via a cascade email, asking them to identify any courses on which they taught which may contain potentially emotionally sensitive topics, but which had not been picked up during the keyword course title search. An additional 21 courses were added using this method, and so there were 219 courses in the final list.

The 6599 students (around a third of all UG and PGT arts, humanities and social science students in the university) who had taken one or more of these courses in the previous academic year were then contacted and asked to complete an online questionnaire. Of these, 920 students responded (14% response rate), and 917 were included in the final analysis (2 were excluded because they stated that they had not taken one of the courses identified; 1 was excluded due to fictitious responses). provides participant demographic information.

Table 1. Demographic information on participants (N = 917)

Methods

Data were collected via an online questionnaire. This gathered demographic data, including age, usual country of residence, ethnicity, and programme and year of study. Students were then asked to identify, from the list of 219, the course(s) that they had taken over the previous academic year. They were then asked to focus on the one that they had taken most recently. They were asked to rate the course components (lectures, seminars, reading, assignments, and ‘other’) in terms of how potentially distressing they were (even if they themselves had not experienced these components as such) and how personally distressing they had found these components. Possible responses for each component were: ‘none were distressing’, ‘some were a little distressing’, ‘some were very distressing’, ‘most were a little distressing’, ‘most were very distressing’. They were also asked about the actions which they recalled had been taken by teaching staff before and after the teaching; and any views they had on the way in which these could be further developed. Questions were mainly closed format, but the sections on students’ personal experiences of the course components and of teaching strategies implemented also included a number of open-ended questions, generating qualitative data.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the first author’s institute ethics committee prior to the study commencing (approval no. 747). The questionnaire was pilot tested with four university alumni who had previously studied at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Following the resultant minor changes (e.g. clarification of terminology), potential participants were contacted via email, and provided with details of the study, and a link to the online questionnaire site. On this site, students were provided with study information and only proceeded to the questionnaire once they indicated that they consented to participate. The questionnaire took around 10 minutes to complete, and the questionnaire site remained open for one month. Participation was on an anonymous basis: whilst students were asked to leave their contact email if they wished to participate in a follow-up interview, this information was separated from the data prior to analysis.

Analysis

Quantitative data were exported into SPSS for analysis. There was a small amount of missing data, as not all participants responded to all questions: the number of respondents therefore varies slightly across the analysis. The five categories used to rate the potential and personal distress level of each of the course components (lectures, seminars, course reading, assignments, and ‘other’), was converted into a simplified 4-point scale: from 0 (not at all distressing) to 3 (very distressing). This was done by collapsing the categories ‘some were very distressing’ and ‘most were a little distressing’ into a single point (2), in order to create an ordinal scale which could be more readily analysed. In analysis, the total mean rating for the four ‘core’ course components (lectures, seminars, reading and assignments) was also calculated, in order to provide a value for the course as a whole.

The free-text data generated by the open questions were exported into a single document for thematic analysis. Codes, which were semantic rather than latent, were not established in advance, but many were associated with specific questions (e.g. ‘Was there anything that your lecturer or tutor did which was particularly helpful in relation to the teaching of the potentially sensitive topic?’) while others emerged through the constant comparative approach (Miles and Huberman Citation1994) to more open-ended questions (e.g. ‘Leave a note if you wish to tell us anything else about this topic’). All data were allocated to one or more codes which were then organised into 26 broad categories. The resultant document (54 pages) was hosted on a secured shared platform and read and re-read by all authors, each adding notes on their interpretive reflections in which they identified patterns of shared meaning across the data and the categories (Braun and Clarke Citation2021). Through an iterative and collaborative process, themes were created from these notes and were then reviewed and adapted where required on the basis of re-reading the data (Nowell et al. Citation2017). This reflexive approach to thematic analysis was more experiential than critical and, although informed by previous research, was more inductive than deductive (Braun and Clarke Citation2021). For the purposes of this paper only the themes from this analysis which illuminate the findings from the quantitative data are reported.

Findings

Perceptions of courses and course components as potentially or personally distressing

Students were asked to rate course components (lectures, seminars, reading, assignment, and ‘other’) in terms of how potentially distressing they considered them (even if they did not experience them as such) and also how personally distressing they found them. We first explored how many course components were reported to be potentially or personally distressing. As shows, 15% of students considered none of the components to be potentially distressing, but most considered at least one component to be. In total 771 (85%) of the 912 students who responded to this question, reported that at least one component of their course was potentially distressing. The most common response was that four course components were potentially distressing. However, in terms of whether they themselves personally experienced course components as distressing, the data in shows that many students (46%) did not themselves experience any components as personally distressing. Overall, 489 (54%) of 913 students who responded said that they had personally experienced one or more components of their course as distressing to some degree.

Table 2. Number of course components considered potentially or personally distressing

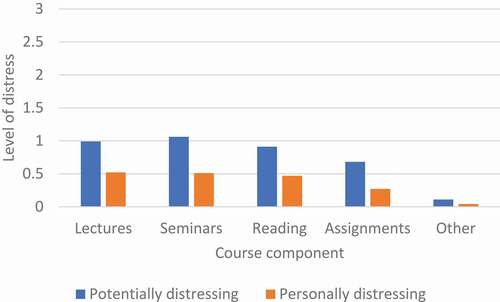

We next explored the level of reported potential or personal distress. Across all responding participants, on a scale from 0 (potentially not at all distressing) to 3 (potentially very distressing) the mean (SD) overall rating of potential distress (from the four core course components) was 0.91 (0.62), indicating that for their course as a whole, students viewed the level of potential distress as low.

In terms of level of personal distress, across all responding participants, for their course as a whole (the four core course components), the mean (SD) overall course rating was 0.45 (0.56), indicating that the overall level of personally experienced distress was again low. Thirteen (1%) individuals rated at least one component of the course at the highest level of personal distress, most commonly seminars (N = 7). These individuals were most commonly female (N = 12), studying at undergraduate level (N = 9) and from the UK (N = 11).

We then explored the level of reported potential or personal distress of each of the course components. As shows, the level of potential and personal distress was relatively low for all components, and in all cases the potential for distress was rated as higher than the personal distress experienced. Seminars were felt to have the highest potential for distress, and assignments (and ‘other’) the lowest. In terms of personal distress, all course components were rated at a similar level, though with assignments and ‘other’ as slightly lower. The examples included in the ‘other’ personally distressing category, included watching films (6), experiential exercises/role play (3) and site visits (1).

Free text responses confirm that only a very small minority of students reported experiencing a high level of personal distress. Many students suggested that it is part of the university experience to learn about sensitive topics and even those who felt somewhat distressed often described finding the teaching valuable. Indeed, for some the experience of learning about sensitive topics was beneficial and empowering:

While many topics are potentially very distressing, those are also the topics that are the most important to be taught about, read about, and discuss in classes. The lectures that have made me feel angry and sad have also often been the lectures that have motivated me the most to work for social change. (UG/FFootnote2)

One student (UG/F) described the opportunity to discuss sensitive material as ‘liberating’ as it allowed her to discuss things it wasn’t possible to talk about elsewhere. For others, the opportunity to learn about difficult topics was part of the appeal of the course. One student stated:

The nature of the course implied that there would be potentially distressing topics, but that was part of the appeal of the class. Talking about highly contentious issues was key to the process and I do not think that they should be avoided. (PGT/F)

Students on professional training courses (e.g. nursing studies, teacher education, social work) felt that it was important that the courses prepared them for dealing with the potentially emotionally difficult topics that they would encounter in practice. As one respondent explained:

For our course, whilst there will be times when students like myself are triggered by certain things, we have to be strong and understand the emotional labour that we undergo, and thus, for example, when we have to do last offices (that is, with respect and dignity provide care and support for someone who has just died and prepare them for the mortuary), we simply have to be strong, and there is not really an option to ‘leave’ because that is our job. (UG/F)

A major theme running through the open comments was that university is a place where distressing ideas and issues ought to be discussed, and that to avoid them would be ‘a disservice to the students’ (PGT/F) ‘a kind of censorship’ (UG/M) or even ‘dangerous’ (UG/F).

Despite the strong view that such topics ought to be addressed, with no student suggesting any topic should be ‘off limits’, there were some components of their courses which students identified as more likely to be the source of distress. The first was seminars, where comments made by other students could be problematic. For example, one student found that students unaffected by issues ‘could be quite insensitive’ (UG/F), another that ‘students who have no personal experience with the subject were quite abrasive on discussions’ (PGT/F). This was particularly, although not exclusively, an issue where the sensitive topic was poverty or social class. Unlike race and gender, social class is a hidden identity, and one student observed there was:

a general tendency in academia to speak about issues like no one in the room might have experienced them. Although I did not find this to be an issue with the tutor, I did with my peers in the class. (PGT/A)

Similarly, another student suggested that:

many students at the university are not aware of there being students at this university who come from heavily disadvantaged backgrounds. (UG/F)

The second course component which was identified by students as particularly distressing (both personally and potentially) was the use of film. For example, one student reported that

Film screenings were part of this course and three of the films featured strong images of sexual violence that would likely have proved very distressing to anyone with experience of sexual abuse. (PGT/F)

Actions students perceive that staff have taken in the teaching of potentially emotionally sensitive topics

Students were asked about any action that they perceived staff to have taken in relation to the teaching of potentially sensitive topics, prior to the teaching. Overall, 160 (17%) students reported that the topics had not been potentially distressing enough to require action prior to teaching. Of the other 757 students, the majority (n = 611, 67%Footnote3) described at least one action that the course staff had taken prior to the teaching, and only 146 (16%) said that no action had been taken. shows the specific actions that students reported that staff had taken prior to teaching, with whole class warnings and information in course handbooks being the most common.

Table 3. Student-reported staff action in relation to the teaching of potentially emotionally sensitive topics

Students were also asked about any action that they perceived staff to have taken after the teaching. Overall, 249 (27%) students reported that the topics had not been potentially distressing enough to require action after teaching. Of the other 668 students, most (n = 379, 41%) said that no action had been taken after teaching, and 289 (32%) described at least one action that the course staff had taken. shows the actions that students reported that staff had taken after teaching, with whole class debrief, and information on personal tutor support and support organisations being the most common.

Overall, 627 (68%) of the students described action that staff had taken at some stage (either before or after teaching). Where action was reported as not having been taken, in many cases it was not felt to have been necessary.

The qualitative data indicated that, for many of the participants, it was not the specific action that tutors took in relation to teaching potentially emotionally sensitive topics that was most important, but the way that they more broadly approached the teaching of the topic. Teaching staff were variously described as ‘tactful’, ‘approachable’, ‘kind’, ‘understanding’, ‘warm’, ‘generous’, ‘helpful’, ‘thoughtful’, ‘sensitive’, ‘delicate’ and ‘considerate’, with the end result being the creation of ‘a secure teaching environment’ leading to a ‘very comfortable experience’. Additionally, there were frequent references to the professionalism and skill of staff, with this comment typical of many:

I have to say that the staff are truly skilled at balancing being professional and very welcoming/warm/supportive. (PGT/F)

Similarly, a number of students on professional training courses noted that the manner in which sensitive topics were taught, impacted their own practice. For example, an Education student noted a course that their tutor,

taught in a way to show these problems children face but was then passionate to drive change and make us think about how as teachers we can help them (UG/F)

There was resistance from a very small minority of students to the idea that staff ought to do anything to offer students support, and for an even smaller minority there was some evident dismay that they were being asked what support they needed. For example, one wrote simply ‘I have a backbone’ (UG/M), another that ‘it seems to me fairly patronising and ridiculous to suggest that we should all be wrapped in cotton wool’. (UG/M), and a third thought that if students couldn’t cope with topics such as ‘genocide, terrorism and realities of war, they shouldn’t be taking the course in the first place’. (UG/M). Others were less direct in their comments, and a typical response of this kind was:

we are all adults who have chosen a course that is highly likely to contain distressing material, and so I feel that we did not need emotional guidance. It may have even come across as a little patronising. (UG/F)

Beyond comments about the skill and professionalism of the majority of staff, there were four actions by staff highlighted by many students as being important in making the experience more positive. These can be summarised as: the way material was presented, establishing the class atmosphere, provision of warnings, and offering choice.

The first of these relates to staff consideration of how difficult material was presented. Some students noted the serious, objective, and scholarly presentation of the topic, and said it was important that their lecturer did not ‘foment’ or ‘sensationalise’ the discussion. One student used the term ‘maturely’ to describe how the material was handled, another described the tutor as using ‘an academic manner’. This approach appeared to give some distance between the topic as personal experience and as an area of academic study, although one response expressed some frustration at what they saw as an artificial separation:

I think I’d just like it acknowledged that we can hold ‘hats’ of personal experience and of being a professional at the same time (rather than one or the other). Some lecturers acknowledge this more than others (PGT/F)

The second approach was the care taken by the tutor to create a supportive atmosphere in class:

Within my programme … we often discuss distressing topics in terms of social injustice …. but we’ve created a community where I feel supported and comfortable to discuss issues as they arise. (PGT/F)

In addition to the sensitivity and approachability of staff already noted, students reported that this class atmosphere was sometimes created through the use of specific techniques, including setting explicit ground rules, a verbal contract, or drawing up an agreement. In some cases this was done through an open discussion about the sensitive nature of the topic, often with encouragement, and the provision of space and time within which to explore why it was distressing. This seemed to be particularly welcomed by students dealing with some of the most sensitive topics:

Talked about it, trying to hold it and create space for all types of different emotions and reactions so facilitated the group process. (PGT/F)

This encouragement to reflect on their distress and examine it is similar to the experience of the students on professional training courses noted above; in both the distress is educative, rather than something to necessarily be minimised or avoided.

The third approach, to give a warning, came up in response to questions both about what actions students perceived that staff had taken, and what actions students would have liked them to take. The use of the word ‘warning’ in multiple responses may be a result of the wide-spread use of the term ‘trigger warning’ in popular discussion. In fact, what students seemed to be asking for was simple, ‘accurate and proportionate’ information about the nature of the content that was coming up, with the term ‘advanced notification’ being used by some, with one person saying that simply ‘knowing about the topics beforehand was helpful to me’. (PGT/F). This advanced notification could be communicated in various ways, including in the course title, the handbook, in a lecture announcement, or by email. Whilst the specific method of communication seemed less important, the provision of information was clearly appreciated:

The lecturer acknowledged that the content of the session could cause some anxiety, and I think by the lecturer saying this at the time it made me feel much more relaxed and that everyone might feel a little uncomfortable because of some of the content … (PGT/F)

The lecturers were very sensitive. I have been in a violent (physical and mental) relationship previously and some course content was on domestic violence. I’m sure other students would have experienced similar situation as me and perhaps been more distressed than me, but lecturers were sensitive and made students aware before lectures begun. It brought back personal memories, but the content itself was not overly distressing which was good. (UG/F)

Although there was a very small number who felt that the use of TWs in a university was inappropriate, the vast majority of those who commented had found them valuable, and many students who had not received such a warning thought it would have been appropriate and helpful.

Offering choice where possible was the fourth action highlighted by students as useful, and this was especially the case when an alternative was also provided. However, in most cases the choice was simply to not attend a particular class or lecture, or to leave a session if it became difficult. One student who had not been told in advance that they could leave later found it difficult to look at any materials associated with the topic because it brought back the ‘the anxiety of being trapped in the classroom’ (PGT/F), indicating how important having this option was seen to be, albeit for a very small number of students on a very small number of courses. Students also mentioned the importance of being offered choice, wherever possible, in terms of the focus of their assessment, either exam, course work or dissertation, with it being important that no one would be forced to answer a question on a sensitive topic.

Actions taken by students

Students were asked whether they had made teaching staff aware of their distress. The majority of the 894 students who responded, reported that this was not applicable to them, either because they had not found the teaching distressing: 449 (50%), or because they had not felt it necessary to tell teaching staff: 343 (38%). A further 56 (6%) said they had not told teaching staff for another reason, for example because they felt emotionally unable, they had had no opportunity, the teaching staff felt unapproachable or they had not been expecting the topic. Only 38 (4%) said that they had told teaching staff, either directly or via another member of university staff. A further 8 (1%) of students gave another response which didn’t fit into these categories.

Discussion

This study explored undergraduate and postgraduate students’ experiences of taking courses which covered potentially emotionally sensitive topics, looking at how distressing they found these courses and what actions they perceived staff to have taken in relation to the teaching of these topics. Whilst much recent work in this field has focused on the use of TWs, this study sought to explore experiences and teaching strategies more broadly.

The findings stand in stark contrast to media headlines about ‘snowflake students’ (e.g. Sandbrook Citation2017): overall distress levels were very low, and there was a strong view that university was a place for the teaching of sensitive topics. In some cases, such topics were seen as forming part of the vital preparation for students on professional practice degrees, but in other cases contentious topics were part of the course appeal or reported as motivating students to lead transformational societal change. This finding resonates with previous studies which advocate ‘leaning in’ to sensitive topics as a way of deepening learning, and which suggest that this emotional engagement is a pre-requisite for transformative learning (e.g. Gilbert Citation2020; Lowe Citation2015).

However, whilst overall distress levels were low, there was a small number of students who reported having experienced high levels of distress in relation to teaching, most commonly in relation to seminars. This supports previous research which identifies interactions between students in class as potential flash points for distress (Pilcher Citation2017; Lowe Citation2015). Similarly, Ashe (Citation2009) noted that seminars can be highly problematic and require careful planning to avoid them becoming a space in which hostility between students develops. In some cases, distress related to personal previous experiences, such as experiences of violence. In others it related to how the teaching connected with the student’s own identity; this is consistent with findings from previous smaller-scale qualitative or reflective studies (e.g. Lichtenstein Citation2010; Nixon and McDermott Citation2010; Ashe Citation2009). However, unlike previous research which has largely focused on teaching topics relating to race, ethnicity and sexuality, our findings show that some students were also concerned with teaching relating to their identity in terms of social class.

Importantly, very few students made their teaching staff aware of their distress; a greater number wanted to make staff aware but felt unable to do so. While teaching staff might assume that any student who knows they are likely to be upset by a topic will inform them in advance, this is clearly not the case. This suggests the need for a ‘mainstreamed’ approach, whereby staff consider implementing teaching strategies in relation to their teaching of potentially emotionally sensitive topics, regardless of whether they know of a particular student who would benefit from it.

The general manner of staff and their approach to teaching were, however, emphasised far more than specific teaching strategies in the qualitative data. The creation of an open, warm and respectful class atmosphere, in which difficult material is not sensationalised, and is taught by staff who are perceived to be approachable and understanding, was reported by many students as having supported them to learn about emotionally difficult topics. It was within this context that specific strategies often appear to have been implemented: more than two-thirds of students reported some action that staff had taken in relation to teaching the emotionally sensitive topic, either before and/or after teaching. A wide range of strategies were reported, from the provision of alternative learning methods, to reminders about personal tutor support and relevant support organisations. The action most commonly reported was the provision of a TW, and students generally supported this: the majority of qualitative responses indicated that a proportionate, non-sensational ‘heads up’ was considered appropriate. This broadly accords with findings from previous smaller scale studies which found that – although student views were mixed – many considered that a ‘light touch’ warning (Bentley Citation2017, 480) for distressing topics was appropriate, and might be particularly beneficial for students with pre-existing (e.g. mental health) conditions (Bentley, Citation2017; Beverly et al. Citation2018). That students seem to appreciate TWs is somewhat surprising given that experimental design studies indicate that such warnings may be ineffective at reducing, or may even increase, anxiety and negative affect (e.g. Jones, Bellet, and McNally Citation2020; Sanson, Strange, and Garry Citation2019). This discrepancy may be due to differences in sampling (e.g. experimental design studies often, though not always, have participants who are trauma survivors) and specific outcomes explored. Alternatively, it may be because the experimental design studies often assess TW efficacy outwith a university teaching-context: whilst this brings the high degree of control necessary for an experimental study, it raises the possibility that TWs may be relatively ineffective when delivered in isolation, but more effective when they are delivered within the broader context of a university course and ongoing relationships with staff. Indeed, it may be that the ‘efficacy’ of the TW lies as much in what it communicates to students about staff concern for student wellbeing, as it does about a specific distressing aspect of the course content. TWs may perhaps also be appreciated by students despite not leading to reduced anxiety. Further research is required to explore this, and to understand more about TWs delivered within the context of university teaching, in order to better establish when, how and by whom these are best delivered to support positive student experiences when learning about difficult material.

As in previous research (e.g. Hulme and Kitching Citation2017), our findings also suggested students welcomed choice on aspects such as assessment topic or materials with which to engage. Whilst this might be more problematic on some degrees (e.g. professional practice), it can perhaps be more readily provided on others. However, our findings suggest that in most cases the students’ perception of the choice being offered is ‘take it or leave it’, and only a very small number of students reported in their qualitative comments that they had chosen to avoid sessions or material. Care should be taken at the course design stage to consider the range of ways in which the learning outcomes can be met, to avoid students having a choice only between engaging with distressing material or not engaging at all. We suggest that providing options is not only valuable for those students who exercise that choice; it is also valuable for building relationships with the generality of students as it signals that their teacher is concerned for their wellbeing.

Inevitably, the study had a number of limitations. In some cases, the students were reporting on courses that they had taken in the previous semester, and in a small number of instances students said they could not remember whether a particular action had been taken by staff on the course. In future research, gathering ‘real time’ data during the running of a course may avoid this issue. We aimed in this study to gather data across a large number of students and courses, and the sample was based on courses selected through keyword search and course organiser recommendation. Inevitably this means that some courses with potentially emotionally sensitive content may have been missed, and others may have been included that were perhaps less emotionally sensitive than suggested by the course descriptor.

Additionally, whilst we asked students about actions taken by staff before and after the teaching of emotionally sensitive topics, we did not ask about actions taken during the teaching. The qualitative responses did, however, provide a number of insights into this. More broadly, whilst the primarily quantitative design of this study allowed us to develop a comprehensive picture based on a large sample of student participants, it was clear that many important insights arose from the qualitative data, though there were challenges in analysing open question qualitative data from such a large sample. More extensive interview data gathered from smaller samples therefore appears to be an important next step in further exploring this topic. Indeed, gathering qualitative data from both staff and students about the same course(s) may also be helpful in developinga more holistic picture. Finally, teaching practice and students’ experiences may also vary across contexts and universities; a similar study in a wider range of universities in the future would help determine the extent to which the findings are universally applicable.

Conclusions

This large-scale study sought to explore the experience of both undergraduate and postgraduate students of learning about potentially emotionally sensitive topics. It moved away from a narrow focus on TWs to consider a fuller range of approaches and did so in a natural setting of students’ real-world experience. The approach we took fits Wyatt’s (Citation2016) view of the importance of understanding the teaching of emotionally sensitive material as embedded within student-staff relationships and specific course contexts.

The findings of this study have clear implications for practice in higher education. Whilst only small numbers of students may find a particular course or topic emotionally distressing, the actions taken by staff may make a substantial impact on the experience of those students, even if staff are not aware of which particular students may benefit. Academic practice courses for staff should explore the teaching of potentially emotionally sensitive topics in a broad fashion, looking well beyond the provision of TWs to consider the whole ‘journey’ of a course: from course design, to atmosphere created in the class, to assignment choice. As Wyatt (Citation2016, 29) emphasised, a prescriptive approach is not appropriate here: rather, staff should be encouraged to understand the ‘ecologies of their classrooms’, and to reflect on how to teach particular topics, to a particular group of students, at a particular stage of their learning, in a particular academic setting, within a particular degree, at a particular university.

Overall, our findings emphasise that students do wish to learn about emotionally challenging topics. They also underline the importance of supporting the development of university staff to view the teaching of emotionally sensitive topics in a mainstreamed and holistic manner, enabling them to embed consideration of this complex issue from the earliest stages of course design.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30 KB)Acknowledgments

Thanks are extended to all the students who took the time to share their experiences and participate in the study. We are also grateful to two Education students for input at the funding and research design stage, Colin Brough for support in course identification, Marie Hamilton for administrative support, and to members of the Higher Education Research Group for feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

K. Cebula

K. Cebula is a Senior Lecturer in Developmental Psychology. Her research focuses on the experiences of children with developmental disabilities and their families. She also explores topics around student mental health, with consideration of implications for the development of university staff teaching practices.

G. Macleod

G. Macleod is a Senior Lecturer in Education. Her research interests focus on interpersonal relationships across a range of education contexts, and the experiences of marginalised groups in particular.

K. Stone

K. Stone Until September 2020, Kelly Stone was a lecturer in primary education (early literacies) at the University of Edinburgh, where her key research and teaching interests were critical literacies and the use of children’s literature as a platform for social justice in education.

S.W.Y. Chan

S.W.Y. Chan is the Charlie Waller Professor of Evidence-Based Psychological Treatment. As an academic clinical psychologist her research focuses on identifying factors that can help improve adolescents’ and young adults’ mental health and wellbeing in educational, clinical, and community settings.

Notes

1. See supplementary material.

2. Notation following quote indicates whether the participant was: an undergraduate (UG) or postgraduate taught (PGT) student; female (F), male (M), or another (A) gender identity.

3. Percentages reported here are of whole sample (N = 917).

References

- Alakoc, B.P. 2019. “Terror in the Classroom: Teaching Terrorism without Terrorizing.” Journal of Political Science Education 15 (2): 218–236. doi:10.1080/15512169.2018.1470002.

- Ashe, F. 2009. “The Pedagogical Challenges of Teaching Sexual Politics in the Context of Ethnic Division.” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 2 (2): 1–19. doi:10.11120/elss.2009.02020003.

- Bentley, M. 2017. “Trigger Warnings and the Student Experience.” Politics 37 (4): 470–485. doi:10.1177/0263395716684526.

- Beverly, E., S. Díaz, A. Kerr, J. Balbo, K. Prokopakis, and T. Fredricks. 2018. “Students’ Perceptions of Trigger Warnings in Medical Education.” Teaching and Learning in Medicine 30 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1080/10401334.2017.1330690.

- Boysen, G.A., and L.R. Prieto. 2018. “Trigger Warnings in Psychology: Psychology Teachers’ Perspectives and Practices.” Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology 4 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1037/stl0000105.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021. “One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18 (3): 328–352. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Britzman, D.P. 1998. Lost Subjects, Contested Objects: Toward a Psychoanalytic Inquiry of Learning. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

- Britzman, D.P. 2013. “Between Psychoanalysis and Pedagogy: Scenes of Rapprochement and Alienation.” Curriculum Inquiry 43 (1): 95–117. doi:10.1111/curi.12007.

- Bryan, A. 2016. “The Sociology Classroom as a Pedagogical Site of Discomfort: Difficult Knowledge and the Emotional Dynamics of Teaching and Learning.” Irish Journal of Sociology 24 (1): 7–33. doi:10.1177/0791603516629463.

- Cares, A., C. Franklin, B. Fisher, and L. Bostaph. 2019. ““They Were There for People Who Needed Them”: Student Attitudes toward the Use of Trigger Warnings in Victimology Classrooms.” Journal of Criminal Justice Education 30 (1): 22–45. doi:10.1080/10511253.2018.1433221.

- Carter, A.M. 2015. “Teaching with Trauma: Trigger Warnings, Feminism, and Disability Pedagogy.” Disability Studies Quarterly 35 (2). doi:10.18061/dsq.v35i2.4652.

- Caswell, G. 2010. “Teaching Death Studies: Reflections from the Classroom.” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 2 (3): 1–11. doi:10.11120/elss.2010.02030009.

- Colbert, S. 2017. “Like Trapdoors: A History of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and the Trigger Warning.” In Trigger Warnings: History, Theory, Context, edited by E.J.M. Knox, 3–21. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Dalton, D. 2010. “‘Crime, Law and Trauma’: A Personal Reflection on the Challenges and Rewards of Teaching Sensitive Topics to Criminology Students.” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 2 (3): 1–18. doi:10.11120/elss.2010.02030008.

- George, E., and A. Hovey. 2020. “Deciphering the Trigger Warning Debate: A Qualitative Analysis of Online Comments.” Teaching in Higher Education 25 (7): 825–841. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1603142.

- Gilbert, D. 2020. “The Politics and Pedagogy of Nationalism: Authentic Learning on Identity and Conflict.” Journal of Political Science Education. doi:10.1080/15512169.2020.1762625.

- Gubkin, L. 2015. “From Empathetic Understanding to Engaged Witnessing: Encountering Trauma in the Holocaust Classroom.” Teaching Theology & Religion 18 (2): 103–120. doi:10.1111/teth.12273.

- Hulme, J.A., and H.J. Kitching. 2017. “The Nature of Psychology: Reflections on University Teachers’ Experiences of Teaching Sensitive Topics.” Psychology Teaching Review 23 (1): 4–14.

- Jones, P.J., B.W. Bellet, and R.J. McNally. 2020. “Helping or Harming? The Effect of Trigger Warnings on Individuals with Trauma Histories.” Clinical Psychological Science 85 (5): 905–917. 216770262092134.

- Klesse, C. 2010. “Teaching on ‘Race’ and Ethnicity: Problems and Potentialities Related to ‘Positionality’ in Reflexive and Experiential Approaches to Teaching and Learning.” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 2 (3): 1–27. doi:10.11120/elss.2010.02030003.

- Lee, R.M., and C.M. Renzetti. 1993. “The Problems of Researching Sensitive Topics: An Overview.” In Researching Sensitive Topics, edited by C.M. Renzetti and R.M. Lee, 3–13. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Lichtenstein, B. 2010. “Sensitive Issues in the Classroom: Teaching about HIV in the American Deep South.” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 2 (3): 1–23. doi:10.11120/elss.2010.02030002.

- Lowe, P. 2015. “Lessening Sensitivity: Student Experiences of Teaching and Learning Sensitive Issues.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (1): 119–129. doi:10.1080/13562517.2014.957272.

- Lowe, P., and H. Jones. 2010. “Teaching and Learning Sensitive Topics.” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 2: 3. doi:10.11120/elss.2010.02030001.

- Lukianoff, G. 2016. “Trigger Warnings: A Gun to the Head of Academia.” In Unsafe Space: The Crisis of Free Speech on Campus, edited by T. Slater, 58–67. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lukianoff, G., and J. Haidt. 2015. “The Coddling of the American Mind.” The Atlantic, September. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/09/the-coddling-of-the-american-mind/399356/

- Miles, M.B., and A.M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Nixon, J., and D. McDermott. 2010. “Teaching Race in Social Work Education.” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 2 (3): 1–14. doi:10.11120/elss.2010.02030012.

- Nolan, H.A., and L. Roberts. 2021. “Medical Educators’ Views and Experiences of Trigger Warnings in Teaching Sensitive Content.” Medical Education 55 (11): 1273–1283. doi:10.1111/medu.14576.

- Nowell, L.S., J.M. Norris, D.E. White, and N.J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 1609406917733847. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847.

- Pilcher, K. 2017. “Politicising the ‘Personal’: The Resistant Potential of Creative Pedagogies in Teaching and Learning ‘Sensitive’ Issues.” Teaching in Higher Education 22 (8): 975–990. doi:10.1080/13562517.2017.1332030.

- Sandbrook, D. 2017. “How Did so Many of Today’s Students Turn into Snowflakes … Mail Online.” https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4824866/How-did-today-s-students-turn-snowflakes.html

- Sanson, M., D. Strange, and M. Garry. 2019. “Trigger Warnings are Trivially Helpful at Reducing Negative Affect, Intrusive Thoughts, and Avoidance.” Clinical Psychological Science 7 (4): 778–793. doi:10.1177/2167702619827018.

- Simon, R.I. 2011. “A Shock to Thought: Curatorial Judgment and the Public Exhibition of ‘Difficult Knowledge’.” Memory Studies 4 (4): 432–449. doi:10.1177/1750698011398170.

- Storla, K. 2017. “Beyond Trigger Warnings: Handling Traumatic Topics in the Classroom.” In Trigger Warnings: History, Theory, Context, edited by E.J.M. Knox, 190–199. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Wyatt, W. 2016. “The Ethics of Trigger Warnings.” Teaching Ethics 16 (1): 17–35. doi:10.5840/tej201632427.