ABSTRACT

We analyse an institutional curriculum change initiative from the perspective of academics in a physics department to identify the barriers faced when curriculum change is used as a process to increase equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI). We explore what curriculum means in physics, how power relationships within the university affect the response to top-down change, and ultimately who has control over the curriculum. We find that the different conceptualisations of curriculum in physics compared to educational research mean that a directed top-down approach stalls when concepts that fall outside of the physics curriculum, such as EDI, are introduced. Nevertheless, initiatives that are in response to EDI concerns that would be considered to be curriculum change from an educational research perspective are enacted within the department on a localised scale. Understanding the different conceptualisations of curriculum and how they interact to support or hinder change should help guide future institutional change efforts.

Introduction

Systems within universities can perpetuate the inequities present in society (Kromydas Citation2017). Hence, there has been significant pressure for the higher-education sector to enact policies with the aim of addressing those inequities that can develop during an undergraduate degree course (Office for Students Citation2021) and potentially have an impact on reducing the inequities across society. Such change, in the form of policy, necessarily is disseminated from the senior management and leadership team of an institution. These composers and presenters of policy are who we refer to using hierarchical terminology as being at the ‘top’. Analysis of this top-down approach to cultural change is of particular interest, as many higher-education institutions have adopted specific equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) policies in the past decade (Claeys-Kulik et al. Citation2019; Tamtik and Guenter Citation2019). While the creation of well-thought-out policy documents is an important process, it is only part of the story. How those policies are enacted and what change happens is the ultimate measure of policy effectiveness (Ball, Maguire, and Braun Citation2011).

One policy adaptation that has become prominent is diversifying the curriculum (Shay Citation2016), with curriculum being defined broadly by various authors to include content, sequencing, pacing, and assessment (Bernstein Citation2000), and the dimensions of knowing, acting, and being within a discipline (Barnett and Coate Citation2005). As part of a wider, longitudinal study looking at a process of curriculum and cultural change at a research-intensive university in the United Kingdom, we conducted interviews within one discipline with the aim to understand the dynamics at play during the curriculum change process. These dynamics are important to shed light on, as top-down curriculum change is challenging (Lachiver and Tardif Citation2002; Honkimäki et al. Citation2021).

The change process consisted of four ‘pillars’: Assessment Reform; Active Learning; Diversity and Inclusion; and Digital and Technology Enhanced Learning. A linguistic ethnographic analysis of documents related to this change process (e.g. programme specifications) highlighted that departmental interpretations and implementations of the Diversity and Inclusion pillar varied considerably (Kandiko Howson and Kingsbury Citation2021). This work is a natural extension where we look beyond the paperwork to understand the impact of the curriculum review process on the ‘ground’, with the purpose to explore how the Diversity and Inclusion pillar materialised in the curriculum documents. Therefore, we focus on one department within the university: the Department of Physics. Physics is a particularly interesting discipline to study because of its well-known representation problem: in the UK in the 2017–18 academic year, 24% of undergraduate physics students were female and less than 1% were black (Institute of Physics Citation2018). We position our research question within this perspective and ask: what are the barriers to progressing an EDI agenda from the top?

The top-down process emanated from the publication of an institutional Learning and Teaching Strategy (LTS) (Buitendijk Citation2017), which was developed with input from stakeholders across the university. The LTS introduced the four pillars and envisioned a process of institution-wide curriculum review followed by implementing the pillars into the curriculum and embedding them into the institutional culture. Therefore, the curriculum was to play a central role in this process (Luckett and Shay Citation2020). We draw on the work of Barnett and Coate (Citation2005) in the analysis to frame the discussion around curriculum, using the three dimensions of knowing, acting, and being. Curricula in different disciplines are distinguished through the size and overlap between these three dimensions. For ‘science and technology’ disciplines, Barnett and Coate (Citation2005) characterised the knowing dimension as the largest, reflecting the content-rich nature of these curricula. The knowing dimension has a large overlap with the smaller acting dimension, which reflects the actions that students take to engage with the curriculum (e.g. performing measurements in laboratories). They present the being dimension as just touching the knowing dimension, but do not provide a reason for this except that the knowing dimension is ‘overcrowded’. The being dimension is the aspect of curriculum that develops students’ abilities in self-reflection and self-criticism, such that they are able to understand their own self within the context of the discipline.

In other curriculum change efforts the development and adaptation of the being dimension of the curriculum has been associated with increasing equity within disciplines (Shay Citation2015; Gay Citation2002; Ladson-Billings Citation1995), and is promoted by Barnett and Coate (Citation2005) as a way to prepare students for a ‘changing world’. In contrast to the above discourse on curriculum in the educational field, the word curriculum in physics seems to be used in a narrower sense focusing purely on content. Physics degrees in the UK and Ireland are accredited by the Institute of Physics (IOP) who provide guidance on what should be included in an undergraduate programme – the ‘Core of Physics’, ‘Physics skills’ and ‘Transferable skills’. The way curriculum is discussed in the accreditation documentation illustrates this different use of languageFootnote1:

The Core of Physics contains a set of headings under which appear topics that should be covered in an accredited physics degree. As such, it should not be read as a syllabus and a traditional arrangement of the curriculum is not a requirement, nor is a traditional teaching approach. (Institute of Physics Citation2011, pg. 7)

The distinction between what is taught, ‘the curriculum’, and how it is taught, the ‘teaching approach’ or pedagogy, is clear. This is not to say that other broader areas of curriculum, such as sequencing, pacing, and evaluation (Shay Citation2015), or acting and being a physicist (Barnett and Coate Citation2005), are not considered when designing a course or teaching in a physics setting, just that some of those aspects may be considered by physicists as pedagogy rather than curriculum. This signals an orientation in the curriculum towards knowledge (what and how you know) versus the knower (who you are) (Maton Citation2013). Furthermore, it might be that this different use of language is what is being reflected in the curriculum analysis of educational researchers, because much of the ‘being’ dimension in physics remains part of the hidden curriculum, or even outside of the curriculum altogether, highlighting the challenge of translating between different communities of practice (Irving and Sayre Citation2015). Indeed, only recently has discussion of the curriculum taken place within the field of Physics Education Research (Harrer, Sayre, and Elliott Citation2020).

Methods

There were two methodological approaches for this study. The first was a set of semi-structured interviews; the second, a coding analysis of departmental-specific, module-level curriculum outcome documents. Ethical approval was obtained through the Imperial College London Education Ethics Review Process; approval number EERP-1819-050.

Ten interviews were carried out via Microsoft Teams during June and July 2021. Participants were recruited through internal mailing lists, announcements at staff meetings, and direct emails to persons known to be involved with teaching undergraduate courses. These included academic faculty, ‘learning and teaching’ staff, and Ph.D. students. Interviewees were provided with an information sheet and completed a consent form prior to the interviews. They were additionally reminded of their right to withdraw at the beginning and end of the interview. The interviews were recorded and auto-transcribed. Each transcription was checked manually and corrected. Of the ten interviewees, three were Ph.D. students and seven were academic or ‘learning and teaching’ staff. We focus on the responses of staff members in this work as they were more involved with the curriculum review process. We refer to both the academic and ‘learning and teaching’ staff as ‘academic staff’, as their education roles are similar. We have used pseudonyms to avoid identification of individuals. We did not collect demographic data because of the small number of participants. However, for context, we provide departmental-level demographics. In 2021, 11% of staff and 16% of Ph.D. students identified as women; 85% of staff identified as White, with 10% not disclosing, and 5% identifying as Black, Asian, or Minority Ethnic (BAME), while 74% of Ph.D. students identified as White and 26% identified as BAME or not stated.Footnote2

The interviews were semi-structured and included an initial phase where the participants were asked to draw a concept map of ‘my role at Imperial’. The interview then covered three main sections, which formed part of the wider project that this work sits within: (1) career plans, hopes, strategies, barriers, (2) indicators of prestige, and (3) learning and teaching. During each interview, when appropriate, questions were asked about the curriculum review process as well as equity,Footnote3 diversity, and inclusion in the context of the Department of Physics.

The analysis of the interview transcripts was guided by the theoretical considerations discussed in the introduction, while also maintaining an exploratory nature. Thus, the analysis involved applying a priori codes as well as allowing for emergent codes to be created to capture unforeseen themes. The a priori codes were mainly based on Bernstein’s concept of the curriculum (Bernstein Citation2000) as articulated by Shay (Citation2015), while also separating the ideas of curriculum from pedagogy. We also included labelling codes for when EDI and the curriculum review were mentioned. Key emergent codes were ‘control’, referring to the idea of who has control of the curriculum, ‘internal identity’ referring to factors within the physics department (e.g. colleagues, curriculum) that were identified to be important aspects of being a physicist, as well as ‘relationships’ between staff within the department and ‘power’ relationships outside the department.

In addition to the interview study, we performed a coding analysis of module-level curriculum documents for the academic year 2020–2021 following the curriculum review process that had been rolled out at that point for the first two years of the undergraduate course. We developed codes based on the IOP accreditation documents to classify the learning outcomes for each module in the course. We grouped each of these codes into three groups representing the knowing, acting, and being dimensions of the curriculum (Barnett and Coate Citation2005). The purpose of this activity was to understand to what extent the curriculum documents represented the ‘science and technology’ curriculum as described by Barnett and Coate (Citation2005).

Results

We present results from the three key themes that arose from the interview analysis: the perception of the curriculum in physics; power structures within the university; and who has control of the curriculum.

Perception of the curriculum in physics

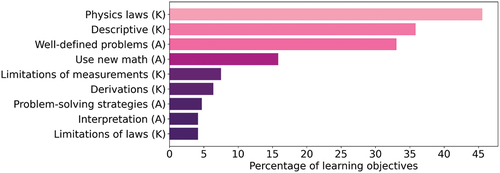

We first demonstrate that the current curriculum on paper reflects the description of science and technology disciplines reported by Barnett and Coate (Citation2005). A coding analysis (see Methods) of the 360 individual learning outcomes from specifications of 45 modules in the academic year 2020–21 shows that the most common codes correspond to the knowing dimension of the curriculum and second most to the acting dimension (). Codes that represent the being dimension – ‘Appreciate multiple perspectives’ (1.4% of all codes) and ‘Reflection’ (0.3% of all codes) – occur rarely in learning outcomes.

Figure 1. Occurrence of codes in the module specifications for the physics course for the academic year 2020–21, given as the percentage of learning outcomes with that code. The total number of learning outcomes was 360. The total number of applied codes was 703. Abbreviations: K – knowing; A – acting; B – being.

In the interviews, we find that the results of the previous studies on the curriculum of science and technology disciplines described in the Introduction are replicated. That is, the curriculum is dominated by content and hence represents a weighting towards the knowing dimension. As our questioning was focused around the curriculum review process, the importance of the curriculum as content became evident as most of the discussion was around what topics were being covered, for example one member of academic staff said:

I had to remove material, so they’re learning less than they used to learn. Hilary

Here, Hilary is discussing how the reorganisation of the modules under the curriculum review and the introduction of group problem-solving sessions impacted negatively on the quantity of content in the course. While content coverage is considered paramount, during one interview, when reflecting on what is in the curriculum, another academic revealed the ambiguous nature of the decision-making process behind what content is to be included in the curriculum

I’ve never actually been in a room where there’s been a discussion about: what do we think a physicist should know? Andrea

We cannot say whether Andrea’s description of knowledge goes beyond content, however, one can see that the curriculum has not been open to debate. Indeed there is an implicit understanding of what constitutes a physics degree, or as Becher and Trowler (Citation2001, pg. 187) put it: a ‘collective kinship, a mutuality of interests, a shared intellectual style’ between physicists. We can see this as the being dimension of the curriculum embedded and hidden within the knowing dimension (rather than tangential to it as proposed by Barnett and Coate (Citation2005)). This embedding poses challenges for the idea of becoming a physicist, as to which comes first – the knowledge or the knower? (Maton Citation2013)

How then does EDI fit within a content focused curriculum? As the curriculum is seen in a narrow sense, then introducing EDI awareness can seem a forced imposition of external ‘non-physics’ when trying to make content that would help students be conscious of and address EDI issues. The content of study in physics is, by definition, abstracted as much as possible from the human nature of being,

The basic physics problems are basic physics problems … They kind of are what they are. Hilary

Nevertheless, some academics have found space to broaden what is included in the curriculum in action which directly addresses ‘ways of being a physicist’.

I make a point of talking about a wide range of individuals with different sorts of identities … I mean you kind of count these individually non-white, male people but there is some effort to give examples of different ways of being a physicist, both in personality and identity and origin. Blake

This type of content is not included in the written curriculum material and is not directly assessed, potentially underlining that it is not to be considered by students as part of the physics canon. The perspective of one Ph.D. student interviewed highlights how such engagement of EDI efforts are perceived by some:

Long story short, no I don’t have any strong opinions about [EDI]. It’s not a programme that’s pitched at me, you know.

What the Ph.D. student says brings out an aspect of the hidden curriculum, in that they do not appreciate the need to have specific programmes aimed at developing their identity within physics; indeed, this reinforces the idea that the narrowly defined knowing dimension of the curriculum is all that is required to become a physicist. We discuss more about the role of individual actions and the impact of who controls the curriculum on implementing top-down change in the third part of the results.

Power structures within the university

I think there’s this tension between the department and the central College. Mo

A top-down approach to reform necessarily involves the hierarchical structures of a university. To understand what the barriers are to such an approach we first need to understand the context and relationships between the different parts of the hierarchy. The university in our study has a Senior Leadership Team which, through appropriate committees, provides strategic direction for Faculties. These Faculties retain significant autonomy and funding, making the institution less usual than others where more power is concentrated in the ‘top’. Within the Faculties are the Departments, so the Department of Physics is within the Faculty of Natural Sciences. From now on, we refer to these layers of hierarchy outside of the Department of Physics as ‘the College’, which was a common reference from the interviewees.

The quote from Mo at the beginning of this section gives direction to explore the reaction to the curriculum review process from the department. Indeed, there appears to be scepticism as to the motivations behind any changes

The further away you get from the department, the clearer it is that priorities are different. And, what we know on the ground is a sensible thing to do we’re often told the opposite from above. Andrea

It seems that the nature of this relationship has been sustained for a long enough period of time such that the department has developed coping strategies:

The kind of top down, slightly dictatorial aspect of it [I like] rather less so, but the department mostly shields us from that, so that’s good. Blake

The positioning of the department in opposition to the College was a common theme through the interviews and could be argued to contribute towards the identity of this department, and may even be fuelled by the department as a way of maintaining disciplinary autonomy. We see that the trust placed in the department by academics to protect them from overburdening workload is appreciated. This then means that it is in the department’s interest to filter the work down to the minimum required, which, interestingly, is aligned with the LTS that included specific aims to reduce academic and student workload.

One of the most striking results from the interviews was that all academics interviewed did not know that during the curriculum review the intention was for EDI to be an integral part of the process:

I’m aware of EDI within College and it’s very welcome … but I was not aware of [the EDI pillar] within the curriculum review, no. Hilary

From my point of view, [EDI] hasn’t come out of the department strategy [for the curriculum review]. Adrian

Wow, yeah … I didn’t appreciate [EDI in the curriculum review] to be honest. Blake

Evidently, the message that EDI was to be included in the curriculum review was filtered out by the time it had reached these academics – despite it being explicit in the LTS, in the curriculum review documentation, and in the support provided for the implementation. Yet we do see that academics were ‘aware of EDI within College’, but the link to the curriculum review was fractured. We now argue that rather than this link breaking, there simply was no connection within the concept of the curriculum in physics onto which a link could have been made.

In the narrow framing of the curriculum in physics, there is general uncertainty as what implementing EDI into the curriculum looks like:

I haven’t taken [EDI] into account in my review, but I don’t see how I can to be honest. Nikita

Another example relates to a previous case where talking about historical figures in lectures is used as a way to implement EDI; however in this context a different academic found that the relevant figures for their course were

… almost universally white European, and there wasn’t a lot I could do about it. Hilary

This approach resonates with the idea of curriculum as content, as we see EDI being approached by asking the question: what can I put in my lectures? The uncertainty of what EDI means in the curriculum in physics is one reason why the link between EDI and the curriculum review did not form. Other aspects of the curriculum review that lent themselves to more definitive actions, such as reorganising module and programme specifications and introducing aspects of active learning, meant that these were prioritised. Indeed, the focus on active learning was seen purely as a pedagogic approach separate from the content:

Flipping [the classroom] for the active learning, but I think those are the only EDI elements that have kind of come into that. Blake

In the interview with Blake, the idea of using active learning to address EDI issues was clearly present, yet it was not associated with the curriculum review, and rather seen as part of the wider changes brought about by the LTS generally.

Within the power structure that exists between the Department of Physics and the College, as described at the beginning of this section, the focus on outcomes that are tangible in the department’s implementation of the curriculum review is understandable. In the concept of curriculum as content, introducing EDI into the curriculum can be seen as introducing not only more content but ‘non-physics’ content, which results in a conflict. This separateness of EDI from the discipline is supported by institutional structures, as the university EDI Centre is located outside of the departmental and faculty structures. These factors, that place EDI outside of the curriculum in physics, contribute to the outcome that EDI was neglected in the top-down approach, as translated by the department, when enacting curriculum change.

The performative response of the department to the curriculum review on standardising modules can be considered as the option that minimised the work needed to satisfy the external requirements. However, through our above argument, we could also view this performative response as the only ‘understandable’ output, in the context of curriculum in physics, that was then passed ‘down’ to those operationalising the change.

Importantly, from the data we have and as described at the beginning of this section, we cannot say whether the filtering of the messaging from the College occurred at the Faculty or the Departmental level. From Kandiko Howson and Kingsbury (Citation2021), we see that the Department of Physics was not the only department where the EDI aspects of the curriculum review were lost, suggesting that other departments within the university may have similar relationships with the College and the conceptualisation of the curriculum. It is also impossible to say whether any ‘filtering’ or ‘managing’ of the message at faculty or departmental level was deliberate and strategic or whether it was a passive result of the process as transmitted through hierarchical structures.

Control of the curriculum

It is evident from our discussion so far that a top-down approach to incorporating EDI into the physics curriculum faced significant barriers and that it is the discipline, embodied in the department, that has control over the curriculum. We now explore how that control manifests itself, the impact that control has on the curriculum, and on EDI efforts.

Thinking of the curriculum as content, there is a sense that lecturers have little control of it, as the ‘Core of Physics’ is given by the IOP. As we have discussed already, there is a tacit agreement between academics of what should be in a physics course, which is reinforced through the structures that decide who lectures the prestigious courses:

With, say, the big core lecture courses … they will only give you those if they think that you’re a safe pair of hands. Adrian

In this sense ‘safe’ implies both experienced and aligned with traditional established processes and practice. As a result of this confidence in the lecturer, once a course has been allocated, they then have a large amount of freedom as to how they approach a course, which can lead to a:

Disconnect between what the documentation says and how things are actually done on the ground. Adrian

Therefore, the control of the curriculum is really in the hands of the individual lecturers (albeit with the implicit pressures of expectation from within the department and also the IOP). This can cause tension when change is seen as being imposed from the top:

… the lecturer thinks this is … my baby, … no one else has a valid input to this. Adrian

The above quotes from Adrian present the control by each lecturer in a somewhat negative light. However, the academic freedom of such a system is seen by many positively, and there are benefits to such a system. Exposing students to a variety of teaching approaches and personal interpretations of the narrowly defined ‘knowing dimension’ of the curriculum can be argued to be beneficial to help students develop a robustness that prepares them to engage with contexts after university. It also allows lecturers to show their passion and excitement for the subject and to make explicit links between pedagogy and the cutting edge of departmental disciplinary research:

One of the nice things about lecturing in person is you can … talk about your own research. Hilary

Similarly, it allows lecturers who value EDI efforts to bring those into the way they teach the course, as we found earlier that Blake did by exploring the ‘different ways of being a physicist’. They went on to reflect that:

It’s more down to individual lecturer’s choice than any systematic discussion of [EDI in the course]. Blake

Therefore, this freedom allows for change to happen within the system, even if the pace of that change is slow and less immediately externally visible. The absence of a ‘systematic discussion’ of EDI does not mean that EDI is not discussed within the department. Indeed, academics are thinking about and acting on EDI issues, however, as they do not operate within the discourse of educational research, the language used to articulate what they are doing does not immediately relate to the themes of EDI. In the interview with Alex, they were recounting the changes they had made to their course and why they had made those changes, when they made the following realisation:

I don’t think it was presented as an aspect of EDI, but I think with hindsight … it is an EDI thing … it may not have been anybody saying ‘Ah, we need to do this for equality and inclusion reasons’. It was things like saying, well, we’ve got people who’ve got very different backgrounds, some of them have never [done this] before. Alex

This is one example of how EDI can influence the curriculum in the sense of Barnett and Coate (Citation2005). Here Alex was directly using the ‘being’ dimension of the curriculum when thinking about who the learners are and their background. This example highlights how the being dimension informs and justifies concrete choices about sequencing and assessment in the course. In illustrating an authentic interpretation of the EDI agenda, it also highlights how these processes are challenging to monitor as it is less attributable to strategic directives.

Having noted that individual lecturers have a high degree of control over the curriculum as implemented through pedagogy, it is interesting to ask whether the College has any control of the curriculum. As we have seen, direct action, such as implementing the curriculum review, is sometimes limited by the performative responses by some departments. However, by setting policy directions and intentions, through the LTS, and using other channels outside the hierarchical structure of the institution, change can still happen:

Within the college environment, there’s a lot of messaging about … certain equality, diversity, and inclusion issues … it makes me … want to know about these things and so build them into how I design things. Adrian

This is not control from the top in a traditional, directed sense, which, as we have seen, does not always work to produce the desired effects. Rather, it is controlling what can be controlled by the College, which is the atmosphere and ethos of the university. By producing and disseminating messages saying that EDI initiatives are valued by the institution it encourages those members of staff who are interested in trying new things and adapting the way they teach to bring in best practices related to EDI. In effect, through this messaging, the College is indicating strategic direction and intent thus empowering individuals to act on the ground.

One major challenge faced by academics who did want to bring aspects of EDI into the curriculum was time: first to understand what that means for their course, and second to implement that change:

There is not enough time to think, and there’s too much reactive stuff. Nikita

This represents a lack of control by the academics of their time to do what they think is best for their students. It is ultimately the department that controls academics’ time. Additional funding associated with the LTS has been a specific intervention from the College to provide some of the necessary time and space to empower change. Indeed, during the curriculum review, this aspect of control was deployed to support efforts:

A bunch of money got thrown at me to buy me out of some other teaching time … I was able to take a step back and think how this is going to work. Andrea

However, efforts such as embedding EDI can be positioned by the department as a ‘top-down’ imposition of staff time. To circumvent this, the College used funding specifically linked to desired elements of change, recognising that change takes time and effort. This was done with the intention that the top-down message would result in locally derived authentic change. However, the highly localised nature of this funding meant that most academics did not immediately benefit from it. It may seem counter-intuitive that the College may exert control over the curriculum by facilitating academics to have more freedom to shape the curriculum and hence more localised control. This, however, highlights that curriculum change does not have to be a zero-sum game.

Discussion and conclusion

We propose that one underlying barrier to top-down curriculum change in the department studied was a difference in the concept of curriculum between the Department of Physics and the College. This difference is shown in , contrasting the curriculum structure described by Barnett and Coate (Citation2005), with the results of this work. This difference is reflected in the power relationships at play during the change process as well as to the challenge of making change on the ground through who has control of the curriculum, both aspects which we expand upon here.

Figure 2. Concepts of curriculum from (a) the structure of the curriculum in science and technology disciplines as described in Barnett and Coate (Citation2005) and (b) developed in this work from a department of physics.

We emphasise that both views of the curriculum in are legitimate. Indeed, the view of the curriculum as content has practical value and cultural authenticity within the discipline when determining what is taught and, as a consequence, helps to define the identity of a physicist. Therefore, it is important not to assert that one view should replace the other, rather to enable people who come from each perspective to translate into and understand the other.

The link between curriculum and pedagogy in ) implies that pedagogy is not entirely separate from the curriculum (the content). The content-rich nature of disciplines, such as physics, has been seen to influence academics’ self-efficacy in teaching and pedagogical decisions (Lindblom-Ylänne et al. Citation2006). We have seen in this work that pedagogical change for EDI reasons (e.g. the introduction of active learning) was adopted within the department, while curriculum change related to EDI as part of the formal review process was not, evidenced by the written curriculum.

The student, as part of teaching and learning in ), being positioned at the end of the chain is connected to the curriculum, but does not influence it. This resonates with the tangential nature of the being dimension in ) and a focus on transmitting knowledge over developing the student (Lueddeke Citation2003). And while pedagogical transformations that include aspects of active learning may introduce a feedback loop between the student and the pedagogy, there is still a separation from the curriculum.

Considering the change process itself, the power relationship between the Department of Physics and the College can be seen as the discipline defining itself in relation to external pressures (Bernstein Citation2000). The tight relationship between physics identity and content knowledge means that, from a perspective that curriculum is content, a review of the curriculum could be perceived as an attempt to change what it means to be a physicist. This is a mechanism that reduces the incentive to engage with the change process. Furthermore, from this perspective, when asked to include aspects of EDI into the curriculum, this may be conceived as a need to add not just more content but more ‘non-physics’ content. With the constraint of finite contact time, this is seen as resulting in the removal of traditional and valued physics content.

Control of the content of the curriculum, at least in the first two years of the undergraduate degree in physics, is largely determined by the expectations of the physics community exemplified in the IOP’s Core of Physics. Therefore, the control of the curriculum that an individual academic has is mainly in the pedagogical realm. Hence, when asked to introduce new pedagogy, such as those involved with active learning, this is something that can be recognised in relation to, but separate from the defined written curriculum. However, when asked to adapt the curriculum for EDI considerations, the idea of the student (the knower or self) within the curriculum simply does not exist. Importantly, this is not to say that those teaching within physics do not consider the student when they are teaching, rather that the student is thought of as separate from the curriculum.

We have seen in our results that the control individual academics have over their courses can lead to changes that address identified unfairness in the courses. From the interviewees’ perspectives, these changes were not motivated by a specific EDI agenda but rather by a general desire to improve the experience of students. Such changes did happen within the framing of the top-down strategy and making time for those changes to occur was by explicit design in the way resources were allocated by the top-down college process to circumnavigate the hierarchical structures of the university. Thus, there was some success in the process as designed to facilitate authentic interpretations of the top-down intent.

However, academics work within the structures of the university and so the change instigated by one academic, even if empowered from above, may be limited to their locality. The top-down approach needs to work in concert with the people on the ground to identify where systemic barriers exist and then take action to remove those barriers (Luckett and Shay Citation2020). To start that change it is important that each party understands the disciplinary context of the others, so that intent and outcomes do not get lost in translation. One possible approach to this is through Departmental Action Teams (Corbo et al. Citation2015), or through initiatives such as the Strengthening Learning Communities projectFootnote4 in the Department of Physics at Imperial College London that MFJF and CKH are involved with. In these approaches, groups of people from within a discipline and supported by educational experts work together to identify where change is needed and then act to make change happen. Such initiatives to facilitate evidence-based change in local disciplinary cultures, which may be centrally funded, can appear to be locally generated. The lack of perceived imposition can be empowering in local contexts. This may make the ‘top down’ appear less effective, but, we note, in the case of the Imperial College LTS this was the intention of the strategic delivery plan to facilitate authentic culture change within the departments.

In conclusion, we have found that social justice from the top does trickle down, with the emphasis being on trickle. We have seen that due to the different conceptualisation of the curriculum in physics compared to educational research, incorporating EDI aspects into the curriculum in physics stalled. The top-down messaging on the value of EDI nevertheless percolated through the institution and empowered some individual academics to enact changes to affect social justice. We have included one example of a case where the change goes beyond EDI as content (see the quote from Alex in the Control of the Curriculum part of the results), which we highlight to help guide future curriculum change initiatives.

Limitations of this study

By the nature of this work, we are limited to interpreting the results in the context of the Department of Physics at one, research-intensive institution in the United Kingdom. Most notably, the results relating to the power structures of the university are very specific to the local context. However, as our results support previous findings about the role and views of the curriculum in physics, we have some confidence that they may be able to inform change processes in physics and other similar departments at other institutions.

Our results mainly come from the interviews with seven academic staff, representing a sampling rate of 6% from all academic (including learning and teaching) staff in the Department of Physics. We recognise that there is likely a bias towards staff who have a stronger interest in the teaching side of their roles compared to fellow research-focused academics. This, however, makes one of the main results that they were not aware of the Diversity and Inclusion pillar of the LTS and its role in the curriculum review even more striking.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jessie Durk for second coding the module specifications to establish inter-rater reliability. MF was funded as part of the Strengthening Learning Communities project through the Imperial College London Pedagogy Transformation Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The accreditation document referred to here corresponds to an accreditation scheme that will be replaced with a new, less prescriptive scheme from the academic year 2022–2023.

2. These categories were collapsed because the numbers separately could lead to individuals being identified.

3. In the interviews the word equity was used by the interviewer. The word equality was used in the LTS (Buitendijk Citation2017), and most interviewees used this word in their responses.

References

- Ball, Stephen J, Meg Maguire, and , and Annette Braun. 2011. How Schools Do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary Schools. London: Routledge.

- Barnett, Ronald, and Kelly Coate. 2005. Engaging the Curriculum in Higher Education. Maidenhead: Open University Press, McGraw-Hill Education.

- Becher, Tony, and Paul Trowler. 2001. Academic Tribes and Territories. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

- Bernstein, Basil. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control, and Identity. Lanham (MD): Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Buitendijk, Simone. 2017. “Innovative Teaching for World Class Learning. Learning and Teaching Strategy.” https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/about/leadership-and-strategy/vp-education/public/LearningTeachingStrategy.pdf

- Claeys-Kulik, Anna-Lena, Thomas Ekman Jørgensen, and Stöber Henriette. 2019. Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in European Higher Education Institutions: Results from the INVITED Project. Brussels: European University Association.

- Corbo, Joel C, Daniel L Reinholz, Melissa H Dancy, and Noah Finkelstein. 2015. “Departmental Action Teams: Empowering Faculty to Make Sustainable Change.” In 2015 Physics Education Research Conference Proceedings, American Association of Physics Teachers. College Park, MD, 91–94. doi:10.1119/perc.2015.pr.018.

- Gay, Geneva. 2002. “Preparing for Culturally Responsive Teaching.” Journal of Teacher Education 53 (2): 106–116. doi:10.1177/0022487102053002003.

- Harrer, Benedikt W., Eleanor C. Sayre, and Leslie Atkins Elliott. 2020. “Editorial: Focused Collection: Curriculum Development: Theory into Design.” Physical Review Physics Education Research 16: 020002. doi:10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.16.020002.

- Honkimäki, Sanna, Päivikki Jääskelä, Joachim Kratochvil, and , and Tynjälä Päivi. 2021. “University-wide, top-down curriculum reform at a Finnish university: perceptions of the academic staff.” European Journal of Higher Education 12.2: 153–170. doi:10.1080/21568235.2021.1906727.

- Institute of Physics. 2011. “The Physics Degree.” https://www.iop.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/the-physics-degree.pdf

- Institute of Physics. 2018. “Students in UK Physics Departments.” https://www.iop.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/Student-characteristics-2017-18.pdf

- Irving, Paul W., and Eleanor C. Sayre. 2015. “Becoming a Physicist: The Roles of Research, Mindsets, and Milestones in upper-division Student Perceptions.” Physical Review Special Topics - Physics Education Research 11: 020120. doi:10.1103/PhysRevSTPER.11.020120.

- Kandiko Howson, Camille, and Martyn Kingsbury. 2021. “Curriculum Change as Transformational Learning.” Teaching in Higher Education 1–20. doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1940923.

- Kromydas, Theocharis. 2017. “Rethinking Higher Education and Its Relationship with Social Inequalities: Past Knowledge, Present State and Future Potential.” Palgrave Communications 3 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1057/s41599-017-0001-8.

- Lachiver, Gérard, and Jacques Tardif. 2002. “Fostering and Managing Curriculum Change and Innovation.” In 32nd Annual Frontiers in Education. Vol. 2, F2F–F2F. Boston, MA: IEEE. doi:10.1109/FIE.2002.1158168.

- Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 1995. “Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy.” American Educational Research Journal 32 (3): 465–491. doi:10.3102/00028312032003465.

- Lindblom-Ylänne, Sari, Keith Trigwell, Anne Nevgi, and Paul Ashwin. 2006. “How Approaches to Teaching are Affected by Discipline and Teaching Context.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (3): 285–298. doi:10.1080/03075070600680539.

- Luckett, Kathy, and Suellen Shay. 2020. “Reframing the Curriculum: A Transformative Approach.” Critical Studies in Education 61 (1): 50–65. doi:10.1080/17508487.2017.1356341.

- Lueddeke, George R. 2003. “Professionalising Teaching Practice in Higher Education: A Study of Disciplinary Variation and ’teaching-scholarship’.” Studies in Higher Education 28 (2): 213–228. doi:10.1080/0307507032000058082.

- Maton, Karl. 2013. Knowledge and Knowers: Towards a Realist Sociology of Education. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Office for Students. 2021. “Participation Performance Measures.” https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/about/measures-of-our-success/participation-performance-measures/

- Shay, Suellen. 2015. “Curriculum Reform in Higher Education: A Contested Space.” Teaching in Higher Education 20 (4): 431–441. doi:10.1080/13562517.2015.1023287.

- Shay, Suellen. 2016. “Decolonising the Curriculum: It’s Time for a Strategy.” The Conversation, 13.

- Tamtik, Merli, and Melissa Guenter. 2019. “Policy Analysis of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Strategies in Canadian Universities – How Far Have We Come?” Canadian Journal of Higher Education/Revue Canadienne D’enseignement Supérieur 49 (3): 41–56.