ABSTRACT

Learner-teacher partnerships (L-TPs) increasingly feature in student engagement research in further and higher education (FHE). This flourishing literature raises important questions about such partnerships, for example, what is their purpose? what roles do partners play, who leads in a partnership and how? Various purposes and roles have been identified and are generally accepted. These include that learners and teachers working as partners make equal but not necessarily the same contributions to the partnership; that there is open dialogue between partners, collective decision-making; and consensual action. What is missing is an overarching planning framework that addresses all these questions. In this article, we sketch such a framework in the expectation that it will help teacher and student partners make conscious and consensual decisions about how specific partnerships in curriculum, pedagogy and evaluation will work. The paper first outlines distributive leadership as a heuristic device to provide a conceptual foundation for the framework. It then develops the planning framework using the heuristic tool to explore purposes, student roles, leadership and levels of influence in partnerships.

Introduction

Student engagement is recognised as key to student success (Kuh et al. Citation2008; Kift Citation2015; Thomas Citation2012). Frequently discussed in further and higher education (FHE) learning and teaching research, engagement is a complex construct viewed from a variety of perspectives (Kahu Citation2013). One draws on various psychological theories (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, and Paris Citation2004); a second offers a psycho-social perspective (Kahn Citation2014); a third has socio-cultural roots (Thomas Citation2012); a fourth sees engagement as a holistic, life-wide, and dynamic socio-ecological process (Barnett, Citation2011; Lawson and Lawson Citation2013); a fifth considers engagement as socio-political with students understood as active citizens (Zepke Citation2017). While each perspective offers its own views on engagement, points of consensus emerge. For example, shared by all perspectives are assumptions that engagement requires both student agency and supportive institutional structures, feelings of belonging, motivation and collaborative and reciprocal relationships. One strongly emergent engagement strand sharing these assumptions has numerous labels, for example students as partners (SaP), pedagogical partnerships, co-created learning and teaching (Bovill Citation2020). These labels suggest an approach to student engagement that is collaborative and reciprocal, enabling learners and teachers in FHE to contribute equally but not necessarily in the same way to curriculum and pedagogic planning, implementation, and evaluation (Cook-Sather, C. Bovill, and Felten Citation2014). ‘Learning and Teaching Partnerships’ (L-TPs) is the label used in this article to capture this meaning.

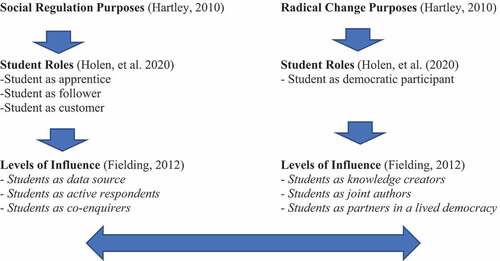

Like engagement research, the L-TP strand is conceptualised in different ways. M. Healey, A. Flint, and K. Harrington (Citation2014), for example, recognised four distinct L-TP activities (i): learning, teaching, and assessment (ii); curriculum design and evaluation (iii); collaborative research and (iv) partnerships in governance. Such activities are guided by various principles, roles, and partnership practices. Matthews (Citation2017) suggests that five principles underpin L-TPs: inclusive relationships: power sharing; uncertain results, ethical practice; and transformation. How such principles work in practice, who leads partnerships and how is also approached from a variety of perspectives. For example, Holen et al. (Citation2020) identify four student partnership roles. In a student as apprentice role, students learn from expert teachers. In a student as follower role, students embrace their teachers’ practices. As democratic participant a student’s role can be equal to that of teachers (Cook-Sather, C. Bovill, and Felten Citation2014). In a student as customer role, students are purchasers of qualifications for employment. By investigating students’ roles in partnerships, Holen et al. also identify leadership roles in L-TPs. Only in democratic participant can power be seen as shared; in the other roles teachers are mostly in charge. Fielding (Citation2012) captured this variability in identifying different practice patterns in partnerships. He identifies students as data source, active respondents, co-enquirers, knowledge creators, joint authors, and partners in a lived democracy.

Matthews (Citation2017) principles also apply to distributive leadership; a way of thinking that rejects that leaders are the sole or major decision-makers in groups. Instead, leaders are interdependent members of a group working together to achieve common goals using the combined skills and attributes of group members (Gronn Citation2002). With distributive leadership and L-TP sharing principles, the paper uses distributive leadership as a heuristic foundation for a conceptual framework to serve as a planning, discussion and self-monitoring tool for learners and teachers in L-TPs. The way the tool is used depends on the purposes of the partnership; the roles students and teachers play in it; and the degree of power sharing that occurs. Accordingly, the framework draws from three models. The first, based on Burrell and Morgan (Citation1979) model of sociological paradigms, was changed by Hartley (Citation2010) to consider research into distributed leadership in education. I extend Hartley’s reframing to include research into the purposes of distributive leadership in pedagogical partnerships. This extension suggests that Hartley’s reframed paradigms identify purposes of partnerships, whether they lead to radical change or social regulation. The second model uses the work of Holen et al. (Citation2020) and focuses on the different roles students and teachers perform in L-TPs. The third uses Fielding’s (Citation2012) patterns of partnership typology to identify different levels of student influence in partnerships. The resulting conceptual framework helps frame thinking, planning, practice and leadership of L-TPs.

Distributive leadership as a heuristic foundation of L-TPs

In traditional FHE contexts the teacher leads and makes decisions about what is to be learnt and how. But leadership practices that fit partnership principles like inclusive relationships, power sharing, uncertain results, ethical practice, and transformation (c.f. Matthews Citation2017; Dianati and Oberhollenzer Citation2020) do not readily fit traditional teacher dominant decision making. They serve leadership better in partnerships that enable learners and teachers to contribute equally but not necessarily in the same way to what happens in classrooms (Cook-Sather, C. Bovill, and Felten Citation2014). Northouse’s (Citation2016) idea of leadership as a process of influence in which a collective motivates others to pursue a common purpose, fits both distributive leadership and L-TPs. He rejects the idea that leadership is a trait or position. Leaders do not lead because of their job title, but because of their influence on the people they lead (Giles Citation2019). Central to leadership-as-practice is that it decouples leadership from an officially titled leader and reshapes leadership as a function of purpose, culture, practice and opportunity rather than as a predetermined role. Leadership-as-practice shifts our attention more to how influence operates, circulates and evolves, than how a designated person exercises it. The process of leading, rather than the position leader comes to the forefront of our thinking (Youngs Citation2017). Leading becomes a distributed practice shared by all partners. This changes the understanding of L-TPs as separated learners and teachers to partners sharing leadership.

Distributive practice is based on the idea that leading is an emergent property arising from concertive action, in which the efforts of all participants acting together are more important than the efforts of one (Woods and Roberts Citation2015). Students have equally important responsibilities as teachers and administrators in leading towards their common goal. Distributive leading practice is feasible in FHE because adult students and teachers have different but complementary experiences, skills, and attributes to achieve desired outcomes (Brookfield and Holst Citation2011). All participants are active leaders in consertive action. Leading such action is relational, exercised as collective labour using the energy, experiences, and abilities of all participants (Giles Citation2019; Gronn Citation2002). Concertive action has many guises. It can involve collaboration of all partners. It can also involve role sharing with two or more people leading a group to complete different aspects of a task. It can be formalised so that designated participants are recognised by agreement as official leaders of a project. Whichever form of concertive action emerges, leadership processes and relationships in distributive practice are dynamic, goal oriented, and shared. It divides tasks with responsibilities agreed according to experience and skills for the moment. Partners work within networks of concertive action as leaders and/or followers according to the needs of the group. Leading concertive action is not necessarily harmonious, as partners must continue to negotiate any differences throughout the project (Harris and DeFlaminis Citation2016; Woods and Roberts Citation2015).

Leading concertive action for shared purposes, as suggested in distribute leadership, involves the exercise of power (Lumby Citation2013, Citation2019). Lumby accepts, that distributive leadership may be no more than a fashionable concept that maintains the status quo of power relations. But it can also be an ideal heuristic tool to explore how distributive practice can help make meaning of L-TP and serve as a foundation for any kind of fluid partnership that shows power relations in LT-Ps as capable of leading to both change and stability. To help understand this, Foucault’s work is useful. To Foucault, power is everywhere, not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere: ‘it is produced from one moment to the next, at every point, or rather in every relation from one point to another’ (Foucault Citation1981, 93). Power is neutral flowing in circuits, is episodic and its effects are how it is used to influence relationships. True, power can collect in disciplining regimes of truth; for example, in the idea that leadership must be exercised by teachers. But this and other regimes of truth are challenged by distributive practice. Power in teams resides in relationships that recognise the expertise of all. It is used when completing different tasks to help achieve a group’s purposes. In short, distributive practice recognises that learners and teachers each exercise power to help achieve common goals. Such power sharing is central to learning-teaching partnerships.

Power sharing makes clear that leading in distributive practice is not about the separate agency and power of either student or teacher but is about their conjoint activities as interdependent partners (Gronn Citation2002). Views about conjoint activities differ (c.f. Engestrom, Miettinen, and Punamaki Citation1999; Wenger Citation1998). While Y. Engestrom, R. Miettinen, and R. Punamaki (Citation1999) do not specifically discuss L-TPs, their activity theory is relevant to explaining the circulation of power. Conjoint activity is a division of labour with fluid power relationships within an ever-changing social system. Distributive practice in L-TPs involves dynamic relationships between learners, teachers, administrators and community agents. Somewhat akin to Foucault’s ideas, power circulates among them depending on the needs and flow of activities in different learning-teaching contexts. One goal is radical change in higher education, the other social regulation. Radical change presupposes that distributive leadership results in transformative change in activity systems by exposing domination and injustice. Social regulation assumes maintenance of social order through cohesion and consensus. Distributive leading also identifies two opposing views of knowledge. One espouses subjectivism – the idea that knowledge is restricted to what we have experienced; the other objectivism – that knowledge is external to what we have experienced.

Burrell and Morgan (Citation1979) depict opposing goals and different types of knowledge in distributive practice as distinct paradigms shown as a four cell matrix fashioned by two intersecting axes (). A vertical axis divides the two overarching distributive leadership goals. A horizontal axis depicts the two understandings of knowledge. The resulting quadrants produce four paradigms. A functionalist paradigm sees distributive leadership as akin to the natural sciences and informed by objective facts. Power sharing participants pursue goals that meet specific, and evidence based outcomes. In the interpretive paradigm leadership is hermeneutic seeking mutual understanding of issues, people, and operations. Leading in this paradigm involves setting and pursuing goals that meet the ideological requirements of an activity system. Leading in the radical humanism paradigm involves participants critiquing dominant ideologies that challenge the false consciousness of individuals. In radical structuralism the purpose of distributive practice is to refocus individual consciousness to spotlight ways to challenge and change accepted structures. pictures the four paradigms.

Figure 1. Sociological paradigms and organisational analysis (Hartley Citation2010).

Hartley (Citation2010) uses Habermas (Citation1987) theory of human cognitive interest to reframe this understanding of research in distributive leadership. The principles underpinning the four paradigms in remain, but by using Habermas’ human cognitive interests they become more flexible, dynamic and without set boundaries. The potential purposes of distributive leadership, radical change or social regulation remain, but instead of being informed by functionalism and interpretivism, social regulation is reframed as Habermas’ technical – instrumental and practical cognitive interests. Radical humanism and structuralism are combined to become critical human interests. Distributive practice is now variable, can cross former paradigm boundaries and is suited to different practice contexts. This reconceptualisation is also relevant to L-TP research. shows the changes. Hartley (Citation2010) observes that distributive practice in FHE tends to aim for social regulation within a collaborative status quo. Here Habermas’ practical and technical-instrumental cognitive interests dominate. Supporting this goal today is neoliberalism, a hegemonic force in daily life, society, economics, politics and education (Springer, Birch, and MacLeavy Citation2016). Knowledge is often technical-instrumental, interpreted as fact-totems (de Santos Citation2009). Radical change is informed by critical theory and is generally the goal espoused by scholars writing about L-TPs (e.g. Bovill Citation2020; Buckley Citation2018; Zepke Citation2020). Viewed through the lens of human cognitive interests, distributive leadership can draw on all knowledge types.

Towards a conceptual framework for L-TP

In this section, we shift the focus from distributive leading practice to a closer look at how it applies L-TPs principles such as inclusive relationships, power sharing, uncertain results, ethical practice, and transformation. has porous rather than rigid boundaries so distributive leadership practices can range between goals of radical change and social regulation (Buckley Citation2018). The purposes of a partnership, the roles learners and teachers play in it, and how power circulates in a relationship will determine where between radical change and social regulation L-TPs leadership is placed. Holen et al. (Citation2020) offer a model of four distinct student roles in partnerships. Fielding (Citation2012) identifies six levels of student influence in his ‘patterns of partnership’ model. While not models of distribute leadership, Holen et al. (Citation2020) and Fielding (Citation2012) help us to identify who leads and how in a specific situation. While most L-TPs researchers like to see L-TP pedagogy as radical, in neoliberal times, distributive practice can also focus students on maintaining social regulation (K. Matthews, A. Dwyer, and S. Russell et al. Citation2019; Peters and Mathias Citation2018). de Bie (Citation2022) for example, writing from a disabled ‘mad’ minority perspective, suggests that L-TPs generally strive to maintain social regulation not achieve radical social change and should be respectfully distrusted.

Holen et al. (Citation2020) offer further insights about distributive leadership practice in L-TPs by sketching four different student partnership roles: student as apprentice, student as follower, student as democratic participant, and student as customer. In ‘students as apprentice’ students and teachers share a consensus about the goals of the partnership. They agree that teachers initiate and lead activities at first. Students assume greater leadership roles as they gain necessary knowledge and skills. The purpose of partnership in the ‘student as follower’ role is to implement government policies for student participation in educational settings. They may include students sitting on institutional committees and task forces. Partnership roles are set out in official policy documents. Student influence grows with trust and familiarity with requirements. The ‘student as democratic participant’ role can be understood as student voice and action. While teachers and administrators initiate the process, students take over and gain equal but not necessarily the same power to implement change. The ‘student as customer/consumer’ role is driven by neoliberal ideas promoted in public management theory. Students are encouraged to take advantage of and provide feedback on university services. While all roles require some student participation in leading, only the democratic role puts it towards the radical change end of the continuum.

Fielding’s (Citation2012) ‘patterns of partnership’ model identifies six levels of interaction between teachers and learners in compulsory education. His levels of interaction seem applicable to FHE also. The first is students as data source. Here, teachers and administrators use information about student progress and well-being to plan, deliver and evaluate programmes. The second level involves students as active respondents. Teachers and administrators invite student dialogue and discussion to inform their decisions. Students are participants in, rather than just receivers of instruction. At the third-level students are co-enquirers. Teachers take the lead role but with active student support and input. Leadership is not equal but is moving to become more interdependent. The fourth level sees Students as knowledge creators. Students take lead roles with active teacher support. Students’ voices come to the fore in enquiries/projects with the support of teachers. Students as joint authors is the fifth level. Here, students and teachers decide on a joint course of action together. Leadership, planning, research and action are mutual responsibilities. The sixth level Fielding calls intergenerational learning as lived democracy. Here, partnership focuses on an equal sharing of power and responsibility. He sees this level as the peak of partnership practice. As in Hartley (Citation2010) and Holen et al. (Citation2020), Fielding’s levels of partnership can occupy different positions between social regulation and radical change.

The conceptual framework of partnership in L-TPs emerges when the works of Hartley (Citation2010), Holen et al. (Citation2020) and Fielding (Citation2012) are considered together. The foundation of the framework is Hartley’s adaption of the distributed leadership research matrix pictured in . Here distributive leadership research shows goals leading to social regulation, radical change or something in between. By overlaying Habermas’ theory of cognitive interests on the matrix, he suggests that the boundaries between the quadrants of the matrix become malleable. Distributive leading takes partnership closer to or further away from radical change. Holen et al. (Citation2020) take this further by identifying four different roles. Only one of these can confidently be called equally distributed and enabling radical change. But even for this role different levels of influence can be recognised as shown by Fielding’s patterns of partnerships. provides a picture of a conceptual L-TP framework drawing on the three models. Purposes sit on a continuum between social regulation and radical change. Students’ roles change according to the purposes of practice. At the social regulation end of the continuum student roles and influence are limited but increase the closer distributive leadership is to the radical change goal.

How the conceptual framework helps inform L-TP planning and practice

The framework is designed for praxis, to help all partners judge (i): where their leadership practice sits or where they want it to fit on the continuum between social regulation and radical change (ii); how the roles of partners align with the four idealised roles in Holen et al. (Citation2020); and (iii) how much power students exercise in a partnership (Fielding Citation2012). The framework helps critical reflection and action on three key questions: what are the purposes of the partnership? What are the leadership roles of students in it? How powerful are students in the partnership (Fielding Citation2012)? The questions help partners to understand how their L-TP operates, how it stimulates student voice and action in collective decisions about desired directions, roles and power distribution in their L-TP.

At a conceptual level a first decision for partners in a L-TP is whether they want to maintain social regulation, achieve radical change or steer somewhere in between. If practice in the L-TP offers an apolitical commercial exchange of technical knowledge to achieve student success such as completion and employability (e.g. Matthews Citation2017; Zepke Citation2020), the primary purpose would steer towards social regulation. Where the partnership seeks communicative action (Habermas Citation1987), consensus, compassion (Zembylas Citation2017) and transformation of traditional power structures, radical change would be the goal. All such choices have consequences. To maintain social regulation assumes support for existing policy frameworks. These are currently dominated by neoliberalism at all levels of the post-school ecosystem (Springer, Birch, and MacLeavy Citation2016; Tomlinson Citation2017). Striving for radical change means leading to transform hegemonic neoliberal policy frameworks and practices. Whether neoliberalism also dominates student engagement practice, and its L-TP strand is keenly debated. On one side researchers like Buckley (Citation2018) and Bovill (Citation2020) see L-TP as promoters of democratic practice in opposition to neoliberalism. Others argue that a genuinely transformative interpretation of the purposes of partnership is problematic (Carey Citation2013; Zepke Citation2020). They think research is often unclear about how much power transfers to students in a partnership (Carey Citation2013; Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2017). In his thesis Carey (Citation2013) comments that the power sharing discourse around L-TP may be due more to neoliberal governmentality shaping politics and practices than to critique or oppose neoliberalism.

At a more operational level, framework offers an analytic tool whether the partnership steers more towards maintaining social regulation or radical change. Support for radical change purposes is widespread in the published partnership literature (Bovill Citation2020). It is widely accepted there that L-TP partners contribute equally but perhaps differently to decision-making, implementation, investigation and evaluation of pedagogy and curriculum (Cook-Sather, C. Bovill, and Felten Citation2014). Numerous articles describe how this definition works in practice. In their systematic literature review Mercer-Mapstone et al. (Citation2017), for example, reported positive outcomes for both student and teacher leaders in a large majority of the 68 studies sampled. Only a small minority reported negative outcomes and these only for students, not other partners. Indeed, L-TPs are often seen as a counternarrative to traditional and neoliberal expectations (K. Matthews, A. Cook-Sather, and A. Acai et al. Citation2019). However, others see L-TPs as having to work within the ideological and structural frameworks created by neoliberalism. The requirements for performativity, marketisation and commodification are now hegemonic and make radical change difficult to achieve (Carey Citation2013; Zepke Citation2020). Buckley (Citation2018) adds that only a small minority of L-TPs sit at the radical change end of the distributive leadership continuum. Moreover, Mercer-Mapstone et al. found that most partnerships operate outside the graded curriculum, were small-scale of up to 5 students, and a few even felt that partnership practices reinforced existing power inequalities (see also de Bie Citation2022).

Published research also suggests that student leadership roles in L-TPs vary widely. They appear to be spread on the continuum between maintaining the status quo and full-blown democratic practice (Toshalis and Nakkula Citation2012). In some instances, student leadership experiences seem transformational. In one very small-scale partnership, for example, a teacher and student partner attended a conference with the teacher progressively transferring the power in their presentation to the student (Eady and Green Citation2020). The student’s reflection suggests that it only gradually dawned on her that she had become the leading partner. In another case, Zepke (Citation2020) describes a situation in which students in a large, nationwide programme transformed the learning process by seizing leadership roles for change in areas not originally intended. But Holen et al. (Citation2020), found that partnership roles in selected centres of teaching excellence in Norway were limited. They described student leadership in centres more as apprentice, follower and customer than equal partner in a living democracy. Students participated in application processes, worked with teachers as research assistants and played a role in institutional governance and decision-making but did not seem to exercise equal power in exercising concertive action with teachers and administrators. This limited the extent leadership was distributed in the partnership. On balance, there is more evidence of students playing subsidiary roles under teacher mentors in small scale extra- curricular projects, than of students leading from the front in large classes (Bovill Citation2020).

Dianati and Oberhollenzer (Citation2020) distinguish ‘student-voice’, which refers to student views being taken seriously, and ‘student-action’ where students take active lead roles in a partnership. Student voice leans towards maintenance; student action towards radical change. The critical theory of Freire informed the practice of A. Kaur, R. Awang-Hashim, and M. Kaur (Citation2019) which aimed at radical change. Interviews with L-TP participants revealed that most students conceived their experience as a conjoint building of a lasting learning community built on trust, respect, positive emotions, inspiration and feelings of empowerment. Another project introduced a summative assessment into a tax module. Students created multiple choice questions based on module content. They became active creators of content rather than passive consumers as their questions were placed in a question bank, with some used in the final exam (Doyle, Buckley, and Whelan Citation2019). However, there is more evidence that student influence in L-TPs is weighted towards student voice and maintenance rather than student action for radical change. Mercer-Mapstone et al. (Citation2017) reported relatively few studies where student leaders actively helped shape L-TP practice. For example, 89% of sampled studies for their review were written by teacher first authors, only 7% by student first authors. Moreover, in a study of institutional executives, K. Matthews, A. Dwyer, and S. Russell et al. (Citation2019) found that in line with neoliberal thinking, university leaders saw L-TPs as sources for feedback (student voice) useful for enhancing products rather than as agents of transformation.

Reflection

Three reflection points about L-TP research and practice are discussed in this section. One considers whether distributive leadership practice is an appropriate heuristic device for L-TPs (c.f. Jones et al. Citation2017). L-TP literature refers to various principles: inclusive relationships; power sharing; uncertain results, ethical practice; transformation; shared responsibilities and behaviours such as direction setting, decisions making, path finding, consensus building, change creation based on an ethics of care in learning and teaching (Gibson and Cook-Sather Citation2020; Matthews Citation2017). Distributive practice draws on similar ideas. Leading involves concertive action where all participants act together to achieve common purposes (Woods and Roberts Citation2015). Power sharing is not about the separate agency and power of either students or teachers but is about their conjoint activities as interdependent partners (Gronn Citation2002). Leading conjoint action is relational, exercised as collective labour using the energy, experiences, and abilities of all participants (Giles Citation2019; Gronn Citation2002). In short, L-TP principles are like those underpinning distributive practice. Given these shared principles, using distributive leadership heuristic as the conceptual foundation for a partnership framework is defensible. However, the close link between distributive leadership and partnership pedagogy does not suggest that it automatically leads to either radical change or systems maintenance. How it works in practice is based on more practical foundations such as how student action is fostered, recognised and valued in teaching and management processes required in neoliberal times.

A second reflection point ponders whether the conceptual framework () is fit for purpose as a reflective planning tool. The Hartley (Citation2010) three cell matrix works well when estimating purposes of published L-TP research. A common-sense assumption for neoliberal times is that L-TPs will have goals somewhere on the continuum between social regulation and radical change. Reading selectively in the literature suggests that the majority leans towards the social regulation end. The Holen et al. (Citation2020) matrix with its four student roles was chosen over other frameworks (see Varwell Citation2021) as the labels ‘apprentice’, ‘follower’, ‘democratic participant’ and ‘customer’ seem well suited to a neoliberal system. All these roles are evident in the literature consulted but even the ‘democratic participant’ role seemed limited to ‘student voice’ over student action’ (Holen et al. Citation2020; Zepke Citation2020). Fielding’s (Citation2012) levels of influence are more difficult to assess as a gauge of student influence and power. They do not align clearly with either maintenance or radical change. For example, in Eady and Green’s account it is a matter for judgement whether the student’s influence is as co-enquirer (more system maintenance) or joint author (more radical change). Reflection is always a matter of interpretation based on an assessment of available evidence. Even with this reservation, the framework seems suitable as a reflection tool for understanding and improving practice.

A third reflection point is whether leadership should even be a consideration in discussions about partnership. The widely accepted definition of L-TP as learners and teachers contributing equally but not necessarily in the same way to partnerships (Cook-Sather, C. Bovill, and Felten Citation2014) could be an important contributor to this reflection point as this definition seems to mute questions about who leads. Yet, leaders of content and practice are necessary in the classroom. Traditionally more likely to be teachers, students in L-TPs also exercise leadership. Moreover, in neoliberal times leaders are needed in partnerships to meet performativity, marketing and accountability requirements. In short, a focused discussion of leadership is needed. Varwell (Citation2021) assists such a discussion. He lists seven partnership frameworks that feature in Scotland’s Student Engagement Framework. These ‘sparqs’ take the form of either four cell matrices or as ladders of student participation. One of the matrix frameworks (Dunne and Zandstra Citation2011, 17) includes a quadrant labelled student as ‘agent for change’. Clearly here students are in strong leadership roles. Similarly Bovill and Bulley (Citation2011, 5), ladder of student involvement has ‘students in control’ at the top rung on their ladder. Such frameworks reveal that to understand the full meaning of partnership, a focused discussion of leadership is needed. Distributive leadership is a useful starting point in this discussion.

Conclusion

I have argued that who leads and how in a learner–teacher partnership is important. The argument is based on four propositions. One is that distributed leadership is a suitable conceptual and practice heuristic tool for discussing leading in L-TPs as both work to similar principles such as inclusive relationships, power sharing, uncertain results, ethical practice, and transformation. A second proposition offers a conceptual framework visualising purposes for L-TPs as located on a continuum ranging from social regulation where students are assistants to teachers and adhere to neoliberal aims to radical change where students are active leaders in a living democracy. A third proposition is that the conceptual framework provides a useful tool for planning and continually reviewing partnership experiences. A fourth proposition holds that students as adults can use their life experiences to be effective leaders of their peers and their teachers by partnering them in concertive action to achieve common learning goals. This means that both partners can grow as learners and teachers in a FHE setting. However, the framework has limitations. It is constructed from published works carefully selected to illuminate both ends of the partnership continuum and not from systematic primary research. The latter is needed to validate the framework. Despite this limitation, the paper offers a starting point in the proposed discussion of L-TP pedagogy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Barnett, R. 2011. “Life-Wide Education: A New and Transformative Concept for Higher Education.” In Learning for A Complex World: A life-Wide Concept of Learning, Education and Personal Development, edited by N. Jackson. UK: Authorhouse.

- Bovill, C. 2020. “Co-Creation in Learning and Teaching: The Case for a Whole-Class Approach in Higher Education.” Higher Education 79 (6): 1023–1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w.

- Bovill, C., and C. J. Bulley. 2011. “A Model of Active Student Participation in Curriculum Design: Exploring Desirability and Possibility.” In Improving Student Learning (ISL) 18: Global Theories and Local Practices: Institutional, Disciplinary and Cultural Variations, edited by C. Rust, 176–188, Oxford, UK: Oxford Brookes University.

- Brookfield, S., and J. Holst. 2011. Radicalizing Learning: Adult Education for a Just World. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- Buckley, A. 2018. “The Ideology of Student Engagement Research.” Teaching in Higher Education 23 (6): 718–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1414789.

- Burrell, G., and G. Morgan. 1979. Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Carey, P. (2013). “Student Engagement in University Decision-Making: Policies, Processes and the Student Voice.” Doctoral Thesis, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK.

- Cook-Sather, A., C. Bovill, and P. Felten. 2014. Engaging Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching: A Guide for Faculty, 6–7. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- de Bie, A. 2022. “Respectfully Distrusting ‘Students as Partners’ Practice in Higher Education: Applying a Mad Politics of Partnership.” Teaching in Higher Education 27 (6): 717–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1736023.

- de Santos, M. 2009. “Fact-Totems and the Statistical Imagination: The Public Life of a Statistic in Argentina 2001.” Sociological Theory 27 (4): 466–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01359.x.

- Dianati, S., and Y. Oberhollenzer. 2020. “Reflections of Students and Staff in a Project-Led Partnership: Contextualised Experiences of Students-As-Partners.” International Journal for Students as Partners 4 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijL-TPS.v4i1.39742.

- Doyle, D., P. Buckley, and J. Whelan. 2019. “Assessment Cocreation: An Exploratory Analysis of Opportunities and Challenges Based on Student and Instructor Perspectives.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (6): 739–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1498077.

- Dunne, E., and R. Zandstra. 2011. Students as Change Agents: New Ways of Engaging with Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. UK: University of Exeter, ESCalate, and the Higher Education Academy. http://escalate.ac.uk/downloads/8244.pdf.

- Eady, M., and C. Green. 2020. “The Invisible Line: Students as Partners or Students as Colleagues?” International Journal for Students as Partners 4 (1): 148–153. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v4i1.3895.

- Engestrom, Y., R. Miettinen, and R. Punamaki. 1999. Perspectives on Activity Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press).

- Fielding, M. 2012. “Beyond Student Voice: Patterns of Partnership and the Demands of Deep Democracy.” Revista de Educacion (359): 45–65.

- Foucault, M. 1981. The History of Sexuality. Vol. 1. London, UK: Penguin.

- Fredricks, J., P. Blumenfeld, and A. Paris. 2004. “School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence.” Review of Educational Research 74 (1): 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059.

- Gibson, S., and A. Cook-Sather. 2020. “Politicised Compassion and Pedagogical Partnership: A Discourse and Practice for Social Justice in the Inclusive Academy.” International Journal for Students as Partners 4 (1): 16–33. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijL-TPS.v4i1.3996.

- Giles, D. 2019. Relational Leadership: A Phenomenon of Inquiry and Practice. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429445583.

- Gronn, P. 2002. “Distributed Leadership.” In Second Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration, edited by K. Leithwood, P. Hallinger, K. Seashore-Louis, G. Furman-Brown, P. Gronn, W. Mulford, and K. Riley, 652–696. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer.

- Habermas, J. 1987. Knowledge and Human Interests, Trans. J. Shapiro. Oxford, UK: Polity Press.

- Harris, A., and J. DeFlaminis. 2016. “Distributed Leadership in Practice: Evidence, Misconceptions and Possibilities.” Management in Education 30 (4): 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/08920206166567.

- Hartley, D. 2010. “Paradigms: How Far Does Research in Distributed Leadership ‘Stretch’?” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 38 (3): 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143209359716.

- Healey, M., A. Flint, and K. Harrington. 2014. Engagement through Partnership: Students as Partners in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. Higher Education Academy. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/engagement-through-partnershipstudents-partners-learning-and-teaching-higher.

- Holen, R., P. Ashwin, P. Maassen, and B Stensaker. 2020. “Student Partnership: Exploring the Dynamics in and between Different Conceptualizations.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (8): 1737–1745. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1770717.

- Jones, S., M. Harvey, J. Hamilton, Bevacqua, K. Egea, J. McKenzie, and J. Bevacqua. 2017. “Demonstrating the Impact of a Distributed Leadership Approach in Higher Education.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 39 (2): 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2017.1276567.

- Kahn, P. 2014. “Theorising Student Engagement in Higher Education.” British Educational Research Journal 40 (6): 1005–1018. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3121.

- Kahu, E. 2013. “Framing Student Engagement in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (5): 758–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.598505.

- Kaur, A., R. Awang-Hashim, and M. Kaur. 2019. “Students’ Experiences of Co-Creating Classroom Instruction with Faculty- A Case Study in Eastern Context.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (4): 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1487930.

- Kift, S. 2015. “A Decade of Transition Pedagogy: A Quantum Leap in Conceptualising the First-Year Experience”. HERDSA Review of Higher Education. 2: 51–86. www.herdsa.org.au/herdsa-review-higher-education-vol-2/51-86.

- Kuh, G., T. Cruce, R. Shoup, J. Kinzie, and R. Gonyea. 2008. “Unmasking the Effects of Student Engagement on First-Year College Grades and Persistence.” The Journal of Higher Education 79 (5): 540–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2008.11772116.

- Lawson, M., and H. Lawson. 2013. “New Conceptual Frameworks for Student Engagement Research, Policy and Practice.” Review of Educational Research 83 (3): 432–479. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313480891.

- Lumby, J. 2013. “Distributed Leadership: The Uses and Abuses of Power.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 41 (5): 581–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213489288.

- Lumby, J. 2019. “Leadership and Power in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (9): 1619–1629. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1458221.

- Matthews, K. 2017. “Five Propositions for Genuine Students as Partners Practice.” International Journal for Students as Partners 1 (2). https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i2.3315.

- Matthews, K., A. Cook-Sather, A. Acai, S. Dvorakova, P. Felten, E. Marquis, and L. Mercer-Mapstone. 2019. “Toward Theories of Partnership Praxis: An Analysis of Interpretive Framing in Literature on Students as Partners in Teaching and Learning.” Higher Education Research & Development 38 (2): 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1530199.

- Matthews, K., A. Dwyer, L. Hine, and J. Turner. 2018. “Conceptions of Students as Partners.” Higher Education 76 (6): 957–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0257-y.

- Matthews, K., A. Dwyer, S. Russell, and E. Enright. 2019. “It Is a Complicated Thing: Leaders’ Conceptions of Students as Partners in the Neoliberal University.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (12): 2196–2207. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1482268.

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., L Dvorakova, K. Matthews, S. Abbot, B. Cheng, P. Felten, K. Knorr, E. Marquis, R. Shammas, and K. Swaim. 2017. “A Systematic Literature Review of Students as Partners in Higher Education.” International Journal for Students as Partners 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.15173/ijL-TPS.v1i1.3119.

- Northouse, P.G. 2016. Leadership: Theory and Practice. 7th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishers,

- Peters, J., and L. Mathias. 2018. “Enacting Student Partnership as though We Really Mean It: Some Freirean Principles for a Pedagogy of Partnership.” International Journal for Students as Partners 2 (2): 53–70. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v2i2.3509.

- Springer, S., K. Birch, and J. MacLeavy. 2016. The Handbook of Neoliberalism. London: Routledge.

- Thomas, L. (2012). “Building Student Engagement and Belonging in Higher Education at a Time of Change: Final Report from the What Works? Student Retention and Success Project.” https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/resources/What_works_final_report.pdf.

- Tomlinson, M. 2017. “Student Engagement: Towards a Critical Policy Sociology.” Higher Education Policy 30 (1): 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-016-0026-4.

- Toshalis, E., and M. J. Nakkula. 2012. “Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice.” In Students at the Centre Series. Boston, MA: Jobs for the Future.

- Varwell, S. 2021. “Models for Exploring Partnership: Introducing Sparqs’ Student Partnership Staircase as a Reflective Tool for Staff and Students.” International Journal for Students as Partners 5 (1): 108–121. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v5i1.4452.

- Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Woods, P., and A. Roberts. 2015. “Distributed Leadership and Social Justice: Images and Meanings from across the School Landscape.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 19 (2): 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2015.1034185.

- Youngs, H. 2017. “A Critical Exploration of Collaborative and Distributed Leadership in Higher Education: Developing an Alternative Ontology through Leadership as-Practice.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 39 (2): 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2017.1276662.

- Zembylas, M. 2017. “In Search of Critical and Strategic Pedagogies of Compassion: Interrogating Pity and Sentimentality in Higher Education”. In The Pedagogy of Compassion at the Heart of Higher Education, edited by P. Gibbs, 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57783-8_5.

- Zepke, N. 2017. Student Engagement in Neoliberal Times. Theories and Practices for Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-103200-4.

- Zepke, N. 2020. “Sharing Power with Students in Higher Education: A Critical Reflection.” In Vol. 2 Student Empowerment in Higher Education, edited by A. Mukadam and S. Mawani, 499–510. Germany: Logos Verlag.