ABSTRACT

There has been a shift in tertiary education, whereby large portions of theory are now taught online, and the practical skills underpinned by this knowledge taught in clinical environments. It is unclear if this flipped approach is appropriate for the learning styles Exercise Science (ES) and Clinical Exercise Physiology (CEP) students. First- and second-year ES and CEP students at a South Australian metropolitan university were invited to participate between March 2021 and October 2022. Eligible participants completed the Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory (KLSI) (Version 3.1) to identify learning styles. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the four KLSI learning orientations. Group scores for the learning orientations were used to identify group preference for abstractness over concreteness and action over reflection. A total of 69 students completed the KLSI fully. As a single cohort, Accommodators were the most common learning style, and there was a preference for concreteness over abstractness when gaining experience and a preference for action over reflection when transferring experience into knowledge. These findings indicate that Australian ES and CEP students have a unique learning style that may be suited to flipped classroom approaches, but only if they include opportunity to experience skill learning in a hands-on manner, while also allowing time for reflection.

Introduction

The purpose of teaching is to facilitate learning and develop the skills and knowledge required to practice in society. In the fields of exercise science (ES) and clinical exercise physiology (CEP), the development of clinical skills pertaining to subjective and objective assessment, exercise prescription, and exercise monitoring are vital as they can have profound implications on patient safety and clinical effectiveness (ESSA Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Consequently, the teaching of clinical skills is an important educational component in these cohorts (Johnson, Chuter, and Rooney Citation2013).

However, over the last decade, there has been a shift in tertiary education, whereby large portions of learning are now conducted in an online format (Ewing Citation2021). This often involves theoretical concepts and knowledge being taught online, and the practical skills underpinned by this knowledge taught in clinical environments using a ‘flipped classroom’ approach (Rapanta et al. Citation2020; Strelan, Osborn, and Palmer Citation2020). While this has been shown to be an effective means of teaching theoretical information (Castro and Tumibay Citation2021; Strelan, Osborn, and Palmer Citation2020), students need to have the capacity to apply this learning into practical situations. It is unclear as to whether this blended learning approach is appropriate for the learning styles of students in ES and CEP programmes.

Literature review

Blended learning and the flipped classroom approach

Methods of online education have become common in tertiary settings, where they are suggested to offer students a flexible and self-paced learning strategy, with blended learning being one such method. Blended learning is a broad term used to describe a combination of face-to-face teaching with technology-mediated instruction, whereby all students are separated by distance some of the time (Liu et al. Citation2016). Taking this into consideration, flipped classrooms can be viewed as a type of blended learning approach, where lectures and other theoretical content are made available to students in advance, often in an online format, so they can study them in their own time (Sajid et al. Citation2016). Consequently, time in class is spent undergoing interactive teaching activities that are typically linked to practical skills, building upon pre-delivered online content. There is robust evidence indicating that blended learning leads to similar or better learning outcomes that traditional ‘non-blended’ approaches in students studying areas pertaining to allied health and medicine (Liu et al. Citation2016; Vallée et al. Citation2020). Similarly, flipped classroom approaches have been shown to increase the performance of students undergoing health professional education (Hew and Lo Citation2018), with no apparent negative effects on student satisfaction (van Alten et al. Citation2019). However, despite the apparent benefit of these approaches in numerous allied health professions, there is little direct evidence examining their effect on learning outcomes in ES and CEP students specifically. In fact, on the contrary, there is some evidence suggesting that Australian CEP and ES cohorts may have unique concerns about blended learning approaches that could impact their uptake. In some research Australian ES students have expressed worry about not being sufficiently autonomous to undertake the independent study flipped classrooms require (Keogh, Gowthorp, and McLean Citation2017), while others have highlighted that virtual lectures delivered within a flipped classroom method are less engaging than more traditional lectures, and that only a minority of students are completely up to date with the required content when they attend their in-person practical sessions (Burkhart et al. Citation2020). Lastly, research in Australian allied health cohorts including ES students has reported that approximately only half of students prefer a flipped classroom approach, with the other half demonstrating a strong preference for traditional learning methods (McNally et al. Citation2017). While the exact reason for these findings is not clear, it may imply that CEP and ES students in Australia have a unique style of learning that needs to be considered to design effective blended learning approaches.

Learning styles and the experiential learning theory

It has been proposed that individuals develop their own preferred style of learning. These learning styles can be viewed as the way individuals prefer to process new information, in conjunction with strategies they adopt for effective learning (Milanese, Gordon, and Pellatt Citation2013). In this manner, they have been defined as ‘characteristic cognitive, affective, and psychosocial behaviours that serve as relatively stable indicators of how learners perceive, interact with, and respond to the learning environment’ (Keefe Citation1979). It is suggested that educators who understand and respond to the learning styles of students can improve the retention of important concepts, information, and skills (DiBartola Citation2006). Additionally, there is some evidence to suggest that simply knowing their learning styles (and therefore knowing how they may be best suited to learn) can enhance student learning outcomes (Brown et al. Citation2009). However, to date, there is no evidence of a clear association between learning styles and future knowledge acquisition (Romanelli, Bird, and Ryan Citation2009). Furthermore, a preferred learning style does imply that is the only way an individual learns, but rather the way they are likely to learn best (Romanelli, Bird, and Ryan Citation2009). Nonetheless, being aware of ES and CEP learning styles may assist educators deliver better learning experiences and improve associated outcomes, which is particularly important when considering the clinical skills required in these professions. Similarly, it is important to note that within the context of modern educational practices, research has shown that learning styles may have implications on the effectiveness of blended learning strategies, suggesting an important factor to consider in tertiary education design (Cheng et al. Citation2017).

One notable learning theory is the experiential learning theory (ELT), which suggests learning is ‘the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Knowledge results from the combination of grasping and transforming experience’ (Milanese, Gordon, and Pellatt Citation2013). This theory indicates that experience plays a pivotal role in the learning process. Considering ES and CEP learning is heavily experiential, where students are required to build and then integrate theoretical and practical knowledge (Bryant et al. Citation2003; John Citation2003; Kilminster and Jolly Citation2000), this learning theory has potential relevance for this cohort. Of numerous ELTs, Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory (KLSI) is arguably the most common (D. A. Kolb Citation2014).

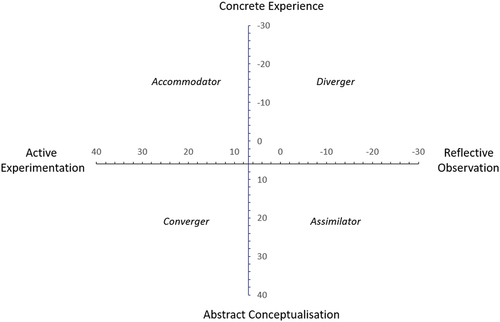

The KLSI is a self-reported questionnaire frequently used to identify learning styles amongst different student groups. KLSI considers learning to be a cyclic process involving four modes, concrete experience (CE) and abstract conceptualisation (AC), reflective observation (RO) and active experimentation (AE), and categorises individuals into one of the four preferred learning styles (i.e. Diverger [CE and RO], Assimilator [AC and RO], Converger [AC and AE] or Accommodator [CE and AE]) () (Manolis et al. Citation2013).

Table 1. The characteristics of the four learning styles.

Potential limitations of the Kolb learning style inventory

While the KLSI is arguably the most common learning style theory, it is not without criticism. Firstly, Kolb suggests that, as students are said to gravitate to their preferred style of learning while avoiding others, they create a positive feedback loop that makes learning styles highly stable (A. Y. Kolb Citation2005). However, it has been hypothesised that learning styles may change when students are exposed to different learning methods, or simply through an accumulation of life experience (Felder Citation2020). Indeed, recent research exploring this topic in Australian engineering students has shown that some students may change learning style preferences in as little as 7 weeks, which may impact upon the utility of the concept when designing educational materials (Newton and Wang Citation2022). Secondly, there is little empirical evidence to suggest that matching education to students KLSI will increase academic outcomes (Dembo and Howard Citation2007). It has been suggested that rigorous within-subject crossover designs comparing a learning-style matched education against a non-matched education are needed to answer this question, which have not yet been conducted (Deng, Benckendorff, and Gao Citation2022; Pashler et al. Citation2008). Lastly, in conjunction with potential issues associated with stability and validity, other literature has critiqued the model of the KLSI itself. It has been suggested that the KLSI fails to sufficiently differentiate between concrete and abstract learning processes, does not clearly distinguish between learning activities and learning typologies, and does not identify all viable learning constructs, all of which impacts the clarity of the KLSI (Bergsteiner, Avery, and Neumann Citation2010). In this manner, it has also been suggested that the KLSI somewhat oversimplifies the learning process, as it fails to consider the role of unconsciousness in learning (Villanueva Citation2020), something that is thought to be linked to the consolidation of knowledge (Fukuta and Yamashita Citation2021). While this does not deny the potential applications of the KLSI in tertiary education, it does highlight the need for more rigorous research on those applications, and suggests that educators should pay careful consideration to the limitations of the tool when implementing learning style driven educational strategies.

Learning styles in allied health contexts

There is a large body of research identifying the learning style preferences of physiotherapy students (Stander, Grimmer, and Brink Citation2019), nurses (Bakon, Christensen, and Craft Citation2016), and other allied health practitioners (French, Cosgriff, and Brown Citation2007; Koohestani and Baghcheghi Citation2020; McLeod et al. Citation1995). This research has indicated some consistency of learning styles according to discipline with the most preferred learning styles of physiotherapy students being Converger or Assimilator, with the least preferred learning styles being Diverger and Accommodator (Stander, Grimmer, and Brink Citation2019). Amongst nursing students, the evidence suggests that whilst undergraduate nursing students have varied learning styles, the most predominant learning style preference is the Assimilator or Diverger (Campos et al. Citation2022; Shumba and Iipinge Citation2019).

However, the learning styles of ES and CEP students are less explored. Research conducted in the UK identified that students involved in a variety of sport-related tertiary education programmes were more likely to be classified as ‘auditory’, ‘kinaesthetic’, and ‘group’ learners, suggesting that they may be more suited to experiential learning, rather than the conventional learning of theoretical constructs (Peters, Jones, and Peters Citation2008). Similar results have been observed in American anatomy students, who were predominantly classified as active, sensing, visual, and sequential learners in accordance with the Index of Learning Styles (ILS) questionnaire (Quinn et al. Citation2018). However, it is important to note that while these trends were observed, this research used tools that face many of the same criticisms as the KLSI, with further critique for their oversimplification of the learning process and lack of validity in educational settings (Felder Citation2020). Furthermore, prior research has shown that learning style models that employ a visual, auditory, reading, kinaesthetic categorisation method tend to see positive correlations between learning styles, whereby a high score in one is positively associated with high scores in the others (Drago and Wagner Citation2004). As such, it has been suggested that they lack the ability to distinguish between dominant learning styles and are likely to be confounded by students who employ a variety of study methods to facilitate learning (Husmann and O’Loughlin Citation2019).

Specific to the KLSI, research in American ES students has indicated that the largest proportion of learners are classified as Convergers’ (Wagner et al. Citation2014), suggesting they are most likely to learn best using a hands on approach, which may not support the suitability of modern educational approaches (i.e. online theoretical learning, coupled with experiential learning of clinical skills) in ES students. Conversely, this finding was not repeated in a large cohort of Turkish ES students, who were most likely to be classified as Diverger’s and least likely Converger’s (Kurtuluş Citation2022). While the exact reason for this difference between cohorts is unclear, it may be due to different cultural influences, further highlighting the need for learning style research in Australian ES and CEP cohorts. Furthermore, there are key differences between ES and CEP professionals that may result in different learning style orientations. Often CEP involves working with patients with clinical presentations, and consequently involves a high degree of involvement with other health care professionals (Carrard et al. Citation2022; Soan et al. Citation2014). Conversely, many ES professionals work alone within general health or athletic development settings, delivering exercise to an individual or team (Carrard et al. Citation2022; Stevens et al. Citation2018). It is conceivable that the desire to work in notably different roles could result in students enrolled in ES and CEP programmes having different learning style orientations.

Given the importance of teaching clinical skills to Australian ES and CEP students, the various changes seen in tertiary education over the last decade, and the potential for cultural influences on impact on learning styles, the exploration of Australian ES and CEP students learning styles is worthy of attention. As such, this study aims to report the learning style preferences, as measured by the KLSI, of first- and second-year ES and CEP students from a South Australian metropolitan university.

Methods

Research design

This study employed a cross-sectional observational design to understand the learning style of ES and CEP students, as identified by the KLSI. The study was granted ethical approval by the University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol no: 204308).

Participants

Participants were eligible for inclusion in this study if they were aged 18 years or older and currently enrolled in the Bachelor of ES and Bachelor of Human Movement (ES stream) programme, or Bachelor of CEP programme, at the University of South Australia. Participants were recruited between March 2021 and October 2022 via a method of purposive sampling which was accomplished through targeted emails to two courses (one first-year course and one second-year course). First- and second-year students were deemed most suitable for this study as they are most exposed to flipped classroom approaches within this specific tertiary institution, whereas third-year courses are predominantly placement based.

Data collection tools

Eligible participants provided informed consent online prior to completing a basic questionnaire that captured relevant demographic information and the KLSI. All data were obtained through REDcap Survey Platforms (v10.0.19, TN, USA). A total of 97 students viewed the survey, with 69 completing it in full. The KLSI (version 3.1) (A. Y. Kolb Citation2005) has 12 questions, each with four possible responses. Participants were asked to rank the responses that best describe their learning style to the response that least describes their learning style. The assigned value for each response was summed to derive a total for each of the four modes of learning (CE, AC, RO, AE). The value for CE was subtracted from the AC value to calculate a y-coordinate value, and the value for RO was subtracted from the AE value to calculate an x-coordinate value (). These values were then plotted on the KLSI grid to identify the preferred learning style (i.e. Diverger [CE and RO], Assimilator [AC and RO], Converger [AC and AE], or Accommodator [CE and AE]) () of the participants (Manolis et al. Citation2013).

Figure 1. Kolb Learning Style Inventory Grid (adapted from A. Y. Kolb Citation2005).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were calculated for each of the four KLSI learning orientations (i.e. CE, RO, AC, AE). Group mean scores for the learning orientations were then used to identify the group preference for abstractness over concreteness (AC–CE) and action over reflection (AE–RO). Additionally, differences in raw KLSI scores (CE, RO, AC, AE, AC-CE, AE-RO) between gender and programme (i.e. CEP vs ES) were examined using independent samples t-test, while differences in the distribution of KLSI learning styles were compared using a chi-squared test. All statistical analysis was conducted in Stata Statistical Software, release 17 (College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Of the 69 students (aged 22.1 ± 7.6 years) that completed the KLSI, 39 were female, 12 (n = 10 females) were enrolled in a bachelor of CEP, with the remaining 57 (n = 29 females) in bachelor of ES programmes (inclusive of those enrolled in a Bachelor of Human Movement Exercise Science stream). Additionally, 34 were in the first year of study, and 35 in their second. contains the mean scores and standard deviations of the different modes upon which the KLSI is based. Group means for these modes were used to obtain a score of the population characteristics on the two modes of gaining experience (AC–CE) and transforming experience (AE–RO). These results were applied to the normative data provided with the KLSI, and the number of subjects within each learning styles was identified.

Table 2. Kolb learning style inventory scores presented as mean (standard deviation).

At a group level, there was a preference for students for concreteness over abstractness when gaining experience (AC–CE = 4.8; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.0 to 7.5), and when transferring this experience into knowledge, a preference for action over reflection (AE–RO = 8.4; 95‰ CI = 5.9 to 11.0). Accommodators were the most common learning style in this cohort.

When comparing KLSI outcomes between genders, females (AC–CE = 3.1; 95% CI = −0.9 to 7.1) and males (AC–CE = 5.4; 95% CI = 0.7 to 10.1) presented similarly to the larger cohort, reporting a preference concreteness over abstractness when gaining experience. When transferring experience into knowledge, male students reflected the larger cohort with a preference for action over reflection (AE–RO = 15.0; 95‰ CI = 11.3 to 18.8), while females preferred reflection over action (AE–RO = 5.5; 95‰ CI = 2.1 to 8.8). Additionally, females were less likely to be categorised as Converger’s and more likely to be categorised as Assimilators ().

With respect to KLSI by degree, both ES (AC–CE = 4.8; 95% CI = 1.5 to 7.7) and CEP (AC–CE = 5.6; 95% CI = −1.1 to 12.2) students had a preference concreteness over abstractness when gaining experience. When transferring this experience into knowledge, ES students reflected the larger cohort with a preference for action over reflection (AE–RO = 9.7; 95‰ CI = 7.0 to 12.4), while CEP preferred reflection over action (AE–RO = 2.7; 95‰ CI = −4.8 to 10.2). Furthermore, CEP students were more likely to be categorised as Diverger’s than ES students and less likely to be categorised as Accommodator’s ().

Discussion

To the authors' knowledge, this is the first study in the peer-reviewed literature to explore the learning styles of CEP and ES students in Australia using the KLSI. Results found that as a cohort, the most common learning style was Accommodator, followed by Diverger and Assimilator. However, when separated into study programme CEP students were more likely to be Diverger’s than ES students and less likely to be Accommodators. Interestingly, these results are different to previous research conducted on ES cohorts in the American (Wagner et al. Citation2014) and Turkish (Kurtuluş Citation2022) ES students, who were most likely to be classified as Convergers and Diverger’s, respectively. This may highlight potential differences in the learning styles of students from different cultural backgrounds, and with different life experiences, practices, and beliefs, that may be worthy of consideration when designing educational content. The Y-Axis of the KLS grid () depicts the learning preference for gaining experience, ranging from concrete experience (CE) at one end and abstract conceptualisation (AC) at the other. The X-axis depicts the self-reported preference for transforming this experience into knowledge, along the continuum from reflective observation (RO) through to active experimentation (AE). The further an individual is along the axis from the intersection the more they prefer that learning approach and the less likely they are to prefer the opposite approach (A. Y. Kolb Citation2005). When examining the cohort as a single group, there was a student preference for concreteness when gaining experience, and a preference for action when transferring this experience into knowledge. These results are similar to research on other allied health practitioners, including physiotherapists (Brown, Cosgriff, and French Citation2008; Hauer, Straub, and Wolf Citation2005; Katz and Heimann Citation1991; Milanese, Gordon, and Pellatt Citation2013; Wessel and Williams Citation2004; Wessel et al. Citation1999; Zoghi et al. Citation2010) and occupational therapists (Brown, Cosgriff, and French Citation2008; French, Cosgriff, and Brown Citation2007; Hauer, Straub, and Wolf Citation2005; Katz and Heimann Citation1991; Zoghi et al. Citation2010), which are considerably similar to ES and CEP.

Interestingly whilst the preference for concreteness when gaining experience, the profile of learning styles of CEP and ES students in Australia differed slightly from that of physiotherapy students who were least likely to be Accommodators, and most likely to be Assimilators (Stander, Grimmer, and Brink Citation2019). As the CEP/ES learning style data collected in this study were from relatively new students (first and second year) then this difference may reflect a self-selection process for the programmes.

This finding may suggest that Australian ES and CEP students prefer the learning of new information to come from a theoretical perspective, allowing them to think about a given concept or situation before experiencing it, and then when transforming this experience into knowledge, to consolidate this knowledge through ‘real-world’ experiences. This is reinforced when considering the most common learning style was the accommodator, which uses concrete experience and active experimentation to learn information (DiMuro and Terry Citation2007). It has been proposed that individuals with this style learn primarily from experiencing something new and carrying out plans that involve those new experiences. Within this, they also prefer to work in teams to accomplish tasks and consolidate their learning (A. Y. Kolb Citation2005). However, it is important to note that at a cohort level, the preferences for the different approaches were close to the intersection of the axes on the KSLI grid (; ), suggesting that any preference for learning is slight, and that students may be able to move between different learning approaches with minimal impact. This is supported by the relatively even distribution of preference between the remaining three learning styles.

A key finding is the learning style differences observed between CEP and ES students. While both groups had a slight preference for concreteness when gaining experience, CEP had a preference reflection over action when consolidating this experience into knowledge, whereas ES was the opposite. One possible explanation for this finding may be due to the subtle differences in the ES and CEP occupations, which could offer appeal to different types of learners. As CEP is more clinical in nature, it typically involves multidisciplinary treatment with other health care professionals (Carrard et al. Citation2022; Soan et al. Citation2014). As such, this may lend itself to more group work that involves observation, experimentation, and reflection with in a broad interdisciplinary environment. On the other hand, many ES roles have a general health or athletic development focus, whereby individuals are more likely to work alone, delivering exercise to an individual or team (Carrard et al. Citation2022; Stevens et al. Citation2018). Another potential explanation for this finding could be related to the difficulty in gaining acceptance to either programme. In Australia, CEP traditionally has higher entrance requirements than ES. This may lead to different learners self-selecting into different programmes, based upon their potential study habits and exam success. Irrespective of the reason, this is an important finding, as most Australian ES and CEP programmes are taught together for the first 2 years of their degrees, before they begin to differentiate into individualised courses that provide profession-specific knowledge.

With respect to gender, there were some differences in learning styles that are like previous research in health-related student cohorts (Dobson Citation2009; Ibrahim and Hussein Citation2016; Kurtuluş Citation2022; Milanese, Gordon, and Pellatt Citation2013; Wehrwein, Lujan, and DiCarlo Citation2007). Females and males reported a preference concreteness when gaining experience. However, when transferring experience into knowledge, male students reflected preferred action over reflection, while females preferred reflection over action. This resulted in females being less likely to be categorised as Converger’s and more likely to be categorised as Assimilators than males, with a similar proportion of Accommodator’s. From an educational perspective, this may suggest that learning environments that involve the opportunity to experience concepts and skills directly, and observe other students demonstrating those concepts and skills, might be best for mixed-gender classrooms.

Despite subtle differences between males and females, and CEP and ES, students, it is important to highlight that there was consistent preference for concreteness when gaining experience. This finding may indicate that modern educational approaches in tertiary education (i.e. flipped classrooms) where face-to-face teaching time is largely dedicated to experiential learning of clinical skills, may be suitable to the learning styles of ES and CEP students, possibly explaining a small portion of its success in similar cohorts (Gaines Citation2021; Hew and Lo Citation2018; Kazeminia et al. Citation2022). However, it is important to highlight that despite a strong group trend, there were large variations of learning styles on an individual basis (). While it is impossible to always cater to the learning styles of everyone, teaching strategies should involve a degree of flexibility that addresses different learning style needs within a course or lesson (for example, opportunities to both experience a skill in a hands-on manner and watch and reflect on others experiencing that same skill).

When considering these findings in the context of modern education, the preference for concreteness over abstractness when gaining experience, and for action over reflection when transferring this experience into knowledge, is a relevant one. This may suggest a high suitability for the use of blended learning approaches in ES and CEP students, if they contain sufficient opportunity to experience skill learning in a direct hands-on manner and observe others do the same. This learning style preference may explain some recent findings in other allied health cohorts, with both ES and physiotherapy students indicating a strong preference for blended learning over both online-only, and traditional, learning methods (Finlay, Tinnion, and Simpson Citation2022; Marques-Sule et al. Citation2023).

Limitations

There are certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting these findings. The subjects in this study all attended the same metropolitan university and only consisted of first- and second-year students. As such, these results may not generalise to rural universities, or students who are currently in their third or fourth year of study. Additionally, while there were significant differences observed between ES and CEP students, it is important to note that there were only a small number of CEP students in this cohort. While this does represent ~40% of a yearly cohort in the Australian metropolitan university where this research was conducted, these findings may not accurately represent that of the larger CEP programme, or the CEP programmes of other Australian universities. Similarly, the total number of ES students (n = 57) who completed the survey only accounted for ~40% of the yearly ES cohort at this same university, therefore presenting with the same potential limitations. Lastly, as outlined in detail in the introduction section of this paper, the KLSI as a means of categorising students is not without its own potential limitations, with the most relevant in this setting being that student learning styles have been shown to change with education and experience (Newton and Wang Citation2022). Consequently, the learning styles of the first- and second-year ES and CEP students in the present study may change as they transition through their final years of tertiary study. This is further impacted by the cross-sectional design of the study, which does not allow the evaluation of learning styles over time. Future research examining longitudinal changes in learning styles across multiple years of study would provide further insight into how learning styles change across the duration of a student’s higher education.

Practical implications

To summarise the practical implications of these findings for ES and CEP educators:

The most common learning style amongst this cohort of Australian ES and CEP students was the accommodator, whereby, on average, students may prefer new information to come from a theoretical perspective before having the opportunity to consolidate it into knowledge through ‘real-world’ experiences.

However, CEP had a preference reflection over action when consolidating this experience into knowledge, whereas ES was the opposite. This may imply that CEP students prefer the opportunity to practice and develop knowledge in larger group settings, where they have can reflect on their own performance, and the performance of others. Conversely, ES students may gain more from developing knowledge through hands on practical environments, such as placement.

Despite subtle differences in the learning styles of CEP and ES students, there was a consistent preference for concreteness when gaining experience. This may indicate that educational approaches (such as ‘flipped classrooms’) are suitable and may even be preferred, in this context.

Conclusion

In the first formal exploration of Australian ES and CEP student learning styles, it was identified that Accommodators were the most common learning style in this cohort. Furthermore, there was a preference for students for concreteness over abstractness when gaining experience, and for action over reflection when transferring this experience into knowledge. These findings may suggest that modern flipped classroom approaches are suitable to the learning styles of ES and CEO students, as long as they are implemented with opportunity to experience skill learning in a direct hands-on manner, and observe others do the same, allowing time for reflection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bakon, S, M. Christensen, and J. A. Craft. 2016. An Exploration of the Relationship Between Nursing students’ Learning Style and Success in Biosicence Education: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Networking for Education in Healthcare.

- Bergsteiner, H, G. C. Avery, and R. Neumann. 2010. “Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model: Critique from a Modelling Perspective.” Studies in Continuing Education 32 (1): 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01580370903534355

- Brown, T, T. Cosgriff, and G. French. 2008. “Learning Style Preferences of Occupational Therapy, Physiotherapy and Speech Pathology Students: A Comparative Study.” Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences & Practice 6 (3): 7. https://doi.org/10.46743/1540-580X/2008.1204

- Brown, T, M. Zoghi, B. Williams, S. Jaberzadeh, L. Roller, C. Palermo, L. McKenna, C. Wright, M. Baird, and M. Schneider-Kolsky. 2009. “Are Learning Style Preferences of Health Science Students Predictive of Their Attitudes Towards E-Learning?” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 25 (4). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1127

- Bryant, P, S. Hartley, W. Coppola, A. Berlin, M. Modell, and E. Murray. 2003. “Clinical Exposure During Clinical Method Attachments in General Practice.” Medical Education 37 (9): 790–793. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01597.x

- Burkhart, S. J, J. A. Taylor, M. Kynn, D. L. Craven, and L. C. Swanepoel. 2020. “Undergraduate Students Experience of Nutrition Education Using the Flipped Classroom Approach: A Descriptive Cohort Study.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 52 (4): 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2019.06.002

- Campos, D. G, M. R. Alvarenga, S. C. Morais, N. Goncalves, T. B. Silva, M. Jarvill, and A. R. Oliveira Kumakura. 2022. “A Multi‐Centre Study of Learning Styles of New Nursing Students.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 31 (1–2): 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15888

- Carrard, J, M. Gut, I. Croci, S. McMahon, B. Gojanovic, T. Hinrichs, and A. Schmidt-Trucksäss. 2022. “Exercise Science Graduates in the Healthcare System: A Comparison Between Australia and Switzerland.” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 4:766641. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.766641

- Castro, M. D. B, and G. M. Tumibay. 2021. “A Literature Review: Efficacy of Online Learning Courses for Higher Education Institution Using Meta-Analysis.” Education and Information Technologies 26 (2): 1367–1385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10027-z

- Cheng, F.-F, C.-C. Chiu, C.-S. Wu, and D.-C. Tsaih. 2017. “The Influence of Learning Style on Satisfaction and Learning Effectiveness in the Asynchronous Web-Based Learning System.” Library Hi Tech 35 (4): 473–489. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-12-2016-0151

- Dembo, M. H, and K. Howard. 2007. “Advice About the Use of Learning Styles: A Major Myth in Education.” Journal of College Reading & Learning 37 (2): 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2007.10850200

- Deng, R, P. Benckendorff, and Y. Gao. 2022. “Limited Usefulness of Learning Style Instruments in Advancing Teaching and Learning.” The International Journal of Management Education 20 (3): 100686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100686

- DiBartola, L. M 2006. “The Learning Style Inventory Challenge: Teaching About Teaching by Learning About Learning.” Journal of Allied Health 35 (4): 238–245

- DiMuro, P, and M. Terry. 2007. “A Matter of Style: Applying Kolb’s Learning Style Model to College Mathematics Teaching Practices.” Journal of College Reading & Learning 38 (1): 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2007.10850204

- Dobson, J. L 2009. “Learning Style Preferences and Course Performance in an Undergraduate Physiology Class.” Advances in Physiology Education 33 (4): 308–314. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00048.2009

- Drago, W. A, and R. J. Wagner. 2004. “Vark Preferred Learning Styles and Online Education.” Management Research News 27 (7): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170410784211

- ESSA. 2022a. Accredited Exercise Physiologist Scope of Practice. Ascot, Queensland, Australia: Exercise and Sport Science Australia.

- ESSA. 2022b. Accredited Exercise Scientist Scope of Practice. Ascot, Queensland, Australia: Exercise and Sport Science Australia.

- Ewing, L.-A 2021. “Rethinking Higher Education Post COVID-19.” In The Future of Service Post-COVID-19 Pandemic, Volume 1: Rapid Adoption of Digital Service Technology, edited by J. Lee and S. H. Han, 37–54. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4126-5_3

- Felder, R. M 2020. “Opinion: Uses, misuses, and validity of learning styles.” Advances in Engineering Education 8 (1): 1–16

- Finlay, M. J, D. J. Tinnion, and T. Simpson. 2022. “A Virtual versus Blended Learning Approach to Higher Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Experiences of a Sport and Exercise Science Student Cohort.” Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education 30:100363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100363

- French, G, T. Cosgriff, and T. Brown. 2007. “Learning Style Preferences of Australian Occupational Therapy Students.” Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 54 (s1): S58–S65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00723.x

- Fukuta, J, and J. Yamashita. 2021. “The Complex Relationship Between Conscious/Unconscious Learning and Conscious/Unconscious Knowledge: The Mediating Effects of Salience in Form–Meaning Connections.” Second Language Research 39 (2): 425–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/02676583211044950

- Gaines, S. E 2021. A Flipped Classroom Approach in Undergraduate Anatomy and Physiology: A Mixed Methods Study Evaluating Learning Environment and Student Outcomes. Perth, Western Australia, Australia: Curtin University.

- Hauer, P, C. Straub, and S. Wolf. 2005. “Learning Styles of Allied Health Students Using Kolb’s LSI-IIa.” Journal of Allied Health 34 (3): 177–182

- Hew, K. F, and C. K. Lo. 2018. “Flipped Classroom Improves Student Learning in Health Professions Education: A Meta-Analysis.” BMC Medical Education 18 (1): 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z

- Husmann, P. R, and V. D. O’Loughlin. 2019. “Another Nail in the Coffin for Learning Styles? Disparities Among Undergraduate Anatomy students’ Study Strategies, Class Performance, and Reported VARK Learning Styles.” Anatomical Sciences Education 12 (1): 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1777

- Ibrahim, R. H, and D.-A. Hussein. 2016. “Assessment of Visual, Auditory, and Kinesthetic Learning Style Among Undergraduate Nursing Students.” International Journal of Advanced Nursing Studies 5 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijans.v5i1.5124

- John, S 2003. “ABC of Learning and Teaching in Medicine Learning and Teaching in the Clinical Environment.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 326 (7389): 591–594. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7389.591

- Johnson, N, V. Chuter, and K. Rooney. 2013. “Conception of Learning and Clinical Skill Acquisition in Undergraduate Exercise Science Students: A Pilot Study.” Advances in Physiology Education 37 (1): 108–111. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00044.2012

- Katz, N, and N. Heimann. 1991. “Learning Style of Students and Practitioners in Five Health Professions.” The Occupational Therapy Journal of Research 11 (4): 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/153944929101100404

- Kazeminia, M, L. Salehi, M. Khosravipour, and F. Rajati. 2022. “Investigation Flipped Classroom Effectiveness in Teaching Anatomy: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Professional Nursing 42:15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2022.05.007

- Keefe, J. W 1979. “Learning Style: An Overview.” Student Learning Styles: Diagnosing and Prescribing Programs 1 (1): 1–17

- Keogh, J. W. L, L. Gowthorp, and M. McLean. 2017. “Perceptions of Sport Science Students on the Potential Applications and Limitations of Blended Learning in Their Education: A Qualitative Study.” Sports Biomechanics 16 (3): 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2017.1305439

- Kilminster, S. M, and B. C. Jolly. 2000. “Effective Supervision in Clinical Practice Settings: A Literature Review.” Medical Education 34 (10): 827–840. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00758.x

- Kolb, A. Y 2005. “The Kolb Learning Style Inventory-Version 3.1 2005 Technical Specifications.” Boston, MA 200 (72): 166–171

- Kolb, D. A 2014. Experiential Learning: Experience As the Source of Learning and Development. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, United States: FT press.

- Koohestani, H. R, and N. Baghcheghi. 2020. “A Comparison of Learning Styles of Undergraduate Health-Care Professional Students at the Beginning, Middle, and End of the Educational Course Over a 4-Year Study Period (2015–2018).” Journal of Education and Health Promotion 9 (1): 208. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_224_20

- Kurtuluş, Ö 2022. “Investigation of Sports Science Undergraduate students’ Epistemological Beliefs for Learning and Their Learning Styles.” International Journal of Education Technology and Scientific Researches 7 (19): 1672–1717

- Liu, Q, W. Peng, F. Zhang, R. Hu, Y. Li, and W. Yan. 2016. “The Effectiveness of Blended Learning in Health Professions: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 18 (1): e2. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4807

- Manolis, C, D. J. Burns, R. Assudani, and R. Chinta. 2013. “Assessing Experiential Learning Styles: A Methodological Reconstruction and Validation of the Kolb Learning Style Inventory.” Learning and Individual Differences 23:44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.10.009

- Marques-Sule, E, J. L. Sánchez-González, J. J. Carrasco, S. Pérez-Alenda, T. Sentandreu-Mañó, N. Moreno-Segura, N. Cezón-Serrano, R. Ruiz de Viñaspre-Hernández, R. Juárez-Vela, and E. Muñoz-Gómez. 2023. “Effectiveness of a Blended Learning Intervention in Cardiac Physiotherapy. A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Frontiers in Public Health 11:1145892. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1145892

- McLeod, S, M. Lincoln, L. McAllister, D. Maloney, A. Purcell, and P. Eadie. 1995. “A Longitudinal Investigation of Reported Learning Styles of Speech Pathology Students.” Australian Journal of Human Communication Disorders 23 (2): 13–25. https://doi.org/10.3109/asl2.1995.23.issue-2.02

- McNally, B, J. Chipperfield, P. Dorsett, L. Del Fabbro, V. Frommolt, S. Goetz, J. Lewohl, et al. 2017. “Flipped Classroom Experiences: Student Preferences and Flip Strategy in a Higher Education Context.” Higher Education 73 (2): 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0014-z

- Milanese, S, S. Gordon, and A. Pellatt. 2013. “Profiling Physiotherapy Student Preferred Learning Styles within a Clinical Education Context.” Physiotherapy 99 (2): 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2012.05.004

- Newton, S, and R. Wang. 2022. “What the Malleability of Kolb’s Learning Style Preferences Reveals About Categorical Differences in Learning.” Educational Studies 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2021.2025044

- Pashler, H, M. McDaniel, D. Rohrer, and R. Bjork. 2008. “Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 9 (3): 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

- Peters, D, G. Jones, and J. Peters. 2008. “Preferred ‘Learning styles’ in Students Studying Sports‐Related Programmes in Higher Education in the United Kingdom.” Studies in Higher Education 33 (2): 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070801916005

- Quinn, M. M, T. Smith, E. L. Kalmar, and J. M. Burgoon. 2018. “What Type of Learner Are Your Students? Preferred Learning Styles of Undergraduate Gross Anatomy Students According to the Index of Learning Styles Questionnaire.” Anatomical Sciences Education 11 (4): 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1748

- Rapanta, C, L. Botturi, P. Goodyear, L. Guàrdia, and M. Koole. 2020. “Online University Teaching During and After the COVID-19 Crisis: Refocusing Teacher Presence and Learning Activity.” Postdigital Science and Education 2 (3): 923–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y

- Romanelli, F, E. Bird, and M. Ryan. 2009. “Learning Styles: A Review of Theory, Application, and Best Practices.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 73 (1): 9. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj730109

- Sajid, M. R, A. F. Laheji, F. Abothenain, Y. Salam, D. AlJayar, and A. Obeidat. 2016. “Can Blended Learning and the Flipped Classroom Improve Student Learning and Satisfaction in Saudi Arabia?” International Journal of Medical Education 7:281–285. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.57a7.83d4

- Shumba, T. W, and S. N. Iipinge. 2019. “Learning Style Preferences of Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Systematic Review.” Africa Journal of Nursing and Midwifery 21 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.25159/2520-5293/5758

- Soan, E. J, S. J. Street, S. M. Brownie, and A. P. Hills. 2014. “Exercise Physiologists: Essential Players in Interdisciplinary Teams for Noncommunicable Chronic Disease Management.” Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 7:65–68. https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.S55620

- Stander, J, K. Grimmer, and Y. Brink. 2019. “Learning Styles of Physiotherapists: A Systematic Scoping Review.” BMC Medical Education 19 (1): 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1434-5

- Stevens, C. J, A. Lawrence, M. A. Pluss, and S. Nancarrow. 2018. “The Career Destination, Progression, and Satisfaction of Exercise and Sports Science Graduates in Australia.” Journal of Clinical Exercise Physiology 7 (4): 76–81. https://doi.org/10.31189/2165-6193-7.4.76

- Strelan, P, A. Osborn, and E. Palmer. 2020. “The Flipped Classroom: A Meta-Analysis of Effects on Student Performance Across Disciplines and Education Levels.” Educational Research Review 30:100314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100314

- Vallée, A, J. Blacher, A. Cariou, and E. Sorbets. 2020. “Blended Learning Compared to Traditional Learning in Medical Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [Review].” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (8): e16504. https://doi.org/10.2196/16504

- van Alten, D. C. D, C. Phielix, J. Janssen, and L. Kester. 2019. “Effects of Flipping the Classroom on Learning Outcomes and Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Research Review 28:100281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.05.003

- Villanueva, F 2020. “The Use of Kolb’s Learning Styles Inventory (LSI) in School Settings.” Bu Journal of Graduate Studies in Education 12 (1): 42–45

- Wagner, M. G, P. Hansen, Y. Rhee, A. Brundt, D. Terbizan, and B. Christensen. 2014. “Learning Style Preferences of Undergraduate Dietetics, Athletic Training, and Exercise Science Students.” Journal of Education and Training Studies 2 (2): 198–205. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v2i2.331

- Wehrwein, E. A, H. L. Lujan, and S. E. DiCarlo. 2007. “Gender Differences in Learning Style Preferences Among Undergraduate Physiology Students.” Advances in Physiology Education 31 (2): 153–157. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00060.2006

- Wessel, J, J. Loomis, S. Rennie, P. Brook, J. Hoddinott, and M. Aherne. 1999. “Learning Styles and Perceived Problem-Solving Ability of Students in a Baccalaureate Physiotherapy Programme.” Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 15 (1): 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/095939899307865

- Wessel, J, and R. Williams. 2004. “Critical Thinking and Learning Styles of Students in a Problem-Based, master’s Entry-Level Physical Therapy Program.” Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 20 (2): 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593980490453039

- Zoghi, M, T. Brown, B. Williams, L. Roller, S. Jaberzadeh, C. Palermo, L. McKenna, C. Wright, M. Baird, and M. Schneider-Kolsky. 2010. “Learning Style Preferences of Australian Health Science Students.” Journal of Allied Health 39 (2): 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1108/17581184201000006