Abstract

Since its first appearance in the early Miocene, the cheilostome bryozoan genus Microporella has been cosmopolitan, recorded from most continents. However, Miocene Microporella records in New Zealand are scarce, and currently limited to a single middle Miocene species identified as Microporella hyadesi (a Recent bifoliate erect form originally described from Cape Horn and Tierra del Fuego) from the Mt. Brown ‘E’ Limestone Formation of North Canterbury. Here, we describe and illustrate three new early Miocene (Otaian–Altonian New Zealand stages corresponding to the Aquitanian–Burdigalian) species, namely Microporella incurvata sp. nov., M. gladirostra sp. nov. and M. whiterocki sp. nov., that represent the geologically oldest regional examples of the genus to date. A fourth species is left in open nomenclature because complete ovicells are not preserved in the only recovered specimen. The colonies of Microporella were collected from several rock formations exposed in limestone quarries on the South Island. The three new species share ovicells with a personate structure, but differ in the appearance of the ooecial surface (evenly pseudoporous versus imperforate), shape of the ascopore opening (cribrate versus non-cribrate), number of oral spine bases, and shape of the avicularian rostrum and crossbar. We also illustrate for the first time ovicells of another fossil species, Microporella rusti, from the Pleistocene Nukumaru Limestone Formation of the Wanganui Basin on the North Island. The ovicells of this taxon are rare, being found in only six of several hundred specimens collected to date. The ovicells of M. rusti are also very large, covering the entire orifice of the maternal zooid, similar to those of some other Microporella species all characterized by erect bifoliate colonies contrasting with the encrusting colonies of M. rusti.

http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5430969F-B75B-40E7-8F65-74CDC87AA662

Mali H. Ramsfjell [[email protected]] Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, Blindern, PO Box 1172, Oslo 0318, Norway; Paul D. Taylor [[email protected]] Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD, UK; Emanuela Di Martino [[email protected]] Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, Blindern, PO Box 1172, Oslo 0318, Norway.

MICROPORELLA Hincks, Citation1877 is a species-rich genus of cheilostome bryozoans that is cosmopolitan across both hemispheres from polar to tropical/equatorial latitudes, and occurs at all depths from the intertidal to the bathyal zone (Taylor & Mawatari Citation2005). Microporella species form encrusting colonies, spot-, sheet- or runner-like, or erect branching colonies, flat bilamellar or cylindrical, on hard, long-lasting substrates, such as rocks, shells and other skeletal parts, or on soft, ephemeral substrates such as algae and seagrasses (e.g., Di Martino et al. Citation2020, Di Martino & Rosso Citation2021).

The oldest confirmed fossil records of Microporella are known from the lower Miocene, with putative upper Oligocene fossils representing generic misidentifications or stratigraphical errors (e.g., Canu Citation1904). As soon as it appeared about 23 million years ago (Ma), Microporella was successful worldwide, with early Miocene species recorded on most continents.

Eight species of Microporella have their type occurrences in New Zealand: Microporella agonistes Gordon, Citation1984; Microporella discors Uttley & Bullivant, Citation1972; Microporella intermedia Livingstone, Citation1929; Microporella lingulata Di Martino, Taylor & Gordon, Citation2020; Microporella ordo Brown, Citation1952; Microporella ordoides Di Martino, Taylor & Gordon, Citation2020; Microporella rusti Di Martino, Taylor, Gordon & Liow, Citation2017; and Microporella speculum Brown, Citation1952. These range from Pleistocene to Recent, except for M. lingulata and M. ordoides which are reported only from Recent samples (Di Martino et al. Citation2020), and M. rusti which has only been identified from lower Pleistocene rocks (Di Martino et al. Citation2017). Brown (Citation1952) documented possible specimens of Microporella hyadesi (Jullien, Citation1888) from the middle Miocene basal uppermost Mt. Brown ‘E’ Limestone of Waipara in North Canterbury (see also Di Martino et al. Citation2017). However, this is a Recent subantarctic species described from Cape Horn and Tierra del Fuego; M. hyadesi sensu Brown (Citation1952) otherwise seems to be a distinct species that shares features with both M. hyadesi (i.e., a very large personate ovicell) and M. ordo (i.e., a cribrate ascopore).

In this paper, we describe three new species of Microporella from Otaian–Altonian (= Aquitanian and/or Burdigalian) localities on the South Island of New Zealand. These represent the earliest records of the genus from the region. A fourth species is also documented but left in open nomenclature because of inadequate preservation of diagnostic characters. We also report the first known ovicells from the Pleistocene species M. rusti present in six colonies from the Nukumaru Limestone Formation of the Wanganui Basin on the North Island.

Material and methods

Our fossil specimens were collected from: the White Rock Limestone Formation (Otaian = Aquitanian or Burdigalian) in the White Rock Limestone Quarry near the Karetu River of North Canterbury by PDT and David MacKinnon (University of Canterbury, New Zealand) in 1999; the Clifden Limestone Formation (Altonian = Burdigalian) at Clifden Quarry in Southland by PDT in 1988; the Forest Hill Limestone Formation (Altonian = Burdigalian) at the Centre Bush Quarry near Winton in Southland by PDT in 1988; and at the nearby Fernhill and Lady Barkly quarries by Kevin Tilbrook (formerly Museum of Tropical Queensland, Australia) in 1995. All of the recovered colonies encrust biotic hard substrates, such as bivalve (mainly oysters and pectinids) and brachiopod shells, and more often the undersides of large colonies of the cheilostome bryozoan Celleporaria emancipata Gordon, Citation1989. Ovicellate colonies of M. rusti were collected by the authors in February 2020 from the Pleistocene (∼2.3 Ma) Nukumaru Limestone Formation at Waiinu Beach west of the city of Whanganui.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted on uncoated specimens using a JEOL IT500 microscope operated at low-vacuum and back-scattered electron mode at the Natural History Museum London, United Kingdon (NHMUK). Morphometric measurements () were taken from SEM images using ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/): AvL, avicularium length; AvW, avicularium width; OL, orifice length; OW, orifice width; OvL, ovicell length; OvW, ovicell width; ZL, autozooid length; ZW, autozooid width.

Table 1. Measurements in µm of Microporella incurvata sp. nov.

Table 2. Measurements in µm of Microporella gladirostra sp. nov.

Table 3. Measurements in µm of Microporella whiterocki sp. nov.

Table 4. Measurements in µm of Microporella sp. A.

All type and figured specimens are deposited in the collections of the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences in Lower Hutt, New Zealand (GNS). Unregistered specimens are housed in the bryozoan palaeontological collection of the NHMUK.

Systematic palaeontology

Phylum BRYOZOA Ehrenberg, Citation1831

Class GYMNOLAEMATA Allman, Citation1856

Order CHEILOSTOMATIDA Busk, Citation1852

Superfamily SCHIZOPORELLOIDEA Jullien, Citation1883

Family MICROPORELLIDAE Hincks, Citation1879

Genus MICROPORELLA Hincks, Citation1877

Microporella incurvata sp. nov.

(; )

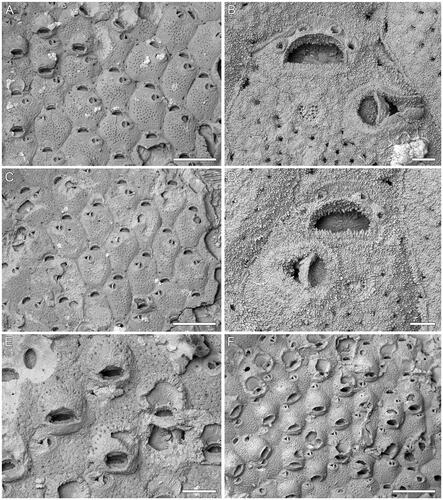

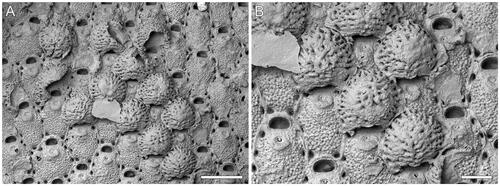

Figure 1. Microporella incurvata sp. nov. A, B, Holotype GNS BZ 342 Miocene (Altonian = Burdigalian), Clifden Limestone Formation, Clifden Quarry, Southland, New Zealand. A, Group of autozooids, some ovicellate (scale bar = 500 µm); B, close-up of orifice, showing four distolateral oral spines, cribrate ascopore and avicularium with bent crossbar (scale bar = 50 µm); C–E, Paratype GNS BZ 343, same details as holotype. C, Group of autozooids (scale bar = 500 µm); D, close-up of orifice and avicularium (scale bar = 50 µm); E, close-up of ovicellate zooids (scale bar = 200 µm). F, Paratype GNS BZ 344, Miocene (Otaian = Aquitanian or Burdigalian), White Rock Limestone Formation, White Rock Limestone Quarry, Karetu River, North Canterbury, New Zealand. Group of ovicellate zooids (scale bar = 500 µm).

Diagnosis

Microporella with personate ovicell encircling the orifice but not the ascopore; ooecium imperforate except for one or two peripheral rows of marginal pseudopores; four distal oral spines; cribrate ascopore; avicularium with curved crossbar and triangular rostrum directed laterally.

Etymology

From the Latin incurvatus, meaning ‘bent over’; referring to the curved crossbar of the avicularium.

Holotype

GNS BZ 342 ().

Referred material

Paratypes: GNS BZ 343 (); GNS BZ 344 (). Additional unregistered colony from Clifden Quarry; 11 unregistered colonies from the White Rock Limestone Quarry.

Type localities, units and ages

Holotype and one of the paratypes are from the Clifden Quarry in Southland, New Zealand, FR Number D45/f0429; Clifden Limestone Formation, lower Miocene (Altonian = Burdigalian; 18.7–15.9 Ma). The remaining paratype is from the White Rock Limestone Quarry near the Karetu River in North Canterbury, New Zealand, FR Number M34/f0884; White Rock Limestone Formation, lower Miocene (Otaian = Aquitanian or Burdigalian; 21.7–18.7 Ma).

Description

Colony encrusting, multiserial, unilaminar (); interzooidal communications through slit-like pore-chamber windows, usually visible at colony growing edge, one on each side of the distolateral vertical walls, 32–90 µm long, and two on the corners of the distal vertical wall, 16–58 µm long.

Autozooids rounded hexagonal, longer than wide (mean L/W = 1.22), with distinct boundaries marked by narrow grooves between a thin raised rim of calcification ().

Frontal shield flat to slightly convex, nodular and finely granular; 36–52 circular pseudopores, 7–12 µm in diameter, placed centrally; 2–5 subcircular to elliptical marginal areolar pores, 17–52 µm in diameter, sometimes visible at zooidal corners ().

Orifice transversely D-shaped with straight hinge-line (). Consistently four distolateral oral spine bases, 26–33 µm in diameter.

Ascopore field heart-shaped, 55–73 × 59–86 µm, at the same level or slightly beneath the adjacent frontal shield, ca 50 µm from the orifice hinge-line, outlined by a narrow band of gymnocystal calcification; ascopore opening transversely C-shaped, cribrate (), 6–15 × 34–46 µm.

Avicularium single, present in the majority of autozooids, placed distolaterally, on either side, at about two-thirds of zooidal length, proximal margin at the same level as that of the ascopore; rostrum triangular, channelled with open end, directed laterally or slightly distolaterally; crossbar complete and curved ().

Ovicell subglobular, occupying about one-third of the frontal shield of the next distal zooid; personate with peristome encircling the orifice, but not including the ascopore, forming an eye-shaped secondary orifice (); no spines visible in ovicellate zooids; ooecium surface nodular and granular like zooidal frontal shield, imperforate except for one or two row of marginal pseudopores (, upper centre ooecium).

Ancestrula was not observed.

Remarks

Amongst the species of Microporella bearing personate ovicells, Microporella incurvata most closely resembles the Recent Microporella ‘diademata’ sensu Gordon (Citation1989, pl. 31B) from Puysegur Bank in having a largely imperforate ooecium with only a peripheral row of pseudopores. It differs in its cribrate ascopore (lunate, with a thin non-denticulate rim in M. ‘diademata’) and fewer oral spines (four versus five or six). In addition, the proximal-most pair of spines are visible in the ovicellate zooids of M. ‘diademata’ at the proximolateral corners of the peristome, while spines are entirely hidden in M. incurvata. The nominal species M. diademata (Lamouroux, Citation1825) described from the Falkland Islands is likely to be a senior synonym of M. personata (Busk, Citation1854) (Smitt Citation1873, Brown Citation1952, Gordon Citation1989), and distinct from the putative M. ‘diademata’ found in New Zealand (D. Gordon, pers. comm., March 2022). Brown (Citation1952) designated the Busk (Citation1854) M. personata specimen as the neotype of M. diademata after failing to find the type material at the Institut Botanique, Université de Caen, France. However, both taxa occur in the same geographic area, and based on the original descriptions, are very similar in appearance with minor differences in the number of oral spines likely due to intraspecific variability. Lamouroux (Citation1825, p. 609, pl. 89, fig. 4) described and figured seven to eight oral spines, while Busk (Citation1854, p. 74) described five to seven spines. Gordon’s (Citation1989) putative M. ‘diademata’ is otherwise geographically distinct, being sampled from deeper waters (215–549 m versus 7–10 m) and possessing a spine number that never exceeds six. However, a more detailed comparison is needed following the re-examination of both the neotype of M. diademata and the New Zealand specimens. Serration of the hinge-line observed in some zooids of M. incurvata is interpreted as diagenetic rather than a morphological feature.

Microporella gladirostra sp. nov.

(; )

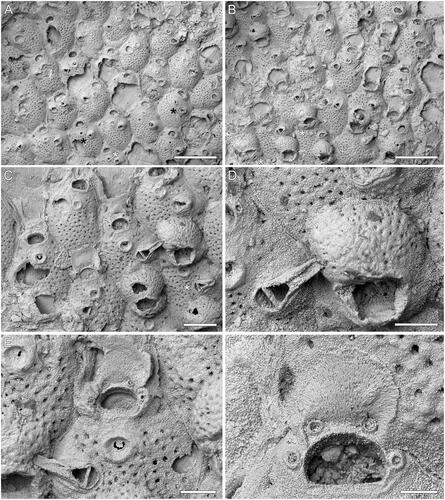

Figure 2. Microporella gladirostra sp. nov. A–D, Holotype GNS BZ 345, Miocene (Otaian = Aquitanian or Burdigalian), White Rock Limestone Formation, White Rock Limestone Quarry, Karetu River, North Canterbury, New Zealand. A, B, Groups of autozooids, some ovicellate, with most commonly four and exceptionally five (see black asterisks in A) and six (see white asterisk in A) oral spine bases (scale bars = 500 µm). Asterisks in B indicate zooids with pores in the proximal peristome. C, Close-up of autozooids, two of which with complete ooecium. The zooid in the centre shows an avicularium with the long, slender rostrum preserved, while the zooid on the bottom right (see asterisk) shows an intramural budded avicularium (scale bar = 200 µm). D, Close-up of ovicell and avicularium (scale bar = 100 µm). E, F, Paratype GNS BZ 346, same details as holotype. E, Close-up of ascopore, orifice with four oral spine bases and avicularium (scale bar = 100 µm); F, close-up of an orifice showing the smooth proximal margin (scale bar = 50 µm).

Diagnosis

Microporella with personate ovicell encircling the orifice but not the ascopore; ooecium evenly pseudoporous; smooth proximal margin of the orifice; 4–6 oral spines; ascopore with projecting tongue and radial denticulations; avicularium with elongate triangular rostrum directed laterally or distolaterally.

Etymology

From the Latin gladius, meaning ‘sword’, and rostrum for ‘beak’; referring to the elongate triangular shape of the avicularium rostrum that resembles the blade of a sword.

Holotype

GNS BZ 345 ().

Referred material

Paratype: GNS BZ 346 (). Other unregistered material includes eight colonies from the type locality; four colonies from the Fernhill Quarry; and two colonies from the Centre Bush Quarry.

Type localities, units and ages

Type locality is the White Rock Limestone Quarry near the Karetu River in North Canterbury, New Zealand, FR Number M34/f0884; White Rock Limestone Formation, lower Miocene (Otaian = Aquitanian or Burdigalian; 21.7–18.7 Ma). Four unregistered specimens are from the Fernhill Quarry, FR Number E46/f0061; Forest Hill Limestone Formation, lower Miocene (Altonian = Burdigalian); two additional unregistered colonies are from the Centre Bush Quarry, FR Number E46/f0061; Forest Hill Limestone Formation, Miocene (Altonian = Burdigalian).

Description

Colony encrusting, multiserial, unilaminar (); interzooidal communications through slit-like pore-chamber windows, usually visible on the lateral vertical walls of zooids at colony growing edge (), one on each side distolaterally, 54–96 µm long, and two smaller, 30–50 µm long, distally, one at each corner.

Autozooids rounded hexagonal, longer than wide (mean L/W = 1.32), with distinct boundaries marked by narrow grooves between a thin raised rim of calcification ().

Frontal shield slightly convex, nodular and finely granular; evenly and densely pseudoporous except for the area between orifice and ascopore, with 37–78 circular pseudopores, 6–13 µm in diameter (); 1–4 subcircular to elliptical marginal areolar pores, 24–59 µm in diameter, sometimes visible at zooidal corners ().

Orifice transversely D-shaped with straight, smooth hinge-line (). Four (more commonly) to six distolateral oral spine bases (; note that in (A) zooids with five spines are indicated with black asterisks and the zooid with six spines is indicated with a white asterisk), 19–26 µm in diameter.

Ascopore field funnel-shaped outlined by a raised, circular (61–89 × 66–93 µm) rim of smooth gymnocyst, placed ca 45 µm from the orifice hinge-line; ascopore opening depressed in relation to the adjacent frontal shield, transversely C-shaped, 3–9 × 22–36 µm, with a denticulate, semielliptical tongue projected from the distal edge and small radial denticles ().

Avicularium single, present in the majority of autozooids, placed laterally at about zooidal mid-length, on either side. Rostrum elongate triangular, long and thin, channelled with open end, directed laterally or slightly distolaterally (); crossbar complete. Intramural buds common in avicularia ().

Ovicell subglobular, occupying about one-third of the frontal shield of the distal zooid; personate with peristome encircling the orifice, but not including the ascopore, forming a variably shaped secondary orifice either quadrangular or eye-shaped; ooecium evenly pseudoporous, nodular and granular as for the zooidal frontal shield (); the peristome often with a central proximal pore or two smaller proximolateral pores ( see asterisks, ); no spines visible in ovicellate zooids.

Ancestrula was not observed.

Remarks

Microporella gladirostra differs from Microporella incurvata in having evenly pseudoporous ooecia and non-cribrate ascopores. The avicularia are also different, being characterized by a long and thin rostrum in M. gladirostra, versus a curved crossbar in M. incurvata. The peristome of ovicellate zooids has a different proximal shape in these species, being squared in M. gladirostra and arched in M. incurvata. In addition, the ooecium is more globular in M. gladirostra.

Amongst those species with personate ovicells, M. gladirostra mostly closely resembles the Recent Microporella browni Harmelin, Ostrovsky, Cáceres-Chamizo & Sanner, Citation2011 in having a centrally pseudoporous ooecium, transversely C-shaped ascopore opening lined with denticles, and four to five oral spines (although exceptionally up to six spines may be present). Microporella gladirostra differs from M. browni in having a more elongate avicularian rostrum indenting the ooecia of adjacent zooids (; see also fig. 2B of Harmelin et al. Citation2011 for comparison), and a smooth, straight orifice hinge-line that lacks condyles (the hinge-line is otherwise corrugated with two lateral shoulder-shaped condyles in M. browni).

Similar pseudoporous ooecia are also known in Microporella orientalis Harmer, Citation1957 and Microporella personata Busk, Citation1854. In addition to the shape of the avicularian rostrum, M. gladirostra differs from M. orientalis in having ascopores with a more extensive, semi-elliptical tongue projecting from the distal edge (these are alternatively smaller and almost triangular in M. orientalis: see Tilbrook Citation2006, pl. 45B), and from M. personata in having fewer oral spines (four to five versus five to seven), none of which are visible in the ovicellate zooids (only two are visible in M. personata at the inner corners of the peristome).

The granulation of the frontal shield as well as the denticulations observed on the inner distal margin of the orifice of some zooids of M. gladirostra might be diagenetic rather than original features. The raised ascopore rim often seen in fossil colonies of Microporella might also be an artefact due to the dissolution of the aragonitic outer parts of the frontal shields. However, raised ascopore rims were also described in Recent species, such as in Microporella dentilingua Tilbrook, Citation2006 (see Tilbrook Citation2006, p. 210, fig. 45E, F), and in M. appendiculata (Heller, Citation1867) (see Di Martino & Rosso Citation2021, p. 7, fig. 2E, F).

Microporella whiterocki sp. nov.

(; )

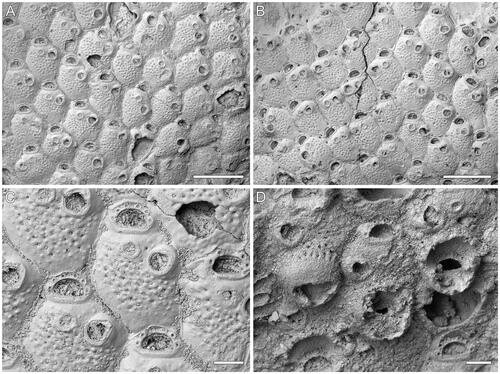

Figure 3. Microporella whiterocki sp. nov. A–C, Holotype GNS BZ 347, Miocene (Otaian = Aquitanian or Burdigalian), White Rock Limestone Formation, White Rock Limestone Quarry, Karetu River, North Canterbury, New Zealand. A, B, Group of autozooids, those at the colony growth edge showing basal pore-chamber windows (scale bars = 500 µm); C, close-up of autozooids showing six oral spine bases and drop-shaped avicularia (scale bar = 100 µm). D, Paratype GNS BZ 348, same details as holotype. Close-up of ovicellate zooids, only one ooecium complete (scale bar = 100 µm).

Diagnosis

Microporella with personate ovicell encircling the orifice but not the ascopore; ooecium imperforate except for a row of slit-like marginal pseudopores; consistently six oral spines; drop-shaped avicularium with raised rostrum directed distolaterally.

Etymology

Referring to the White Rock Limestone Formation from which colonies of this species were collected.

Holotype

GNS BZ 347 (), colony encrusting a brachiopod shell.

Referred material

Paratype: GNS BZ 348 (), colony encrusting a brachiopod shell.

Type locality, unit and age

White Rock Limestone Quarry near the Karetu River in North Canterbury, New Zealand, FR Number M34/f0884; White Rock Limestone Formation, lower Miocene (Otaian = Aquitanian or Burdigalian; 21.7–18.7 Ma).

Description

Colony encrusting, multiserial, unilaminar (); interzooidal communications through slit-like pore-chamber windows, usually visible on the lateral vertical walls of zooids at colony growing edge, one distolaterally on each side, 57–104 µm long, and one centrally placed, or two smaller windows, 18–57 µm long, located at each corner, distally (, see zooids at the top-left and top-right).

Autozooids rounded hexagonal, longer than wide (mean L/W = 1.25), with distinct boundaries marked by narrow grooves between a thin raised rim of calcification ().

Frontal shield flat to slightly convex, smooth and imperforate along zooidal margins, coarsely granular and pseudoporous centrally (); 31–48 circular pseudopores, 8–11 µm in diameter; up to four subcircular to elliptical marginal areolar pores, 22–54 µm in diameter, sometimes visible, two proximolaterally and two laterally at the level of the proximal orificial margin.

Orifice transversely D-shaped with straight hinge-line. Consistently six oral spine bases, 18–31 µm in diameter, evenly spaced, starting slightly above the orifice proximal margin ().

Ascopore field circular, 59–87 × 61–92 µm, at the same level or slightly beneath the adjacent frontal shield, ca 35 µm from the orifice hinge-line, outlined by a narrow band of gymnocystal calcification (); ascopore opening poorly preserved, seemingly cribrate.

Avicularium single, present in the majority of autozooids, placed laterally on the right or left side at about two-thirds of zooid length, drop-shaped (); rostrum rounded triangular, slightly raised distally on a smooth cystid, distal end closed, directed distolaterally; crossbar complete.

Ovicells subglobular, occupying about one-third of the frontal shield of the distal zooid; personate with peristome encircling the orifice, but not including the ascopore; no spines visible in ovicellate zooids; ooecium finely granular, imperforate except for a row of slit-like marginal pseudopores (), 144 µm long by 240 µm wide.

Ancestrula was not observed.

Remarks

Amongst the Miocene congeners we describe here, Microporella whiterocki mostly resembles Microporella incurvata in having a personate ovicell, which is imperforate except for a peripheral row of pores. Differences include six oral spine bases instead of four, and a straight rather than curved avicularian crossbar. The general shape of the avicularium is also different. The imperforate ooecium is shared with the putative M. ‘diademata’ sensu Gordon (Citation1989), which differs in its proportionally smaller ascopore field compared to autozooid size. Additional differences include the distribution of pseudopores and granules on the frontal shield (more evenly distributed in M. ‘diademata’), but this might be a diagenetic artefact.

Microporella sp. A

(; )

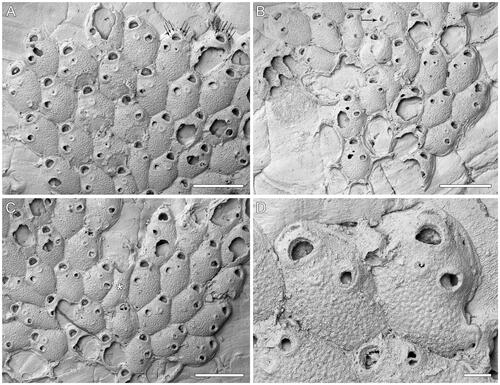

Figure 4. Microporella sp. A. GNS BZ 349, Miocene (Altonian = Burdigalian), Forest Hill Limestone Formation, Lady Barkly Quarry, Southland, New Zealand. A–C, Groups of autozooids from different areas of the colony (scale bars = 500 µm); A, arrows indicate the six distolateral oral spine bases; B, a teratology (top centre), consisting of an autozooid with two avicularia budded on the same side (arrowed); C, a putative kenozooid without openings is present (see asterisk). D, Close-up of two autozooids showing the ascopore (scale bar = 100 µm).

Referred material

GNS BZ 349, colony on the underside of Celleporaria emancipata.

Locality, unit and age

Lady Barkly Quarry in Southland, New Zealand, FR Number E45/f0377; Forest Hill Limestone Formation, lower Miocene (Altonian = Burdigalian).

Description

Colony encrusting, multiserial, unilaminar (); interzooidal communications through slit-like pore-chamber windows, usually visible on the lateral vertical walls of zooids at colony growing edge (), two on each side and one or two distally, 22–67 µm long.

Autozooids rounded hexagonal, longer than wide (mean L/W = 1.58), with distinct boundaries marked by narrow grooves ().

Frontal shield slightly convex, nodular; a few (10–21) scattered, circular pseudopores visible centrally, mostly likely originally more numerous but obliterated by diagenetic cement growth (); subcircular to elliptical marginal areolar pores, 17–38 µm in maximum diameter, visible sometimes at proximal zooidal corners ().

Orifice transversely D-shaped with straight hinge-line (). Consistently six distolateral oral spine bases ( arrowed, ), 18–30 µm in diameter.

Ascopore field circular, 44–75 × 46–70 µm, slightly depressed relative to the adjacent frontal shield, placed ca 40 µm from the orifice hinge-line, outlined by a narrow band of gymnocystal calcification slightly sloping inwards; ascopore opening transversely C-shaped, with a small, semielliptical, distally projecting tongue, denticles few or lacking (), 6 × 20–30 µm.

Avicularium single, present in the majority of autozooids, placed distolaterally on the left or right side, at about two-thirds of zooidal length; rostrum triangular, channelled with open end, directed distolaterally; crossbar complete and undulate ().

Complete ovicell not observed; outline of the ooecial basal surface elliptical, 163–216 µm long by 226–278 µm wide, extending over about one-third of the frontal shield of the distal zooid; a row of peripheral pseudopores visible in the preserved portion of a mostly destroyed ooecium ().

Kenozooids observed, with frontal shields similar to those of autozooids but without openings or avicularia ().

Ancestrula was not observed.

Remarks

Although likely a new species, we prefer to leave Microporella sp. A in open nomenclature because it lacks preserved ovicells in the only available colony. Kenozooids and teratologies (= autozooids with paired avicularia, one of which is sub-centrally placed on the frontal shield) were observed on a damaged section of the colony (). These are probably related to colony repair either via budding of heterozooids or through intramural budding, as seen in other fossil and Recent species of Microporella (Di Martino et al. Citation2019, Citation2020, Di Martino & Rosso Citation2021).

The broken remains () show that the ooecium of Microporella sp. A might be similar to those of Microporella incurvata and Microporella whiterocki in being imperforate with a row of peripheral pores. However, Microporella sp. A differs from M. incurvata in having an ascopore with a transversely C-shaped opening lined with denticles (cribrate in M. incurvata), and six oral spines (versus four in M. incurvata). Microporella sp. A differs from M. whiterocki in having more elongate zooids, and smaller ascopore field and avicularia.

Microporella sp. A has a similar ascopore to that of Microporella gladirostra but differs in possessing six, rather than four (more commonly) to six spines. Microporella gladirostra also lacks the row of peripheral pores in the ooecium. The putative Microporella ‘diademata’ sensu Gordon (Citation1989) has a similar ascopore, with few or no denticles, but differs in having avicularium with straight crossbars.

Microporella rusti Di Martino, Taylor, Gordon & Liow, Citation2017

()

Figure 5. Microporella rusti Di Martino, Taylor, Gordon & Liow, Citation2017, GNS BZ 350, Nukumaruan, Pleistocene, Nukumaru Limestone Formation, Waiinu Beach, North Island, New Zealand. A, Group of autozooids, several ovicellate (scale bar = 500 µm). B, Close-up of ovicells (scale bar = 200 µm).

Referred material

GNS BZ 350 (); two additional unregistered colonies.

Locality, unit and age

Waiinu Beach on North Island, New Zealand, FR Number R22/f0270; Nukumaru Limestone, Pleistocene (Nukumaruan).

Remarks

When first described, the absence of ovicells in hundreds of large colonies of M. rusti from several different batches of samples (Rust Citation2009, Di Martino et al. Citation2017) appeared to be a morphological trait. However, subsequent sampling of the Wanganui Basin localities in 2020 has resulted in the discovery of six ovicellate colonies, showing that M. rusti could develop ovicells, although these are rare. The ooecia are globular, non-personate and very large (OvL = 336–447 [384 ± 27]; OvW = 414–524 [473 ± 31]; N = 20, 2). They entirely obscure the orifice and have an undulate proximal margin. The surface is marked by radial ridges with a peripheral row of large pseudopores and a few smaller pseudopores scattered in the furrows between the ridges. Previously, ‘giant’ ovicells entirely obscuring the orifice, and sometimes even the ascopore, were observed in only four species of Microporella with erect bifoliate colonies; these contrast with the encrusting colonies of Microporella rusti. In Microporella hyadesi and Microporella ordoides, the ooecia differ in being personate, while those of Microporella hastigera (Busk, Citation1884) and Microporella ordo are similar but have less marked ridges, more evenly distributed pseudopores, and no size difference between the peripheral and central pores (see Di Martino et al. Citation2020 for comparative images).

Discussion

The three new species of Microporella described here represent the earliest examples of the genus from New Zealand to date. However, other lower Miocene Microporella fossils from New Zealand include representatives of at least two undescribed species occurring on foraminiferal tests in the Waitiiti Formation (Otaian) of Northland, and an anomiid bivalve shell from the Caversham Formation (Altonian) of Otago (S. Rust, pers. comm., November 2021). The new species are distinguished by their shared possession of ovicells displaying a personate structure (= a proximal, collar-like peristome encircling the orifice and sometimes also the ascopore). When first described in Lepralia personata by Busk (Citation1854), personate ovicells were considered as a distinctive character for this species, prompting the specific epithet. With the increased number of Microporella spp. described over the following years, it is now clear that the presence of personate ovicells is not species-specific, but rather occurs in at least 16 Recent species: Microporella bicollaris Di Martino & Rosso, Citation2021; Microporella browni (see Harmelin et al., Citation2011); Microporella collaroides Harmelin, Ostrovsky, Cáceres-Chamizo & Sanner, Citation2011; Microporella coronata (Audouin & Savigny, Citation1826) (see Harmelin et al. Citation2011); Microporella diademata (see Gordon Citation1989); Microporella epihalimeda Tilbrook, Citation2006; Microporella genisii (Audouin & Savigny, Citation1826) (see Harmelin et al. Citation2011); Microporella hawaiiensis Soule, Chaney & Morris, Citation2003; Microporella lepueana Soule, Chaney & Morris, Citation2004; Microporella maldiviensis Harmelin, Ostrovsky, Cáceres-Chamizo & Sanner, Citation2011; Microporella ordoides (see Di Martino et al. Citation2020); Microporella orientalis (see Harmer Citation1957); Microporella personata (see Busk Citation1854), a potential junior synonym of M. diademata Lamouroux, Citation1825; Microporella pontifica Osburn, Citation1952; Microporella sargassophilia Jain, Gordon, Huang, Kuklinski & Liow, Citation2022; and Microporella wrigleyi Soule, Chaney & Morris, Citation2004. Previous records of fossil exemplars with personate ovicells include Microporella aff. coronata and Microporella aff. browni from the lower and middle Miocene (late Burdigalian and Serravallian, respectively) of East Kalimantan (Di Martino & Taylor Citation2015), and Microporella cf. pontifica from the Pliocene of Florida (Di Martino et al. Citation2019). The lower Miocene specimens with personate ovicells from New Zealand confirm that this character was present very early in the evolution of Microporella.

Acknowledgements

We thank Seabourne Rust, Dennis P. Gordon, Diane Yanakopulos and Kjetil L. Voje for assistance during fieldwork at Whanganui in 2020. KLV funded the 2020 expedition. We are grateful to Marianna Terezow (GNS) for curation of specimens. Antonietta Rosso (University of Catania), Laís Ramalho (Museo Nacional, Quinta da Boa Vista), Dennis P. Gordon (NIWA), and Seabourne Rust provided helpful comments that improved the original manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allman, G.J., 1856. A Monograph of Freshwater Polyzoa, Including All Known Species, Both British and Foreign. The Ray Society, London. [unknown pagination].

- Audouin, J.V. & Savigny, M.J.C., 1826. Explication sommaire des planches de polypes de l’Égypte et de la Syrie, publiées par Jules-César Savigny. In Description de l’Égypte. Histoire naturelle. Jomard, E.F., ed., Imprimerie Nationale, Paris, 225–244.

- Brown, D.A., 1952. The Tertiary Cheilostomatous Polyzoa of New Zealand. Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), London, 405 pp.

- Busk, G., 1852. Catalogue of Marine Polyzoa in the Collection of the British Museum. I. Cheilostomata. Trustees of the British Museum, London. 120 pp.

- Busk, G., 1854. Catalogue of Marine Polyzoa in the Collection of the British Museum, II. Cheilostomata (Part). Trustees of the British Museum, London, 55–120.

- Busk, G., 1884. Report on the Polyzoa Collected by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-1876. Part 1. The Cheilostomata. Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of the H.M.S. “Challenger”, Zoology 10, 1–216.

- Canu, F., 1904. Les bryozoaires du Patagonien. Échelle des bryozoaires pour les terrains tertiares. Mémoires de la Société Géologique de France. Paléontologie 12, 1–30.

- Di Martino, E. & Rosso, A., 2021. Seek and ye shall find: new species and new records of Microporella (Bryozoa, Cheilostomatida) in the Mediterranean. Zookeys 1053, 1–42.

- Di Martino, E. & Taylor, P.D., 2015. Miocene Bryozoa from East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Part II: ‘Ascophoran’ Cheilostomata. Scripta Geologica (Leiden) 148, 1–142.

- Di Martino, E., Taylor, P.D. & Gordon, D.P., 2020. Erect bifoliate species of Microporella (Bryozoa, Cheilostomata), fossil and modern. European Journal of Taxonomy 678, 1–31.

- Di Martino, E., Taylor, P.D., Gordon, D.P. & Liow, L.H., 2017. New bryozoan species from the Pleistocene of the Wanganui Basin, North Island, New Zealand. European Journal of Taxonomy 345, 1–15.

- Di Martino, E., Taylor, P.D. & Portell, R.W., 2019. Anomia-associated bryozoans from the upper Pliocene (Piacenzian) lower Tamiami Formation of Florida, USA. Palaeontologia Electronica, 22.1.11.

- Ehrenberg, C.G., 1831. Symbolae Physicae, seu Icones et descriptiones Corporum Naturalium novorum aut minus cognitorum, quae ex itineribus per Libyam, Aegyptum, Nubiam, Dongalam, Syriam, Arabiam et Habessiniam…studio annis 1820-25 redirerunt. Pars Zoologica, Berolini, Berlin. (v. 4. Animalis Evertebrata exclusis Insectis.)

- Gordon, D.P., 1984. The marine fauna of New Zealand: Bryozoa: Gymnolaemata from the Kermadec Ridge. New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Memoir 91, 1–198.

- Gordon, D.P., 1989. The marine fauna of New Zealand: Bryozoa: Gymnolaemata (Cheilostomida ascophorina) from the western South Island continental shelf and slope. New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Memoir 97, 1–158.

- Harmelin, J.-G., Ostrovsky, A.N., Cáceres-Chamizo, J. & Sanner, J., 2011. Bryodiversity in the tropics: taxonomy of Microporella species (Bryozoa, Cheilostomata) with personate maternal zooids from Indian Ocean, Red Sea and southeast Mediterranean. Zootaxa 2798, 1–30.

- Harmer, S.F., 1957. The Polyzoa of the Siboga Expedition, Part 4. Cheilostomata Ascophora II. Siboga Expedition Reports 28d, 641–1147.

- Heller, C., 1867. Die Bryozoen des adriatischen Meeres. Verhandlungen der zoologisch-botanischen Gesellschaft in Wien 17, 77–136.

- Hincks, T., 1877. On British Polyzoa. Part II. Classification. Annals and Magazine of Natural History (Series 4) 20, 520–532.

- Hincks, T., 1879. On the classification of the British Polyzoa. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 3, 153–164.

- Jain, S.S., Gordon, D.P., Huang, D., Kuklinski, P. & Liow, L.H., 2022. Targeted collections reveal new species and records of Bryozoa and the discovery of Pterobranchia in Singapore. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 70, 1–18.

- Jullien, J., 1883. Dragages du ‘Travailleur’. Bryozoaires, Espèces draguées dans l'Océan Atlantique en 1881. Bulletin de la Société zoologique de France 7, 497–529.

- Jullien, J., 1888. Bryozoaires. Mission Scientifique du Cap Horn 1882–1883 6, 1–92.

- Lamouroux, J.V.F., 1825. Description des polypiers flexibles. In Zoologie, Voyage autour du monde éxécuté sur les corvettes de S. M. l'Uranie et la Physicienne pendant les années 1817, 1818, 1819, 1820 par M. Louis de Freycinet. Quoy, J.R.C. & Gaimard, P., ed., Pillet Aîné, Paris, 603–643.

- Livingstone, A.A., 1929. Papers from Dr Th. Mortensen's Pacific Expedition 1914–16. XLIX. Bryozoa Cheilostomata from New Zealand. Videnskabelige Meddelelser fra Dansk naturhistorisk Forening i Kjøbenhavn 87, 45–104.

- Osburn, R.C., 1952. Bryozoa of the Pacific coast of America, part 2, Cheilostomata-Ascophora. Report of the Allan Hancock Pacific Expeditions 14, 271–611.

- Rust, S., 2009. Plio-Pleistocene bryozoan faunas of the Wanganui Basin, New Zealand. PhD thesis, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 438 pp. plus appendices (unpublished).

- Smitt, F.A., 1873. Floridan Bryozoa collected by Count L.F. de Pourtales, Part 2. Kongliga Svenska Vetenskaps-Akademiens Handlingar 11, 1–83.

- Soule, D.F., Chaney, H.W. & Morris, P.A., 2003. New taxa of Microporellidae from the northeastern Pacific Ocean. Irene McCulloch Foundation Monograph Series 6, 1–38.

- Soule, D.F., Chaney, H.W. & Morris, P.A., 2004. Additional new species of Microporelloides from southern California and American Samoa. Irene McCulloch Foundation Monograph Series 6A, 1–14.

- Taylor, P.D. & Mawatari, S.F., 2005. Preliminary overview of the cheilostome bryozoan Microporella. In Bryozoan Studies 2004. Moyano, G.H.I., Cancino, J.M. & Wyse Jackson, P.N., eds, A.A. Balkema Publishers, Leiden, London, New York, Philadelphia, Singapore, 329–339.

- Tilbrook, K.J., 2006. Cheilostomatous Bryozoa from the Solomon Islands. Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Monographs 4 (Studies in Biodiversity Number 3), 1–386.

- Uttley, G.H. & Bullivant, J.S., 1972. Biological results of the Chatham Islands 1954 Expedition. Part 7. Bryozoa Cheilostomata. New Zealand Oceanographic Institute Memoir 57, 1–61.