Abstract

In 2020, the Australasian palaeontological association Australasian Palaeontologists (AAP) joined the Australian government-supported Australian National Species List (auNSL) initiative to compile the first Australian Fossil National Species List (auFNSL) for the region. The goal is to assemble comprehensive systematic data on all vertebrate, invertebrate and plant fossil taxa described to date, and to present the information both within a continuously updated open-access online framework, and as a series of primary reference articles in AAP’s flagship journal Alcheringa. This paper spearheads these auFNSL Alcheringa publications with an annotated checklist of Australian Mesozoic tetrapods. Complete synonymy, type material, source locality, geological age and bibliographical information are provided for 111 species formally named as of 2022. In addition, chronostratigraphically arranged inventories of all documented Australian Mesozoic tetrapod fossil occurrences are presented with illustrations of significant, exceptionally preserved and/or diagnostic specimens. The most diverse order-level clades include temnospondyl amphibians (34 species), saurischian (13 species) and ornithischian (12 species) dinosaurs (excluding ichnotaxa), and plesiosaurian marine reptiles (11 species). However, numerous other groups collectively span the earliest Triassic (earliest Induan) to Late Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) and incorporate antecedents of modern Australian lineages, such as chelonioid and chelid turtles and monotreme mammals. Although scarce in comparison to records from other continents, Australia’s Mesozoic tetrapod assemblages are globally important because they constitute higher-palaeolatitude faunas that evince terrestrial and marine ecosystem evolution near the ancient South Pole. The pace of research on these assemblages has also accelerated substantially over the last 20 years, and serves to promote fossil geoheritage as an asset for scientific, cultural and economic development. The auFNSL augments the accessibility and utility of these palaeontological resources and provides a foundation for ongoing exploration into Australia’s unique natural history.

Stephen F. Poropat [[email protected]], Western Australian Organic and Isotope Geochemistry Centre, School of Earth and Planetary Science, Curtin University, Bentley, Western Australia 6102, Australia, and Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum of Natural History, Lot 1 Dinosaur Drive, Winton, Queensland 4735, Australia; Phil R. Bell [[email protected]], Palaeoscience Research Centre, School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351, Australia; Lachlan J. Hart [[email protected]], Earth and Sustainability Science Research Centre, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences (BEES), University of New South Wales, Kensington, New South Wales 2052, Australia, and Australian Museum Research Institute, 1 William Street, Sydney, New South Wales 2010, Australia; Steven W. Salisbury [[email protected]] School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia; Benjamin P. Kear [[email protected]] The Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 16, Uppsala SE-752 36, Sweden.

THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL SPECIES LIST (auNSL) is a joint taxonomic resource project (https://biodiversity.org.au/nsl/) involving the Australian Biological Resources Study (ABRS) of the Australian Government Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (https://www.dcceew.gov.au/science-research/abrs), in partnership with the CSIRO (https://www.csiro.au) and various Australian museums, herbaria, and universities. The auNSL aims to produce publicly accessible databases for all formally designated taxa represented in the Australian biota and, thereby, provide an authoritative tool for research, education and government policy. Australasian Palaeontologists (AAP) joined the auNSL to integrate the perspective of past biodiversity, which has otherwise been previously catalogued through disparate external portals, such as the New and Old Worlds (NOW) Database of Fossil Mammals (https://nowdatabase.org/). The resulting Australian Fossil National Species List (auFNSL) is, thus, a resource dedicated to documenting the unique fossil record of the region.

The auFNSL (https://www.australasianpalaeontologists.org/databases) currently hosts taxonomic checklists for multiple invertebrate and vertebrate groups, including species of fossil mammals from Australia and New Guinea (Travouillon et al. Citation2021), Australian fossil birds (Worthy et al. Citation2021), and Australian fossil reptiles and amphibians (Thorn et al. Citation2021). Worthy & Nguyen (Citation2020) independently published an annotated list of Australian fossil bird species that established both a catalyst and formatting blueprint for special feature articles now being published in AAP’s flagship journal Alcheringa. Here, we present the inaugural contribution to this series with an annotated checklist of Australian Mesozoic tetrapods; this expands on data from Thorn et al. (Citation2021) and showcases one of the most high-profile areas of palaeontological research in Australasia. Note that although fragmentary Mesozoic tetrapod fossils are known from Timor and New Caledonia, which were connected to Australia during the early Mesozoic (see Kear et al. Citation2018), these will be summarized in a separate auFNSL annotated list. This survey also excludes fossils from the Australian Antarctic Territories. New Zealand otherwise maintains its own national palaeontological collection (https://www.gns.cri.nz/data-and-resources/national-paleontological-collection/) and locality documentation (https://fred.org.nz/) initiatives.

Collectively, the Australian Mesozoic tetrapod fossil record is among the least prolific of any continent (e.g., Molnar Citation1980a, Citation1982, Citation1991, Warren Citation1972, Citation1982, Citation1991, Long Citation1990, Citation1993, Citation1998, Rich & Vickers-Rich Citation2003a, Scanlon Citation2006, Kear & Hamilton-Bruce Citation2011). Yet, knowledge of these fossils likely extends back many thousands of years amongst First Nations peoples. For instance, in the Saltwater Culture of the West Kimberley in northwestern Western Australia, three-toed footprints exposed along the Dampier Peninsula coastline form part of a song cycle or ‘dreaming’ that traces the journey of a creation being known as Marala or ‘Emu Man’ (Salisbury et al. Citation2017). Western science has come to interpret these tracks as traces of non-avian theropod dinosaurs, and named them Megalosauropus broomensis Colbert & Merrilees, Citation1967. Since the late 1980s, numerous other fossilized tracks have been recorded and described from these rocks, and the region now boasts the most diverse dinosaur ichnocoenoses in the world (Salisbury et al. Citation2017).

The earliest written description of an Australian Mesozoic tetrapod fossil was published in 1859 by the eminent British anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley, who reported a skull and mandible of the temnospondyl amphibian Bothriceps australis Huxley, Citation1859 (Huxley Citation1859). The source locality of this specimen (NHMUK PV R23110) was ‘said to be from Australia’, which left its geographical origin in doubt (Warren & Marsicano Citation1998). The mystery was finally resolved by the discovery of new material in the upper Parmeener Group of Tasmania, which stratigraphically spans the uppermost Permian to lowermost Triassic transition (Warren et al. Citation2011).

A similarly quirky history follows the recovery of Australia’s ‘first’ dinosaur fossils, which were allegedly collected in 1844 on Cape York Peninsula by crew of the British navy warship H.M.S. Fly (Vickers-Rich et al. Citation1999). These bones were duly sent back to England and eventually named Agrosaurus macgillivrayi Seeley, Citation1891 by the famous English palaeontologist Harry Govier Seeley (Seeley Citation1891). Galton (Citation1990) and Molnar (Citation1991) later identified the remains as being from a ‘prosauropod’ (non-sauropod sauropodomorph); however, re-exploration of the supposed type locality (thought to be somewhere on Cape Grenville near the tip of the Cape York Peninsula in northernmost Queensland) in 1995 led Vickers-Rich et al. (Citation1999) to demonstrate that these fossils were not derived from Australia at all. Rather, they were from the UK and had likely been mislabelled. Agrosaurus macgillivrayi was thus formally designated a junior synonym of Thecodontosaurus antiquus Morris, Citation1843, a basally divergent sauropodomorph from the Upper Triassic (Rhaetian) of southwestern England.

At most recent count in 2022, there are 100 genera and 111 species (including 10 nomina dubia) of Mesozoic tetrapods formally named from body or trace fossils found in Australia, with almost 35% having been published in the last ∼20 years (). The majority of these taxa are based on material from Triassic (17 occurrences) and Lower and Upper Cretaceous (29 occurrences) lithostratigraphic units, with only a few (four occurrences) reported from Jurassic rocks (Appendix ).

Table 1. Classification summary of uppermost Permian and Mesozoic tetrapods from the Australian Fossil National Species List.

Temnospondyl amphibians are by far the most diverse order-level clade, with 31 species and 27 genera named from 12 uppermost Permian to Lower Triassic and Middle Triassic formations (see Kear & Hamilton-Bruce Citation2011). An additional three named monospecific genera are recognized from Lower Jurassic (upper Toarcian: Todd et al. Citation2019, Sobczak et al. Citation2022) and Lower Cretaceous (uppermost Barremian to lowermost Aptian: Wagstaff et al. Citation2020) deposits, encompassing the last-surviving member of the clade Koolasuchus cleelandi Warren, Rich & Vickers-Rich, Citation1997 (Warren & Hutchinson Citation1983, Warren et al. Citation1991, Warren et al. Citation1997).

Australian Triassic amniotes include fragmentary dicynodont and cynodont synapsid remains (Thulborn Citation1990, Rozefelds et al. Citation2011), together with a procolophonid, basal neodiapsid, and various archosauromorphs representing five monospecific genera based on body fossils from two formations of Induan to Olenekian age (Ezcurra Citation2014, Hamley et al. Citation2021). Jurassic reptiles incorporate the theropod Ozraptor subotaii Long & Molnar, Citation1998 and an indeterminate sauropod dinosaur (Long Citation1992b, Long & Molnar Citation1998), along with plesiosauroid and ‘rhomaleosaurid-like’ plesiosaurians from two lower Bajocian formations in Western Australia (see Mory et al. Citation2005, Kear Citation2012). The famous gravisaurian sauropod Rhoetosaurus brownei Longman, Citation1926 (Nair & Salisbury Citation2012) was also named from the Oxfordian of Queensland (Todd et al. Citation2019). In addition, indeterminate plesiosaurians (including the geologically oldest identifiable freshwater pliosaurs: Kear Citation2012), and a cryptic diversity of thyreophorans, ornithopods, and small-to-large non-avian theropod dinosaurs have been identified from footprint traces in three formations ranging from the Hettangian to lower Tithonian in Queensland (Romilio Citation2021a, Citation2021b, Romilio et al. Citation2021a, Romilio et al. Citation2021c).

Australian Cretaceous sedimentary rock units are geographically much more extensive than their Triassic or Jurassic counterparts, and have yielded a far greater number of described taxa. Saurischian (12 non-avian monospecific genera) and ornithischian (12 monospecific genera) dinosaurs and plesiosaurian marine reptiles (six unique genera and 11 species) are especially prolific in mid-Valanginian to upper Aptian (Kear Citation2003, Kear et al. Citation2018, Salisbury et al. Citation2017, Wagstaff et al. Citation2020) and upper Albian to mid-Cenomanian (Kear Citation2003, Kear et al. Citation2018, Bell et al. Citation2019b) successions.

Finally, the late Albian enantionithine bird Nanantius eos Molnar, Citation1986, along with 10 mammalian monospecific genera variously identified as ausktribosphenids, bishopids, monotremes and multituberculates have been excavated from uppermost Barremian to lower Albian (Rich & Vickers-Rich Citation2004, Poropat et al. Citation2018, Rich et al. Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Flannery et al. Citation2022a, Flannery et al. Citation2022b), and lower–mid-Cenomanian successions (Bell et al. Citation2019b, Rich et al. Citation2020a).

Exploration for new Mesozoic tetrapod fossil-bearing strata is ongoing, and while historically driven by Australian state museums and universities in collaboration with various international partners, there is now increasing synergy with government accredited regional museums that have led to a wave of new discoveries and raised the profile of regional centres for fossil geotourism and geoconservation (Meakin Citation2011, Sookias et al. Citation2013, Cayla Citation2020). The resulting upsurge in interest, investment and infrastructure is today revolutionizing Australian vertebrate palaeontology, and will no doubt sustain scientific and community benefits for many decades to come.

Institutional abbreviations

AM, Australian Museum, Sydney, Australia. AAOD, Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum of Natural History, Winton, Australia. BMR, Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and Geophysics, Canberra, Australia. KK, Kronosaurus Korner (Richmond Marine Fossil Museum), Richmond, Australia. LR, Australian Opal Centre, Lightning Ridge, Australia. MCZ, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, USA. NHMUK, The Natural History Museum, London, UK. NMV, Melbourne Museum, Museums Victoria, Melbourne, Australia. NRM, Swedish Museum of Natural History (Naturhistoriska riksmuseet), Stockholm, Sweden. NSWGS, New South Wales Geological Survey, Sydney, Australia. QM, Queensland Museum, Brisbane, Australia. SAMA, South Australian Museum, Adelaide, Australia. TMAG, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, Australia. UCMP, University of California Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley, USA. UQ, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. UTGD, University of Tasmania, Department of Geology, Hobart, Australia. UWA, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia. WAM, Western Australian Museum, Perth, Australia.

Systematic palaeontology

TETRAPODA Hatschek & Cori, Citation1896

TEMNOSPONDYLI Zittel, 1888 in Zittel, 1887–Citation1890

Temnospondyli incertae sedis

1885, Lepidostrobus muelleri Johnston, p. 225.

2011, cf. Rhinesuchidae or Rhytidosteidae Rozefelds & Warren, p. 459.

Remarks

We designate Lepidostrobus muelleri a nomen dubium following Rozefelds & Warren (Citation2011).

STEREOSPONDYLI Zittel, 1887–Citation1890

Capulomala Warren, Damiani & Sengupta, Citation2009

Type species

Capulomala arcadiaensis Warren, Damiani & Sengupta, Citation2009.

Capulomala arcadiaensis Warren, Damiani & Sengupta, Citation2009

2009, Capulomala arcadiaensis Warren et al., p. 166.

Holotype

QM F39706, incomplete right mandibular ramus.

Type locality, unit and age

‘Tank locality’ (QM L1111) on the northeastern scarp of the Carnarvon Range, at the southern end of Arcadia Valley in the Central Highlands region of Queensland, Australia. Warren et al. (Citation2009) considered the host deposit to be part of the Arcadia Formation in the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), which Metcalfe et al. (Citation2015) correlated with the upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones. These span the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) based on the recalibrated palynostratigraphy of Mays et al. (Citation2020).

Remarks

Capulomala was erected to accommodate both Capulomala arcadiaensis and a second species, ‘Labyrinthodon’ panchetensis Tripathi, Citation1969, from the Panchet Formation of India (Warren et al. Citation2009). Two partial left mandibular rami (QM F12269, QM F12270) previously referred to Plagiobatrachus australis Warren, Citation1985a from ‘The Crater’ locality (QM L78) near Rolleston in central Queensland, together with multiple specimens from Duckworth Creek (QM L1215) near Bluff in east-central Queensland, have now also been assigned to this taxon (Warren et al. Citation2009).

LYDEKKERINIDAE Watson, Citation1919

Lydekkerina Broom, Citation1915

Type species

Lydekkerina huxleyi (see Lydekker Citation1889a, Broom Citation1915).

Lydekkerina huxleyi (Lydekker, Citation1889a) Broom, Citation1915

1889a, Bothriceps huxleyi Lydekker, p. 476.

1915, Lydekkerina huxleyi Broom, p. 366.

2006, Lydekkerina huxleyi Warren et al., p. 878.

Holotype

NHMUK PV R507, an associated skull with articulated left and partial right mandibular ramus, together with cervical and anterior dorsal vertebrae.

Type locality, unit and age

Unspecified site within the Karoo Basin of the Free State Province in South Africa. Botha & Smith (Citation2020) listed Lydekkerina huxleyi as a diagnostic taxon for the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone in the Beaufort Group (Karoo Basin), which spans the Induan to lower Olenekian (Lower Triassic).

Remarks

Warren et al. (Citation2006) attributed a skull with both mandibular rami (QM F39705) to Lydekkerina huxleyi from upper Induan to lower Olenekian strata (see Mays et al. Citation2020) of the Rewan Formation (Galilee Basin) on Alpha Station (QM L1434) near Alpha, in southeastern Queensland. Lydekkerina huxleyi is otherwise geographically restricted to Lower Triassic deposits in South Africa (Pawley & Warren Citation2005, Jeannot et al. Citation2006).

Chomatobatrachus Cosgriff, Citation1974

Type species

Chomatobatrachus halei Cosgriff, Citation1974.

Chomatobatrachus halei Cosgriff, Citation1974

1974, Chomatobatrachus halei Cosgriff, p. 44.

Holotype

UTGD 80738, an isolated intact skull.

Type locality, unit and age

Meadowbank Dam northwest of Hobart in Tasmania, Australia. Ezcurra (Citation2014) correlated Chomatobatrachus halei with coeval vertebrate assemblages from the Knocklofty Formation (Tasmanian Basin), which is predominantly Induan to lower Olenekian (Lower Triassic) but has a maximum depositional age of 253 ± 4 mega-annum (Ma).

Remarks

Chomatobatrachus halei is represented by multiple specimens from several localities in southeast Tasmania (Cosgriff Citation1974). The taxon is consistently placed with Lydekkerina huxleyi (Lydekker, Citation1889a) in Lydekkerinidae (Warren et al. Citation2006, Schoch Citation2013, Gee Citation2022, Gee et al. Citation2022).

Lapillopsis Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1990b

Type species

Lapillopsis nana Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1990b.

Lapillopsis nana Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1990b

1990a, Dissorophoidea: Micropholidae Warren & Hutchinson, p. 105.

1990b, Lapillopsis nana Warren & Hutchinson, p. 149.

1999, Lapillopsis nana Yates, p. 303.

Holotype

QM F12284, an associated skull (), mandible, interclavicle, right scapulocoracoid, right humerus, and femur.

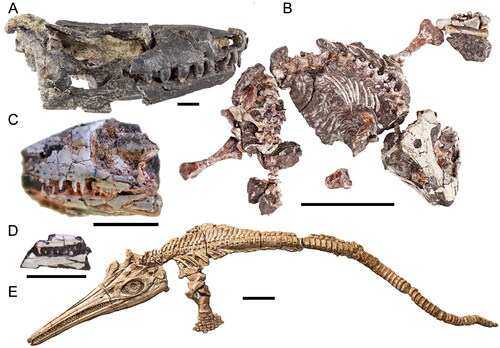

Fig. 1. Australian uppermost Permian and Mesozoic temnospondyls. A, Watsonisuchus gunganj (QM F10114; holotype) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. B, Chigutisauridae nov. (AM F125866) skull and partial skeleton. Scale = 10 cm. C, Trucheosaurus major (AM F50977; holotype) partial postcranial skeleton. Scale = 5 cm. D, Bulgosuchus gargantua (AM F80190; holotype) left mandible in lateral view. Scale = 10 cm. E, Subcyclotosaurus brookvalensis (AM F47499) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. F, Lapillopsis nana (QM F12284; holotype) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 1 cm. G, Rewana quadricuneata (QM F6471; holotype) partial skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. H, Tirraturhinus smisseni (QM F44093; holotype) rostral portion of skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. I, Warrenisuchus aliciae (QM F12281; holotype) partial skull in dorsal view. Scale = 1 cm. J, Keratobrachyops australis (QM F10115; holotype) skull in dorsal view. K, Xenobrachyops allos (QM F6572; holotype) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. L, Bothriceps australis (AM F4316; cast of holotype [NHMUK PV R23110]) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm.

![Fig. 1. Australian uppermost Permian and Mesozoic temnospondyls. A, Watsonisuchus gunganj (QM F10114; holotype) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. B, Chigutisauridae nov. (AM F125866) skull and partial skeleton. Scale = 10 cm. C, Trucheosaurus major (AM F50977; holotype) partial postcranial skeleton. Scale = 5 cm. D, Bulgosuchus gargantua (AM F80190; holotype) left mandible in lateral view. Scale = 10 cm. E, Subcyclotosaurus brookvalensis (AM F47499) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. F, Lapillopsis nana (QM F12284; holotype) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 1 cm. G, Rewana quadricuneata (QM F6471; holotype) partial skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. H, Tirraturhinus smisseni (QM F44093; holotype) rostral portion of skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. I, Warrenisuchus aliciae (QM F12281; holotype) partial skull in dorsal view. Scale = 1 cm. J, Keratobrachyops australis (QM F10115; holotype) skull in dorsal view. K, Xenobrachyops allos (QM F6572; holotype) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. L, Bothriceps australis (AM F4316; cast of holotype [NHMUK PV R23110]) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm.](/cms/asset/1b8a0465-789e-494f-8cfe-f7ea8445f6cb/talc_a_2228367_f0001_c.jpg)

Type locality, unit and age

‘The Crater’ locality (QM L78) near Rolleston in central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Originally identified as a dissorophoid and classified within Micropholidae (Warren & Hutchinson Citation1990a, Citation1990b), Lapillopsis nana has since been referred to Lapillopsidae (Yates Citation1999) or Lydekkerinidae (Eltink et al. Citation2019, Gee Citation2022).

Rotaurisaurus Yates, Citation1999

Type species

Rotaurisaurus contundo Yates, Citation1999.

Rotaurisaurus contundo Yates, Citation1999

1974, Chomatobatrachus halei Cosgriff, p. 44 [partim]

1999, Lapillopsis nana Yates, p. 311.

Holotype

UTGD 87795, an isolated crushed skull with associated left mandibular ramus.

Type locality, unit and age

‘Lower Red Bed’ layer within the Crisp and Gunn’s Brick Pit, western end of Arthur Street in suburban Hobart, Tasmania, Australia; Knocklofty Formation (Tasmania Basin) correlated with Induan to lower Olenekian (Lower Triassic) vertebrate assemblages by Ezcurra (Citation2014).

Remarks

UTGD 87795 was initially referred to Chomatobatrachus halei by Cosgriff (Citation1974), but subsequently established as Rotaurisaurus contundo by Yates (Citation1999). Rotaurisaurus contundo is placed within Lydekkerinidae following the phylogeny-based classifications of Eltink et al. (Citation2019) and Gee (Citation2022).

CAPITOSAURIA Schoch & Milner, Citation2000

Bulgosuchus Damiani, Citation1999

Type species

Bulgosuchus gargantua Damiani, Citation1999.

Bulgosuchus gargantua Damiani, Citation1999

1999, Bulgosuchus gargantua Damiani, p. 91.

Holotype

AM F80190, the posterior glenoid section of a left mandibular ramus ().

Type locality, unit and age

Coastal rock platform at Long Reef in the northern beaches suburbs of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The vertebrate fossil-bearing layer at Long Reef occurs within the Bulgo Sandstone (Damiani Citation1999, Kear Citation2009, Niedźwiedzki et al. Citation2016) of the Clifton Subgroup in the Narrabeen Group (Sydney Basin). Mays et al. (Citation2020) directly correlated this level with the mid-Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii Zone. Metcalfe et al. (Citation2015) also delimited the unit as being older than 248.23 ± 0.13 Ma based on U-Pb zircon dating from the up-sequence Garie Formation.

Remarks

At the time of discovery, Bulgosuchus gargantua was distinguished as the largest-bodied Early Triassic temnospondyl known worldwide (Damiani Citation1999, Citation2001).

Watsonisuchus Ochev, Citation1966

Type species

Watsonisuchus magnus (Watson, Citation1962) Ochev, Citation1966.

Watsonisuchus sp. indet.

1972, Parotosaurus wadei Cosgriff, p. 546.

1980, Parotosuchus wadei (Cosgriff) Warren, p. 25.

1997, Parotosuchus wadei (Cosgriff) Damiani & Warren, p. 282.

2001, Watsonisuchus sp. indet. Damiani, p. 429.

Holotype

AM F55341, an external impression of the skull roof.

Type locality, unit and age

The Railway Ballast Quarry near Gosford in northeastern New South Wales, Australia. These deposits are correlated with the Terrigal Formation of the Narrabeen Group (Sydney Basin). Helby (Citation1973) and Morante (Citation1996) placed this unit within the mid-Olenekian to lower Anisian (Lower to Middle Triassic) Aratrisporites tenuispinosus Palynomorph Zone. Mays & McLoughlin (Citation2022) also listed a specific age estimate of ∼248 Ma.

Remarks

AM F55341 was excavated in 1886 (Stephens Citation1888) and variously attributed to Parotosaurus Jaekel, Citation1922 (Cosgriff Citation1972), Parotosuchus (Warren Citation1980), or treated as a nomen dubium (Damiani & Warren Citation1997), before being transferred to an indeterminate species of Watsonisuchus by Damiani (Citation2001).

Watsonisuchus rewanensis (Warren, Citation1980) Damiani, Citation2001

1980, Parotosuchus rewanensis Warren, p. 26.

2000, Rewanobatrachus gunganj (Warren) Schoch & Milner, p. 135.

2001, Watsonisuchus rewanensis (Warren) Damiani, p. 429.

Holotype

QM F6571, an isolated intact skull.

Type locality, unit and age

‘The Crater’ locality (QM L78) near Rolleston in central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Watsonisuchus rewanensis was initially assigned to Parotosuchus (Warren Citation1980) but has also been treated as a junior synonym of Rewanobatrachus gunganj (Schoch & Milner Citation2000). Maganuco et al. (Citation2009) demonstrated close affinity with Watsonisuchus magnus, thus confirming the generic placement of Damiani (Citation2001).

Watsonisuchus gunganj (Warren, Citation1980) Damiani, Citation2001

1980, Parotosuchus gunganj Warren, p. 29.

2000, Rewanobatrachus gunganj (Warren) Schoch & Milner, p. 135.

2001, Watsonisuchus gunganj (Warren) Damiani, p. 427.

Holotype

QM F10114, an isolated fragmented skull with incomplete mandible ().

Type locality, unit and age

‘The Crater’ locality (QM L78) near Rolleston in central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

See remarks for Watsonisuchus wadei and Watsonisuchus rewanensis. We follow the generic assignments of Damiani (Citation2001) and Maganuco et al. (Citation2009).

Warrenisuchus Maganuco, Steyer, Pasini, Boulay, Lorrain, Bénéteau & Auditore, Citation2009

Type species

Warrenisuchus aliciae (Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1988) as revised by Maganuco et al. (Citation2009).

Warrenisuchus aliciae (Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1988)

1988, Parotosuchus aliciae Warren & Hutchinson, p. 860.

2000, Rewanobatrachus aliciae (Warren & Hutchinson) Schoch & Milner, p. 135.

2001, Watsonisuchus aliciae (Warren & Hutchinson) Damiani, p. 425.

2009, Warrenisuchus aliciae (Warren & Hutchinson) Maganuco et al., p. 37.

Holotype

QM F12281, an associated intact skull () and mandible with vertebrae, ribs, the right ilium, and right hind limb.

Type locality, unit and age

Duckworth Creek (QM L215) near Bluff in east-central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Warrenisuchus aliciae has been variously assigned to Parotosuchus Ochev & Shishkin in Kalandadze, Citation1968 (Warren & Hutchinson Citation1988), Rewanobatrachus Schoch & Milner, Citation2000 (Schoch & Milner Citation2000), and Watsonisuchus (Damiani Citation2001). However, Maganuco et al. (Citation2009) demonstrated sufficient differentiation from these taxa to establish the monotypic genus, Warrenisuchus. Although occurring commonly in the Arcadia Formation (Warren & Hutchinson Citation1988, Warren & Schroeder Citation1995), other potentially attributable remains (= Parotosuchus sp. indeterminate: Warren Citation1980) have been identified from the Lower Triassic Blina Shale in the Canning Basin, Western Australia (Damiani Citation2000).

MASTODONSAURIDAE Lydekker, Citation1885 (sensu Moser & Schoch Citation2007)

Paracyclotosaurus Watson, Citation1958

Type species

Paracyclotosaurus davidi Watson, Citation1958.

Paracyclotosaurus davidi Watson, Citation1958

1958, Paracyclotosaurus davidi Watson, p. 237.

Holotype

NHMUK PV R6000, natural impressions of an articulated skull ( AM F151922 cast), mandible and a virtually complete postcranial skeleton with associated skin and scale traces preserved in counterpart ironstone concretions that have been prepared out and cast (Watson Citation1958).

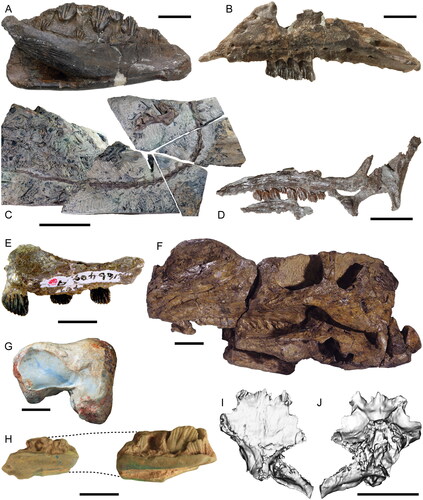

Fig. 2. Australian Mesozoic temnospondyls. A, Siderops kehli (QM F7882; holotype) skull and partial skeleton. Scale = 20 cm. B, Austropelor wadleyi (QM F2628; holotype) 3D digital rendering of partial dentary in dorsal (occlusal) view. Scale = 5 cm. C, Microposaurus averyi (AM F135895; holotype) rostral portion of skull in right lateral view. Scale = 5 cm. D, Paracyclotosaurus davidi (3D digital rendering of AM F151922; reconstruction based on NHMUK PV R6000) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 10 cm. Koolasuchus cleelandi (NMV P186213; holotype [part]) right mandible in E, dorsal (occlusal) and F, lateral views. Scale = 5 cm. G, Koolasuchus cleelandi (NMV P186213; holotype) left and right mandibles in dorsal (occlusal) view. Dashed line represents reconstructed contour of lower jaw. Scale = 10 cm.

![Fig. 2. Australian Mesozoic temnospondyls. A, Siderops kehli (QM F7882; holotype) skull and partial skeleton. Scale = 20 cm. B, Austropelor wadleyi (QM F2628; holotype) 3D digital rendering of partial dentary in dorsal (occlusal) view. Scale = 5 cm. C, Microposaurus averyi (AM F135895; holotype) rostral portion of skull in right lateral view. Scale = 5 cm. D, Paracyclotosaurus davidi (3D digital rendering of AM F151922; reconstruction based on NHMUK PV R6000) skull in dorsal view. Scale = 10 cm. Koolasuchus cleelandi (NMV P186213; holotype [part]) right mandible in E, dorsal (occlusal) and F, lateral views. Scale = 5 cm. G, Koolasuchus cleelandi (NMV P186213; holotype) left and right mandibles in dorsal (occlusal) view. Dashed line represents reconstructed contour of lower jaw. Scale = 10 cm.](/cms/asset/4f2bc443-59e9-49f3-b8c4-69b7cc34bc90/talc_a_2228367_f0002_c.jpg)

Type locality, unit and age

St Peters Brick Pit at St Peters in metropolitan Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. This locality exposes deposits of the Rouse Hill Siltstone Member of the Ashfield Shale, which is the basalmost unit within the Wianamatta Group (Sydney Basin). Herbert (Citation1983, Citation1997) indicated a probable mid-Anisian (Middle Triassic) age for this unit. Helby (Citation1973) provided a specific correlation with the Aratrisporites parvispinosus Palynomorph Zone (see also Helby et al. Citation1987, Metcalfe et al. Citation2015).

Remarks

NHMUK PV R6000 was discovered before 1910 (possibly as early as 1892) and sold to the British Museum (Natural History) in 1927 (Rix Citation2023), where it was reconstructed for exhibition over several decades (Watson Citation1958). Early reports described the find as a temnospondyl similar to Cyclotosaurus Fraas, Citation1889 (e.g., Watson Citation1918, Citation1919, Howchin 1925–Citation1930, David Citation1932, Longman Citation1941, Romer Citation1947, Hills Citation1958). The genus and species, Paracyclotosaurus davidi, was eventually established 48 years later by Watson (Citation1958). Since then, other species of Paracyclotosaurus have been named, including Paracyclotosaurus crookshanki Damiani, Citation2001 from the ?Anisian Denwa Formation of India (Mukherjee & Sengupta Citation1998, Damiani Citation2001), and Paracyclotosaurus morganorum Damiani & Hancox, Citation2003 from upper Anisian strata of the Cynognathus Assemblage Zone in the Beaufort Group (Karoo Basin) of South Africa (Hancox et al. Citation2000, Damiani & Hancox Citation2003).

Subcyclotosaurus Watson, Citation1958

Type species

Subcyclotosaurus brookvalensis Watson, Citation1958.

Subcyclotosaurus brookvalensis Watson, Citation1958

1958, Subcyclotosaurus brookvalensis Watson, p. 258.

Citation1965, Parotosaurus brookvalensis Welles & Cosgriff, p. 80.

1968, Parotosuchus brookvalensis Ochev & Shishkin in Kalandadze, p. 77.

2000, Stanocephalosaurus sp. Schoch & Milner, p. 147.

2001, Mastodonsauridae incertae sedis Damiani, p. 436.

Holotype

AM F47499, an isolated impression of the external skull roof and left mandibular ramus ().

Type locality, unit and age

The Beacon Hill Quarry at Brookvale in suburban Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Herbert (Citation1997) recognized that the Beacon Hill Quarry exposed part of the extensive Hawkesbury Sandstone of the Sydney Basin. Helby (Citation1973), Herbert (Citation1983) and Helby et al. (Citation1987) included this unit within the probable lower Anisian (Middle Triassic) section of the Aratrisporites parvispinosus Palynomorph Zone (see also Metcalfe et al. Citation2015).

Remarks

Subcyclotosaurus brookvalensis was classified as Mastodonsauridae incertae sedis by Damiani (Citation2001), but is retained here pending re-evaluation.

TREMATOSAURIA Yates & Warren, Citation2000

TREMATOSAUROIDEA Watson, Citation1919

TREMATOSAURIDAE Watson, Citation1919

Tirraturhinus Nield, Damiani & Warren, Citation2006

Type species

Tirraturhinus smisseni Nield, Damiani & Warren, Citation2006.

Tirraturhinus smisseni Nield, Damiani & Warren, Citation2006

2006, Tirraturhinus smisseni Nield et al., p. 264.

Holotype

QM F44093, an isolated prenarial section of the skull showing the skull roof and palate ().

Type locality, unit and age

Duckworth Creek (QM L215) near Bluff in east-central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Although classified within Trematosauridae (Schoch Citation2019), the fragmentary condition of QM F44093 prevents an unambiguous placement within the clade (Novikov Citation2012).

LONCHORHYNCHINAE Säve-Söderbergh, Citation1935

Erythrobatrachus Cosgriff & Garbutt, Citation1972

Type species

Erythrobatrachus noonkanbahensis Cosgriff & Garbutt, Citation1972.

Erythrobatrachus noonkanbahensis Cosgriff & Garbutt, Citation1972

1972, Erythrobatrachus noonkanbahensis Cosgriff & Garbutt, p. 7.

Holotype

WAM 62.1.46, an internal impression of the nasofrontal region of the skull and opposing palate.

Type locality, unit and age

UCMP locality V6044 on Blina Station in the Erskine Ranges of the West Kimberley District, Western Australia. McKenzie (Citation1961) summarized the vertebrate fossil localities from the Blina Shale (Canning Basin), indicating a Lower Triassic succession. Haig et al. (Citation2015) specified an upper Induan–Olenekian range corresponding with the upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (see also Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Cosgriff (Citation1965) suggested that Erythrobatrachus noonkanbahensis might be congeneric with Tertrema Wiman, Citation1914 (see Slodownik et al. Citation2021). Erythrobatrachus noonkanbahensis has otherwise been classified as a distinct taxon within Lonchorhynchinae (Hammer Citation1987, Welles Citation1993, Fortuny et al. Citation2018).

TREMATOSAURINAE Watson, Citation1919

Microposaurus Haughton, Citation1925

Type species

Microposaurus casei Haughton, Citation1925.

Microposaurus averyi Warren, Citation2012

2012, Microposaurus averyi Warren, p. 538.

Holotype

AM F135895, an isolated anterior section of the skull with articulated mandible ().

Type locality, unit and age

Unspecified locality ∼7 km southeast of Picton, southwest of Sydney in New South Wales, Australia; Rouse Hill Siltstone Member of the Ashfield Shale in the Wianamatta Group (Sydney Basin), mid-Anisian (Middle Triassic) Aratrisporites parvispinosus Palynomorph Zone (Herbert Citation1983, Citation1997, Helby et al. Citation1987, Metcalfe et al. Citation2015).

Remarks

Microposaurus has been recorded elsewhere from the Cynognathus Assemblage Zone (upper Olenekian: Hancox et al. Citation2020) of the Beaufort Group in South Africa (Haughton Citation1925, Damiani Citation2004).

RHYTIDOSTEIDAE von Huene, Citation1920

Trucheosaurus Watson, Citation1956

Type species

Trucheosaurus major (Smith Woodward, Citation1909) as revised by Watson (Citation1956).

Trucheosaurus major (Smith Woodward, Citation1909)

1909, Bothriceps major Smith Woodward, p. 319.

1911, Bothriceps woodwardi Moodie, p. 375.

1956, Trucheosaurus major (Smith Woodward) Watson, p. 327.

Holotype

The holotype material has been accessioned into three separate collection repositories: NSWGS F12967, part component showing the intact skull roof; AM F50977, part component of the incomplete vertebral column and right forelimb with some right hind limb elements (); NHMUK PV R3728, counterpart component of the skull roof, incomplete vertebral column and limb elements.

Type locality, unit and age

Commonwealth Oil Corporation oil shale mine at Airly in central-eastern New South Wales, Australia. Marsicano & Warren (Citation1998) listed the source unit as the Glen Davis Formation within the Charbon Subgroup in the Illawarra Coal Measures (Sydney Basin). McMinn (Citation1985) correlated the Glen Davis Formation with the upper Tomago Coal Measures in the northern Sydney Basin, which are mid-Lopingian (upper Permian) based on Percival et al. (Citation2012).

Remarks

Although of Palaeozoic age, we include Trucheosaurus major as a rare late Permian tetrapod taxon named from the otherwise predominantly Early–Middle Triassic tetrapod assemblage succession of the Sydney Basin. Trucheosaurus major was originally described as a brachyopid (Watson Citation1956), but has more recently been interpreted as the geologically oldest member of Rhytidosteidae (Warren Citation1997, Marsicano & Warren Citation1998).

Deltasaurus Cosgriff, Citation1965

Type species

Deltasaurus kimberleyensis Cosgriff, Citation1965.

Deltasaurus kimberleyensis Cosgriff, Citation1965

1965, Deltasaurus kimberleyensis Cosgriff, p. 68.

Holotype

WAM 62.1.44, an isolated incomplete skull preserving the left lateral skull roof and corresponding palate.

Type locality, unit and age

UCMP locality V6040 on Blina Station in the Erskine Ranges of the West Kimberley District, Western Australia; Blina Shale (Canning Basin), upper Induan to lower Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Haig et al. Citation2015).

Remarks

Deltasaurus kimberleyensis is one of the most common vertebrate fossil taxa encountered in the Blina Shale (Cosgriff Citation1965). The species has also been identified from the Cluan and Knocklofty formations of Tasmania (Cosgriff Citation1974). Schoch & Milner (Citation2000) proposed a subfamilial placement within Peltosteginae.

Deltasaurus pustulatus Cosgriff, Citation1965

1965, Deltasaurus pustulatus Cosgriff, p. 80.

Holotype

BMR F21775, a skull roof fragment preserving the right orbital region and corresponding palate.

Type locality, unit and age

Beagle Ridge Bore (BMR 10) north of Geraldton in southwestern Western Australia. Cosgriff (Citation1965) listed the source unit as the Kockatea Shale (Perth Basin), which Thomas et al. (Citation2004) recognized as spanning the Permian/Triassic boundary. Haig et al. (Citation2015) alternatively correlated strata along the onshore basin margins with the lower Olenekian (Lower Triassic) Krauselisporites saeptatus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones.

Remarks

Dickins et al. (Citation1961) reported that BMR F21775 was encountered at a bore depth of ∼1 km. Haig et al. (Citation2015) have since also described possible temnospondyl remains from surface exposures of the Kockatea Shale.

Rewana Howie, Citation1972b

Type species

Rewana quadricuneata Howie, Citation1972b.

Rewana quadricuneata Howie, Citation1972b

1972, Rewana quadricuneata Howie, p. 52.

Holotype

QM F6471, an incomplete palate with components of the skull roof () and an associated largely intact postcranial skeleton.

Type locality, unit and age

‘The Crater’ locality (QM L78) near Rolleston in central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Rewana quadricuneata has been taxonomically problematic (Howie Citation1972b), with various referrals to Indobrachyopidae (Cosgriff & Zawiskie Citation1979), Derwentiidae (Schoch & Milner Citation2000) or Rhytidosteidae (Warren & Black Citation1985). We follow the phylogeny-based classification of Dias-Da-Silva & Marsicano (Citation2011), who placed R. quadricuneata in Rhytidosteidae.

Derwentia Cosgriff, Citation1974

Type species

Derwentia warreni Cosgriff, Citation1974

Derwentia warreni Cosgriff, Citation1974

1974, Derwentia warreni Cosgriff, p. 75.

Holotype

UTGD 87784, an isolated intact skull.

Type locality, unit and age

‘Old Beach’ locality on the eastern shore of the Derwent River north of Hobart in Tasmania, Australia; Knocklofty Formation (Tasmanian Basin) correlated with Induan to lower Olenekian (Lower Triassic) vertebrate assemblages by Ezcurra (Citation2014).

Remarks

Derwentia warreni has been variously assigned to Rhytidosteidae (Cosgriff Citation1974), Indobrachyopidae (Cosgriff & Zawiskie Citation1979), and Derwentiidae (Schoch & Milner Citation2000). We follow the phylogeny-based classification of Dias-Da-Silva & Marsicano (Citation2011) with assignment of D. warreni to Rhytidosteidae.

Arcadia Warren & Black, Citation1985

Type species

Arcadia myriadens Warren & Black, Citation1985.

Arcadia myriadens Warren & Black, Citation1985

1985, Arcadia myriadens Warren & Black, p. 314.

2000, Rewana myriadens (Warren & Black) Schoch & Milner, p. 85.

Holotype

QM F10121, a fragmented skull roof with palatal components, incomplete mandibular rami and associated vertebrae, rib fragments and hind limb elements.

Type locality, unit and age

Duckworth Creek (QM L215) near Bluff in east-central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Arcadia myriadens has been classified as either a rhytidosteid (Warren & Black Citation1985) or derwentiid (Schoch & Milner Citation2000). Schoch & Milner (Citation2000) also used the alternative generic designation Rewana myriadens. We follow the phylogeny-based classification of Dias-Da-Silva & Marsicano (Citation2011) with assignment of A. myriadens to Rhytidosteidae.

Acerastea Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1987

Type species

Acerastea wadeae Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1987.

Acerastea wadeae Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1987

1987, Acerastea wadeae Warren & Hutchinson, p. 292.

Holotype

QM F12277, a fragmentary skull with mandibular rami, vertebrae, ribs pectoral girdle, forelimb and pelvic girdle elements, together with associated gastroliths.

Type locality, unit and age

‘The Crater’ locality (QM L78) near Rolleston in central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Schoch & Milner (Citation2000) placed Acerastea wadeae within Derwentiidae, although we follow Dias-Da-Silva & Marsicano (Citation2011) in their phylogeny-based referral to Rhytidosteidae. Warren & Hutchinson (Citation1987) also remarked on the unusual presence of associated gastroliths.

Nanolania Yates, Citation2000

Type species

Nanolania anatopretia Yates, Citation2000.

Nanolania anatopretia Yates, Citation2000

1990a, Arcadia myriadens (Warren & Black) Warren & Hutchinson, p. 104.

2000, Nanolania anatopretia Yates, p. 485.

Holotype

QM F12293, the postorbital region of a skull and parts of both mandibular rami.

Type locality, unit and age

Duckworth Creek (QM L215) near Bluff in east-central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Warren & Hutchinson (Citation1990a) initially identified QM F12293 as an osteologically immature specimen of Arcadia myriadens. Yates (Citation2000) subsequently established Nanolania anatopretia as a distinct species within Rhytidosteidae.

PLAGIOSAURIDAE Jaekel, Citation1914

Plagiobatrachus Warren, Citation1985a

Type species

Plagiobatrachus australis Warren Citation1985a.

Plagiobatrachus australis Warren Citation1985a

1985, Plagiobatrachus australis Warren, p. 237.

Holotype

QM F12667, a vertebral centrum.

Type locality, unit and age

‘The Crater’ locality (QM L78) near Rolleston in central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Doubts have been raised about the validity of Plagiobatrachus australis (Warren et al. Citation2009, Gee & Sidor Citation2022), with several specimens (see Warren Citation1985a) reassigned to Capulomala arcadiaensis (Warren et al. Citation2009).

BRACHYOPOIDEA Lydekker, Citation1885

Austropelor Longman, Citation1941

Type species

Austropelor wadleyi Longman, Citation1941.

Austropelor wadleyi Longman, Citation1941

1941 Austropelor wadleyi Longman, p. 29.

Holotype

QM F2628, a mandibular ramus fragment ().

Type locality, unit and age

Collected from the bed of the Brisbane River, ∼1.6 km southeast of Lowood west of Brisbane in southeastern Queensland, Australia. Warren & Hutchinson (Citation1983) recognized the source unit as the lower Marburg Sandstone (Clarence-Morton Basin), which has since been elevated to sub-group level (Wells & O’Brien Citation1994). The exposures at Lowood have thus been correlated with the Ma Ma Creek Member of the Koukandowie Formation (O’Brien & Wells Citation1994), which is likely Toarcian in age based on Pliensbachian–Toarcian plant fossils found in the underlying Gatton Sandstone (Jansson et al. Citation2008). The lower Marburg Subgroup was also considered a lateral equivalent of the Evergreen Formation (Surat Basin) by Exon (Citation1976) and Day et al. (Citation1983), which incorporates Pliensbachian to Aalenian (Lower to Middle Jurassic) deposits across the Surat Basin (La Croix et al. Citation2022).

Remarks

Austropelor wadleyi was initially interpreted as a capitosaurid (Longman Citation1941), but later classified as a stereospondyl (Colbert Citation1967) and has since been assigned to Brachyopoidea incertae sedis (Warren & Marsicano Citation2000b) or Stereospondyli incertae sedis (Schoch & Milner Citation2000).

BRACHYOPIDAE Lydekker, Citation1885

Bothriceps Huxley, Citation1859

Type species

Bothriceps australis Huxley, Citation1859.

Bothriceps australis Huxley, Citation1859

1859, Bothriceps australis Huxley, p. 649.

Holotype

NHMUK PV R23110, impressions of an isolated skull roof ( AM F4316 cast), partial palate and occipital region with articulated mandible.

Type locality, unit and age

Unspecified locality, possibly Eli Point near Koonya on the Tasman Peninsula in southeastern Tasmania, Australia (Warren et al. Citation2011). Warren et al. (Citation2011) suggested that the source unit was probably within the upper Parmeener Supergroup (Tasmania Basin), which spans the uppermost Permian to lowermost Triassic interval.

Remarks

Huxley (Citation1859) provided ambiguous source information for NHMUK PV R23110, although the type locality was assumed to be the Middle Triassic (Anisian) Hawkesbury Sandstone in New South Wales (Lydekker Citation1890, Moodie Citation1911). Watson (Citation1919, p. 44) emphasized that ‘the exact locality and of course the horizon are unknown’ and, subsequently, added that the ‘type—and only known specimen—was bought by the British Museum in 1848 from a person of whom nothing is known’ (Watson Citation1956, p. 422). Cosgriff (Citation1969, p. 80) otherwise stated that NHMUK PV R23110 ‘is believed to come from a locality in the Upper Permian Lithgow Coal Measures of the Sydney Basin in New South Wales’. Warren (Citation1997, p. 26) further explained that a ‘label associated with the specimen says it is from the “Hawkesbury Beds (Permian)”. This was probably an educated guess but could well be correct except that the Hawkesbury Sandstone of the Sydney Basin is now early Middle Triassic’. Conversely, the discovery of multiple new specimens of Bothriceps australis from Eli Point near Koonya in Tasmania suggests that this locality might have been the original source for NHMUK PV R23110 (Warren et al. Citation2011). Accordingly, Warren et al. (Citation2011, p. 740) reported that the ‘holotype was bought…from a Mrs. Musworthy’, at a time when, ‘…Koonya (then known as Cascades) was an outstation for the penal colony established at Port Arthur, some 15 km to the southeast. It seems likely that NHMUK 23110 was found on the rock platform at Koonya by someone associated with the colony, and sent to England without documentation of the precise locality of the find’ (Warren et al. Citation2011, pp. 746–749). Bothriceps australis was referred to Brachyopidae by Broom (Citation1915). This classification has since been followed by most studies (e.g., Welles & Estes Citation1969, Warren & Marsicano Citation1998, Warren et al. Citation2011), but Warren & Marsicano (Citation2000b) alternatively placed B. australis outside of Brachyopidae and within the more inclusive clade Brachyomorpha.

Batrachosuchus Broom, Citation1903a

Type species

Batrachosuchus henwoodi (Cosgriff, Citation1969) Warren & Marsicano, Citation1998.

Batrachosuchus henwoodi (Cosgriff, Citation1969) Warren & Marsicano, Citation1998

1969, Blinasaurus henwoodi Cosgriff, p. 68.

1998, Batarachosuchus henwoodi (Cosgriff) Warren & Marsicano, p 336.

Holotype

WAM 62.1.42, impressions of an isolated skull incorporating the internal skull roof and palatal surfaces.

Type locality, unit and age

UCMP locality V6041 on Blina Station in the Erskine Ranges of the West Kimberley District, Western Australia; Blina Shale (Canning Basin), upper Induan to lower Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Haig et al. Citation2015).

Remarks

Initially referred to Blinasaurus by Cosgriff (Citation1969) but transferred to Batrachosuchus by Warren & Marsicano (Citation1998).

Platycepsion Kuhn, Citation1961

Type species

Platycepsion wilkinsoni (Stephens, Citation1887c) Kuhn, Citation1961.

Platycepsion wilkinsoni (Stephens, Citation1887c) Kuhn, Citation1961.

1887, Platyceps wilkinsonii Stephens, p. 1181.

1890, Bothriceps wilkinsonii (Stephens) Lydekker, p. 172.

1961, Platycepsion wilkinsonii (Stephens) Kuhn, p. 79.

1969, Blinasaurus wilkinsoni (Stephens) Cosgriff, p. 68.

1969, Bothriceps wilkinsoni (Stephens) Welles & Estes, p. 21.

1998, Platycepsion wilkinsoni (Stephens) Warren & Marsicano, p. 333.

Holotype

NSWGS F12572, articulated incomplete skeleton incorporating the skull roof with branchial bars, neural arches and ribs, the pectoral girdle and elements of the pelvic girdle and right hind limb.

Type locality, unit and age

The Railway Ballast Quarry near Gosford in northeastern New South Wales, Australia; Terrigal Formation of the Narrabeen Group (Sydney Basin), mid-Olenekian to lower Anisian (Lower to Middle Triassic) Aratrisporites tenuispinosus Palynomorph Zone (sensu Helby Citation1973, Morante Citation1996).

Remarks

Lydekker (Citation1890) reported that Platyceps, as established by Stephens (Citation1887c), was preoccupied, and suggested that Platyceps wilkinsoni was likely a ‘juvenile’ individual of Bothriceps (see also Welles & Estes Citation1969). Nonetheless, the name Platyceps wilkinsoni continued to be used in many subsequent studies (e.g., Feistmantel Citation1890, Moodie Citation1911, Chapman Citation1914, Watson Citation1919, Howchin 1925–Citation1930, Longman Citation1941). Romer (Citation1947) alternatively listed the species as ‘Platyceps’ wilkinsoni (see also Watson Citation1956, Hills Citation1958), with Kuhn (Citation1961) finally proposing the replacement name Platycepsion. Cosgriff (Citation1969) otherwise designated P. wilkinsoni the type species of Blinasaurus, a generic epithet that persisted (except in Shishkin Citation1973) until Warren & Marsicano (Citation1998) revived Platycepsion as the senior synonym. Witzmann & Schoch (Citation2022) recently demonstrated that NSWGS F12572 represents a larval brachyopid, as initially interpreted by Stephens (Citation1887c), thus we restrict P. wilkinsoni to distinguish the holotype only.

Notobrachyops Cosgriff, Citation1967

Type species

Notobrachyops picketti Cosgriff, Citation1967.

Notobrachyops picketti Cosgriff, Citation1967

1967, Notobrachyops picketti Cosgriff, p. K4–K5.

1973, Notobrachyops picketti (Cosgriff) Cosgriff, p. 1096.

Holotype

NSWGS F8258, an impression of the skull roof with parts of the occipital region.

Type locality, unit and age

Hurstville Brick Company quarry at Mortdale in metropolitan Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; Rouse Hill Siltstone Member of the Ashfield Shale in the Wianamatta Group (Sydney Basin), mid-Anisian (Middle Triassic) Aratrisporites parvispinosus Palynomorph Zone (Herbert Citation1983, Citation1997, Helby et al. Citation1987, Metcalfe et al. Citation2015).

Remarks

Cosgriff (Citation1967) initially named Notobrachyops picketti in an abstract, but later described the taxon in more detail (Cosgriff Citation1973). Warren & Marsicano (Citation1998) advocated placement of N. picketti within Brachyopidae, although its relationships remain uncertain (Warren & Marsicano Citation2000b).

Xenobrachyops Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1983

Type species

Xenobrachyops allos (Howie, Citation1972a) Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1983.

Xenobrachyops allos

1972a, Brachyops allos Howie, p. 270.

1983, Xenobrachyops allos (Howie) Warren & Hutchinson, p. 59.

Holotype

QM F6572, an isolated intact skull and palate ().

Type locality, unit and age

Duckworth Creek (QM L215) near Bluff in east-central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Xenobrachyops allos was initially referred to Brachyops Owen, Citation1855 by Howie (Citation1972a). Several mandibular (Warren Citation1981a, Warren Citation1981b, Jupp & Warren Citation1986) and pectoral girdle elements (Warren & Marsicano Citation2000b) have also been assigned to this taxon.

Banksiops Warren & Marsicano, Citation2000a

Type species

Banksiops townrowi (Cosgriff, Citation1974) Warren & Marsicano, Citation2000a.

Banksiops townrowi (Cosgriff, Citation1974) Warren & Marsicano, Citation2000a

1974, Blinasaurus townrowi Cosgriff, p. 7.

1998, Banksia townrowi (Cosgriff) Warren & Marsicano, p. 338.

2000, Banksiops townrowi (Cosgriff) Warren & Marsicano, p. 186.

Holotype

UTGD 87785, an isolated skull including the cranial roof and palate.

Type locality, unit and age

‘Old Beach’ locality on the eastern shore of the Derwent River north of Hobart in Tasmania, Australia; Knocklofty Formation (Tasmanian Basin) correlated with Induan to lower Olenekian (Lower Triassic) vertebrate assemblages by Ezcurra (Citation2014).

Remarks

Cosgriff (Citation1969, Citation1974) initially assigned Banksiops townrowi to Blinasaurus, with the preoccupied genus name Banksia Warren & Marsicano, Citation1998 replaced with Banksiops by Warren & Marsicano (Citation2000a).

CHIGUTISAURIDAE Rusconi, Citation1948

Keratobrachyops Warren, Citation1981a

Type species

Keratobrachyops australis Warren, Citation1981a.

Keratobrachyops australis Warren, Citation1981a

1981, Keratobrachyops australis Warren, p. 274.

Holotype

QM F10115, a fragmented skull with articulated mandibular rami ().

Type locality, unit and age

Duckworth Creek (QM L215) near Bluff in east-central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Keratobrachyops australis has been unambiguously classified within Chigutisauridae by Warren (Citation1981a), Sengupta (Citation1995), Damiani & Warren (Citation1996), Schoch & Milner (Citation2000), Warren & Marsicano (Citation2000b), and Dias-Da-Silva et al. (Citation2012).

Siderops Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1983

Type species

Siderops kehli Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1983.

Siderops kehli Warren & Hutchinson, Citation1983

1977, Jurassic labyrinthodont, Warren, p. 436.

1983, Siderops kehli Warren & Hutchinson, p. 5.

Holotype

QM F7882, an articulated skull, mandible, and largely intact postcranial skeleton incorporating vertebral column, ribs, limb girdles and both fore- and hind limbs ().

Type locality, unit and age

Locality west of Kennedy Peak on Kolane Station, ∼60 km north of Wandoan in southeastern Queensland, Australia; Westgrove Ironstone Member of the Evergreen Formation (Surat Basin); this site was constrained to a late Toarcian (Early Jurassic) maximum depositional age of 176.6 ± 2.0 Ma by Todd et al. (Citation2019). The Westgrove Ironstone Member is more broadly correlated with Pliensbachian to Aalenian (Lower to Middle Jurassic) strata across the Surat Basin (La Croix et al. Citation2022).

Remarks

Warren (Citation1977) published an initial short report on the discovery of QM F7882 and its novel stratigraphical occurrence as an unambiguous Jurassic temnospondyl. However, Siderops kehli was later formally named with an exhaustive description by Warren & Hutchinson (Citation1983). Siderops kehli is consistently resolved amongst brachyopoids (e.g., Warren & Marsicano Citation2000b, Ruta et al. Citation2007, Schoch Citation2013, Gee Citation2022), and classified within Chigutisauridae (Marsicano Citation1999). Other records of Jurassic temnospondyl fossils have since been reported from southern Africa (Kitching & Raath Citation1984, Steyer & Damiani Citation2005), Kyrgyzstan (Nessov Citation1988, Averianov et al. Citation2008), Mongolia (Shishkin Citation1991), China (Dong Citation1985, Maisch et al. Citation2004, Maisch & Matzke Citation2005), and Thailand (Buffetaut et al. Citation1994a, Citation1994b, Nonsrirach et al. Citation2021).

Koolasuchus Warren, Rich & Vickers-Rich, Citation1997

Type species

Koolasuchus cleelandi Warren, Rich & Vickers-Rich, Citation1997.

Koolasuchus cleelandi Warren, Rich & Vickers-Rich, Citation1997

1997, Koolasuchus cleelandi Warren, Rich & Vickers-Rich, p. 5.

Holotype

NMV P186213, associated right and left mandibular rami ().

Type locality, unit and age

West end of Rowells Beach, east of Potters Hill Road in Kilcunda on the Bass Coast of southern Victoria, Australia. Wagstaff et al. (Citation2020) correlated this locality with the ‘Wonthaggi Formation’ succession of the upper Strzelecki Group (Gippsland Basin); uppermost Barremian (Lower Cretaceous) Pilosisporites notensis Spore-pollen Zone ‘Group 1’ site category.

Remarks

The first specimen of Koolasuchus cleelandi was found in 1979, but comprised only an edentulous mandible fragment (NMV P156988) whose identifications ‘ranged from a crocodile to an ornithischian dinosaur or even a labyrinthodont amphibian’ (Flannery & Rich Citation1981, p. 197). Jupp & Warren (Citation1986, p. 120) stated that the ‘main obstacle to accepting NMV P156988 as a labyrinthodont amphibian is its Early Cretaceous age.’ However, subsequent discoveries have unambiguously confirmed the status of K. cleelandi as the geologically youngest temnospondyl (Warren et al. Citation1991, Warren et al. Citation1997) and member of the Gondwanan clade Chigutisauridae (Warren et al. Citation1997, Marsicano Citation1999). The recent recovery and forthcoming description of several partial skulls (e.g., Poropat et al. Citation2018, Warren & Marsicano Citation2000b) will undoubtedly yield new insights into the palaeobiology and relationships of K. cleelandi, which became the Victorian State Fossil Emblem in 2022.

REPTILIA Linnaeus, Citation1758

PARAREPTILIA Olson, Citation1947 (sensu Laurin & Reisz, Citation1995)

PROCOLOPHONOIDEA Romer, Citation1956

PROCOLOPHONIDAE Lydekker in Nicholson & Lydekker, Citation1889

Eomurruna Hamley, Cisneros & Damiani, Citation2021

Type species

Eomurruna yurrgensis Hamley, Cisneros & Damiani, Citation2021.

Eomurruna yurrgensis Hamley, Cisneros & Damiani, Citation2021

1970, ?Paliguanid, Bartholomai & Howie, p. 1063.

1971, Procolophon, Romer, p. 114.

Citation2006, Arcadia procolophonid, Cisneros Martínez, p. 76.

2021, Eomurruna yurrgensis Hamley, Cisneros & Damiani, p. 560.

Holotype

QM F18335, an articulated skull and mandible with accompanying postcranial skeleton incorporating vertebral column and ribs with the pectoral and pelvic girdle and right fore- and hind limb elements ().

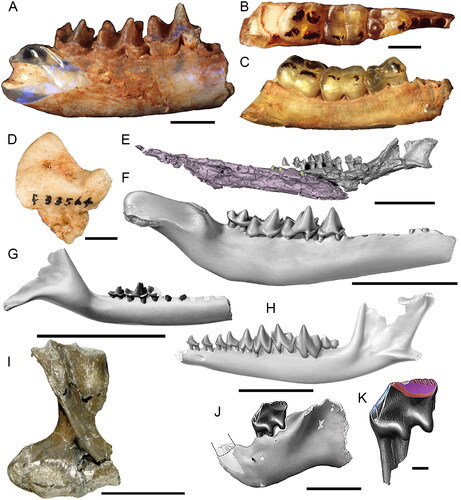

Fig. 3. Australian Mesozoic procolophonids, basal neodiapsids, and ichthyosaurians. A, Eomurunna yurrgensis (QM F49510; referred specimen) skull and mandible in right lateral view. Scale = 3 mm. B, Eomurunna yurrgensis (QM F18335; holotype) skull and postcranial skeleton. Scale = 5 cm. C, Kudnu mackinlayi (QM F9181; holotype) partial skull in left lateral view. Scale = 5 mm. D, Kudnu mackinlayi (QM F9182; referred specimen) partial skull in left lateral view. Scale = 5 mm. E, Platypterygius australis (QM F2453; referred specimen), skull and partial skeleton. Scale = 30 cm.

Type locality, unit and age

Duckworth Creek (QM L215) near Bluff in east-central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Eomurruna yurrgensis is the only procolophonid currently documented from Australia (Hamley et al. Citation2021). Abundant remains have been referred to this taxon from the ‘The Crater’ locality (QM L78) of the Arcadia Formation (), including an articulated skull and mandible (QM F6704) that Bartholomai & Howie (Citation1970) identified as a possible paliguanid. Romer (Citation1971) latter attributed this specimen to Procolophonidae, thereby establishing the classification recognized by all subsequent studies (Warren Citation1972, Colbert & Kitching Citation1975, Molnar Citation1982, Citation1991, Hamley et al. Citation2021).

EUREPTILIA Olson, Citation1947

DIAPSIDA Osborn, Citation1903

NEODIAPSIDA Benton, Citation1985

Kudnu Bartholomai, Citation1979

Type species

Kudnu mackinlayi Bartholomai, Citation1979.

Kudnu mackinlayi Bartholomai, Citation1979

1979, Kudnu mackinlayi Bartholomai, p. 231.

Holotype

QM F9181, the anterior section of a cranium with articulated dentary rami ().

Type locality, unit and age

‘The Crater’ locality (QM L78) near Rolleston in central Queensland, Australia; Arcadia Formation of the Rewan Group (Bowen Basin), correlated with the lower to middle Olenekian (Lower Triassic) upper Lunatisporites pellucidus and Protohaploxypinus samoilovichii palynomorph zones (Metcalfe et al. Citation2015, Mays et al. Citation2020).

Remarks

Kudnu mackinlayi () was initially identified as a lepidosaur and assigned to Paliguanidae by Bartholomai (Citation1979). Subsequent interpretations have ranged from an indeterminate lepidosauromorph (Benton Citation1985, Conrad Citation2008), osteologically immature prolacertiform (Evans Citation2003), a possible procolophonid (Evans & Jones Citation2010), or a neodiapsid or saurian of uncertain affinity (Ezcurra et al. Citation2022).

ICHTHYOSAUROMORPHA Motani, Jiang, Chen, Tintori, Rieppel, Ji & Huang, Citation2015

ICHTHYOSAURIFORMES Motani, Jiang, Chen, Tintori, Rieppel, Ji & Huang, Citation2015

ICHTHYOPTERYGIA Owen, Citation1840

ICHTHYOSAURIA de Blainville, Citation1835

OPHTHALMOSAURIA Motani, Citation1999

BRACHYPTERYGIIDAE Cortés, Maxwell & Larsson, Citation2021

Platypterygius von Huene, Citation1922

Type species

Platypterygius platydactylus (Broili, Citation1907) von Huene, Citation1922.

Platypterygius australis (M’Coy, Citation1867) McGowan, Citation1972 sensu Zammit, Citation2010

1867, Ichthyosaurus australis M’Coy, p. 356.

1888, Ichthyosaurus marathonensis Etheridge, p. 408.

1922, Myopterygius marathonensis (Etheridge) von Huene, p. 96, 98.

1944, Myopterygius australis (M’Coy) Teichert & Matheson, p. 169.

1972, Platypterygius australis (M’Coy) McGowan, p. 16.

1990, Platypterygius longmani Wade, p. 120.

2003, Platypterygius longmani Kear, p. 284.

2005a, Platypterygius longmani Kear, p. 584.

Neotype

NMV P12989, incomplete cranium comprising nasal and orbital regions with an articulated basioccipital and atlas-axis complex. The type material also includes associated vertebral centra NMV P12992, NMV P22653, NMV P22654, and NMV P22656–NMV P22661 (see Zammit Citation2010).

Type locality, unit and age

Reportedly collected at ‘Lat. 21° 13′S and Long. 143° 25′E (M’Coy 1865), north Queensland’ (Hell Citation2001, p. 294). These coordinates pinpoint a locality between the O’Connell and Walker creeks (or ‘Walker and O’Connell Creeks left bank of the river’: Hell Citation2001, p. 294), south of the Flinders River and southwest of Hughenden in central-northern Queensland, Australia. Zammit (Citation2010) listed the source unit as the Allaru Mudstone in the Wilgunya Subgroup of the Rolling Downs Group (Eromanga Basin); correlated with the upper Albian (Lower Cretaceous) Endoceratium ludbrookae Dinocyst Zone (sensu Partridge Citation2006) by Foley et al. (Citation2022).

Remarks

McGowan (Citation1972) established the generic reassignment of Platypterygius australis (), which was later updated by McGowan & Motani (Citation2003). Zammit (Citation2010) proposed the neotype cranium, NMV P12989, to replace the historically unidentified holotype that was anecdotally attributed to non-diagnostic vertebral centra (see Wade Citation1984, Hell Citation2001, Zammit Citation2010). Arkhangelsky (Citation1998, p. 612) additionally created the subgenus P. (Longirostria) australis to accommodate ‘Platypterygius longmani’ and Platypterygius (Longirostria) hauthali von Huene, Citation1927. However, McGowan & Motani (Citation2003) synonymized Longirostria with Platypterygius, a genus that is also now conceptually restricted to the type species, Platypterygius platydactylus (e.g., Cortés et al. Citation2021). Accordingly, Fischer (Citation2016) concluded that P. australis could be a potential type species for the genus Myopterygius von Huene, Citation1922, which was initially erected to accommodate the species group incorporating ‘Ichthyosaurus’ marathonensis (Huene Citation1922). The intended type species of Myopterygius was probably ‘Ichthyosaurus’ campylodon (Carter Citation1846), although this was never formally designated (Fischer Citation2016). Consequently, Fischer (Citation2016) transferred ‘I.’ campylodon to Pervushovisaurus Arkhangelsky, Citation1998—another subgeneric synonym of Platypterygius (see McGowan & Motani Citation2003) elevated to genus-level by Fischer et al. (Citation2014). This decision has rendered the formal generic assignment of P. australis uncertain. Furthermore, the priority of Myopterygius versus Longirostria remains unresolved since neither epithet is diagnostically consistent with P. australis. We, therefore, provisionally retain the referral of P. australis to Platypterygius pending a more detailed taxonomic assessment.

SAUROPTERYGIA Owen, Citation1860b

PISTOSAUROIDEA Baur, 1887 in Zittel, 1887–Citation1890

PLESIOSAURIA de Blainville, Citation1835

PLIOSAURIDAE Seeley, Citation1874

BRACHAUCHENINAE Williston, Citation1925 (sensu Benson & Druckenmiller Citation2014)

Kronosaurus Longman, Citation1924

Type species

Kronosaurus queenslandicus Longman, Citation1924, as revised by McHenry (Citation2009).

Kronosaurus queenslandicus Longman, Citation1924

1924, Kronosaurus queenslandicus Longman, p. 26.

1991, Kronosaurus queenslandicus? Molnar, p. 613.

2022, Eiectus longmani Noè & Goméz-Pérez, p. 6.

Type material

QM F1609 (holotype), weathered paired jaw bone fragments containing remnants of six teeth. QM F18827 (proposed neotype), articulated skull and mandible () with associated cervical and pectoral vertebrae, components of the pectoral girdle and proximal end of the humerus (see McHenry Citation2009, pp. 180–185).

Fig. 4. Australian Mesozoic sauropterygians. A, Eiectus longmani (MCZ 1285; holotype) in left lateral view (Wikimedia Commons). Scale = 1 m. B, Kronosaurus queenslandicus (QM F18827; proposed neotype [part]) skull in dorsal view (modified from McHenry Citation2009). Scale = 30 cm. C, Elasmosauridae incertae sedis (QM F3567; holotype [part] of Woolungasaurus glendowerensis) partial forelimb. Scale = 5 cm. D, Opallionectes andamookaensis (SAMA P24560; holotype) partial postcranial skeleton in dorsal view. Scale = 30 cm. E, Polycotylidae incertae sedis (AM F6268; holotype [part] of Cimoliasaurus leucoscopelus) cervical vertebra in anterior view. Scale = 3 cm. F, Leptocleidus clemai (WAM 92.8.1; holotype [part]) humerus of assigned specimen in dorsal view. Scale = 3 cm. G, Umoonasaurus demoscyllus (AM F99374; holotype [part]) partial skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. Eromangasaurus australis (QM F11050; holotype [part]) skull in H, left lateral and I, right oblique ventral views. Scale = 5 cm.

![Fig. 4. Australian Mesozoic sauropterygians. A, Eiectus longmani (MCZ 1285; holotype) in left lateral view (Wikimedia Commons). Scale = 1 m. B, Kronosaurus queenslandicus (QM F18827; proposed neotype [part]) skull in dorsal view (modified from McHenry Citation2009). Scale = 30 cm. C, Elasmosauridae incertae sedis (QM F3567; holotype [part] of Woolungasaurus glendowerensis) partial forelimb. Scale = 5 cm. D, Opallionectes andamookaensis (SAMA P24560; holotype) partial postcranial skeleton in dorsal view. Scale = 30 cm. E, Polycotylidae incertae sedis (AM F6268; holotype [part] of Cimoliasaurus leucoscopelus) cervical vertebra in anterior view. Scale = 3 cm. F, Leptocleidus clemai (WAM 92.8.1; holotype [part]) humerus of assigned specimen in dorsal view. Scale = 3 cm. G, Umoonasaurus demoscyllus (AM F99374; holotype [part]) partial skull in dorsal view. Scale = 5 cm. Eromangasaurus australis (QM F11050; holotype [part]) skull in H, left lateral and I, right oblique ventral views. Scale = 5 cm.](/cms/asset/76e737d8-bff1-4c1a-b634-2ceafdfc39b9/talc_a_2228367_f0004_c.jpg)

Type locality, unit and age

QM F1609 was derived from an unspecified locality in the Hughenden region of central-northern Queensland, Australia (Longman Citation1924). Longman (Citation1930, p. 1) also attributed two incomplete propodials (QM F2137) and some weathered bone fragments (apparently occurring together with a caudal vertebral series: Romer & Lewis Citation1959) from a locality ‘two miles [∼3.2 km] south of Hughenden’. QM F18827 was recovered ‘from the airstrip on Lucerne Station, [∼9 km] north of Richmond’ (McHenry Citation2009, p. 180). McHenry (Citation2009) identified the type unit as the Toolebuc Formation in the Wilgunya Subgroup of the Rolling Downs Group (Eromanga Basin); correlated with the upper Albian (Lower Cretaceous) Canningopsis denticulata and lower Endoceratium ludbrookae dinocyst zones (sensu Partridge Citation2006) by Foley et al. (Citation2022).

Remarks

Despite early reports of ‘comprehensive undescribed material’ being available for study at the QM (Persson Citation1960, p. 4), Welles (Citation1962, p. 48) designated Kronosaurus queenslandicus a nomen vanum (= name designated on fragmentary type remains: Mones Citation1989), and recommended establishment of a neotype based on the ‘material at Harvard University’ (presumably referring to the incomplete skull and skeleton MCZ 1285: White Citation1935, Anonymous Citation1959, Fletcher Citation1959, Romer & Lewis Citation1959). Persson (Citation1960, p. 4) likewise refrained from documenting the QM specimens ‘before a description of the Harvard skeleton has been published’. Nevertheless, White (Citation1935) and Romer & Lewis (Citation1959) had already described MCZ 1285 and a second premaxillary rostrum with associated symphyseal section of the mandible (MCZ 1284: see White Citation1935) in some detail.