Abstract

The Nganjarli site complex, which includes a rich body of rock art, shell middens and artefact scatters, has been identified by the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation (MAC) as the primary location within Murujuga National Park for tourism and interpretation facilities. Murujuga National Park lies on the north-west coast of Western Australia, and within the Dampier Archipelago (including Burrup Peninsula) National Heritage Place. MAC owns and co-manages the National Park with the Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions. Facilities have been upgraded to accommodate increasing tourist numbers and enhance their cultural experience at Nganjarli. Archaeological evidence was documented ahead of the installation of a boardwalk and concrete walking trails for viewing rock art. The national heritage values of this place are demonstrated, and we outline how existing co-management has mobilised contemporary cultural values and the aspirations of the Murujuga custodians. We document the role of innovative scientific approaches in the interpretive strategy for Nganjarli. New recording techniques and digital imaging demonstrate the diversity of animal motifs in the rock art near the installed boardwalk and identify opportunities for further digital interpretation of this significant landscape. Geochemical testing of surface lithic artefacts using X-ray fluorescence indicates mixed sourcing in the preferred lithics despite this being a tool-stone rich environment. Surface shell derives from targeted harvesting of a single species. The combined archaeological evidence indicates that Nganjarli has functioned as an aggregation locale through time. The rock art assemblage indicates that occupation here began during the earlier phases of art production. All these findings have been incorporated into the interpretative facilities in the tourist area.

Introduction

Murujuga, as the Dampier Archipelago (including Burrup Peninsula) National Heritage Place has become known, is on the Pilbara coast of Western Australia (). It is a land- and seascape with some of the worlds’ most abundant and diverse rock art (Lorblanchet Citation2018; Mulvaney Citation2015). On Australia’s National Heritage List since 2007, Murujuga is widely recognised for its cultural and scientific values (McDonald and Veth Citation2006, Citation2009). It is renowned as having over one million petroglyphs which demonstrate the first use of this arid landscape by people arriving on the north-west shelf over 50,000 years ago (Veth et al. Citation2017), the bountiful lifestyle of hunter-fisher-gatherers along this coastline throughout the Holocene (McDonald Citation2015; Mulvaney Citation2013), and the arrival of historic explorers, whalers, pearlers and pastoralists (Paterson et al. Citation2019a, Citation2019b). This landscape is of great cultural significance to the Ngarda-Ngarli – the Ngarluma, Yinjabarndi, Mardudunhera, Yaburara and Wong-Goo-Tt-Oo of the coastal Pilbara.

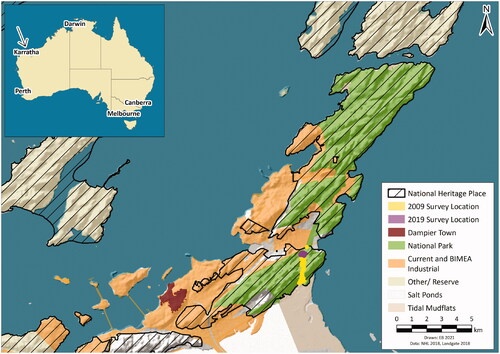

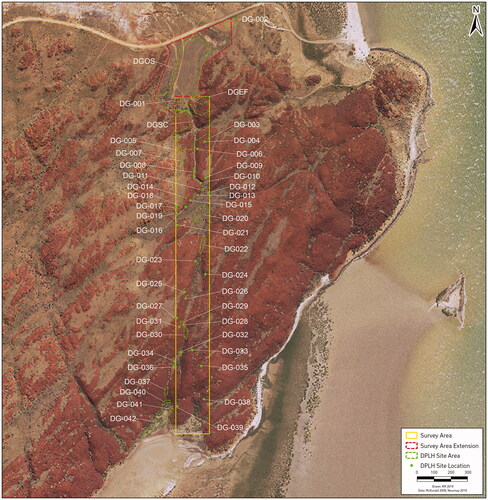

Figure 1. The conservation estate and industry lands across the central and northern Burrup, within the National Heritage Listed Place, showing the two Nganjarli survey locations.

Nganjarli, formally known as Deep Gorge (and in the 1980s, as Patterson Valley) has long been the focus of visitors interested in seeing Murujuga’s rock art. Located near a popular beach and with relatively easy access, it is a place known to the Traditional Owners and other locals alike. With growing public awareness through the National Heritage List and declaration of the Murujuga National Park, Nganjarli has seen an increase in visitor numbers and a concomitant escalation in impact, including graffiti. With consent of the Traditional Owners, represented by the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation (MAC), the Department of Biodiversity Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) proposed to establish visitor management facilities and information signage. This proposal involved construction of a formal car park, formed footpaths and raised platforms and boardwalks. Provisional impacts of the proposed developments on cultural heritage were assessed by consultants working with Traditional Owner representatives (data and reports not publicly available). However, detailed recording of the rock art had not been undertaken when the design and placement of the viewing platforms were finalised.

With permission from, and the involvement of Traditional Owner elders and MAC, a detailed archaeological investigation was undertaken by UWA and Rio Tinto heritage professionals, funded by the Rio Tinto—Commonwealth Government Conservation Agreement. This paper discusses the importance of a collaborative research approach in the consideration of tourism infrastructure placement and potential benefit. The archaeological and cultural evidence at Nganjarli highlights how interpretative facilities can be developed to engage visitors in the rich scientific value of the archaeology, showcase the unparalleled creative genius of the petroglyphs, and acknowledge a deep time sequence of occupation across the broader landscape.

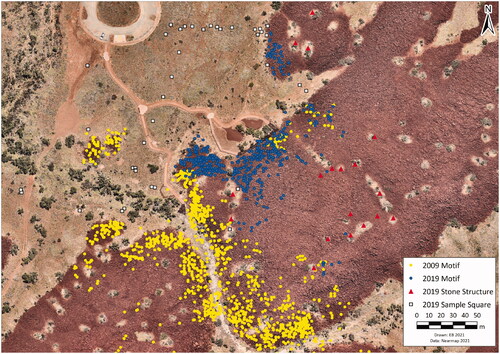

Nganjarli falls within the inner geological region of the Dampier Archipelago, where the exposed rocks are dominated by Archaean Gidley Granophyre lithologies (c. 2,725 Ma). Coarse-grained massif gabbro block and bedrock slopes dominate the area where the public facilities have been installed, and these were partially surveyed in an earlier investigation (). This Deep Gorge transect (2 km × 200 m) was surveyed in 2009, focussing on an identified management priority considered then as the most suitable location for the installation of tourist facilities (McDonald Citation2009). That survey recorded 42 sites that included petroglyphs (more than 3,470 engraved motifs), stone artefacts, quarries, middens, scarred trees, grinding patches, stone features, and combinations of these site types (McDonald Citation2009: Table 43).

Figure 2. Deep Gorge systematic survey showing location of the recorded sites (after McDonald CHM Citation2009: Figure 12).

Adjacent to the northern end of this transect, surface archaeological evidence was continuous over the spinifex-covered plain, along the creekline and all adjacent rock features (gorge wall, rock piles and knolls). Much of the stone artefacts and shell scatters are within the area proposed by DBCA for the tourism upgrade amenities. This site was originally recorded as the Deep Gorge Open Site and is contiguous with the Deep Gorge Site Complex and petroglyph samples recorded on the outer flanks (DGEF) and a boulder pile near the carpark (DG-01). All petroglyphs within the transect through the main gorge (DGSC) area, the then-proposed focus for tourism management, were recorded. The northern outer flank was only partially recorded then due to time constraints. The open site was already impacted by the existing dirt track, parking area and walking trails. In addition, the installation of a monitoring station for a nearby chemical plant further impacted the archaeological open site. As it was envisaged that most of the tourist facilities would impact the deposits adjacent to the rock art, recommendations at the time required further investigation because of their excellent potential for providing intact occupation evidence.

Murujuga management

The Burrup and Maitland Industrial Estates Agreement (BMIEA) secured development of the Burrup and Maitland Strategic Industrial Areas through a compulsory acquisition of any native title rights and interests in land on the Burrup Peninsula. This agreement preceded the Federal Court’s native title determination made in relation to the Dampier Archipelago (Flanagan Citation2007). MAC administers the BMIEA on behalf of the Contracting Parties, who are native title claimant groups for the Dampier Archipelago and native title holders in the adjacent Pilbara coastal lands. The BMIEA formalised both the industrial gazetted lands (c. 67 km2 of the Burrup) as well as the lands which would be transferred in freehold title to MAC and managed as a National Park (c. 51 km2; see ).

Murujuga National Park was declared in 2013, the 100th National Park in Western Australia, and the first to be owned by Traditional Owners and co-managed with DBCA. The 51.2 km2 National Park is almost entirely within the National Heritage Listed Place. The remainder of the National Heritage Listed land on the Burrup is within Rio Tinto held leases at the southern Burrup or has been zoned for future BMIEA industrial uses (). Heritage sites and places here are managed by two legislative frameworks: the State’s Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972 (as amended) and the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

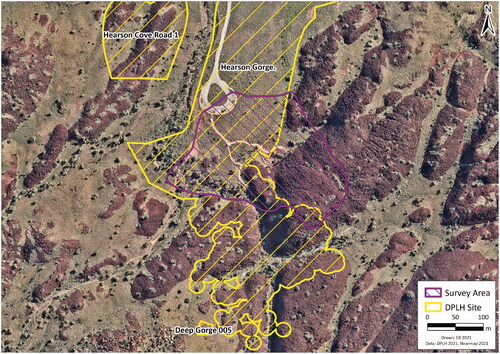

In 2019, at the request of MAC, a survey and recording exercise was undertaken in advance of the installation of tourist facilities adjacent to the outer slopes of Nganjarli (the DGEF area; ). This area was chosen by MAC as the focus for visitor interpretation because of cultural concerns about sensitive imagery inside the gorge, and engineering issues over the installation of a boardwalk in an active drainage system that experiences annual cyclones. Given the cultural sensitivities of some engraved imagery on this outer slope, it was important to know the precise locations of all imagery so that appropriate signage and interpretative material could be directed towards what was suitable for public consumption. The DGEF area had not been surveyed intensively during the 2009 survey, nor recorded for heritage impact assessment for the proposed installation of tourist facilities. The aim of this current investigation was to provide appropriate baseline management data to support avoidance and interpretation ahead of the proposed boardwalk installations.

Methods used

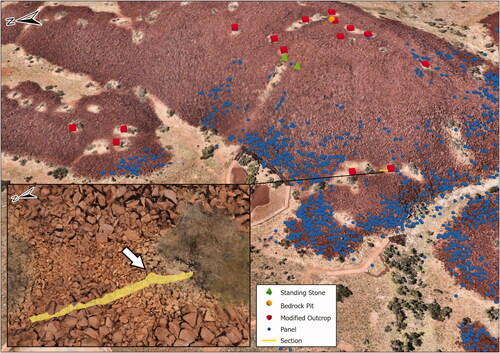

Rock art data collection followed procedures that have been established over the past seven years on Murujuga by the authors during the UWA—Rio Tinto Rock Art Field School and the Murujuga: Dynamics of the Dreaming ARC Linkage Project, building on the pioneering work of the Western Australian Museum (Department of Aboriginal Sites (DAS) Citation1984) and subsequent research (McDonald and Veth Citation2006; Mulvaney Citation2010). Three teams of rock art specialists systematically covered the survey area to complete the coverage of this landscape. Another team recorded surface lithic artefacts and midden material. An additional team ranged further over the slopes, recording stone features (see also Beckett Citation2021) and using a drone to obtain aerial imagery of the place and significant cultural features (). Numerous excavations and recordings of surface artefact scatters have been undertaken within Murujuga, establishing a reliable pattern of the character of archaeological material (e.g. Department of Aboriginal Sites (DAS) Citation1984; Harris Citation1988; Lorblanchet Citation2018; Veth Citation1982). Bivalves (Tegillarca cf. zanzibarensis; formerly known as Anadara granosa; Lisa Kirkendale, Western Australian Museum, 2/9/2021, personal communication) dominate the mollusc assemblages, with some gastropod (Terebralia sp.) and much smaller proportions of rock platform and other tidal species.

Figure 3. Nganjarli 2019 survey area in relation to Hearson Gorge and other sites registered with the Department of Planning Lands and Heritage (DPLH).

Rock art

Each block within the survey area was examined and any surface with rock art (a panel) was photographed and recorded in detail. This included the dimensions of the block and that of each panel and individual petroglyph (motif). An iPad Mini running FileMakerPro© recording forms was used to document recorded attributes of both panels and motifs. The location of each panel was recorded using handheld Garmin GPS, crosschecked by the iPad’s in-built GPS. This data redundancy ensured that all panels could be relocated towards the end of the recording programme by a team using a Differential GPS (Trimble).

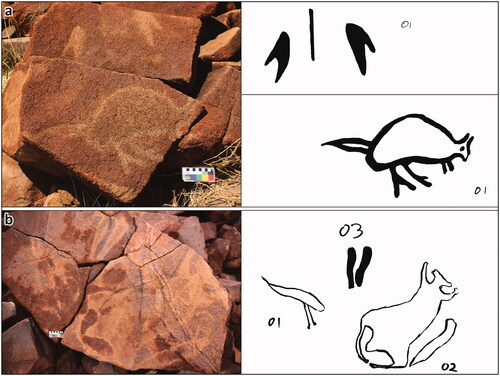

An innovation introduced for this project was that each recording team used an iPad Pro running ProCreate© to make detailed sketches of each petroglyph in the field (). Our standard recording methodology previously involved sketches on paper. This digital recording approach provides a more rapid and accurate recording of each motif and its relative position on the panel, constrained only by Pilbara temperatures and harsh sunlight and the effects these have on electronic equipment.

Stone structures

All stone structures were recorded using the recording forms which have been developed during the Murujuga: Dynamics of the Dreaming Project employing the typology developed by Beckett (Citation2021). All features (standing stones, clearings/enclosures, and bedrock pits) were measured and characterised using a Trimble NOMAD© recording device (and recording forms), as well as being located using the DGPS ().

Lithic artefacts

No excavation was undertaken, and no artefacts or shells were collected from the survey area.

The artefacts, mainly unmodified flakes and flake sections, were recorded by a student team of two archaeologists and one geologist. Surface artefacts were recorded along two transects, using one metre sample squares and surface artefact counts (). Recording of stone tools used attributes as described in Clarkson and O’Connor (Citation2006) to identify technological change and raw material use which may reflect changes in mobility and provisioning (e.g. Kuhn Citation1994), risk investment (Hiscock Citation2002), and subsistence procurement and maintenance across time and space (Andrefsky Citation2005). Digital cameras were used to photograph all squares and their artefacts. The attributes recorded have been used consistently across the archipelago in the recent Linkage Project (McDonald et al. Citation2015; McDonald et al. Citationin press; and see Veth Citation1982).

A geochemical provenance analysis, using non-destructive Portable X-Ray fluorescence (pXRF), was conducted using the Niton XL3t GOLDD + pXRF. Each assay analysis was 60 seconds using Test All bulk mode, cycling through four filters. The standards used were 99.995 SiO2 (pure silica standard) and NIST 2709a (soil and sediment standard). To ensure that the pXRF was reproducing accurate geochemical analyses, each standard was analysed before each session for comparison against a control dataset (defined by the National Institute of Standards and Technology).

Shellfish remains

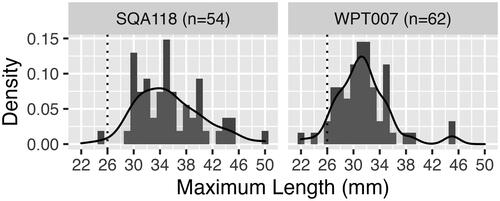

Mollusc shell was also recorded from two sample squares. Only bivalves (Tegillarca cf. zanzibarensis) were present. For these bivalves, intact umbo and hinges were classified as left or right, with the larger counted category (L/R) providing the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI). Lengths of intact valves were measured between anterior and posterior ends, to understand size distribution targeted by the shellfish gatherers.

Statistical analysis of the recorded shell species was conducted using R (R Core Team Citation2020), along with the tidyverse packages (Wickham et al. Citation2019), and the ggcorrplot package (Kassambara Citation2019).

Survey results

The survey area (see ) of 45,432 m2 targeted the outer face of the dissected gabbro massif, the slope rising some 40 m at a variable incline of 45–60°. This is adjacent to the spinifex-covered stony plain, the focus of the proposed boardwalk and pathways. One week was spent with up to 15 people each day participating in this detailed cultural heritage investigation, assisted at times by MAC rangers and Elders.

Rock art

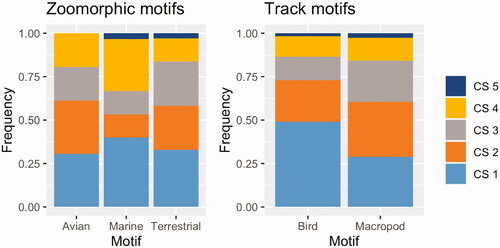

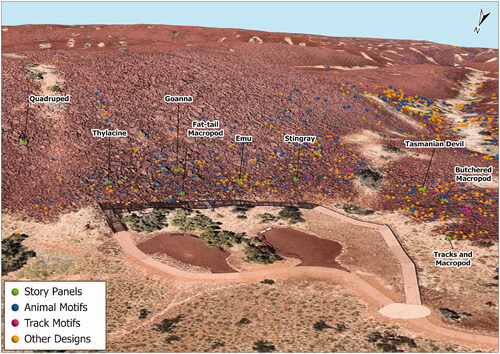

Within an area of 18,229 m2 a total of 559 panels with 1,103 identified petroglyphs were recorded on the outer flanks of Nganjarli (; ). This assemblage comprises mostly geometric motifs (41.8%) followed by zoomorphic (21.9%), anthropomorphic (22.3%) and track motifs (14%). This ratio of broad subject categories is consistent with the general pattern observed across the archipelago (e.g. McDonald and Veth Citation2009; Mulvaney Citation2015; Vinnicombe Citation2002). Here we focus on the zoomorphic and track motifs, to provide the focus of public interpretation on the now-installed boardwalk and trail. Due to cultural sensitivities and under the direction of Traditional Owners and Custodians, human-like and geometric motifs are not discussed in this paper.

Table 1. Nganjarli Subject Proportions, Identifiable motifs grouped by class.

Zoomorphic motifs

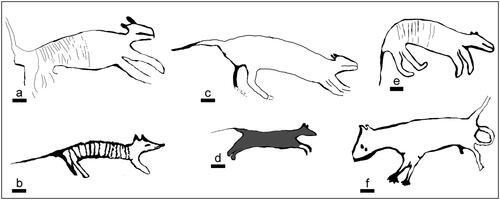

As with all four categories, the occurrence of animal-like images is spread across the survey area with some spatial variations and subject clusters. These are descriptor labels for recording purposes and do not imply an understanding of the artist’s intention nor necessarily a taxonomically correct identification. However, the ascribed species often does conform with the interpretation given by the Traditional Owners and Custodians of this cultural iconography. The Nganjarli walkway area has a high percentage of quadruped motifs, including six representations of the Thylacine (Tasmanian tiger), a relatively common motif across the archipelago (Mulvaney Citation2009). These are found in a variety of styles indicating several production phases over considerable time (; Mulvaney Citation2015:235). Our classification includes solid and/or outline forms without internal stripes, based on a range of diagnostic features additional to body stripes (see Clegg Citation1978; Mulvaney Citation2015:228). Two Nganjarli thylacines are situated on the same block – on opposite faces – above the walkway. One is heavily weathered with low contrast state and a distinctive mouth, an older stylistic trait (Mulvaney Citation2015); the other is more stylised and fresher in appearance (). One other ‘thylacine’ petroglyph, without stripes, has anatomical detail with eyes, penis and anus or pouch (). Two additional thylacine motifs on adjacent blocks are on the opposite side of Nganjarli, almost equal distance to the west, as are these two recorded to the east of the valley opening (McDonald Citation2009).

Figure 6. Thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) depictions, all with the elongated body, proportionally large head, limbs of comparable length, straight extended tail and in four cases with the vertical-aligned strips within the body typical of this species (scale bar = 10 cm).

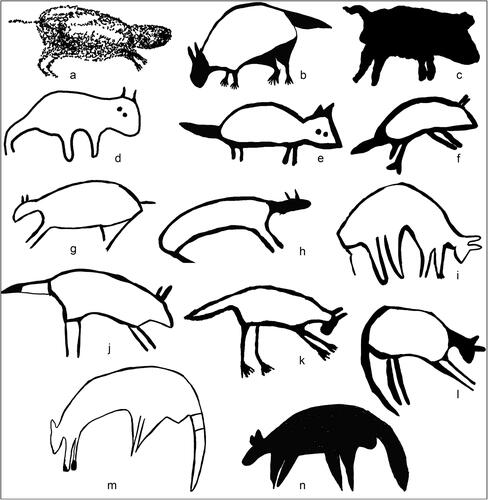

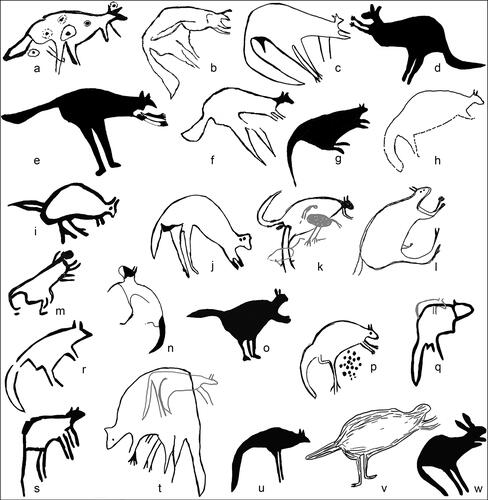

Seventeen other quadruped motifs are less diagnostic to species (). For classification purposes, quadrupeds have back legs the same length as front legs. Aboriginal Custodians see six of these as Tasmanian Devil (). As with the thylacine depictions, these species, now extinct on the mainland, demonstrate distinctive earlier Murujuga artistic conventions (Mulvaney Citation2013).

Figure 7. Quadruped depictions, some representing Tasmanian devil (a–f) and others less diagnostic (j–n), possibly Northern quoll (j,k).

The 68 macropod depictions (defined by their back legs being longer than their front legs) represent 30% of the recorded zoomorphic images. This is a stylistically diverse group (; see Harper Citation2010; McDonald and Veth Citation2006; Mulvaney Citation2015; Stewart Citation2016). Macropod images display the greatest range in overall motif size: from 11 cm–174 cm in length. The only other larger zoomorphs are a bird (emu −15 cm × 127 cm), a quadruped (11 cm × 131 cm) and a reptile (9 cm × 130 cm). There are two endemic macropod species across the Dampier Archipelago (Macropus robustus, Euro or wallaroo; and Petrogale rothschildi Rothschild’s rock-wallaby), although the latter is now rare on the Burrup and other inner islands due to feral animal predation. Macropus rufus (Red kangaroo) is common throughout mainland Pilbara (Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) Citation2006) and would have been prevalent prior to islandisation (c. 7,000 years ago). Based on anatomical proportions and stylistic attributes, there are many depictions of this species amongst the older Murujuga rock art (Stewart Citation2016).

Figure 8. Macropod depictions including a possible extinct fat tailed species with a distinctive bulge-tail (a–f), others with more standard tail shape and thickness; note the greyed motifs occur on the same panels as the motifs shown.

One distinctive style of Pilbara macropod has a marked bulge to the tail. Known as the ‘fat-tail macropod’, it has been postulated that these depictions may be an extinct species or conversely an artistic convention emphasising the value of the tail (Brown Citation1983, Citation2018). This style is argued to be Pleistocene in age (Brown Citation2018; Mulvaney Citation2013). Stylistic traits found in the inland examples around Mt Tom Price, c. 240 km inland and south-east from Murujuga, include overall small motif size (<30 cm), elongated body, narrowing towards the head and with proportionally small head (Brown Citation1983; McDonald Citation2021; Mulvaney Citation2009). On Murujuga, there are many much larger pecked examples of this motif, along with others which are closer in size and form to the inland examples. Similar design traits are present in other species depictions, which supports the bulge element being related to a specific tail structure (see Mulvaney Citation2015:244; McDonald Citation2021; although see Stewart Citation2016). There are six fat-tail macropods (9% of macropod depictions) in the Nganjarli walkway sample (). These motifs are clustered along a 60 m section of the slope, with one (near the base of the slope) on an angular block that has fallen into its current position.

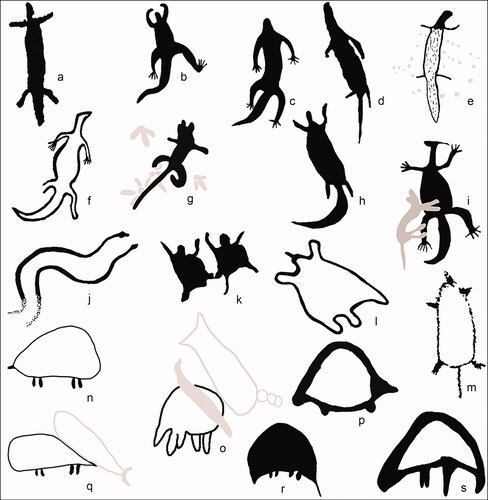

Lizard and echidna motifs comprise 9% and 8% respectively of the zoomorphic petroglyphs recorded (see ). The four snake depictions include sinuous or coiled configurations (). Most lizard motifs are monitor representations, with several that may be dragon or skink representations (). The echidna is well represented in this Nganjarli assemblage (n = 17). As with most Murujuga fauna, this animal is usually represented in profile, although there are a few in flattened, splayed ‘road-kill’ perspective (). One example has relatively long legs and snout, distinct from the more common form depicted and is interpreted here as representing the extinct long-beaked Zaglossus hacketti ().

Figure 9. Reptile (a–i), snake pair (j) and echidna depictions (k–s), the latter in profile and flattened, splayed view perspective; including one petroglyph that may represent Zaglossus hacketti (s).

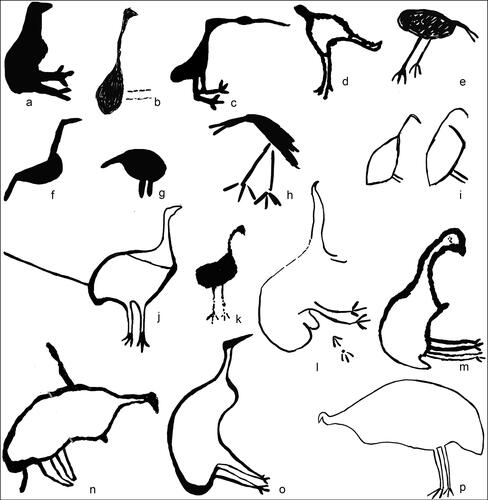

Bird motifs include both stylised and identifiable species based on anatomical elements and confirmed by Aboriginal Custodians. In the Nganjarli sample area there are eleven emu, two bush turkey and one ibis (). The bush turkey (Ardeotis australis) and the emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae) due to their habitat range are pre-islandisation fauna. In two cases, two emu-like images are on the same panel, and several of the emus have paired eyes as a graphic element. This stylistic convention is found in both macropod and anthropomorphic figures of relatively early phases of Murujuga’s artistic tradition, as well as being found more widely across the Pilbara and into the Western Desert (McDonald and Veth Citation2013).

Figure 10. Bird depictions showing the variation in form and graphic attributes; bustard (j) and emus (l–p) are the more diagnostic species.

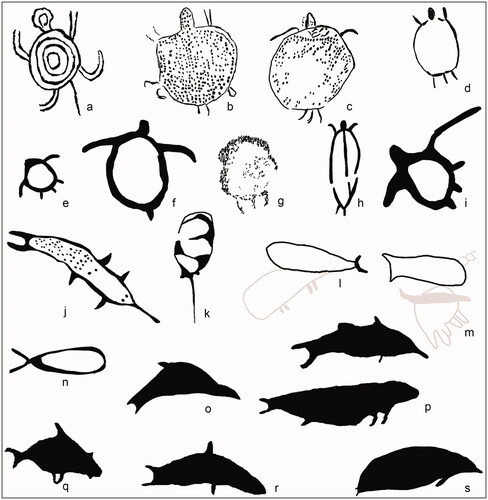

Turtles represent 7% of this engraved zoomorphic repertoire. Six marine turtle species inhabit the coastal waters of the archipelago and are identifiable in the rock art (de Koning Citation2014). There are several Nganjarli examples that are likely to be fresh-water species; with equal length limbs and fore-limbs not curved back as with flippers on marine species (). Fresh water turtles are not currently known on Murujuga but would have been present here when this was an inland arid range. All these non-marine examples are heavily weathered, with a deep profile, characteristic of the early artistic traditions of Murujuga.

Figure 11. Marine faunal depictions including turtle (marine and freshwater; a–i), sawfish (j) and stingray (k), and less-diagnostic marine mammals and fish (l–r); note the greyed motifs occur on the same panels as the motifs shown.

Two unusual marine fauna depictions are a sawfish and a stingray. Stingrays are rare in the Murujuga repertoire, and there is only one other known example of a sawfish (Lorblanchet Citation2018). The stingray is placed on a prominent near-vertical block face, is relatively large (94 × 38 cm) and has internal decoration (). The sawfish is also relatively large (93 × 30 cm), and although roughly pecked it displays good anatomical detail (including rostrum, pectoral and pelvic fins: ).

Of the few fish and other marine petroglyphs in this study, some 70% appear weathered and of relatively low contrast. Only one marine image has a fresh appearance (CS5; ). While mindful of specific lithologies and physical properties, contrast state has been established as a convenient indicator of relative age, with marine subjects usually within the higher contrast range (Mulvaney Citation2015). The physical and geochemical properties of the gabbro bedrock along this slope may explain this anomaly from the norm of marine subjects. In style, however, this Nganjarli ‘fish’ motif is pecked more deeply into the rock crust and often with a ‘U-shaped’ tail that differs from the majority of Murujuga fish images. This characteristic would seem to indicate greater antiquity than the majority of Murujuga marine fauna depictions ().

Table 2. Nganjarli Contrast State, as a measure of weathering exposure as a proxy for relative chronology, in relation to motif class.

While depictions of terrestrial fauna outnumber bird depictions (almost 4:1), avian tracks outnumber macropod tracks at Nganjarli (1.5:1; ). Both bird and macropod track motifs are mostly solid, with linear forms also common (). Linear bird and macropod tracks are usually associated with more recent artistic traditions (see bird tracks in arrangement with turtle and turtle eggs cluster – ). Emu tracks dominate the bird track motifs, while macropod tracks are over three times more frequently depicted with separated basal digital pads and toes. This is a characteristic of the early arid zone track and geometric repertoire – also known as the ‘Panaramitee’ (Edwards Citation1965; Maynard Citation1979; McDonald and Veth Citation2010).

Figure 12. Macropod (a–n) and bird (o–z) track motifs showing range in style and arrangement of track: single, paired and multiple configurations including macropods with tail imprint motif (b and d); note the greyed motifs occur on the same panels as the motifs shown.

Figure 13. Subject counts and proportions of Contrast State, comparing animal-like and track-like petroglyphs.

Figure 14. Chi-Square analysis of the proportion of contrast states in marine versus terrestrial species in this assemblage.

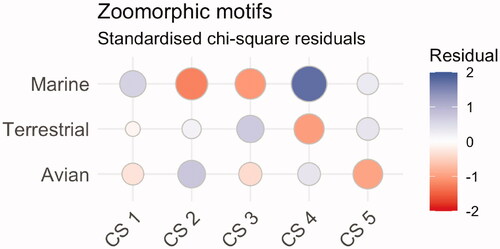

In general, there are relatively few of the freshest-looking petroglyphs across the Archipelago, which appears to indicate a reduction in petroglyph production in the recent past (McDonald et al. Citationin press). This assemblage is no different, with only 2% of the motifs having a non-weathered, fresh appearance. Here we consider the different contrast state as a five-part progression, from same colour as background = 1 and high contrast = 5. The zoomorphic assemblage reveals changing preferences through time in terrestrial and maritime subjects. Terrestrial animals (67%) dominate the zoomorphic assemblage, and almost 75% of these are in the older contrast states CS 1–3 (; ). Marine faunas represent a relatively small proportion of the assemblage (15%), and almost 60% of marine fauna motifs are in the earlier contrast states. In Murujuga assemblages where there is a clear Holocene marine signature, these motifs are predominantly found in CS 4–5. The Nganjarli assemblage appears to be an earlier rock art repertoire. A chi-square test confirms no significant difference in the contrast state proportions of terrestrial, marine and avian fauna (X2 (8 N = 200) = 9.5793, p = .2958). Terrestrial motifs greatly outnumber the marine and avian motifs in all contrast states (). CS suggests that bird tracks in this assemblage are predominantly older than the macropod tracks, but again a chi-square test shows no significant differences (X2 (8 N = 200) = 9.5793, p = .2958). The standardised residuals of the chi-squared for the three zoomorphic types show a slight increase in marine fauna in CS4, while terrestrial fauna slightly declines in CS4 ().

Grinding patches

Only two grinding patches were recorded amongst the Nganjarli rock art panels. The proportion of grinding patches here is very low for rock art assemblages across the archipelago (McDonald et al. Citationin press), and this could relate either to the underlying coarser gabbro geology, or to general site function (e.g. the inner gorge, located closer to water, had 35 grinding patches (McDonald Citation2009: 57) while the outer mound (DG001) had 11 grinding patches (McDonald Citation2009: 42). Residue and usewear studies conducted within the Rio Tinto leases on the southern Burrup reveal that the grinding patches result from the processing of both spinifex (Triodia spp.) seed and fibre and ‘bush-potato’ (Ipomoea costata, Fullagar Citation2011; Hayes et al. Citation2018).

Graffiti

Nineteen instances of graffiti, most of this recent (none was recorded in the DGEF area in 2009; McDonald Citation2009:43) were simple scratched geometric shapes (n = 12: 63.2%) but they also include human stick figures, two fish and the initials MB pecked or scratched into the gabbro blocks. Given that Nganjarli is the most popular cultural site visited on the Dampier Archipelago, this disrespectful and illegal behaviour highlights the need for urgent interpretative signage and tourist impact management, although recent acts of vandalism at Nganjarli indicate that signage in the absence of education is not enough to stop this type of behaviour.

Stone structures

Twenty-three stone structures of four different types or variants: manuport, standing stones, modified outcrops, and bedrock pits, were identified across Nganjarli (Beckett Citation2021:202; McDonald Citation2009). Four stone features (DGSC, DG_018, DG_022, and DG_038) identified in 2009 are standing stones: elongated stones wedged or chocked upright (McDonald Citation2009; see ). The other structure (DG_018) was a manuport placed on a ‘cube-shaped vertical boulder’ (McDonald Citation2009:76).

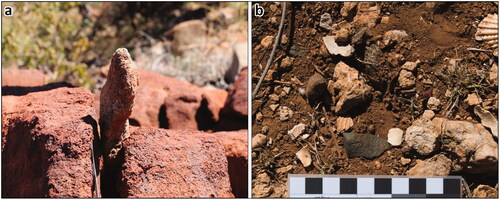

The 2019 survey identified eighteen stone structures: another two standing stones, a bedrock pit and fifteen stacked stone modifications (modified outcrops). Most of these structures are located high in the rocky slopes above Nganjarli gorge (). The two standing stones are small, protruding 11 cm and 34 cm above the ground surface (). As with the standing stones identified in 2009, these two standing stones are located around the break of slope high above the plain. They would not have been visible over long distances but are still likely to have functioned as signalling or communication devices (Beckett Citation2021:321). Such structures could have performed the function of marking location and drawing attention to a specific space in a different way and from various directions and distances than might be possible with rock art.

Figure 15. Nganjarli stone structures identified in 2019. Aerial imagery ©Nearmap 2021. Digital Elevation Model ©ESRI 2021. Inset shows location of section on 3D Model created from terrestrial imagery: the stacked stones are prominent in the location of the arrow.

Figure 16. (a) Standing Stone DG-2019-EF004; (b) Level area at DG-2019-EF014 showing calcrete in situ and dispersed with lithics and shellfish.

Bedrock pits occur where stones have been removed to create a central depression with the removed stones often stacked or scattered along the sides of the pit. One 2019 bedrock pit (DG-2019-EF010) measures 5 m × 1 m × 1 m deep and is in a sheltered area at the top of the slope (). Stones from its base, identified by a thin carbonate encrustation, are found around the edges of the pit. This structure’s function is not immediately apparent. The location and size of this bedrock pit makes it unlikely to have functioned to encourage game or as a hunting hide, a common explanation for similar structures (Gara Citation1984). It is conceivable that this structure was created to clear space, not for raw material acquisition, as there is no evidence of quarrying here (Beckett Citation2021:308). Calcium carbonate requires sufficient moisture to create mineral leeching (Beckett Citation2021:170) indicating that at one point there was moisture in the centre and base of the pit. At this stage however, it is unclear if this linked to the removal of the stones. There are cultural associations between stone circles and a particular practice of Law known to one of the authors (PJ), but this example, located on the high flat area of the massif, does not appear to be positioned for this practice. Bedrock pits are generally the most common form of stone structure identified across Murujuga and the relative scarcity of these structures from the current Nganjarli assemblage probably results from the narrow transect sampled by the 2009 and 2019 surveys, and limited geographic extent of these surveys on the steep gully walls and the front face of Nganjarli. These landscapes provide a good canvas for rock art, but they are not prime locations for bedrock pits.

Modified outcrops are the most common stone structure variant identified in the current study. These structures are found in level areas, both cleared and vegetated, amongst exposed rocky hills, with associated stacked and heaped structures (Beckett Citation2021:211). This type of Murujuga structure has not been explored in much detail, perhaps because their anthropogenic origins were called into question (ACHM Citation2006; but see Beckett Citation2021:137). Close examination of these features indicates clear evidence of anthropogenic modification, including flaked artefacts and shellfish, stacked rocks multiple tiers high, and differing weathered states of adjacent rocks that could not have been created by tree roots, mass movement, or other similar processes. The presence of extracted and stacked calcrete also cannot be explained by natural processes (). It is likely that these structures performed a practical function, providing level shaded spaces to sit or lie: a comfortable respite from the full sun on the hillslopes, as confirmed by Traditional Owners and reported by Lorblanchet (Citation2018). The presence of the edible tuber Ipomoea costata found in these exposures may also mean that the modifications could be related to food acquisition, or that this plant favours these modified outcrops (Beckett Citation2021:223; and see Buck Citation2018).

Open site, quarry and other cultural features

Around seven hectares at the front of Nganjarli contain surface archaeological material and potential archaeological deposit (McDonald Citation2009:30). As well as having surface shell midden (mostly Tegillarca sp.) this area also retains a large number of surface lithics. A fine-grained granophyre (rhyodacite) quarry source was recorded on the eastern side of the creek outflow from the Nganjarli gorge in 2009. Two culturally modified trees (CMT) with cut marks made with a metal axe (both are dead: one still standing, the other fallen) are in the creekline adjacent to the old vehicle parking area (). Radiocarbon analysis of a fragment from the fallen tree provided an age determination of the death of the tree c. 1900 AD (120 ± 10 Waikato-52276). Only one other CMT is known for Murujuga; this is a large ‘shield’ scar on the trunk of another dead tree, located towards the southern end of the Burrup Peninsula. The height and limb structure of trees across the archipelago does not usually require cut foot holds; certainly, these are the only examples of such cultural modification known to the authors.

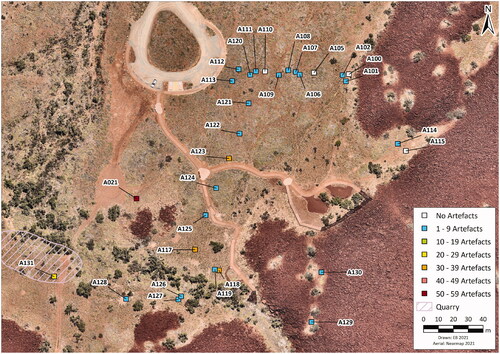

Transects and artefact density

Two transects were recorded across the site to sample the proposed visitor walking areas, the quarry, and other areas of potential visitor impact (). Sample squares (1 m × 1 m) were placed at 20 m intervals along these transects but were moved slightly where necessary to avoid dense spinifex.

Figure 17. Recorded sample squares and the density of artefacts in each square; the old and new car park, walkways and platforms evident in the base image.

Ground surface visibility varied greatly, affecting density estimates. Some areas were completely inaccessible due to spinifex, and artefacts were not visible on looser sandy surfaces. Density was inconsistent but mostly low (), with areas of higher and lower density close together. This suggests that relatively intact activity areas survive across this site. Artefact density was high in the open site near the creekline (38/m2). Mean density was 6.7/m2 (SD = 10.6). The high-density quarry sample (Square 131) had 23 artefacts recorded in a single quadrant (i.e. projected density of 92 artefacts/m2; see McDonald (Citation2009) for a more detailed record of this quarry’s characteristics). Artefacts were sometimes found in association with surface Tegillarca shell midden materials: this is most intact between the creekline and the new visitor walking track. The MAC Rangers, overseen by D. Guilfoyle (Applied Archaeology Australia and Murujuga Rangers Citation2016), recorded surface artefacts in the vicinity of the new parking area and the boardwalk and reported densities of up to 4.1/m2. Surface artefacts were moved from the recently installed carpark by the MAC Rangers. Exposed within the old parking area is a large grindstone which has been left in situ.

Assemblage details

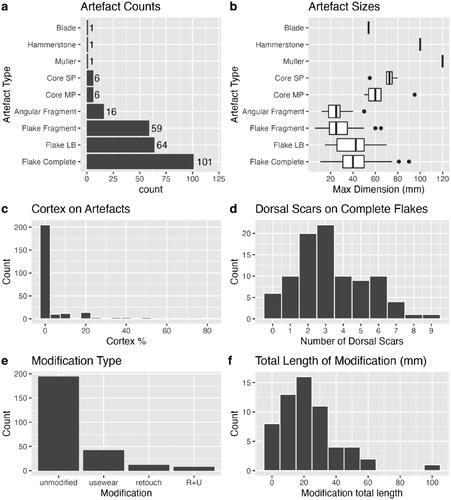

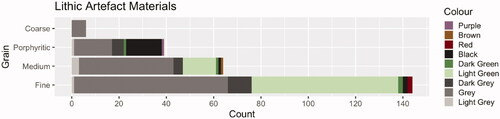

A total of 256 lithic artefacts were recorded from the 26 sample squares: four contained no artefacts (). Most of these are complete flakes, or longitudinally broken flakes (). The flakes have very little cortex, and most are unmodified ( and ). While the lack of cortex in the context of large amounts of fragmentary flakes may suggest intense reduction activity, the lithology of nearly half of the artefacts is not found on the Burrup Peninsula (see below). However, the Scar Density Index (SDI; for a detailed discussion of this method see Braun Citation2006; Clarkson Citation2002), which returned a mean of 1.07 (SD = 0.63), indicates that the lack of cortex on artefacts at Nganjarli is not the result of artefact reduction. The Nganjarli landscape is heavily heat-fractured and raw material outcrops often lack any cortex. Twenty artefacts were observed to have been retouched, albeit in a non-invasive and very minimal way (). This lack of retouch, in a landscape containing an abundance of readily available tool stone, is not surprising since ethnographic accounts have demonstrated that unretouched artefacts make up most of the functional lithic tool kits, and that people tend to prefer a new edge over one that has been retouched (Holdaway and Douglass Citation2012). Unlike previous Murujuga stone artefact studies (Morrison Citation2019; Veth Citation1982), there are relatively few cores identified (n = 12; ).

Figure 19. Nganjarli lithic artefact materials by grain quality and colour; excluding two quartz pieces and one multiplatform chert core.

Artefacts are grouped based on their colour and recorded grain-size (). Fine-grained material was most common (57%, n = 144), followed by medium-grained (26%, n = 64), porphyritic (15%, n = 39) and finally coarse-grained (2%, n = 6). Three artefacts were made on exotic materials: one red chert and two quartz pieces.

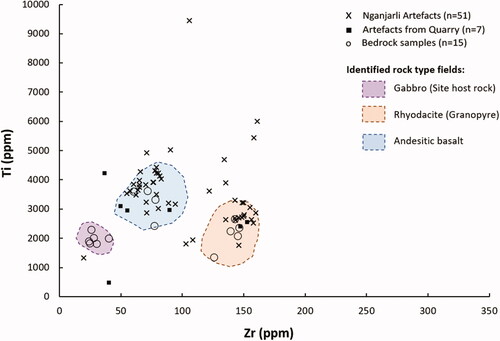

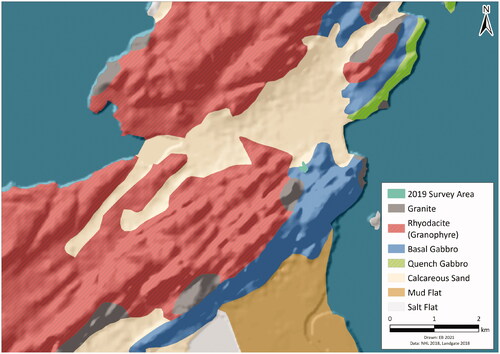

Portable XRF analysis

There are four exposed local rock types within 10 km of Nganjarli: basal gabbro (Nganjarli host rock), rhyodacite (previously referred to as granophyre Donaldson Citation2011; Fairweather Citation2019), granite, and quench gabbro (). The rock type which has been engraved extensively here is the basal gabbro, a unit that dips gently to the northwest.

Figure 20. pXRF scatter plots for the Nganjarli artefacts and bedrock samples; the rock type fields derive from more detailed analytical processes (Fairweather Citation2019).

The analysed artefact assemblage consists of basal gabbro and rhyodacite, as well as a third lithology, geochemically identified as andesitic basalt. The nearest known and mapped outcropping units of andesitic basalt are on East and West Lewis Islands, 12 km to the west of Nganjarli and now separated by Mermaid Sound. A sample (n = 58) of the total Nganjarli artefacts (n = 256) was analysed using the Niton pXRF to test the geochemical properties in a search for ‘elemental-fingerprints’ (). Additionally, 15 pXRF analyses were conducted directly on in situ local bedrock outcrops. This was done to create a local comparable geochemical dataset for the analysed artefacts.

Figure 21. Geological base map of Nganjarli surrounds (from Donaldson Citation2011). Three artefact source types occur within 300m (gabbro, rhyodacite and andesitic basalt), with two sediment-dominated lithologies.

The rock-type-zones shown (i.e. Rhyodacite, Gabbro and Andesitic Basalt) are based on outcrop sample analyses, including thin-sections, from Rosemary and Dolphin Islands (Fairweather Citation2019). The rock-type-zones represent areas on a plot where the analysed rock types have plotted previously, forming a comparable base map for the artefact analyses. Artefacts which fall within an identified rock-type-zone are interpreted as being composed of that rock type. To display the artefact rock-type-zones, the Zircon vs. Titanium (Zr vs. Ti) plot is favoured as more reliable than other comparative plots. This is because Zircon and Titanium are largely immobile elements, meaning they have a lower reactivity when in a crystal lattice, reducing the effect weathering and alteration has on the analyses.

When looking at the pXRF analysed artefacts, only a small proportion (n = 9; 11.8%) of the assemblage derives from the local Nganjarli basal gabbro. Just under half (n = 33; 43.4%) of the analysed artefacts are identified as andesitic basalt; this includes several artefacts (n = 7) recorded in the quarry sample. Rhyodacite is the next-most common proportion of the assemblage (n = 24; 33.3%). This is a major rock type of the inner regions of the archipelago, with the closest significant outcrop only 500 m to the west of the Nganjarli site (). Only a small proportion of the Nganjarli artefacts analysed (n = 9; 11.8%) show no correlation with any previously analysed outcropping rock types. In situ andesitic basalt has only been mapped on the middle to outer islands of the archipelago and not on the Burrup, although only Rosemary Island has been extensively geochemically studied and mapped at this stage (Fairweather Citation2019). There are also a number of unmapped andesite-basalt and dolerite dykes around the Archipelago (e.g. at Watering Cove), which are yet to be investigated and geochemically analysed. This range of source material is in line with the findings made by Veth (Citation1982) that major occupation locales on Murujuga consist of a mixture of raw material types, compared to task specific sites where mono-lithic assemblages are recorded.

Economic shellfish

There is an extensive and variable density surface scatter of marine shell, mostly Tegillarca cf. zanzibarensis (cf. Anadara granosa Taylor and Glover Citation2004), across the plain outside the main gorge, as well as a high concentration at locations in the interior gorge. Two 1 m × 1 m samples of Tegillarca sp. surface midden were counted and measured: square A118 (north of the creek), and WPT007 (inside the DGSC site complex). Both squares show a size selection preference towards c.31–35 mm, with very few juveniles (; ). The preferential selection of small adult Tegillarca cf. zanzibarensis may relate to when they are most suitable as food, or possibly reflects the seasonality of collection. A very similar size range was recorded at the Old Geo’s site, located three kilometres south of Nganjarli, where an extensive Tegillarca sp. midden was dated to c.1,500 calibrated years ago (McDonald et al. Citationin press).

Figure 22. Nganjarli Tegillarca cf. zanzibarensis MNI showing mean length of the two sample squares.

Table 3. Tegillarca cf. zanzibarensis valve sizes.

Education, management and significance

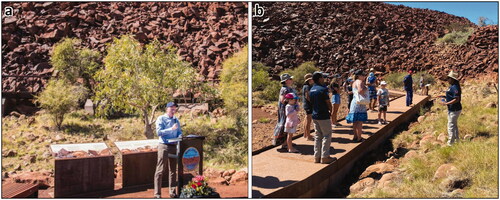

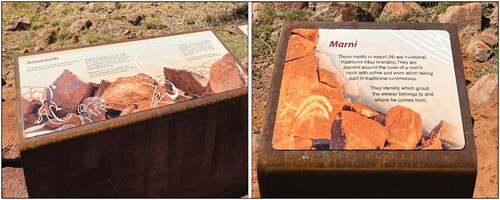

MAC considers that public education and interpretation is vital to achieve their goal of Coming Together for Country (Ngayintharri Gumuwarni Ngurrangga). The decision to direct tourists to the Nganjarli site, with the boardwalk located on the outer slopes, was made by MAC after consultation with the MAC Circle of Elders. The rationale for this was to divert tourists from culturally sensitive imagery in the interior gorge, as well as to address concerns from the Elders that crossing the interior creek would be too difficult for less agile people. The car park location is changed from the original parking area which had developed haphazardly over the last 40 years, with its final placement purposefully avoiding an intact grindstone embedded in the surface of the old vehicle park-up area. All walkways here are wheelchair accessible and the materials used allow for all types of pedestrian capabilities. This tourism infrastructure in the southern portion of Murujuga National Park, with carpark and other interpretive facilities, is now complete. The Boardwalk was officially opened in August 2020 (). The interpretative signage covers various natural and cultural themes, developed in consultation with the Circle of Elders (). Assistance with the graphics was provided by this recording exercise and text for several panels was provided by two of the authors (PJ and KM).

Figure 23. The official opening of Nganjarli Boardwalk with the W.A. State Minister for Environment, Hon Stephen Dawson MLC (a); and Murujuga Ranger Sarah Hicks leading an interpretive tour at Nganjarli (b) (photos permission of MAC).

Figure 24. Two of the interpretive signs that focus on animals and local art traits, installed as part of the new Nganjarli tourist development.

The Nganjarli area is now the focus for Welcome to Country ceremonies, where visitors are welcomed by MAC Rangers. Such welcomes include singing-out in Ngarluma language to alert the ancestors of the place to new visitors, and to ensure that visitors will be safe on-country. The rock art tour that follows includes cultural and scientific information about the place and provides additional context regarding the management of Murujuga and the importance of staying within approved visitor areas. This responsibility to look after country and to ensure the cultural safety of visitors is paramount to the MAC tourism strategy.

MAC aspires to increase the current interpretive facilities with educational and tourism options that incorporate augmented reality, virtual reality, and smart phone applications to promote scientific and cultural education about sites and rock art and increase the range of self-directed tours and enhance visitor experiences of places like Nganjarli with technologically enabled interpretative information. To this end, one of the visualisations that we have prepared from this fieldwork is a drone and 3D imagery movie that emulates a fly-over across the slopes and past several of the 3D panels that are part of the digital interpretation (see McDonald et al. Citation2020).

After fieldwork, all images and data collected were audited by MAC. All rock art images were also subject to the MAC-CRAR + M Image Clearance Process. The Traditional Owners have designed this process to designate cultural significance of the imagery. A senior male custodian (in this case, Peter Jeffries) worked with the CRAR + M Database Manager to audit all imagery. This process ensures cultural safety of image repatriation to MAC at the end of all major recording projects. Rock art imagery is designated as ‘Open’ or ‘Closed’ with various levels of cultural significance within the closed categories. All data were then uploaded into the CRAR + M Database, a web archive that is accessible to MAC (and collaborating communities on other estates), industry partners and researchers at CRAR + M UWA, with restrictions applied to ‘Closed’ images.

The Nganjarli survey was focussed on the area of the broader cultural site complex where the public will be directed by MAC’s Cultural Tourism Strategy. Both the State’s Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972 (as amended) and the Federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, protect the Murujuga rock art. But accurate site records are required to enable the protection and interpretation of the abundant rock art of Murujuga. Concern over this issue prompted MAC and the Elders to request this current investigation. While our survey was not part of the mitigation activities undertaken for the s18 consent to impact permit received under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972, accurate geospatial data and all cleared imagery (photographs and sketches) were provided to the Parks and Wildlife Service of the DBCA to assist in the avoidance of heritage items during construction and to contribute to the interpretive signage for the area.

The placement of interpretive signage will encourage education of tourists and assist in the management of tourists wanting to mark the rocks, actions which are understood to be partly undertaken out of frustration at not being able to view or understand the art (Gale and Jacobs Citation1987). One outcome of this project is the identification of additional petroglyph panels visible from the footpath and raised boardwalk that are suitable for further visitor interpretation. They are distributed around the lower slopes and comprise imagery which has been culturally classified as ‘open’ (). We discuss these here from west to east in the order that visitors would encounter these compositions as they progress around the boardwalk from the carpark:

Figure 25. The Nganjarli site showing the location of the selected petroglyphs suitable for public education and awareness in the vicinity of the proposed walkway.

Composition of macropod and macropod tracks – located near the base of the slope facing northward. On adjacent panels, there are figurative and track representations of the kangaroo. This dual mode of depicting animals, birds and humans is a specific feature of Murujuga rock art and worthy of interpretation. There is also a known cultural association between a particular footprint and the interior gorge at Nganjarli;

Butchered macropod – the depiction of segmented fauna is also a feature of Murujuga rock art; in this case there is an intact head and torso with severed tail beside and the legs together at the top of the panel (). This panel faces eastward near the top of the rise of the western promontory;

Tasmanian Devil petroglyph faces north-west and is on the southern side of a gully formation within the rock slope. This four-legged animal with barrel body, thick short tail and relatively large head () was widespread across Australia until about 3,000 years ago;

Stingray – not common in the Murujuga rock art repertoire, and this example has the pelvic fins depicted and a pattern over the pectoral fins (). The panel faces north-west, part-way up the slope and is easy to see. Having a relatively high contrast state, it was probably produced after sea-level stabilisation (last 7,000 years);

Emu – depicted in an earlier era when the artists chose sizeable rock faces to produce large, outline images of fauna and humans. Located on a large north-west facing block, this emu is a thalu site (Daniel Citation1990), and has been repeatedly reworked by pounding and abrasion of the original pecked outline ();

Fat-tail macropod – on a block fallen from its original position, now at the base of the slope facing eastward (). This characteristic form may depict a now extinct fat-tailed species of kangaroo or may simply be an artistic embellishment;

Goanna (monitor lizards) – a valued food that appears often in Murujuga rock art. When goannas are captured, hunters will dislocate the limbs to prevent the animal escaping/harming the hunter. The leg position on this example may be depicting this practice (). This panel faces west north-west halfway up the slope;

Thylacine – once common throughout Australia, is no longer in this part of the country; the most recent known example is at Caladenia Cave near Perth (Thorn et al. Citation2017). The introduction of the Dingo is implicated in the demise of the Thylacine. There are six Thylacine depictions in the vicinity of the boardwalk (), and four more within the Nganjarli gorge complex.

Nganjarli is in Murujuga National Park and the National Heritage Place. The National Heritage listing has identified significance criteria that were met by Murujuga’s rock art and stone features (McDonald and Veth Citation2009). Identifiers have been formulated for use when assessing significant impacts (e.g. http://www.environment.gov.au/epbc/about/pubs/ca-hamersley.pdf) and these are also useful for demonstrating whether a particular assemblage meets the National Heritage Listing criteria. The Nganjarli boardwalk assemblage possesses identifiers which meet all criteria defined by the National Heritage List (). Motifs and features identified as fulfilling these National Heritage Listing criteria are distributed across all parts of the Nganjarli site complex. For cultural reasons, this paper has not focussed on anthropomorphic depictions, but the variability defined in the National Heritage List identifiers 1–5 () are clear in the 195 anthropomorphic types recorded (). The presence of stone arrangements and standing stones is another aspect of this assemblage’s National Heritage values.

Table 4. Nganjarli National Heritage values and NHL criteria.

Conclusions

The recently constructed Nganjarli site infrastructure provides the primary rock art tourism destination in Murujuga National Park. Visitor facilities include the recently installed boardwalk, footpaths and interpretive signage that has provided much-needed information and access for the growing numbers of visitors arriving in the region, generally in the cooler months between April and September. MAC and DBCA have a long-term goal for a recreation precinct in the northern Burrup. The Murujuga Living Knowledge Centre, recreational day-use areas, accommodation, amenities, and road access to the northern Burrup are currently being planned, and these will provide a range of interpretive opportunities and education facilities in addition to those at Nganjarli. As well as using the current signage and interpretation, there will be opportunities to deploy the imagery recorded here in virtual tours and to provide substantial content to any digital interpretation in the Murujuga Living Knowledge Centre.

This paper highlights the scientific significance of the archaeological evidence documented at Nganjarli ahead of the installation of viewing platforms, walking trails and other amenities. Our recording has demonstrated that the petroglyph assemblage and stone features on this outer slope meet all National Heritage List significance criteria. This analysis confirms the extraordinary variability in animal imagery near the new boardwalk, and detailed digital recordings have resulted in this imagery being translated into interpretive signage. MAC’s cultural clearance processes of the imagery before production of the interpretive signage ensured that culturally sensitive imagery has not been highlighted for the tourist’s gaze. Future digital approaches (including virtual reality and walking-tour apps) will provide an opportunity to increase the interpretation options for the rock art on this slope, as well as furthering the protection of sensitive imagery by exclusion.

This paper has identified additional interpretative themes as opportunities for further explanation of this significant landscape. The open occupation sites and quarries in the vicinity of this interpretative facility are extensive and present a significant untapped research opportunity to understand the age of the occupation, the movement of lithic resources around this tool-stone rich landscape, the targeted acquisition of shellfish and the social context of the art production.

The importance of a coherent research and management approach in the consideration of tourism infrastructure placement should not be underestimated. The archaeological and cultural evidence at Nganjarli highlights how interpretative facilities can be developed to engage visitors in the contemporary cultural values of the place, the rich scientific value of the archaeology, showcase the unparalleled creative genius of the petroglyphs and acknowledge a deep time sequence of occupation across the broader landscape. Acknowledgment of the complexities of this cultural landscape will continue to be critical in managing tourism impacts without compromising cultural values and sensitivities. The interpretative themes that link Nganjarli to the broader heritage estate of the archipelago contribute significantly to our understanding of Murujuga’s cultural landscape. The national heritage values identified, and the ongoing collaborative co-management of this place are vital components of the current dossier being prepared to document the Outstanding Universal Value for World Heritage Listing.

Acknowledgments

The fieldwork which resulted in this paper was funded by the UWA—Rio Tinto MoU through the Rio Tinto Conservation Agreement with the Commonwealth. The fieldwork involved UWA staff and students as well as Rio Tinto Heritage staff. The recording work was facilitated by Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation’s Peter Jeffries and included the participation of Patrick Churnside, Mariah Reed and Sarah Hicks. Rock art was recorded by Victoria Anderson, Sarah de Koning, Jess Green, ben Gunn, Emily McBride, Jo McDonald, Ana Paula Motta, Ken Mulvaney and Alex Walter. Stone features were recorded by Emma Beckett; stone artefacts were recorded by Zane Blunt, Patrick Morrison and the PXRF analysis was done by John Fairweather; shells were recorded by Joe Dortch, who also undertook the DGPS plotting of all recorded features. Thanks also to Amy Stevens for commenting on the draft version of this paper. All rock art imagery included in this paper has been cleared for publication by Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andrefsky, W. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Applied Archaeology Australia (AAA) and Murujuga Rangers 2016 Report of a Cultural Heritage Survey for the Proposed Boardwalk, Deep Gorge, Murujuga National Park. Western Australia. Unpublished report prepared for the MAC and DBCA.

- Australian Cultural Heritage Management (ACHM) 2006 An Archaeological Survey for the Proposed Woodside Pluto LNG Development, Industrial Site B. Burrup Peninsula, WA: Woodside Energy Limited, WA.

- Beckett, E. 2021 Contextualising Murujuga Stone Structures: Dampier Archipelago. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Centre for Rock Art Research + Management, The University of Western Australia, Perth.

- Braun, D.R. 2006 The Ecology of Oldowan Technology: Perspectives from Koobi Fora and Kanjera South. Unpublished PhD Thesis, The State University of New Jersey, New Jersey.

- Brown, S 1983 Incised rock engravings and fat-tailed macropod motifs, Pilbara, WA. In M. Smith (ed.), Archaeology at ANZAAS 1983, pp.143–194. Perth: Western Australian Museum.

- Brown, S 2018 Tales of a fat-tailed macropod. In M.L. Langley, M. Lister, D. Wright, and S.K. May (eds), Archaeology of Portable Art: Southeast Asian, Pacific, and Australian Perspectives, pp.241–257. New York: Routledge.

- Buck, G. 2018 Distribution and Ecological Conditions of Ipomoea costata Benth., associated with Stone Features at Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula), Northwest Australia. Unpublished Bachelor of Science (Honours) Thesis, Botany Department, The University of Western Australia, Perth.

- Clarkson, C 2002 An index of invasiveness for the measurement of unifacial and bifacial retouch: A theoretical, experimental and archaeological verification. Journal of Archaeological Science 29(1):65–75.

- Clarkson, C. and S. O'Connor 2006 An introduction to stone artefact analysis. In J. Balme and A. Paterson (eds), Archaeology in Practice: A Student Guide to Archaeological Analyses, pp.159–199. New York: Blackwell.

- Clegg, J 1978 Pictures of striped animals: Which ones are Thylacines? Archaeology and Physical Anthropology in Oceania 13(1):19–29.

- Daniel, D. 1990 Thalu Sites of West Pilbara: A Description of Some of the Tribal Increase Sites of the West Pilbara. Perth: Department of Aboriginal Sites, Western Australian Museum.

- de Koning, S. 2014 Thatharruga: A Stylistic Analysis of Turtle Engravings on the Dampier Archipelago. Unpublished BA (Hons) Thesis, Centre for Rock Art Research + Management, The University of Western Australia, Perth.

- Department of Aboriginal Sites (DAS) 1984 Dampier Archaeological Project: Survey and Salvage of Aboriginal Sites on a Portion of the Burrup Peninsula. Report for Woodside Offshore Petroleum Pty Ltd. Perth: Department of Aboriginal Sites, Western Australian Museum.

- Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) 2006 Proposed Burrup Peninsula Conservation Reserve Draft Management Plan 2006-2016. Perth: Department of Environment and Conservation.

- Donaldson, M 2011 Understanding the rocks: Rock art and the geology of Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula) [with comments]. Rock Art Research 28(1):35–43.

- Edwards, R 1965 Rock engravings and aboriginal occupation at Nackara Springs in the north-east of South Australia. Records of the South Australian Museum 15:9–29.

- Fairweather, J.H. 2019 Geological and Geochemical Characterisation of the Archean Fortescue Group, Rosemary Island, and Associated Archaeological Material from the Dampier Archipelago, Western Australia. Unpublished BSc (Honours) Thesis, Geology Department, The University of Western Australia, Perth.

- Flanagan, F 2007 The Burrup Agreement: A case study in future act negotiation funds. pp.1–21. <www.atns.net.au/atns/references/attachments/Flanagan%20Paper.pdf>

- Fullagar, R. 2011 Happy Valley Grinding Patches. Dampier: Unpublished report prepared for Rio Tinto Iron Ore.

- Gale, F., and N. Jacobs 1987 Aboriginal art: Australia's neglected inheritance. World Archaeology 19(2):226–235.

- Gara, T. 1984 Stone Features of the Burrup Peninsula. Perth: Unpublished Document, Western Australian Museum.

- Harper, S. 2010 A Conversation Palimpsest: Clustering and Extreme Heterogeneity in the Rock Art of Deep Gorge on the Burrup Peninsula. Dampier Archipelago. WA. Unpublished BA (Hons) Thesis, Australian National University, Canberra.

- Harris, J. 1988 An Excavation Report of Georges Valley Shell Midden, Burrup Peninsula. Unpublished BA (Hons) Thesis, University of Western Australia, Perth.

- Hayes, E.H., R. Fullagar, K. Mulvaney and K. Connell 2018 Food or fibercraft? Grinding stones and Triodia grass (Spinifex). Quaternary International 468:271–283.

- Hiscock, P 2002 Quantifying the size of artefact assemblages. Journal of Archaeological Science 29(3):251–258.

- Holdaway, S., and M. Douglass 2012 A twenty-first century archaeology of stone artifacts. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 19(1):101–131.

- Kassambara, A. 2019 ggcorrplot: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix using 'ggplot2'. R package version 0.1.3.

- Kuhn, S.L 1994 A formal approach to the design and assembly of mobile toolkits. American Antiquity 59(3):426–442.

- Lorblanchet, M 2018 Archaeology and petroglyphs of Dampier (Western Australia): An archaeological investigation of Skew Valley and Gum Tree Valley. Technical Reports of the Australian Museum 27. ISSN 1835-4211 (online).

- McDonald, J. 2009 Archaeological Survey of Deep Gorge on the Burrup Peninsula (Murujuga) Dampier Archipelago WA. Perth: Unpublished Jo McDonald Cultural Heritage Management Pty Ltd report prepared for the Department of Indigenous Affairs.

- McDonald, J. 2015 I must go down to the seas again: Or, what happens when the sea comes to you? Murujuga rock art as an environmental indicator for Australia's north-west. Quaternary International 385:124–135.

- McDonald, J. 2021 Wintawari Guruma Rock Art Project: Field Trip 2. Unpublished CRAR + M UWA report prepared for Wintawari Guruma and RioTinto.

- McDonald, J., and P. Veth 2006 A Study of the Distribution of Rock Art and Stone Structures on the Dampier Archipelago. Jo McDonald Cultural Heritage Management Pty Ltd. Canberra: Unpublished report prepared for Heritage Division, Department of Environment and Heritage.

- McDonald, J., and P. Veth 2009 Dampier Archipelago petroglyphs: Archaeology, scientific values and national heritage listing. Archaeology in Oceania 44(S1):49–69.

- McDonald, J., and P. Veth 2010 Pleistocene rock art. A colonising repertoire for Australia's earliest inhabitants. Préhistoire, Art et Sociétés: Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique de L'Ariège 65:172–173.

- McDonald, J., and P. Veth 2013 Rock art in arid landscapes: Pilbara and Western Desert petroglyphs. Australian Archaeology 77(1):66–81.

- McDonald, J., E. Beckett, J. Hacker, P. Morrison and M. O’Leary 2020 Seeing the Landscape: Multiple scales of visualising terrestrial heritage on Rosemary Island (Dampier Archipelago). Open Quaternary 6(1):10. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.5334/oq.81

- McDonald, J., K. Mulvaney, A. Paterson and P. Veth (eds) in press. Murujuga: Dynamics of the Dreaming. The Results of Excavations and Systematic Rock Art and Stone Feature Recording. CRAR + M Monograph No 2. Due out in Q4. Perth: UWA Press.

- Maynard, L 1979 The archaeology of Australian Aboriginal art. In S.M. Mead (ed.) Exploring the Visual Art of Oceania. pp.83–110. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii.

- Morrison, P. 2019 The Geoarchaeology of a Submerged Aboriginal Site in the Intertidal Zone of Dolphin Island, Murujuga. Unpublished BA (Hons) Thesis, CRAR + M and Archaeology, University of Western Australia, Perth.

- Mulvaney, K.J. 2009 Dating the dreaming: Extinct fauna in the petroglyphs of the Pilbara region, Western Australia. Archaeology in Oceania 44(S1):40–48.

- Mulvaney, K. 2010 Murujuga Marni: Echoes Across Time, Shadows in the Landscape. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of New England, Armidale.

- Mulvaney, K. 2013 Iconic Imagery: Pleistocene rock art development across northern Australia. Quaternary International 285:99–110.

- Mulvaney, K. 2015 Murujuga Marni – Rock Art of the Macropod Hunters and the Mollusc Harvesters. CRRA + M Monograph Number 1. Perth: UWA Press.

- Nearmap 2021 Western Australia Latest. Web Map Server. Accessed from https://api.nearmap.com/wms/v1/latest/**API KEY**

- Paterson, A., J. Dortch, R. Anderson, K. Mulvaney, S. de Koning and J. McDonald 2019a So ends this day: Records in stone of American whalers in Yaburara country, Dampier Archipelago, Northwest Australia. Antiquity 93(367):218–235.

- Paterson, A., T. Shellam, P. Veth, K. Mulvaney, R. Anderson, J. Dortch and J. McDonald 2019b The Mermaid? Re-envisaging the 1818 exploration of Enderby Island, Murujuga, Western Australia. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 15(2):284–221.

- R Core Team 2020 R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Stewart, R. 2016 An Approach with Style: A Stylistic Analysis of Macropod Rock Art on Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula), Western Australia. Unpublished BA (Hons) Thesis, Centre for Rock Art Research + Management, University of Western Australia, Perth.

- Taylor, J., and E. Glover 2004 Diversity and distribution of subtidal benthic molluscs from the Dampier Archipelago, Western Australia: Results of the 1999 dredge survey (DA2/99). Records of the Western Australian Museum, Supplement 66(1):247–291.

- Thorn, K. M., R. Roe, A. Baynes, R. P. Hart, K. A. Lance, D. Merrilees, J. K. Poorter and S. Sofoulis 2017 Fossil mammals of Caladenia Cave, northern Swan Coastal Plain, south-western Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum 32(2):217–236.

- Veth, P. 1982 Testing the Behavioural Model – the Use of Open Site Data. Unpublished BA (Hons) Thesis, Archaeology Department, The University of Western Australia.

- Veth, P., I. Ward, T. Manne, S. Ulm, K. Ditchfield, J. Dortch, F. Hook, F. Petchey, A. Hogg, D. Questiaux, M. Demuro, L. Arnold, N. Spooner, V. Levchenko, J. Skippington, C. Byrne, M. Basgall, D. Zeanah, D. Belton, P. Helmholz, S. Bajkan, R. Bailey, C. Placzek and P. Kendrick 2017 Early human occupation of a maritime desert, Barrow Island, North-West Australia. Quaternary Science Reviews 168:19–29.

- Vinnicombe, P. 2002 Petroglyphs of the Dampier Archipelago: Background to development and descriptive analysis. Rock Art Research 19(1):3–27.

- Wickham, H., M. Averick, J. Bryan, W. Chang, L. McGowan, R. François, G. Grolemund, A. Hayes, L. Henry, J. Hester, M. Kuhn, T. Pedersen, E. Miller, S. Bache, K. Müller, J. Ooms, D. Robinson, D. Seidel, V. Spinu, K. Takahashi, D. Vaughan, C. Wilke, K. Woo and H. Yutani 2019 Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 4(43):1686.