Space archaeology emerged as a subdiscipline around the year 2000, with a very Australian complexion. Professor John Campbell was a pioneer in this area, taking a broad cosmic view incorporating archaeoastronomy and SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence; Campbell Citation2005). Dirk Spennemann (Citation2004) considered the ethics of treading on Neil Armstrong’s footprints, and with Guy Murphy, studied the taphonomy of Martian crash sites (Spennemann and Murphy Citation2009). My starting point was space junk in Earth orbit, and the intersection of Indigenous heritage and space technology at places like the Woomera Rocket Range in South Australia.

A watershed moment in the development of space archaeology was the 2003 World Archaeological Congress in Washington DC. There, John Campbell and Beth Laura O’Leary convened the first ever conference session on space archaeology. There were only the three of us presenting in it. Initially, there was scepticism. The archaeology of the contemporary past was starting to gain momentum, and not everyone was happy about it. For a while there was even a group called ‘Sensible Archaeology’, intent upon stemming the crazy ideas of us renegades. I think some feared that space archaeology would open the gates to even more ‘ancient alien’ stuff than we already had to deal with. I was careful to avoid xenoarchaeology and SETI in the early years of my research, conscious of the potential for misunderstanding.

My approach to space archaeology at that time was very much informed by Australian perspectives, which I see as a strength. My career to that point had been in heritage management, with a focus on lithics. When I first started thinking about space archaeology, it seemed obvious to treat space sites—such as rocket ranges—as cultural landscapes, and to ask where the Traditional Owners were while the Space Age was taking off. My early research looked at places like Woomera and the launch site of Kourou in French Guiana, and their cultural significance as intersections between the ‘Space Age’ and the ‘Stone Age’ in a colonial context (Gorman Citation2007). Indigenous colleagues like Andrew Starkey (Kokatha) were influential in shaping my approach. Later, I applied the cultural landscape lens to planetary bodies, such as the Moon and Comet 67 P, and argued that the entire solar system was now a cultural landscape (Gorman Citation2005a). The 2022 Australia ICOMOS practice note on cultural landscapes recognises that cultural landscapes now extend into space.

Another early question focus was whether the Burra Charter worked outside Earth. Intuitively, the answer to this was yes; nevertheless I assayed significance assessments of orbiting space junk to test this assumption. This included the US satellite Vanguard 1, launched in 1958 and the oldest human object in space (Gorman Citation2005b). Using the Burra Charter enabled the articulation of the satellite’s social significance as a Cold War ideological weapon, rather than focusing solely on its technological aspects. Closer to home, the student-built satellite Australis Oscar 5, launched in 1970, is Australia’s oldest contribution to material culture outside Earth. While a footnote in the broader history of satellites, AO5 is tremendously significant as an early Australian space endeavour and as an example of the development of amateur and low-budget technologies, which counter the dominant narratives of more powerful spacefaring nations. As the problem of space junk accelerates and the technologies for active debris removal are developed, I have continued to argue that this must take place in an environmental management framework which takes account of heritage values such as these (Gorman Citation2019, Citation2021).

Insights from working in Indigenous contexts where the division between ‘natural’ and ‘cultural’ heritage is counterproductive have also been relevant for considering the management of planetary environments, such as the Permanently Shadowed Regions of the Moon which are the current target of mining aspirations. In my 2023 report for the Global Expert Group on Sustainable Lunar Activity (Gorman Citation2023), I extended this to the ‘natural’ environment of the Moon, noting that cultural significance is increasingly being evaluated as part of environmental values. The space community struggles to see abiotic environments as having value, but as plans for lunar mining gain pace, it is critical to define what these values are in order to mitigate harm.

One issue in space archaeology has been the inaccessibility of places off-Earth, and hence the lack of what is usually considered to be archaeological data. For the last several years, I have been working with Associate Professor Justin Walsh, to study the International Space Station as an archaeological site (Walsh and Gorman Citation2021). In 2022 we conducted the first archaeological ‘fieldwork’ outside Earth when the crew of the ISS, following our instructions, carried out a photographic survey of six one-by-one metre squares located in various modules. A feature of our investigation is analysing the spatial distribution of materials such as Velcro as ‘gravity surrogates’ which enable the crew to replicate the effects of gravity in this unique setting. Our aim in this project is to demonstrate to NASA that archaeology can provide novel insights into adaptations to different gravity environments. In that we have been successful, attracting interest in our work from space habitat manufacturers at the international level.

The objects and places of twentieth and twenty-first century space technology are fascinating in their own right, but space archaeology has broader relevance for terrestrial archaeology because it forces us to question what we know. Varying constants like gravity and atmosphere, invisible backdrops to all life on Earth, offer new insights into what it means to be human. When you strip these constants out, which aspects of human behaviour turn out to be determined by environment and which by culture?

Space archaeologists have accomplished much in the 20 years or so since the field emerged, to the point where it is seen as a valuable and credible part of the discipline, but there is still so much to be done. What I see as the big space archaeology questions for the future include:

A systematic appraisal of Australia’s terrestrial and extraterrestrial contributions to the archaeological record of space.

The emergence of distinct national and corporate space cultures, including those of ‘non-spacefaring’ nations.

Impacts of space technology on the material culture of daily life on Earth.

Managing the natural and cultural heritage of the solar system.

Investigating Earth and near-Earth space as a combined ‘natural’ and ‘cultural’ system.

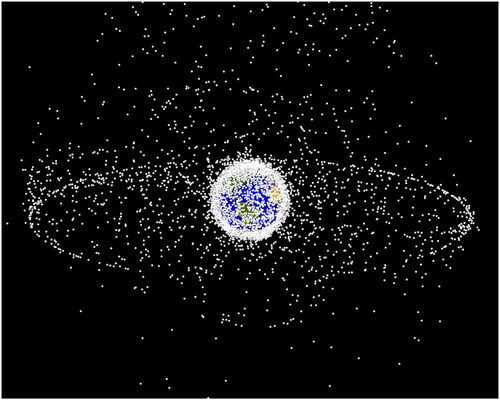

Space places and technology are edging towards being a century old. The daily life of people on Earth’s surface is increasingly structured by satellite-based telecommunications, navigation, timing, weather prediction and disaster management, as well as a significant component of defence capability. It is no longer possible to ignore the impacts of off-Earth material culture in shaping the contemporary archaeological record on Earth. Indeed a case could be made to redefine the boundary of Earth at 35,000 km above the surface, where the geostationary orbit of telecommunication satellites has become an engineered planetary ring comparable to the natural ring systems of the outer solar system (). Existing as it does on the cusp of the present and the future, space archaeology is both an exciting and necessary area of practice as the sphere of human impacts expands beyond Earth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Campbell, J.B. 2005 Archaeology and direct imaging of exoplanets. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 1(C200):247–250.

- Gorman, A.C. 2005a The cultural landscape of interplanetary space. Journal of Social Archaeology 5(1):85–107.

- Gorman A.C 2005b. The archaeology of orbital space. In 5th NSSA Australian Space Science Conference, p. 338–357. Melbourne: RMIT University.

- Gorman, A.C. 2007 La terre et l‘espace: Rockets, prisons, protests and heritage in Australia and French Guiana. Archaeologies 3(2):153–168.

- Gorman A.C 2019 Dr Space Junk vs the Universe: Archaeology and the Future. Sydney: New South Publishing.

- Gorman A.C 2021 Space debris, space situational awareness and cultural heritage management in Earth orbit. In M. de Zwart and S. Henderson (eds), Commercial and Military Uses of Outer Space, pp. 133–151. Singapore: Springer

- Gorman A.C 2023 The Sustainable Management of Lunar Natural and Cultural Heritage: Suggested Principles and Guidelines. Report to the Global Expert Group on Sustainable Lunar Activity. Retrieved 20 June 2023 from <https://moonvillageassociation.org/gegsla/documents/gegsla-reference-documents/>.

- Spennemann, D.H.R. 2004 The ethics of treading on Neil Armstrong’s footsteps. Space Policy 20(4):279–290.

- Spennemann D.H.R. and G. Murphy 2009 Failed Mars mission landing sites: Heritage places or forensic investigation scenes? In A. Darrin and B. O’Leary (eds), Handbook of Space Engineering, Archaeology and Heritage, pp. 457–479. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Walsh, J. St. P. and A.C. Gorman 2021 A method for space archaeology research: The International Space Station Archaeological Project. Antiquity 95(383):1331–1343.