Abstract

This paper explores the archaeology of one of the more recently excavated ‘convict hut’ sites, the structures associated with early convict occupation (c.1788–1818) of the colonised agricultural landscape of what is now Parramatta in New South Wales. The paper primarily examines what substantive conclusions can be drawn from what could be considered repetitious archaeological sites: one hut in a long line of huts. The work focuses on the temporal and spatial constraints of evidence from the Club Parramatta site, building on the legacy of excavations that have occurred over the last 40 years. The results are framed through a conceptual lens of assemblages of practice and make use of comparative artefact analysis of three huts. We argue that New Materialism is particularly helpful for avoiding dualistic interpretations, such as convict/free, and instead allows for more nuanced and active understandings of people in the past.

Introduction

The trowels are down on another of Parramatta’s ‘convict hut’ sites. This excavation, completed in 2020, uncovered evidence of the structures associated with early convict lives in Parramatta, New South Wales, and encompassed the locations of six huts, as shown on the c.1804 Plan of the Township of Parramatta (The National Archives UK, Citation1804, Map CO.700.22). Evidence for three huts was found during the 2020 excavation, along with potential evidence for a fourth, and additional yard structures and features. The convict huts, as they are known, were built along major streets in Parramatta in the early 1790s. Through the conceptual lens of assemblages of practice (see below), we explore the temporal and spatial constraints of evidence from the Club Parramatta site excavation (GML Heritage Citation2023). This theoretical framing brings together archaeologists in the present and the occupants, events and things of the past into an exploration of action (practice) within a place (Antczak and Beaudry Citation2019).

Despite being a highly visible component of the settler colonial landscape, the huts are poorly documented, both in the broad sense of their changing use over time and more specifically in relation to the occupants themselves. Shanahan and Gibbs (Citation2022) recently outlined the historical context of the huts in Parramatta, noting that the structures were initially barracks for convict gangs who were providing labour to the colonial settlement. From around 1800, the structures began to transition to private, ‘free’ dwellings. There is longstanding debate about the archaeological visibility of this convict/free divide in the archaeological record from sites with huts (Casey Citation2009; Higginbotham Citation1992; Parker Citation2006).

A complicating factor is what is meant by the terms ‘convict’ and ‘free’. ‘Convict’ generally describes a person who was actively serving a penal sentence, although the label sometimes stayed with a person even after emancipation. ‘Free’ could mean an emancipated person, or someone who was ‘born free’ or ‘came free’ to the colony. In this early period at the key colonial settlements of Sydney, Norfolk Island and Parramatta, there was no clear association between living conditions and convict status—convicts could live relatively ‘free’ lives (Gibbs et al. Citation2017; Karskens Citation2003; Nicholas Citation1988:189). Regardless, there is still a known division between the initial use of the huts at Parramatta as government-controlled accommodation for convict gangs, and later use of them as dwellings with occupants resembling family units in relatively free conditions. For clarity, in this paper we use the terms ‘convict’ and ‘free’ to refer to people under sentence (‘convict’) or not (‘free’); and the terms ‘convict gang use’ and ‘free use’ are used to describe this occupational change.

There has been recent interest in both the extent of remaining evidence of huts in Parramatta and synthesis of the existing results (Allen et al. Citation2022; Shanahan and Gibbs Citation2022), which complements scholarship that extends back to the 1980s when the first convict hut excavations were reported (Higginbotham Citation1985). There are very few other comparative convict sites in Australia from the period prior to around 1818, meaning analysis has been locally focused with few exceptions (for example Karskens Citation2003; Lawrence Citation2003; Staniforth Citation1996). Arguably, both the well-known existing legacy of work and the repetitious nature of examining singular huts—as part of a long line of huts—haunts this research agenda. Are we learning anything new? This question, however, is distinct from whether these sites need to be investigated. The histories of convict huts are intimately tied to settler-colonial practices that violently displaced the Burramattagal, now the Darug people, from their homelands (Owen et al. Citation2022). First Nations people have remained entangled with the cultural landscape of Parramatta and their connection to Country endures into the present (Owen et al. Citation2022). However, the focus here is on how archaeologists can make convict hut research meaningful, assuming these sites will continue to be explored.

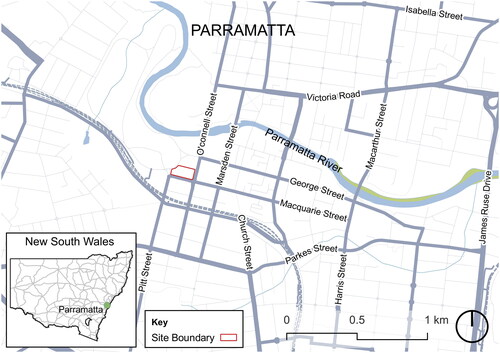

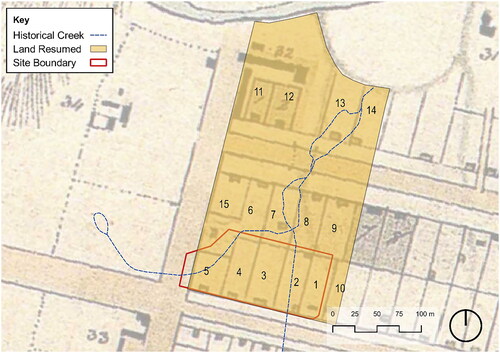

The Club Parramatta site (the site) is located at 2 Macquarie Street, Parramatta () and was excavated by GML Heritage (Citation2023) as part of a redevelopment of the site. The site encompasses parts of six allotments, labelled 1–6 (). ‘Allotments’ is a term used when referring to the entirety of the land parcel; we use ‘huts’ when referring specifically to the dwelling structures. Allotments 1–5 contained six huts, with two huts appearing on Allotment 2 by c.1804 (). Since only a small portion of Allotment 6 was within the site excavation boundary, and it did not contain archaeological evidence from this early colonial phase, it is not discussed further in this paper. Here we compare archaeological evidence of occupation between three huts from Allotments 1 and 2 on the site: Huts A, B and C.

Figure 1. Location of Club Parramatta, 2 Macquarie Street, Parramatta (the site) (Source: NSW Foundation Spatial Data Framework).

Figure 2. Plan of the Club Parramatta site showing the allotments, huts and distribution of archaeological evidence related to the hut phase.

Front and centre in this discussion of the convict huts is the ambiguity surrounding the materiality of the colonial occupants. There were significant developments in the Parramatta landscape in the early colonial period. Convict huts transitioned from temporary accommodation for convict prisoner gangs to tenured dwellings that incorporated a wider range of occupants and uses of the huts, as ‘patterns of urbanisation, privatisation and industrialization’ altered the townscape (Shanahan and Gibbs Citation2022:14). One of the strengths of the archaeological evidence at the site is the short period of European domestic occupation, which spanned between 1788 when colonisers arrived and c.1818 when, through a large land resumption project, the site transitioned to become part of the Government Domain. This, theoretically, makes it easier to disentangle early occupation sequences. At convict hut sites, as for much of the urban archaeology of New South Wales, later nineteenth century occupation, with its industrialised, commercial products of domesticity, generally dominate archaeological evidence, especially the assemblages and the analyses that accompany it. Yet, even with a clear terminus ante-quem and lack of later nineteenth century ‘noise’, the archaeology of these convict huts fails to facilitate concrete differentiation between convict and free occupation. In this paper we argue that the materiality of use of the huts reflects the wider character of settlement—the presence of families, nature of work and habitation, and availability of goods, rather than the ‘free’ or ‘convict’ status of occupants.

The ambiguous temporal resolution of convict huts

As the huts transitioned from government-controlled convict accommodation to tenure through permissive occupancy, the reasons occupants were there, their demographics and their ways of life changed. Defining occupants, and more importantly, the material remains of occupants, as either ‘free’ or ‘convict’ therefore appears critical. Yet, frustrated archaeologists have focused on identifying this distinction without critically examining the inherent ambiguity of the evidence. If this issue is framed as one of temporal resolution, the materiality of convict huts does not have sufficient granularity to pinpoint our findings to particular occupants and their status. At the heart of this debate is whether or not we can assume that evidence of more materially present occupants reflects their freedom or challenges the belief that early convicts lived frugal, materially barren lives. As Higginbotham (Citation1992:65–66) explained more than 30 years ago:

The restricted range of artifacts in the convict huts is usually interpreted as evidence of a harsh way of life, while the presence of Chinese porcelain and other ceramics is taken as evidence of the later free occupation of the huts. When no differentiation can be made between the early and late features of a convict hut, these interpretations seem to rely heavily on assumption … The ideal situation in which to test this question is on a site where the stages in the construction, repair, alteration and additions to a convict hut can be recognised stratigraphically …

The site reported on here, with its cessation of domestic occupation by c.1818, offers an opportunity to address this issue, at least in part. It reduces the timeframe of deposition for the convict-era evidence primarily to the 30-year period between 1788 and 1818. Further, through the records of the land resumption, there are written details of the inhabitants in 1818 at a time when permissive occupancies were generally not recorded. In these ways, the available evidence from the huts discussed here is limited to a more visible dataset, which is generally free from later nineteenth century materials that commonly obscure early forms of evidence.

Allotment occupants

When the land was resumed for the Government Domain, the residents were paid compensation for their removal. All occupants known to have been affected by the resumption are presented in , which correlates with the resumption area shown in . Resumptions began with a small, colonial committee who surveyed and estimated ‘… the value of several old houses and huts which it will be necessary to remove’ (Museums of History NSW Citation1814 – State Archives Collection [MHNSW-StAC], Colonial Secretary Letters Sent, 4/3493). Richard Rouse completed the list in April 1818, as part of Lumber Yard Returns, but did not specify which property belonged to which individual (Kass Citation2018). Further, in addition to Rouse’s survey list, James Wright, Joseph Barsden and William Abbott are known from other Government accounts as separately having land or houses bought by the Government in mid-1818 (The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser Citation1818). In each instance, while only men were listed as receiving compensation, other colonial records show that many of these men had partners and children living with them.

Figure 3. Resumed domain area with interpreted allotments to be resumed. The 1804 Plan of Parramatta has been overlayed (Source: The National Archives UK, Citation1804, Map CO.700.22), with the allotments likely to be included in the resumption highlighted in orange and numbered to allow correlation with .

Table 1. Summary of known lives of occupants of land resumed from the government domain in 1818.

For the most part, the 13 people compensated have not been directly linked to any of the 15 allotments and therefore which of these individuals occupied the six allotments within the excavation area is not known (), although it is possible that further research and mapping of early land tenure could progress identification further through other documentary sources. Some assumptions narrow the list of possible occupants, including by matching compensation paid, as shown in , with our assessment of property values based on allotment size, improvements, topography and position within the township. James Wright and Letitia Holland, and their neighbours Joseph Barsden and Mary Blackman can be linked by documentation of leases to Allotments 11 and 12 (The National Archives UK, Citation1804, Map CO.700.22), meaning they were not occupants at the site we have investigated. William Abbott and Jane Paterson may have lived at Allotment 15, since Wright’s, Barsden’s and Abbott’s lands were resumed separately, potentially as the three premises closest to Government House and those of the most value on George Street. The next most valuable land parcels were likely to have been Allotments 6, 8 and 9 on George Street. Allotment 6 was larger than others, with two dwellings, which would have further increased its value and therefore may have been the property of Robert Tomlinson and Sarah Lister. The huts on Allotments 8 and 9 were investigated during test excavations in 2016, where evidence of the huts, outbuildings, brick paving and other improvements were found (GML Heritage Citation2016). Further, these allotments fronted George Street and were not located within the creek line. Based on these assumptions, it is possible that the next two highest paid occupants, Hugh Hughes living with Mary Underhill, and Thomas Stokes, owned these allotments. John Sanderson appears to have been a regularly employed joiner and carpenter who, alongside his wife Isabella Clarkson, supported a family. Yet, they were only compensated five pounds for their property. They may have therefore been one of the occupiers of a partial resumption, such as occurred with Allotment 10, or alternatively he may have occupied a poor piece of land of little value, such as in Allotments 3 or 7, which were initially not used for convict huts due to their low-lying topography, but did have dwellings on them by 1804.

The remaining allotments were valued at between 10 and 18 pounds each, which is in keeping with Allotments 1–5 which were all of similar size, although little is known about possible improvements and other value-altering factors. In particular, Allotment 2 may have contained two dwellings, or a later structure towards the back of the lot may have replaced the earlier one fronting Macquarie Street.

The inferences so far suggest that the occupants described above were not living on the excavated allotments. Since there were 15 allotments resumed and 13 individuals known to have been compensated, it is noted that two allotments remain unaccounted for. It is possible that two allotments were unoccupied in 1818, or that some occupants tenanted two blocks. Valuations are also likely to have been based on a range of factors not assessable from the fragments of information that remain. The assumptions made here are therefore speculative only and any of those listed in , besides Wright and Barsden, could have lived on the site allotments discussed in this paper. Further, provides only a snapshot of who was on the site in 1818. It does not assist in identifying earlier occupants, either convict or free.

Based on the above discussion, the most likely occupants of the excavated allotments were William Coombes, Mary Mead and their children; William Carroll; Thomas Lanigan; Francis Allen, Sarah Singleton and their daughter; John Carey and Margaret Proctor; or Joseph Marshall. Based on archaeological evidence of the site, Allotment 1 was possibly of higher value (with multiple improvements) and was possibly occupied by a family. It was the only excavated allotment with evidence of children having lived at the site, from the presence of pieces of a child’s tea-set. Allotment 1 (Hut B) may have therefore been occupied by William Coombes and Mary Mead, or Francis Allen and Sarah Singleton. The most likely occupation, however, was blacksmith William Coombes and his family, since Allotment 1 also contained pieces of slag, a waste product of metal-working.

However, despite our efforts to link the list of compensated occupants with allotments, it is clear that the evidence is too fragmentary to be anything other than speculation. With this in mind, it is worth highlighting some overall patterns for all possible occupants of the site in 1818 as shown in . Overall, the evidence presented here indicates that all adult male occupants appear to have had employment, frequently a trade that required some skill, such as wheelwrights, joiners, shoemakers and blacksmiths, or with additional agricultural pursuits including cultivation and livestock on land in the surrounding districts. None was listed on musters as having stock or cultivation on their resumed allotments. Three possible occupants, Hugh Hughes, William Abbott and John Carey, may have had convicts assigned to them, and some of the men were also assigned their convict wives. Approximately half the occupants were families comprising combinations of convict, emancipated and free people. All possible occupants of the excavated site were emancipists by 1818 except for Thomas Sanderson and William Carroll, who may have been still serving sentences in 1818 (). However, as many of the occupants were emancipated between 1806 and 1816, and assuming they had lived there for some time, most transitioned from convict to free while living at the site in the decade leading up to 1818.

Excavation results

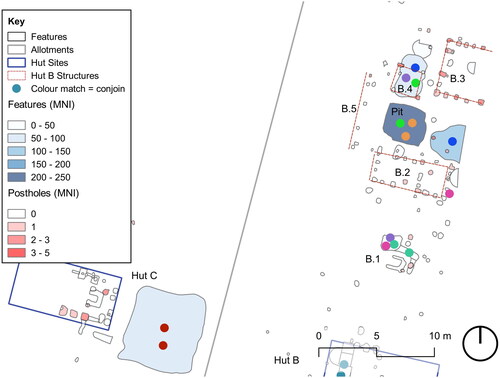

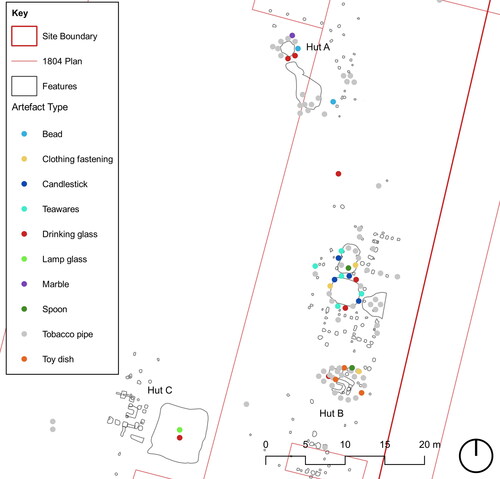

The site contained evidence of four huts, chimney bases, later repairs, and extensions (). The eastern portion of the site was reasonably well-preserved, although post-hole depth and the thin soil profile suggested some truncation across the area. Allotment 1 contained one hut, Hut B, shown first on the 1792 Plan of the Town of Parramatta towards the front of the allotment facing Macquarie Street (The National Archives UK, Citation1792, Map CO.700.4). Post-holes associated with Hut B, along with a range of additional archaeological features behind the hut, could be evidence of a relatively extended period of occupation (discussed below). Allotment 2 contained two huts by c.1804 (Huts A and C), which may have been used by two separate occupants with an informal allotment subdivision, or may have had different occupancies during different periods. Allotments 3 and 4 contained no evidence of the huts. Allotment 5 contained potential evidence of Hut F further to the west, however, due to the lack of associated material remains, this evidence is not discussed further.

Table 2. Summary of the archaeological evidence from huts at the site (Source: GML Heritage Citation2023).

Features associated with Hut B and Allotment 1 exhibited the greatest range of archaeological evidence. Artefact conjoins across the various features indicate that the structures and the pits were mostly contemporary (). Structure B.3 was determined to be a later addition relative to the other structures, based on the density of artefacts within post-hole fills. Although inconclusive, Structure B.1 was more likely to relate to domestic uses, as the features contained children’s toys and it was closer to the main dwelling to the south. The children’s toys were miniature vessels of local manufacture, with both lead glazed and unglazed examples made from fine white clay, possibly imitating white porcelain tea-sets. A local potter, Samuel Skinner, was known to sell tea-sets in the area in 1803–1804 (Casey Citation1999), and examples of tea-set pieces were also found on the Thomas Ball pottery excavation at Brickfield Hill, Sydney (Casey & Lowe Citation2011). The pieces found in the excavation of Hut B were clustered in fills of possible structural features to the north of the site (labelled B.1, ), suggesting they related to a single set of occupants.

Figure 4. Plan of Huts B and C and associated features, showing artefact densities and key conjoins between features. Artefacts are counted by minimum number of individuals (MNI), with brick pieces excluded from artefact counts in post-holes.

The ‘C’ shaped feature at Hut B was probably the location of a chimney base, although the linear trenches outside this feature are difficult to interpret. Therefore, Structure B.1 might also be evidence of a detached kitchen. The presence of domestic items like buttons, drinking glass fragments and a spoon support this conclusion. However, the supposition is inconclusive because these items appear in such small quantities, and were also found elsewhere. The rectangular, timber-lined pit in Hut B (see ‘Pit’, ), was interpreted as a cellar. Structures B.3 and B.4 could have been additional outbuildings or structures associated with Hut B. Structure B.3. could have been a small workshop, which is supported by its later construction, larger footprint and associated artefacts. For instance, a number of the artefacts within the post-hole fills of B.3 were pieces of slag from metal-working.

Archaeological and documentary evidence for Allotment 2 provided evidence of two huts, although it is unclear whether these represented concurrent or successive occupations. Hut C was built first and appears on the 1792 plan of Parramatta fronting Macquarie Street (The National Archives UK, Citation1792, Map CO.700.4). Evidence of the eastern half of the hut was found, the western half having been destroyed by a modern stormwater drain. The architectural evidence showed a ‘C’ shaped chimney base and post-holes, some with repairs or extensions. Artefactual evidence was limited to finds within a small range of post-holes, dominated by architectural materials, and a large, amorphous pit a couple of metres to the east of the hut, which was interpreted as a pond. The pond contained two deposits, the lower appearing to date to the late 1790s based on the artefacts found therein, with the upper deposit being of similar or slightly later age. Hut A was located to the back of the allotment and first appears on the c.1804 plan of Parramatta (The National Archives UK, Citation1804, Map CO.700.22). The hut was composed of round post-holes in an arrangement suggesting a large, single room. Near the hut there was evidence of post-holes, possibly forming a fence line. There were also other post-holes from a possible small outbuilding, and a round rubbish pit with an unstratified but artefact-dense fill. A scatter of artefacts was found near Hut A, and a high density of brick and surface artefacts was found directly to the south of the hut site within 10 m of the hut.

The archaeological evidence agrees with the literature on the availability and usage of everyday objects. For example, archaeologists have variously concluded that artefactual evidence indicates that low-income occupants purchased affordable, utilitarian items, for example lead glazed tableware and food preparation vessels that were cheaply available in early colonial NSW (Casey and Hendrickson Citation2009; Godden and Wilson Citation1996; Pitt Citation2019; Staniforth Citation1996; Stocks Citation2008). The assemblages excavated from the three huts at the Club Parramatta site support these claims. While a small range of fine quality or decorative items were found on the site, these are associated with a slightly later occupation phase, which is therefore more likely to date after the transition to free settlement.

Archaeological evidence at the site can broadly be divided into two phases: the assumed occupancy for convict gang use and soon after (Hut C); and the slightly later free use of the dwellings (Huts A and B). Although these conclusions are tentative, and rely on single rubbish or infilled pits associated with each hut, this phasing can be used to explore the materiality of this occupational shift. Artefacts near Hut C were associated with 1790s occupation and express a frugality in the material culture of early convict Parramatta. In contrast, the evidence interpreted as having been associated with Huts A and B supports later and possibly more materially diverse occupation, including the building of additional structures. For example, all of the beads and the majority of lamp glass elements were found near Hut A, along with a wide range of local and imported ceramics (). As discussed above, Hut B had spoons, teawares and toy dishes associated with it. Features around both Huts A and B also contained tobacco pipe pieces. This can be compared to the material found in the pond associated with Hut C, which was dominated by a narrow range of early, and coarse, locally produced wares and no tobacco pipes. There were also higher ratios of British imported wares around Huts A and B and a higher ratio of Chinese imported porcelains and early lead glazed wares around Hut C.

Figure 5. Select artefact types from around Allotment 1 and 2 structures. Each coloured point represents one artefact by MNI, which are centred around the feature with which they were associated.

While the evidence appears to express the convict/free divide of this colonial landscape, the arguably more critical changes at the site summarised above relate to the nature of the occupancy. The variable convict status of the possible occupants suggests that this was not a significant factor in the changes to the material remains of the huts. The huts were initially occupied by groups of convict men who were working in Parramatta in a relatively transient manner, but at some stage the huts became occupied under permissive occupancy. It was therefore this transition, possibly occurring in around 1800, that altered the nature of habitation, rather than any status of ‘convict’ vs ‘free’. The key difference relates to the associated agency of tenure, which is likely to have provided a catalyst for fencing, architectural improvements, drainage and the creation of more substantial gardens. There is no evidence that permissive occupancy is necessarily associated with emancipated or free residents, since many huts appear to have been occupied by convicts until well into the 1810s.

Convict huts as assemblages of practice

In gathering together the archaeological evidence from the site, we need to ask: what do the pits and post-holes tell us that is not already known? We now know that the occupants of the huts were individuals and families, workers and homemakers. To facilitate a discussion about the lives associated with the convict huts, we bring the ‘things’ excavated from the site into assemblages of practice that entangle them with the humans with whom they have shared dependence and dependency (Antczak and Beaudry Citation2019). Assemblages of practice is an analytical tool used to help explore change, continuity and transformation across materiality, drawing in the people in each entanglement. Such a method is guided by recent developments in more-than-human approaches, for example Casella (Citation2016); Hodder (Citation2012); Ingold (Citation2015); and notably the work of Antczak and Beaudry (Citation2019). These authors have argued that ‘a thing cannot be a proxy of practice by itself, bereft of its relational entanglements with humans and other-than-human things’ (Antczak and Beaudry Citation2019:96). By this we mean that rather than examining archaeological objects as static relics of the past from which we may interpret the practices of people, we reconceive of these as vibrant things entangled with humans in daily events of relational practice. Using assemblages of practice theory, and working with the interpretation about the potential phasing and occupation of the huts, we are able to tease out some novel detail.

There were infinite assemblages of practice formed around life in this hut context, as ‘things’, human and non-human, assembled and reassembled continuously through everyday events. The earth was turned for crops planted and grown, and in doing so turned over and over things held on to and then discarded at the site. Things packed inside vessels criss-crossed on trade voyages from perhaps China or England, things picked up and put down in consumer purchases or clutched through the endless voyages of convicts or migrants in their waves of colonisation. Things contraband in government regulation and things dealt out in regulation rations. The assemblages draw in the site features, artefacts, people and events of the past, while acknowledging archaeologists as part of these. It must be acknowledged that our interpretations of the site are inherently linked to the present. While the temporal and spatial resolution of archaeological evidence at the site does not allow us to understand every potential assemblage of practice, this discussion does conceive of three particular assemblages of practice, each centred on ‘things’ that were likely to have been associated with one of the huts: a kitchen table, a spade, and a storage crock (see below).

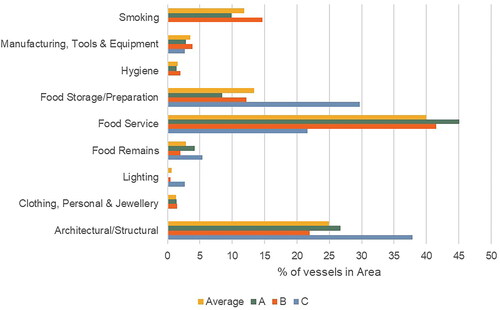

Functional artefact analysis shows different ratios across the features of Huts A, B and C (), hinting at the impact of site formation processes on the excavation results, rather than solely occupation change. For example, artefacts relating to manufacture and food were relatively consistent across all allotments, possibly indicating the necessity of labour tasks to all occupants. However, Hut C had a much higher ratio of architectural materials, perhaps reflecting cultural formation processes associated with abandonment more than deposition during occupation. Considering the consistency of repair and alterations in convict hut histories, higher frequencies of architectural materials may reflect a focus on the hut as requiring attention. Regardless, these ambiguities around deposition are acknowledged and add texture to the assemblages of practice.

Figure 6. Functional analysis of artefacts from major features near Hut A (round rubbish pit), Hut B (rectangular pit, adjacent rubbish spreads and linear features of B.1) and C (pond), showing artefact functions as a percentage of the total artefacts by MNI in each area and an average across the site, excluding artefacts of unidentifiable function.

For the purposes of exploring site transformation, the first assemblage of practice is brought together around a kitchen table inside a hut. The table, while archaeologically absent, can be used to characterise Hut C, as a ‘thing’ pulling other human and non-human things into action. Perhaps due to the shared nature of early convict transient occupation, or perhaps insufficiency where resource sharing was necessary, the assemblage of practice points to themes of communal life. Gathered into this assemblage are occupants, probably not those seen in , but earlier convicts, brought to Parramatta against their will and then gathered uneasily around a rough table pockmarked with use: a familiar object in a foreign landscape. These people were male but otherwise a diverse group, the sentence that hung over them potentially their only common connection. The paucity of tobacco pipes near Hut C is in contrast to a relative abundance of such objects near Huts A and B. Unlikely to be entirely absent, a whiff of stale tobacco smoke probably lingered about the hut. Perhaps it was a habit of familiarity and addiction (Gojak and Stuart Citation1999), associated with long working hours and tough conditions. Occupants may have coveted any available tobacco pipes to allow them to find a quiet moment alone for a puff at the table. Although it is also possible that convict regulation or the scarcity of goods means this absence of evidence reflects an absence of use.

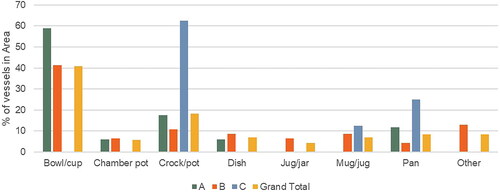

This assemblage of practice establishes the table as a place of dimly lit work, as Hut C was associated with tools and utilitarian vessels for food preparation and storage. Whether convicts privately laboured in their own time or for domestic comfort, this was a table of practical means. There are few ‘things’ that we can pull into this assemblage of practice that indicate what may have been cut, cooked or eaten at the table, possibly reflecting a simple diet of government rations coupled with unforgiving site formation processes. The lead glazed items at this table were coarse, with an abundance of crocks, pans and pots (). These were vessels for sharing; a communal life of pots hung over open fires, as evidenced through blackened bases, with bubbling one-pot meals and food shared around a table. It may have been associated with the divvying up of meals that involved individual mess kits, potentially made of wood or metal, that have not survived to be part of this assemblage of practice now. The most functionally individual item is a coarsely formed mug or jug splashed in faux ‘mulberry ware’ lead-glazing (Pitt Citation2010:27–28), an imitation of a finer vessel from back home that was probably unattainable.

Figure 7. Comparison of locally made vessel forms from major features around Huts A (round rubbish pit), B (storage pit, adjacent rubbish spreads and linear features of B.1) and C (pond), showing artefact forms as a percentage of the total artefacts in each area and the total of all three together. Analysis excludes artefacts of unidentifiable forms and merges some form categories for simplicity.

Evidence at Hut A suggests different people and things, this time centred around a spade. The spade assembles things a little more characteristic of a burgeoning township, when the occupants could have potentially selected this particular dwelling for themselves. A spade would have cleaved the earth apart in an act of agency for the digger, and in doing so, that part of Darug Country was forevermore altered against the will of its custodians. The hole that was dug, perhaps one of the post-holes associated with the hut, a planting or a refuse pit, represents the practices of growth around a home. This hut was out of alignment with the huts fronting Macquarie Street in their regulation spacing (). This was perhaps an expression of individuality of one of the occupants identified in . For example, Thomas Langham, a lone labourer who was blind in one eye, or convict Sarah Singleton with baby Ann, could have been wielding the spade. The occupants, in energetically shaping their home, fuelled their days by eating at least some beef and lamb, most likely pieces bought off site and supplemented with shellfish collected from the estuarine environment of Parramatta River a few hundred metres north of the site. Other personal items assembled here reflect home-making of a more individualistic nature, including beads, a marble, drinking glasses, coins, fine English wares and tobacco pipes. Discarded with breakages or lost through labour like digging, these items were part of consumer choices bound up in their idea of home.

The third assemblage of practice incorporates freedoms of domesticity associated with Hut B. These human and non-human things were assembled this time around a storage crock. Here in the present, we can imagine that hands would have opened and closed the crock many times, to pull out or replace food stocks such as flour, salted meat or salt. The crock represents greater material abundance and variety. The butchered skull of a cow and lower limbs of cows and sheep are entangled here, suggesting complete or partial home butchery behind the hut. An ensemble of non-human remains including cow, sheep, pig, horse and rabbit bones alongside a range of estuarine shells are also drawn in from a diversity of domestic activities and eating habits. Utensils and cooking vessels include spoons and knives, a tripoded cast iron cooking pot, lead glazed pots and crocks, pans and jugs. The wear of cooking pots is evidenced by the flaking off of the lead glaze through the repeated actions of stirring. Candlesticks—the candles once with them long ago burnt into pools of wax—speak to busy lives that continued well into the night.

The occupants of Hut B, probably Mary Mead, William Combes and their three children, lost or discarded many things through their daily practices. It is clear that the fortunes of this family provided enough stability and wealth to permit the purchase of tobacco pipes, alcohol, stemmed drinking glasses, cups, mugs, teawares and even toy teawares allowing the young ones to emulate ‘civilised’ life. The consumer choices reflect a valuing of individualism, but the assemblage of practice highlights the actions of these things, such as domestic or industry labour, children’s games, construction, accumulation and aspirational growth. Between c.1810 and 1816, both adults were emancipated, having served their time. If the archaeological evidence of Hut B predominantly accumulated throughout the two decades following c.1800, it suggests continued free use of the site, not specifically ‘free’ occupants.

While archaeologists may see the ‘assemblage’ in an assemblage of practice as purely artefactual, all forms of evidence can be included. The assemblages of practice at the site incorporate dozens of post-holes, as structures were hoisted up and into use. Industry from the site was also buried within features, such as the little flecks of slag from William’s blacksmithing practices that were apparently so abundant that they were dug into multiple post-holes. Repetitions are helpful in this content and the meagre post-holes provide clear patterning of use.

Assemblages of practice are a theoretical tool for entangling local specifics within a wider contextual landscape because assemblages draw in things, people, events and themes at any scale. Archaeologists have long been seeking wider analyses of convict huts. Casey raised spatial and contextual analyses back in 2009, stating ‘[t]here has been limited analysis of the development of Parramatta’s landscape from an archaeological perspective and while there have been numerous excavations there has been little exploration of these sites within the context of this evolving landscape’ (Casey Citation2009:7). Comparative work has occurred for hut structures (Lawrence Citation2003; Parker Citation2006), but theorising people and the detail of their lives in this research agenda has lagged behind. These three assemblages of practice utilise New Materialism to engage with evidence and its relationship to other things, the present, the past and people. Based in archaeological evidence, each description aims to explore themes and highlight comparisons that introduce vibrancy and life, while maintaining a wider colonial context of occupational change.

Conclusion

It is clear that the archaeological evidence of Parramatta prior to c.1818 has weak temporal resolution, despite archaeologists recognising that this was a period of substantial change and growth. In returning to the question of whether we are learning anything new, it is clear that the huts are repetitious in their architecture, form and shared history. However, their regularity is in fact a strength that reveals nuance and change across allotments. While the convict/free divide is not identifiable, the three assemblages of practice show that the archaeological evidence can be used to characterise the changes in site occupation. This nuance and detail from individual huts can give archaeologists a communal table (or a sturdy crock, or a spade) through which to consider the lives of colonists.

It has been argued here that convict or free status of occupants is also not meaningful considering the range of other factors that are likely to have contributed to the materiality of the occupants’ lives. While we may identify these structures as ‘convict huts’ in origin, archaeologists can use the assemblage of practice approach to move beyond dualisms such as convict/free and consider a wider and more active range of themes. As many have noted, convict huts can reflect labour, settler colonial conflicts, organisational practices and agriculture, and shifting urbanisation, personal growth and identity (Casey and Hendrickson Citation2009; Shanahan and Gibbs Citation2022). Whichever themes are explored, ambiguities with the data will persist across every future excavation and analysis. Research needs to engage more directly with temporal resolution issues. Nevertheless, escaping the particularism of huts is also important and we should look at other colonised landscapes, such as Norfolk Island, rural Australia and even further afield, as well as these same landscapes from First Nations perspectives.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable and detailed feedback provided by anonymous reviewers. The authors would also like to acknowledge the excavation and analysis team. The excavation director was Abi Cryerhall. Dr Caiti D’Gluyas, Sophie Jennings, Dr Erin Mein and Kieren Watson were site supervisors. The following archaeologists were also involved in fieldwork—Liam Beiers, Emily Bennett, Andrew Brown, Julio Centelhas, Adrian Dreyer, Riley Finnerty, Hannah Morris, Bronwyn Partell, Yolanda Pavincich, Alana Pengilley, Adam Pietrzak, Ruby Stewart and Susan Whitby. The analytical team included Dr Caiti D’Gluyas (GIS and artefact analysis), Guy Hazell (surveyor), Dr Jugo Ilic (wood identification), Terry Kass (historian), Mike Macphail (pollen analysis), and Dr James Roberts (faunal analysis).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, C., M. Butcher, L. Harley and J. Madden 2022 Understanding the cumulative impact of development on ‘convict hut’ sites across the Parramatta CBD. In Sydney Historical Archaeological Practitioners’ Workshop. Camperdown: University of Sydney.

- Antczak, K.A. and M.C. Beaudry 2019 Assemblages of practice: A conceptual framework for exploring human-thing relations in archaeology. Archaeological Dialogues 26(2):87–110.

- Casella, E.C. 2016 Horizons beyond the perimeter wall: Relational materiality, institutional confinement, and the archaeology of being global. Historical Archaeology 50(3):127–143.

- Casey & Lowe 2011 Archaeological Investigation 710–722 George Street, Volume 4. Haymarket: Thomas Ball Appendices. Unpublished report prepared for Inmark.

- Casey, M. 1999 Local pottery and dairying at the DMR site, Brickfields, Sydney, New South Wales. Australasian Historical Archaeology 17:3–37.

- Casey, M., 2009 Parramatta’s archaeological landscape. In M. Casey and G. Hendrickson (eds), Breaking the Shackles: Historic Lives in Parramatta’s Archaeological Landscape, pp.7–14. Parramatta: Parramatta Heritage Centre and Casey & Lowe.

- Casey, M. and G. Hendrickson (eds) 2009 Breaking the Shackles: Historic Lives in Parramatta’s Archaeological Landscape. Parramatta: Parramatta Heritage Centre and Casey & Lowe.

- Gibbs, M., B. Duncan and R. Varman 2017 The free and unfree settlements of Norfolk Island: An overview of archaeological research. Australian Archaeology 83(3):82–99.

- GML Heritage 2016 Parramatta Park Gardens Precinct—Historical Archaeological Test Excavation Report. Unpublished report prepared for Parramatta Park Trust.

- GML Heritage 2023 Club Parramatta, 2 Macquarie Street, Parramatta—Historical Archaeological Investigation Results. Unpublished report prepared for Paynter Dixon.

- Godden, M.L. and G. Wilson 1996 Cumberland Street/Gloucester Streets Site Archaeological Investigation. Specialist Reports: Ceramics. Unpublished report prepared for the Sydney Cove Authority 4 1994, Volume Part 2.

- Gojak, D. and I. Stuart 1999 The potential for the archaeological study of clay tobacco pipes from Australian sites. Australasian Historical Archaeology 17:38–49.

- Higginbotham, E. 1985 The Early Settlement of Parramatta, 1788 to c1830 and the Proposed Archaeological Excavation of the Site of Family Law Courts and Commonwealth Government Office Block at Parramatta, NSW. Unpublished report prepared for Department of Housing and Construction.

- Higginbotham, E. 1992 Report on the Archaeological Excavations in Advance of Cable Laying of the Site of the Telephone Exchange, 21A George Street, Parramatta, NSW. Unpublished report prepared for Telcom Australia.

- Hodder, I. 2012 Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things. Chichester: Wiley.

- Ingold, T. 2015 The Life of Lines. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Karskens, G. 2003 Revisiting the worldview: The archaeology of convict households in Sydney’s Rocks Neighborhood. Historical Archaeology 37(1):34–55.

- Kass, T. 2018 History of the Site of Parramatta RSL Club, Macquarie Street, Parramatta. Unpublished report prepared for GML Heritage.

- Lawrence, S. 2003 Exporting culture: Archaeology and the nineteenth-century British Empire. Historical Archaeology 37(1):20–33.

- Museums of History NSW—State Archives Collection [MHNSW-StAC] 1814 Colonial Secretary Letters Sent, 4/3493, Colonial Secretary Campbell to Rouse 1814 Oakes and Hall, Sydney, 16 February.

- Museums of History NSW—State Archives Collection [MHNSW-StAC] Convict Indents and Ship Musters, NRS 12188, 1788–1820. Sydney.

- Museums of History NSW—State Archives Collection [MHNSW-StAC] General Musters, NRS 1260, 1801 1806 1811, 1814, 1822, 1825. Sydney.

- Nicholas, S. 1988 Convict Workers: Reinterpreting Australia’s Past. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

- Owen, T.D., J. Jones, L. Watson and C. Norman 2022 Parramatta, NSW: A deep time Aboriginal cultural landscape. Journal of the Australian Association of Consulting Archaeologists 9:10–29.

- Parker, M. 2006 Rethinking the Convict Huts of Parramatta: An Archaeology of Transformation, 1790–1841. Unpublished BA(Hons) thesis, University of Sydney, Sydney.

- Pitt, N. 2010 Making Do: Manufacturing Finer Pottery in Sydney in the Early Nineteenth Century. Unpublished BA(Hons) thesis, University of Sydney, Sydney.

- Pitt, N. 2019 Clay and ‘civilisation’: Imperial ideas and colonial industry in Sydney, 1788–1823. History Australia 16(2):375–398.

- Plan of the Town of Parramatta in New South Wales. [Sydney] MS. 225 feet to 1 inch. The National Archives, Kew (UK), Map CO 700/NewSouthWales4, 1792.

- Plan of the Township of Parramatta. By G. W. Evans, Acting Surveyor, [Sydney]. MS. 800 feet to 1 inch. The National Archives, Kew (UK), Map CO 700/NewSouthWales22, 1804.

- Shanahan, M. and M. Gibbs 2022 The convict huts of Parramatta 1788–1841: An archaeological view of the development of an early Australian urban landscape. Post-Medieval Archaeology 56(1):80–96.

- Staniforth, M. 1996 Tracing artefact trajectories following Chinese export porcelain. The Bulletin of the Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology 20(1):15–20.

- Stocks, R. 2008 New evidence for local manufacture of artefacts at Parramatta, 1790–1830. Australasian Historical Archaeology 26:29–44.

- The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 1818 Saturday 6 June p.1.