Abstract

The growing literature on underfloor archaeological deposits often observes exceptional material preservation within these matrices. Drawing from recent work at Fremantle Prison, this paper reports on the site formation processes that produced the rich preservation of the underfloor deposit of Fremantle Prison’s cell D40. These site formation processes are characteristic of non-soil underfloor deposits and explain why these types of archaeological sites enable the preservation of fragile, organic materials. This understanding of material preservation and decomposition enables a holistic understanding of the deposited materials and related human behaviour over time.

Introduction

Excavations of underfloor archaeological deposits have increased in the past two decades (Auld et al. Citation2019; Beisaw Citation2009; Bryant et al. Citation2020; Casey Citation2004; Crook et al. Citation2003; Crook and Murray Citation2006; Davies Citation2011, Citation2013; Davies et al. Citation2013; Dirks Citation2013; Drummond-Wilson Citation2018; Eureka Consulting Citation2010; Green Citation2018; Martin Citation2019; Mein Citation2012; Murphy Citation2003, Citation2013; Percival Citation2004; Robertson and Haast Citation2013; Starr Citation2015; Terra Rosa Consulting Citation2021; Winter Citation2015; Winter et al. Citation2021; Winter and Romano Citation2017, Citation2020). Many studies observed exceptional preservation of artefacts such as paper, textiles, leather and other organic materials (Bryant et al. Citation2020; Davies et al. Citation2013:15; Winter and Romano Citation2020:333). While most authors have experienced this exceptional preservation in underfloor deposits, little research has been conducted into why these deposits preserve organic cultural material so well. This paper reports on the site formation processes that enabled the preservation of material culture in the underfloor deposit of cell D40 at Fremantle Prison, Western Australia.

Historical background

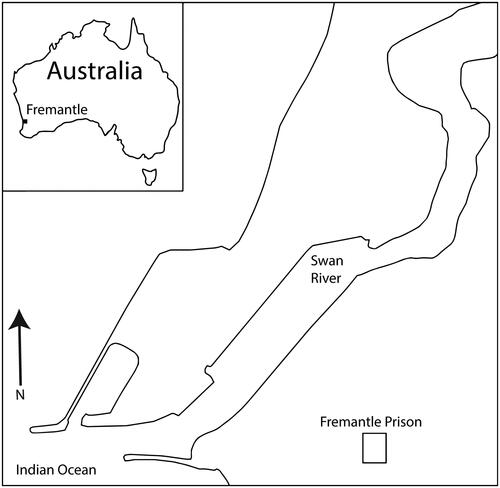

In 1829, the Swan River Colony was established as a free British colonial settlement, unlike other Australian colonies already formed in New South Wales and Tasmania as penal settlements (Bosworth Citation2004:vii). However, the free settlement was short-lived, with the Crown converting Western Australia into a penal colony in 1849 due to labour shortages and economic depressions (Bosworth Citation2004:vii; Kerr Citation1998:1; Statham Citation1981:7–8). Transportation soon followed, with the first 75 male convicts arriving on 1 June 1850 at Fremantle, Western Australia, with no suitable gaol to house them (Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage Citation2020; Government of Western Australia Citation2009:1). The convicts slept aboard their ship, “Scindian”, until a temporary gaol was established at a warehouse at South Beach, Fremantle (Government of Western Australia Citation2009:1). In November 1852, the construction of Fremantle Prison commenced, with the project led by Captain Edmund Henderson of the Royal Engineers, and the Comptroller General of Convicts, at a site overlooking the town () (Bosworth Citation2004:49; Department of Treasury and Finance Citation2010; Megahey Citation2000:13). The prisoners began working on the Convict Establishment while Captain Henderson and professional tradesmen oversaw the project (Megahey Citation2000:13). Fremantle Prison was built in stages, commencing with the main cellblock (Government of Western Australia Citation2009:7). The southern wing of the main cellblock was constructed first, housing convicts from 1 June 1855, followed by the northern wing, completed in 1859 (Government of Western Australia Citation2009:7–8). Prisoners spent most of their time locked up in overcrowded cells with only a bucket as a toilet (Dixon Citation2010:306; Jones Citation1973:162–163; McGivern Citation1988:14). Fremantle Prison was continuously occupied for 136 years from 1855 until its closure in 1991.

Site significance

Fremantle Prison is highly significant in telling an important story of Australia’s convict past and is Western Australia’s only built World Heritage Site. In 1995 Fremantle Prison was permanently listed on Western Australia’s State Register of Heritage Places (Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage Citation2020). In 2010 it was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in a serial listing of highly significant Australian convict sites under the theme of ‘Convictism–Forced Migration’ along with ten other sites including Hyde Park Barracks [Sydney], Cascades Female Factory [Hobart] and the Port Arthur Historic Site [Tasmania] (Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage Citation2020). Beyond convictism, Fremantle Prison is highly significant because it demonstrates the changes in Australian society and institutional confinement over 136 years.

Archaeologically, Fremantle Prison is highly significant as previous archaeological fieldwork has revealed outstanding preservation of organic material in underfloor deposits (Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage Citation2021:48). Other underfloor excavations in standing structures around Australia also yielded remarkable preservation of organic materials similar to that at Fremantle Prison, including the Royal Derwent Hospital [Tasmania] and the Hyde Park Barracks [Sydney] (Auld et al. Citation2019; Bryant et al Citation2020; Crook et al. Citation2003; Crook and Murray Citation2006; Davies Citation2011, Citation2013; Davies et al. Citation2013; Starr Citation2015). Examples of artefacts found across these sites include textiles, paper, leather, matchsticks, matchboxes and books (Auld et al. Citation2019; Bryant et al. Citation2020; Crook et al. Citation2003; Crook and Murray Citation2006; Davies Citation2011, Citation2013; Davies et al. Citation2013; Starr Citation2015).

Methodology

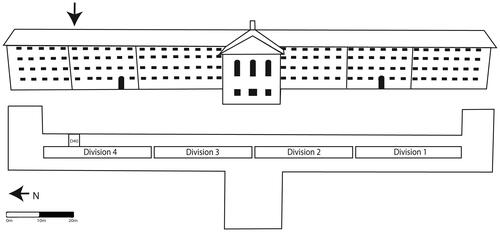

In the summer of 2019–2020, Fremantle Prison completed urgent conservation works for failing lathe and plaster ceilings. The method to stabilise the ceilings involved a product requiring that the roof cavity be free of sediment and debris. Time restraints, owing to the urgency of preventing loss of material from falling ceilings, prevented on-site sieving, so the deposits were excavated in spits straight into plastic bags for future analysis. Following the excavation of material, cell D40 in Division 4 on the first level of the north east side of the main cellblock () was selected for rigorous analysis of the deposit and material culture. This particular deposit was selected based on the observation that large quantities of fragile material culture were preserved.

Figure 2. Fremantle Prison main cellblock showing the location of cell D40 on the north east side of the first floor (Drawing: Paige Taylor).

Under ‘normal’ excavation conditions, artefact assemblages retrieved as a result of the excavation process are biased, because archaeological excavations require on-site decisions regarding what material to keep or discard (Sutton and Arkush Citation2014:15). In addition, sieving in the field results in the loss of small artefacts due to sieve size. The excavation methodology in this project presented unique circumstances for artefact recovery as the whole deposit, the matrix, consisting of the extant building, sediment, artefacts, and non-artefacts, was available for study. Having possession of all these elements enabled the analysis of the entire deposit to determine what material was present or missing due to cultural and natural site formation processes, rather than biases created by archaeological methods. This enabled an in-depth study of an entire deposit of a select cell.

The excavation area of cell D40 was divided by the area between floor joists, creating seven areas between the east and west walls. Each joist space was then arbitrarily divided into three equal sections, creating twenty-one contexts measuring 400 by 300 mm in a cell measuring 2.9 m by 2.2 m (Danial Holland, pers comm. 2020). The excavation was conducted with a brush and vacuum cleaner, with contexts removed in one to three arbitrary spits, depending on the thickness of the deposit. The first spit consisted of a surface collection of artefacts by hand, followed by a spit excavated with a brush. The final spits were excavated using a vacuum cleaner. Not all contexts have three spits, as some contexts were so shallow they were excavated entirely with a vacuum cleaner.

Post-excavation investigations commenced with sieving the matrix through an Endecotts 1.18 mm Laboratory Test Sieve, testing each spit’s pH, sorting artefacts by type, and weighing the recovered finds using one of two scales: a Digital Precision Platform scale accurate to 0.01 g for light objects; and on a Compact Bench digital scale accurate to 0.5 g for heavier material that exceeded the Digital Precision Platform scale weight limit.

Artefacts recovered

The total weight of the deposit in cell D40 was 37.5 kg, comprising 24.5 kg of sediment, 12.4 kg of artefacts and 0.6 g of non-artefacts. Of the cultural material excavated from the underfloor deposit, 1.35 kg, or 10.9%, consisted of organics not typically preserved in archaeological sites (). Many of the artefacts recovered exhibited exceptional preservation including shoe soles (), cigarette paper and packets, matches and matchboxes, milk cartons, books (), envelopes, a sporting fixture, military pamphlets, a playing card, newspapers, magazines, pencil shavings, organic bottle stoppers, medical gauze, a sleeve cuff, a section of a blue and white striped shirt and bone buttons.

Figure 4. The Gospel According to St John book excavated from cell D40 c.1936–1952 (Photograph: Fremantle Prison).

Table 1. Weights of organic artefacts from cell D40 deposit.

Site formation processes

While cultural site formation processes determine how cultural material is deposited, moved and removed by humans, natural site formation processes inform an archaeologist about what has and has not been preserved. Natural site formation processes, defined as transformations of material through natural environmental changes, consist of chemical, physical or biological factors (Schiffer Citation1987).

Physical processes

Cell D40’s matrix determined the survival, disintegration and alteration of archaeological material. Cell D40’s matrix consisted of debris and sediment deposited since its construction circa 1859. The material, enclosed between the floorboards, limestone walls and ceiling of the room below, was protected from irradiation by sunlight. This enclosure produced a dry matrix that desiccated the archaeological material, preserving artefacts like paper. The natural thermal insulation properties of the limestone walls protected the archaeological material from rapid fluctuation in temperature and humidity (Shaeri et al. Citation2018:134). The matrix shows evidence for moist periods indicated by small fungal colonies accreted onto wood, plywood and paper. However, limited damage to these materials indicates that mould growth was short-lived. Previous research by Mein (Citation2012:75) on a non-ground underfloor deposit, cell F63, at Fremantle Prison produced similar preservation results to cell D40. The preservation of fragile material in cell F63 and cell D40, including paper and textiles, demonstrates that the physical characteristics of non-ground underfloor deposits promote exceptional preservation of organic material. In comparison, ground floor deposits at Fremantle Prison, such as cells A20 and A7, and the Fremantle Prison Hospital, did not yield the same preservation results, with organic materials either having wholly or partially decomposed (Mein Citation2012; Nayton Citation1998; Terra Rosa Consulting Citation2021).

Differences in preservation can be attributed to the quantity of sediment within a deposit, which impacts the original ventilation system. During the Prison’s operation before 1991, soil levels abutting buildings were gradually built up covering external vent openings, leading to rising damp and ultimately resulting in the decomposition of fragile material in impacted areas. The decomposition process caused by rising damp could be seen in the excavations at the Fremantle Prison Hospital (Terra Rosa Consulting Citation2021). A sanitary engineer, Mr J.P. Bedforth, during the 1899 Royal Commission on the penal system of the Colony of Western Australia, reported that the prison’s ventilation system had been compromised in some areas due to intentional alterations such as blocking the openings at the bottom of each cell door to prevent escape attempts (Craig et al. Citation1899:79–80). Unlike other areas in the prison, the ventilation system aerating cell D40 was intact and operational, contributing to the preservation of an abundance of fragile artefacts found in the deposit.

Chemical processes

It was expected that the pH of the deposit in cell D40 would be acidic due to the high decomposition of organic materials such as urine (pH 6.0) and skin cells (pH 5.5) over more than a hundred years of crowded human occupation, with bucket toilets the only sewerage system (Dixon Citation2010:306; Jones Citation1973:162–163; McGivern Citation1988:14; Nall Citation2020; Porter Citation1980:16). However, the pH of cell D40’s deposit was alkaline. It is probable that Fremantle Prison’s construction materials—limestone—produced this result, as sediment and debris from the cell’s thick limestone walls were found in the deposit. Limestone is alkaline; it neutralises strong acids, is porous, and has a large surface area, which reacts well with acidic materials (Digital Analysis Corporation Citation2019). The walls were also coated in limewash, a product containing calcium carbonate (Bosworth Citation2004:50). Over time, these alkaline materials crumbled into the underfloor deposit, neutralising the acid-based materials and producing an alkaline environment (Digital Analysis Corporation Citation2019).

An exception to the alkaline pH was observed in two spits with neutral pHs. These two spits were bound by their proximity to a leather shoe sole artefact (). This pH reading was probably created by the leather shoe sole’s highly acidic nature, which neutralised the surrounding matrix. The leather tanning process requires an acidic pH of 2.5 − 3 to allow even tanning (Jackson-Moss Citation2020). Thus, the chemical reaction of a highly acidic artefact and highly alkaline matrix counteracted each other to create a neutral pH environment. The shoe soles demonstrate that artefacts themselves can have a significant impact on their surrounding matrix.

Biological processes

Insect remains were recovered from every spit analysed. When possible, they were identified to the Genus level (; Godfrey and Gilroy Citation2017; Mein Citation2012:123–126). Unidentified insect parts include wings, an arachnid egg sack, and a moth. While insects undoubtedly impacted the archaeological record and damaged fragile material, the dry nature of the deposit prevented the area from becoming a haven and feast for the insects. Although some objects such as the book The Gospel According to St John () show evidence of superficial insect boring and consumption, the fact that the artefact still exists and is readable means that the insects did not consume everything.

Table 2. Insect species identified in deposit from cell D40.

Evidence for rodents in the deposit comprised skeletons, gnawed artefacts and faeces. Rat faeces were only found along the north and south walls of cell D40, whereas mouse faeces were found throughout the cell. The distribution of mice faeces reveals they were small enough to access the entire cell. Their small size enabled them to squeeze between floorboard and joist gaps (Abarb Pest Services Citation2017). Mice probably impacted preservation by consuming organic materials such as food remains and paper to make nests. The location of rat faeces strongly suggests that rats could only access the underfloor cavity through gaps in the floorboards along the north and south walls. Evidence suggests rodents only gnawed newspapers, magazines and non-rodent bones.

Conclusion

While archaeologists have observed that underfloor deposits support exceptional preservation, limited research has been conducted into the site formation processes that create this phenomenon. It is of the utmost importance for archaeologists to understand the unique preservation processes of underfloor deposits to interpret the human behaviour that produced the archaeological record accurately. Research into an underfloor deposit at Fremantle Prison has uncovered numerous site formation processes that explain why exceptional preservation was present in cell D40’s deposit. The lack of sunlight, limited moisture, enclosure and building materials all contributed to the extraordinary preservation of a fragile assemblage. The research results indicate that underfloor deposits that share similar site formation processes to cell D40 have significant potential to contain fragile cultural material not preserved in other archaeological deposits. Archaeologists should be encouraged to research this preservation phenomenon in extant buildings containing underfloor deposits to discover more about human behaviour involving fragile materials such as paper and textiles.

Acknowledgement

I acknowledge and pay my respects to the Whadjuk people of the Noongar Nation, the Traditional Owners and Custodians on whose land the Fremantle Prison stands. I thank Fremantle Prison and the Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage for access to the Fremantle Prison’s cultural material. I also thank the Fremantle Prison staff: Daniel Holland, Eleanor Lambert and Wendy Bradshaw; and Dr Shane Burke of the University of Notre Dame; for their time, aid and contribution to this research project. I also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abarb Pest Services 2017 How mice find their way through the tiniest holes. Retrieved 19 November 2020 from <https://abarbpest.com/>.

- Auld, D., T. Ireland and H. Burke 2019 Affective aprons: Object biographies from the Ladies’ College, Royal Derwent Hospital New Norfolk, Tasmania. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 23(2):361–379.

- Beisaw, A. 2009 Constructing institution-specific site formation models. In A. Beisaw and J. Gibbs (eds), The Archaeology of Institutional Life, pp. 33–49. Alabama: University of Alabama Press.

- Bosworth, M. 2004 Convict Fremantle: A Place of Promise and Punishment. Perth: University of Western Australia Press.

- Bryant, L., H. Burke, T. Ireland, L.A. Wallis and C. Wight 2020 Secret and safe: The underlife of concealed objects from the Royal Derwent Hospital, New Norfolk, Tasmania. Journal of Social Archaeology 20(2):166–188.

- Casey, M. 2004 Falling through the cracks: Method and practice at the CSR site, Pyrmont. Australasian Historical Archaeology 22:27–43.

- Craig, F., J. Gallop, A. Jameson, and H. Lotz. 1899 Woodward 1899 Report of the Commission Appointed to Inquire into the Penal System of the Colony. Perth: Richard Pether Government Printer.

- Crook, P. and T. Murray 2006 An Archaeology of Institutional Refuge: The Material Culture of the Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney 1848–1886. Sydney: Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales.

- Crook, P., L. Ellmoos and T. Murray 2003 Assessment of Historical and Archaeological Resources of the Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney. Sydney: Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales.

- Davies, P. 2011 Destitute women and smoking at the Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney, Australia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 15(1):82–101.

- Davies, P. 2013 Clothing and textiles at the Hyde Park Barracks destitute asylum. Sydney, Australia. Post-Medieval Archaeology, 47(1):1–16.

- Davies, P., P. Crook and T. Murray 2013 An Archaeology of Institutional Confinement: The Hyde Park Barracks, 1848–1886. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

- Department of Planning Lands and Heritage 2020 Fremantle Prison: The Convict Establishment. Retrieved 3 April 2020 from <https://fremantleprison.com.au/history-heritage/>.

- Department of Planning Lands and Heritage 2021 Fremantle Prison Archaeological Management Plan 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2020 from <https://fremantleprison.com.au/media/2079/2021-fp_archaeological_management_plan_web2.pdf>.

- Department of Treasury and Finance 2010 Fremantle Prison Conservation Management Plan (revised edition). Unpublished report prepared by Palassis Architects.

- Digital Analysis Corporation 2019 Limestone pH Adjustment Systems. Retrieved 13 November 2020 from <http://digitalanalysis.com/TArticles/Limestone.htm>.

- Dirks, C. 2013 Authority, Acquisition and Adaptation: Nineteenth Century Artefacts of Personal Consumption from the Prisoner Barracks at Port Arthur. Unpublished BLS(Hons) thesis. University of Sydney, Sydney.

- Dixon, G. 2010 Vagabonds and Rogues (Angels and Saints). Unpublished Manuscript.

- Drummond-Wilson, M. 2018 Orphaned Girls and Educated Boys: Class and Gender in the Archaeology of Western Australian Colonial Children's Institutions. Unpublished BA(Hons) thesis. University of Western Australia, Crawley.

- Eureka Consulting 2010 Archaeological Assessment of the Sub-floor Potential, Commissariat Building, Fremantle Prison, Western Australia. Unpublished report prepared for the Fremantle Prison.

- Godfrey, I.M. and D. Gilroy 2017 Conservation and Care of Collections. Perth: Western Australian Museum.

- Government of Western Australia 2009 Fremantle Prison: Building the Establishment. Fremantle Prison. Retrieved 16 March 2020 from <https://fremantleprison.com.au/media/1148/fp-building-the-convict-establishment.pdf>.

- Green, J. 2018 The Children of Ellensbrook: An Archaeological Study of Underfloor Deposits from Ellensbrook Homestead, Southwest Western Australia. Unpublished BA(Hons) thesis. University of Western Australia, Crawley.

- Jackson-Moss, C. 2020 pH Control in the Tannery. Retrieved 6 December 2020 at <https://sites.google.com/site/isttschool/useful-information/ph-control-in-the-tannery>.

- Jones, R.E. 1973 Report of the Royal Commission upon Various Allegations of Assaults on or Brutality to Prisoners in Fremantle Prison and of Discrimination Against Aboriginal or Part-Aboriginal Prisoners therein and upon Certain Other Matters Touching that Prison, its Inmates and Staff. Perth: Government Printer.

- Kerr, J.S. 1998 Fremantle Prison: A Policy for its Conservation. Unpublished Report Prepared for the Department of Contract and Management Services.

- Martin, E. 2019 Untangling Identity: The Archaeology of Smoking and Addiction at the Artillery Drill Hall. Unpublished BA(Hons) thesis. University of Western Australia, Crawley.

- McGivern, J. 1988 Report of the Inquiry into the Causes of the Riot, Fire and Hostage-taking at Fremantle Prison on the 4th and 5th of January 1988 (McGivern Report). Unpublished report prepared for the Honourable J M Benison, M.L.C., Minister for Corrective Services. Perth, Western Australia: Western Australia Government.

- Megahey, N. 2000 A Community Apart: A History of Fremantle Prison, 1898–1991. Unpublished PhD thesis. Murdoch (WA): Murdoch University.

- Mein, E. 2012 Inmate Coping Strategies in Fremantle Prison, Western Australia. Unpublished BA(Hons) thesis. Crawley: University of Western Australia.

- Murphy, K.J. 2003 Under the Boards: The Study of Archaeological Site Formation Processes at the Commissariat Store Site, Brisbane. Unpublished BA(Hons) thesis. The University of Queensland, St Lucia.

- Murphy, K. 2013 Under the boards: Archaeological site formation processes at the Commissariat Store, Brisbane. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 17(3):546–568.

- Nall, R. 2020 Urine pH test level: Purpose, procedure and side effects. Retrieved 23 October 2020 from <https://www.healthline.com/health/urine-ph>.

- Nayton, G. 1998 Report of Archaeological Investigations Associated with the Fremantle Prison Cell Reconstruction Project. Unpublished Report Prepared for the Fremantle Prison.

- Percival, D. 2004 Pattern Analysis of an Office Space: A Behavioural Investigation of Artefacts from the Original Supreme Court Site, Sydney. Unpublished BA(Hons) thesis. Sydney: University of Sydney.

- Porter, W.M. 1980 Soil acidity: Is it a problem in Western Australia? Western Australia Journal of Agriculture 21(4):126–133.

- Robertson, K. and A. Haast 2013 Report on an Archaeological Survey of the Fremantle Prison Women’s Prison. Unpublished report prepared for the Fremantle Prison.

- Schiffer, M.B. 1987 Formation Processes of the Archaeological Record. Utah: University of Utah Press.

- Shaeri, J., M. Yaghoubi, A. Aflaki and A. Habibi 2018 Evaluation of thermal comfort in traditional houses in a tropical climate. Buildings 8(9):126–148.

- Starr, F. 2015 An archaeology of improvisation: Convict artefacts from Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney, 1819-1848. Australasian Historical Archaeology 33(2015):37–54.

- Statham, P. 1981 Why convicts [series of two parts]: Part 1: An economic analysis of colonial attitudes to the introduction of convicts. Part 2: The decision to introduce convicts to Swan River. Studies in Western Australian History 4(1981):1–18.

- Sutton, M. and B.S. Arkush 2014 Archaeological Laboratory Methods: An Introduction (6th edition). Iowa: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company.

- Terra Rosa Consulting 2021 Fremantle Prison Hospital Heritage Assessment and Archaeological Excavations. Unpublished report prepared for the Fremantle Prison.

- Winter, S. 2015 Investigating the Archaeological Potential of Western Australia’s Early Built Environment. Phase one: Peninsula Farm, Maylands; St Bartholomew’s Church, East Perth Cemeteries; Woodbridge House, Guildford. Unpublished report prepared by Winterborne Heritage Consulting.

- Winter, S., J. Green, K. Benfield-Constable, B. Romano and M. Drummond-Wilson 2021 Investigating underfloor and between floor deposits in standing buildings in colonial Australia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 25(1):170–191.

- Winter, S. and B. Romano 2017 Report on Archaeological Work at the Artillery Drill Hall, Fremantle. Unpublished Report Prepared by Winterborne Heritage Consulting.

- Winter, S. and B. Romano 2020 Archaeology, heritage and performance in the Perth popular music scene. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 6(2):322–346.