Wal Ambrose, a quietly influential polymath who inspired Pacific archaeological science for nearly 70 years, died in January, 2024. Affectionately described in his family’s funeral announcement as ‘experimental archaeologist, inventor, artist, photographer, builder, wine connoisseur, and cricket and tennis tragic’, all of these talents and enthusiasms were manifest in his academic life.

Growing up in Auckland, Wal took a Diploma of Fine Arts in painting then a year looking at European art galleries, returning to New Zealand in 1955 at just the right time to join Jack Golson’s burgeoning crew of amateur archaeologists, as university-based, professional archaeology was becoming established. Wal abandoned life as a teacher for a job as technician/photographer/cartographer/illustrator in the Anthropology Department at the University of Auckland. He also enrolled for further study, taking units in anthropology and geology towards a bachelor’s degree, and quickly became an influential participant in the new institutions and research ventures that transformed New Zealand and Pacific archaeology, as an expert excavator, recorder of rock art, writer and editor of academic papers and respected colleague.

In 1963, Wal joined Jack Golson in the Anthropology Department of the Research School of Pacific Studies, the Australian National University (ANU), as research assistant in prehistory, with a brief to establish a laboratory for the conservation of archaeological materials and a photographic studio. Since ANU refused to recognise his Auckland anthropology credits for a science degree, nor his geology credits for an arts degree, he gave up on undergraduate studies ().

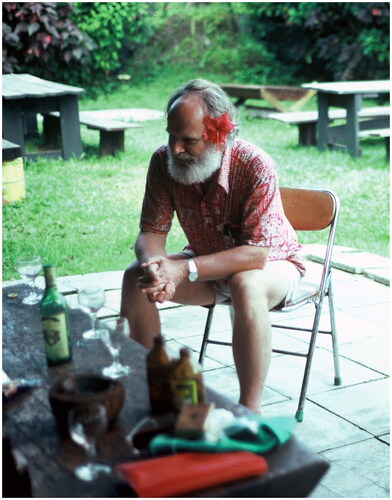

Figure 1. Wal and Janet Ambrose, archaeologists’ lunch, Motutapu Island 1958 (Photograph: Andrew Pawley archive).

Wal, his wife Janet, another recruit from fine arts to archaeology, and their two young children spent two years in London, Wal taking the two-year Diploma of Archaeological Conservation at the Institute of Archaeology. On his return to Canberra, as prehistory was growing rapidly his position was reclassified and he chose to call himself Research Officer in Conservation and Experimental Archaeology. In 1970, as the now-independent Department of Prehistory, Research School of Pacific Studies, settled into the Coombs building, the ground floor of the newly added laboratory wing became Wal’s domain.

Fieldwork with Jack Golson continued, initially in Australia, then increasingly in Papua New Guinea. Wal was from the first involved in research in the Highlands, centred on Kuk Swamp, that established ancient, independent foundations of agriculture in PNG. In 1970, Wal and his family spent six months in Port Moresby, establishing an archaeological lab in the Department of Anthropology, University of Papua New Guinea, and excavating in New Ireland and with Jim Allen at Motupore. At Kuk, he and Winifred Mumford mapped the last phase of prehistoric ditches, Wal using a probe to feel the subsurface texture changes (Golson et al. Citation2017:314–315). Wal had developed this technique in New Zealand, where ‘gumspears’ had much earlier been used to probe for the valuable buried kauri gum. The social life of the Kuk crew-in-residence was improved when Wal and geologist Russell Blong discovered they could buy discount beer in Mt Hagen by forming a club – the Walrus Club.

Wal’s dedication to the practical immediacies of archaeological fieldwork combined with his continuing interests in both science and humanities, circumstances which initially blocked his entry into a normal academic career, gradually became his unique strength, as contemporary archaeology embraced more and more scientific techniques, necessarily outsourced because so few archaeologists fully understood them.

ANU excavations in swamps in both Australia and the New Guinea Highlands produced wet wooden artefacts, including ancient spades from the Kuk site, that required urgent conservation. Wal knew from earlier work in New Zealand and his UK studies that available solutions were unsatisfactory. He developed a new method of impregnation with a stabilising preservative solution and freeze-drying under vacuum, which became widely adopted. The vacuum chamber he built from salvaged parts was too long for his lab, so that the back door was jammed slightly open for decades.

The success of this freeze-drying technique led Wal to look for ways to deal with larger timbers and structures, and thus to experimental work in Antarctica in the 1990s, harnessing the cold, dry atmosphere of the Australian Antarctic base at Davis – one of the driest sites on the world’s driest continent. To get the Antarctic air, often blasting in blizzard conditions, circulating over frozen materials to promote sublimation without introducing snow or ice particles, Wal’s solution was a venturi-type suction system installed above a buried container. The procedure was later applied to the removal of ice and snow from abandoned historic Antarctic buildings, including Mawson’s hut and another at the abandoned Wilkes Station, and their maintenance ice-free. This great improvement over the previous brute-force approach using ice picks and chainsaws has been recognised not only by the Australian authorities, but also by the British Antarctic Survey.

Wal became the leader in the characterisation of obsidian from different Melanesian sources, producing data that demonstrated prehistoric linkages between sites far beyond those recorded ethnographically, illuminating past networks of social interaction in the region. He was the first to demonstrate that the four or five major source areas in Melanesia could be differentiated by density measurement, and went on to develop more refined techniques of non-destructive chemical characterisation of different obsidians (and also pottery), in conjunction with scientists from the then Atomic Energy Commission at Lucas Heights in Sydney. While next-generation researchers have carried on and expanded Wal’s work in this area, many archaeologists world-wide use obsidian sourcing techniques descended from Wal’s original research, and draw upon his collection of reference standards.

Curiosity about the chemistry of obsidian also led him further into obsidian hydration dating, a topic that occupied several decades of his professional research life, running experiments that continued for more than 25 years. Wal noted early that the claim that the procedure was simple, fast and cheap was a false promise. The variables that determine hydration rate needed careful measurement to disentangle their effects. His experimental tanks at standard temperatures allowed measurement of the hydration rates of chemically different samples under realistic conditions. While the data collection and maintenance of these tanks and their heaters was not difficult, persistence over 25 years would have deterred most people. His results have been noticed by scientists whose interests in glass chemistry had no connection to archaeology. Wal also developed methods to cope with the problem of erosion of the surface hydration layer on obsidian artefacts in chemically aggressive soils, measuring uneroded hydration layers in fissures caused by flaking. He showed the results correlate well with dates from independent methods. More recently, he applied himself to the difficulties of optical measurement, using instead digital imaging to enhance the contrast of the hydrated/unhydrated interface.

One largely overlooked problem of chemical dating techniques, such as obsidian hydration and amino acid racemisation, is that of variable ground temperature. This Wal solved by the brilliant invention of hydration cells. These, slightly larger than golf balls, are buried in sites and register temperature by the uptake of ground moisture over set time periods. Sets of these cells – known universally as ‘Wal’s balls’ – buried at different depths allow the calculation of mean and extreme site temperatures. The cells were relatively cheap to produce and could be used in large numbers to measure not only temperature but also humidity and salinity, which allowed their expanded use for other climatological and environmental purposes around the world. The demand was sufficient that Wal patented the idea in several countries and had the cells produced commercially ().

The Melanesian focus of Wal’s obsidian research led to extended fieldwork in the Bismarck Archipelago. In Manus Province, he deconstructed a ‘known’ obsidian source as a series of chemically separable groups, successively erupted and accessed over a span of thousands of years. Excavations of sites buried by ash falls from these eruptions produced informative post-Lapita artefact sequences, including the only archaeologically dated bronze artefact from a Melanesian site (Ambrose Citation1988). Golson (Citation1997:10) remarked that the excavation and discussion of the significance of this unique artefact, as well as the impeccable archaeometric provenancing and description, were all Wal’s work, except for the compositional details provided by X-ray microprobe.

Another area of research in which Wal maintained a lifelong interest was the intricate dentate-stamped decoration of Lapita pottery. He first encountered dentate-stamped sherds from Tonga, recovered in 1957 by Golson: Wal illustrated them in a seminal paper published (in French) 65 years ago (Golson Citation1959:28). Lapita dentate-stamping tools have never been recovered archaeologically, and there has been plenty of speculation about them. Wal proposed that they were made from turtle scute, showing that experimental tools made of this thermoplastic material, with teeth cut before or after bending, reproduced the minute details of Lapita design elements. Using silicone moulds of dentate-stamped sherds, he was also able to demonstrate that alternative decorative techniques such as rouletting could be discounted.

Wal’s curiosity and independence often led him to puncture holes in accepted paradigms. He did so with such tact and humility that the thoroughness of his revisions were sometimes underappreciated. His dismantling of the long-held idea of supposedly ‘clear’ connections between tattooing traditions and Lapita designs is a striking example (Ambrose Citation2012). In his last published paper on Lapita, comprehensive as ever, he argued for the overwhelming prior influence in Oceanic artistic inspiration and expression of basketry and plaiting, rather than, as many had argued, their derivation from Lapita (Ambrose Citation2019).

By 1982, Wal was indistinguishable from any other academic in the ANU Prehistory Department (although achieving more than most: he had also designed and built a family house in Canberra and another at the coast). But he was still officially a Senior Research Officer on the technical pay scale. Even at the top of this scale, he was earning significantly less than his academic colleagues and had no upward pathway. A way around his lack of an undergraduate degree was found by creating a position neither technical nor academic, but attached to the academic pay scale. This unique position, Experimental Archaeologist, was abolished by the administration the day he retired, the loophole closed forever.

In 2006 the ANU conferred on Wallace Ambrose the degree of Doctor of Letters – eight years after his formal retirement from the university. The degree was assessed on 42 submitted papers sorted into four categories. It was difficult to persuade Wal to apply for this, another demonstration of the professional modesty that marked all of his life. His examiners were effusive in their praise, one suggesting that any of the four groups of papers was a sufficient basis to award the degree. They noted all the characteristics of Wal’s professional work – the depth and breadth of his scholarship, spanning science and the humanities, the originality of his ideas, the meticulous nature of his analyses and the flair with which he perceived extensions of his work into other world problems ().

In retirement, Wal continued active engagement with colleagues and students and was an invited speaker at multiple international conferences, not all archaeological. He continued to research and write archaeological articles and was working on a new one when he fell ill late last year.

References

- Ambrose, W.R. 1988 An early bronze artefact from Papua New Guinea. Antiquity 62(236):483–491.

- Ambrose, W. 2012 Oceanic tattooing and the implied Lapita ceramic connection. Journal of Pacific Archaeology 3(1):1–21.

- Ambrose, W. 2019 Plaited textile expression in Lapita ceramic ornamentation. In S. Bedford and M. Spriggs (eds), Debating Lapita: Distribution, Chronology, Society and Subsistence, pp.241–256. Terra Australis 52. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Golson, J. 1959 L’archéologie du Pacific Sud: Résultats et perspectives. Journal de la Société des Océanistes 15:5–54.

- Golson, J. 1997 W.R. Ambrose: An archaeological boffin. Archaeology in Oceania 32(1):4–12.

- Golson, J., T. Denham, P. Hughes, P. Swadling and J. Muke (eds) 2017 Ten Thousand Years of Cultivation at Kuk Swamp in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. Terra Australis 46, Canberra: ANU Press.