ABSTRACT

Depression and anxiety are prevalent in the stroke population and can have a significant impact on the patient and their family’s long-term outcomes, however the screening for these conditions does not meet best practice recommendations. To address this deficit, this study developed “Post-Stroke Mood Assessment Pathways” and embedded them into practice by utilising the PARiHS framework (for the implementation of evidence-based practice), in conjunction with staff training. The study examined the rates of mood screening, clinical interviews, and completion of interventions for stroke patients through a retrospective chart audit (n = 213) one year prior to, and one year post-implementation (n = 238) of the pathways. The data show statistically significant increased documentation around mood screening and clinical interview 95% CI [4.86, 19.88], p < .0012 and specifically, an increase in the number of patients who had a clinical interview following the introduction of the pathways 95% CI [8.05, 19.69], p < .0001.

IMPLICATIONS

Implementing post-stroke mood assessment pathways assists in meeting the National Stroke Foundation Guidelines (2017) by providing clinically validated tools to screen for depression and anxiety in the stroke population.

The social work profession is well positioned to incorporate post-stroke mood screen and assessments into their roles in view of their professional commitment to enhancing social and emotional functioning of patients and families.

中风人群多感到沮丧和焦虑,这对患者及其家庭有着长期影响。相关研究还无法为实践提供最好的建议。为补缺漏,本文采用PARiHS框架(为开展询证实践)并结合人员训练,提出“中风后情绪评估路径”并将其用于实践。本文通过对路径实施一年前及一年后(n=238)的回顾性图表审计(n=213),考察了中风病人的情绪筛查、临床访谈以及干预完成的比率。数据显示,关于情绪筛查及临床访谈的记载在统计上有明显的增加,尤其是引进该路径后做临床访谈的数量有了增加。

In 2017, an estimated 55,000 Australians experienced a new or recurrent stroke and an estimated 470,000 Australians were living with the effects of stroke (Stroke Foundation, Citation2017). The literature demonstrates a significant number of those affected will experience depression, anxiety, or both, at some point after the event (Bennett, Thomas, Austen, Morris, & Lincoln, Citation2006; Kneebone, Baker, & O'Malley, Citation2010; Sagen et al., Citation2009). Depression affects 33% of patients after a stroke and is associated with reduced participation in rehabilitation, longer hospital stays, increased physical impairment, and increased mortality (Hackett, Yapa, Parag, & Anderson, Citation2005; Sagen et al., Citation2009). Anxiety affects 18–25% of stroke patients (Campbell Burton et al., Citation2013; Lincoln et al., Citation2013) and is associated with reduced participation and functional ability, social isolation, and reduced quality of life (Ahlsio, Britton, Murray, & Theorell, Citation1984; Astrom, Citation1996; Donnellan, Hickey, Hevey, & O'Neill, Citation2010). Additionally, changes in the patient’s mood can impact on their social network. Carers cite anxiety and depression in the person with stroke, as among the most stressful difficulties post-stroke (Haley, Roth, Kissela, Perkins, & Howard, Citation2011).

Determinants for depression and anxiety are multifaceted; broadly categorised they consist of (a) the biological outcomes, i.e., the severity of the stroke (Donnellan et al., Citation2010) and aphasia (National Stroke Foundation, Citation2010; Welch, Citation2008), (b) the individual’s psychological status, and (c) the presence, engagement, and capability of the individual’s social support structures (Hilari & Byng, Citation2009; Waldron, Casserly, & O'Sullivan, Citation2013). Depression and anxiety can persist for years, well into the chronic stage of stroke recovery (De Wit et al., Citation2008; Donnellan et al., Citation2010; Lincoln et al., Citation2013). The Australian National Stroke Foundation recognises the impact that depression and anxiety can have on the patient and the support network, and recommends that, “all stroke patients should be screened using a clinically validated tool”, and, that a “diagnosis should only be made following a clinical interview” (National Stroke Foundation, Citation2010, p. 107).

However, assessment can be complicated by the natural responses to the significant changes in the stroke survivor’s life, which can include grief, frustration, anger, and guilt (Welch, Citation2008). The process of undertaking a mood screen and conducting a clinical interview provides the opportunity for clinicians to engage with the affected person and family around mood and to assess if the mood indicates more debilitating mental disorders, such as depression or anxiety, are also present (Bourne, Eckhardt, Sheth, & Eskandar, Citation2012; National Stroke Foundation, Citation2010). The Australian National Stroke Audit – Rehabilitation Services Report of 2015 (Stroke Foundation, Citation2016) indicates that 53% of patients with a stroke who were admitted to an Australian rehabilitation unit were assessed for mood impairment.

Similar to the Australian guidelines, the 2008 United Kingdom (UK) National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke (cited in Gurr, Citation2011) recommends that all patients be screened for depression. However, Gurr (Citation2011) points out that parallel deficits in screening rates are demonstrated in the UK. Gurr (Citation2011) conducted a project to determine whether developing and implementing a post-stroke mood screening pathway improved guideline compliance. The pathway implementation saw 88.9% of patients over a six-month period screened compared with the national median of 67.8%.

The reduced Australian rates of mood screening and clinical interview may be due to reduced implementation of research findings into practice, with a corresponding lower level of knowledge and skills in the clinical setting (Bennett in Welch, Citation2008). Research shows that patients’ physical care needs are routinely prioritised over their psychological care (Adkins, Citation1993; Perry in Welch, Citation2008). In view of Australian compliance rates, the Australian National Stroke Audit – Rehabilitation Services Report (Stroke Foundation, Citation2016, p. 50) recommends a “greater focus on processes to ensure the psychological needs of all patients are assessed and appropriate support is provided during and after inpatient rehabilitation”.

An audit of the clinical records of all stroke patients admitted to the Wide Bay Hospital and Health Service (WBHHS) South between 1 October 2013 and 30 September 2014 demonstrated a 14.5% compliance rate with the Australian National Stroke Foundation’s recommendations that all patients have a mood screen and a clinical interview if low mood is identified (National Stroke Foundation, Citation2010). Hart and Morris (Citation2008) suggest that mood screening compliance may be enhanced by: (a) training to increase knowledge and skills, (b) increasing awareness of guidelines, (c) support from colleagues, and (d) the integration of mood assessment into job roles including routine assessment activities. As such, healthcare social workers are ideally positioned to lead mood screening and “enhance social and emotional functioning through targeted interventions and the mobilisation of services and supports” (Australian Association of Social Workers, Citation2016, p. 3).

A range of theoretical and practice models are available to inform the approach to implementing evidence-based guidelines (Best & Holmes, Citation2010; Cooke, Ariss, Smith, & Read, Citation2015; Dixon-Woods, Citation2014; Evans & Scarborough, Citation2014; Graham et al., Citation2006) with each acknowledging that change to clinical processes and the translation of research to practice is an intricate dynamic. One framework that offers an integrated tool to assess, plan, and evaluate clinical change is the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) model (Kitson, Harvey, & McCormack, Citation1998). The model considers three primary themes: (a) the evidence, (b) the context, and (c) the facilitators of change, and is supported by a body of literature demonstrating its effectiveness across a variety of health settings (Harvey et al., Citation2002; Kitson et al., Citation2008; McCormack et al., Citation2002; Rycroft-Malone, Citation2010; Rycroft-Malone et al., Citation2002; Rycroft-Malone, Harvey, et al., Citation2004; Rycroft-Malone, Seers, et al., Citation2004). In this study, the PARiHS model was chosen as the framework to develop and implement the post-stroke mood assessment pathways specific to the needs of the local population.

Methods

Aim

To develop and implement Post-Stroke Mood Assessment Pathways, which, in conjunction with staff training, would improve the rates of mood screening, clinical interviews and interventions for patients who have had a stroke. Ethical approval was received from a Queensland Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/QPCH/174 date 14.8.2014).

Setting

The study was carried out in the WBHHS South at two hospitals from 1 October 2013 to 30 September 2015. Hospital A has 177 beds, an intensive care unit, and no rehabilitation unit. Hospital B has no intensive care unit and has 44 sub-acute beds (B1) and a dedicated 16-bed rehabilitation unit (B2). Patients are frequently admitted to Hospital A and subsequently transferred to Hospital B for their sub-acute and rehabilitation phase.

Design

The study utilised a pre- and post-test design that consisted of a retrospective audit of patient charts in the 12 months prior to the implementation of the pathways and staff training on 1 October 2014, and 12 months post-implementation. The outcome measures were: (a) the rate of mood screen completions, (b) the rate of clinical interviews, and (c) if low mood was identified, the rate and types of interventions. For the purposes of this research, the authors defined a clinical interview as “documented evidence of a conversation with the patient in regard to their mood”.

Chart Audit Sample and Data Collection Tool

Patients were followed from admission to discharge across the two hospital settings and through community health. Each discharge from a service was examined separately to determine if assessment for low mood was conducted during that episode of care. Community health patients were included in the audit only if they were specifically referred for mood follow-up or intervention. The chart audit included all patients > 18 years old admitted to Hospital A or Hospital A and B within the audit periods with a diagnosis of a stroke categorised under the following ICD 10 codes: a) subarachnoid haemorrhage i60.0–i60.9, (b) intracerebral haemorrhage i61.0–i61.9, (c) other nontraumatic intracranial haemorrhage i62.0–i62.9, (d) cerebral infarction i63.0–i63.9, (e) stroke, not specified as haemorrhage or infarction i64. Charts were excluded if the stroke patient died within four weeks of the stroke (from any cause) or was transferred out of the health service in the four weeks following the stroke.

The audit recorded: patient demographics, length of stay from time of stroke to time of discharge, mood screening assessments, the health professionals who conducted the mood screening(s), the location of the screening, and interventions for low mood.

Development of Mood Assessment Pathways

Search for Screening Tools

There was no standardised methodology within the WBHHS South for mood assessment post-stroke, i.e., no standard screening tool or mood assessment pathway. Paradiso and Robinson (Citation1998) indicate that the optimal means for assessing for depression and anxiety is to apply the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 disorders (SCID). However, this assessment requires specific staff training and the SCID-5-CV generally takes 30–120 min to administer. The SCID-5-RV Core Version takes 45–120 min, and the SCID-4-RV Enhanced Version takes 45–180 min (J. Cha, personal communication, 23 March 2017). The time requirements of this assessment tool posed an obstacle to it being implemented broadly into routine practice across the local health services. Accordingly, alternative means of screening for mood disorders that could be incorporated into a pathway needed to be considered.

A search of electronic databases (PsychoINFO, CINAHL, EMBASE and Medline) from their inception to December 2013 using the keywords: cerebrovascular accident or CVA OR stroke and screen* OR pathway OR tool OR scale OR measure* OR question* AND mood OR depression OR anxiety was undertaken. All searches were limited to English language and human studies. Reference lists of selected articles and reviews were searched (n = 267). The title, abstracts and then full texts were reviewed by two researchers to identify reports with validated post-stroke tools and pathways where mood was assessed in post-stroke patients, and where referral or treatment was identified.

Shortlisting of Screening Tools and Pathways

The clinical utility of both the screening tools and pathways were considered important parameters. They needed to be suitable for use in acute, sub-acute, inpatient rehabilitation and community rehabilitation settings, and be effective and efficient. Tools and pathways that required specific trained personnel or took excessive time were excluded. In addition, tools and pathways that were perceived by the researchers to be confusing were excluded. Screening tools needed to: (a) assess for both depression and anxiety, (b) be used in the presence of cognitive and communication difficulties, (c) have been validated in the stroke population (Bennett et al., Citation2006), and (d) be suitable for all >18 years. A shortlisting conducted by the steering committee produced a total of 12 nonduplicate screening tools. The screening tools identified as being the most valid and efficient were: HADS-A, PHQ-9, SADQ-10 or SADQ-H10 (for hospital patients) and the BOA, the clinical utility of which had been evidenced by Kneebone, Neffgen, and Pettyfer (Citation2012).

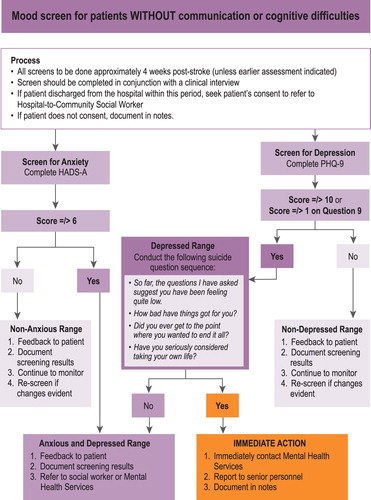

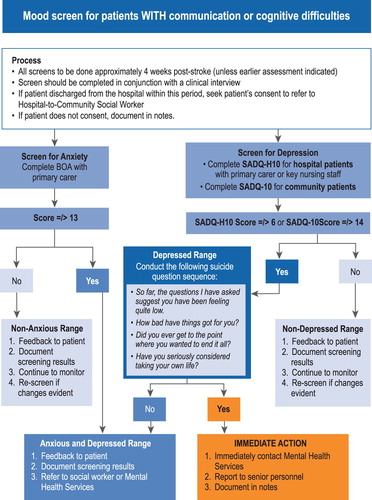

The pathway search produced a total of 18 pathways. However, Kneebone et al. (Citation2012) had already developed pathways incorporating the tools (apart from the SADQ-H10) identified in this study’s search. Kneebone et al.’s (Citation2012) pathways were designed for use in the community and assess for both anxiety and depression in patients with and without communication challenges. The authors adapted these pathways to suit the WBHHS by including the SADQ-H10 (specifically for inpatients) and ensuring the pathway reflected appropriate local referral processes (e.g., refer to Mental Health Services or a social worker). describes the final screening tools that were considered as applicable to the needs of the WBHHS, describes the final screening tools that were not considered applicable, and lists the final pathways that were considered to inform the development of the context specific pathways.

Table 1 Mood Assessment Screening Tools Considered for Inclusion into the Mood Assessment Pathway

Table 2 Mood Assessment Screening Tools Not Considered for Inclusion into the Mood Assessment Pathway

Table 3 Mood Assessment Pathways Considered for Inclusion into the WBHHS Post-stroke Mood Assessment Pathways

As aphasia affects 23–38% of people who experience a stroke (Dickey et al., Citation2010; Engelter et al., Citation2006), the authors followed the work of Kneebone et al. (Citation2012) by developing two tools, one that assessed patients with cognitive and communication difficulties (), and the other that assessed patients without those difficulties ().

Figure 1 Post-stroke mood assessment pathway for patients without communication or cognitive difficulties (Adapted with permission from Kneebone et al., Citation2012)

Figure 2 Post-stroke mood assessment pathway for patients with communication or cognitive difficulties (Adapted with permission from Kneebone et al., Citation2012)

After obtaining and reviewing the literature for this project, a systematic review by Burton and Tyson (Citation2015a) identified a range of alternative mood screening tools that have varying levels of applicability in the context of stroke. The Burton and Tyson review (Citation2015a) further supported the tools Kneebone et al. (Citation2012) used in their pathways, however the BOA was not included in the Burton and Tyson review (Citation2015a). At that time, the BOA was a reasonably new tool and may not have had been clinically verified for the rigour of systematic review analysis. In this project, the BOA was included as it was the only screening tool to assess anxiety in stroke patients with significant cognitive and communication difficulties.

Development and Implementation of Staff Training

The pathways were constructed by authors PMcL and RT and agreed upon by a multidisciplinary team who were identified as having stakeholder involvement in the management and care of stroke patients. The team consisted of speech therapy, occupational therapy, social work, and mental health services, and nursing and medical teams. The multidisciplinary team utilised the PARiHS framework (Rycroft-Malone, Citation2010) to develop a structured approach to the implementation of the mood screening pathways. outlines the specific activities, personnel responsible, and their goals in line with the PARiHS framework.

Table 4 The PARiHS Framework Applied to the Target Groups, the Activities, the Responsibilities and Goals of the Research

Identification of Barriers and Enablers

The key professions identified by the multidisciplinary team as appropriate, responsible, and accountable for the conduct of mood assessments in the context of the health services were: occupational therapy—acute; social work—sub-acute; social work—rehabilitation; and social work—community. All staff in those categories working closely with stroke patients in the service area were included in the staff training (n = four social workers and one occupational therapist). Social workers were deemed to be the preferred staff member to complete the assessments as one of their core roles within the hospital environment is to improve psychosocial outcomes in relation to depression (Australian Association of Social Workers, Citation2016). Due to the staff mix in this regional health service, occupational therapy was chosen to conduct the assessments in the acute context. A pre-training survey of the group’s knowledge and practice elicited responses from three out of five key professionals. Of those responses, all considered mood assessment post-stroke as part of their role, however only one routinely conducted that assessment. Barriers to assessment were identified as: (a) knowledge regarding validated screening tools, (b) time, and (c) environmental issues including privacy on wards.

Staff Training

The purpose of the training was to enable therapists to acquire the knowledge and skills to competently undertake mood screens. The training was delivered over one three-hour period on 1 October 2014 by authors PMcL and RT and involved the use of discussion, a PowerPoint presentation, and role play. The training commenced with a trigger point discussion on: the rates of depression and anxiety in stroke patients, the National Stroke Foundation Guidelines, and an introduction to Pathway A () and Pathway B () and their mood screening tools.

Case studies were then provided and therapists completed role plays assessing each case as per the appropriate pathway. The roles plays were conducted in pairs taking turns to follow the pathways and undertake mood screens. The authors were present to provide assistance and clarification. During the training, and with support from a speech therapist, the authors encouraged the therapists to explore a range of ways to directly communicate with patients who had communication challenges and to use carer-rated scales and tools only when those direct methods were not viable. Following the training, the pathways were provided to the teams and staff responsible for implementing them and were distributed to the ward areas. There was no training follow-up, however, therapists were verbally encouraged to use the pathways and their use was routinely discussed in team meetings.

Procedures

The chart audit was conducted by authors PMcL and RT with the assistance of colleagues who were trained in the use of the data collection tool. Complete verification of data was conducted by authors PMcL, RT, and AR. AR cleansed the data in Excel and imported it into SPSS and conducted the data analysis. The primary analysis was the proportion change using the “N-1” Chi-squared test as recommended by Campbell (Citation2007) and Richardson (Citation2011). The confidence interval was calculated according to the recommended method by Altman, Machin, Bryant, and Gardner (Citation2000).

Findings

The findings from the 2013–2014 and the 2014–2015 survey periods are presented in . shows that n = 213 patient charts were audited in the pre-implementation period, and n = 238 in the post-implementation period (11.7% increase). There was an increase in discharges from Hospital A in the second period (n = 10), however there were a similar number of transfers from Hospital A to Hospital B in the two periods (n = 71 versus n = 74). Sub-acute discharges were similar in the two periods (n = 20 versus n = 19) and there was a small increase in the number of transfers from sub-acute to rehabilitation in the second period (n = 6). There was a larger increase in the number of patients referred for social worker community health follow-up (mood assessment or intervention) post-rehabilitation discharge in the second period compared with the first (n = 10).

Table 5 Chart Audit Pre- and Post-implementation of Post-stroke Mood Assessment Pathways and Staff Training

Table 6 Patient Demographics and Length of Stay by Service

Table 7 Post-stroke Mood Assessment by Service Location and Profession

Table 8 Interventions for Low Mood

Demographic and episode of care information for the two audit periods is reported in . The data show a higher number of males in both periods with a lower mean age on presentation in comparison with females.

The evidence of mood screening is detailed in . The table shows an overall statistically significant increase in documentation around mood screening and clinical interview in the second period compared to the first 95% CI [4.10, 19.38], p < .002, specifically consisting of an increase in the number of patients who had a clinical interview 95% CI [8.05, 19.69], p < .0001. Paradoxically, in the second period there was a significant increase in the number of patients who had no screen or interview in Hospital A (acute service) 95% CI [2.06, 13.7], p < .003 and a significant decrease in the number of patients in Hospital A who had an interview only 95% CI [2.11, 13.6], p < .003. The data show a continued absence of screening and clinical interview in the sub-acute service. Conversely, the rehabilitation service showed a significant increase in patients with a screen and interview 95% CI [32.78, 64.58], p < .0001.

presents the interventions for low mood and shows that in the pre-implementation period, 47% of patients identified with low mood received no intervention, however in the post-implementation period, only one patient identified with low mood did not have an intervention (p = .0002). Compared with the pre-implementation period, the significant interventions for identified low mood in the post-implementation period were: counselling 95% CI [15.82, 69.81], p < .001, mental health 95% CI [−2.1, 50.46], p < .04, and GP follow-up 95% CI [1.11, 50.9], p < .027.

Discussion

The National Stroke Foundation (Citation2010) recommends that following a stroke, all patients receive a mood screen and if low mood is detected, a clinical interview. In this project, the aim was to develop and implement Post-Stroke Mood Assessment Pathways which, in conjunction with staff training, would improve the rates of mood screening, clinical interviews and interventions for patients who have had a stroke. While the findings of the study demonstrate that the implementation of the mood pathways and staff training increased compliance from 14.5% to 26.4%, clearly, there is room for further improvement.

The development and implementation of the pathways was centred around staff training, the planning and conduct of which was based on the PARiHS framework (Kitson et al., Citation1998). This framework proved useful in initially deconstructing and then establishing the roles and responsibilities of the stakeholder team around the elements of the pathway implementation. The pathways did not direct therapists to specific interventions, instead they supported therapists in conducting a solution-focused conversation with patients around what would be helpful to them in gaining control over recovery. This is recognised as an important factor in the psychological care of stroke patients (Welch, Citation2008). Accordingly, during the staff training, therapists were encouraged to work with the patient, family, and multidisciplinary team to create an individual plan to address the patient’s needs.

Lincoln, Kneebone, Macniven, and Morris (Citation2011) indicate that mood assessment should be conducted four weeks post-stroke. In the context of a regional health service with a specific stroke rehabilitation service, this timeline would position patients who have experienced a severe stroke (and who are still in hospital) in the sub-acute or rehabilitation unit of Hospital B. Those patients with a less acute stroke would have been discharged from Hospital A or B and would be within the community.

Overall, the implementation of the pathway and staff training did increase screening, interviews, and interventions for post-stroke patients whose ultimate discharge was from the rehabilitation unit, however there was no improvement in the number of screens and interventions for patients discharged from either the acute or sub-acute setting.

In total there were n = 182 (85%) and n = 175 (73%) missed mood assessment episodes in the two audit periods. In both years, patients discharged home from the acute service were 91% and 98% (respectively) unlikely to receive a mood assessment. This finding suggests that stroke in these patients resulted in relatively minor impairment and they were discharged rapidly (i.e., prior to the four-week post-stoke assessment period). Similarly, the data show that no sub-acute patient (in either period) received a mood assessment. The sub-acute patients were more likely to have experienced a catastrophic stroke and be transferred to a nursing home prior to the four-week post-stoke assessment period. It can be argued that patients with a minor stroke or catastrophic stroke will experience depression and anxiety, however these groups had minimal assessments conducted and thus, the incidence of low mood in these cohorts was impossible to assess. These findings are of concern as there is no evidence to suggest that patients experiencing a minor or a catastrophic stroke don’t require screening—all post-stroke patients are at risk of depression, or depression and anxiety. It is possible that the patients discharged from the acute and sub-acute areas were screened either by their general practitioners or in the nursing home, however this research did not follow up those discharge paths.

The stroke patients most likely to respond to rehabilitation were placed in the rehabilitation unit where there is a larger volume of resources and equally, an extended contact time with specialised social work and stroke care teams. Accordingly, it was the rehabilitation patients who were more likely to have a mood assessment, with the assessment rate rising from 31% in the first year to 88% in the second year. This cohort also had the greatest increase in interventions for low mood.

Limitations

The authors relied on a secondary data source (medical records) to determine whether assessments, clinical interviews and interventions were conducted. There may have been more clinical interviews and interventions around mood that were not documented. However, for those patients where a mood assessment was conducted, the authors noted that the quality of the clinical interview was much richer in the second year, however this was not separated in the research findings. Patients diagnosed with a Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA) were not included, however this may be worth considering in the future.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Depression and anxiety is prevalent in the stroke population and clinicians have a responsibility to ensure they are screening and assessing for mood changes post-stroke. Clinical handover of patients who have not been assessed in the hospital environment is a serious gap in service continuity and places potentially vulnerable patients into the nursing home and community sector without adequate follow-up. Therapists need to allow the stroke survivor time to talk through these feelings during the recovery stage. While it is normal to experience a range of emotions post-stroke, care needs to be taken not to normalise depression and significant feelings of anxiety. Both can become chronic issues if not addressed and affect long-term outcomes for stroke survivors and their family (Lincoln et al., Citation2011).

When implementing these pathways, no added resources were available to increase staffing to ensure all patients were screened according to the pathways. In addition, staff training was conducted once at the implementation of the pathways. This research demonstrates that by incorporating evidence-based mood screening for stroke patients into practice, health care social workers can increase the rate of screening and mood assessments. However, the findings suggest that even when the tools and pathways are present, unless mood assessment is an embedded component of the social worker role, it is unlikely to be conducted.

This research recommends that: (a) staff be specialised in stroke care, (b) mood assessment be embedded into the performance indicators of social workers who work with stroke patients, and (c) ongoing training and support be provided for the clinicians who are conducting the assessments. These recommendations will further the attainment of the National Screening Guidelines (National Stroke Foundation, Citation2010).

Acknowledgements

Wide Bay Hospital and Health Service staff for their support of this research, and Amanda Kratzmann for formatting of Pathways.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Angela Ratsch http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0806-6293

References

- Aben, I., Verhey, F., Lousberg, R., Lodder, J., & Honig, A. (2002). Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, SCL-90, and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale as screening instruments for depression in stroke patients. Psychosomatics, 43(5), 386–393. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.5.386

- Adkins, E. (1993). Quality of life after stroke: Exposing a gap in nursing literature. Rehabilitation Nursing, 18(3), 144–147. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1993.tb00742.x

- Agrell, B., & Dehlin, O. (1989). Comparison of six depression rating scales in geriatric stroke patients. Stroke, 20(9), 1190–1194. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.20.9.1190

- Ahlsio, B., Britton, M., Murray, V., & Theorell, T. (1984). Disablement and quality of life after stroke. Stroke, 15(5), 886–890. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.5.886

- Altman, D., Machin, D., Bryant, T., & Gardner, M. (2013). Statistics with confidence: Confidence intervals and statistical guidelines (2nd ed.). London: John Wiley & Sons.

- Astrom, M. (1996). Generalized anxiety disorder in stroke patients. A 3-year longitudinal study. Stroke, 27(2), 270–275. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.2.270

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2016). Scope of social work practice: Hospital social work. Melbourne: Australian Association of Social Workers.

- Bennett, H., Thomas, S., Austen, R., Morris, A., & Lincoln, N. (2006). Validation of screening measures for assessing mood in stroke patients. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45(Pt 3), 367–376. doi: 10.1348/014466505X58277

- Best, A., & Holmes, B. (2010). Systems thinking, knowledge and action: Towards better models and methods. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 6(2), 145–159. doi: 10.1332/174426410x502284

- Bourne, S., Eckhardt, C., Sheth, S., & Eskandar, E. (2012). Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation for obsessive compulsive disorder: Effects upon cells and circuits. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 6(9), 29, doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00029

- Burton, L., & Tyson, S. (2015a). Screening for cognitive impairment after stroke: A systematic review of psychometric properties and clinical utility. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 47(3), 193–203. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1930

- Burton, L., & Tyson, S. (2015b). Screening for mood disorders after stroke: A systematic review of psychometric properties and clinical utility. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 29–49. doi: 10.1017/s0033291714000336

- Burton, L., Tyson, S., & McGovern, A. (2013). Greater Manchester Assessment of Stroke Rehabilitation (G-MASTER) Toolkit Users’ Manual.

- Campbell, I. (2007). Chi-squared and Fisher-Irwin tests of two-by-two tables with small sample recommendations. Statistics in Medicine, 26(19), 3661–3675. doi: 10.1002/sim.2832

- Campbell Burton, C., Murray, J., Holmes, J., Astin, F., Greenwood, D., & Knapp, P. (2013). Frequency of anxiety after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. International Journal of Stroke, 8(7), 545–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00906.x

- Cinamon, J., Finch, L., Miller, S., Higgins, J., & Mayo, N. (2011). Preliminary evidence for the development of a stroke specific geriatric depression scale. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(2), 188–198. doi: 10.1002/gps.2513

- Clark, L., & Taylor, C. (2010). Mood Pathway-Stroke Services. Bournemouth and Christchurch, England: Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospital NHA Foundation Trusts.

- Cooke, J., Ariss, S., Smith, C., & Read, J. (2015). On-going collaborative priority-setting for research activity: A method of capacity building to reduce the research-practice translational gap. Health Research Policy and Systems, 13. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0014-y

- Dahm, J., Wong, D., & Ponsford, J. (2013). Validity of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in assessing depression and anxiety following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(1), 392–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.011

- De Wit, L., Putman, K., Baert, I., Lincoln, N., Angst, F., Beyens, H., … Feys, H. ((2008)). Anxiety and depression in the first six months after stroke. A longitudinal multicentre study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(24), 1858–1866. doi: 10.1080/09638280701708736

- Dickey, L., Kagan, A., Lindsay, M., Fang, J., Rowland, A., & Black, S. (2010). Incidence and profile of inpatient stroke-induced aphasia in Ontario, Canada. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(2), 196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.09.020

- Dixon-Woods, M. (2014). The problem of context in quality improvement work. In P. Bate, G. Robert, N. Fulop, J. Ovretveit, & M. Dixon-Woods (Eds.), Perspectives on context: A series of short essays considering the role of context in successful quality improvement (pp. 87–101). London: The Health Foundation.

- Donnellan, C., Hickey, A., Hevey, D., & O'Neill, D. (2010). Effect of mood symptoms on recovery one year after stroke. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(12), 1288–1295. doi: 10.1002/gps.2482

- Eccles, A., Morris, R., & Kneebone, I. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Behavioural Outcomes of Anxiety questionnaire in stroke patients with aphasia. Clinical Rehabilitation, 31(3), 369–378. doi: 10.1177/0269215516644311

- Engelter, S., Gostynski, M., Papa, S., Frei, M., Born, C., Ajdacic-Gross, V., … Lyrer, P. (2006). Epidemiology of aphasia attributable to first ischemic stroke: Incidence, severity, fluency, etiology, and thrombolysis. Stroke, 37(6), 1379–1384. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221815.64093.8c

- Evans, S., & Scarborough, H. (2014). Supporting knowledge translation through collaborative translational research initiatives: “Bridging” versus “blurring” boundary spanning approaches in the UK CLAHRC initiative. Social Science and Medicine, 106(April), 119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.025

- Graham, I., Logan, J., Harrison, M., Straus, S., Tetroe, J., & Caswell, W. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47

- Gurr, B. (2011). Stroke mood screening on an inpatient stroke unit. British Journal of Nursing, 20(2), 94–100. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.2.94

- Hackett, M., Yapa, C., Parag, V., & Anderson, C. (2005). Frequency of depression after stroke: A systematic review of observational studies. Stroke, 36(6), 1330–1340. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165928.19135.35

- Haley, W., Roth, D., Kissela, B., Perkins, M., & Howard, G. (2011). Quality of life after stroke: A prospective longitudinal study. Quality of Life Research, 20(6), 799–806. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9810-6

- Hart, S., & Morris, R. (2008). Screening for depression after stroke: An exploration of professionals’ compliance with guidelines. Clinical Rehabilitation, 22(1), 60–70. doi: 10.1177/0269215507079841

- Harvey, G., Loftus-Hills, A., Rycroft-Malone, J., Titchen, A., Kitson, A., McCormack, B., & Seers, K. (2002). Getting evidence into practice: The role and function of facilitation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(6), 577–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02126.x

- Healey, A., Kneebone, I., Carroll, M., & Anderson, S. (2008). A preliminary investigation of the reliability and validity of the Brief Assessment schedule Depression Cards and the Beck Depression Inventory-Fast Screen to screen for depression in older stroke survivors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(5), 531–536. doi: 10.1002/gps.1933

- Hilari, K., & Byng, S. (2009). Health-related quality of life in people with severe aphasia. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 44(2), 193–205. doi: 10.1080/13682820802008820

- Kitson, A., Harvey, G., & McCormack, B. (1998). Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. Quality in Health Care, 7(3), doi: 10.1136/qshc.7.3.149

- Kitson, A., Rycroft-Malone, J., Harvey, G., McCormack, B., Seers, K., & Titchen, A. (2008). Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: Theoretical and practical challenges. Implementation Science, 3(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-1

- Kneebone, I., Baker, J., & O'Malley, H. (2010). Screening for depression after stroke: Developing protocols for the occupational therapist. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(2), 71–75. doi: 10.4276/030802210x12658062793843

- Kneebone, I., Neffgen, L., & Pettyfer, S. (2012). Screening for depression and anxiety after stroke: Developing protocols for use in the community. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(13), 1114–1120. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.636137

- Lincoln, N., Brinkmann, N., Cunningham, S., Dejaeger, E., De Weerdt, W., Jenni, W., … De Wit, L. ((2013)). Anxiety and depression after stroke: A 5 year follow-up. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(2), 140–145. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.691939

- Lincoln, N., Kneebone, I., Macniven, J., & Morris, R. (2011). Psychological management of stroke. Milton, Queensland: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Linley-Adams, B., Morris, R., & Kneebone, I. (2014). The Behavioural Outcomes of Anxiety scale (BOA): A preliminary validation in stroke survivors. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(4), 451–467. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12056

- Lowe, B., Kroenke, K., Herzog, W., & Grafe, K. (2004). Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: Sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Journal of Affective Disorders, 81(1), 61–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8

- McCormack, B., Kitson, A., Harvey, G., Rycroft-Malone, J., Titchen, A., & Seers, K. (2002). Getting evidence into practice: The meaning of “context”. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 38(1), 94–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02150.x

- National Stroke Foundation. (2010). Clinical guidelines for stroke management. Melbourne: Australian Government.

- Ownsworth, T., Little, T., Turner, B., Hawkes, A., & Shum, D. (2008). Assessing emotional status following acquired brain injury: The clinical potential of the depression, anxiety and stress scales. Brain Injury, 22(11), 858–869. doi: 10.1080/02699050802446697

- Paradiso, S., & Robinson, R. (1998). Gender differences in poststroke depression. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 10(1), 41–47. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.1.41

- Richardson, J. (2011). The analysis of 2 × 2 contingency tables—Yet again. Statistics in Medicine, 30(8), 890. doi: 10.1002/sim.4116

- Roger, P., & Johnson-Greene, D. (2009). Comparison of assessment measures for post-stroke depression. Clinical Neuropsychologist, 23(5), 780–793. doi: 10.1080/13854040802691135

- Rycroft-Malone, J. (2010). Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS). In J. Rycroft-Malone, & T. Bucknall (Eds.), Models and frameworks for implementing evidence-based practice: Linking evidence to action (pp. 109–135). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Rycroft-Malone, J., Harvey, G., Seers, K., Kitson, A., McCormack, B., & Titchen, A. (2004). An exploration of the factors that influence the implementation of evidence into practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(8), 913924. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01007.x

- Rycroft-Malone, J., Kitson, A., Harvey, G., McCormack, B., Seers, K., Titchen, A., & Estabrooks, C. (2002). Ingredients for change: Revisiting a conceptual framework. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 11. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.2.174

- Rycroft-Malone, J., Seers, K., Titchen, A., Harvey, G., Kitson, A., & McCormack, B. (2004). What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 47(1), 81–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03068.x

- Sagen, U., Vik, T. G., Moum, T., Morland, T., Finset, A., & Dammen, T. (2009). Screening for anxiety and depression after stroke: Comparison of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 67(4), 325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.03.007

- Sharp, R. (2015). The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Occupational Medicine, 65(4), 340. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv043

- Snaith, R., & Zigmond, A. (1994). The Hospital Anxiey and Depression Scale with the Irritability-depression-anxiety Scale and the Leeds Situational Anxiety Scale. Windsor: Nfer-Nelson.

- Spitzer, R., Kroenke, K., Williams, J., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Stroke Foundation—Australia. (2016). National Stroke Audit Rehabilitation Services Report. Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved from https://informme.org.au/stroke-data/Rehabilitation-audits

- Stroke Foundation—Australia. (2017). Facts and figures about stroke. Retrieved from https://strokefoundation.org.au/About-Stroke/Facts-and-figures-about-stroke.

- Sukantarat, K., Williamson, R., & Brett, S. (2007). Psychological assessment of ICU survivors: A comparison between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress scale. Anaesthesia, 62(3), 239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04948.x

- Waldron, B., Casserly, L., & O'Sullivan, C. (2013). Cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety in adults with acquired brain injury: What works for whom? Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 23(1), 64–101. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2012.724196

- Welch, R. (2008). Considering the psychological effects of stroke. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants, 2(7), 335–338. doi: 10.12968/bjha.2008.2.7.30574