ABSTRACT

Domestic and family violence often results in women and children needing to find alternative safe housing and, on some occasions, this need to relocate may result in homelessness. Public housing and case management packages are scarce for women and children experiencing long-term homelessness caused by domestic and family violence. The research reported here led to the identification of criteria to enable the prioritisation of housing program resources to women and their children escaping domestic and family violence. A systematic search and scoping review were undertaken to identify social and wellbeing criteria to support intake assessment. The intake assessment criteria were then validated using a two-stage modified Delphi process with academic experts and domestic and family violence practitioner experts, expanding notions of “expert” in the use of the Delphi process. Differences between academic and practitioner expert contributions were identified. Specifically, the practitioner experts questioned the premise of the tool and identified the need for both temporal and geographic components to ensure the safety of the housing for the women and children. The innovative inclusion of expert practitioners in this study created buy-in and enabled social work practice expertise to inform the development of a DFV housing assessment tool.

IMPLICATIONS

There is a need for policymakers to gain practitioner buy-in when changing policies and practices. Engaging practitioners within the change processes may include seeking and acknowledging their expert input into the design and development of intake assessment criteria.

There is a dearth of valid and reliable assessment tools in social work. While this article focuses on content validity, testing assessment tools for reliability is also required. There are methodological challenges to be overcome when there are finite service resources and small service user numbers.

Women and children experiencing domestic and family violence (DFV) are often forced to flee their homes for their own safety and the safety of their children. Research has established that women and children can experience prolonged periods of homelessness as a result (Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety, Citation2019; Browne, Citation1993; Zufferey et al., Citation2016). Such homelessness can progress for long periods when women experience substance misuse (Bassuk et al., Citation1996; Kennedy et al., Citation2015; Messing & Thaller, Citation2015; Rothman et al., Citation2018), socioeconomic deprivation (Adams et al., Citation2021; Baker et al., Citation2003; Bassuk et al., Citation1996; Clough et al., Citation2014; Hetling et al., Citation2018; Kennedy et al., Citation2015; Ponic et al., Citation2011; Zufferey et al., Citation2016), mental health concerns (Adams et al., Citation2021; Bassuk et al., Citation1996; Hetling et al., Citation2018; Messing & Thaller, Citation2015; Rothman et al., Citation2018), and other symptoms associated with the trauma of violence and abuse (Baker et al., Citation2003; Bassuk et al., Citation1996; Devaney, Citation2008; Franzway et al., Citation2019; Hetling et al., Citation2018; Ponic et al., Citation2011). Therefore, researchers have argued that safe, affordable, long-term housing is a critical aspect of establishing a life free from abuse (Hetling et al., Citation2018). There can be many barriers for women escaping DFV to find and secure long-term housing for themselves and their children (Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety, Citation2019). Women struggle to navigate pathways to independent living due to multiple moves following crises, eviction threats because of rental problems, navigating agency bureaucracy, and the lack of affordable housing options coupled with their own or their children’s trauma symptoms (Hetling et al., Citation2018).

Not dissimilar to contexts found in the United States of America and United Kingdom (Hetling et al., Citation2018), Australia has experienced a shortage of public housing for decades (Lawson et al., Citation2018). This makes it extremely difficult for women experiencing compounding complex needs associated with DFV to secure and maintain long-term housing. In response, DFV agencies are developing programs aimed at helping women find and keep long-term affordable housing. For example, this article reports on a partnership between the Government of South Australia (SA) Housing Authority and Embolden (peak body for domestic, family, and sexual violence services), who are working to secure long-term public housing for women and children who have experienced DFV.

For the purposes of this article, the term “domestic and family violence (DFV)” is used. “Domestic violence” refers to the acts of violence between people who have, or previously had, an intimate relationship (Cox, Citation2016). Women and their children are the most common victims of DFV (Wendt & Zannettino, Citation2016). First Nations people in Australia may use the term “family violence” rather than “domestic violence”. “Family violence” recognises how individuals, families, and communities have been affected by “the complexities and historical significance of colonisation, oppression, dispossession, disempowerment, poverty, and cultural, social and geographical dislocation” (Wendt et al., Citation2017) p. 3). Both domestic and family violence can include physical and sexual abuse as well as psychological, social, and financial abuse (Cox, Citation2016). Perpetrators use these forms of violence to dominate their partners. Consistent and patterned abuse then allows the perpetrators to control their victims through fear (Wendt et al., Citation2017). Hence this article uses the term “domestic and family violence (DFV)” to be inclusive of both definitions.

Policy and Program Background

The SA Housing Authority experienced a 35% increase in the proportion of women presenting multiple times to the specialist DFV homelessness sector since June 2013 (SAHA, Citation2018). Within this cohort there have been increases in the complexity of the issues that women have presented with, including DFV and a combination of the following: mental illness, physical or intellectual disability or both, chronic illness, substance abuse, and a history of rough sleeping. With finite welfare resources, it is necessary for the SA Housing Authority to direct services to those most in need. This increased complexity, coupled with a change in service demand, resulted in the need to review the intake assessment criteria. The intake assessment criteria had previously been focused on housing need only.

Australian social policy responses have slowly shifted to reflect the value of women and children who have experienced DFV staying within their own home, enabling them to maintain their connections to their community, local schools, health services, and networks (Breckenridge et al., Citation2016). Even though this shift has occurred, a need remains for services that fill the gap for women and children whose only option is to leave the home. The Supportive Housing Program is delivered by the SA Housing Authority and was established in 2010 to provide intensive support and stable housing for people experiencing homelessness, or at risk of homelessness (SA Housing Authority, Citation2018). A review of the program identified the need for change (Democracy Co., Citation2017). The proposed changes centred on how the program could better support DFV survivors and improve the lives of clients of the services such that the “support packages”, are put around the person, not the property and “improve the allocation process” (Democracy Co., Citation2017). The new service model offers both accommodation and ongoing case management for a 12-month period to support the survivor to maintain a tenancy while living independently, safely, and securely. The target population of the service model is women experiencing persistent homelessness due to “intractable” DFV, (terminology used by the SA Housing Authority) with at least 20% of places dedicated for First Nations women, a response to evidenced need. The new service model is guided by the following principles: safety first; housing first, trauma informed, assertive and persistent, culturally informed, child focused, duration of need, client engagement in support services is voluntary, choice over housing, and support (SA Housing Authority, Citation2018).

This article presents research contracted by the SA Housing Authority to: modify the intake assessment criteria for long-term housing to ensure that the complex social and wellbeing needs of women and their children who have experienced DFV-related housing instability were considered; and to ensure that the allocation process for the new service model combining housing and case management prioritised people with the highest levels of risk, vulnerability, and need. A review of the literature by SA Housing Authority staff and researchers could not identify a suitable assessment tool that met the needs of the program. The aim of this research was to identify, develop, and validate social and wellbeing criteria for the assessment of DFV-related housing instability to inform intake assessment to the supported housing program. The research question guiding the study was what evidence-based criteria can be used to assess survivors of DFV and their children’s housing need?

Method

Research Design

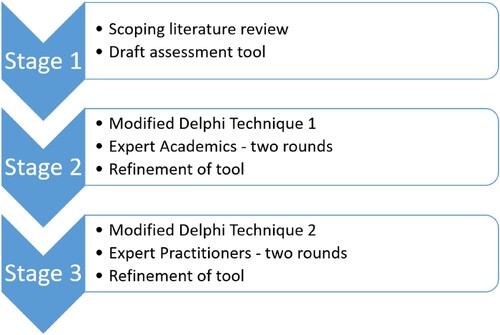

A three-stage method () was used to develop and refine the identification of the social and wellbeing criteria of DFV-related housing instability to inform the allocation of housing services. The first stage involved a systematic search and scoping review of relevant literature to identify the criteria for DFV-related housing need. The second and third stages involved a modified Delphi process with academic and practitioner experts to validate the content of the DFV-related social and wellbeing criteria.

Fourteen documents were retrieved from the Google search and retained in the review. These items ranged in nature from assessment tools for DFV or homelessness (Backhouse & Toivonen, Citation2018; NSW Government, Citation2015; Toivonen & Backhouse, Citation2018; Westside Housing Association Inc., Citation2015) through to Australian and State government policy and practice principles (ACT Government, Citation2016; Government of Western Australia, Citation2013; NSW Government, Citation2014; Queensland Government, Citationn.d.; SA Department for Communities and Social Inclusion, Citation2017; Victoria Government, Citation2013, Citation2018; Victoria State Government, Citation2017), and reports and program evaluations (Keast et al., Citation2011; Spinney & Blandy, Citation2011). Twelve peer-reviewed articles were retained and the first author undertook a thematic analysis where social and wellbeing criteria were identified (Box S1, online supplement) and formed the basis of the development of the draft intake assessment criteria.

Participants

Academic Experts and Practitioner Experts

Academics with expertise in DFV or Housing or both from Australian universities and expert DFV practitioners across South Australia were invited to participate in the Delphi process. Two Delphi rounds were conducted with both expert groups. As the academic experts were interstate, they were contacted via email independently (initial invitation to be involved and subsequent emails with the tool and evidence document attached). The expert academics were not aware of the feedback or correspondence with the other academics until they saw the revised content of the tool. The academic experts were selected based on their expertise in Australia on either DFV or Housing. The authors approached the five academic experts and invited them to be involved in the study; three agreed to participate. All correspondence was via email to recruit and engage in identification and selection of criteria.

Two focus groups were held with practitioner experts. Both focus groups were attended by 14 participants. Of these participants, seven attended both focus groups, so there was a sample of n = 21 unique participants across both focus groups. The practitioner experts were invited to be involved in a focus group Delphi process whereby the tool and evidence document were distributed prior to the group meeting and feedback was sought during the focus group. On the advice of Embolden, a focus group was used to collect practitioner Delphi feedback. Embolden supported the recruitment process and DFV practitioners from across South Australia (metropolitan and rural) regions were invited to participate, timed to coincide with a regular meeting.

Measures

Stage 1: Scoping Review to Identify the Social and Wellbeing Criteria

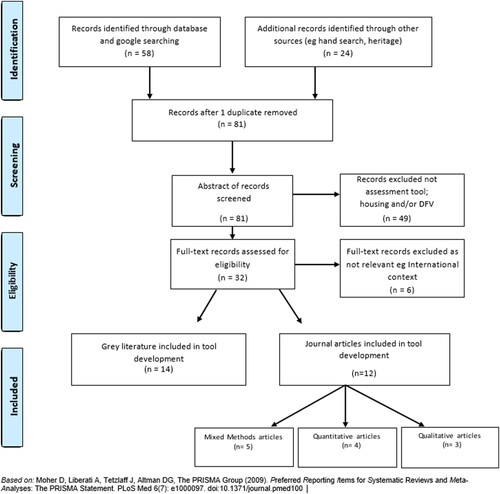

A systematic search and scoping review were conducted to identify reports and studies using PICo (Population—women and children experiencing DFV, Intervention—intake assessment tool, and Context—public housing). Scoping reviews are used to map the conceptual frameworks, concepts, methods, measures, and tools that underpin a research area and to identify potential strengths and gaps in the literature (Peters et al., Citation2019). The systematic search was conducted by the research librarian during December 2018 and January 2019 and updated in January 2022. Author 1 and the research librarian identified the following databases and online search for grey literature: Proquest, Scopus, CINAHL, Expanded Academic Index ASP, Informit, OvidSP, and Google Scholar. To access available reports and tools in the grey literature, the research librarian advised that searches using Google were limited to PDFs on websites ending with “.gov”, “.org”, and “.edu”. The first three pages of items found were scanned and relevant items included. A hand-search for specific known relevant articles was also undertaken. The search strategy is represented in a PRISMA (Moher et al., Citation2009) diagram in . No systematic reviews on assessment tools of housing need for women and children escaping domestic and family violence were found.

Stages 2 and 3: Modified Delphi Technique

Content validity is a measure of how well the items measure the behaviour for which it is intended (Streiner & Norman, Citation1989). A two-staged modified Delphi Technique was used to validate the content of the social and wellbeing criteria identified within the literature through building consensus (Hsu & Sandford, Citation2007). A Delphi Technique uses independent expert opinion on a specialised area of knowledge to review and comment (Biondo et al., Citation2008).

Procedure

The academic experts were sent the first draft of the social and wellbeing criteria, identified within the literature review, and a supporting document linking the evidence sources for each of the criteria. Academic experts were asked to review the criteria and provide comments on gaps, current inclusions, and the need for any exclusions, providing references in support of items recommended to fill gaps or for inclusion. Three of the five expert academics who were approached responded. They were all DFV experts. All were from Australia: two from Victoria and one from Queensland. Author 2 attended the focus group with the practitioner experts on two occasions where the subsequent focus group reviewed the changes from the first focus group. The focus groups were held ten weeks apart and participants consented to be involved on both occasions. The practitioner experts were asked to comment on the content and consider gaps and duplication of the identified criteria. The focus groups were voice recorded and transcribed. A thematic analysis was undertaken on the responses from both the academic and practitioner experts.

Data Analysis

The academic and practitioner expert responses from rounds 1 and 2 Delphi are summarised in Box S2, online supplement. All modifications from the round 1 were made and the documents were re-sent to the academic experts for round 2, which included additional feedback and approval. There was duplication between academics in Delphi round 1 on the demographics and the types of violence. No items were suggested to be removed. Both rounds of the focus groups with practitioner experts were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed. A thematic analysis was undertaken, and themes summarised in Box S3, online supplement. At each stage and round of the Delphi process the feedback was used to develop and refine the criteria. The criteria included demographic items and three sections as follows: (i) DFV (which included the First Nations women section and current safety risk assessment); (ii) current housing; and (iii) disabling health and social criteria (Box S4, online supplement).

Ethics approvals were sought and received from the relevant University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project Number 8184).

Results

This section presents the results from the thematic analysis of the changes proposed within the Delphi process: first the academics’ then the practitioner experts’ suggestions. The results section concludes with a reflection on the differences between the two expert participant groups.

Academic Experts

The following three themes were identified: additional criteria, refining language, and implementation challenges.

Additional Criteria

Several items were added as risk factors to the demographics of the woman, such as age, including both young and old (Australian Association of Gerontology, Citation2018; McFerran, Citation2010), immigration status (National Advocacy Group on Women on Temporary Visas Experiencing Violence, Citation2018; Thurston et al., Citation2013), and Indigeneity (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2018). Other social and health additions included the woman and her children’s health, her disability or mental health status or both, recent release from prison (Engleton et al., Citation2021), and employment status. Several items were added for housing, including supports to transition to private rental, previous history of rental (and arrears), and legal and financial interruptions resulting from violence. The area of greatest duplication from the academic experts’ viewpoints, which is potentially reflective of their DFV expertise, was regarding the feedback on the types of violence. Additional criteria included separated, strangulation, threats to life, perpetrators’ access to weapons, stalking, and technology abuse. In the second Delphi round, one academic expert suggested the addition of gambling as a risk factor for the woman (Dowling et al., Citation2014; Holdsworth et al., Citation2011).

Refining Language

Two academic experts commented on the language used within the draft criteria. One academic expert suggested removing language that may inadvertently blame the woman: for example, removing references to “cyclical”. Another academic expert suggested the removal of the example for the criterion “ongoing contact with the perpetrator”: removing “e.g., father of children”.

Implementation Challenges

One expert academic at the conclusion of the second round raised concerns about the potential reporting burden for practitioners in implementing lengthy intake assessment criteria.

Practitioner Experts

From the analysis of the Delphi focus groups, the following themes were identified: refining language and ideology, adding and removing criteria, and implementation challenges. Practitioner expert themes were similar but not identical to the academic expert themes.

Refining Language and Ideology

The practitioner experts were ideologically uncomfortable with the use of the term “intractable” DFV. The following comment was made:

I'm just trying to think how can you operationalise what they mean by “intractable” because we will always … this group and I agree, domestic violence is domestic violence and it’s very hard to start saying whose worse off because it’s just shit across the board, but in terms of a program that’s trying to prioritise particular vulnerability, how do we operationalise intractable is kind of the question and discussion of “multiple episodes”. (FG Coalition, June 2019)

Adding and Removing Criteria

Several clarifications in relation to the criteria were provided by practitioners: in particular, demographics regarding immigration status. Practitioners sought clarification and queried how to operationalise terms such as “weapons” and use of the term “multiple episodes”. A practitioner stated “anything could be a weapon—it could be a pen … or their hands” (FG Coalition, June 2019). Practitioners suggested removing the criteria that assessed the support received by the woman (Baker et al., Citation2003), stating “you wouldn’t be nominating someone if they didn’t need the support” (FG Coalition, June 2019). This statement from the practitioner experts suggested that all women using their services required support. Temporal and geographical location issues were raised by the practitioner experts: for example, the need to include a date upon which the allocation was conducted as women’s lives change very quickly, as can their DFV risk. The issues of location were critical inclusions so that informed decisions could be made about the location of the housing being offered regarding proximal location to the children’s school or childcare, potential medical appointments, and the ability to maintain stability and community networks while at the same time ensuring a distal location from the perpetrator. As a result of these suggestions, suburb locations were added to the criteria.

The practitioner experts suggested the need for the inclusion of specific items for First Nations women, to recognise their unique disadvantage and their unique experience of family violence. As a result, six evidence-informed criteria (Wendt et al., Citation2014) were added and reviewed by a First Nations DFV practitioner prior to returning to the second round of practitioner expert review and comment. The second Delphi focus group with practitioner experts was held approximately ten weeks after the first round to review the modifications to the identified criteria and where it was possible provide responses to questions raised in the first focus group. The practitioner experts reviewed the changes to the culturally and linguistically diverse items and First Nations items, and reviewed the content that related to children or family health. Two items were added: one regarding women or children’s engagement with the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) as a support for making modifications to housing properties; the second regarding whether the woman had recent (in last 6 months) contact with the Family Safety Referral, as this would demonstrate imminence of danger.

Implementation Challenges

Process and practice issues were raised by practitioners in relation to the application and use of the criteria for intake assessment, such as whether a letter of support was still required and who conducts the allocations (DFV workers or Housing workers or both). Other implementation and operational questions included whether women on temporary visas were eligible for services from the Supported Housing Program and whether DFV services were the only referral source to the new service model of the Supported Housing Program.

Discussion

This research has occurred at the intersection of practice-based evidence (researchers working with practitioners to develop research evidence) and evidence-based practice (practitioners using research evidence to inform their practice), transgressing the research–practice divide (Fox, Citation2003). Researchers and practitioners came together to identify and develop criteria to inform transparent, accountable, and consistent allocation of housing services to women and children escaping DFV who are vulnerable and at risk.

The review of the literature did not locate any housing intake assessment tools with a specific focus on the housing needs of women and children fleeing DFV. This study worked to remedy this gap. The literature review included studies identifying the predictors of housing instability for this population (Box S1, online supplement). It is evident from this information that the predictors remained variable across studies: for example, culture was not a predictor in some studies (Adams et al., Citation2021), but was found to be a predictor in other studies (Kennedy et al., Citation2015). Similarly, severity of violence was not a predictor in some studies (Adams et al., Citation2021) and yet was identified as a predictor in other studies (Baker et al., Citation2003; Bassuk et al., Citation1996; Hetling et al., Citation2018; Ponic et al., Citation2011). The continual building of an evidence-base was important; however, the differences in outcomes between studies demonstrated a shifting evidence-base, making the practice of evidence-informed decision-making difficult. However, practitioners need tools that can inform or justify their treatment selections or allocation of finite services to one client rather than another (Lewis & Roberts, Citation2001). Therefore, this study has relevance for DFV practitioners and housing authorities when making decisions about the allocation of housing services for women and children fleeing DFV.

The use of a modified Delphi technique to build consensus on the criteria using both academic and practitioner experts provided an innovative method combining the strengths of “evidence-based practice” and also “practice-based evidence” from academic and practitioner knowledge and expertise. The researchers and academics were able to identify the criteria utilising the research from the literature and then engage with practitioners regarding their application in the practice setting (Jaynes, Citation2014). The benefits of engaging practitioners in the research process are multiple. Managers within the service were involved in the design and development of the research, building their research capacity (Donley & Moon, Citation2021) and practitioners were in the unique position of challenging existing research and practices and promoting change (Donley & Moon, Citation2021; Orme & Powell, Citation2007). The inclusion of the practitioner experts was critical for the practice-based application of the criteria for the allocation of services such as DFV time and location. Academic experts identified gaps in the criteria, such as age, mental health, immigration status, and gambling. Academic and practitioner experts both contributed knowledge on the types of DFV, such as strangulation, threats to life, use of technology, stalking, and the perpetrator’s potential position as carer. The inclusion of practice knowledge in the identification of criteria enabled insights to come to the fore, such as the importance of temporality and spatiality, criteria that have not been captured in the evidence-based literature. The practitioner experts also contributed nuanced knowledge regarding diversity and women and children’s experience of DFV, particularly as it relates to First Nations women and refugee and migrant women. Of striking difference in the identification of the criteria was the nature of the suggested changes by the academic and practitioner experts. The practitioner inclusions of the temporal (time) and spatial (geographical) experiences of violence and housing instability was critical to ensure the ongoing safety of the women and children. Further, this involvement was important to ensure the safety of the woman by focusing on the maximum distance from the perpetrator. Additionally, practitioner involvement focused on the woman’s and children’s wellbeing by considering the proximity to her social networks, community, childcare, schools, and support services. Practitioners were able to envisage criteria from the perspective of women living their everyday lives navigating domains of social connection and wellbeing (Goodman et al., Citation2016). The practitioner expertise contributed to gaining support for the rollout of the program and investment or buy-in of the program and, as a result, bringing about change to policy and decision-making processes. Practice-based research enabled practitioners to partner with the researchers and policymakers within the South Australian Housing Authority, which realigned traditional power imbalances through bringing the information needs of practitioners to the fore in the identification of the criteria (Jaynes, Citation2014).

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the study were the method and the inclusion of a literature review identifying and mining the best available evidence to inform the development of the tool. This evidence and the Delphi Technique have allowed both contemporary academic and practitioner intelligence to validate the content of the tool. In addition, given that the “target” of one fifth of the program participants should be First Nations women was met, the inclusion of items in the assessment tool that support the unique experience of DFV for First Nations women and children is another clear strength of the study.

Although academic experts raised the length of time needed for implementing the tool as a possible burden for practitioners (thus a potential limitation of the study), the practitioners themselves, who would be implementing the tool in practice, did not mentioned this as a limitation. This could be a result of being involved in the development of this tool and being aware of the relevance of the questions to the allocation process or being aware of the inadequacies of the previous allocation or just having not applied the criteria in practice yet. The qualitative study methods used in the identification and development of the criteria was conducted with rigor. A limitation of the use of the criteria is that no quantitative reliability or construct validity testing has been undertaken, which means that only limited conclusions can be drawn when implementing the criteria. Funding limitations precluded such testing and the conducting of a factor analysis was also precluded as a result of the anticipated small sample size. This is common in the welfare sector, where the small sample sizes involved (number of program packages available) make it difficult to undertake rigorous quantitative testing. An added complication is the sensitivity of the information being collected and the burden on both the women and DFV practitioners involved in reliability testing. Additional limitations include the lack of inclusion of survivor voices in the identification of the criteria; the heteronormative nature of the identification of the criteria, and when men are the victims of DFV.

Conclusion

There is a dearth of published evidence-based assessments to determine housing need for women and children escaping domestic and family violence. In this study both academics and practitioners made critical contributions to the identification of housing assessment criteria through the use of Delphi methods. Both academic and practitioner experts provided content on the types of violence and controlling behaviours used by the perpetrators. Academic experts identified gaps in content and areas of risk and vulnerability, while practitioner experts provided content that was grounded in the everyday geographic and temporal experience of DFV for women and children. This study demonstrated that researchers require innovative methods when working at the intersection of evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence. The methods used built both evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence as well as a shared vision and commitment to the implementation of the assessment tool.

Box S1

Download MS Word (46 KB)Acknowledgements

This article is associated with the study Development of an intake assessment for the Domestic and Family Violence Supported Housing Program, funded by the SA Housing Authority. The views expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the South Australian Government. The authors wish to thank the SA Housing Authority, EMBOLDEN, and Social Work Innovation Research Living Space Research Centre, Flinders University.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACT Government. (2016). ACT government response to family violence.

- Adams, E. N., Clark, H. M., Galano, M. M., Stein, S. F., Grogan-Kaylor, A., & Graham-Bermann, S. (2021). Predictors of housing instability in women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(7-8), 3459–3481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518777001

- Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety. (2019). Domestic and family violence, housing insecurity and homelessness: Research synthesis (ANROWS Insights, Issue). https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2019-03/apo-nid226421.pdf

- Australian Association of Gerontology. (2018). Background paper. Older women experiencing, or at risk of, homelessness. Australian Association of Gerontology.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Information paper-A statistical definition of homelessness. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/mf/4922.0

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2016). Domestic and family violence and homelessness 2011-12 to 2013-14. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/domestic-family-violence-homelessness-2011-12-to-2013-14/contents/the-intersection-of-domestic-violence-and-homelessness

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2018). Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018. (Cat. no. FDV 2.).

- Backhouse, C., & Toivonen, C. (2018). National risk assessment principles for domestic and family violence: Companion resource. A summary of the evidence-base supporting the development and implementation of the national risk assessment principles for domestic and family violence (ANROWS Insights, Issue).

- Baker, C., Cook, S., & Norris, F. (2003). Domestic violence and housing problems. Violence Against Women, 9(7), 754–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801203009007002

- Bassuk, E., Weinreb, L., Buckner, J., Browne, A., Salomon, A., & Bassuk, S. (1996). The characteristics and needs of sheltered homeless and low-income housed mothers. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 276(8), 640–646. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1996.03540080062031

- Biondo, P. D., Nekolaichuk, C. L., Stiles, C., Fainsangier, R., & Hangen, N. A. (2008). Applying the Delphi process to palliative care tool development: Lessons learned. Supportive Care in Cancer, 16(8), 935–942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0348-2

- Breckenridge, J., Chung, D., Spinney, A., & Zufferey, C. (2016). National mapping and meta-evaluation outlining key features of effective ‘safe at home’ programs that enhance safety and prevent homelessness for women and their chilren experiencing domestic and family violence.

- Browne, A. (1993). Family violence and homelessness: The relevance of trauma histories in the lives of homeless women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 63(3), https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079444

- Clough, A., Draughon, J., Njie-Carr, V., Rollins, C., & Glass, N. (2014). ‘‘Having housing made everything else possible”: Affordable, safe and stable housing for women survivors of violence. Qualitative Social Work, 13(5), 671–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325013503003

- Cox, P. (2016). Violence against women: Additional analysis of the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ personal safety survey 2012.

- Cunningham, J., & Paradies, Y. (2013). Patterns and correlates of self-reported racial discrimination among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults, 2008-09: Analysis of national survey data. International Journal of Equity in Health, 12(47).

- Democracy Co. (2017). Consultation report: Supportive housing program review.

- Devaney, J. (2008). Chronic child abuse and domestic violence: Children and families with long-term and complex needs. Child & Family Social Work, 13(4), 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00559.x

- Donley, E., & Moon, F. (2021). Building social work research capacity in a busy metropolitan hospital. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(1), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731520961464

- Douglas, H., & Fitzgerald, R. (2014). Strangulation, domestic violence and the legal response. Sydney Law Review, 36(2), 231–254.

- Dowling, N. A., Jackson, A. C., Suomi, A., Lavis, T., Thomas, S. A., Patford, J., Harvey, P., Battersby, M., Koziol-McLain, J., Abbott, M., & Bellringer, M. E. (2014). Problem gambling and family violence: Prevalence and patterns in treatment-seekers. Addictive Behaviors, 39(12), 1713–1717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.006

- Engleton, J., Sullivan, C., & Hamdan, N. (2021). Brief note: Exploratory examination of how race and criminal record relate to housing instability among domestic violence survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 088626052110426–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211042626

- Fox, N. J. (2003). Practice-based evidence. Sociology, 37(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038503037001388

- Franzway, S., Moulding, N., Wendt, S., Zufferey, C., & Chung, D. (2019). The sexual politics of gendered violence and women's citizenship. Policy Press.

- Glass, N., Laughon, K., Campell, J., Block, C., Hanson, G., Sharps, P. W., & Taliaferro, E. (2008). Non-fatal strangulation is an important risk factor for homicide of women. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 35(3), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.02.065

- Goodman, L., Thomas, K., Cattaneo, L., Heimel, D., Woulfe, J., & Chong, S. (2016). Survivor-Defined practice in domestic violence work. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(1), 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514555131

- Government of Western Australia. (2013). Responding to high risk cases of family and domestic violence: Guidelines for multi-agency case management.

- Hageman, T. O. N., Langenderfer-Magruder, L., Greene, T., Williams, J. H., St. Mary, J., McDonald, S. E., & Ascione, F. R. (2018). Intimate partner violence survivors and pets: Exploring practitioners’ experiences in addressing client needs. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 99(2), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044389418767836

- Hetling, A., Dunford, A., Lin, S., & Michaelis, E. (2018). Long-term housing and intimate partner violence. Affilia, 33(4), 526–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109918778064

- Holdsworth, L., Tiyce, M., & Hing, N. (2011, November). Exploring the relationship between problem gambling and homelessness: Becoming and being homeless. Gambling Research: Journal of the National Association for Gambling Studies (Australia), 23(2), 39–54. https://search.informit.com.au/fullText;dn=659354563147675;res=IELHSS

- Hsu, C.-C., & Sandford, B. A. (2007, August). The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 12(10).

- Jaynes, S. (2014). Using principles of practice-based research to teach evidence-based practice in social work. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 11(1-2), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2013.850327

- Keast, R., Waterhouse, J., Pickernell, D., & Brown, K. (2011). Ready or not? Considerations for the Qld housing service system research report: Housing readiness.

- Kennedy, A., Bybee, D., & Greeson, M. (2015). Intimate partner violence and homelessness as mediators of the effects of cumulative childhood victimization clusters on adolescent mothers’ depression symptoms. Journal of Family Violence, 30(5), 579–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9689-7

- Lawson, J., Pawson, H., Troy, L., van den Nouwelant, R., & Hamilton, C. (2018). Social housing as infrastructure: an investment pathway.

- Lea, M. (2015). Women with a disability and domestic and family violence: A guide for policy and practice. https://pwd.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/1.-A-Guide-for-Policy-and-Practice.pdf

- Lewis, S., & Roberts, A. R. (2001). Crisis assessment tools: The good, the bad, and the available. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 1(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/1.1.17

- McFerran, L. (2010). It could be you: Female, single, older and homeless (August).

- Messing, T., & Thaller, J. (2015). Intimate partner violence risk assessment: A primer for social workers. British Journal of Social Work, 1804–1820. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu012

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D., & The Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- National Advocacy Group on Women on Temporary Visas Experiencing Violence. (2018). Path to nowhere: Women on temporary visas experiencing violence and their children.

- NSW Government. (2014). Specialist homelessness services–practice guidelines.

- NSW Government. (2015). Specialist homelessness services initial assessment form.

- Orme, J., & Powell, J. (2007). Building research capacity in social work: Process and issues. British Journal of Social Work, 38(5), https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm122

- Osmond, J., & Tilbury, C. (2012). Permanency planning concepts. Children Australia, 37(3), 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2012.28

- Parker, R., Rescorla, L., Finkelstein, J., Barnes, N., Holmes, J., & Stolley, P. (1991). A survey of the health of homeless children in Philadelphia shelters. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 145(5), 520–526. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160050046011

- Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Baldini Soares, C., Khalil, H., & Parker, D. (2019). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris, & Z. Munn (Eds.), Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer's manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/

- Ponic, P., Varcoe, C., Davies, L., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wuest, J., & Hammerton, J. (2011). Leaving ≠ moving: Housing patterns of women who have left an abusive partner. Violence Against Women, 17(12), 1576–1600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801211436163

- Queensland Government. (n.d.). Practice guidelines: Queensland homelessness information platform.

- Ringland, C. (2018). The domestic violence safety assessment tool (DVSAT) and intimate partner repeat victimisation (Crime and Justice Bulletin 213). https://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Documents/CJB/2018-Report-Domestic-Violence-Safety-Assessment-Tool-cjb213.pdf

- Rothman, E., Stone, R., & Bagley, S. (2018). Rhode Island domestic violence shelter policies, practices, and experiences pertaining to survivors with opioid use disorder: Results of a qualitative study. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 12, 117822181881289–117822181881287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221818812895

- SA Department for Communities and Social Inclusion. (2017). Practice framework: Housing SA service delivery guide.

- SA Housing Authority. (2018). Domestic and family violence Supportive Housing Program: New service model. SA Housing Authority.

- Sharp-Jeffs, N., Kelly, L., & Klein, R. (2018). Long journeys toward freedom: The relationship between coercive control and space for action– measurement and emerging evidence.

- Spinney, A., & Blandy, S. (2011). Homelessness prevention for women and children who have experienced domestic and family violence: Innovations in policy and practice (AHURI Positioning Paper No. 140).

- Streiner, D., & Norman, G. (1989). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. Oxford University Press.

- Thurston, W. E., Roy, A., Clow, B., Este, D., Gordey, T., Haworth-Brockman, M., McCoy, L., Beck, R. R., Saulnier, C., & Carruthers, L. (2013). Pathways into and out of homelessness: Domestic violence and housing security for immigrant women. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 11(3), 278–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2013.801734

- Toivonen, C., & Backhouse, C. (2018). National risk assessment principles for domestic and family violence (ANROWS Insights, Issue).

- Victoria Government. (2013). Assessing children and young people–experiencing family violence: A practice guide for family violence practitioners.

- Victoria Government. (2018). Family violence risk assessment and risk management: Policy and practice (Consultation draft).

- Victoria State Government. (2017). Responding to family violence capability framework.

- Wendt, S., Chung, D., Elder, A., Hendrick, A., & Hartwig, A. (2017). Seeking help for domestic and family violence: Exploring regional, rural, and remote women’s coping experiences: Final report.

- Wendt, S., & Fraser, H. (2019). Promoting gender responsive support for women inmates: A case study from inside a prison. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 15(2), 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-03-2018-0011

- Wendt, S., Tedmanson, D., Moulding, N., Buchanan, F., & Elder, A. (2014). Working from the strength of connection: Responding to family violence in the northern Adelaide Medicare local region.

- Wendt, S., & Zannettino, L. (2016). Domestic violence in diverse contexts: A re-examination of gender. Routledge.

- Westside Housing Association Inc. (2015). Client risk assessment form: Tenancy management.

- Zufferey, C., Chung, D., Franzway, S., Wendt, S., & Moulding, N. (2016). Intimate partner violence and housing. Affilia, 31(4), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109915626213