ABSTRACT

Large numbers of children in Australia are in long-term out-of-home care (OOHC). Legal frameworks available for their care are long-term foster care, guardianship, and plenary adoption. Views of individuals with OOHC or adoption experience on these legal frameworks were explored via an online survey. A legal framework called simple adoption, which makes children legal members of adoptive families without legally excising them from birth families, was also considered. The respondents (N = 1019) evaluated aspects of these frameworks as strengths or weaknesses from which scores were calculated. Overall, simple adoption had the highest strength score, followed by plenary adoption, guardianship, and long-term foster care. The highest weakness score was for long-term foster care, followed by guardianship, plenary adoption, and simple adoption. That simple adoption enabled enduring familial relationships between children and their adoptive families while retaining legal identity and legal connection with birth families contributed to its favourable evaluation.

IMPLICATIONS

The legal severance of children from birth families and the supplanting of legal identity that occurs in plenary adoption makes this form of adoption unacceptable to many.

Simple adoption, allowing for children to be full legal members of both their adoptive and birth families and preserving legal identity, makes it attractive to individuals with a variety of experience backgrounds.

An exploration of legislative reform to allow for simple adoption in Australia should be undertaken.

Throughout the developed world, large numbers of children and young people are removed from parental care by the state because of concerns for their wellbeing (Thoburn, Citation2010). For some children, it is decided they cannot safely return home and long-term care arrangements are needed. It is acknowledged that alternative family care that is stable and provides love, belonging, and ongoing support promotes best outcomes (Cashmore & Paxman, Citation2006; Pecora et al., Citation2010). However, there is contention over which sort of legal care framework is optimal for these children (del Valle & Bravo, Citation2013).

In Australia, there were 46,000 children in out-of-home care (OOHC) in 2019–2020 of which more than 24,500 had long-term care and protection orders (AIHW, Citation2021b). The most common care arrangement for these children is long-term foster or kinship care. However, foster care placements are commonly unstable, which has multiple negative impacts on children (Scannapieco et al., Citation2016). Recognising these harms, Australian governments have endeavoured to reduce the number of placements children experience by better supporting families, so, where possible, reunification can occur (AIHW, Citation2021b). When this is not possible, care arrangements that provide greater permanency are encouraged (AIHW, Citation2021b).

The options currently available in Australia to provide greater permanency are guardianship and plenary adoption (AIHW, Citation2016). Guardianship orders confer parental responsibility and authority to guardian parents until legal age of majority (18 years in all Australian jurisdictions) (AIHW, Citation2021a). Guardianship orders do not alter the legal relationship between children and their birth family, do not create a legal relationship between children and members of their extended guardianship families, do not change the legal identity of children, do not result in any change to children’s birth certificates, and expire when children attain 18 years (AIHW, Citation2021a). Plenary adoption is the only form of adoption available in Australia (AIHW, Citation2021a). Plenary adoption confers exclusive parental responsibility to adoptive parents and creates an enduring familial relationship between children and their immediate and extended adoptive families (AIHW, Citation2021a). While open adoption and ongoing contact with birth families are normative in Australia (AIHW, Citation2021a), plenary adoption severs legal ties between children and their entire birth family, meaning children are no longer legally related to them (Ouellette, Citation2009). Plenary adoption creates a new legal identity for children that supplants their first identity. Integral to this process is creation of new birth certificates and invalidation of children’s original birth certificates as legal identity documents (Mandryk, Citation2011).

There has been considerable public discussion in Australia concerning the most desirable permanency option for children. While adoption has been put forward as the best option in terms of providing children with stability and belonging, some have strongly objected to the legal severance of children from birth families and the removal of legal identity involved (Bretherton et al., Citation2016; Mackieson et al., Citation2019). Concern about these aspects of adoption is such that despite legislation in the state of Victoria mandating adoption as the preferred permanence option for children (Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 [Victoria]), there were zero adoptions from OOHC in 2019–2020 (Personal communication, AIHW, 30 July 2021). Furthermore, a Victorian Government inquiry recommended adoption be removed altogether from the hierarchy of options stating that adoption “is at odds with the child’s right to have their identity, name and family relations preserved” (Commission for Children and Young People, Citation2017, p. 23). It is only in the state of New South Wales (NSW) that adoption is practised as a permanency option (AIHW, Citation2021a).

That Australia only legislates plenary adoption is a vestige of history. Current adoption legislation is derived from laws enacted in the post-World War II period when ex-nuptial pregnancy was scandalous (Quartly & Swain, Citation2012; Senate of Australia Community Affairs References Committee, Citation2012) and adoption was viewed as saving children from “unfit” single mothers (Jones, Citation2000). Therefore, parliaments enacted legislation that completely and permanently, physically and legally, separated children from their birth families while cementing them within adoptive families “as if born” into them (Swain, Citation2011). Total secrecy ensured a “clean break” that would protect children from the shame of illegitimacy and prevent reclamation (Swain, Citation2011). Thus, adoption removed children’s preadoptive identity and created new legal identities with birth certificates naming adopters as parents (Quartly & Swain, Citation2012). Adoptive parents were commonly advised to conceal the adoption from children and adopted people were legally prohibited from obtaining information identifying their family (Quartly et al., Citation2013).

Adoption practice in Australia has since changed. From the early 1970s, single motherhood was destigmatised and one-third of Australian infants are now born to unmarried women (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2018). While there were almost 10,000 children adopted in 1971–1972, there were just 48 adoptions by someone other than a step-parent, relative, or foster carer in 2019–2020 (AIHW, Citation2021a). Legislative reform from the 1980s gradually removed secrecy provisions from adoption legislation (Swain, Citation2011; Turner, Citation1993). All Australian jurisdictions now encourage openness in adoption, including ongoing, in-person contact between children and their birth family (Monahan & Hyatt, Citation2018). Current Australian practice recognises that adopted children have two families who are important to them and with whom connections and a sense of belonging are beneficial. However, the legal limitation of adoption to only the plenary form does not reflect this recognition.

Historical practices of forced removal of Indigenous children from their families, and the persistently high and disproportionate number of Indigenous children in OOHC in Australia, cannot go without mention. The current rate of 56 per 1000 Indigenous children living in OOHC is 11 times the rate for non-Indigenous children (AIHW, Citation2021b). Any changes to permanency practice may disproportionately impact Indigenous children and their families (Turnbull-Roberts et al., Citation2022). Given this egregious history, it is not surprising that plenary adoption is deemed the least favourable permanency option for Indigenous children (AIHW, Citation2016).

Some countries including France, Portugal, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, Argentina, and Uruguay have a form of adoption called simple adoption (O'Halloran, Citation2015; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Citation2009). Simple adoption allows conference of exclusive parental responsibility to adoptive parents and creation of enduring familial relationships between children and their adoptive families while retaining childrens legal relatedness to their birth families (O'Halloran, Citation2015). Simple adoption is similar to guardianship in preserving children’s identity and legal connection to their family of origin but different in that the legal relationship with caregiving parents does not expire at majority and is extended to the whole adoptive family. Simple adoption is similar to plenary adoption in making a new identity and an enduring legal relationship with an adoptive family but different in that preadoptive legal identity and legal connection to one’s birth family are preserved.

Legal frameworks of care impact the lives of people who live with them, including children and their birth, foster, guardianship, and adoptive families. However, there is a dearth of research on how these legal frameworks are experienced by those who live with them and how these frameworks could be improved. Similarly, how professionals working with children and families in the OOHC sector regard these frameworks is underexamined. It is probable that different stakeholders hold different views and it is important to gain a range of perspectives in exploring permanency options.

The purpose of this study was to ascertain how those with a personal or professional experience of OOHC or adoption view long-term foster care, guardianship, plenary adoption, and simple adoption. Specifically, this study sought to answer the following research questions:

What aspects of each existing legal framework are considered strengths and weaknesses?

What aspects of a proposed framework for permanency (simple adoption) are considered strengths and weaknesses?

Method

Study Design and Setting

The study used a descriptive survey design involving a questionnaire on the online platform Qualtrics® to consider the views of individuals living in Australia regarding the strengths and weaknesses of legal care frameworks for children in OOHC. Responses were collected from June to September 2018.

Sampling and Recruitment

Recruitment was conducted via the professional networks of the researchers and social media and targeted individuals with personal or professional experience with OOHC or adoption. Adoptees, adoptive parents, prospective adoptive parents, foster and kinship carers, guardians, care leavers, birth parents of children in OOHC or who had been adopted, and health and child welfare professionals working with any of these groups were specifically sought. Respondents were required to be aged 18 years or older and living in Australia.

Survey and Data Collection

The survey provided descriptions of the legal frameworks of long-term foster care, guardianship, plenary adoption, and simple adoption (in this order) and asked respondents to rank the attributes of each as either (i) a strength, (ii) a weakness, (iii) both a strength and a weakness, or (iv) neither a strength nor a weakness. The legal frameworks were presented in the above order so that respondents could more easily reflect on the increase in legal permanency through the progression and so that simple adoption could be assessed with the existing frameworks fresh in their minds. Eighteen aspects of long-term foster care, 18 aspects of guardianship, and 18 aspects of plenary adoption were included for ranking. Respondents were asked to rank nine aspects of simple adoption that would differentiate it from guardianship and plenary adoption. Descriptions of each legal framework provided are in Supplementary File 1.

Data Analysis

Data from respondents who had evaluated at least one legal framework were analysed using Stata version 14.1. Strength scores were calculated by assigning one point to aspects of the framework nominated as a strength, 0.5 points for characteristics nominated as a strength and a weakness, and 0 points for characteristics nominated as neither a strength nor a weakness. Weakness scores were calculated in a corresponding fashion. Since respondents only ranked aspects of simple adoption that would differentiate it from guardianship and plenary adoption, calculation of strength and weakness scores for this framework included the ranking data from relevant aspects of plenary adoption. These were parenting assessment is undertaken before adoption; lack of ongoing supervision of parenting; agencies do not make decisions for children, children cannot be returned to their birth family; children are not moved from adoptive placements unless there is maltreatment; and adoptive parents organise, supervise and can allow additional birth family contact. Strength and weakness scores were averaged for every respondent and the comparison of the mean strength and weakness scores and their 95% confidence interval for each framework were calculated. Ethics approval was obtained from Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained before survey initiation.

Results

One thousand and nineteen surveys were included in the analysis. Respondents were from all jurisdictions, with NSW the most common jurisdiction of residence. Respondents were overwhelmingly female and the majority were 46 years of age or older. Just over half of respondents had university qualifications (see ). Five hundred and forty respondents nominated their racial or cultural background as Australian and additionally or separately stated they were White or Caucasian or Anglo (205), English or British (85), Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (80), European (32), Irish (30), Italian (20), Scottish (19), Chinese (18), or New Zealander (16). Fifteen respondents stated they had no racial or cultural background or they did not know their background because of adoption.

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Seven hundred and ninety-three respondents nominated their connection to OOHC or adoption (see ). This connection was most commonly as a foster or kinship carer, followed by a health or child welfare professional, adoptive parent, adoptee, or prospective adoptive parent. There were smaller numbers of guardians, care leavers, and birth family members of children in OOHC or who had been adopted. Individuals in the “other” category were most commonly extended family and friends of adoptees, care leavers, or foster or kinship carers. Nearly half of respondents nominated multiple connections to OOHC or adoption: 188 nominated two connections, 50 nominated three, 53 nominated four, and the remaining 74 respondents nominated five to 11 connections. For example, 70 out of 95 prospective adoptive parents were foster or kinship carers, 29 out of 206 adoptees were health or child welfare professionals, and 7 out of 26 birth parents of children in care were care leavers themselves.

Table 2 Connection of Respondents to OOHC or Adoption

Long-Term Foster Care

One thousand and nineteen respondents ranked each aspect of long-term foster care. The characteristics most frequently identified as strengths were that foster care agencies pay for specialist support for children and that foster carers are given money to help care for children (see ). The aspects most commonly identified as weaknesses were that children can easily be moved from their foster family and that children do not have inheritance rights in their foster family.

Table 3 Frequency of Evaluation of Aspects of Long-Term Foster Care

Guardianship

A total of 877 respondents ranked each aspect of guardianship. The characteristics most commonly identified as strengths were that parenting is assessed before guardianship orders are made and children have a legal connection to their guardians (see ). The aspects most commonly identified as weaknesses were that the legal relationship between children and their guardians ends at 18 and no legal relationship is made between children and their extended guardian family.

Table 4 Frequency of Evaluation of Aspects of Guardianship

Plenary Adoption

A total of 840 individuals ranked each aspect of plenary adoption. The aspects most commonly identified as strengths were that parenting of foster carers is assessed before children are adopted and the legal relationship between children and adoptive parents does not end at 18 (see ). The aspects most commonly identified as weaknesses were that children lose inheritance rights from their birth family and adoption cuts the legal ties between children and their birth family.

Table 5 Frequency of Evaluation of Aspects of Care in Plenary Adoption

Simple Adoption

A total of 807 respondents ranked aspects of simple adoption that differentiate it from guardianship and plenary adoption. Aspects most commonly ranked as strengths were that the legal relationship between children and adoptive parents would not end at 18 and a legal relationship would be made between children and their extended adoptive family (see ). The only aspect identified by more than 10% of respondents as a weakness was that children could keep the surname of their birth parents and also have the surname of their adoptive parents.

Table 6 Frequency of Evaluation of Aspects of Simple Adoption

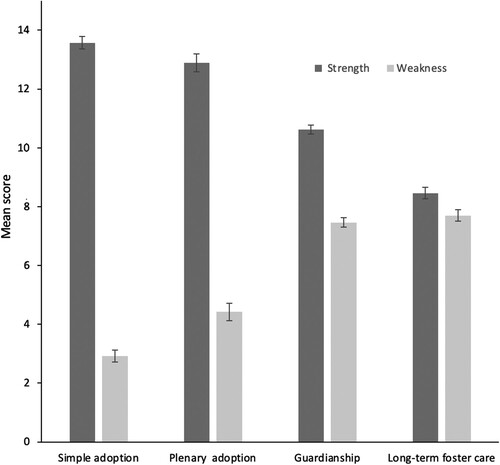

Strength and Weakness Scores

Simple adoption had the highest strength score, followed by plenary adoption, and guardianship, with long-term foster care having the lowest strength score (see ). Conversely, long-term foster care had the highest weakness score, followed by guardianship and plenary adoption, with simple adoption having the lowest weakness score. There was a high level of agreement across various aspects of legal frameworks, indicating that respondents saw legal connectedness to both birth and caregiving family and preservation of identity as valuable. Disagreement was more common in relation to issues such as checks on the welfare of children, continuing financial support for caregiving parents, inheritance, and name changes.

Figure 1 Strengths and weakness scores for long-term foster care, guardianship, plenary adoption, and simple adoption (errors in bars 95% confidence interval)

Strength and weakness scores were calculated for each OOHC or adoption connection grouping. Scores and relative ranking of each legal framework varied according to the connection to OOHC or adoption (see ). Evaluation of individual aspects of legal frameworks provides insight into how personal experience may have influenced views. For example, low strength and high weakness scores for plenary adoption were calculated for adoptees. Adoptees frequently evaluated aspects of plenary adoption related to removal of identity and legal severance from one’s birth family as weaknesses: 89 out of 124 (72%) viewed replacing the names of birth parents with adoptive parents on birth certificates as a weakness or a strength and a weakness, and 101 out of 124 (81%) evaluated legal severance of children from their birth family as a weakness or a strength and weakness. That simple adoption preserved identity and legal belonging in a birth family was viewed positively: 102 out of 124 (82%) of adoptees viewed children having surnames of both birth and adoptive families as a strength or a strength and weakness, 110 out of 124 (89%) evaluated retaining legal connection to birth parents as a strength or strength and weakness, and 113 out of 124 (91%) regarded retaining legal connection to one’s extended birth family as a strength or a strength and weakness. In another example, birth parents of children in care and birth parents of adoptees had particularly low strength scores and high weakness scores for plenary adoption and high strength scores and low weakness scores for long-term foster care. They overwhelmingly viewed legal severance from one’s birth family in plenary adoption negatively with 19 out of 26 (73%) of birth parents of children in care and 23 out of 25 (92%) of birth parents of adoptees evaluating this aspect of plenary adoption as an outright weakness. That children in long-term foster care could be easily returned to the care of birth parents was viewed as a strength or both a strength and weakness by 18 out of 26 (69%) of birth parents of children in care and 22 out of 25 (88%) of birth parents of adoptees. In contrast, this same aspect of foster care was viewed as an outright weakness by 106 out of 130 (82%) adoptive parents.

Table 7 Strength and weakness scores for long-term foster care, guardianship, plenary adoption, and simple adoption according to respondent connection to OOHC or adoption

Discussion

This study is the first in Australia to consider the views of people with experience of OOHC and adoption on legal frameworks for providing children with permanency. There were areas of disagreement between and within groups who had different connections to OOHC and adoption, some of these will be explored in future publications. However, there also was broad agreement on many issues. Notably, preservation or creation of legal relatedness and identity were revealed as important considerations across all groups. The lack, or limited nature, of the legal relationship between children and their caregiving family in long-term foster care and guardianship was commonly regarded negatively. However, preservation of legal relationships with one’s birth family under these frameworks was valued. Conversely, legal severance of children from one’s birth family and erasure of legal identity in plenary adoption were commonly viewed negatively. However, creation of enduring legal membership in an adoptive family was regarded positively. Given that simple adoption, as proposed in this study, allowed legal preservation of one’s birth family membership and identity while providing enduring legal belonging in an adoptive family, it is unsurprising that it was evaluated overall as having more strengths and fewer weaknesses than guardianship or plenary adoption.

In Australia, simple adoption was proposed in the early days of adoption reform. The 1983 Report of the Adoption Legislative Review Committee in Victoria stated that:

The Committee considers the essence of adoption to be the establishment of the new family relationship for the child rather than the severance of previous relationships. We believe that … the transfer of parental rights of guardianship and custody through the granting of an adoption order … is the essential element of adoption … [legislation] should allow for the social and/or legal relationship to continue between child and natural parent (Adoption Legislative Review Committee, Victoria, Citation1983, p. 44, emphasis in original).

Internationally, others have proposed that simple adoption may be beneficial in contexts where adoptions are open or as an alternative to long-term foster care (MacDonald, Citation2017; South African Law Commission, Citation2001; Staatscommissie Herijking Ouderschap, Citation2016). However, worldwide simple adoption is currently more commonly employed in adult, step-parent, or relative adoption and is not used in any widespread manner for children from OOHC (O'Halloran, Citation2015). Exploration of the broader implications of legislation of simple adoption in contexts where it previously has not existed, including in Australia, is needed. This should include consideration of issues related to birth certificates, next of kin, immigration, and inheritance.

Limitations

The self-selecting nature of respondents and that the study sample over-represented some groups and under-represented others is a limitation of the research. Furthermore, it appeared (based on their age) that the majority of adoptees and birth parents of adoptees were of the “forced adoption” period of the 1960s to 1980s (Senate of Australia Community Affairs References Committee, Citation2012) rather than having experienced adoption from OOHC. Future research could gain insight from people with experience of more contemporary adoption practices. This research did not examine other issues associated with permanency such as how to best support children, their caregiving families, and their birth families after guardianship or adoption orders are granted. Nor did it consider how to support families so that children do not need long-term, alternative care. The survey was lengthy, which would have presented difficulties for individuals with low literacy levels and may account for the noncompletion of some surveys. The fixed order of presentation of legal frameworks for assessment within the survey also meant that later presented legal frameworks were evaluated by fewer respondents due to attrition. Some of these issues will be addressed in future interview-based research. It must also be acknowledged that despite the disproportionately high numbers of Indigenous children residing in OOHC in Australia (AIHW, Citation2021b), the survey did not measure responses specific to this population. Future research may explore the concept of simple adoption as it relates to First Nations peoples.

Conclusion

This research identified that people with a personal experience of OOHC and adoption view legal relatedness and identity as important for children in OOHC. The proposal of a legal framework, in simple adoption, that would allow children to be full legal members of adoptive families while remaining legal members of birth families was attractive to individuals with a variety of experience backgrounds. Legislative reform to allow for simple adoption of children from OOHC in Australia should be explored.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to express our sincere thanks to the individuals who provided input and advice into the design of the study questionnaire, those who shared the study recruitment information on their Facebook pages, and the study respondents who so generously shared their views.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adoption Legislative Review Committee, Victoria. (1983). Report of the adoption legislative review committee. Victorian Government.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018). 3301.0-Births, Australia, 2017. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/3301.02017.

- AIHW. (2016). Permanency planning in child protection: A review of current concepts and available data.

- AIHW. (2021a). Adoptions Australia 2019-20.

- AIHW. (2021b). Child protection Australia 2019-20.

- Bretherton, T., Webb, T., & Kaltner, M. (2016). The gap between knowing and doing: Developing practice in open adoption from OOHC in New South Wales. NSW Family and Community Services.

- Cashmore, J., & Paxman, M. (2006). Predicting after-care outcomes: The importance of ‘felt’ security. Child and Family Social Work, 11(3), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00430.x

- Commission for Children and Young People. (2017). ‘ … safe and wanted … ': Inquiry into the implementation of the children, youth and families (permanent care and other matters) Act 2014.

- del Valle, J. F., & Bravo, A. (2013). Current trends, figures and challenges in out of home child care: An international comparative analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 22(3), 251–257. https://doi.org/10.5093/in2013a28

- Jones, C. (2000). Adoption – A study of post-war child removal in New South Wales. Royal Australian Historical Society, 86(1), 51–64.

- MacDonald, M. (2017). Connecting or disconnecting? Adoptive parents’ experiences of post adoption contact and their support needs. Health and Social Care Board, Northern Island.

- Mackieson, P., Shlonsky, A., & Connolly, M. (2019). Permanent care orders in Victoria: A thematic analysis of implementation issues. Australian Social Work, 72(4), 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1539112

- Mandryk, M. K. (2011). Adopted persons’ access to and use of their original birth certificates: An analysis of Australian policy and legislation (Master of Social Science Thesis, RMIT University).

- Monahan, G., & Hyatt, J. (2018). Adoption law and practice in Australia. Singapore Academy of Law Journal, 30, 484–517.

- O'Halloran, K. (2015). Politics of adoption: International perspective on law, policy and practice. Springer.

- Ouellette, F.-R. (2009). The social temporalities of adoption and the limits of plenary adoption. In D. Marre & L. Briggs (Eds.), International adoption: Global inequalities and the circulation of children (pp. 69–86). NYU Press.

- Pecora, P. J., Kessler, R. C., Williams, J., Downs, A. C., English, D. J., White, J., & O'Brien, K. (2010). What works in foster care: Key components of success from the Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study. Oxford University Press.

- Quartly, M., & Swain, S. (2012). The market in children: Analysing the language of adoption in Australia. History Australia, 9(2), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/14490854.2012.11668418

- Quartly, M., Swain, S., & Cuthbert, D. (2013). The market in babies: Stories of Australian adoption. Monash University Publishing.

- Scannapieco, M., Smith, M., & Blakeney-Strong, A. (2016). Transition from foster care to independent living: Ecological predictors associated with outcomes. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33(4), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0426-0

- Senate of Australia Community Affairs References Committee. (2012). Commonwealth contribution to former forced adoption policies and practices. Commonwealth of Australia.

- South African Law Commission. (2001). Discussion paper 103: Review of the Child Care Act.

- Staatscommissie Herijking Ouderschap. (2016). Kind en ouders in de 21ste eeuw.

- Swain, S. (2011). Adoption, secrecy and the spectre of the true mother in twentieth-century Australia. Australian Feminist Studies, 26(68), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2011.574599

- Thoburn, J. (2010). Achieving safety, stability and belonging for children in out-of-home care: The search for ‘what works’ across national boundaries. International Journal for Child and Family Welfare, 1-2, 34–49.

- Turnbull-Roberts, V., Salter, M., & Newton, B. J. (2022). Trauma then and now: Implications of adoption reform for First Nations children. Child & Family Social Work, 27(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12865

- Turner, J. N. (1993). Review of the adoption information Act 1990 (NSW), July 1992. Monash University Law Review, 19(2), 343–354.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2009). Child adoption: Trends and policies. United Nations.