ABSTRACT

The aim of this article was to present students’ responses to learning about community development and groupwork within the context of the natural world and human communities under threat, sometimes referred to as “greening the curriculum”. Students’ perceptions of such greening initiatives are currently underrepresented in the literature. The community development and group work unit under study was part of an Australian qualifying Masters of Social Work program. Students’ perceptions of greening the curriculum were examined using a case study methodology, with quantitative and qualitative data collected. Their responses provided insight into efficacy of the Unit. Results indicated that students’ awareness of the connections between social work, the natural environment, and ecological justice increased, and their confidence to carry this connection forward into their social work practice was strengthened. These results illustrate how students with no prior, or little, interest in “green social work” can achieve deep, meaningful, and even transformative progress towards ecological social work practice.

Embedding ecological justice content into community development and group work curriculum can provide a holistic context for learning.

The inclusion of ecological justice in social work curricula can be transformative for students and future social work practice.

The student “voice” adds to the growing impetus of ecological justice in social work curriculum.

IMPLICATIONS

Social work’s remit to include the natural environment and ecological justice in theory and practice has recently attracted increased scholarship (Hudson, Citation2019; Nipperess & Boddy, Citation2018). A study by Krings et al. (Citation2020) indicated the percentage of publications on environmental social work has grown from 0.7% in 1991 to 2.1% in 2015. Internationally, through the International Federation of Social Workers, and in Australia through the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW), the need to address unsustainable economic and environmental systems that perpetuate environmental injustices has been made explicit in professional codes (McKinnin & Alston, Citation2016).

Although the mandate to include the natural environment in conceptualising social work theory and practice has been active for some time, research on its integration into social work curricula and practice is newly emerging (Hudson, Citation2019; Ramsay & Boddy, Citation2017). For the profession to progress its theoretical and practice modalities, explicit links between social justice and environmental justice need to be articulated and assessed in curricula, to shift it from the margins of social work education and practice (Naranjo, Citation2020).

This article details students’ perceptions of a curricular initiative that used ecological justice as the context for learning about, and assessing, community development and group work. The title quote, “It is important to see a change in the [social work] narrative” (derived from data collected in this study) foregrounds how students described new, and for some transformative, awareness of what greening social work might look like in practice. The term “ecological justice” is used in this article to recognise the deep interconnectedness of the human community with nature and with each other and to consider the implications for social work theory and practice (Besthorn, Citation2012).

Ecological Social Work

Although environmental issues were evident in social work at its inception (through advocacy in Settlement Houses), a subsequent individualised, therapeutic focus undermined the influence of the natural and built environments on human health. The environment was revisited in the 1960s with renewed public consciousness about environmental concerns (Krings et al., Citation2020). More recently, researchers have asserted that social work needs a paradigm shift from a human-centered to a more ecological and holistic worldview that recognises the interconnectedness of humans with nature and community (Boetto, Citation2017). Boetto (Citation2019) argued that the “modernist philosophical roots and industrial capitalism in which modern social work was shaped” (p. 141) continue to reinforce a human-centric view. The profession’s modernist lens sees the natural environment as an objective entity, independent and separate from humans (Coates, Citation2005). Bozalek and Pease (Citation2021) agreed that conventional and critical social work paradigms have struggled to theorise the relationship between humans and nature. Besthorn (Citation2012) laid early conceptual foundations by exploring how deep ecology offers a fundamental shift in the way humanity views its relationship with nature, with ontological implications for social work. This perspective counters entrenched anthropocentric perspectives where humans are privileged over the natural world and nature is for, and subject to, humans. Naranjo (Citation2020) added that mitigating the negative environmental effects of modernity, capitalism, and globalisation requires international cooperation and a new ecological paradigm within social work that highlights ecological justice as a key issue in teaching and learning.

“Ecological justice” is proposed as an extension on the term “environmental justice”; the latter tending to retain humans at the centre of environmental resources and privileging them as primary recipients (Boetto, Citation2017). Miller et al. (Citation2012) clarified that “environmental justice focuses on the needs and risks of humans in the physical environment, whereas ecological justice focuses on the needs and risks of nature and how humans fit in it” (p. 27). Other significant contributions to the literature include Green Social Work, pioneered by Dominelli (Citation2012), encouraging social workers to join other disciplines to intervene to protect the environment in ways that address prevailing structural inequalities and unequal distribution of resources.

There is a growing openness to the worldviews of Indigenous and First Nations peoples emerging in the literature. Core assumptions of this worldview see “humans as part of a web of life that is interconnected, interdependent, emerging and relational” (Coates et al., Citation2006, p. 391). In the Australian context, First Peoples have had stewardship of Australia’s environment for tens of thousands of years and continue to act in its interests, despite the denial of their sovereignty and the ravages of colonisation (Woodley & Ross, Citation2021). To Indigenous Australians, Country relates to all aspects of existence—culture, spirituality, language, law, family, and identity (Kingsley et al., Citation2018). Each person is connected to Country through their kinship system and is entrusted with the knowledge and responsibility to care for their land, “providing a deep sense of identity, purpose and belonging” (Terare & Rawsthorne, Citation2020, p. 946). White settlement in Australia has failed to appreciate the strengths of Australian First Nations’ caring work on Country (Lohoar et al., Citation2014). Woodley and Ross (Citation2021) recommended advancement towards environmental justice in social work practice. This includes an ongoing reflexive commitment to decolonising ideas, practices, and relationships, and recognising the invisibility of Whiteness and its associated privileges (Boetto, Citation2019).

Ecological Social Work and Social Work Education

Many terms have been used in the bourgeoning literature drawing social work’s attention to the natural environment, which has possibly hindered its practical application in education and practice. Ramsay and Boddy (Citation2017) identified four key aspects of environmental social work in the literature that are helpful levers for curriculum development: “creative application of existing social work skills to environmental concepts … ; openness to different values and ways of being or doing; a change orientation and working across boundaries”, including interdisciplinary collaborations (Ramsay & Boddy, Citation2017, p. 72). Boddy et al. (Citation2018) argued that the intersection of the environmental crisis with crucial social work concepts, such as human rights, social justice, sustainable development, and human health, lends itself to embedding environmental justice into existing social work curricula. They highlighted that social work education has made some progress introducing eco-social work by developing new units in social work courses, embedding it into existing core units or practicums, or providing a voluntary extracurricular unit. Although these efforts have diverse delivery, pedagogically, they are largely focused on transformative learning, critical reflection, and experiential learning processes (Nipperess & Boddy, Citation2018).

There are recent signs that progress has become more visible in mainstream social work education, with examples of a range of approaches in the literature (Nipperess & Boddy, Citation2018; Papadopoulos, Citation2019). The recently revised Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS) Required Curriculum Content has included references to environmental health and wellbeing and acknowledged Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders’ commitment to safeguarding and repairing the physical environment (AASW, Citation2020). This signals a step toward some requirement for implementation as social work adapts to its changing contexts.

Jones (Citation2018) noted more recent initiatives in social work education and added the cautionary concern expressed by Gray and Coates (Citation2015) that inserting content into the traditional curricula does not constitute a fundamental rethinking of its humanistic values and theories. Jones (Citation2018) suggested these initiatives fall into three approaches: “bolt-on” (adding new units or content); “embedding” (integrating new content on the values, knowledge, and skills for an eco-social focus); and “transformative” (using foundational concepts of an eco-social approach as the fundamental basis for social work education). For this transformative approach he recommended starting with eco-social concepts and Ife’s (Citation2016) guiding principles of “holism, sustainability, diversity, equilibrium, and interdependence” (p. 47), from which related values, knowledge, and skills are extrapolated. Jones (Citation2018) identified pedagogies related to transformative learning and eco-literacy, among others, to support this curriculum redevelopment.

Any change in practices, in social work education, and in the field, need to negotiate cultural and systemic barriers. Kemmis et al. (Citation2014) described practices as held in place by “practice architectures” (p. 58), which enable or constrain practice change. These architectures are cultural-discursive, material-economic, and sociopolitical arrangements. These authors argued that to influence situated change, material resources (e.g., in the form of time, place, and expertise), social relationships (between educators, practitioners, managers, and students), and purposeful narratives (“communication in semantic space”) need to be engaged. “Changes in the narrative” (Kemmis et al., Citation2014, p. 60) are needed to challenge anthropocentric hegemony, contribute to the process of curricular and practice change, along with advocating for the material resources and the social relationships that underpin that change. Students’ responses to the efforts toward greening social work curriculua have not been well represented in the literature to date. This study contributes a step toward filling that gap in the literature.

Method

Curriculum Under Study

The Masters of Social Work (MSW) in the case study was a postgraduate, online qualifying program comprising 12 core units. The unit under study, Practicing Social Work with Communities and Groups, was positioned in the second year of the MSW. As the Unit Chair, the author was allocated additional curriculum development hours to redesign the curriculum in 2019–2020, with feedback from academic colleagues, students, and from the field. Ecological justice formed the context, values, and theoretical orientation, from which community development and group work knowledge and skills were studied. The learning outcomes remained focused on the community development and group work learning. There were 11 topics over the 11-week trimester, with the first 7 weeks primarily focused on community development materials and the final 4 weeks on group work. The two-day intensive session in Week 4 included both community development and group work content. The weekly topics spanned: social work with communities; context and theories; understanding communities and group work skills; (Intensive); processes and values; principles of community development; strategy development; group work skills and community development; group work and learning with community; group work and theory applied; and contemporary community development.

Ife’s (Citation2016) ecological principles of “holism, sustainability, diversity, equilibrium, and interdependence” (p. 47) were outlined at the outset of the Unit. Their practical outworking in community development and group work were explored throughout the learning materials. This explicitly critiqued the dominant discourse that science and technology can provide the answers to current environmental problems (Gray & Coates, Citation2015). With the inclusion of this content, I sought to transgress the norms of unbridled growth, anthropocentrism, consumption, and individualism, consistent with transformational learning (Jones, Citation2013).

Being in online mode, the Unit was largely scenario-based, using simulations to replicate real-world situations (Jones, Citation2013; Papadopoulos, Citation2019). Reflexive exercises and case studies were introduced to explore disorientating dilemmas for students, and stimulus questions encouraged them to make connections with their local contexts. Alternative ways of viewing community and the natural world from anthropocentric perspectives were explored. Interactive seminars, a learning journal, videos, and a discussion forum were provided or recommended and accessible online. Assessments included a critical reflection on self-selected Unit readings; a critical analysis of a real community development practice example seeking to address climate change and sustainability in an urban community; and finally, a postdisaster group work scenario for students to simulate designing and planning with a cofacilitator. The interactive 2-day intensive (online during COVID) enabled dialogue responsive to the students’ life-worlds and experience and experiential learning. The primary textbook was Kenny and Connors (Citation2017) “Developing communities for the future”. Pedagogically, the curriculum drew on transformative learning, critical reflection, dialogic, and experiential learning approaches that built on students’ prior knowledge and experience (Nipperess & Boddy, Citation2018).

Research Design

The research used a case study methodology and drew on data from quantitative and qualitative surveys and interviews (Yin, Citation2014). The central tenet of a case study is exploring an event or phenomenon in depth and in its natural context (Crowe et al., Citation2011). Drawing on a constructivist epistemology, student perspectives were elicited as close to the “event” as ethically possible, to capture their complete experiences. Stake (Citation1995) outlined an “instrumental” form of case study that uses a particular case to gain a broader appreciation of an issue or phenomenon. In this case, the “phenomenon” was a redesigned curriculum in one unit of study in one University using the context of ecological justice to teach social work disciplinary knowledge. The goal of this project was to expand analytic generalisations from student perspectives, to potentially inform learning and teaching practices, rather than generate statistical generalisations (Yin, Citation2014).

Participants

Enrolled students in the Unit in 2020 and 2021 were invited to participate in semistructured interviews to be conducted after their assessments had been completed and marked. The recorded interviews were administered and undertaken by a colleague in a department that is outside the social work program’s faculty (Manager of Academic and Peer Support). The participants were aware that the Unit Chair had no knowledge of who had agreed to participate to manage the dual relationship of Unit Chair and researcher. Out of 90 students, 31 eVALUate surveys were completed and 8 students volunteered to be interviewed. Those interviewed included experienced social workers updating their qualifications and career changers new to social work, most were mature age with competing responsibilities, many of them currently working in the field while studying.

Ethics approval was granted by the University’s Faculty Human Research Ethics Committee (HEAG-H 22_2020).

Data Analysis

Quantitative and qualitative data from voluntary, anonymous University Student Evaluations (eVALUate) were supplemented by student interviews. EVALUates provided an anonymous forum for students’ perceptions of their engagement with the Unit, its relevance to their learning about community development and group work, and its strengths and weaknesses. The interviews examined the extent to which students’ awareness of the connections between social work, the environment, and ecological justice had increased, and if, or to what extent, their confidence to bring this connection into their future practice was strengthened.

Data analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2017) process of reflexive thematic analysis to identify common patterns of meaning throughout the text data from surveys and deidentified interview transcripts. Themes were coded and identified in draft form by the author. Draft themes were discussed and verified by the interviewer in consideration of researcher partiality, given their dual role as Unit Chair and researcher.

Results

University Student Evaluations

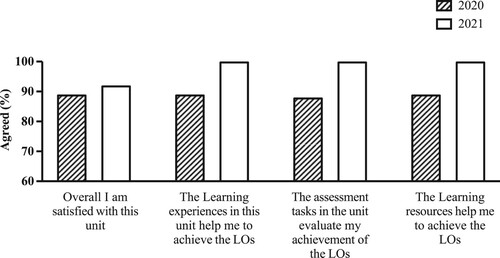

The university survey responses did not specifically reveal students’ increased understanding about ecological justice (given their standardised nature) but were indications of engagement with the Unit materials and reactions to the ecological justice context for learning. Across the quantitative and qualitative data of the student evaluations there were indications that there was a strong level of satisfaction with the Unit, with a small percentage of those who found it less satisfying in both 2020 and 2021 (Figure 1). The response rate to the eVALUates was higher in 2020 (50%) to 2021 (24%). It is hard to speculate on why, other than perhaps the cumulative effects of COVID19 lockdowns that left students physically and emotionally fatigued.

In both iterations, the quantitative data indicated that the assessment tasks and the learning resources helped students to achieve the Learning Outcomes (LOs). This can indicate engagement with the Unit, the relevance of ecological justice to their learning, and affirmation that, from the students’ perspectives, the Unit supported them to learn what they needed to learn. Collated qualitative comments reflected the quantitative responses above, for example: “The subject is very different to some of the others, but very important. Steep learning curve for me but really enjoyed it” (eVALUate, 2020); “The first and second assessments were fantastic, they helped to set the scene for what we can begin to do in practice” (eVALUate, 2020); and “The intensives were … a great way to apply knowledge in practice” (eVALUate, 2021).

Some critique after both iterations of the Unit included that it was difficult to get through all the readings, some thought the textbook was “dry” (although journal readings were engaging), and there could have been more content on practical application. For example: “Lots of theory, not enough about skills or techniques for practice” (eVALUate, 2020); and “The textbook is very interesting and helpful but very dense to read” (eVALUate, 2021).

Of 31 students who responded to eVALUate, two reported that they did not find the Unit engaging: “This Unit was difficult; all the content was dry and hard to read” (eVALUate, 2020); “I struggled to see the relevance of this Unit. The topic content seemed to be such a small part of social work” (eVALUate, 2021). For students who are oriented toward micro-practice, community development can be a challenging contrast. The attempts to clarify how social work and community development intersect, and to enlarge on the relevance of community development and groupwork knowledge and skills to all social work fields, did not seem to reach these two students.

The student evaluations provided some breadth of insight into the impact of the curriculum anonymously from the students’ perspectives. It indicates the students felt they learnt what they needed to learn, and the large majority could recognise the relevance of ecological justice to social work. The interviews, reported below, provided more insight into the progress of connections between the natural environment and social work.

Themes From Student Interviews

Thematic analysis of the qualitative data identified the following three themes: relevance of ecological justice to social work community development; application to social work practice; and a transformed perspective.

Relevance of Ecological Justice to Social Work Community Development

The interviews illustrated the shifts in awareness of the participating students from the commencement of the Unit. Many reported they had not heard of ecological justice and had made no prior connections between the natural environment, climate change, or ecological justice and social work. Some said they were unfamiliar with community development from their prior lived, or practice backgrounds, so there was a lot to take in. Different students made the following comments:

I had never thought of it [the environment] as an issue of justice. The Unit clarified that very clearly … It made it all more obviously clear to me—the link between poor environment, poverty and poor health. (Student 1, 2020)

Green social work wasn’t something that I knew anything about before … I think the biggest thing I got … was being able to link how people’s greed and thirst for money has really driven that mass production, which is unsustainable and will cause [more] damage if it’s not … corrected. (Student 1, 2021)

Some students recognised not only the relevance of ecological justice to social work but also the connection of community development principles and practice to broader social work practice. As one interviewee, with no prior knowledge of community development, who had not previously seen the connection of social work and the environment, indicated: “it was a lot more relevant than I was anticipating. I’m not … ever going to work in community development, but what I’ve learnt in the Unit you can see how it is possible [in] much more than one field” (Student 1, 2021). Two other student participants reported: “Using ecological justice as context to learn community development and group work concepts … was truly helpful … it was really interesting … and likely very useful” (Student 5, 2021); and “The Unit kept with the social work language—it built on our knowledge, still using language from Critical Social Work background” (Student 2, 2020).

Some students had an existing awareness of one or both aspects (of community development principles and the connection of social work to the environment) and welcomed the opportunity to extend their knowledge:

Ecological justice is a topic I am passionate about. The Unit is providing a bridge to bring ecological justice and social work [together]—the ecological as well as the psycho-social … It is important to see a change in the narrative … [for students] to create what they want to see as the change and note the barriers [in practice]. (Student 2, 2020)

Because I have been working in the field … I wasn’t sure how much new information [I would learn] … I actually learnt a lot … reading about community development projects that actually do happen … was really helpful … a lot of self-reflection during this Unit on what does community development mean and how … we apply it to the environmental context. (Student 3, 2021)

Application to Social Work Practice

The application to social work practice was challenging for some students, particularly in the first iteration of the Unit. Students’ responses from 2020 interviews included: “I appreciate the need to understand ecological justice, but how does that fit with clients’ priorities?” (Student 1, 2020), and:

There needs to be a massive paradigm shift [in the field] to be open to this approach. Is it possible to explore the reality of what students will face in relation to environmental justice? From personal experience, head butting with those who do not see the ecological as relevant to human health. (Student 2, 2020)

Based on this feedback, some changes to the curriculum were introduced in 2021, such as learning exercises on resistance in social work practice and additional practice-related readings. These minor changes resulted in a shift in the 2021 interview data. More students talked about recognising the applicability of the concepts to practice, for example:

When I first heard the term [ecological justice], I was like, okay, that’s super interesting, but how does that look in practice? … Whereas previously I would have felt it was so out of my realm, and maybe not relevant to what I was doing … I work in … in child protection … thinking … that’s not relevant for me, but … [the Unit] made it more applicable. … I can actually make this relevant to what I want to do now … mental health is my passion … I think that’s actually going to be quite easy [to incorporate]. (Student 4, 2021)

A really good [practice] example … gave you something that you could … go … I’m capable of doing that or … supporting that and it has a bigger … wider-ranging impact. (Student 1, 2021)

It … gave me tools that I would actually be able to put into practice … rather than just … the activist advocacy role. These are the practice tools you will need, and this is the focus and perspective that you have to be able to achieve that. (Student 5, 2021)

A Transformed Perspective

Students’ descriptions of a transformed perspective were promising for future integration into practice. Some students started noticing environmental hazards and issues in their local communities that had political implications as well as community and personal impacts, which suggested a growing eco-literacy (Jones, Citation2018). “I volunteered in Melbourne’s West [low socioeconomic area] and it is now so obviously barren of green space and [full of] heavy traffic” (Student 1, 2020);

Coming from that rural background where … the impact of climate change is prevalent … in your everyday … environmental justice as … its own awareness for me, was perspective changing and it was very much in line with my critical social work understanding. So, I really valued that. (Student 5, 2021)

Another student reflected on humans’ relationship with nature and the implications for social work practice:

[I asked myself] What is my role, not just responding to the needs of the people who’ve gone through environmental crisis, but what is my role as a social worker in building that relationship with nature. And I think that was touched on in the Unit. (Student 2, 2021)

Other students developed a new or renewed interest in ecological social work: “The Unit was really solid and well-structured, very accessible. It was so inspiring that I actually got the environmental justice textbook … Really integrated and woven in quite nicely” (Student 2, 2020).

Some students were not particularly enthusiastic about the environmental focus when going into the Unit, but their perspectives subsequently changed. Responses to the question, “to what extent do you think your attitudes about the environment and its role in social work have changed after the Unit?” included:

I would say that’s changed dramatically … I … work with a social worker. And when I was … talking about environmental justice … he … pooh-poohed it … and said, “how can the environment be your client?” So, I … went into the Unit with [the question] how can the environment be my client? And that question was answered, even if the question wasn’t necessarily overtly being asked … [it] changed my perspective a lot … how that would play out on a very micro level too, on an interpersonal level, on a small family level, on a small group level, on a community level, rather than just that massive macro level that you tend to think of climate change and advocacy on. (Student 5, 2021)

Overall … going into it I was a bit like, oh, I wasn’t that excited about it and environmental learning [was] not my area of interest. But I came out of it with a very different view. I felt that it was a really interesting and powerful learning journey. And I actually put down as one of my placement preferences to do it in the environmental social work context. So … that big of an impact! (Student 4, 2021)

Some students expressed appreciation for the focus and suggested that ecological justice and the role of the environment could preferably be integrated into other units in the course, as indicated: “It was really good having a very unique perspective put on social work when it comes to environmental justice … I haven’t seen that anywhere else … that is something … I’d like to see more of” (Student 5, 2021); and “I’m really excited to see it included in social work training … I think it’s very much needed and it … expands that whole person in environment concept” (Student 2, 2021).

Discussion

The results of this study, and more specifically the interview data, indicated alignment with the intent of the curriculum design, which was to apply environmental concepts to existing social work knowledge and skills, encourage openness to different ways of knowing and being, and maintain a change orientation (Ramsay & Boddy, Citation2017). The relevance of ecological justice to social work was largely recognised, perhaps in more expanded ways in the 2021 iteration. This recognition was enabled in part by responding to the implicit question of adult learners about relevance at the outset (Knowles et al., Citation2015), which possibly set the stage for deeper learning (Biggs & Tang, Citation2011). Being explicit about this connection early in the curriculum was particularly important given the students’ prior orientation to the natural environment being beyond the remit of social work.

These research findings indicated that the transition from abstract concepts into practical actions was emerging. The scenario-based learning and assessments, requiring analysis of challenges close to those encountered in practice to generate workable solutions, likely supported this transition (Papadopoulos, Citation2019). The research also illustrates that embedding ecological justice into university curricula has the potential to be transformative. As Jones (Citation2018) suggested, embedding can be considered a “bolted on” approach. However, perhaps when a set of concepts and values that contest anthropocentric values at the outset and are grounded in the recognition of the interdependent nature of humans’ relationship with the environment, the potential for transformation is enhanced (Ife, Citation2016). Boetto’s (Citation2017) assertion remains constant, “if social workers are consciously aware of the interconnected relationship between humanity and the natural world, then it is more likely the natural environment will be integrated into practice” (p. 53). Jones (Citation2013, Citation2018) suggested it is the loss of such awareness, or necessary literacies and the ensuing ecological alienation, which is a major contributing factor to the crisis that we now confront. When this foundational awareness informs the curricula content, and is supported by transformative pedagogies, new perspectives can emerge, with associated knowledge and skills (Jones, Citation2018).

For these transformed perspectives to adhere in social work practice, new narratives and literacies about ecological justice need to be spoken pervasively at the practice site (Kemmis et al., Citation2014). Ideally, and resources permitting, a more holistic transformation of the MSW curriculum would reinforce the relevance of ecological justice to all levels of practice. Transformed social work curricula can contribute to unsettling practice architectures to make room for, and enable, new social work practices.

Limitations

This was a small study situated in one University, with a relatively small number of student volunteers interviewed. The eVALUate data was an attempt to attract anonymous responses and a breadth of perspective. University student evaluations are generally considered flawed instruments for objective data (Ali et al., Citation2021). They can be statistically unreliable (depending on participation rates); skewed by contextual and external factors; highly subjective; and inherently biased in their design, which can influence the ways teaching is both perceived and evaluated (Ali et al., Citation2021). However, they were used in this research as a reflexive tool to seek a wider representation of responses, as it was (rightly) anticipated that participation in interviews would be low.

There were several challenges to the curriculum design, including the time necessitated in redesigning the Unit from scratch; the diverse cohort, some of whom were already in social work or community development practice and others who were new to the field; introducing new concepts to students with little prior recognition of their relevance; and the impact of the global pandemic on students, educators, and the enactment of the curriculum. This may have impacted on the response rate and potentially coloured some students’ experiences of the Unit.

Conclusion

This case study illuminated students’ perceived shifts in learning about ecological justice and its relationship to social work and community development. Their reported greater awareness of this relationship, and confidence to use it in practice, suggests some success in the curriculum’s intent. It appears that, at least in the case of some students, their future practice may be different as a result of the Unit. Other social work educators may be encouraged as they consider integrating ecological justice in curricula in other universities, while recognising that the challenge to keep deepening our ecological consciousness is an ongoing process.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ali, A., Crawford, J., Cejnar, L., Harman, K., & Sim, K. (2021). What student evaluations are not: Scholarship of Teaching and Learning using student evaluations. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 18(8), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.18.8.1

- Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2020). Australian social work education and accreditation standards. https://www.aasw.asn.au/careers-study/education-standards-accreditation

- Besthorn, F. (2012). Deep ecology’s contributions to social work: A ten-year retrospective. International Journal of Social Work, 66(3), 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00850.x

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does. Open University Press.

- Boddy, J., Macfarlane, S., & Greenslade, L. (2018). Social work and the natural environment: Embedding content across curricula. Australian Social Work, 71(3), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1447588

- Boetto, H. (2017). A transformative eco-social model: Challenging modernist assumptions in social work. British Journal of Social Work, 47(1), 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw149

- Boetto, H. (2019). Advancing transformative eco-social change: Shifting from Modernist to Holistic foundations. Australian Social Work, 72(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1484501

- Bozalek, V., & Pease, B. (Eds.). (2021). Post-anthropocentric social work. Routledge.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Coates, J. (2005). The environmental crisis: Implications for social work. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 16(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1300/J059v16n01_03

- Coates, J., Gray, M., & Hetherington, T. (2006). An ‘ecospiritual’ perspective: Finally, a place for Indigenous approaches. British Journal of Social Work, 36(3), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl005

- Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

- Dominelli, L. (2012). Green social work. Cambridge.

- Gray, M., & Coates, J. (2015). Changing gears: Shifting to an environmental perspective in social work education. Social Work Education, 34(5), 502–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1065807

- Hudson, J. (2019). Nature and social work pedagogy: How U.S. social work educators are integrating issues of the natural environment into their teaching. Journal of Community Practice, 27(3-4), 487–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2019.1660750

- Ife, J. (2016). Community development in an uncertain world. Cambridge.

- Jones, P. (2013). Transforming the curriculum: Social work education and ecological consciousness. In M. Gray, J. Coates, & T. Hetherington (Eds.), Environmental social work (pp. 213–230). Routledge.

- Jones, P. (2018). Greening social work education: Transforming the curriculum in pursuit of eco-social justice. In L. Dominelli (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of green social work (pp. 719–786). Routledge.

- Kemmis, S., McTaggert, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner. Springer.

- Kenny, S., & Connors, P. (2017). Developing communities for the future. Cengage.

- Kingsley, J., Munro-Harrison, E., Jenkins, A., & Thorpe, A. (2018). Here we are part of a living culture: Understanding the cultural determinants of health in Aboriginal gathering places in Victoria, Australia. Health and Place, 54, 210–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.10.001

- Knowles, M., Holton, E., & Swanson, R. (2015). The adult learner. Routledge.

- Krings, A., Victor, B., Mathias, J., & Perron, B. (2020). Environmental social work in the disciplinary literature,1991–2015. International Social Work, 63(3), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872818788397

- Lohoar, S., Butera, N., & Kennedy, E. (2014). Strengths of Australian Aboriginal cultural practices in family life and child rearing, CFCA paper no. 25. Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- McKinnin, J., & Alston, M. (Eds.). (2016). Ecological social work: Towards sustainability. Palgrave.

- Miller, S. E., Hayward, R. A., & Shaw, T. V. (2012). Environmental shifts for social work: A principles approach. International Journal of Social Welfare, 21(3), 270–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00848.x

- Naranjo, N. R. (2020). Environmental issues and social work education. British Journal of Social Work, 50(2), 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz168

- Nipperess, C., & Boddy, J. (2018). Greening Australian social work practice and education. In L. Dominelli (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of green social work (pp. 705–718). Routledge.

- Papadopoulos, A. (2019). Integrating the natural environment in social work education: Sustainability and scenario-based learning. Australian Social Work, 72(2), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1542012

- Ramsay, S., & Boddy, J. (2017). Environmental social work: A concept analysis. British Journal of Social Work, 47(1), 68–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw078

- Stake, R. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage.

- Terare, M., & Rawsthorne, M. (2020). Country is yarning to me: Worldview, health and well-being amongst Australian First Nations People. British Journal of Social Work, 50(3), 944–960. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz072

- Woodley, M., & Ross, D. (2021). First nation leaders’ lessons on sustainability and the environment for social work. In B. Bennett (Ed.), Aboriginal fields of practice (pp. 216–230). Red Globe Press.

- Yin, R. (2014). Case study research. Sage.