ABSTRACT

The human service context is a complex space for social workers and service users, bringing both challenges and opportunities. The ability to navigate challenges is essential for social workers to appropriately support clients and maintain longevity in human service work. Practitioners are expected to possess resilience to mitigate these challenges. Social workers are familiar with the concept of resilience in relation to work with clients. However, it is important they develop their own resilience to withstand industry pressure and build professional identity resilience (PIR). In this article, we drew on an Australian grounded theory PhD study that explored the experience of professional identity development (PID) for newly graduated social workers, specifically the challenges they faced in relation to PID and the link between professional identity and resilience. PIR emerged as a key concept in the process of forming a social work professional identity and seven protective factors were identified that support the development of PIR.

IMPLICATIONS

Developing professional identity resilience can assist students and graduates to counter challenging experiences of being a social worker.

Professional identity resilience plays an important role in the development and ongoing maintenance of professional identity and as such is essential knowledge for social work educators, professional associations, social work students and graduates.

Social workers operate in ever-changing complex spaces, facing challenges to their professional identity and resilience. In this article, professional identity resilience (PIR) refers to the ability to bounce back from challenges to professional identity—a person’s sense of their professional being. While the literature concerning professional resilience is well developed (Adamson et al., Citation2014; Collins, Citation2007; Grant & Kinman, Citation2014), the concept of PIR is less so.

Social Work in the Australian Context

How professional identity is defined and experienced is significantly influenced by the prevailing, political, economic, and social context. The social work profession has a history fraught with human rights violations, media censure, and general misconceptions about the role of social workers (Healy, Citation2015; Modderman et al., Citation2017). The influence of neoliberalism has created tensions for human service workers, including social workers (Gray et al., Citation2015; Wallace & Pease, Citation2011). With pressure to work more efficiently and effectively, and tools to support quick assessments and decision-making, less emphasis and value is placed on professional knowledge (Gray et al., Citation2015; Wallace & Pease, Citation2011). The role of social workers in this context can be unclear as they undertake diverse roles, work alongside trained and untrained staff with a range of qualifications and experience, and often lose their “social worker” title (Harrison & Healy, Citation2016; Long et al., Citation2018). Increased casualisation of the workforce has also led to instability of employment (Harrison & Healy, Citation2016).

Adding to this uncertainty, since the early 2000s, different Australian Governments’ responses to the profession have lacked understanding about social workers’ qualifications, knowledge, and skill levels. This is evidenced by the following policy initiatives: proposing to withdraw private-practice mental health social workers from the Federal healthcare scheme in the early 2000s (Stewart & Fielding, Citation2022): blocking social work registration with the Australian Health Practitioner Registration Agency (AHPRA) in 2012, based on a misconception that social workers do not provide crisis intervention (Fotheringham, Citation2017); and, at the height of the pandemic, attempting to double the cost of social work tertiary education (Papadopoulos, Citation2022), alleging that social work degrees do not produce “job ready” graduates. At these pivotal junctures, advocacy campaigns led by the Australian Association of Social Workers and the Australian Council of Heads of Schools of Social Work have highlighted and clarified the value of the profession (Stewart & Fielding, Citation2022).

It is understandable then, that social work graduates often experience tension when developing a social work professional identity. At a critical time in their professional development, graduates must navigate challenges concerning professional status, role clarity, misalignment of professional and organisational values, the absence of other social workers, and the broader community’s misunderstanding about social work. The role and professional space of social workers can be ambiguous with constraints across macro and micro practice domains (Wallace & Pease, Citation2011). New graduates, especially, receive mixed messages about their profession (Oliver, Citation2013). For social work students and graduates entering this challenging work environment, professional identity and professional resilience are important attributes influencing their professional longevity.

Professional Identity Development

Professional identity concerns “how people understand themselves in their professional roles and how others see this professional self” (Long et al., Citation2018, p. 117). Professional identity development (PID) is well-researched across professions (Long et al., Citation2018; Moorhead et al., Citation2016; Sharpless et al., Citation2015). Social work PID involves integrating an understanding of social work with personal identity, and being socialised into the professional community (Barretti, Citation2004; Miller, Citation2010; Pullen Sansfaçon & Crête, Citation2016; Wiles, Citation2013). Pre-education, during education and post-education are key stages in social work PID (Barretti Citation2004; Beddoe, Citation2011; Long et al., Citation2018; Miller, Citation2010) where professional identity is socially constructed as individuals interact with the world around them (Payne, Citation2006).

Challenges to Professional Identity

As Payne (Citation2006) noted, social work identity develops via interactions with others—colleagues, peers, service users, and the community. This leads to diverse understandings of social work and diversity in employment roles (Healy, Citation2015). Such diversity can lead to uncertainty for new graduates as they develop their professional identity, with potential for confusion from mixed messages in relation to what social work is, and the work they can undertake (Oliver, Citation2013). In addition, misunderstanding by other professionals and the community, often fuelled by inaccurate media representations, contribute to new graduates feeling uncertain about their professional identity (Hunt et al., Citation2017). As social workers engage with these inaccuracies their sense of how they are viewed by the community can become distorted, as found in Aotearoa New Zealand where the community perceived social work more positively than social workers expected (Staniforth et al., Citation2016).

Being socialised into the social work profession in the current Australian context is challenging in relation to what Beddoe (Citation2011, p. 26) calls professional capital: “ … the aggregated value of mandated educational qualifications, social ‘distinction’ based in a territory of social practice, and economic worth marked by artefacts of professional status, occupational closure and protection of title”. Because this capital is often contested and social work status challenged (Beddoe, Citation2011; Fotheringham, Citation2017) graduates may identify more strongly with their role description than their professional qualification, values and ethics (Harrison & Healy, Citation2016).

Social work in Australia is currently a self-regulating profession with no requirement for registration to be called a social worker (Fotheringham, Citation2017; Modderman et al., Citation2017). This poses challenges to new graduates and potentially influences their professional capital in contrast to colleagues (particularly in health settings) who must be registered with AHPRA (Fotheringham, Citation2017). This affects new graduates’ confidence and ability to find fit with the social work profession. The recently passed Social Workers Registration Bill (2021) legislates social work registration in South Australia only (yet to be enacted). How this will influence social work in South Australia and Australia more generally is yet to be seen.

Professional Resilience

Resilience can be defined as the capacity to “reframe, adapt, balance, persist and grow in the face of adversity” (Hodges et al., Citation2008, p. 80). This ability to “bounce back” after challenging times is important when navigating and managing work stressors, including high client loads, lack of professional support and vicarious trauma. Vulnerability factors, those “that exacerbate the negative effects of the risk condition”, and protective factors, “that modify the effects of risk in a positive direction”, influence responses to adverse experiences and thus resilience (Luthar & Cicchetti, Citation2000, p. 858). Resilience, and the associated ideas of vulnerability and protective factors, are familiar concepts for social workers, particularly in therapeutic work with clients (Grant & Kinman, Citation2014). Research about professional resilience is also relevant to social workers (Adamson et al., Citation2014; Ashby et al., Citation2013; Collins, Citation2007; Grant & Kinman, Citation2014). Studies exploring resilience with social work students and practitioners in the UK (Grant & Kinman, Citation2014) and New Zealand (Adamson et al., Citation2014), and with occupational therapists in Australia (Ashby et al., Citation2013) all connect strong professional identity with the development of professional resilience. Adamson et al. (Citation2014, p. 530) explored the role professional identity plays as a “mediating factor” in developing resilient practitioners, finding developing a sense of being a social worker is important to becoming resilient. However, to develop a sense of being a social worker, social workers also need to be resilient to challenges to their emerging professional identity. The developmental processes of professional identity development (PID) and professional identity resilience (PIR) are interdependent. There is limited understanding of the challenges faced by new graduates and how PIR develops and supports PID. This article aims to enhance this understanding.

Drawing on findings from a recent Australian study (Long et al., Citation2018), the links between professional identity and professional resilience are explored in this article, the argument being that PIR is a key factor in developing a social work professional identity. The broad research question was: “What are the experiences of professional identity development for social work graduates in the 21st century?” Three sub-questions were: How does the process of professional identity development unfold for social work graduates? What experiences shape the development of professional identity for social work graduates? What does this mean for social work as a profession?

Method

Research Design

This article draws on a PhD study undertaken by the first-named author, which explored the experiences of professional identity development for new graduates in Australia. The second, third, and fourth named authors were supervisors for the study and contributed to the development and reviewing of this article. The study was conducted by the first-named author between 2012 and 2018, using a constructivist grounded theory methodology and methods (Charmaz, Citation2014). Ethics approval was received from the La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee (FHEC12/88).

Sample and Recruitment

Participants were recruited via a flyer emailed to human service organisations and professional networks. The inclusion criteria were being within 2 years of graduation; having no experience in the field prior to commencing social work studies; working in the inner regional area of Victoria or Southern New South Wales, Australia, and availability for two interviews over approximately a 12-month period. Twelve participants met the criteria and agreed to participate. All were women: 5 aged 18–24 years, 2 aged 25–34 years, 3 aged 35–44 years, and 2 aged 45–54 years. Four participants were employed in government organisations and 8 in non-government organisations. Participants ranged from 5 to 20 months post-course completion at the time of the first interview and worked across many fields of practice.

Procedure and Data Analysis

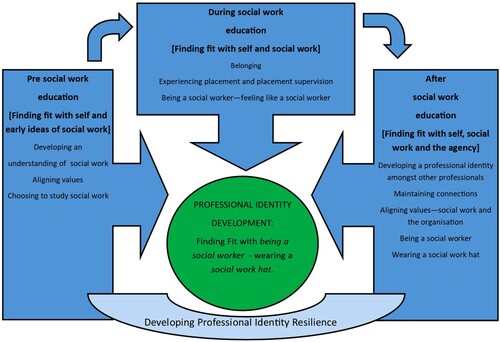

Participants had 2 semi-structured interviews over 18 months by telephone (14) and face-to-face (10). A total of 24 interviews were conducted, audio-taped and transcribed. In line with grounded theory analysis, the process of transcribing and analysing data occurred throughout the data collection phase rather than at the end. Coding techniques of line-by-line coding, constant comparison, memo writing, diagramming, and theoretical sampling (Charmaz, Citation2014) were used, leading to a substantive theory that aids the understanding of graduates’ experiences of professional identity development. The theory is referred to as the Finding Fit Framework (see ). A key factor in this framework is the role of professional identity resilience, the focus of this article.

Findings

Previously we have reported that the process of professional identity development (PID) can be conceptualised as a process of Finding Fit; individuals endeavour to find a fit with self, with their employing agency and with the social work profession (Long et al., Citation2018) as represented in . This framework emerged from the initial results of this study as participants explored their process of adapting to employment as new social work graduates. This process is complex and different for everyone, involving identity construction and reconstruction while interacting with social and professional environments and moving toward a sense of self as social workers (Long et al., Citation2018). There are three key stages: pre-social work education; during education, and post-education, with PID beginning prior to the decision to pursue social work as a career and continuing throughout social work careers. Thus, the experience of finding fit is continuous, with social work professional identity (the fit between self, social work and agency) constantly evolving.

In this article, professional identity development has been explored in relation to how new graduates responded to the challenges to their social work identity and the role of professional identity resilience (PIR); that is, resilience to challenges to their emerging sense of self as a social worker, as a supporting factor to professional identity development. The findings are presented under the key themes of challenges to professional identity development, and responding to the challenges. Pseudonyms are used for participants.

Challenges to Professional Identity Development

Throughout the process of professional identity development, participants faced challenges to their understanding of themselves as social workers and of the social work profession. These included lack of clarity about the identity of the social work profession; lack of professional registration; the absence of social workers in their workplace or networks; the risk of losing social work identity; and social work not being valued in the organisation.

Lack of Clarity About the Identity of the Social Work Profession

Participants commented on lack of clarity about the social work profession, and at times, a limited view of the social work role. To illustrate Amanda explained: “so they have a total misconception. [People] think we just take children away from parents, or we leave children with parents who shouldn’t have them”. Bec reflected on what she saw contributing to this confusion:

Because social workers work in many different fields, whereas if you’re a dentist, you’re a dentist or if you’re a teacher, you’re a teacher … But in social work … there are that many different fields and areas you can work in and maybe that’s what’s confusing for people.

Lack of Professional Registration

The lack of registration and regulation of social workers in Australia emerged as a significant challenge. Participants had mixed feelings about the need for registration but identified registration as having potential for a stronger professional identity. They noted a lack of credibility of the profession, felt challenged when non-social work qualified staff called themselves social workers, and were concerned about limited monitoring of unprofessional behaviour giving social work a “bad name”. Angela said:

They call themselves social workers. I’m a social worker but they’re not … It [registration] will also eliminate some of the practices of some people out in the field who haven’t got the degree, you can see a difference in just the knowledge base, the theory.

Absence of Social Workers in Their Workplace or Networks

Participants identified needing to be around other social workers for professional socialisation. However, this was challenging when not working alongside other social workers. The absence of social work staff is intensified in rural and remote practice settings making it difficult for participants to experience professional connectedness. Rachael and Emma commented on the absence of connections contributing to feeling “isolated”.

I think the first year out has been a lot harder than what I thought it would be … even the peer support, when I did placements and where I’ve worked in [the city], they had, like designated peer support groups whereas up here there’s nothing, so I think that just for me has added to being isolated. (Rachael)

The rural/regional aspect also meant limited access to social work supervision and professional development. Bec’s experience of supervision with a non-qualified social worker left her feeling uncertain about social work: “I can imagine if I was there [at the agency] for another year I might have just thought well, is this social work? … Well, if it is, I don’t want to do this”.

Risk of Losing Social Work Identity

The risk of losing their social work identity was highlighted, particularly in workplaces not sharing social work values. Amanda said it was important to: “not [lose] sight of the ethics and … our work around empowering and the human rights … which I think are quite specific to social work … I’m in an organisation that doesn’t care about that at all”. For those in multidisciplinary contexts, the risk is heighted with positions not identified specifically as social work roles: “you can find yourself losing a bit of your identity because there’s so many different professionals and you’re all doing the same job” (Sarah).

Social Work not Valued in the Organisation

Professional hierarchies and organisational role constraints that made it difficult to perform social work roles meant participants felt social work was not valued. Angela commented:

Being a social worker in my mind gives you a lot more flexibility and creativity in how you work with people … the role … I do, doesn’t allow for that. There’s lots of things in the [Agency] role I don’t like, which don’t feel like social work to me. So, I’m a bit conflict[ed] lately.

Amanda’s comment highlights the potential risk for new graduates

I think building resilience in your graduates is pretty important. But to some people who don’t do that [develop resilience] the organisation can really get them down … I think you have to have pretty tough skin sometimes as a social worker from that point of view to be able to keep pushing.

Responding to the Challenges

Encountering these challenges created uncertainty, participants needed to rethink and reinterpret themselves as social workers, dealing with challenges differently. Anna grappled with her understanding of social work and challenged others’ perceptions. In contrast, Sarah struggled to explain social work, calling herself a youth worker because she believed people found it easier to understand the role. Similarly, Molly said:

I guess the biggest problem is that it’s really hard to define a social worker … I found it really good that I was able to tell people and they were actually open to listening about what we were doing.

The way participants resolved identity challenges significantly influenced their understanding of themselves as social workers, but required a certain kind of resilience as Amanda identified: “I just think going towards resilience … to be able to develop social work professional identity, it’s got to be extraordinarily internally driven, particularly when you are remote”.

Participants identified the following seven protective factors that supported them when navigating challenges to their professional identity development: leaving university with a clear understanding of what social work is to them; being supported by “good” supervision (not always needing to be with a social worker); being able to socialise with other social workers; social work values aligning with the organisational values; being “proud” to be a social worker; having confidence in social work skills and knowledge; and being able to recognise the “fit” with their agency is not right for them. These are explored further below.

Leaving University with a Clear Understanding of What Social Work is to Them

Graduating with a clear personal understanding of the meaning of social work proved a key factor in navigating organisational misunderstandings about social work. First, graduates need clarity about the purpose of social work, for beginning practice conversations when their social work identity is questioned. Second, graduates need an internal sense of what it means to be a social worker. For example, quite early in her employment, Anna was told not to refer to herself as a social worker. Anna had a very clear social work identity and confidently “pushed back” about this, which resulted in her being able to use the title “social worker”.

Being Supported by “Good” Supervision (not Always Needing to be with a Social Worker)

Participants connected “good” supervision with developing their social work professional identity, where they could express uncertainty without fear of repercussion, that was accessible and regular, and where supervisors modelled social work values and discussion extended beyond the caseload. At times participants struggled to make sense of being a social worker when good supervision was unavailable. Angela considered paying for external supervision because her current supervision was about her work but not about her social work identity.

Being Able to Socialise with Other Social Workers

Being connected with other social workers contributed to participants’ socialisation into the profession and professional identity resilience. When social workers were absent in their immediate teams, participants found other ways to stay connected. Bec suggested “unless you are surrounded by social workers—you’re not going to be socialised as a social worker”. For Amanda, staying connected with peers and university lecturers meant feeling connected to the social work profession, despite being in an organisation where social work professional identity “doesn’t really exist”.

Social Work Values Aligning with the Organisational Values

Alignment between social work values and organisational values was an important protective factor for participants. Where this was absent or less clear there was greater difficulty in maintaining their social worker identity. Building resilience to mitigate challenges to values in organisations was seen as important by Amanda, as noted above, and Bec who “pushed back” when she was challenged by her supervisor who told her that psychologists, not social workers, do “counselling”, even though this was part of her job description.

Being “Proud” to be a Social Worker

Pride in being a social worker assisted participants to develop their social work professional identity. This was particularly important when they experienced misunderstandings about social work from other professionals. When participants were less sure about being a social worker their professional identity was negatively affected. When they were overtly proud, they managed the misunderstandings in a more positive way, reaffirming their social work identity. Anna noted:

I’ve worked hard to get that qualification and I’m proud of being the social worker, and as family support worker, I could actually be other disciplines and I want to be distinguishable as a social worker, and it is again, about that identity.

Having Confidence in Social Work Skills and Knowledge

Confidence in social work skills and knowledge was important for helping participants understand how social work fitted with their organisation and for developing their social work identity. Participants’ confidence in their skills and knowledge varied when they left formal education, but they identified a shift during the course of the interviews. By the second interview, Sarah had moved from referring to herself as a “youth worker” to proudly calling herself a social worker. Likewise, Kate was now confident to “bring it up and talk about it [social work] and share it”.

Being Able to Recognise the “Fit” with Their Agency is not Right for Them

Being able to recognise when the fit is not quite right or has changed is an important protective factor. Participants experienced times when they felt the fit with their agency was not right for them as social workers, which also led them to question their fit with social work. Through this questioning, they reaffirmed their fit with social work and lack of fit with their agency. The ability to reflect on “fit” was, itself, a protective factor. Without this, graduates may experience doubt about their own understanding of social work, leading to a narrowed social work professional identity or graduates leaving the profession. Angela commented,

I hope I don’t [lose my sense of being a social worker]. Maybe it’s good to check in with other people to get a sense of whether maybe it’s time to move on to something else … if that’s what you really want to be doing—social working.

Discussion

The differing responses to challenges led to exploring why some participants seemed more confident about their social work identity than others—and what emerged was the concept of professional identity resilience (PIR). PIR can be understood as graduates’ abilities to bounce back when faced with a challenge to their social work professional identity, to adjust and/or adapt to the challenge and at the highest point, to confront and change the circumstances that led to the challenge.

Resilience is a response or outcome to an adverse event or risk situation seen in the responses by people affected and developed in response to an adverse event. When challenging experiences occur, resilience is both tested and developed. Aspects of resilience, such as positive self esteem, a belief in skills and knowledge, self reflection, and problem solving skills, can be taught and role-modelled (Grant & Kinman, Citation2014) to prepare graduates for challenges to their social work identity. However, to develop resilience people need to be exposed to challenges. We call these professional identity resilience-building moments. The participants’ responses to these both tested and developed their PIR.

Participants’ experiences demonstrated there are protective factors that support positive development of PIR, that is factors “that modify the effects of risk in a positive direction” (Luthar & Cicchetti, Citation2000, p. 858). These include elements internal to graduates (for example, how they feel about being a social worker) and external resources (for example, supervision). As noted above, seven key protective factors assisted graduates to develop professional identity resilience. Similar factors have been identified by previous research. For example, Wiles (Citation2013) found that graduates need to develop an internal sense of what it means to be a social worker for professional identity development. While this is unique to each person, the sense of being a social worker forms a base from which to compare discourses about social work identity. However, when students become aware of this identity work varies. On leaving university, participants in this study varied in their clarity of being a social worker. Smith et al. (Citation2022) found social work students on placement in the mental health sector noted the challenges of developing a clear social work identity. However, Ashby et al. (Citation2013) found occupational therapists in similar settings who felt clear about the distinctive nature of their discipline were better able to navigate challenges to identity when working with other professionals but reported feeling most vulnerable to losing this clarity in the transition from student to graduate.

Participants in our study highlighted the importance of good supervision in developing professional identity resilience. This finding is consistent with broader research (Adamson et al., Citation2014; Ashby et al., Citation2013). Maintaining professional connections was found to be key to professional resilience by Ashby et al. (Citation2013), Adamson et al. (Citation2014), and Kinman and Grant (Citation2017), and staying connected with social workers is significant for professional socialisation (Miller, Citation2010) providing opportunities to discuss professional identity. Previous professional resilience research reinforces the importance of organisational value congruence (Adamson et al., Citation2014; Ashby et al., Citation2013; Kinman & Grant, Citation2017). Professional pride is connected to self-efficacy, confidence and a belief in the values of the profession (Adamson et al., Citation2014; Ashby et al., Citation2013) and to being resilient to challenges to professional identity (Ashby et al., Citation2013). Similarly, Ashby et al. (Citation2013, p. 115) found “knowing when to go” was important to maintaining professional identity.

The presence of these protective factors positively influenced the development of professional identity resilience (PIR) and the participants’ ability to navigate challenges to their social work identity. For example, as Sarah’s confidence in her social work skills and knowledge grew, she moved from calling herself a youth worker to social worker.

The development of professional identity resilience (PIR) as core to the development of professional identity and resilient practitioners, emerged from this research, building on Adamson et al.’s (Citation2014) framework for understanding social work resilience. While their research participants had longer experience in social work, they identified “mediating factors” that “underpin the sustainability of resilient practice” (Adamson et al., Citation2014, p. 530) including the place of self, influence of the organisational context, and professional identity. Clearly a level of professional identity resilience is needed to sustain emerging professional identity while the sense of being a social worker is clarified and consolidated. Once established, identity becomes a mediating factor, using Adamson et al.’s (Citation2014) terms, for engaging with future challenges. The way participants in this current research responded to the challenges to their social work identity can be understood as professional identity resilience-building moments that create opportunities for learning and development in relation to professional identity. However, a focus purely on assisting individuals to become more resilient will not address the larger issues faced by social workers in the sector (Grant & Kinman, Citation2014). The development of PIR is a collective responsibility, as discussed below.

The Role of Social Work Educators

Findings from the present study highlight the important role social work education plays in developing professional identity resilience (PIR). Educators need to give attention to the skills and resources that aid development of resilient behaviours, specifically in relation to professional identity. The current neoliberal and resource restricted climate poses some inherent challenges for social workers’ professional identity development. Social workers, particularly new graduates, may feel powerless and less resilient because of organisational constraints in the neoliberal context or because, like their clients, they internalise being perceived as having less worth or agency (Stewart & Fielding, Citation2022). Nevertheless, formal professional education can promote clarity regarding professional role and identity (Barretti, Citation2004; Miller, Citation2010; Smith et al., Citation2022). Actively exploring social work identity with students and building expectations of managing challenges to professional identity throughout their career are important. Social work academics can contribute positively to the development of students’ PIR when they actively encourage realistic expectations about the human service sector, constructively share stories about their own PID, role model social work values and ethics, and exhibit pride in their own social work identity, so fulfilling this role in the professional socialisation process. Field education is an ideal opportunity for students to articulate, practice, and reflect on building their professional identify development and assess their levels of resilience. In addition, incorporating explicit PIR-building moments into curriculum, (e.g., via case-study reflections, workshop activities), and encouraging rich discussions about social work identity, for example, through the use of the Social Work Hat metaphor (Long et al., Citation2018) can embed PIR into social work education.

The Role of the Profession

Like social work educators, qualified social workers and professional associations also have a responsibility to build professional identity resilience. Positive role modelling, sharing stories of social work identity development and providing opportunities for students and graduates to discuss their social work identity are ways to support identity work. Qualified social workers supporting student placements can provide opportunities for students to articulate, practice, and reflect on developing their professional identity and assess their levels of resilience. In addition, to address the broader misconceptions about social work, professional associations have a role in improving the narrative about social work in the community. In Australia, achieving social work registration or regulation would significantly assist in role clarity.

The Role of Students and Graduates

Students and graduates are not passive in their professional identity development (Beddoe, Citation2011; Harrison & Healy, Citation2016; Miller, Citation2010) and are thus not passive in their development of professional identity resilience (PIR). Identity work occurs during and post-education with frameworks, such as the Finding Fit Framework mentioned earlier in this article, providing ways for students and graduates to purposefully reflect on the PID process and their role in this. By considering the potential challenges and seeing these as PIR-building moments, students and graduates can also reframe a potentially negative experience into a learning opportunity, enhancing PIR as they navigate inevitable changes to roles, organisations, and contexts across their career.

Study Limitations

The concept of professional identity and development are of interest to a wide range of professions. However, the all-female participant population of this study had a specific geographical location limiting generalisability of the findings. It is also acknowledged that cultural identity and context were not addressed and further research exploring the role of culture will be important.

Conclusion

Professional identity resilience (PIR) emerged as a key concept in a grounded theory study that explored the experiences of professional identity development for graduate social workers in regional Australia. Social work graduates experienced challenges as they developed their professional identity, including uncertainty about the role and place of social workers in the field. However, actively reflecting on the process of professional identity development and, specifically, the development of professional identity resilience, and building professional identity resilience protective factors, positions social workers to be proud professionals and to navigate identity challenges.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adamson, C., Beddoe, L., & Davys, A. (2014). Building resilient practitioners: Definitions and practitioner understandings. British Journal of Social Work, 44(3), 522–541. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs142

- Ashby, S., Ryan, S., Gray, M., & James, C. (2013). Factors that influence the professional resilience of occupational therapists in mental health practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60(2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12012

- Barretti, M. (2004). The professional socialization of undergraduate social work students. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 9(2), 9–30. https://doi.org/10.18084/1084-7219.9.2.9

- Beddoe, L. (2011). Health social work: Professional identity and knowledge. Qualitative Social Work, 12(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325011415455

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Collins, S. (2007). Social workers, resilience, positive emotions and optimism. Practice, 19(4), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503150701728186

- Fotheringham, S. (2017). Social work registration: What’s the contention? Australian Social Work, 71(1), 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2017.1398264

- Grant, L., & Kinman, G. (2014). What is resilience? In L. Grant & G. Kinman (Eds.), Developing resilience for social work practice (pp. 16–30). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Gray, M., Dean, M., Agllias, K., Howard, A., & Schubert, L. (2015). Perspectives on neoliberalism for human service professionals. Social Service Review, 89(2), 368–392. https://doi.org/10.1086/681644

- Harrison, G., & Healy, K. (2016). Forging an identity as a newly qualified worker in the non-government community services sector. Australian Social Work, 69(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2015.1026913

- Healy, K. (2015). Becoming a trustworthy profession: Doing better than doing good. Australian Social Work, 70(Suppl. 1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2014.973550

- Hodges, H., Keeley, A., & Troyan, P. (2008). Professional resilience in baccalaureate-prepared acute care nurses: First steps. Nursing Education Perspective, 29(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/00024776-200803000-00008

- Hunt, S., Tregurtha, M., Kuruvila, A., Lowe, S., & Smith, K. (2017). Transition to professional social work practice: The first three years. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 19(2), 139–154. https://hdl.handle.net/10289/11665

- Kinman, G., & Grant, L. (2017). Building resilience in early-career social workers: Evaluating a multi-modal intervention. British Journal of Social Work, 47(7), 1979–1998. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw164

- Long, N., Hodgkin, S., Gardner, F., & Lehmann, J. (2018). The social work hat as a metaphor for social work professional identity. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 20(2), 115–128. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/aeipt.222500

- Luthar, S., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 857–885. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400004156

- Miller, S. (2010). A conceptual framework for the professional socialization of social workers. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 20(7), 924–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911351003751934

- Modderman, C., Threlkeld, G., & McPherson, L. (2017). Transnational social workers in statutory child welfare: A scoping review. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.07.022

- Moorhead, B., Bell, K., & Bowles, W. (2016). Exploring the development of professional identity with newly qualified social workers. Australian Social Work, 69(4), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1152588

- Oliver, C. (2013). Social workers as boundary spanners: Reframing our professional identity for interprofessional practice. Social Work Education, 32(6), 773–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2013.765401

- Papadopoulos, A. (2022). Social work after Tehan: Reframing the scope of practice. Australian Social Work, 75(4), 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1874032

- Payne, M. (2006). Identity politics in multiprofessional teams: Palliative care social work. Journal of Social Work, 6(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017306066741

- Pullen Sansfaçon, A., & Crête, J. (2016). Identity development among social workers, from training to practice: Results from a three-year qualitative longitudinal study. Social Work Education, 35(7), 767–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2016.1211097

- Sharpless, J., Baldwin, N., Cook, R., Kofman, A., Morley-Fletcher, A., Slotkin, R., & Wald, H. S. (2015). The becoming: Students’ reflections on the process of professional identity formation in medical education. Academic Medicine, 90(6), 713–717. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000729

- Smith, F. L., Harms, L., & Brophy, L. (2022). Factors influencing social work identity in mental health placements. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(4), 2198–2216. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab181

- Staniforth, B., Deane, K., & Beddoe, L. (2016). Comparing public perceptions of social work and social workers’ expectations of the public view. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 28(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol28iss1id112

- Stewart, C., & Fielding, A. (2022). Exploring the embodied habitus of early career social workers. Australian Social Work, 75(4), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1980070

- Wallace, J., & Pease, B. (2011). Neoliberalism and Australian social work: Accommodation or resistance? Journal of Social Work, 11(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017310387318

- Wiles, F. (2013). ‘Not easily put into a box’: Constructing a professional identity. Social Work Education, 32(7), 854–866. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.705273