ABSTRACT

Adverse prenatal diagnoses, regardless of the women’s choice of continuing the pregnancy or terminating it, can impact a women’s psychological and psychosocial wellbeing. Supportive interventions during this time are important. However, understanding what is deemed useful and best practice is complex and multifaceted. To understand the need for support during this time, the authors undertook a research study where 12 women were interviewed. The women spoke about feeling pressured by time in making a decision regarding their pregnancy option and having limited psychoeducation and support provided. They also spoke about post-traumatic growth in their grief experience. To assist health professionals, the authors have addressed the following areas in the study’s findings and discussion sections: the lack of appropriate information delivery skills of the professionals, the need for an assessment of each woman’s unique needs, the need for appropriate referrals to be given, and the need for appropriate follow-ups of the women. The SARF (Skills, Assessment, Referral, and Follow-up) model, presented in this article as a synthesis of this research, has the potential to inform the development of clinical services and social work practice to support women’s care following adverse prenatal diagnosis.

IMPLICATIONS

Psychosocial assessments are vital in providing good quality care to women after a poor prenatal diagnosis.

The model can provide guidance to ensure that psychosocial assessments and explorations of values are undertaken before referring women to follow-up services.

Given social workers’ experience in providing psychosocial assessments and their recommendations, social work clinicians should be utilised in health settings to their full scope of practice.

KEYWORDS:

The prenatal period can be an anxious time for women concerned about the health and wellbeing of their unborn child. While undertaking prenatal diagnosis testing can be important for women’s peace of mind, around 3% of them will receive an adverse prenatal diagnosis. This diagnosis often leaves them shocked and overwhelmed as to how to manage this information and how to deal with all the available options (Abeywardana & Sullivan, Citation2008; Azri et al., Citation2014; Carlsson et al., Citation2016; Hogan, Citation2016; Kersting et al., Citation2009; Korenromp et al., Citation2007; Leithner et al., Citation2002; McKechnie & Pridham, Citation2012). An adverse prenatal diagnosis as the result of prenatal screening can occur at any stage of pregnancy and has long-term, complex implications. This is especially the situation when women are faced with the choice of whether to continue or terminate their pregnancy. It can also deepen the risk of long-term psychiatric, emotional, and social problems (Azri et al., Citation2014; Carlsson et al., Citation2016; Irani et al., Citation2019; Kersting et al., Citation2009; Korenromp et al., Citation2007; Lathrop & Van De Vusse, Citation2011). With the growth in the prenatal screening technology available, there are now increasing numbers of women receiving adverse prenatal diagnoses. This includes women whose pregnancies were considered low risk. Consequently, they are faced with the trauma of receiving the poor outcome as well as the responsibility of choosing their pregnancy option (termination or carrying their baby to term) (Bui et al., Citation2013; Hawthorne & Ahern, Citation2009; Hogan, Citation2016; Lafarge et al., Citation2013; Pitt et al., Citation2016).

Many studies have suggested that psychosocial support during this time may be of benefit to these women (Azri, Citation2017; Azri et al., Citation2014; Bijma et al., Citation2007; Blakeley et al., Citation2019; Brown et al., Citation2022; Kang, Citation2020; Thomson & Downe, Citation2016; Watson et al., Citation2021). There is little information about the kind of support women receive at the time of prenatal screening, particularly when there is a poor diagnosis (Hutti, Citation2005; Irani et al., Citation2019; Kang, Citation2020). The development of psychosocial supports that focus on prenatal testing have not progressed as fast as the current technological developments. There are still no clear national guidelines about what would benefit women in these situations from a psychosocial point of view (Hardisty & Vora, Citation2014; Hogan, Citation2016; Kang, Citation2020). As a result, many women, their families, and staff are poorly prepared to manage the psychosocial consequences that may arise postdiagnosis (Blakeley et al., Citation2019; Brown et al., Citation2022; Kang, Citation2020; Thomson & Downe, Citation2016; Watson et al., Citation2021).

Findings published elsewhere from the questionnaire phase of this study highlighted that women’s perception of support was more important than the type of support they received (Azri, Citation2017). It is important for women and the health professionals working with them to understand the care required after an adverse result (Pisnoli et al., Citation2016). The aim of this Australian study was to explore women’s experience of care after an adverse prenatal diagnosis, specifically the impact of the support provided on their anxiety, decisional conflict, and guilt levels. The research question of the qualitative part of the study examined the impact of psychosocial support on women’s wellbeing after an adverse prenatal diagnosis, specifically how helpful their support options had been at the time of their diagnosis.

Methods

Research Design

Due to the traumatic nature of the study, information on how to access psychological support, and a clear outline of the potential risks of the research were prepared. Furthermore, as the main researcher was a qualified mental health clinician and psychotherapist, appropriate interview steps such as identification, management, and de-escalation of acute distress were a strong focus of the interviews. One participant became distressed during her interview. Therefore, the interview was immediately terminated with an opportunity for a debrief provided as well as a follow-up phone call the next day. No further action was required based on the participant’s own feedback.

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited through loss support groups and word of mouth in Australia via online support groups and social media. The selection demographics were open to women of any age, any ethnicity, and any pregnancy option. Consenting women were sent an information pack as well as questionnaires about their experiences. While the results of these questionnaires are reported elsewhere, the findings showed that the women’s experiences were very subjective based on how their care matched their personal values rather than based on what support was offered (Azri, Citation2017). A subset of this group indicated their willingness to participate in an in-depth interview. Interviews are generally used to generate narratives that focus on individual experiences and preserve the subjective voices of participants’ lived experiences (Crabtree & Miller, Citation2022; Creswell, Citation2018). Twelve women were selected based on the timing of the return of a survey and whether they had a medical termination or had carried to term. All had received their prenatal diagnosis in the five years prior to the interview. Six women had continued their pregnancy to term while the other six had chosen a termination. The diagnoses were varied and included trisomies, cardiac anomalies, spina bifida, and brain abnormalities. Each participant was given a pseudonym to protect their identity. The qualitative interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

The qualitative data from the interviews was analysed using thematic analysis involving the clustering of specific themes (Nowell & Moules, Citation2017). Specifically, deductive thematic analysis was chosen as a natural progression from the quantitative part of the study, which highlighted that lack of adequate support seemed to have impacted adversely on the women’s wellbeing greatly (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). The initial analysis involved the line-by-line coding of individual text into similar categories. These categories were then regrouped into themes. All transcripts and their initial coding were emailed to participants to clarify the accuracy of their intended meaning and to confirm whether the researcher had captured the information. The data was then recoded with these themes and the first author (SA) and third author (JC) checked and discussed the themes extracted from the analysis for confirmation. The research was part of a PhD at Griffith University from 2012 to 2017 and received ethics approval (Griffith University Ethics #6507).

Findings

Overall Experience of Receiving the News

For these women, their journey had been very traumatic. While little could have prepared them for the shock of the diagnosis, their experiences were negatively heightened because they did not feel ready for the possibility of bad news. They described that the medical staff had not adequately warned them of this possibility and they felt poorly equipped for the process, from testing to the decision-making about giving birth or having a termination. Teresa and Zia described their experience as following:

I think professionals should tell people that scans are medical procedures. I think that is an important thing. I was this 28-year-old naive person going into it, thinking “oh, I get to see my baby” and I walk out of there being told my baby could die. My naivety had been ripped away from me. I remember walking out of there in tears. (Teresa)

We had received an abnormal result and wondered what on earth is happening. (Zia)

With [name of hospital], they needed to have more information for you to take home. They need to understand these sorts of diagnosis come as quite a shock and a lot of information they tell you at the time just doesn’t sink in. You are just in a complete state of shock. They needed to either have a follow-up appointment in a few days and go through it again or give you a lot of material that you could take home and read at your leisure. A follow-up appointment would have been really good to talk about it again and go over it again. (Nora)

I mean I suppose there are things they could have said to me like “how are you going?”, “have you been to a support group?”, [and] “do you want me to give you details of that?”—anything like that. I’ve had to chase up everything that I needed myself. (Zia)

Impact of Time Pressure

Women described experiencing extreme time pressure around the decision and timing of the termination of the pregnancy. Women stated that this pressure had made their experience of decision-making very difficult as they experienced feelings of shame and guilt. They added that removing the time pressure would have positively impacted on their experience and the processing of the news.

My obstetrician was … I think she was putting pressure on me … She said, “You need to decide in the next two days, because it takes a week or so to organise, so you need to decide … ” I felt like … I wish I had more time. (Tess)

They were sort of saying that I could have a termination, but that I needed to let them know today. (Esther)

Appropriate Referrals

A very strong theme was the lack of referral to appropriate psychosocial supports. Ten of out twelve participants interviewed stated they did not receive any referral of any type. The other two participants described only receiving support that they proactively had sought themselves.

I had nothing … I didn’t get so much as a pamphlet to read or anything … nothing. I got given nothing. (Tess)

Nothing and I’m still bitter about it … I think I needed someone to actually physically come up to me. (Tarryn)

Staff Approaches and Accessibility of the Delivered Information

The location and the manner in which the news was delivered to the women by the healthcare professionals was described as less than ideal. For most of the women interviewed, they received their prenatal diagnosis news in a medical/clinical setting. Two participants reported receiving this very difficult news with little privacy (in hallways or at their bedside). One was told the news in a public waiting room. The following woman explained how she had received fatal news about her baby born a few days earlier while she was in a shared room next to another patient who had visitors.

The cardiologist and the head pediatrician came to speak to me. I was in a shared room with another woman. They were all just chatting among themselves as this guy was trying to give me news on my child. And we couldn’t hear, couldn’t understand. We were so damned confused. He [pediatrician] told me, “This is the condition, this is what is going on, do you still want us to treat him [the baby]?” (Tarryn)

Impact of Terminology

The language used was, in part, a major barrier due to medical “jargon” and “clinical” descriptions. Most women used words such as “unfamiliar”, “inappropriate”, and “cold” to describe the way the news was delivered. Except for one person, all described how they did not understand the type of tests conducted, the results, or the consequences of the tests. The language used to explain these test results was described as too complicated. The participants described how they were unfamiliar with the diagnosis their child had received and that the wording used by the treating team did not make any sense to them. They were in a state of shock, which did not allow them to take in the information provided. The state of shock was often compounded by the fact that as they were not in a risky age group, their pregnancy had been deemed at low risk. In addition, the women described a lack of confidence in asking for clarification, in challenging the treating team’s prognosis, and in asking for options or to assertively express their needs.

The doctor came back in about five minutes later and I will never forget his words … “This is not good news. There is something wrong with your baby.” He told me my baby had likely Trisomy 21 and to consider my options … But I didn’t even know what Trisomy 21 was, nor did I think to ask. (Zena)

We were getting a biology lesson really, telling us how the heart works and it just went over my head. My husband thankfully understood it and he would reword it for me so that I understood. That’s not really the doctor’s fault; they are talking what they know. They did draw a few diagrams, but they can be a bit frustrating when you are not really understanding what they are trying to say. (Tarryn)

We had good support from our consultant. One of the really nice things she did was she actually referred to the baby as baby, didn’t say it was a fetus or, you know, a lot of other doctors I know do. She always referred to [the] baby as baby, so he had an identity, and he was a person and all that, which was comforting. (Zia)

Discussion

The women interviewed highlighted different concerns. Some described how they felt unprepared for the testing process and results. The way the news was given to them, and the attitudes of the professionals were described as inappropriate. Similarly, the options and information about the process provided were limited. The decision-making phase following a prenatal diagnosis was experienced as pressured. There were additional concerns around the care provided after receiving a prenatal diagnosis. Many described the resources provided as inadequate and that there were not appropriate linkages with support or ensuring that these supports were in place before discharge from the service. The lack of psychosocial assessments and lack of exploration of values and beliefs prior to offering options were one of the biggest reasons women’s referrals were described as inappropriate. This study emphasises the need to consider the psychosocial circumstances of the women after an adverse prenatal diagnosis and the need for individualised support (Blakeley et al., Citation2019; Brown et al., Citation2022; Kang, Citation2020; Thomson & Downe, Citation2016; Watson et al., Citation2021).

Participants in this study described what they had perceived as helpful and unhelpful during their care. According to the interview transcripts, the term “helpful” was associated with nonjudgmental attitudes of professionals, family, and friends, regardless of the women’s pregnancy choice and outcome. Additionally, the term “helpful” was associated with the validation of the women’s losses and of their experience of empathy and support.

Despite a significant amount of negative feedback, participants emphasised that positive experiences made a significant difference to their wellbeing and their healing process. These experiences included warm interactions with professionals, sufficient time to discuss their case, adequate and appropriate interview spaces to facilitate necessary discussions, and active referrals to tailored support groups or counselling. Many of these positive interactions were achieved through obstetric case management, access to appropriate and specific support groups, provision of appropriate literature and resources, and ongoing emotional and practical support after discharge. Women in the study noted some beneficial interventions that had been offered to them. Those interventions included the translation of medical information into simple language, objective and nonjudgemental support, and referrals to practical assistance and support groups and external organisations. These interventions have been noted in other studies (Bijma et al., Citation2007; Brown et al., Citation2022; Carlsson et al., Citation2016; Hutti, Citation2005; Kersting et al., Citation2009; Korenromp et al., Citation2007; Leithner et al., Citation2002; Watson et al., Citation2021).

The women highlighted the vital nature of clinical support, including the need to clearly establish what would be of greatest benefit to them when responding to an adverse prenatal diagnosis. Issues such as previous trauma, levels of social support, personal vulnerabilities and preferences, values and perceptions about pregnancy and pregnancy choices, as well as the severity of the prognosis impact on the type of support offered (Azri, Citation2017; Brown et al., Citation2022; Watson et al., Citation2021). Further, the timing of the assessment and the environment in which the assessment is made is of significance. Pregnancy decisions are complex, and these complexities need to be acknowledged before a practitioner can adequately assess the woman’s psychosocial needs and the type of support that may be of benefit (Pitt et al., Citation2016). Factors such as psychosocial histories, experiences, opinion, values, rights, legal options, family support, spiritual beliefs as well as cultural and political influences need to be considered when offering support options to women (Pitt et al., Citation2016). In particular, women may face conflicting thoughts while making their decision following a poor prenatal diagnosis. Their decision may not correspond with their values, family wishes, or coping abilities. The women interviewed in the study clearly articulated that a supportive intervention was one that considered their set of unique circumstances in a genuine way as opposed to offering a standardised service.

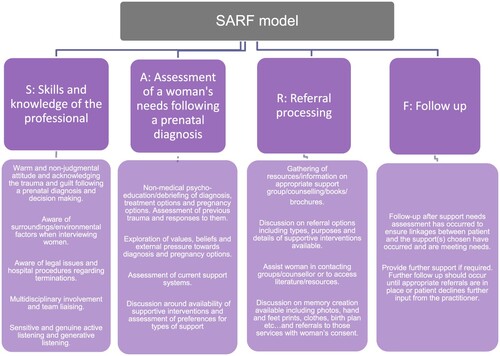

Implications for Practice: The SARF Model

The qualitative findings highlight core domains for health care professionals to consider. We have collated these domains into four main areas:

skills and knowledge of the professionals providing care to women (S)

assessment of women’s psychosocial needs (A)

referral (R)

follow-ups (F).

Skills and Knowledge

The first component of the model (S) encapsulates the skills and knowledge of the professionals who are providing care to the women and who are required to interact with the women and their families. This component is not only about technical skills but about how professionals interact with their patients. It is critical to be warm and compassionate when providing women with essential information about the accessible array of psychosocial services. While the content of the interaction may be medical, these discussions are emotionally charged, and it is critical to focus on both.

Assessment

The second part of the model advocates for a distinct appraisal of the women’s needs (A). This assessment needs to be comprehensive and include a psychosocial assessment as well as the identification of appropriate and individualised support. Meeting the women’s subjective needs will provide validation of the experience and expand the health team’s knowledge of suitable support services. For instance, a woman’s values and her psychosocial situation and needs may completely change the landscape of what the woman may benefit from.

Referral

The third aspect of the SARF model centres on referral management after an adverse prenatal diagnosis (R). Clinicians will need to be aware of supports available to address some of these needs. These supports can include support groups and supportive literature or services that offer memory creation. It is important to develop individually tailored support plans that are tailored to the women’s needs to ensure that women receive appropriate care.

Follow-up

Finally, the last dimension of the proposed model concerns Follow-up (F). Professionals will need to ensure that women are appropriately connected to necessary support. It is critical that the clinicians organise warm handovers as many women are overwhelmed, anxious, or simply too distraught to be able to contact these organisations themselves. This suggests that there is a need to facilitate this referral process (with the woman’s consent) to ensure further access to support.

SARF and the Role of Social Workers

The framework has the potential to provide a guide for healthcare professionals to meet women’s needs at various points of their adverse prenatal diagnosis journey. The model highlights the importance of exploring women’s values and existing support networks as well as identified requirements. It is critical to conduct a psychosocial assessment of needs that includes referrals and follow-ups to meet the patients’ specific needs. The SARF model draws from the experiences of women in this study and creates a speculative, yet coherent, framework available for adoption by social workers and other health professionals working with women after an adverse prenatal diagnosis. The key features of the model facilitate its ability to support women in a way that acknowledges their unique psychosocial needs, as is supported in the literature (Brown et al., Citation2022; Thomson & Downe, Citation2016; Watson et al., Citation2021). This study established that women require specific support that is warm, nonjudgmental, and provided by professionals aware of a wide range of available support services. It emphasised that referral to services should occur following a thorough psychosocial assessment to allow women’s unique values and circumstances to direct the referral process. The authors advocate the need for women to receive follow-up care until appropriate community support services have been accessed. However, knowledge translation often fails when implementing such findings into practice when there is a lack of understanding of the complexities involved in each situation (Graham et al., Citation2006; Harvey & Kitson, Citation2016). Social workers are trained to identify these practical and contextual risks, and their expertise in biopsychosocial assessments places them in an ideal position to implement this clinical model. Further, social work practice allows social workers to recognise the feedback and needs of women who find themselves in these adverse prenatal situations, while recognising the need to consider the context in which the model could be implemented.

When providing support to women experiencing a birth trauma, healthcare professionals need to remember that there is a multifaceted interplay of values, religion, family, and societal systems that need to be considered along with prenatal diagnoses and decision-making processes (Azri et al., Citation2014; Brown et al., Citation2022; Thomson & Downe, Citation2016; Watson et al., Citation2021). Importantly, this work also needs to be informed by the social work values of client self—determination and client advocacy with a strong focus on psychosocial—and solution-focused interventions (AASW, Citation2013; Azri et al., Citation2014).

Limitations

There were limitations to the study, which included the need to rely on the recollection of events from up to five years ago. In contrast, some of the participants had experienced their diagnosis in the last 12 months and, as result, might have been more emotionally vulnerable, which may have impacted on their perception of care.

Conclusion

There have been significant technological and medical advances that allow for prenatal diagnosis testing. With these advances, however, a range of complex ethical issues have arisen. The experiences of the women highlight that while an adverse prenatal diagnosis is a medical event, it is important to incorporate matters such as grief after an adverse prenatal diagnosis and neonatal loss. It is critical that health workers who work in the area of prenatal testing are skilled and prepared to care for women in a considerate, nonjudgmental manner in a way that is well supported by social work values. Supportive interventions that facilitate informed unhurried, decision-making by the women involved and provide short—and long-term psychosocial interventions may assist in the women’s recovery or adaptation after an interruption of their pregnancy, the death of their child, or the birth of their baby with a disability. The SARF model provides a framework for health and social work professionals to explore and address various issues.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr Wyder’s never-ending enthusiasm and wisdom in working on this article, which served to make it stronger and of publishable standard. Dr Cartmel and Dr Azri would also like to acknowledge the women who participated in this study. It is our goal that their brave testimonies will assist in providing better support for other families who receive adverse prenatal diagnoses as well as for the staff working with them.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abeywardana, S., & Sullivan, E. (2008). Congenital anomalies in Australia 2002–2003 (Vol. 3). AIHW National Perinatal Statistics Unit.

- Australia Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2013). AASW social work practice standards. Author.

- Azri, S. (2017). Prenatal diagnosis and support: A study on the impact of psychosocial support and women’s wellbeing [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Brisbane: Griffith University.

- Azri, S., Larmar, S., & Cartmel, J. (2014). Social work's role in prenatal diagnosis & genetic services: Current practice & future potential. Australian Social Work, 67(3), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2013.848914

- Bijma, H., Van der Heide, A., & Wildschut, H. (2007). Decision-making after ultrasound diagnosis of fetal abnormality. European Clinics in Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 3(2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11296-007-0070-0

- Blakeley, C., Smith, D., Johnstone, E., & Wittkowski, A. (2019). Women’s lived experiences of a prenatal diagnosis of fetal growth restriction at the limits of viability. Midwifery, 76(1), 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.05.015

- Brown, A., Nielsen, J. D. J., Russo, K., Ayers, S., & Webb, R. (2022). The journey towards resilience following a traumatic birth: A grounded theory. Midwifery, 104, 103204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2021.103204

- Bui, T., Raymond, F., & Van den Veyver, I. (2013). Current controversies in prenatal diagnosis: Should incidental findings arising from prenatal testing always be reported to patients? Prenatal Diagnosis, 34(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4275

- Carlsson, T., Bergman, G., Karlsson, A. M., Wadensten, B., & Mattsson, E. (2016). Experiences of termination of pregnancy for a fetal anomaly: A qualitative study of virtual community messages. Midwifery, 41, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.08.001

- Crabtree, B., & Miller, W. (2022). Doing qualitative research. Sage publications. Oxford University Press.

- Creswell, J. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, & mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications.

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Research, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Gordon, L., Thornton, A., Lewis, S., Wake, S., & Sahhar, M. (2007). An evaluation of a shared experience group for women & their support persons following prenatal diagnosis & termination for a fetal abnormality. Prenatal Diagnosis, 27(9), 835–839. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.1786

- Graham, I., Logan, J., Harrison, M., Straus, S., & Tetroe, J. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.47

- Hardisty, E., & Vora, N. (2014). Advances in genetic prenatal diagnosis & screening. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 26(6), 634–638. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000145

- Harvey, G., & Kitson, A. (2016). PARIHS revisited: From heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation Science, 11(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2

- Hawthorne, F., & Ahern, K. (2009). Holding our breath: The experiences of women contemplating nuchal translucency screening. Applied Nursing Research, 22(4), 236–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2008.02.007

- Hernández-Martínez, A., Rodríguez-Almagro, J., Molina-Alarcón, M., Infante-Torres, N., Rubio-Álvarez, A., & Martínez-Galiano, J. M. (2020). Perinatal factors related to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms 1-5 years following birth. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 33(2), e129–e135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2019.03.008

- Hogan, A. (2016). Making the most of uncertainty: Treasuring exceptions in prenatal diagnosis. Studies in History & Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History & Philosophy of Biological & Biomedical Sciences, 57, 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2016.02.020

- Hutti, M. (2005). Social & professional support needs of families after perinatal loss. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 34(5), 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884217505279998

- Irani, M., Khadivzadeh, T., Asghari Nekah, S. M., Ebrahimipour, H., & Tara, F. (2019). Emotional and cognitive experiences of pregnant women following prenatal diagnosis of fetal anomalies: A qualitative study in Iran. International Journal of Community-Based Nursing and Midwifery, 7(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.30476/IJCBNM.2019.40843

- Kang, C. (2020). Effects of psychological intervention and relevant influence factors on pregnant women undergoing interventional prenatal diagnosis. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association, 83(2), 202–205. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000220

- Kersting, A., Kroker, K., Steinhard, J., Hoernig-Franz, I., Wesselmann, U., & Luedorff, K. (2009). Psychological impact on women after second & third trimester termination of pregnancy due to fetal anomalies versus women after preterm birth—a 14-month follow up study. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 12(4), 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0063-8

- Korenromp, M., Page-Christiaens, G., Bout, J., Mulder, E., Hunfeld, J., & Potters, C. (2007). A prospective study on parental coping 4 months after termination of pregnancy for fetal anomalies. Prenatal Diagnosis, 27(8), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.1763

- Lafarge, C., Mitchell, K., & Fox, P. (2013). Women's experiences of coping with pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality. Qualitative Health Research, 23(7), 924–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732313484198

- Lathrop, A., & Van De Vusse, L. (2011). Continuity & change in mothers’ narratives of perinatal hospice. Journal of Perinatal Neonatal Nursing, 25(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0b013e3181fa9c60

- Leithner, K., Maar, A., & Maritsch, F. (2002). Experiences with a psychological help service for women following a prenatal diagnosis: Results of a follow-up study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 23(3), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674820209074671

- McKechnie, A., & Pridham, K. (2012). Preparing heart & mind following prenatal diagnosis of complex congenital heart defect. Qualitative Health Research, 22(12), 1694–1706. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312458371

- Nowell, W., & Moules, N. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative, 16(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691773384

- Pisnoli, L., O’Connor, A., Goldsmith, L., Jackson, L., & Skirton, H. (2016). Impact of fetal or child loss on parents’ perceptions of non-invasive prenatal diagnosis for autosomal recessive conditions. Midwifery, 32(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.12.009

- Pitt, P., McClaren, B., & Hodgson, J. (2016). Embodied experiences of prenatal diagnosis of fetal abnormality & pregnancy termination. Reproductive Health Matters, 24(47), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhm.2016.04.003

- Thomson, G., & Downe, S. (2016). Emotions and support needs following a distressing birth: Scoping study with pregnant multigravida women in north-west England. Midwifery, 40, 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2016.06.010

- Watson, K., White, C., Hall, H., & Hewitt, A. (2021). Women’s experiences of birth trauma: A scoping review. Women and Birth, 34(5), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.016