Abstract

This paper examines the successes and challenges of a Supplemental Instruction/Peer Assisted Learning (SI/PAL) scheme at an Irish Higher Education Institute that was the outcome of a co-working approach between academic staff and the Students’ Union. It considers how novel approaches can enhance student experience, support student learning and develop inter-disciplinary skills. The paper reviews three years of data, including student surveys, result outcomes, attendance data and input from representatives of the programme to evaluate the success of this SI initiative. The paper also provides recommendations for other Higher Education institutions seeking to provide, and sustain, Supplemental Instruction within a resource-limited environment through collaborative approaches.

1. Introduction

This paper represents an important contribution to knowledge in relation to collaborative working and Supplemental Instruction (SI) programmes in challenging third level contexts. Based on the authors’ ‘insider’ perspectives and three years of research involving over 700 students in a higher education institute in Ireland, the paper provides insights and recommendations for using collaborative approaches to supplement lecture and/or lab-based education in order to support academic requirements and student needs. The paper presents new evidence relating to the impact of a Supplemental Instruction programme on student satisfaction, session attendance and result outcomes. It analyses how collaboration between an academic discipline and a students’ union can facilitate the success of programmes, empower students and enhance the provision of small-group learning environments while optimising academic staff time. In the final section, recommendations are provided to assist other third level institutes in setting up peer learning programmes using collaborative approaches.

1.1. Higher education context in Ireland

Ireland has a robust Higher Education (HE) system with more than 40 HE institutes, seven of which are publicly funded Universities. All seven of the universities are ranked within the top 750 in the QS World University Rankings for 2021 with three institutes within the top 250 (QS Citation2021). Participation in HE in Ireland is high by international standards (OECD Citation2015) and continues to grow; between 2004 and 2014, full-time third level enrolments increased by over 25% with expectations of continued growth (DES Citation2015, 4). However, the Irish economic recession, beginning in 2008, had a significant impact: core staffing levels contracted by 12% and funding per student reduced by 20% between 2008 and 2016 (HEA Citation2017a, 4). At the same time, student numbers increased as staff numbers stagnated or decreased, increasing the students to staff in Irish Universities from 15.6/1 to 19.8/1 between 2008 and 2014 (HEA Citation2017b, 17). Estimates suggest a student-staff ratio of 23.1/1 in Ireland, compared to an EU average of 15.6/1 (HEA Citation2018, 88).

Within this changing context, staff face increasing pressure to provide quality teaching programmes (Mulryan-Kyne Citation2010, 176), given fewer lecturers, often with less time to commit to student engagement. Furthermore, more students have resulted in larger class sizes. As a result, concerns have been raised about the staff-student ratio within Irish Universities (Hazelkorn Citation2014), with the Higher Education Authority’s Expert Panel noting,

While it is difficult to pinpoint declines in quality, there is anecdotal evidence from institutions of reduced laboratory exposure or levels of practice-based teaching due to staffing pressures which clearly impact upon the student experience. (HEA Citation2017b, 17).

Approximately 10% of students in Irish higher education institutions are considered to be from disadvantaged areas (HEA Citation2019, 10). As the student body has expanded, so has its diversity. For example, between 2015 and 2018, participation in Irish higher education increased from 51% to 55.3%, with particularly evident increases among students with disabilities and students from socio-economically disadvantaged groups (HEA Citation2018b, 21). University students now come from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds with many having had little exposure, through family or friends, to academic processes and language (Haggis Citation2006). For these students in particular, the university experience may present a considerable challenge and larger classes often intensify these challenges (Maringe and Sing Citation2014), with students experiencing less direct contact and feedback from lecturers and fewer opportunities to engage with other students. In recognition of these challenges, research and guidance on pedagogical approaches to teaching in large classes has increased (for example, see: Woollacoot, Booth, and Cameron Citation2014; Arvanitakis Citation2014) and the use of Supplemental Instruction (SI), has been identified as a successful means of addressing some of these issues (Boud, Cohen, and Sampson Citation2001; Daud, Chaudhry, and Ali Citation2016).

1.2. Supplemental instruction

Supplemental Instruction was initially developed in 1973 and targeted at modules identified as ‘high risk’ – i.e. those with poorer results and higher rates of attrition. SI is a cooperative model that typically relies on other students who have completed the targeted module to act as leaders for small groups of students who meet outside of normal instruction spaces (e.g. lecture theatres) (Etter, Burmeister, and Elder Citation2000). Students work within their groups to support each other’s learning rather than rely on an instructor or other figure of authority to ‘teach’ them. For this reason, the terms Peer Assisted Learning (PAL) or Peer Assisted Study Sessions (PASS) are commonly used to describe SI initiatives.

Modules taught through large-class methods are commonly identified as appropriate modules for SI (Etter, Burmeister, and Elder Citation2000). A systematic review of SI studies assessing the effectiveness of the approach in universities and colleges noted its potential to improve academic results and retention of students and reduce failure rates (Dawson et al. Citation2014). Further, evidence suggests that SI/PAL initiatives can be an effective approach as students themselves are an under-appreciated educational resource (Gibbs Citation2015, 206).

While SI schemes have demonstrated success, their implementation is not without challenges for lecturers and other third level staff. Kodabux and Hoolash (Citation2015), for instance, found that lecturers’ attitudes towards such schemes were often ambivalent. A particular fear noted by some lecturers, prior to programme implementation, was the concern that introducing an SI scheme would ‘consume the teaching staff’s time and add supplementary responsibilities to their workload’ (Kodabux and Hoolash Citation2015, 69). Given the increased pressures experienced by academic staff in HE institutes, this concern is not insignificant. Processes that establish and maintain SI schemes, while ensuring the buy-in of lecturers and other professional stakeholders (e.g. by minimising the time commitments of these groups), are thus critical for the long-term success of SI. Innovative collaborative partnerships between stakeholding groups such as administrative support services, academic staff and students’ unions can present as a possible means of achieving this. However, students’ union-academic staff collaborations for implementing SI are relatively uncommon, though not unheard of (see, for instance, Kennan Citation2014). The students’ union-academic staff collaboration at an Irish university, upon which the present study is based, is the only example of such a collaboration in Ireland, and provides an important case study to assess the value of co-working arrangements for SI initiatives. In the remainder of the paper, we examine the university-based SI initiative that was delivered between the SU and the University’s discipline of engineering and consider the effectiveness, benefits and challenges of this students’ union-academic staff collaboration.

1.3. Students’ unions in Ireland

The Universities Act, 1997 defines a student union as a body established to promote the general interests of students of a University and which represents students, both individually and collectively, in respect of academic, disciplinary and other matters arising within the University (Irish Statute Book, Citation1997). Irish students’ unions act as an advocacy group for students on both equality/welfare and educational issues, and they represent students on institutional committees, act as a sign-posting service, and organise social events and charity fundraisers. University Students’ Unions are affiliated with the Union of Students in Ireland which is the national organisation representing the interests of associated Students’ Unions on the island of Ireland. The exact remit of a particular students’ union varies according to the institution it is affiliated to. Some unions operate as part of their higher education institution, while others, such as the Students’ Union at the University that features in this study are separate legal entities. Some students’ unions organise sporting activities and volunteering at their institution, while other unions run commercial outlets, such as shops or bars, to generate income to support their activities.

A National Student Engagement Programme has been operating in Ireland since 2016 (HEA, Citation2016) and was revised in late 2020 (NStEP, 2020) and is project managed by a team at the Union of Students in Ireland. This programme outlines four key domains of student engagement in Ireland, namely (1) Governance and management, (2) Teaching and learning, (3) Quality assurance and enhancement and (4) Student representation and organisation, and one of the five key principles of student engagement is ‘students as co-creators’.

1.4. Background to a SI-Type scheme at qn Irish university

As the representative body for students at the University, the Students’ Union (SU) is a key academic stakeholder. In the 2012–2013 period, the SU identified a set of common challenges facing first year undergraduate students through student, lecturer and University senior management feedback and assessment results. These challenges primarily related to adapting to university life, managing workloads, familiarisation with academic practices and becoming independent learners (Scriver, Walsh Olesen, and Clifford Citation2015).

In order to address these concerns the SU undertook a review of literature to identify means of reducing the aforementioned challenges. Influenced in particular by the work of Thomas (Citation2012) and Malm, Bryngfors, and Mörner (Citation2010), the SU decided to develop a SI/PAL scheme with the specific aims of developing students’ sense of belonging and supporting a successful transition to HE, academic success, skills development and progression.

The SU approached the discipline of engineering at the University (DOE) regarding piloting the proposed SI scheme. This began the partnership between the SU and the DOE, which also required buy-in from management of the discipline, as well as considerable time investment by the academic Director of First Year Engineering, who took on the role of the SI Engineering academic coordinator within the DOE.

In advance of setting up the scheme, first year Engineering students were asked to complete an online survey regarding their experience to date of their first year in January – February, 2013. Two focus groups with about 20 students in total (facilitated by the Students’ Union) explored the responses to the survey in greater depth. Students were involved from this early stage, including in choosing the name for the SI programme. This programme utilised a typical SI/PAL approach in which second year volunteer student leaders were trained to facilitate groups of first year students to engage in shared learning.

Initially, all leaders who applied to the programme were accepted. By year two, the number interested in becoming leaders had increased by approximately 80% and a comprehensive shortlisting and interview process were introduced. By year 3, 23–25% of eligible students were applying to be leaders. Group interviews were introduced subsequently and have proven to be highly effective.

Ten peer learning groups were initially created with about 26 students and 2–3 leaders per group. Groups met weekly for the entire academic year. Skills development was seen as a major benefit of being a leader. Leaders were given vouchers for a free lunch once a week, a hoodie, stationery, telephone credit, a free locker and two social events were organised per year for the leaders. As the programme grew it was decided to phase out the free lunches as it was financially unsustainable and the telephone credit was also phased out due to data protection concerns. Leaders received a certificate at the end of the year presented by the Dean at a celebration event.

Student leaders underwent two days of intensive peer learning facilitation training prior to the start of each academic year. This training covered topics such as reflecting on the first year experience, listening, facilitation, questioning, boundaries, group work techniques and group dynamics, and featured a lot of small group work and role playing. Weekly debrief meetings were attended by all leaders, the SI academic coordinator and the Students’ Union Coordinator.

The SI academic coordinator acted as the main DOE contact for the programme, set the academic direction, liaised with other staff members and management of the discipline as necessary, and managed timetabling. The Students’ Union managed leader recruitment, leader relations, training, promotion, attendance monitoring, organisation of debrief meetings, and measuring impact.

Most SI sessions started with general chat or a quick icebreaker and after discussing the agenda moved on to a comprehensive discussion of coursework and finished with a recap of what was covered in the session. First year students suggested topics to be covered in sessions via online polls before the session or at the start of the session using sticky notes or other agenda setting activities. Common subjects that were covered included Chemistry, Calculus, Computing and Engineering Design, with the first year students often working on problems and teaching each other in small groups of about 3–6 and then discussing their learning afterwards as a larger group.

To further support the long-term viability of the SI programme an independent researcher tasked with analysing data joined the project team. The programme was rolled out in 2013 in the DOE with the research programme running concomitantly.

2. Methodology

This article uses qualitative and quantitative data drawn from student surveys, SI attendance and exam result data. The study also integrates the perspective of two key members of the SI programme and co-authors of this paper. The approach used in this article allows for an ‘insider’s view’ (Asselin Citation2003) that is supported by, but also reflects, the empirical evidence. This approach provides recognition for the often complex processes of programme development, evaluation and adjustment by drawing from the insights of those who have been involved with the programme from the outset.

Data was collected in the form of online surveys undertaken by students at the end of semester 2, first year academic results, SI attendance data provided by the SU, and Central Applications Office (CAO) points data. CAO points are the method of calculating results from the second level Leaving Certificate Exam which is used by the Central Applications Office for the purpose of attaining entry into third level education. The surveys, based on adaptations of Malm, Bryngfors and Morner’s survey (Citation2010), included both closed and open-ended questions designed to ascertain first year students’ and second year leaders’ perceptions of their experience of the SI programme. The surveys analysed in this article were collected over the course of the first three years of the programme – the 2013/14, 2014/15, and 2015/16 academic years. (See for response rates and numbers).

Table 1. Data sources.

Quantitative data was examined using a range of statistical tests including Pearson’s Correlation for linear relationships, ANOVA tests for variance of means, and Chi Square and Cramer’s V for determining significance and strength of relationships between categorical variables. Significance was set at 0.05 (p = ≤0.05) or a confidence level of 95%. A total of 723 first year students are included in the results analysis.

The study was supported by the University’s innovation and performance office and was attendant to ethical considerations including anonymity, confidentiality and consent. All aspects of the study were reviewed by a team comprising representatives from the SU and relevant academic staff to ensure the research was compliant with ethical standards. All students who completed the online survey were made aware of the purpose of data collection along with their rights, i.e. to decide whether or not to participate, to skip or not respond to any question, and to stop the survey at any time. Students who took part in the survey consented for their data to be used for the purpose of generating reports and academic articles. Surveys were completed anonymously. Academic results and SI attendance data were provided by the DOE and/or Students’ Union and anonymised. No identifying details were kept. All anonymous data was held on a password protected computer. While research of this type is not considered to be of a sensitive nature, questions on the survey were reviewed for sensitivity and students were provided details about where they could seek additional supports should they be required.

As with any study, there are some limitations. Data collected during this period does not allow for the analysis of lecture attendance or the impact of teaching innovations that may have occurred. Thus, it is not possible to state that the effects of SI session attendance are independent of lecture attendance or educational approaches used in lectures. Further, not all students completed surveys, with a notable decline in the response rate in the 2014/15 year. Potentially, the students who did not participate in the surveys may be those who are least engaged and the findings may thus underestimate or overestimate some results. Nevertheless, the programme and the processes through which it has been implemented offer important lessons for educators and educational administrators.

3. Findings and discussion: successes and challenges of the SI programme

Success for the SI programme was measured through several indicators, including satisfaction with the initiative among participating first year students, the level of student engagement, impact on result outcomes of first year students, and perceptions of the value of participating among student leaders. In the following sections we review the extent to which the programme achieved success, as defined above, and consider the impact of collaborative working between academic and SU partners.

3.1. Satisfaction among first year students

Satisfaction was measured over the first three years of the programme through an online survey based on Malm, Bryngfors, and Mörner (Citation2010) with some modifications to suit the specific context (see Scriver, Walsh Olesen, and Clifford Citation2015, for more details). While the majority of those who responded to the survey indicated that they were satisfied overall with the programme, there was a notable jump in satisfaction between the pilot year and subsequent years from 56% stating that ‘overall I am satisfied with [the SI programme]’ in the 2013–14 academic year, to 83% in 2014–15, and 85% in 2015–16.

Students had the opportunity to provide further feedback about the programme in response to the survey questions, ‘What is the best thing about [the programme]?’ and ‘How could [the programme] be improved?’. In Year 1, comments primarily focused on the timing of the sessions as problematic, with some respondents also raising concerns about the abilities of the student leaders. However, by Year 2 of the programme, these concerns appeared to be largely addressed with few comments reflecting such concerns. The following quotes demonstrate the shift in perceptions of the SI programme that occurred over the period:

The structure of the sessions needs to be improved. We often didn't know where to start when we came into our session. The leaders needed to be more active and helpful. (First Year Participant, 2013-14)

It was overall very good. I've never regretted going to a … session. You would always get something at the end of it, whether it's learning something or having a bit of craic [fun]. I would definitely recommend everyone to go. (First Year Participant, 2015-16)

In open-ended questions students commonly stated that SI sessions helped them prepare for exams, noting that having leaders who had been through the experience and could share their own learning was helpful in calming nerves and understanding what to expect. Students were also highly appreciative of the social benefits of SI, including helping them to meet others and to ‘settle in’ to first year, as demonstrated in the statement below in response to the question ‘what is the best thing about [the SI programme]?’:

Getting to know people and the ability to interact with students who have gone through the same things as I do. (First Year Participant, 2013-14)

Over the three years of research, the vast majority of students found SI to be a rewarding experience, with satisfaction improving as the programme developed. Difficulties with session timing that emerged in the pilot year of the programme were successfully resolved within subsequent years through communications between the SU and the DOE. Concerns about the quality of student leaders also largely disappeared after the pilot year – increased training and support by the SU for leaders, as well as the leaders themselves having more experience with a SI programme (due to them having participated the year previously as first year students), are likely to have addressed this concern. Satisfaction ratings and comments suggest that SI sessions were successful in helping students to integrate into first year University life – a key motivation of the programme.

3.2. Attendance at SI sessions

Ensuring sufficient attendance in voluntary initiatives can be challenging. However, for the benefits of SI programmes to be experienced more widely, attendance is critical. In this SI programme, attendance presented some challenges, particularly in the pilot year. First year students noted poor attendance was associated with insufficient numbers for adequate discussion around problems and poor bonding in the group. Student leaders also noted challenges relating to poor attendance:

Lack of students attending sessions can be demoralising and difficult to work with smaller numbers. (Leader, 2014-15)

Collaborative engagement was also required to resolve issues in timetabling, noted above and reported by 11% of students as a reason for not attending. Working together to identify opportunities for change within the teaching and laboratory schedule, the SU and the DOE were able to schedule SI sessions at times that suited students – neither too early nor too late in the day and which did not clash with any lectures or laboratories. By the second year of the programme, the percentage of students indicating they did not attend the SI sessions because lectures or labs were ‘in the way’ dropped from 11% in the 2013–2014 academic year to just one student in the 2014–2015 year.

These efforts appear to have been successful with a notable increase in self-reported attendance between the pilot year and subsequent years, from 48% of students indicating they had attended an SI session at least once in the 2013–14 academic year, to 75% in 2014–15 and 69% in 2015–16. This improvement was likely also impacted by interactions between incoming first year students and leaders and lecturers, as both leaders and lecturers had an improved understanding of the initiative after the pilot year. As the programme progressed, understanding of the purpose and value of the SI programme, and the respective roles of first year student participants and student leaders, was clarified. This appeared to lead to realistic expectations and greater appreciation of its benefits from all stakeholders.

While addressing lower-than desired attendance through amending timetables was a challenge it was one that could be accommodated. However, the most common reason students gave for not attending the SI programme in the pilot year was that they were ‘too busy with assignments and study to attend’ with 40% in the pilot year indicating this answer. In the second year, 69% cited this as a reason not to attend sessions. This barrier is not one that is easily removed – attendance at the SI sessions does not reduce the overall number of hours students must attend and some students perceived the SI sessions as increasing this burden. Nevertheless, the SU and the DOE took efforts to disseminate the findings of the research component in relation to improved results through posters and a redeveloped website. While a direct link between these efforts and attendance in the third year cannot be certain, only 26% of respondents in the third year stated that they were too busy with assignments and study to attend despite no easing in academic contact hours occurring.

Besides these successes, there were also efforts that were shown to be less effective. In order to respond to concerns about attendance dropping over the course of the year, in second semester of the 2015–2016 academic year, sessions were reduced from weekly to twice monthly. This was found to have a negative impact, resulting in further reductions in attendance. Some students complained that it was more difficult to remember to attend when the weekly schedule changed, and students with better attendance felt they were missing out. The following year sessions returned to a weekly schedule.

The pilot year and subsequent changes to the programme relied heavily on interactions between the SU and the DOE and also the targeted use of research findings. Students appeared to recognise the benefits of the collaboration, as described by one student leader,

I think [engineering] is doing an excellent job of promoting the service internally targeting the students who will use it and the Students’ Union is promoting the service as a benefit to the whole University. (Leader, 2014-2015)

Encouragement from lecturers was identified as important for students to increase their perception of the value of attendance at the SI sessions. Resolving practical issues such as the timing of the sessions also required collaborative efforts with the SU liaising with lecturers in the DOE to identify appropriate time-slots for the sessions. Importantly, the SU managed the changes and the re-organisation of sessions in consultation with the DOE academic staff and student representatives, meaning that lecturers did not experience an undue time burden.

3.3. Impact on academic results

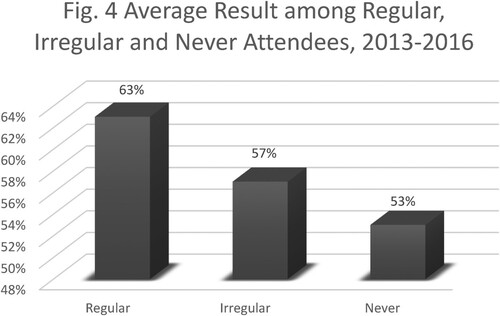

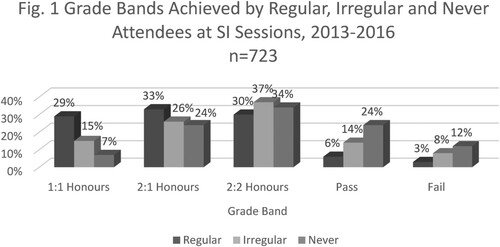

One of the desired outcomes for the SI programme was to assist students in their studies, with an expected outcome of better academic results. Consistently across the three years of the SI programme, students who attended SI sessions more frequently achieved higher results (R = 0.286, p < 0.001, n = 723), ().

Figure 1. Grade bands achieved by regular, irregular and never attendees at SI Sessions, 2013–2016 (n = 723).

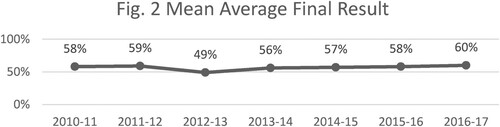

Additionally, there was a slight, but steady increase in the average result of students overall since the introduction of the SI programme (see ). In 2012–2013 the average results dropped considerably, a likely outcome of substantial changes in the engineering course structure and the introduction of the first cohort of students to have completed a new second level maths curriculum, known as Project Maths.

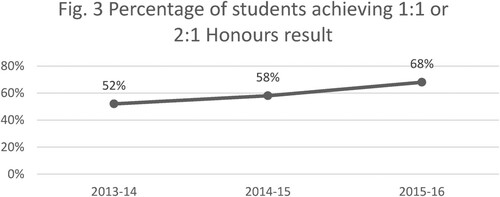

Furthermore, there has been a notable increase in students achieving 1:1 honours (‘A’ result) or 2:1 honours (‘B’ result) results over the three years since the introduction of the SI programme (see ).

In fact, across the three years of the programme, 49% of students that attended SI sessions achieved a 2:1 or a 1:1 Honours, compared to 30% of students who never attended SI sessions (p < 0.001).

The value of regular SI attendance was also evident regardless of whether students entered into their programme on higher (more than 490Footnote1 CAO points) or lower (490 or fewer CAO points) secondary education results. Among students who entered on lower CAO points and who attended SI sessions regularly, 99% received an overall passing grade and 89% received an Honours results. Conversely, approximately 12% of students who entered on lower CAO points and never attended SI sessions did not achieve a passing result and 58% received an Honours result. As shown in , while students who entered their University programme with higher CAO results typically achieved higher grades, attendance at SI sessions was a benefit to students regardless of their CAO points on entry. These results were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 2. Comparison of SI attendance and grade band result by CAO points on entry to university.

Overall, evidence indicates that participation in the SI programme has beneficial impacts on students’ academic results. Across the three years of the study it was found that students who attended SI sessions achieved a mean result of 59% compared to those who did not attend, who achieved a mean outcome of 53%. This difference becomes even more notable when comparing ‘regular’ (n = 178) and ‘never’ attendees (n = 222) – regular attendees (attending 3 or more sessions in a semester) achieved a mean average of 63%, 10% higher than those who never attended, as shown in .

Given the challenges within Irish higher education during this time period, as discussed in section 1.1, the analysis suggests that the SI programme has potentially reduced the negative impacts of such contextual changes. The relatively low time-input required of lecturers to run the programme has allowed students to take a more active role in their own education.

3.4. Learning beyond the classroom: the impact of the SI programme on student leaders

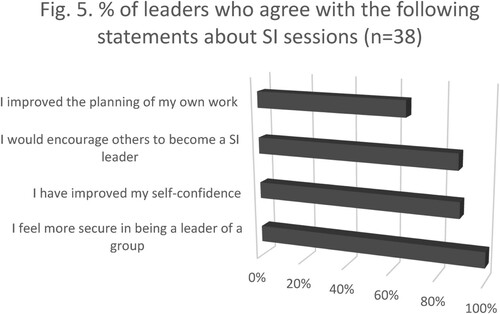

One of the identified benefits of SI/PAL schemes is the fostering of social and personal skills that are less likely to be developed within traditional lecture environments (Arendale and Hane Citation2014). Thus, an indicator of success for the programme is the development of skills among second year students who act as leaders for the University-based SI programme. Leaders rated the development of leadership skills very highly, with 100% of leaders stating that their experience with SI had made them feel more secure in being a leader of a group. The development of personal qualities, such as self-confidence, was also highly rated across the three years (see ). While the development of leaders’ own study skills was consistently rated less highly than other skills, the majority of participants agreed that being a SI programme leader improved their study skills, such as the planning of their own work.

Leaders were also able to identify specific skills they developed during their time as a leader. The three most commonly cited skills accredited to the SI programme for the leader cohort are summarised in .

Table 3. Top three skills leaders believe they build via the SI programme.

An important aspect of fostering skills among leaders, was the provision and/or organisation of training by the SU in collaboration with the DOE and other University services. Over the period of the three years of the research, training was increased from basic facilitator training to include training on careers, delivering presentations, health and wellbeing, and discipline related topics. These trainings were well received, with 100% of engineering leaders (n = 38) across three years of the programme agreeing that they were ‘more secure being a leader of a group’ and 88% had improved their self-confidence Several second year leaders also drew attention to the value of the additional initiatives as unprompted comments in the survey, as one explains,

The benefits to the leaders are also fantastic especially with the introduction of professional improvement e.g. Presentation skills, mock interviews. (Leader, 2015-16)

[the SI programme] is also great for the leaders as we have been given many fantastic information talks and training that will definite benefit me through my working life. (Leader, 2016-17)

Building on these skills, in 2015–2016 a new leadership initiative was introduced: Student Coaches. These coaches are third year former leaders who provide guidance and mentorship to second year leaders.

The SI programme was thus successful in developing recognised skills among student leaders and supporting the University’s goal of developing graduate attributes. It is notable that across the three years of the programme review only one leader out of a total of 71 dropped out of the programme and this was due to personal time-commitment issues.

4. Challenges and benefits of collaborative working

One of the benefits of the SI programme noted by student participants has been the opening of new channels of communication between students, and between students and lecturers that has been facilitated by the collaborative nature of the programme. First year students described how the SI sessions being facilitated by other students increased their comfort in being able to ask questions or raise concerns about lectures. Students who may have felt uncomfortable speaking directly to academic staff appeared to be less intimidated to speak with leaders or with the SI group as a whole. Leaders then had the unique opportunity to bring these concerns to weekly SI programme debriefing meetings attended by SU and academic staff representatives. As the programme progressed it was evident to authors of this paper who attended the meetings that leaders developed strong skills in advocating for the first year students as their confidence and leadership skills grew. Academic staff and the SU were able to then take timely action in response to issues raised. Thus, the division of responsibility, coupled with the collaborative approach, had multiple benefits, with first year students expressing their concerns more comfortably, leaders developing skills in advocacy, and the SU and academic staff working together to resolve issues that emerged.

Despite these successes, collaborative working also created some specific challenges. Some students and leaders raised concerns that some lecturers were not overly familiar with the SI programme and several leaders specifically recommended that lecturers liaise with leaders in relation to course content or other issues, as one leader explains,

[The programme could be improved by …] Encourag[ing] communication between leaders and first year lecturers, especially towards the start of the year. The first years tended to be unwilling to tell us what they wanted to cover in sessions. Lecturers could pass on difficult topics they had covered, so leaders would have something to work off. (Leader, 2014-15)

However, staff not involved in the running of the SI programme initially expressed concerns about sharing of information with leaders, in case leaders might ‘teach’ students course content or inadvertently facilitate plagiarism through sharing of project or assignment work. Efforts were made to alleviate such concerns by providing further information on the peer learning model to first year teaching staff and by facilitating sharing of course content between lecturers and leaders on a phased basis to avoid pre-engagement with upcoming content, as well as continually supporting leaders to facilitate rather than teach. Ensuring on-going communications between partners in the scheme are visible to students was identified as important to avoid any perception of disconnection between various stakeholders.

Timing and time-commitment were not only issues for students. While the SU shouldered the greatest time-commitment to the development and roll-out of the programme, including central coordination and undertaking the majority of communication with leaders, an academic from the DOE acted as the academic lead and oversaw the programme within the DOE. Once the SI programme was operational for a number of years, this role took up approximately 5% of the academic’s time – a significant commitment. Ensuring that this work is recognised, rewarded and that time is adequately allocated is essential to avoid over-burdening those who participate.

Through the collaboration on the SI programme, SU and academic staff worked together intensively over a multi-year period of time on a common goal. The partnership held despite annual changes in SU elected representatives. Indeed, the collaboration has developed further since the introduction of SI, with the SU now coordinating the delivery of a student-led session during first year orientation for engineering students in partnership with academic staff.

5. Key lessons and recommendations

Evidence suggests that the collaboration between the University’s Students’ Union and the DOE has helped to deliver a successful and sustainable SI/PAL programme. The empirical data has shown improved results for those who participate in the SI programme, increased confidence in asking questions, facilitated integration into University life for first year students, and development of leadership skills among second year leaders. This has been recognised through the expansion of the programme with financial support from central funding at the University, the University’s 2019 external institutional quality review team commending the programme and recommending it be mainstreamed, and national recognition through the Student Engagement Activity of the Year award. Now in its eighth year of operation, the model of collaborative working between the SU and the DOE is being reproduced within other disciplines at the University. Importantly, the approach offers a model for the provision of Supplemental Instruction that provides opportunities for small-group learning and the development of inter-disciplinary skills that students expect from their University experience. It is a model which can be replicated in other HE institutes internationally. With changes to University funding and workloads for academic staff, the adoption of this collaborative model supports independent learning and knowledge acquisition. While student leaders and student coaches do not receive financial remuneration for their contributions, they can access a range of free trainings to further support their personal development – a ‘perk’ that was appreciated by the students involved. Below we provide some of the key lessons and recommendations from the three years of the SI programme to assist other HE institutes in implementing similar initiatives:

Hold information sessions and develop stakeholder groups in order to build support from academic staff. Adequate information should be provided to all relevant academic staff ahead of the programme’s initiation to ensure that concerns regarding time commitments and the function of the programme are allayed. On-going communication between academic staff, coordinators and student leaders should be facilitated, for instance through stakeholder groups with adequate academic staff representation.

Nominate an academic coordinator, with adequate recognition of their time-contribution within the academic institution’s workload reviews. Nominating an academic coordinator, along with the SU coordinator, ensures better communication between partners and reduces a sense of burden on other academic staff.

Involve all stakeholders in decision-making regarding the programme. Weekly debrief meetings with second year leaders, representatives of first year student participants, academic staff and coordinators facilitated the sharing of information, communication and joint decision-making. This provided all involved with a greater sense of ownership in the programme and the ability to make timely adjustments. Empowering first year student class representatives and taking their views seriously is an important element of programme management.

Facilitate the easy sharing of 1st year course information with leaders. With 1st year courses often comprising quite a number of modules, it can be difficult for multiple academic staff to provide updates to leaders on a weekly basis. Adding student leaders as Guests to relevant 1st year modules in the Virtual Learning Environment can provide a quick and easy way to overcome this.

Experiment with student leader ratios to strike the right balance. Initially, student to leader ratios in the SI programme were around 26:2-3. When attendance was low, especially in the first year, the rooms often looked quite empty and it was sometimes hard to run certain activities that required more students. In subsequent years, increasing the ratio to approximately 33–40 students to 2–4 leaders worked better and anecdotal evidence suggests that students began to feel they were missing out if they did not attend. Also, reducing the number of peer learning groups is more efficient from a coordination perspective and fewer rooms are required, which makes timetabling easier.

Don’t underestimate the importance of timing peer learning sessions correctly. In the SI programme, it quickly became clear that peer learning sessions should ideally be sandwiched between mandatory classes and not take place too early or too late in the day. Peer learning sessions initially took place on Wednesdays at 3pm and 5pm. After receiving feedback from students, the decision was made to just run sessions at 3pm and this had a positive impact on attendance. Sometimes it can take experimentation to identify the best times slots.

Build on leadership skills through additional supports and training opportunities. After the initial pilot phase of the SI programme, additional leader training was developed and included comprehensive sessions on student supports and signposting to services. Offering opportunities for further development of leadership skills offers positive reinforcement and is an added incentive for students to participate. Examples of this include training leaders to chair and take minutes at debrief meetings, running information sessions with former leaders about work placement, providing training on interview skills and CVs, and assisting students to apply for relevant University awards for volunteering and employability. Police vetting for leaders (as was required for working with students under the age of 18) and short briefings on data protection legislatio were also introduced.

Develop clear processes and reliable IT systems. As the SI programme became more established, the programme team became better at creating clear processes, communicating expectations to leaders and developing IT systems to facilitate attendance taking, communication with leaders and recording impact. These streamlined operations and facilitated expansion to other disciplines. Recording attendance efficiently and accurately is vital for measuring peer learning impact. Initially this posed quite a challenge for the programme, later, a specialised system for taking attendance was developed on the University’s student portal. This allows first year students to see their attendance and it is linked to the attainment of a Collaborative Learner digital badge, which appears to have supported an increase in attendance.

Maintain consistency. Maintaining peer learning groups comprised of the same leaders and first year students and meeting at the same times on a regular schedule across the year benefits students by creating a greater sense of belonging and routine. For the first two years of the SI programme, groups were changed in Semester 2 and students responded negatively to this. Subsequently, groups were maintained for the entire year and project teams were allocated within SI groups, which enhanced participation.

Celebrate partnership and don’t take it for granted. The success of the partnership in the SI programme was based on a shared commitment to collaborate (and acknowledging that no one partner could achieve this on their own), maintaining open and honest communication at all times, and passionately sharing the goal of supporting students to help each other and excel.

Mind the leaders and they’ll mind the peer learning programme. Without student leaders there is no peer learning programme. Building community amongst leaders, being highly responsive to leaders and supporting them to develop their skills has contributed to high engagement levels amongst leaders in the SI programme and a very low attrition rate.

Include a robust research programme to accompany the initiative. The evidence generated through the research programme contributed towards achieving continued funding, incentivising students to attend sessions, encouraging other disciplines to pilot the SI programme, and providing feedback to the SU and the DOE on student and leader perceptions, allowing for adaptations to occur as necessary. Including a research component to any new programme is highly recommended for at least the first three years of the programme, and ideally longer.

6. Conclusion

The University-based SI programme examined in this paper demonstrates how collaborative relationships between students, student representative bodies, academics and researchers can lead to successful initiatives that support student learning while minimising the time-requirements from academic staff in third level. As the third level sector evolves it can present challenges but also new opportunities to devise new approaches to education. Drawing from students’ feedback, the University’ Students’ Union worked with academic staff to identify and roll out a programme to support student and academic requirements. The programme, perceived as a success by the University, is now being offered to approximately 1610 first year students per year in a wide variety of disciplines and there are plans to further expand the programme in the coming years. The evidence presented in this paper and the recommendations that arose from the study are relevant to higher education institutes managing similar challenging contexts. The success of this programme is testament to the possibility of creative solutions to academic needs through co-productive approaches and offers a replicable model for other HE institutes.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stacey Scriver

Dr. Stacey Scriver is a lecturer in the School of Political Science and Sociology where her research focusses on gender and violence. Scriver has an interest in education and equality and has published research in the field of education in Irish Educational Studies, Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, and Journal of Learning and Development in Higher Education.

Amber Walsh Olesen

Amber Walsh Olesen is director of the CÉIM initiative and is based at NUI Galway Students' Union. She has a background in programme management and marketing, with specific experience in supporting start-ups and process design. Her current key interests include student-centred learning, enabling inclusive learning, studentled innovation, and supporting successful transitions and belonging in higher education.

Eoghan Clifford

Dr. Eoghan Clifford is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Engineering at NUI Galway. He is the academic lead of CÉIM in the School of Engineering and has been since its inception. His research and teaching interests include water and wastewater engineering and transport engineering. He also has an interest in engineering education and improving the experience and outcomes for undergraduate and postgraduate engineering students. He has published in a variety of engineering, science and economic journals and has also published in the Journal of Learning and Development in Higher Education.

Notes

1 490 points was chosen as the cut-off point for lower CAO points as it was the mean CAO points among engineering students in the sample. It is possible to achieve a maximum of 625 CAO points through the Leaving Certificate Examination. 490 points is thus equivalent to a B2 grade. Between 2013 and 2016, students achieving over 490 points would be within the top 20% of students in the given year.

References

- Arendale, D. R., and A. Hane. 2014. “Holistic Growth of College Peer Study Group Participants: Prompting Academic and Personal Growth.” Research and Teaching in Development Education 21 (1): 7–29.

- Arvanitakis, J. 2014. “Massification and the Large Lecture Theatre: From Panic to Excitement.” Higher Education 67: 735–745.

- Asselin, M. E. 2003. “Insider Research: Issues to Consider When Doing Qualitative Research in Your own Setting.” Journal for Nurses in Staff Development 19 (2): 99–103.

- Boud, D., R. Cohen, and J. Sampson. 2001. Peer Learning in Higher Education: Learning from and with Each Other. London: Kogan Page.

- Daud, S., A. M. Chaudhry, and S. K. Ali. 2016. “Lecture Based Versus Peer Assisted Learning: Quasi-Experimental Study to Compare Knowledge Gain of Fourth Year Medical Students in Community Health and Nutrition Course.” Res Dev Med Educ 5 (2): 62–68.

- Dawson, P., J. van der Meer, J. Skalicky, and K. Cowley. 2014. “On the Effectiveness of Supplemental Instruction: A Systematic Review of Supplemental Instruction and Peer-Assisted Study Sessions Literature Between 2001 and 2010.” Review of Educational Research 84 (4): 609–639.

- DES. 2015. Projections of Demand for Full Time Third Level Education, 2015–2029. Dublin: Department for Education and Skills. https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Statistics/Statistical-Reports/Projections-of-demand-for-full-time-Third-Level-Education-2015-2029.pdf.

- Etter, E. R., S. L. Burmeister, and R. J. Elder. 2000. “Improving Student Performance and Retention via Supplemental Instruction.” Journal of Accounting Education 18: 355–368.

- Gibbs, G. 1992. “Control and Independence.” In Teaching Large Classes in Higher Education: How to Maintain Quality with Reduced Resources, edited by G. Gibbs, and A. Jenkins, 37–59. London: Kogan Page.

- Gibbs, G. 2015. “Maximising Student Learning Gain.” In A Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Enhancing Academic Practice, Fourth Edition, edited by H. Frye, S. Ketteridge, and S. Marshall, 193–208. London: Routledge.

- Haggis, T. 2006. “Pedagogies for Diversity: Retaining Critical Challenge Amidst Fears of ‘Dumbing Down’.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (5): 521–535.

- Hazelkorn, E. 2014. “Rebooting Irish Higher Education: Policy Challenges for Challenging Times.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (8): 1343–1354. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.949540.

- HEA. 2017a. Review of the Allocation Model for Funding Higher Education Institutions Working Paper 1: The Higher Education Sector in Ireland. Dublin: Higher Education Authority. http://hea.ie/assets/uploads/2017/06/hea_rfam_working_paper_1_the_higher_education_sector_in_ireland_022017.pdf.

- HEA. 2017b. Review of the Allocation Model For Funding Higher Education Institutions. Interim Report. Dublin: Higher Education Authority. https://hea.ie/assets/uploads/2017/06/HEA-RFAM-Final-Interim-Report-062017.pdf.

- HEA. 2018. Higher Education System Performance. Dublin: Higher Education Authority. https://hea.ie/assets/uploads/2018/01/Higher-Education-System-Performance-2014-17-report.pdf.

- HEA. 2018b. Progress Review of the National Access Plan and Priorities to 2021. Dublin: Higher Education Authority. Available at: Higher Education Authority - Progress Review of the National Access Plan and Priorities to 2021 (hea.ie).

- HEA. 2019. A Spatial & Socio-Economic Profile of Higher Education Institutions in Ireland Using Census Small Area Deprivation Index Scores derived from Student Home Address Data, Academic Year 2017/18. Dublin: Higher Education Authority. Available at: Higher-Education-Spatial-Socio-Economic-Profile-Oct-2019.pdf (hea.ie).

- HEA. 2016. “Enhancing Student Engagement in Decision Making.” Higher Education Authority. http://www.thea.ie/contentfiles/HEA-IRC-Student-Engagement-Report-Apr2016-min.pdf.

- Irish Statute Book. 1997. Act No. 24/1997 - Universities Act, 1997. Government of Ireland.

- Kennan, C. 2014. Mapping Student-Led Peer Learning in the UK. York: The Higher Education Academy. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/resources/peer_led_learning_keenan_nov_14-final.pdf.

- Kodabux, A., and B. K. A. Hoolash. 2015. “Peer Learning Strategies: Acknowledging Lecturers’ Concerns of the Student Learning Assistant Scheme on a new Higher Education Campus.” Journal of Peer Learning 8: 59–84. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ajpl/vol8/iss1/7.

- Kokkelenberg, E., M. Dillon, and S. Christy. 2008. “The Effects of Class Size on Student Grades at a Public University.” Economics of Education Review 27: 221–233.

- Malm, J., L. Bryngfors, and L. Mörner. 2010. “Supplemental Instruction (SI) at the Faculty of Engineering (LTH), Lund University, Sweden: an Evaluation of the SI Program at Five LTH Engineering Programs, Autumn 2008.” Australian Journal of Peer Learning 3 (1): 38–50.

- Maringe, F., and N. Sing. 2014. “Teaching Large Classes in an Increasingly Internationalising Higher Education Environment: Pedagogical, Quality and Equity Issues.” Higher Education 67 (6): 761–782.

- Mulryan-Kyne, C. 2010. “Teaching Large Classes at College and University Level: Challenges and Opportunities.” Teaching in Higher Education 15 (2): 175–185.

- OECD. (2015). “Ireland” in Education at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2015-62-en

- QS. (2021). QS World University Rankings, 2021. https://www.topUniversities.com/University-rankings/world-University-rankings/2021.

- Scriver, S., A. Walsh Olesen, and E. Clifford. 2015. “From Students to Leaders: Evaluating the Impact on Academic Performance, Satisfaction and Student Empowerment of a Pilot SI Programme among First Year Students and Second Year Leaders.” Journal of Learning and Development in Higher Education (November), http://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/359/pdf.

- Thomas, L. 2012. Building Student Engagement and Belonging in Higher Education At A Time Of Change: Final Report from the What Works? Student Retention & Success programme. Accessed November 15, 2015 https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/what_works_final_report.pdf.

- Woollacoot, L., S. Booth, and A. Cameron. 2014. “Knowing Your Students in Large Diverse Classes: A Phenomenographic Case Study.” Higher Education 67 (6): 747–760.