Abstract

Current international policy documents on teacher education are peppered with the word partnership and there seems to be an assumption that there is a common agreement regarding understandings of ‘partnership’. Traditionally the university has been the decisive voice in educational partnerships which has often led to a power differential as well as a failure to fully maximise the potential of the partnership. Based on interviews with school leaders [n = 10], student teachers [n = 10], co-operating teachers [n = 10] and university tutors [n = 10] associated with an initial teacher education (ITE) programme in a university in the Republic of Ireland, this article provides a synthesis of this range of stakeholders’ views on how school-university partnerships can be optimised. The major themes that emerged from the research data included: (1) misconceptions about degrees of partnership in ITE and of roles therein; (2) the key role of the co-operating teacher and ‘close-to-practice’ research in fostering a ‘third-space’ in ITE and (3) a sense of malaise in relation to levels of pressure, change over-load and lack of adequate resources.

KEYWORDS: school-university partnership; school leader; university tutor; co-operating teacher; student teacher

Partnership in Teacher Education: what’s it all about?

Current international policy documents on teacher education are peppered with the word partnership and there seems to be an assumption that there is a common agreement regarding understandings of ‘partnership’. The resulting lexicon may suggest that terms like partnership, collaboration, co-operating teacher, mentor teacher, partner-school and university-school have the same meaning across all jurisdictions. However, heterogeneity rather homogeneity characterises comparisons of teacher education across the world (Beach and Bagley Citation2013; Flores Citation2018; Harford Citation2010). One of the four Common European Principles for Teacher Competences and Qualifications (European Commission Citation2005, 3) is that teaching is a ‘profession based on partnership: institutions providing teacher education should organise their work collaboratively in partnership with schools, local work environments, work-based training providers and other stakeholders.’ In further recognition of the role of partnerships in teacher preparation, the Council of the European Union (Citation2014, 183) observes that:

Teacher education programmes should draw on teachers’ own experience and seek to foster cross disciplinary and collaborative approaches, so that education institutions and teachers regard it as part of their task to work in cooperation with relevant stakeholders such as colleagues, parents and employers.

In support of this, the OECD (Citation2105) advocates that partnerships are central to the fostering of innovative teaching and learning-communities in which there is a bridge between theory and practice and between practitioners and those engaged in academic research. However, while this is accepted in principle, the practice of operationalising school-university partnerships and of optimising learning through such partnerships can be esoteric.

The school-university partnership is the bedrock of ITE across both time and space (Harford and O’Doherty Citation2016). However, despite its centrality to ITE, its ubiquitous use often renders its actual meaning ambiguous and many policy documents contain references to school–university partnerships which lack detail, particularly in relation to roles and responsibilities (Harford and O’Doherty Citation2016). The historical and cultural norms accompanying roles can mean that collaboration can be challenging, resulting in university tutors and co-operating teachers questioning and deconstructing their roles prompting them to engage with one another in more complex and fluid ways (Reynolds, Ferguson-Patrick, and McCormack Citation2013). A key part of the challenge in relation to understanding the nature of school–university partnerships and of roles therein is achieving a clearer understanding of who teacher educators are, how they understand their roles (Czerniawski, Guberman, and MacPhail Citation2017; Flores Citation2016; Izadinia Citation2014) and making explicit the work they do in the professional development of student teachers (Flores Citation2018). Furthermore, partnerships by their very nature often feature numerous levels of micro politics (März and Kelchtermans Citation2013).

Traditionally the university has been the decisive voice in educational partnerships which has often led to a power differential which some scholars argue fails to strategically access the knowledge and expertise of teacher preparation stakeholders (Zeichner, Payne, and Brayko Citation2015). The forms and types of knowledge espoused at the university level and at school level are often in collision, with universities typically promoting theoretical knowledge and school’s practitioner knowledge. This ‘theory/practice’ divide is a perennial challenge in teacher education spaces (Harford and MacRuairc Citation2008) and effective school–university partnerships explicitly question ‘the binary of theory and pratice’ (Flores Citation2016, 218) in order to establish effective ‘learning places’ (Conway, Murphy, and Rutherford Citation2014). la Velle (Citation2019) argues that the theory/practice relationship should be seen not so much as a divide, but as a nexus. Derived from the Latin verb nectere, a nexus is a connection that combines the notions of ‘bringing together’ and ‘forming a focal point’ (la Velle, Citation2019). According to la Velle and Flores (Citation2018), pedagogical practice is underpinned by a combination of theory emerging from empirical evidence and original argument based on research. In addition, ‘close-to-practice’ research (BERA Citation2018) can also engender new theory, centring on issues identified by practitioners as pertinent to their practice through partnership with those whose main expertise is research or practice, or both. Hence, the nexus involves practice informed by theory and theory informed by practice (la Velle Citation2019). Engeström (Citation2008) underlines the need for a framing of the school–university partnership model which fosters collaboration across stakeholders where the different interests, values and practices that exist are negotiated. In such a model, there is no single nexus of control, rather the nexus changes as appropriate to the time and context and the merit of the partnership are evidenced by reconceptualising learning spaces. Max’s (Citation2010) use of ‘boundary zone’ as ‘space where elements from two activity systems enter into contact’ (216) creates the kind of oscillating and malleable space which allows for the creation of a new hybrid or ‘interspace’ (Hartley Citation2007) between schools, universities and communities in ways that foster teacher learning.

Zeichner, Payne, and Brayko (Citation2015) suggest the site for acquiring knowledge of teaching is the practice field, namely schools, whereas knowledge about teaching is mostly acquired at the university. The meeting point where these aspects of teacher knowledge meet and often collide is referred to as the ‘third space’ (Zeichner Citation2010). ‘Blurring the boundaries between researcher and teacher through teacher research’ (Arhar et al. Citation2013, 220; Cochran-Smith and Lytle Citation2009) is central to creating effective third spaces for school–university alliances to flourish. This notion of research engagement becoming an integral part of teacher professionalism is also echoed by BERA-RSA (Citation2014): ‘Research literacy is viewed as a key dimension of teachers’ broader professional identity, one that reinforces other pillars of teacher quality: notably subject knowledge and classroom practice’ (10). In their seminal work on teacher knowledge, Cochran-Smith and Lytle (Citation1999) propose three distinct types of knowledge namely: Knowledge-for-practice; Knowledge-in-practice; and Knowledge-of-practice. Knowledge-for-practice is based on the assumption that the knowledge teachers need to teach well is produced primarily by university-based researchers and scholars in various disciplines. Knowledge-in-practice is ‘acquired through experience and through considered and deliberative reflection about or inquiry into experience’ (Cochran-Smith and Lytle, Citation1999, p. 262). Finally, knowledge-of-practice is generated by the practice field making their classrooms and schools sites for inquiry, and becoming a part of the wider research community.

Berger and Johnston (Citation2015) argue that establishing a third space through a partnership model requires time, deliberate planning, resources and a sense of openness which may result in ‘failing’ but such ‘failing’ is vital to ultimate learning. How the third space is structured and integrated into teacher education programmes, and the power relations between the various actors which occupy these spaces, are important factors that contribute to effective school-university alliances. However, recent research (O’Doherty and Harford Citation2017) suggests that the reform and reconceptualisation of ITE in Ireland have resulted in greater demands being placed on schools in relation to ‘partnership’; that the timing of the reform agenda, as well as the lack of a resource base, is problematic; and that capacity and ‘good will’ within the system are now under threat. Those most affected by the reform of ITE, the schools, and the higher education institutions (HEIs) are being required to initiate resource neutral reform (Sugrue and Solbrekke Citation2017) during a time when HEI funding was cut by 38%, while student numbers increased by 25% (Boland Citation2015). The effectiveness of school-university partnerships and university tutor/co-operating teacher collaborations require more than a willingness to engage in dialogue and collaboration (Ievers et al. Citation2013). Harford and O’Doherty (Citation2016) assert that the ‘absence of investment in enabling processes and essential negotiation prior to the implementation of the reform creates a significant impediment to realising the desired outcomes’ (53). Furthermore, the Irish context reflects the international research in relation to levels of teacher anxiety, stress and burn out (Livingston and Flores Citation2017), all of which have significant implications on the potential for school–university partnerships and collaboration more broadly.

Models of School–University Partnerships

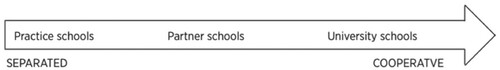

Internationally, a range of models of school–university partnershipis in operation. Summarised by Buitink and Wouda (Citation2001) and latterly by Maandag et al. (Citation2007), models included, Model A: school as workplace (work placement model/host model); Model B: school with a central supervisor (co-ordinator model); Model C: trainer in the school as a trainer of professional teachers (partner model); Model D: trainer in the school as the leader of a training team in the school (network model) and Model E: training by the school (training school model). Maandag et al. (Citation2007) observed a significant difference between countries on matters of collaboration between universities and schools. In the Irish context, Conway, Murphy, and Rutherford (Citation2014) found that Model A: the workplace/host was the dominant practice of school-university co-operation whereby student teachers gain their practical experience in schools and the more theoretical aspects of the programme in the university. They argue for the need for a re-examination of this dominant model to allow for a more collaborative approach to ITE. Echoing the centrality of teacher collaboration to any effective model of school–university partnership, Smith (Citation2016) posits the notion of a continuum from total separation (practice schools) to some integration (partner schools) to deeper collaboration (university schools). This continuum serves as a useful conceptual model for this research as it provides the author with a tool to frame the discussion with participants of the study regarding their perception of the school–university nexus and degrees of partnership in the Irish context.

Unpacking the fundamental differences between the various school–university partnerships identified by Smith, as illustrated above (see ), Smith theorises that within ‘practice schools’ there is a segregation of duties whereby the university takes primary responsibility for the theoretical components of teacher education, with schools assuming responsibility for honing the practice skills of teaching. In ‘partner schools’ there is a formal agreement where schools must apply and make a case as to why they are suitable and if accepted the university offers continuing professional development for teachers and opportunities to be involved in research projects with the university. Further along the continuum is the ‘university school’ which is an emerging concept in Norway. The four core principles of this kind of partnership are improving the practicum, research and development initiatives, competence development of teachers and teacher educators, and creating networks to circulate the learning from the experiences of participants (University of Tromsø/The Arctic University of Norway Citation2013).

Figure 1. Continuum of school-university co-operation in Norway (Smith Citation2016, 28).

The partner and university school approache being pioneered in Norway resonate with key developments in teacher education nationally including the Teaching Council’s CROl´ Research Series (Collaboration and Research for Ongoing Innovation). This initiative draws together several strands of the Council’s work that encourage teachers’ engagement with research as well as providing support to teachers who undertake practitioner research including the John Coolahan Research Support Framework. In addition, Teachers’ Research Exchange (T-REX) is a Teaching Council supported an online community of practice for educational research in Ireland. It provides a platform for increasing research literacy and engagement through collaboration between student teachers, working teachers and professionals in higher education. In their new Céim: Standards for Initial Teacher Education (2020), the Teaching Council has clearly outlined the significance of research in the context of school placement and encourages greater partnership between schools and universities whereby:

The school placement shall provide opportunities for student teachers to: engage in research on their own practice that demonstrates the connection between the sites of practice (HEI and school). The student teacher shall discuss their research plans with the Treoraí [co-operating teacher], as they have overall responsibility for the class (13).

Jones et al. (Citation2016) build on the notion of a continuum of school–university co-operation with their typology of models and purposes of school–university partnerships. These partnerships are labelled connective, generative and transformative in a typology demonstrating levels of embeddedness rather than hierarchy. Connective partnerships represent a superficial level partnership in which there is a perceived ‘win–win’ outcome based on short-term mutual needs being met. Generative partnerships are those that lead to new or different practices arising in school praxis and/or university programmes due to a closer level of longer-term joint planning and reflection. Transformative partnerships represent practices at school and/or university level that is transformed as a result of a deeper level of joint professional learning and collaborative inquiry. This conceptual model was employed in this study to empower school leaders to explain their school’s perceived existing level of school-university co-operation and the level to which they aspire ().

Table 1. Representations of partnership practice (Adapted from Jones et al. Citation2016, 16).

Based on interviews with school leaders, co-operating teachers, student teachers and university tutors [n = 40], working on an initial ITE programme in a university in the Republic of Ireland, this article provides a synthesis of this range of stakeholders’ views on how school–university partnerships can be optimised in the Irish context.

Methodology

This qualitative study consisted of carrying out a series of semi-structured interviews with co-operating teachers [n = 10], student teachers [n = 10] university tutors [n = 10] and school leaders [n = 10] across a purposive sample of ten case study schools from the data base [n = 152] of placement schools involved with an ITE programme in a university in Dublin. A range of school types and post-primary curricular subjects were represented in the sample. This included the three main models of post-primary schools in Ireland: Voluntary Secondary Schools (fee paying and non-fee paying), Education and Training Board (ETB) Schools and Community and Comprehensive Schools. Schools in communities of disadvantage referred to as DEIS (Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools) schools and non- DEIS schools along with co-educational and single-gender schools are also represented in the case studies. Taking cognisance of Goodson and Sikes (Citation2010) observation that ‘adequacy is dependent not upon quantity but upon the richness of the data … ’ (23) the number of participants in this study was small and there is no intent to generalise from the study to all school leaders, co-operating teachers, student teachers and university tutors. Rather the study sought insights to produce tentative generalisations which may influence future deliberations on policy and practice in an open-ended rather than a prescriptive manner thus leaving room for multiple voices as to how such policy items may be adapted to particular contexts.

A semi-structured interview schedule, informed by national and international literature, was devised which questioned interviewees on their experiences of the recent reform agenda and their views on the nature of school–university partnerships. The merit of a semi-structured interview format was that it does not seek to test a specific hypothesis (David and Sutton Citation2004), rather it is a flexible, open-ended, non-standardised instrument (Corbetta Citation2003). The study was guided by the following research questions that were adapted to the sub-groups as appropriate:

♣ Using the Jones et al. (Citation2016) and Smith’s (Citation2016) conceptual models, describe your organisation’s level of co-operation in ITE.

♣ Do you understand your role in ITE? Do you believe your role is recognised/valued?

♣ Do you think there are good links between the school and university?

♣ What are the barriers to effective school–university partnerships?

♣ Do you believe that school–university partnerships can be improved, and if so how?

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim prior to analysis. Participants were allocated pseudonyms to ensure confidentiality and the dialectical features of the interview data were preserved in line with best practice in reporting qualitative data research (Macnaghten and Myers Citation2004; Rapley Citation2004). Interview data was initially coded according to participant and school type (see and ). For example, when referring to the code CTS1, the first two letters identify the participant as a co-operating teacher [CT] and the subsequent letter and number identifies the school type [S1]. Note University Tutors are labelled according to letters as they work across more than one school, for example, UTA, UTB, etc.

Table 2. Summary of school types included in the study and related codes.

Table 3. Participant type and codes.

Findings

The findings offer a range of stakeholders’ (school leaders [n = 10], university tutors [n = 10], co-operating teachers [n = 10] and student teachers [n = 10]) perspectives on how school–university partnerships can be optimised in the Irish context. Using inductive analysis, the themes that emerged from the research data included:

Misconceptions about degrees of partnership in ITE and of roles therein.

The key role of the co-operating teacher and ‘close-to-practice’ research in fostering a ‘third space’ in ITE.

A sense of malaise in relation to levels of pressure, change over-load and lack of adequate resources.

Misconceptions about degrees of partnership in ITE and of roles therein

The spotlighting of the school–university nexus and the pervasive use of the term partnership in teacher education has led to confusion as to who teacher educators are and an ambiguous understanding of the meaning of partnership in ITE (Harford and O’Doherty Citation2016; O’Doherty and Harford Citation2017). In the main, such partnerships are led and constructed by HEIs in conjunction with state agencies, however, the democratic involvement of schools in framing such agreements and thus shaping practices is often notably absent. Furthermore, cultural and historical norms accompanying roles in teacher education can inhibit meaningful collaboration especially between university tutors and co-operating teachers (Reynolds, Ferguson-Patrick, and McCormack Citation2013). The range of responses from the four sub-groups represented in this study reflected the ongoing tension that persists in relation to the school–university nexus, degrees of partnership and roles therein. Participants of the study were asked to use Smith’s (Citation2016) continuum of school–university co-operation to describe their perception of the level of school–university co-operation in their context. There was a general agreement amongst participants that despite the ubiquitous use of the term ‘partner school’ in ITE most of the participants described the co-operation between the school and the university as being at the level of ‘practice school’ whereby the university teaches the theory and the school deals with the practical skills of teaching. Furthermore, school leaders were unanimous in their view that while they aspired towards being a ‘university school’ (Smith Citation2016) enabled by a ‘transformative’ model of school–university partnership, they believed that the most common model in Ireland at present reflects the ‘connective’ model described by Jones et al. (Citation2016) as evidenced by the comments of school leaders:

I would be very interested in being more involved in projects and school based research if there was a proper structure with resources and support provided. (SL, S6)

The only time we have any interaction with the college is if the placement tutors look to see us when they are in the school and maybe an odd email here and there, but apart from that there is not much collaboration. (SLS4)

Recognition of the schism across both key spaces was palpable:

I would like to see my role as a conduit between schools and universities, but to be honest schools tend to act pretty much as independent spaces. It’s rare that any professional dialogue occurs across both of those spaces although I always advise school personnel that I have visited the school and that I would welcome their input. (UTB)

Such a disconnect was even apparent among student teachers, who very early into their ITE programme, were already being socialised into the norms and practices of each entity:

To be honest, I don’t see too much cross-over or collaboration between my university tutor and my co-operating teacher. (STS4)

When questioned on the issue of collaboration, co-operating teachers recognised this was important but argued the existing nature of their working lives precluded the possibility of greater collaboration.

I do engage with the university around professional development opportunities when I can, but my capacity to do this is limited. I would like to have a deeper engagement with the work of the university and building stronger links with our school, but in the current climate, there is very little time for this. (CTS9)

However, in cases where co-operating teachers also worked with universities as tutors, there was a greater alignment of goals and a deeper understanding of the need for a shared professional language and approach. There was also evidence that this engagement with ITE had a ripple effect across the school community:

I work both as a co-operating teacher and as a university tutor so I bring both lenses to the work that I do with student teachers. I think my dual role means that my school is very open to engaging with the university and I think this also impacts on my colleagues who are more open to discussions around university-school relationships, around building professional dialogue. I also think this is really important for the student teachers who are placed with us to see as they see their professional formation as a joint enterprise, a collaborative one. This is important modelling in my opinion. (CTS5)

In situations where links between partner schools and the university were strong, there was evidence of organic fostering of democratic partnerships in ITE enabling the ‘seed that enables ‘partnership’ in school placement to be experienced, understood, and grown’ (Hall et al. Citation2018, 179). This was made possible through a shared understanding of the nature of roles and responsibilities and a common professional language.

The key role of the co-operating teacher and ‘close-to-practice’ research in fostering a ‘third space’ in ITE.

In keeping with the international body of research on what contributes to an effective school–university partnership, participants in this study were aligned in their articulation of the importance of building professional learning communities across the various actors which feed into school–university partnerships (Bernay et al. Citation2020). Central to the effective and sustainable operationalisation of this professional learning community was planning, dialogue on the application of theory to practice, the use of a shared language underpinned by a shared understanding and deep knowledge base and a sustained focus on practitioner inquiry (Darling-Hammond Citation2006; Dimmock Citation2016; Gutierez Citation2019). While none of the participants in the study explicitly used the term ‘third space’ (Zeichner Citation2010) it was clear from their responses that each of the categories of respondent was aware of both the tensions and benefits in accessing a third space. This was particularly well conceptualised by school leaders and co-operating teachers:

Finding a common space to really engage in joint dialogue and a shared agenda is central to any meaningful partnership between the school and the university. (SLS2)

Working to find common ground, shared goals and a democratic partnership is vital if universities are really to work with schools in an equal way in support of the formation of student teachers, however as a co-operating teacher I have no links at all with the university and the supervisors and tutors rarely ask to see me, but they look for senior management instead. (CTS8)

While there was consensus amongst school-based educators that school–university links could be stronger, time for meetings was cited as a major challenge. However, a willingness to be creative to find ways of working together meaningfully was evident.

I think the university itself is very removed from the school, but opportunities for dialogue do arise when the supervisor and tutor visit the school. This can be ad hoc at times and it would be great if we had more warning so we could formalise this more, but we do understand that school visits are unannounced, so we always try and make ourselves available. (SLS10)

We include our PMEs with our NQTs when we are having some of our Droichead meetings. It is a shared space where they can learn together. I think that even though being a PME requires a slightly different support to being an NQT, they can certainly be married together. (SLS3)

This echoes the sentiments of Ó Gallchóir, O’Flaherty, and Hinchion (Citation2019) who recommend that the Teaching Council, the National Induction Programme for Teachers (NIPT) and the Department of Education and Skills (DES) broaden the scope of the Droichead [Irish for bridge] programme for newly qualified teachers (NQTs) to cater for student teachers and that ‘policy should reflect a clearer understanding of the interwoven nature of the continuum of teacher preparation, instead of naïvely viewing each step in the continuum as a distinct and separate entity as this only serves to undermine the value of such initiatives’ (Ó Gallchóir, O’Flaherty, and Hinchion, Citation2019, 385). There is evidence from this study that the participants recognise the key role of the co-operating teacher (Farrell Citation2021) in supporting student teachers and the importance of providing them with a space to link with both the student teacher and the university.

I think probably where the most collaboration takes place is between the student teacher and their co-operating teacher who has the biggest influence on the student. We try to provide space for them to meet in a structured way and we also encourage our co-operating teachers to support students with their dissertations or any action research that is required as part of their course. (SLS9)

I think it has been proven by the response to COVID-19 that technology can be used more effectively to create shared learning spaces where the university can provide information sessions to all involved in school placement and free online CPD and the teachers can provide some feedback on how new ideas being proposed by the college work out on the site of practice. (SLS5)

Increased use of technology during COVID-19 also demonstrated how some student teachers acted as technology mentors to their co-operating teachers (Farrell and Marshall Citation2020). Furthermore, student teachers evidenced a strong recognition of the learning across the school-university nexus during the completion of their school-based research projects:

It was only when I started my dissertation in year two that I began to fully appreciate the links between what I learned in college and what I actually did in practice. Taking part in action research on my practice with the support of my co-operating teacher really made everything so much clearer to me. (STS6)

University tutors also noted the significance of the support of school leaders in providing a time and space and a structure for constructive dialogue and support between student teachers and their co-operating teacher.

I notice in schools where school leaders organise and facilitate structured times for student teachers to meet with their co-operating teacher for the purpose of professional dialogue that there is a higher chance of co-operating teachers also helping student with action research on practice. (UTJ)

This study highlighted that despite the absence of a systemic and coherent approach to enabling alliances between schools and universities involved in initial teacher education, there is a willingness by schools to participate in a ‘third space’ for mutual learning. This is especially notable in schools where professional development opportunities provided by universities are availed of and in schools that engage in joint the research aimed at improving practice. While teacher agency is instrumental in fostering a ‘third space’ for collaboration, time, initiative overload and lack of resources are common barriers that are difficult to overcome.

A sense of malaise in relation to levels of pressure, change over-load and lack of adequate resources

A plethora of national educational policies that are part of a wider international framework which requires states to respond to the challenges of the twenty-first century (Farrell and Sugrue Citation2021) have changed the role of the teaching profession. Furthermore, recent reforms and restructuring of ITE programmes have added significantly to teachers’ and school leaders’ workload without any corresponding increase in resources or additional recognition (Harford and O’Doherty Citation2016). In line with international trends regarding teacher anxiety, stress and burnout (Livingston and Flores Citation2017), all participants in this study referred to a sense of malaise in relation to levels of pressure, change over-load and lack of adequate resources. This was particularly evident among the responses from student teachers and co-operating teachers:

I am exhausted and constantly feel under so much pressure. Planning, preparing resources, and then trying to deal with all of the new things being thrown at me from a school perspective, I literally feel like I am about to collapse. (STS9)

School leaders, also, however, registered disquiet about stress levels and anxiety, particularly among student teachers and newly qualified teachers, concerned about the implications of this for teacher recruitment and retention:

Each year, I see the stress levels of these student teachers increase. They seem to be very stretched in terms of workload and I know some of my own have to hold down part-time jobs at the weekends in shops and petrol stations just to make ends meet. (SLS5)

It was clear that most of the critical professional dialogue between co-operating teachers and student teachers was occurring in an ad hoc manner, without adequate time release and structured support.

I am working with three student teachers this year, all from different universities. All three are constantly at breaking point and to be honest, I feel like that a lot too. I am trying my best to support them, but most of this is done during my break or over the phone in the evening, when I am conscious of my own workload. It’s really not sustainable, if we are expected to really devote time to their professional development the whole thing needs to be better resourced. I wasn’t even trained for this. (CTS8)

The issue of a lack of professional development for co-operating teachers, raised by CTS8, was echoed by several participants:

All this reform is being superimposed upon us and being justified in terms of international best practice and 21st-Century skills, but the system is over-heating, and the lack of resources, including appropriate CPD for teachers rolling out this reform, is quite simply astounding. (CTS4)

Several participants referred to the impact of an education system undergoing significant reform at multiple levels and the resultant cacophony of multiple actors negotiating new challenges.

While I understand the value of an education system which is responding to the changing needs of a pupil population and a wider society, I think the brakes need to be put on in terms of the scale of the reform. I see more experienced teachers, as well as student teachers, exhausted by the scale of reform and the pressure it places on them to be on top of their work as they enter classrooms. (UTF)

These included concerns in relation to industrial relations issues:

I’ve always wanted to be a teacher, but it’s really disappointing to see how hard it can be to make it as a teacher. Schools are becoming more and more challenging, the workload is massive, and then there are major issues around pay and conditions and casualisation. I think the government needs a wake-up call. It’s not surprising there is a drop in numbers to programmes or a teacher supply crisis. (STS7)

Similarly, participants were vocal in relation to the resource implications and the centrality of school leadership:

I think the school placement part of ITE is crucial and can really colour a teacher’s experience of their whole career. However, if we as experienced teachers are supposed to be leading learning and be leaders of student teachers, then I think the system needs to recognise this more fairly. This is a question of resources and leadership. (CTS10)

It is clear from the participants’ comments that the key actors in ITE have been burdened with initiative overload and curriculum reform at a rapid pace and without adequate resourcing. The anxiety resulting from negotiating the myriad of new challenges faced by the teacher education community has been exacerbated by uncertainty and industrial relations issues and is leading to burnout and fatigue. However, despite these complications, teachers and school leaders continue to support student teachers on school placement out of a sense of professional responsibility and goodwill.

Concluding thoughts

Teacher education programmes in the Irish context have historically worked hard to bridge the theory/practice divide (Harford and MacRuairc Citation2008; Heinz and Fleming Citation2019; la Velle Citation2019; McGarr, O’Grady, and Guilfoyle Citation2017) and promote ‘inquiry as a stance’ (Cochran-Smith and Lytle Citation2009), yet their efforts will only succeed if this is a joint endeavour through ‘democratic pedagogical partnership’ (Farrell Citation2021) with schools. However, in the Irish context, these agreements are dominated by HEIs and state agencies and the democratic involvement of the practice field in framing such agreements is often conspicuously absent. This study has demonstrated that recognition of the complex and critical role which schools play in teacher education programmes and the need to properly resource and develop sustainable school-university partnerships is central the ongoing development of ITE programmes. This is also essential for the development of a school-university nexus that goes beyond bridging the theory/practice divide to providing a ‘third space’ that enables universities and schools to optimise synergies that foster innovative practice and experimentation and engender the role transformation required to meet the diverse needs of all learners in all school contexts in the twenty-first century.

Halvorsen (Citation2014) notes that the ingredients of effective partnership in ITE involve protecting each partner’s identity while at the same time having shared goals, a democratic approach, mutual trust, innovation and flexibility. If this is to be achieved, ‘boundary crossings’ (Akkerman and Bakker Citation2011; Bullough and Draper Citation2004; Zeichner Citation2010) which exist and co-exist between and across the various actors which contribute to school–university partnerships, must be encouraged. Furthermore, there needs to be a systemic recognition by policy makers that we do not have to invent the future out of nothing (Farrell and Sugrue Citation2021). There is potential to accomplish the establishment of ‘third spaces’ in ITE through broadening existing initiatives such as the Droichead mentoring programme for newly qualified teachers to the ITE context along with harnessing the potential of joint research via the Teaching Council’s CROÍ research initiative. Moreover, the introduction of the new Céim: Standards for Initial Teacher Education (Teaching Council Citation2020) will provide opportunities for further innovation and collaboration that should be enhanced by the increasing acceptance and use of online communication that is effective, convenient and time saving.

However, the common agreement regarding understanding ‘partnership’ required for these policies and initiatives to flourish needs to be complemented by acknowledgement that even shared understandings often create a range of practices due to contextual differences. Hence there is an ongoing necessity for re-interpretation of ideas that practice always needs to be ‘on the rough ground’ (Dunne Citation1993). It is for this reason that professional judgement is critical, necessitating a degree of ‘relative autonomy’ especially if teachers’ capacities are to be continuously renewed and extended; otherwise, they are reduced to being technicians, governed by an instrumentalist understanding of practice, to the exclusion of the possibility of praxis. Therefore, nurturing professional agency and responsibility in the teaching profession is fundamental to enabling school–university partnerships. Agency and professional responsibility are not fixed capacities but develop from the interplay of individual capabilities and efforts within contextual and organisational factors in concrete situations (Biesta Citation2015), while responsibility implicitly encompasses moral and ethical dimensions.

While teacher agency and professional responsibility may be important, the days of ‘heroic’ performance (Kruger et al. Citation2009; Sugrue Citation2009) needs to be replaced by a considerably stronger sense of collective agency and collaborative professionalism (Hargreaves and O'Connor Citation2018) that takes professional responsibility seriously. This will require calling out systemic shortfalls in terms of necessary and sustained support for teacher educators’ learning in the context of ITE. The existing ITE framework in Ireland is not fit for purpose, particularly as it continues to rely on the informal, often ad hoc role of the practice field (Farrell Citation2021). However, school leaders, co-operating teachers, student teachers and university tutors all have an important role to play in optimising an effective partnership approach to ITE and in order to do this well, they need to be resourced and supported and their insights and contributions need to be valued, respected and recognised at the system level.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rachel Farrell

Rachel Farrell is the Director of the Professional Master of Education (PME) programme and a research fellow in the area of school-university partnerships in Initial Teacher Education (ITE) in the School of Education in University College Dublin. With a keen interest in partnerships in education, Rachel has led many collaborative initiatives involving a range of education and industry stakeholders including: An Evaluation of digital portfolios in ITE with MS Education Ireland and Girls in DEIS Schools: Changing Attitudes /Impacting Futures in STEM funded by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) and supported by the Professional Development Service (PDST) for Teachers. Research interests also include global citizenship education and sustainable pedagogy.

References

- Akkerman, S. F., and A. Bakker. 2011. “Boundary Crossing and Boundary Objects.” Review of Educational Research 81 (2): 132–169. doi:10.3102/0034654311404435.

- Arhar, J., T. Niesz, J. Brossman, S. Koebly, K. O’Brien, D. Loe, and F. Black. 2013. “Creating a ‘Third Space’ in the Context of a University–School Partnership: Supporting Teacher Action Research and the Research Preparation of Doctoral Students.” Educational Action Research 21 (2): 218–236.

- Beach, D., and C. Bagley. 2013. “Changing Professional Discourses in Teacher Education Policy Back Towards a Training Paradigm: A Comparative Study.” European Journal of Teacher Education 36 (4): 379–392. doi:10.1080/02619768.2013.815162.

- BERA. 2018. Statement on Close-to-Practice Research. Accessed January 25, 2020. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/bera-statement-on-close-to-practice-research [Google Scholar].

- BERA-RSA. 2014. Research and the Teaching Profession: Building the Capacity for a Self-improving Education System. Final Report of the BERA-RSA Inquiry Into the Role of Research in Teacher Education. London: BERA and RSA.

- Berger, J. G., and K. Johnston. 2015. Simple Habits for Complex Times: Powerful Practices for Leaders. . Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books.

- Bernay, R., P. Stringer, J. Milne, and J. Jhagroo. 2020. “Three Models of Effective School–University Partnerships.” New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 55 (1): 133–148. doi:10.1007/s40841-020-00171-3.

- Biesta, G. 2015. “What is Education For? On Good Education, Teacher Judgement, and Educational Professionalism.” European Journal of Education 50 (1): 75–87.

- Boland, T. 2015. “A Dialogue on the Future Funding of Higher Education in Ireland. Accessed August 16 2020.” http://www.hea.ie/sites/default/files/ria_tb_funding_speech_v2_002.pdf.

- Buitink, J., and S. Wouda. 2001. “Samen-scholing, scholen en opleidingen, elkaars natuurlijke partners [Cooperative Teaching Education, Schools and Training Institutions as Partners].” VELON Magazine 22 (1): 17–21.

- Bullough, R. V., and R. J. Draper. 2004. “Making Sense of a Failed Triad: Mentors, University Supervisors, and Positioning Theory.” Journal of Teacher Education 55 (5): 407–420. doi:10.1177/0022487104269804.

- Cochran-Smith, M., and S. L. Lytle. 1999. “Relationships of Knowledge and Practice: Teacher Learning in Communities Review of Research in Education.” American Educational Research Association 24: 249–305.

- Cochran-Smith, M., and S. Lytle. 2009. Inquiry as a Stance: Practitioner Research in the Next Generation. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Conway, P. F., R. Murphy, and V. Rutherford. 2014. “Learningplace’ Practices and Pre-service Teacher Education in Ireland: Knowledge Generation, Partnerships and Pedagogy, vol 10.” In Workplace Learning in Teacher Education. Professional Learning and Development in Schools and Higher Education, edited by O. McNamara, J. Murray, and M. Jones, 221–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7826-9

- Corbetta, P. 2003. Social Research: Theory, Methods and Techniques. London: Sage Publications.

- Council of the European Union. 2014. Efficient and innovative education and training to invest in skills. Official Journal of the Council of the European Union. Accessed August 16, 2020. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.C_.2014.062.01.0004.01.ENGandtoc=OJ:C:2014:062:TOC#ntr1-C_2014062EN.01000401-E0001.

- Czerniawski, G., A. Guberman, and A. MacPhail. 2017. “The Professional Developmental Needs of Higher Education-based Teacher Educators: An International Comparative Needs Analysis.” European Journal of Teacher Education 40 (1): 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2016.1246528.

- Darling-Hammond, L. 2006. “Constructing 21st-century Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 57: 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487105285962.

- David, M., and C. Sutton. 2004. Social Research: The Basics. London: SAGE.

- Dimmock, C. 2016. “Conceptualising the Research–Practice–Professional Development Nexus: Mobilising Schools as ‘Research-engaged’ Professional Learning Communities.” Professional Development in Education 42 (1): 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.963884.

- Dunne, J. 1993. Back to the Rough Ground ‘Phronesis’ and ‘Techne’ in Modern Philosophy and in Aristotle. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Engeström, Y. 2008. From Teams to Knots: Activity-theoretical Studies of Collaboration and Learning at Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511619847.

- European Commission. 2005. Common European principles for teacher competences and qualifications. Accessed June 20, 2020. http://www.pef.uni-lj.si/bologna/dokumenti/eu-common-principles.pdf.

- Farrell, R. 2021. Co-Operating Teachers: The Untapped Nucleus of Democratic Pedagogical Partnerships in Initial Teacher Education in Ireland. Educational Research and Perspectives. December 2020 Special Issue to Mark 70 Years in Existence. New Education Horizons.

- Farrell R., and K. Marshall. (2020). The Interplay Between Technology and Teaching and Learning: Meeting Local Needs and Global Challenges. In: Fox J., Alexander C., Aspland T. (Eds.) Teacher Education in Globalised Times. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4124-7_3

- Farrell, R. and C. Sugrue. 2021. Sustainable Teaching in an Uncertain World: Pedagogical Continuities, Un-Precedented Challenges. London: IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.96078

- Flores, M. A. 2016. Teacher Education Curriculum. In J. Loughran and M. Hamilton (Eds.). International Handbook of Teacher Education (pp. 187–230). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0366-0_5

- Flores, M. A. 2018. “Tensions and Possibilities in Teacher Educators’ Roles and Professional Development.” European Journal of Teacher Education 41 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1080/02619768.2018.1402984.

- Goodson, I., and P. Sikes. 2010. Life History Research in Educational Settings. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Gutierez, S. B. 2019. “Teacher-practitioner Research Inquiry and Sense Making of Their Reflections on Scaffolded Collaborative Lesson Planning Experience.” Asia-Pacific Science Education 5: 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41029-019-0043-x

- Hall, K., R. Murphy, V. Rutherford, and B. Ní Áingléis. 2018. School Placement in Initial Teacher Education. Maynooth: The Teaching Council.

- Halvorsen, K. 2014. “Partnerships in Teacher Education.” Ph.D. diss. University of Bergen, Norway.

- Harford, J. 2010. “Teacher Education Policy in Ireland and the Challenges of the Twenty-first Century.” European Journal of Teacher Education 33 (4): 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2010.509425.

- Harford, J., and G. MacRuairc. 2008. “Engaging Student Teachers in Meaningful Reflective Practice.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (7): 1884–1892.

- Harford, J., and T. O’Doherty. 2016. “The Discourse of Partnership and the Reality of Reform: Interrogating the Recent Reform Agenda at Initial Teacher Education and Induction Levels in Ireland.” Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal 6 (3): 37–58.

- Hargreaves, A., and M. T. O'Connor. 2018. Collaborative Professionalism: When Teaching Together Means Learning for all. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Hartley, D. 2007. “Education Policy and the ‘Inter-Regnum’.” Journal of Education Policy 22 (6): 695–708.

- Heinz, M., and M. Fleming. 2019. “Leading Change in Teacher Education: Balancing on the Wobbly Bridge of School University Partnership.” European Journal of Educational Research 8 (4): 1295–1306. doi:10.12973/eu-jer.8.4.1295.

- Ievers, M., K. Wylie, C. Gray, B. Ní Áingléis, and B. Cummins. 2013. “The Role of the University Tutor in School-based Work in Primary Schools in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.” European Journal of Teacher Education 36 (2): 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2012.687718.

- Izadinia, M. 2014. “Teacher Educators’ Identity: A Review of Literature.” European Journal of Teacher Education 37 (4): 426–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2014.947025.

- Jones, M., L. Hobbs, J. Kenny, C. Campbell, G. Chittleborough, and A. Gilbert. 2016. “Successful University-school Partnerships: An Interpretive Framework to Inform Partnership Practice.” Teacer Education 60: 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.006.

- Kruger, T., A. Davies, B. Eckersley, F. Newell, and B. Cherednichenko. 2009. Effective and Sustainable University-School Partnerships: Beyond Determined Efforts by Inspired Individuals. Canberra: Victoria University.

- la Velle, L. 2019. “The Theory–Practice Nexus in Teacher Education: new Evidence for Effective Approaches.” Journal of Education for Teaching 45 (4): 369–372. doi:10.1080/02607476.2019.1639267.

- Livingston, K., and M. A. Flores. 2017. “Trends in Teacher Education: A Review of Papers Published in the European Journal of Teacher Education Over 40 Years.” European Journal of Teacher Education 40 (5): 551–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1387970.

- Maandag, D. W., J. F. Deinum, A. Hofman, and J. Buitink. 2007. “Teacher Education in Schools: An International Comparison.” European Journal of Teacher Education 30 (2): 151–173.

- Macnaghten, P., and G. Myers. 2004. “Focus Group in Qualitative Research Practice.” In Qualitative Research Practice, edited by C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. F. Gubrium, and D. Silverman, 65–79. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Max, C. 2010. “Learning-for-teaching Across Educational Boundaries. An Activity-theoretical Analysis of Collaborative Internship Projects in Initial Teacher Education.” In Cultural-historical Perspectives on Teacher Education and Development, edited by V. Ellis, A. Edwards and P. Smagorinsky, 212–240. London: Routledge.

- März, V., and G. Kelchtermans. 2013. “Sense-making and Structure in Teachers’ Reception of Educational Reform. A Case Study on Statistics in the Mathematics Curriculum." Teaching and Teacher Education 29: 13–24.

- McGarr, O., E. O’Grady, and L. Guilfoyle. 2017. “Exploring the Theory-Practice Gap in Initial Teacher Education: Moving Beyond Questions of Relevance to Issues of Power and Authority.” Journal of Education for Teaching 43 (1): 48–60. doi:10.1080/02607476.2017.1256040.

- O’Doherty, T., and J. Harford. 2017. “‘Building Partnerships in Irish Teacher Education – A Case Study’.” In A Companion to Research in Teacher Education, edited by M. Peters, B. Cowie, and I. Menter, 167–178. Netherlands: Springer.

- OECD. 2015. Education Policy Outlook 2015: Making Reforms Happen. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://doi.org/10.1787/9789264225442-en.OECD.

- Ó Gallchóir, C., J. O’Flaherty, and C. Hinchion. 2019. “My Cooperating Teacher and I: How pre-Service Teachers Story Mentorship During School Placement.” Journal of Education for Teaching 45 (4): 373–388. doi:10.1080/02607476.2019.1639258.

- Rapley, T. 2004. Interviews. In Qualitative Research Practice, edited by C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. F. Gubrium, and D. Silverman, 15–33. London: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848608191

- Reynolds, R., K. Ferguson-Patrick, and A. McCormack. 2013. “Dancing in the Ditches: Reflecting on the Capacity of a University/School Partnership to Clarify the Role of a Teacher Educator.” European Journal of Teacher Education 36 (3): 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2012.755514.

- Smith, K. 2016. “Partnerships in Teacher Education-Going Beyond the Rhetoric, with Reference to the Norwegian Context.” CEPS Journal: Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal 6 (3): 17–36.

- Sugrue, C. 2009. “From Heroes and Heroines to Hermaphrodites: Emasculation or Emancipation of School Leaders and Leadership?” School Leadership & Managemen 29 (4): 353–371. doi:10.1080/13632430903152039.

- Sugrue, C., and T. D. Solbrekke. 2017. “2017. Policy Rhetorics and Resource Neutral Reforms in Higher Education: Their Impact and Implications?” Studies in Higher Education 42 (1): 130–148. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1036848.

- Teaching Council. 2020. Céim: Standards for Initial Teacher Education. Maynooth: Teaching Council.

- University of Tromsø/ The Arctic University of Norway. 2013. "Report on the University School Project in Tromsø (USPiT)." Accessed January 22, 2020. https://uit.no/Content/359522/cache=20182308094145/Rapport%202013.pdf.

- Zeichner, K. 2010. “Rethinking the Connections Between Campus Courses and Field Experiences in College- and University-based Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 61 (1–2): 89–99.

- Zeichner, K., K. A. Payne, and K. Brayko. 2015. “Democratizing Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 66 (2): 122–135. doi:10.1177/0022487114560908.